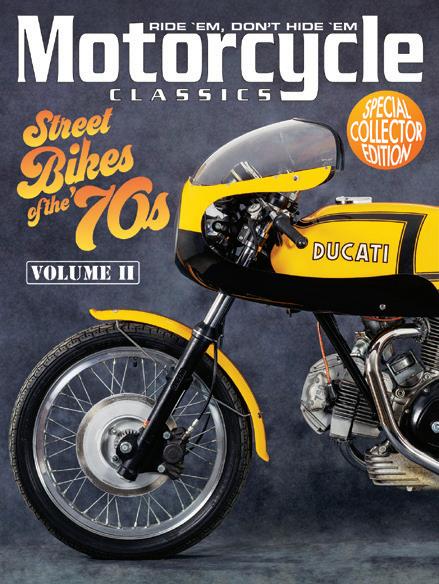

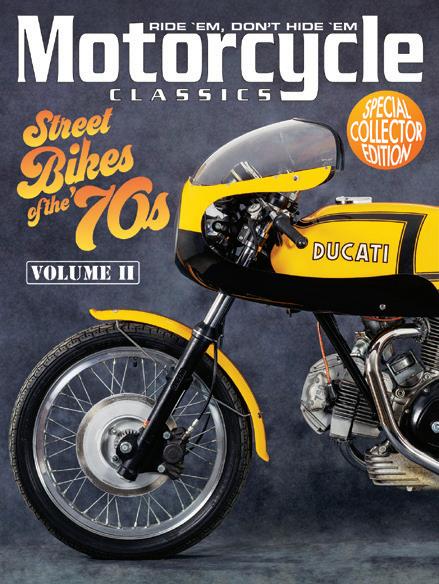

TRIUMPH TR6R

A LUCKY FIND OF AN AMAZINGLY ORIGINAL SINGLE-CARB TWIN

PLUS:

• RIDING THE 2023 MOTO GIRO D'ITALIA

• KANEMOTO DRAGON: 1974 KAWASAKI

H2R FLAT TRACKER

• CLASSIC SCENE: 2023 QUAIL

MOTORCYCLE GATHERING

RIDE `EM, DON’T HIDE `EM

$6.99 • Vol. 19 No. 1 • Display Until Oct. 2

September/October 2023

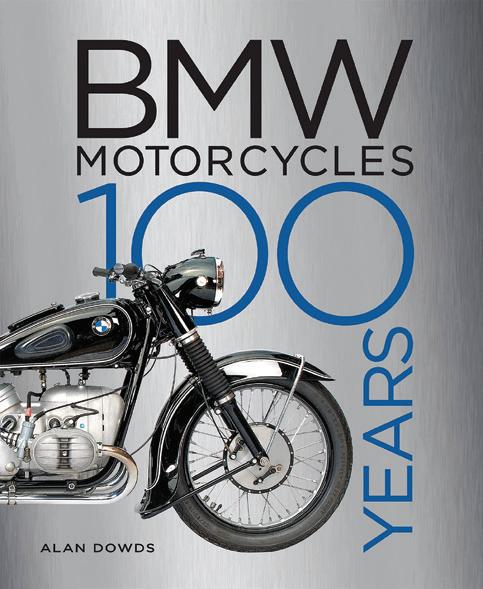

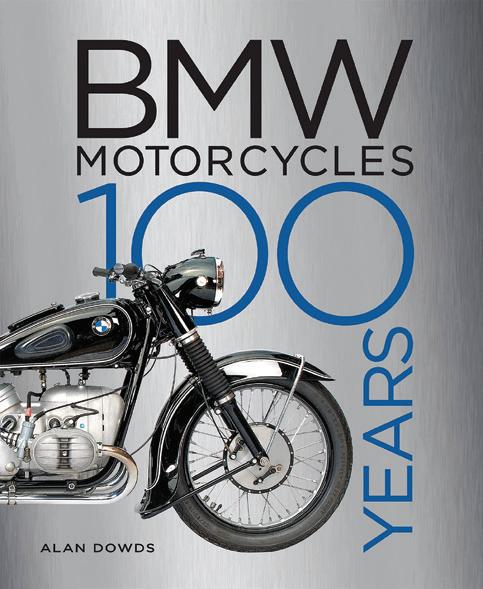

THE EVENT 100 YEARS IN THE MAKING

BMW MOTORRAD DAYS AMERICAS. OCT. 6–8

The first ever Motorrad Days Americas is here. Join us October 6-8 in Birmingham, Alabama at the Barber Vintage Festival. Celebrate 100 years of motorcycle excellence and test ride the latest innovations in BMW Motorrad technology. Don’t miss the three full days of pure #SoulFuel. Visit www.BMWMotorradDaysAmericas2023.com to learn more. #100YearsBMWMotorrad

©2023 BMW of North America LLC. The BMW trademarks are registered trademarks.

©2023 BMW of North America LLC. The BMW trademarks are registered trademarks.

DEPARTMENTS

4 SHINY SIDE UP

Attend the John Parham Estate Collection auction at the National Motorcycle Museum in Anamosa, Iowa.

6 READERS AND RIDERS

Readers chime in with feedback on police Indians, the Mystery Ships from the July/August issue of MC, and more.

ROAD MAP

38 NOT STOCK: THE MEDAZA WASP

Hand-crafted in Ireland, Don Cronin’s latest creation looks like the sort of bike that Captain America would ride, not a Royal Danish postman.

44 KANEMOTO DRAGON

Dain Gingerelli looks back at the 1974 Kawasaki H2R Flat Track racer.

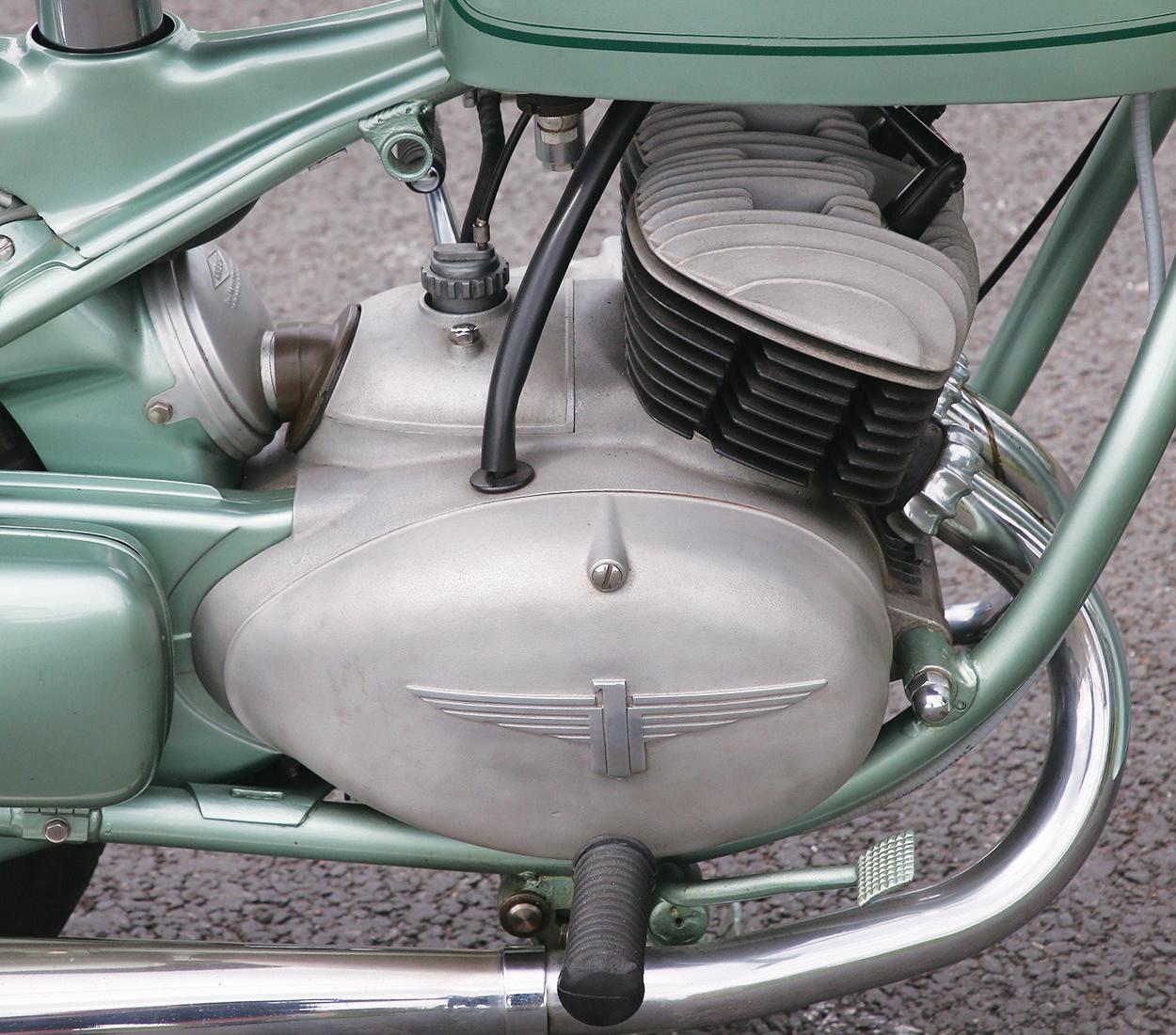

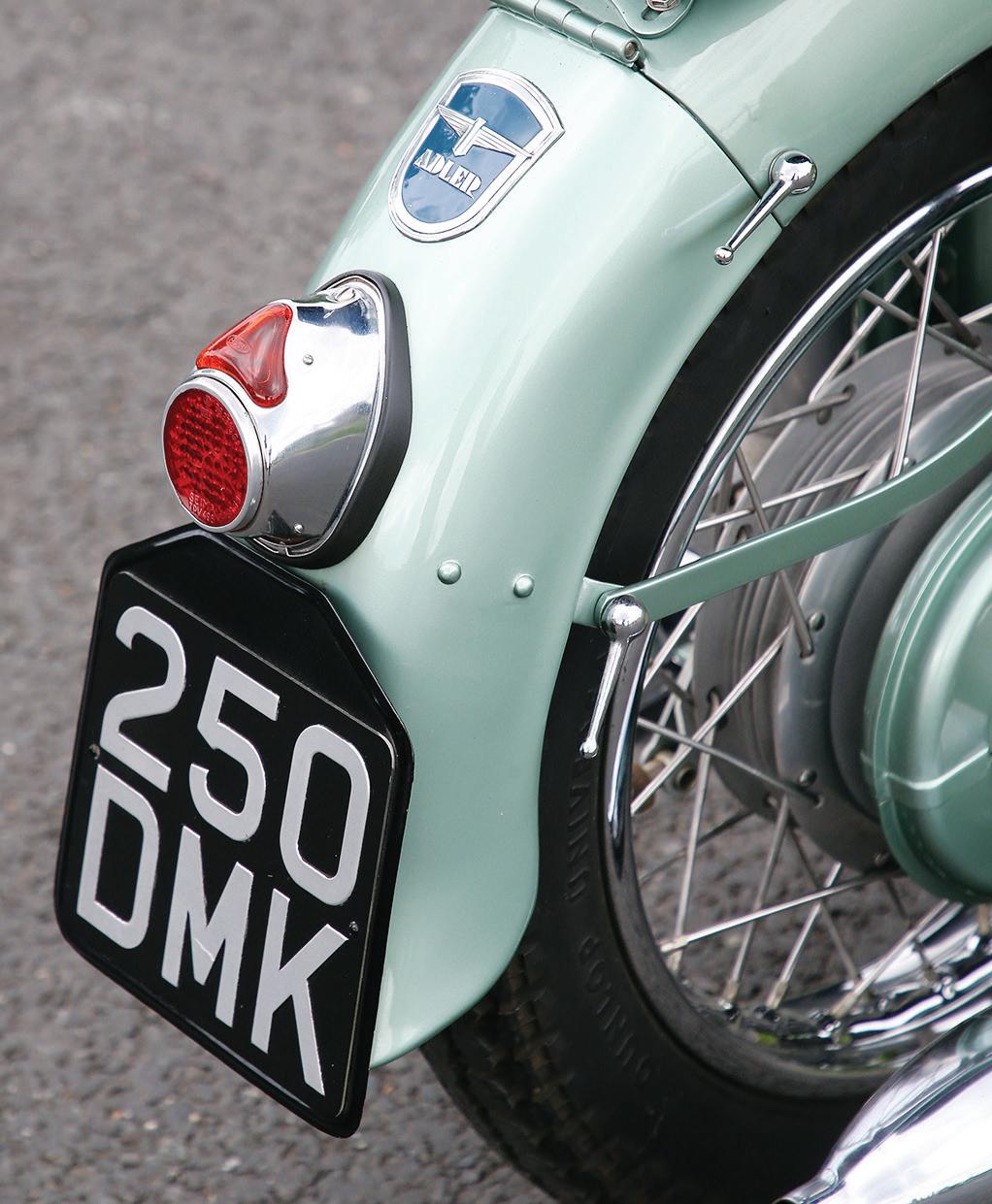

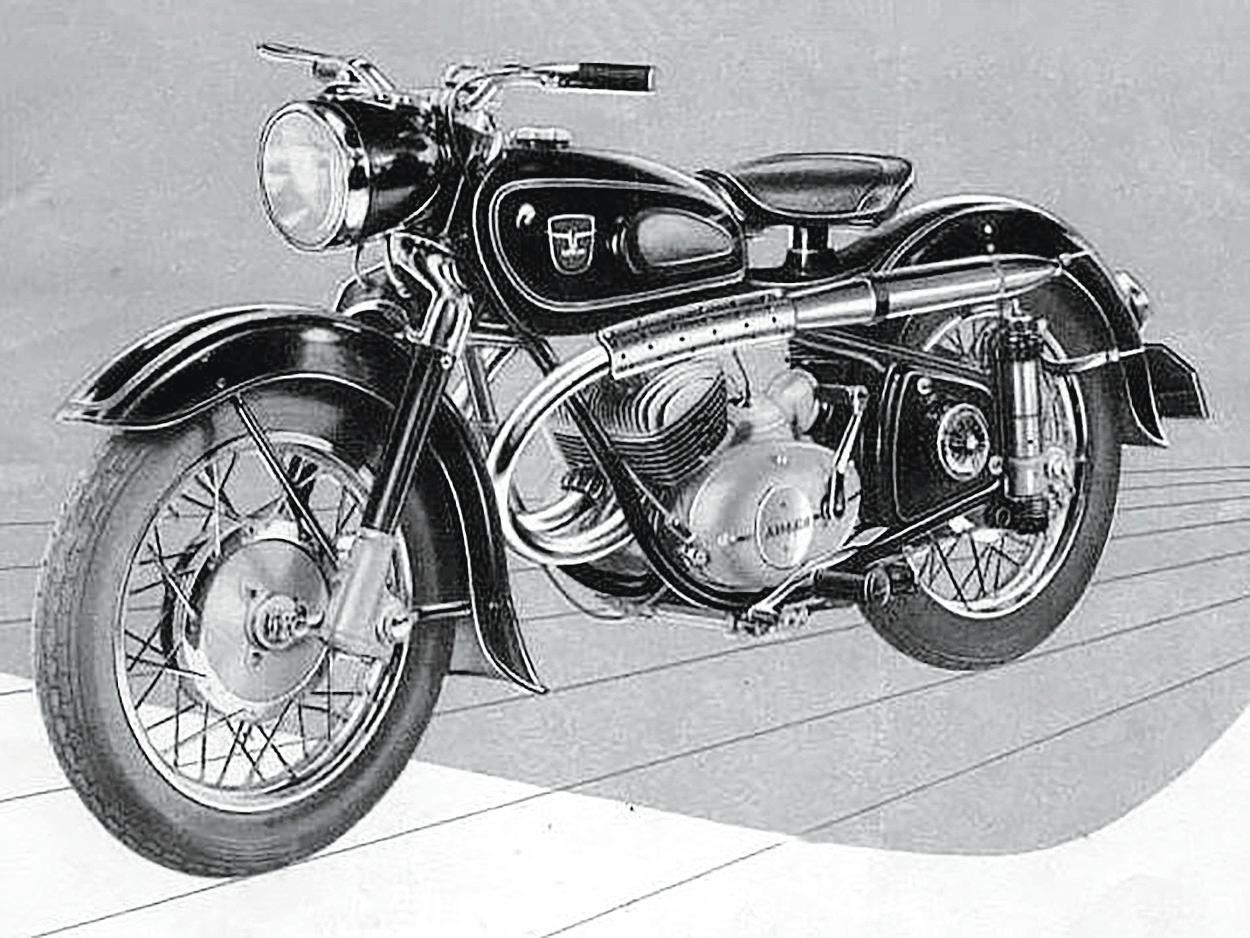

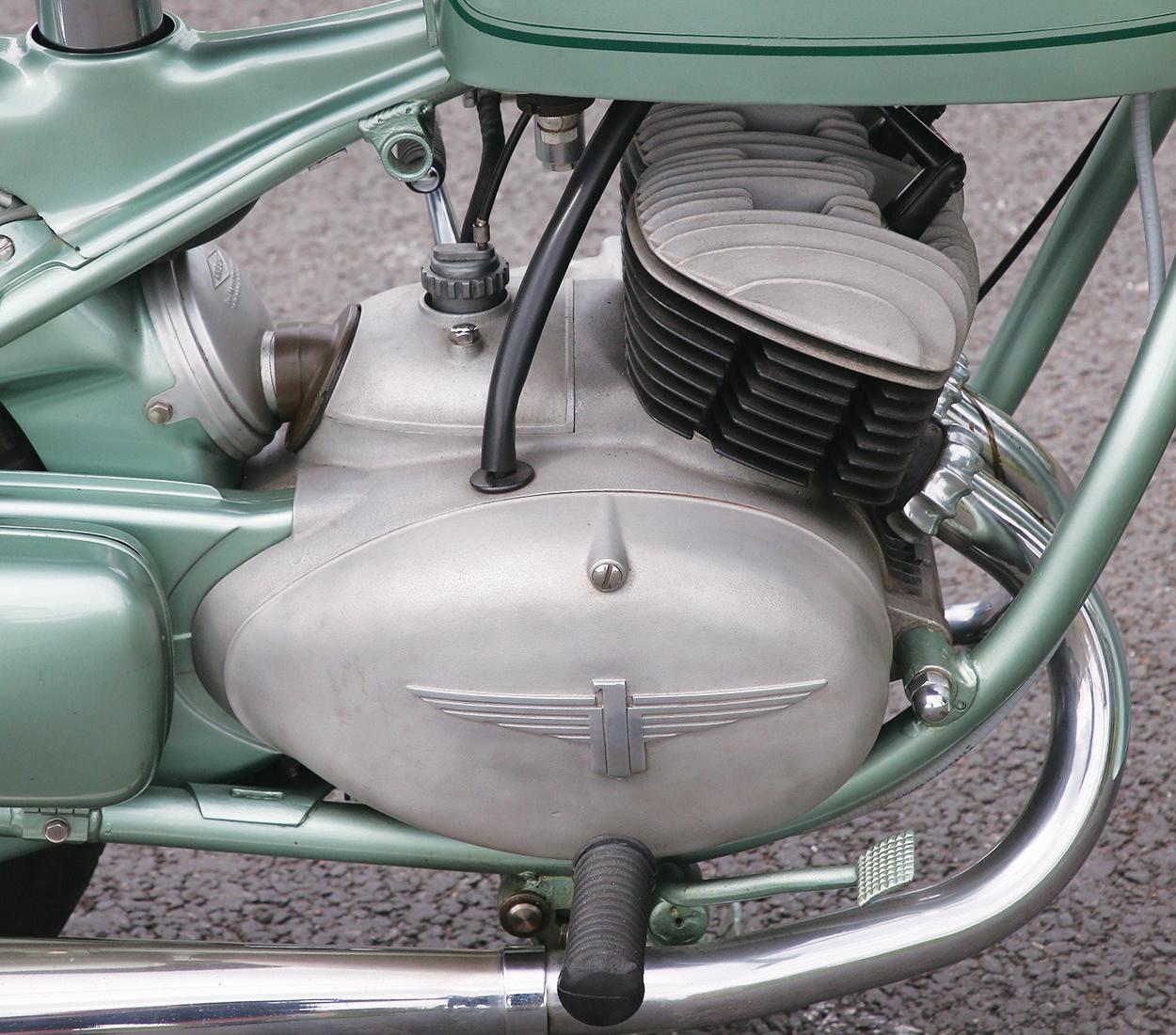

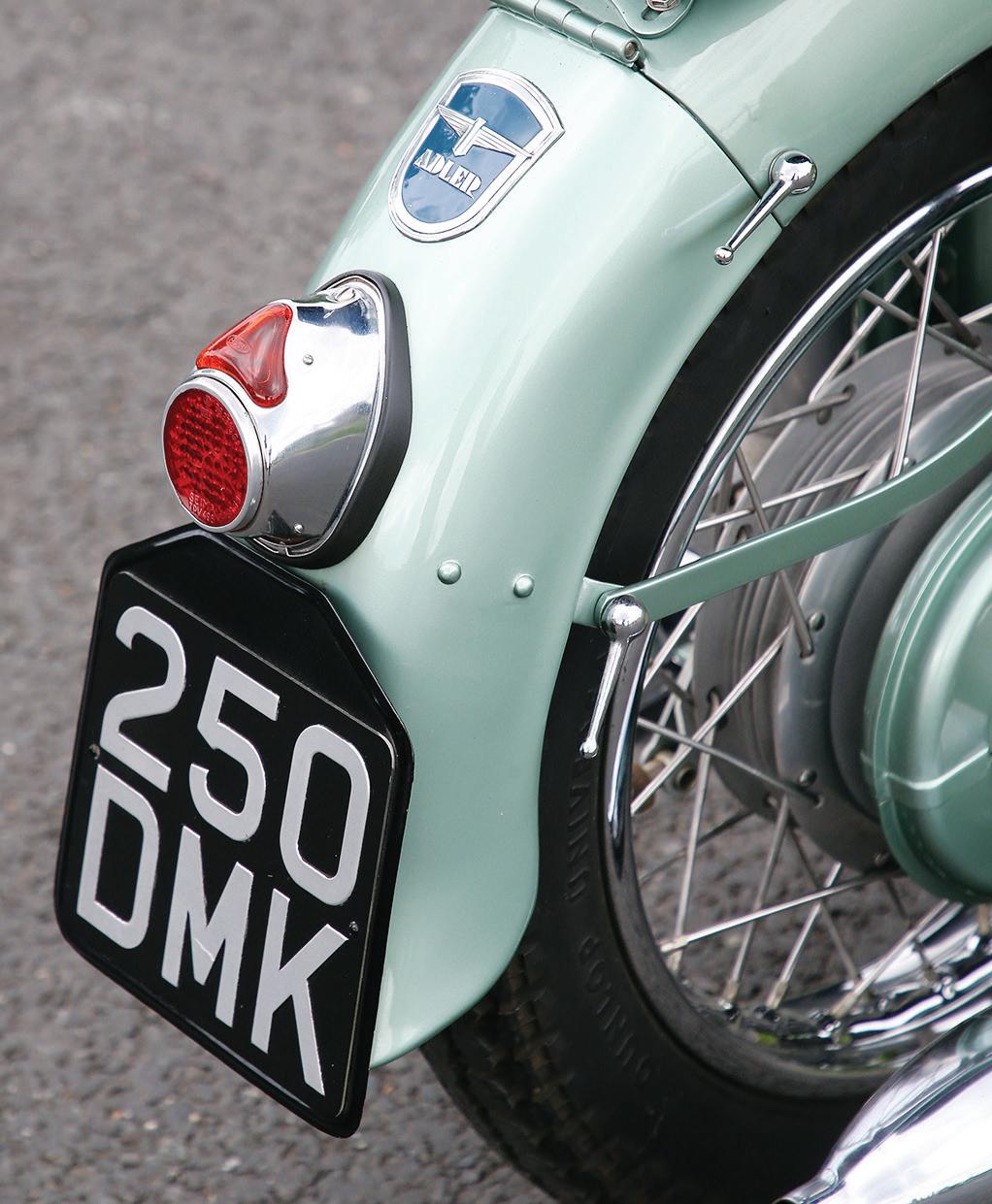

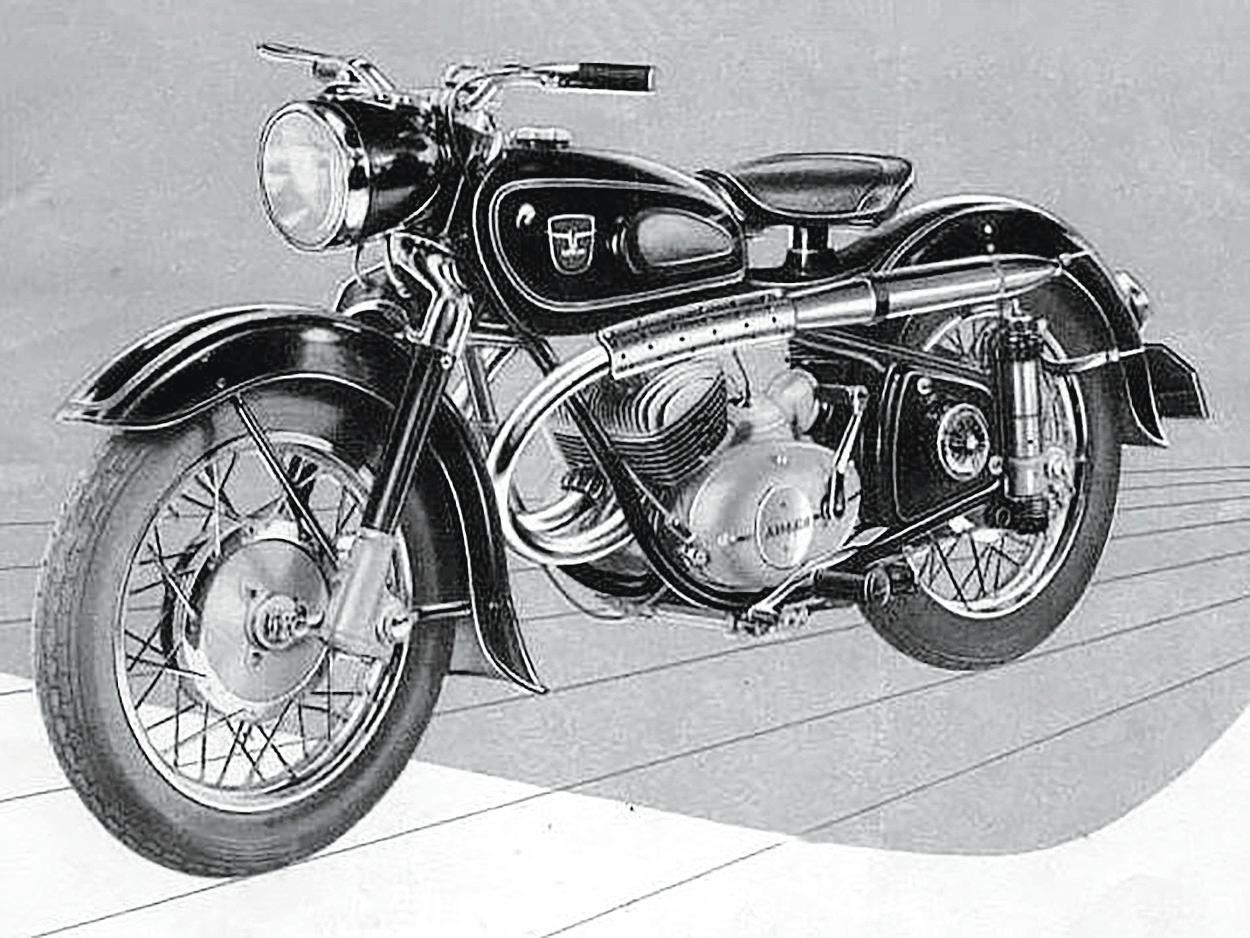

52 TWO-STROKE TEMPLATE: 1955 ADLER MB250

The parallel-twin 2-stroke engine has arguably delivered more thrilling performance to more people at an affordable cost than any other twowheeled 20th century engine format.

61 JERRY AND THE JERSEY DEVIL

A half century on a 1966 Honda 305 Scrambler.

8 ON THE RADAR

We look back at three desert sleds, the Norton Nomad, the Matchless G11CS, and the Triumph TR6 Trophy.

66 TEST RIDE

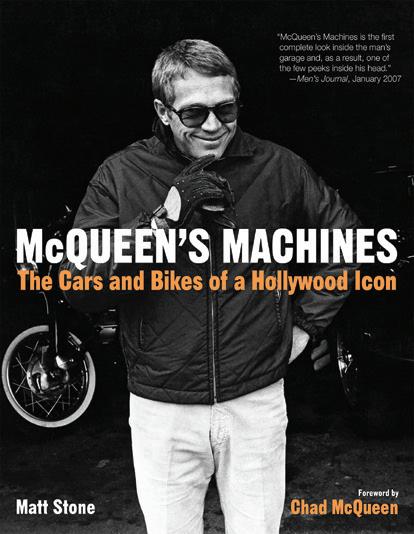

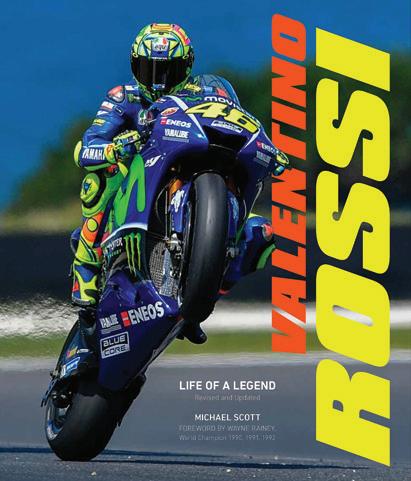

Alan Cathcart tells us all about Ultimate Collector Motorcycles.

ON THE WEB!

Motorcycle Classics Ready To Ride Giveaway

Get on the road with this cool collection of motorcycle gear valued at $2,400. Enter for a chance to win this package at MotorcycleClassics.com/ sweepstakes/ready-to-ride

70 CALENDAR

Where to go and what to do this fall.

72 DESTINATIONS

Visit the beautiful New Jersey Pine Barrens.

80 PARTING SHOTS

Remembering the San Jose Mile — THE Mile.

JEFF BARGER

the

being one of the

shows in the country.

lucky find of an amazingly

READY TO RIDE: 1975

S3A

after riding a H1 to

school,

Baugrud decided to find another

triple.

FEATURES

10 CLASSIC SCENE: THE 2023 QUAIL MOTORCYCLE GATHERING This year

Quail continued the tradition of

premier motorcycle-specific

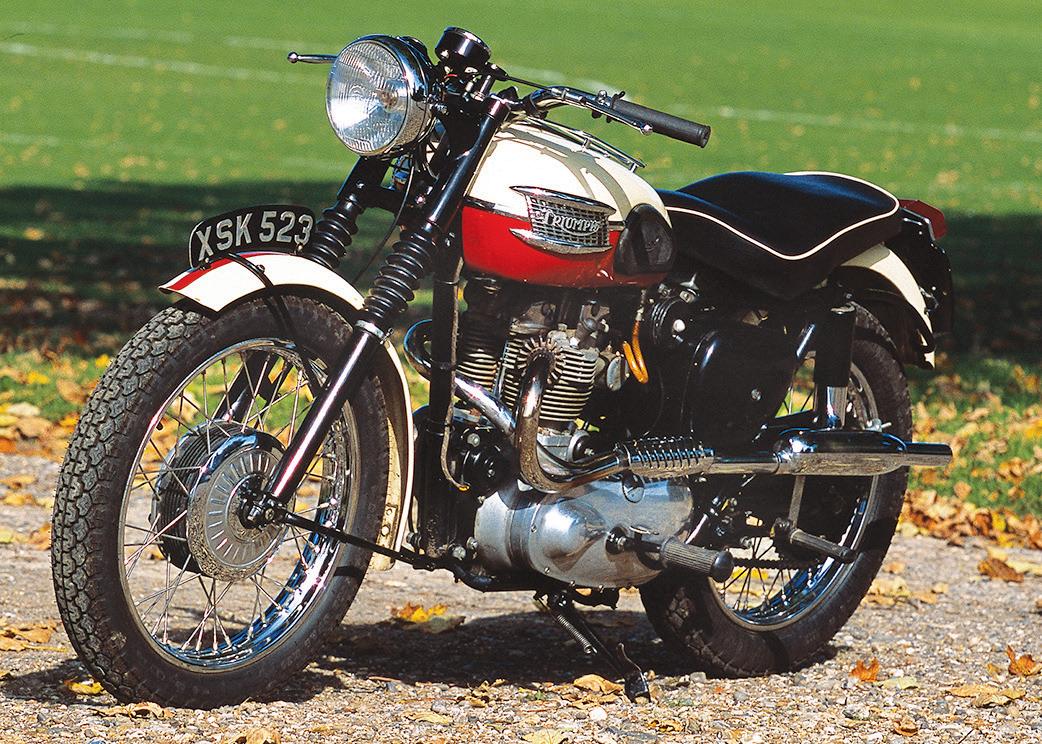

14 THE RESCUE OF THE AVOCADO: 1970 TRIUMPH TR6R A

original Triumph. 22

KAWASAKI

Decades

high

Steve

Kawi

30 THE 2023 MOTO GIRO D’ITALIA

Roaming Tuscan roads on classic motorcycles.

Steve Baugrud goes back in time. See Page 22.

2 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS September/October 2023

Cars lie to us. MOTORCYCLES TELL US THE truth — WE ARE SMALL, AND EXPOSED, AND PROBABLY MOVING TOO FAST, BUT THAT’S NO REASON NOT TO ENJOY EVERY MINUTE of EVERY RIDE. America’s # 1 MOTORCYCLE INSURER 1-800-PROGRESSIVE | PROGRESSIVE.COM from Season of the Bike

Progressive Casualty Insurance Co. & affiliates. Quote in as little as 3 minutes

by Dave Karlotski

The end of an era

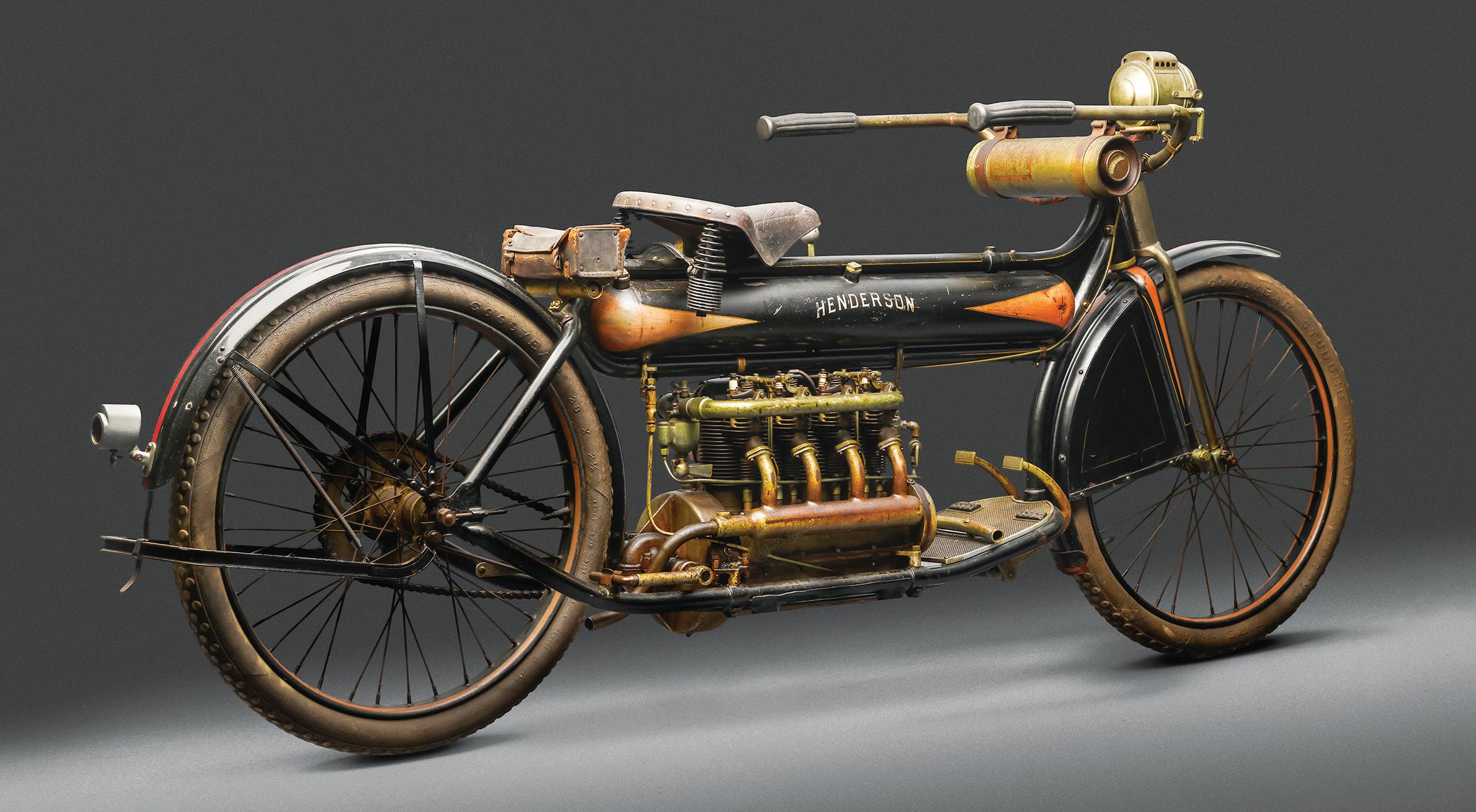

We here at Motorcycle Classics, along with everyone else in the motorcycle community, were saddened a few months back at learning the news: The National Motorcycle Museum in Anamosa, Iowa, will be closing its doors for good in early September.

While the museum has been a non-profit since its beginning in 1989, it has always been the home of many motorcycles from John and Jill Parham, founders of J&P Cycle.

What began with 40 bikes in an old storefront in downtown Anamosa grew to a larger, 500-plus motorcycle collection after the museum's move in 2010 to a repurposed larger building near Highway 151. More space not only allowed for the acquisition and display of more motorcycles, but it also provided room for exhibits and loans from other collections. And while those cycles will be going back to their homes, many bikes from the Parham's personal collection will go up for auction.

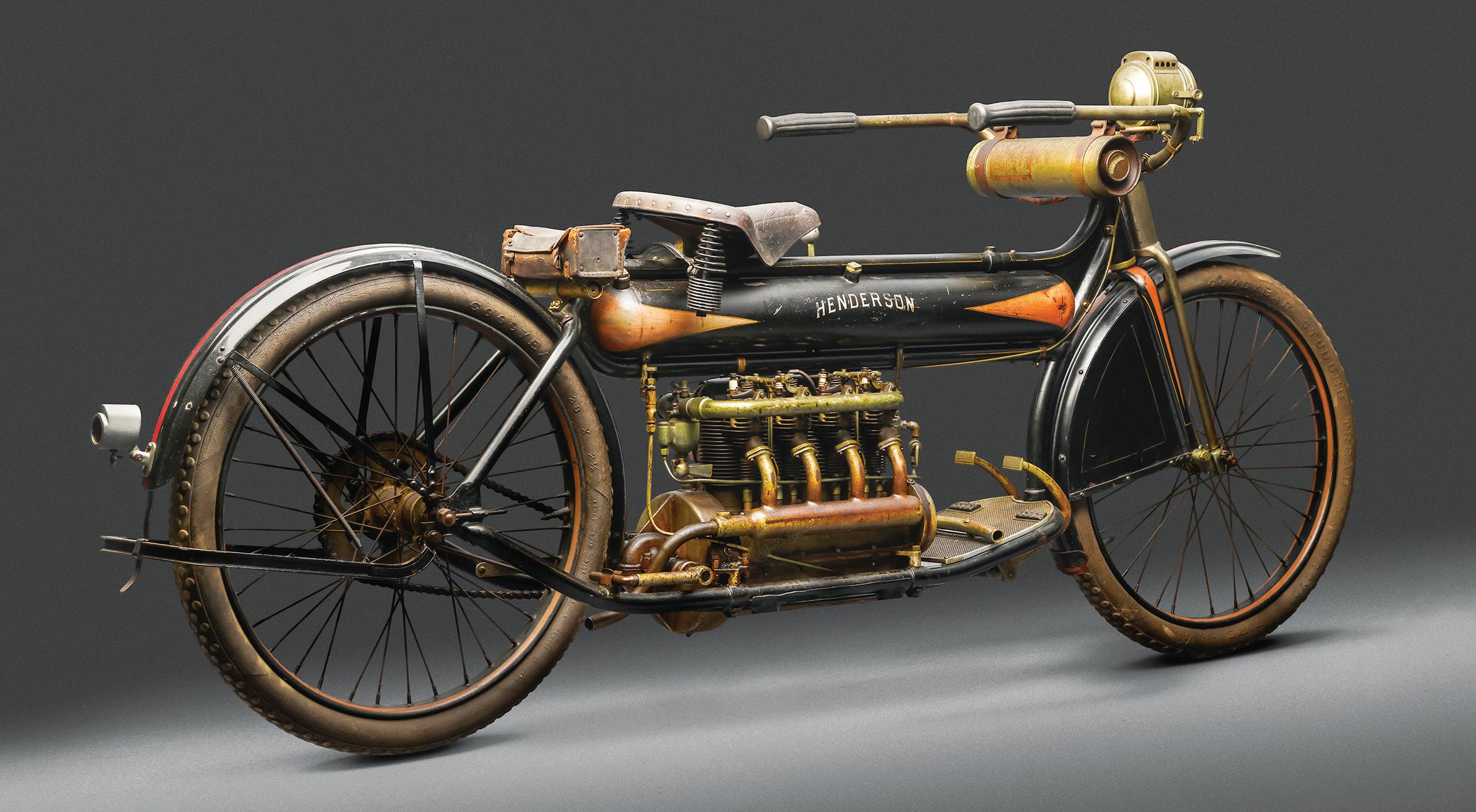

Mecum Auctions will be presenting the John Parham Estate Collection at the National Motorcycle Museum, Wednesday, Sept. 6, through Sunday, Sept. 9. The auction begins with the Road Art, some 1,000 lots encompassing more than 6,000 pieces in total. One standout piece of the Road

Art collection is a life-size bronze sculpture by artist Jeffrey Decker. The piece depicts a 1937 Harley-Davidson EL being ridden by Joe Petrali. The piece was created especially for John Parham in 2002 to honor Petrali’s record-setting Daytona run.

Another famed piece of the Road Art collection will be a helmet owned and engraved over a period of some 30 years by artist Von Dutch. He began engraving the helmet in the early 1960s as a sort of history of his motorcycle ownership, and it was one of his most prized possessions.

More than 300 motorcycles from the collection will also be sold, starting on Friday. Highlights include several Brough Superiors and a handful of Vincents, but mostly a vast collection of early American motorcycles. Harley-Davidsons of nearly every decade since the company began are represented, including a 1909 H-D single. A 1915 Flying Merkel, a 1912 Indian single and a 1939 BMW R12 are all sure to draw a great deal of attention.

The entire list of bikes can be viewed at mecum.com/auctions

Cheers,

®

LANDON HALL, EDITOR-IN-CHIEF lhall@motorcycleclassics.com

CHRISTINE STONER, ASSOCIATE EDITOR

RICHARD BACKUS, FOUNDING EDITOR

CONTRIBUTORS

JEFF BARGER • JOE BERK • ALAN CATHCART

NICK CEDAR • KEL EDGE • DAIN GINGERELLI

COREY LEVENSON • MARGIE SIEGAL

ROBERT SMITH • PHILLIP TOOTH

GREG WILLIAMS

ART DIRECTION AND PREPRESS

MATTHEW STALLBAUMER, ART DIRECTOR

ADVERTISING DIRECTOR

BRENDA ESCALANTE; bescalante@ogdenpubs.com

WEB AND DIGITAL CONTENT

TONYA OLSON, WEB CONTENT MANAGER

DISPLAY ADVERTISING (800) 678-5779; adinfo@ogdenpubs.com

NEWSSTAND

BOB CUCCINIELLO, (785) 274-4401

CUSTOMER CARE (800) 880-7567

BILL UHLER, PUBLISHER CHERILYN OLMSTED, CIRCULATION & MARKETING DIRECTOR

BOB CUCCINIELLO, NEWSSTAND & PRODUCTION DIRECTOR

BOB LEGAULT, SALES DIRECTOR RANDY SMITH, MERCHANDISE MANAGER

TIM SWIETEK, INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY DIRECTOR ROSS HAMMOND, FINANCE & ACCOUNTING DIRECTOR

MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS (ISSN 1556-0880)

September/October 2023, Volume 19 Issue 1. MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS is published bimonthly by Ogden Publications, Inc., 1503 SW 42nd St., Topeka, KS 66609-1265.

Periodicals Postage Paid at Topeka, KS and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Ogden Publications, Inc., 1503 SW 42nd St., Topeka, KS 66609-1265.

For subscription inquiries call: (800) 880-7567

Outside the U.S. and Canada:

Phone (785) 274-4360 • Fax (785) 274-4305

Subscribers: If the Post Office alerts us that your magazine is undeliverable, we have no further obligation unless we receive a corrected address within two years.

©2023 Ogden Publications Inc. Printed in the U.S.A.

In accordance with standard industry practice, we may rent, exchange, or sell to third parties mailing address information you provide us when ordering a subscription to our print publication. If you would like to opt out of any data exchange, rental, or sale, you may do so by contacting us via email at customerservice@ ogdenpubs.com. You may also call 800-880-7567 and ask to speak to a customer service operator.

®

SHINY SIDE UP

4 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS September/October 2023

A 1937 Brough Superior SS80, one of three Broughs in the Parham auction. MECUM AUCTIONS

over the next 20 years.”

Love for the Mystery Ship

Kudos for an outstanding cover and story about Craig Vetter and the Mystery Ships (July/August 2023)! As an architect and industrial designer, I have always been fascinated by Craig’s innovative solutions.

I also enjoyed Robert Smith’s very thorough background on the Ariel side hack rig ( Something on the Side ). I had a similar unit when I was living in Denver in the 1980s. I was the campaign manager for the election of Federico Peña for Mayor (he won). I frequently drove him to various civic events in the rig which always got lots of smiles and thumbs up. I think it was a 600 single. I wish I knew where to look for some of those old photos. Yes, as Robert points out, it was dark burgundy!

I was also delighted to read Clement Salvadori’s piece about the early Honda Scrambler. Clement was the first moto journalist I ever took on one of our Lotus Tours, which was to Rajasthan, India, in 1997.

Burt Richmond/Chicago, Illinois

Remembering the CBX

I enjoyed the July/August issue of Motorcycle Classics and the article on the CBX. Like many people, having owned a CBX I have some experience with it. I thought the article

was very fair. Not really a great motorcycle, but it had its features and good points. I enjoyed the time I had with one as the owner. In May 1978 I had just bought a Suzuki GS1000EC. Later that summer I saw the Honda CBX. WOW. I could have had that if I just waited a little. Yes, 1978. The first model year CBX was 1979, but it was available in dealers mid to late summer 1978. There was a story at the time (it may or may not be true) that the release was delayed due to head gasket problems and two additional M6 screws were added. That moved the release from early 1978, so it got a model year of 1979 with early release for a 1979 model. Anyway, the 1979 model was available for about a year and a half until the improved 1980 model was released more or less on time.

I kept the 1978 GS1000 and put 130,000 miles on it over the next 20 years. Probably a good choice versus jumping ship to the CBX. The CBX I owned was an insurance sale bought in the 1990s. So I finally had the CBX I lusted over. It needed some work and was an interesting restoration project. I rode it some but when it became more valuable than I could afford to keep, I sold it. I got about half of what they are currently going for. Thanks for the article.

Ralph Noble/Poulsbo, Washington

Police Indians

Several weeks ago I was admiring a neighbor’s Indian motorcycle. I told him my father rode an Indian motorcycle in the 1930s and 1940s when he was a member of the Pennsylvania State Patrol, which became the Pennsylvania State Police.

My neighbor recently gave me a copy of your July/August 2022 magazine, and on Page 31 you write that Pennsylvania purchased 450 Indian Scouts for various duties. I thought your readers may be interested in the enclosed photo taken at the Pennsylvania State Police Academy in Hershey, Pennsylvania. I cannot date the picture, but it is when they were still Pennsylvania Highway Patrol. My father, Cpl. Thomas Betsko is in the forefront, second from the left.

I believe one of the motorcycles is on display in the museum at the academy in Hershey.

Robert Betsko/Sun Lakes, Arizona

READERS

AND RIDERS

“I kept the GS1000 and put 130,000 miles on it

6 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS September/October 2023

DISTINCTIVE. HAND-CRAFTED. BEAUTIFUL.

INSPIRED BY THE CLASSIC CUSTOM LOOK, BEAUTIFULLY EXECUTED BY TRIUMPH’S WORLD-CLASS DESIGN AND MANUFACTURING TEAMS.

With a unique update and a major engine development for the exciting Thruxton RS, this vibrant new Chrome Edition showcases hand-crafted beauty, with a classic full chrome tank and stylish Jet Black paint scheme. Available for one year only, each Chrome Edition motorcycle perfectly showcases the craft and capability of the dedicated teams that perfected the skill of chrome detailing over many years, complementing the Thruxton RS’s dominating style. Own the new pinnacle in beauty, performance and sophistication from $17,445.00.

Discover the entire Chrome Edition lineup at triumphmotorcycles.com

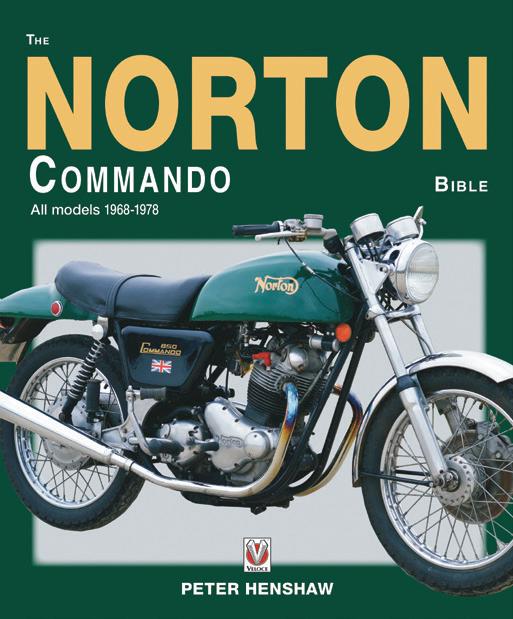

Special Sled: 1958-1960 Norton Nomad

The term desert sled has now become cemented into the motorcycle lexicon alongside café racer, chopper, bobber, adventure, cruiser and the rest. But the desert sled wasn’t born in a marketing meeting: it was in the Mojave Desert.

America’s western deserts are unforgiving places full of surprises. Rocks, sand dunes, sinkholes, dry rivulets, levees, all with a side of cactus and rattlesnake. But they also lack speed limits and intersections, making them ideal for off-highway racing. Perhaps the highest profile proponent of desert racing in the classic era and one of its fiercest competitors was, of course, Steve McQueen, who espoused the racer’s philosophy in the movie Le Mans: “Racing ... it’s life. Anything that happens before or after, it’s just waiting.”

Perhaps the archetypal desert racer of the era was the 650cc Triumph Trophy. The Trophy started out as a rigid-framed 500cc trials bike using the all alloy, square-barrel “generator” engine that had been installed as an auxiliary power unit in Britain’s World War II bombers. The 500 proved itself in the 1948 International SixDays event, when the British team won the top prize on Triumphs (hence the name “Trophy”).

But trials are relatively slow speed events, and more power was needed for desert racing. That arrived with the 650cc Trophy-Bird, using the engine from the Thunderbird. But there was another problem: The Triumph sprung hub frame fitted to their street bikes was unsuitable at speed on the rough. Then in 1954, the Trophy specification solidified around a new swinging arm frame. With appropriate modifications to stock machines by the customer/racer (relaxed steering rake, a longer swingarm, removing mufflers and other extraneous parts and strengthening what was left), the desert sled as it became known was born.

Meanwhile over at Norton, race supremo Joe Craig’s focus was circuit racing and the single-cylinder Manx; but his control over the race department ended with his retirement in 1954, freeing up funds for development of the Dominator twins. This

resulted in the launch of Norton’s own Desert Sled, the 596cc Nomad in 1958. The Nomad’s engine was developed from the Dominator 99, and featured dual Amal 276 Monobloc carbs and an alloy cylinder head with bigger intake valves

NORTON NOMAD

Claimed power 36hp @ 6,000rpm

Top speed 95mph (est.)

Engine 596cc air-cooled, OHV parallel twin, 68mm x 82mm bore and stroke, 9:1 compression

Transmission Chain primary, wet multiplate clutch, 4-speed gearbox, chain final drive

Weight N/A

Price now $5,000-$15,000

and high compression pistons. In this spec, the Nomad made 36 horsepower at 6,000rpm compared with the Domi 99’s 31 horsepower at 5,750rpm. It featured magneto ignition, 6-volt alternator electrics and was topped with a gas tank borrowed from the Matchless G80CS scrambler. (Norton had been part of Associated Motorcycles since 1952.)

The non-unitized drivetrain with Norton/AMC gearbox was housed in a new frame developed for strength and based on that of the sidecar-tug Model 77, but with a tubular engine cradle rather than the 77’s forged item. A new oval-tube swingarm was designed to fit around a wider rear tire. The front fork was a hybrid using Roadholder components (long stanchions, short sliders, external springs and alloy damper rods). Wheels were 19-inch rear and 21-inch front with

Years produced 1958-1960

ON THE RADAR 8 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS September/October 2023

A Nomad (with non-stock seat) brought $13,200 at the 2023 Vegas Mecum auction.

knobby tires. Alloy fenders, wide handlebars, full-width alloy hubs and siamesed exhaust completed the specification.

In all, around 350 Nomads were produced between 1958 and 1960 almost exclusively for the North American market with a limited number going to Australia. A batch of about 40 were built in 1960 around a tuned version of the 500cc Dominator 88 engine. The 500 differed from the 600 in its frame number prefix

(16 for the 500cc, 15 for the 600). The 500 Nomad also had a black seat with white sides, with this pattern reversed for the 600.

One of the first Nomads to arrive in the U.S. was entered in the challenging Big Bear Run in 1958, finishing eighth out of 822 starters, proving its off-road chops. But the Nomad only lasted three seasons, eventually replaced by the 750cc Atlas Scrambler, N15CS and P11.

The challenge with finding and restoring a Nomad is the small number produced, and its use of many unique parts, some of which are unobtainable and may have to be fabricated. That has limited the appeal of Nomads, and therefore restricted their resale value. But the rising awareness and collectibility of classic desert racers means now may be the time to buy! MC

CONTENDERS More alternatives to the Nomad

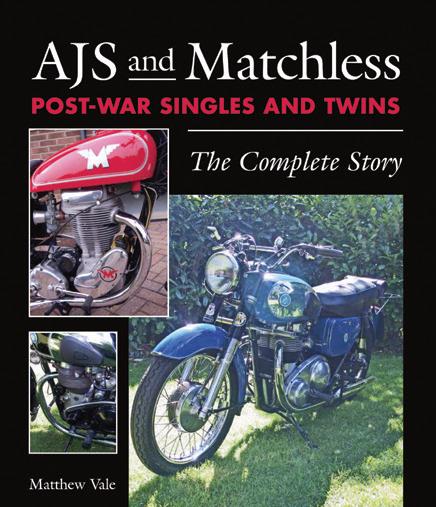

1958-1961 Matchless G11CS/G12CS

Matchless also enjoyed early success in the Big Bear Run, finishing first, second and third in 1954 using G80CS singles with Bud Ekins in front. But as a clue to the future, Gene Fox finished fifth on an AJS Model 20 “Spring Twin,” sister to the 500cc Matchless G9 twin.

So for 1958, AMC launched its own Desert Sled, the G11CS with a tuned 600cc twin developed from the G11 of 1956, installed in a motocross-style frame derived from the G80CS scrambler. The CS model featured a siamesed exhaust system, “western” handlebars and knobby tires. There was a choice of small or large gas tanks, and 19-inch or 21-inch front wheels. The G11CS lasted just one year before being replaced by the longer-stroke 650cc G12CS.

• Years produced: 1958 G11CS/ 1959-1961 G12CS

• Claimed power: 37hp @ 6,800rpm/42hp @ 6,600rpm

• Top speed: 100mph/ 106mph (est.)

• Engine: 593cc (72mm x 72.8mm bore and stroke)/646cc (72mm x 79.3mm) air-cooled, OHV parallel twin

• Transmission: Chain primary, wet multiplate clutch, 4-speed AMC gearbox, chain final drive

• Weight (dry): 381lb/390lb

• Price now: $6,000-$12,000

The G12CS came with a 3-gallon alloy gas tank, alloy fenders, 5-pint oil reservoir, modified front fork based on AMC’s Teledraulic units, dual rear shocks and highlevel exhaust. But in spite of running on three main bearings, the crankshaft proved inadequate for the power demands made on it, and future AMC big twins, like the G15/N15 CS and P11 were built around the 750cc Norton Atlas engine.

1956-1962 Triumph TR6 Trophy

The TR6 Trophy was essentially a grown-up version of the 500cc TR5 with a 650cc Tiger 110 engine. However the TR6 featured a new alloy cylinder head for better temperature control, a smaller 3.25 gallon gas tank, a shorter seat quickly dubbed the “ironing board,” a 20-inch front wheel and a waterproof Lucas KF2C competition magneto. The headlight assembly was quickly detachable, and exhaust was handled by siamesed high pipes on the left side.

Three stock “Trophy-Birds” were entered in the 1956 Big Bear Run with Bill Postel, Bud Ekins and Arvin Cox riding. The trio finished 1-2-3. The TR6 quickly became the winning machine for desert racing. Cycle magazine tested a 1956 TR6 over the course of a week and found it to be completely reliable with only an occasional cough from the carburetor.

For Eastern U.S. enduro competitors, Triumph introduced the TR6/A with a 19-inch front wheel, 8-inch front brake with air scoop, low level exhaust and magneto with auto advance. The original TR6 continued in the West as the TR6B until it was replaced by the unit construction TR6SR and T120C from 1963 onward.

• Years produced: 1956-1962 (Pre-unit construction)

• Claimed power: 42hp @ 6,500rpm

• Engine: 649cc air-cooled, OHV parallel twin, 71mm x 82mm bore and stroke

• Transmission: Chain primary, wet multiplate clutch, 4-speed gearbox, chain final drive

• Weight (dry): 370lb (168kg)

• Price now: $5,000-$18,000

www.MotorcycleClassics.com 9

“The challenge with finding and restoring a Nomad is the small number produced.”

THE 2023 QUAIL MOTORCYCLE GATHERING

Two-Wheeled Glamour on the Greens

The 13th annual event was held on Saturday, May 6, 2023, at the Quail Lodge and Golf Club in Carmel, California. According to the event’s organization, more than 3,000 people attended with 250 or so motorcycles on display. There had been a threat of rain in the days leading up to the event, but thankfully the weather cooperated, and it was a perfect day for sightseeing on the lawn. This year, there were 29 awards given in 19 categories. In

addition to the traditional categories (American, British, Italian, Japanese, other European, competition, custom/modified, choppers and bicycles/scooters), there were three special categories this year: Italian singles, 1970s Vintage Muscle and “Bring on the Baggers.” As in previous years, evaluation of the show bikes was overseen by head judge Somer Hooker and a team of about 40 judges. Awards were presented by Somer and perennial emcee Paul “The Vintagent” d’Orleans.

Best of Show this year was an Italian 1939 Miller-Balsamo 200cc single owned by San Franciso architect John Goldman. Beautifully restored by Zen House in Point Arena, California, it’s one of only a handful left intact in the world. The “Spirit of the Quail” Award went to Robb Talbott for his 1956 AeroCapriolo Corsa 75, which also won the Italian Single class. The AMA

10 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS September/October 2023

TThe Quail Motorcycle Gathering continues as one of the premier motorcycle-specific shows in the country.

Story and photos by Corey Levenson

Robb Talbott’s class-winning 1956 AeroCapriolo Corsa 75.

Motorcycle Hall of Fame Museum Heritage Award went to Wayne Rainey for his 1971 Yamaha Mini Enduro 60. It was his first competition bike and bristled with go-faster modifications.

This year’s honoree as “Legend of the Sport” was Wayne “Bubba” Shobert. He’s a three-time AMA Grand National Champion (1985, 1986 and 1987) and the 1988 AMA Superbike Champion, all won while riding Hondas. Chris Carter (owner of Motion-Pro) brought Bubba’s 1987 championship-winning Honda RS750D and fired it up to the delight of Bubba and the crowd.

Wayne Rainey and Eddie Lawson joined Bubba on stage, and they engaged in an entertaining chat, sharing war stories from their days on track in the 1980s with Gordon McCall, the Quail Gathering impresario.

I was on the team judging the Custom/Modified Class which

Clockwise from left: This fellow is the original owner of the BSA. He’s been driving the bike and the truck for 50 years. A Ducati single flat-track racer. A 1948 BMW R35 — a fine example of the highquality bikes at the Quail. This MV Agusta single is curvaceously Italian. A pair of participants prep a Vincent Comet for judging.

was won by a 2020 custom built by Max Hazan. The bike was built around a pair of supercharged 350cc Velocette singles. From conceptualization to fabrication, the machine was spectacular and typical of the extremely high quality of Max’s work. His Vincent Rapide-based special won Best of Show at last year’s Quail Gathering. I wish I could have heard the blown bi-Velo run but, alas, ‘twas not to be …

If you haven’t been before, it’s worth considering a trip to this event. The venue is beautiful, the bikes are extraordinary, and the attendees are an interesting bunch. The Quail Motorcycle Gathering is usually held the first Saturday in May, which would put next year’s edition on Star Wars Day, May 4th, 2024. Keep an eye on the event website for further details: peninsula.com/en/ signature-events/events/motorcycle MC

www.MotorcycleClassics.com 11

12 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS September/October 2023

Left: Frank Scurria with his homebuilt 350cc Ducati race bike. Right: Max Hazan and his blown twin 350cc Velocette — the Custom/Modified Class winner.

Left: Admiring a lovely 1940 5T Triumph Speed Twin. Right: Bubba Shobert’s Championship-winning Honda RS750D. Below: Wayne Rainey, Gordon McCall, Bubba Shobert and Eddie Lawson reminiscing.

Clockwise

John Goldman’s 1935 Motoconfort M5C Grand Sport 500 — a French beauty. Former World Roadracing Champions Wayne Rainey and Eddie Lawson. Left

Somer Hooker, Paul d’Orleans and owner John Goldman with the Best-ofShow-winning 1939 MillerBalsamo 200 Carenata. A sharp Norton 750 Commando S heading a nice line-up of classic BMWs, including a R90S.

www.MotorcycleClassics.com 13

from left:

to right:

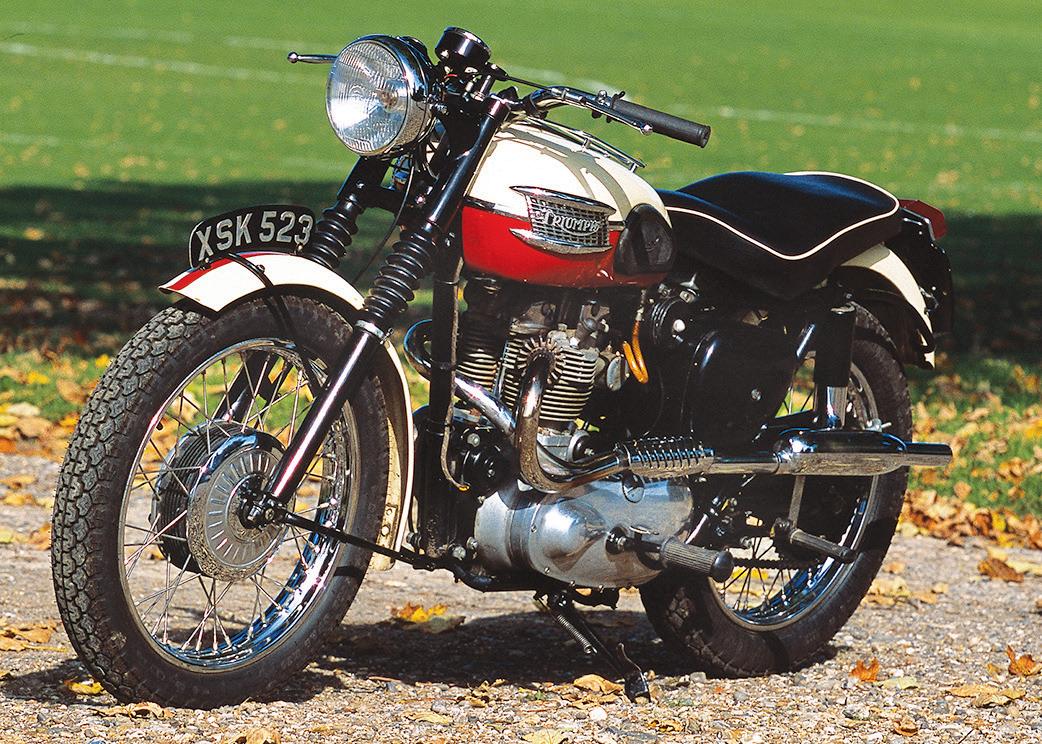

THE RESCUE OF THE AVOCADO

1970 Triumph TR6R

Story by Margie Siegal

Photos by Nick Cedar

TThe knights, resplendent in shining armor (they spend eight hours a week polishing) dismounted and walked to the door of the shabby warehouse. Knocking loudly on the door, they shouted they were there for The Avocado. The door was opened a crack, and a beady eye was seen. “Whaddya want,” a voice snarled. The first knight stuck a mailed foot in the opening. “We are here for the Avocado,” he repeated loudly.

Enough of Dungeons and Dragons. The actual story of how Dennis Etcheverry rescued a green 1970 Triumph TR6R from the clutches of a strange and sketchy individual is entertaining enough.

Dennis is a master welder who is a partner in Norman Racing, a service facility for high-end sports cars. After hours, he collects motorcycles, mostly British. Even if he is not actively interested in buying, Dennis likes to look at the motorcycles for sale advertised in Craigslist. Some five or six years ago, Dennis was idly scanning the Craigslist ads. He saw a green 1970 Triumph that looked promising, and called the number listed in the ad.

A TR6R is a single carburetor version of the Triumph twin. “When I was a kid,” says Dennis, “Everyone wanted a Bonneville, the dual-carb twin with splayed intake ports. But the single-carb machines are much easier to maintain. There’s no carburetor synching. People who bought them used them for transportation, not racing, so when you do find a single-carb Triumph, it is less likely to have a worn out engine.”

Dennis says that the 1970 Triumph twins were “the last of the good ones.” Triumph motorcycles had become popular in the United States after World War II, and the British firm increasingly geared its offerings to the U.S. market, which bought style, chrome and horsepower, unlike the English, who wanted fuel economy and weather protection. Triumphs were sought after for desert racing in the Western states, and getting around and general mayhem everywhere else. In the 1950s, Triumph put out a quality product: warranty claims were low.

Looking back

The ancestor of the TR6 was the 650cc Tiger 110, introduced in 1954. It had swingarm rear suspension, a beefed up bottom end, a racing camshaft, and could top 100mph. It was followed in 1956 by the first of the TR6s, (sometimes known as the Trophy-Bird), which had an alloy head, a slimmer gas tank, a shorter seat, a wider rear tire and a waterproof Lucas magneto. This bike was aimed squarely at the Western desert campaigner, at a time where if you weren’t riding a Triumph in the hare and hound, you were not serious. Triumph started making East Coast models for enduro competition and wetter conditions and West Coast models for desert racing and drier conditions. As the Fifties progressed, most models got an easier to tune and more reliable Monobloc carburetor. Triumph also introduced tanks with stylish two-tone paint jobs. The TR6 came in two versions: a roadburner with low pipes, and a scrambler

www.MotorcycleClassics.com 15

with high pipes, which were sometimes joined by an offroad competition weapon with no lights and straight pipes.

By 1957, Triumph was selling 13 different models in the U.S. In 1958, Triumph outsold all other motorcycle manufacturers in the U.S. To put this in perspective, nobody was selling a lot of motorcycles — Harley-Davidson only sold 12,676 that year — but Triumph dealers were doing better than most.

Honda comes to America

1970 TRIUMPH TR6R

Engine: 649cc air-cooled 4-stroke vertical twin, 71mm x 82mm bore and stroke, 9:1 compression ratio, 43hp at 6,500rpm

Top speed: 103mph (period test)

Quarter mile: 14.2 seconds @ 92.1mph (period test)

Carburetion: 30mm (930) Amal Concentric single carburetor

Transmission: 4-speed, right foot shift, chain final drive

Electrics: 12-volt battery and coil

Frame/wheelbase: Single downtube cradle frame, swingarm rear/55.5in (1,410mm)

Suspension: Telescopic forks front, dual Girling gas shocks rear

Brakes: 8in (203mm) TLS drum front, 7in (178mm) SLS drum rear

Tires: 3.25 x 19in front, 4.00 x 18in rear

Seat height: 30.5in (775mm)

Weight (dry): 387lb (176kg)

Fuel capacity: 3.5gal (13.2ltr)

At this point, Honda entered the U.S. market, just as the first Baby Boomers reached driving age. Life completely changed for the U.S. motorcycle retailer. Honda had deep pockets as a result of its sales in Asia, and a number of other

Price then/now: $1,280 (est.)/$5,000-$15,000

advantages. Honda’s company culture was to reinvest profits in the product, instead of distributing them to stockholders, as did Triumph. Honda had a great deal more leverage over its suppliers than Triumph, who was treated as a sort of a stepchild by Lucas and other companies whose largest customers were automobile manufacturers. As a result, Hondas were built on state of the art machinery, and had bright lights, electric starters and no leaks. Honda could build 1,000 lightweights a day, while maintaining quality control standards. Honda also spent a lot of money on general interest advertising.

At first, the appearance of Honda, and then Suzuki, Yamaha, and Kawasaki, improved life for the American

16 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS September/October 2023

1970 TR6R (left) vs. 1970 Bonneville: simplicity vs. speed.

Triumph dealer. For the first time since the 1920s, motorcycling became socially acceptable. Small Hondas were easier to ride and maintain than the Triumph Cubs that had been the entry level motorcycle sold by Triumph. Many retailers started selling both Hondas and a British make, such as Triumph or BSA. Riders would start on a small Japanese motorcycle and graduate to a larger British twin. Triumph sales boomed. In the 1960s, America’s Triumphs made the grids of flat track races and road races, got their owners to work and school and went cow trailing and touring.

Triumph soldiers on

The situation was different in England, where motorcycles had been used for decades as a cheap car substitute. With the advent of inexpensive small cars and Japanese imports, the get to work rider switched from the home product to either a four-wheeler or a twowheeled import. As the Sixties progressed, Triumph pruned its

offerings to concentrate on what it thought would sell in its overseas markets, the largest of which was the U.S. However, it did not upgrade its machine tooling, which limited what could be produced. Over the decade, management began to change from people who knew and understood motorcycles to people who knew nothing of either bikes or the people who rode them. Management and labor became increasingly antagonistic.

Cycle World arranged a test of a TR6SC in 1965. The magazine was enthusiastic about the power generated by the bike (45hp @ 6,500rpm). The bike came without a headlight, but with stiff suspension and long travel forks. Muffler-free pipes exited above the rear axles. In 1963, Triumph had gone to unit construction of engine and gearbox, which Cycle World liked because there were fewer joints to leak, and its report noted the fact that the test bike stayed leak free in 600 miles of hard desert riding. Testers praised the

www.MotorcycleClassics.com 17

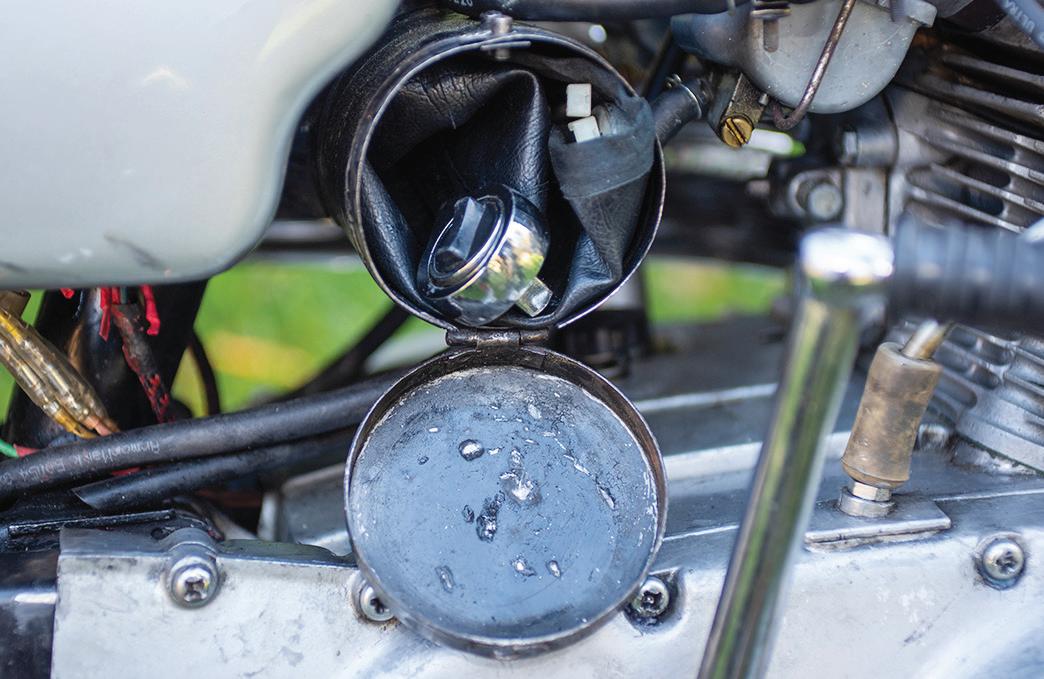

Big drum brakes effectively stop the bike.

A well-tuned Triumph is a joy to ride.

TR6SC’s ease of starting and ease of shifting. “But what we liked most about the Triumph special is that it is such fantastic fun to ride.”

Three years later, Cycle reported on the road going version of the TR6, the TR6R. Although the single-carburetor machine was not the beast to beat in drag races, testers stated that it was the most manageable and the most durable of the Triumph twins. Testers did not like the new Concentric carburetor and suggested it be replaced by either a Monobloc (the previous edition of the Amal) or a 30mm Japanese instrument. They did like the strong but light frame, the good handling and the double-leading-shoe 8-inch drum front brake with an air scoop.

1969 marked the debut of both the Honda 750, a powerful but well-mannered machine with a front disc brake and an electric starter, and the Kawasaki H1, a screaming 500cc 2-stroke, nicknamed “The Widowmaker.” Triumph had a triple-cylinder design ready to go in late 1963, but dallied around with styling changes and corporate inertia. Triumph was selling more bikes than ever — about 28,700 in 1967 — but failed to pay attention to quality control. Tooling was run until completely worn out. Warranty claims mounted.

Cycle revisited the TR6R in 1970. Its report on the 1970 TR6R was, in the main, positive. The starting was as easy as it had been in 1965, and the bike stood up to side winds, had almost no noticeable vibration up to 70mph, and was a pleasure to ride on twisty roads and around town. Over 70mph, the engine transmitted vibration through the seat, although rubber mountings on the bars quelled the tingle to the fingers. The tester commented that the taillight stopped working during the ride and there was a small leak. The color was Spring Gold, “a translucent avocado green.”

Last

year before big changes

1970 was the last year for the desert-racing-proven frame. The parent company in England had spent millions of dollars on an R&D center staffed by non-motorcyclists, who

The official name for this color is Spring Gold, but everyone refers to it as Avocado.

designed a new, and very tall frame and changed the look of the Triumph twins. Customers did not like the look of the 1971 Triumphs, and objected to the excessively high frame. No one had checked to make sure that the engine components would fit in the frame, resulting in a hasty redesign and delays in getting bikes to dealers.

The 1970 Triumph TR6R is therefore of interest to people who want to actually ride their vintage machines, like Dennis, which is why he followed up on the ad. There was only an answering machine on the other end when Dennis called. A day passed with no return call. Dennis mentioned the Avocado, as he began to think of the bike, to his friend Scott, who runs a motorcycle dealership by day and also collects Triumphs by night. Scott called, also got the answering machine, and left a message with the shop number.

The person whose phone was listed as the callback number called the shop, and got Scott’s wife, Juliana. “Oh s@#$, another Triumph!” (She is actually a good sport about Scott’s Triumph habit.) Juliana passed the phone over and Scott and Dennis made plans to see the bike, although the person on the other end sounded more than a little weird. The address was not in the best part of town.

The adventure begins

Scott and Dennis showed up to find the bike in a damp garage. They were glad they had decided to go together. The hairy and greasy person showing the bike (who turned out to not be the owner) was the sort of person who, if there is more than one in a bar, any thinking person backs out slowly. The actual owner was the mother of the girlfriend of the person showing the bike. Mr. Greasy was trying to ingratiate himself with Girlfriend’s family, who was not too thrilled about Girlfriend being seen with this guy, and was going to be a hero by selling the bike for the family. Problem was, he didn’t know the first thing about Triumphs, and couldn’t even start it.

The bike itself, however, made up for the seriously weird person who was trying to sell it. It was absolutely 100% original. The

18 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS September/October 2023

paint and bodywork looked strangely dull, which on investigation turned out to be due to a quarter-inch-thick coat of paste wax all over the chrome and paintwork. The paint and chrome under the wax was absolutely perfect. There was no rust anywhere. Dennis was able to start the Triumph on the third kick. It sounded wonderful. It had the original license plates from 1970.

One special item on the 1970 Triumphs was the taillight extension. The U.S. Department of Transportation decreed in late 1969 or early 1970 that motorcycle taillights had to extend beyond the end of the fender. Honda spent millions to reengineer the taillight assembly and fender. Triumph simply designed an extension

1970 Triumph Bonneville

In 1970, if you were the typical Triumph fanatic eyeing the latest and greatest from the Meriden factory, you would probably have walked right past the TR6R featured here and gone for the Bonnevilles. The twin-carb setup was originally an accessory offering, but when the splayed port head kits sold out, Triumph decided to incorporate the new head in a new model. The first T120 Bonnevilles appeared in 1959 and quickly became wildly popular Stateside. The 1970 model

for the taillight. This TR6R has the original (and rare) taillight extension, increasing the value of the bike.

Scott and Dennis opened negotiations. The sketchy seller seemed uncertain if he even wanted to sell the bike at all. The conversation went back and forth for a while. Finally, Scott lost patience. “Look,” he said. “We have a ramp, tie-downs, a truck and CASH. And we are not coming back.”

At this point, Mr. Greasy realized that Girlfriend’s family would be furious if he botched the deal, took the cash and handed the bike and its pink slip over. Dennis and Scott loaded the Triumph as fast as possible, jumped in the truck and ran.

Bonneville was good for more ponies (46 horsepower vs. 43 horsepower) and more top speed (108mph vs. 103mph) than the single-carb machine, and those with a need for speed overlooked the extra maintenance. “When I was a kid,” says Dennis Etcheverry, “Everyone wanted a Bonneville.” Bonneville lust has not gone away with the years, and the market for a classic Bonnie in good shape continues to be strong.

Shortly after he acquired the Avocado,

Dennis’ friend Scott found this unrestored and very original 1970 Bonneville in Oregon. The prior owner had used the bike as a template for a restoration, then decided to sell both the unrestored and restored machines. Another friend wanted the restored bike, and Dennis ended up with the Bonneville.

Dennis has been taking the two bikes to shows, enjoying the reactions of admirers. “No one can believe that both bikes are unrestored! — Margie Siegal

www.MotorcycleClassics.com 19

“We have a ramp, tie-downs, a truck and CASH. And we are not coming back.”

The twin-carb version of the 1970 Triumph.

Even better news

A couple of days later, Girlfriend’s mother called. She ranted for a couple of minutes about how she disliked Sketchy Boyfriend, and stated she was happy that the Triumph had gone to someone who would care for it. The bike had belonged to her father, now passed, who kept the bike in his living room and waxed it when he had nothing else to do. As he got older, his eyesight got worse, which explains why the bike was covered with paste wax. Girlfriend’s mother had the complete service records and was happy to send them over.

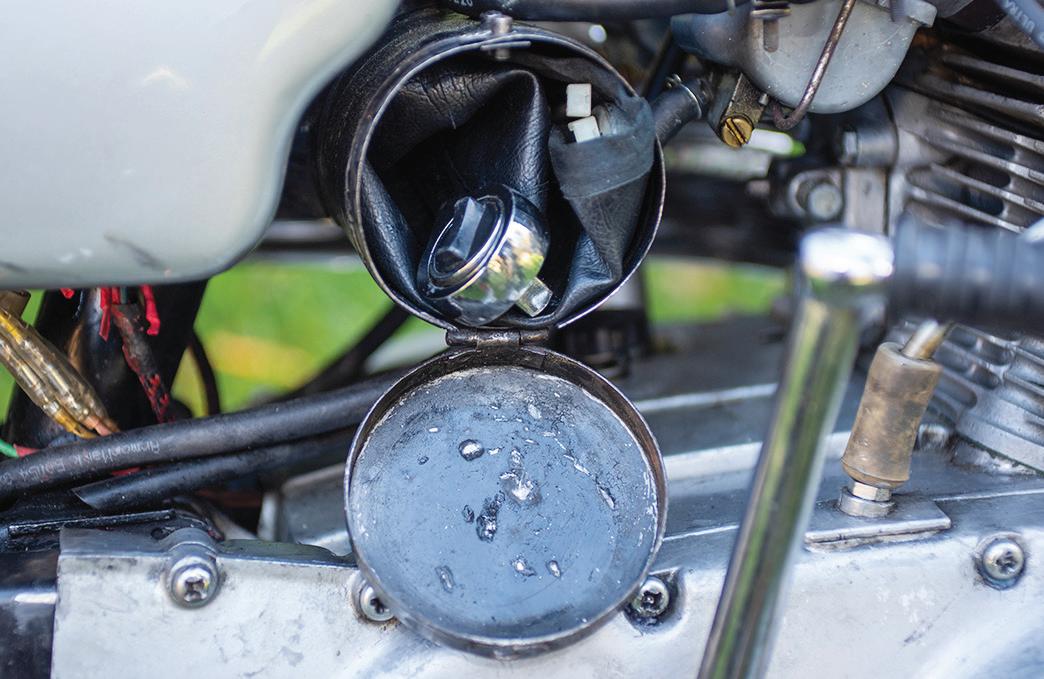

Meanwhile, Dennis went over his new prize. It took two days to get all the wax off. The bike needed tires, fuel lines and a change of oil. Under the wax, the bike was perfect. The service records arrived, with the original bill of sale. Per

the sales records, in 1970, the cost to finance a motorcycle was 16-18%. (Think about that when you complain about financing charges!) The last service on the bike was 40 miles before it was parked.

“It’s a very simple bike,” says Dennis. “Once you get the drill down, you can start the TR6R on the first or second kick. It needs premium gas. You turn on the gas, free the clutch, give it half choke and kick. The carb does not go out of tune. Change the oil every thousand miles. Parts availability is better than it was 20 years ago — Bloor (owner of the modern Triumph factory) sold the tooling to the right people.”

“The Avocado gets ridden a little bit — I have a lot of bikes — but what I mostly do with it is take it to shows. It has won at a lot of shows. No one believes it is that original.” MC

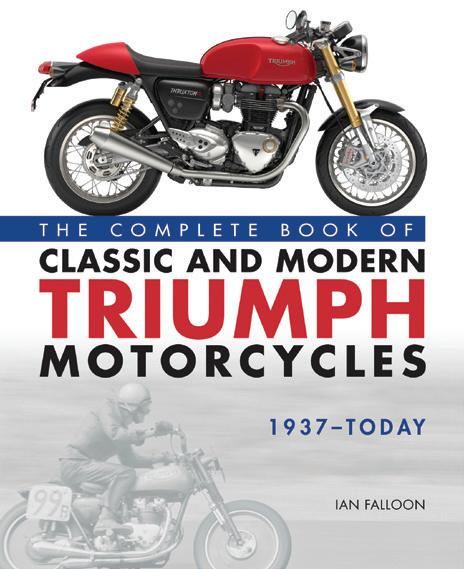

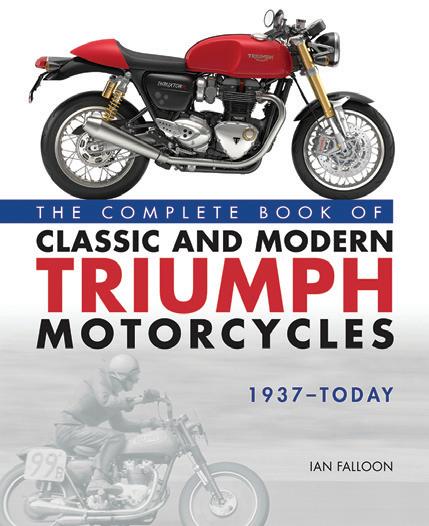

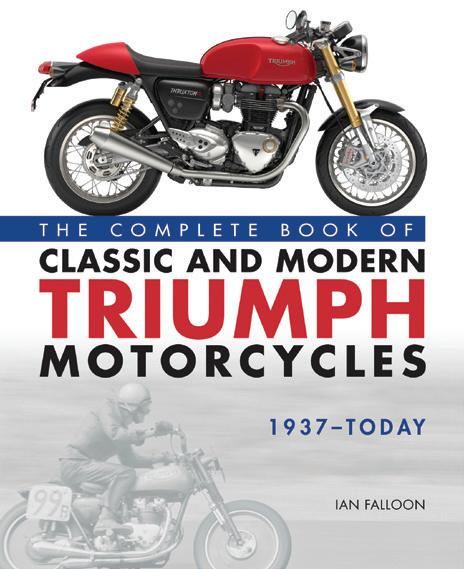

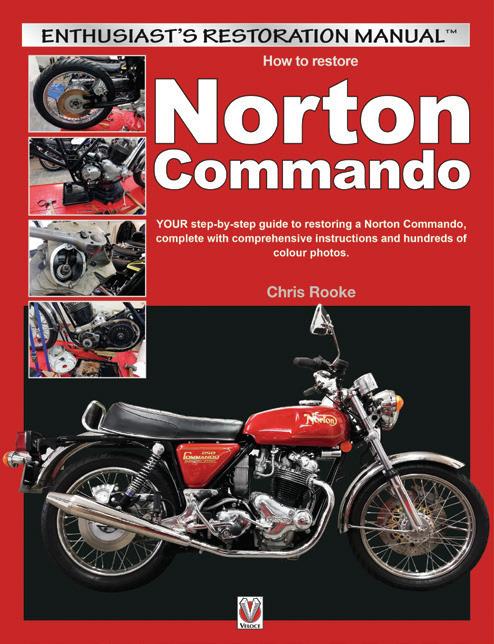

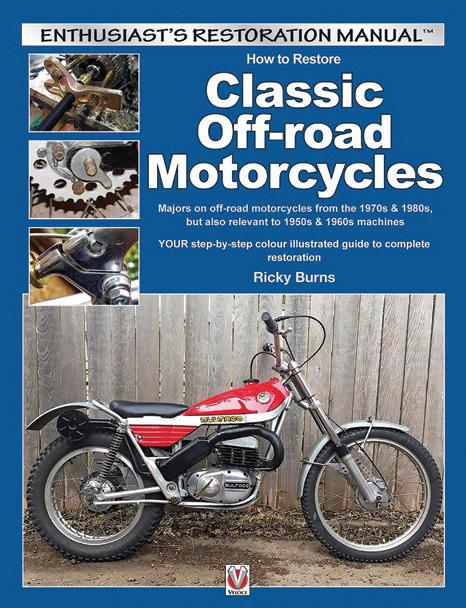

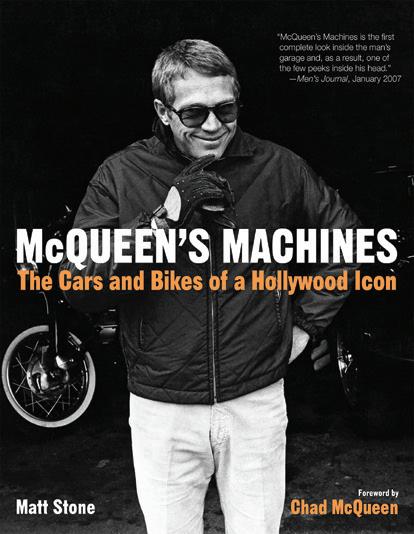

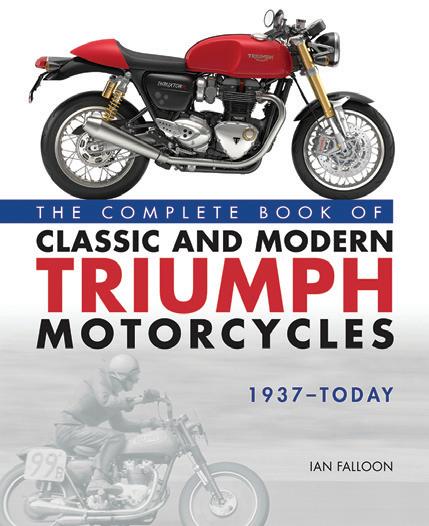

A Book No Triumph Fan Should Be Without

The ultimate reference for Triumph lovers and fans of British motorcycles, The Complete Book of Classic and Modern Triumph Motorcycles, 1937-Today collects all of the motorcycles from this iconic brand in a single illustrated volume. In this revised and updated edition, you’ll find the all-new Bonneville lineup introduced for the 2016 model year and other Triumphs through 2019. Written by respected Triumph expert Ian Falloon, this luxurious reference covers all of the major and minor models, with an emphasis on the most exemplary, era-defining motorcycles, but also features important non-production models. Detailed technical specifications are offered alongside compelling photography, much of it sourced from Triumph’s archives. This title is available at store.MotorcycleClassics.com or by calling 800-880-7567.

Mention promo code: MMCPANZ5. Item #10260.

20 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS September/October 2023

BIRMINGHAM, AL | OCTOBER 6-8, 2023 18th ANNUAL BARBER VINTAGE FESTIVAL JOIN US FOR THE 100th YEAR CELEBRATION OF BMW MOTORRAD AND BMW MOTORRAD DAYS AMERICAS! • Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum • Swap Meet with 500+ vendors • Bike Shows • Demo Rides • Free Motorcycle Parking • AHRMA Vintage Motorcycle Racing, Flat Track Racing and Off-Road Trials BARBERMUSEUM.ORG | @BARBERMOTORPARK | 877.332.7804

READY TO RIDE

1975 Kawasaki S3A

Story by Greg Williams

Photos by Jeff Barger

RRiding to high school aboard his brother’s 1974 Kawasaki H1 500 triple ensured Steve Baugrud was one of the coolest kids in class. By the time he was in 10th grade, Steve had been riding since he was 5 or 6 years old and he’d already earned plenty of motorcycle memories. But the 2-stroke H1 he rode to school was the first real street machine he’d spent much time on, and he wouldn’t soon forget the experiences.

Decades after last riding the H1 to classes, in 2021 Steve was actively in the market for a Kawasaki triple he could call his own. So, when an ad without any photos appeared on Cycletrader.com for a reasonably priced 1974 Kawasaki KZ400, he didn’t initially think anything of it — as the KZ is a 4-stroke twin-cylinder model. Inquisitively, though, he clicked and read the listing.

He was glad he did. “It said something like the bike had low miles and was from an original owner,” Steve recalls. “And then, it said something to the effect that ‘this is a beautiful 3-cylinder bike.’ And I was thinking, wait a minute, is this really a KZ400 twin?” Apparently, a dealership in Pennsylvania had taken the Kawasaki in on trade and posted the ad, and Steve called them up. “I asked if it was a triple, and he said, ‘Oh yeah, it’s a triple.’ Long story short, he texted me photos, and it was definitely an S3 400cc triple.” With that visual confirmation and with the bike still reasonably priced, Steve sealed the deal, hired a shipper, and had the Kawasaki delivered to his home in Waukesha, Wisconsin.

While not the larger 500cc triple like his brother Jeff’s machine, the S3 400 is in some respects a better motorcycle. A January 1974 Cycle World test of the then-new S3 said, “In our mind, the 400 is Kawasaki’s best three-cylinder buy. It handles much better than the 750 — in fact there is no comparison. It’s more economical than the 500 by a wide margin and still has enough performance to get you excited in the mountains.”

Looking back

Kawasaki’s line of triple-cylinder machines can trace their history back to 1969 and the powerful 500cc H1 Mach III. At that time, the H1 became a best seller thanks to the fact it could hit 60mph in just 4 seconds and offered a blistering top speed of 120mph. Based on that success, Kawasaki followed up with more triple-cylinder machines in 1971 with the 750cc H2, 350cc S2 and 250cc S1.

By 1974, the 350cc S2 became the 400cc S3 when Kawasaki enlarged the engine by taking the bore from 53mm to 57mm. A pressed together crankshaft in horizontally split cases turns on six bearings. Connecting rods mate to the throws via roller bearings, while the piston gudgeon pins are in needle bearings. “Oil for lubricating the engine’s internals is supplied by a plunger-type pump whose delivery rate is controlled by the amount of throttle opening and the engine rpm,” the Cycle World test notes. “This oil under pressure from the pump is delivered through check valves into the cylinder intake ports

www.MotorcycleClassics.com 23

1975 KAWASAKI S3A

Engine: 400cc air-cooled 2-stroke triplecylinder, 57mm x 52.3mm bore x stroke, 6.5:1 compression ratio, 42hp @ 7,000rpm

Top speed: 97mph (period test)

Carburetion: Three 26mm Mikuni VM

Transmission: 5-speed, wet multi-disc clutch, chain final drive

Electrics: 12v, battery and coil ignition (stock); Accent solid-state electronic ignition (upgraded)

Frame/wheelbase: Mild steel double front downtube/53.7in (1,365mm)

Suspension: Telescopic front fork, swingarm rear

Brakes: 8.9in (226mm) single disc front, 7.1in (180.3mm) drum rear

Tires: 3.25 x 18in front, 3.50 x 18in rear

Weight (dry): 339lb (155kg)

Seat height: 31in (780.7mm)

Fuel capacity: 3.7gal (14ltr)

Price then/now: $935/$4,000-$11,000

where it mixes with the incoming fuel/air mixture to lubricate the connecting rods and piston pin bearings.”

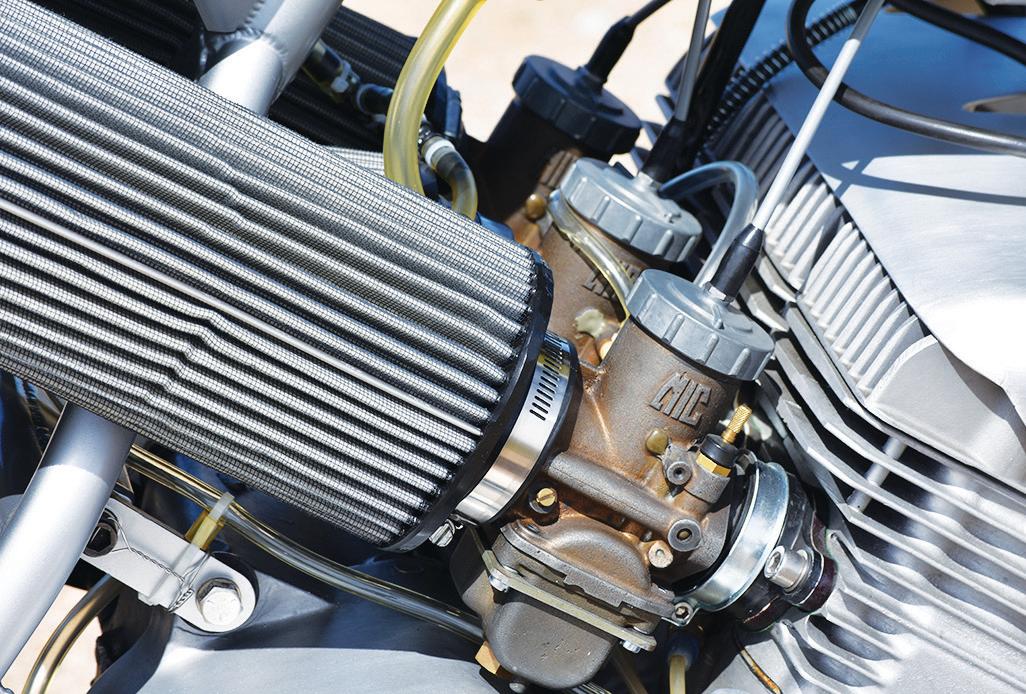

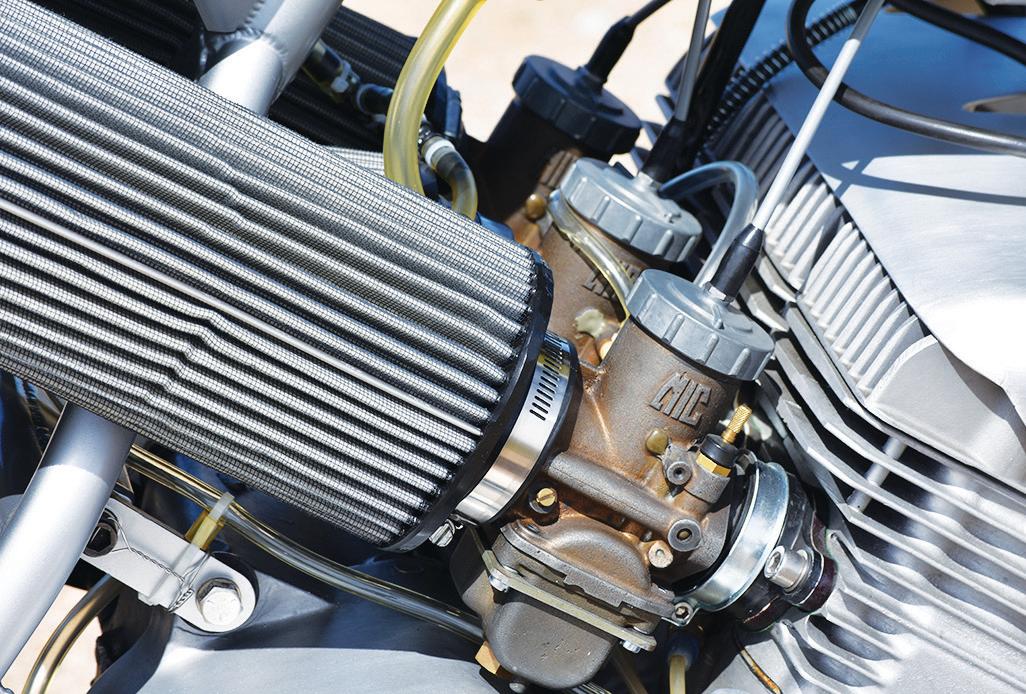

Handling intake chores is a bank of three Mikuni VM 26mm carburetors. Given substantial amounts of throttle, Cycle World’s tester said there was a significant amount of “intake roar,” something they felt could be handled with “better baffling at the air cleaner intake.” Ensuring sparks arrive at the correct moment, the S3 400 Kawasaki uses battery and coil technology with three sets of ignition points. Straight cut gears, meanwhile, transfer power from the crank to the 5-speed transmission. Cycle World’s tester claimed the gears were closely spaced and allowed “the engine to be kept in its power band while accelerating or blasting down a curvy road.”

Rubber mounting debuts

Kawasaki chose to rubber mount the revised 400cc triplecylinder engine in the double cradle frame in an overall package that weighed 339 pounds dry. Prior to 1974, all Kawasaki triple powerplants were solidly mounted in the chassis, causing significant amounts of vibration. The rubber mounting arrangement in the new S3 virtually quelled the vibes. “At low rpm, as when sitting at a stop light, you can see the engine moving around a little,” the Cycle World story continues, “but practically no vibration is felt through the footpegs at any speed.” When riding down the highway, the tester explained, there was a slight “tingle” in the rubber mounted handlebars. The stock handgrips exacerbated the

tingle, they said, and that would have been an easy fix with a pair of aftermarket grips.

The front brake was a single disc while a drum followed at the rear. These were laced into 18-inch rims front and rear and the machine was suspended by a hydraulic front fork and twin rear shocks. A 3.7 gallon gas tank sits atop the well-triangulated frame and 1.6 quarts of injection oil is carried in a tank on the right side of the bike. Produced for just two years, the 1974 S3 and 1975 S3A, 400 triples became the KH400s in 1976 and lasted until 1977 in the United States.

Our feature S3A

Steve knew from looking at the pictures prior to buying his 400cc triple that the 3-into-3 exhaust pipes and mufflers weren’t in great condition, and the paint, in a lime green color, was incorrect. A side panel was missing, and rather uniquely, pinstriped across the top of the tail section was the sentiment “Happy 50th Dad.” As delivered to Steve, though, the 400 appeared to be an honest low-milage machine; one that he could simply clean up and ride. He performed a compression

test, went through all of the systems, got the Kawasaki running, and rode it the summer of 2021.

“I got a reproduction side panel and my painter did a 98-percent job matching the green paint,” Steve says. “I had a running bike that looked decent, but at the back of my mind, the pipes didn’t look great and it wasn’t the right color.”

Another thing he learned was the Kawasaki was incorrectly identified on the title by the Pennsylvania DMV as a 1974 S3. His research showed it was in fact a 1975 S3A, and Steve petitioned the Wisconsin DMV to change it. He says, “I had to fight with them about that and they required all sorts of documents and a letter from Kawasaki USA.” He won, however, and the machine is now correctly titled as a 1975 Kawasaki S3A.

Also noteworthy is that the engine and frame numbers match, which isn’t very common on Kawasaki triples. “Rick Brett [Kawasaki triples guru] has a registry of triples from around the world, and he says that’s a one in one thousand chance that the engine and frame numbers will match — and mine do,” Steve explains.

www.MotorcycleClassics.com 25

Circa 1987, Steve rode his brother’s Kawasaki H1 to high school.

Recapturing some of his youth, Steve found and sympathetically restored a more rider-friendly 1975 Kawasaki S3A triple.

Movin’ on up

To take his S3A to the next level, Steve spent the late winter of 2021 and early 2022 sourcing parts. He located two NOS exhaust pipes, and a third one in really good condition that he had re-chromed. Instead of working with the gas tank — which had a scratch and a tiny dent — sidecover and rear tail section of the Kawasaki, Steve removed them, sold them, and acquired a tank and tail section that were in better shape. The side covers are reproduction, and Steve notes, “purists might not agree, but I think the reproductions are probably a little more durable. I’ve had so many old side panels with broken mounting tabs.”

Shiny bits

Of the paint, Steve says, “I think it had been painted a later model Kawasaki green. It definitely wasn’t the stock color.

In 1975, the stock colors were Candy Green and Candy Super Red. I liked the red the best and went with that.” Working with painter Nicholas Brouillard at HeavenlyCustoms in West Allis, Wisconsin, the replacement tank, tail section and aftermarket side covers were sprayed the correct Candy Super Red. Nicholas also laid down a decal set that Steve ordered from Rick Brett.

During this time, Steve stripped the Kawasaki completely down. He needed to repair a bracket on the right side of the frame that carries the mount for the footpeg. “Notoriously, on the 400s, those would bend and mine was bent in at about a 30-degree angle,” Steve says. With the engine out, Steve cleaned and touched up a few areas of the frame with black paint, but for the most part, the chassis still wears its original finish.

While the forks were off, Steve cleaned and serviced the components and rebuilt the sliders with new seals. The front

26 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS September/October 2023

Your source for Excel, Borrani and Sun Rims Azusa, CA Your contact: Silas Uhlmannsiek Stein-Dinse GmbH • Waller See 11 • 38179 Schwuelper, Germany + 49 (0)5 31 12 33 00 - 0 info@stein-dinse.com www.stein-dinse.com ORIGINAL SPARE PARTS... ... AND A HUGE RANGE OF ACCESSORIES! 608-862-2300 • info@mgcycle.com Our local partner: Fuel in the blood . Italy in your heart. DUCATI

fender was a 9 out of 10, Steve says, but it had some road rash at the front corner. He found a NOS replacement, and it was in near perfect condition. At the back of the machine, new shocks were added. The engine was never taken apart, as the compression was within spec and it had not been losing or burning any crankcase oil.

“The other thing about this bike is I wanted to ride it,” Steve says of his resurrection effort. “I wasn’t after a concours restoration, I just wanted to make it look as stock as possible and make it so it could be ridden reliably.” To that end, Steve updated all of the electronics, replacing the regulator and rectifier. He dispensed with the mechanical points and installed an Accent solid state electronic ignition system. Also replaced were the coils, plugs, high tension leads and caps. On the intake side of the equation, the carburetors were stripped, cleaned and fully serviced.

As far as Steve can tell, the seat is original Kawasaki vinyl and foam on the pan. When he bought it, the S3A showed just over 4,000 miles on the odometer and he believes that it is likely genuine. After his restoration, the Kawasaki now shows more than 4,800 miles.

It’s a fairly simple machine to bring to life. “Just flick the gas on, click half choke, and one or two kicks and it fires right up,” Steve says of the kickstart-only Kawasaki. “It’s got a thumb choke lever, and I’ll usually hold it at half for 20 seconds, let the choke out and let it warm up a minute longer and then go. With all of the new electronics it fires up and runs really well.”

He continues, “The ride is great, and it’s really quick. It’s super smooth, goes through all the gears well and it handles nicely and pulls well. It likes to rev, and it really wakes up at mid to upper throttle, pulling strongly from 5,000rpm to 9,000rpm.”

Taking Steve’s triple-cylinder Kawasaki story full circle, his brother Jeff still owns the H1 500, and Steve got to ride the bike he rode to high school again last summer. “It’s still a little bit scarier to ride, mostly in terms of handling. The 400 seems more refined and it’s a very nice triple to own. I’ll get out for short rides during the week, or slightly longer rides on the weekend,” he says, and concludes, “It’s great fun, and makes me feel like I’m back riding to high school again, just without any lectures or exams.” MC

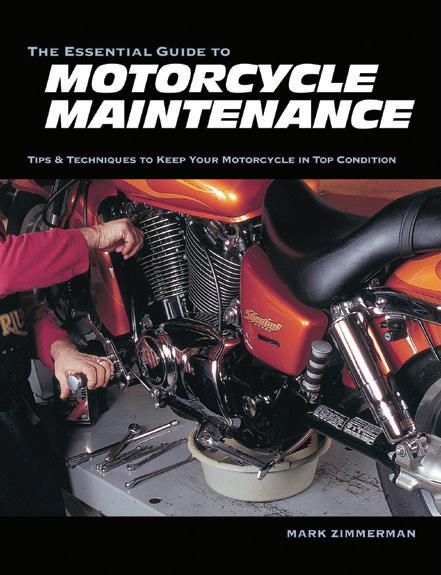

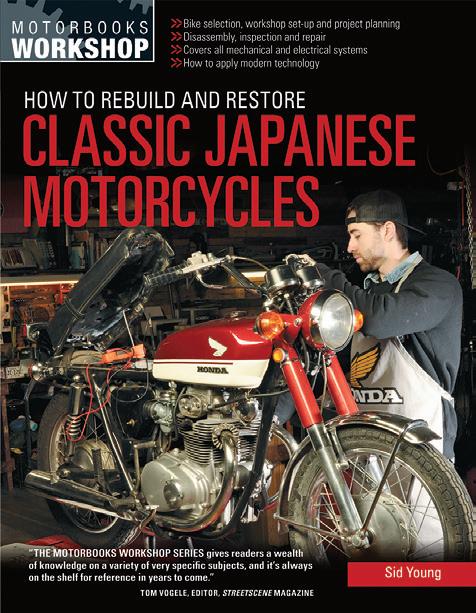

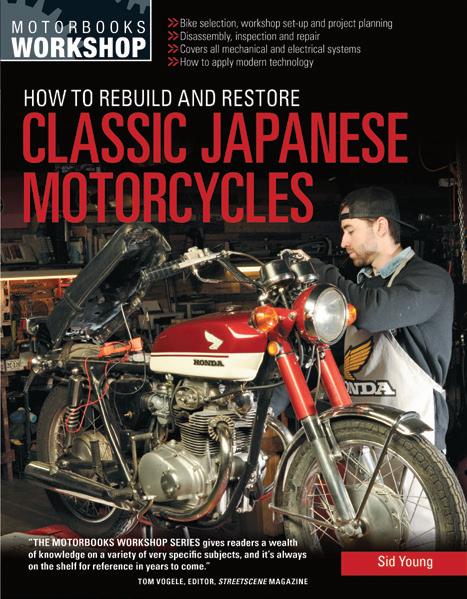

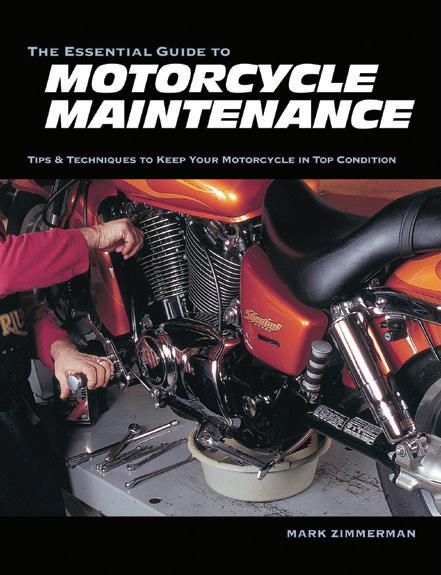

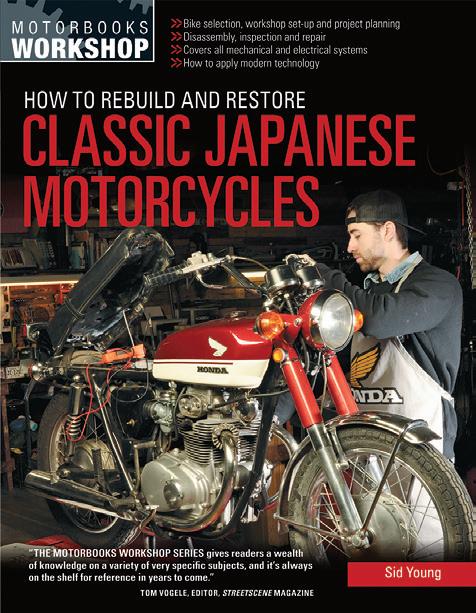

How To Rebuild and Restore Classic Japanese Motorcycles

Everything you need to know to restore or customize your classic Japanese motorcycle. Whether you want to correctly restore a classic Japanese motorcycle or create a modified, custom build, you need the correct information about performing the mechanical and cosmetic tasks required to get an old, frequently neglected, and often long-unridden machine back in working order. How to Rebuild and Restore Classic Japanese Motorcycles is your complete, hands-on manual, covering all the mechanical subsystems that make up a motorcycle. From finding a bike to planning your project to dealing with each mechanical system, How to Rebuild and Restore Classic Japanese Motorcycles includes everything you need to know to get your classic back on the road. Japanese motorcycles have been the best-selling bikes globally since the mid-1960s, driven by the “big four,” Honda, Yamaha, Suzuki and Kawasaki. This is the perfect book for anyone interested in classic Japanese motorcycles and prepping a bike to build a café racer, street tracker or other custom build. This title is available at store.MotorcycleClassics.com or by calling 800-880-7567. Item #10936.

28 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS September/October 2023

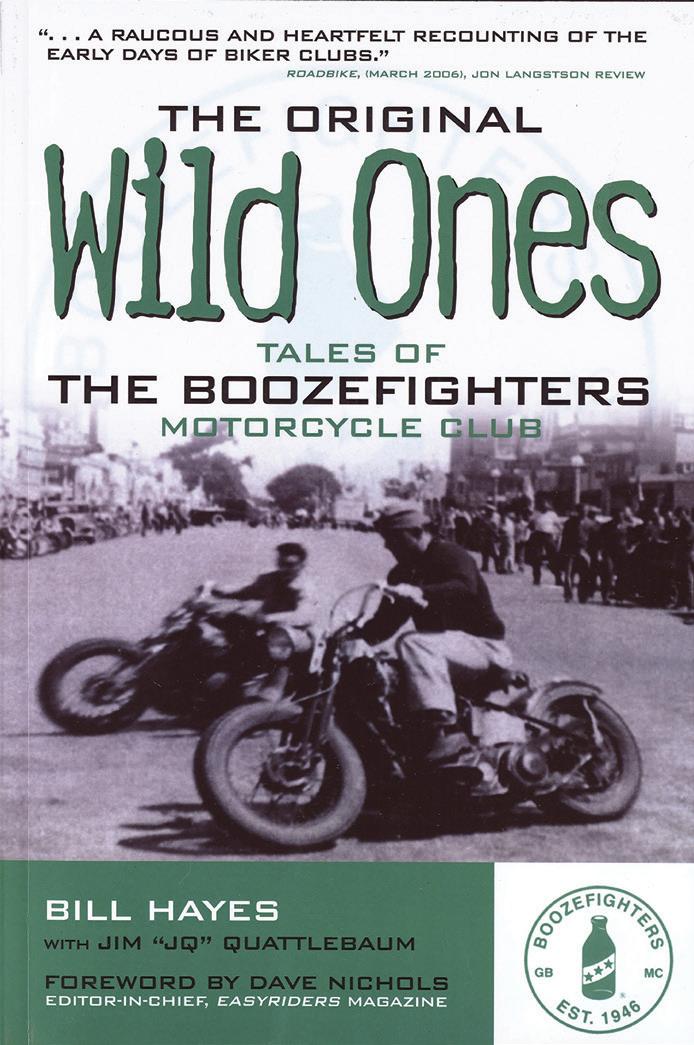

the history of one of the oldest motorcycle clubs in America

Get an inside look at the real beginning of outlaw biker culture with this “raucous and heartfelt recounting of the early days of biker clubs” (Roadbike). The story starts one weekend in 1947 at a motorcycle race in Hollister, California. A few members of one club, the no-holds-barred ‘Boozefighters,’ got a little juiced up and took their racing to the street. Word of the fracas spread, and soon enough, Life magazine was on hand to tell the world with sensational (albeit posed) pictures of the outlaws. And then the ‘Hollister riot’ made its way into the movies, immortalized in Marlon Brando’s “The Wild One.”

What was the reality behind the myth? Through interviews with the surviving members of the Boozefighters, current member Bill Hayes and club historian Jim “JQ” Quattlebaum take readers right into the fray for a firsthand account of what happened in Hollister and the formation of the Boozefighters, where the outlaw biker culture truly began.

Call 800-880-7567, or visit Store.MotorcycleClassics.com to order!

Item #11839

$24.99

Members: $22.99

Mention promo code MMCPANZ2.

FC TheWildOne 1/2Horizontal.indd 1 7/11/23 2:04 PM

See what we have to o er at heidenautires.com

Quality tires, made in Germany

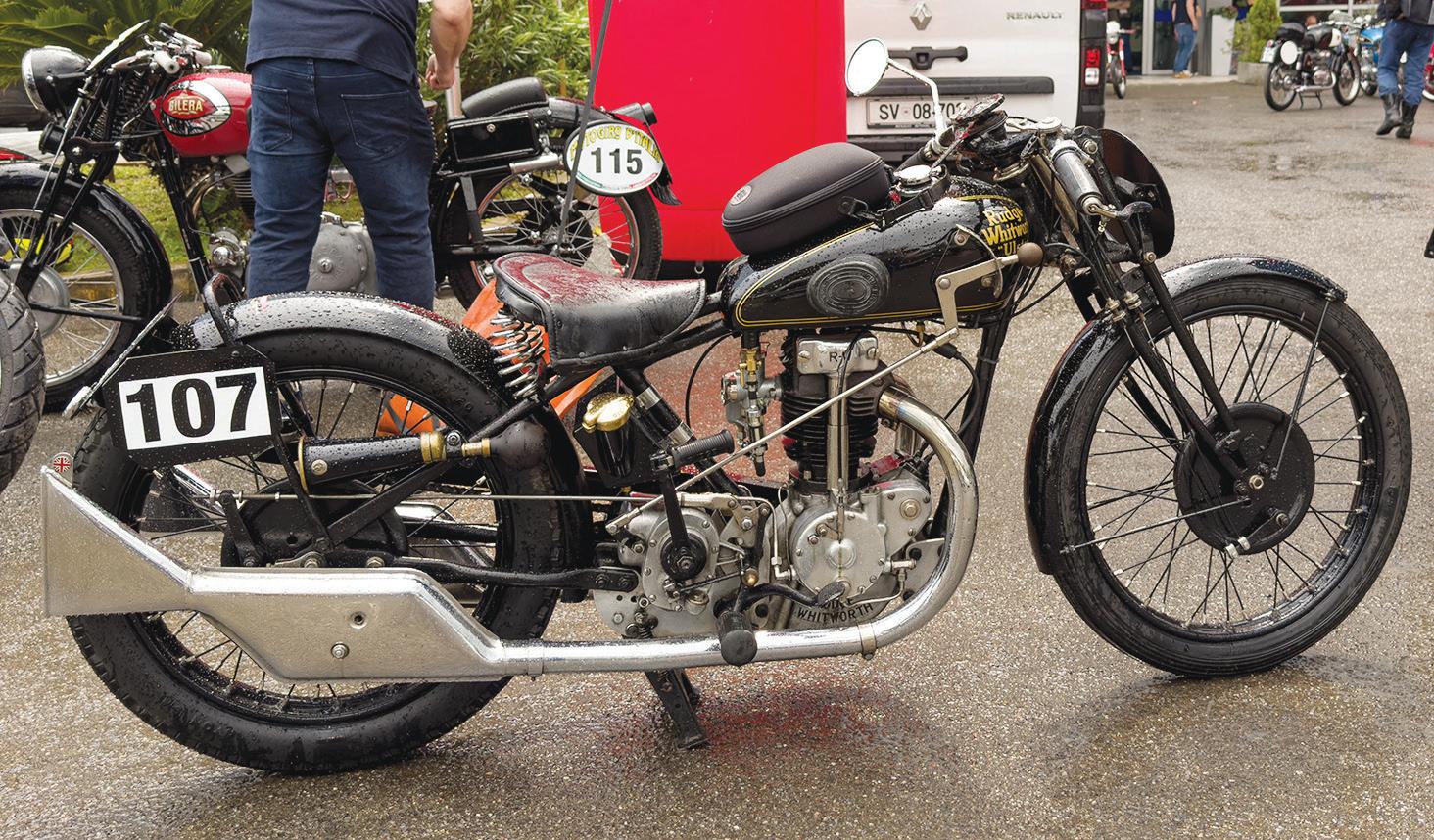

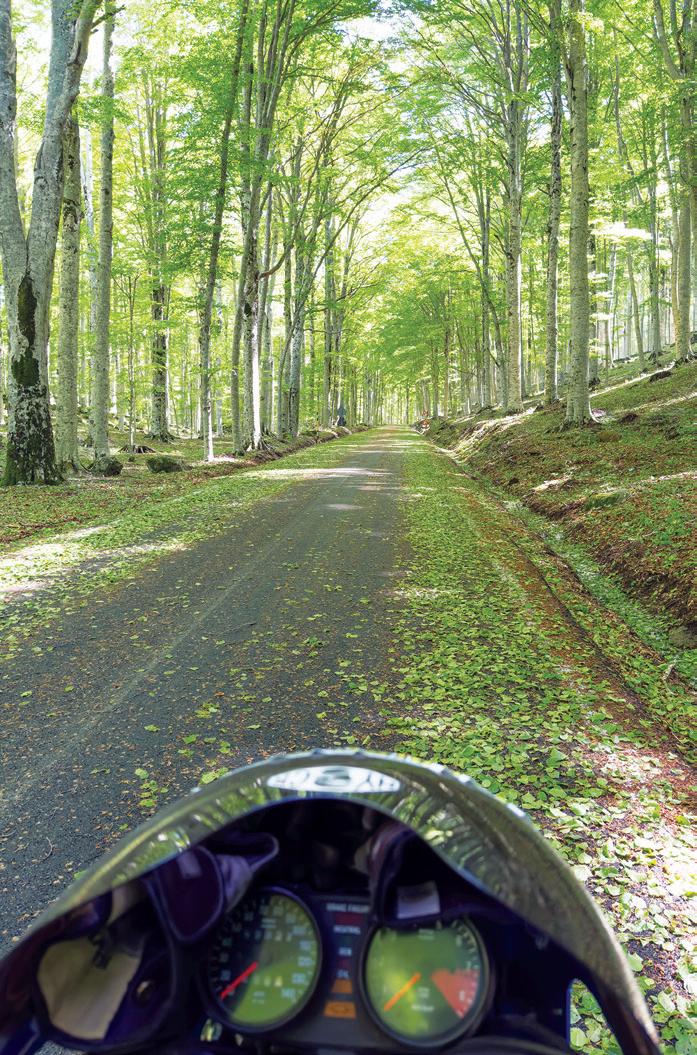

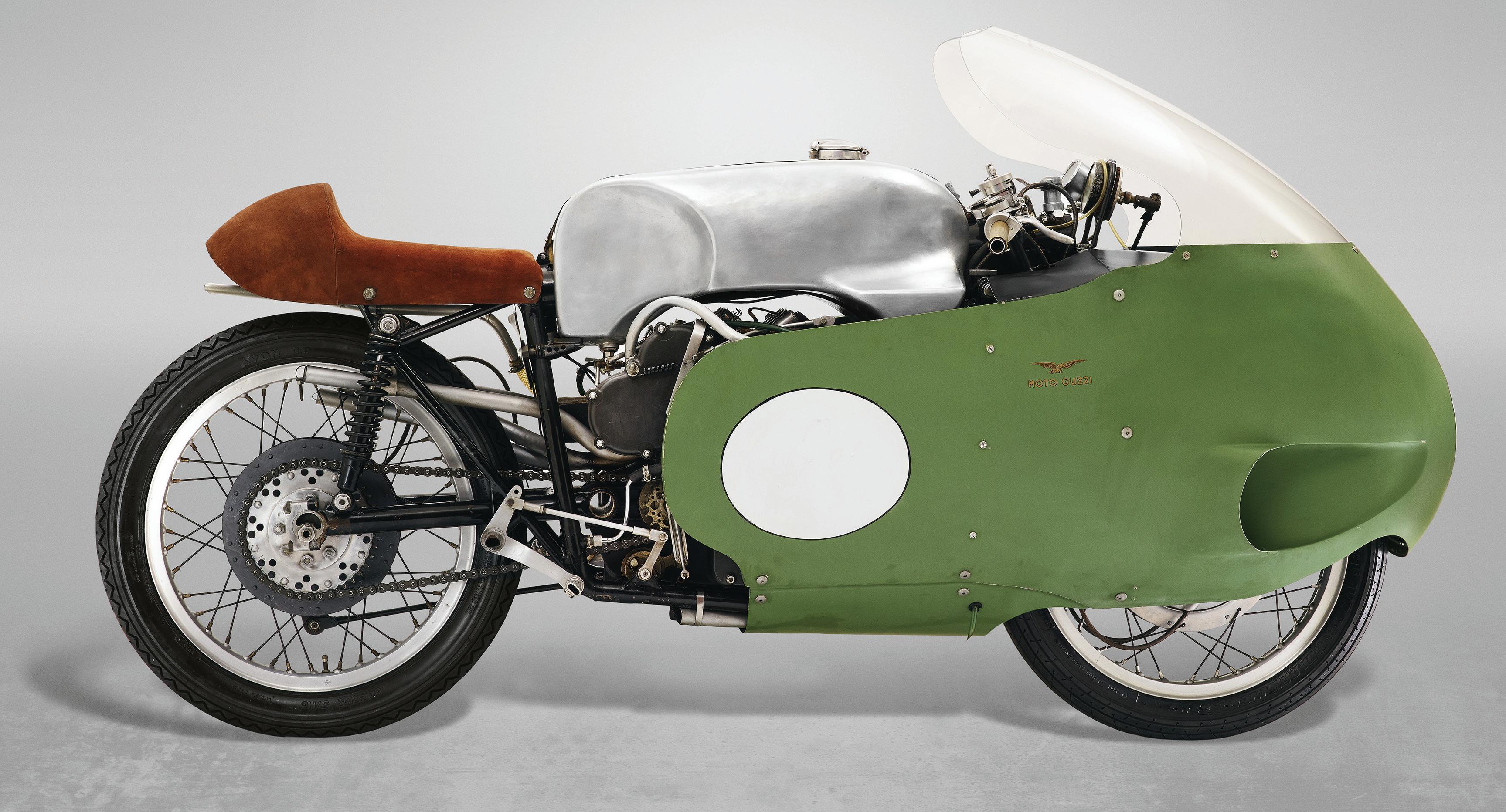

THE 2023 MOTOGIRO D’ITALIA

Roaming Tuscan Roads on Classic Motorcycles

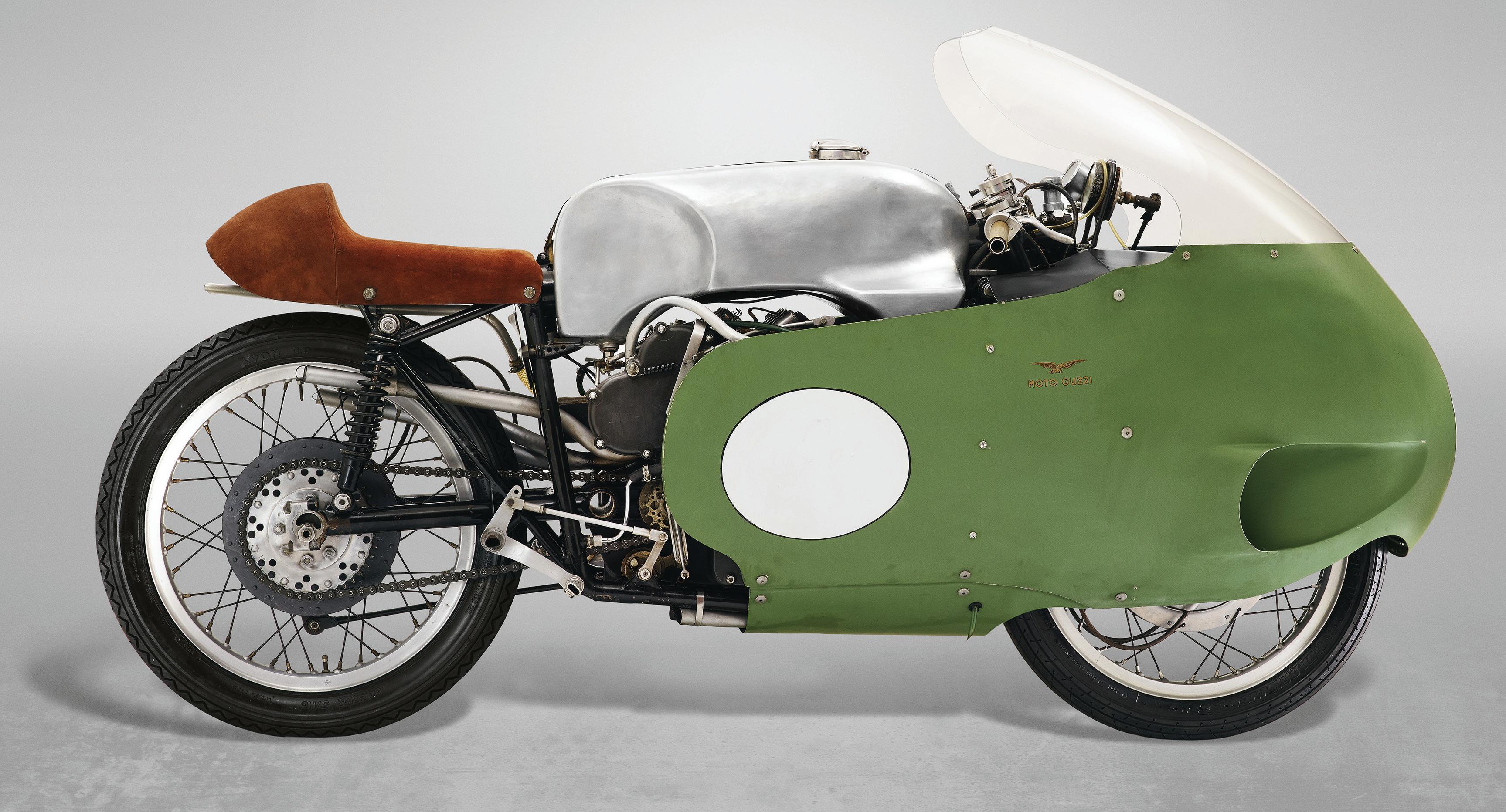

The Motogiro was a prestigious event and competition was fierce with all the major Italian manufacturers competing in classes ranging from 75cc-175cc. In the final 1957 edition, the various classes were won by riders on bikes made by Benelli, Ducati, Laverda and MV Agusta.

Friends who have experienced it raved about the incredible time they had. Riding around Italy for a week on classic motorcycles sounded like pure bliss. However, obstacles like the logistics of traveling from the U.S. and finding a suitable ride kept my dream on the back burner.

But then, towards the end of summer 2022, my good friend Mateo (despite not being Italian) made me an offer I couldn’t refuse. He had purchased a charming home in Montefegatesi, a small ancient town near Pisa, and generously offered me a place to stay and use of a classic bike if I registered for the Motogiro and flew to Italy. It was as if the stars had finally aligned, and I started planning my long-awaited adventure.

Origins of the Motogiro d’Italia

The original Motogiro d’Italia road race ran from 1914 until 1957. The peak years were 1953-1957 when the event started and finished in Bologna with races averaging 3,000km over six days. The Motogiro was the first big event on the annual calendar for Italian road racing. It was held in March/April followed by the Mille Miglia in May and, finally, the Milan-Taranto race in July.

As a result of a tragic accident in that year’s Mille Miglia when a Ferrari went off the road killing the driver, navigator and ten spectators, the Italian government outlawed all racing on public roads and the Motogiro went dormant for over thirty years.

Resurrection of the (Modern) Motogiro d’Italia

In 1989, a local motorcycling organization, Moto Club Terni, relaunched the Motogiro d’Italia with sanctioning from the Fédération Internationale de Motocyclisme (FIM) and the Federazione Motociclistica Italiana (IMF).

It was initially run as a historical re-enactment with entries restricted to bikes made no later than 1957 and no larger than 175cc, but the current version of the event has categories to accommodate all bikes. There’s a wide variety of bike classifications allowing for entry of pretty much any motorcycle. This year’s groups were: “Heritage” bikes made from 1914-1949, “Historical Re-enactment” bikes of 75, 100, 125 and 175cc, “Vintage” bikes made from 1967-1969, “Classic” bikes made from 1970-1980, “Motogiro” bikes made from 1980, Scooter, and Tourist (any year, any make — not timed).

30 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS September/October 2023

TThe Motogiro d’Italia, a legendary event, has been a decades-long dream for me.

Story and photos by Corey Levenson

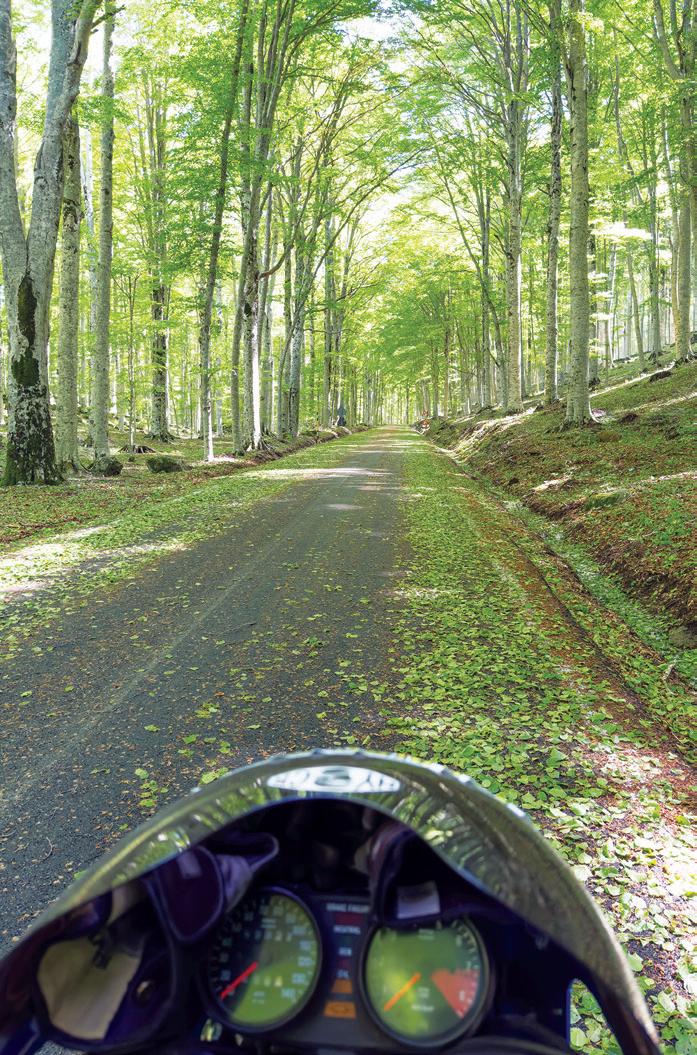

Just another day tooling around Tuscany on a classic BMW.

COPYRIGHT 2023DOMENICO VALLORINI

Is it a Race or a Ride?

Although the original Motogiro was a full-on race, the modern version can be ridden in one of two ways: as a timed competitor, where punctuality is more important than speed, or as a tourist in which case there’s no need to watch the clock — you just enjoy the ride.

If ridden as a competition, it’s a regularity rally with a few low-speed agility tests thrown in. Each rider is issued a timecard every morning with their race number on it. The goal is to start the ride at your designated time, arrive at all the control checkpoints at specific times, and finish at your designated time. At the end of the day, you hand in your card with all the time stamps. The standings are tallied each night and the leaders in each category are announced. Typically, the Italian riders go home with all the awards. They know the roads and they are damn fine riders. Their advice to us newbies was: “No brake!” And it’s true: I followed a few of them through the twisties and rarely saw a brake light come on.

The Course

The route changes each year. Last year it was in southern Italy, this year was Tuscany, and next year’s route will be announced this Fall — it’s rumored that it will be at the end of May 2024, and might be in the Northwest. For updates, keep an eye on the event’s website: motogiroitalia.it

Navigating the route depended on spotting what seemed like a thousand red arrows on yellow cards zip tied to posts along the roadside and at the entrance to each of the dozens of roundabouts we went through. If I arrived at

32 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS September/October 2023

A 1955 Moto Guzzi Airone 250 waiting to be inspected before the ride.

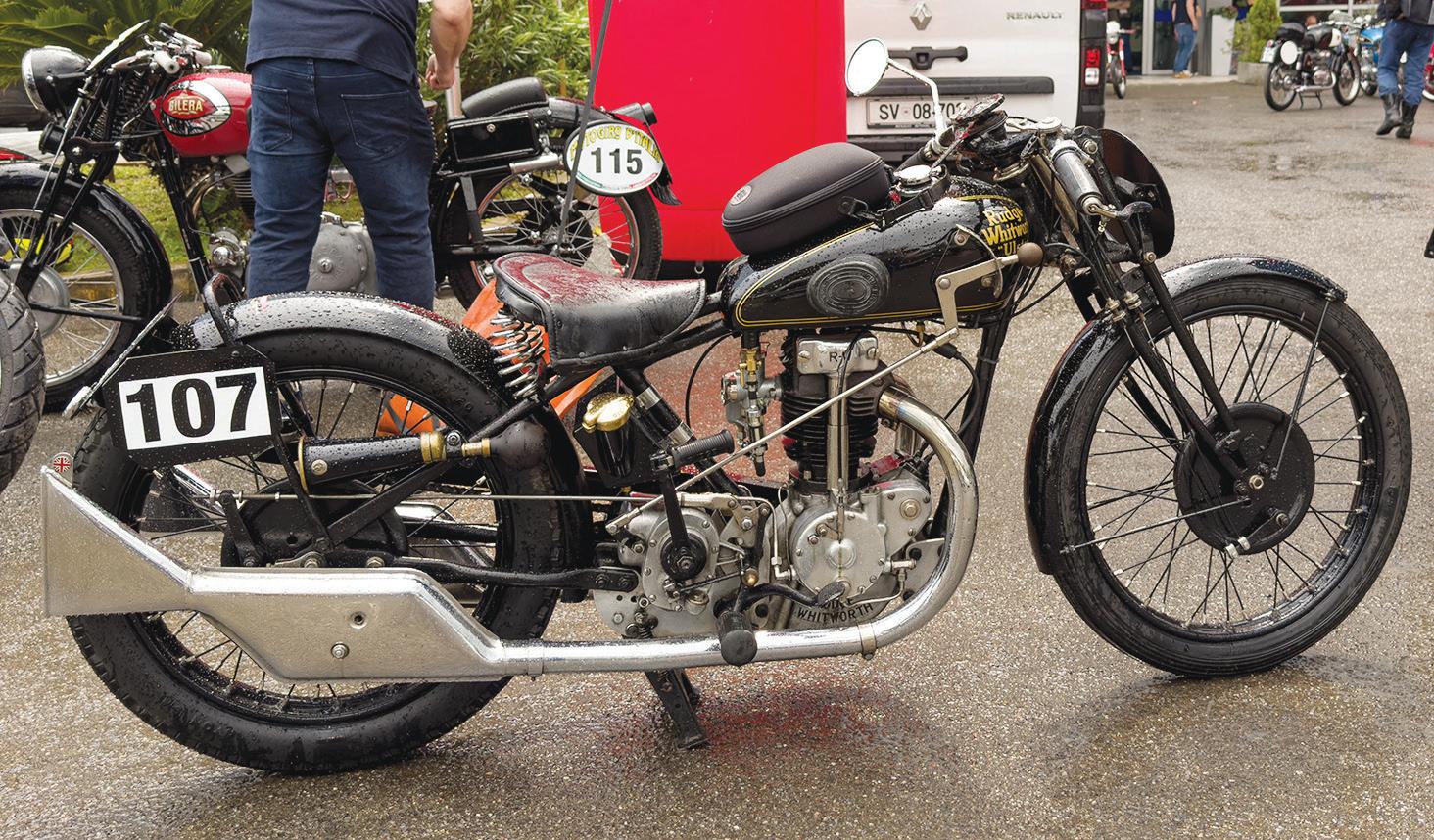

1929 Rudge Ulster with hand shift and Brooklands silencer — a rare sight!

Getting ready to start the ride in the shadow of the cathedral.

a roundabout and there was no arrow, it meant I’d missed a turn and had to backtrack.

We had an escort of a half dozen carabinieris on Ducatis and Yamahas. They were awesomely skillful riders and, between their presence and our numbered race bibs, we were somewhat immune to many of the traffic laws. Obviously, no one did anything downright dangerous, but things that are normally illegal like lane-splitting, passing in no-passing zones and treating the KPH speed limits as MPH limits were shrugged off. Mechanics swept the course, so it was important to stay on the planned route or they wouldn’t find you if you broke down.

This year’s course went through almost 1,000 miles of Tuscany. We started and finished in Pisa and spent six days riding, spending nights in Arezzo, Chiancano Terme and San Vincenzo along the way.

Sunday, May 21, was the first official day of the event and was spent scrutineering the bikes, applying numbers, picking

up credentials/schwag and attending a riders meeting. The riding started at 9 a.m. on May 22 with the first Stage going from Pisa to Arezzo (145 miles). Tuesday was a 143-mile loop starting and finishing in Arezzo. Stage Three took us from Arezzo to Chianciano Terme (139 miles) with a loop starting and finishing in Chianciano on Stage Four (170 miles).

On the Fifth Stage we rode to San Vincenzo on the coast (166 miles) and stayed at a hotel on the beach that night. You could see the islands of Elba and Corsica from the shore. The final day of riding, on Saturday, May 27, we rode back to Pisa the long way via Mateo’s tiny town of Montefegatesi (184 miles).

The finish, at the foot of the Leaning Tower of Pisa, was accompanied by lots of hugging and congratulations. With any experience where the levels of risk and reward are elevated, there’s a feeling when it ends of both sadness that it’s over and fulfillment that the venture was successfully completed. The closing event was a nice final gala dinner at the hotel that night.

www.MotorcycleClassics.com 33

Left: The dachshund riding pillion on this 1931 Gilera 150 was extremely brave! Right: A 1955 Mondial Turismo Veloce having its points checked.

The rest stop at the Piaggio museum featured scooters as well as rare Gileras and Moto Guzzis.

A Rolling Museum

There was an incredible mix of mostly classic and vintage machines on the ride. Everything from Rudges, Nortons and Vincents to Motobis, Benellis, MV Agustas, Moto Guzzis, Ducatis and Mondials. It was pretty cool to be riding in the middle of bunch of such loud, smokey and beautiful machines. In addition to the historic and classic machines, there were a handful of modern Ducatis, Husqvarnas, Benellis and others. There were several two-up teams in the tourist as well as timed classes. In addition, a modern Norton 961 was pulling a sidecar and passenger.

You can ship your own bike from the U.S. or, if you live in Europe, you can transport (or ride) your bike from wherever you live. One chap from the U.K. rode his ‘69 Triumph Bonneville all the way from England, did the rally, and then rode back home. Another popular option is to rent something. An outfit called Ride 70s (ride70s.com) supplied a few machines to people on the ride. You can also rent

34 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS September/October 2023

Left: A patriotic tricolor scooter rest stop display put on by one of the local clubs. Right: Look closely and you can see one of the thousands of arrows we followed all week.

Left: One of the time controls at a rest stop — don’t be early and don’t be late! Right: A typical rest stop spread complete with local bread, cheese, pasta and wine.

COPYRIGHT

-

Left: Narrow, steep cobblestone streets were common in the old towns. Right: A lovely mountain road in the Tuscan hills.

2023

DOMENICO VALLORINI

something new like a Vespa or a modern Ducati.

The Riders

The Motogiro draws an international crowd. About a third of riders were Italian, a quarter were from the U.K., 12% were from Germany and 10% from the U.S. The rest are Dutch, Spanish, Swedish, Norwegian, Australian, Polish, Belgian and Swiss.

Many of the riders had been doing the Motogiro for years, including one Italian fellow who hadn’t missed one in 30 years. There were also many folks for whom, like me, this was their first Motogiro. Out of the 190 or so riders, I’d estimate that a dozen were women. As in the classic motorcycling world in general, I’d guess the average rider was a 65-year-old guy.

My Motogiro

Mateo is a member of an eclectic group known as the “Lucky Bastards.” They’re a bunch of about a dozen rabid motorcycle enthusiasts spread around the world (mostly the U.S.) who get together for social events like the Motogiro. Most of them were present at this year’s Motogiro. I spent a lot of time hanging out with them and learning the ropes. Most of them own bikes which they keep in Italy for such occasions. Mateo arranged for me to ride a low-mileage blue 1974 BMW R90/6 that belonged to a fellow Lucky Bastard who couldn’t participate this year.

My relationship with the Beemer was like an arranged marriage. She and I had never seen each other before the first day of riding but, over the course of a few days, Brunhilda let me know how she liked me to shift gears, and I learned what to expect in response to throttle inputs and squeezing the brakes. We got along fine. I made sure her oil level stayed topped up and she got me through some sketchy situations and provided a confidenceinspiring ride.

The Motogiro Demands Respect

This is not a ride for novices. The Motogiro website describes it as “most beautiful and treacherous.” Believe it. Very little of

www.MotorcycleClassics.com 35

Left: One of the group dinners. The food was outstanding! Right: A couple of the British riders at the stage finish in San Vincenzo on the coast.

Tony’s been a Lambretta man since the days of Mods and Rockers.

Left: Checking the class standings each evening. Right: Cheering school kids greeted us as we rode through their town. It really made you feel like a hero!

Tuscany is flat — most of the time we were either ascending or descending the sides of steep hills, negotiating thousands of blind hairpins connected by short sections of straight-ish road with limited line of sight. There was a lot of shifting, braking and accelerating on roads with very few center lines and no guard rails.

The road surfaces could be shady, sunny, wet or dry and varied from billiard table-smooth to broken and potholed to unpaved.

As lovely and distracting as the scenery was, the roads demanded near total focus. We encountered sun, rain and even a little hail during the week.

The Motogiro is an endurance event that tests both riders and motorcycles. Of the 200 riders who registered this year, 189 showed up for the event and 144 finished. Mechanical problems were not uncommon and, unfortunately, several folks left the ride in ambulances.

Thinking About Doing It?

The registration cost depends on the exchange rate (Dollars to Euros) and whether you ride as a tourist or in a timed class but figure $1,600-$1,800. A single room will cost an extra $250 or so. The fee includes hotels every night, breakfasts, a group dinner each evening, luggage transfers and a nice, embroidered polo shirt, hat and a pair of Domino grips (they’re one of the sponsors).

Pisa is seven time zones from where I live in Texas. I had planned to get there two days before the event to get over my jet lag but, thanks to a threatened strike by Italian airport workers, my flight was delayed two days and I got there just in time to start riding. If you go, leave yourself enough time to get used to the new time zone.

The right bike will enhance your riding experience. With an average speed of about 30 miles per hour, a nimble bike with good braking, acceleration, and handling is ideal. Many riders opted for singles up to 500cc displacement, including beautiful Italian brands like Moto Guzzi, Mondial, Parilla, Benelli, MV Agusta, Motobi and Ducati. If you prefer a heavier bike, ensure it has decent suspension and reliable brakes. Of course, next year’s route may be less twisty, and a bigger bike might be fine.

Riding started each day at 9 a.m. and was usually over by 4 p.m. Dinner typically started at 9 p.m. and ended at 10:30. This is later than most Americans like to eat, especially since we were up early to get breakfast, check out of the hotel, gear up and get riding. As they say: “When in Rome …”

If you ride in the tourist class, you can dawdle a bit and spend some time exploring the towns along the way. There were

36 MOTORCYCLE CLASSICS September/October 2023

Left: Perhaps the perfect Motogiro bike — A 1949 Moto Guzzi Airone Sport 250 horizontal single. Right: Dining al fresco in the middle of the Motogiro. What could be more Italian?

We saw a lot scenes like this. Narrow roads, no traffic and stunning vistas.

Entering Bagni di Lucca, popular for centuries thanks to its hot springs.

also two stages that started and finished at the same hotel so those were good days to take some time off the bike and do some shopping and sightseeing if you wanted a break from riding.

Carry some cash for gas. Attendants take a lunch break between about noon and three. None of my credit cards worked in the automated self-serve gas stations. They did take Euro notes, however, so make sure you have some of those on hand.

Enjoyment of the event depends on having the right attitude. Things are a bit loosey goosey and occasionally go wonky. You just have to roll with the punches and tell yourself it will be lovely, whatever happens. Because it will.

Reasons To Go

The camaraderie and opportunity to make new friends is one of the best reasons to participate in such events. There were plenty of English-speaking folks to chat with and, between the Lucky Bastards, other Americans and the Brits, I made at least a dozen new friends.

The scenery during the ride was absolutely stunning. From olive groves and vineyards to waterfalls, fields of vibrant wildflowers and jasmine, and charming medieval villages, my senses were treated to a feast. The food offerings such as coffee, pastries, cheeses, cold cuts, pasta, tiramisu, pizza, and gelatos were excellent and surprisingly affordable.

The riding experience itself was incredible. Regardless of your skill level, you’ll probably be a better rider by the end of the ride compared to when you started. The hundreds of hairpin turns and diverse road conditions pushed me to improve my bike handling skills.

Most of the roads were small with very little traffic. The variety of landscapes was amazing. One day we were riding through crisp mountain air up to an Italian ski resort and the next day we were riding along the coast with the sun glinting off the water. There were forests of chestnut trees and lush rolling hills topped by ancient stone settlements. We enjoyed rest stops in piazzas shaded by centuries-old cathedrals while eating local salamis, breads and cheese and sampling the local wine while the carabinieri stood nearby chatting with each other.

The Spirit of the Motogiro d’Italia

Massimo Mansueti is President of Moto Club Terni and Organizer of the Motogiro. When I asked him what made the Motogiro such a special event, his reply was: “The emotion we feel and share with others is the reason we’ve been organizing

this event since 1989. Getting to know new enthusiasts and forging new friendships is our reward for the huge organizational effort we make. The tearful embraces at the finish line give us the strength to continue.”

He also felt it’s about carrying on with tradition: “The knowledge that we’re organizing a historical re-enactment of the oldest and best-known of Italian motorbike races, which was the driving force behind the Italian motorbike industry for so many years, and which is now known all over the world, leads us every year to always try to improve.”

Massimo stressed the fundamental attraction of travel and adventure: “Even in the digital age, the connection between people and the land endures. New destinations evoke powerful emotions, sensations and a yearning for exploration. Travelers cherish the memories of their journeys forever. The Motogiro d’Italia offers enthusiasts a chance to embark on timeless adventures, riding their cherished motorcycles through historic roads and captivating places.”

I thoroughly enjoyed the Motogiro d’Italia and my ride in this year’s event motivated me to try to repeat the experience. When I got home and my friends asked me what it was like, I told them If heaven exists and I manage to sneak in, I hope to spend eternity rolling through Tuscany on a vintage bike. Who needs wings when you have two wheels and endless Italian landscapes? MC

Discover the Complete Italian Heritage

A-Z of Italian Motorcycle Manufacturers is the most complete directory of Italian motorcycles available today. In addition to covering the most famous Italian factories, this is a definitive guide to the marques that have had little or no coverage. Some might be familiar, while others are remembered for their racing achievements, and many will never have been heard of by most readers. Topics covered include the history of the once great factories; marques that build motorcycles exclusively for racing; details of the most important motorcycles each manufacturer built, and each marque’s greatest achievement. This title is available at store.MotorcycleClassics.com or by calling 800-880-7567. Mention promo code: MMCPANZ5. Item #10838.

www.MotorcycleClassics.com 37

Left: Downtown 1,000-year-old Montefegatesi as the Motogiro comes to town. Right: Crossing the finish line in Pisa — feeling a bit sad but very satisfied.

NOT STOCK

The Medaza Wasp

Story and photos by Phillip Tooth

HHand-crafted in Ireland, Don Cronin’s latest creation looks like the sort of bike that Captain America would ride, not a Royal Danish postman.

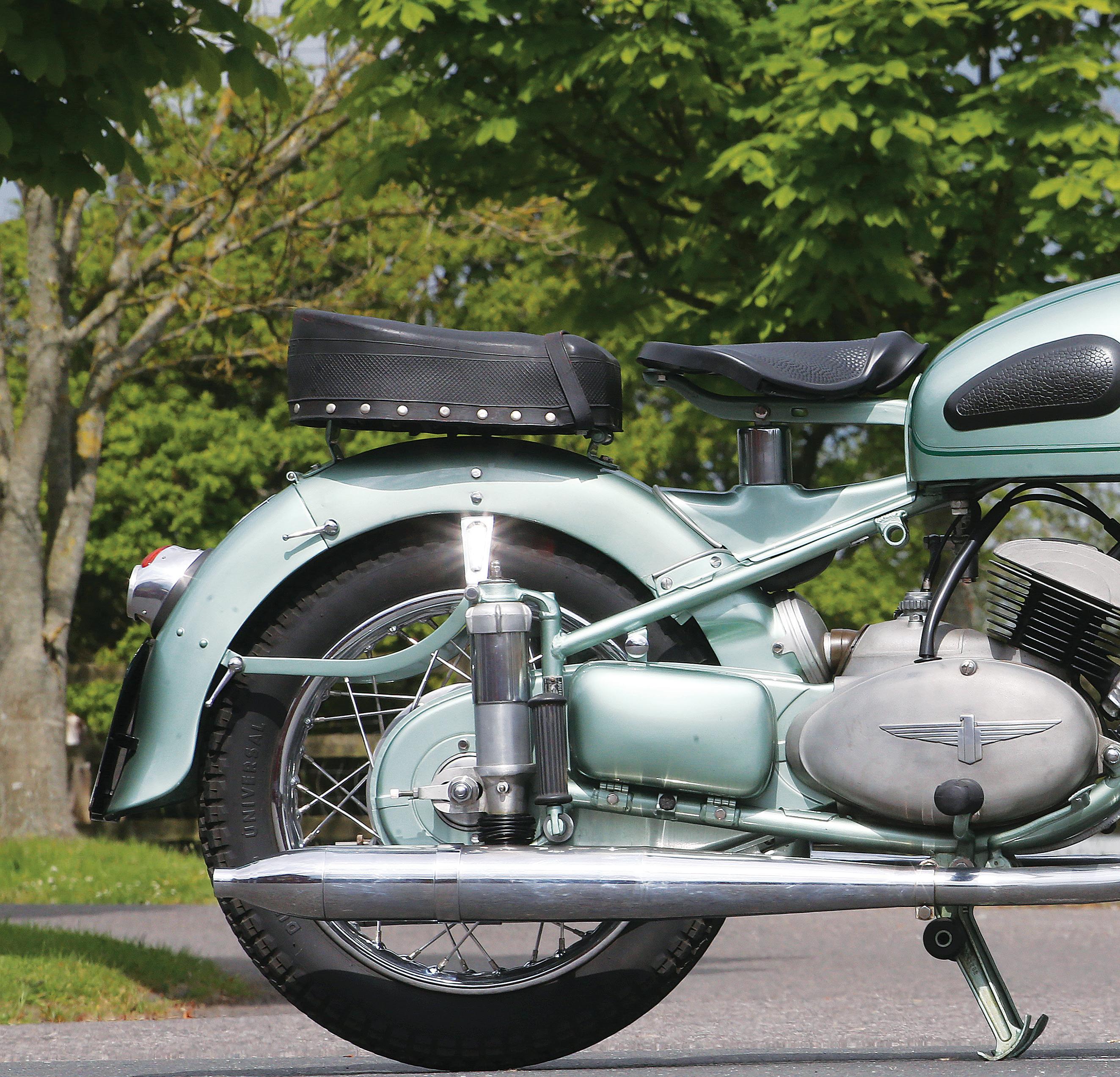

When it comes to choosing an engine for his Medaza motorcycles, Don Cronin has form. Forget about a big Harley mill from The Motor Company or the latest big-bore Triumph twins and triples. He’s used a 500 single with a “bacon slicer” external flywheel that once powered a Guzzi Nuovo Falcone, a V-twin liberated from a Morini Camel enduro, and even a utilitarian 2-stroke lifted from an MZ 300ETZ. So when he wanted an inline four for his latest project, you know he was going to come up with some-

thing different. And in a world of high-revving, huge horsepower fours, there’s nothing quite like a Nimbus.

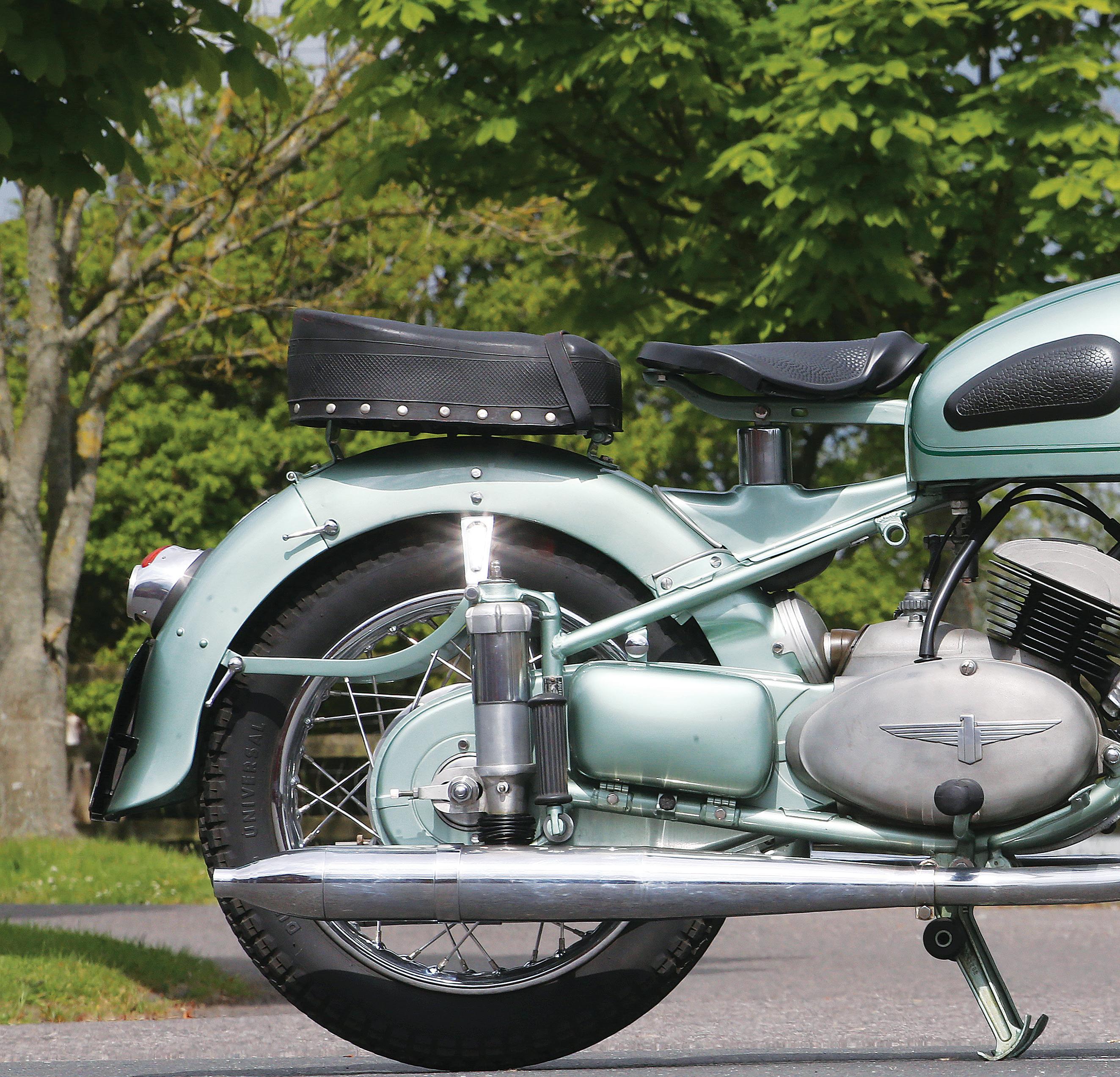

The engine

Vacuum cleaner manufacturer Nilfisk branched out into making motorcycles way back in 1919, but the Nimbus we are interested in was launched in 1934. The unit construction 750cc engine featured an overhead camshaft. Just like the original MG sports car, the vertical camshaft drive to the bevel gears doubled as the armature spindle for the dynamo, which was mounted in front of the cylinder block. The lower half of the crankcase was cast in aluminum and carried a couple of liters of oil, but the upper half of the crankcase and the finned cylinder block were a single piece of cast iron. The detachable one-piece cylinder head with its hemispherical combustion chambers was also cast iron and incorporated the inlet manifold. An aluminum camshaft housing was bolted to the head, with the rockers supported in ball and socket bearings operating on the vintage-style exposed valves.

Hand-formed headlamp cowl is styled after Milwaukee locomotive. Medaza Wasp is so slim it’s almost like sitting on a razor blade.

The one-piece drop-forged crankshaft runs in two large diameter ball bearing journals, with the flywheel incorporating a large single plate clutch fixed at the rear. A 3-speed gearbox was bolted to the clutch housing, with shaft drive to the rear wheel.

The frame

The cradle frame was made from lengths of 40mm x 8mm flat steel, riveted to the steering head and the unsprung rear end. It might not have been sophisticated, but it was cheap, easy to make and practical. Up front was the first modern telescopic fork, patented in 1933. That was two years before BMW introduced their tele fork, but the Germans pioneered oil damping. Hold on to your hair, Nimbus lovers. The standard 1934 model managed with 18 horsepower, but a sports version introduced for 1937 had the compression ratio raised to 5.7:1 and delivered a thrilling 22 horsepower. When the four was revved towards the 4,500rpm limit the straight-through exhaust with its little fishtail really buzzed, which is why Danish enthusiasts nicknamed the Nimbus the Humlebien, or Bumblebee.