In 2001 I completed my Encyclopedia of Antique Tools

PUBLISHER/EDITORIAL DIRECTOR

Bryan Welch

Fto say that most of today’s mystery tools weren’t a mystery at all in their heyday. The plain fact is that the crafts or endeavors behind these mysteries no longer exist. In our age of plastics and printed circuit boards, it is difficult to relate to mechanical inventions for which the technology no longer exists.

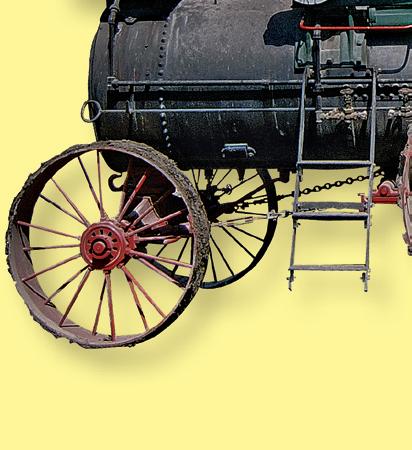

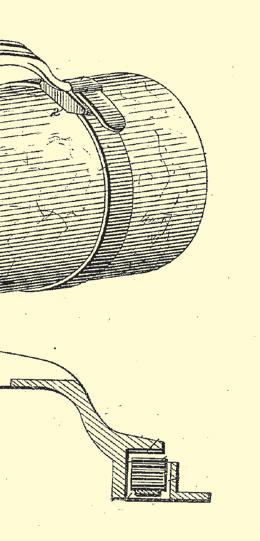

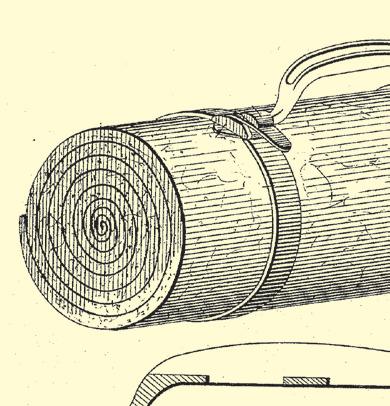

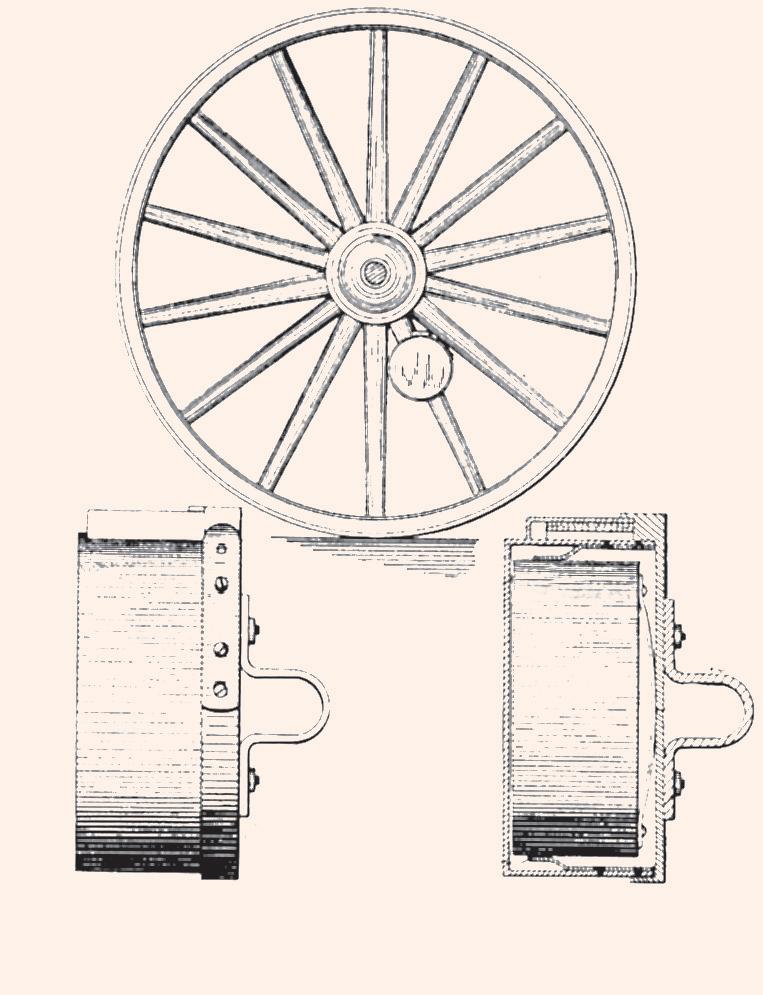

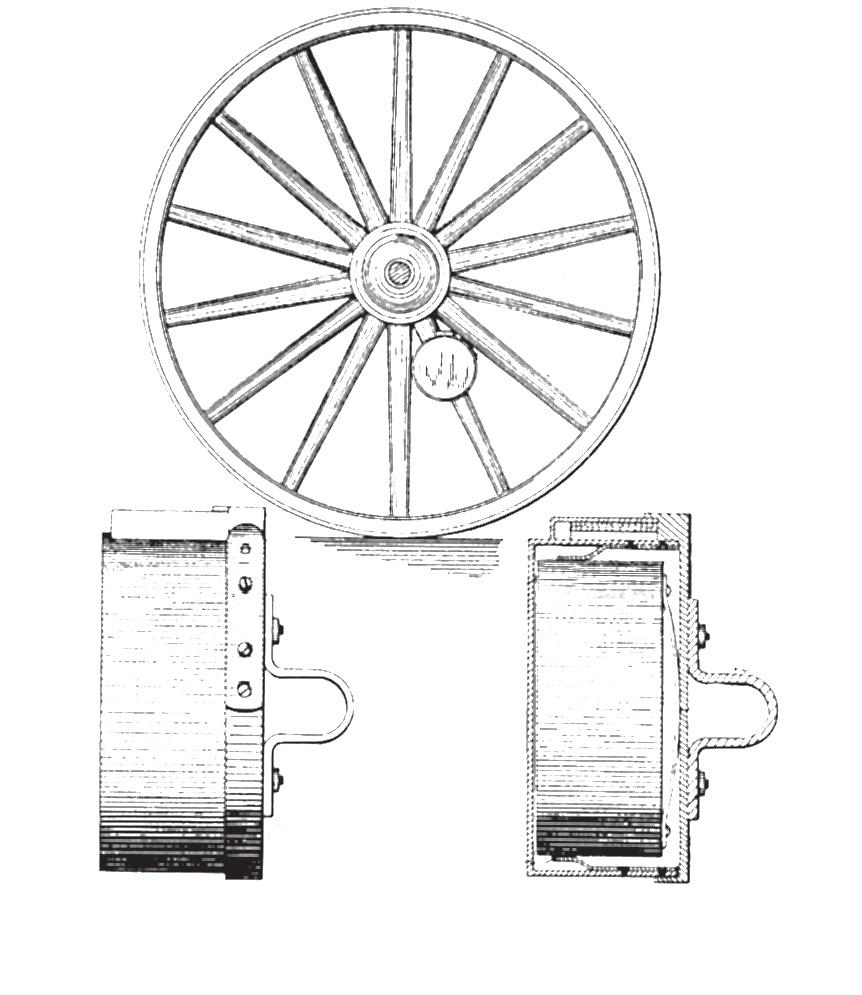

Although a post drill, for instance, is easy to identify, a beading tool or a wheelwright’s traveler can present a problem for many collectors. All are featured in this book. A beading tool was used to turn down the ends of boiler tubes. That was especially important on the firebox end, in order to keep the white hot fire from actually burning the ends of the tubes. A wheel traveler was used to measure the periphery of a wooden wheel. Then the iron wagon tire was measured. It was made a bit smaller, and was then heated so it would expand. At the proper moment it was dropped over the wooden wheel, and water was poured on to keep from damaging the wood. The same principle was used for mounting hardened steel tires to locomotive wheels. In this instance, the parts were carefully machined, the tire was heated so it would expand, and then dropped into place over the wheel. The eerie creaking sounds as the tire shrinks into place over the wheel cannot be described with accuracy.

& Machinery. Having spent a lifetime among a family of farmers, blacksmiths, and machinists, I also collected old literature on antique tools for decades. The first problem in compiling that book was in selecting pictures to use. As collectors already know, there are thousands and thousands of tools and gadgets; a great many of them remain unidentified. As noted above, the application for which they were intended no longer exists. In many instances that old cast iron thingamajig that worked so well has been replaced with some pitiable plastic device with an expected working life of weeks or months, compared to the old timer that lasted for many decades.

My book American Farm Implements has gone through two editions, and American Industrial Machinery is still available. The major lesson of all these titles is that the field of early mechanical technology is so great, that for all these books, I still know very little. I have numerous tools and gadgets that I’ve never been able to identify! So, my compliments to Farm Collector for assembling this little book. Perhaps it will be the first of several related titles pertaining to the history of many different tools, devices and thingamajigs!

C.H. WendelA word from the editor of Farm Collector

Photos and text in this publication are purely homegrown: All come from the pages of Farm Collector, a magazine for collectors of vintage farm equipment, in which What Is It is a popular monthly feature. Every issue, readers contribute photos of items for the section; others pitch in to identify the items, often sharing memories of personal experience with long forgotten tools. We’ve culled this selection from the magazine’s archives built over the past 12 years. Can you identify these tools without looking at the descriptions?

We hope you enjoy this detour from modern life and times into a simpler era when inventors crafted solutions that required neither chips nor circuit boards but rather plain old American ingenuity. And now, on with the show!

Leslie McManusEDITORIAL

Richard Backus, Editor in Chief

Leslie McManus, Editor

Christian Williams, Special Issue Editor

Beth Beavers, Assistant Editor

Tess Wilson, Editorial Intern

ART/PREPRESS

Karen Rooman, Art Director

Art/Prepress Staff:

Terry Algarin, Michelle Galins, Debbie Glessner, Amanda Lucero, Marci O’Brien, Kirsten Martinez, Nate Skow

ADVERTISING

Rod Peterson, Sales Manager

Terri Keitel, Advertising Account Executive

Anita Fisher, Advertising Coordinator

Contact: tkeitel@ogdenpubs.com (800) 678-5779

WEBSITE

Christian Williams, FarmCollector.com Editor

John Rockhold, Managing Editor/Online

Bill Uhler, General Manager

Cherilyn Olmsted, Marketing and Circulation Director

Bob Legault, Sales Director

Carolyn Lang, Group Art Director

Matthew Stallbaumer, Assistant Group Art Director

Bob Cucciniello, Circulation/Production Manager

Farm Collector subscriptions: 12 monthly issues, $34.95/year U.S. (periodical class mail). Call toll free: (800) 678-4883; or send check or credit card details. U.S. funds only.

Please see our website, www.FarmCollector. com, for writer’s guidelines and information on submission of material for regular issues. Ogden Publications Inc. cannot be held responsible for unsolicited manuscripts, photographs, illustrations or other materials.

Farm Collector ISSN 1522-3523 (publication no. 017086) is published monthly by Ogden Publications Inc., 1503 S.W. 42nd St., Topeka, KS 66609.

Farm Collector does not recommend, approve or endorse the products and/or services offered by companies advertising in the magazine or Web site. Nor does Farm Collector evaluate the advertisers’ claims in any way. You should use your own judgment and evaluate products and services carefully before deciding to purchase.

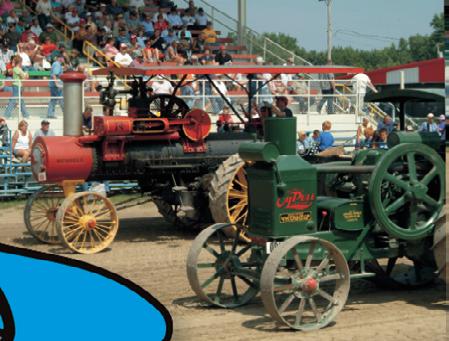

Before gas tractors plowed the fields, steam traction engines ruled the prairie. Now, the glory days of steam farming live on through the words of the men and women who experienced them firsthand.

Twelve poems, originally submitted to Iron-Men Album back in the 1950s, have been unearthed and set to original music by folk musician and Farm Collector associate editor Christian Williams on this new audio CD. To give the album an old-time American feel, Williams used instruments unique to American folk music, including banjo, washtub bass, steel resonator guitar and autoharp. Enjoy this first-hand account of early American farming, and let the words and music take you back to a time when steam was king.

Twelve folk and

As a category, “field and crop” spans the territory from a John Deere wrench to a threshing machine.

22 Farmhouse—The heart of the homestead

Modern conveniences tend to make us complacent and ask, “How did the early farm wife do it?”

42 Livestock—Keeping the herd in check

The stockman of yesteryear was equipped with an enormous selection of tools with which he managed his herd and flock.

Barn/Shop—Tools

To a farmer, the barn and farm shop are the rough equivalent of a businessman’s desk and file cabinet.

Collectors invariably encounter pieces that turn out to be related to early farm life but have no specific farm function.

When it comes to antique tools, it’s not surprising that some remain stubbornly unidentifiable.

The history of farm antiques is often lost to the mists of time – but a patent search can help clear the fog.

Publications and collector organizations offer uniquely focused information on specific brands and products.

As a category, “field and crop” spans the territory from a John Deere wrench to a threshing machine. Tractors and implements were often equipped with tools unique to the device: their own toolboxes, oilcans and attachments like discs, blades, spikes, coulters, teeth, hoes, runners, markers and rollers. The machine itself may not have survived to modern day, but the small components turn up with some regularity.

Perhaps the biggest niche within this category is that of antique wrenches. With nearly 800 documented manufacturers of wrenches in the U.S. alone, the field is as vast as the prairie. Subtle variations in castings and lettering create an incalculable multiplier effect.

The wrench collector community is active and well informed. Fine resources exist among the Missouri Valley Wrench Club, Mid-West Tool Collectors Assn., www.wrenchingnews.com and a comprehensive book by collector P.T. Rathbone, The History of Old Time Farm Implement Companies and the Wrenches They Issued (see the Resources guide for more information.) Fence tools represent another significant segment of this category. What was more common on a farm than fence, and what fence didn’t require periodic repair? Tools to build and repair fencing were considered essential. A century ago, fence-making machinery was commonly available for on-farm use. More recently, galvanized steel wire fence replaced those devices. The category includes wire

tighteners/stretchers, cutters and post hole diggers.

In sheer volume, corn-related tools and collectibles are a massive category in their own right. More than any other farm crop, corn has generated an enormous range of collectibles, from check-wire planters down to lapel pins. The niche includes signs, posters, seed sacks, husking pegs, hooks and gloves, shellers of every size and description, grinders, hand planters and dealer promotional items running the gamut from matchbooks to ball caps. Members of the Corn Items Collectors Assn. are very knowledgeable and helpful in tracking information. (See the Resources guide for contact information.)

As in every collectible category imaginable, fakes are an inevitable part of the landscape. While the vast majority of collectors and dealers operate with integrity scoundrels do exist. Experienced collectors recognize red flags. If the supply of any given item seems surprisingly large – such as a pail full of identical antique wrenches all in the same, very nice condition – think twice before buying. And beware of patinas that seem too perfect. Almost any finish from rust to satin can be easily created and applied. About the only thing that can’t be easily re-created is wear. In general, it’s best to know the people you’re doing business with.

Tools in this category are becoming harder to find but still turn up with some regularity at swap meets, flea markets, auctions, antique malls and even garage sales. You may have to buy a box full to get the one piece you want, or you may have to take a leap of faith and buy an item on little more than a hunch. Complex items may be missing parts; look carefully through nearby boxes and piles to see if the piece you need got mixed in with other items.

3.

3.

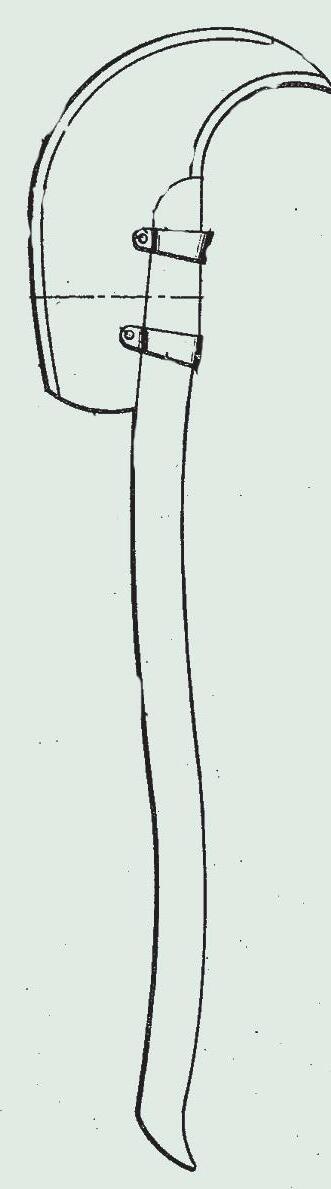

“I’m 73 years old and was raised on a farm in the Tidewater region of Virginia from infancy until I went off to college,” one reader says. “Over the years, I used this exact same tool. It was used primarily to clear heavy brush on ditch banks and hedgerows.” Another reader notes that “you need a weak brain and a strong back to use one.”

Patent 1,030,429: Brush ax. Patent granted to J.T. Reeves, Grant, Okla., June 25, 1912.

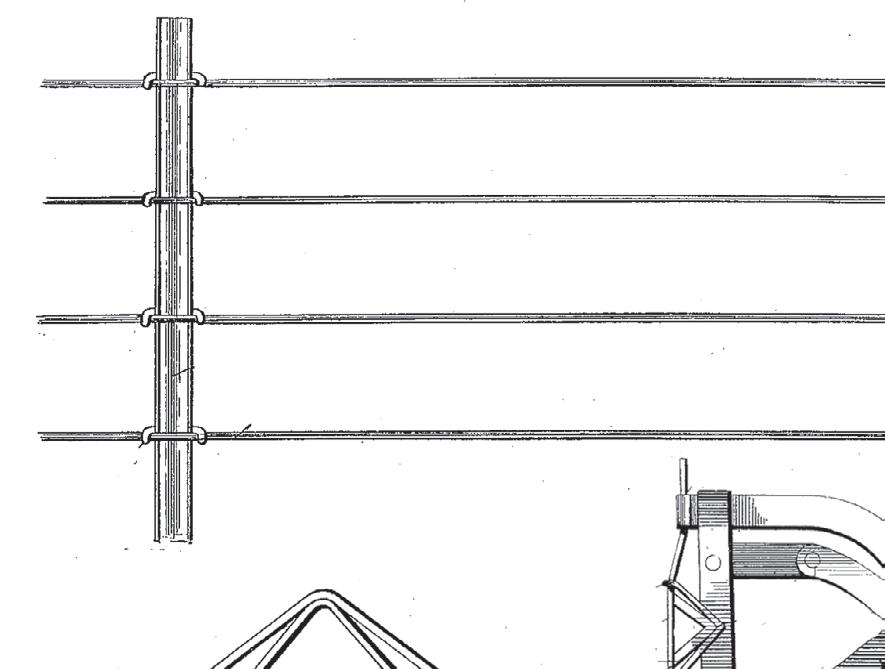

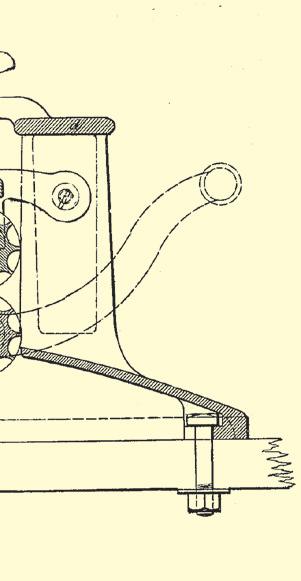

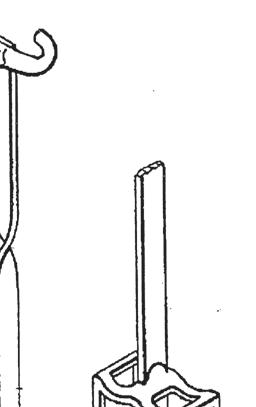

Patent 639,521: Machine for attaching pickets to fence wires. Patent granted to Jerome Carpenter, Livonia Station, N.Y., Dec. 19, 1899. This is not the exact patent but it illustrates a similar piece.

. . . you need a weak brain and a strong back to use one.”

Conway Springs, Kan., “The wire-engaging arms or bars, which are arranged to engage a fence-wire at opposite sides of the post, are provided at their lower edges with notches or teeth to receive the fence-wire.”

Used to take up slack in a single wire of a fence by twisting a knot in a loose wire. “Notice that the patent was issued on New Year’s Eve, which fell on a Tuesday in 1907,” one reader says. “Almost all patents were issued on a Tuesday; there were very few exceptions to that rule. Would the people that work in the patent office today consider working on New Year’s Eve?”

Patent 658,335: Wire tightener. Patent granted to Samuel Beal, Conway Springs, Kan., Sept. 25, 1900.

Patent 874,934: Fence wire tightener. Patent granted to Henry Broome and Charles J. Bowlus, Springfield, Ohio, Dec. 31, 1907.

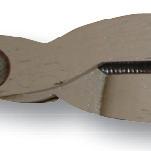

“The fork end was used to remove staples by sliding the forks around the staple and under the wire and prying the staple out,” one reader writes. “The notch in the side by the hinge was used to cut wire, and the flat area by the hinge was used as a hammer to drive in a staple when the handles were closed. One tool to carry for quick fence repairs.”

As shown in the patent drawing, horizontal line wires were put in place and stretched tight. Then the stay (vertical) wires were installed. The device was used to build fences of any size.

Patent 640,598: Combination tool. Patent granted to Daniel Stetler, Medford, Okla., Jan. 2, 1900.

Patent 606,266: Fence stay weaving device. Patent granted to C. Baxter and A. Schrader, Waukesha, Wis., June 28, 1898.

About

We can thank early European settlers for picket fences. An iconic boundary for American homes dating back to Colonial times, the classic picket fence evolved from medieval boundaries constructed of wooden planks and stakes.

Overall length is 23-1/2 inches and the two pieces that hinge out are 11 inches. The small piece in the center is also hinged. The only markings on it are “Patent applied for.”

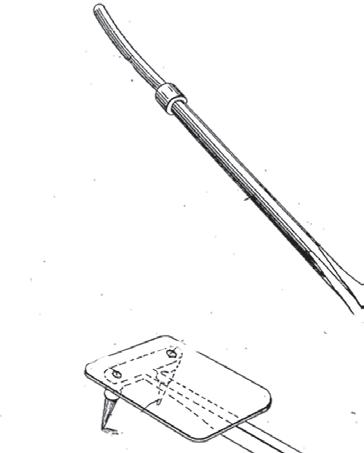

Wire-splicing device for use in fence repair. The tool is shown veritcal, but would be horizontal in actual use.

Patent 1,322,136: Wire-splicing device for broken fence wires. Patent granted to Emil Sahler, Minneapolis, Nov. 18, 1919. This is similar to the tool shown above and illustrates how the device was used.

This

Made of cast iron; measures 6-by-15 inches; concave on the back. Stamped on the front “Standard Fence Never Creep.”

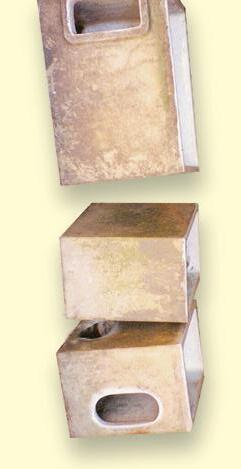

Patent 1,384,825: Anchor. Patent granted to Albert Chance, Centralia, Mo., July 19, 1921.

This land anchor was used for various purposes, such as guying telephone and other poles, smokestacks, etc.

“This item is part of an anchoring system developed by the A.B. Chance Co.,” one reader explains. “The other part would be a rod with a pointed ball on one end and an eye for connecting a wire or cable to the other end. You’d dig a posthole, preferably slanted away from the direction of strain. The pointed rod was driven into the hole, angled so it intercepted the posthole at the desired depth, and the keyhole of the anchor was inserted onto the rod and dropped down so the ball on the end of the rod was secure from backing out. Backfill the hole; job completed. Some interesting history about this item can be found by Googling ‘A.B. Chance Co.,’ ‘link Chance anchoring systems,’ and ‘history of earth anchoring.’”

Fowler cultivator built by the Harriman (Tenn.) Plow Co. One reader says this piece was also used to harvest dry beans. Another reader notes that the unit pictured cut weeds at the root to stop growth and was adjustable in several ways.

Harriman manufactured the piece under varied names for sale by various hardware stores and short-line farm implement companies. Another reader says “HPW” was stamped on many Harriman products. “H” was put on all products built in Harriman. In 1940 Harriman bought the IHC plant in Chattanooga, Tenn. In 1957 the plant was closed, and later that year was destroyed by fire.

A grain band cutter designed to cut wire or twine ties from bundles of wheat, oats or barley, thereby keeping the wire out of the threshing machine.

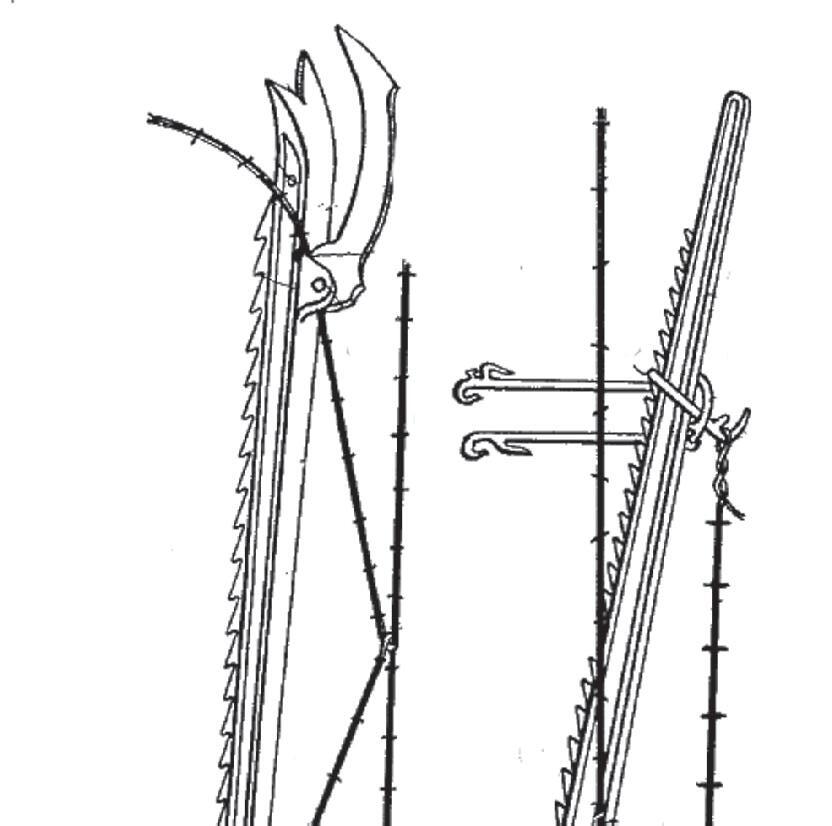

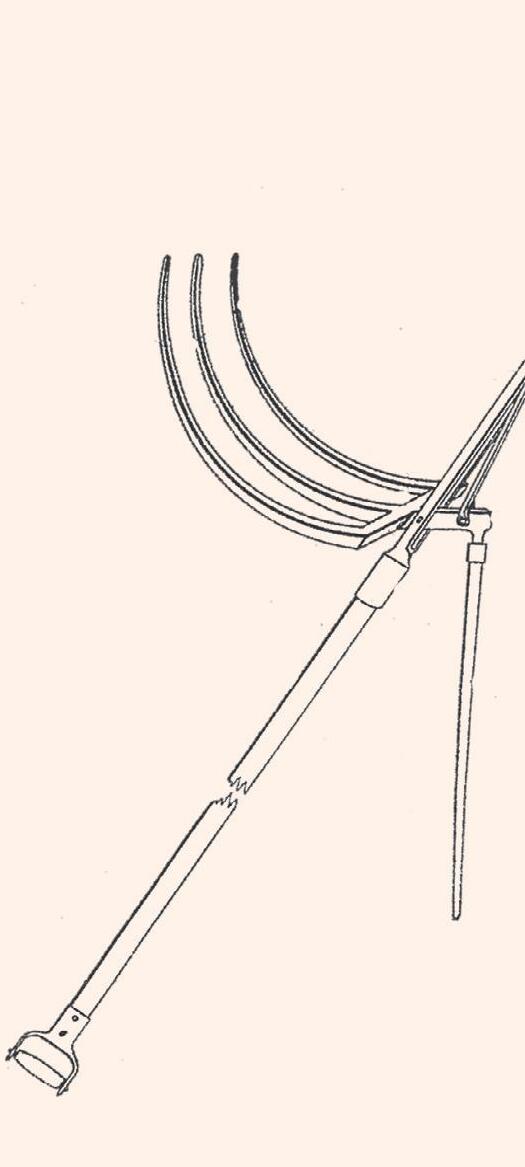

Patent 533,787: Strawyberry-runner cutter. Patent granted to Charles Carter, Spring Arbor, Mich., Feb. 5, 1895.

This device was used to bundle grasses, grains and other field crops. According to a 1914 patent awarded to George Rheem of Helena, Mont., this item, “Is to produce novel means for clamping the stalks of vegetation near the butt ends thereof and also at the neck portions thereof just back of the heads, so that the stalks may be tied together in bundles by ribbon or ornamental fastenings, or in any other appropriate way.”

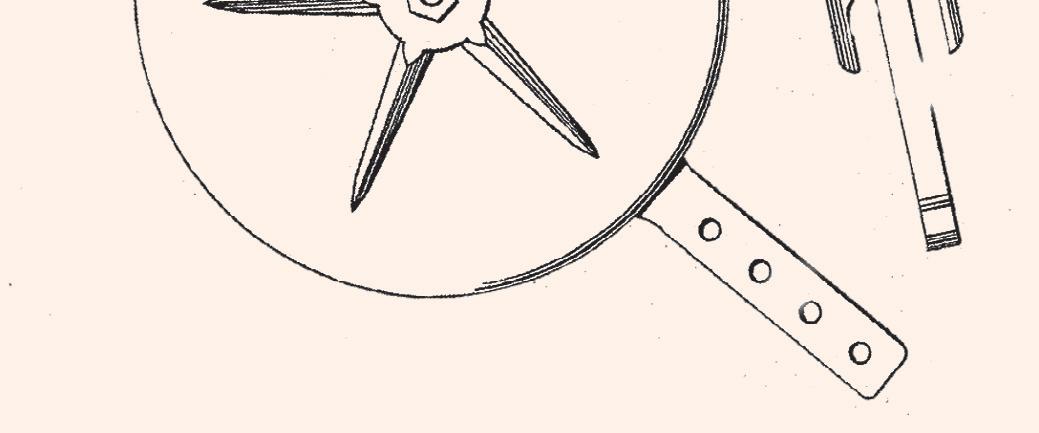

A Feb. 5, 1895 patent and drawing describes it as a device for “effectually and rapidly severing the runners from strawberry plants.” By depressing the handle downward, knives gather the runners and sever them in a guillotinelike action. A lift on the handle draws the tool upward and returns the knives to their original position.

Patent 1,097,364: Bundling device. Patent granted to George Rheem, Helena, Mont., May 19, 1914.

This stump hook was used when clearing land.

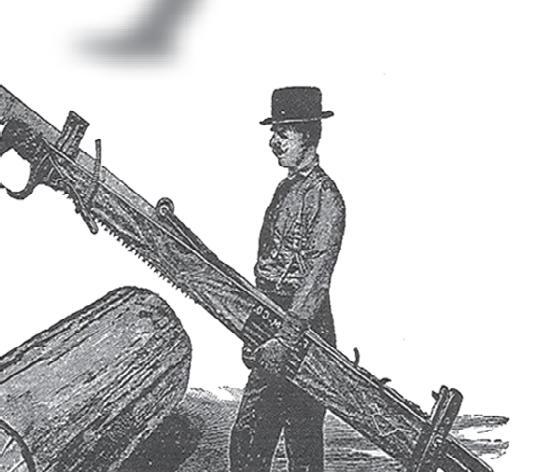

“If the stump was tall, the pulling cable could be wrapped around the stump, making for an easy pull,” one reader says. “However, if the stump was low, the cable couldn’t be wrapped and the pulling crew would use this type of hook.” The hooks were often used in conjunction with a horse-powered windlass (winch) anchored to a large tree, another reader says. A heavy steel cable attached the “plow” shown to the windlass.

In their book, The Grain Harvesters, Graeme Quick and Wesley Buchele describe the threshing sledge as possibly being the oldest farm implement. It was pulled (usually by oxen and with a child or two riding on it for added weight) round and round over a circular band of unthreshed grain.

Quick and

The Romans gave it the name tribulum from which the word tribulation is derived. The threshing sledge is referred to in Isaiah 41:15.”

A typical stump pulling set-up, with a horse-powered windlass pulling a tall stump. A stump hook could be used for short stumps. Illustration from 1906 Milne Mfg. Co. (Monmouth, Ill.) catalog. Milne manufactured grub and stump machines and other appliances for clearing timber land.

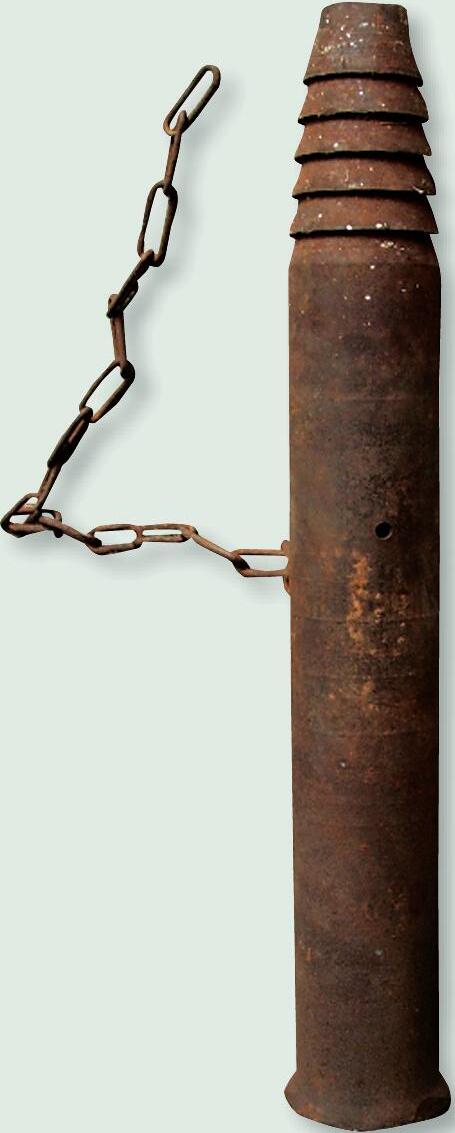

“Pound it into the end of the log with a sledge. Insert 6 inches of fuse. Light it and get out of the way,” a reader says. “It really works. I still have one and use it on the Fourth of July to make a loud noise.” Another reader adds that “an old timer told me to cut the chain off because if it comes flying out of the log, the chain makes it whip around.”

“ Pound it into the end of the log with a sledge. Insert 6 inches of fuse. Light it and get out of the way. It really works. I still have one and use it on the Fourth of July to make a loud noise.”

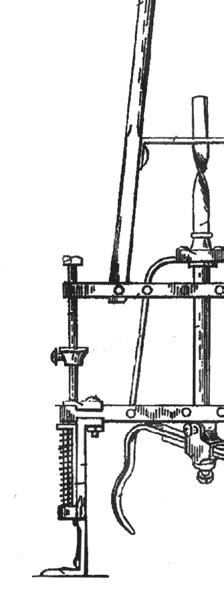

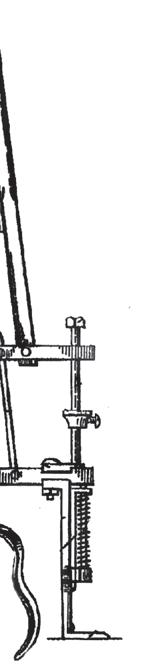

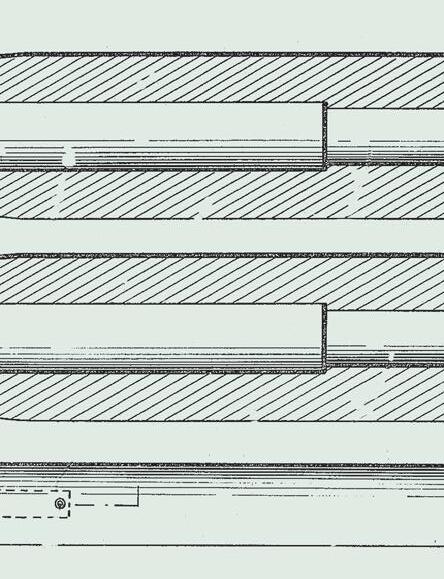

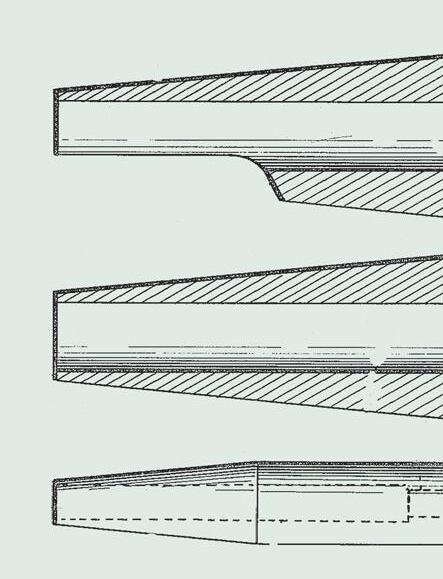

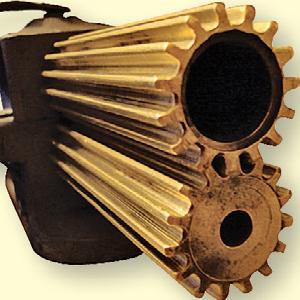

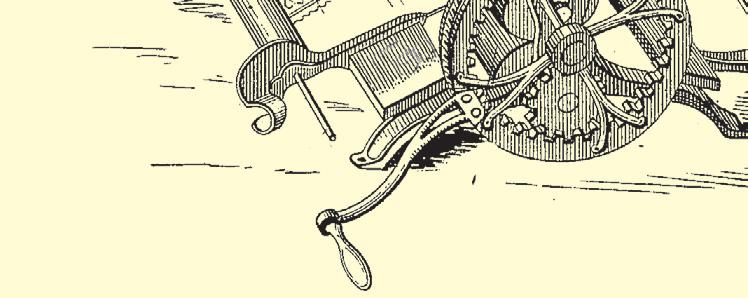

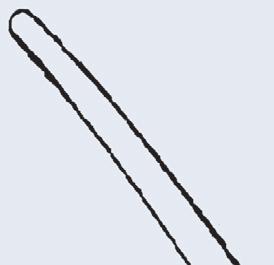

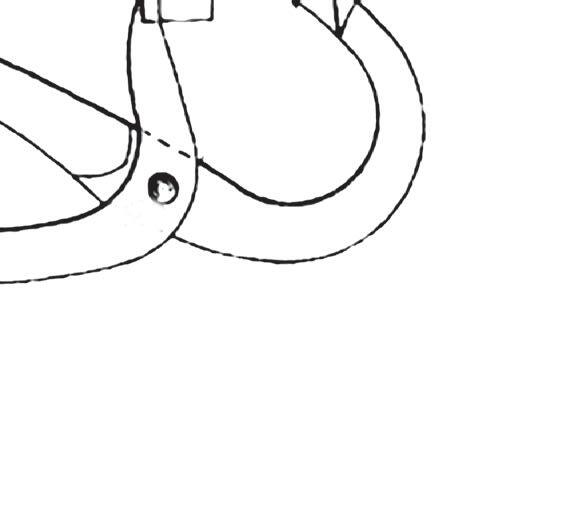

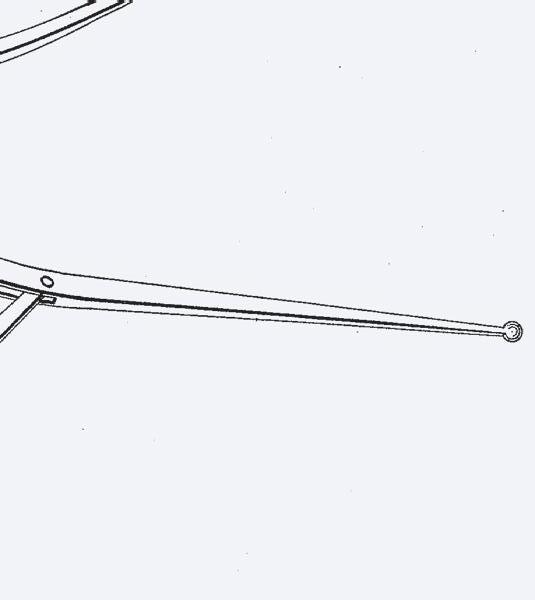

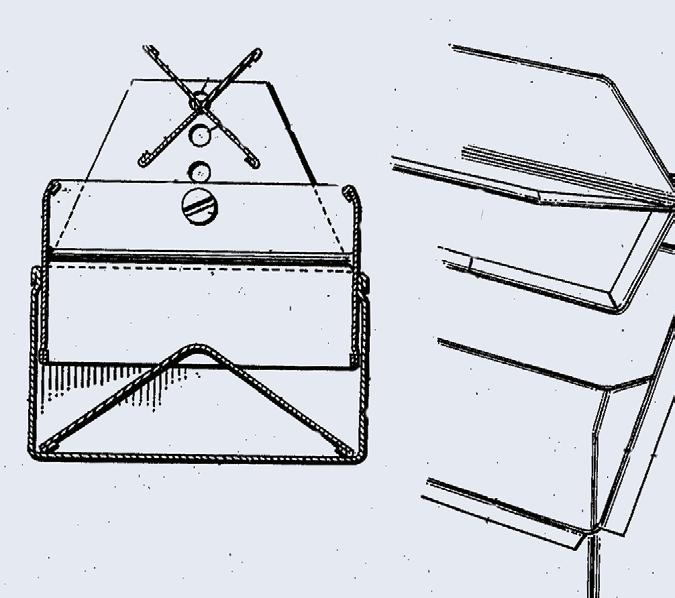

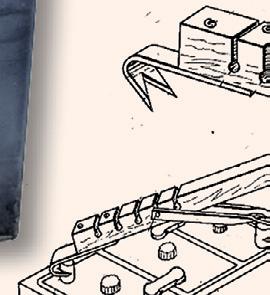

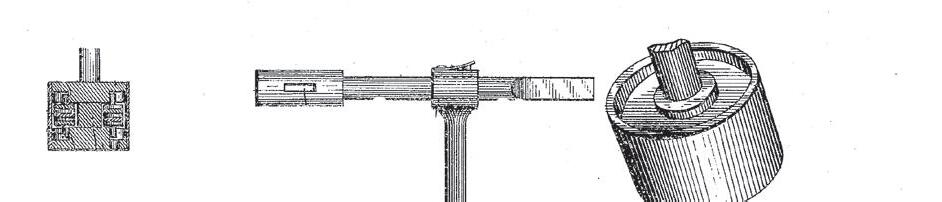

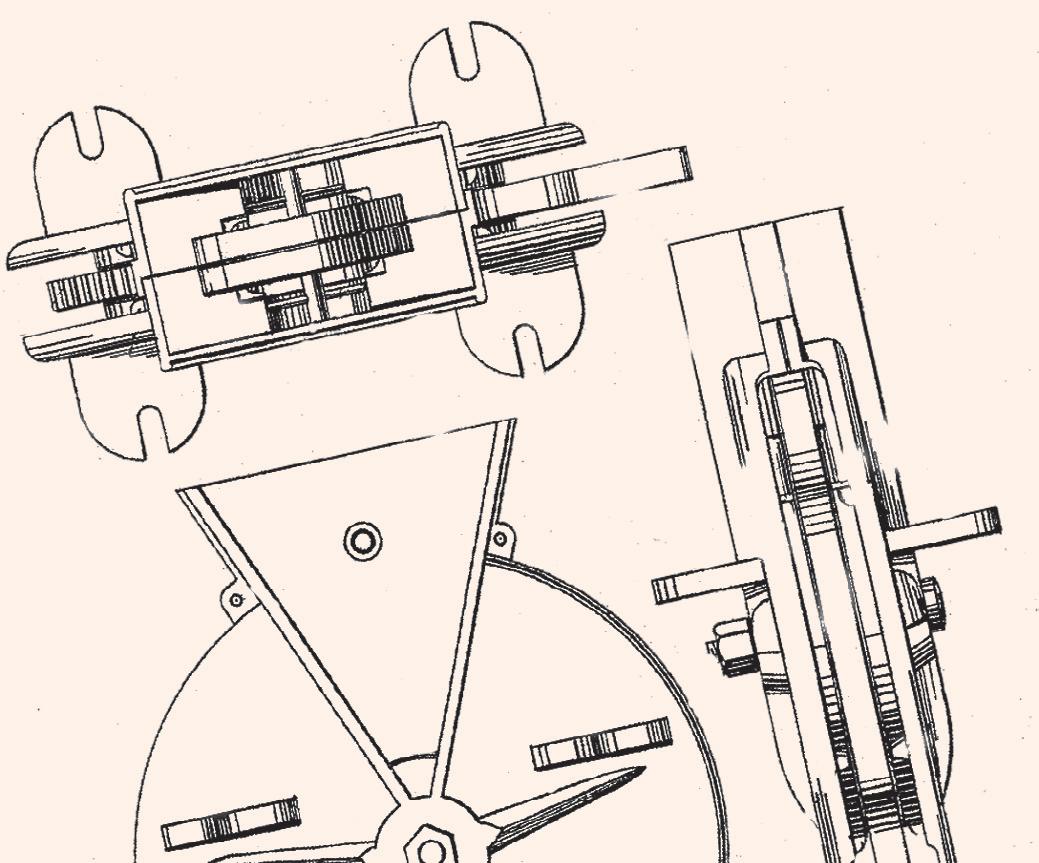

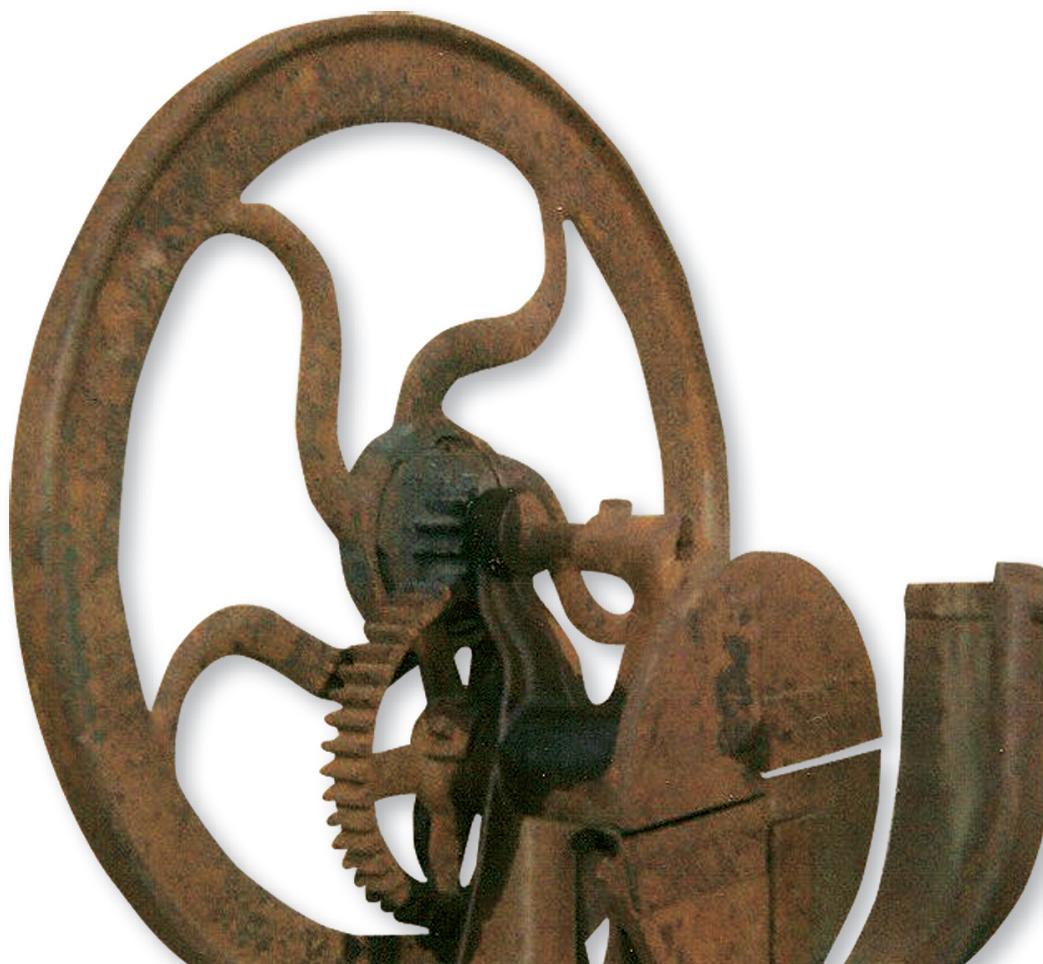

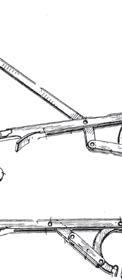

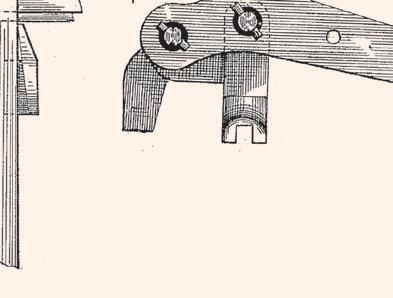

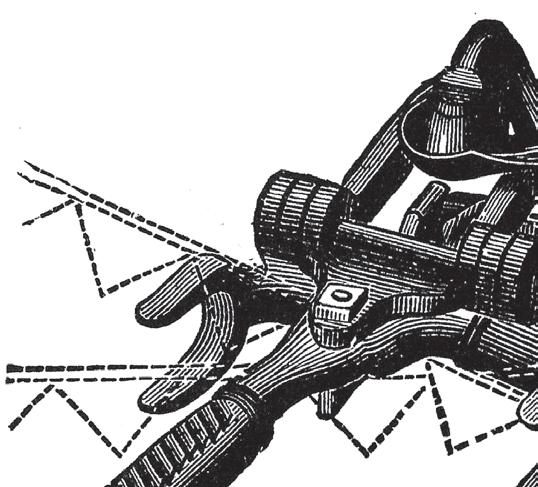

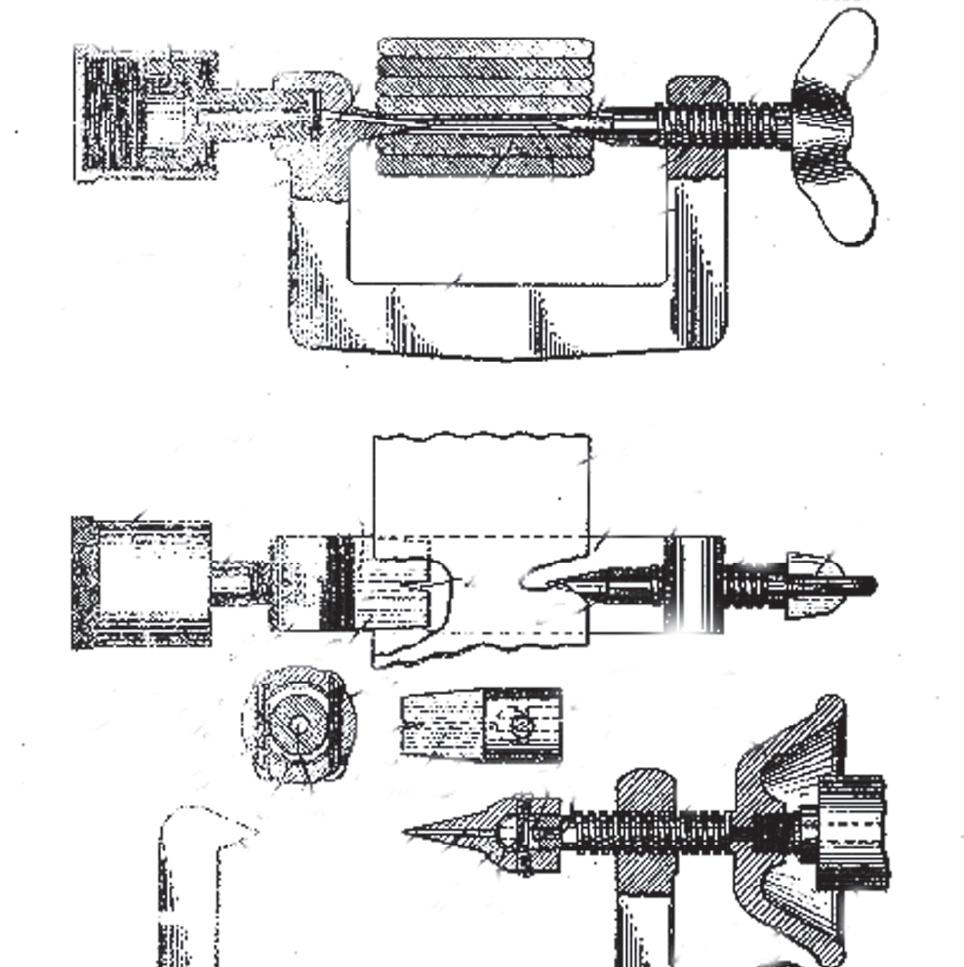

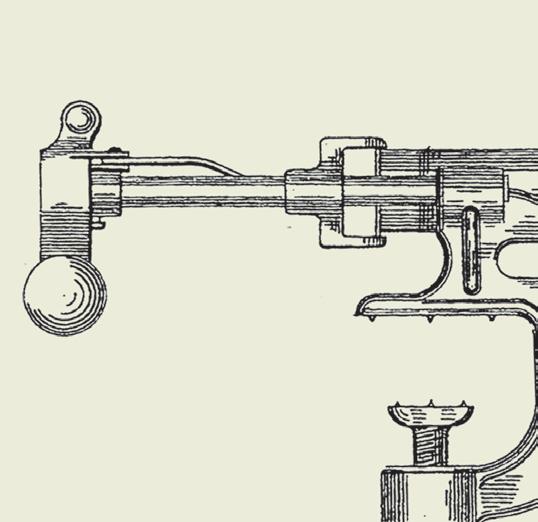

This appears to be a very early or highly modified tree faller attachment for a very popular Kansas-produced log saw. One reader notes that it may have been produced for a tractor saw instead of a portable drag saw. As indicated in the catalog illustration, hooks secured the framework to the tree. The saw mechanism from the unit would be transferred to this framework. A jack shaft would then be extended from the power unit. Another reader concurs, identifying the device as an attachment for an Ottawa drag saw. “It allows you to fell a tree,” he explains. “The photos show it laying on its side not in the working position. By turning it a quarterturn clockwise, it would be in the working position. The two threaded rods with tightening wheels at the far end in the picture are used to fasten the unit to the tree with the use of a chain. The saw blade and gears are removed from the draw saw and placed on the attachment where you see the short heavy pin and gear in the lower picture.

the old growth of the plant so it does not plug up. I remember picking up potatoes behind the plows as a boy.” The reader adds that the middle buster was clamped to the main beam of a potato plow.

One reader identified this as a Plomb Tool Co. weeder dating to the 1920s or 1930s. The handle is made of wood and it has two metal tines for weeding gardens or potted plants. The handle was originally forest green, and the Plomb name should show on one tine. Another reader said the tool was most commonly used to pull dandelions and other weeds with a central root. “The forked blade is pushed into the ground around the root, and the bulge in the handle becomes a fulcrum as the tool is rocked back to lift the weed out.”

9-1/2 inches long. On handgrip: “William Johnson, Newark, N.J.”

This planting dibble (or dibber), was used to set a variety of young plants.

“Alvin Sellens’ book, Dictionary of American Hand Tools, shows that very one,” notes one reader. “Sellens’ book is a very good reference source, and is still in print.”

“The two points (at the bottom) are stuck into the loose cornstalk, one point above the other,” a reader says. “A rope is attached to the crank shaft and passed over the loose roller at the top. It’s then carried around the shock and attached to the crossbar just under the crank. Next the crank is tightened to the desired amount and then held or locked. A piece of twine is then passed around the shock and tied tight, and the shock tightener is released.”

Patent 22,315:

dibble.

according to a similar patent filed in 1911 by Henry Ferris of engage the bundle of grain to be carried.”

A combine can harvest enough wheat in 9 seconds to make 70 loaves of bread. One acre of wheat can produce enough flour to provide a family of four with bread for 10 years.

Patent 423,010: Fodder binder. Patent granted to George Willison, Marysville, Ohio, March 11, 1890. This is not the exact patent for this piece, but it shows how the binder was used.

Patent 365,742: Device for compressing shocks of corn. Patent granted to William Gregory, New Antioch, Ohio. This is not the exact patent for this piece, but it shows how the binder was used.

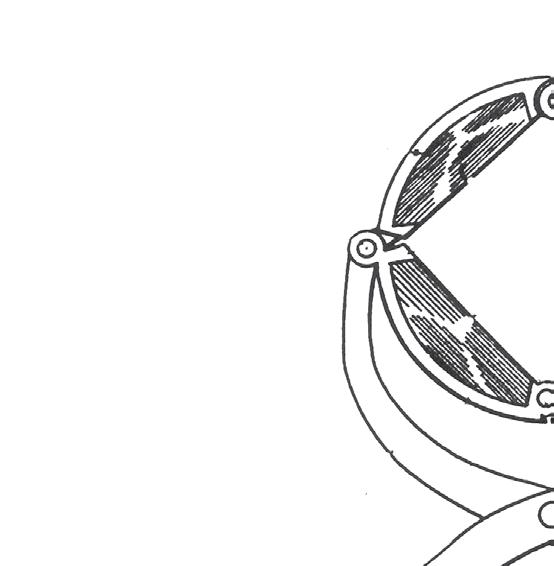

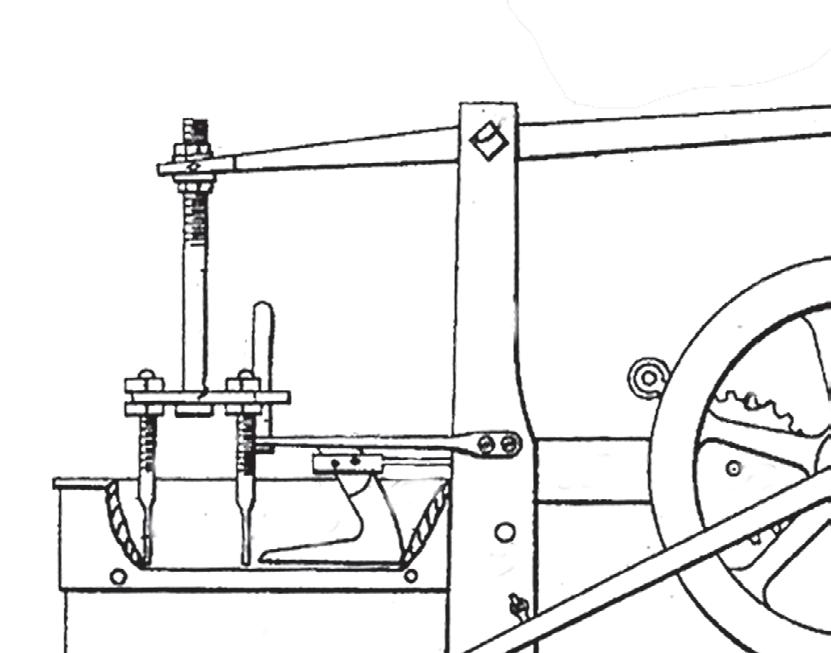

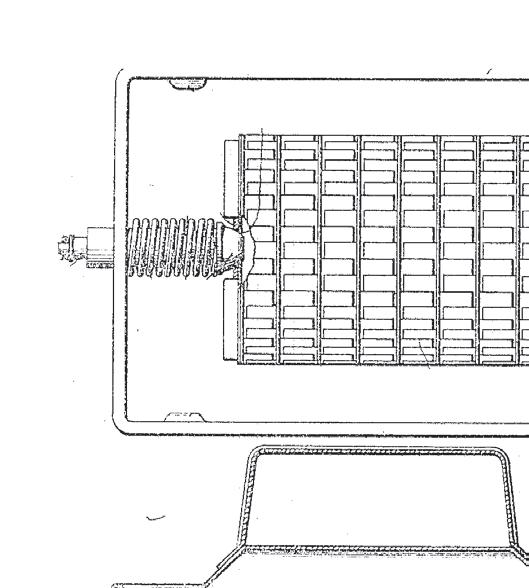

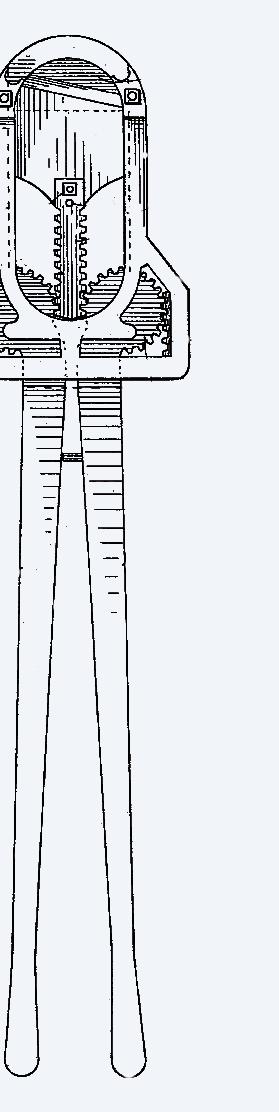

After-market float that goes in the air washer (air cleaner) on an early Fordson tractor.

“I have a 1927 Fordson with that air washer on it,” one reader notes. “The air washer held water in which the air was forced across in order to clean it. When the water got low enough, the float shut the air off thus shutting the tractor down. Having water in the air washer also brought moisture into the carburetor that mixed with kerosene causing the motor to function properly. The tractor would start on gasoline then switch to kerosene after the engine warmed up.”

The rope had metal “buttons” or knots every so many inches, usually about 40 inches. The knots tripped a mechanism on the planter that dropped seed into furrows. This device planted corn in a pattern so it could be cultivated from various directions; later versions used wire instead of rope.

The specific use of this item couldn’t be agreed upon, but it’s used to cut fruit down from highgrowing places. “The tool is used to cut out raspberry cane at the end of the summer,” said one reader. “I used my grandpa’s as a young boy, and I am 81 years young.” It could be used just as affectively on other varieties of fruit plants, depending on the user’s needs.

When it was first introduced 30 years ago, Big Bud caught the attention of farmers and tractor enthusiasts worldwide. The monstrosity of Montana holds the unofficial title of the most famous tractor in the world. John Harvey’s book takes a unique glimpse into this fascinating agricultural icon, complete with stunning photography

#2556

Retail Price $37.47

Sale Price $26.22

This is the first book to feature every Farmall model. It chronicles the background of McCormickDeering and International Harvester and outlines the beginnings of IH’s production of the treasured Farmall tractor from its inception in 1923 (the lightweight, general purpose row-crop tractor that could literally “farm all”) until the last model rolled off the assembly line in the mid 1970s.

#3123

Retail Price $25.99

Sale Price $18.15

This pocket-size guide provides serial numbers, engines and carburetor numbers, magneto codes, specifications decal placement, options and more. It also includes 50 black-and-white illustrations.

#1092

Retail Price $14.95

Sale Price $10.45

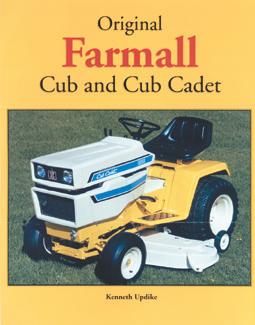

This book presents the most complete and authoritative text available for those wishing to restore their Farmall Cub, Cub Lo-Boy and Cub Cadet, from their inception in the 1940s through the end of production. The detailed text includes hard-to-find information on the development and design of each model.

#2674

Retail Price $37.95

Sale Price $26.55

1831-1985

This is a history of International Harvester farm equipment from the first traction engine in 1906 until the last 5488 all-wheel-drive tractor. It also includes IH-produced implements and combines.

#1049

Retail Price $39.95

Sale Price $27.95

This is a comprehensive collector’s guide to antique gauges. It includes chapters on gauge makers, cleaning and restoring, railroad gauges, fire-engine gauges, portable and tractionengine gauges and more. An astounding amount of information and illustrations on these small machine (and life) savers!

#2233

Retail Price $35.00

Sale Price $24.50

This is the No. 1 guide to North American farm tractors by C.H. Wendel, complete with Nebraska Tests. Explore popular makes and models, research company background and key production information, or just browse through more than 1,500 images!

#2673

Retail Price $32.99

Sale Price $23.05

THE BIGGER BOOK OF JOHN DEERE

This is a model-by-model encyclopedia of John Deere tractors from their first appearance in 1892 to the latest, 2009 models. Photographs showcase beautifully restored tractors as well as unique paintings and artwork from the Deere archives, rare and valuable original brochures and studio photos of John Deere toys and models. This book is an unparalleled compendium of pictures and facts.

#4511

Retail Price $40.00

Sale Price $28.00

From the 1920s well into the 1950s, John Deere tractors powered by two-cylinder engines provided adequate power at more-reasonable prices than most competitors could muster. This complete guide to restoring “Johnny Poppers” provides extensive photo sequences and detailed captions that break the entire restoration process into manageable steps covering engine, paint, wiring and all mechanical systems.

#1445

Retail Price $25.95

Sale Price $18.15

THE FARM WELDING HANDBOOK

This 141-page book covers all the basics for welding projects on the farm. Chapters include setting up a home shop, welding safety and different welding processes. The book is largely devoted to oxyacetylene gas and arc welding, but wire-feed MIG welding is also covered. #2712

Retail Price $25.95

Sale Price $18.15

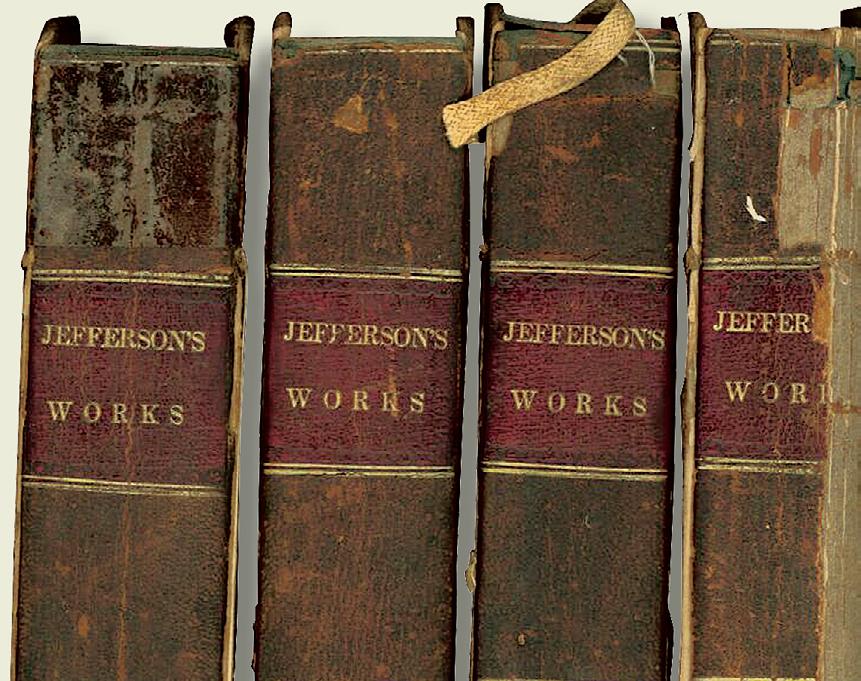

This book describes and illustrates more than 700 antique tools. It covers all categories.

#1208

Retail Price $29.95

Sale Price$20.95

This reference book explores collectibles related to farming in North America from the Civil War to approximately 1965. Also, an identification and price guide, this reference covers everything from old print advertisements to tools to implements and more! The book includes more than 1,000 photos.

#2229

Retail Price $24.99

Sale Price $17.45

This guide covers every tractor collectible from oil cans, thermometers, signs, brochures, pedal tractors, watch fobs and more. Each chapter is written by an acknowledged expert.

#1231

Retail Price $29.95

Sale Price $20.95

Your source for literature on all types of antique farm-related equipment.

By

C.H. Wendel.

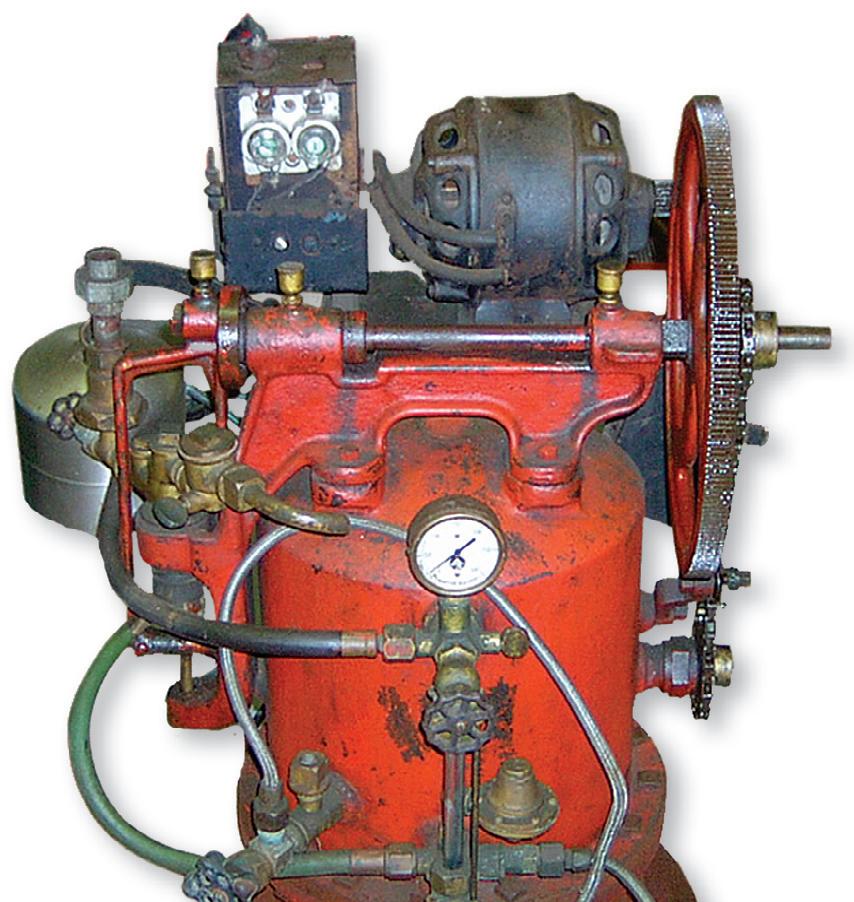

Hardbound reprint of the popular 1983 classic (the one with the yellow cover). This is the original “holy grail” gas engine encyclopedia.

Item # 2823 $50.00

This illustrated history features the brands that have endeared themselves to landowners everywhere — the Cub Cadets and John Deeres, Simplicitys and Fords, Ariens and Kubotas. Accompanied by current and vintage images of these indefinable machines, this chronicle of the garden tractor is a wonderful testament to what makes America work, furrow by furrow. Item #4033 $25.00

STEAM ENGINE GUIDE

This guide details how an engine works and how to make adjustments. It is good for study and reference: reprint of “Threshers School of Modern Methods,” popular in The American Thresherman 1906-1910. Item # 1276 $12.25

This book is both a wonderfully fascinating collector’s item and a valuable piece of American history. For every recognizable item, there are plenty of others guaranteed to confuse 21st-century readers.

Item # 3665 $17.95

Includes a small appendix of Webster bracket numbers and other magneto information, plus an appendix of European engines.

Item # 2824 $50.00

This big book features 500 photographs of Farmall tractors, from that first experimental model introduced in 1924, through the classic lineup of International Harvester models that bore the Farmall name, to the last one to roll off the assembly line. Detailed descriptions combine with vibrant pictures to make this book a full-scale appreciation of the art of farm machinery.

Item # 4497 $25.00

This single hardbound volume is packed with hundreds of period images and manufacturer overviews on construction, printing, sawmill, machine shop and steam industrial equipment. Enjoy hard-to-find information on machines like the Thew Automatic Shovel, the McCabe DoubleSpindle Lathe, the “Liberty” Paper Cutter, the Flory Hoisting Steam Engine and many more in over 400 pages. Item # 4184 $50.00

For the first time, a step-by-step guide to stationary gas engine restoration has been written for engine enthusiasts. Peter Rooke leads you from stripping an engine through rebuilding each component. Also included are data tables containing reference information such as various bolt head and nut sizes, copper wire sizes and bearing tolerances.

Item # 4217 $19.95

By C.H. Wendel. The ultimate resource for gas engine enthusiasts, both volumes combine for nearly 1,000 pages of valuable engine information and photographs. While supplies last.

Item # 3973 $90.00

Stephen Chastain, a mechanical and materials engineer, shows the beginner how to make a sand mold and then how to hone skills to produce high-quality castings. Written in non-technical terms, the sandcasting manuals begin by melting aluminum cans over a charcoal fire and end by casting a cylinder head. Volume 2 contains advanced techniques.

Item #2085, Volume 1 $19.95

Item #2086, Volume 2 $19.95

Compiled by Machinery Pete, the Rust Book is the No. 1 source for actual auction prices on antique machinery manufactured between the 1920s and 1970s. Sales results on nearly 10,000 vintage tractors, implements and trucks including a complete list of serial numbers and tractor test results. It gives specific information on the model number sold. Item # 4117 $19.95

THE OFFICIAL TRACTOR BLUEBOOK

This comprehensive guide provides detailed information on farm tractors produced from 1939 through 2008. Included is information covering approximate retail prices when new plus a range of estimated used retail values. Estimated trade-in values are also included to help you determine the approximate case value or loan value for a tractor.

Item # 4567 $29.95

Multiple orders may arrive in separate packages.

Please allow 4 - 6 weeks for delivery.

THANK YOU FOR YOUR ORDER!

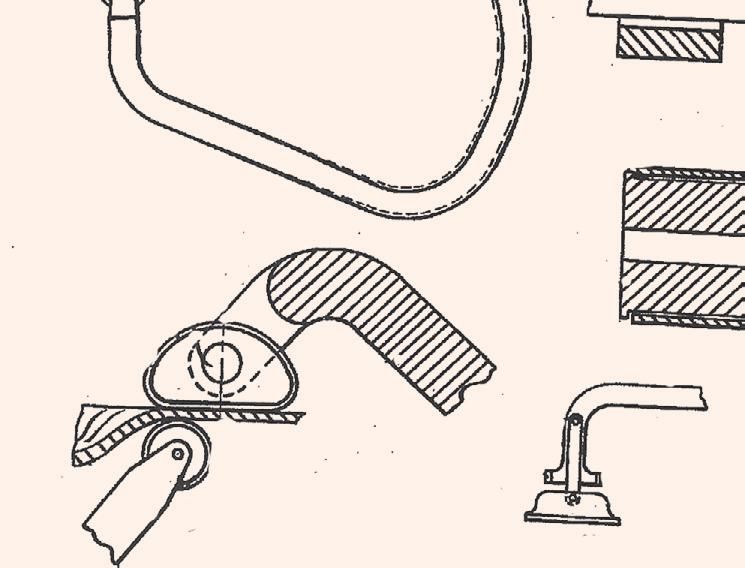

Modern conveniences like the dishwasher , clothes washer and dryer, microwave oven, garbage disposal, food processor and refrigerator tend to make us smug and complacent. “How did the early farm wife do it?” we ask as we consider the relentless work of cooking, food preservation and laundry in an era when few farms had electricity, and everything was done by hand and from scratch.

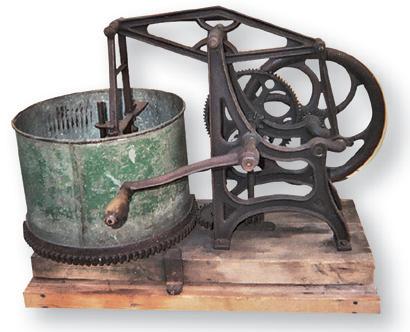

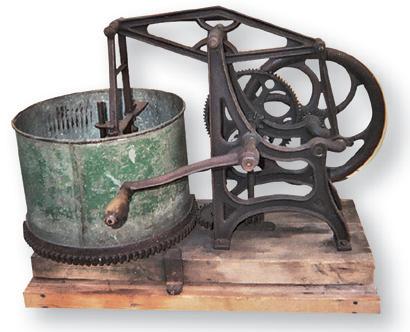

In fact, if her budget allowed, the farm wife of yesteryear had a dizzying array of clever devices, gadgets and gizmos designed to make life easier – though still a far cry from today’s automated routine. Literally hundreds of styles of washing machines existed (initially cranked by hand but later powered by stationary gas engines) and elaborate drying racks were available for inside and outside use.

The farmhouse kitchen was often a large room, and no wonder. The kitchen housed cream

separators, butter churns and workers, cook stoves, steam cookers, meat grinders, egg beaters, peelers, parers, choppers, stoners, seeders, slicers, sausage stuffers, fruit presses, kettles and canning gear. The number of manufactured variations of each item seems nearly infinite.

Devices used to process apples tell the story. The most common and readily available fruit 100 years ago, apples were a dietary staple throughout the country. But until the advent of wide-spread home canning in 1858 (the year the Mason jar was invented), the only way to preserve apples over the winter was to dry them – necessitating sheer tonnage of peelers, parers, choppers and slicers. Inventors saw enormous market potential and began churning out “a better mousetrap.”

Markings vary widely on antique tools and devices; countless pieces carry no markings at all. Many are marked with patent information, but even that information cannot be taken at face value. The patent date, for instance, doesn’t necessarily translate into the year the piece was manufactured. The item may have remained in production for years under the same patent. And the phrase “patent pending” doesn’t necessarily mean a patent was ever actually filed. Inventors sometimes cut corners by putting those words on their inventions with no intention of incurring the expense of filing for a patent. The phrase alone, some believed, would scare off competition.

Look for pieces in this category in antique shops and malls, flea markets, swap meets and online auctions. And pay close attention to the collector community: Your best source could be a dispersal auction representing a collection built over many years. A variety of books have been published on kitchen collectibles, and you can tap into the collector community through Kollectors Of Old Kitchen Stuff. (See the Resources guide for contact information.)

Modern conveniences like the dishwasher , clothes washer and dryer, microwave oven, garbage disposal, food processor and refrigerator tend to make us smug and complacent. “How did the early farm wife do it?” we ask as we consider the relentless work of cooking, food preservation and laundry in an era when few farms had electricity, and everything was done by hand and from scratch.

In fact, if her budget allowed, the farm wife of yesteryear had a dizzying array of clever devices, gadgets and gizmos designed to make life easier – though still a far cry from today’s automated routine. Literally hundreds of styles of washing machines existed (initially cranked by hand but later powered by stationary gas engines) and elaborate drying racks were available for inside and outside use.

The farmhouse kitchen was often a large room, and no wonder. The kitchen housed

cream separators, butter churns and workers, cook stoves, steam cookers, meat grinders, egg beaters, peelers, parers, choppers, stoners, seeders, slicers, sausage stuffers, fruit presses, kettles and canning gear. The number of manufactured variations of each item seems nearly infinite.

Devices used to process apples tell the story. The most common and readily available fruit 100 years ago, apples were a dietary staple throughout the country. But until the advent of wide-spread home canning in 1858 (the year the Mason jar was invented), the only way to preserve apples over the winter was to dry them – necessitating sheer tonnage of peelers, parers, choppers and slicers. Inventors saw enormous market potential and began churning out “a better mousetrap.”

Markings vary widely on antique tools and devices; countless pieces carry no markings at all. Many are marked with patent information, but even that information cannot be taken at face value. The patent date, for instance, doesn’t necessarily translate into the year the piece was manufactured. The item may have remained in production for years under the same patent. And the phrase “patent pending” doesn’t necessarily mean a patent was ever actually filed. Inventors sometimes cut corners by putting those words on their inventions with no intention of incurring the expense of filing for a patent. The phrase alone, some believed, would scare off competition.

Look for pieces in this category in antique shops and malls, flea markets, swap meets and online auctions. And pay close attention to the collector community: Your best source could be a dispersal auction representing a collection built over many years. A variety of books have been published on kitchen collectibles, and you can tap into the collector community through Kollectors Of Old Kitchen Stuff. (See the Resources guide for contact information.)

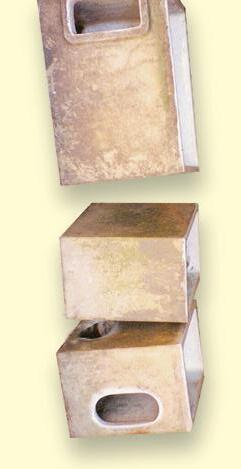

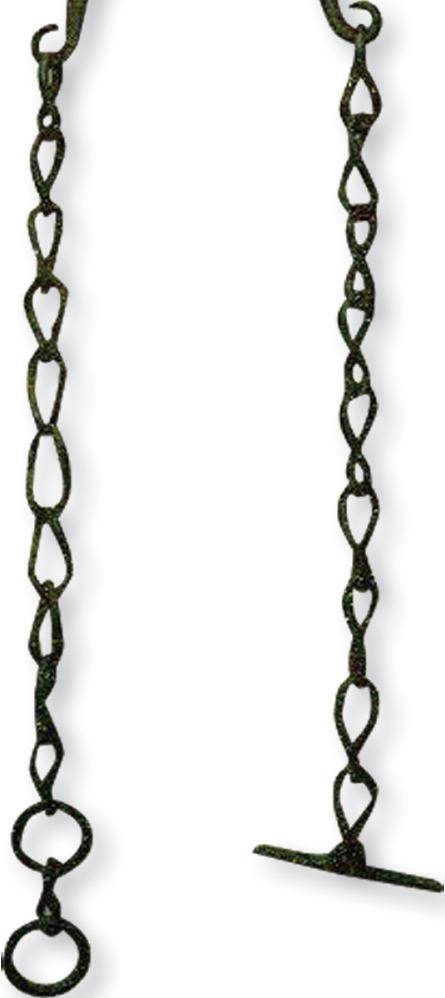

One reader says the two objects were used to move cast iron heating radiators. With one on each side of a radiator, the chain was passed through to secure the radiator. The handles could then be raised or lowered to achieve the desired lifting height.

A lever separates the rollers just enough to slide material in. Spring pressure keeps the rollers together.

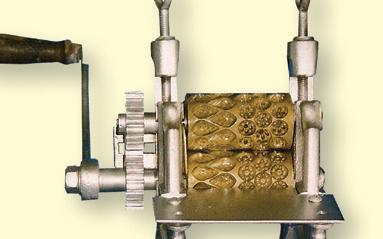

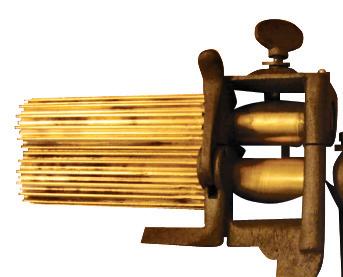

The fluting machine was used to put pleats and ruffles in garments such as petticoats, blouses and collars. In use, heated irons were inserted into the hollow rollers. The heat helped “set” the pleat. One reader suggests an alternate use. “I myself have no use for pleated garments,” he writes. “However, the device might be of sufficiently heavy construction to be used for juicing such things as rhubarb.” Editor’s note: Be sure to clean all the rhubarb off before you next use the device on petticoats!

Several readers thought this piece was a stovepipe crimper. However, the soft brass rollers on this device would not hold up well in that application and would likely become distorted. Also, the rollers are quite a bit longer than the rollers in a crimper.

For more on stovepipe crimpers, including a patent illustration, see “It’s All Trew” on page 35 of the April 2010 issue of Farm Collector.

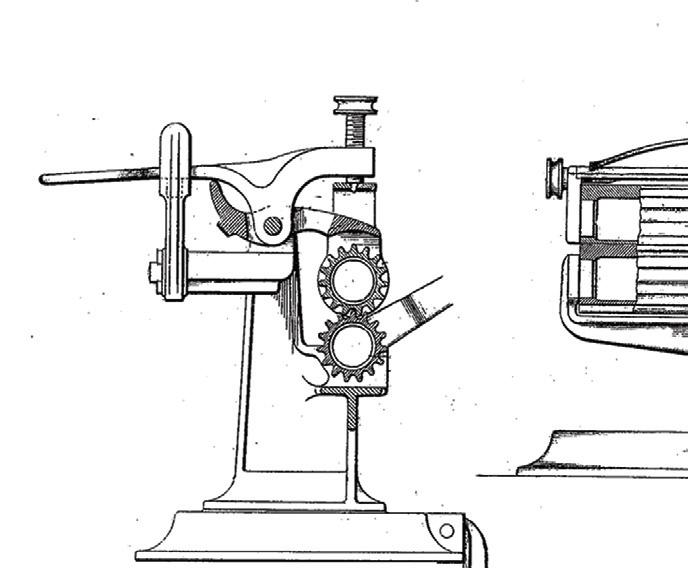

Patent 169,327: Fluting machine. Patent granted to Hermann Albrecht, Philadelphia, Nov. 2, 1875. This is not the exact item but illustrates a similar piece.

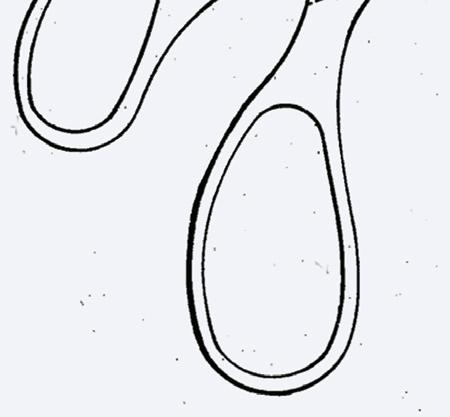

Patent 1,739,358: Looping machine. Patent granted to Emory Gearhart, Clearfield, Penn., Dec. 10, 1929. This is not the exact item but illustrates a similar piece.

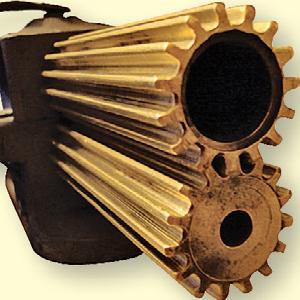

This device is similar to the one a reader once used at Zigenfelder Candy Co. “Strips of candy were fed through the machine via the crank handle. Notches in the wheels formed ‘drops’ such as hardtack and horehound candy. The drops would cool and be hard as rock. There was a similar machine to use in making ribbon candy.” Another reader notes that the bronze twin-roller device was made in England in about 1840.

Patent 111,765: Candy-making machine. Patent granted to Thomas Mills and George R. Mills, Philadelphia, Feb. 14, 1871.

“The rug is hooked from the back, and the linen or jute backing (burlap bag) is stretched on a frame,” a reader explains. “The strip of cloth or yarn is threaded through the metal eye and pushed through the backing to the preselected distance. As you pull the wooden piece back, the strip of cloth is held in place by the threads of the backing. This is repeated over and over to get a hooked rug with even loops on the front. It is a tedious process but yields a smoothly hooked design.”

One Farm Collector reader has a hooked rug device like this one, complete with a box bearing this verse:

One handle up and the other down, Over the burlap so tightly drawn, With scraps of rose and orange and fawn, Bits of purple and gray and blue, And pieces of mother’s wedding gown, Gleaned from the scrap-bag and attic hoard And garments long in the closet stored; Till on the frame a rug there grew! Susan Burr, in the days gone by, Fashioned rugs such as you or I With the self-same needle In the self-same way.”

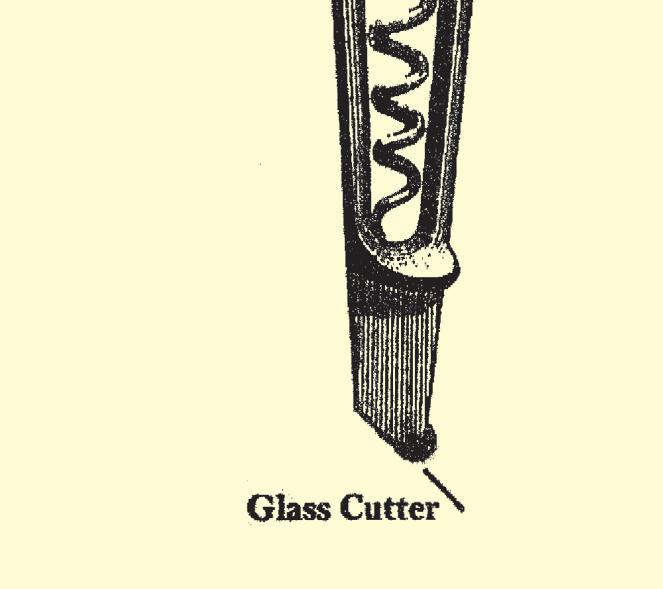

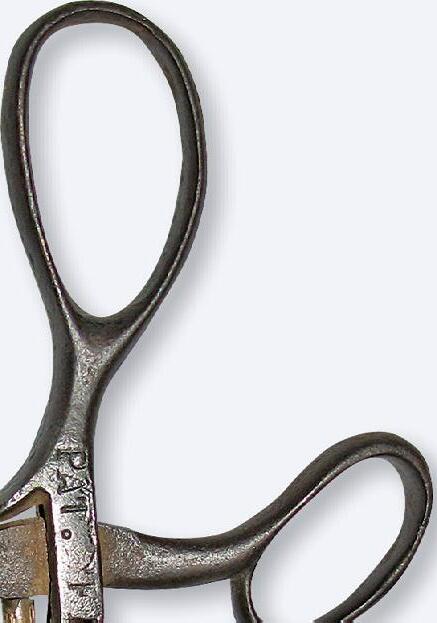

Cast iron can opener made in Decatur, Ill. There are two prongs on the circular head. Insert both in a can and move one handle, cutting the lip open. The other handle holds the can in a permanent position.

According to one reader, this unpatented can opener was produced by William Dodd and C.S. Osborne in 1854. The business partners opened a hardware manufacturing company in Newark, N.J., in the late 1830s. They offered an extensive line of goods and were among the first hardware companies in America.

Tin cans were invented in about 1810 in London by Peter Durand, but the can opener was not invented until almost 50 years later. Prior to the can opener’s invention, cans were opened using a chisel and hammer, knives, rocks … whatever got the can open.

Stamped with “Dutchess Tool Co., Beacon, N.Y., USA Pat. April 4, 1916”

One reader writes, “It was used in cutting pans of bread dough into biscuits or dinner roll shapes. A lot of these are still in use in bakeries and restaurants today. It’s a very durable machine. The Dutchess Company is alive and well today.”

Patent 1,177,835: Dough dividing machine. Patent granted to Frank H. Van Houten Jr. for the Dutchess Tool Co., Fishkill-onthe-Hudson, N.Y., April 4, 1916.

The lemon was inserted in the device and squeezed using the hand levers and fulcrum “so that when power is applied the flat surfaces of the interior of the cylinder will be brought together, forming comparatively a close-fitting joint,” an 1881 patent said. One reader writes that it is “a Little Giant lemon squeezer, probably made by Peck & Stowe.”

Patent 240,858: Lemon squeezer. Patent granted to Joseph C. Steber, San Francisco, May 3, 1881.

This piece is incomplete as shown; it is missing its wheel.

This slid into a pocket in the wall, usually between the parlor and dining room. According to one reader, the door pocket had a wooden track on each side that a 4or 5-inch roller rested on. The rollers were connected to the door hanger, which was connected to the door allowing for ease of movement and storage when not in use.

According to our source, because the vast majority of winders were handmade, no two are alike. From this piece comes the old tune “Pop Goes the Weasel.” After 60 turns, a hank of yarn is produced; an elongated tooth on the gear signals that by clicking or “popping.”

“ From this piece comes the old tune ‘Pop Goes the Weasel.’ After 60 turns, a hank of yarn is produced; an elongated tooth on the gear signals that by clicking or ‘popping.’”

assembly. The device is 24 inches long, 7 inches wide and 3 inches deep. The rollers are 5 inches long and have an outside diameter of 3 inches. Rollers and gears are made of steel; springs press against the axle of one roller against

No markings on the the other.

The one pictured is missing the hopper that held the supply of fruit. The piece was used to crush apples for cider or apple butter. Crushers were also used to process grapes for juice or wine, and peaches, apricots, cherries and blackberries for jam and jelly.

12.

Patent

1,681,920: Fruit

Patent granted to Raffaele Baccellieri, Philadelphia, Aug. 28, 1928.

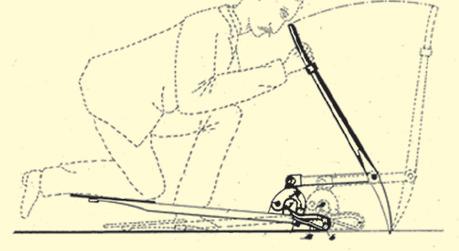

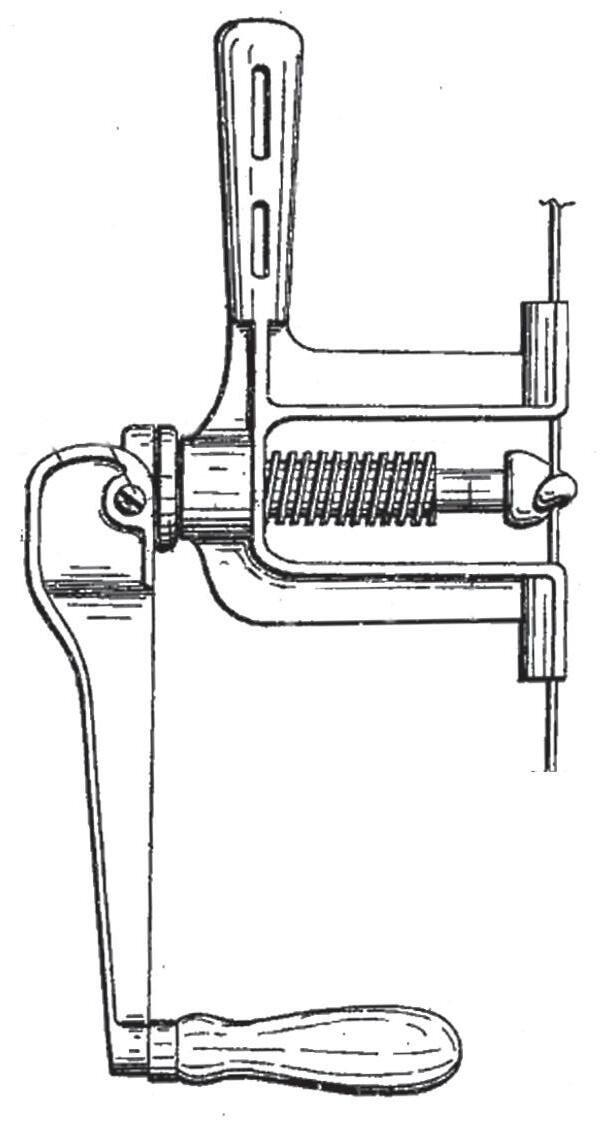

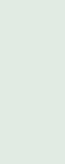

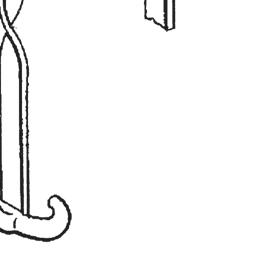

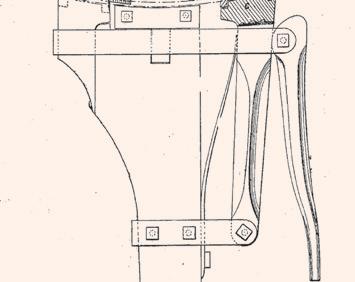

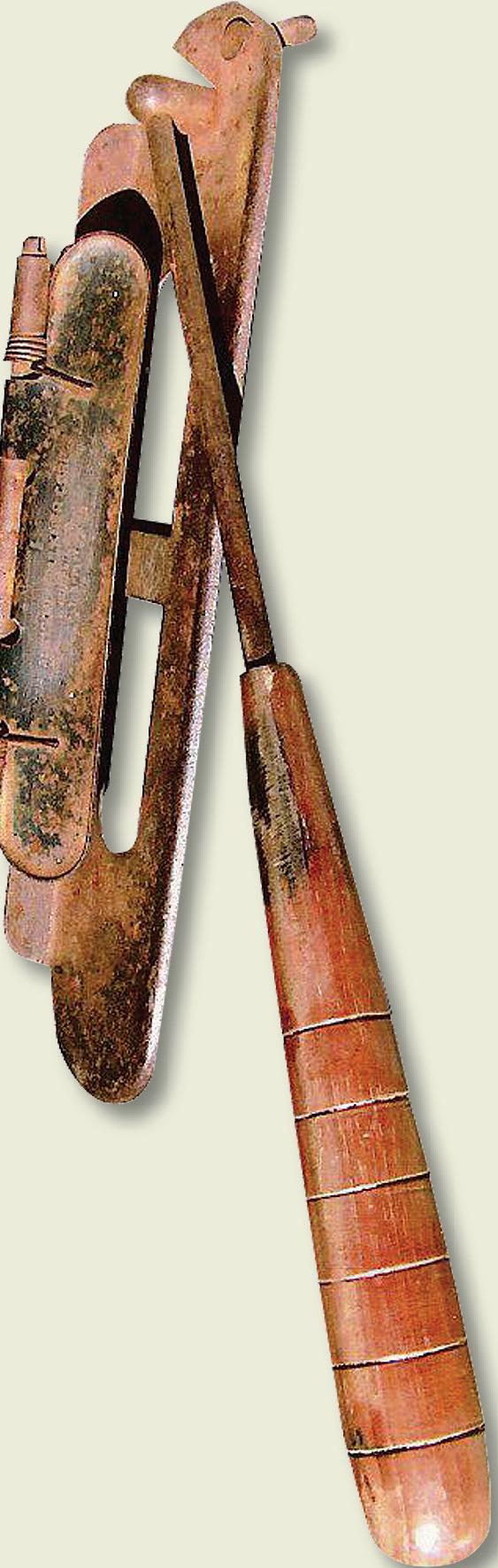

The stitching horse was used by those working with and/or stitching leather. The vertical clamp acted much like a vise. When the operator sat on the bench, he used his right foot to put pressure on the arm near the floor, causing the clamp to close firmly, holding the work so it could be sewed. These were commonly found in harness shops and many farmers used them to repair harnesses.

“This one appears to be homemade, as most were, but the jaw mechanism is not typical of these things,” notes one reader. “They were mostly tightened up with a big bolt and a knurled nut thing. This has a strap passing through the upright to the free arm, which is tightened down by the foot action. Neat. Someone was thinking; speeds things up.”

“My dad used to repair his horse and mule harness on winter nights,” another reader recalls. “He would bring the harness horse into the kitchen near the old kitchen wood range where it was warm. He used an awl and stitching awl for the sewing. The string he used was linen, which is quite strong. The string was rubbed across a ball of bee’s wax to make it water- and weather-proof before the stitching took place.”

Patent 371,198: Stitching horse. Patent granted to Edward Jones, Flint, Mich., Oct. 11, 1887.

This sausage grinder may have been made by the Ames Plow Co. A 5/8-inch exit hole for the ground sausage is on the bottom side; the auger portion lifts out for cleaning.

German inventor Karl Drais is credited with inventing the meat grinder, as well as the “hobby horse,” which was the first modern bicycle, and the keyboard operated typewriter. The grinder we know today is not much different from the one Drais invented – the modern grinder is just faster and more reliable.

“This stand held the boiler or tank that was piped to a coal or wood stove to heat water,” one reader says. “In northeast Pennsylvania where I grew up, almost every house had a boiler hooked to their coal stove in the kitchen. Some were made of galvanized steel and others were made of copper.”

The single hook’s rod slips down inside the outside rod and can control the double hooks (a third finger is missing); 5 feet long.

“After you burn coal you end up with ‘clinkers’ in the bottom of the furnace,” one reader explains. “A clinker is coagulated slag or metal impurities that ‘melt’ from the coal as it becomes coke. Most clinkers consist of pyrites that are naturally included in coal. Periodically one has to reach into the bottom of the furnace with the grapple and remove the hot clinkers. In a home you might get enough to fill a metal 5-gallon bucket. On the farm in the winter, it was my chore when I got home from school to go to the basement and fill up the ‘stoker’ (a box with an auger to the furnace) with coal and remove the ash and clinkers from the furnace.” Another reader notes that a piece is missing from the one pictured. “There should be an opposing finger or hook at the end with the double hook. There were many variations of this tool: Some had five fingers, others had three. Some worked by rotating the handle. In the picture, the handle is what you called the single hook end. Others worked with a springloaded lever that you squeezed or pulled.”

Patent 824,642: Clinker catcher.

Patent granted to Harry Gibbs, Princeton, Ill., June 26, 1906.

timbales, patties, loaves etc.” This mold is a result of that trend. In fact, these molds were “... used to shape a mixture of minced meat, spices, onion & egg into shape of lambchop or drumstick, etc., before cooking, but not used to bake the cutlet in.” One reader noted, “There is a hole in the narrow end to insert a stick for holding while eating.”

300 Years of Kitchen Collectibles further notes

Chicken Croquettes (Mock Chicken Legs)

Ingredients:

2 C. chicken, cooked, boned, cut into chunks

1 onion, cut into chunks

2 cloves garlic, minced

2 Tbs. prepared Dijon mustard

2 Tbs. mayonnaise or creamy garlic dressing

1 Tbs. honey

1 Tbs. vegetable oil

2 tsp. dried basil

Directions:

1 tsp. salt to taste

1 tsp. pepper

1 tsp. paprika

1 tsp. chili powder to taste

1 C. flavored breadcrumbs

Breading:

1-2 eggs, beaten, may add water

Additional bread crumbs for coating.

Vegetable oil for frying

Put all the croquette ingredients into a food processor and chop until finely minced and able to mold into croquettes. (Adjust consistency by adding oil or breadcrumbs.) Shape into patties (or chicken leg shapes). Dip in beaten egg, roll in breadcrumbs and fry until golden and cooked.

Tip: Insert a popsicle stick to lift the leg and eat it from the “bone.”

One reader sent in a picture of what this tool should look like if it were complete. It is used to wring out wet clothing.

The clothes wringer was invented by Ellen Eglin, an African-American woman, in 1888. She sold the patent for $18 because she believed white women would not want to use the wringer if they knew it was invented by an African-American.

This device was used in securing fruit jars while opening or tightening the caps. It was adjustable to accommodate jars of different sizes. Such pieces sometimes had clamps, which held the base to a tabletop. This piece was patented Oct. 12, 1909.

The arm on bottom is 10 inches long. The arm on top (with the loop at one end) is 11 inches long, and the connecting piece is 4-1/2 inches.

“Inside the body are small balls spring-loaded into the coneshaped bottom,” one reader explains. “Release them by pushing down on the ring-shaped collar at the top (inside) of the wire loop, which serves to attach the anchor to some fixed point. Push a rope through the opening at the bottom on out the top and then release the collar. The balls are forced down, holding the rope. The tighter the rope is pulled, the more the balls grip against it. To release, just push down on the collar again.”

Patent 444,415: Carpet or oilcloth stretcher. Patent granted to Andrew R. Anderson, New York City, Jan. 13, 1891. This is similar to the tool shown above and illustrates how a carpet stretcher works.

William Sprague is credited with starting the United States’ carpet industry when he opened the nation’s first woven carpet mill in Philadelphia in 1791. The industry took off in 1839 when Erastus Bigelow invented the power loom for weaving carpet, which tripled carpet production by 1850 and paved the way for further loom advancements.

This piece appears to be an improved version of a knife cleaner and polishing machine, primarily used to clean and polish table knives. The piece was patented in 1914 and produced by Ernest Koeppen, New York.

“The pointed end was used to lift the hot lid off the top for filling and also the ash pit cover,” one reader wrote. “The square hole would fit over a grate end that protruded through the side of the stove to shake ashes down from the firebox into the ash pit.” An alternative possibility suggested by a reader was a tack puller with a square socket used as a wrench to open and close the gas valve

The device is used to cut a variety of foods including kraut, slaw, cabbage, vegetables and pickles.

According to the 1886 patent, “It is customary for the manufacturers [of wallpaper] to leave a margin along both edges, one of which margins, at least, must be trimmed off, in order to allow the papers to be placed upon a wall in such a manner that the ornamental design may match from one strip to the next and together form an unbroken figure. Further, it is desirable that the edge of the paper shall be so cleanly cut as to leave no fuzz.” The patent continues, “The object of our invention is to furnish a machine ... that shall expeditiously do the work of trimming wall-paper.”

Patent 346,307: Machine for trimming wall paper. Patent granted to J. Harvey Miltimore and Henry Underwood, Waukegan, Ill., July 27, 1886.

“Improvements in devices for preparing beef-steaks for broiling.” The piece was used to strike a piece of meat. On each strike, the device’s sharpened teeth scored the meat. The spring-loaded rod then pushed the meat off of the device. Other readers identified the piece as a clapboard marker, an item with a very similar appearance.

One reader claims this was used for coal release. “It slides on the bottom of a cylindrical chamber that runs from the top of the stove down through the middle. This is what you pour the coal in. This mechanism releases the coal into the bottom of the stove.”

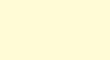

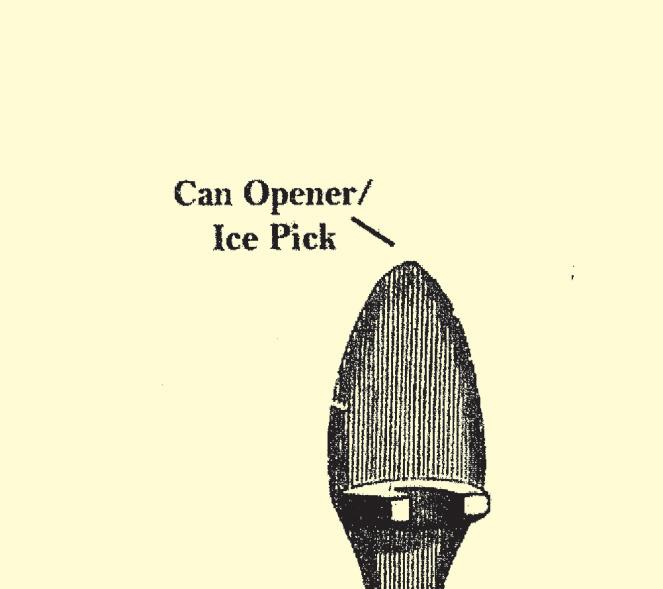

This was used for a wide variety of tasks. In the September 2004 issue of The Chronicle (a quarterly publication for the Early American Industries Assn., or EAIA), it was said that one Samuel C. Monce is more-or-less credited for this idea, which started out as a simple glass cutter. His 1869 patent was invalidated in 1879, due in part to a man by the name of Woodward, inventor and manufacturer of the Woodward multi-tool. Woodward claimed he came up with the idea first, though there are no patent records to

Three ceramic boxes: large, 18-by-24-1/2by-17 inches; medium, 11-3/4-by-19-by-16-1/2 inches; small, 11-7/8-by17-3/4-by-16-7/8 inches.

Patent drawing of Samuel C. Monce’s combination tool. Monce was a forerunner in the industry. Image courtesy of The Chronicle, Volume 57, No. 3 (September 2004).

These were used in early iceboxes. When one reader acquired a large estate icebox, he found the top section (where the ice would be placed) lined with galvanized metal. The lower sections contained the porcelain boxes. “They were arranged so that the cold air from above ‘fell’ down below, passing through the holes in the stacked porcelain boxes. The cool air fell to the bottom of the top porcelain, typically falling out another vent on the bottom to the next porcelain below on its way through the stack. In that way, the cool air circulated down, and the mass of the porcelains helped keep the food colder for a given mass of ice. Of course, the porcelains were also easier to keep clean than metal shelving.”

Early refrigerators used toxic gases like ammonia, sulfur dioxide and methyl chloride as refrigerants. Deadly leaks led to the invention of chlorofluorocarbon, or Freon, by 1930.

Dubbed “The Combination,” the unit was produced by The Lord Manufacturing Co., New Haven, Conn. If complete, it will have one wheel with sandpaper and another with a brush, the latter used to clean chalkboard erasers. Promotional material claimed that the unit would “do away with much of the disagreeable part of cleaning erasers.” “I presume that means keeping the dust down,” one reader writes, “but I wouldn’t want to bet on it.”

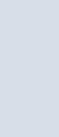

This bowl clamp was used with a cream separator.

“We have one just like this,” one reader says. “Bolt it to the wall, set the bowl into the spring and use the wrench (not shown) to loosen the ring so you can take the bowl apart to clean. Before separating next time, set the bowl in the spring, assemble the discs, cover and ring, and tighten before setting up the separator.” Some manufacturers built the clamp into the separator itself; others provided the customer with a cast iron wall bracket with the bowl clamp installed on top of it.

Patent 575,964: Combination pencil sharpener and eraser cleaner. Patent granted to Percy Lord, Riverside, Calif., Jan. 26, 1897.This patent drawing shows the eraser cleaning wheel (bottom left) and pencil sharpening wheel (above).

Patent 1,453,802: Combined milk reservoir and bowl clamp support for cream separator. Patent granted to Theodore H. Miller, Poughkeepsie, N.Y., assignor to the DeLaval Separator Co., New York City, May 1, 1923.

This book/parcel/shawl carrier was likely home-made. Similar items are shown below.

Although occasionally misidentified as a marshmallow maker, in fact this apparatus is designed to use in washing cream separator skimmers.

Patent 303,896: Shawl strap. Patent granted to William B. Tharp, Eagle Pass, Texas, Aug. 19, 1884.

Patent 401,073: Shawl strap. Patent granted to Max Rubin, New York City, April 9, 1889.

Patent 412,295: Shawl strap. Patented granted to Howard W. Reynolds, Rochester, N.Y., and N.E. Stoneburn, Rochester, N.Y., Oct. 8, 1889.

Patent 1,121,731: Apparatus to wash cream separator skimmers. Patent granted to Perley L. Kimball for Vermont Farm Machinery Co., Bellows Falls, Vt., Dec. 22, 1914.

We carry a large selection of quality meat processing equipment. Meat Tenderizers, Electric Smokers, Manual and Electric Meat Grinders, Sausage Stuffers & Food Dehydrators Visit our website: www.madcowcutlery.com or call (325) 597-2621

We have the lowest prices & free shipping on most processing equipment!

The stockman of yesteryear was equipped with an enormous selection of tools with which he managed his herd and flock. For cattle, there were blinders, staffs, leaders, calf weaners, dehorning clippers, brands, ties and “staking out” chains. For hogs, there were snouters, ringers, holders, ear notchers, waterers and oilers. There were leg bands, nest eggs, markers, grit machines, perch brackets, bits and egg testers for poultry; shears, brushes, picks and clippers for sheep and horses – the list is nearly endless. Dairymen, too, required their own tools: pails and seats, thermometers, gauges, testers, lactoscopes (to determine cream content in milk) and lactometers (water content).

Early manufacturers rose to the challenge and regionally produced tools were widely available. General stores, hardware suppliers and catalog merchants like Sears & Roebuck and Montgomery, Ward & Co. carried extensive inventory and the tools were commonly used across the country.

For the collector of livestock tools, an interesting subcategory exists of farmer-made devices. The rough equivalent of primitive household antiques, these pieces are marked by particular

ingenuity and economy. They don’t come easy: Your best bet may be to scour antique shops, flea markets and swap meets, particularly in the eastern part of the country.

Another offshoot of the category is stockyard collectibles. That group of items revolves around printed materials (bulletins, photographs and schedules), small premiums and signs, as well as animal handling tools and devices.

Most livestock tools were manufactured and used from the 1880s to about 1930, with a primary focus on controlling animals while minimizing the handler’s exposure. Hog tools were very widely used in eastern states; collectors in the west may find more cattle tools there than hog tools. In general, livestock tools are increasingly difficult to find outside of collection dispersal auctions. Regardless of whether you place a winning bid, collections built over the past several decades offer rare opportunity for the novice to see tools only seldom encountered otherwise.

Many antique tools were relegated to the dust heap of history when early machines and processes became obsolete. Corporate farming has had its impact, to be sure, but even by the 1940s most of the tools in this category had been abandoned – yet livestock remained a vital part of many farm operations. What changed?

One answer may be the evolution of fence design, construction and materials. Early fences were notoriously weak and ineffective. As confinement methods became more sophisticated, the stockman’s job changed in subtle ways. And yet no farmer worth his salt would throw away a perfectly good tool – at least not until the scrap metal drives of World War II, which account for short supply of many farm relics.

The 1875 patent reads in part, “The sheep, having been placed on the seat in the position desired for commencing the clipping, is not changed during the entire process. As the clipping progresses the platform is revolved, so as to bring the rack into different relative positions to the sheep.”

Used for holding a cow’s tail while milking. According to an 1890 patent for the device, “When the handles are released, the spring will actuate the curved arm, forcing the latter, as well as the jaw, in an inward direction and retaining the device upon the leg and tail of the animal.”

Patent 161,622: Sheep shearing chair.

Device to hold up a horse’s collar when the horse has a sore neck, so the neck can heal while the horse continues to work.

According to an 1862 patent awarded to Reuben Hurd, of Spring Hill, Ill., “The animal to be operated upon is grasped by the operator or an attendant and the operator distends the back parts of the levers by means of the finger and thumb, and thereby throws out the knife from the block. The block is then placed against the end of the upper part of the snout of the animal and the knife is then forced against the block, the former passing through the rim of the snout and severing it, so that the animal loses all power over it for ‘rooting’ purposes.”

Patent 34,368: Improved device for cutting the noses of swine to prevent them from rooting. Patent granted to Reuben Hurd, Spring Hill, Ill., Feb. 11, 1862.

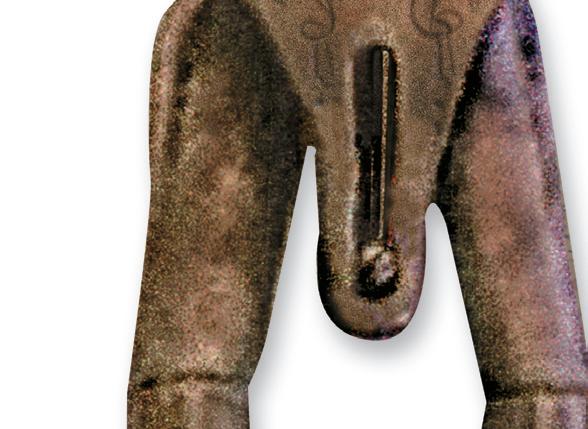

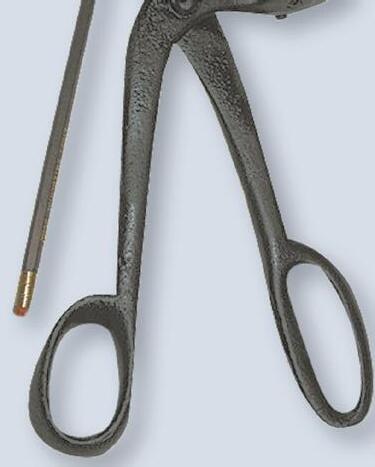

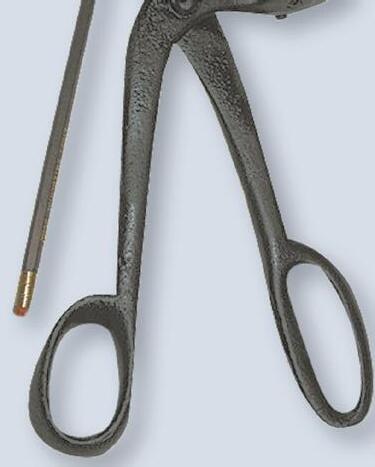

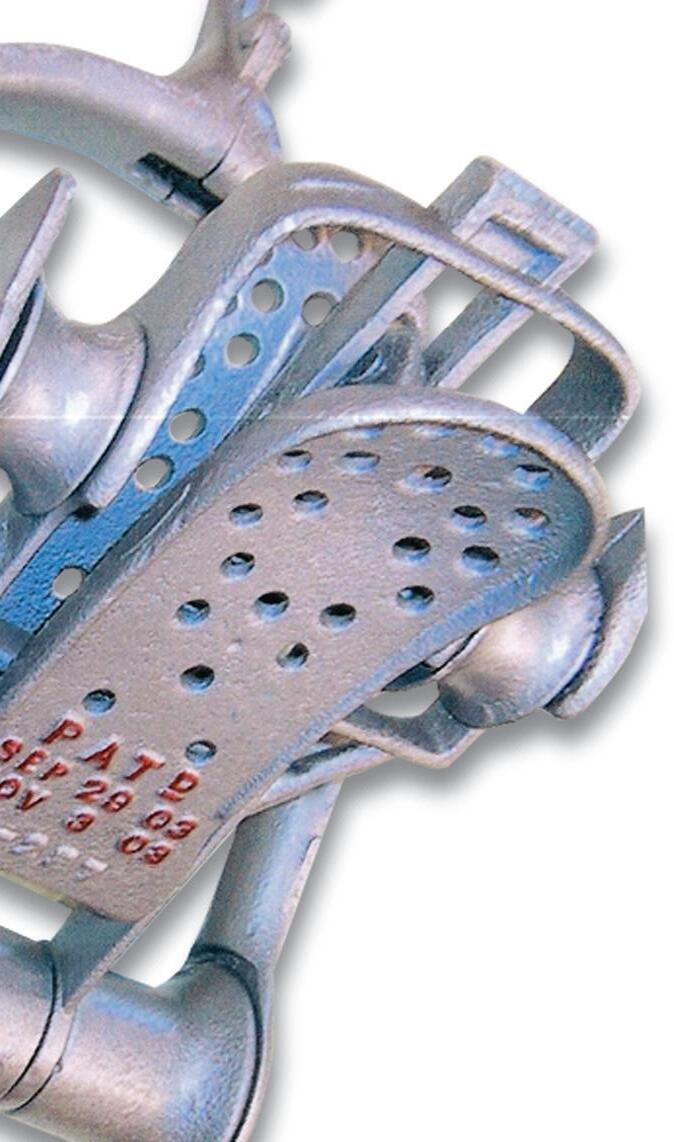

Identified as the cheek pieces of a veterinarian’s speculum. “It is used to examine the mouth, particularly the teeth for sharp edges, as these teeth grow continuously and must be ground off with a rasp (also known as a float),” notes one veterinarian.

Both rings would be centered at the bottom of the yoke to attach the load. The elongated section went through the wood of the yoke and was secured at the top with a pin. The tongue of the wagon would be hitched through the larger of the rings and a chain would go through the smaller ring.

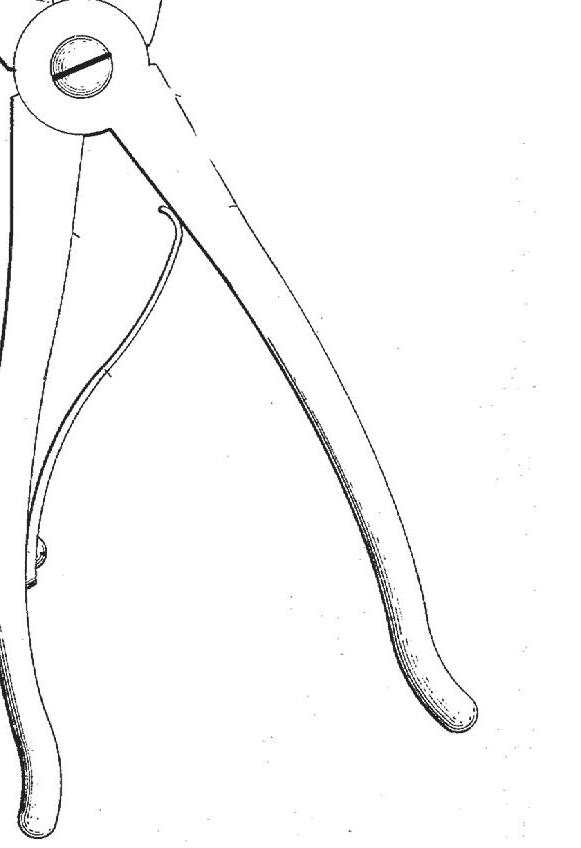

Patent no. 511,885: Hoof trimmer. Patent granted to W.K. Fraley, Lebanon, Ind., Jan. 2, 1894.

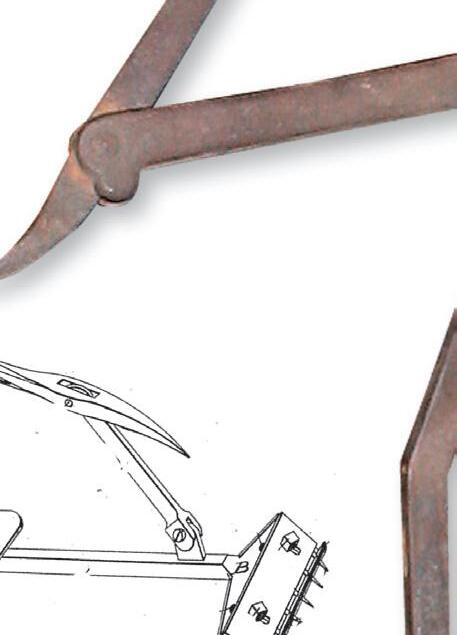

Compound-action horse hoof trimmer.

Nineteen inches long. This has the appearance of a chamfer knife, but has replaceable blades on both edges and is too wide for a drawknife operation.

One reader says the tool, known as a “fleshing knife,” was used to scrape fat and tissue from the flesh side of a hide before tanning. “The blade was used in long scraping motions, and was kept very sharp, necessitating the T-shaped handle to maintain the correct angle with the hide,” he explained. “If the angle changed too much, the knife would slash the hide, ruining it.”

If the angle changed too much, the knife would slash the hide, ruining it.”

A pig uses its snout much like a human uses its hands. The rooting disc, located on the end of the snout, contains as many sensory organs as a human has on both palms. “Ringing” discourages rooting and digging as it makes it very uncomfortable for the pig.

“The tongs are used to clamp and hold the hog’s snout while the ring is applied,” one reader says. A similar piece was manufactured by E.C. Stearns Co.

Patent 145,105: Hog tongs. Patent granted to Hugh W. Hill, Decatur, Ill., Dec. 2, 1873.

and by moving and guiding with the pole, the jaws were placed on the rear leg. The rope was then pulled, closing the jaw around the leg by pulling away on the pole. It would separate itself from the catcher and you could then use both hands to hold the rope and grasp the animal by its front legs to wrestle it into position.

The patent was issued to John R. Wilson and Wilson M. Baker, both of Urbana, Ohio. “We have invented a new and improved Hog Holder,” noted the patent applicants. “The invention consists of a stout rod, preferably of metal, bent so as to form a loop or handle, whose legs cross each other, and are soldered or otherwise fastened together and whose ends are hooked, notched, or perforated, for the

strap, which is attached to them. If the chain is placed in a hog’s mouth, a turn or twist of the loop portion of the device instantly forms a hitch of the chain over the hog’s nose, making it easy to hold him thereby, or to throw him down, if desired.”

Pictured at right is another type of hog holder. “The holder was placed over the hog’s upper jaw,” one reader says. “The hog would back up, trying to get away. When the holder was tightened on top of the hog’s nose, the animal would stand still for vaccinations, castration, tooth clipping, etc.”

.

. one reader recalls.

This piece was probably made on the farm or by a local craftsman. The 4-bar reel on top served two purposes: It kept chickens from getting into the feed trough and scratching out the feed. If the chicken hopped onto the reel, it rotated, dumping the fowl to the ground.

Patent 2,136,587: Feeding and watering device. Patent granted to Donald S. Gaskill, Lyndonville, N.Y., Nov. 15, 1938.

did you know?

In 1910 there were 61 million cattle in the United States. By 2007 that number was 97 million cattle – an increase of 59 percent.

Patent 253,359: Hog tendon cutter. Patent granted to Orville Ewing, Decatur, Ill., Feb. 7, 1882.

This hog tendon cutter was used to cut tendons in the hog’s snout to prevent rooting.

Although the hog might be expected to see matters entirely differently, a copywriter for Bell-Hart promised the anti-rooter would deliver happy outcomes: “That means hog heaven for me for I can’t root,” reads text accompanying the drawing. “I’ve been operated on with a Bell-Hart Anti-Rooter.”

Hog “anti-rooter” used to nip the end of a hog’s nose to prevent rooting.

“This item sold for $33 per dozen in the 1925 Belknap hardware catalog,” one reader reports.

Marked: “C.H. Dana West Lebanon, N.H.”

Patent 339,152: Nose ringing tool. Patent granted to Charles H. Dana, West Lebanon, N.H., April 6, 1886.

there. The pole represented the staff the patient gripped to make his veins bulge. After the procedure, the bandages used to stop the bleeding were hung on the staff to dry, creating the famous red-and-white pattern.

ends grasped around the piglet’s eye sockets. If that failed, the tool was turned around and the piglet was grasped with the pliers-like end,” one reader notes. Pig pullers were used on livestock farms from the late 1890s to 1920s.

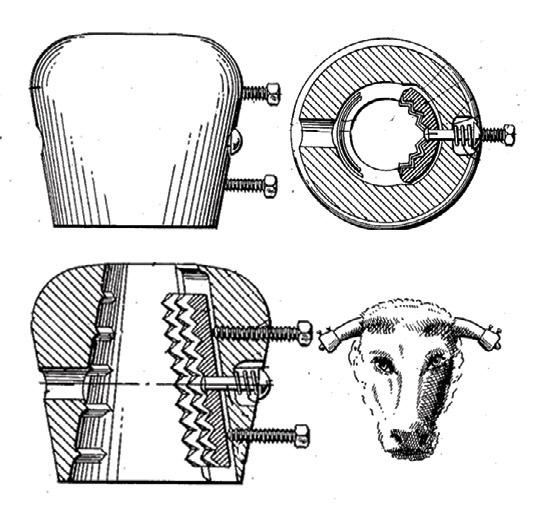

“A lot of times a bull’s horns would grow in a curve into their cheek,” one reader notes. “The horn would have to be clipped off or totally removed.”

Dehorning also protects cattle from injuring other animals, “especially in feedlots,” another reader says. “Horns are often left on cows that roam free where there may be predators such as coyotes, so they can better protect themselves and their calves. Some breeds of cattle do not grow horns.”

“When the horns on younger cattle weren’t turning down as they should, horn weights could be put over the ends and the screws tightened to hold them on,” explains one reader. “They came in different sizes and weights to take care of varying ages and sizes of the horns and how much they needed to be turned. They were left on three or four weeks and then you’d check to see the results, or put them back on if they came off. It was best to confine the cattle to a small lot so you could find them again. If the horn was starting to make some turning (and that would be at the base where it was growing out), it might be best to take them off and let the horn grow out more and repeat a little later. If too heavy a weight was used and left on too long, the results would be a sharp angle in the horn and it would look very unnatural.”

Another use, according to another reader: “They helped prevent injuries if two bulls (or cows) were fighting, and could be used to restrain a bovine by attaching a rope or chain to the weights.”

And the numbers shown on the weights? “The 1-1/2 is the weight of the casting and they came in different weight sizes,” explains another reader, “depending on what the showman wanted to accomplish and how fast.”

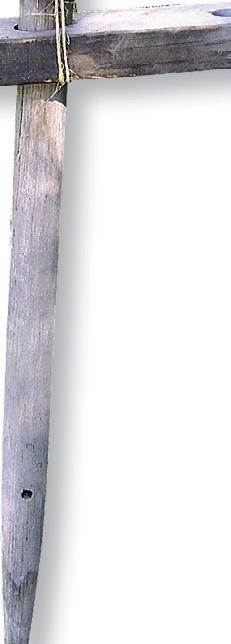

Patent 2,244,810: Horn forming weight. Patent granted to Ernest Stone, Denver, June 10, 1941. This is not the exact patent but it illustrates a similar piece. Patent 534,112: Dehorner. Patent granted to Harry Leavitt, Hammond, Ill., Feb. 12, 1895.o a farmer, the barn and farm shop are the rough equivalent of a businessman’s desk and file cabinet.

Home to a vast variety of tools for every conceivable purpose, the building’s interiors may look chaotic and unorganized to the untrained eye. But look closely and a uniquely individualized system unfolds.

Here you find a range from a blacksmith’s forge to engine repair; tools for saws and sawmills, implements, wagons and carpentry. While other tools were carried to the field for fencework or onsite mechanical repairs, the barn and shop were headquarters for planned maintenance.

The barn was also the site where large amounts of milk were processed in cream separators, grain was shelled, and fodder was cut, ground, milled and compressed for later use. In many cases, the barn offered shelter to livestock, which translated into daily chores associated with feeding and watering, cleaning stalls and gutters, and spreading straw.

The loft, of course, offered centralized, weatherproof storage for hay, and hay tools make up a very popular collectible group. Common to farms across the country, the category includes forks, spears and harpoons as well as barn tools such as carriers,

slings, pulleys and tracks. The latter pieces often remain intact in decades-old barns, but because of their location at the building’s most inaccessible point can be frustratingly just out of the collector’s reach.

Because of their size and somewhat awkward stance when out of their element, hay tools are less commonly found on eBay or in antique shops than many farm collectibles. When they are found online shipping charges can be hefty. As a result, auctions, flea markets and swap meets are good sources for such items.

Manufactured as early as the 1840s, hay tools such as those cited here began to fade from the landscape in the 1930s. Hardbound annual catalogs produced early in the last century by Louden Machinery Co., Fairfield, Iowa, and F.E. Myers & Bro., Ashland, Ohio, are very useful to the collector of barn and hay tools. Other leading manufacturers of the era included Ney Mfg., Canton, Ohio, and J.E. Porter Co., Ottawa, Ill.

Vintage catalogs from hardware suppliers, farm supply houses and general merchandisers like Sears & Roebuck or Montgomery, Ward & Co. are equally reliable references when researching vintage barn and shop tools.

The North American Hay Tool Collectors Assn. offers a wealth of information to those interested in hay tools and related pieces. (See the Resources guide for contact information.)

onto the ‘+’ and ‘-’ post of the battery, allowing it to be carried. The wood on the handle did not pass the current or cause a short. My father had an Esso (later to become Exxon) gas station in Quincy, Mass. My brother and I worked many years there and used the same type tool often. My dad (who is 90) still has it hanging up in his garage.”

Patent 2,435,549: Battery carrier. Patent granted to Chester Sumter, Knoxville, Tenn., Feb. 3, 1948. This is not the exact patent but it illustrates a similar piece.

According to a Feb. 21, 1927 patent, “My invention relates to devices for stripping or otherwise removing objectionable kernels from ears of seed corn and its object is the provision of a hand operated tool of extreme simplicity of construction and operation, the tool being designed to strip the kernels from the butt and tip of the ear and to remove defective

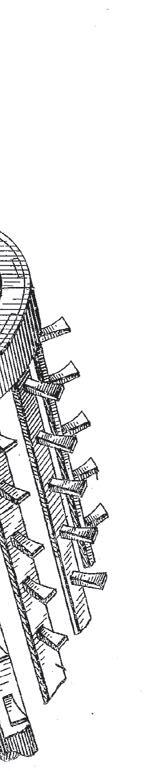

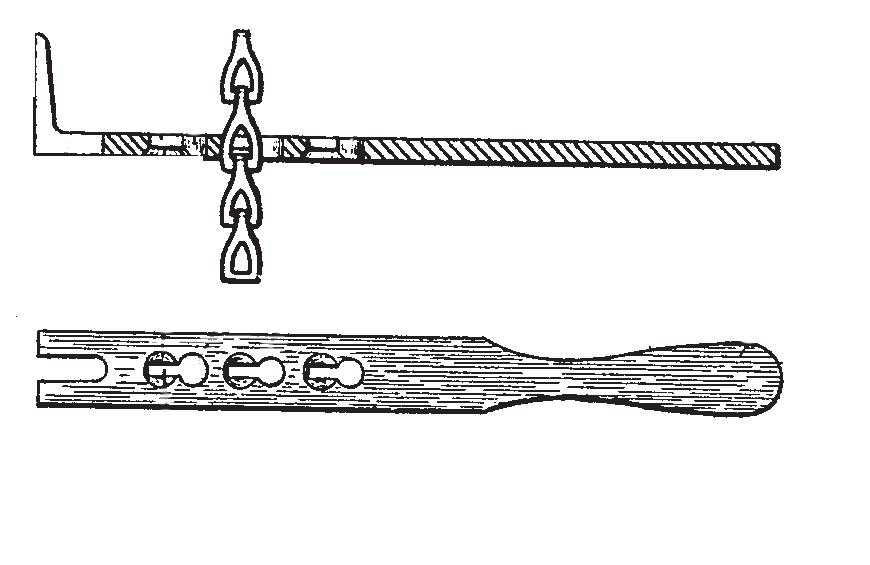

According to an 1869 patent, this corn sheller’s opposing coils apply pressure to the corn cob, thus scraping the corn kernels away. “The disks, owing to their form, and being placed on opposite sides of the coils, act in the manner of a screw, progressing forward or backward, as they are revolved about the ear of corn. As the forward disks advance, they are pressed between the kernels, which are removed from the cob by the follower, as it advances. To operate the sheller, place one end of an ear of corn between the jaws. Then, hold the ear with the left hand, with the right grasping the handle, and revolve the sheller about the ear.”

The word “corn” means different things in different countries. In England, corn means wheat, while in Scotland and Ireland it means oats. And references to corn in the Bible are thought to be about wheat or barley.

“The item shown is upside down without the lid. The fittings are brass,” a reader says. “The reservoir fits in a cast iron bracket that has capacity for eight milker inflations assembled on their ‘spiders’ and housings. We had a two-unit RiteWay milking machine with a reservoir that looks like this one. I have the sanitizing reservoir and bracket among my farm memories.”

“It was hung so the solution ran into the teat cups until they were full, then the valve was shut off to stop the flow,” another reader says. “At the next milking, the teat cups were held higher than the disinfectant container, the valve was opened and the solution flowed back in.” The device, which was attached to the wall with a bracket, was used after washing the milker.

Patent 685,282: Cylinder wrench. Patent granted to John Johnson, Storden, Minn., Oct. 29, 1901.

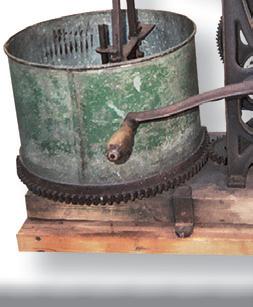

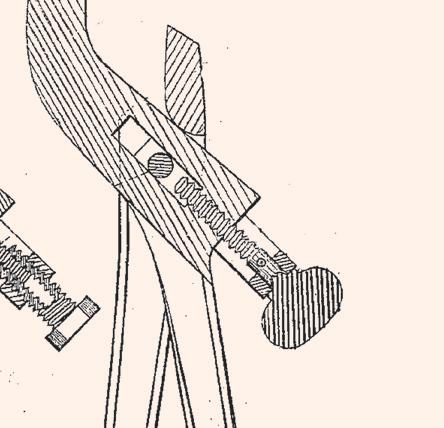

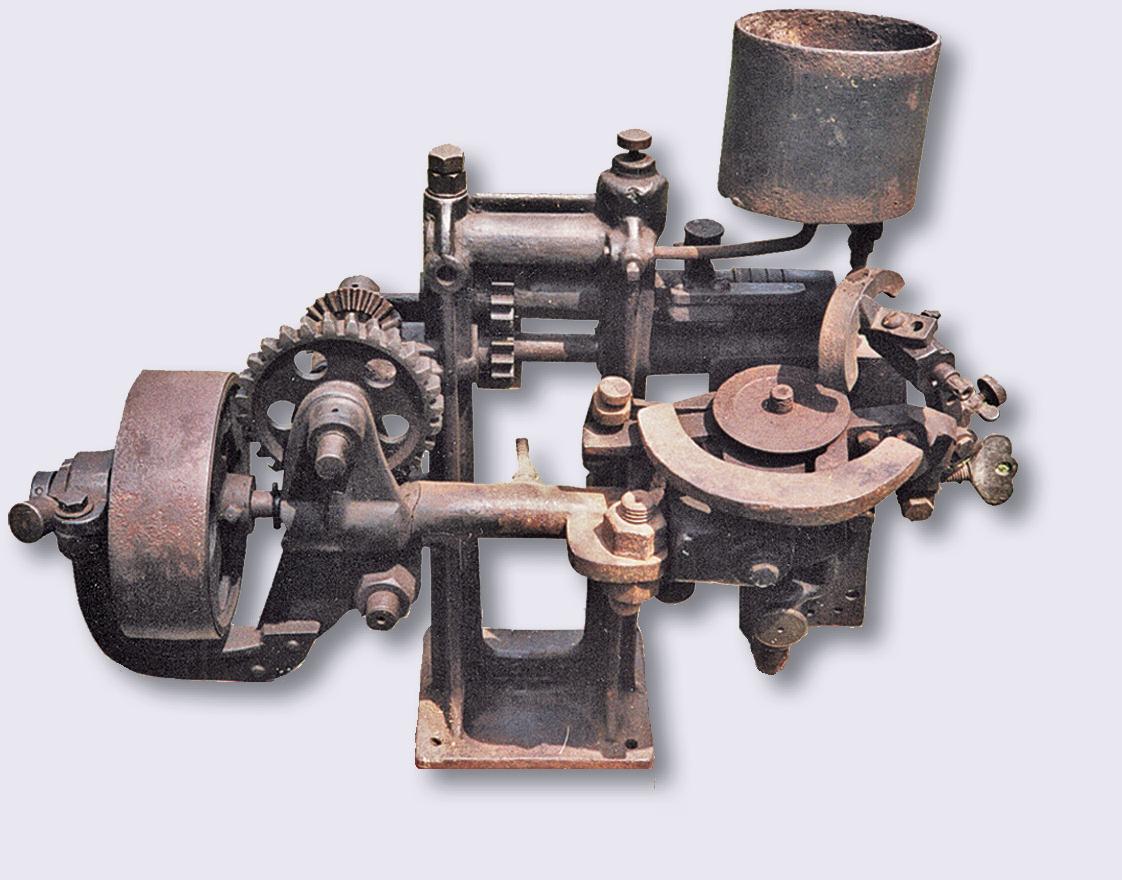

Winger’s windmill-powered grain grinder. These devices ground very slowly and could be left completely unattended. This undoubtedly had a 1- or 2-bushel hopper attached to the small hopper on the mill.

Hay and fodder fork. One reader explains that “The idea is to open the tines or jaw, thrust it into a shock or pile of hay, then close the jaw and move the material to where you want it. I am glad I never

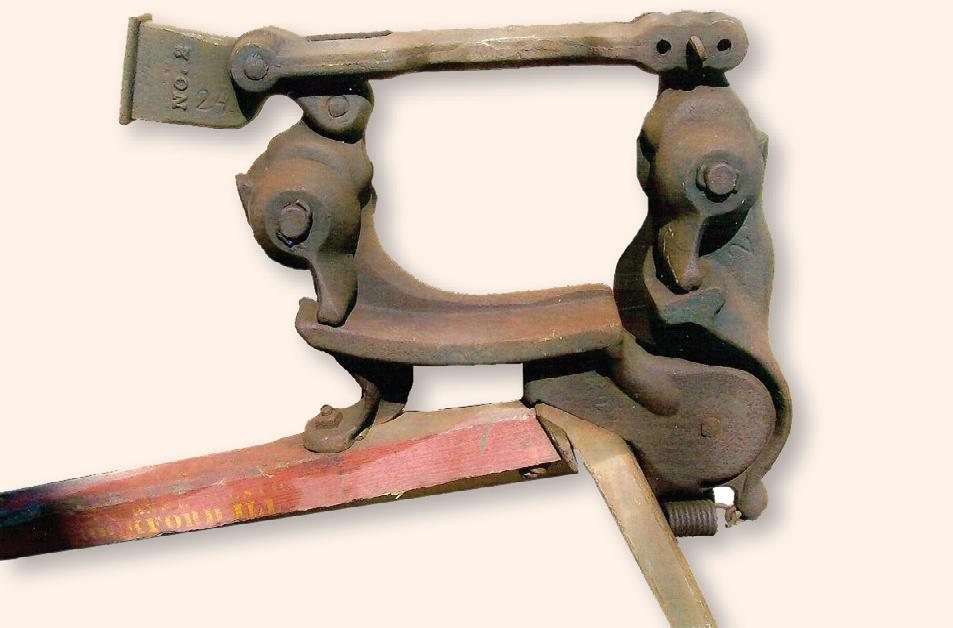

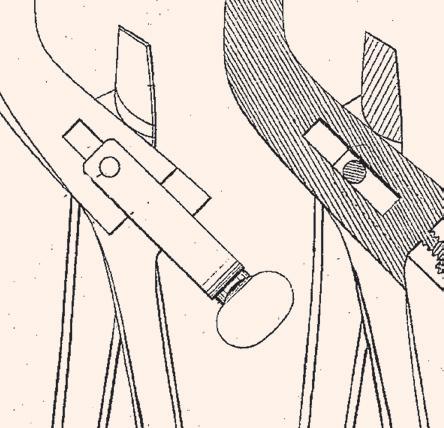

The clamps are clearly shown at the high end of the drag saw. “It is the end piece of a one-man buck saw that holds on to the log,” explains one reader. “It actually works backward: When you pull up on it, it opens up instead of closing like you would think.”

This grader separated kernels by sizes for use as seed in the old plate-type planters. The galvanized hopper was filled with shelled corn and the handle cranked slowly as the seeds dropped through the holes according to size, and into separate buckets.

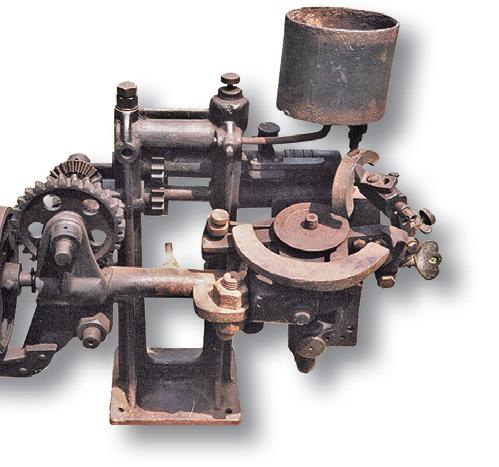

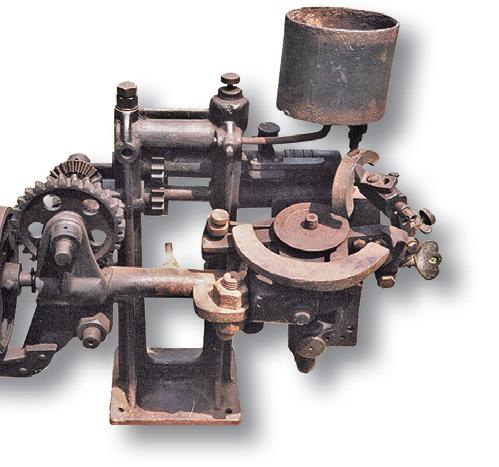

The item is missing several parts, which could be misleading on the use of the tool (sometimes referred to as a green bone cutter). It was used to flake bone into a meal used for poultry feed.

Farmers discovered at the end of the 19th century that feeding flaked bone to hens produced healthier eggs with thicker shells. This is believed to be caused by the extra calcium provided by the bone.

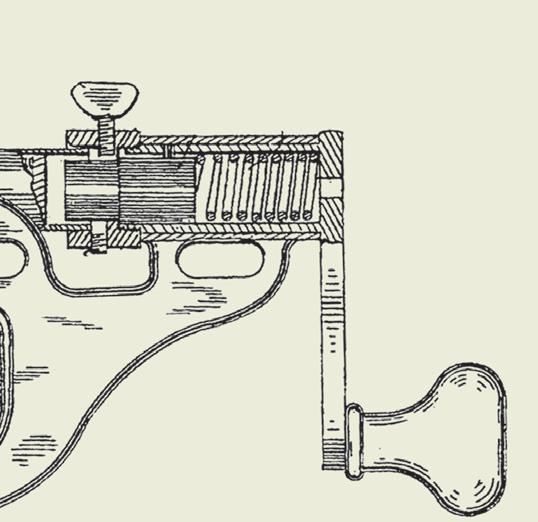

Transmission spring compressor for a Model T Ford. According to a similar patent (no. 1,433,944), “All of the springs are simultaneously compressed and held and the

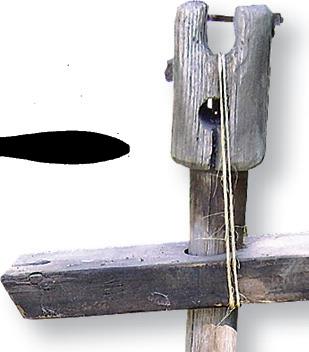

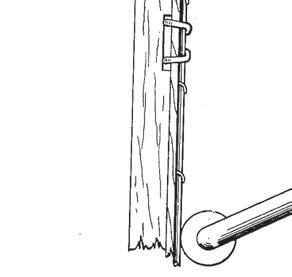

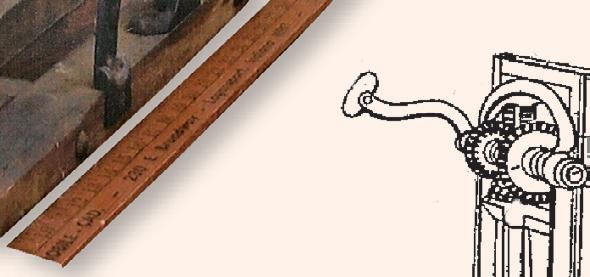

This wrench was used to tighten the nut between the spokes on wooden buggy wheels. According to an 1888 patent granted to John Byrne of Sharon, Wis., “The object of my invention is to provide an improved tool or device for applying and removing tire bolts to or from the wheels of vehicles ... to clamp the bolt to hold it from turning and to revolve the nut for the purpose of threading it.”

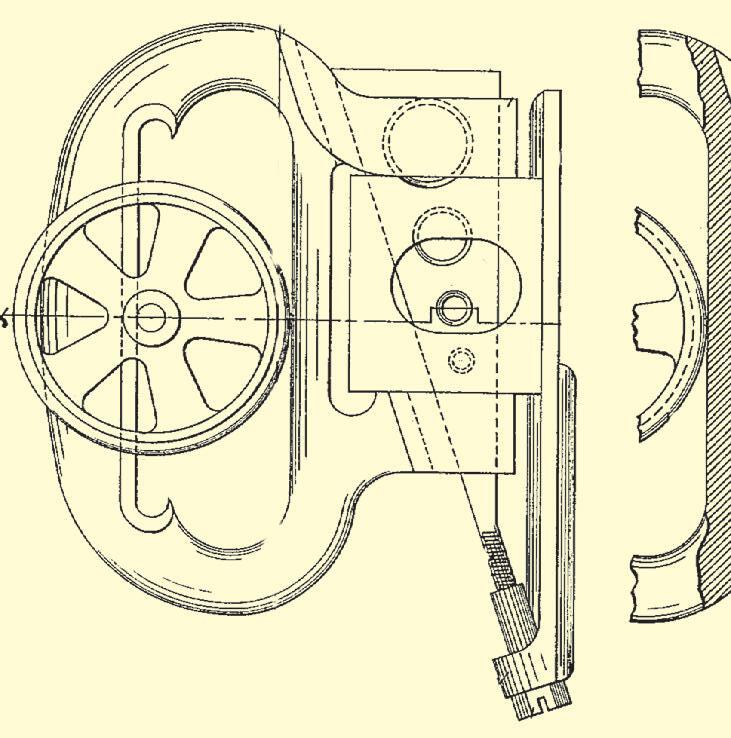

This device was used to take wrinkles out of car fenders and was, quite likely, one of a set. This piece, identified on the patent as a metalworking device used to remove dents on fenders, was patented on June 20, 1944, by Vernon E. Robbins. The patent drawing shows the device at work, with a piece of metal inserted between the “anvil” and the wheel.

Used to tighten the spindle nut on a carriage or buggy wheel. The hooks on the ends attach to the spokes, holding the socket on the nut. The wheel is turned, effectively tightening the nut. Its key feature is the springiness of the wrench. According to an 1890 patent awarded to Frederick Wegner of Three Rivers, Mich., “It is the object of my improvement to provide a lateral springiness on the part of the wrench, so that on the nut reaching its seat and suddenly stopping the revolution of the wheel this lateral springiness will ease the suddenness of the pressure on the side of the spoke.”

Patent 420,981: Carriage wrench. Patent granted to Frederick Wegner, Three Rivers, Mich., Feb. 11, 1890.

Michigan has long been the country’s transportation leader. Thanks to its rich forests and plentiful lumber, Michigan was an obvious choice for wagon manufacturers looking to set up shop. By the 1890s, more than 125 wagon companies employing about 7,000 workers called Michigan home. 75 percent of the companies were located in seven communities: Detroit, Flint, Grand Rapids, Jackson, Kalamazoo, Lansing and Pontiac.

left front leg: “MOLES PAT.” On right front leg: “NOV. 4 1877.”

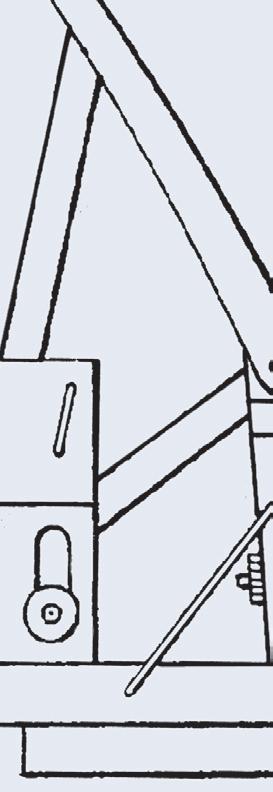

This device was used to tension the steel tire around the wooden wheel for some buggies and wagons. “Wooden wheel wagons had a band of metal around the outside,” one reader explains. “This had a two-fold purpose: First, it kept the wooden felloes from coming apart and separating from the spokes, and second, the iron band (called a tire) wore much better than wood. I had two tire shrinkers, but a couple of high school boys sold them for salvage.”

“Wooden wheels on wagons would get dry in summer heat,” explains another reader. “The wood shrunk away from the iron tire and the tire would come off the wheel. Blacksmiths would place the tire in a forge and get it very hot. The tire shrinker would be opened by a wooden handle fitted into the tool. The hot wagon tire was placed in the shrinker and the handle was pulled down to reduce the diameter of the tire. The tire was replaced on the wooden wheel, which would be tighter than before. Some old-timers would back their wagons into a pond, leaving them overnight to tighten the tires.”

This device was used to take valves out of large cylinder heads. As several sharpeyed readers noted, a piece of this one is missing: a 12-inch chain with cast iron hook on the end.

Patent

Nov. 6, 1877.

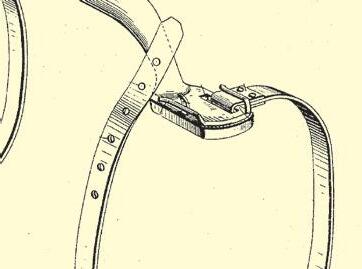

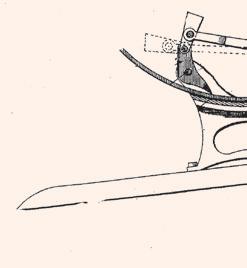

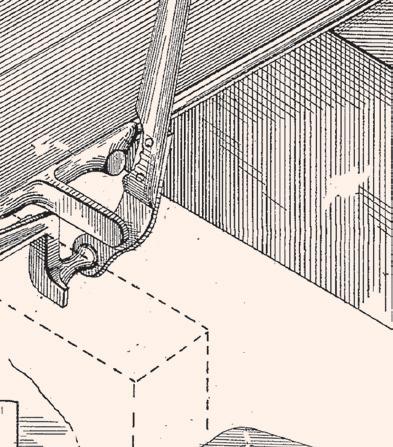

This is a securing bracket from an early 1920s convertible touring car. “(The bracket) is used to secure the top bows of an early ‘20s/late-teens touring car,” one reader says. “When the top is lowered, the bows are latched into these brackets –one on each side – at the upper rear corners of the car. I have a ‘27 Chevy touring car, and this item looks almost identical to the ones in my car.”

H. Nelson Jackson made the first transcontinental road trip in the spring of 1903 in a Winton touring car. People doubted long-distance automobile travel was possible, but Jackson proved it could be done. Beginning in San Francisco, Jackson and mechanic Sewall Crocker made the journey through the rough, mostly road-less west and arrived in New York City 64 days later. The car is now on display at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of American History.

Marked with the number opposite the handle. “J C Moore & Co., Racine, Wis” handle side.

22.

The “speedy wrench” was used on Fords for transmission cover and engine base bolts, one reader says.

This jack is one from a set of four. The jack was particularly useful in storage of early cars, an easy alternative to putting the car on and off blocks.

Patent 1,400,226: Wrench. Patent granted to Horace R. Milan, Columbia, Tenn., Dec. 13, 1921.

Below: The Speedy wrench, “very extensively used by Ford men,” one catalog notes.