MOTHER EARTH NEWS EARTH NEWS P R E M I U M I S S U E LIVING ON LESS Put Extra Food to Good Use Instant Energy Savings • Make Your Own Gas Spring 2019 • $9.99 • Display until June 3, 2019 • Make Your Own Moccasins • Prepare Pasta From Scratch • Homemade Broth and Stocks • Preserve Your Garden’s Bounty • Try Your Hand at Broom-making • Produce Fresh Syrup From Trees INSIDE

The SA Series provides subcompact tractor versatility for every job. Industry-standard 3-point hitch, power takeoff and 2-pump hydraulics connect you to a universe of standard attachments to grade, haul, mow, till, seed and plant. And only YANMAR delivers Performance Link Technology™ ensuring every major component works in harmony, from front axle to nal drive.

The SA Series is part of a full family of tractors from YANMAR. Whether you need a 21 or 24 horsepower SA model, the 35 horsepower Model YT235 or the 47 to 59 horsepower available in the YT3 Series, each tractor from YANMAR is committed to giving back to the earth a little more than we take out of it.

See the lineup and schedule a test drive at YanmarTractor.com.

SA Series 21 & 24 HP • YT2 Series 35 HP platform & cab • YT3 Series 47 & 59 HP platform & cab ©2019 Yanmar America Corporation

Our favorite activity is productivity.

21-horsepower Model SA221 with M60 mid-mount mower

24-horsepower Model SA324/424 with mid-mount mower, YANMAR loader & backhoe

Try

4 Grow $700 of Food in 100 Square Feet

If more of us grew a little food— instead of so much grass—our savings on grocery bills would be astounding.

10 Effortless Homemade Elderberry Syrup

A reader shares how to make medicinal elderberry syrup at home.

12 Freezing Fruits and Vegetables From Your Garden

Follow these straightforward freezing tips to turn your garden harvests into sensational, off-season meals.

16 Buy in Bulk for Big Savings on Better Food

Slash your family’s food costs in half—and support local farmers—by buying meat, produce, and dry goods in bulk.

22 25 Fresh Ways to Put Extra Food to Good Use

Don’t scrap your scraps! Reduce food waste by transforming your leftover morsels into meals.

28 Homemade Broth and Stock

Glean nutrients and flavor from bones and scraps by simmering and seasoning them.

32 Preserve Jams With Less Sugar

These recipes and tips offer a variety of options for preserving low-sugar jams without commercial pectin.

37 Creating Custom Furniture From Salvaged Wood Bootstrap business Baldwin Custom Woodworking transforms diseased trees into handmade heirloom woodworks.

42 Produce Syrup From Birch, Walnut, and Sycamore Trees

Want to branch out from maple? Use this guide to decide which trees to tap and learn to process tree sap into both sweet and savory syrups.

Table of Contents MOTHER EARTH NEWS • Premium Guide to Living on Less 10

your hand at intensive gardening for a highly productive growing system.

COVER: RICK WETHERBEE 102 22 37

45 Foraging and Eating Cattails

This easy-to-identify plant can serve as an everyday staple as well as a superior survival food.

50 How to Dry Food

Dry the harvest to stock up on homegrown snacks and convenience foods for year-round eating.

54 Curing Meat at Home

Bring fancy food to your everyday plate by learning how to make the cold, cooked meats known as charcuterie.

58 3 One-Hour Cheese Recipes

You don’t have to be a professional to enjoy fresh, homemade cheese.

64 8 Easy Projects for Instant Energy Savings

Implement these inexpensive strategies to reduce your carbon footprint and slash your energy bills.

72 Craft a Traditional Hearth Broom

Learn the nearly lost American art of broom-making.

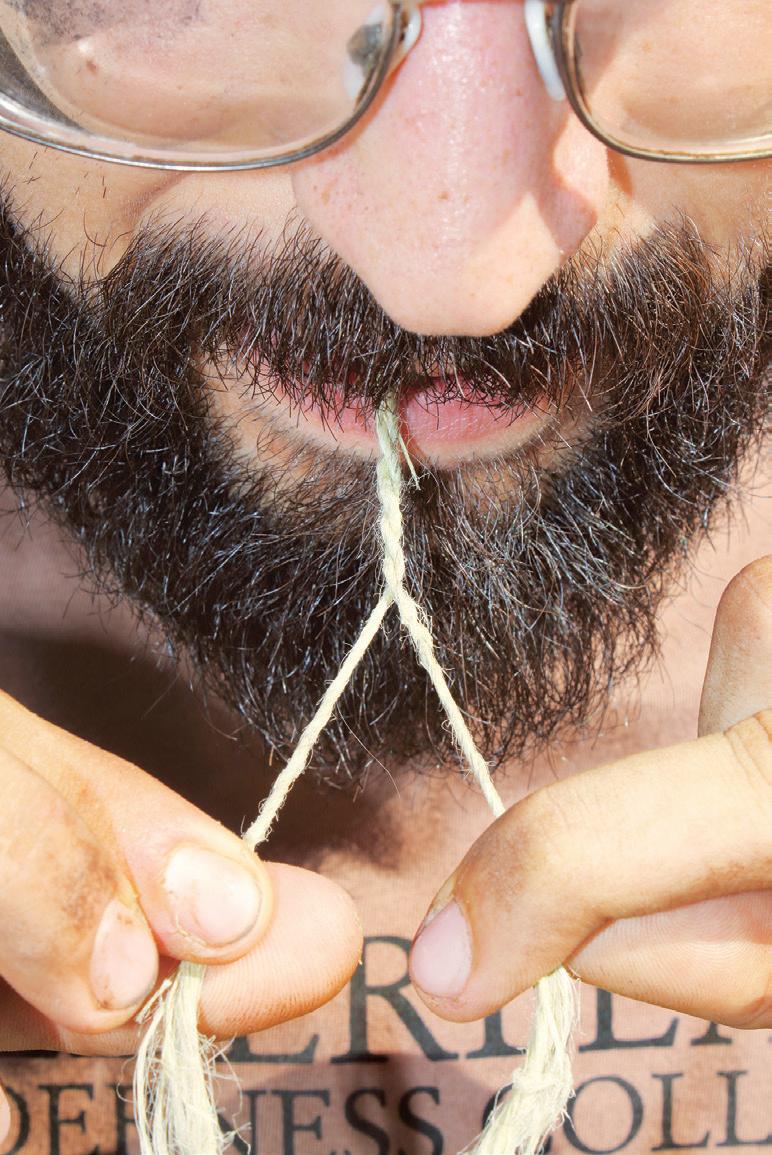

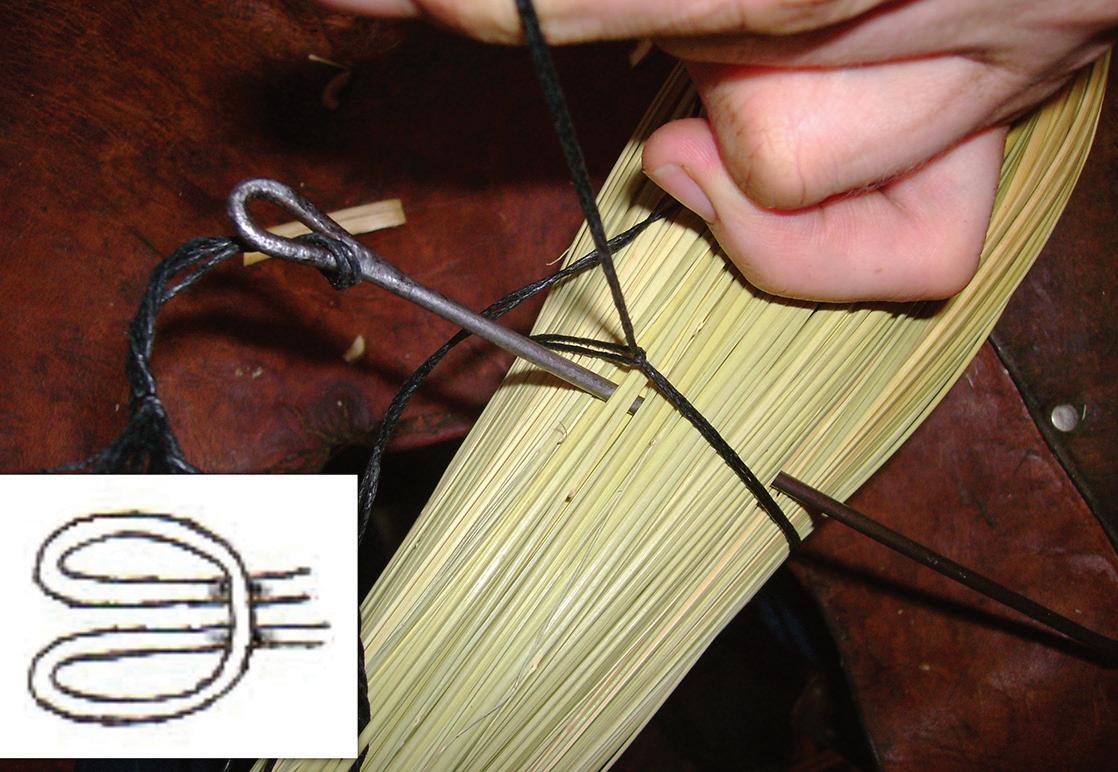

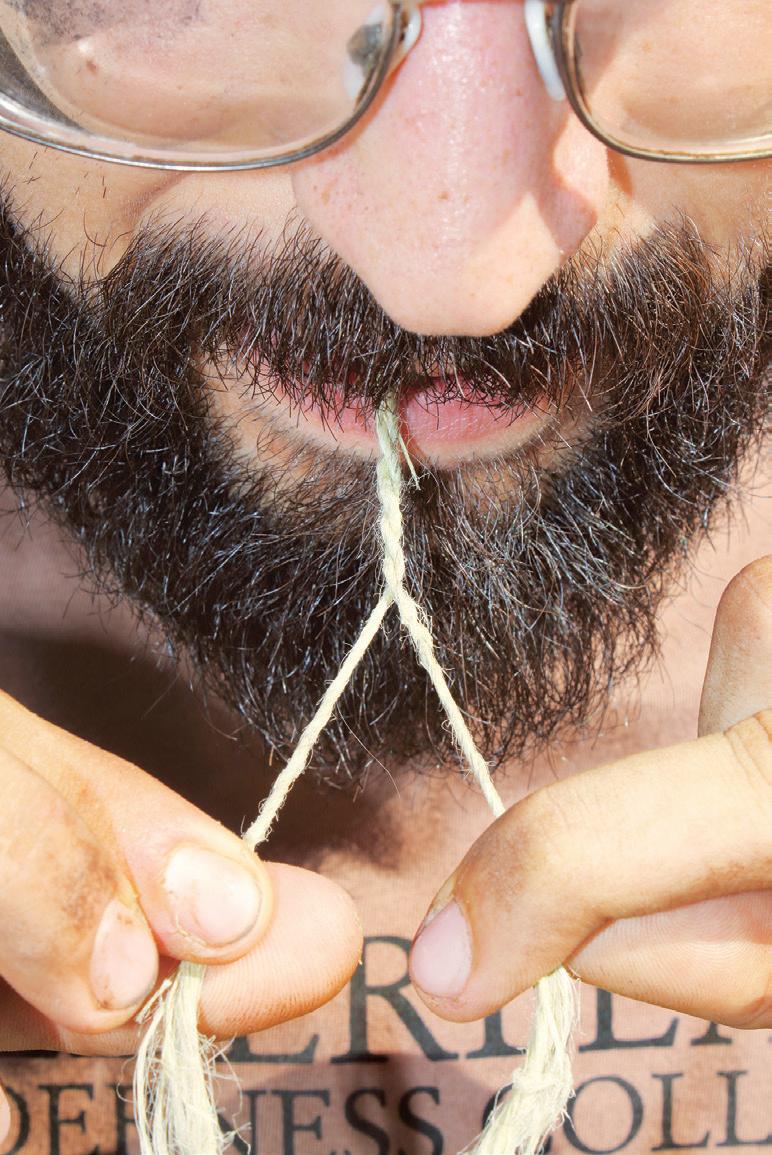

77 Cordage: How to Create Natural Thread

Extract fibers from plants to make your own strong, sustainable string.

80 Make Your Own Gas: Alcohol Fuel Basics

Produce ethanol on a small scale and enjoy the many benefits of this homegrown, renewable fuel.

84 From Field to Flour: Harvest Your Own Wheat

Determine which types of wheat you should grow, plus learn how to cultivate and process this staple grain for use in the kitchen.

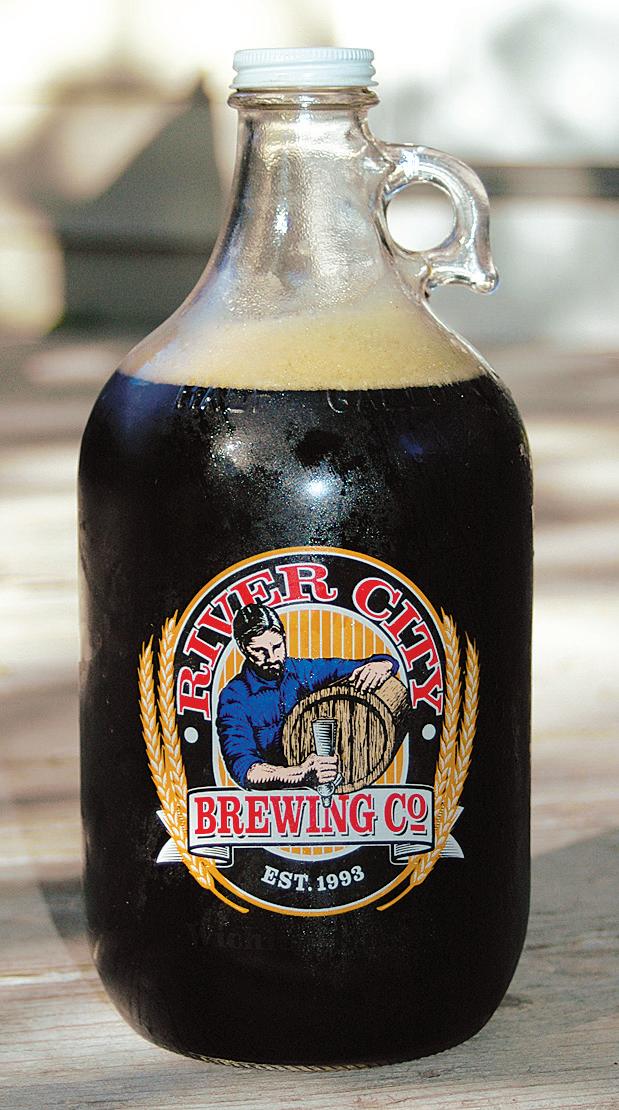

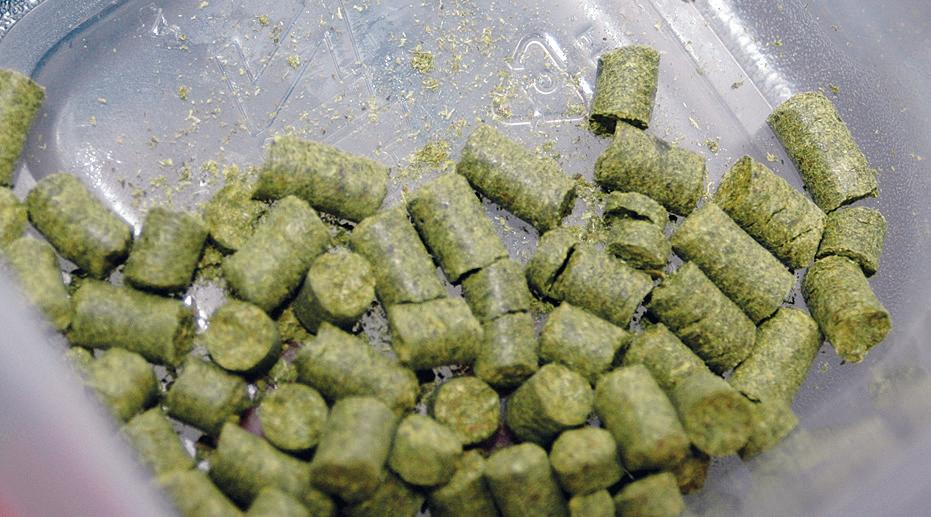

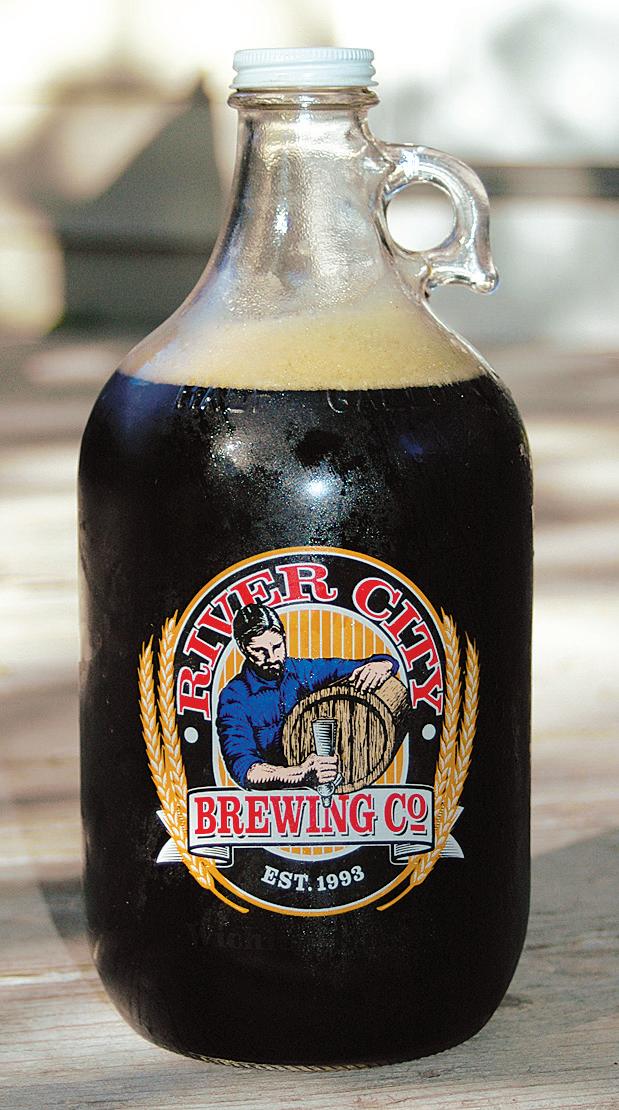

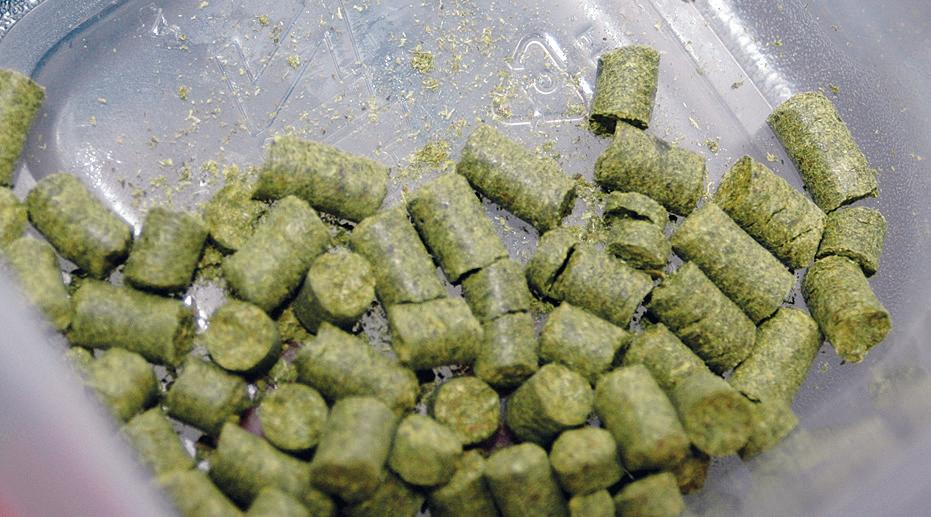

89 Brew Your Own Beer

Homebrewing is kettles of fun, and it’s the perfect way to make your own uniquely flavored, affordable drinks.

94 Fresh Pasta From Scratch: Traditional, WholeGrain, or Gluten-Free

Fresh pastas are so easy to make that you can enjoy homemade noodles any time.

97 5-Minute Homemade Mayo

Craft this creamy condiment with five natural ingredients.

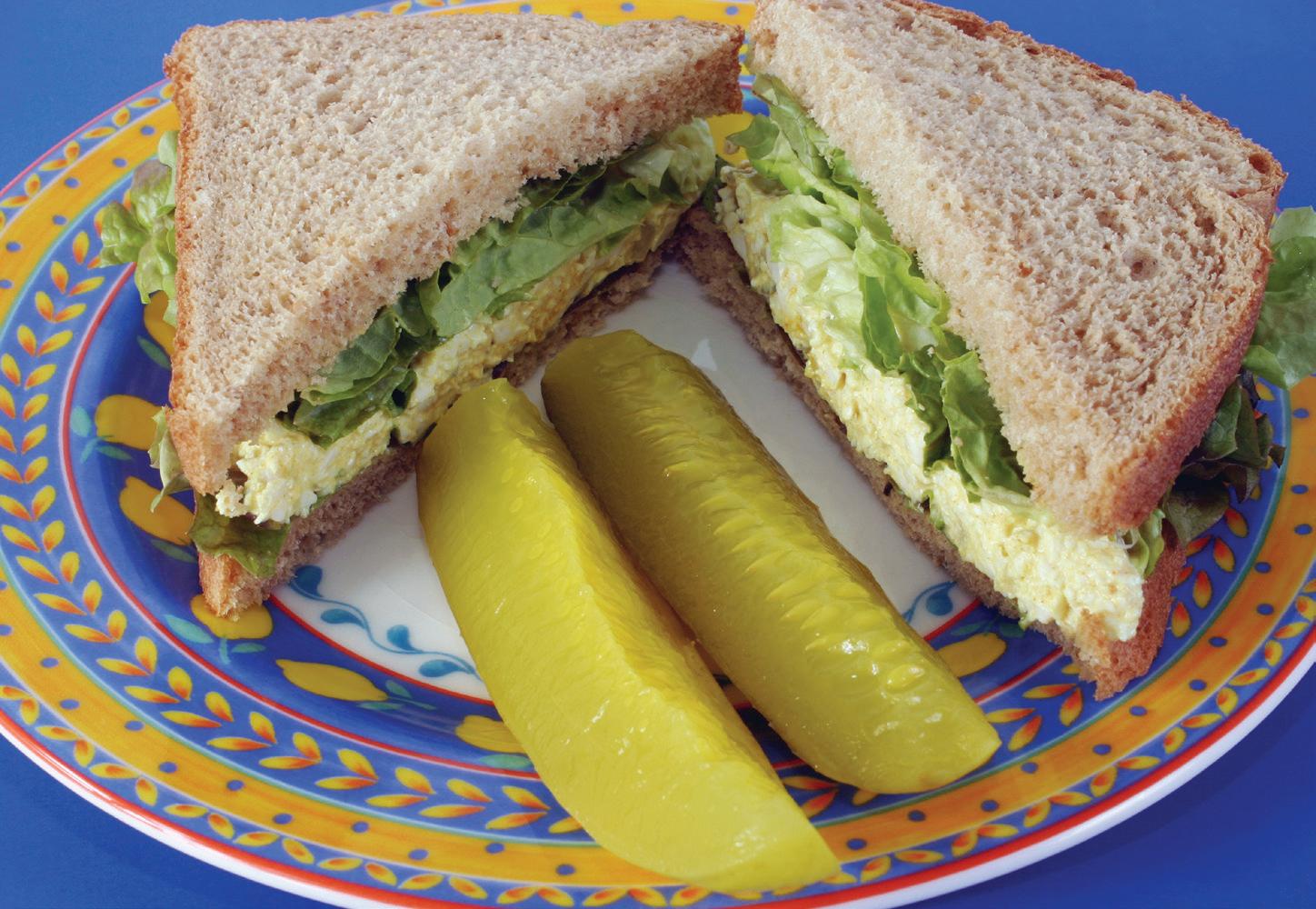

98 Simply Dill-icious Pickles

These three basic methods put perfect pickling within the grasp of every preserver.

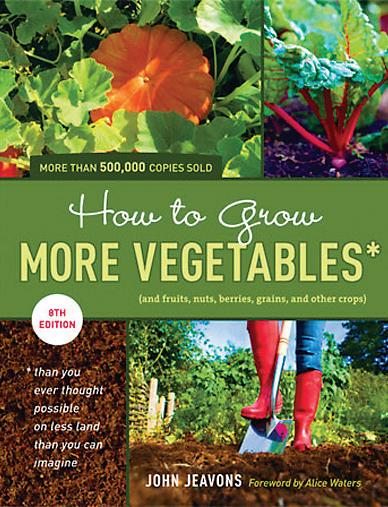

102 Grow More Food in Less Space (With the Least Work!)

Blending the best principles of biointensive and squarefoot gardening will yield a customized, highly productive growing system.

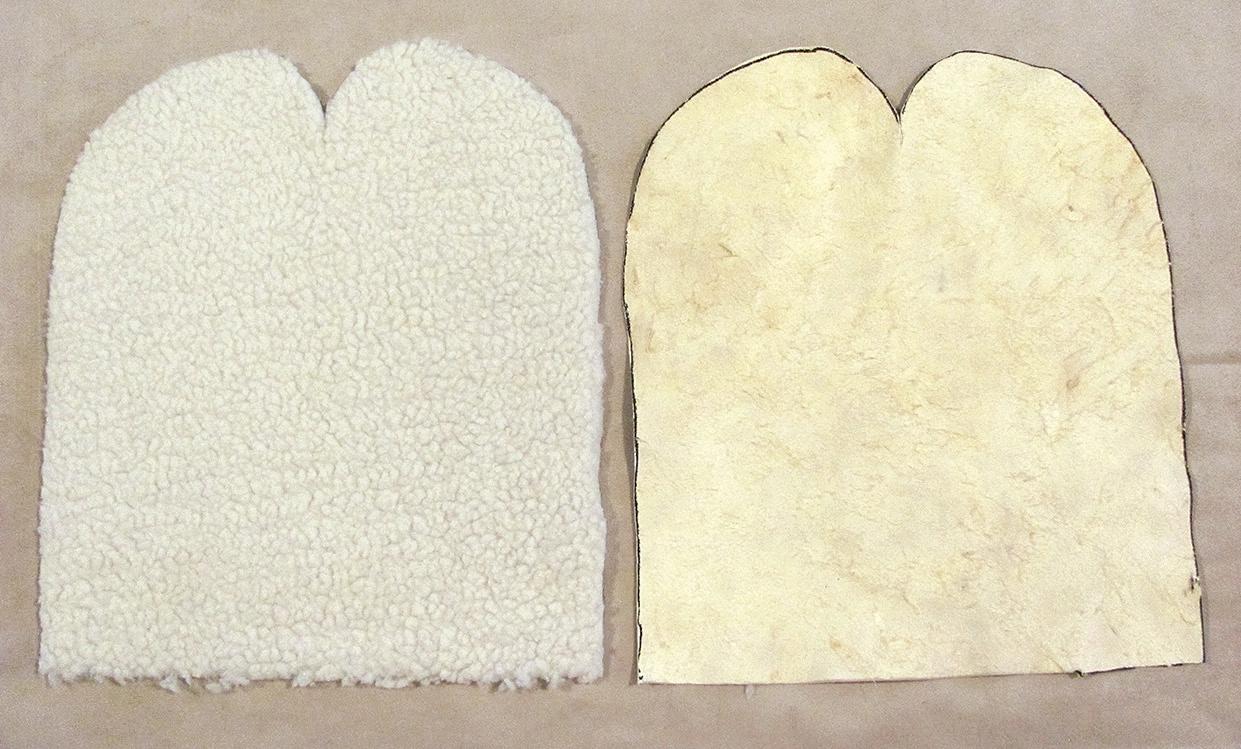

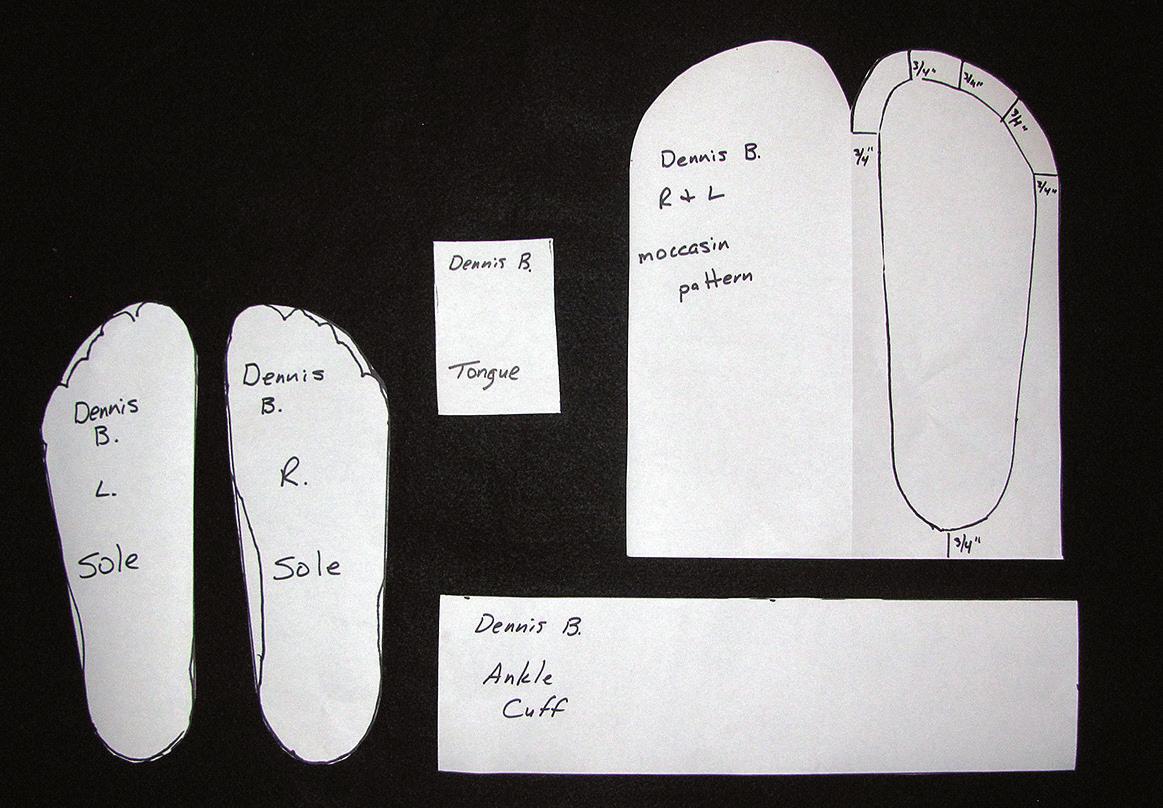

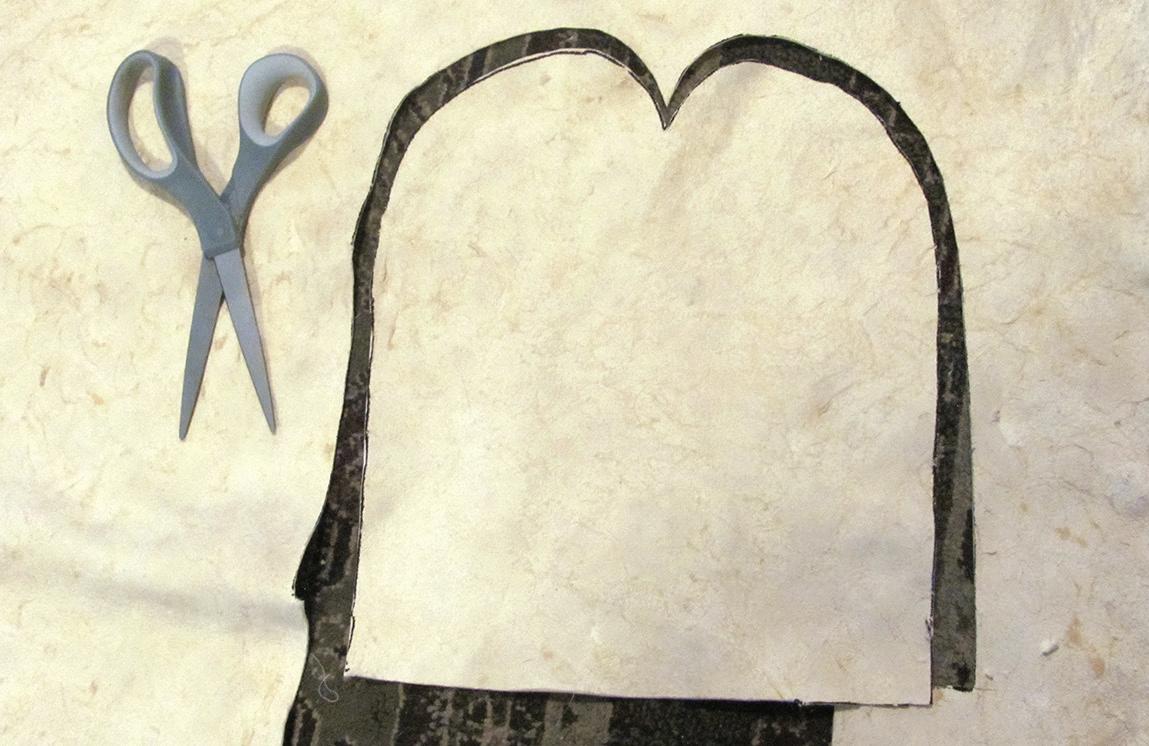

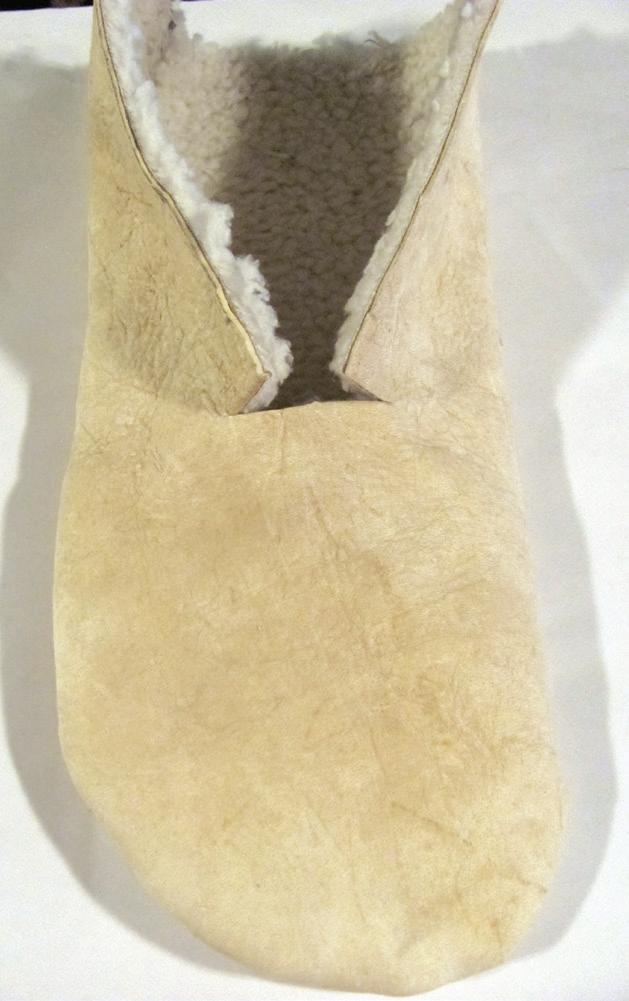

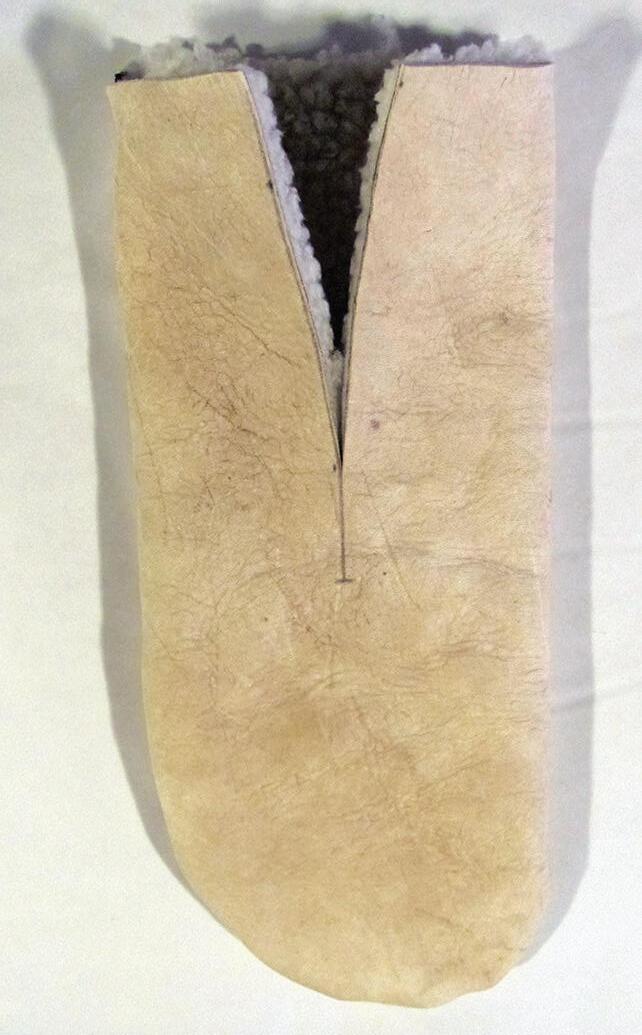

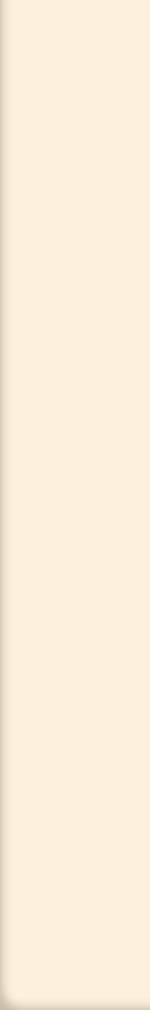

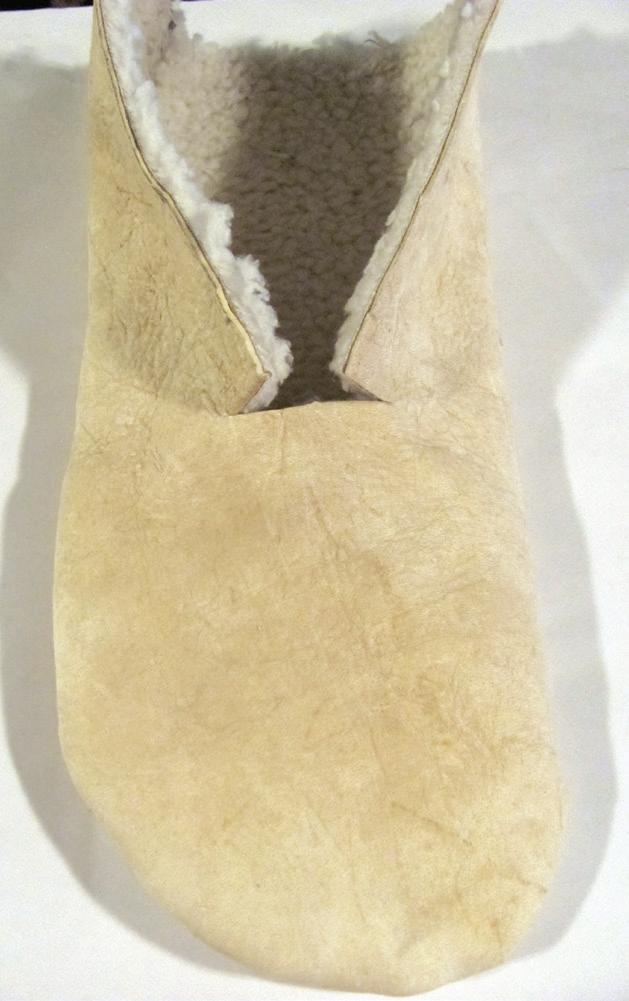

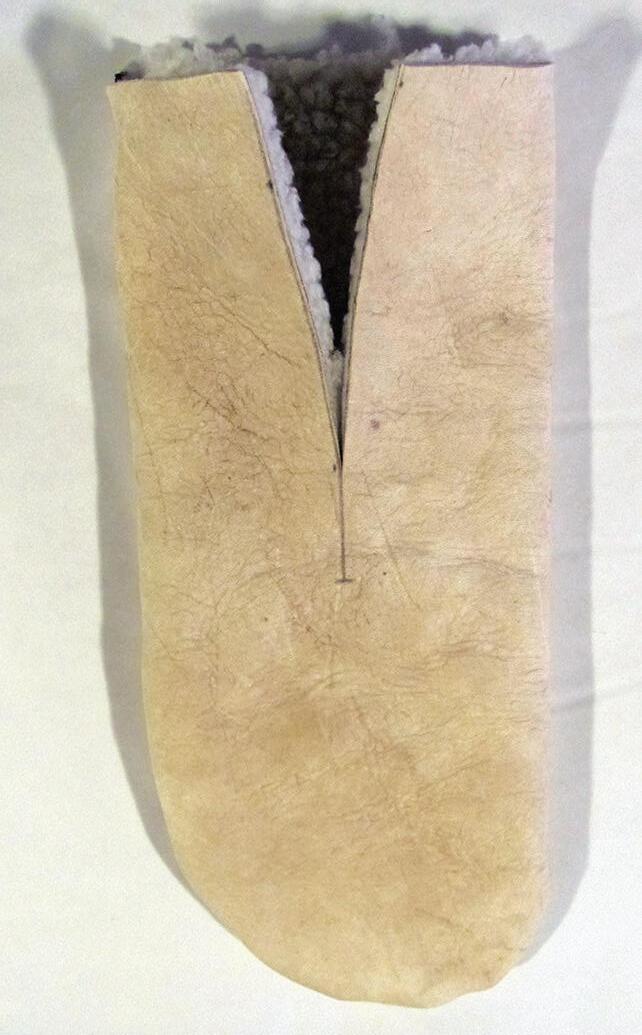

108 Sew Your Own Moccasins

Take your tanned animal skins one step further by turning the leather into comfortable, durable footwear.

54 72 98 58 84 108

Mother Earth News YouTube Channel

Visit

Beeswax Candle Making

Jessica and Q demonstrate how to make your own beeswax candles in this fun, easy project. Learn how to create your own at goo.gl/SCD7X4.

DIY Indoor Herb Garden

Enjoy the convenience of bringing your herb garden indoors. Join Jessica and Nancy as they discuss and demonstrate the benefits of a DIY indoor herb garden. You can watch now at goo.gl/HB3Lfn.

Easy Soap Making

Avoid the harsh chemicals found in store-bought soaps. Tag along with Charlotte and Q as they walk through the steps of making your own custom soap at home. Get started now at goo.gl/Lb8kyd.

Solar Cooking

Harness the sun’s energy for an eco-friendly cooking method. Russell and Jessica test out a variety of solar cookers to help determine which style will best fit your needs. Find out more at goo.gl/ieEY6M.

Making and Pressing Easy Farmer’s Cheese

Enjoy fresh homemade cheese and have fun making it. Watch as Q and Jessica prepare and press Easy Farmer’s Cheese. Visit goo.gl/q7Hsn2 now.

PREMIUM SERIES • SPRING 2019

GUIDE TO LIVING ON LESS

Special Content Team Editor Christian Williams

Group Editor Jean Teller

Assistant Editor Haleigh McGavock

Convergent Media

Brenda Escalante 785-274-4404; BEscalante@OgdenPubs.com

Art Direction and Pre-Press

Assistant Group Art Director Matthew T. Stallbaumer

Pre-Press Kirsten Martinez

Website

Digital Content Manager Tonya Olson

Display Advertising

800-678-5779; AdInfo@OgdenPubs.com

Newsstand

Melissa Geiken; 785-274-4344

Customer Service

800-234-3368; CustomerService@OgdenPubs.com

Publisher Bill Uhler

Editorial Director Oscar H. Will III

Circulation & Marketing Director Cherilyn Olmsted

Newsstand & Production Director Bob Cucciniello

Sales Director Bob Legault

Group Art Director Carolyn Lang

Director of Events & Business Development Andrew Perkins

Information Technology Director Tim Swietek

Finance & Accounting Director Ross Hammond

Mother Earth News (ISSN 0027-1535) is published bimonthly by Ogden Publications Inc., 1503 SW 42nd St., Topeka, KS 66609. For subscription inquiries call 800-234-3368. Outside the U.S. and Canada, call 785-274-4365; fax 785-274-4305.

© 2019 Ogden Publications Inc. Printed in the U.S.A.

MOTHER EARTH NEWS DIGITAL 68C 100Y 24K Pantone 363C THE ORIGINAL GUIDE TO LIVING WISELY

youtube.com/motherearthnewsmag to find more sustainable lifestyle videos to help you on your homesteading journey, and be sure to subscribe to receive updates on additions to the channel.

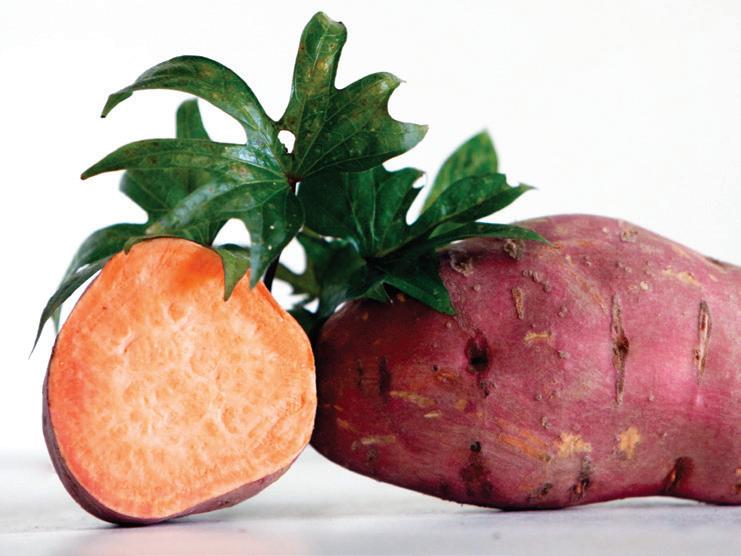

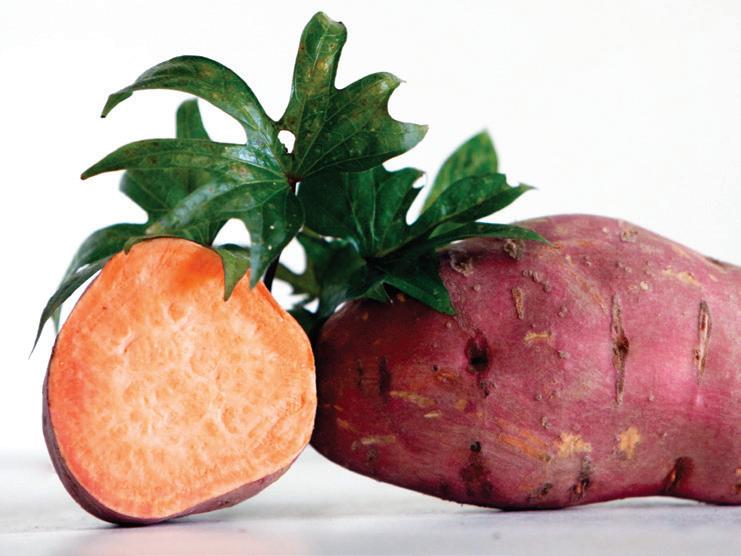

GROW $700 OF FOOD in 100 Square Feet!

By Rosalind Creasy with Cathy Wilkinson Barash

By Rosalind Creasy with Cathy Wilkinson Barash

Ireceive lots of questions about growing food to help save money. While working on my book, Edible Landscaping , I had an aha! moment. As I assembled statistics to show the wastefulness of the American obsession with turf, I wondered what the productivity of just a small part of American lawns would be if they were planted with edibles instead of grass.

I wanted to pull together some figures to share with everyone, but calls to seed companies and online searches didn’t turn up any data for home harvest amounts—only figures for commercial agriculture.

From experience, I knew those commercial numbers were much too low compared with what home gardeners can get.

For example, home gardeners don’t toss out misshapen cucumbers and sunburned tomatoes. They pick greens by the leaf rather than the head, and harvests aren’t limited to two or three times a season.

For years, I’ve known that my California garden produces a lot. By late summer, my kitchen table overflows with tomatoes, peppers, and squash; in spring and fall, it’s broccoli, lettuces, and beets.

But I’d never thought to quantify it. So I decided to grow a trial garden and tally up the harvests to get a rough idea of what some popular vegetables can produce.

The Objective

I took a 5-by-20-foot section of garden bed by my tiny lawn to see how much I could grow in just 100 square feet.

My goal was to produce a lot of food,

and because it was part of my edible landscape, it had to look good, too.

The Plants

I wanted to make this garden simple—something anyone could grow. I didn’t include fancy vegetable varieties; I chose those available at my local nursery as transplants. I also selected vegetables that are expensive to buy at the supermarket, as well as varieties that my experience has told me produce high yields.

WWW.MOTHEREARTHNEWS COM 5

If more of us grew a little food—instead of so much grass—our savings on grocery bills would be astounding.

ROSALIND CREASY; PAGE 4: SAXON HOLT & ROSALIND CREASY

By carefully planning each step, Creasy thoughtfully integrated her garden into her yard.

The first season I grew the following:

• Two tomato plants: ‘Better Boy’ and ‘Early Girl’

• Four basils (expensive in stores but essential in the kitchen)

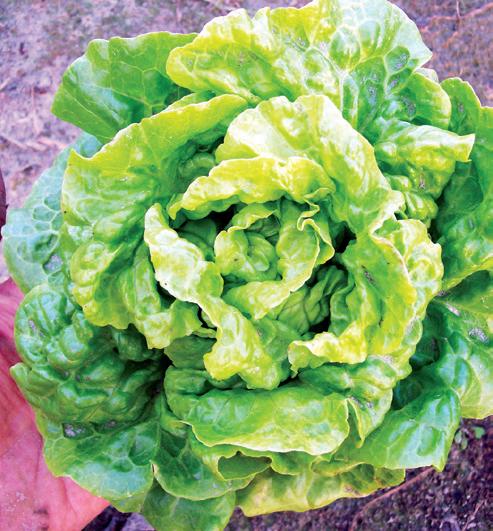

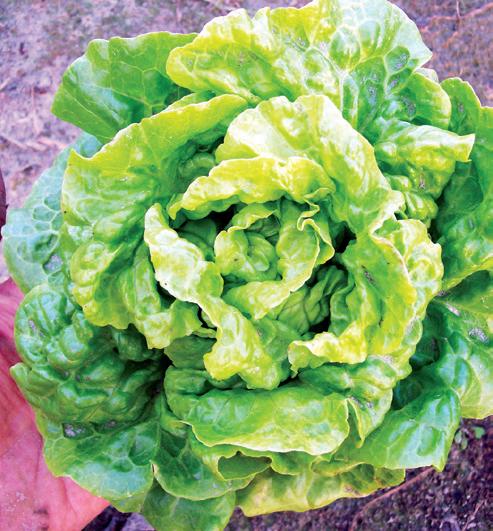

• 18 lettuces: six ‘Crisp Mint’ romaine, six ‘Winter Density’ romaine, and six ‘Sylvestra’ butterhead

• Six bell peppers, which are often luxuries at the market when fully

colored: two ‘California Wonder,’ two ‘Golden Bell,’ one ‘Orange Bell,’ and one ‘Big Red Beauty’

• Four zucchinis: two green ‘Raven’ and two ‘Golden Dawn’

The only plants I grew from seed were the zucchinis. Hindsight is always 20/20: I should have thinned each of the zucchini hills to a single seedling, but I left two in each hill. As a result, I needed to come up with creative uses for zucchini, including giving them away as party favors at a dinner I hosted.

It looked a bit barren at first, but the garden flourished—especially the lettuces. Within several weeks, I started picking outer leaves for salads for neighbors and myself. The weather forecast predicted temperatures in the upper 90s; I was heading out of town and feared the lettuces would bolt, so I harvested the entire heads earlier than I normally would. Within about a month of transplanting

6 MOTHER EARTH NEWS • PREMIUM GUIDE TO LIVING ON LESS

the lettuces

Luscious homegrown tomatoes, spicy basil, robust squash, and always-prolific zucchini were harvested from Creasy’s 100-square-foot garden bed.

In her garden, the author grew (from left) ‘Celebrity’ tomatoes on the green trellis; two basil plants in front; ‘Raven’ zucchini with three chard plants behind it; ‘Musica’ string beans on a tipi; an arbor with ‘Early Girl’ tomatoes; two collard plants; and two ‘Blushing Beauty’ bell peppers.

into the garden, I had grown enough for 230 individual servings of salad.

And by that time, the tomatoes, zucchinis, and pepper plants had nearly filled in the bed.

A Living Spreadsheet

Although I’ve grown hundreds of varieties of vegetables over the years and kept rough notes, this garden was different. My co-author Cathy created spreadsheets for each type of plant, and we kept meticulous records each time we harvested.

We recorded amounts in pounds and ounces, as well as the number of fruits (for each cultivar of tomato, zucchini, and pepper) or handfuls (for lettuces and basil).

The Investment: Time and Money

This 100-square-foot plot took about eight hours to prepare, including digging the area, amending the soil, raking it smooth, placing stepping stones, digging the planting holes, adding organic fertilizer, and setting the plants and seeds in the ground.

On planting day, I installed homemade tomato cages (store-bought ones are never tall or sturdy enough) and

drip irrigation. And I mulched well— a thick mulch is key to cutting down on weeding, which is the biggest time waste in the garden, in my opinion. We hand-watered the bed for a few weeks to allow the root systems to grow wide enough to reach the drip system. Three times during the first month we routed out a few weeds, which was only necessary until the plants filled in and shaded the soil.

Tomatoes in my arid climate are susceptible to bronze mites that cut down on the harvest and flavor. To prevent mites, we sprayed sulfur in mid-July

Getting the Most Food from a Small Area

Choose indeterminate tomatoes. They keep growing and producing fruit until a killing frost. (Determinate varieties save space but ripen all at once.)

In spring, plant cool-season vegetables, including lettuce, arugula, scallions, spinach, radishes, mesclun, and stir-fry green mixes. They are ready to harvest in a short time, and they act as space holders until the warm-season veggies fill in.

Grow up. Peas, small melons, squash, cucumbers, and pole beans have a small footprint when grown vertically. Plus, they yield more over a longer time than bush types.

Plants such as broccoli, eggplant, peppers, chard, and kale are worth the space they take for a long season. As long as you keep harvesting, they will keep producing until frost.

and again in mid-August, which took about 30 minutes each time.

In rainy climates, gardeners often need to prevent early blight on tomatoes. To do so, rotate tomato plants to a different area of the garden each year and mulch well.

After the plants are a few feet tall, remove the lower 18 inches of leafy stems to create good air circulation.

For the rest of the season, we tied the tomatoes and peppers to stakes as they grew upward, cut off the most rampant branches, and harvested the fruits. The time commitment averaged about an

WWW.MOTHEREARTHNEWS COM 7 ROSALIND CREASY (4)

Author Rosalind Creasy in her landscaped Northern California vegetable garden.

Even after factoring in the expense of some plants and fertilizer, a small garden can still save you big bucks on groceries.

hour and a half each week. (Our harvesting consumed more time than average because we counted, weighed, and recorded everything we picked.)

The Results

To determine what my harvest would cost in the market, I began checking out equivalent organic produce prices in midsummer.

On a single day in late August, I harvested 49 tomatoes, nine peppers, 15 zucchinis of many sizes, and three handfuls of basil—which would have totaled $136 at my market that day. From April to September, this little organic garden produced 77.5 pounds of tomatoes, 15.5 pounds of bell peppers, 14.3 pounds of lettuce, and 2.5 pounds of basil—plus a whopping 126 pounds of zucchini! Next time I won’t feel bad about pulling out those extra plants.

I figured the total value of my summer trial garden harvest was $746.52. In order to get a fair picture, I also needed to subtract the cost of seeds, plants, and compost (I can’t make enough to keep up with my garden), which added up to $63.09.

That leaves $683.43 in savings on fresh vegetables. Of course, prices vary throughout the season and throughout the country.

I live in Northern California, and for comparison, Cathy, who lives in Iowa, checked out her prices and figured the same amount of organic produce in her area would be worth $975.18.

The Big Picture

I started this garden to see what impact millions of organically grown 100-square-foot gardens would have if they replaced the equivalent acreage of lawns in this country. According to the Garden Writers Association, 76 million U.S. households gardened in 2013.

If just half of them (38 million) planted a 100-square-foot garden, that would total 87,235 acres (about 136 square miles) no longer

in lawns, and there’d be no need for the tremendous resources that go into keeping them manicured.

If folks got even half of the yields I got, the national savings on groceries would be stupendous: about $26 billion! So, a 100-square-foot food garden can be a big win for anyone who creates one—and for our planet.

Looking Forward

I have decided to continue keeping the records from my 100-square-foot garden indefinitely.

In the fall, I planted broccoli, chard, snap peas, cilantro, kale, scallions, and a stir-fry greens mix. This took much less time, as the soil preparation was done and the drip system was already in place.

The following summer, I planted different tomato varieties, added cucumbers, a tipi of pole beans, chard, and collards. Remember, I was growing all of this in a bed that is just 5-by-20 feet!

Read More, Share Your Results

My lecture audiences, the media, and visiting gardeners are excited to report about how much food a garden can produce.

Other organizations are on the same wavelength. In spring of 2008, Burpee started to record harvest amounts; Roger Doiron of Kitchen Gardeners International kept a tally of his family’s summer garden (find it online at www. seedmoney.org); and M E N put out a call for readers to share information about their most productive plants.

You can read this article online (go to goo.gl/gA9SB6), and share your garden totals by posting a comment. We’re looking forward to hearing about harvests from folks all over the country.

8 MOTHER EARTH NEWS • PREMIUM GUIDE TO LIVING ON LESS

Creasy’s pet rooster, Mr. X, checks out the lush, rich vegetable garden.

ROSALIND CREASY (2)

Within a month, just 18 plants yielded 230 individual servings of salad!

Rolls & Sheets for: • Conventional growers • Organic growers • Landscapers • Small gardens • Large gardens WeedGuardPlus enriched with fertilizer, humic acid to condition soil, or calcium to prevent blossom end rot. plastic, WeedGuardPlus is porous, so rainwater or overhead irrigation can be used for watering. Increases Yields. In a recent study zucchini grown with fertilizerenriched WeedGuardPlus yielded more fruit than the control soil. For more information or to order: 800-654-5432 www.WeedGuardPlus.com Biodegradeable Organic

weeding

yield

tape under weed block

tape over weed block

irrigation Porous -- plants breathe 100% biodegradable

pick up and disposal

under to enrich soil

fertilizing Plastic WeedGuardPlus X X X X X X X X X X X X WeedGuardPlus w/ Fertilizer X X X X X X X X X Please visit our website for special offers www.WeedGuardPlus.com

Paper Mulch Eliminates

Increases

Drip

Drip

Overhead

Requires

Plow

Self

Effortless Homemade ELDERBERRY SYRUP

A reader shares how to make medicinal elderberry syrup at home.

By Carrie Williams Howe

By Carrie Williams Howe

If you’ve walked into a health food store lately, you’ve no doubt seen a proliferation of syrups, tonics, and homeopathic medicines made with elderberries (Sambucus nigra). These products are meant to prevent and treat cold and flu symptoms and to boost your immune system, and often include honey as well.

It’s no surprise that herbalists everywhere are combining elderberry and honey. According to information on the Penn State Milton S. Hershey Medical Center website, “Some evidence suggests that the chemicals in elder flower and berries may help reduce swelling in mucous membranes, including the sinuses, and help relieve nasal congestion. Elder may have anti-inflammatory, antiviral, anti-influenza, and anticancer properties.”

Honey is likewise well-known for its medicinal qualities—it can soothe a sore throat and calm a cough, and it’s thought to boost immunity and fight allergies.

While I’m a huge fan of herbal medicines, and I’ve found success with some of these elderberry supplements, I’ve had two complaints when I shopped for them in the store: cost and ingredients. A small jar of elderberry syrup can cost upward of $20,

Making your own elderberry syrup is both rewarding and cost-effective.

G ETTY I MAGES /M ADELEINE _S TEINBACH 10 MOTHER EARTH NEWS • PREMIUM GUIDE TO LIVING ON LESS

and many products contain alcohol, which doesn’t taste good to me and makes me not want to give the product to my children.

Rest assured, you can make a great elderberry syrup at home with just a few simple ingredients and a little bit of time. This is especially true if you grow your own elderberries or keep your own bees!

If you don’t have fresh elderberries on your property, or you can’t get them from a local farmer, look for a reputable source of dried elderberries, such as an herbalist or a natural foods store (a good online source is www.mountainroseherbs.com). We grow our own black elderberries, the most common elderberry in North America. Many types of elderberries can be toxic when raw, so cook the berries thoroughly.

Here’s a simple elderberry syrup recipe that will keep for a couple of months in your refrigerator. You can dole it out in spoonfuls just like cough medicine, or you can stir it into your morning juice or tea (stick to a dosage of about 1 teaspoon for kids or 1 tablespoon for adults). Just to be safe, consult your doctor before taking elderberry syrup, because it may not be suitable for you.

We add cinnamon, ginger, and cloves to our syrup because these spices also seem to

be beneficial for fighting colds. You can use powdered or ground spices, but I prefer dried whole spices because they’re generally fresher and also much easier to strain out.

If you’re brave, you can experiment with adding a little cayenne pepper, but we don’t

think our kids would be quite so cooperative if we did that.

Elderberry Syrup

For a fraction of the cost of storebought, you can make this simple, homemade elderberry syrup.

Yield: 1 pint.

• 1 cup fresh or frozen black elderberries (or 3⁄4 cup dried)

• 2 cinnamon sticks

• 1 tablespoon fresh ginger, sliced

• 1 tablespoon dried whole cloves

• 31⁄2 cups water

• 1 cup local honey

Directions: Place the elderberries, cinnamon sticks, sliced ginger, whole cloves, and water in a saucepan. Bring the mixture to a boil, then reduce heat and simmer until the liquid is reduced by half, about 45 minutes.

Remove the pan from the heat and allow the syrup to cool. Strain out the berries and spices using a fine-meshed sieve or colander and discard.

Add the honey to the remaining liquid. Pour the mixture into a pint-sized mason jar.

Store your homemade elderberry syrup in the refrigerator, where it should keep for about 2 months.

www.MotherearthNews coM 11 c arr e W I lllams h o W e (2)

Elderberries, cinnamon, ginger, cloves, and honey come together to create a healthful syrup.

FREEZING FRUITS AND VEGETABLES From Your Garden

Round out your food preservation regimen! Tap these straightforward freezing tips to turn your garden harvests into sensational, off-season meals.

By Barbara Pleasant

Freezing is a fast and easy form of food preservation, and many crops, including asparagus, broccoli, green beans, peppers, summer squash, dark leafy greens, and all types of juicy berries, will actually be preserved best if frozen. Part of the beauty of freezing fruits and vegetables is that you can easily do it either in small batches—thus making good use of odds and ends from your garden—or in one big batch of your homegrown harvest or of peak-season, discounted crops from the farmers market. Unlike with canning, you don’t have to pay attention

to acidity or salt when freezing vegetables. Instead, you can mix and match veggies based on pleasing flavors and colors—for instance, a combination made up of carrots for color, bulb fennel for texture, and green-leafed herbs for extra flavor. You can include blanched mild onions in your frozen combos (a good use for bolted onions that won’t store well), but don’t include garlic, black pepper, or other “seed spices,” which can undergo unwanted flavor changes when frozen.

The greatest amount of space in my freezer belongs to vegetables, mostly stored in freezer bags that stack nicely because I first freeze the vegetables flat on

cookie sheets. I also allot freezer space for odd-shaped packages, such as those for cabbage leaves that have been blanched and frozen flat for making cabbage rolls in winter. I even steam-blanch and freeze an assortment of hollowed-out, stuffable veggies, such as pattypan squash, zucchini, small eggplant, and peppers. By season’s end, the contents of my freezer reflect the full diversity of my garden.

Freezing Basics

Only use fruits and veggies in excellent condition that have been thoroughly cleaned. Most vegetables you plan to freeze should be blanched for two to five

Crops That Freeze Well

minutes, or until they are just done. Blanching—the process of heating vegetables with boiling water or steam for a set amount of time, then immediately plunging them into cold or iced water—stops enzyme activity that causes vegetables to lose nutrients and change texture. The cooled veggies can then be packed into bags, jars, or other freezer-safe storage containers. Fruits or blanched vegetables can also be patted dry with clean kitchen towels, frozen in a single layer on cookie sheets, and then put into containers. Using cookie sheets for freezing will ensure the fruits and vegetables won’t all stick together, thus allowing you to remove a handful at a time from the container.

Unless you’re freezing liquids, which require space for expansion, you should remove as much air as possible from within the freezer container. With zip-close freezer bags, you must squeeze out the air by hand, whereas a vacuum sealer will suck out air as it seals the bags. Vacuum sealing reduces freezer burn (the formation of ice crystals that refreeze around the edges of the food and damage its taste and texture) because the crystals have no space in which to form. To read more about freezer-safe container options, see “Can You Freeze in Canning Jars?” on Page 14.

According to the National Center for Home Food Preservation (NCHFP, nchfp.uga.edu), fruits and vegetables will last in the freezer for eight to 12 months if prepared and stored properly. Vacuum-seal bags cost more than regular freezer bags, but devotees say they are worth the extra expense because they make frozen foods last even longer.

Great-Tasting Tomatoes

At one time or another, I’ve been so crunched for time that I stored excess tomatoes simply by washing them and tossing them into a freezer bag. This method provides plenty

of tomatoes for soup or sauce, and frozen, whole tomatoes peel like magic when held under running water. If you want to retain the skins for nutritional reasons, you can run half-thawed tomatoes through a food processor. (At this point, you’ll be

glad if you cored the tomatoes before you froze them.)

Frozen, whole tomatoes take up lots of freezer space, and because the tomatoes will not have been heated before they were frozen, enzyme activity may cause some loss of vitamins and other nutrients. This won’t happen, however, if you gently stew your tomatoes in their own juice before freezing them. After removing cores and skins, which you can do by blanching them, bring the coarsely chopped tomatoes to a gentle simmer for about 10 minutes, or until the tomatoes are tender. Allow to cool. If desired, you can ladle off some of the juice from the top and freeze it separately. Removing some of the juice will give you a frozen product similar to diced or stewed tomatoes in cans.

You can also include selected veggies and herbs in the mix when freezing tomatoes, and let the simmering tomatoes serve as the blanching liquid. For example, you could add chopped peppers and cilantro to a batch intended for use as a chili base; combine okra, peppers, and thyme in jambalaya mixtures; or throw in everything from eggplant to zucchini for veggie stews.

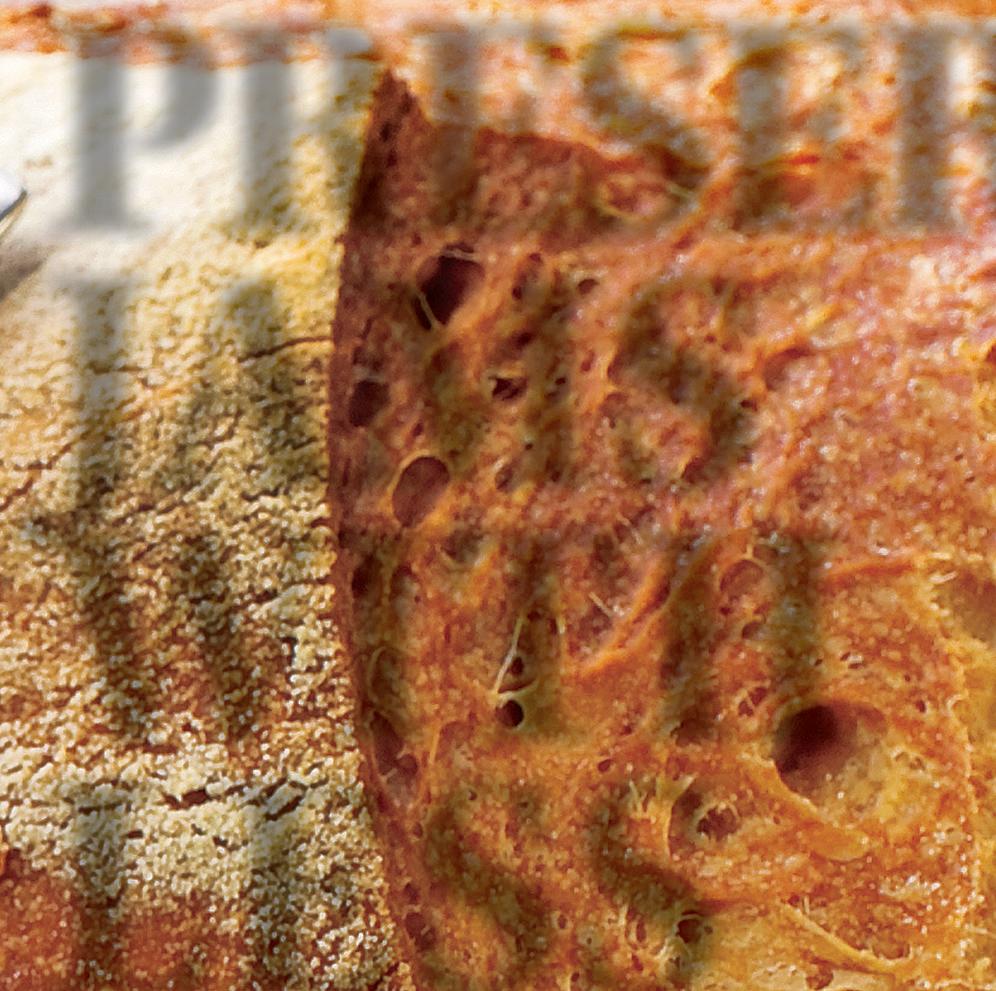

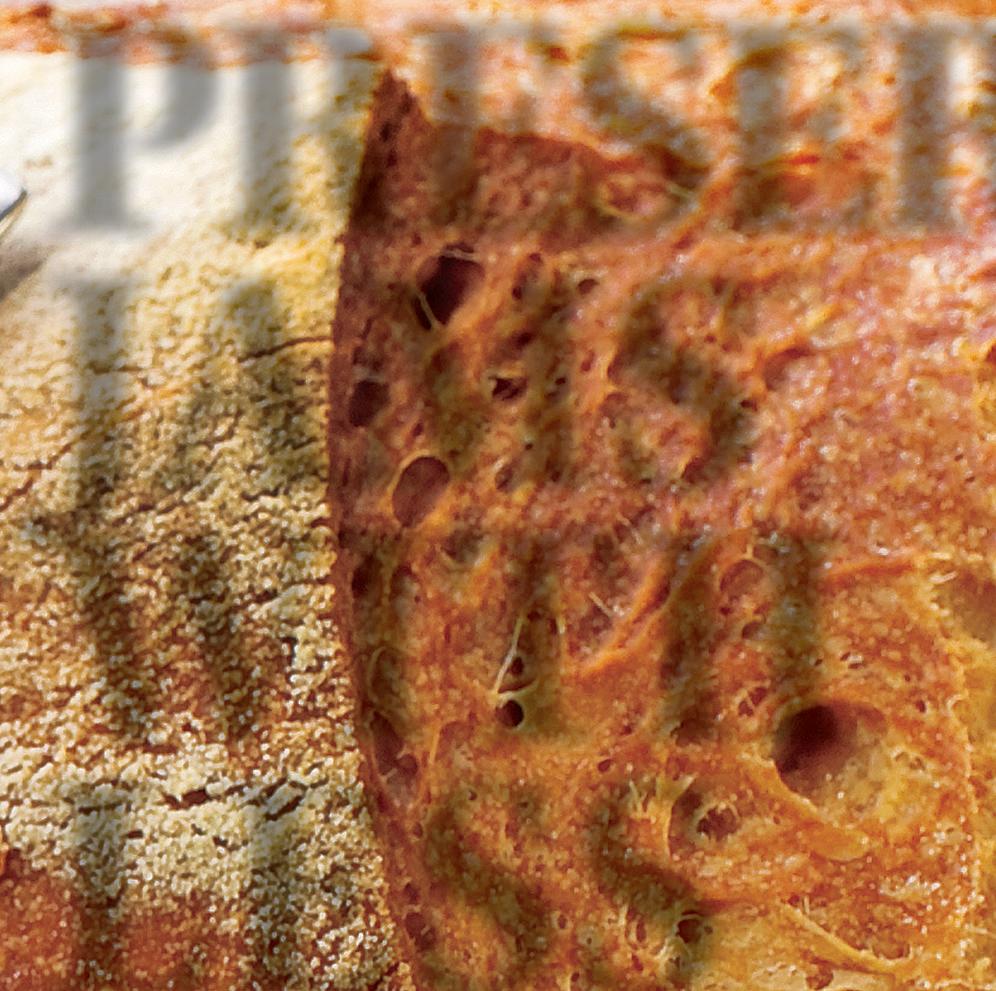

I freeze a few quart bags each of whole cherry tomatoes and stewed tomatoes along with dozens of tomato-based veggie mixtures, but the trick to having the best-tasting frozen tomatoes is to dry them halfway first, as is done in the recipe for Half-Dried Tomatoes (see Page 15). Removing some of the moisture from tomatoes will intensify their flavor, save freezer space, and give you the ideal tomato for pizza or pasta sauce.

Tip: If you have a small amount of tomato sauce left over from canning, keep it in the fridge and use it as a broth when freezing vegetables, such as summer squash or eggplant.

Buckets of Beans

You can freeze most types of snap beans, including yard-long beans.

WWW.MOTHEREARTHNEWS COM 13

To prepare vegetables for blanching, clean them thoroughly. You can cut the vegetables into uniform pieces so they cook evenly.

To blanch, submerge the vegetables in boiling water for the amount of time given for what you’re freezing (for more information, go to goo.gl/9at6VE ).

Transfer the vegetables from the boiling water to iced or cold water. The water should be 60 degrees Fahrenheit or colder. After they’ve cooled, pack them into containers.

Asparagus Berries Broccoli Carrots Cauliflower Chard Collards Corn Eggplant Green beans Herbs Kale Kohlrabi Okra Peas Peppers Rhubarb Spinach Squash Tomatoes CLOCKWISE

FROM LEFT: DREAMSTIME/BRIANHOLM; FOTOLIA (3)/MSPHOTOGRAPHIC, CHRISTOPHER HALL, ANDREW LEWIS

The more substantial the bean, the better the finished frozen product. For example, pencil-thin filet beans soften too much when blanched and frozen, but bigger, firmer green beans are fine freezer candidates. Most pole beans freeze especially well, but my best batches of frozen beans come in fall, when I slow-cook savory shelly beans and freeze them.

After blanching your green beans, you can put them directly into freezer containers, or pat them dry and pre-freeze them on a cookie sheet first. You can also freeze shelly beans in their cooking juices. When cooking thawed green beans, try using “dry” cooking methods, such as braising them in a little butter or olive oil, or making green bean oven “fries.”

Can You Freeze in Canning Jars?

A few summers ago, a visiting friend was aghast when I poured blackberry juice into a canning jar and screwed on a used lid before stashing the container in the freezer door. She said I had broken two rules: freezing in canning jars and reusing canning lids. But some rules can be carefully broken. You can freeze in clean canning jars as long as you leave plenty of headspace, because liquids expand as they freeze. I leave 11⁄2 inches in pints and 2 inches in quarts.

Used lids should never be reused for canning, as these can’t be trusted to form a sound seal. But you don’t want a seal when freezing in canning jars. I screw lids on loosely at first, and then tighten them after the jars have frozen solid. I mostly use canning jars for freezing fruit and veggie juices, which are messy to handle in bags. I also use canning jars for freezing dried veggies, which will last two years in the freezer but only about one year on a pantry shelf.

You may opt to freeze your produce in glass containers if you’re concerned about chemicals that can leach from plastics onto your food. Most freezer bags are made of No. 4 LDPE (low-density polyethylene), which is not known to leach chemicals. If you’re worried about putting hot food into plastic, however, wait until the food cools before packing it into bags. For more on safely storing food in plastic, go to goo.gl/BHf9Gv.

Tip: Purple-podded bean varieties can be used as blanching indicators on freezing day. Their purple hue will change to green when the beans are perfectly blanched.

Preserving Peppers

Opinion is divided over whether blanching is required when freezing peppers. Chopped, raw peppers stashed in freezer-safe containers will keep nicely for several months, but you can also try other methods for freezing peppers. I often cut ripe sweet peppers into halves or quarters for stuffing, then steam-blanch and freeze the pepper “boats” individually on cookie sheets. After they’re frozen, they can be nested together and packed in freezer bags. If I run out of chopped peppers, I start using the peppers I set by for stuffing.

Some peppers have wonderfully complex flavors that intensify if the peppers are roasted, grilled, or smoked before they’re frozen (for a Fire-Roasted Peppers recipe, see Page 15). Roasted peppers cooked over a hot fire until just done and then stashed in freezer bags are among the best-tasting foods produced by my garden and kitchen.

Tip: Always wear protective gloves when handling hot peppers. Putting on gloves is much easier (and less painful) than removing capsaicin—the compound that makes peppers hot—from your hands.

Saving Summer Squash

Despite their beauty and productivity, summer squash—including zucchini, yellow squash, and pattypans—are lightweights in the flavor department. They’re also prone to degradation from enzyme activity, so they must be thoroughly blanched before they’re frozen. I like to hollow out single-serving-sized pattypans and zucchinis for stuffing, and then steam-blanch them before freezing.

14 MOTHER EARTH NEWS • PREMIUM GUIDE TO LIVING ON LESS

A freezer of food will lead to refreshingly fruity smoothies, savory dishes packed with summer flavors, and a stuffed-pepper supper in a flash.

The standard procedure for freezing summer squash is to blanch half-inch slices in boiling water or steam for three minutes. Because I’ll use most of my frozen squash in casseroles or soups, I often add more colorful vegetables and herbs to bags of frozen squash—for example, chopped basil, sliced carrots, and ribbons of kale. When thawed, the squash mixtures seem like summer in a bag.

Another method for freezing summer squash is to slice zucchini horizontally into large, flat slices before blanching. These can be grilled or used to make roll-ups. You can also freeze blanched and grated squash to add to all kinds of baked goods.

Sweet Corn Suggestions

When we asked the M E N Facebook community (www. facebook.com/motherearthnewsmag) about their favorite ways to freeze sweet corn, many respondents raved about the flavor of sweet corn that had been frozen raw in the husks, as described by Arkansas reader Betty Heffner: “The best method I’ve found is to pull back the husks to remove the silks and cut off any damage from the tips, then smooth the husk back over the corn before freezing it.” Many folks attested that this easy method preserves fresh corn flavor for six months, though it’s not among the approved processes for freezing corn listed by the NCHFP.

Experts recommend blanching sweet corn before freezing it, which locks in taste, texture, and nutrition. You can freeze whole, blanched ears if you have freezer space, or cut the kernels from blanched, cooled ears and freeze only the kernels. I like to cut the kernels raw, press out some juice, and bring the mixture barely to a simmer before cooling and freezing it. I then compost my cobs, but a tip from Carolyn Vellar of Kansas City, Mo., made me realize I’ve been doing so prematurely. Carolyn simmers her bare cobs to make corn broth, which she freezes for use in winter soups.

New Mexico reader Diana McGinn Calkins freezes kernels cut from blanched, cooled ears when she has no freezer space left for raw ears in the husk. “I get as much air out as possible and

then flatten out the bag of corn. After it’s frozen, I break it up and put it back into the freezer. Then I can take out as much as I want.”

For sweet corn that’s ready to heat and eat, try this easy roasting method from Katrina Steele of Howard, Ohio:

“We cut the corn off the cob and pile it in a big pan with a stick of butter and enough milk to cover the bottom of the pan. Then we bake it at 350 F until piping hot, stirring every 10 minutes. After it cools, we spoon it into freezer bags. Tastes wonderful!”

Flavor-Packed Freezer Recipes

Fire-Roasted Peppers

Wash peppers and cut out any blemished spots.

Place whole peppers on a hot grill or under a hot broiler. Use tongs to turn peppers as needed until they’re blistered on all sides, with brown and black patches.

Place the hot, roasted peppers in a large pot with a lid or enclose them in a paper bag. Allow them to cool. When the peppers are cool, use your hands and a table knife to remove loose pieces of skin. Cut peppers in half and remove cores. Freeze the roasted peppers on cookie sheets and then pack into freezer-safe containers. Roasted peppers can be used for dozens of recipes.

If you’re in a hurry, you can freeze whole, roasted peppers and then remove the skins by dunking them in warm water after they’ve been frozen. Their warm-water dunk makes them easy to chop, too.

Half-Dried Tomatoes

You can make these delicious morsels in an oven, in a food dehydrator, or out in the sun on a dry, sunny day.

If using your oven, preheat it to 250 F. Wash and dry ripe tomatoes. Cut paste tomatoes and cherry tomatoes lengthwise in half. Cut slicing tomatoes into quarters. Arrange the prepared tomatoes—with the cut sides facing up—on baking sheets that have rims to catch any juices. Sprinkle with sea salt. You can season the tomatoes with fresh herbs and a light drizzle of olive oil. Place in the oven for 1 hour, then reduce heat to its lowest setting. Dry for 2 more hours, or until the tomatoes flatten and the edges pucker.

When using a dehydrator, dry the tomatoes for about 4 hours.

To dry your tomatoes in the sun, lay them out on a screen or in a solar dehydrator (to build your own, see goo.gl/qNrBj7 ) and leave them outside in full sun until they have fully collapsed. If your tomatoes are exposed, cover them with a light cloth to deter bugs.

Freeze your half-dried tomatoes on cookie sheets, and then pack them into freezer-safe containers. Fully dried tomatoes take longer to dry, and won’t need to be frozen.

WWW.MOTHEREARTHNEWS COM 15

CLOCKWISE FROM LEFT: DREAMSTIME (2)/ALENA BROZOVA, NULLORNOTSET; FOTOLIA (3)/HENK JACOBS, ALI SAFAROV, MARINA KARKALICHEVA

BUY IN BULK for Big Savings on Better Food

seem intimidating if you don’t know beans about it. We’ll walk you through the key steps of buying in bulk from local farmers and, for even greater savings on more items, joining a food-buying club.

By Rebecca Martin and Dan Sullivan

We all have a taste for good food, but quality groceries can come at a high price. Whet your appetite with this money-saving advice: Purchasing bulk food is a highly effective way to cut expenses and eat locally. You may already shop the bulk department of your co-op or grocery store, but cutting out the storefront altogether can offer even more financial, environmental, and gastronomical benefits. Besides making your food shopping

easier and less frequent, bulk groceries are often of higher quality than packaged supermarket products. And the money savings will wow you: See our chart on Page 19 for specific savings on 20 items.

If you choose to eat organic, the savings from buying in bulk can be even more staggering: A 2012 study by the Food Industry Leadership Center at Portland State University found that consumers saved an average of 89 percent compared with supermarket costs when they bought large quantities of certain organic foodstuffs, including grains, beans, and spices. Buying food in bulk may

Member Benefits

Buying clubs are groups of individuals and families who merge their grocery lists to buy food in big quantities at close-to-wholesale prices. Clubs make a collective purchase once or twice per month, usually through a single wholesaler, nabbing substantial savings on large-quantity purchases of everything from toothpaste to whole grains.

As our chart shows, you can routinely save as much as 50 percent. Food-buying clubs also build community—members get to know each other while coordinating orders and volunteering time to divide the food.

16 MOTHER EARTH NEWS • PREMIUM GUIDE TO LIVING ON LESS

You can slash your family’s food costs in half— and support local farmers—by buying meat, produce, and dry goods in bulk.

SARAH GILBERT; PAGE 16: TOP: DOUG SNODGRASS; BOTTOM, FROM LEFT: SARAH GILBERT (2); TERRY WILD

Purchasing bulk food through a club requires thoughtful planning. You’ll need enough jars, bins, and tubs to pick up and store your portion of brown rice, wheat, nuts, and more. A chest freezer is a good investment to prevent large purchases of butter, meat, flour, and nuts from spoiling. Some clubs ask their members to chip in on shared freezers, a scale for dividing orders, and even a grain mill for grinding fresh flours.

Buying-club households usually waste less food because their cooking habits become grounded in a pantry mentality: Meal planning begins with the goods already stocked at home. Avoid purchasing unfamiliar foodstuffs until you’re sure you’ll eat them.

Try a small package from the grocery store first, so you don’t get stuck with a 10-pound bag of hull-intact buckwheat that needs to be ground twice to become a usable flour you end up not liking much. Keep track of what your family actually eats, too, and which foods linger on your pantry shelves despite your best culinary inventions.

Welcome to the Club

Hundreds of food-buying clubs are scattered all across North America. The staff at your local food co-op will probably be aware of any clubs in your area. If you can’t find one nearby, cook one up by following these steps.

(If your club is looking for new members, please add it to the Google map we’ve created at goo.gl/q57rLC so others can find you.)

Recruit members. Many clubs have at least 20 members because some wholesale food distributors require minimum orders of $500 or more. The bigger the group, the greater the savings, because large orders lead to volume discounts and reduced shipping costs. You can recruit members from among your friends, relatives, and groups you’re active in. Tack up a notice in the break room at work. Maybe schedule a brown-bag lunch meeting to discuss the benefits of buying in bulk and how a club might work. How often will

you order? Will you limit the types of goods purchased? Can members share (or “split”) cases and bags? If so, who will coordinate that step? When and where will your club take deliveries?

Select a vendor. You’ll want to choose companies that don’t limit their sales to commercial accounts when selecting a vendor for your club. See “Resources” on Page 20 for companies that sell to buying clubs, or contact an existing buying club for vendor recommendations.

You can also strengthen your area’s food system by buying some items directly from local producers.

Set up an ordering strategy. The Web has made compiling orders more convenient than ever for food-buying clubs.

www.MotherearthNews coM 17

Consider how you’ll store bulk food before you buy. Freezing fruits and vegetables (right) preserves their flavor and texture for up to 18 months.

Your local co-op is still a good bet for smaller quantities of packaging-free dry goods.

You can place an order with a credit card, and schedule a drop date and location entirely online. A few national distributors use e-commerce software that tallies totals in real time as members add items to a club-specific shopping cart, making it easy to see when minimums are met.

Most food-buying clubs have one or two point persons who take the lead in sending reminders, placing orders, and scheduling distribution. Your club may decide to reward these individuals with a higher markdown.

Distributors generally won’t ship partial cases, so holding monthly meetings is a good way for members to decide on splits. The savings are huge on a 25-pound bag of organic black beans— more than $2 per pound when compared with a 1-pound package—but unless your family truly loves a lot of legumes, dividing that bag with at least one other household will make the purchase more feasible.

Secure a drop-off location. A club can receive bulk food shipments at a member’s garage or possibly at a member’s workplace. Someone will need to be present to accept the goods and check the delivery against the original order for mistakes and out-of-stock items. Keep in mind that delivery locations without refrigeration will limit your ordering options.

Develop a distribution scheme. The cheaper prices your club receives for bulk food are often subsidized by volunteers who split the orders—they open up the bags and weigh, package, and label the contents based on each member’s order sheet.

Distribution helpers should receive deeper discounts because they volunteer their time, or the job should rotate through the club so everyone takes a fair turn.

Coordinating this splitting process may be more trouble than the savings are worth to your group. Some clubs forgo splits, so members must choose between smaller bags at a reduced discount or larger bags requiring proper long-term storage at home.

Pay the bills. Perhaps the busiest club member, the treasurer figures splits, sales taxes, and discounts, and ensures that all members pay their share. Some clubs rotate this task among members. Calculating splits is much easier when you use a spreadsheet, or you can register for the free club-specific software offered at www.foodclub.org.

Food for Thought

Now that you’ve learned how to save money on food by starting your own buying club, you’ll need some tips for keeping those volume purchases at optimal freshness and nutritional value until they end up on your plate. In addition to the following advice, “Save Money on Groceries” at goo.gl/Rv7Sb2 has more suggestions on storing sizable amounts of food.

Dry goods. Foodstuffs that don’t contain liquid are among the easiest items to store. Distributors offer dry goods—sometimes including rare varieties of beans, rice, and grains—in bags weighing anywhere from 1 to 50 pounds. The savings can be substantial, particularly on large bags of organic dry goods: A 50-pound sack of wheat berries costs less than 50 cents per pound, for example, while a 5-pound bag of organic whole-wheat flour at the supermarket runs as much as $1.80 per pound—nearly four times more!

Store dry beans in an airtight container in a cool, dry environment away from direct sunlight, and they’ll last well over a year. Nuts will keep in a refrigerator or freezer for up to two years.

Grains are a staple in almost every larder, but they’re challenging for longterm storage because of meal moths,

The bigger the buying club, the greater the savings: Large orders lead to volume discounts.

Buying in bulk reduces waste, especially when packing materials are reused (as they are in the Know Thy Food buying club in Portland, Oregon.

weevils and other pests. One way to break the life cycle of weevils is to freeze grains for at least a week before storing them in a dry, dark environment at 60 degrees Fahrenheit or cooler. Grains can be stored in a freezer indefinitely. When freezer space isn’t available, store grains

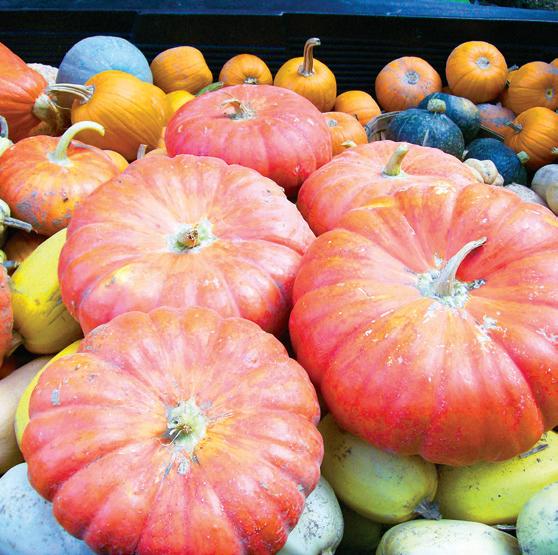

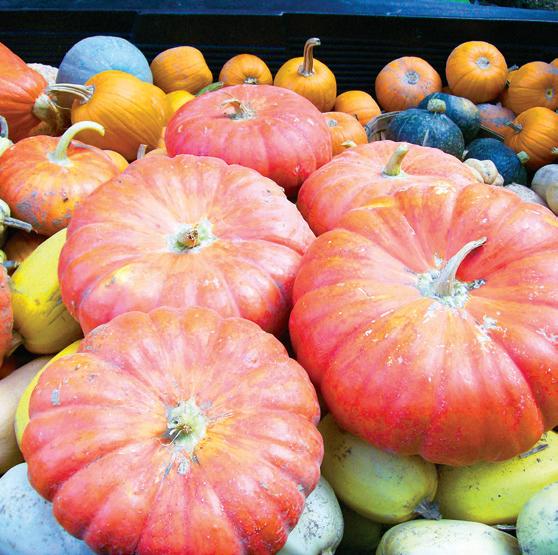

in 5-gallon plastic buckets with tight lids. Two 5-gallon buckets will easily hold 50 pounds of wheat berries. The buckets stack nicely and can be picked up at low—sometimes even no—cost from bakeries and fast-food restaurants. Produce. Mouthwatering, ripe pro-

duce is a lot cheaper if purchased in season from local growers. A bushel of conventional green peppers costs about 80 cents per pound at a farmers market in August, while a handful of peppers will be priced at $2 per pound at a grocery store in February.

Estimated Savings from Buying in Bulk

These estimates are averages of prices obtained from at least three vendors in January 2014.

Beef costs were figured assuming a yield of 225 pounds per side, packaged as 30 lbs. of ground beef, 50 lbs. of chuck and arm roasts, 20 lbs. of rib roasts and rib-eye steaks, 17 lbs. of short loin strip steaks, 20 lbs. of sirloin steaks, 50 lbs. of round and rump roasts, 13 lbs. of brisket, and 25 lbs. of flank and skirt steaks and short ribs. This mix of cuts from a side can vary based on the instructions you provide to the butcher. “Direct-from-Farmer Price” estimates include butchering costs.

All costs are per pound unless otherwise noted. “Food-Buying Club Price” estimates are based on bulk orders purchased from wholesale distributors in the quantities listed.

Fresh Produce In-Season, from-Farmer Price Supermarket Price Savings

“In-Season, from-Farmer Price” estimates are for 25-pound quantities of conventional produce purchased in season at farmers markets or from pick-your-own operations.

www.MotherearthNews coM 19

Side of Beef Direct-from-Farmer Price Supermarket Price Savings Conventional $3.97/lb. $6.56/lb. 39% Grass-fed $6.64/lb. $10.77/lb. 38% Certified organic $8.56/lb. $13.34/lb. 36%

Supermarket Price Savings Rice, long-grain white, enriched $0.50 (20-lb. bag) $0.90 (5-lb. package) 44% Rice, long-grain brown, organic $1.17 (25-lb. bag) $2.22 (2-lb. package) 47% Pinto beans, dry, conventional $0.88 (25-lb. bag) $1.64 (1-lb. package) 46% Pinto beans, dry, organic $1.11 (25-lb. bag) $2.49 (1-lb. package) 55% Pinto beans, canned, conventional $0.03 per oz. (108-oz. No. 10 can) $0.05 per oz. (one 15.5-oz. can) 45% Pinto beans, canned, organic $0.09 per oz. (twelve 15-oz. cans) $0.13 per oz. (one 15-oz. can) 35% Unbleached flour, conventional $0.56 (25-lb. bag) $0.48 (5-lb. package) -16% Unbleached flour, organic $0.73 (25-lb. bag) $1.35 (5-lb. package) 46% Peanuts, conventional $1.05 (25-lb. bag, roasted in shell) $1.90 (3-lb. package, in shell) 45% Peanuts, organic $2.78 (25-lb. bag, dry-roasted, shelled) $6.49 (1-lb. package, dry-roasted, shelled) 57% Potatoes, russet, conventional $0.22 (50-lb. bag) $0.51 (5-lb. bag) 57% Potatoes, russet, organic $0.76 (50-lb. bag) $1.26 (5-lb. bag) 40%

Dry Goods Food-Buying Club Price

Tomatoes $1.01/lb. $2.94/lb. 66% Green peppers $0.84/lb. $2.13/lb. 61% Blackberries $1.75/lb. $5.18/lb. 66% Apples $0.49/lb. $1.07/lb. 54% Strawberries $1.60/lb. $2.28/lb. 30%

SARAH GILBERT

True, freezing or canning all of that fresh produce will take some time, but the job won’t seem onerous if you preserve small batches several times a week or organize a canning bee with friends.

Crops need to be matched with their preferred storage conditions, because some fruits and vegetables like cold and moist settings while others prefer warm and dry ones. Find detailed advice for storing 20 common vegetables and fruits at goo.gl/aNmzRr.

The simplest way to squirrel away your stockpile of potatoes, carrots, and other root crops is to keep them in the ground under a thick blanket of mulch, in a trench silo or pit beneath a layer of soil, or inside a buried garbage can. Find instructions for making five easy outdoor root cellars at goo.gl/7yXAc2. Store winter squash and onions inside your garage, in a basement—even in a cool bedroom.

Canning is the traditional preservation method for most fruits and vegetables. To learn how to can, refer to the online Home Canning Guide at www.motherearthnews.com/canning. Another way to lock in taste and nutrition is by blanching and freezing (check out “Freezing Fruits and Vegetables from Your Garden” on Page 12). Most fruits and vegetables freeze well for up to 18 months.

Use energy from the sun to preserve fresh produce with a solar food dehydrator. Dehydrating with a solar (or electric) food dryer locks in peak flavor and nutrients while removing the moisture that causes fruits and vegetables to spoil. Store dried produce in jars or bags. Learn how to build a simple

solar food dryer using cardboard boxes at goo.gl/NFdJN9 or for a sturdier version, find plans for our Best-Ever Solar Food Dehydrator at goo.gl/kSCSZP.

Meat. The priciest line item in a nonvegetarian budget is usually meat. Buying beef and pork in bulk results in substantial savings, particularly on premium cuts. If you buy half a cow directly from a farmer, your take-home cuts can include roughly 17 pounds of strip and tenderloin steaks at about $3.97 per pound.

The savings are more than 63 percent when compared with 17 pounds of the same cuts purchased from a conventional grocery store at $11 per pound. And that’s just for conventional beef—don’t miss reviewing the savings from buying grass-fed and organic meat in large quantity in the chart on Page 19.

Buying meat in volume is a great way to build relationships with local farmers, too. Ask a butcher—maybe one at a local food co-op—where to buy hormone-free pastured animals from a reputable producer, or locate names via the pastured producers listings for your state online at www. americangrassfed.org, www.eatwild. com and www.localharvest.org.

Figure out how to store your portion of the animal before you buy. One cubic foot of freezer space holds 30 to 35 pounds of beef. After subtracting processing waste, a 1,000-pound cow yields about 450 pounds of meat from the whole animal, 225 pounds from a side (half a cow), or 110 pounds from a quarter. A 250-pound hog, slaughtered and dressed, produces about 144 pounds of cuts from the whole animal, or 72 pounds from a half.

Butchers and meat processors typically freeze cuts inside vacuum packs or wrapped in butcher paper. Freezing makes buying in bulk convenient, and fresh-frozen beef and pork are safe to eat indefinitely, although the quality begins to suffer after about six months to a year.

Now that you’re stocked up with tips on how to save money on food, just remember: Plan your household’s bulk purchases carefully, figure out how you’ll store the food, and take pride in keeping your belly full for less.

RESOURCES

WHOLESALE DISTRIBUTORS

SERVING BUYING CLUBS

www.assocbuyers.com (Northeast)

www.azurestandard.com (Entire U.S.)

www.cpw.coop

(Upper Midwest)

www.frontiercoop.com (Entire U.S.)

www.global-organics.com (Entire U.S.)

www.hummingbirdwholesale.com

(Pacific Northwest)

www.unfi.com

(Entire U.S.)

ORGANIC BULK FOODS

www.bobsredmill.com

www.edenfoods.com

www.healthybuyersclub.com

www.pleasanthillgrain.com

FIND LOCAL FARMERS

www.americangrassfed.org

www.eatwild.com

www.localharvest.org

www.pickyourown.org

www.ota.com

www.facebook.com/motherearthnewsmag

20 MOTHER EARTH NEWS • PREMIUM GUIDE TO LIVING ON LESS

Jars, bins, and a chest freezer are wise investments for storing bulk food purchases. One cubic foot of freezer space holds about 35 pounds of meat.

LEFT: FOTOLIA/VLORZOR; RIGHT: HANNAH KINCAID

Over 200 years ago, we grew organically because there was no other way.

200 years later, organic trees are back — and this time they’re USDA Certified Organic.

These special trees must meet rigorous inspection standards. No arti cial anything is permitted to touch them, or the land on which they’re grown. From eld to table, you will know exactly where your food comes from.

For your health ... for your family ... for the environment. It’s time.

Purely grown, from the roots up — just like Mother Nature intended

A

To get your FREE catalog, visit StarkBrosOrganic.com or call 800.325.4180

USDA CERTIFIED ORGANIC FRUIT TREES go �rganic... = 100%NON-GMO ...grow �rganic!

Introducing

A GROWING LEGACY SINCE 1816 D StarkBrosOrganic.com

PUT EXTRA FOOD TO GOOD USE 25 Fresh Ways to

Don’t scrap your scraps! Reduce food waste by transforming your leftover morsels into meals.

Edited by Amanda Sorell

The pleasures of home-prepared food made from fresh ingredients are many, but using up all those odds and ends that don’t make it into the meal can frequently pose a

challenge. Thankfully, conscientious cooks can control what happens to some of the nourishment that would otherwise go to waste. We asked editors, friends and fans how they anticipate and avoid food waste in their homes. Hundreds of responses poured in, showing that food “scraps” have

a solid standing in the kitchen, if only we help them live up to their potential.

Thrifty Tips

Plan ahead. Leftovers from Monday night’s roast chicken can become tacos on Tuesday and a robust salad on Wednesday. Planning your meals in advance is the first step toward buying only what you need, and using every last bit. This will keep you from filling your cart too full when you’re at the store—and from emptying your

22 MOTHER EARTH NEWS • PREMIUM GUIDE TO LIVING ON LESS

DREAMSTIME/ZIGZAGMTART

wallet too fast. Use a mini-chalkboard, whiteboard, or pinned-up printed calendar in your kitchen to list the week’s meals and keep yourself on track. Make your grocery lists accordingly, and when you do plan to cook something substantial, such as a whole chicken or roast, make sure your meals for the following nights incorporate the food that will be left over. Freeze your foods. Jessica Kellner, former editor-in-chief of Mother Earth Living, urges eaters to employ their freezers. “If I have browning bananas but no time to do anything with them, I’ll pop them into a freezer bag and save them for the next time I want to make banana-oat cookies, banana bread, or a smoothie,” Kellner says. “Same with most produce—if you have tomatoes that are about to go bad, stick them in the freezer, and then use them in a sauce, stew, or casserole later.”

Preserve herbs. If you buy bundles of fresh herbs from the store or farmers market—or have a lot to harvest from your garden—former Mother Earth News Managing Editor Jennifer Kongs has a recommendation for saving them: “If you can’t use the whole bunch within a week or two, chop the herbs, press them into an ice cube tray, and then cover them with water or olive oil. Freeze them, and then pull out a cube or two anytime you need to add an herbal lift to a dish. Drying is another good option: For rosemary, sage, thyme, and oregano, bundle and tie the ends together, and hang them in a dry place. When the herbs have fully dried, store them in a spice jar for up to a year.”

Compost. Reader Dorinda Troutman works her food scraps into a productive cycle that incorporates the entire homestead. “I have chickens, so anything left over in the kitchen or the bottom of the fridge ultimately goes to them, and they turn it into manure, which becomes compost and goes back on the garden to create more meals and leftovers,” she says. You can compost, too, no matter where you live or how much space you have. Read “How to Make Compost” at goo.gl/5pFi7k to get the dirt on a number of composting setups, including worm bins, tumblers, and a plain old hole in the ground.

Double up. Former Mother Earth News Senior Associate Editor Robin Mather, author of The Feast Nearby , minds her energy bills while also diminishing food waste: “If I’m going to cook something in the oven for a long time, such as a stew, I’ll typically also bake something alongside it, such as muffins or cookies,” she says. “Even if the secondary dish goes straight into the freezer, I’ve saved the energy needed to bake it.” You can tap this tactic by roasting a tray of vegetables while baking dinner or dessert, for example.

Mather also takes water conservation into consideration. “I use leftover water from my kettle to rinse off my dishes before putting them into the dishwasher,” she says. This water and any greywater you collect can also be used to water plants or even flush your toilet.

Remnant Revival

Those commonly discarded bits in your kitchen can add zeal to new meals. The following tips, which range from familiar to unique, will help you pull as much as possible out of your perishables.

www.MotherearthNews coM 23

FOTOLIA/BRENT HOFACKER; TOP: DREAMSTIME/PEPMIBA

Dry bundles of herbs for long-term culinary use (top). Give yesterday’s mashed potatoes new life by frying them up into herbed potato pancakes (bottom).

Reuse cooking oil several times by straining it after each use. Place a funnel in the mouth of a canning jar, and then line the funnel with a paper coffee filter. Slowly pour cooled oil into the funnel, and allow it to filter through and drip into the jar. Put a lid on the jar and store it for your next use. You can save the oil-soaked filter to start a fire in your fireplace or fire pit.

—Mary Ann Wall Yancey

When your hens lay a surplus of eggs, whisk them up and freeze them raw in containers with ⅛ teaspoon salt or 11⁄2 teaspoons sugar for every four beaten yolks to keep them from becoming sticky. Label each container with the number of eggs inside. The eggs will come in handy in winter, when fresh eggs are scarcer. To thaw, place the containers in the refrigerator overnight, and then use the eggs as you would fresh eggs.

—Roberta Bailey

Freeze milk that’s on the edge of turning sour in recipe-sized portions—

Beef ‘Stoup’

My wife, Gwen, makes a soup/stew—we call it “stoup”—that’s great for using vegetables that are close to turning. These ingredients are just a suggestion; you can use any vegetables you may have. Yield: enough servings for an army.

3 pounds ground beef or stew meat

1⁄4 cup white flour

3 cups whole tomatoes

8 carrots

1 bunch celery

Potatoes, squash, zucchini, corn or any other veggies on hand, about 1 cup, chopped

Beef stock or water

1 cup barley

usually a cup or half-cup—and use it for cooking. It’s even better to go ahead and sour it before freezing by adding 1 tablespoon of vinegar or lemon juice per cup, and then to treat it as buttermilk. Use it in pancakes, muffins, quick breads, and other baked goods that call for buttermilk.

Save bones and vegetable scraps in the freezer to make stock. You can also freeze bits of cooked roasts, chicken, pork, etc. After you have enough to fill your slow

cooker, start the stock by covering the food scraps with water, and then cook on low for 12 to 24 hours.

Freeze the small odds and sods of hard cheeses, such as Parmesan, cheddar, Swiss, and Gouda. When you have a bagful, thaw them and whiz them together in a food processor or heavy-duty blender along with half the cheeses’ weight in butter and a tablespoon or two of brandy. You’ll then have potted cheese spread.

—Robin Mather

I never throw out the tops of celery stalks. Instead, I dehydrate them and grind them up to use as a seasoning.

—Jessica Kaml

I chop up the outer leaves and stalks of cauliflower and use them in soups and stir-fries. —Ros Tosi

My favorite way to use leftover mashed potatoes is to make potato pancakes for breakfast. Here’s how:

Spices or dried herbs, such as basil, oregano, Greek seasoning, black pepper, thyme, or garlic powder

Brown the beef in a large stockpot over medium-high heat. Drain the excess fat, sprinkle flour over the beef, and cook, stirring, until

flour has browned. Chop your vegetables, including the whole tomatoes, and add them to the pot. Fill the pot with stock or water until the veggies and meat are covered. Bring to a boil, and then reduce heat. Add barley and spices. Simmer on low until the barley is cooked and the vegetables are soft, about 45 to 50 minutes.

—Caleb D. Regan, former editor at Grit magazine

24 MOTHER EARTH NEWS • PREMIUM GUIDE TO LIVING ON LESS

DREAMSTIME/ROBYNMAC; TOP: ISTOCK/WWING

Make friends with your freezer to keep your leftovers fresh. Label each container with its contents and the date to fend off forgetfulness.

While about a tablespoon of oil or butter is heating up in a frying pan, mix rosemary, salt, and pepper with the chilled mashed potatoes, and then shape them into patties. Dredge the potato patties in flour for a nice crust, and then fry them up into potato pancakes. I enjoy them with eggs, Brussels sprouts, and coffee.

I put cut-up chunks of stale bread in the freezer until I have about 1 pound. When I’m ready to use the pieces of bread, I fetch them out of the freezer, let them defrost a bit, and then bake them with raw eggs, vegetables, cheese and a bit of cream to create a satisfying strata. —Hannah

Kincaid

Loaded Enchiladas

This one-pan classic is perfect for incorporating all kinds of vegetable scraps and other “extras” you may have lying around. Make sure you have good tortillas and enchilada sauce, but other than that, you can put practically anything inside enchiladas and end up with a delicious meal. Here are some ingredients I’ve added and loved, most of which are optional.

Finely chopped vegetables, such as broccoli, cauliflower, squash, peppers, or potatoes

Chopped greens, such as spinach or kale

Finely diced garlic, onions, or shallots

Olive oil

Cooked beans

Diced, shredded or ground meat, such as seasoned hamburger, chicken, roast, or steak

Cooked grains, such as brown rice or millet

Salt, to taste

Herbs, such as cilantro or chives

Spices, such as cumin, chili powder, or paprika

Enchilada sauce

Enough corn tortillas to hold ingredients

I turn dry bread into breadcrumbs, or I cut it into cubes and season it with garlic, butter, and herbs for homemade croutons. —Janette

Hartman

I save the last pieces of fruit that no one wants to eat, such as the final few grapes, strawberries, or blueberries. I keep them in the freezer, and then a couple of times a year, I haul them out, put them all together in my food processor, add a little sugar and a little pectin, and voilá!—it all becomes some of the best jam you’ll ever taste. If you don’t believe me, just ask any of the recipients of my special mixed-berry jam! —Cindy

Really ripe fruit that we aren’t able to eat goes into the blender. Blend 2 cups of fruit, 1 tablespoon of sugar if needed, and 1 teaspoon of lemon or lime juice, and then put the mixture into molds and freeze for fruit popsicles. My personal favorite is 1 cup of nectarines or peaches mixed with 1 cup of strawberries. Sometimes, if I have extra pie crust, I’ll make mini-pies with the fruit, too. —Stephanie

Figg

After squeezing limes or lemons , I freeze them to later stuff into a chicken before I roast it. This imparts a citrus flavor and also helps keep the meat moist. —Sarah

Matteson

Cheese, such as cheddar, pepper jack, goat cheese, or queso fresco

In a large pan, sauté any raw ingredients in olive oil until tender. Chop cooked items—such as steamed broccoli, baked potatoes, roasted squash, or leftover meat—into small pieces and add them to the pan, along with any cooked grains. After everything is combined, season the mixture with salt, spices, and herbs to taste.

Next, pour some enchilada sauce into a baking pan large enough to hold the number of enchiladas you want to make. Coat tortillas with sauce on both sides, and then place a bit of your filling on each tortilla. Sprinkle on some grated cheese, and then roll

up the tortillas and arrange them in the pan. Pour the rest of the enchilada sauce over the top, cover the pan, and bake for 25 minutes at 350 degrees Fahrenheit. Pull out and uncover the dish, and sprinkle the top of the enchiladas with a bit more cheese. Bake them for 5 minutes more, then serve.

If you have extra filling, store it in the fridge, then eat it with a bit of cheese melted over the top sometime in the coming days.

You can do practically this same thing with lasagna. Just layer your tomato sauce, cooked lasagna noodles, a cheese/herb blend, and your anything-goes filling mixture in a pan and bake it for 30 minutes or so at 350 F, until bubbly. Or, consider adding your leftovers to a pot of noodles along with tomato sauce for a hearty spaghetti.

—Shelley Stonebrook, former editor at MOTHER EARTH NEWS

WWW.MOTHEREARTHNEWS COM 25

FOTOLIA/MONART DESIGN

I always zest my lemons, limes, and oranges before peeling, slicing, or juicing them , and then I freeze the zest. The next time I need citrus zest for any recipe, I just pull it out of the freezer.

—Trina Reynolds

I use the pulp left in my juicer to top salads or other dishes. I also use it in homemade quick breads and veggie burgers. —Lori

Bonner

Bonner

Don’t throw away the pulp from juicing fresh vegetables. Instead, add it to soups and stews to thicken and stretch them. —Anne-marie

De Waal Coetzee

Breakfast ‘Muffins’

To make these breakfast bites, you’ll need a muffin tin, but you won’t need paper liners. Think of this as a formula, not a recipe.

Any vegetables you have, such as onions, celery, green peppers, spinach, or potatoes

Butter or oil

Spices and herbs, such as basil, oregano, rosemary, cumin, or garlic powder

Grated cheese, such as provolone, mozzarella, cheddar, Swiss, Parmesan, or Asiago

Leftover meat, such as ham, bacon, ground beef, or diced chicken

2 eggs per muffin

1 tbsp milk or cream per muffin

Salt and pepper, to taste

When I make a pie, I use the pastry bits left over from cutting around the edge of the pie to make an appetizer. I scatter a bit of grated Parmesan cheese over them, and bake them at 400 F for 10 minutes. —Katherine

Britton

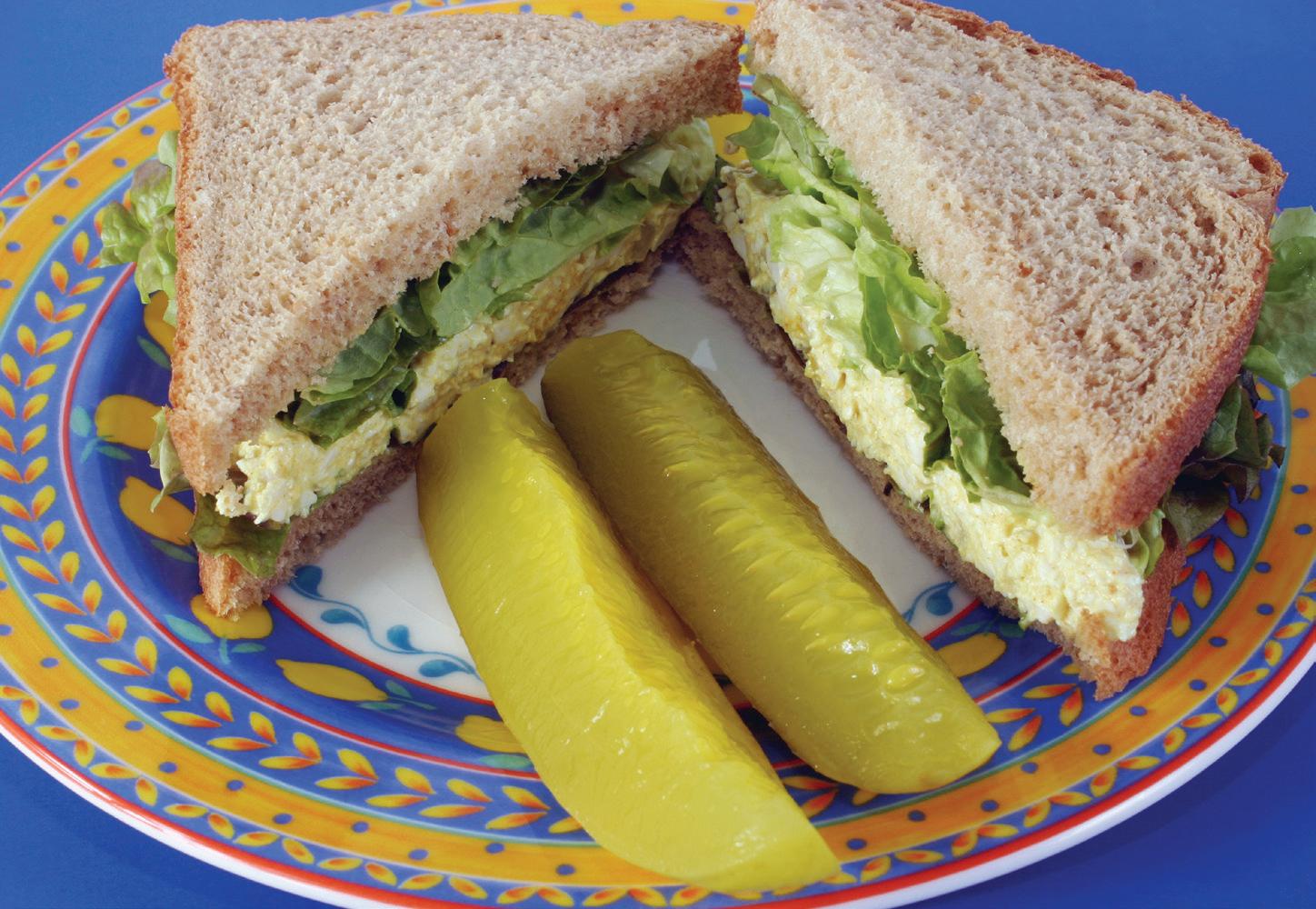

I grind up leftover roasted meat and mix it with mayonnaise and relish to make a filling for sandwiches.

—Jean Ray Weddle

Add 2 cups of leftover cooked vegetables to a food processor with an egg, 1/4 cup of flour and a tablespoon of cream. Using a small ice cream scoop,

drop the mixture onto a cookie sheet, and then place the sheet in the fridge to chill for 30 minutes. Then, place leftover meat from a pot roast in a saucepan with your favorite barbecue sauce, and simmer it on medium-low for 30 minutes. Finally, remove the balls and deep-fry them. Put the meat on bread for a barbecue sandwich, and enjoy it along with the fried vegetable balls.

—Xris Hess

We steam a big batch of rice and keep it in the refrigerator to use later in all kinds of quick dishes throughout the week—in burritos, with red beans, and as fried rice. Our favorite version of fried rice uses up all the standard neglected vegetables in the crisper—especially mushrooms, bell peppers, and the butts of onions—and sometimes we throw in leftover sausage from the night before. For extra protein, we’ll add an egg. We drop all the ingredients into a large skillet, fry them with sesame oil and toasted sesame seeds, and serve with soy sauce on the side. —Rebecca

Martin

Preheat your oven to 350 F. Cook the vegetables until tender in a skillet with some butter or oil, seasoning them with spices and herbs, to taste.

Butter each cup of the muffin tin, and put about 2 tablespoons of grated cheese into the bottom of each one. Add about 1/4 cup of sautéed vegetables. If you’re using leftover meat, add it now.

Beat the eggs with the milk or cream, if using, and pour the mixture into each cup, to about a half-inch from the top. Season with salt and pepper. Sprinkle more grated cheese on top. Slide the tin into the oven and bake until the egg is cooked and the cheese is nicely browned, 10 to 15 minutes. These breakfast muffins will keep for a week in the fridge.

—Robin Mather, former editor at MOTHER EARTH NEWS

26 MOTHER EARTH NEWS • PREMIUM GUIDE TO LIVING ON LESS

FOTOLIA/BEORNBJORN; TOP LEFT: DREAMSTIME/LEPAS; TOP RIGHT: DREAMSTIME/ISABEL POULIN

Be frugal with your fruit! Zest your lemons before use (left) and shape aging fruit into popsicles (right).

TRYING TO LIVE WITH LESS?

TWO-WHEEL TRACTORS

WHY BUY A SEPARATE ENGINE FOR EACH SEASONAL OUTDOOR TASK?

LESS STORAGE SPACE WITH A SINGLE POWER UNIT

LESS SOIL COMPACTION AND MORE MANEUVERABILITY

ONE POWER UNIT.

LESS TIME MAINTAINING ENGINES AND MORE TIME ENJOYING YOUR PROPERTY

DOZENS OF APPLICATIONS.

TWO-WHEEL TRACTORS

TWO-WHEEL TRACTORS

HOMEMADE BROTH & STOCK

Glean nutrients and flavor from bones and scraps by simmering and seasoning them.

By Andrea Chesman

Nothing beats the convenience of having homemade broth and stock on hand in your kitchen. Homemade broths and stocks taste better than canned broths, bouillon cubes and pastes, and even expensive boxed broths. In addition, you’ll reduce your kitchen waste if you extract the flavor that remains in bones and vegetable peelings after the other parts are consumed.

But what do you call the simmering mixture in your pot? Is it broth, or is it stock? The two terms are often used interchangeably, and definitions do vary, so it depends on who you ask. But, in a nutshell, stock is the gelatinous result of cooking vegetables and bones in unseasoned water for several hours to extract flavor, while broth is made out of vegetables and meat simmered in a seasoned liquid for a shorter

Poultry Stock

period of time. Either one can serve as a foundation for other dishes, but because broth is typically seasoned, it’s often consumed on its own, while stock is the perfect rich-tasting base onto which you can layer other flavors.

The two basic types of stock are white and brown. White stocks are made with aromatic vegetables and bones (usually raw or roasted poultry or fish bones) that are simmered for hours. Brown stocks are made by roasting vegetables and bones first, and then boiling them with aromatic vegetables. This technique most often includes beef and pork bones, but poultry bones can be turned into brown stock too. Lamb and goat bones can also be used, but not everyone appreciates the resulting flavor.

To make your own stock, select a mixture of jointed bones and meaty bones. The jointed bones add collagen for mouthfeel, and the meaty

Use either the raw bones of poultry or the carcasses from a roast. Chicken feet make a particularly rich-tasting stock, with plentiful gelatin. You can also use this method to make ham stock, but rather than save up the bones in the freezer and risk freezer burn, halve the recipe and make the stock soon after enjoying the ham. Yield: about 7 quarts.

Directions: Combine the bones, water, and all the vegetables in a large stockpot. Bring to a boil, then reduce to a simmer. Skim off any foam that emerges on the surface until no more appears. Partially cover the pot, and simmer over low heat for 5 to 8 hours. Strain the stock by pouring it through a strainer lined with cheesecloth into another bowl or pot, and discard all the solids.

Refrigerate the stock for several hours, until a hardened layer of fat congeals on top and can be lifted off. Refrigerate and use within 4 days, freeze for up to 6 months, or pressure can in quart jars for 25 minutes.

bones add flavor. If you’re making a poultry stock, nothing beats chicken feet for adding richness—and you can’t make much else with them. I generally roast my poultry by spatchcocking or butterflying, meaning cutting out the backbone and then flattening the breast. This significantly reduces the roasting time and provides me the backbones for making stock; backbones are almost as good as feet for making a flavorful stock.

You’ll need a large stockpot or saucepan for making stock. If you’re making a brown stock, you’ll also need a couple of large rimmed sheet pans or roasting pans. The vegetables are a suggestion only; use what you have on hand, but avoid brassicas (such as broccoli and cabbages), which add an unpleasant flavor when cooked at length. I save onion peels, parsley stems, and leek greens in the freezer for this purpose. You can also save up mushroom stems and gills.

Skim the fat off the top of the meat and poultry stocks, and save it to cook with later. It’s a great cooking medium that adds flavor and

Ingredients

• 7 pounds raw chicken or turkey backs, wing tips, or feet, or the carcasses of roasted chickens or a turkey

• 8 quarts water

• 1 pound fresh or frozen vegetable trimmings (onion peels, celery tops, leek tops, parsley stems)

• 1 bunch parsley

• 2 onions, quartered

• 2 celery roots, peeled and chopped, or the top half of a bunch of celery

P AGE 28: A DOBE S TOCK /F OM A WWW.MOTHEREARTHNEWS COM 29

excellent browning qualities to any dish. The fat is perishable, though, so use it within a week or freeze it.

Stock can be the base of any quick soup or stew. Chicken stock, kale, and sausage with white beans is one of my family’s favorite dishes.

Stocks can also be used as braising liquid for stews and vegetables, as well

as cooking liquid for grain dishes, risottos, and pilafs.

Stocks can also extend gravies and sauces, and will punch up the flavor rather than dilute it.

Once you have a supply of stock on hand, your weeknight dinners will be quicker and easier to make, and more enjoyable to eat.

Andrea Chesman cooks, writes, and teaches in Vermont. She’s the author of Serving Up the Harvest, The Pickled Pantry, and The Backyard Homestead Book of Kitchen Know-How. You can find all three at www.motherearthnews. com/store.

Mushroom Broth

Ingredients

• 3 tablespoons olive oil

Many vegetable broths take on too much flavor from the veggies, tasting too sweetly of carrots or tomatoes. This broth tastes distinctively of mushrooms and can be used in any dish that calls for chicken or beef stock or broth. It also makes an excellent base for a vegetarian gravy. You can use any variety of mushrooms. Yield: about 5 quarts.

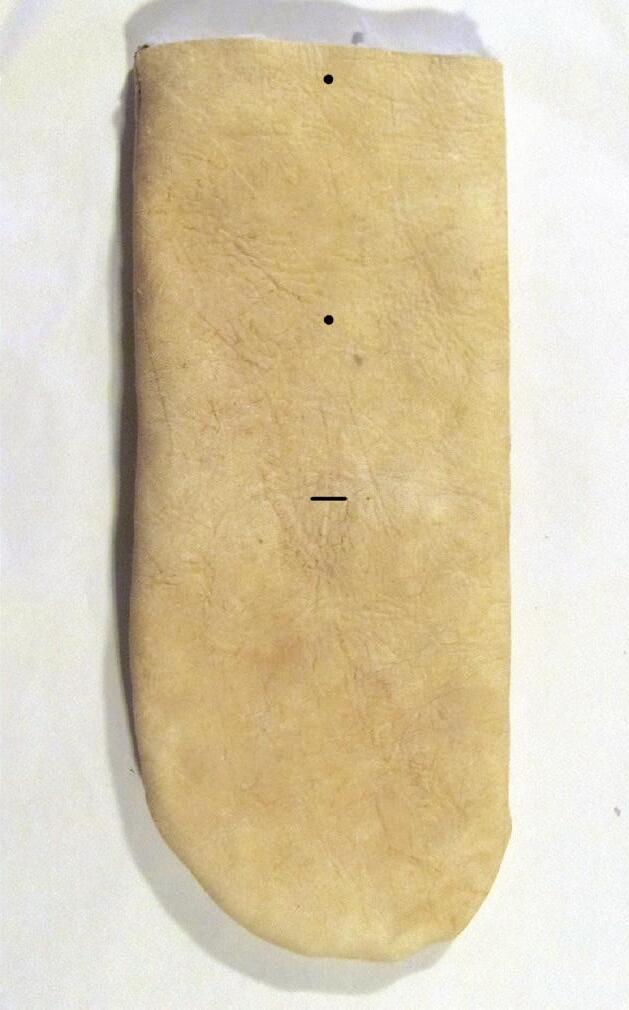

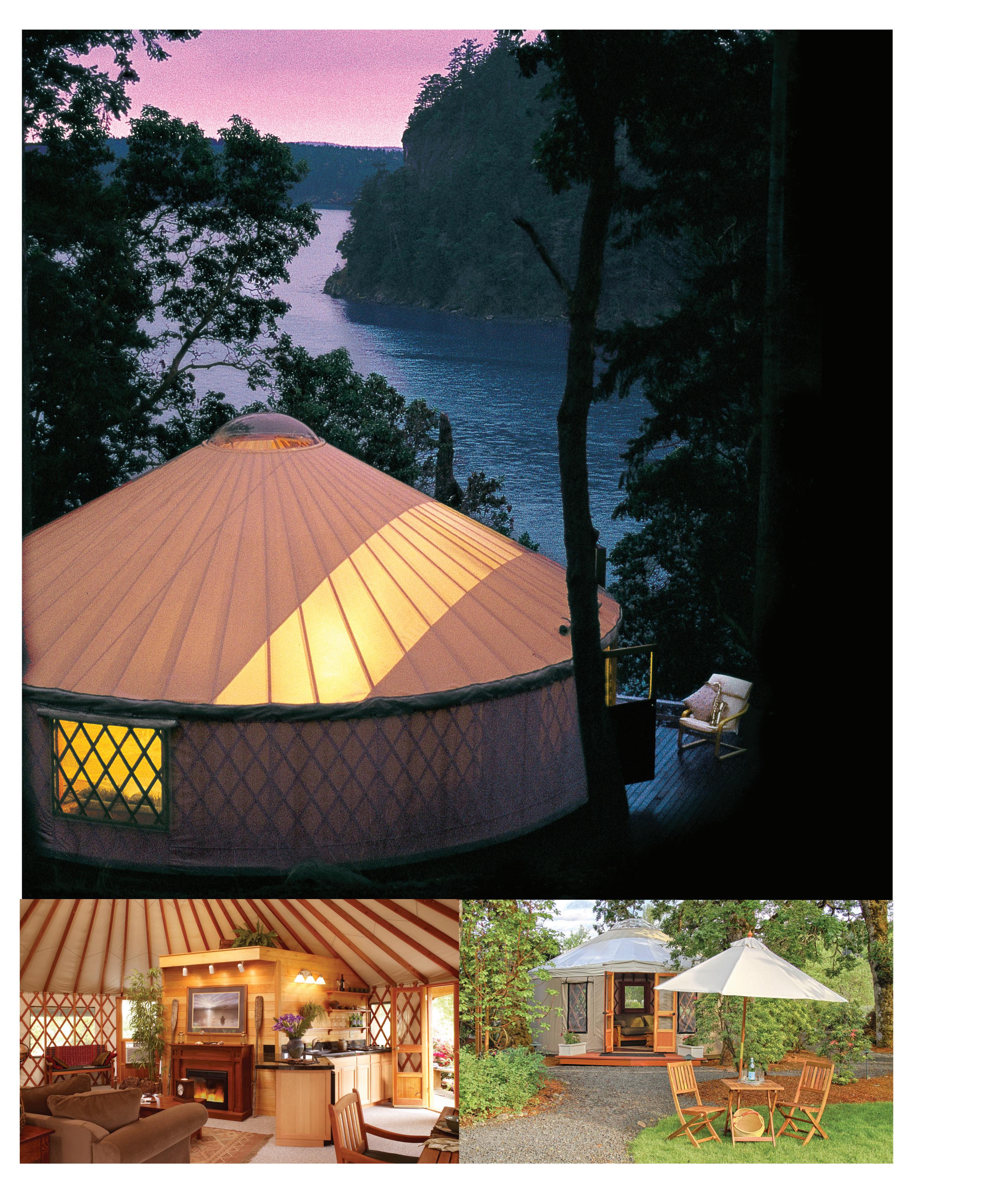

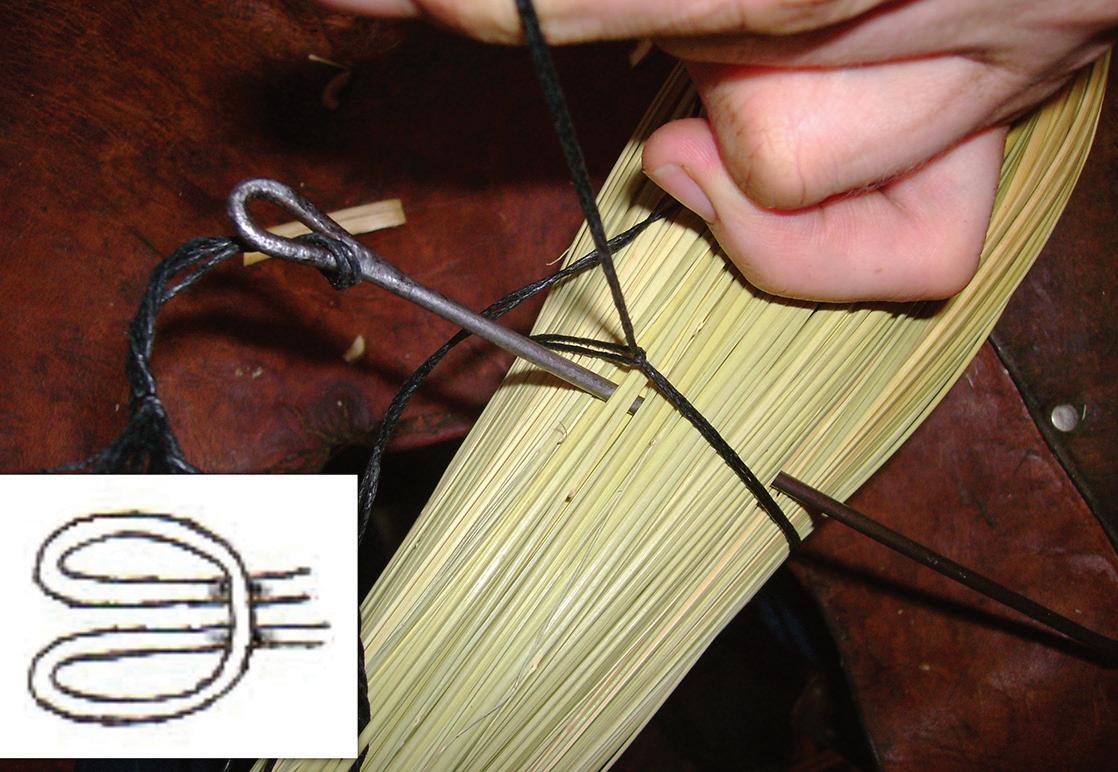

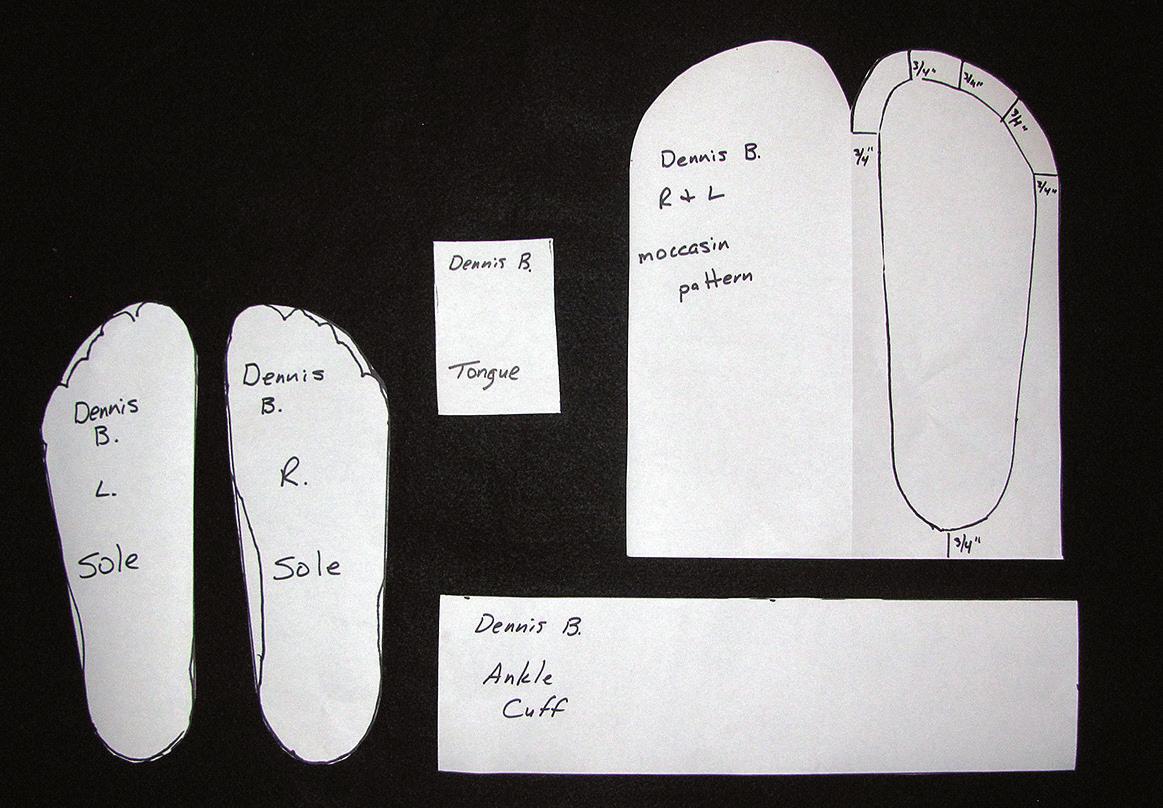

Directions: Heat the oil in a large stockpot over medium-high heat. Add the carrot, onions, celery root, and garlic, and sauté until they soften, about 8 minutes. Add the mushrooms and cook, stirring occasionally, until the mushrooms begin to give up their liquid and their volume reduces significantly, about 15 minutes.