9 minute read

Stomach

Interventional procedures Skin punctures lateral to the rectus muscles, or in the midline, w i ll avoid the epigastric vessels. Catheter placement that avoids the recti is also better tolerated.

Contrast urethrography In the ruptured anterior urethra contrast can be seen to extravasate into the scrotum, perineum and penis, and then on to the lower abdominal wall because of the attachments of Scarpa's and Colles' fascia.

Advertisement

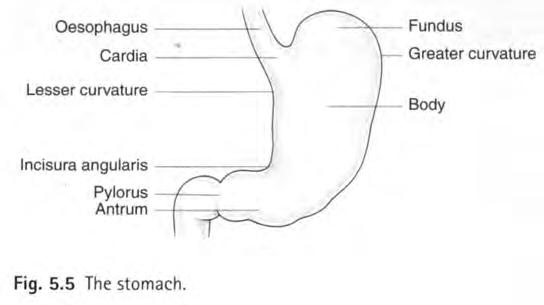

THE STOMACH (Figs 5.5-5.9) The stomach is J-shaped but varies in size and shape w i th the volume of its contents, w i th erect or supine position, and even w i th inspiration and expiration. The size and shape of the stomach also vary considerably from person to person, differing especially w i th the build of the subject.

The stomach has two orifices - the cardiac orifice (so named because of proximity through the diaphragm to the heart) at the oesophagogastric junction, and the pylorus. It has two curvatures - the greater and lesser curves. The incisura is an angulation of the lesser curve.

The part of the stomach above the cardia is called the fundus. Between the cardia and the incisura is the body of the stomach, and distal to the incisura is the gastric antrum. The lumen of the pylorus is referred to as the

pyloric canal.

The stomach is lined by mucosa, which has tiny nodular elevations called the areae gastricae and is thrown into folds called rugae. Longitudinal folds paralleling the lesser curve are called the 'magenstrasse' meaning 'main street'. Rugae elsewhere in the stomach are random and patternless.

There are three muscle layers in the wall of the stomach: (i) an outer longitudinal, (ii) an inner circular and (iii) an incomplete, innermost oblique layer. The circular layer is thickened at the pylorus as a sphincter, but not at the oesophagogastric junction. Fibres of the oblique layer loop around the notch between the oesophagus and the fundus and help to prevent reflux here. The oblique fibres are responsible for the 'magenstrasse' and can pinch off the remainder of the stomach and allow fluids to pass directly from oesophagus along the lesser curve to the duodenum.

Peritoneum covers the anterior and posterior surfaces of the stomach and is continued between the lesser curve and the liver as the lesser omentum, and beyond the greater curve as the greater omentum.

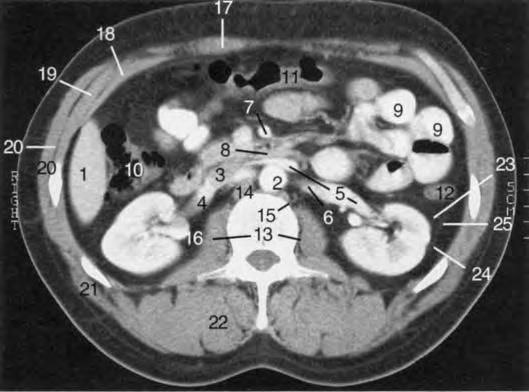

Fig. 5.4 CT scan: level of renal hila (L2).

1. Right lobe of liver 14. Lower end crus of 2. Aorta right hemidiaphragm 3. Inferior vena cava 15. Lower end crus of left 4. Right renal vein hemidiaphragm 5. Left renal vein 16. Right renal pelvis 6. Left renal artery 17. Rectus abdominis muscle 7. Superior mesenteric artery 18. Transversus abdominis muscle 8. Third part of duodenum 19. Internal oblique muscle passing between aorta 20. External oblique muscle and superior mesenteric 2 1. Latissimus dorsi muscle artery 22. Erector spinae muscle 9. Loops of small bowel 23. Gerota's fascia 10. Ascending colon 24. Fascia of Zuckerkandl 11. Transverse colon 25. Lateral conal fascia 12. Descending colon (fusion of Gerota's fascia 13. Psoas muscle and fascia of Zuckerkandl)

Anterior relations of the stomach

The upper part of the stomach is covered by the left lobe of the liver on its right and by the left diaphragm on the left. The fundus occupies the concavity of the left dome of the diaphragm. The remainder of the anterior of the stomach is covered by the anterior abdominal wall.

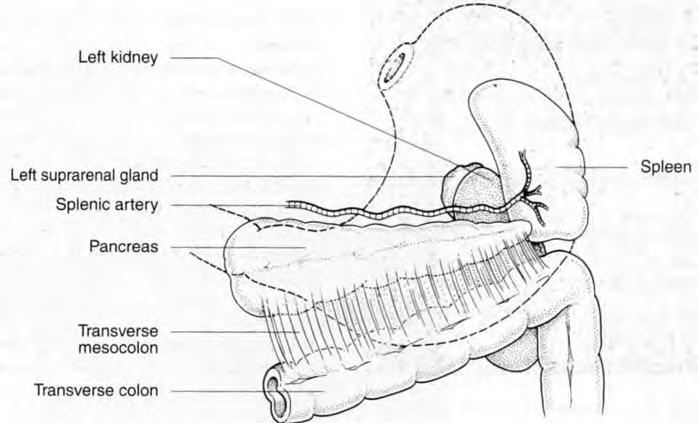

Posterior relations of the stomach (see Fig. 5.6) Posterior to the stomach lies the lesser sac (see Peritoneal spaces of the abdomen later in the chapter, and Figs 5.53 and 5.54). The structures of the posterior abdominal wall

Fig. 5.6 Posterior relations of the stomach (viewed from anterior through the stomach).

that are posterior to this are referred to as the stomach bed. The pancreas lies across the midportion of the stomach bed w i th the splenic artery partly above and partly behind it, and the spleen at its tail. Above the pancreas are the aorta and its coeliac trunk and surrounding plexus and nodes, the diaphragm, the left kidney and the adrenal gland. Attached to the anterior surface of the pancreas is the transverse mesocolon, which forms the inferior part of the stomach bed.

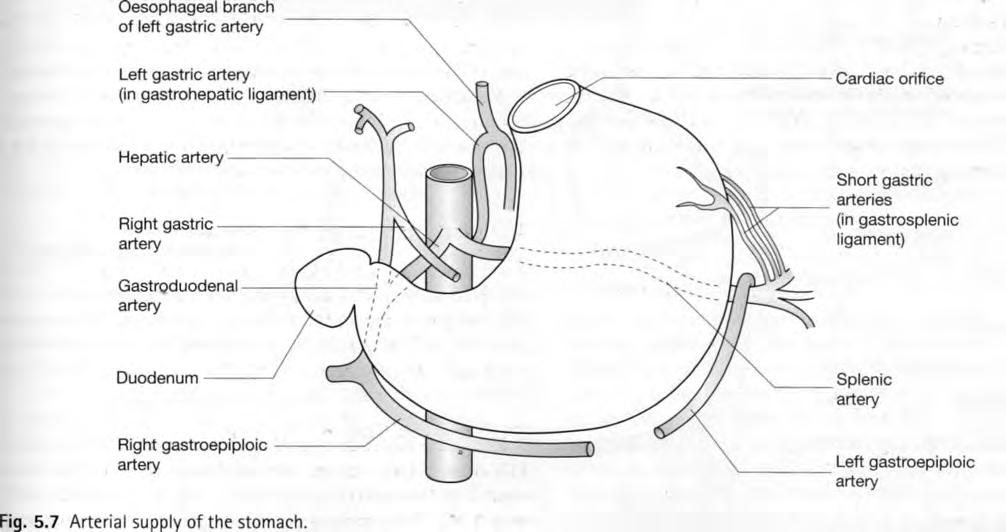

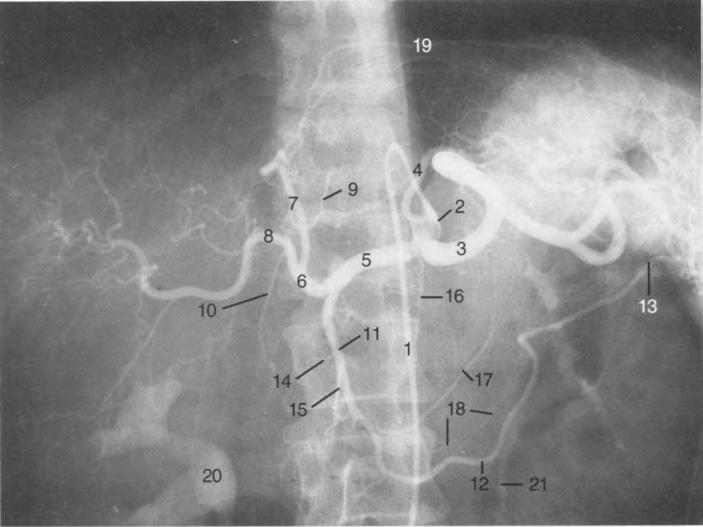

Arterial supply of the stomach

(Fig. 5.7, see also Figs 5.12 and 5.13) Arteries reach the stomach along its greater and lesser curves from branches of the coeliac trunk as follows: • The left gastric artery from the coeliac trunk supplies the lesser curve. • The right gastric artery from the hepatic artery supplies the lesser curve.

• The short gastric arteries from the splenic artery supply the greater curve and fundus. • The left gastroepiploic artery from the splenic artery supplies the greater curve. • The right gastroepiploic artery from the gastroduodenal branch of the hepatic artery also supplies the greater curve.

The left gastric artery also supplies branches to the lower oesophagus.

The arteries of the stomach anastomose freely within the stomach wall, unlike the arteries of the small and large intestine, where the vessels that enter the gut wall are end arteries.

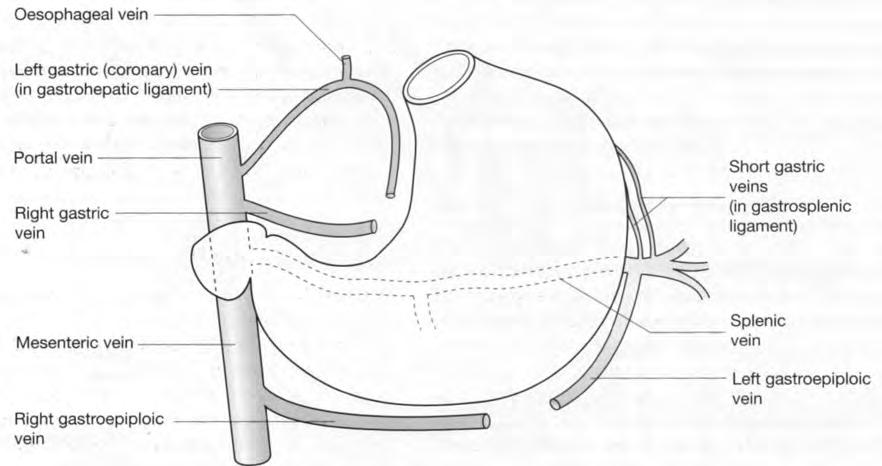

The venous drainage of the stomach (Fig. 5.8) The venous drainage of the stomach follows a similar pattern to the arterial supply: • The right gastric vein drains to the portal vein. • The left gastric vein drains to the splenic vein. • The short gastric and left gastroepiploic veins drain to the splenic vein. • The right gastroepiploic vein drains to the superior mesenteric vein.

The left gastric vein, also known as the coronary vein, receives blood from the lower third of the oesophagus.

Lymph drainage of the stomach

Lymph drainage also follows the arterial pattern and drains to nodes around the coeliac trunk: • The left gastric artery drains directly to coeliac nodes. • The right gastric artery drains via retroduodenal nodes to coeliac nodes. • The short gastric and left gastroepiploic arteries drain via nodes in the splenic hilum and behind the pancreas to coeliac nodes. • The right gastroepiploic artery drains via retroduodenal nodes to coeliac nodes.

The coeliac nodes drain to the cisterna chyli.

Radiological features of the stomach

Plain film of the abdomen (see Fig. 5.1) If a radiograph is taken in the erect posture, a long fluid level is seen in the fundus. This is because the antrum and body contract when empty and a relatively small amount of fluid and gas in the fundus can produce a long fluid level.

In a supine view, the gas in the rugae on the anterior wall of the stomach gives a linear pattern. On intravenous urography (IVU) studies the rugae may enhance w i th contrast on early films and should not be interpreted as a left renal or adrenal mass.

Double-contrast barium-meal examination (Fig. 5.9) Features of the stomach, such as the greater and lesser curves, the incisura, the cardia, fundus, body, antrum and pylorus, can be seen. The change in position of these w i th posture and respiration can be appreciated on fluoroscopy.

The areae gastricae can be seen as small nodular elevations of 2-3 mm in diameter. The rugae are 3-5 mm in thickness. These are effaced by gastroparetic agents such as

Fig. 5.8 Venous drainage of stomach.

Fig. 5.9 Barium-meal technique. This film demonstrates the various rugal and mucosal folds in the stomach and in the non-distended duodenum.

1. .Lesser curve of stomach 2. Greater curve of stomach 3. Longitudinal mucosal folds (magenstrasse) 4. Gastric rugae 5. Areae gastricae 6. Incisura 7. Duodenal cap (partially gas-distended) 8. Mucosal pattern of non-distended duodenum

glucagon or hyoscine butylbromide (Buscopan). The long rugae of the 'magenstrasse' paralleling the lesser curve can also be seen.

Compression views can only be obtained of that part of the stomach w i th the anterior abdominal wall as an anterior relation, that is, the lower body and the antrum.

CT and MRI of the stomach

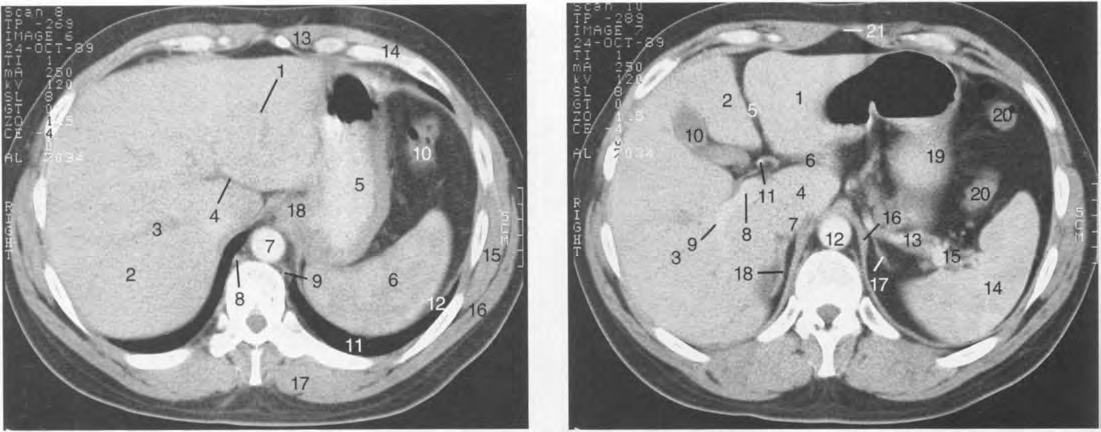

The relationship of the stomach to the structures of the stomach bed, such as the pancreas, the aorta, the spleen and the left kidney and adrenal, can be seen (Figs 5.10 and 5.11; see also Fig. 5.2).

Close to the gastro-oesophageal junction the stomach is attached to the liver by the gastrohepatic ligament. The fundus of the stomach may project posteriorly if redundant and appear as a pseudoadrenal lesion on CT and MRI. The thickness of the stomach wall varies considerably depending on the degree of distension and can appear thickened in the fasting state. Food in the stomach can appear as a pseudomass, and is seen especially in the dependent portion.

The mucosa of the stomach enhances w i th intravenous contrast and the stomach layers are best appreciated in the arterial phase of contrast enhancement, when there is no positive contrast in the stomach.

Ultrasound studies of the abdomen

These are limited by the presence of intraluminal gas in the stomach and bowel. Structures in the stomach bed cannot be seen through the stomach if this is filled w i th gas. If the stomach is gas free or fluid filled, then the pancreas and the aorta and coeliac trunk can be well seen. The antrum and gastro-oesophageal junction can normally be identified by their characteristic hypochoic muscular layer surrounding echogenic mucosa. The gastro-oesophageal junction is seen as a small rounded structure behind the top of the left lobe

Fig. 5.10 CT upper abdomen: level of gastro-oesophageal Fig. 5.11 CT abdomen: level of body of stomach (T11). junction (T10).

1. Left lobe of liver 10. Splenic flexure 1. Left lobe of liver: 11. Hepatic artery

2. Right lobe of liver

11. Left lung 3. Right branch of portal vein 12. Left diaphragm 4. Fissure for ligamentum 13. Rectus abdominis muscle

lateral segment 2. Left lobe of liver: medial segment

12. Abdominal aorta 13. Splenic artery 14. Spleen venosum 14. External oblique muscle 3. Right lobe of liver 15. Splenic vein 5. Contrast medium in stomach 15. Serratus anterior muscle 4. Caudate lobe of liver 16. Left crus of diaphragm 6. Spleen 16. Latissimus dorsi muscle 5. Fissure for ligamentum teres 17. Left adrenal gland 7. Descending aorta 17. Erector spinae muscle 6. Fissure for ligamentum 18. Right adrenal gland 8. Azygos vein 18. Oesophagogastric junction venosum 19. Stomach 9. Hemiazygos vein 7. Inferior vena cava 20. Splenic flexure 8. Portal vein 2 1. Linea alba (aponeurosis of 9. Right branch of portal vein rectus sheath) 10. Gallbladder

Fig. 5.12 Coeliac axis angiogram.

1. Catheter in aorta 2. Catheter tip in coeliac trunk 3. Splenic artery 4. Left gastric artery 5. Common hepatic artery 6. Hepatic artery proper 7. Left hepatic artery 8. Right hepatic artery 9. Right gastric artery 10. Cystic artery 11. Gastroduodenal artery 12. Right gastroepiploic artery 13. Left gastroepiploic artery 14. Posterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery 15. Anterior superior pancreaticoduodenal artery 16. Dorsal pancreatic artery 17. Transverse pancreatic artery 18. Gastric branches of gastroepiploic artery 19. Phrenic branch of left hepatic artery 20. Contrast in right renal pelvis 2 1. Left ureter