Early Season Management

Amanda Huber Editor

Numbers tell a story but maybe not the whole story. In July and August 2024, Auburn University’s Department of Agricultural Economics & Rural Sociology held 11 focus groups in Alabama with 115 farmers, agribusiness owners, employees, processors, manufacturers and agricultural lenders. Mykel Taylor, interim department head, and Kelli Russell, assistant Extension professor, led the e ort to gather rsthand perspectives on agriculture and economic development in words and not just numbers.

What they heard was an “earful” about pro tability overall. e sentiment echoed across the group is, “If it’s not worth doing, why are you going to spend the resources and all your energy just to be at a breakeven point or barely pay the bills?”

e most common factors a ecting profitability are as follows:

■ Rising input costs and decreasing commodity prices. e inverted relationship between these and the impact on profitability is a critical stressor for farmers.

■ Equipment costs are skyrocketing with in ation. e high cost of speci c, necessary equipment limits farmers from diversifying as their equipment purchases tie them to particular commodities.

■ Increasing transportation costs and freight charges. e escalation in costs related to shipping commodities compounds the negative impact on pro tability.

■ Rising farmland values and rental rates. Expenses related to land are a concern now for pro tability, and it is expected to be more so in the future.

■ Labor availability and costs. Regardless of commodity, all producers stated that labor issues directly impact pro tability.

e authors say this documentation is a good rst step in informing decision makers of what is unique about agriculture and how those in the industry perceive the likelihood of continuing their operations with the next generation of producers.

Producers can track their price risk protection through revenue insurance in a given growing season by comparing the harvest price (fall) to the projected price (spring) determined by the U.S. Department of Agriculture Risk Management Agency. In the broader marketing plan, revenue crop insurance provides a form of price guarantee at a premium expense similar to locking in a price guarantee using a put option contract. A previous article examined the price protection o ered by Revenue Protection, Supplemental Coverage Option and Enhanced Coverage Option crop insurance for corn and rice (Biram, 2023). at article considered the change in price and not the potential change in yield. is article builds on that by considering price and yield protection o ered by ECO and providing a snapshot of how changes in county yields can also trigger indemnities. ECO is an area-based crop insurance product and must be paired with farm-level insurance like Yield Protection or RP. e liability insured by ECO is calculated using the same parameters as RP (e.g., actual production history farm yield and futures prices) at coverage levels of 90% and 95%. e futures price is based on the higher of the projected price and the harvest price determined by USDA-RMA. Unlike RP, which triggers indemnities based on farm-level losses, ECO triggers an indemnity based on county-wide losses and will trigger a full indemnity when county-level revenue losses fall to 86%.

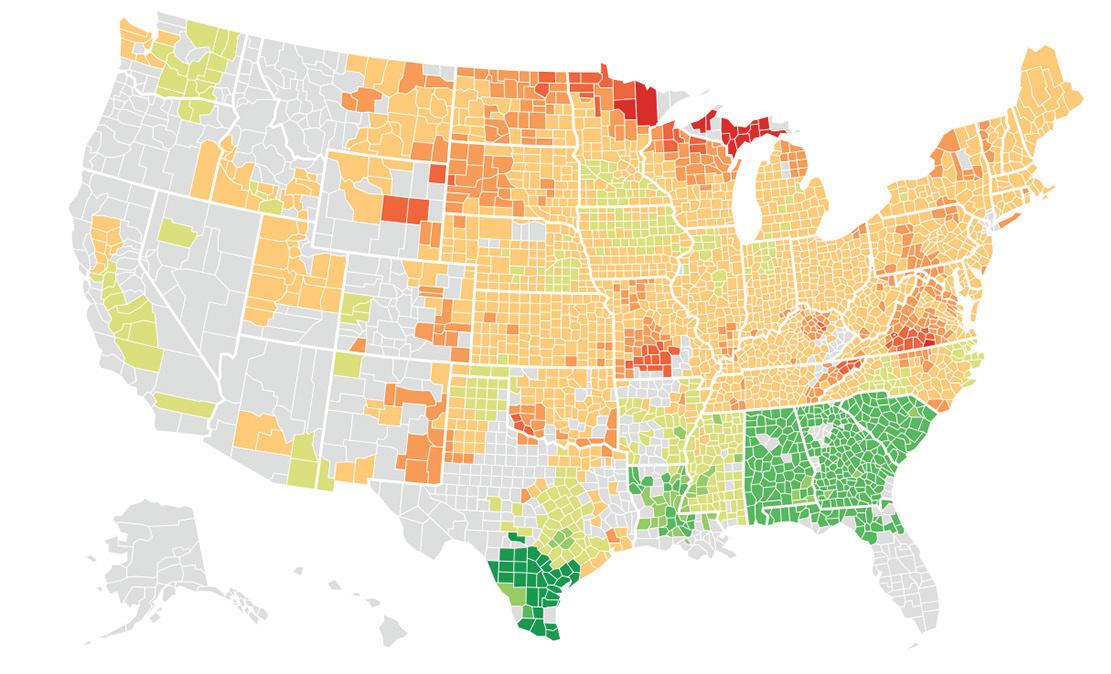

A county-level map shows the extent the nal county yield can change relative to the

expected yield and still trigger an indemnity for corn that is equal to the producer-paid premium. In other words, this map answers the question of how much the county yield must change to trigger an indemnity that will at least cover the premium. For RP, the premium was determined at 75% coverage under optional units paired with ECO at the 95% coverage level with the associated premium subsidy rate applied. Projected and harvest prices reported by the RMA Price Discovery Tool are used with the associated price volatility.

For example, a county in the darkest green shows that the nal county yield may increase at least 21%-26% for an indemnity to trigger. is suggests the price decline in the futures market was severe enough to allow for yield upside risk that would o set indemnities triggered on price alone. Conversely, a county shaded in the darkest red indicates the nal county yield must decline at least 6%-11% before a large enough indemnity to cover the producer premium is triggered. is implies that the price decline was not severe enough to trigger an indemnity on price alone. Most counties have experienced severe enough price declines that corn yield can increase in comparison to expected yield and potentially obtain a net indemnity above zero (e.g., yellow and green counties). For maps on co on, soybeans and rice, go to www.southernagtoday.com.

Article by Hunter Biram, University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture.

This map shows the percentage change in the final county corn yield relative to the expected yield required to trigger an ECO indemnity that will be equal to producer-paid premiums. This assumes RP and ECO coverage levels of 75% and 95%, respectively.

The line from the classic musical “Oklahoma” that refers to corn being “as high as an elephant’s eye” would not apply to some new hybrids. Reduced-stature corn, also referred to as “short” corn, is a concept researchers at Auburn University are looking at to determine if there’s a fit on Alabama farms.

While reducing plant height has been an important innovation in other crops, such as wheat and rice, it has not been successfully deployed in corn. The need to boost corn yields but also increase resilience against severe weather has brought renewed focus.

“Short corn is a type of corn plant that is 2 feet to 3 feet shorter than conventional corn,” says Eros Francisco, Extension agronomist at Auburn University’s Department of Crop, Soil and Environmental Sciences. “It brings some definite advantages to growers, such as increased protection from lodging and greater application flexibility, as in the possibility to perform ground-spraying applications later than conventional corn, which can contribute to higher potential yield.”

The hybrids are a result of natural breeding and may present a lower demand for water and nutrients. The short-stature corn plant is like a conventional plant in the number of leaves, nodes and ears produced, Francisco says. The only difference is height.

“The internodes produced below the ear height are shorter than normal, but the internodes produced above the ear are the same as on conventional corn,” he says. “Research and commercial field data from the Midwest, where short corn is more widely grown, have demonstrated similar yield potential with these hybrids.”

Short corn requires a higher seeding rate, between 38,000 to 44,000 seeds per acre, since plants are smaller in size and do not occupy as much space as conventional plants. Harvesting is another piece of the puzzle to be considered.

Francisco says when corn is grown in a low- to medium-fertility soil or when it faces drought conditions, the short corn ears may end up lower and closer to the ground, complicating combine head pick up.

Overall, he says these hybrids show tremendous promise in their ability to yield well and tolerate higher plant populations and narrower rows. However, many physiological and management questions remain and will continue to be investigated by researchers.

Several companies have begun introducing short-stature corn hybrids, including Bayer’s Preceon Smart Corn System, which is currently being grown on three units of the Alabama Agricultural Experiment Station.

“Field corn is an important crop for Alabama growers because it is used in cattle and

poultry feed, both large sectors of the state’s ag economy,” Francisco says. “Corn also fits very well into our cropping systems as a good option for a summer cash crop alternating with soybean and winter wheat. In addition, it has been a good rotational crop for cotton producers fighting nematode problems.” CS Article provided by Auburn University College of Agriculture.

Corn leafhoppers have re-emerged in some Texas regions and other states, threatening both yields and grain quality.

David Kerns, Texas a&M agriLife Extension Service statewide integrated pest management coordinator and associate department head for the Department of Entomology, says corn producers need to become familiar with the insect and learn more about management strategies.

“Certainly, growers need to be aware of this going into the next growing season,” he says. “It’s a big issue. Corn leafhoppers could transmit pathogens, which can lead to diseases and other problems associated with growing a good, healthy corn crop.”

Corn leafhoppers were reported as far north as Ohio in 1981. In 2016, it re-emerged as a pest in South Texas. This year, outbreaks were reported in Tamaulipas, Mexico, and became widely distributed in Texas, Oklahoma, eastern new Mexico, Kansas, Missouri, Georgia and arkansas. They were reported in Illinois, Indiana, nebraska, Minnesota and Wisconsin late in the season.

Corn leafhopper produces a sugary substance called honeydew that can grow on stalks and leaves and lead to the growth of sooty mold, which may block leaf photosynthesis.

The biggest concern is red stunt disease due to the four main plant pathogens corn leafhoppers transmit. Symptoms include yellowing and reddening leaves, rapid dying of lower canopy, dying of ear leaf and corn husks, poor pollination and extensive blank ear tips, incomplete kernel fill, stunted or excessively thin and tall plants, formation of multiple deformed ears from the primary ear position and abnormal tillering.

Corn leafhoppers can survive at temperatures of 50 degrees Fahrenheit to 68 degrees. Kerns says corn is the best host, but the insects can survive on grass species such as eastern gamagrass when corn is not

Farmers using Pivot Bio’s Proven 40 microbial nitrogen are realizing significant plant health benefits and stronger return on investment despite early season weather challenges. as part of their ongoing support for farmers facing tough economics, the company announced a lower price for its product for the 2025 growing season alongside a 0% financing program.

“We understand the evolving financial dynamics that farmers are facing,” says Chris Turner, Pivot Bio chief commercial officer. “We want to meet farmers where they are and set them up for success year after year. We’re proud to provide farmers with the tools they need to farm more confidently and mitigate risks effectively.”

Corn leafhopper has re-emerged in some regions and threatens both yield and grain quality.

available. Corn is needed for the insect pest to reproduce. “It can also survive on sorghum and johnsongrass and may survive as long as one month,” Kerns says.

Farmers can follow these suggestions to lessen the leafhopper threat:

■ Plant a corn hybrid that is less affected than others. a resistant hybrid is not currently an option. research is ongoing to determine hybrids that are least sensitive.

■ Manage volunteer corn. In areas that do not experience freezing temperatures, it is essential to eliminate volunteer corn that can serve as a host.

■ Plant as early as possible. Early planted corn has been shown to escape corn leafhopper infestations and subsequent issues during the critical infestation period, emergence through stage V8.

■ use an insecticide during emergence through V8 when corn leafhoppers are detected, especially for late-planted corn or second-crop corn. Kerns says insecticides such as Sivanto Prime and Transform are options, although the effectiveness of these products has not been fully evaluated. CS

a national study from 2022-2024 showed that corn treated with Proven 40, a microbially derived nitrogen source, had an average 9% increase in in-plant nitrogen compared to the standard practices. During that same three-year period, farmers experienced, on average, nearly a bushel-per-acre yield advantage when replacing nearly 40 pounds of nitrogen with Proven 40.

Pivot Bio’s proprietary gene-edited mi-

crobes fix nitrogen directly to the plant, spoon-feeding it to the roots. This allows crops to utilize both microbial and traditional nitrogen sources. When farmers replace up to 40 pounds of nitrogen with microbial nitrogen, they can diversify their fertilizer management plans and solve for a percentage of nitrogen loss to maintain or improve their yield.

For more information, visit PivotBio.com.