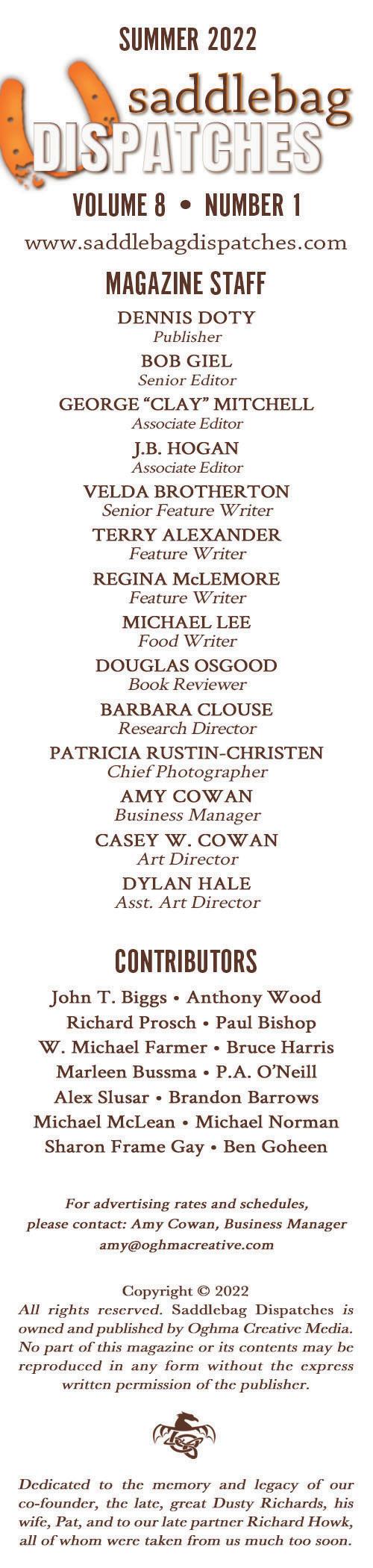

No submissions for our Winter 2022 Issue will be accepted. It will be a special edition dedicated entirely to the memory of our late co-founder, Dusty Richards.

SaddlebagDispatches is seeking original, previously-unpublished short stories, serial novels, poetry, and non-fiction articles about the West. These will have themes of open country, unforgiving nature, struggles to survive and settle the land, freedom from authority, cooperation with fellow adventurers, and other experiences that human beings encounter on the frontier. Traditional westerns are set west of the Mississippi River between the end of the American Civil War and the turn of the twentieth century. The western is not limited to that time, however. The essence is openness and struggle. These things are happening now as much as they were in the years gone by.

QUERY LETTER: Put this in the e-mail message: In the first paragraph, give the title of the work and specify whether it is fiction, poetry, or nonfiction. If the latter, give the subject. The second paragraph should be a biography between one hundred and two hundred words.

MANUSCRIPT FORMATTING: All documents must be in Times New Roman, twelve-point font, double spaced, with one-inch margins all around. Do not include extra space between paragraphs. Do not write in all caps, and avoid excessive use of italics, bold, and exclamation marks. Files must be in .doc, or docx format. Fiction manuscripts should be in standard manuscript format. For instructions and examples see https://www.shunn. net/format/story.html. Submit the entire and complete fiction or poetry manuscript. We will consider proposals for non-fiction articles.

OTHER ATTACHMENTS: Please also submit any pictures related to your manuscript. All photos must be high-resolution (at least 300 dpi) and include a photo caption and credit, if necessary.

Manuscripts will be edited for grammar and spelling. Submit to submissions@saddlebagdispatches.com with your name in the subject line.

THIS IS A GREAT time to be a Western writer or reader. Never have there been so many talented and accomplished western writers to choose from. Our genre is healthy and vibrant despite the premature announcements of its passing.

However, we do have a major challenge ahead of us. There are few western readers and even fewer writers under the age of forty. This doesn’t bode well for the future of the western genre. So, I am making it a priority to do whatever I can to bring our beloved genre to a younger audience.

I challenge all of you to introduce one new reader to the western genre and, if you are a writer, to find, recruit, and mentor at least one author under the age of thirty-five. This is no easy undertaking, but I believe it is vital to the long-term survival of our genre. I hope you will join me. So, if you are an unpublished western writer or wannabe western writer under age thirty-five and would like a mentor, feel free to drop me a note with a short sample of your writing at dennis@ oghmacreative.com.

Now, for the announcement many of you have been waiting for, but before we get to that, I’d like to once again thank our fine panel of independent

award-winning judges for selecting the winner and runner-up in our Second Annual Mustang Award for Western Flash Fiction.

L.J. Washburn is a talented western writer. L.J. received the Private Eye Writers of America paperback original award and the American Mystery award for the first book in the Lucas Hallam Mystery series, Wild Night. She also won the Western Fictioneers Peacemaker Award for the short story “Charlie’s Pie” and was nominated twice more for her stories.

Richard Prosch’s work has appeared in Wild West, Roundup, Boys’ Life, and Saddlebag Dispatches magazines. He won a Spur Award from Western Writers of America for Best Short Fiction for his story, “The Scalpers.”

Therese Greenwood won the Spur Award from the Western Writers of America for her story “Buck’s Last Ride” in Kill as You Go, her short story collection from Coffin Hop Press of Calgary, Alberta. She is a three-time Finalist for the Crime Writers of Canada’s Award of Excellence. She won the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation’s Mystery Flash Fiction Contest and her short fiction has appeared in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine.

Thank you, judges, for taking the time to read and evaluate all the entries this year.

And now, the winner of our Second Annual Mustang Award for Western Flash Fiction is “Yellow Town” by Bruce Harris. Congratulations, Bruce! Also appearing in this issue is our first runner-up story “Lonestar Hate” by Brandon Barrows. Congratulations to you, too, Brandon. Unfortunately, we simply don’t have enough room in this issue for all five finalists, but the other three merit a mention as well. In third place was “Deadman’s Stand” by David Bowmore. W. Michael Farmer took fourth place with “A Man of His Word,” and Allison Tebo was a very close fifth with her story, “Blaze of Memories.” Congratulations to all of you.

You’ll notice we’ve added a new column this time out, “The Book Wagon.” It will be here that the newest member of our staff, Doug Osgood, a talented writer in his own right, will review a trio of Western books— fiction and nonfiction—for each new issue moving forward. He’ll give a short synopsis of each book, along with his overall impressions, then rate each on a scale of one to five gold nuggets. If you’re a Western writer or publisher and would like to submit a book for review, send your request to dennis@oghmacreative.com and we’ll get it set up on Doug’s reading list.

At last year’s Will Rogers Medallion Awards, outgoing Director Charles Williams mentioned to us how desperately we needed to add some Visual Humor to our lineup. It was a suggestion we couldn’t refuse. So in addition to “The Book Wagon,” we’re proud to present our other new feature debuting this issue, “The Punny Express,” a humorous, Western-themed cartoon strip written by Saddlebag Dispatches Associate Editor George “Clay” Mitchell and illustrated by Assistant Art Director Dylan Hale.

Finally, we’re proud to offer our latest issue of Saddlebag Dispatches. We have modern gunmen, heroic horses, classic rodeos, land-grabbing mobsters, two amazing Apache women, and much more. So, what are you waiting for? Turn the page, pull up a log to sit on, pour a cup from the camp pot, and get to reading.

DENNIS DOTY PublisherCopyright

MATHEW GARTH SPENT THE last twenty years keeping Thomas Dunson’s cattle empire thriving. Now, middle-aged with two sons of his own, an especially harsh winter has devastated herds throughout Texas, even reaching deep into southwest Texas to Garth’s own herd. Debts old and new force him to risk storms and rustlers to drive a herd to Dodge City. Along the way, he must battle old enemies, face old secrets, and even fight family, all to save the Dunson legacy.

Two elements are critical for iconic westerns— settings and action. In Return to Red River, setting is as much a character as the Garth family, and Boggs paints such vivid scenes the reader might reach to wipe sweat or shiver along with the characters. In addition, the author uses all the classic action scenes— saloon fights, stampedes, gun battles, and more, all with the attention to detail that sets the reader front and center. Yet, the real keys to this novel are the relationships. Human passions are all on display, driving the plot, and Boggs handles them with the dexterity of a fine craftsman. Every word, every scene, tightens the screws on Mathew Garth.

With this revisiting of the classic movie, the author proves yet again why he is the modern master of the western genre. The plot spins and bucks more than a rodeo bull and leaves the reader gasping for

breath long after the final page. Place this one to the front of your bookshelf. You’ll want to read it again and again.

Rating: 5 Nuggets (out of 5)

ReturntoRedRiver by Johnny D. Boggs

2016, Published by Kensington Publishing Corp.

ReturntoRedRiver by Johnny D. Boggs

2016, Published by Kensington Publishing Corp.

TEDDY ROOSEVELT BELIEVED IN preserving the West for all Americans. To that end he set aside millions of carefully chosen acres among the vast tracts of empty wilderness. Then he placed them in the care of Gifford Pinchot, head of the newly formed forest rangers. Teddy’s own party revolted against him to stand with powerful, wealthy timber and railroad barons seeking more—more land, more money, and more power. By 1910, with Roosevelt out of office and his hand-picked replacement, Taft, proving to be weak-willed and more interested in his golf game than politics, the wealthy business interests seemed to be winning. Until August 20, 1910.

A windstorm turned several small drought-fueled fires into a raging conflagration unlike anything any living man had ever seen. To the wealthy railroad and timber executives, this seemed a Godsend. Destroy the forests the rangers protected and eliminate their need. Then the acreage could be reclaimed for the sake of big business.

The narrative is engaging and entertaining despite the author spending significant portions of the text explaining the history of the war between preservation and big business. The impact of Roosevelt’s presidency on the preservation movement and his friendship with Gifford Pinchot are covered in depth. Interspersed are heroic stories of men and women who bravely stood against the overpowering flames.

Who wins? The barons rejoiced. But in the end, the ranger’s defeat turned to victory. This is a story of hope, bucking the odds and the power of public sentiment. In light of even more recent history, this book needs to be shouted from the mountaintops.

Rating: 4.5 Nuggets (out of 5)

Jack Wills wants is to live out his string on his Lucky Five ranch with his aging dog, Thor, longtime friend, Rudolph Kilgore, and adopted son, Jordon Jackson. Until a young woman, Sierra Wills, shows up at the ranch with a wild story about being Jack’s granddaughter and begging help to recover her herd of horses stolen by the same Comancheros who murdered Jack’s son—a son he never knew existed. A long evening of conversation with Sierra leads retired ranger Wills to believe her story. Subsequently, he agrees to put together a team to recover her stolen herd.

The author does a satisfactory job of exploring the universal issue of ageing and tying it to the plot. Sentimentality, aches, bodily ailments, and the desires for progeny’s future push this story forward. Schwab also handles fight scenes well—sufficient details to allow the reader to paint a vivid picture without dragging at the story. However, billed as an adventure yarn, I was disappointed by the shortage of edge-of-seat suspense or rip-snorting action. Even the relationships, which take front and center throughout, felt rushed, robbing the book of the conflict and tension they should add. Thus, the telegraphed ending, which could have been both surprising and inevitable, fell flatter than a cowboy flapjack and lacked the kind of shocking surprise needed for a truly satisfying read.

Overall, while Old Dogs was worth a quick read, it doesn’t stand up to the best the genre has to offer, and I wouldn’t read it twice.

Rating: 3 Nuggets (out of 5)

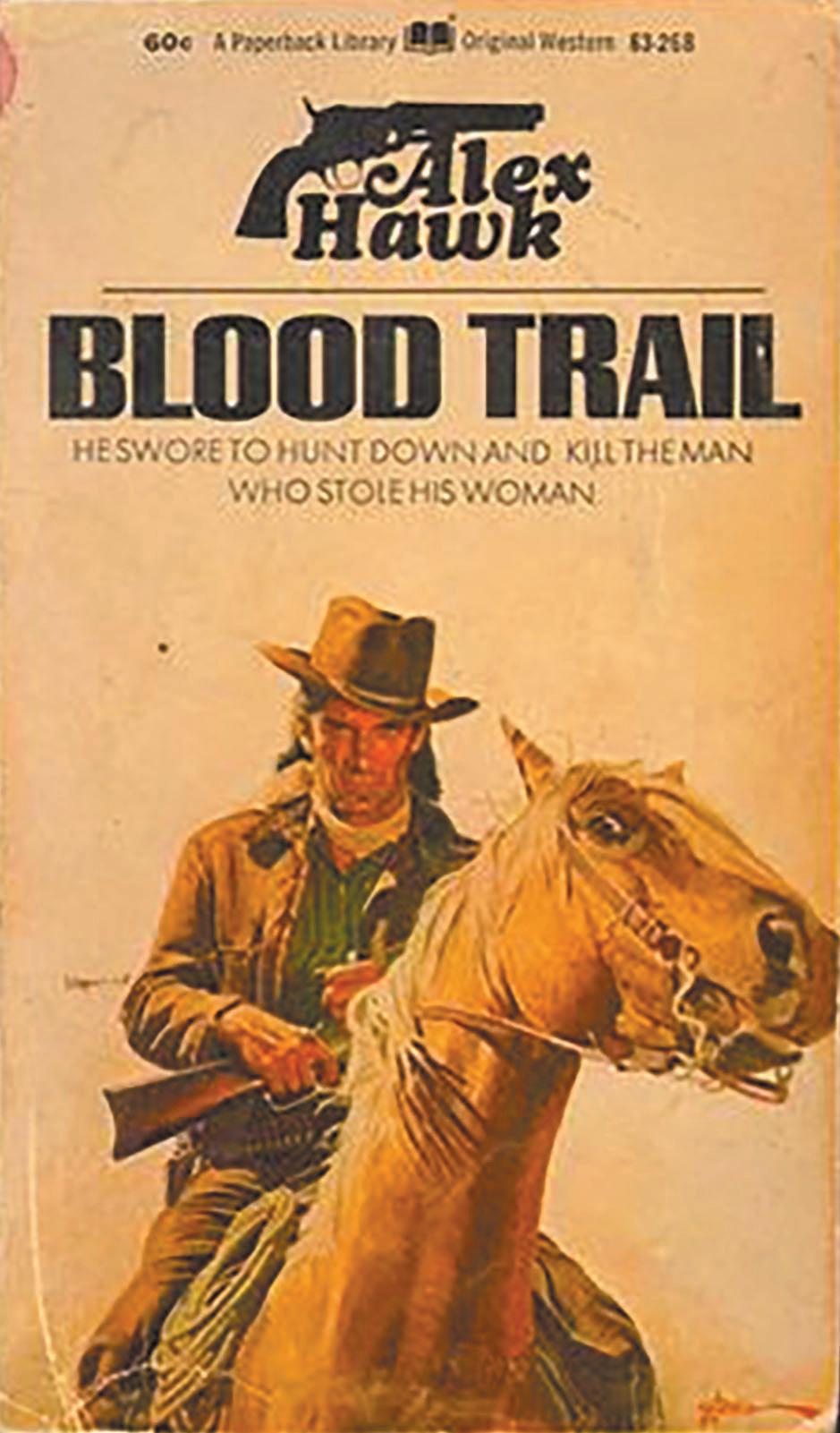

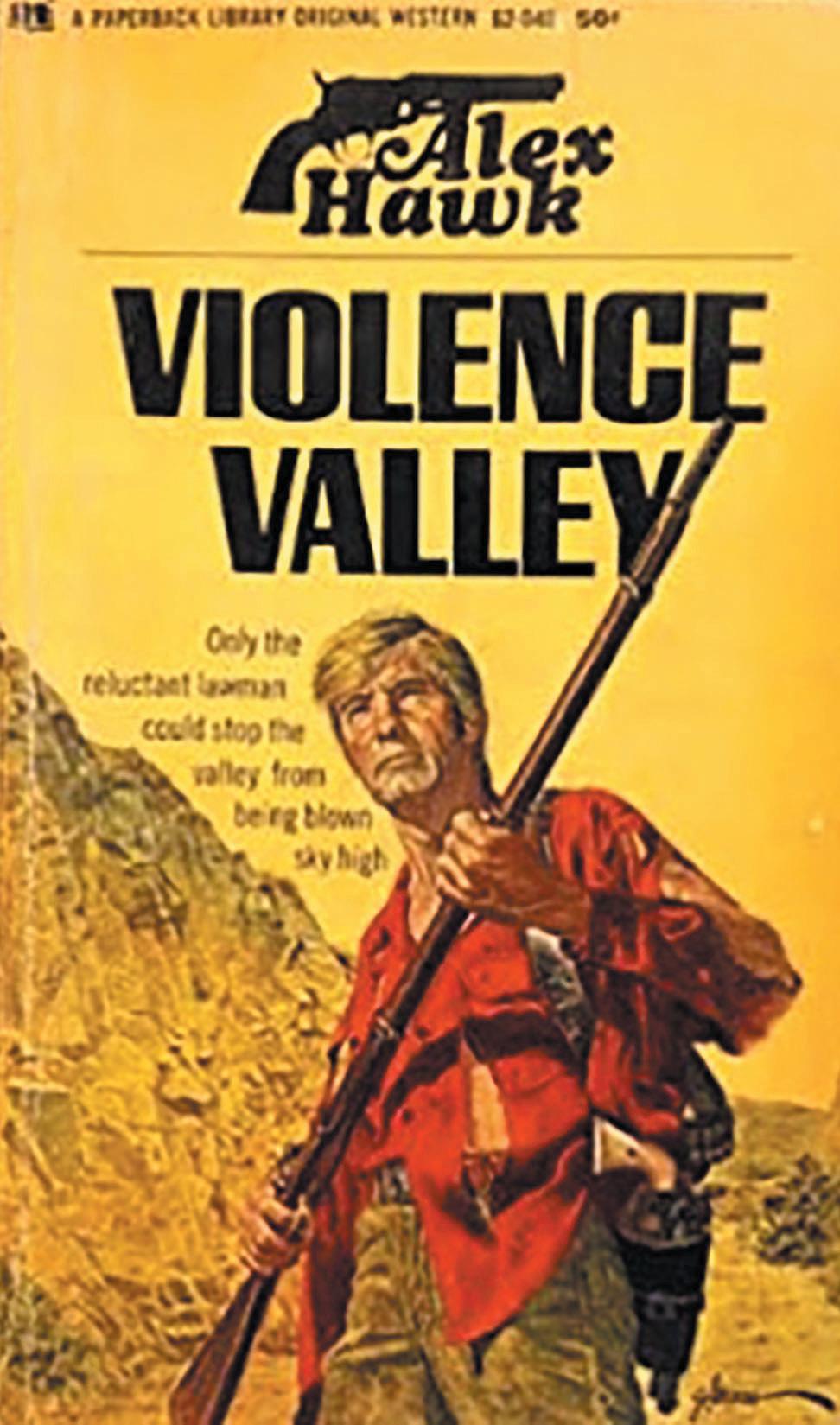

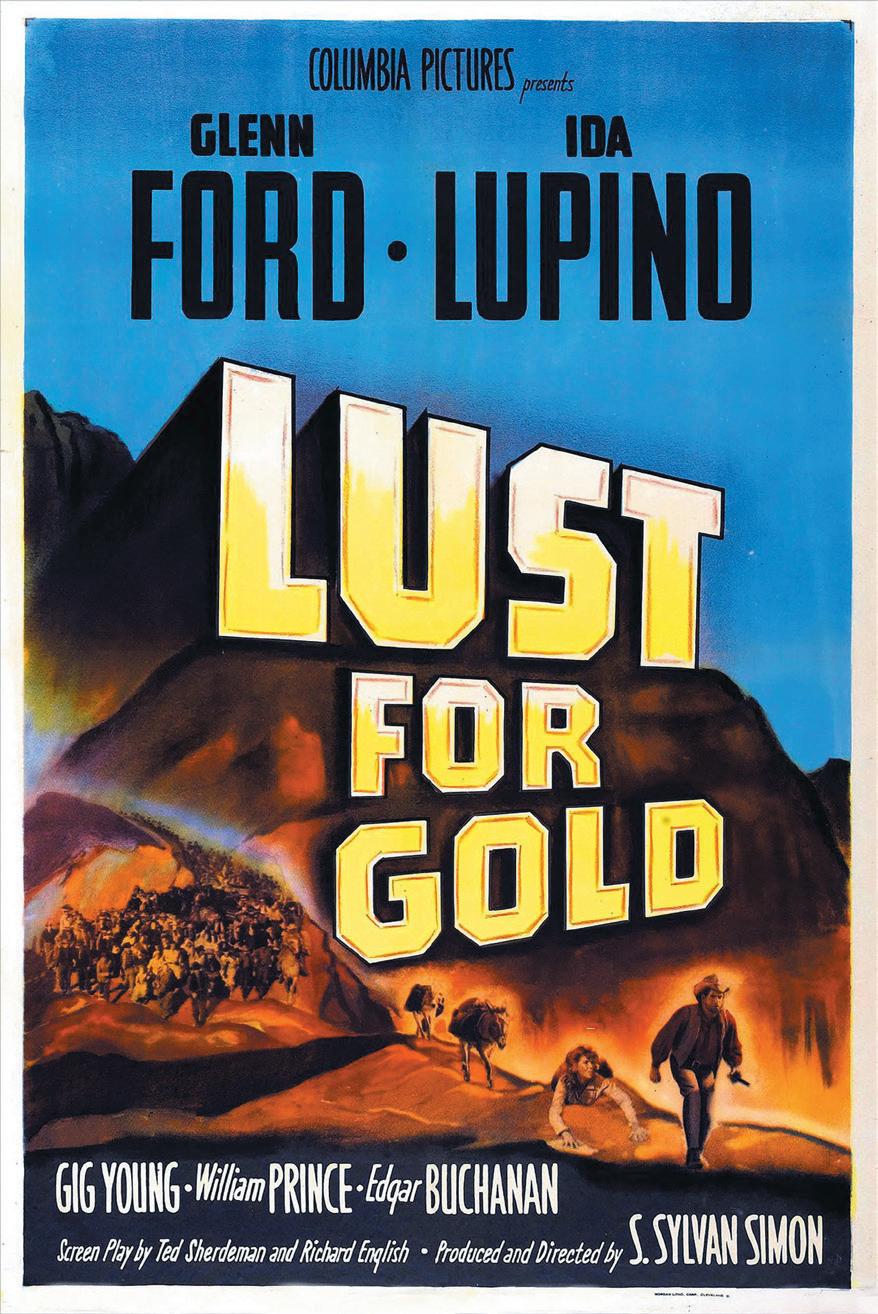

BETWEEN 1968 AND 1971, Paperback Library published twenty slim western novels under the house name Alex Hawk. They were uniformly packaged with cool western pulp style illustrations on the covers. I really dug both the aesthetics of the series and the stories themselves. The books in the series are akin to eating Lay’s Potato Chips—you can’t read just one—which meant when I discovered the first three in a used bookstore and finished reading them, I had to track down all twenty. That was the easy part. The hard part began when I tried to identify the actual authors, which has turned out to be harder than figuring out the wordslingers writing behind non-disclosure agreements for the William Johnstone brand. A big part of the reason it’s harder is because the Alex Hawk books were written fifty years ago, and whatever sign left behind for a tracker to follow has been covered over by the sands of time.

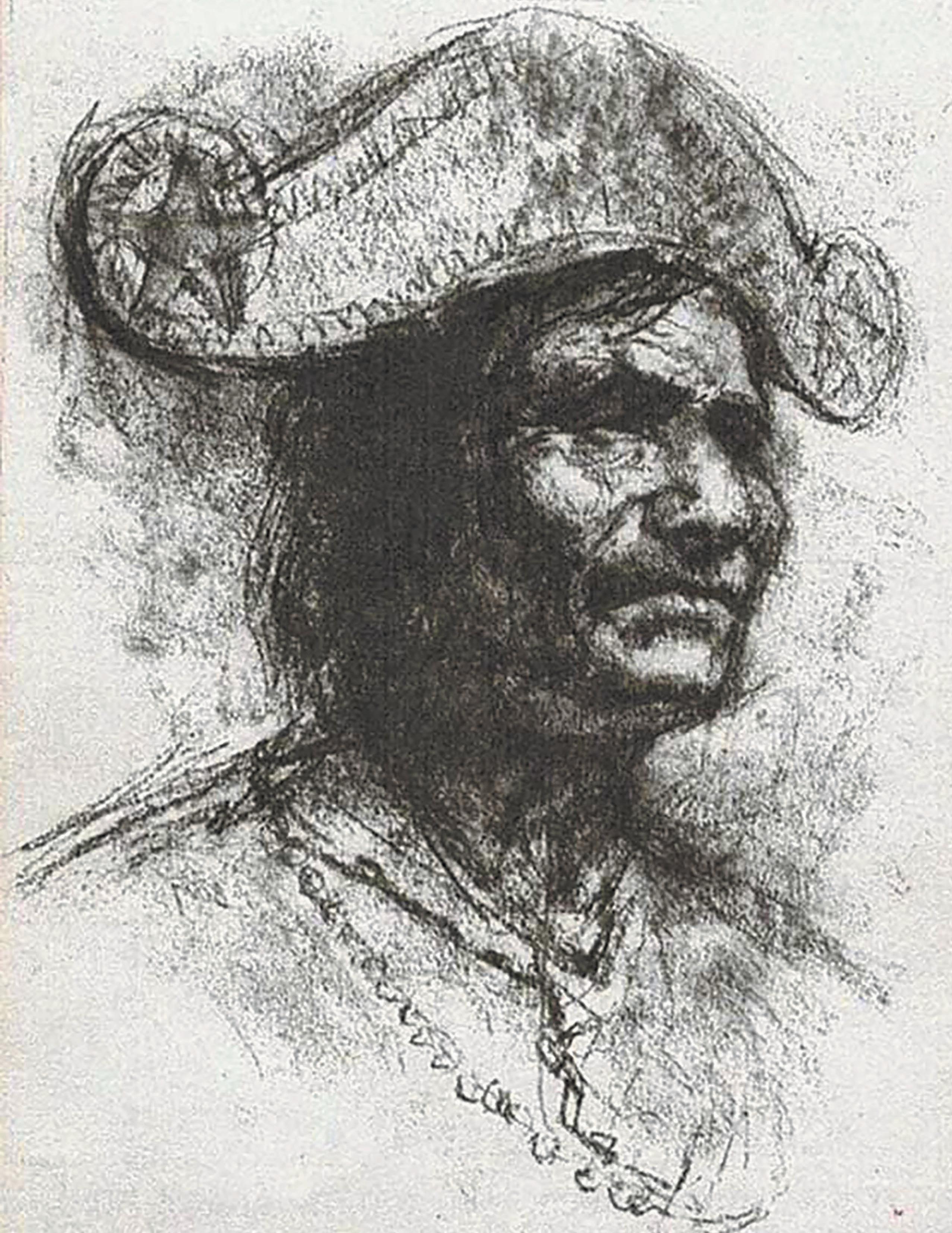

The indications are there were at least ten writers and perhaps as many as fifteen behind the Alex Hawk house name. Some may have written only one title, some two or three, and one at least five. All the books were stand-alones featuring different heroes, with the exception of three books featuring the character of half-breed sheriff Elfego O’Reilly, written by a big name wordslinger who I’ll unmask in a second— which puts a picture in my head of a guy in a mask pounding away furiously on his battered Olivetti, but perhaps that’s a little farfetched.

There’s no doubt I’ve spent more time banging my head against search engines trying to figure this out than the mystery is actually worth. However, I did manage to discover there was some heavyweight western wordslinging behind the pseudonym as well as some lesser lights.

The problem of author identification starts with the copyright for all books assigned to Coronet Communications. There is no indication of the actual authors either on the title page inside the books or in the US Copyright listings. Any information pertaining to Coronet Communications has disappeared into the ionosphere along with the company itself.

If I was to make an educated guess, it wouldn’t be unusual for a company like Coronet Communications to act as a book packager. The most likely scenario is Paperback Library asked Coronet to create a western series expecting Coronet to find the authors for the series, edit the books, and then turn them over to Paperback Library to publish.

However, a packaged series being built around a pseudonym—Alex Hawk—instead of a recurring character would be very unusual. This begs the question, did Paperback Library come up with the Alex Hawk house name—which would be most likely—or did an editor at Coronet pull it out of thin air? It also makes you wonder if Alex Hawk was actually supposed to be the name of the series character, and somewhere in the process it ended up as the shared author alias.

It all could have been a miscommunication between Paperback Library and Coronet, but that’s another mystery about these books which will never be solved at this late date. As it is, this is a mystery only Sheriff Minutia would worry about solving, but again these are the kinds of details hardcore genre fans thrive on, right? I am possibly confusing western fans with Star Trek fanatics, a mistake that might lead directly to a Six-Gun Justice Podcast cosplay contest.

But let’s get back to making a long story longer... I have no doubt the books were contracted as work-forhire gigs. These would be contracts accepted by writers needing to make a quick buck by turning out in a week or two what in reality was a fifty thousand word story—too long to qualify as a novella but barely long enough to be called a novel. The books published under the Alex Hawk pseudonym were stripped down, guns blazing, fists flying actioneers that would have been right at home in the best of the old school western pulps.

My favorite Alex Hawk book is SavageGuns, which made sense when I learned it was written by Brian Garfield. With some more digging, I was able to discover the highly respected Elmer Kelton also donned the identity of Alex Hawk when he penned Shotgun Settlement. Kelton would later republish Shotgun Settlement under his own name using the slightly revamped title, Shotgun. It’s hard to say if Kelton officially got the rights back for Shotgun Settlement, or Coronet Communications went so completely defunct the issue of rights conversion was a moot point. However, Kelton was an upright guy, so I’m going to assume the best and say the rights reverted to him at some point—unusual for a work for hire gig but possible.

Checking several bibliographical sources for Kelton and Garfield, I confirmed Alex Hawk was listed as a pseudonym for both. The sources further confirmed

Savage Guns as Garfield’s Alex Hawk title and Shotgun Settlement as Kelton’s. Since there were no other Alex Hawk titles listed for either author in their bibliographies, I think it’s safe to assume their tenure as Alex Hawk was confined to a single outing.

Hauling out my copy of Hawk’sPseudonyms, a regular go-to reference work, I checked the listing for Alex Hawk. Both Garfield and Kelton were again confirmed along with several other Alex Hawk stand-ins. These included well-known western wordslinger Giles Lutz

and two other lesser-known scribes—Johanos Bouma and Joseph Chadwick. This was a definite step forward in solving the enigma of Alex Hawk. However, there was no indication of which Alex Hawk books Bouma or Chadwick had written.

My next stop was Twentieth Century Western Writers—another fantastic reference. The entry for Giles Lutz was a bonanza crediting him with five Alex Hawk titles—ToughTown,DriftersLuck, and the three books I mentioned earlier featuring the character of Elfego O’Reilly—Mex,HalfBreed, and MexicanStandoff. Frustratingly, the entries for Bouma and Chadwick did not list Alex Hawk as a pseudonym, nor did any Alex Hawk titles appear in the listings of their works—but more on them later.

While researching the Western TV tie-ins episode of the Six-Gun Justice Podcast, the name Owen Dean —a pseudonym used by the prolific Dudley Dean McCaughy —was credited on many of the western tie-in novels. I was looking through his extensive bibliography when I came across two books— PecosSwap and BloodTrail —which he wrote as Alex Hawk. Bingo! Another wordslinger unmasked from behind the Alex Hawk pseudonym along with two more titles with solid attribution.

At this point, my Alex Hawk dance card is filling up. Garfield and Kelton each wrote one identified Alex Hawk title. Owen Dean wrote two identified titles; and Giles Lutz is the top scorer with five identified Alex Hawk titles.

This leaves Johanos Bouma and Joseph Chadwick identified as authors—but not the books they wrote or how many—and eleven titles still not matched to authors. It was time for a deep dive into the mysteries of the Internet. My search for Johanos Bouma turned up nothing of interest. However, when I searched for J. L. Bouma, it came back with the cover of the Danish edition of McGee under the title Haevntorst. Score one for Google. I kept digging and found a reference to the Danish edition for Gunslick, with Joseph Chadwick behind the Alex Hawk pseudonym.

There were a number of other Alex Hawk titles published in German, Swedish, and Danish editions but no further information as to the authors disguised as Alex Hawk. The titles had also

been changed, and it was difficult to match them to the original titles. I have my suspicions Wayne D. Overholser, Roy Hogan, and T.V. Olsen took turns as Alex Hawk, but I was unable to uncover any solid confirmation or any indication as to which books they may have penned.

Currently, the score stands at six authors identified along with the eleven titles they wrote as Alex Hawk— leaving nine titles with unidentified authors. The trail may be cold, but I am relentless, and the search goes on. If anyone out there knows any more information pertaining to the Alex Hawk books, please drop Sheriff Minutia an email at www.sixgunjusticewesterns@gmail.com.

Savage Guns—Brian Garfield Shotgun Settlement—Elmer Kelton Mex—Giles Lutz Half-Breed—Giles Lutz —Giles Lutz Trouble Town—Giles Lutz Drifter’s Luck—Giles Lutz Pecos Swap—Owen Dean Blood Trail—Owen Dean McGee—Johanos Bouma Gunslick—Joseph Chadwick Blizzard Herd

Gunslammer Ruthless Return Violence Valley High Vengeance Hidden Hills

The Last Bullet

PAUL BISHOP is a novelist, screenwriter, and western genre enthusiast, as well as the co-host of the Six-Gun Justice Podcast, which is available on all major streaming platforms or on the podcast website: www. sixgunjustice.com/

His voice is like a rusty hinge that swings a gate in rain.

His voice is like a rusty hinge that swings a gate in rain.

He walks a cowboy strut on legs that protest and complain.

He walks a cowboy strut on legs that protest and complain.

One finger has gone AWOL since a dally cut it clean.

Deep creases near his eyes are maps to all the things he’s seen.

One finger has gone AWOL since a dally cut it clean. Deep creases near his eyes are maps to all the things he’s seen. There’s more hair on his hands than what still sprouts upon his head.

There’s more hair on his hands than what still sprouts upon his head. His sweat-stained, battered hat sits square as rain and snow are shed.

Work starts before the sky sloughs off the stars like flaky skin and doesn’t end until another night has stumbled in.

His sweat-stained, battered hat sits square as rain and snow are shed. Work starts before the sky sloughs off the stars like flaky skin and doesn’t end until another night has stumbled in.

He eats two meals a day out of an ancient cast-iron pot that Cookie serves as culinary torture, though it’s hot. The ground has been his mattress, cheap, available, and near. It’s served him in the heat and cold throughout his long career. The work is hard and dang’rous, pays a dollar every day.

He eats two meals a day out of an ancient cast-iron pot that Cookie serves as culinary torture, though it’s hot. The ground has been his mattress, cheap, available, and near. It’s served him in the heat and cold throughout his long career. The work is hard and dang’rous, pays a dollar every day.

Sometimes the boss will let him take a calf in lieu of pay.

Sometimes the boss will let him take a calf in lieu of pay. A cowboy’s life’s romantic ’tween the covers of a book, but he needs grit and gristle if you take a closer look.

He proves his worth on horseback, lives his life in dirt and grime. Although he works for others, they own nothing but his time.

A cowboy’s life’s romantic ’tween the covers of a book, but he needs grit and gristle if you take a closer look. He proves his worth on horseback, lives his life in dirt and grime. Although he works for others, they own nothing but his time.

THE CABIN WAS ONCE some homesteader’s attempt at building a dream. Now, the porch was half-collapsed, and the moss-covered roof wasn’t far behind. Smoke curled from the tin chimney, though, and a horse with a distinctive star-shape on its flank sheltered beneath an eave. The tip was good. Ned Lukas was back in Texas.

“Think it’s him, Sarge?”

“Hush,” I snapped. Stinton’s cheeks colored, but he kept quiet. He took orders and was a fair shot. He’d be a good ranger someday. I still had no use for him. Captain Miller ordered Stinton along for the experience, though, and if it wasn’t for Miller, I wouldn’t be there at all. He was new to the post and didn’t know I shared history with Ned Lukas, didn’t know Lukas killed my sister.

Lukas was a gunman and worse, but his smile could charm rattlers. I only learned Cora knew Lukas from the letter she left, the day they disappeared below the border. His gang pulling a bank hold up that same morning wasn’t coincidence.

It was two years before I had news of Cora, and then it was too late. She died in childbirth, abandoned

by a man she loved in a country whose language she couldn’t speak. The thought still ripped my guts like bullets. It was time to return the favor.

“Sit tight.” I rose from a crouch, slipping the thong from my revolver.

The recruit looked closely at me. “Sir?”

“I’ll handle this alone.”

There was an odd light in Stinton’s eyes. “Captain Miller ordered me along with you, Sergeant Herndon.” His fingers toyed with the butt of his own gun.

White-hot fury flared inside me. I had waited so damned long. Who was this snot-nosed kid to take my moment away?

“Miller’s not here,” I said tightly.

Stinton shook his head. “Sorry, sir, but I’m coming.”

“Fine, then.” I couldn’t hide my anger, but every moment wasted was another Lukas might slip away or get the drop on us. I’d just have to deal with Stinton, too.

Quietly, we approached the shack. At the crumbling porch, Stinton turned. I mouthed, “Easy now,” gesturing for him to take the lead. Stinton nodded and lifted his .45 from its holster. Before he could take another step,

I brought my Colt smashing down behind the rookie’s ear. He moaned softly and collapsed.

“Sorry, kid, but this is my showdown,” I whispered.

I waited, chest tight and palms sweating, listening for signs Lukas heard. Satisfied he was still unaware, I moved onto the porch, wary of the slightest creak. Please let this be the end, I prayed.

My heel snapped the half-rotted door right off the hinges. A flurry of motion erupted as Ned Lukas sprang from a bunk built into the wall and toward a gun-belt hanging nearby.

“Hold it!”

The outlaw froze. Recognition came into his face.

“That’s right, Ned. It’s Mike Herndon–Cora’s brother. I finally found you.”

Lukas was stricken. “Now, just wait—”

“Shut up. Coming back here is the last mistake you’ll make,” I told him, my thoughts racing so fast I was dizzy. After imagining this moment a million times, now I couldn’t remember how it was supposed to go.

Lukas’s Adam’s apple bobbed, and his eyes flicked to his holstered revolver. “About Cora—”

“Don’t say her name, bastard, and don’t you worry about that gun. It’ll be in your hand shortly.”

Lukas didn’t need an explanation. “That’s murder!”

I tried to smile cold and cruel like in my daydreams, but I just felt sick.

“You’re a lawman! You can’t,” Lukas croaked.

I raised my revolver. “Tell it to the devil.”

Something changed in Lukas’s face then. The mask of fear slipped, showing his anger. Then he did the last thing I expected. He roared like an animal and charged.

His weight hit me like a steam-engine, tumbling us both, breaking my grip on the Colt. It clattered to the floor and skittered across the room.

The impact emptied my lungs, and Lukas’s pounding fists kept me from refilling them. His knee found my groin, and nausea rocked me. Then his weight disappeared. He was going for my gun.

I rolled, and my fingers found Lukas’s ankle as his found my gun. I yanked him back to the floor and slammed a fist into his head. Lukas thrashed, flipping onto his back, then somehow, his hands were around my throat.

Already winded, my lungs burned, and my vision went red. Lukas gasped something, but I only heard my heartbeat against my eardrums. I threw a punch that Lukas shrugged off, but his grip loosened. I managed to tear his hands away, and cursing, he broke free to try again for the fallen revolver.

Lukas lost the gamble. I found my feet, then bulled him against the wall, driving my fists into his kidneys until he crumpled and lay still.

Chest heaving, the room spinning, I wiped sweat from my eyes. I took up my six-gun and aimed squarely at Lukas’s face.

Despite the heat of exertion, I felt cold. I tried to speak, but only a sobbing sound came out. I’d waited long years for this moment only to find I couldn’t squeeze the trigger. What Lukas said—“lawman”— rattled around inside my head.

“Let’s take him in, Sarge.”

Stinton stood in the doorway, hat in hand, massaging his head. “What was the story gonna be, sir? Lukas jumped me, and you shot him?”

“How long have you—”

“Since he tackled you. Some of the fellas told me why you want him so bad, so I didn’t interfere.” Gravely, Stinton added, “I would have, though, if you needed help, sir—or if your trigger-finger tightened much more. Ready to do our duty now?”

I was wrong. Stinton was already a good ranger. And as I realized it, the coldness slowly disappeared. “Let’s get our man into a cell, huh?”

The rookie offered me handcuffs. “Honor’s all yours, sir.”

“Thanks, Stinton… for everything.”

BRANDON BARROWS is the author of the novels Burn Me Out, This Rough Old World, Nervosa, and in the books The Altar in the Hills and The CastleTown Tragedy. He is an active member of Private Eye Writers of America and International Thriller Writers. Find out more about Brandon and his writing on Twitter @brandonbarrows, or on his website, www. brandonbarrowscomics.com.

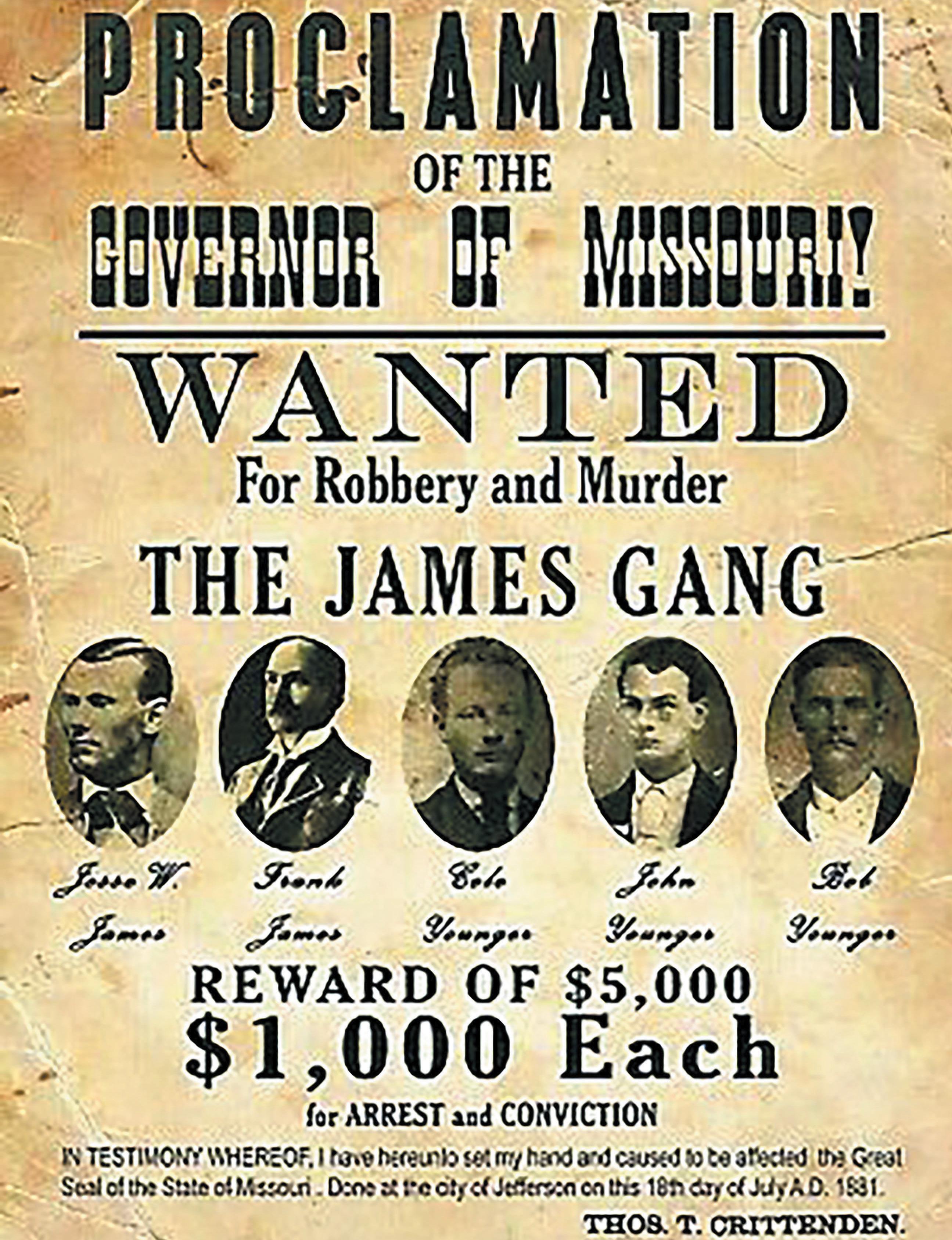

THE BEARDED MAN TACKED a wanted poster alongside the bank’s door, spit, and walked across to the barbershop.

“Mind if I post this here?” he asked. “Been putting ’em up all over town. Last one I got.” He held up the poster. “It’s the guy who killed Sheriff Rance.”

Henry Parker tossed his newspaper aside. “Bobby Brackett, wanted for murder. Sure, put it anywhere you like,” Parker said. “Where you from, stranger? And how do they know this Brackett killed our sheriff?”

“Obliged to ya.” The man looked around the shop for a suitable spot. “Home is out near Fort Kent. I don’t know how they found out Brackett killed Rance. A U.S. Marshal paid me to ride over here and place these posters all around. That’s just what I done. This here’s the last one.” The man tacked the wanted poster on a wall, hammering the final nail with his gun handle. He glanced at the empty chair, rubbed a meaty hand along his cheeks, and said, “If you ain’t too busy, I’ll have a shave and a haircut.”

“Have a seat,” Parker said.

“Shame what happened to Sheriff Rance,” the man

said while hair fell to the floor. “Word has it there was a lot of people who saw the shooting but none of ’em was willing to speak up.”

Parker momentarily stopped cutting. “Ain’t true. Where’d you hear that?”

The man shrugged. “Don’t matter, none. From what I seen, this here Stone Quake looks like a nice town, you know, nice people and all.”

“It is,” Parker said. “Nice and yellow.”

Parker again stopped cutting, “Now just a darn minute, mister. I don’t even know your name, and you come into my shop and insult me and the entire town. I won’t stand for it.”

“Whoa, slow down there. I don’t mean nothing by it. Just repeating things I heard around the fort. News travels.”

“Well, it ain’t true. Sheriff Rance was gunned down, shot in the back. No one saw who did it. I can guarantee you that much,” Parker said.

“That so?”

The two men were silent. Parker finished cutting and began shaving the man. Through the corner of

his mouth, the man asked, “How can you be so sure no one saw who done it?”

The straight edge scraped over the man’s Adam’s apple. “’Cause it happened on a Sunday morning, that’s how. The entire town was in church when we heard the shot. By the time we all came rushing out to see what happened, the killer was gone, and Sheriff Rance lay bleeding in the street. He died in the doc’s arms. Doc couldn’t get no words out of him before he… anyway, he’s in heaven now.”

Parker continued shaving. The man held up a hand to stop him for the moment. “You’re telling me this town ain’t yellow? You trying to tell me there are some real men in this town?” He laughed. “People say otherwise.”

Parker squeezed the razor’s handle. “Look here, stranger. I don’t give no hoot what other people are saying. I don’t like what you’re saying, not one bit, I don’t. I’m gonna finish shaving you. Then I’m going to tell you to walk out of here and leave town.”

“I’ll do as you say, friend,” the man said.

“I’m not your….” Parker stared at the man’s cleanshaven face. He glanced back at the wanted poster. “You’re—”

“Bobby Brackett?” the man said, rising from the chair. He pulled his gun. “This town might be yellow, but it got itself one smart barber.” Keeping his gun on Parker, the man looked at himself in the mirror. “Nice job, friend.”

“Get out!” Parker shouted.

“I’m going.” He backed up a step. “Oh, one other thing. I’ll be back. Tomorrow. First thing. A town with a bunch of cowards and no lawman is a town for me. I ain’t gonna tell you which place I’m gonna rob. Fact is, I haven’t made up my mind yet. Might be the bank or the saloon or the general store. I just don’t know yet. But you and everyone else in town will know tomorrow early.”

The man took off. Parker watched him ride away. It was already late. There wasn’t time to get a message to the sheriff in Bookerville. Parker closed his shop and ran to the church.

The man spent the night less than a mile from Stone Quake. Under a moonless sky, he made his way back. He carried a ladder he’d brought along,

climbed up, and went through one of the hotel’s back windows.

Sunrise. He stared out the window. Smiling, he scanned the street and storefronts. There were men everywhere. Armed men. Nasty looking men. Triggerhappy men. They stood sentry in front of every shop in Stone Quake. He didn’t realize the town had that many men. Impressive. It was time to make his move. He walked slowly down the stairs but noticed a group had also congregated in front of the hotel, guarding it. The man went back up the steps. He exited through the window and climbed down the ladder. He fired a shot into the air as he emerged onto the street.

“Hold off, everyone,” he shouted. He holstered the gun, reached into his shirt pocket, and pulled out a badge. “Name’s Peter Childs. I’m a U.S. Marshal. I’m the new law in Stone Quake.”

Despite the number of men, the street was silent. Henry Parker spoke. “What? You’re not Bobby Brackett?”

“No. Bobby Brackett doesn’t exist. I had those posters printed myself.”

“But, why?” Parker asked. “I don’t get it.”

“Truth is, I heard rumors about this town, that it was yellow. I had to find out for myself before accepting this job. Well, I accept. And I make a solemn promise to each and every one of you. I will track down Sheriff Rance’s killer and bring whoever done it to justice. God bless Stone Quake.”

BRUCE HARRIS writes mystery, crime, and western stories. His western short stories have appeared online at Frontier Tales, and anthologized in Grizzly Creek Runs Red, The Last Comanche, Bourbon & a Good Cigar, Time to Myself, Coyote Junction, Hangmen & Bullets, and The Shot Rang Out, among others. He lives in New Jersey, but that is only a temporary situation.

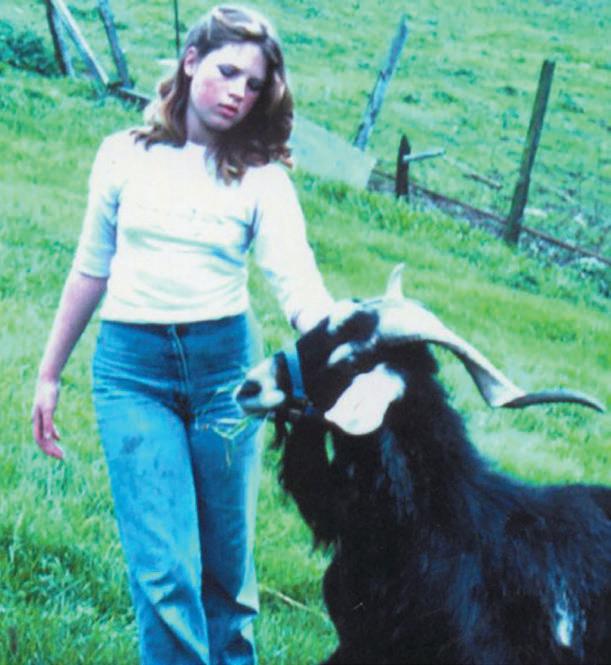

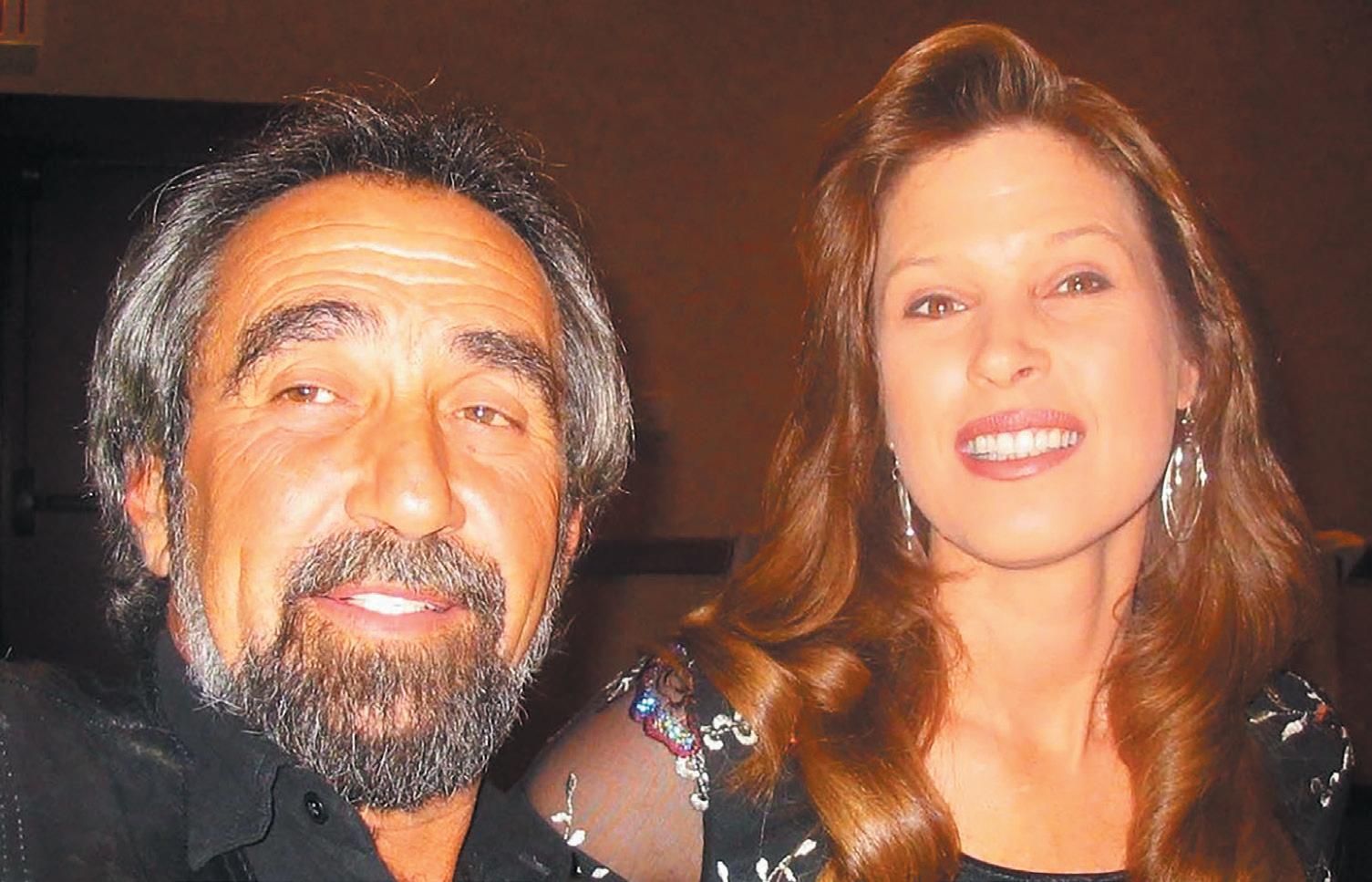

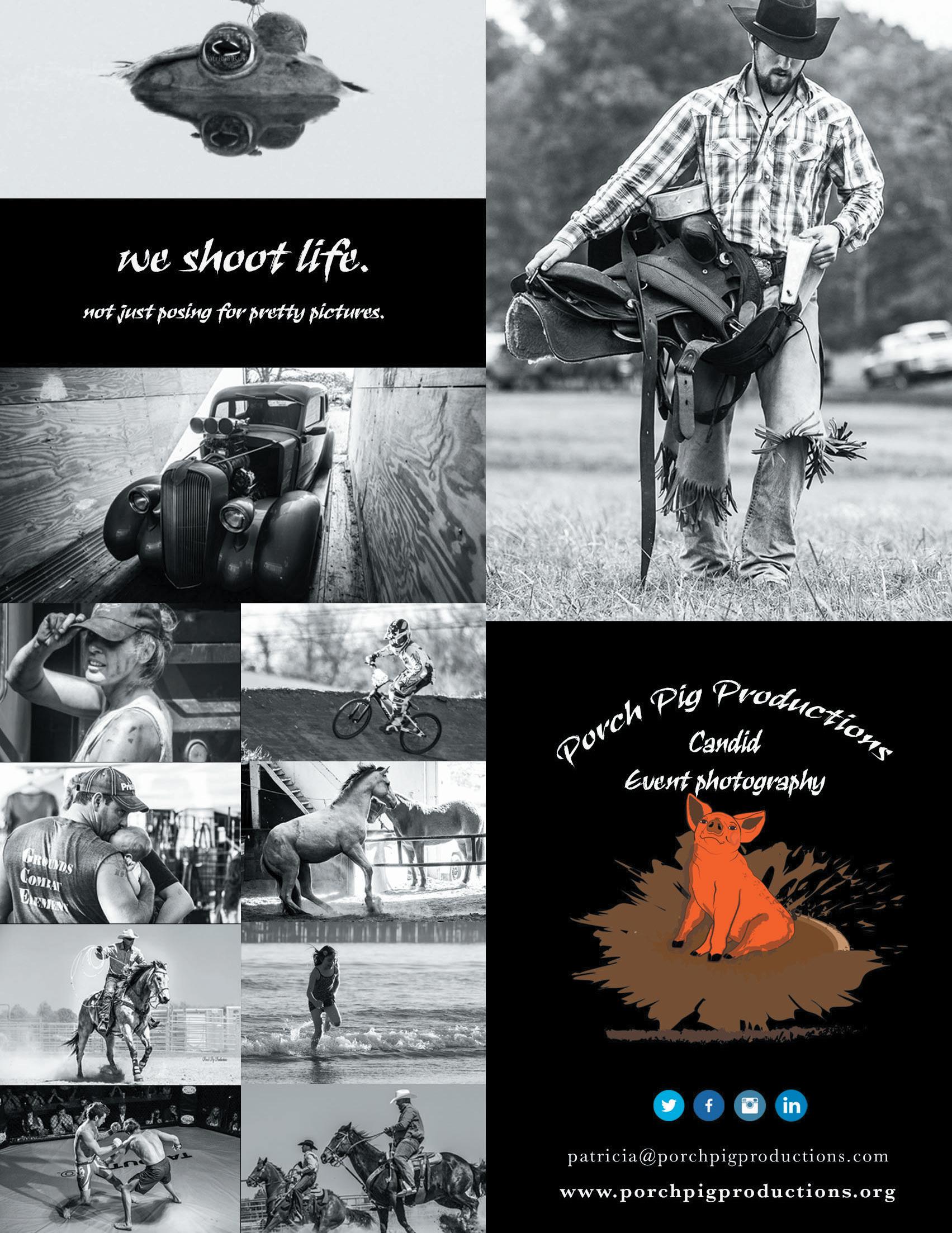

Truck Driver. Mother. Grandmother. Woman. Professional Equine Photographer Patricia Rustin Christen Wears All These Hats and Many More.

Photography Courtesy of Patricia Rustin Christen

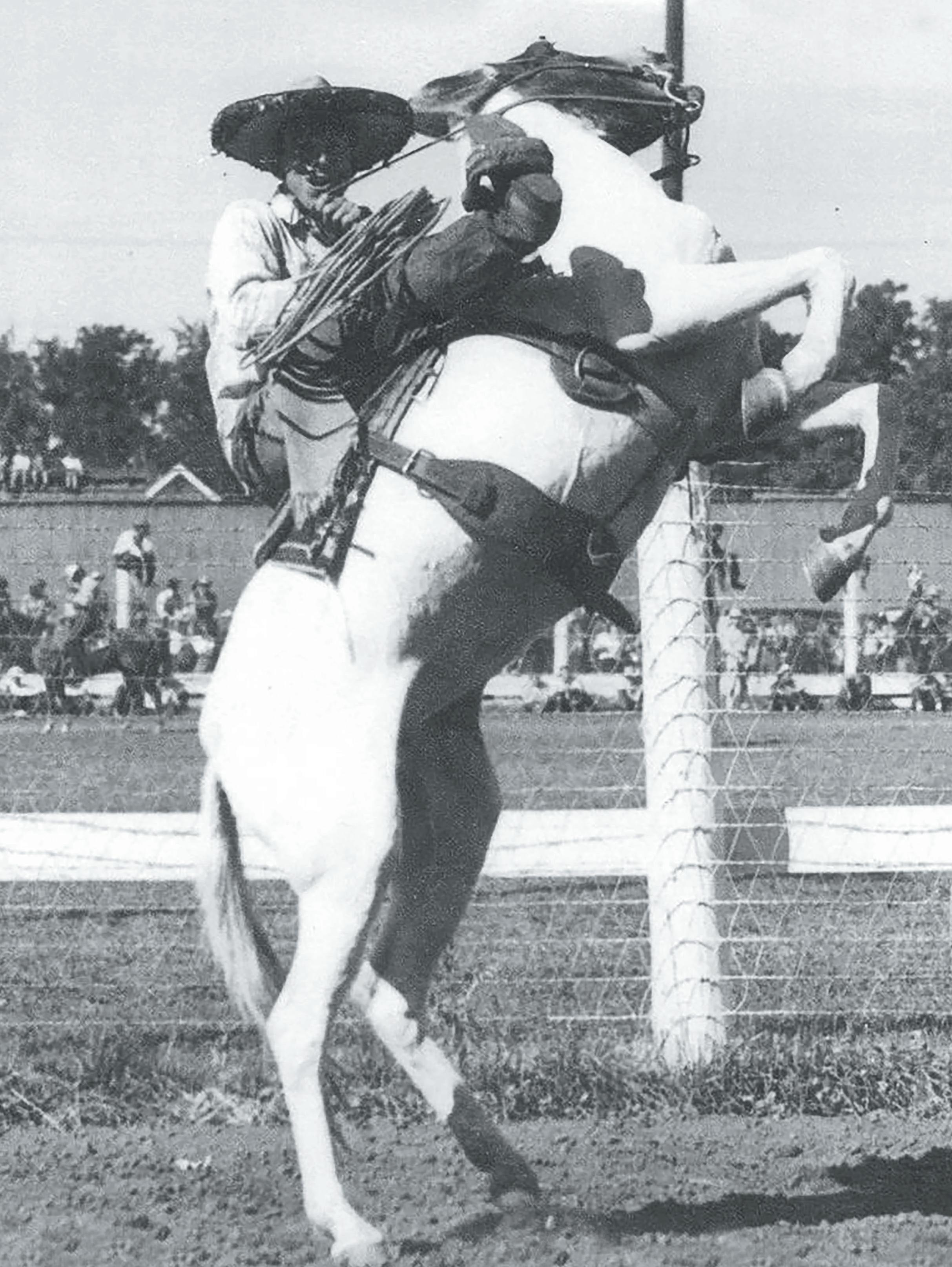

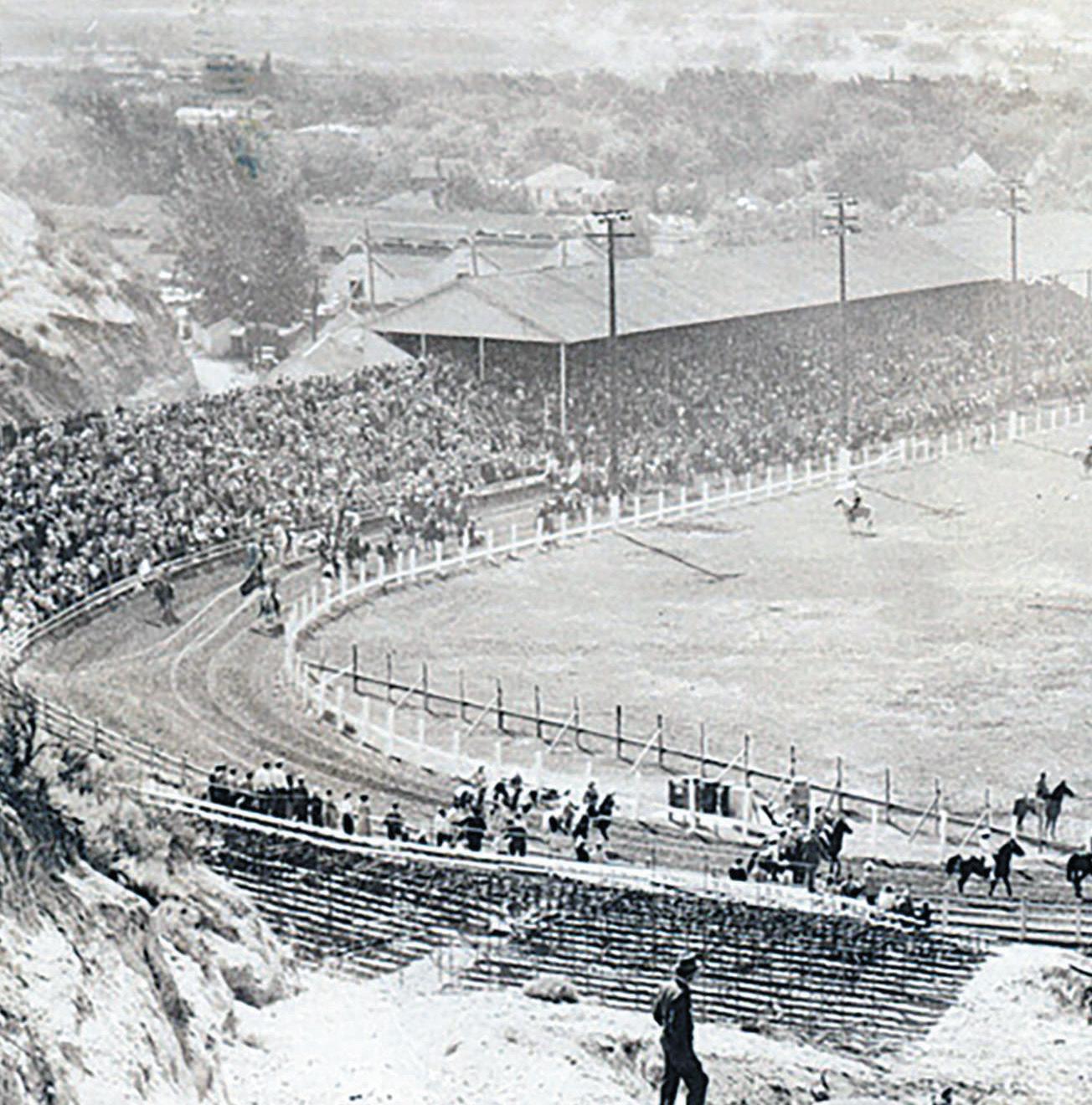

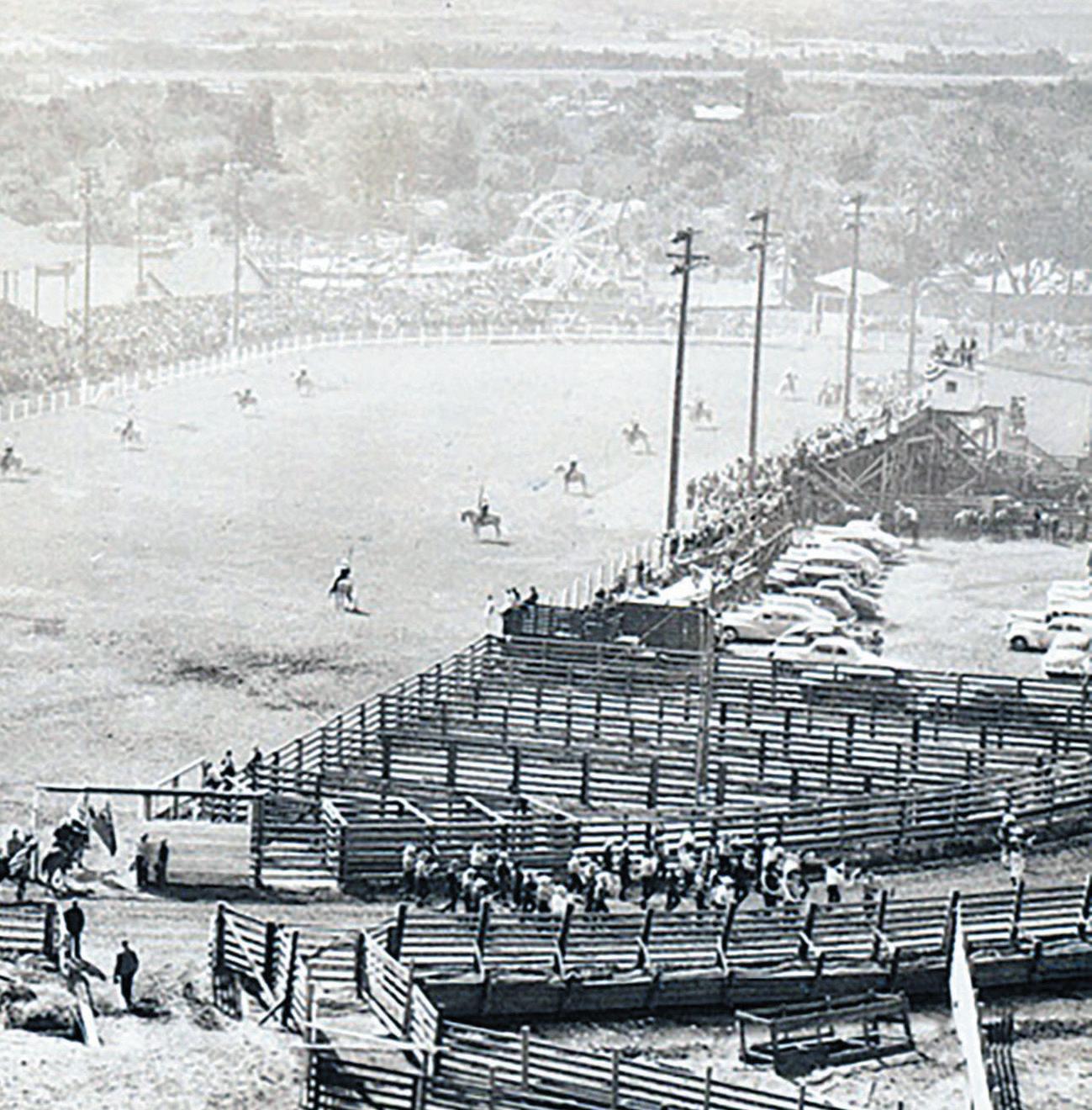

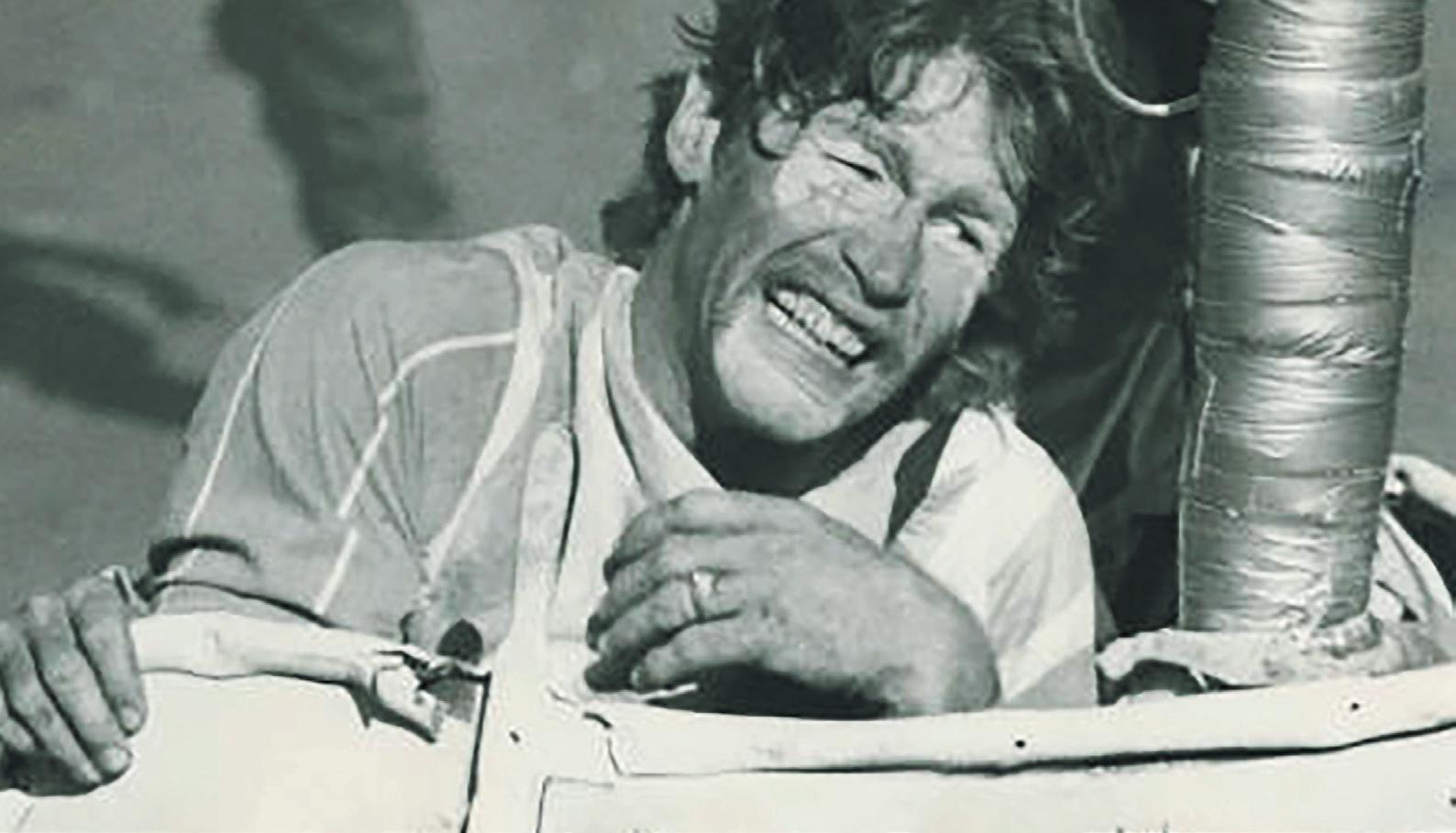

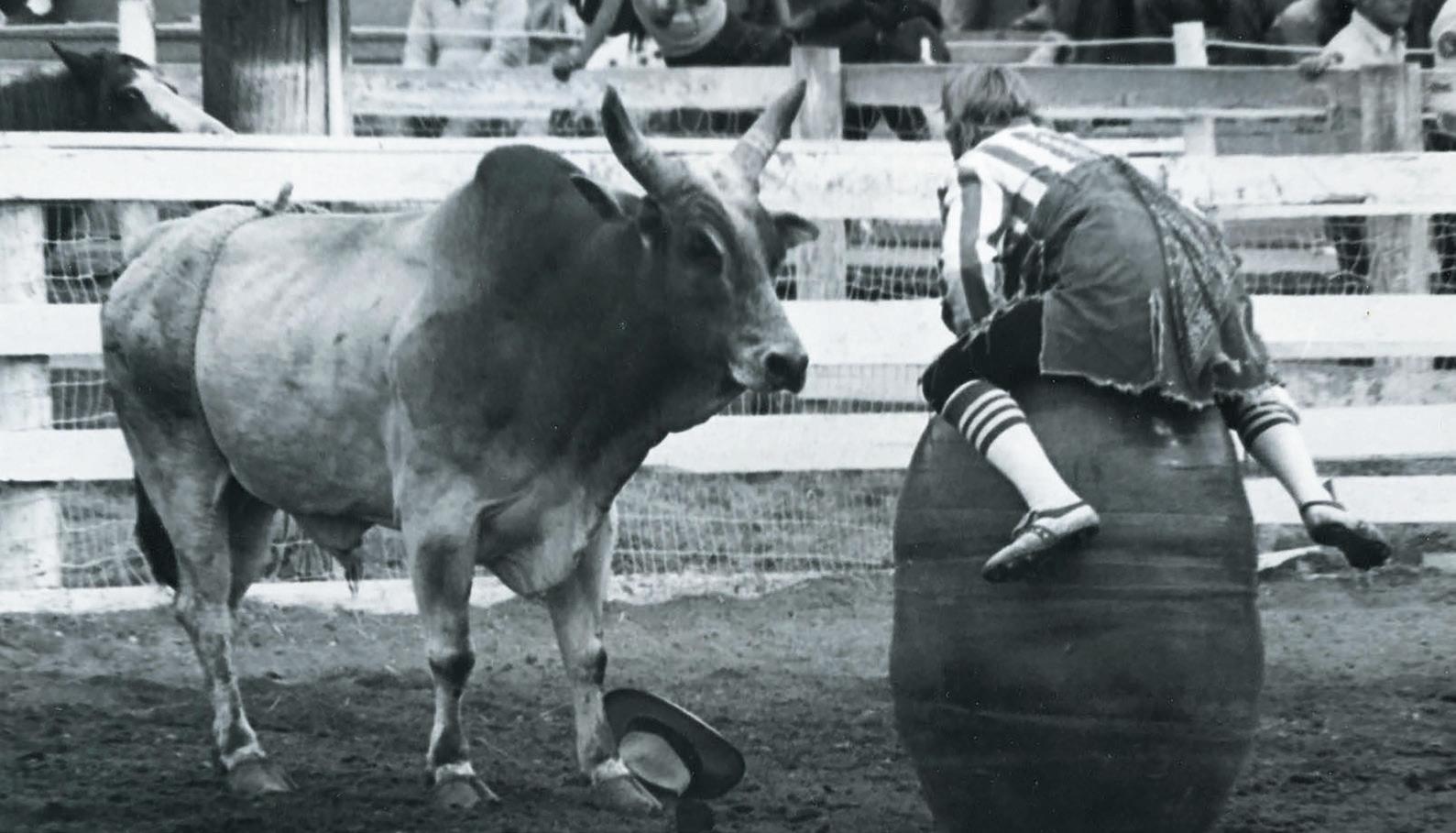

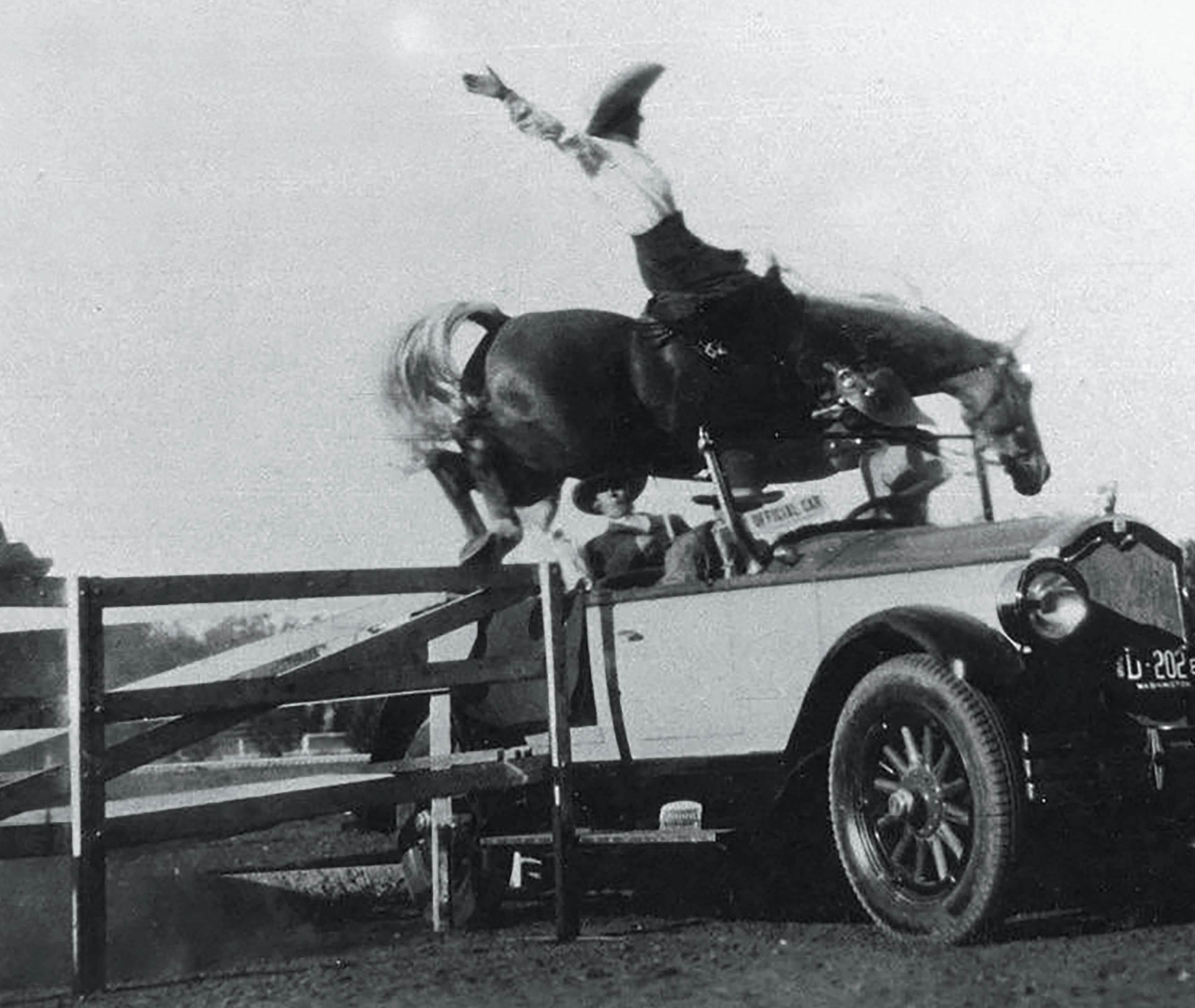

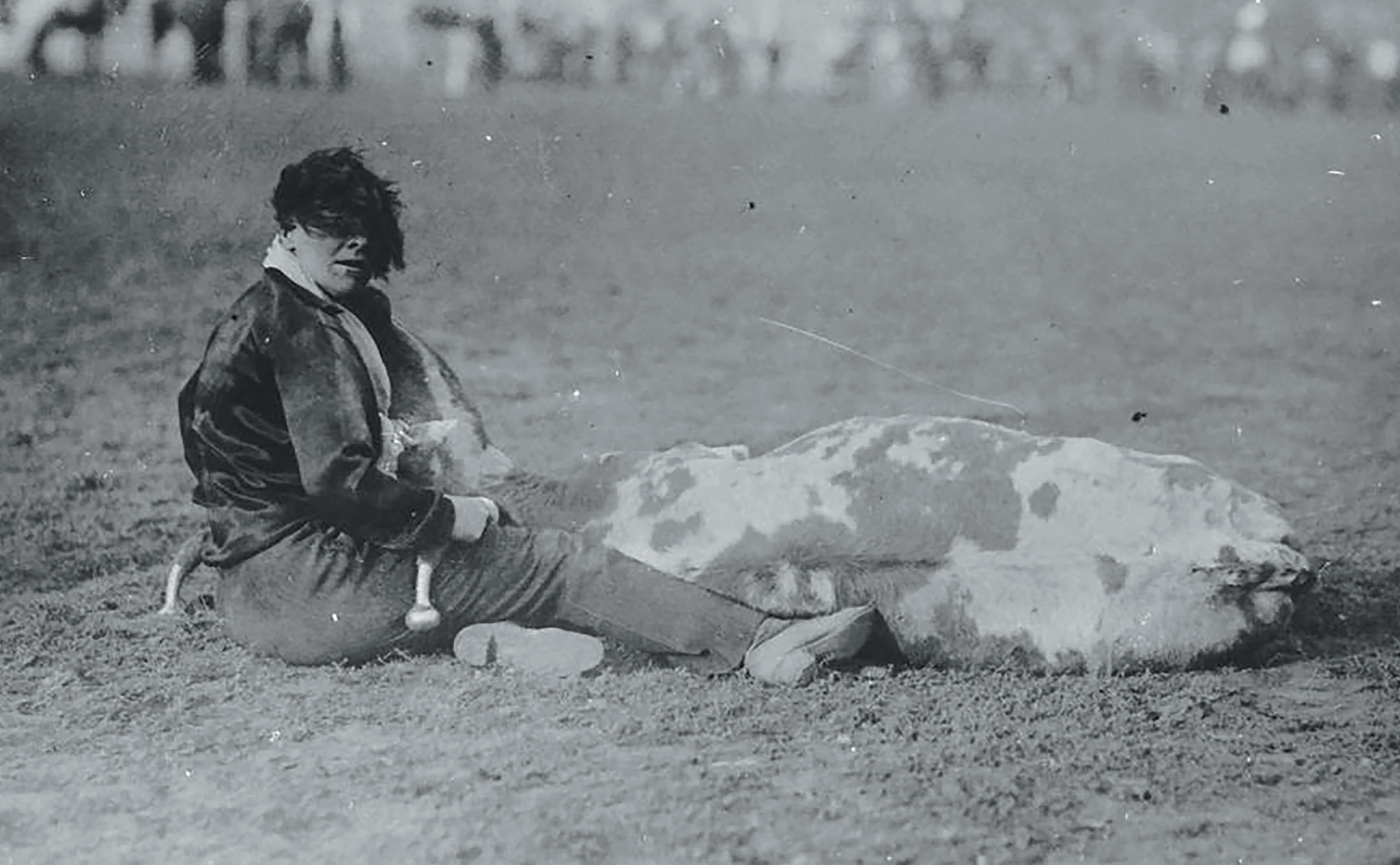

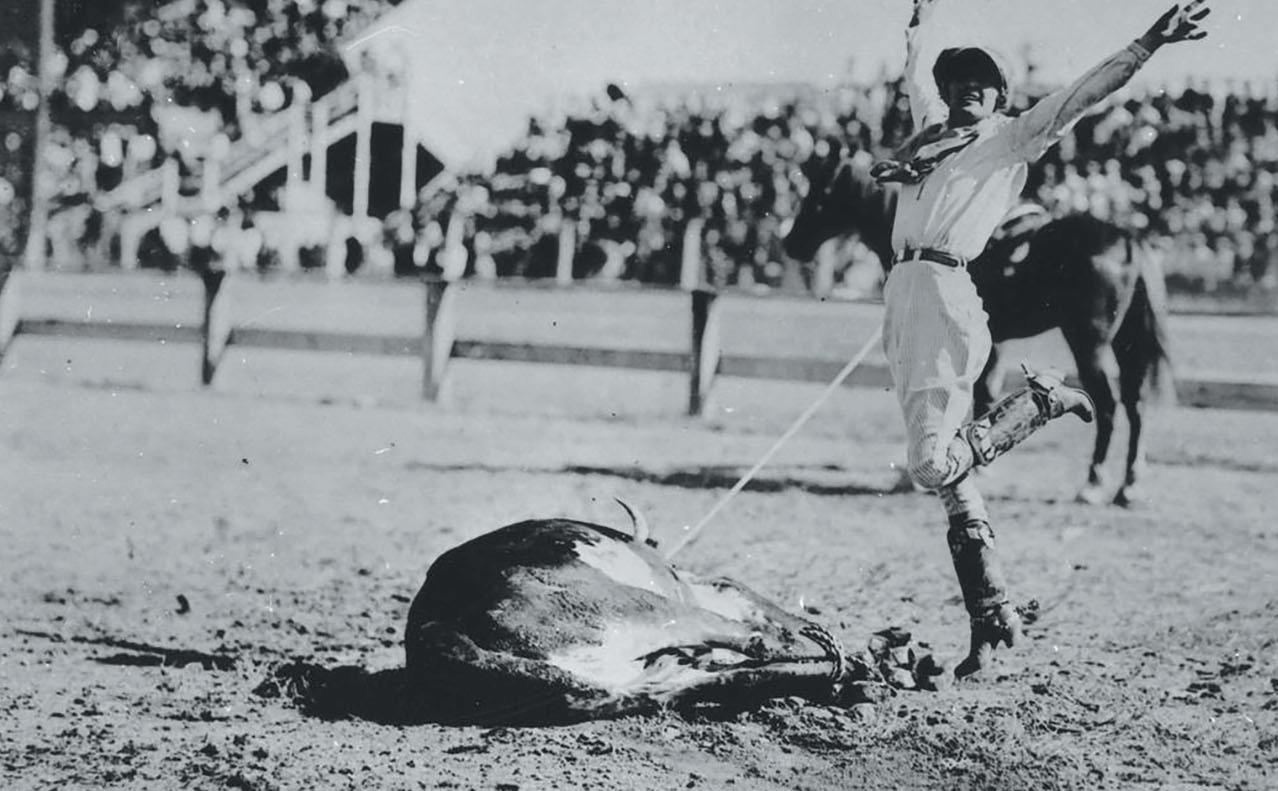

AT THE MIC, THE late Dusty Richards calls the race while crowds of people shout with expectation. And sprawled in the mud, camera lens focused between horse’s hooves and wagon wheels, a strikingly beautiful photographer searches for that perfect shot. The wild rivalry known as the chuckwagon races is held yearly in southern Arkansas. It’s only one example of where this brave photographer/truck driver, Patty Rustin Christen, can be found on any given day.

Patty and I ran across each other several times before we connected long enough to discuss her unusual and fascinating careers. Finally, I was fortunate to room with her at the Oghma Creative Media Summer Writing Retreat in Ponca, Arkansas last summer where she was busy focusing on business through the camera lens.

Having her company for a few nights gave me time to discover a complicated and courageous woman. She is driven not only by the demands of her talents

but by what the world has seen fit to deal her. And she is not afraid to face that tough life with her chin out. This long, lean, and graceful woman claims she was a homely child. Something it’s difficult to believe.

“When you don’t fit in anywhere, it’s like running from the devil,” she told me. “As a suicidal teen I drank a cup and a half of sheep dip. Something that should have killed me. I dealt with trouble in dangerous and harmful ways and almost died in the effort.

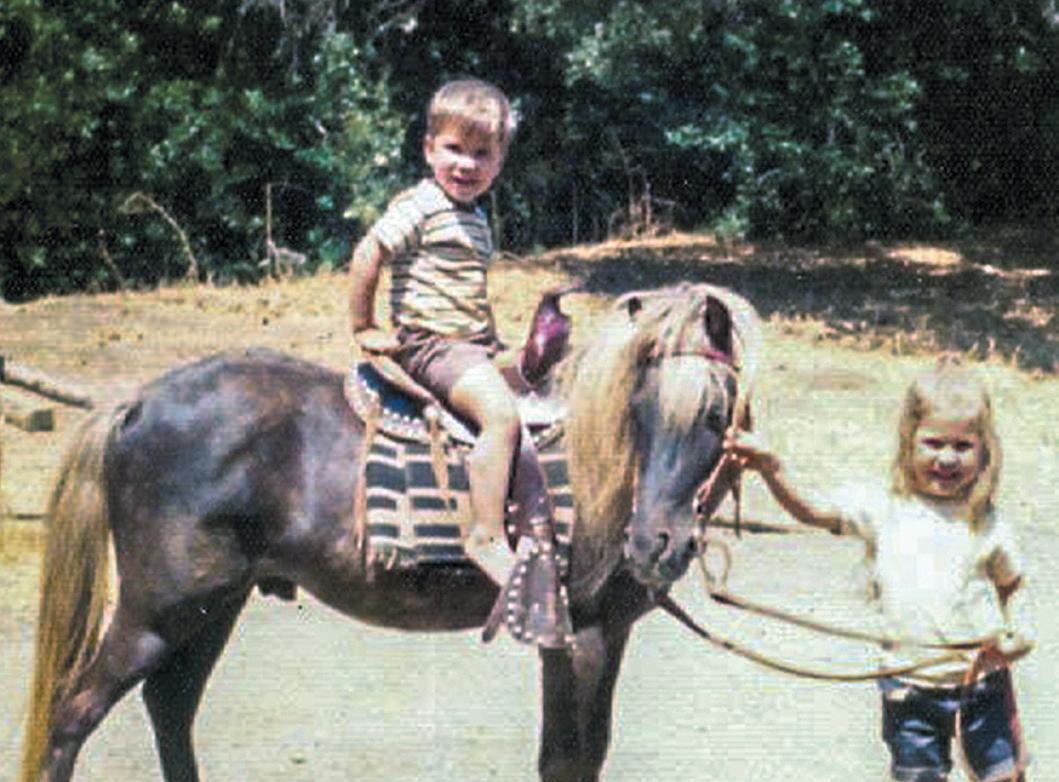

“The only time I ever felt free and special was on a horse and one steer I trained to ride until he ended up in the freezer. That was his intended purpose. I paid the kids down the street my Christmas money to rent their pony. I would climb a fence and jump on anything equine I could get to hold still. My first pony, Timmy, was gone after my mom and dad divorced when I was five.”

As the years passed, Patty tried numerous jobs from working at her Dad’s United Cigar store, waitressing, home health care, and a stint with a rare and

essential oil dealer where she learned about massage therapy. Yet, watching her go through her life now it’s difficult to imagine she once fought such problems. Today, nothing much slows her down.

There was that broken heart handed her by a Madison Square Garden champion a lifetime ago. “He told me he’d already seen everything, and I’d still not seen anything.” There’s the sound of a shrug in her soft voice, like she fought that disappointment off as well.

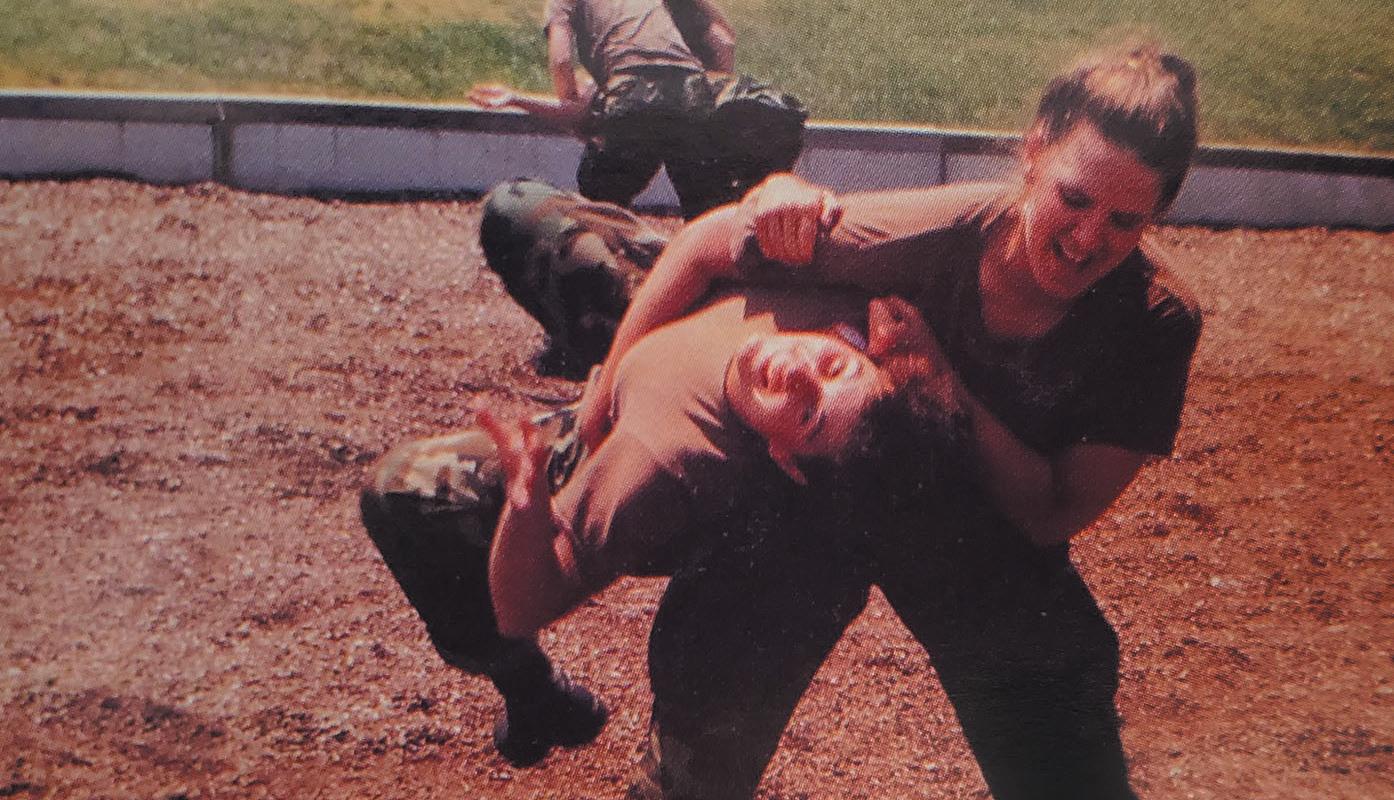

“With a broken heart, I joined the Army at twenty-two. I had hopes of using the promised tuition to attend the school of healing arts in Southern California when my tours ended.”

That dream was shot down when she was put to work repairing heavy equipment. A trouble shooter? Well, almost. She says, she was a glorified parts changer and

greaser. Not that she’s ashamed to get her hands and face black working on a job. It just wasn’t quite what she’d wanted or expected.

In the thick dark night, we’re both silent, and I wait for the rest of her story. I know it’s coming. Her voice catches, and she goes on, as if knowing I’m listening and not sleeping. She’s right.

“Driving trucks is where I met my second husband, Hawk, and it all came together. You see, Hawk didn’t want me to just learn how to haul freight. He wanted to teach me all he knew so I would have choices should anything ever happen to him. Over the past twenty-six years I have loaded and hauled cars on twelve-

car carriers and produce all over hell and a half acre, multi-million dollar show and racehorses....”

She takes a breath, and I do, too. This is super great information. Out of the darkness, her voice picks up where she left off. “...tankers full of oil, dump trucks full of aggregate or hot asphalt on road crews, frame-

less end dumps full of scrap metal, a little flat-bedding, and now I haul grain in bottom-dump trailers. Each aspect of trucking has taken me places and allowed me the opportunity to briefly experience the people behind the construction cones, in the factories, fields, and warehouses.” Her voice lowers, and I think she’s finished, but she’s not.

“Since Hawk was not afraid of anything breathing, he took me on tours to see architecture in the ghettos where most people don’t go. He would feed a homeless person and ask about their story. He was neither intimidated nor repulsed by the disenfranchised which

WHEN YOU DON’T FIT IN ANYWHERE, IT’S LIKE RUNNING FROM THE DEVIL.”

added to my wonder at hidden and forgotten treasures many never experience or don’t observe. He showed me a beauty of humanity in everyone. I learned it goes beyond a simple aesthetic. It may be a contrasted backdrop of the architecture in an individual’s life or current circumstances. Often fleeting, at times tragic, but it is there. It is not Vogue—it is life.

“It is a prostitute’s sequins back-lit by a streetlamp, a

tear on the face of a drunk telling you about a lost love, the graffiti under a corpse in winter being stripped of his clothes by the equally cold, desperate living.”

I hold my breath listening to her beautiful words that tell her story better than I ever could. One thing she soon learned. There was so much beauty in the world she yearned for a camera to capture it.

She continues to describe some of those sights burned into her memory. “A large black man named Dennis holding my three-year-old daughter on a dock where we picked up watermelons in Georgia. The contrast of her little pink hands sticky with the watermelon he’d cut for her against his beautiful blue-black cheeks, the Georgia sun shining hot on their faces trying to out-smile one another. Faded laundry that appears bright hanging on the lines as you drive past weather-beaten homes on some obscure two-lane road in Texas. The pride of the ladies wearing huge hats on a sweltering day lined up to go into a church. The fresh haircuts of new recruits and the sweat pouring down men standing on asphalt that can radiate a temperature of 120 degrees as they build our road.

“I have been blessed to witness all of this and more but did not have a camera for the first sixteen years, leaving many of these snapshots only in my memory. When I did get a camera, I was working on a now-closed ranch in Missouri. I would drive dump trucks in the morning and check cattle in the evenings. It was heaven. I knew three things. I loved horses, I hated having a camera pointed at me and told to smile, and that we are all winners, even if it’s just for a moment.

“Herb Reed introduced me to chuckwagon racing, and I was amazed! There they were, all of the people I have grown to admire over the years of driving,

I LOVED HORSES, I HATED HAVING A CAMERA POINTED AT ME AND TOLD TO SMILE, AND WE’RE ALLWINNERS, EVEN IF IT’S JUST FOR A MOMENT.”

from the characters to the politicians, the animals that saved my sanity and gave me a sense of beauty and freedom, and people competing in events that they may not win the ribbon in, but they were winning at life by trying.

“The people who attend these events are not all cowboys. They are a cross-section of my experiences. I soon made it a point to always try and catch them living, not posing. A candid snapshot of two old friends may not seem like much until one of them passes. Or a father dancing with his toddler daughter; a mother thanking her small son for opening her door; horses thundering down the track willingly giving their heart for their two-legged teammates and the finish line.

She continued to pursue that dream of driving a big truck. It’s hard to be exactly sure how or precisely when she made it because in the dark of the nights we were together came stories between us of how important time is to our lives. She’s a dreamer and a realist, a fact gatherer and a believer in the spiritual soul

and in the wonder of lives. In spending time with her, I found a human being driven by compassion.

Yet she finally satisfied her dream to own and drive a Peterbilt semi truck. It could have something to do with her second husband, Hawk, but in all the storytelling I’m not sure. I know he taught her how to win at life by trying and to never be afraid of anything and that he has taken a celestial departure. And that’s all. For then she speaks of the father she loves who is a commercial fisherman. He is important to a life that has been jumbled and filled with unhappiness.

She is the mother of a daughter and two grandchildren she adores. She drops by their place once in a while to visit. Imagine their excitement when she does. After all, not every child’s grandma drives a Peterbilt.

Nowadays, after driving a seventy-hour week, she often has a photography session to work. “And it is daunting,” she admits. But in her words, she cannot give up “laying in the mud, so I can get the best shot or bent over, my butt in the air, one leg stretched

“I CAN GO PLACES NO ONE ELSE CAN. I SEE HOW PEOPLE LIVE AND THE BEAUTY OF THOSE LIVES. ”

completely to the left, my right leg cocked at the knee ready to shoot me off the track and away from danger. I steady my breath, inhaling the event. The world goes quiet and click, I have stopped time, captured something that can never be repeated.”

But she admits, it’s not all joyous, this climbing in and out of one of those trucks. Once she fell from inside the cab during an ice storm— “cow shit on my boot from my last event”—knocking the back of her head on every step, then the concrete below. This injury haunts her to this day, causing physical reactions she has to fight. You’d never know it to be around her. All you see in this lovely woman is how she smiles in a particularly charming way or brushes back her long hair to get a better look at what she’s seeing through the camera lens. Or how she spends hours working on one photograph to please her subjects.

Today, Patty continues to drive that truck all over America, and she shares some of the sights she wishes we could all see through the lens of her camera. I ask her what it’s like to be a woman driving big rigs. “It’s pretty exciting, and men drivers are good to me.”

She grins into the joke, then turns serious. “I can go places no one else can. I see how people live and the beauty of those lives. They work in the fields and help feed all of us with what they do every day. They live in places other people should see but never get to. Their world is so beautiful, their lives so special.

Without them we would not eat like we do or have the kind of experiences we have.”

When she goes home, she sleeps in a camper because she’s rebuilding an old pole barn which will one day be her home. Around it stretches pastures, grazing acreage for her other love, her horses, which she misses riding today—but someday they will be a part of the time she can spend at home.

She sums up her life candidly. “Being an ugly duckling opened the eyes in my heart, trucking allowed me to use them, and by the grace of God, my stepdad’s generosity, my mother’s love of learning, and my father’s genetic predisposition of adventure, a camera has helped me find myself by finding the beauty in others by capturing their moments.

“I can’t afford to quit driving. The bills still need to be paid. Maybe someday I’ll be accomplished enough to take some time off to ride horses again. For now, they’re happy in the pasture. I’m getting ready to go on the road and looking forward to the next time I get to photograph one of your readers making memories. I am quite simply blessed.”

—VELDA BROTHERTON is an award-winning nonSaddle-

bag Dispatches Magazine. She lives on a mountainside in Winslow, Arkansas, where she writes every day and talks at length with her cat. Her next novel, Texas Lightning, penned with Dusty Richards, will be available in late 2022.

E AIN’T THE BEST lookin’ horse around,” Old Mike said. He gestured toward the sorrel gelding in the corral. “Hell, he ain’t even the second-best looking horse around. Tell you what, Jess, I’ll give you a deal. Thirty bucks and he’s yours. I’ll even throw in an old saddle I have, so you can ride out of here in style. If you can ride him. He’s got a fiery eye for a jughead, and he ain’t too shy to buck you from here to kingdom come. So, take it or leave it.”

It seemed like Old Mike was finished talking. He shifted a wad of tobacco in his cheek and peered at me out of the corner of his eye, then let loose with a stream of juice and cleared his throat.

I glanced over at the gelding.

Mike was right about the horse. His head was heavy and square, with no delicate features. Even his eyes looked windswept and tired. He had a drab sorrel coat, fringed by a mane that hung in wisps about his neck. A large white blaze began at his muzzle, then shot skyward like a lightning strike into his bony forehead. His tail was a beauty, though. It almost touched the ground and looked like flaxen swirls in the Sep-

tember breeze. The horse wore clods of dried dirt on his fetlocks and haunches. He hadn’t been curried in a long time. His hooves could use a good trim, too.

The sorrel’s back was straight, though, and there was a breadth to his chest that looked almost mighty, until he turned that massive head toward me and blew air through his nostrils. To say he was ugly would be a kindness.

“I’ll take him.” I heard myself say. Thirty dollars was a lot for a horse like this, but I figured he’d be a hard worker. If nothin’ else, he’d work out of gratitude, because I couldn’t imagine anybody else wanting him.

Mike nodded and ambled over to the barn. A few minutes later he came out with a saddle so worn I wondered if the cinch would last long enough for the ride home. I dug through my pocket and handed over thirty dollars, then took the saddle and set it over the fence railing. Hell, there wasn’t even a blanket to go under it. A frayed bridle draped over the horn. I picked it up and walked into the corral.

The gelding lowered his head and eyed me with suspicion. I couldn’t blame him. Here I was, just twen-

ty-two years old, trying to bust sod in the wilds of Nebraska. The horse probably figured I was not a man of substance, and he was right. Almost every penny I had went into buying a hundred acres in the middle of nowhere. It was my dream to work the land, live out here away from the cities where the air was clean, and eventually, attract a wife and start a family.

The horse stood patiently while I looped the bridle over his head. He took the bit without a head toss, his yellowed teeth fitting over the metal in a practiced manner.

I lifted the saddle over his back. Again, there was no roll of the eyes or swish of the tail. He allowed me to tighten the cinch and adjust the stirrups.

We walked out of the corral, and I tightened the cinch one more time. I put my foot in the stirrup, then swung my other leg over his back.

I barely hit the saddle, before I hit the ground. My leg bounced off a large rock and stung.

That old jughead bucked so hard the earth shook. Then he took off down the road like the Devil was after him, crow-hopping like a jubilant wind across the Nebraska plains.

Mike’s head worked its way around the barn door, then ducked back in. I swear I heard him chortle.

Afternoon was rolling in, and now, I had to spend the rest of the day searching for that damned horse. I started in the same direction Jughead flew a few minutes ago, my leg and my self-esteem bruised and angry.

I wasn’t too far down the road when I saw him grazing in an open meadow, tearing out sweet grass in energetic yanks and not paying attention to much else.

He was easy enough to capture. I was furious and walked right up to him in angry strides. I think somewhere in the back of his mind, he knew he’d gone too far. He turned his ponderous head toward me with disinterested eyes and let me grab the bridle under his jaw. I looped the reins over my arm, and we walked away. I wasn’t about to get back up on him yet. He was tricky, I figured, but once we got home and into my corral, I’d work with him and make it all right again. After that, he’d learn to pull the small plow I had in the barn. He might work best that way. Maybe someday I’d buy another horse for saddle ridin’, but for now he’d have to do.

It was a long walk home, and we wouldn’t get there until deep in darkness. The path across the plains was narrow. The breeze bent the prairie grass into undulating waves that danced in the mind’s eye.

Every once in a while, I stopped and let Jughead snatch at his dinner, his tail twitching in a rhythmic way as he ate. Tired, I longed to mount up and ride home, but I remembered how quickly he’d bucked me off and didn’t want to spend more time chasing him past the setting sun. There were about four hours of daylight left, and hopefully we’d make good time walking.

There was a movement out of the corner of my eye. I figured it was the wind again, but this seemed deeper, richer, as though it was an extra layer beneath the sky and horizon.

I stopped and peered out across the prairie to a solitary tree standing in a field in the distance. Then I saw movement again. This time, there was no mistaking it. Something was crawling through the grass, weaving in and out of the afternoon sunlight.

Squinting my eyes, I barely had enough time to figure out it was a person when three Indians popped up over a hill as though they had been hovering nearby like hummingbirds. There they were, bearing down at a fast pace.

I knew right away they were Lakota. There was nothing welcoming about them at all. They thundered toward us, raising their spears and whooping.

Jughead surveyed the scene with interest. He even raised his muzzle and nickered, as though he wanted to get acquainted.

There was no time to figure out what I needed to do. I just slapped myself in the saddle and drove my spurs deep into his sides. Jughead took off like a bat out of hell but straight toward the hostiles at a speed that belied the looks of him.

Then he came to a sliding halt as though he realized he’d made a mistake. He blew out heavy through his nostrils and heaved his chest, then pivoted so fast I almost lost my seat.

We took off in the opposite direction, but the Indians were closer now, shrieking like a coyote might when calling the moon in for the night. I hunched over Jughead’s neck, shoulders raised, bracing for an arrow

in my back. One flew by like an angry hornet, and Jughead put a bit more speed in his step. I hung on like a burr and prayed there were no prairie dog holes in the meadow because then there’d be no help for us at all.

Panicking, I felt for my old pistol digging into my belly, the holster rising with the bile in my throat as we galloped. I had some bullets but not enough to fend off the braves. They sensed victory, their cries more jubilant as they rode closer. Then, with the lackluster performance of a loser who gives up, Jughead slowed beneath me. I raked him again and again with my spurs, but he only snorted and shook his head, slowing to an easy lope.

We were headin’ straight toward a river. It looked like a thick brown snake cutting through the prairie, the steep bank a good twenty feet high. It might mean certain death to try to reach the river, but why not take a chance tumbling down the cliff instead of being scalped. Maybe we could make it, but it was doubtful. I tapped my spurs and leaned back to take my weight off his shoulders.

Jughead gathered his powerful haunches, but instead of scrambling down the bank, he simply decided to fly. For a second, it was like nothing I had ever felt before. Man and horse, poised in the air like some sort of god who came down from the stars, just to dance around a little with gravity.

Then we hit the water so hard my head snapped back, and I bit through my tongue. I kept my seat, even though the river covered all but Jughead’s neck, and polished the saddle until it was like riding a slick fish. Frantic, I grabbed the horn as the swirling eddies washed us downstream. Old Jughead tried to swim, his hooves touching a wayward boulder from time to time, then veering off and going back into the frothing current.

I dared to look behind. The Indians were picking their way down the steep incline, and I smirked. At least we hadn’t been as dainty as they were. Their ponies snorted and stumbled. A small avalanche of rocks and dirt tumbled into the water. The Lakota turned and rode back up to solid ground.

I breathed a sigh of relief. They gave up. I even let out a little war whoop myself. Only, at second glance, I saw they weren’t quitting yet. They raced along the

top of the cliff and loosed a hail of arrows at us like we were ducks in a pond. Jughead veered sideways and snorted. An arrow lodged itself in his side. Blood poured out in a thick stream. He tossed his head and swallowed some of the river.

Just then, the cinch broke. It slapped upwards and hit me in the cheek. The saddle slowly turned sideways, driving me halfway into the water. I had enough wits about me to free my feet from the stirrups just as it floated right out from under me and into our wake.

I slid off right behind it. The water was so cold I thought it might stop my heart. Grasping, I caught the end of Jughead’s tail and hung on for dear life. Now, arrows were flying all around us.

Jughead turned toward the opposite shore and swam out of the current. His mighty chest bellowed, and his legs pumped like pistons on an engine. His hooves touched the sandy bottom below, and he shot straight out of the water, dragging me like a bag of flour. Then he shook me off, climbed the bank and ran away, leaving me alone among the rocks and logs that littered the wet ground.

I hauled myself up the cliff, grasping at roots and shrubs, using my last bit of strength to scale the muddy bank and onto a ledge of grass. I crouched behind a bush and looked across the water.

The Indians stopped on the other side of the river, talking with each other. Then they nudged their ponies down the bank and plunged into the water.

Their horses had other ideas. Shocked by the coldness and the swirling eddies, they lost their footing and bobbed in the rushing current in no direction. But, just like Jughead, they found footing on a shallow bar, and turned toward me.

I had to run. My sodden boots were heavy as anvils. The wind blew through my soaked clothes, lifting my tattered shirt as though it wanted to fly. It wouldn’t be long before they’d catch up to me. I figured all I could do was try to find a little shelter and stand my ground.

Reaching down, my hand slid along an empty holster. The pistol had fallen out into the river. All I had now was a knife strapped around my thigh in a leather pouch. I knew if the Indians got close enough

for that type of combat, I’d lose my life in the space between ragged breaths.

Just then, old Jughead came galloping back, his square head bobbing up and down with each thundering hoof beat. His massive chest expanded as he let out a boisterous whinny–as though he wanted to make sure the Lakota knew exactly where we were.

Jughead halted in a cloud of dust and turned sideways between the Indians and me, heaving. The arrow was still poking out of his side. Blood dripped and pooled onto the ground.

He took another arrow, then another, into his hide, flinching and snorting as he stood there.

Gasping, I used the last of my energy to pull myself up on to his bare back. He took off like a shot. Jughead galloped low to the ground, his head level with his shoulders. There was little to hold on to but his mane, and I dug into his neck like a tick.

An arrow struck my rib. I have to tell you, I didn’t even feel the pain, I was so filled with fear.

Then, like a waking nightmare, Jughead pivoted and ran straight toward them again. We got close enough to see the paint on their faces, then he turned so fast I barely held on and ran parallel to the river.

I didn’t have time to say a prayer when he flew off the cliff and back into the water. This time when we landed, he let out a huff, then started swimming like demons were after him, and they were. We reached the opposite shore and Jughead lurched back up the bank. His labored breathing echoed in the wind like a prairie storm cutting across the fields.

The Indians shook their spears at us but didn’t bother to cross again.

I couldn’t breathe. There was no relief, I feared. We might run right into another pack of those Lakota, and then all this effort would be for nothing.

After a mile or two, Jughead found the trail, and we trotted down the path as slow as going to church. I looked over my shoulder, and there was nothing behind us but the wind.

He hung his massive head and breathed in great gulps. I peered around, then slid off. Three arrows pierced his hide. The one in his side was deeply embedded. It had likely stabbed his guts. I didn’t want to hurt him further, trying to dig it out. I plucked the

other two out of Jughead, then tried to reach the one in my rib. After a painful pull, it came out in my hand, and I tossed it on the ground. A moment later, I was bent over with searing pain as blood ran down my side and into my pants.

Jughead seemed to sense we were out of danger. He lowered his muzzle to my neck, and the warmth of his breath was oddly comforting.

Night fell, and still we plodded through the prairie, wondering if those damned Lakota were hiding behind each tree or knoll. But the only sounds I heard were a few coyotes on a plateau, calling for their mates. Stars lit the sky so bright I could see Jughead’s face clear as day.

Trembling, I reached out and rubbed his neck. The horse saved my life. Here I was, a young man who came out west from Ohio to carve out a life. So far, Nebraska hadn’t treated me the way I’d hoped. Guess I never figured the land might try to shake me off it. I missed my family back home. I missed the warmth

of friendship and the delicate touch of a woman. Out here on the prairie, a person could go mad listening to the sound of their own silence and the rustling in the grass. Sometimes the sky overhead looked so vast and the prairie so wide, I wondered if I might get swallowed up into the hungry ground itself and never be heard from again.

Ahead in the darkness was a deeper shadow. I knew it was a cottonwood tree on my property, steadfast in the night, to welcome us home from certain death.

Jughead faltered and snorted next to me. He turned his great, square face into mine, and I swear he looked right into my soul as he went down like thunder. Blood trickled out of his nose. He lay on his side, ribs heaving in pain, and let out a sigh.

I didn’t have my pistol. There were no bullets to put him out of his misery. Crying, I sat down in the middle of the dirt and put his heavy head on my lap and stroked his poor neck.

I would not, could not, leave him behind. I’d stay

here in the darkness and see him through. I guess the part of me that was still young and hopeful thought maybe he’d feel better, and we’d walk the rest of the way home at dawn.

Somehow, I fell asleep. I woke with my hands gripping his mane. The sun was cracking over the horizon, drifting across the fields, lighting up the plains, and peering through the leaves in a stand of trees.

I turned to Jughead.

He was gone.

Sitting in the dust with his body, still warm, I felt about as lonely as a man could feel.

There was nothing I could do but straighten up and leave him. The walk over the hill and down to my old sod shack didn’t take long.

Each step took me away from my dreams. I was grateful the Lakota didn’t get me that day. I owed it all to Jughead.

I rested up for a day or two, then packed my things and headed back down the path toward town. There was just enough money left to buy a train ticket home. Turning back, I saw that the harsh Nebraska wind had already nudged the door open to my hut, dust and prairie grass crossing the threshold like squatters.

I passed Jughead’s body. Two vultures circled the sky above him. That horse sacrificed everything for me. Now, he’d feed the birds and the coyotes, his parting gift on his way to eternity.

His wispy mane rustled in the breeze, like a living thing that hadn’t yet figured out it had died. I bent down and tugged the arrow out of his side, so he could enter heaven, or wherever horses go, in dignity, then broke it in two with my bare hands.

Taking out my knife, I cut a handful of hair from his tail, tucked it in my pocket, set my sights toward town, and started walking.

SHARON FRAME GAY lives in Washington State with her little dog, Henry Goodheart. She grew up a child of the highway, playing by the side of the road, and spent a lot of those years in Montana, Arizona, Nevada, North Dakota, and Oregon. Interested in everything Western, and in horses in particular, she bought her first horse when she was twelve.

Although she is a multi-genre author, she has a special fondness for writing Westerns. Her Westerns can be found on Fiction On The Web, Rope And Wire, Frontier Tales, Typehouse Magazine, and will soon be appearing with Five Star Publishing in an upcoming Western anthology. She is also published in many anthologies and literary magazines, including Chicken Soup For The Soul, Crannog Magazine, Lowestoft Chronicle, Thrice Fiction, Literally Stories, Literary Orphans, Adelaide, Scarlet Leaf Review, Indiana Voice Journal, and others. She has won awards at The Writing District, Owl Hollow Press, Women on Writing, and has been nominated twice for the Pushcart Prize.

aYou can find more of her work on Amazon, or as "Sharon Frame Gay-Writer" on Facebook, and Twitter @sharonframegay.

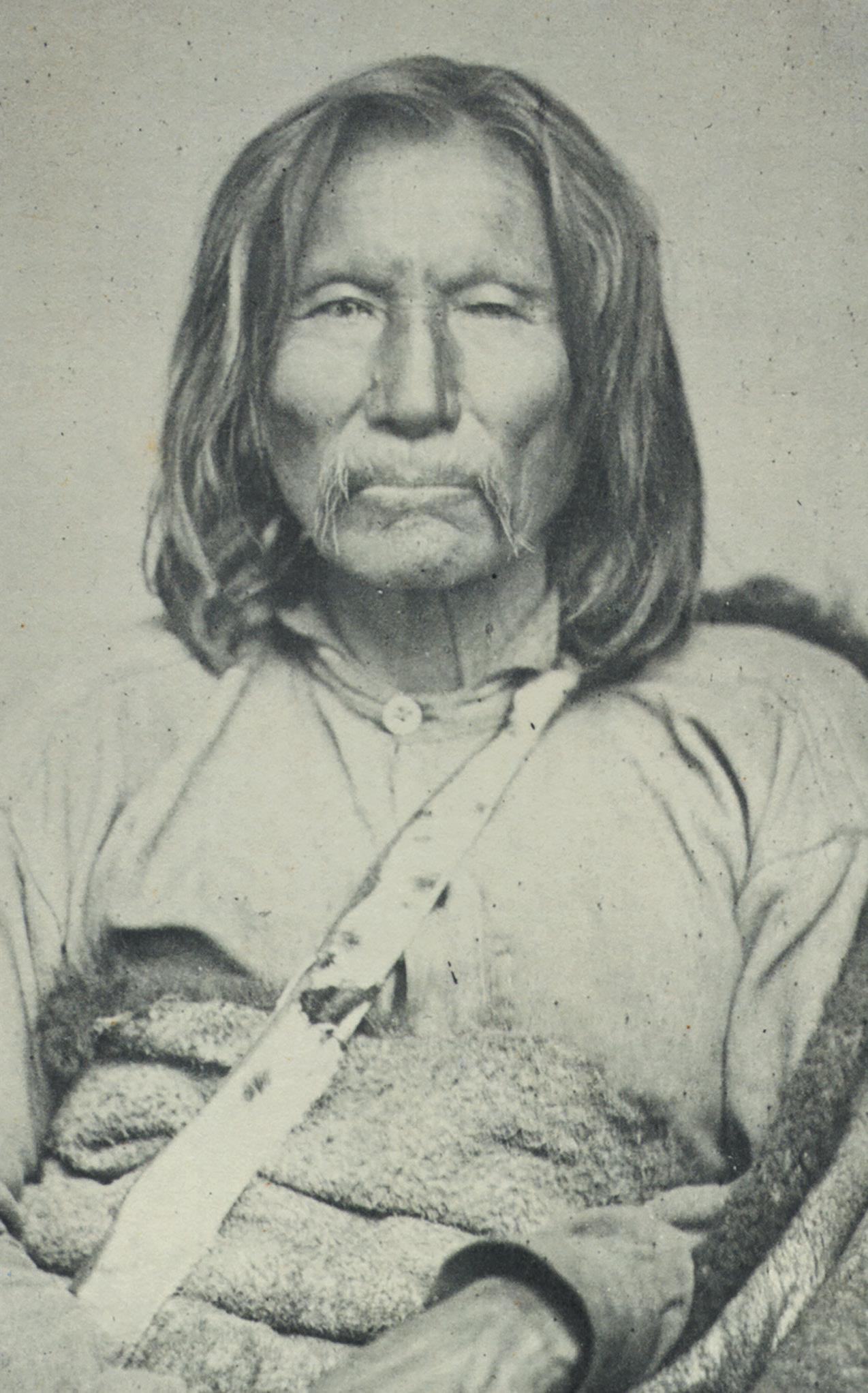

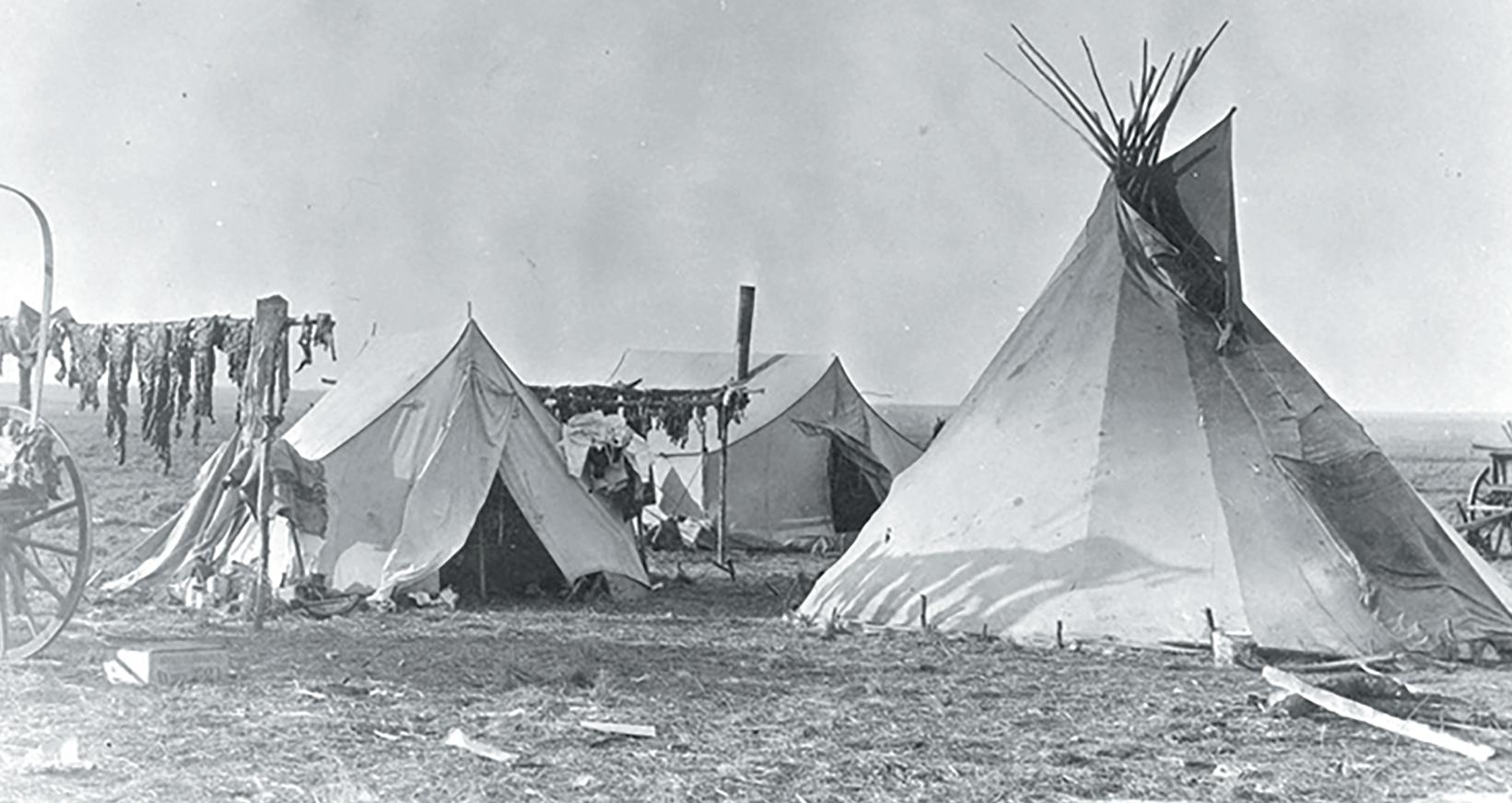

ONE EVENING IN THE Season of Large Leaves (July), I sat with my father, Geronimo, at the edge of his house’s breezeway in his village on the Fort Sill prisoner of war reservation. I worked on a piece of beadwork as we watched the sun disappear in a golden glow behind the gentle swings and sways of the prairie’s horizon. Father, a diyen (shaman) of great supernatural power, was quiet and still, studying everything from the mountains on the horizon to the horses and mules nipping at each other in the corral. We were content listening to the calls of the googés (whippoorwills) and the insects and peepers in the brush by Cache Creek. As I strung and sewed the beads in place, I thought about how and when I should tell Father that Fred Godeley had asked me to marry him and that I wanted this fine man. I knew Father would surely approve.

Boards creaked in the breezeway behind us. I looked over my shoulder and smiled to see Ramona, my uncle Daklugie’s wife, in the setting sun’s glow. More than an aunt, Ramona was my best friend and advisor.

My father said, “Ho, Ramona. I see you. Come sit with us and enjoy listening to the night.”

“Ho, Grandfather. I can’t stay long. Daklugie wants to sleep, and the children still play around the house. I have good news for you.”

“Hi yi! I always like good news. Tell me!”

“During your last trip, Eva’s womanhood came. Now, we must do her womanhood ceremony, and I’ve heard you say that you planned to have a big feast with much singing and dancing to celebrate it. Have my ears heard you correctly?”

He turned and looked at me as I sat watching the falling darkness unable to repress a hint of a smile. I saw the flicker of a frown cross his face before he laughed and said, “Yes, Ramona, you have good ears, and, Daughter, I’m very glad for you. At long last, you’re a woman. We’ll have a great feast with all our friends to dance and sing with us. Ramona, since her mother has left us for the Happy Land, will you serve as Eva’s attendant? How long before we can hold the womanhood ceremony? What do you need me to do? It must be one the People remember.”

Ramona laughed and held up her hands to stop his questions. “Yes, Grandfather, my sister Emily and I will be her attendants and guides. We’ve already talk-

ed about when we should hold the ceremony. Eva’s mother had started working on her ceremony gown before she left us, and we worked more on it while you were away at Great Father Roosevelt’s parade and the 101 Ranch. There’s much to prepare. I think, if you approve, the ceremony and festivities could begin on the second full moon from now.”

Father looked at me and smiled. I remembered our days at Mount Vernon in Alabama and how he used to pull me bouncing and giggling around the camp in a little red express wagon and let me buy anything I wanted in the trader’s store filled with delicious smells of cured meat, cheese, fresh bread, sweet candy canes and chocolates, red and black blankets, and tools of all kinds. No one could have been a better father. He blessed me often now for all the hard work I had done helping my mother, Zi-yeh, before she had ridden the ghost pony, and he told me every day what a help I was to him.

Father said, “We’ll have the best of socials and dances to celebrate this great time.” He spread his arms wide. “Invite all the Apache. We have much work to do. Buy what you need, and I’ll pay.”

Smiling, I said, “Thank you, Father. You make me happy that I’m your daughter.”

Ramona said, “Enjuh! (Good!) This ceremony, feast, and social dancing will make a good time for all, Grandfather.”

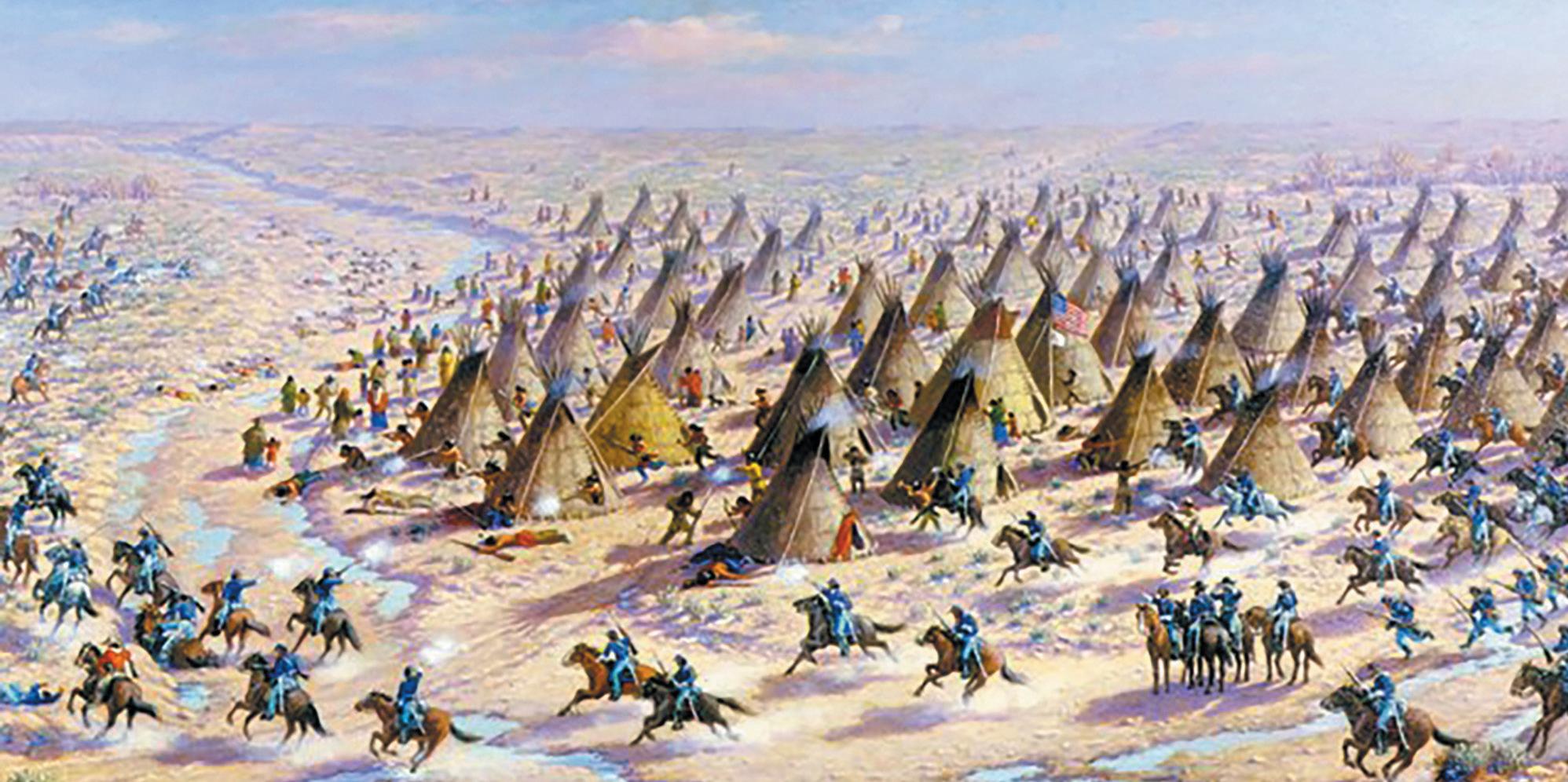

THE NEXT DAY, FATHER spoke with Naiche, long time chief of the Chokonen Chiricahua, about the festivities. Near Naiche’s village, they picked out a level place on the south side of Medicine Bluff Creek where the grass could be cut close in a big circle. Naiche agreed to lead the singing. Father would lead the dancing with the di-yens who conducted the ceremony.

Planning and organizing picked up speed like a runaway wagon. Father told the other eleven village chiefs to tell their People they were invited. Soon, anticipation and excitement for the four days of ceremony, feasting, and dancing hummed through the village. Women from every Apache village planned to help with cooking for the feasts. The ceremony

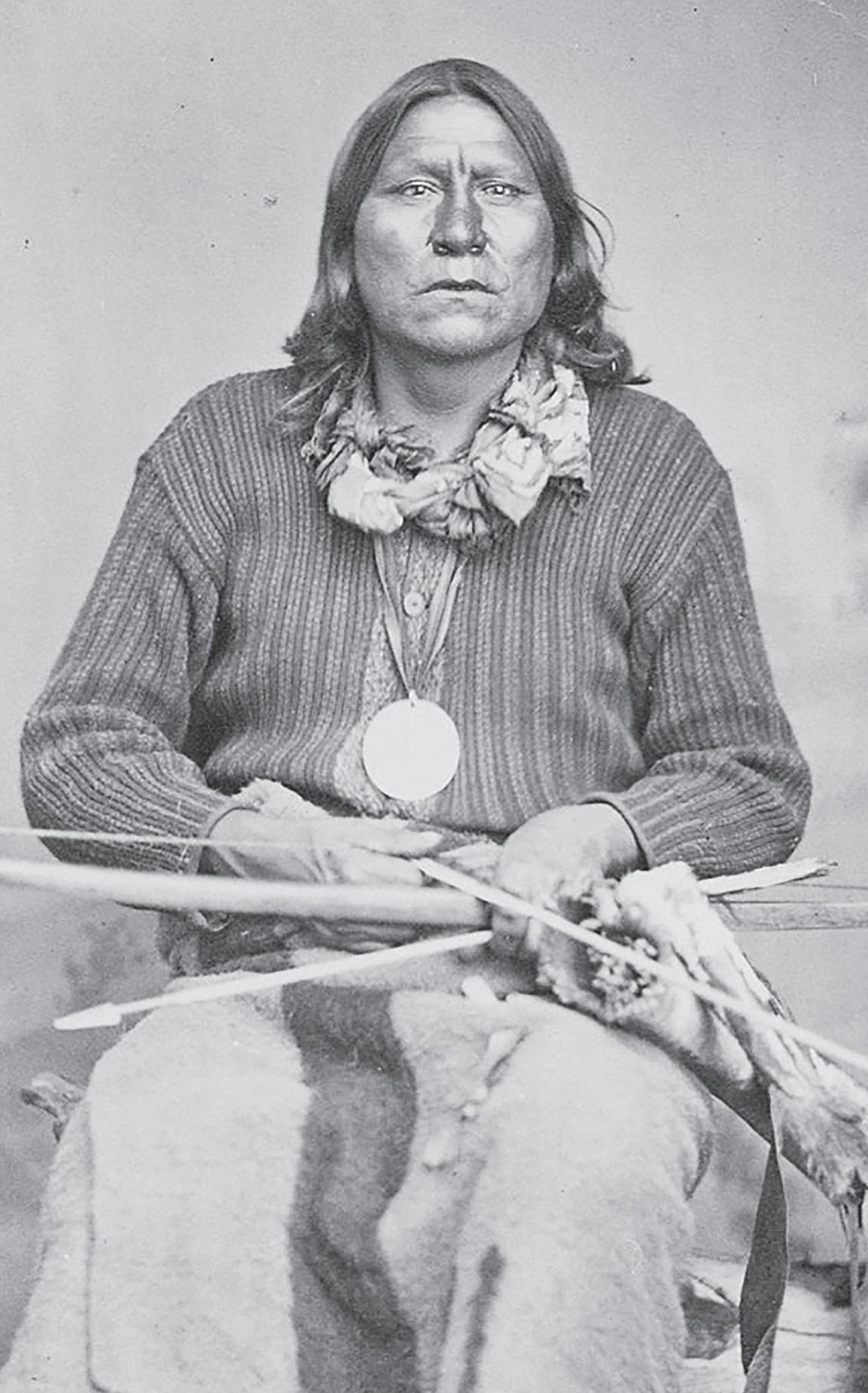

would begin the night of the first full moon in the time the White Eyes called 13 September 1905. Father also invited his good friend, the great Comanche chief, Quanah Parker, and all our other Comanche and Kiowa friends. He even asked the White Eye, Barrett, who later that fall would write Father’s life story as he told it and my uncle Daklugie interpreted it in the White Eye tongue.

Ramona’s sister, Emily, was near my age and had married a few months before we began planning my social. Father decided to have family photographs made before the ceremony so we could all remember when his youngest daughter became a woman. George Wratten, our official interpreter, who ran the supply store for the Chiricahua, arranged for a photographer in Oklahoma City to come to Fort Sill. I was very happy with the thought that one day I could show my children a picture of their grandfather and me, taken before I’d married. The photograph Father wanted with Ramona, Emily, and me was not made because Ramona had a sick child and could not leave her. Father had the picture made as he sat in a chair with Emily and me standing beside him. We looked and felt like princesses standing beside a king on his throne.

I had a fine womanhood ceremony with Ramona and Emily guiding me in what I should do and how I should act during the celebration. Great signs of Power from Ussen, our Apache creator god, passed from me to the People. For four nights, the four masked Crown Dancers painted in green and yellow and two clowns in white paint danced in the blazing yellow and orange firelight before the People danced and had a fine feast. I was very happy.

On the fourth night, after the ceremony finished, I was considered a marriageable woman. As the moon rose, we all joined hands around a big fire in the center of the field and danced in a circle with the four masked dancers circling the fire. Then there were dances of a circle within a circle, and as the fire died down, the men made their circle into wheel spokes that ran out from the fire to the outer circle of women. Sometimes the spokes moved with the circle, sometimes against it, sometimes the same speed, sometimes slower, depending on the songs that were sung.

As the moon reached the top of its arc and began

falling in the southwest, baskets of food were laid in a line out from the ceremonial place, and we all ate while the masked dancers completed their dances. When the dance began again, the old ones left the dance to the young people to begin the lovers’ dance. The drums stopped, and what the White Eyes called the music started. Apaches use no such word as It’s just a flute the young men learn to play to court their women. It has many voices and can be made to sound soft and slow or played very hard and fast. This night several were played together in good harmony, and there were also two Apache fiddles to add their voices. Our fiddle is made from a piece of dry yucca stalk. A string of horsetail hair is stretched over it and passed across a specially shaped sound hole. The instrument is played with a horsetail hair bow. As the fiddles and flutes played, they made a dreamy sound that caressed the hearts of us all as the young men made a circle around the fire and the girls made an outer circle. One after another, the girls danced to the inner circle and picked a young man to dance with as they formed the spokes of a wheel, doing two steps forward and one back while the couples held hands and looked at each other.

Since the dance was in honor of my new womanhood, I was the first to dance to the circle of young men waiting in the flickering orange and yellow light. With my heart pounding, I danced around their circle four times, as custom required, and then stopped at Fred and tapped him on his shoulder. When he turned to me, his smile was brighter than the morning sun on the high mountains. He was taller than most young men his age, and he had big hands and a strong face with high cheek bones. We had known each other since we were children, and as I watched him grow to manhood, so did my desire to be his woman. One day, we “happened” to be walking together to the mission school when he blurted out that he had often wanted to ride past our house in hopes of seeing me. He said he didn’t ride by my house because his family was poor and could not afford a good bride gift for my father. Hearing this, I felt joy I had never known. I told Fred not to act like the others who wanted to court me. They thought they might impress Father if they rode by our house in their church clothes and

craned their necks looking for me from their fine ponies to show off their families’ wealth. I knew Father would respect a man who wanted to work hard to support our family rather than a boy who looked for attention. Now, dancing with Fred, I was telling the People and Father who I wanted for my man.

As the sun rose, the dancing stopped, and there was a final meal as the young men gave presents to the girls they had danced with and a few announced they were ready to marry. I stood with Fred, my head bowed, smiling and knowing that soon he would ask Father for me and offer him the best bride gift he could. The gift he gave me for dancing with him was a blue shawl covered in woven white flowers. It was beautiful and warm, and I was very proud of it. I had no doubt that Fred Godeley would make the best of husbands.

Fred and I decided to wait two or three more years until we finished training school at Chilocco before marrying. Two seasons after my womanhood ceremony Father married again in the Season of the Ghost Face (January). I helped him and his new wife, Sousche, at his house after I finished my day at the mission school. Fred had not yet spoken with my father and was worried Father would want more for an appropriate bride gift than he and his family could afford. I told him my father knew he was a good man. The bride gift need not be grand.

In the Season of Little Eagles (March), I walked home from the mission school late one afternoon along burbling Medicine Creek. Meadow larks sounded their calls of joy in the deep prairie grass fast turning green, and the sun painted distant clouds in soul-filling colors. As I approached our village, I saw Father sitting on the edge of his house breezeway wrapped in his blanket, staring into the distant cloud colors over the land of his birth. I knew he must be wishing, as he had told me many times, that he had not stopped fighting the White Eyes. I also knew he wished he had some good White Eye whiskey to warm his insides.

I came to the breezeway and looked around but saw no sign of my stepmother or even lanterns lighted inside the house. This was strange.

“Father, where is Sousche?”

“Gone. I sent her home. She has no place with us anymore.”

I felt my face make funny wrinkles, part frown, part smile, as I sat down beside Father to watch the colors fading and changing on the far horizon.

“Why did you send her away?”

“She was lazy. You did all the work. She wouldn’t even keep me warm when the nights were cold.”

“I didn’t mind doing all the work if Sousche satisfied you. She seemed to give you comfort, but I’m glad you sent her away. I’ll still do all the work, and I’m happy to look after you.”

In the dimming light, Father reached in his vest and pulled out his tobaho pouch. He made a cigarette, smoked to the four directions, and then handed it to me. It had been only three seasons past my womanhood ceremony. He surprised me. He had never smoked with me before. I was still very young to be smoking over serious business, but I took the cigarette, smoked to the four directions, and felt it burn my nose and throat, but I was

determined not to cough as I handed the tobaho back to him. He smoked the last bit of tobaho then crushed the dying coal with his strong, calloused fingers.

He said, “I think you chose your man at your womanhood dance. Most women do. We should have talked before then, but I’ve had many things pulling my mind in other directions.”

“I understand, Father. Yes, I know who I want, and he wants me. He’s a very good man. I’ve watched him since we were children. We’ll be happy together. Soon he comes to you with a bride gift offer. I want you to accept it.”

Stars came to the soft blackness above us, and in the low glow on the horizon, we could see the steam come from our mouths as we talked. He said nothing for a while as we listened to the night birds and rustle of mice in the grass. He looked everywhere into the dark—toward the prairie, into the night sky, toward Cache Creek—everywhere except toward me.

“Father?”

He made a face and then turned toward me.

“Your young man must not offer me a bride gift. I won’t accept it. You can’t marry.”

I breathed hard, trying to pull air into my body that for a moment lost its life rhythms. It felt as if my heart had stopped, and then my eyes filled with quiet tears. It took a while for me to regain my heart’s balance as I swallowed the big ball of thorns in my throat. I croaked, “But, why? Father, I don’t deserve to be treated like this. I’ve worked hard and helped you all I could. Why are you doing this?”

“I know you aren’t happy I do this, but it’s to save your life. Listen. I want to tell you a story. My sister Ishton married the great warrior, Juh, who went to the Happy Land five harvests before your time. Before Daklugie was born, Ishton strained four days to deliver him and could not. As a di-yen, I did all I could for her, but I thought she would die. I went up on a mountain and prayed for her. Ussen heard me and said she and the baby would live and that I would die a natural death.”

Dogs barked a few houses away, and we heard the clink of harness chains as men brought their teams from newly planted fields to the barn.

“Other women in our family have died or nearly died having children. Their suffering has been great. That is what happens to the women in our family. My Power from Ussen tells me that if you try to have a child, both you and the child will die. You must not take a husband. Hear me and obey me. Do you understand?”

I sat there a long time, stunned, saying nothing, thinking, I’ve had no visions, nothing to tell me anything like this. In the normal course of my life, I expect to marry and have children to carry on my father’s line. Now, his power says I can’t marry. How can he tell me this?