BEHIND

by Paul Bishop

In the months ahead, new issues will focus on a variety of famous historical locations throughout the West, and we’ll be seeking original stories, articles, and poetry set in and around the specific places listed below.

Winter 2023—CochiseCounty,Arizona

Summer 2024—Leadville,Colorado

Winter 2024—CaliforniaGoldRushCountry

Summer 2025—Deadwood,SouthDakota

Winter 2025—KansasCity,Missouri

Deadline for submissions is February1 for all Summer issues and August1 for all Winter issues.

Saddlebag Dispatches is seeking original, previously-unpublished short stories, serial novellas, poetry, and nonfiction articles about the West. These will have themes of open country, unforgiving nature, struggles to survive and settle the land, freedom from authority, cooperation with fellow adventurers, and other experiences that human beings encounter on the frontier. Traditional westerns are set west of the Mississippi River between the end of the American Civil War and the turn of the twentieth century. The western is not limited to that time, however. The essence is openness and struggle. These things are happening now as much as they were in the years gone by. Short fiction and nonfiction submissions should be no more than 5,000 word in length and no less than 2,000 words. Due to space considerations, poetry submissions should be no longer than one page in length (approximately 30 lines).

QUERY LETTER: Put this in the e-mail message: In the first paragraph, give the title of the work and specify whether it is fiction, poetry, or nonfiction. If the latter, give the subject. The second paragraph should be a biography between one hundred and fifty and two hundred words.

MANUSCRIPT FORMATTING: All documents must be in Times New Roman, twelve-point font, double spaced, with one-inch margins all around. Do not include extra space between paragraphs. Do not write in all caps, and avoid excessive use of italics, bold, and exclamation marks. Files must be in .doc, or docx format. Fiction manuscripts should be in standard manuscript format. For instructions and examples see https://www.shunn.net/format/story.html.

OTHER ATTACHMENTS: Please also submit any pictures related to your manuscript. All photos must be high-resolution (at least 300 dpi) and include a photo caption and credit, if necessary.

Manuscripts will be edited for grammar and spelling. Submit to submissions@saddlebagdispatches.com with your name in the subject line.

By Sherry Monahan

By Sherry Monahan

AS USUAL, WE have a lot going on in this issue of Saddlebag Dispatches. This time, we’re bringing you the sights, sounds, faces, and characters of old Dodge City.

A young couple starts life together in the unlikeliest of places. We have a Chinese moonshiner, a half-breed Kiowa deserter, a cowboy who’ll do anything to keep a secret, another bound by a vow he must keep, and a young boy who grows into a man but at a terrible price. And all of that just from the short stories in this issue.

We’ve got Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, Doc Holliday , and “Squirrel Tooth” Alice. Terry Alexander and Paul Bishop take on the Dodge City denizens of Hollywood and the television screen. In Regina McLemore ’s column on Fort Dodge, we meet such notables as Grenville Dodge, Phil Sheridan, George Custer, Dull Knife, Satanta, Kicking Bird , and Standing Bear . Anthony Wood ’s feature details the events and importance of Fort Dodge to both the founding of the city and the trade along the Santa Fe Trail .

We have an excerpt from Bill Markley ’s excellent book, Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson: Lawmen of the Legendary West, a 2020 Will Rogers Medallion Award finalist in nonfiction, and another from Thunder Over the Prairie: The True Story of a Murder and a Manhunt by the Greatest Posse of

All Time by New York Times bestselling nonfiction author Chris Enss and her writing partner, Howard Kazanjian.

Last, but certainly not least, George “Clay” Mitchell interviews the afore mentioned producer/director Howard Kazanjian who not only was a producer for the Star Wars and Indiana Jones series but was second assistant on The Wild Bunch and has co-written with Chris Enss two biographies of Roy Rogers and Dale Evans, The Cowboy and the Senorita and Happy Trails. They also collaborated on The Young Duke: The Early Life of John Wayne and Thunder Over the Prairie.

We are proud to present the winner of theThird Annual Saddlebag Dispatches Mustang Award for Western Flash Fiction, P.A. O’Neil’s “The Great Burro Revolt,” as well as the other three finalists: Brandon Barrows’s “Use Your Head,” Sharon Frame Gay’s “Tricks of the Trade,” and Donise Sheppard’s “Strong Enough.”

There’s still ample time to enter the First Annual Longhorn Prize for Western Short Fiction. Stories of 2,000 to 5,000 words are accepted until August 1st. Please use standard Shunn manuscript format with no headers or footers in your submissions. First prize is $300 and publication in ourWinter 2023 issue coming out in December.

Finally, it is with deep sadness that I must an -

nounce the passing of two great western writers, Bob Giel and Velda Brotherton . Bob was my Managing Editor and strong right arm here at Saddlebag Dispatches, as well as the author of his own great western novels. Velda was a legendary journalist, mentor, teacher, adventurer, short story writer, novelist, and my go-to writer when I needed a special feature. She never failed to deliver near-perfect copy on time about any subject I threw at her. It breaks my heart to say goodbye

to these two fine people. They were more than just colleagues and business partners, they were true friends we will all miss. They’re now sitting around the campfire with our co-founder, Dusty Richards , and I’m sure they’re swapping lies and tall tales over coffee. Maybe I’ll hear them myself one day.

—DENNIS DOTY Publisher by GEORGE “CLAY” MITCHELL & VICTORIA MARBLECopyright 2017, Published by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

THE CONCLUSION OF the Civil War brought great prosperity to the northeastern United States and with it a change in the consumer’s taste from ubiquitous pork to beef roasts and steaks. Cattle prices in the north soared. By contrast, the south, with the burning of its major cities and the plundering of what little wealth remained, became poverty-stricken. Fortunately for bold Texans, wild longhorns numbered in the hundreds of thousands in Texas, free to anyone with the courage and will to round them up and drive them to market. Money was being made. So much that British investors, often the non-inheriting heirs of nobility, formed investment partnerships and purchased enormous ranches. Surely the wealth would flow unfettered for decades.

Except that the cattle business was a commodity like any other, subject to the normal factors that drive any market. Cattle Kingdom explores the boom bust cycle of the age when cattle was king and examines the many reasons for its inevitable demise.

Knowlton tells a story as brilliantly as the best cinematographer. His narrative pans in and out from individual players such as English entrepreneur Moreton Frewen of the Powder River Cattle Company, cowboy Teddy Blue Abbot, and to

broader views of the cattle business such as its role in the growth of cow towns like Dodge City to the development of barbed wire and refrigerated railroad cars.

Cattle Kingdom is a cautionary tale about the greed of men, the inevitable advancement of technology, and the unpredictability of Mother Nature. Any student of economics or the Old West should add this one to their reading stack.

Rating: 4.5 Nuggets (out of 5)

CattleKingdom by Christopher Knowlton

DodgeCity by Matt Braun

CattleKingdom by Christopher Knowlton

DodgeCity by Matt Braun

Copyright 2006, Published by St. Martin’s Press.

DODGE CITY WAS the end of the trail. Texas cowhands, coated in trail dust and flush with cash, couldn’t wait to see the elephant. Of course, that sometimes brought them into unwanted contact with lawmen like the Masterson brothers or Wyatt Earp, who had their own ideas about frontier justice. Defense attorney Harry Gryden was often all who stood between the rambunctious cowboy and a noose—deserved or not. Everyone accused of a crime had the right to a defense, regardless of how heinous the crime or guilty the accused. Gryden was good at his job. Maybe he was too good. When one too many guilty men walked due to Gryden’s slick tongue, he becomes a wanted man—by both sides.

Throughout this character study of defense attorney Harry Gryden, Braun weaves historical events and figures into the narrative as he follows Gryden through the year 1878. Western dignitaries Bat Masterson, Wyatt Earp, Luke Short, and Doc Holliday play important roles in the story line, and Braun brings them to life on the page. Courtroom drama, barroom battles, and gun fights in the streets of Dodge all create plenty of conflict and the western action readers of the genre enjoy. However, Braun missed opportunities to create tension,

which is lacking from the entire novel. Situational outcomes were predictable, and courtroom arguments bordered on cliché thanks to our nightly doses of television dramas.

Braun has written an enjoyable read full of characters as interesting as a traveling show. The prose, while stylistically somewhat out-of-date, is engaging and smooth. Despite its flaws, this quick read is worth picking up.

Rating: 3.5 Nuggets (out of 5)

Copyright 2019, Published by Wolfpack Publishing.

A SOILED DOVE shot lawman Ben Stillman in the back, leaving him hobbled and forcing him into retirement. Three years later, Stillman’s back is crippled up, and he plies his time sipping whiskey and gambling. That is, until young Jody Harmon shows up with a story about his father, Milk River Bill Harmon, Fancy Dan Hobbs’s attempts to forcefully buy all the homesteads on the Two Bear range, and the mysterious murder of Bill Harmon. The territorial marshal is too far away, and the local sheriff won’t investigate, leaving Jody with no other option than to involve Stillman, who had been friends with the elder Harmon twenty years prior. Unsure he’s up to the task, Stillman nonetheless eventually agrees. But Hobbs has hired Weed Cole to defend his ranch and chase off the homesteaders. Cole’s reputation makes the devil seem a saint, ensuring the deck is stacked against the already unsure Stillman.

Brandvold’s portrayal of Stillman, a man with physical limitations and significant self-doubts, generates both sympathy and frustration. His demons aren’t stereotypical, which makes Stillman an even richer character. Jody is full of the cocky rashness of a typical teenage boy, yet has grit and determina-

tion that has the reader pulling for him. As for the plot, following the twists is like watching a cowboy twirl his lariat—spinning and dipping until it finally snaps out and snares the reader.

Once a Marshal demonstrates why Brandvold is a popular author. Saddle up because this one’s an ornery critter with game.

Rating: 4 Nuggets (out of 5)

Despite their wild west cachet, Tombstone, Abilene, Wichita, and any other legendary gunfight and cattle drive destination lacked the same depth of instant association with the Western as Dodge City. While Tombstone may arguably come in a close second, Dodge City—renowned as The King of the Cowtowns or reviled as The Sodom of the West—was unmistakably the world-wide touchstone that instantly evoked every aspect of the Wild West burned into our brains by uncountable Western movies and television shows. In Dodge City, the legendary Wyatt Earp walked boldly alongside the equally legendary Matt Dillon, with popular culture seeming to make no discernable dividing line between the real and the fictional.

I wasn’t raised on iconic Dodge City-centric Westerns such as Gunsmoke, Bat Masterson, or The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp. The closest I came to Westerns growing up was watching after school reruns of The Rifleman. However, despite the coolness of Lucas McCain’s rapid fire rifle work, once the pseudo-espionage world of James Bond and The Man from U.N.C.L.E. took over the movie theaters and TV channels, I happily embraced the era of suave spies, deadly gadgets, megalomaniacal villains, and girls.

While The Magnificent Seven and The Profession-

als kept the door to Westerns open for me, it wasn’t until the proliferation of streaming channels that I discovered the joys of the aforementioned Western series as well as so many others from Wanted Dead or Alive to Rawhide, Have Gun Will Travel, The Wild Wild West (my cross-over drug), and the amazing proliferation of so many other shoot-em-ups and horse operas.

Gunsmoke, Bat Masterson, and The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp also played their part in what, in my case, has become a bone deep obsession with the Western genre in all its forms. It was that obsession that is at the heart of the Six-Gun Justice Podcast and has sustained my enthusiasm for over 200 episodes.

The year before COVID turned the world upside down, I had the opportunity to travel to Wichita to deliver the keynote address at the annual Kansas Writers Conference. The gig was also the excuse my wife and I needed to make a very roundabout pilgrimage from Lawrence, Kansas, where we have family, through Abilene, and then on to Dodge City, before winding our way to Wichita and the conference.

I didn’t know what to expect in Dodge City. Would it now be just another city, or would it retain something of its Wild West, or in actuality, Wild Mid-West history. I was concerned when

I learned The Boot Hill Museum was the main tourist attraction. However, my anxieties proved unfounded as the museum was everything I could have hoped it would be. And since we visited, it has been expanded to almost twice its size and would be well worth a trip back. In the city itself there was enough of a Western legacy to make the road trip worthwhile, and as touristy as it was, there was indisputably a special Western connection standing next to the larger than life statues of Matt Dillion and Wyatt Earp at the city center.

With this issue’s focus on Dodge City, I thought I would move on from reminiscences to see what

Dodge City-related books I have in arm’s reach on my bookshelves. First up was Tom Calvin’s seminal Dodge City: Wyatt Earp, Bat Masterson, and the Wickedest Town in the American West. This was a fascinating and very readable story of true friendships, romances, gunfights, and adventures shared by a remarkable cast of characters, including the titular Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson, as well as so many other recognizable names such as Wild Bill Hickock, Jesse James, Doc Holliday, Buffalo Bill Cody, John Wesley Hardin, Billy the Kid, and Theodore Roosevelt. If I had to pick one Dodge City book to recommend, this would be it.

A close second, however, would be another title from my shelf, Dodge City and the Birth of the Wild West. Authors Robert R. Dykstra and JoAnn Manfra looked through the lens of how cultural myths arise to see how Dodge City, of all the violent cities associated with the Wild West, was the only one to spawn a specific warning sobriquet—as in, Get outta Dodge.

One of my favorite books with a connection to Dodge City is Richard O’Connor’s Bat Masterson biography, which provided the basis for the Bat Masterson television show starring Gene Barry. While there were various editions of this book, the most highly sought after (and therefore expensive) is the paperback tie-in to the TV show featuring Gene Barry in his Bat Masterson garb on both the front and back covers. While a bit of a slow read by today’s standards, and having little to do between the covers with the actual TV show, I found it intriguing enough for me to seek out O’Connor’s other biographies of Western legends, such as Wild Bill Hickok and Pat Garrett.

As I am an aficionado of Western TV tie-in novels, I couldn’t pass up the chance to talk about the

show that has done the most to cement Dodge City in the public consciousness—Gunsmoke. As benefits the longest running and arguably most popular TV Western, Gunsmoke, along with Bonanza, generated substantially more TV tie-in novels than any other Western TV shows.

The first Gunsmoke tie-in appeared in 1957. Simply titled Gunsmoke, it was a collection of ten show scripts novelized by Don Burns . This was followed in 1970 by an original Gunsmoke novel—also simply titled Gunsmoke —written by Chris Stratton . Next came The Man from Alberta in 1973, a standalone Gunsmoke novel written by Canadian journeyman hack, James Moffatt . Published in England only, this one is strictly for completists as it’s obvious from reading the book Moffat had never seen an episode of the show and was probably working strictly from character sketches of the main participants. Copies can be found, but you’ve been fully warned.

In 1974, Award Books published four authorized Gunsmoke novels written under the pseudonym Jackson Flynn. To the best of my knowledge, the second book in this series, Shootout, was written by

top Western writer Gordon D. Shirreffs with the other three books, The Renegades, Duel At Dodge City, and Cheyenne Vengeance written by Don Bensen about whom I know nothing. However, what’s unusual about this tie-in series is the books written by Bensen are all novelizations of Gunsmoke scripts—the first book being adapted from the 1973 two-part episode, “A Game of Death an Act of Love,” by Paul F. Edwards—while the book written by Gordon Shirreffs is an original tie-in novel. This is the only example of a series of TV tie-ins of which I’m aware that is a mix of both novelizations and original novels. It’s usually one or the other.

First run episodes of Gunsmoke appeared on CBS for twenty years, but currently, at any given moment, there is an episode of Gunsmoke being rerun somewhere in the world with Matt Dillon keeping the streets of Dodge City safe. This has kept Gunsmoke fandom thriving. In 1999, twenty-five years after Gunsmoke was cancelled by CBS, Boulevard Books commissioned a three-book series of original Gunsmoke novels, Gunsmoke, Dead Man’s Witness, and Marshal Festus, written by the prolific and always readable Gary McCarthy .

These can be easily tracked down at a reasonable price on eBay or from other sources and are all worth reading.

Whitman Publishing also jumped on the Gunsmoke bandwagon with two of their “board book” TV tie-in novels for young readers. The first, again simply titled Gunsmoke, was written by Robert Turner and appeared in 1958. Gunsmoke: Showdown on Front Street, written by Paul S. Newman , was published in 1969, over ten years later, showing the enduring popularity of the show. For completists, there was also a 1958 juvenile Big Little Book, also simply titled Gunsmoke, written by Doris Schroder .

However, the latest iteration of Gunsmoke tiein novels hit the bookshelves in 2005. The six books in the series, Blood Bullets and Buckskin, Blizzard of Lead, The Last Dog Soldier, Dodge the Devil, The Reckless Gun, and Day of the Gunfighter, were published in paperback by Signet and written by respected Western stalwart Joseph West . Each entry in the series contained a forward by James Arness voicing his appreciation of the novels, which was a unique touch for a tie-in series. It’s

also notable that the name Gunsmoke emblazoned across each cover was followed by the trademark symbol for the first time. This series was my favorite of all the Gunsmoke tie-ins, and I highly recommend it.

That’s it for the Dodge City-related books I can quickly lay my hands on from the bookshelves nearest me. They all provided excitement and have the ability to transport readers to the dusty and dangerous streets walked by legends we all know.

—PAUL BISHOP is a well-known novelist, screenwriter, and Western-genre enthusiast, as well as the co-host of the Six-Gun Justice Podcast, which is available on all major streaming platforms or on the podcast website: www.sixgunjustice.com/

1936—2023

IT IS WITH overwhelming sadness that we mourn the passing of the one and only Velda Brotherton . She was our friend, our mother, our mentor, our matriarch. The glue that held us all together. A talented, multi-genre author, an award-winning journalist, a dogged adventurer. Perhaps most of all, though, she will be remembered as the wise, patient, and loving teacher of the generations of writers who passed through the Northwest Arkansas Writers’ Workshop over the past thirty-five years.

When her longtime friend and writing partner, legendary Western author Dusty Richards, passed away five years ago, all anyone could talk about was how there would never be another one like him, but the very same thing can be said about Velda. She was larger than life in her very own right and could light up a room with her mischievious grin and that sparkle in her eye. She had

the kind of fun-loving, devil-may-care spirit that got her and many of her fellow writers in trouble with venues when they got a little too raucus and rowdy. Brilliant, kind, patient, loving, beautiful in body and soul, she could make you laugh one minute with her singular wit and cry the next as you poured out your heart to her… or vice versa.

Velda was an inspiration to every person she met and every writer she helped mentor, and she will be missed by all. For our part, her passing leaves a hole in our lives that can never be filled. She was not only our colleague and business partner, but our friend, as well. Consolation only comes with knowing she’s now free from her suffering and probably sitting around that big campfire in the sky with her buddies Dusty and Pat Richards and her beloved husband, Don Godspeed, Velda. You will be forever in our hearts and never forgotten.

WITH HEAVY HEARTS, we say goodbye to our good friend and Saddlebag Dispatches Managing Editor, the one and only Bob Giel.

Bob was not only a fantastic writer and editor, he was also one of the finest and truest people you’ll ever meet. Despite being a born-and-bred New Yorker living in New Jersey, he was a cowboy at heart and lived by the cowboy code. When most of the world today laughs at the quaint and seemingly antiquated concept of honor, he embodied it. Always faithful. Always loyal. Always giving his best effort. Always honest. And perhaps most importantly, keeping his word no matter what.

If you’d ever had the privilege of hearing Bob speak about meeting Roy Rogers and Trigger as a child—something that brought him to tears with every retelling—you knew his values weren’t just an act or an affectation but something he worked at

and recommitted to every day. Bob was more than just a cowboy, though. He was also just a good person. A caring, generous, and ebullient spirit—vital, energetic, optimistic, and always ready with a kind word and a zillion-watt smile. Whether you knew him as “Tiny Bob,” ”Little Bob,” “Gunfighter Bob,” or “Dirty Wiener Bob”—a tongue-in-cheek reference to an incident involving a dropped hot dog during a summer writing retreat—you knew a great man with a heart bigger than he was. He lived and loved life to the fullest and cherished his friends and family to the same degree. To say that the world is a little darker with his passing, a little more dreary and cruel, would be an understatement.

We will cherish Bob and his memory forever and aspire to be just as good, as kind, and as honorable as he was with every passing day.

Happy trails, cowboy. We’ll see you again at the end of the drive.

NELLIE DABBED HER teary eyes and sniffled. The past twenty-four hours had been the hardest of her life, hearing about Luke’s gunfight and death, then burying him. Her son, Austin, seemed to think life would get easier with time, but Nellie wasn’t sure any amount of time would ease the pain of losing her husband of eighteen years.

“You’re stronger than you think,” Luke had told her a few days before he was shot. “You’re tougher’n me, that’s for sure.”

But she didn’t feel tough. She felt weak and vulnerable—like her heart had been ripped from her chest and buried with her husband.

She glanced away from the grave at the stranger standing ten yards away.

Austin took her hand and gently squeezed it. “Come on, Ma. We should get home.”

She let him lead her away from the grave, and the strange man watched them go.

THERE WAS A knock on the door, and Nellie rose to her feet. She opened the door and saw the stranger from Luke’s funeral standing there, hat in hand.

“Good evening, Miss Bennett. I was hoping I could have a word with you?”

Nellie looked the strange man up and down. “I’m sorry, Mister...?

“Cassidy.”

“Mister Cassidy. I don’t believe we’ve met.”

He glanced over her shoulder at Austin, then back at Nellie. “May I come in?”

Nellie’s heart raced. There was something about the man that unnerved her, but she stayed calm. “It’s late, Mister Cassidy. We can talk right here.”

He nodded but didn’t look pleased with her refusal.

“What can I do for ya, Mister Cassidy?”

“First, I’d like to say I’m sorry for your loss. Mister Bennett was a fine man.”

Nellie dropped her gaze for a moment, her eyes stinging with the threat of tears.

“I know this isn’t the best time, but before he died, your husband sold me this land.”

Nellie stiffened and narrowed her eyes at him. He seemed to squirm under her gaze.

“Now, Miss Bennett, I think you’d be far more comfortable in something a little smaller. If you’d like, I can talk to an associate and get you and your boy settled in a home not five miles from here. I can even keep your boy on as a ranch hand, if he so wishes.”

She felt Austin step up behind her, but Nellie held up a hand to stop him.

“Who do you think you are?” Austin seethed.

“It’s okay, Austin. There’s no need to be rude. Thank you for your offer, Mister Cassidy, but Austin and I are just fine here.”

A dark smile spread across his face. “Perhaps I didn’t make myself clear, Miss Bennett—”

“It’s Missus Bennett.”

Cassidy inclined his head slightly. “I only came out of courtesy. Mister Cassidy and I already came to the agreement. Money has exchanged hands. You and your son are officially trespassing.”

Nellie’s lips trembled. She opened her mouth to argue, but no words came.

“Pa wouldn’t have done that!” Austin yelled. “You’re a liar!”

Mr. Cassidy sucked his teeth. “Well, I’m afraid he did, son.”

Nellie’s mind reeled. Why would Luke do such a thing without telling her?

“Miss Bennett, if moving out is a problem, perhaps you and I could come to some sort of arrangement?”

His calloused hand stroked hers, and she pulled away. “Mister Cassidy, you’ve made some sort of mistake. My husband wouldn’t sell this ranch.”

“But he did.”

“Do you have the bill of sale? The deed?”

His eyes flashed. “Listen to me, woman!” he snarled. “Your husband sold me this land!”

“I don’t believe you… and my husband is no longer here, sir.”

He gritted his teeth, his lips pulling tight.

“Now, if you’ll excuse me, Mister Cassidy, I have chores to do around my ranch.

Cassidy lunged forward and grabbed her by the wrist. “Do you take me for a fool? I want you and your son off my property by tomorrow, or I’ll be forced to treat you as squatters and take matters into my own hands. And I promise you, tomorrow I won’t be as courteous.”

Nellie snatched her hand away. “Get away from here, you... you....”

Cassidy put his hat on. “So be it. You’ve brought this on yourself. I’ll be back tomorrow with my men.” He turned on his heel, his boot grinding the wooden porch, then stalked away.

Nellie stared after him, the threat ringing in her ears. She grabbed Luke’s hunting rifle from beside the door and took aim. “Mister Cassidy!”

Cassidy turned, his eyes widening, and Nellie pulled the trigger. The shot hit him in the chest, and he fell to the ground. Nellie panted, staring at Cassidy’s body lying in the dirt. She barely registered Austin yanking the gun away from her.

“You shot him!”

Nellie stared at him like she didn’t know him.

“Ma!”

She blinked, and everything came into focus.

“We need to get rid of the body,” Austin said, his voice high with worry.

Nellie nodded and sucked in a deep breath. Now wasn’t the time for a conscience.

TWO WEEKS LATER, while Nellie set wildflowers on Luke’s grave, a man watched her, but this time, instead of ignoring the stranger, Nellie approached him.

“Can I help you?” she asked.

“I’m looking for an associate of mine. Mister Sean Cassidy. Have you seen him?”

Nellie resisted smiling and shook her head.

“’Fraid I don’t know anyone by that name.”

The man stared at her for a moment. “I must be mistaken, then.”

“Seems so,” she agreed, holding his gaze until he tipped his hat and walked away.

Luke had been right. She was much stronger than she thought. He’d been gone for a fortnight, and she was surviving. Perhaps she was tougher than him, after all, because she didn’t hesitate to pull the trigger, and wouldn’t when this second gentleman came calling, either.

—DONISE SHEPPARD is a multi-genre author residing in southern West Virginia with her husband and four children. Donise found her passion for books at an early age and has been chasing stories ever since. She is an author, editor, and co-owner of Pixie Forest Publishing. Follow her at www.facebook.com/authordonisesheppard

“Lawmen, cowboys, songbirds and soiled doves…it doesn’t get much beter. A shootng, a chase and a trial whose verdict changes all of their lives. Thunder Over the Prairie is a great story from the history of our American West, warts and all.”

Dakota & Sunny Livesay, Chronicles of the Old West

A fast-paced, cinematc glimpse into the Old West that was. Follow future legends of the Old West Charlie Basset, Bat Masterson, Wyat Earp, and Bill Tilghman as they hunt down a murderer in a ride across a desolate landscape to seek justce.

Thunder over the Prairie

The True Story Of A Murder And A Manhunt

By The Greatest Posse Of All Time

CHRIS ENSS & HOWARD KAZANJIAN

978-0-7627-4493-0 • Paperback • $14.95

Wild Bill Hickok and Bufalo Bill Cody Plainsmen of the Legendary West BILL MARKLEY -

ILLUSTRATED BY

JIM HATZELL

TwoDot

978-1-4930-4842-7

Paperback • August 2022 $24.95

Polly Pry

The Woman Who Wrote the West

JULIA BRICKLIN

TwoDot

978-1-4930-6378-9

Paperback • April 2022 • $19.95

978-1-4930-3439-0 • Hardback

September 2018 • $24.95

The Trials of Annie Oakley

CHRIS ENSS & HOWARD KAZANJIAN

TwoDot

978-1-4930-6377-2 • Paperback

April 2022 • $19.95

978-1-4930-1746-1 • Hardback

October 2017 • $24.95

Before Billy the Kid

The Boy Behind the Legendary Outlaw MELODY GROVES

TwoDot

978-1-4930-6349-9

Paperback • August 2022 • $21.95

All available at rowman.com, wherever books are sold, or via Natonal Book Network: 1-(800)-462-6420

THE MOON’S ONLY a sliver tonight, slicin’ through the sky. Stars poke through wispy clouds, riding a light wind. The desolate valley is painted in deep shadows.

The silence surprised me as I nudged my horse, Buck, through the brush. You’d think the whole desert would be singin’ out now that the sun was down and took its heat with it. Even under the cloak of a dim night, New Mexico was tired and yearned to sleep it off, like some old drunk back at The Velvet Slipper.

It gives me the shivers to think about what happened there tonight. Why, that saloon wasn’t fit for prairie dogs, much less to cater to people. It was bad enough the women, although loose as a lope, were ugly, but the drinks were so watered down I could read through the glass they served it in. On top of that, some card sharp in the corner was doing his best to fleece every cowboy who walked in, including me.

I admit, I took to the shakedown easily enough. A brash blonde with amber eyes sidled up in a cloud of perfume and smiled. To say she was

homely would be a kindness, but I’d just spent three weeks on the trail. So, I figured a drink or two might make her pretty.

The fact that she kept pouring my favorite whiskey for free should have been my first clue somethin’ was wrong. But I lapped it up like Buck does when he meets up with a cool stream on an August day.

I didn’t realize rooms could spin and informed the entire saloon about my revelation. To stop the swirlin’, I let the blonde sit me down at the table with the card swindler. Even though my eyes were dancing in my head, I couldn’t help but notice his oily smile was jagged-toothed and eager, like a wolf stalking a lamb.

When he dealt the cards, I held ’em in one hand and sipped another drink with the other. Before you know it, I was squeezing some coins out of my pocket and tossing ’em on the table like a seasoned gambler, confident in my inebriation and arrogant enough to believe in myself.

Then things got serious. It wasn’t long before every single cent I possessed had found its way into the dealer’s pocket, and all that was left were the

stains on the table from my sweating glass and a handful of marked cards splayed out like a fan.

That’s when it appeared I’d been taken. By the card sharp. By the woman. And by my lack of common sense, it seemed. I looked around the saloon and tried to get up but tumbled across the table. It crashed to the floor, taking everything with it, including me.

I lurched to my feet, then reeled around the chairs, knocking into them and hollerin’ that they needed to be hobbled to keep ’em from moving around so much. But that wasn’t enough, I suppose. My body decided now was as good a time as any to just lie down altogether, right there in the middle of The Velvet Slipper.

I heard somebody mumbling and realized it was me. Peering up, I saw the glare of disgust on the swindler’s face as he angled himself away from the broken table and clutched at the blonde. I dragged myself over and held on to his legs for dear life.

“Help!” was all I could muster in a pitiful voice.

Sneering, he tried to shake me off, but I held on until he clocked me on the chin with his fist.

“Don’t bring any more of these fools in here tonight, Lorna,” he snarled and spat on the floor. “It’s too easy. I swear there’s no challenge lately. I’m done!”

The scoundrel left in such a huff, he forgot his fallen bowler hat and silk handkerchief. He didn’t even stoop to pick them up off the floor where I was now residing.

The rest of the folks in the saloon must have decided I didn’t look half bad as a new rug because they let me linger where I fell.

The swinging doors looked far away, like when you peer through the wrong end of a bottle. Squinting, I decided to wander over there without botherin’ to stand until the bottom of the door smacked me on the forehead.

Somehow, I spilled out of the saloon and found Buck waiting patiently at his post. After a few good tries, I got my foot in the stirrup and hauled myself up. Buck groaned under my weight and tossed his head in complaint.

I slumped forward over his neck, nudged him with my heels, and we picked our ragged way down the street. Then I straightened and gave him his lead. He broke into a slow jog.

When we reached the edge of town, I tapped him with my spurs. Buck launched into a gallop. I rode for what seemed like hours until I stopped behind a boulder and peered around. The desert was as empty as a nun’s bed.

I got off, stretched, then took a big swig of water from the canteen. It slid down the throat cool and easy, just like the water I kept dribbling into my glass of whiskey when the blonde wasn’t lookin’.

I reached into my saddlebag, bringing out all the money the card swindler made tonight off the cowboys, before stuffing it into his pants pocket.

The same pocket I picked when I grabbed his legs and pretended I was drunk.

I took another slug of water and smiled.

Sometimes the lamb fleeces the wolf.

After climbing back on Buck, I jammed the bowler hat on my head and turned toward another goodbye town, the sliver moon pointing the way.

SHARON FRAME GAY lives in Washington State with her little dog, Henry Goodheart. Although she is a multi-genre author, she has a special fondness for writing Westerns. She is also published in many anthologies and literary magazines, including Chicken Soup For The Soul, Saddlebag Dispatches, Crannog Magazine, Lowestoft Chronicle, Thrice Fiction, Literally Stories, Literary Orphans, Adelaide, Scarlet Leaf Review, Indiana Voice Journal, and others. She has won a Will Rogers Medallion for one of her Western short stories and been nominated twice for the Pushcart Prize.

SWEAT GREASED MY palms, slicking the reins I held. I wiped one hand against my denims, then the other, hoping Dixon wouldn’t notice. His horse, to my right, was calm, but mine made a nervous little sidestep. I knew the feeling.

On the cusp of the ridge ahead, Gilford knelt, field glass to his eye. Dixon, sitting on a rock, smirked faintly at nothing that I could see.

“Scared, kid?” Gilford asked without turning, breaking the stillness. Silence did me no good, but neither did the question.

“Leave him be,” Dixon answered. His smirk turned to me. “He’ll be fine.”

“Yeah, I’m all right,” I lied.

Gilford laughed. “He’s jumpier’n a hog in a damn slaughterhouse.”

“He’s fine,” Dixon repeated, lookin’ square at me. “Hart’s got his brother’s gun, and he remembers why he’s here, don’t you, Hart?”

A month earlier, my brother, Lincoln, was shot during a robbery gone straight to hell. Somehow,

Dixon, Gilford, and Lincoln all managed to escape, but Linc didn’t last the night.

When Linc died, grief came first, but nearly overwhelming fear followed. I wasn’t part of the gang, only a tagalong Dixon tolerated because I was Linc Prescott’s younger brother and had nowhere else to go. I expected to be out on my keister—sixteen, skint, and alone in the world.

Cloyd Dixon surprised me, though. He only said how sorry he was the job went badly. “Badly” did it no justice, but I kept quiet, from fear of and respect for the man keeping me fed.

Weeks passed. Cloyd treated me good, and Gilford—well, he didn’t treat me bad, just sort of ignored me. I began to forget the fear. Finally, when Dixon suggested I start earning my keep, there seemed no choice. I was scared all over again, but I owed him.

“I’ll remember.” I pushed the other thoughts aside.

Dixon stood, taking his horse’s reins from me. “The job’ll be a cinch.”

“Ain’t there a marshal? Or a bank guard?”

“Why’d you bring up his brother?” Gilford complained. “Now he’s thinkin’—”

“Shut up,” Dixon snapped. “No guard, and the marshal’s laid up with a broke ankle. Heard it in town yesterday. Even if he weren’t,” he patted his holster, “this here makes folks take whatever you give ’em.”

“Unless they got a gun, too.” It just came out, but I knew right away it was the wrong thing to say.

Dixon was irritated. “Maybe, but if you got a gun and some smarts—look, just use your head, don’t do nothin’ stupid, and it’ll work out fine.”

“Clerk’s left the bank,” Gilford announced, sliding the glass into his pocket. “No sign of the manager.”

“He’ll be a while longer, I reckon.” Grinning again, Dixon swung into his saddle. “Let’s go.”

Ice in my guts, I mounted up.

DUST MOTES DANCED in the sunlight streaming through the bank’s tall windows. At almost five in the afternoon, the place was deserted aside from a beefy, well-dressed man behind the waisthigh counter.

Dixon was leadin’, me on his heels. Gilford stayed outside. The man behind the counter looked up and smiled. “Say, you’re the fellow I talked to about opening an account. Come to make that deposit?”

“Like to see your setup again,” Dixon replied.

“Certainly.” The man pushed open a gate in the counter and gestured for us to follow.

The room behind the public area was cramped, really just a hallway ending in the steel door of a vault. My mouth was dry, and the gunbelt across my hips never felt heavier.

“The vault’s brand new, see. The latest model—”

“Open it,” Dixon demanded.

“Actually—” The manager froze as he noticed the gun now in Dixon’s hand.

“Open it,” Cloyd repeated.

The banker’s fists clenched, but his voice held steady. “I can’t. It’s a timed lock. It won’t open until eight o’clock tomorrow morning.”

“Liar!” Dixon snarled, swinging the barrel of his Colt against the other man’s jaw with a vicious sound of metal on flesh. The banker went to his knees, mouth bloody. I felt sick.

Dixon leveled the gun at the man’s face. “Open the God-damned vault.”

“Let’s just go,” I blurted, suddenly desperate, feeling how wrong this was. Did Linc do this sorta thing? I couldn’t believe it. “He said he can’t open it.”

“He’s lying. He’ll—”

With a roar, the banker lunged for Dixon. Dixon sidestepped, barely escaping the bigger man’s grasp, raised his gun, and pulled the trigger.

Nothing happened. Jammed or a dud cartridge.

Dixon swore and uselessly pulled the trigger again and again as the banker closed in, red-stained teeth bared, face furious. I watched, frozen, as something in Dixon changed.

“Shoot!” Dixon shrieked, bravado gone, everything now suddenly different. Without the gun, it was like he wasn’t even Dixon anymore—like the weapon was more Dixon than the man was. In all the time I lived with him, I never learned as much about Dixon as in that moment.

“For God’s sake, Hart,” Dixon cried as the banker got a hand on him, “use your gun!”

I felt the weight of the six-gun on my hip—the same one my brother had carried. I remembered Lincoln, gut-shot, dying in agony. I’d probably nev-

er learn exactly how Lincoln ended up shot, but I could guess now, and I knew nobody deserved to die like that.

I remembered what Dixon said earlier, too. I knew good advice when I heard it.

Lifting the gun from my holster, I pushed between the other men, my weighted fist swinging low. Dixon doubled up, staggered, and sank down against the wall, pure confusion on his face.

I handed the gun to the stunned banker. “Better call for help, mister. Use the back door, though. There’s another fella out front on lookout.”

“What’re you doing?” Dixon squeaked.

“Just what you told me to do,” I said. “I’m using my head.”

As the banker hurried out, I put myself between Dixon and the door to await whatever came next.

And this time, I wasn’t scared.

—BRANDON BARROWS is the author of the novels Burn Me Out, This Rough Old World, Nervosa, and over fifty published stories, some of which are collected in the books The Altar in the Hills and The Castle-Town Tragedy. He is an active member of Private Eye Writers of America and International Thriller Writers. He is a regular contributor to Saddlebag Dispatches, as well. Find out more about Brandon and his writing on Twitter @brandonbarrows or on his website, www.brandonbarrowscomics.com.

BILLY WOKE TO his brother’s foot in his face. This wasn’t unusual, as he was one of four little boys who slept in the wide bed.

Billy, Richard, and their cousins, Sam and David, all lived at their abuelo’s hacienda.

Their mothers were sisters who had married brothers, and they all now lived at their father-inlaw’s ranch, the El Molino. The women split their duties, one rearing the children, the other tending to household management.

The bedroom doors to the porch were already open to catch an early breeze as Tia Fina pulled back the covers to reveal the tangle of arms and legs she found every morning. She ordered all to wash their faces and dress, so she could do their hair before breakfast. Billy, only six, was usually the last. Wearing a smock and knee pants, he stood with his back to her as she undid his shoulder-length braid, dragged a brush through his curly locks, and pinning them all up into a bun.

“Ouch, you’re hurting me!”

“Cállate!” Tia Fina’s response was as sharp as the stroke of the brush.

After breakfast each day, the boys bolted out the door to wander around the El Molino, mostly unsupervised, as long as they stayed out of the way of the ranchero’s peones.

This day, though, Billy doubled back and to find his mother as she helped one of the Pima women, hired servants, hanging up the laundry. He relished time spent with her, even just watching her hang sheets on the line.

Billy had waited until she reached down to face the basket before speaking, “Mama. Why does Tia Fina hate me?”

“She doesn’t hate you, mijo,” she replied as she hung another sheet. “Why do you say that?”

“She always yells at me when she does my hair. Last night, she called me criado con los indios, and it hurts when she pulls the burrs out.

“Mama, why do we have to wear our hair like this, and how come we have to wear these dresses?”

His mother knelt down and took his hand. “Mijo, it’s 1898, almost the turn of a new century. Our family has worked for years to help bring civilization to this part of Arizona. Little boys back East

dress like this, and have long hair, until they are almost ten.”

“Ten! I don’t know if I’ll live that long.”

He stumbled off to find the others petting a lone burro through the rail fence.

Richard asked eagerly, “What did Mama say?”

“She says we have to look like this until we’re ten.”

The collective groans drowned out the burro’s little bray.

“Why is this colt by himself?” David asked.

Sam scratched the burro’s ears under the halter. “He’s recently weaned. His mama is one of the ones they use on the mill wheel. He’s too small, I guess.”

Billy’s attention wasn’t on the animal. “I wish there was something we could do to make Tia Fina stop picking on us.”

“Oh, I know how to knock her down a few pegs.” Sam smirked.

“Sam... Sam, I don’t want to hurt Mama,” David cautioned.

Sam’s face lit up. “Richard, hold on to this burro. David, help me get this rail fence down.”

Billy giggled. “What can I do?”

“Run ahead to see if my mama is near our bedroom, and make sure the outer doors are open.”

Richard stepped over the downed rails into the pen. “What do you have in mind, Sam?”

“David, link your hand with mine so we make a kind of sling behind the burro’s rear. Careful, we have to stay close, so he doesn’t kick us. Richard, lead him toward the hacienda.”

Billy came running back to the others as they crossed the yard. “I couldn’t see her, and the doors are still open.” He softly clapped his hands and giggled. “What else can I do?”

Sam and David gently persuaded the colt from the rear while Richard tugged, holding the halter close under the burro’s jaw. “When we get to the porch, pull down the blankets on the bed.”

Billy’s eyebrows rose, and his jaw dropped, but silently, he trotted away to complete his mission. As the others approached their room, he made one last check that Fina wasn’t in the hall, then he pulled down the blankets on their large bed. His chest expanded with the thought that, if he were caught before the others came, it would be worth her wrath.

The boys whispered as they led the burro through the doors and toward the naked bed. Richard stepped up, pulling the animal along behind him, while the others tried to lift as they pushed. Billy covered his mouth with his hands as he watched them push it down upon the white linen. Then, they got off, pulling the covers up over the colt.

Everybody did their best to hide behind doors and furniture.

It wasn’t long before Tia Fina arrived. “Haven’t I told you boys not to play Hide-n-Seek in the house?” She pulled back the covers with a force.

The scream echoed throughout the hacienda and yard. Others came running, only to find a confusion of boys chasing a braying burro around the room and Fina yelling in Spanish that she wished she had a strap.

The others returned the burro to his pen, while the boys sat with their noses in the room’s four corners. No one was allowed to talk, and each was sure more punishment would come.

It seemed like hours before the women returned. With solemn voices, they called their children to them.

Billy and Richard approached Mama with downcast eyes. Her face was stern as she took each by the shoulders and turned them around. Billy squeezed his eyes, prepared for a spanking, but popped them open when he heard the snipping sound of her shears cutting the bun off his head.

—P.A. O’NEIL is descended from Arizona pioneer stock and has always had a love for the ways of the Old West. Her Smoked Irish heritage (Mexican and Irish) allowed for her to experience the world as a member of the minority and majority simultaneously. She is a graduate of Pacific Lutheran University and has worked for colleges, churches, and youth organizations. She has been writing for almost six years and has been published over thirty-five times in anthologies and online journals. A collection of her stories was published two years ago and has met with great success. Witness Testimony and Other Tales is available in paperback and Kindle format. Her article, “Northwest Passage,” about the Ellensburg, Washington Rodeo from the Summer 2022 issue of Saddlebag Dispatches is currently a finalist for the 2023 Will Rogers Medallion Award.

An excerpt from Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson: Lawmen of the Legendary West, a 2020 Will Rogers Medallion Award finalist for Best Western Nonfiction.

SEVENTEEN-YEAR-OLD Bat Masterson and his nineteen-year-old brother Ed had been working in western Kansas as buffalo skinners.

In the spring of 1872, the Santa Fe’s route was abuzz with railroad contractors and workers. The Santa Fe was paying top dollar to get the tracks laid in time. A member of a work gang could make two dollars a day, which was good pay in those days. The gangs were averaging more than a mile a day of track laid.

Bat and Ed, along with family friend Theodore Raymond, were looking for work. The Santa Fe contracted with a Topeka business, Wiley & Cutter, to grade the railroad track bed. Wiley & Cutter subcontracted with Raymond Ritter for some of the grading. Ritter offered Bat, Ed, and Theodore good pay to grade a five-mile section of track bed from Fort Dodge to Buffalo City. They accepted the offer, and, starting at Fort Dodge, they worked long

hours through the spring and summer until they reached Buffalo City in July, finishing their job.

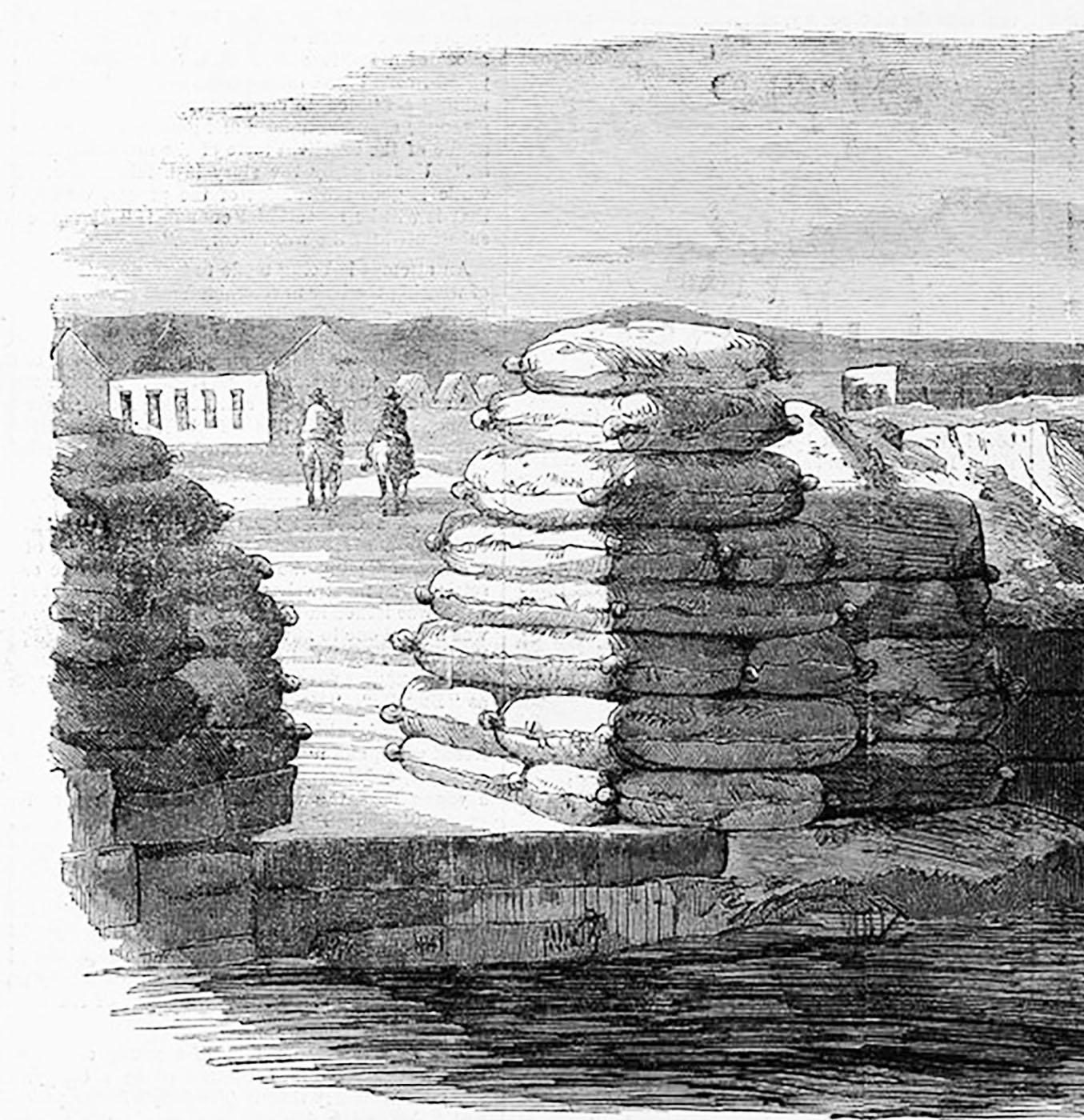

The town was booming when they got there. A. A. Robinson, the Santa Fe’s chief engineer, was laying out the town’s streets, and its name was changed from Buffalo City to Dodge City. The town was right in the heart of prime buffalo hunting territory, and now that trains could reach it, hides could be quickly transported east. The first train to town experienced a two-hour delay due to a threemiles wide and ten-miles long buffalo herd crossing the tracks. Not only did the trains haul buffalo hides east, but they also brought west saloonkeepers, gamblers, and sporting gals. Soon Dodge City acquired additional names: “Hell on the Plains” and “The Wickedest Town in America.”

Raymond Ritter met Bat, Ed, and Theodore in Dodge, and he paid them a small amount of the money he owed them for their efforts. He told

them he needed to get the balance of three hundred dollars from Wiley & Cutter. Ritter headed east, promising he would return shortly with the cash. Bat, Ed, and Theodore, low on cash, realized after several weeks that Ritter had duped them.

SHORT ON CASH due to Raymond Ritter’s dishonesty, Bat and Ed Masterson , along with Theodore Raymond, needed to earn a livelihood. They left Dodge, returning to the buffalo range. Riding southeast to Kiowa Creek, they joined hunting partners Tom Nixon and Jim White ’s large and experienced buffalo hunting camp. Late in November 1872, Jim Masterson , Ed and Bat’s younger brother, and Henry Raymond , Theodore’s younger brother, joined them. Henry kept a journal for 1872 and 1873, recording events in and around Dodge.

Ed and Bat had now graduated from skinners to buffalo hunters while the Raymond brothers and Jim worked mainly as skinners. Not only did they skin the buffalo for their hides, but they also butchered the carcasses and sold the meat in Dodge. Bat met and became friends with frontiersman and buffalo hunter, Billy Dixon, who later described Bat. “He was a chunk of steel, and anything that struck him in those days always drew fire.”

Henry Raymond’s journal entries are sparse but interesting. Here are a few:

Saturday, November 30, 1872: “Ed and Bat and me killed and butchered 17 buffalos. [sic] Jim pegged.”

Wednesday, December 11, 1872: “Bat, Abe, Ed, Jim, Rigny and me went to Indian camp to trade.”

Friday, December 20, 1872: “very cold day. Shook snow off hides. The[odore] and Bat went to Big Johns. Started to town. 4 bull whackers here to spend eve. Sang songs and played violin. Snowed.”

Wednesday, December 25, 1872: “Christmas day. Shot at a mark to see whos [sic] treat. Ed and me best.”

The buffalo disappeared from around Kiowa Creek. Tom Nixon headed back to his wife and ranch on the outskirts of Dodge. Bat, Ed, and the others de-

cided to follow his example and rode back to town on January 1, 1873. The Raymond boys, Ed, and Jim all boarded the train for home, but Bat stayed in Dodge. On nice winter days, he rode out buffalo hunting with Tom Nixon and Jim White. In the spring, he resumed full-time buffalo hunting. Henry Raymond and Ed Masterson returned to Dodge toward the end of February. Henry continued buffalo hunting and skinning, but Ed found a job in town working at Jim “Dog” Kelley’s Alhambra Saloon. Kelley’s nickname was “Dog” because he was known for his pack of racing greyhounds.

After the Santa Fe railroad came through Dodge City on its way to the Colorado territorial line, the town boomed. It rose from a tent city servicing off-duty soldiers to more permanent frame buildings serving as a booming marketplace where buffalo hunters sold their hides to be loaded onto freight cars and shipped east. The hunters bought supplies and ammunition. They spent their money on drinking sprees, gambling, and women. Within a year of its existence, fifteen men had been killed and buried in the new Boot Hill cemetery. Residents formed a vigilance committee arbitrarily dispensing justice as they saw fit. Henry Raymond, still journaling and writing detailed letters, witnessed killings sanctioned by the vigilance committee and murders committed in the open. For instance, on Thursday, March 13, 1873, hearing gunshots, Henry ran into the street to see a crowd gathering around Charles Burns , who had been shot and was trying to crawl away from Tom Sherman . While holding a large-caliber revolver, Sherman ran after Burns, caught him, then stood over him, saying to the crowd, “I’d better shoot him again, hadn’t I, boys?” Sherman shot Burns in the head, blowing out his brains. Henry wrote in a letter, “All I could learn was Sherman had killed a friend of Burns and thought it would be safer to have him out of the way.” Dodge City would remain a wide-open lawless town. It would not be incorporated until November 5, 1875.

A friend of Bat’s arrived in Dodge from Granada, Colorado, the Santa Fe’s current end of the line.

He told Bat that Raymond Ritter, the contractor who never paid Theodore, Ed, and Bat for grading the railroad bed, was in Granada but would be leaving with three thousand dollars in cash. He was expected to be on the next eastbound train, and that train would be making a stop in Dodge. The news spread through town that the man who stiffed the Masterson boys and Theodore Raymond would be passing through. Everyone wondered what the Mastersons would do.

On Tuesday, April 15, 1873, the eastbound train pulled into town. A crowd gathered, watching Bat as he boarded the train searching the passenger cars. The crowd saw Ritter emerge onto the platform of one of the cars. Bat then walked onto the platform. Bat’s six-shooter was cocked and leveled on Ritter as he demanded the three hundred dollars Ritter owed them. Ritter appealed to the crowd that he was being robbed, but no one came to his defense. Bat told Ritter he was not leaving town alive if he didn’t hand

over what he owed them. Ritter said the money was in his valise inside the car. Bat called to Henry Raymond in the crowd to fetch Ritter’s valise. Bat asked Henry to hand Ritter the valise and then told Ritter to count out three hundred dollars and give it to him. After Ritter complied with Bat’s order, Bat allowed him back into the railroad car with the remainder of his money. The jovial crowd cheered as Bat led them to the Alhambra Saloon, where Ed worked and bought them a round of drinks.

After distributing their share of the money to Ed and Theodore, Bat teamed up with George Mitchell in May and left Dodge on a long buffalo hunt.

Lawmen of the Legendary West won a 2020 bronze nonfiction Will Rogers Medallion. A Western Writers of America member, Bill has written for True West and Wild West and ten books. In 2015, he was sworn in as an honorary Dodge City Marshal.

ORLEY CRAMER HAILED Hank while they were both at work. Hank was already tired of putting up fence, so he hunkered down to talk to his friend.

Orley pulled up a grass stem, then stuck it in his mouth. “I just found out something I’d bet you might like to know.”

“What might that be? We have another mile of this?” He swung an arm sideways.

Orley grinned big. “Shore wish you were right. No, I just heard this from a fella who rode into Wichita from Dodge City. He heard it while drinking beer in the Long Branch.”

“Oh, and anything heard like that must be true.”

“Nah, you need to hear this. You know how you told me you wished you could find your brother, George? Didn’t he work for Clay Allison over in New Mexico?”

“I don’t know that for sure. Someone said so.”

“Well, it seems Wyatt Earp has a running feud with Allison, and the last time they drove cattle through, George was on Front Street shooting

off his gun. Earp and his brother, Morgan, got to shooting back at him, and when he went down, they beat him with their guns. I was told he died right there. Folks said it was mostly ’cause of the feud between Allison and Earp.”

If Orley had hit him in the stomach, he couldn’t have hurt him worse. When he could speak again, he did. “You sure this is true?”

“Ol’ boy swore it was. That the whole place talked about it plenty. I ’member from when we was at Atlanta during the war, you talked about wishing you could find your brother.”

“This George’s name was Hoyt?”

“Oh, yeah, yeah. Didn’t I say it was your brother?”

Hank didn’t finish his job that day but lit out for the bunkhouse, hunted down the boss, and asked for his pay.

“Well, sure. You’ve been a good worker. What’s wrong? You look like you stepped on a rattler.” The boss led him inside and unlocked the safe. “What’s happened, Hank?”

“I’ve got business in Dodge City, and I’d like to

leave out right away.” He didn’t bother to tell his boss that he was going to Dodge to gun down Wyatt Earp. He’d only try to talk him out of it.

In Wichita, he stopped at the bar for some fortifying before his long ride. A foaming glass in front of him, his reflection in the mirror threw back a ratty-looking fence builder. Maybe he’d change clothes before he went to Dodge City. Could he really bring this about? How would he stage the fight? He’d been a crack marksman during the war. But he couldn’t face down a gunfighter like Wyatt Earp carrying a rifle. He wasn’t about to pick him off from a rooftop, either. The point wasn’t only to kill the man but to shame him and his name for what he had done.

So, best if he didn’t get in such a blamed hurry. Earp wasn’t going anywhere, so he downed the beer and hustled to the gunsmith’s where he spent some of his hard-earned pay for a six-gun and the ammunition he needed to do some practicing. He soon learned the big difference between hitting a target with a rifle or with the Colt. But by the time the sun set, he was pulling and hitting fast and proper. Wasn’t so hard, just don’t think but do.

He called a halt, got some sleep, then lit out for Dodge in the morning. Several times along the way, he spotted a good target, dismounted, and shot— fast and accurate. He was ready. Earp would pay for killing his older brother, George.

Late the following day, he arrived at the edge of Dodge City and was hailed by a deputy.

How had they found out what he was up to so fast?

“Hey, mister, just to let you know. This is the south edge of town. Carrying your gun here is fine, but north of the railroad yards, you have to check it. Got that? There’ll be a deputy there to take your weapon should you ride north on Front Street beyond the deadline.”

It was getting near dark when he got there, so he went in search of the Long Branch. Someone there would know where Wyatt Earp might be. All he needed to do was parley with drinkers or gamblers a while. He had the evening and night to prepare.

Not wise to plan a gunfight for after dark. Stu-

pid, in fact. But he could plan real good sitting in the Long Branch with a beer and waiting for the man who would be his target come high noon tomorrow, that being the best time to have a standoff. Then, the sun wouldn’t be in his eyes, and Earp couldn’t claim he cheated by calling him out to face the bright sun hisself.

Orley said cattle drives were slowing down a lot in Dodge and that Earp and his brothers were talking about leaving town. He’d best finish this chore— shooting Wyatt and getting the hell out of Dodge. Bat Masterson was Sheriff here, and Wyatt’s brother Morgan was a deputy. Hank worried the most about them coming after him once Wyatt lay dead on Front Street. He just might need a distraction.

Compared to the bars in Wichita, or the ones he’d been in, the Long Branch was pretty fancy. ’Course it had to be, for everyone knew about the place. Lanterns already burned on either side of the doors. He tied his horse to the rail, gripped

the handle of the Colt to make sure it still rode in its holster, then pushed open the swinging doors to the sound of piano music. Midway and up front of the poker tables, three purty girls swung around kicking their legs, shaking their boobs, and twisting their behinds, in that order. He bellied up to the bar, ordered a beer, then turned where he could watch. Only a foolish man ignored purty girls.

He’d drink his beer, inching around the place like he might be hunting a poker game when all he was really doing was looking for Wyatt and his bunch. Next thing he’d do was plan those distractions he’d need to escape without being shot down or caught and tossed in jail or beat to death like his brother had been.

He took a measure of the fella propped on the bar beside him. “Seen Wyatt Earp?”

The fella grunted. “Talkin’ to me?”

“Yep.” Hank took another sip to keep from letting the man look at his face.

“Usually at his usual table. In the corner, his back to the wall. You know?”

“Yep. So he can see a bullet coming.”

“Yep.”

“Many want to shoot the good lawman?”

“Ever’body nearly. He watches out.”

“Figures, the law being what it is.”

“Figures, the town marshal being who he is.”

“Yep.”

“Met him, have you?”

“Not yet.”

“Want to?”

“Not yet.” Hank palmed his Colt. The fella chuckled. “Can’t say as I blame you. Clay Allison once rode his horse right through the doors and shot some holes in the ceiling. Made an enemy out of Wyatt Earp with that stunt, and they still fight to this day. So, I wouldn’t suggest you pull that fancy looking six-gun and shoot up the bar. Not so good to be an enemy of Wyatt Earp. Hear that growly laugh?”

“That’s him?”

“Yep.” The fella laughed.

“Think it’s funny, mocking me?”

Taking another look at the no-nonsense weapon on Hank’s hip, he nodded and moved away.

Carrying his beer, Hank slipped closer to Earp’s table. Got a look only at the shadowy faces sitting around. He asked to join a nearby poker game one man short and got hisself invited to play with information about the rules and high/low bids. He nodded, with no notion to win, lose, or draw before he found an excuse to leave.

From his chair, he listened until he placed Earp who was pontificating about the latest arrest in town.

“You betting, mister?” A player across from him raised his voice.

He pulled his thoughts back to the game and the cards in his hand. Tapping the table, he sat and went back to studying Earp. The bunch with him wasn’t playing cards. They was discussing something to do with town business.

“It’s getting to where there’s not much going on here. Soon, the cattle will be going around Dodge.

Morgan and I are looking to leaving out soon as that happens. Reckon I’ll stay a few weeks longer. Patrol Front Street to keep the law till we leave.”

A man at Hank’s table leaned forward and spoke quietly. “Won’t be the first time they lit out. What was it last time? Looking for gold or something?”

Laughter circled the table.

All Hank really cared about was if the marshal would be on Front Street the next day. The town marshal, that is. Wouldn’t do to think of him as a U.S. Marshal. Hopefully, that’d never happen. He was Dodge City Town Marshal. Soon as the lawman sprawled in his own blood on Front Street, Hank’s business would be over and done with. Nothing else they were talking about mattered. One ear on Earp, the other on the game, he soon heard what he wanted to hear when Earp bid good night to someone leaving the table. “See you tomorrow right here.” Earp went back to his visit.

Hank lost a pot and excused himself. He’d arrived in town on time to do his duty to brother George. Now, to keep his vow.

“Cain’t stand to lose, huh, mister?” One of the men at his table eyed him with a squint.

“Nope, just remembered I got someone waiting for me.”

“Next time don’t interrupt a game, then.”

The remark touched a nerve, and he glared down at the speaker but decided to let it go. No sense calling attention to himself now. He moved away and back to the bar where he ordered another beer. He’d wait and get a better look at the town marshal when the group filed out... and figure out a distraction to help him get out of town without being spotted.

Inside and upstairs at the Long Branch, Julie shook herself into a low-cut dress, wiggled the split skirt over her behind, and dropped onto the divan to pull on stockings and slip into her shoes.

The door popped open and Mae stuck her head in. “Time to go on, girl. Hustle your buns now.”

Julie played at ignoring her. Thank God this was her last day in this hell hole. She’d come here to get away from something worse. An awful thing she had to forget. Sometimes life turned around and kicked you. All she wanted now was to be rid of this place and mouthy Mae. How could she ever have thought Dodge City would be a good place to hide? It was just another town to run from. Six months and she was ready to shoot the next man who nuzzled her bare skin with his fuzzy beard. There had to be a better life somewhere. Tomorrow she’d escape and never look back. There was enough money stuffed in a drawer to pay for the way outta here. She’d earned it hard.

She peered into the narrow, dark hallway before stepping through the door only to be addressed by her boss.

“Girl, if you don’t get your ass down there—” Mae’s voice sent her skin crawling. Maybe she’d kill that old sow before the night was over.

Fluffing her long hair, she hurried down the steps into the saloon where the piano player hammered the keys, and three of the girls hopped around on the stage acting like dancers. They looked more like fleas in hot ashes. It would be her turn to go on when the last notes were held for their final leap. She would do a better job.

Cupping her breasts so they plumped from the top of the dress, she threaded her way through the crowd of men up front. Used to a bunch of admirers, she hurried onto the walkway following the call of her name. The hurrah of shouts and pounding on tables greeted her. To give those closest a quick peek she leaned forward to spill half her breasts and wiggled her behind to make the men whoop and holler.

A sober handsome man stared at her over the rim of his glass. She gave him an extra twist, and men all around shouted and stomped the floor till the room shook. He only smiled. Determined, she sashayed to the very edge of the stage floor, held

her dress tail above her knees, so he had a real good view, and raised her voice in song. Everyone said she had a beautiful voice, but it was her body they hired her for, so she offered that, as well.

When the good-looking fellow reacted with pleasure to her efforts, she approached him and sat on his knee, ran her fingers through his long shiny hair.

If he came in with the cattle earlier, he’d taken the time to clean up. She appreciated that. His blueeyed gaze moved slow-like over her.

Puckering her lips, she leaned down, kissed his cheek, and wiggled against him one more time before breaking into a new verse. “Oh, Susannah, now don’t you cry for me. I come from Alabama with my banjo on my knee.” Lifting the dress, she gave him a look at one leg.

Mae would stomp her good if she didn’t make all the men happy, so in leaving she dragged a hand across a few laps. The good-looking one’s fingers found the low-cut neck of her dress. He whispered

her name, tilted a glance toward the cribs where girls pleased their men. Nodded. “Later?”

Maybe this night she wouldn’t have to put up with a filthy beard. He even remembered her name. She smiled at him and moved on. When she finished for the evening, he was gone from the table.

Must’ve read him wrong.

A few die hard drinkers remained after the girls each followed a man toward the cribs. The piano player tinkled out a solo, then moved away. Time finally sent most of the customers home. Having caught a glimpse of his distraction, Hank slipped into the dark shadows in the far corner of the silent room. He needed to talk to the girl who’d made so much over him earlier.

A colored man brought out a bucket of water

and mop and scrubbed the floor from under the front windows and door. The bartender rinsed glasses in hot water drawn from the large stove’s reservoir. The girl called Julie moved from the shadows toward Hank and returned the smile he’d given her earlier. Without speaking she took his hand and tilted her head toward the darkness behind them. He went with her. Might as well wait there as anyplace.

Later, he led her to a table in the near-empty saloon. Could he trust this girl? For a silent moment he looked her over.

He’d waited as long as he could. “I need to talk to you.”

Not sure where to begin, he kept gazing at her. She had been nice to him. Looked awfully young for this life. He probably ought to let her be. Search for another idea. But she admitted she was leaving town the next day. That would work well for him. She had a complaint about men and their fuzzy beards, which made him happy he’d had a shave. She must’ve took kindly to that.

Seated, she picked at a fingernail and looked nervous. “What do you want?”

“Where are you going? And why?” He wasn’t sure he wanted to know, wanted to think of her later, after they both were gone from this place. Something about her would stay with him.

She shrugged. “Don’t care, just somewhere away from here.”

“Why don’t you go home?” He reached for her hand. It was fragile and cool in his callused fingers.

“I can’t. Wish I could go get my ma, and we’d go somewhere together. But Pa would kill me if I showed up at their door.”

“Oh, surely not.” Shock went through him.

“Yes. Just like he got mad at my sister, Sue, and dragged her out into the woods, and we never saw her again.” She gripped his hand tighter.

Too dark to see her expression, but he thought she might be crying. He never could say the right things when they cried.

She went on. “Ma got a black eye for asking, and I lit out in the middle of the night. I still feel bad

leaving Ma, but she wouldn’t come with me, and I had to be somewhere else before Pa took it in his mind to drag me into the woods. But I’m thinking it sure weren’t Dodge City.”

“A pretty girl like you shouldn’t travel alone or work in a place like this. No matter where it was. No telling what could happen to you.”

She shrugged again.

“How old are you, Julie?”

“I’m, uh eighteen.”

“I would be glad to take you away from here. Escort you, so to speak.”

“Why should you do that? You already had me.”

“No, I don’t mean that way. The truth is, I need to leave town with someone on my arm. Like we’re a couple. So no one notices me—us.”

Her gaze hardened, and she pulled away. “What have you done? Who is after you? I’m no fool.”

“The truth? No, you aren’t a fool. If I tell you, please promise you won’t say anything. Whether you go with me or not, I need your promise.”

“You’ve been nice to me.” She hesitated and nodded toward the cribs. “I mean, in there you treated me as if you really liked me, and it wasn’t just for a poke and that’s all. I don’t often see men like you.”

Even as he tried not to speak, he spilled the story, and so she let him. “Wyatt Earp murdered my brother, and no one did anything about it. Him and his deputies. But it was him that did it.” His voice broke, and he cupped a hand over his eyes to hide the tears that fell despite his effort to hold back.

She slid tighter against him. Touched the crook of his arm. “Oh, I’m so sorry. But what are you going to do?”

“I’m going to kill the bastard. Oh, I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to—”

“No need.” She leaned into his shoulder and shivered. “It’s nothing I haven’t heard from my pa. That’s why I’m here. He killed my sister.”

Hank kissed her temple. “My God. Did they do anything to him?”

“No, of course not. Just like they did nothing to Wyatt Earp for his killings. Are you wanted?”

He shook his head. “I’ve never killed no one, ex-

cept in the war. Nor have I rode with outlaws. I’m gonna kill Earp, though. But, if I’m careful, no one will know I did it. Tomorrow, I need you to buy tickets for the stage out of here. You may have to go early to miss the crowd, but wait for me in the station, and after I shoot him, I’ll disappear and join you. With my hat on and a jacket over my shirt, I won’t look the same. Just a man and his wife as we board the stage.

“I will do no such thing.” She pulled away and stared into his face. “You shouldn’t kill him. They will never stop hunting you, and they’ll hang you from the nearest tree when they catch you. Besides, no one will ever kill Wyatt Earp. That’s crazy.” She grabbed his arm. “He’ll kill you, that’s certain.”

“He got away with killing my brother. They shot him and beat him to death out in the street.”

For ever so long her gaze remained on his eyes, then she stared out the window of the Long Branch. “Please think very hard about not killing Wyatt Earp. I’m so sorry about your brother. Even if you can draw your gun before he can draw his, and you shoot him, someone will kill you. Because it’s happened before here. I’ve heard some of the men talk about it. George Hoyt worked for Clay Allison at one time. Was he your brother?”

“That’s my brother. And everyone talks about it? But they do nothing. Just let Earp get away with it?”

“He’s the law. Nobody’s going to challenge him.”

“Some say Earp and his deputies shot George down because of the feud between Clay Allison and Wyatt Earp. That way, Earp avoided a gunfight with Allison, who everyone knows is a shootist. Others say that isn’t so and they made it up. It was really something to do with Doc Holliday gonna come into town.” She shrugged and leaned close to him. “You know how tales get to going like wildfire till no one ever knows the truth for sure.”

“I know this. Earp and his law killed my brother. Not only shot him, they beat him over the head after he was down.”

He started to go on, but she put two fingers over his lips. He let them rest there and closed his eyes for a moment. Her touch felt so good. Her skin

smelled like roses. He’d always imagined a woman like her wanting a man like him.

If only things were different. But they weren’t. He owed this to the brother he loved.

Without saying anything, she continued to sit with him. He waited as long as he could, then eased out of her touch.

“It’s okay. You don’t have to do it. I’ll figger out something else to get away with it. I don’t rightly want to be caught.”

“You going to sneak up on him, or what?”

“No. I’m calling him out. I can out-shoot him if I can get him alone in the street.”

Again, her pause, then she blew a strand of hair from her face with a loud noise. “That is about the dumbest thing I’ve ever heard in my life. No way will you outdraw Wyatt Earp, and with the deputies close by like they’re tied together, if you did, they’d shoot you down right quick. You’d never make it to the stage station.”

“I can try. Got to do something. Got no family left.”

“And so you would be a wanted killer, too. Nice way to wipe out an entire family. You have to care about yourself so you can live. What would your ma and pa say if they were alive? Wouldn’t they want you to live?”

“Well, yeah, but they ain’t alive.”

“So what they might feel isn’t worth anything to you? I’d give anything if I could do something to make my ma feel better. It shore wouldn’t be killing my pa, though I’ve wished I could often enough. You said you never hurt no one, so why start now?”

“But I was conscripted into the Confederate Army, and I killed there. George stayed home to look after Pa. When I got back from the war Pa had passed, and George was already gone. And now he’s dead, and I’ll never get to see him again.”

“Well, then. I have an idea.” She rose from the chair. “Let’s the two of us go down to the station this morning and buy us tickets out of here. Neither one of us will have to think of killing anyone. You’re not a killer, I know you aren’t.”

What did he want? What would George want of him? Did it matter to Ma and Pa? Julie was offer-