EDITORIAL

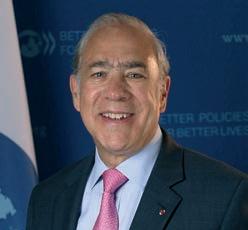

Setting course for a human-centred AI We must seize the potential of AI and prepare and protect future generations Angel Gurría Secretary-General of the OECD

Fifty years ago, the world watched in awe as the first humans landed on the moon. Today, artificial intelligence (AI) is helping us to build on this achievement, by giving us the power to map the moon, to locate and count craters, and even (virtually) to moonwalk! Here on earth, AI has the potential to catalyse remarkable progress in our education, health, transport, social protection, communication and energy systems. It can also help us meet our global ambitions, including the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and the Paris Climate Agreement. But AI is also fuelling anxieties and ethical concerns. Many fear that it will facilitate automated discrimination, by codifying existing biases from the analogue world into the digital world, including those related to gender, race or the justice system. To realise the full potential of this promising technology, we need one critical ingredient: trust. We need human-centred AI that fosters sustainable development and inclusive human progress. A few priorities should be highlighted. First, we must seize AI’s potential for productivity and scientific advances. AI holds significant potential to drive productivity gains. It is helping people make better predictions and decisions, be they a doctor, a shop-floor manager or a farmer in the field. AI start-ups attracted over 12% of all worldwide private equity investments in the first half of 2018, reflecting this economic potential. AI can also increase the productivity of science. More than a decade ago at a laboratory in Wales, a robot named Adam became the first machine to discover new scientific knowledge independently–a compound that works against a drug-resistant parasite that causes malaria. But such advances are not automatic; significant complementary investments are needed to support them. Many firms do not even use relatively basic digital technologies, let alone AI. In fact, OECD analysis shows that only 11% of small firms perform big data analysis. Meanwhile, the growing prominence of AI in science is raising important policy questions around access to data and high-performance computing, intellectual property, and education. Second, we must prepare for the transformation of the labour market and build skills. For workers, technological change presents great opportunities. It can improve flexibility, productivity and earnings; and it can also reduce exposure to dangerous, unhealthy and tedious tasks. But there are risks. Across OECD countries, on average, around 14% of jobs are at a high risk of automation in the next 10-15 years, and

a further 32% are at risk of disruption. AI will change, and perhaps accelerate, the profile of tasks that may be automated. There are also risks of increasing inequalities. In a rapidly changing world, lifelong learning is an imperative for everyone, particularly low-skilled workers. We must prepare and protect future generations. The OECD’s Learning Compass for 2030 outlines the need to adapt education so that our children become digitally aware citizens. This means going beyond literacy and numeracy, and fostering data and digital literacy. But having technical expertise and training a new generation of data scientists and digital experts are not enough. It will also be crucial to teach them social and emotional skills, as well as a sense of responsibility and ethics. The third priority is to put AI at the service of the environment. AI can accelerate the transition to a circular economy, for instance, reducing environmental pressures and the risks of raw material supply shocks. In fact, AI can help improve industrial production by making physical assets more intelligent and boosting data driven decision-making. This will help firms to extend product life, minimise waste, and optimise the performance of their systems and processes. AI is also spurring innovative environmental policy approaches, for example, by working with industry to develop electronic waste tracking systems. The OECD is setting a course for human-centred AI. The OECD recognises that actions at the margin will not be enough to harness AI for sustainable development. We need a comprehensive approach. In May, we launched the OECD Recommendation on Artificial Intelligence to promote the responsible stewardship of trustworthy AI. The Recommendation advances the first-ever set of intergovernmental principles on AI, includes technical definitions, principles for responsible stewardship of trustworthy AI (including human-centred values and fairness, transparency and explainability, robustness and accountability), recommendations for national policies and advice for international co-operation. In July, G20 Leaders endorsed the G20 AI Principles, which are largely drawn from the OECD Recommendation on AI. We will continue to advance multi-stakeholder collaboration on AI, with the launch of the OECD AI Policy Observatory, to facilitate the development of evidence and practical guidance for policymakers and act as a hub for OECD work on AI. Masayoshi Son, the founder of Soft Bank, said of AI, “If we misuse it, it’s a risk. If we use it in good spirits, it will be our partner for a better life”. We must harness the efficiency and intelligence of AI to build a better world where growth is inherently sustainable, inclusive and beneficial to all. oe.cd/obs/2R6

@A_Gurria

www.oecd.org/about/secretary-general/

www.oecdobserver.org/angelgurria

Adapted from keynote address on “AI for Sustainable Development”, delivered at the London Business School, 9 September 2019. For the full version, see https://oe.cd/2OV For more on the OECD AI Principles and AI Policy Observatory, visit our Going Digital platform at www.oecd.org/going-digital/ai/

OECD Observer No 319-320 Q3-Q4 2019

3