The Old Synagogue

Welcome and Introduction: Peter Henderson

From Bratislava to Truro 1926-39: Thomas Ort

A family photograph: January 1930 at Napajedla. Jindřich Kapp†, Otto Kapp, Josef Kapp†, Dr Polnauer, Josef Pollak† Fritzi Pollak† (née Kapp), Jetty Ochs†, Vilém Kapp, Johanna Kapp†, Olga Kapp† Paul Pollak, Robert Pollak†, Magda Kapp † “murdered by the Nazis during WWII”

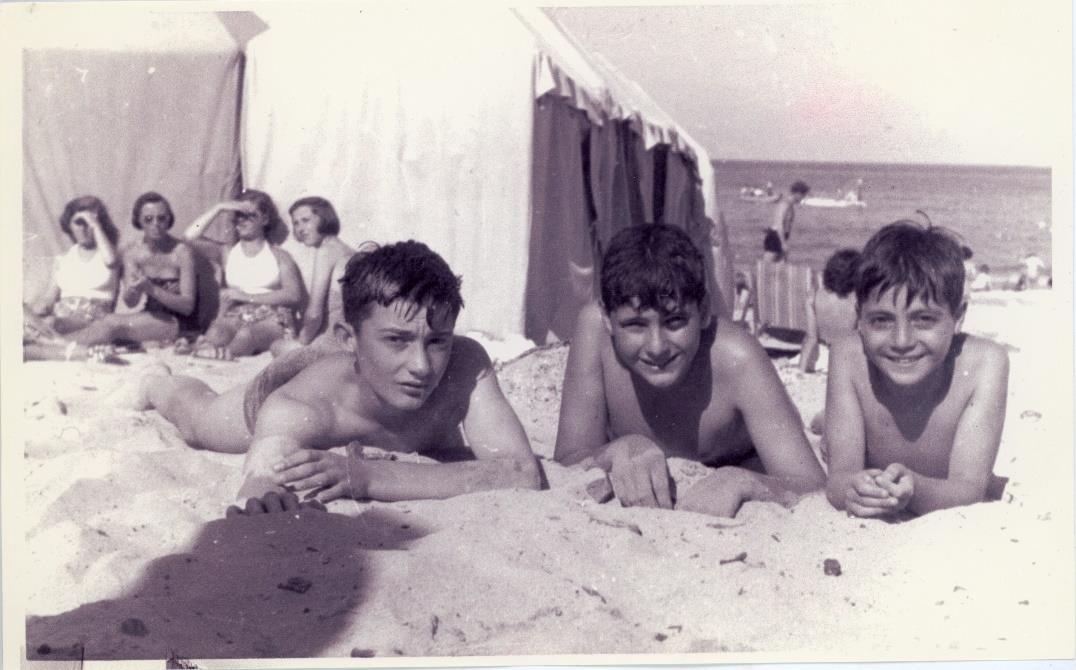

Paul (left) with fellow Czech refugees Peter and Thomas Stross at St Ives in 1940

Paul (left) with fellow Czech refugees Peter and Thomas Stross at St Ives in 1940

Kaddish: Rabbi Professor Dan Cohn-Sherbok

Smetana, Vltava, from Ma Vlast. The riverVltava runs through Prague. Patrick Williams (flute), Will Bersey (piano)

Kaddish: Rabbi Professor Dan Cohn-Sherbok

Smetana, Vltava, from Ma Vlast. The riverVltava runs through Prague. Patrick Williams (flute), Will Bersey (piano)

School, University and National Service: 1939-50: Edward Peters

Meister Omers house photograph 1944 Paul is seated next to Marjorie Harris and housemaster ‘JB’ Harris

Paul’s military identity certificate

Paul wrote to Canon Shirley on 28 March 1950

Meister Omers house photograph 1944 Paul is seated next to Marjorie Harris and housemaster ‘JB’ Harris

Paul’s military identity certificate

Paul wrote to Canon Shirley on 28 March 1950

Master and Housemaster 1950-88: some reminiscences read by Jonathan Barnard

Marlowe 1959: the first house photo, in front of Prior Sellingegate – his own quarters

Marlowe 1976: the last house photo, behind the house with summer dress and girls.

Master and Housemaster 1950-88: some reminiscences read by Jonathan Barnard

Marlowe 1959: the first house photo, in front of Prior Sellingegate – his own quarters

Marlowe 1976: the last house photo, behind the house with summer dress and girls.

Second Master 1976-88: The Revd Canon DrAnthony Phillips, Headmaster 1986-96

PP and PP: Headmaster Peter Pilkington and Second Master Paul Pollak 1986

Headmaster Anthony Phillips and the Second Master 1988

Second Master 1976-88: The Revd Canon DrAnthony Phillips, Headmaster 1986-96

PP and PP: Headmaster Peter Pilkington and Second Master Paul Pollak 1986

Headmaster Anthony Phillips and the Second Master 1988

Mathematics

The first paper in which Paul collaborated with Roger. Toby Brown, a King’s Scholar in Marlowe, also helped. It was published in the Journal of Computational Chemistry in 1991.

and Memories: Roger Mallion

Doing the sums: Roger and Paul at the swimming pool 1988

and Memories: Roger Mallion

Doing the sums: Roger and Paul at the swimming pool 1988

Archivist and Assistant Archivist 1972-2023 andAntique Escapades: Peter Henderson

Paul and Patrick Leigh Fermor at the opening of the new Grange at St Augustine’s in 2007. Paul of course had created the inscription (in Latin) on the plaque. The two shared an interest in languages and in the highways and byways of Central Europe.

Vale PPMCMXXVI-MMXXIII

Psalm 133: Ecce quam bonum et quam iucundum habitare fratres in unum!

Behold, how good and how pleasant it is for brethren to dwell together in unity!

You are invited to lunch in the Pupils’Social Centre under the Shirley Hall.

The pleasures of retirement: Ardingly Antiques Fair 1990.Welcome and Introduction: Peter Henderson

Hello and welcome to this special occasion to celebrate the life of a very remarkable man.

Back in 1995, Paul asked Roger Mallion and myself to be his executors. He then wrote us a letter with his instructions. This ended:

“I hope this isn’t an unpleasant surprise: I really don’t think too much should be involved, especially as you have full freedom to seek and pay for advice. Nor will I be interfering.”

Now Paul didn’t want a funeral; he didn’t want a memorial service; and he didn’t want a fuss.

So what we have come up with today is a sketch of Paul’s life. You can fill in more of the details over lunch.

And in the Pupils’Social Centre there will be a selection of reminiscences and photographs to jog your memories.

We chose the Synagogue as the venue for the Celebration for many reasons – but above all in order to acknowledge and respect Paul’s family background.

That is where we start. And we are hugely grateful to Thomas Ort for coming from New York to speak to us today.

Paul’s birth certificate

Paul Pollak: ATribute: Thomas Ort

Paul Pollak: ATribute: Thomas Ort

Thank you, Peter and Susan, for inviting me to this celebration of Paul Pollak’s life and for allowing me to say a few words about his family history. Let me begin by introducing myself and explaining my relationship to Paul. I am Paul’s first cousin once removed. Paul and my mother – Alena – were first cousins on his mother’s side, so not the Pollak side. I first met Paul in 1987 when I was 18 years old. It was the summer after my first year in university and, like so manyAmerican students, I came to Europe to have a good time – and maybe also to learn something. I was enrolled in a writing program in London.

My mother, naturally, insisted that I look up Paul, and I did so dutifully, though not without some apprehension. Who was this mysterious cousin of hers, a mathematician who resided in Canterbury and taught at The King’s School?Although my mother spoke about Paul regularly, she knew him mainly through their correspondence; she was just a child when she last saw him in 1939. Still, whatever my apprehension, I was eager to meet this cousin because I was always keenly aware of the absence of relatives on my mother’s side of the family. She was an only child who immigrated to the United States from Czechoslovakia in the 1960s, leaving both her parents behind in Prague. Besides them, she had a cousin, Magda, who lived in Israel. And then she had Paul in England. That was it.

My encounter with Paul that summer was very meaningful to me and not only because he was a scarce blood relative. Rather, what I experienced in that meeting was recognition. I saw in Paul much of my grandfather Otto, Paul’s uncle; I saw in him aspects of my mother’s character; and I saw in him something of myself too. It wasn’t just about physical appearance, though that was certainly a part of it. It had more to do with his whole bearing as a person, the way he told stories, made jokes, expressed approval and disapproval, and so much more. Everything about him was strangely familiar. He was, on the one hand, completely unknown to me and yet absolutely recognizable as a member of my mother’s family. I got on with him very well. Since our first meeting in 1987, I remained regularly, if intermittently, in touch with Paul for the next 35 years. I visited him here in Canterbury on about ten different occasions and, after my mother passed away in 2001, we corresponded on a consistent basis.

Paul was born in 1926 in Bratislava, which was then the second city of Czechoslovakia and is today, of course, the capital of Slovakia. He grew up, however, mainly in Prague; I don’t know when exactly his parents moved there. Paul’s mother Fritzi, or Bedřiška in Czech, came from a tight-knit family of Czech and German-speaking Jews, the Kapps, that hailed from a small Moravian town called Napajedla, not far from the border with Slovakia. Fritzi was the third of six children and the only girl. Two of her younger brothers died in childhood, so she really grew up with three siblings: Josef, the eldest; next, Otto, my grandfather; and then Heinrich (or Jindřich in Czech), the youngest. From my understanding, Fritzi was the golden child of the family. She was smart and funny and kind and beautiful. Everyone loved her. Paul too adored his mother and was very attached to her; his separation from her was extraordinarily painful. Fritzi’s husband, Josef Pollak, was born in the town of Iglau, or Jihlava in Czech, but he really grew up in Vienna. Unlike the Kapp siblings, who came from a mixed area of Czechs, Germans, and Jews, and who were completely bilingual in Czech

and German, the Pollak family spoke mainly German. I mention all this because you may not know that Paul grew up speaking both Czech and German. He communicated with his mother mainly in Czech but primarily in German with his father.

From what Paul told me, his childhood in Prague was quite idyllic. His father was a successful businessman, and the family lived in a prosperous, middle-class neighborhood of the city. He went to a prestigious English-language school and travelled regularly to Napajedla and Vienna for holidays with the Kapps and Pollaks. Czechoslovakia, furthermore, was just about as stable, democratic, and economically successful a state as it comes in Eastern Europe, so the late 1920s and early 1930s were a happy time. But things, of course, went downhill precipitously in 1933 when Hitler came to power. By 1938, the situation for Jews in Germany and Austria had become untenable, and with Czechoslovakia squarely in Hitler’s sights, that state was hardly a safe haven either. Everyone who could sought to leave, but visas were in notoriously short supply.

One of the few sources of hope was the Kindertransport program that started in Germany and Austria in the aftermath of the Kristallnacht pogrom. As you may know, in response to that appalling and murderous upheaval, the British government relaxed its visa restrictions for Jewish children seeking to flee Hitler’s clutches. In December of 1938, it began admitting to England the first of what would eventually be about 10,000 Jewish refugee children 17 and under. In March of 1939, the program was extended to Czechoslovakia. That is how Paul got to England. He left Prague on a transport in June 1939, soon after his thirteenth birthday. Sadly, Paul’s older brother Robert became ineligible for the program just as it was getting under way; he turned 18 in March 1939. All told, just 664 Jewish children were rescued from Czechoslovakia by way of the Kindertransports. But Paul was one of those.

Once in England, Paul was able to correspond more or less regularly with his parents until the fall of 1940. After that, he lost direct contact with them and received only occasional news from others who were able to get messages out by way of the Red Cross. It was only after the war, in the summer of 1945, that Paul learned what happened to his family. In January of 1942, his mother, father, and brother were deported to Terezín (Theresienstadt in German), the main Jewish ghetto in the Czech lands. Most of the Kapp family was sent there too in the following months. Paul’s grandmother, Johanna Kappová, died at Terezín in February 1943. All things considered, this was a merciful fate.

The real horrors for the Pollaks and the Kapps began in the fall of 1944. In September of that year, Paul’s brother Robert was deported to Auschwitz and never heard from again. Three weeks later, Paul’s parents were transported to Auschwitz and never heard from again. The same fate awaited his uncles Josef and Heinrich Kapp. The only one to survive the hideous cauldron of the camps was Paul’s cousin Magda. She too was deported to Auschwitz in October 1944 but somehow managed to endure it as well as multiple other camps through which she passed. In 1948, Magda immigrated to Israel and still lives there today. One of the few other relatives of Paul to have survived the Holocaust was his cousin Susi Pollak, who escaped to Palestine in the summer of 1939 just before the outbreak of the war. She later emigrated to SouthAfrica and then eventually to the UK, where she died in 1993.

The only family unit to survive the war intact was that of my grandfather Otto, Paul’s uncle. Otto survived the war because he was married to a Czech Catholic woman and that mixed marriage protected him and his daughter Alena – my mother – from deportation until very late in the war. It was from Otto that Paul learned of the fate of his family. It may be interesting to know that Otto urged and indeed expected Paul to return immediately to Czechoslovakia after the war. Magda, for her part, encouraged him to immigrate to Israel. Paul, obviously, did neither of those things, choosing to remain in England instead.

Let me conclude my remarks with a couple of observations. First, as you likely know, it was very difficult, if not impossible, to get Paul to talk about any of what I’ve just related to you. Perhaps much of it is unknown to you. But over the course of my visits to Canterbury, Paul did reveal more, and on one occasion he shared something that was particularly wrenching. He told me he wished he had never been put on the Kindertransport and that he would have preferred to have died with his family. This may sound shocking, not least because it suggests a repudiation of the life he created for himself here, but I think it would be wrong to interpret it that way. Rather, I believe his remark was an indication of the measure of the pain that Paul carried with him for the rest of his life. I ought not psychologize him, but it seems clear to me that he suffered profoundly from the guilt of the survivor. He was never able to make peace with the fact that he survived the war and his beloved family did not.

Second, it seems to me that people in Paul’s position – orphans of history, but maybe orphans in general

will seek to create new “homes” for themselves in any way they can. Sometimes they do so by hurling themselves into ideological causes or by binding themselves to ordergiving institutions because these provide them with the sense of meaning, community, and identity that their absent families cannot. Magda, for example, became a fervent Zionist in the postwar years. Some orphans gravitate to institutions like the military because their structure and hierarchy provide them with the fellowship and security they crave. These, however, were not Paul’s homes, so what were they?

One, I would argue, was England. Paul was immensely grateful for everything that England had done for him, and he identified powerfully with it. He thoroughly adopted English manners and customs, so much so that he was often mistaken for a native son. Only his name betrayed him. And, as you surely know, he hated to travel, insisting that he had everything he needed right here. I don’t believe he left England since the late 1940s or early 1950s.

But Paul’s most important home by far was the institution to which he committed himself, the place that gave him career, community, security, and purpose. That institution was of course The King’s School. After his family was torn apart by the war and his few remaining relations scattered across the globe, it was The King’s School and its community that became his true home.

Thank you for giving that to him.

The Kaddish is an ancient prayer inAramaic. It is the Mourners Prayer, and is recited for all Jews at their death. So today it is recited for Paul and for all members of his family who died during the Holocaust.

Kaddish: Rabbi Professor Dan Cohn-Sherbok

Kaddish: Rabbi Professor Dan Cohn-Sherbok

Smetana, Vltava, from Ma Vlast.

The riverVltava runs through Prague.

Patrick Williams (flute), Will Bersey (piano)

Patrick Williams (flute), Will Bersey (piano)

School, University and National Service: 1939-50: Edward Peters

I joined Mitchinson’s House in 1987.

Paul Pollak was already a revered figure in our family, due to his knowledge of the history of Canterbury and the School. In particular, for us, was his knowledge of the 17th and 18th century links of the de la Pierre, alias Peters, family to the Blackfriars and the School. It was PP’s initiative to name the dwelling at the southern end of the Refectory ‘De La Pierre House’.

I was the last boy to join PP’s tutor group, the year before he retired from teaching (at our special request, after new entries had officially closed).

Whereas other tutor groups discussed academic progress or current affairs, we had the pleasure of discussing (in PP’s marvellous room in Lardergate in which he displayed, beautifully, some of his splendid collection of rugs, furniture, art and antique objects, including some fine Buddhas, which made a big impression on me as a boy) the week’s ‘Mystery Object’, procured from antique shop or auction house.

Following Mr Pollak’s retirement, one of the greatest joys of my time at King’s was, for Thursday afternoon ‘Activities’, working with him asArchivist in the SchoolArchives together with another boy, Alex Driskill-Smith – the SchoolArchives were at that time crammed into in a small windowless room under the Shirley Hall – and getting the benefit of his wonderfully interesting and wryly amusing conversation.

It is therefore a great privilege to be asked to read some extracts from Paul Pollak’s own personal archive, from the period 1939 to 1950, carefully chosen and linked by Peter Henderson, PP’s successor as SchoolArchivist.

After Paul came to England, he lived at the Baldhu Rectory near Truro and initially went to Truro Cathedral School. In 1941 he joined the King’s School at Carlyon Bay.

Norman Coley was the priest in charge of the Winchester College Mission, Portsmouth. He got to know Paul soon after he arrived in Baldhu. Paul kept many of his letters and they provide the occasional glimpse of what the schoolboy was up to.

25 August 1941: I hope the King’s School will give you all that you expect. And that you too will be able to give something to the King’s School.

8 September 1941: I wished to congratulate you on the School Certificate results. Please tell me details when you write. What does ‘six distinctions, two credits’really mean?

30 October 1941: Your letter was largely incomprehensible, was much enjoyed but had to be read six times before I could begin to understand what you were talking about.

27 November 1942: Do you still play Rugger? Or have you retired from so strenuous a game with your advancing years?

And in the days of corporal punishment:

15 December 1942: At the thought of you being beaten, my heart says ‘Poor Paul’, while my head says ‘silly blighter’… I am secretly a little pleased that you can still play the fool, though I should not – if I may adventure to advise you

break windows and tear doors from their hinges with monotonous regularity.

In November 1944 Paul applied for a Scholarship at Oxford University. His reference came from JB Harris:

Paul Pollak has been a pupil of this School since September 1941 and is now a Senior King’s Scholar, a School Monitor, Head of his House and Vice-Captain of School. He is a studious and industrious boy, who has twice passed the Higher Certificate with Distinctions in Physics and Chemistry, and I consider him to be, in every way, a suitable candidate for a University Scholarship.

Paul duly won a demyship (the Magdalen name for a scholarship) and he joined the College in January 1945. There is little direct evidence of his time there, but the Oxford Letter in the December 1945 Cantuarian did observe:

P. Pollak and GAGordon (Christ Church) were encountered at coffee in Elliston’s wrangling over problems of higher mathematics.

In February 1947 he became a naturalized British subject and hence was eligible for National Service. After graduating in the summer, he did his Officers’ course at the School of Military Survey and then joined the Middle East Land Forces in Egypt. His commanding officer later wrote a reference, from which the following extracts are taken:

He ran his section well and carried out the routine work efficiently. His men were happy under his command and worked well for him.

Mr Pollak has a very good mathematical education and an alert brain, which enabled him to apply, without difficulty, his knowledge to fresh problems, of which several cropped up while he was with me.

This reference does not record that it was at this time that Paul learned the virtues of Egyptian PT. For those unfamiliar with army slang it means having a nap. Paul was an expert.

On leaving the Army, what was he to do next? Paul kept his draft of a letter dated March 1950 to Charles Singer, the distinguished historian of science who had taught and befriended him in Carlyon Bay. He was asking for advice about his future and considering the alternatives of the Liberal Jewish ministry or teaching. One thing however was clear:

“That one should have some sense of vocation before entering any work seems to me desirable.”

He concluded: “I have today had an offer from Dr Shirley to come to the King’s School. I go to Canterbury to discuss it on Saturday.”

Six days later he wrote to Canon Shirley: “I like the idea of teaching at King’s very much: the place, atmosphere, and those members of the staff whom I met are all attractive.”

And after some discussions on what he might teach, he accepted the job. He then did a term at Wolverhampton Grammar School – “I shall make my mistakes a good way from Canterbury”.

And so in September 1950 Paul re-joined the King’s School. He never left.

Paul’s letter to Canon Shirley 28 March 1950

Master and Housemaster 1950-88: some reminiscences read by Jonathan Barnard

Ladies, gentlemen, good morning. Some of you may remember me, but for those who have forgotten or never knew, I am Jonathan Barnard and I joined Marlowe in those now distant days of 1970.

The School has been sent dozens of tributes to and reminiscences of Paul and I have been given the honour of reading out a small selection of these, covering Paul’s years as master and housemaster from 1950 to 1988. These all come from people who are not present today.

But I shall begin with two very brief anecdotes of my own showing Paul’s wit and perceptiveness.

Paul was, as we know, of Jewish origin. But coming to England he spent the greater part of his life at a Christian school. Acouple of years ago I bumped into him and asked what he was up to. He told me that he had just returned from Canterbury’s only mosque where he had given them a very fine copy of the Koran. “At my age”, he explained, “I think it wise to keep all the bases covered.”

My daughter, Saskia, knew ‘Uncle Paul’ from birth. My wife and I are both of South American origin and Saskia has big, brown latino eyes. When she was about 8 years old, Paul looked at her, then turned to me and said “Saskia has the sort of eyes that one day will either get her into or out of a lot of trouble.” He was, of course, right on both counts.

But back to the job in hand...

Christopher Matthew (School House 1952-57)

Mr Pollak was very lucky not to have taught me Maths, but I do remember that I once learned something very useful from him about mushroom hunting. One day, sitting at the head of a table during lunch, he expounded on the pleasures and perils of one of his favourite pastimes. Aboy asked him what would happen if by chance he ate a poisonous one. Mr Pollak thought for a moment, twitched his moustache, and replied, ‘Collapse. Coma. Death.’

Now, pay attention, you have to concentrate on this one...

David Brée (School House 1953-58)

At the beginning of my first class on dynamics, Mr Pollak asked us: “Arolled up carpet is placed at the top of the stairs and allowed to unroll down the stairs. Make simplifying assumptions to say how fast the end of the carpet will hit the ground.” The clue is in making the simplifying assumptions. And the answer is the same speed as the end of a flicked tie, which is greater than the speed of sound (one hears the end breaking the sound barrier with a bang, and anyone on the receiving end of the flicked tie gets a hurtful twang, as we all knew of course). What an inspiring way to teach mathematics.

PS I acknowledge Mr Pollak in my book “Most-perfect Pandiagonal Magic Squares”.

Now, I did an internet search to find out exactly what Pandiagonal Magic Squares are, but having read the answer, I remain none the wiser...

Nicholas de Jong (Walpole 1957-62)

On a very hot Army Corps Field Day in the Summer of ’61, the platoon to which I was attached as wireless operator was ordered to probe the ‘enemy’s’forward positions. By lunchtime, having failed to make contact physically, or over the air waves, with anybody, interest was in serious decline. Aspot of lunch might raise morale, but as we settled down ‘Percy’arose, furious, from a gorse bush. “GET OUT OF MYAMBUSH!”, he screamed at us. An order quickly obeyed. Not only was it mission accomplished, it provided a moment that has amused for over sixty years. Thank you, Paul.

Chris Cantor (Marlowe 1967-71)

Paul taught me that even a very minor wrong is a wrong.

Jane Pearce (née Baron) (Marlowe 1971-73)

Thank you so much for sending me the news about Paul Pollak. I was very saddened to read it.

He was a delightful person and a marvellous housemaster. He coped so well with having the ‘first girl’foisted on him in September 1971. When my parents and I came for a chat and interview with the Headmaster, Canon Newell, in the Autumn of 1970, one of the questions my parents asked was which house would I be attached to or would I be “floating about”. Canon Newell immediately said, “Marlowe”. No prior consultation with Paul it would appear!

As the first and only girl for a year, I only met kindness and understanding from Paul. He was very perceptive and seemed to know instinctively how to deal with situations and pupils of that age. His judgement was always excellent. I knew I could trust his advice implicitly and that I would be wise to follow it.

I feel very lucky and privileged to have had Paul as a housemaster, and together with Stephen Woodley as tutor was so well served at King’s.

Just a final thought – a strange coincidence, but Paul died on my birthday, Sunday, 14th May. I will always remember him.

As, indeed, shall we all.

And this final reminiscence comes from

Charles Neame (Marlowe 1971-75)Paul Pollak’s strategy for taking over our Maths class on a day when Richard Paynter was indisposed was to show us how to calculate logarithms without log tables. At least, I think that’s what he was doing for 40 minutes, as he filled and erased the blackboard three or four times over, accompanied by an extraordinary maths commentary which held his 14-year-old students spellbound until the bell rang. Nothing to do with the relevant stage of our curriculum, but revealing his uncanny knack for knowing what would intrigue young minds at a loose end. Why else would I remember this incident for over 50 years?

I was not a particularly good student; or would not have been, had not Paul always listened and spoken to me as if I were. After King’s we kept in touch. He was held in great affection by my whole family (even though I was the only one of us he had taught) and for many years was a most welcome visitor at important family events.

I suspect there have been, and are, hundreds more of us over the years, now scattered around the world, who remember feeling better, stronger, more capable, because Paul Pollak listened to us and cared.

Those last words sum up the man so well and I know that we shall carry with us for all our days fond memories of this great man.

The person delivering this part of our Commemoration should of course be Peter Pilkington with whom Paul worked in tandem for ten important and very successful years. As a Jew, Paul could not be appointed Lower Master, so Peter who wanted him as his Deputy invented the post of Second Master and made him his second in command save for matters concerning the Cathedral and the scholars. Together they reestablished King’s as one of the great schools. Paul was also immensely fond of the Pilkington family and virtually wrote the section about Peter and Helen in Imps of Promise.

However, the two years that I worked with Paul as Second Master should not be underestimated. I had two advantages. We both shared a Cornish childhood having lived only a few miles apart. Who else here knows where Baldhu is? We also had a deep love of the Hebrew scriptures, whose study has been my life’s work.

It was Paul who literally enabled me to survive my unbelievably difficult first year and, as one of you wrote, take off my L plates at its end. As someone who was the product of the most hideous trauma imaginable which resulted in his loss of everybody and everything we naturally hold dear, for Paul subsequent difficulties, though never trivialised, paled into insignificance. It was proportion that Paul taught me and always accompanied by laughter –the most valuable of gifts. There was no problem that with patience could not be solved and solve them we did. Indeed, Paul enjoyed the detective work which was part of the Second Master ‘s duties. At times, clothed in hat and mac and with his moustache, he reminded me of one of those fictional continental sleuths seen on television.

Second Master 1976-88: The Revd Canon DrAnthony Phillips, Headmaster 1986-96

Peter Pilkington, Sarah Pilkington and Paul at Celia Pilkington’s wedding 2005

Second Master 1976-88: The Revd Canon DrAnthony Phillips, Headmaster 1986-96

Peter Pilkington, Sarah Pilkington and Paul at Celia Pilkington’s wedding 2005

When I arrived at King’s Paul was already past what was then retirement age. Radical change was on the way. In my fourth term, the Governors gave me the signal to move towards full co-education both at Sturry and Canterbury. Clearly a new management team to include a senior woman member of staff would be needed. So, I had the difficult task of suggesting to Paul that it was time for him to retire as Second Master. He could not have been more gracious, even suggesting who his successor might be. I was able to tell him I had come to the same conclusion.

But his value to me continued in a myriad of ways. For example, at his suggestion, Vicky and I entertained a succession of ladies and at his instigation I wrote countless letters to OKS to congratulate them on their successes. It was through contacts like these that the school benefited.

As Archivist he would from time to time seek my help. When on sabbatical, Vicky and I stayed on St. Helena where an OKS had been Chaplain at the time of Napoleon’s imprisonment, he asked me to find out what I could about him. There were in fact few records, but we were able to bring back a photo of the Chaplain’s wife to Paul’s delight.

Even in my retirement Paul would ask me to elucidate some theological matter. Indeed, only recently he sent me a card headed ‘Tidying up’– surely a euphemism. He wanted me to identify some writing on an icon of St. Mark which he had bought years ago in Venice. I was able to consult an Oxford theologian and tell Paul that the language was Coptic and what it meant.

On our last visit to Canterbury, Vicky and I called on Paul and sat among the confusion of buddhas, books, carpets and pictures that struggled to find a place in his front room. As we left, he extolled the beauty of a weed growing outside his front door. In a way that sums up the generosity of this unique man whom I had the privilege to call my friend.

Mathematics and Memories: Roger Mallion

Good afternoon, ladies & gentlemen. My brief is to reminisce about Paul and Mathematics. To teach Mathematics under his former Housemaster J B Harris was, after all, the principal reason for Paul’s return to King’s (though, this time, in Canterbury rather than Cornwall). This was in 1950, after Oxford and National Service.

Paul once told me that he learned most of his Mathematics at King’s through actually teaching it. In that regard, he agreed with the eminent 20th century quantum chemist Peter Atkins who once said that ‘Teaching forces you to explain what previously you thought you had understood.’ Paul expressly stated that he gained little from Magdalen College, Oxford where he recalled to me that some tutorials were spent reading the proofs of the tutor’s latest book. Paul also used to recount a tale about a lecture course from a world expert in his field; but Paul said that ‘. . .he didn’t pass much of his knowledge on’. This was because the course was delivered in an L-shaped room in Balliol: but the lecturer and his blackboard were in the shorter arm of the ‘L’and the undergraduates were all in the longer part, at right angles to it!

Paul’s formidable intellect could be a bit intimidating to all but the stronger pupils in Mathematics. Paul of course knew this and it was well summed up when, one day, I asked Paul if he were ever going to write a Mathematics textbook. He said: ‘no no, I’m never going to write a book on Mathematics; but if I ever did do it I have the perfect title, already decided. It’s to be called Mathematics Made Difficult.’

He never did write that book but, in the 25-year period between 1991 and 2016, he did publish 10 papers with me - in the so-called learned journals of the Mathematical Chemistry literature. This was largely because, unlike with most mathematical specialists, his mind was completely open to my explaining a new problem that needed to be solved. Once he understood the problem and its context, he proceeded to solve it (and usually extremely elegantly). One of my ‘star’VIb ‘double’mathematicians, Toby Brown, KS, featured as a coauthor once or twice because (a) our collaboration used the mathematics of matrices that I was currently teaching him, and (b) he possessed a small personal computer in the days when very few others did. So, in the authorship by-line of these papers, the age range was from 18 to 65!

Paul stood down from being Head of Mathematics in 1987, a year ahead of his actual retirement from teaching Mathematics. This was mainly because of the imminent introduction of the dreaded coursework projects, alongside traditional timed examinations for GCSE assessment. I took over as Head of Department and I still have the grey (now white) hair to prove it. Paul’s constant refrain during this final year, as coursework projects were increasingly introduced, was: ‘The present system’ll see me out!’

For a man who was in his nineties Paul had a wonderfully ‘gallows’humour when it came to mortality, especially his own mortality. Paul told me that a boy once said to him: ‘Sir, what’s the point of Mathematics?’To which Paul’s reply (no doubt twirling the moustache and sniffing the air) was: ‘Mathematics is a very agreeable way to pass the time until death’.

Paul did indeed well live up to this maxim. Now, though, all the Mathematics that he knew has

sadly - suddenly slipped away.

It was a huge privilege to have had Paul as a colleague, departmental boss, mathematical collaborator, friend, mentor and confidant for 47 years. Like the late Peter, Lord Pilkington, in his Cantuarian Valete to Paul, I never made any important decision during that time without first discussing it with Paul Pollak.

MAY HE REST IN PEACE

Drawing by Ishbel Myerscough

Drawing by Ishbel Myerscough