4 minute read

History

The lying game

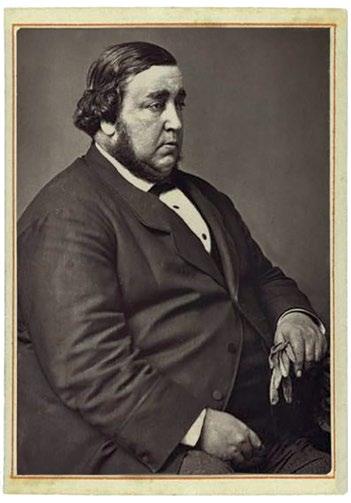

An enormous conman starred in two of the longest trials in history david horspool

Advertisement

Now that we’re all being asked to prove our identity every time we go out to lunch, the idea of being an impostor seems quite attractive.

But could we go as far as Anna Sorokin, the lorry driver’s daughter from a Moscow suburb who passed herself off as a $60-million trust-fund heiress on arrival in New York City in 2013?

She managed to convince people she was who she said she was… And, darling, I seem to have forgotten my credit card – would you mind paying the hotel bill?

Sorokin was part of a rich tradition of impostors. Because of her national origins, she reminded people of ‘Anastasia’ – the woman who for years claimed to be a missing Romanov princess, who had somehow survived the murderous cull of Yekaterinburg.

But when I read about Sorokin, I thought of another impostor who travelled to the other side of the world to fool the upper crust, that great Victorian cause célèbre the Tichborne Claimant.

In 1866, a ship docked at London carrying a passenger named Tomas Castro. Castro was the name adopted by a man who was in reality either Sir Roger Tichborne, long-lost scion of the Tichborne family and heir to their extensive estates in Hampshire; or Arthur Orton, a butcher from Wagga Wagga who had first emigrated to Australia from Wapping, London, via South America in the 1840s.

Did Castro and Tichborne, even allowing for the passage of time (Roger had disappeared in 1854), bear a strong resemblance? Not really. When last seen, before his ship went down between Rio and Kingston, Jamaica, Roger had been a slim, dissipated young man of conventional English upper-class upbringing and education, who had been a fluent Frenchspeaker. The Claimant weighed 27 stone, spoke no French and did not seem to know much about Roger’s past or his family.

It is difficult to believe that the case

Not titchy: the Tichborne Claimant

would have lasted more than a week had the Dowager Lady Tichborne, in Paris, not confirmed the Claimant as her son when he arrived there in 1867. Lady Tichborne had, after her husband’s death, advertised throughout the empire asking for information leading to her son – who she was convinced was still alive. Her confirmation of the Claimant’s identity, and her subsequent death before the identification could be tested, contributed to the survival of the claim.

The Claimant’s case led to two of the longest trials in English legal history. The civil case began in 1871. It lasted for ten months, heard the testimony of 350 witnesses – and resulted in the dismissal of the claim, and the revelation of the Claimant’s likely identity as Arthur Orton.

Then came the criminal case, during which Castro/Orton/Tichborne was charged with perjury. He lost that one, too, in an even longer trial, lasting 11 months. His unconventional defending QC, Irishman Edward Kenealy, did more than anyone to promote and draw out the trial. He also managed to insult the judge so comprehensively that he was disbarred. The Claimant, meanwhile, was sentenced to a savage 14 years’ imprisonment.

The case had some old historical echoes. At the end of the Wars of the Roses, two ostensibly royal impostors emerged, Perkin Warbeck and Lambert Simnel. Their fates set some of the conventions that the Claimant followed 400 years later. They claimed a crown rather than a decent country estate. Warbeck claimed to be the Duke of York, the younger of the ‘Princes in the Tower’, who, according to Warbeck’s claim, survived his uncle’s murderous orders.

For Warbeck, as for Tichborne, the evidence of a ‘foolish, fond’ old lady was vital. In Warbeck’s case, it was his putative paternal aunt, Margaret of Burgundy, who confirmed his identity as the Duke of York.

The Claimant’s fate was less grim than Warbeck’s (eventually hanged by Henry VII). When the Claimant was released after ten years’ exemplary behaviour, his brief had kept his claim in the public eye. Kenealy had yoked the case of a man who wished to be an aristocrat to the campaign for parliamentary reform, repurposing it as a tale of the little man (not that little) traduced by the Establishment. In the long run, none of it did him any good, and the Claimant died in penury in London in 1898.

The only relict of this peculiarly Victorian curio is in our language. The comedian Harry Relph (1867-1928) was known as Little Tich not because he stood only four-foot-six tall but because, as a child, he had borne a resemblance to the chubby Claimant. His fame led to the re-spelled word ‘titch’ being adopted in the vernacular to mean a short person.

If you’ve ever called someone titchy, you are keeping alive the story of a man who in his day was known for vastness – in body size, length of legal battle and scale of the whoppers he told.