ATLAS :: being in place

Michel Boucher

ON SITE r e v i e w 42:

2023

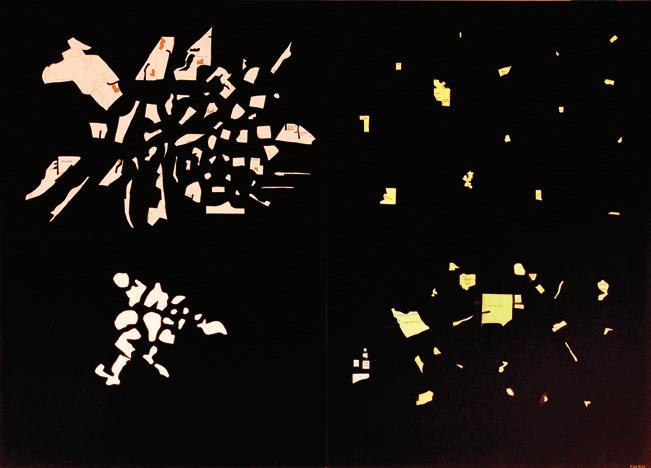

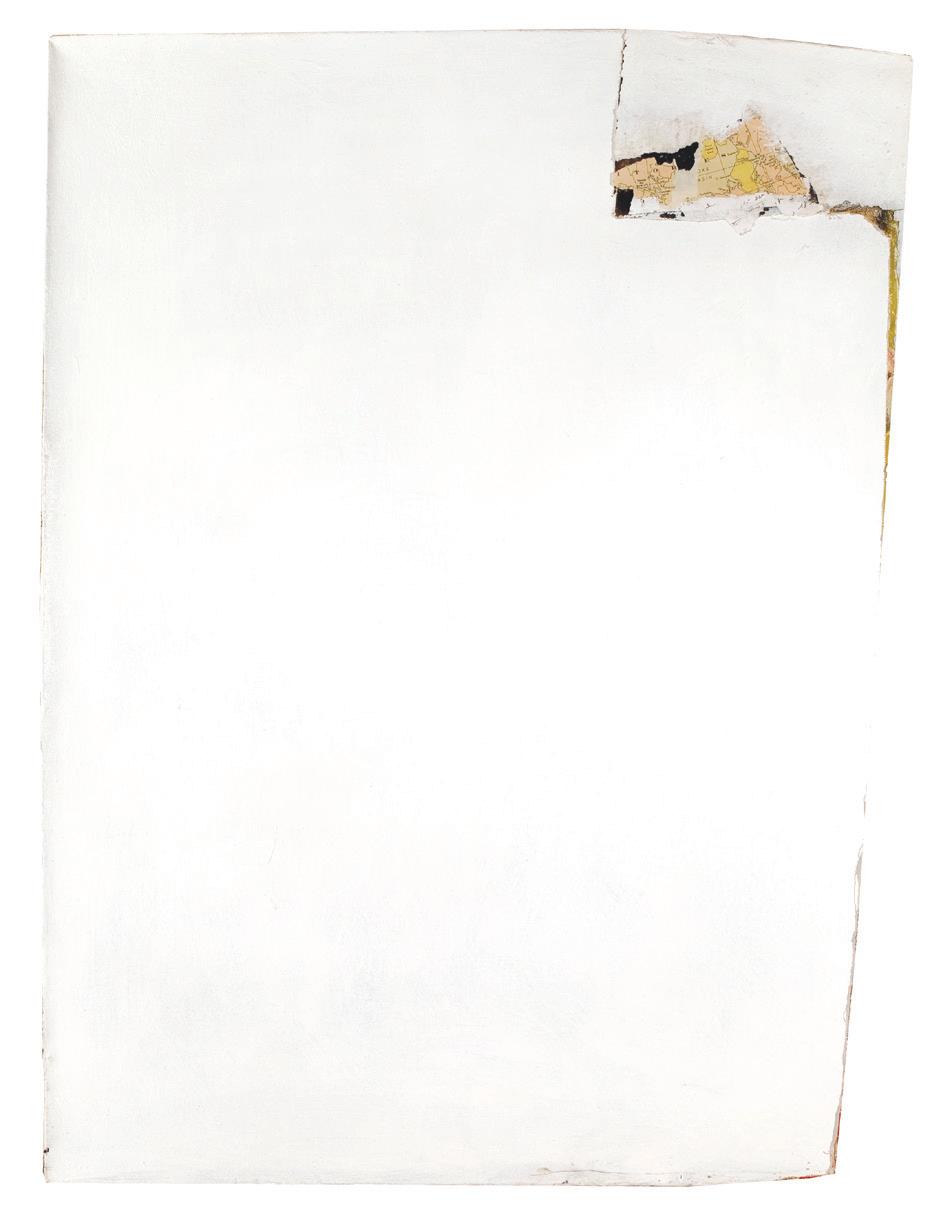

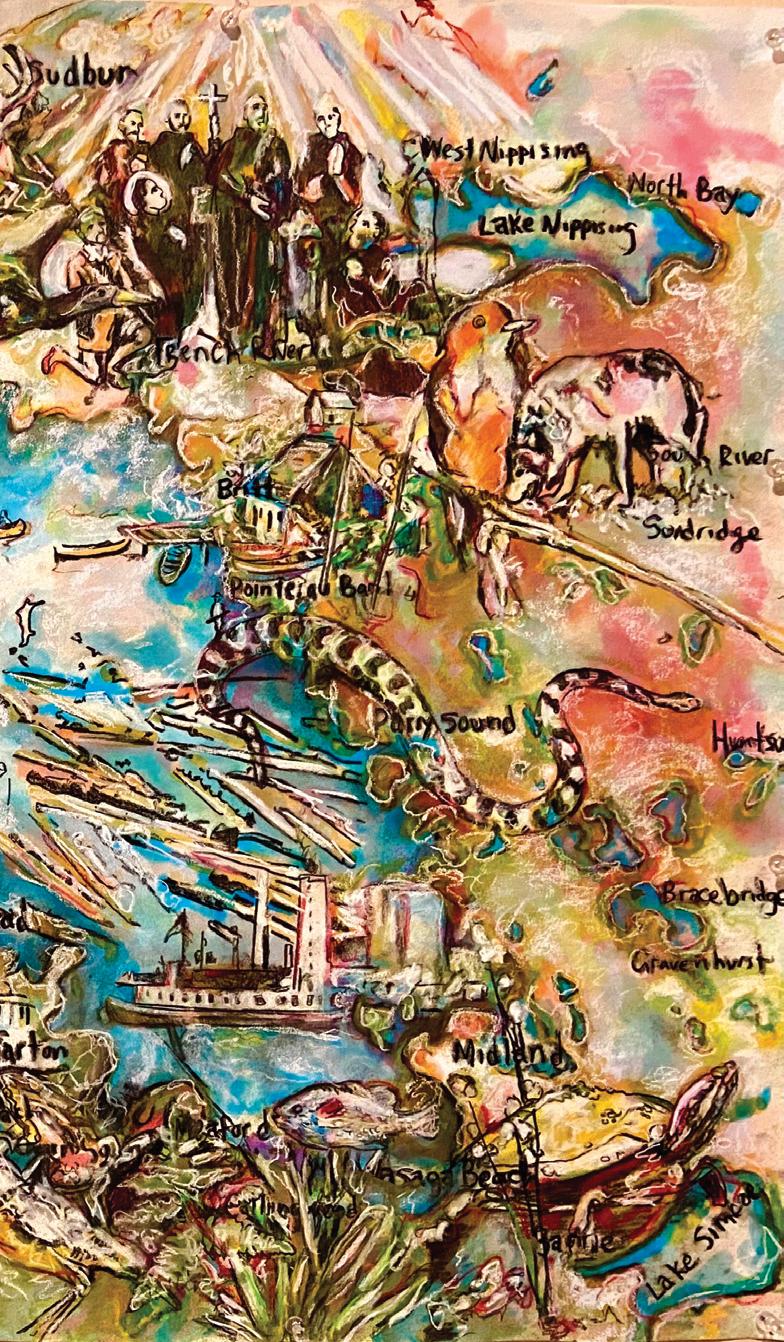

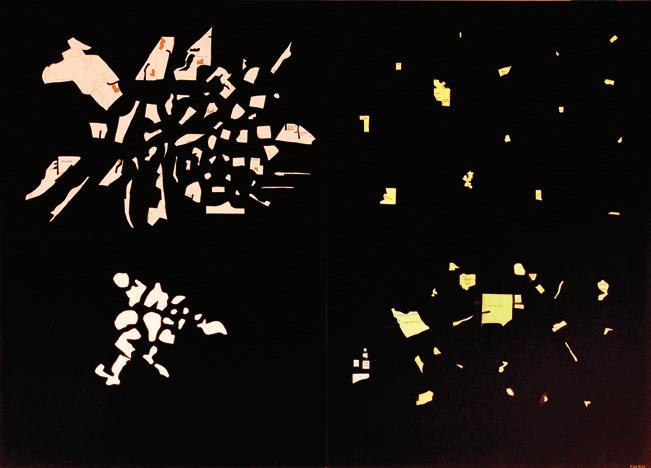

Francesca Vivenza A Painting Remembered, 2006 acrylic, fragments of maps on canvas 105 x 81 cm www.francescavivenza.com

Jordana Dym and Karl Offen, editors

Mapping Latin America: a cartographic reader Chicago: Univerity of Chicago Press, 2011

https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/ chicago/M/bo6225459.html

books

Mirella Altic, Encounters in the New World: Jesuit Cartography of the Americas Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2022

https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/ book/chicago/E/bo95833620.html

Simonetta Moro. Mapping Paradigms in Modern and Contemporary Art: Poetic Cartography. London and New York: Routledge, 2021

https://www.routledge.com/Mapping-Paradigmsin-Modern-and-Contemporary-Art-PoeticCartography/Moro/p/book/9781032052045

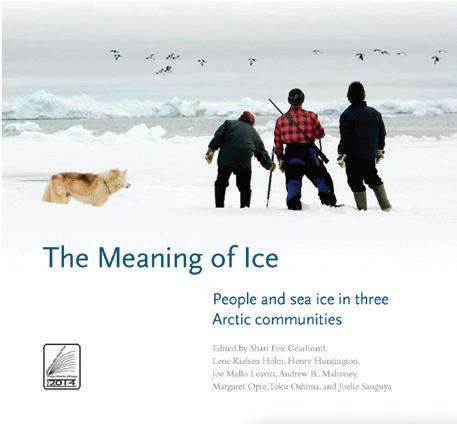

Shari Fox Gearheard, Lene Kielsen Holm, Henry Huntington, Joe Mello Leavitt, Andrew R. Mahoney, Margaret Opie, editors

The Meaning of Ice: People and Sea Ice in Three Arctic Communities

International Polar Institute 2017 https://www.nhbs.com

https://www.amazon.ca/Meaning-Ice-People-ArcticCommunities/dp/0982170394

Linda Tuhiwai Smith, Decolonizing Methodologies Bloomsbury Publishing. NY 2021

https://www.bloomsbury. com/ca/decolonizingmethodologies-9781786998132/

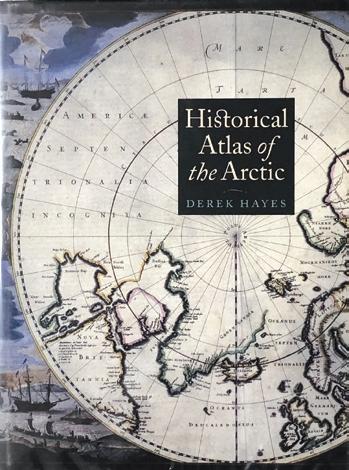

Derek Hayes, Historical Atlas of the Arctic Seattle: University of Washington Press / Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre. 2003

https://uwapress.uw.edu/ book/9780295983585/historical-atlas-of-thearctic/

longing

joseph heathcott

joseph heathcott

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 1

maps and mapping

stephanie white

'...In that Empire, the Art of Cartography attained such Perfection that the map of a single Province occupied an entire City, and the map of the Empire, an entire Province. In time, these Excessive Maps did not satisfy and the Schools of Cartographers built a Map of the Empire, that was of the Size of the Empire, and which coincided point for point with it. Less Addicted to the Study of Cartography, the Following Generations understood that the dilated Map was Useless and, not without Pitilessness, they delivered it to the Inclemencies of the Sun and the Winters. In the Deserts of the West endure broken Ruins of the Map, inhabited by Animals and Beggars; in the whole country there is no other relic of the Disciplines of Geography.

Suárez Miranda: Viajes de varones prudentes, libro cuarto, cap. XLV, Lérida, 1658'1

1 Jorge Luis Borges. 'Del rigor en la ciencia' (1946) Historia universal de la infamia, Argentina: Emecé, 1954

Diego Doval, English translation, 2017

This very short story, in its entirety, is an invented quotation on a theme covered by Lewis Carroll's 1895 Sylvie and Bruno Concluded. It is quoted in Umberto Eco's 'On the Impossibility of Drawing a Map of the Empire on a Scale of 1 to 1' in How to Travel with a Salmon and Other Essays, 1995

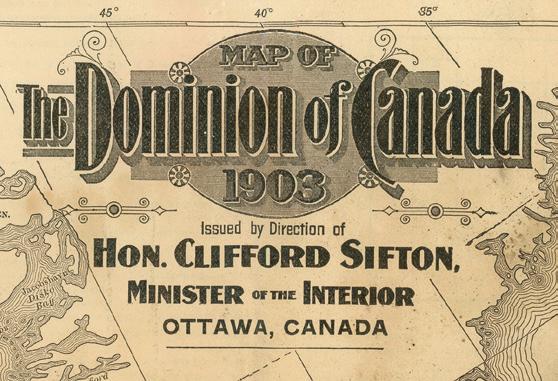

On Site review seems to visit maps and mapping frequently, but never as concentratedly as this issue. Maps are essential tools of exploration and conquest: if it can be measured, it can be drawn. If it can be drawn, it can be sold. If it is owned, it can be occupied. Latin Americans have had longer to ponder all this, their period of Spanish and Portuguese colonisation, said to be from 1492 with the arrival of Columbus to 1832 and the onset of the Spanish American wars, left two occupied continents, a postcolonial condition that reverberates from north to south still.

In On Site review 31, Rodrigo Barros, at the time living in Valpairiso, inverted the Mercator projection to position the South as the site of hopes and dreams, not North America, the escalator of power and interference.

The 1913 drawing superimposing European countries on the South American continent, points out just how small and overly-intense Europe was just before WWI. Land mass was not power, influence was. The Mercator projection was never a scientific drawing of the globe, it privileges the North, reducing the two continents of the South to elements smaller than Greenland. Distortions, always distortions.

Many of the essays and projects in this issue of On Site review re-think the recording of land by starting with the foot on the ground, rather than the pen on the paper. Possession becomes presence; occupation becomes belonging. This can be read as both dominion and reclamation. Like the inverted North-South drawing, it depends where one stands.

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 2

an unused image found on a website now vanished. My notes say it was drawn in 1913.

Rodrigo Barros 2014

ON SITE r e v i e w 42: atlas :: being in place

spring 2023

On Site review is published by Field Notes Press (1986), which promotes field work in matters architectural, cultural and spatial.

contents

introduction

Joseph Heathcott

Stephanie White

Jeff Thomas

Michael Farnan

cartographies: longing maps and mapping

deep roots complex systems

Susan Shantz

Michelle Wilson

Yana Kigel

Dalia Munenzon

mapping Iroquoia mapping the Georgian Bay watershed

Confluence: the Saskatchewan River tracing carefull paths

moral implications: urbanism and wildlife drawing water from arid lands

urban markers

John Barton

Joseph Heathcott

mapped by poetry: The Troubles

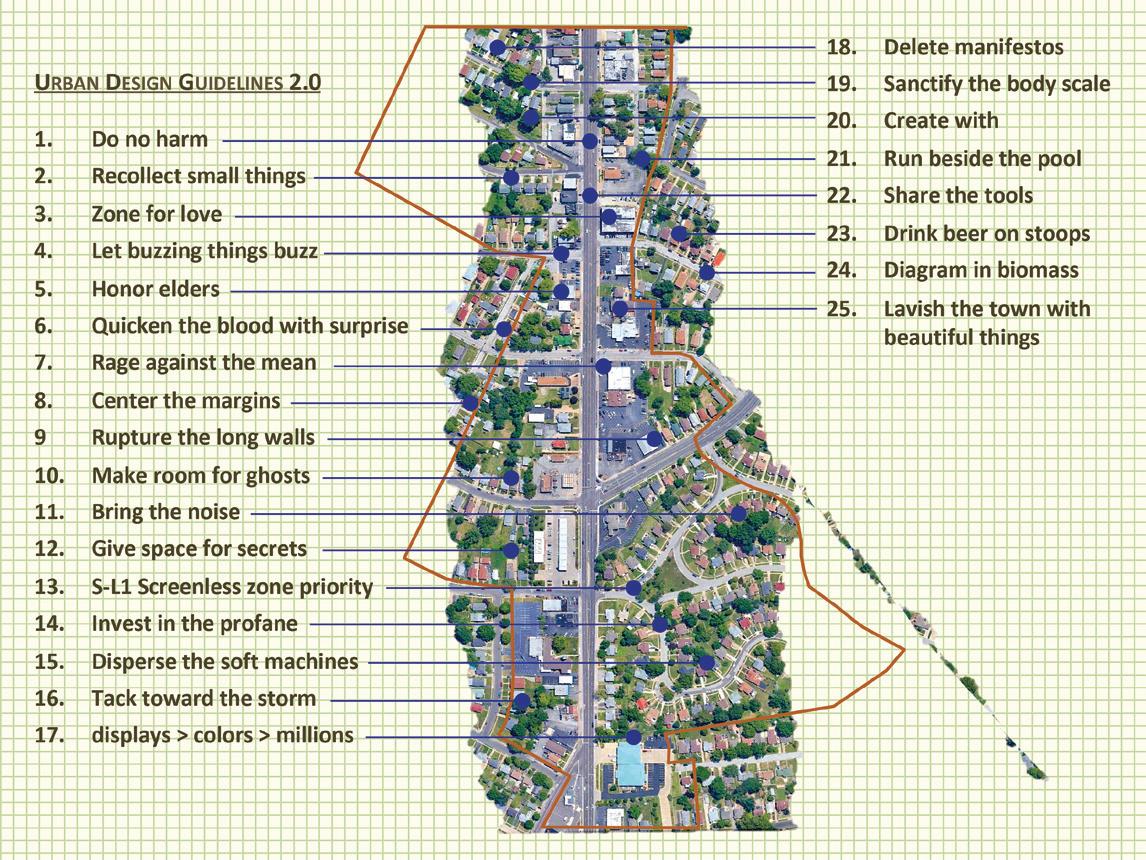

cartographies: urban design guidelines 2.0

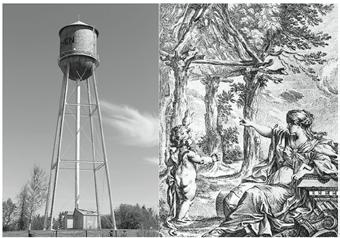

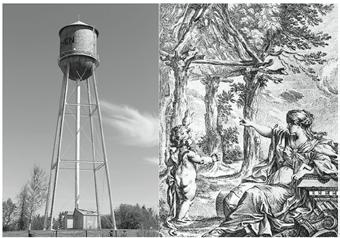

Always quite liked that for Abbé Laugier, the muse of architecture was female, and there she is, holding her divider, classical architecture in ruins at her feet. For us, it is not the primitive hut that is interesting, it is the water tower.

Lejla Odobašic Novo +Aleksandar Obradovic

Francesca Vivenza

Patrick Mahon+Thomas Mahon

Lisa Rapoport

mysteries emigration

Yvonne Singer

Salah D Hassan

cartographies: decolonising Manhattan (re)mapping: politics in urban space exchange an uncertain proposition

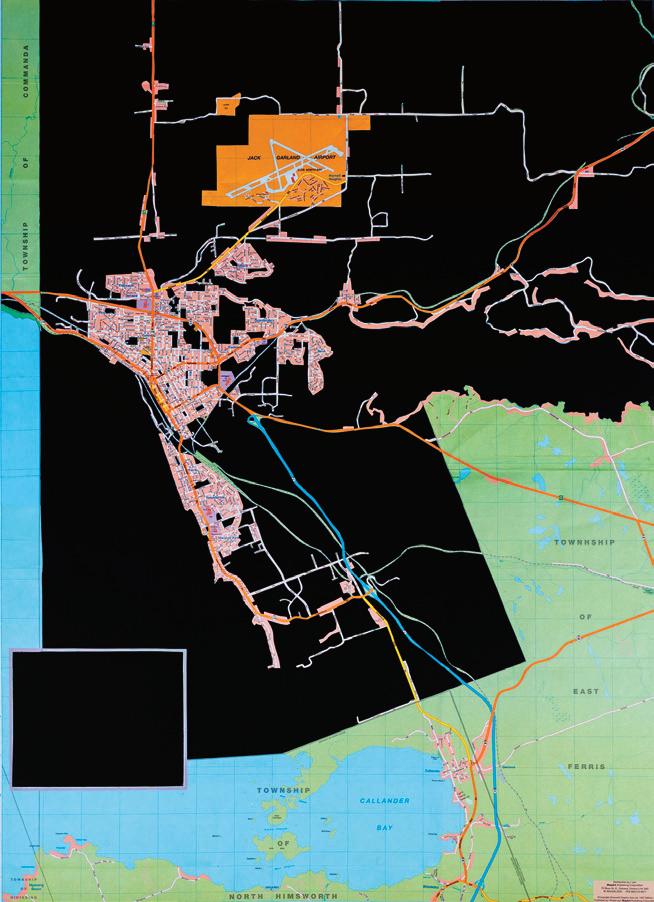

un-mapping: Autoroute10; Thunder Bay

the certificaat uncertain cartographies

colonial processes

David Murray

Peter Kuper

Stephanie White

maps as archives

2018 Trumpworld on some maps; 1929, slippage

calls for articles masthead

43: temporary architecture

44: architecture and play

Joseph Heathcott covers

Francesca Vivenza

Yvonne Singer

cartographies: urban powerpoint

who we are

front: A Painting Remembered back: Gone Missing

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 3

F I E L D N O T E S

1 2 4 8 10 16 20 26 30 31 32 34 38 39 40 46 48 53 60 61 62 6 3 64

´ ´

mapping Iroquoia

jeff thomas

First came the field-work, next the conversation, then seize the space.

1. Wampum Belt #1 White Corn (2014/2018) pigment print on archival paper

left to right:

Jeff Thomas: Emily General (1985) Smooth Town, Six Nations Reserve. GPS: 43.01945, -80.08303

Emily General is my great-aunt and sister to my step-grandfather Bert General. Emily was instrumental in helping me define my sense of place as an urban Iroquoian. When I entered university in 1975 she gave me her copy of the handwritten story of the Peacemaker and his journey to bring peace to the warring Iroquois tribes in present-day New York State. Emily told me I could not use a photocopy machine, I had to make my own hand-written copy of the 1900 document. I did and it has been instrumental for my development as a visual artist and curator.

Jeff Thomas: Old Chair outside Emily General’s kitchen door (1985) Six Nations Reserve, Ontario. GPS: 43.01945, -80.08303

I photographed the old chair sitting outside of Emily’s kitchen door because it reminded me of the times I sat at the kitchen, listening to my elders tell stories about the old days, gossip, the price of farm animals, etc. I thought that might be my last visit to the farm and I wanted an image to remember my time with Emily.

Jeff Thomas: Drying white corn braided by Bert General (1990) Six Nations Reserve, Ontario. GPS: 43.018067 -80.08955

Francis Knowles: Chief Jacob General (1912) Six Nations of the Grand River, Canadian Museum of History. GPS: 43.018067 -80.08955

Bert and Emily had provided me with enough information to begin my journey of discovery. The Hiawatha wampum belt commemorated the Peacemaker’s journey through ancient Iroquoia and the story Emily gave me became the prototype for this journey and would lead to my self-identification as an urban Iroquois.

2. Wampum Belt #2, Cold City Frieze (1997/2016)

left to right:

pigment print on archival paper

Jeff Thomas: Chief Red Jacket monument (1997) Forest Lawn Cemetery, Buffalo, New York. GPS: 42.92315,-78.8663

Jeff Thomas: Joseph Brant monument (1997) Brantford, Ontario. GPS: 43.14077, -80.26331

Jeff Thomas: Onondaga Chief Big Sky plaque (1997) Buffalo, New York. GPS: 42.829767,-78.773417

Jeff Thomas: IROQUOIS (1998) Place d’ Armes, Montreal, Quebec. GPS: 45.50485,-73.557667

Jeff Thomas: Point of View (2015) Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. GPS: 40.4391,-80.021367

4

Jeff Thomas, photo-based artist, independent curator, public speaker. https://jeff-thomas.ca

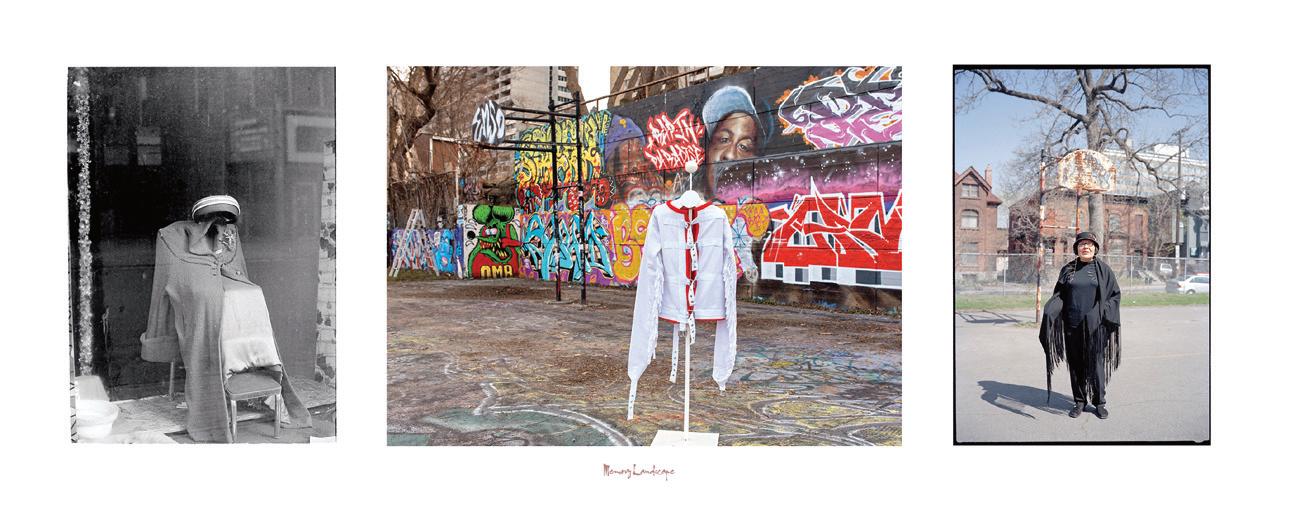

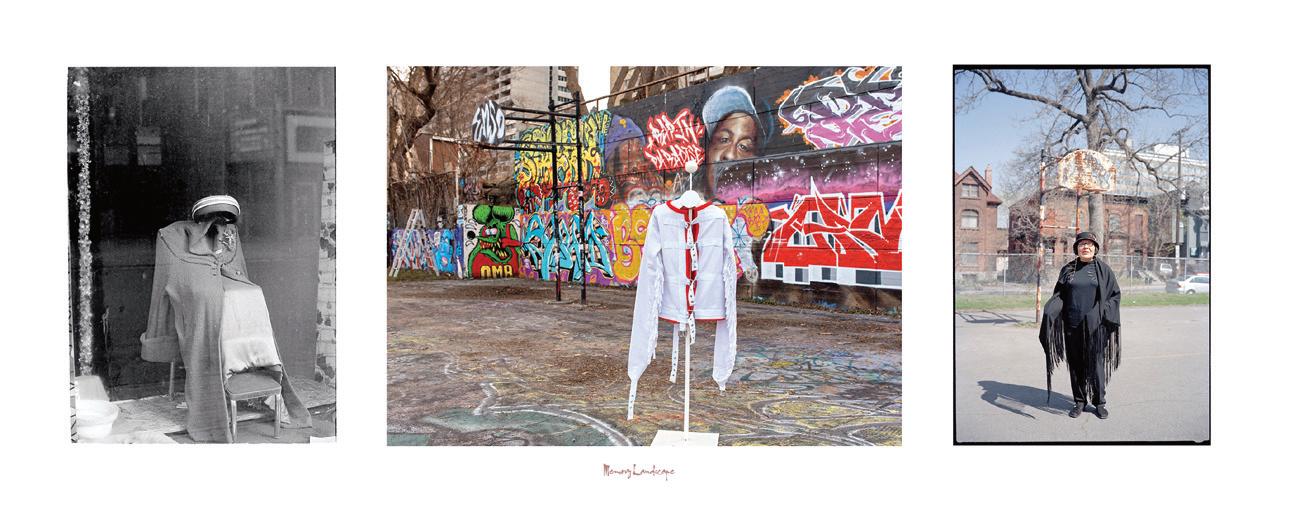

3. Memory Landscape (2015) pigment print on archival paper

While scouting the streets of Buffalo, New York, Toronto, Ontario, Winnipeg, Manitoba, and Ottawa, Ontario, for Indians, I have also questioned the stories the landscape has to tell me. Is there anything Indigenous about this landscape? I am speaking about the Europeanization of Turtle Island and how it inspired my quest to define my place as an urban-based Iroquois.

left to right:

Jeff Thomas: Storefront Window Display (1982) Allen Street, Buffalo, New York. GPS: 42.89918,-78.87084

Jeff Thomas: “This Is The Problem,” jacket by artist Tanya Harnett (2015) Tech Wall site, Slater & Bronson, Ottawa, Ontario. GPS: 45.41572, -75.70726

Jeff Thomas: Madeline Dion Stout, Cree (2002) Tech Wall site, Slater & Bronson, Ottawa, Ontario. GPS: 45.4153413 -75.7068984

4. Tailgate Family Portrait (2017) pigment print on archival paper

left to right:

Frank M. Pebbles (American, 1839-1928: Dr. Oronhyatekha (1841-1907), Royal Ontario Museum, ROM2008_10224_1. GPS: 43.6677 -79.39477

ORONHYATEKHA 1841-1907 (Oh-ron-ya-TEK-a) The renowned Mohawk chief, orator and physician is buried in this churchyard. Born on the Grand River Reservation, he attended the Universities of Toronto and Oxford. At the age of twenty he was selected by the Six Nations to present official greetings to the visiting Prince of Wales. In 1871 he was a member of Canada’s first Wimbledon rifle team and in 1874 became President of the Grand Council of Canadian Chiefs. Oronhyatekha was largely responsible for the successful organization of the Independent Order of Foresters.

Jeff Thomas: Clara Thomas (my grandmother), Martin Thomas (my father), Bear (my son) and nephews, Cleve, Levi and Spencer Thomas (1990) Six Nations Reserve, Ontario. GPS: 43.018067 -80.08955

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 5

5. This Is Not Nostalgia #1 (2006/2016) pigment print on archival paper

A wistful or excessively sentimental yearning for return to or of some past period or irrecoverable condition.

left and right:

Jeff Thomas: Steve Thomas (Onondaga) (1990) Smooth Town, Six Nations Reserve, Ontario, photographed outside his home, GPS: 43.03222, -80.07591

centre:

John (Jan) Verelst: Brant 1710, courtesy Library Archives Canada/C-092419. GPS: 45.42005 -75.70789

Also known as Jan or Johannes (1648-1734), Verelst was a Dutch Golden Age painter, working in England, in the time of Queen Anne’s War.

6. This Is Not Nostalgia #2 (2006/2018) pigment print on archival paper

A wistful or excessively sentimental yearning for return to or of some past period or irrecoverable condition

left to right:

Jeff Thomas: Holland Antiques (1982) Buffalo, New York. GPS: 42.89916, -78.8773

John (Jan) Verelst: Hendrick (Theyanoguin) (1710) courtesy Library Archives Canada/C-092415. GPS: 45.42005, -75.70789

Jeff Thomas (Onondaga): self-portrait 1998, Samuel de Champlain monument, Ottawa, Ontario. GPS: 45.4294,-75.70145

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 6

:: deep roots

7. This Is Not Nostalgia #3 (2006/2018) pigment print on archival paper

A wistful or excessively sentimental yearning for return to or of some past period or irrecoverable condition.

left to right:

Jeff Thomas: Joseph Tehwehron David (1957–2004), (1997) Mohawk, artist, and veteran of the 1990 Oka Crisis, Kanehsatà:ke, Quebec. GPS: 45.47321, -74.125

John (Jan) Verelst: John of Canajoharie (1710) Courtesy Library Archives Canada/C-092417, LAC, Ottawa, Ontario. GPS: 45.42005, -75.70789

Jeff Thomas: Bear Thomas, Cayuga (1996) Samuel de Champlain Monument, Ottawa, Ontario. GPS: 45.4294, -75.70145

I discovered background information about the three men on my son Bear’s tee-shirt. The original image is a studio portrait (possibly in Omaha, Nebraska) by William Henry Jackson; the men are identified as Pawnee Scouts. The portrait’s date is circa 1868-1871.

(First from right) ‘Man who left his enemy lying in the water’, Raruur tkahaareesaaru ‘His Chiefly Night’, or ‘Night Chief’ Ticteesaaraahki’ ‘One who strikes the chiefs first’ Tirawa t Reesa ru’ ‘Sky Chief’ Standing, Baptiste Bayhylle, Resa ru’ Siriite‚riku “The Heavens See Him as a Chief”, Pawnee/French interpreter. The seated men are identified as brothers. Smithsonian Institution, National Anthropological Archives, 1297.

8. This Is Not Nostalgia #4 (2006/2018) pigment print on archival paper

A wistful or excessively sentimental yearning for return to or of some past period or irrecoverable condition

left to right:

John (Jan) Verelst: Nicholas the Mahican (1710) courtesy Library Archives Canada/C-092421. GPS: 45.42005, -75.70789

Jeff Thomas: Justice (2006) Department of Justice building, Ottawa, Ontario. GPS: 45.42142, -75.70399

Jeff Thomas: Arnold Boyer (Mohawk), (1998) Department of Aboriginal and Northern Affairs, Gatineau, Quebec. GPS: 45.42605, -75.72173

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 7

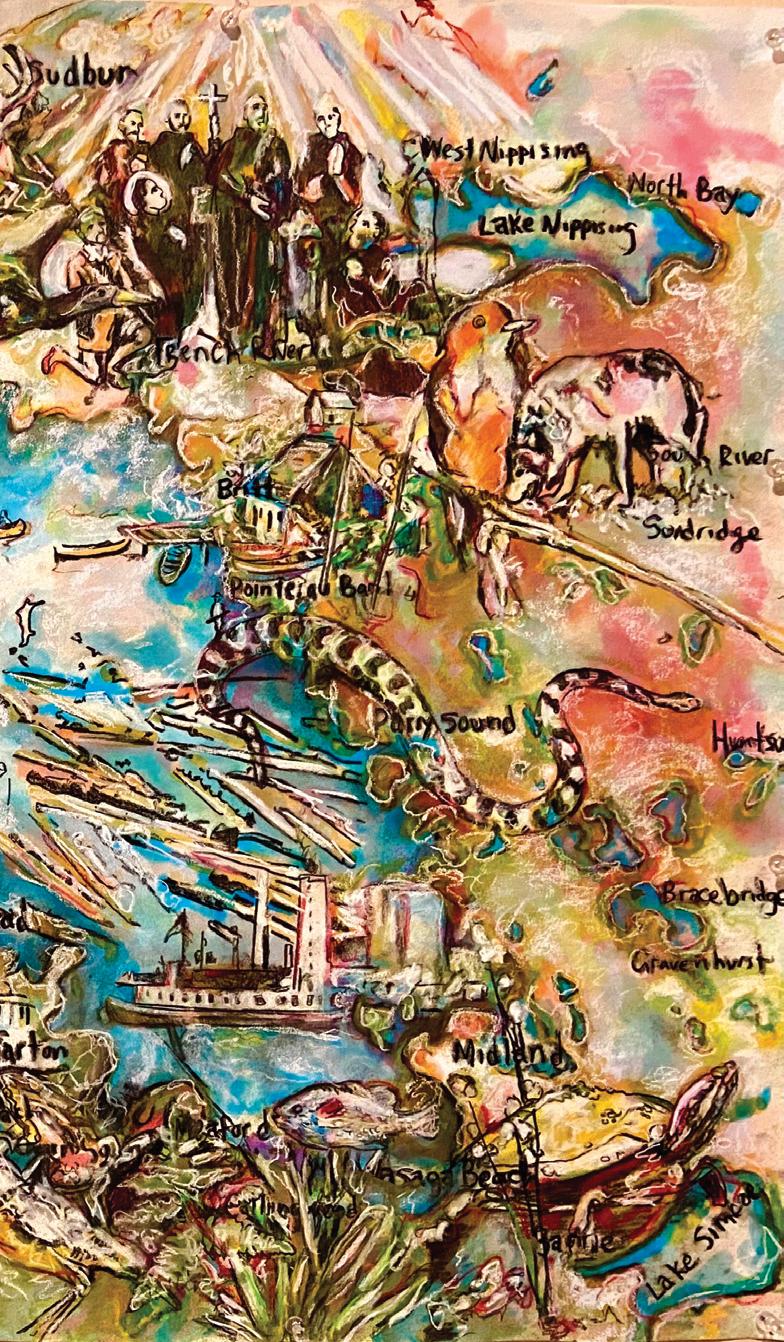

map depicting the settlement history and species at risk of the Georgian Bay watershed

michael fa rnan

michael fa rnan

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 8

:: deep roots

Michael Farnan is a multidisciplinary artist and educator, living and working in Victoria Harbour, Ontario. His current research focusses on mapping the settlement history and biosphere of his home community on Georgian Bay. www.michaelfarnan.ca

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 9

Michael Farnan. Georgian Bay Watershed and Species at Risk. 2022 Ink, chalk and charcoal on paper. 24 x 36"

Confluence

susan shantz

My recent art exhibition, Confluence, uses contemporary cartographic road maps as source material to search for an alternative, watershed map of the Saskatchewan River from source to delta and ocean across three prairie provinces.1 Using drawing, embroidery and large-scale cutwork tarps, I explored my river connection to the place where I live in Saskatoon which is divided and defined by water on the prairie. By tracing the currents of streams and rivers with ink, thread, paint and cut-outs, I followed meandering water lines that interrupt the boundaries of the regulated prairie grid, connecting my point on the river to humans and more-than-humans2 upstream and down.

What if my territory of belonging were defined by the course of water rather than land? Might I discover the point of view of a river with my pencil/pen/needle/knife? Draw, stitch and cut my way through the overlaid network of occupation to the find the undercurrents of water in the watershed territory I inhabit? Confluence contrasts the fragmentation and gridding of the prairie through surveying and mapping with the less visible path of water.

1 The Saskatchewan River delta, the largest inland delta in North America, spans the Saskatchewan-Manitoba border near Cumberland House, Saskatchewan connecting Treaty 5, 6 and 10 territories with many Cree and Metis inhabitants. It is considered the terminus of the Saskatchewan River watershed after which its waters become 15.4% of the water in the Nelson River which flows into Hudson's Bay.

https://www.hydro.mb.ca/assets/img/figurebox/dry-conditions-arent-only-factor-in-mh-water-supply-2.png

Accessed 21 Nov. 2022.

2 'more-than-human' – a term used in some academic disciplines to question the binary of human/nonhuman and culture/nature.

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 10

figure 1: Streams, rivers, lakes and delta marshland of the Saskatchewan watershed traced in blue ink from a cartographic source map. (figure 5) Water Basin II, coloured pen on paper; 45.7 x 31.8 x 3.2 cm (each panel), 2019

:: complex systems

Gabriela Garcia-Luna

I (Saskatchewan River), installation; 4 tarps, 359 x 1280 x 853 cm, 2018-2019

A watershed dream is shared by contemporary bioregionalists as well as the visionary nineteenth century head of the U.S. Geological Survey, John Wesley Powell, who, in 1890 proposed dividing the arid American west along twenty-three watershed boundaries.3 Now, in a time of climate crisis, this vision is needed to remind us of what has been lost even if it seems only a dream from an unrealized past. What might it mean to live with 'watershed mind'?4 To feel the connection between water in and outside our bodies, upstream and downstream from our point on a map? Might “watershed” itself be too static a term for something so fluid -- given water is an element that erodes edges and consists of multiple “nested and overlapping scales ranging from the interiority of individual bodies to the planetary hydrological cycle.”?5

3 Ross, John F. 'The Visionary John Wesley Powell Had a Plan for Developing the West, But Nobody Listened'. July 3, 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smithsonian-institution/visionary-johnwesley-powell-had-plan-developing-west-nobody-listened-180969182/ Accessed 8 Nov. 2022.

4 Peter Warshall used this term to describe the shift in thinking needed to better align ourselves with water. Warshall, Peter. 'Watershed Governance'. Writing on Water, edited by Rothenberg and Ulvaeus, MIT Press, 2001. p 47

5 Biro, Andrew. 'River-Adaptiveness in a Globalized World'. Thinking with Water, edited by Chen, MacLeod, and Neimanis, McGill-Queen’s UP, 2013. p 175

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 11

figure 2: Traced ink drawings from figure 3, upscaled to cover four tarps. The Saskatchewan Watershed --- streams, rivers, lakes and delta marshland – is cut into the tarps to create connected and gaping overhead basins and paths that cast shadow maps on the floor and walls. Water Basin

Gabriela Garcia-Luna

local topographic maps.

Confluence II (Bow/Oldman/Red Deer/Saskatchewan Rivers), bookwork; mixed media on pellon, 312.4 x 426.8 x 782.3 cm, 2020-2021

Confluence I (Bow/Oldman/Red Deer/Saskatchewan Rivers) bookwork; paper, thread, 188.0 x 24.1 x 7.6 cm, 2017

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 12

figure 3: River canoe route through the badlands traced from pages in a guide book then machine-sewn on paper and accordion-bound into an undulating, overlapping book that opens and spreads, wave-like, across a horizontal plain.

figure 4: The South Saskatchewan River carves its way through badlands seeking the lowest point of gravity; these water currents are represented by long strands of embroidery floss sewn in running stitches across eight panels enlarged from the pages of a book of

:: complex systems

all images this page: Gabriela Garcia-Luna

figure

River Wear (for managers), found objects, embroidery, 137.2 x 35.6 x 94.0 cm (each), 2018-2020

left: detail of River Wear (for managers: glacial source)

River Wear (for managers) with video projection of the artist’s hand embroidering the path of water across the prairie overlaid with the footage of the river’s changing water surface and sounds of geese in migration.

River Wear: Current, video (looped), 2:54 min, 2020 https://vimeo.com/768284162

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 13

5: Embroidered shirts for water managers with three key areas of the Saskatchewan watershed represented -- glacial streams, prairie meander and delta dispersion – all of which need care and attention in a changing climate.

all images this page: Gabriela Garcia-Luna

A number of pieces in Confluence began as small-scale tracings from conventional maps, as I sought the path of water, using pen, paint and thread. Scaled up, these became large installations: the blue ballpoint ink lines of water lines hidden amidst the roads and towns of three prairie highway maps were increased, inches to feet, and cut into azure-blue tarps hung overhead to cast shadow-maps below (figures 2 and 2a); the accordion-fold bookwork of the river meandering through the soft topography of badlands expanded to eight stitched fabric panels cascading down the wall of the gallery and across the floor (figures 3 and 4). In another series, I embroidered the path of water in three key watershed zones onto the back of white-collar shirts for water managers. If we wore the river, like a ritual garment connected physically and imaginatively to our bodies (figure 5), might we make different decisions about the upstream and downstream waters that connect us -- humans and more-than-human beings – in our watersheds?

After completing and exhibiting the Confluence installation, I returned to my map-source and, with white paint and a fine-pointed brush, covered over the grid-lines and dots of roads and towns to better see the connecting paths of rivers as well as the loose outline of the watershed that holds them. This hydrocommons, beneath the ghostmarks of civilisation (figure 6), is a threshold edge, opening to the white ground of the map itself and revealing a permeable space. Like the water’s shoreline on a river or lake, it is a more complex zone of transition than John Wesley Powell might have imagined with his demarcated governance boundaries.

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 14

figure 6: Redacted map of three prairie provinces with the connected dots and lines of roads and towns painted white to reveal the Saskatchewan River watershed from the Rocky Mountains to the Saskatchewan River Delta. Finding Watershed (redacted prairie maps), white paint on found paper maps, 129.0 x 89.0 cm (detail), 2022

:: complex systems

Susan Shantz

While mapping conventions were my starting point for the works in Confluence, my materials and methods upended those conventions and dissolved the smooth surface of the map into complex fragments. Those who entered the space of Confluence heard the babble of water6 as my multi-scaled, reconfigured maps expanded the parameters of mapping. From video and audio to embroidered shirts, to tarps and books, Confluence exhibits multi-sensory modes of knowing that come closer to the complexity of land over and under water; of water shifting land and land directing water. p

6 Cecelia Chen uses this term to describe the excess metaphorical 'noise' of water that may go beyond conventions of both mapping and knowing leading to experimental and diverse methods of representation. 'Mapping Waters: Thinking with Watery Places'. Thinking with Water, edited by Chen, MacLeod, and Neimanis, McGill-Queen’s UP, 2013. pp 278 – 298

Those who entered the space of Confluence literally heard the sound of water from three video/audio projections of freezing/melting ice/water from streams and rivers in the watershed.

Confluence was recently exhibited at the Moose Jaw Museum and Art Gallery, February 4-May 1, 2022.

Susan Shantz teaches studio art in the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Saskatchewan. Her multi-media artwork, Confluence, considers the Saskatchewan watershed and was informed by collaborating with environmental scientists.

https://www.susanshantz.com/confluence

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 15

figure 2a: Traced ink drawings based on figure 2, enlarged to fit on four tarps. Streams, rivers, lakes and delta marshland are cut into the tarps to create connected and gaping overhead basins and paths that cast shadow maps on the floor and walls. Water Basin I (Saskatchewan River), installation; 4 tarps, 359 x 1280 x 853 cm, 2018-2019

Gabriela Garcia-Luna

tracing carefull paths

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 16

michelle wilson

michelle wilson

:: complex systems

The Coves Collective. Tracing Csrefull Paths (work in progress), 2022-2023. 80cm x 70cm, linen and cotton fabric, merino wool thread, black raspberry, goldenrod and black walnut dyes, time and community.

My storytelling meanders, retraces itself, stays in place and excavates, changing slightly with every narration. These stories trace the contours of movement, for example, migration routes or rivers. And so, I use maps to guide their telling; maps that, like ‘land,’ are formed through relations. They are mnemonic devices that direct my wandering mind.

On this map, we, the Coves Collective, illustrate the land we traced with our bodies during walks and workshops and recorded with GPS apps (see the white-on-white stitches). We create images with threads stained and dyed with plants from this place. Soils with long memories nourished these plant beings. They remember the relationships that played out across their surfaces, the toxins that leached down or were born through groundwater, and the bullets and chemical tanks embedded in their depths.

This island of land, nestled in the crook of a horseshoe of muddy ponds, was formed millennia ago by a meander off the river known to its Anishinaabe stewards as the Deshkan Ziibi or Antler River.1 Settlers had yet to sever this meander from the Deshkan Ziibi when the Deshkan Ziibiing Anishinaabeg signed McKee Treaty No. 2 and London Township Treaty No. 6.2 As deceitful as those treaties were, one thing is clear: the Deshkan Ziibiing Anishinaabeg never ceded title to the bed of the Deshkan Ziibi.3

Following the ponds’ banks today, I have found that only one trickling finger stretches toward the Deshkan Ziibi. This is because the river inflow was blocked over a century ago by railway embankments and later, in the 1950s, by a garbage dump. Still, I understand this place, known as the Coves, as part of the watershed that the Deshkan Ziibiing Anishinaabeg nation never ceded. But what does ownership mean when we understand that this area also falls under the inherent Indigenous rights of the Minisink Lunaape (Munsee-Delaware Nation) and the Onyota’a:ka (Oneida Nation of the Thames)? The waters that wore away the banks that define and protect this place also mark it as a place where I can feel what should be palpable throughout this town, province, and country; I am on Stolen Indigenous Land.

So, who does this land belong to?

1 Later the French called it La Tranchée. Most recently, LieutenantGovernor John Graves Simcoe called it the Thames River.

2 The Deshkan Ziibiing Anishinaabeg are commonly referred to today as the Chippewa of the Thames First Nation.

3 This is a brief and simplified interpretation of the treaty relationships in London, Ontario. For a thorough and more nuanced understanding I urge you to read "London (Ontario) Area Treaties: An Introductory Guide" (2018) by Stephen D'Arcy. It is available at: http://works.bepress.com/sdarcy/19/

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 17

This answer, again, returns us to the river. In 1937 the Deshkan Zibii crested its banks and swamped much of the city of London, Ontario. In response, the city instituted flood control measures that arrested the seasonal submerging of the lowlands held within the oxbow. Thus, on the eve of the Second World War, the Canadian government offered up this land, which they had used for nearly sixty years as a rifle range and training ground for agriculture.

Simultaneously, the advancing tide of German expansion drove the Wolf family from what was then Czechoslovakia. In 1939 Thomas Wolf purchased nearly all the land we have mapped in this piece. He planted a fruit orchard, built a house, and quietly continued his family trade in the basement, mixing paint.

Within a decade, Thomas Wolf and his family established the Almatex Paint company. It expanded quickly, and before anyone could raise alarms about the environmental impact, it became a significant employer in the city. The factory closed in 2001. Its warehouses, laboratory, and factory are gone. However, the chain link fences topped with barbed wire, cement pads, and blocks of concrete threaded with rebar remain, marking where the toxic chemicals were once mixed. This summer, I led walks through a hole in the fence to this site. We poured water gathered from the ponds onto a living artwork: a ring of goldenrod planted by the Coves Collective into a trench we cut into the cement with a circular saw. This goldenrod removes lead in the soil, one of the many invisible presences Almatex left behind. In the center of the ring, we marked our presence by stacking rocks and chunks of concrete to form a cairn. In August, the former factory site is similarly ringed with four-foot-high goldenrod, nourishing swarms of bees, vibrantly declaring that these plant beings are already working to heal this place. The Coves Collective's work humbly draws attention to what these plant beings have already begun.

I told those who accompanied me on my walks about Mrs. Ayshi Hassan, who wrote to the city in 1971 and informed them that all the birds had left the area, driven away by the stench of noxious fumes. I told them about the "paint pit" that children set on fire in 1966, creating a column of smoke that rose hundreds of feet above the land we stood on. I told them about the two towering evergreens that were felled in 1981 when a labour strike turned violent; the Almatex management replaced the trees with a giant pole topped with a CCTV camera. One day as I was telling these stories, two deer raced around the interior perimeter of the fence, circling us before escaping through a gap known only to them. One of the youths with me that day asked, “what is the opposite of traumatized?”

Valspar, a subsidiary of Sherwin Williams, who bought out Almatex, still owns this land. Their contractors only visit the site to test the groundwater through blue test wells that dot the land.

But does the land belong to them?

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 18

:: complex systems

michelle wilson

We walked the trails made by humans and animals and picked up the small apples that still grow yearly. I heard that decades ago, the caretaker shot salt pellets at the children sneaking into the orchard to eat the fruit. There we found half a ginger cat, consumed by the resident coyotes. A child left behind tobacco and the whispered words, 'rest in peace'.

As recently as the 1920s and 30s, the ponds that circle this land still flowed with water from the Deshkan Ziibi. They were so clear and clean that settlers set up ice-harvesting businesses on their banks. Now the only water that flows into them is runoff from streets and neighbourhoods. This has kicked the natural sedimentation process into overdrive. The water has become nearly opaque in places. In the spring of 1970, almost all the fish in the East Pond died. Today there are thriving populations of turtles and Common Carp. The carp, a non-native giant in these small waterways, stir up the silt, keeping sunlight from penetrating these waters and keeping aquatic vegetation from taking root. These carp are too big to be prey for the herons and egrets who have returned to nest on these banks. So, as the Coves Collective, we have tried to establish better relations with this place by harvesting carp. We honour their lives by eating their flesh (when it is safe) and tanning their hides (which will eventually be incorporated into this map).

We do this work because we attend to this place; as we walk here, harvest clay and plants here, and attempt to enter into reciprocal relations here. Not because this place belongs to us but rather because we, the Indigenous and non-Indigenous members of the Coves Collective, are in the process of belonging to this place. p

The Coves Collective is an ad-hoc group of artists, educators, and activists that have come together to attend to our responsibilities and relationships with the Coves, an environmentally significant area recovering from years of misuse. These actions include Tracing CareFull Paths, a communityproduced textile map facilitated by Michelle Wilson and Reilly Knowles, on the land teachings, including traditional medicine gathering and medicine pouch making led by cultural-justice coordinator Candace Dube, and clay harvesting and vessel making guided by Indigenous ceramicist Shawna Redskye.

Michelle Wilson is an artist and mother currently residing as an uninvited guest on Treaty Six territory in London, Ontario. She earned a PhD in Art and Visual Culture from the University of Western Ontario and is currently a post-doctoral scholar with the Conservation Through Reconciliation Partnership at the University of Guelph. www.michelle-wilson.ca

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 19

michelle wilson

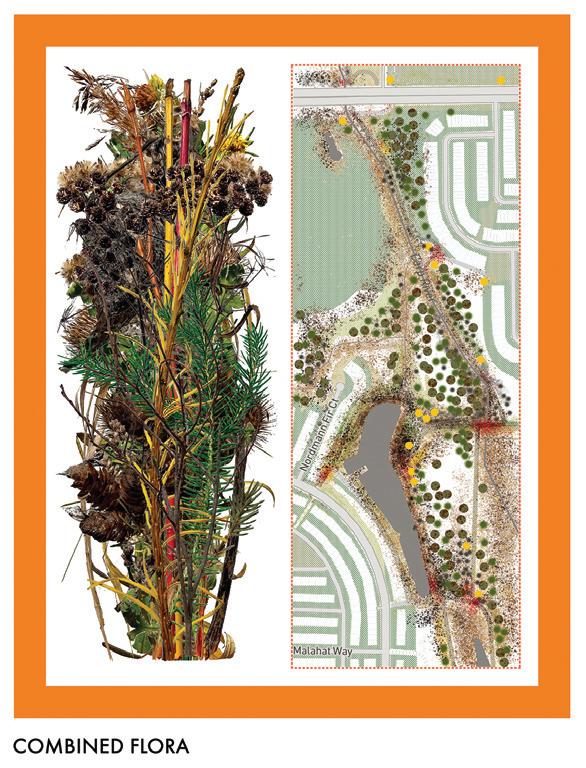

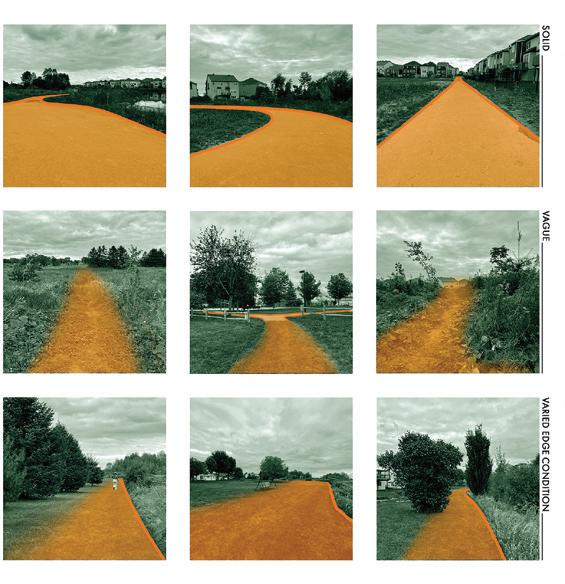

the moral implications of urban design in proximity to wildlife

yana kigel

yana kigel

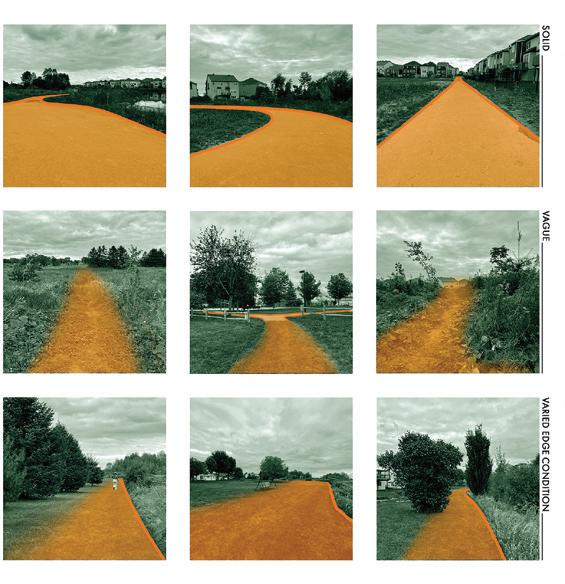

A small pond, a distributary of the Carp River and located within the developing Ottawa suburb of Stittsville sits in what was once an undeveloped buffer zone, separating an established neighbourhood from agricultural land. Recently, the urban sprawl encircling this piece of land has encroached on the undergrowth with the freshly laid-out trail of Abbottsville, a paved addition that overshadows the many organic paths large and small, just as the unnamed pond is dwarfed by the well-known Carp River.

I live in this relatively new neighbourhood. With windows overlooking these pathways, I have had a front-row seat to the intrusive construction that has appeared over the last three years. Suburbanites often rationalise their relocation by denouncing the lack of greenery in the city centre; hence, moving from a busy metropolis to a quiet suburb, I also envisioned the promised closeness to nature. However, upon moving, I began to see that the green suburbs had failed to create a place of harmony with nature. Instead, the streets, victims of land manipulation, were deceptively moulded to appear ‘green’. Traditional suburban landscape works to sterilise natural landscapes rather than promote an ecosystem that connects humans and wildlife. The remaining patches of forest lands are isolated in the existing urban fabric. Wilderness is expelled from our daily routine, visited only through planned excursions.

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 20

:: complex systems

Yana Kigel

what defines a path?

Environment and intent influence how we subconsciously pick which trail is worth travelling along. In small-scale urban parks, designers typically attempt to navigate the traffic by accentuating an abrupt change in materiality along the boundaries - pavement against earth, manicured turf against overgrown plants, the purpose being to make it accessible both visually and physically. As a result, most people stay on the pavement, avoiding extensions that appear uncharted or unstable. These more ambiguous, organic trails are hence less inviting. They have a smaller footprint, a less visible border, and subtle material transition. Only in a less controlled environment, such as a forest, could such pathways be expected to deviate from the established routes. We recognise that we may encounter the unknown - a wild animal, an unexpected puddle, or a dead end. Another alternative, increasingly challenging to locate, is a route that hugs an edge. An existing border, such as of backyards, agricultural fields, or rivers, define these types of boundaries. Unlike spread asphalt or prints left by previous visitors, it is far more challenging to determine if an edge may be intended for travel or if it is part of an off-limits, private property.

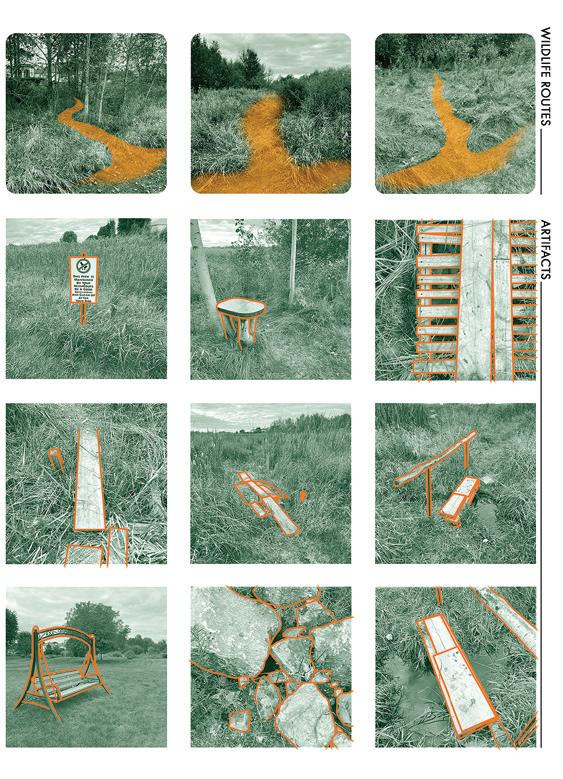

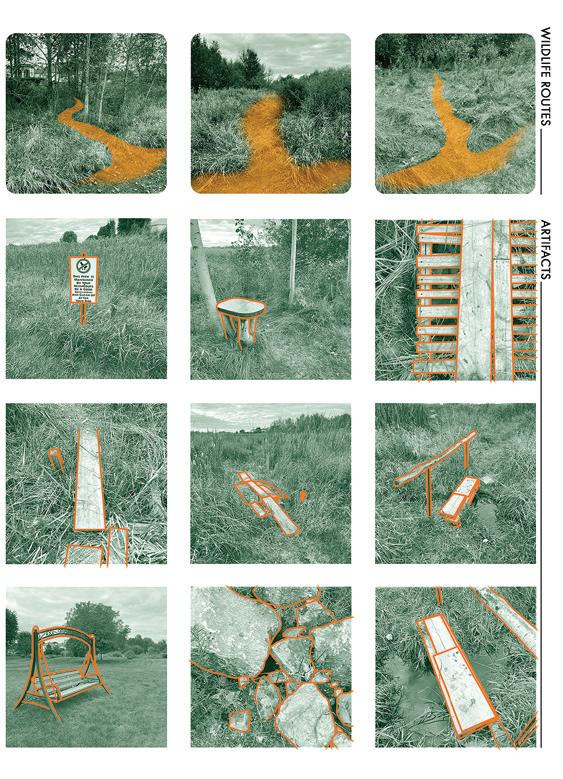

In our still semi-underdeveloped site, the Abbotsville trail, the only paved path constructed by the urban planners, is popular among the residents of the streets whose properties border it. The rest of the informal paths are on terrain of natural rocky surfaces, flooding gaps and artificial scrap bridges, all of which are difficult to use. The few paths made by animals are too narrow for human use and typically disappear into dense vegetation. They too are difficult to follow and are rarely explored. The only traces of human activity are artefacts left behind on these overlooked paths, such as a brought-in swing, a worn-out chair, or gardening equipment. With such secrecy and enigma, these routes are held sacred by their select users. Their unpredictability, emptiness and seasonal changes make them feel as though they are constantly ‘discovered’.

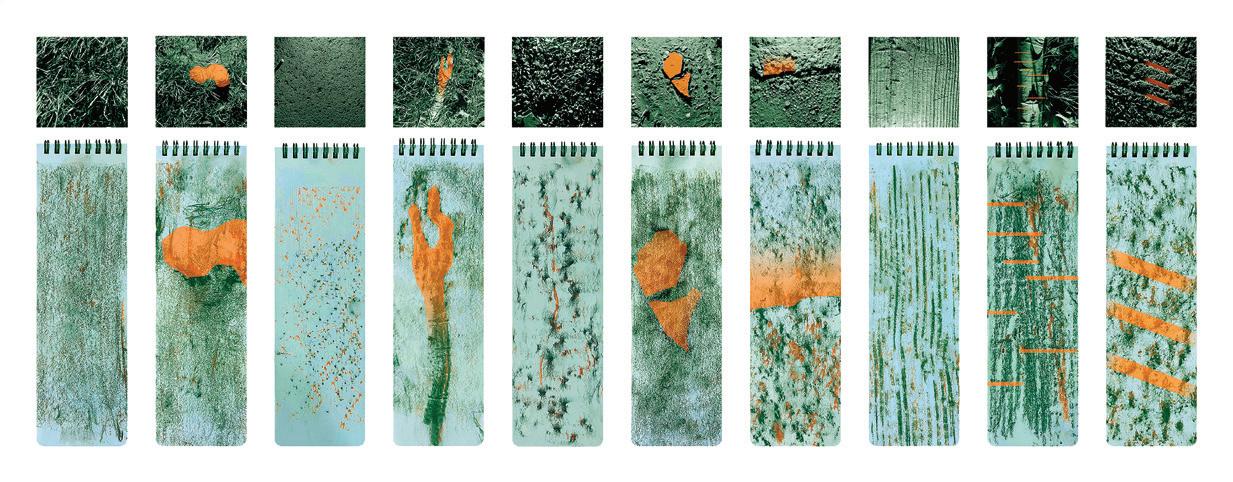

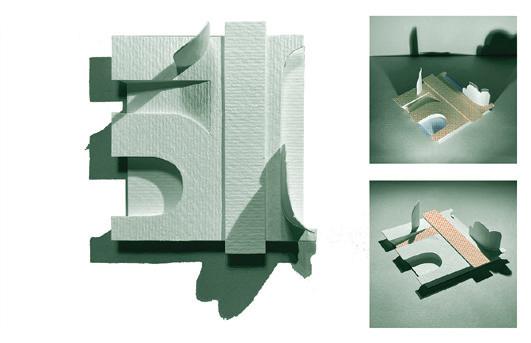

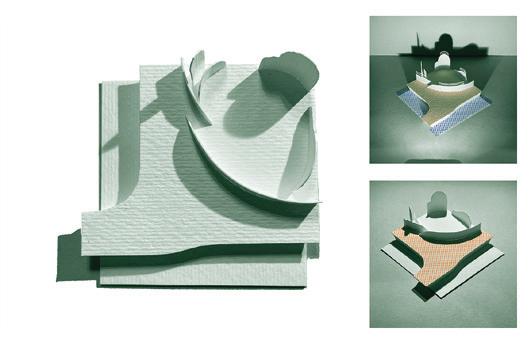

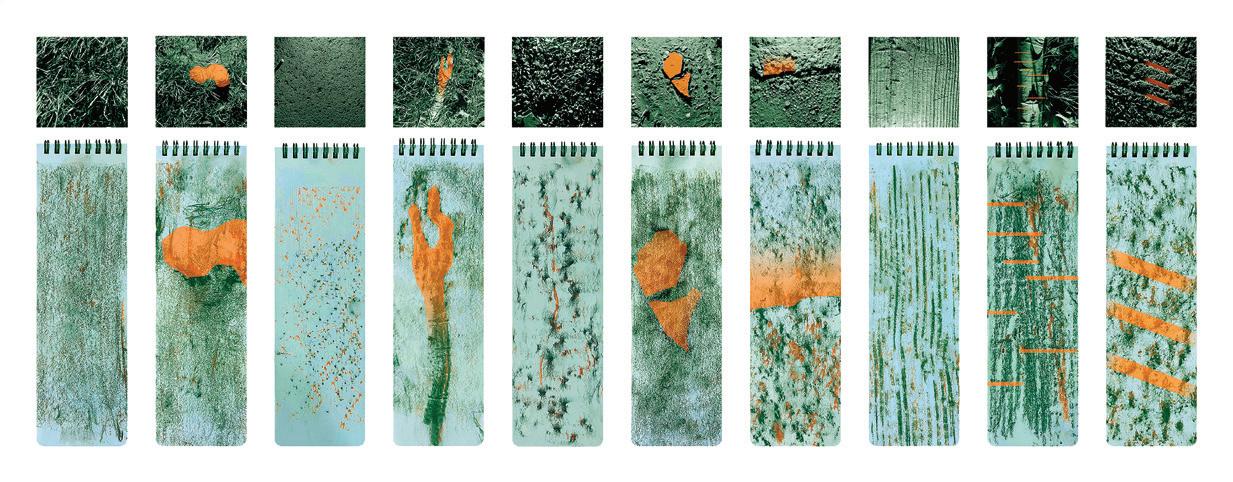

This series of photographs was the initial step in documenting the site spatially; it intended to exhibit the trails in a way that offered an environmental backdrop while marking the segment's start and finish through an orange overlay.

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 21

Yana Kigel

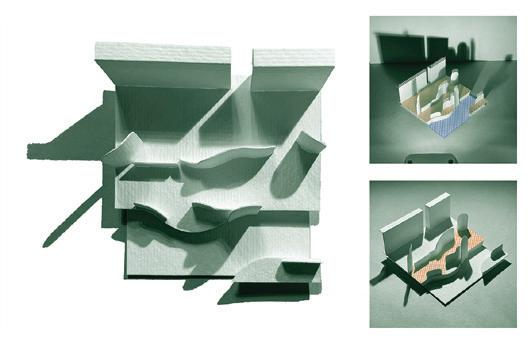

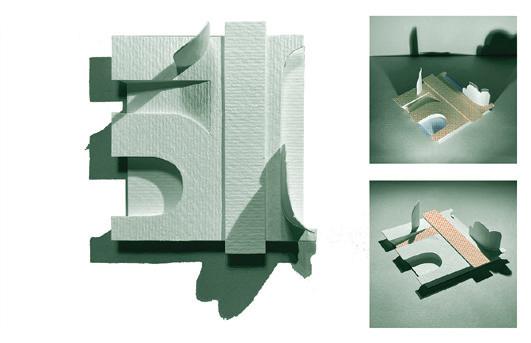

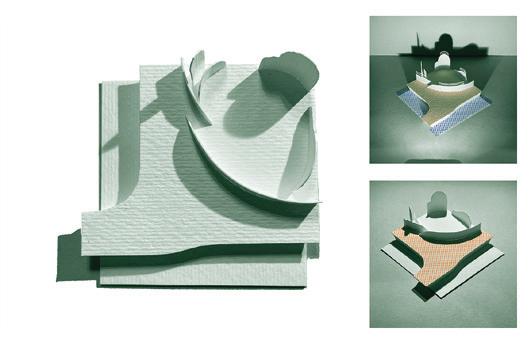

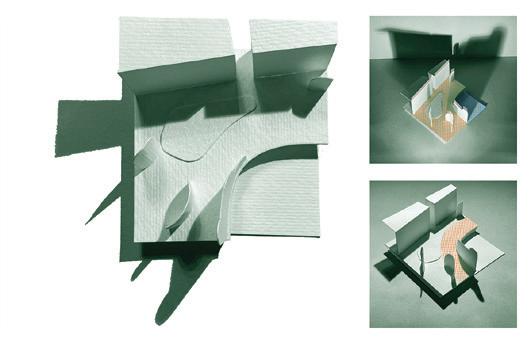

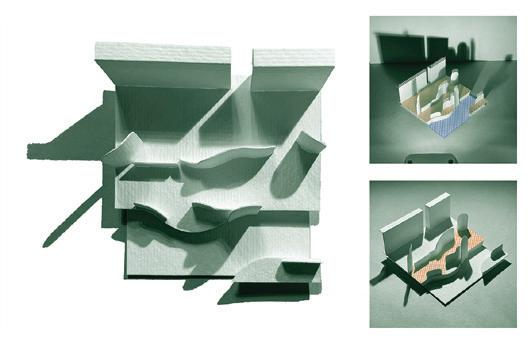

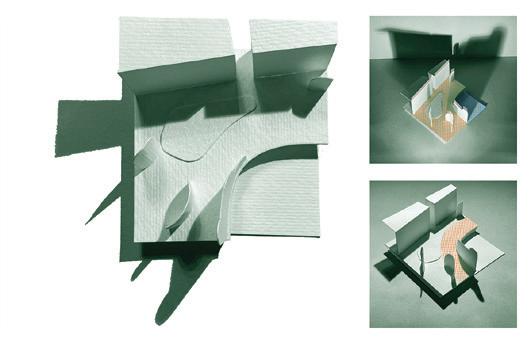

simplify: strip the context

Unsurprisingly, the previous ways of analysis were carried out from a human perspective. The fundamental problem of dissecting a path through photographs of edge states was its overflowing context. Though natural tracks were walked on less frequently than paved ones, traffic's visual contours made them easy to detect. Crucially, breaking free from an analytic human perspective, new paths may be found, or in this case, missed. We built models to reduce and abstract the volume of visual data found on any path. With decreased information, pathways can only be speculated. Paths that are visually obvious become illegible. It was now easy to imagine how an animal, unaware of human courses, might see the area. For aquatic species, it was the waterways that were the primary means of transportation. Land animals used a variety of terrain for travelling, seeing only the water and structures as constraints. Birds used landmarks such as the tops of trees and higher edges of buildings for their orientation. It is fascinating, especially in contrast to humans, how little importance fauna places on sticking to the beaten path.

The fundamental problem with photographic analysis, conducted from a human standpoint, as is customary, is a site's overflowing context.

Breaking this custom by separating oneself was important to gain a new perspective. As a means of documentation, model building decreased the amount of visual data and broadened the perception of the research. The focus has shifted from an individual to a more extensive range of site users. Five paper models each portray a separate area of the routes. Now, with reduced information, the pathways could only be guessed at. Paths that once had clear indicators are now completely incomprehensible.

Context is absent from the initial models. The addition of color accentuates the ground, water, and treetops, all used by varied forms of fauna, disregarding any solid route. The previously documented but now concealed manmade route is finally exposed.

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 22

:: complex systems

Yana Kigel

accentuate: select the context

This fascination led me to explore a different technique that did the opposite of selective omission, which removed textural context and what geometry defines a path. I made a more tactile record, focusing on the surfaces of the trails, and found that one may overcome the need for visual cues and instead follow the path from touch alone – scenery or destination hardly matters compared to the sensation of walking and the feeling of the ground beneath. Organic routes awaken the sense of touch; we become aware of where we step, how we step, and what we step over. We begin to feel more present. The constant variations allow us to appreciate the ground truthfully. A lack of textural variation makes the walking experience less personal and intimate:

Hard, then softer. Wet. A crawling bug? Squished again. Poking root! Paw prints.

The pavement..

It is just hard, then still hard, and hard once again.

It's a shame that natural paths aren't frequently considered throughout the planning phase of parks. To find these, we must go out of our way and visit still-untouched sites or organise a trip to the woods, where the requirement to plan an event takes away any genuine spontaneity. Synthetic walkways are designed to be trusted and so are unnoticed in the process of walking. Our sense of touch is diminished, the environment is sterile, we start to dissociate from nature as the experience becomes artificial. The bleakness of so many modern urban parks suppresses so many of the sensations that make us human. This pushes a human disconnect from wildlife, expelling them from their natural habitats and keeping them from thriving in newly designed ones.

The frottage method captures the ground's texture, first with stiff graphite, followed by softer, warmer-toned chalk, picking up the most prominent elevations. Following the flat representation on paper, clay impressions were taken to preserve the threedimensionality of the different surfaces.

This 'roughness' analysis sheds light on potential preferences among path visitors. Solid and uniform surfaces attracted older residents and children, as well as turtles and larger fowl. Young adults, dog walkers, larger mammals, and rodents, however, preferred the more irregular surfaces.

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 23

Similarly to selective omission, an inverted method was used to study the segments.

Yana Kigel

determine the focus

Where does this shift in focus from over-designed human ways to ones of wildlife and their organic route-making practices take us? On my study site, I want to preserve a fragment of animal migration corridors before the expansion of human settlement fully eradicates it. My site visits eventually became routine without thought or preparation, promoting detours and a desire to explore. I no longer made it a mission to travel from point A to B, but rather, I began following the sounds of birds, the scents of plants and the movements of weasels.

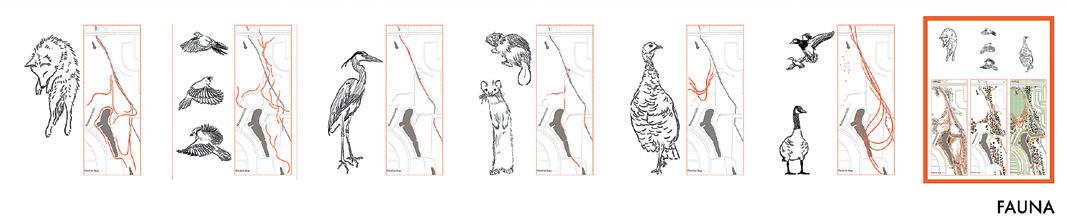

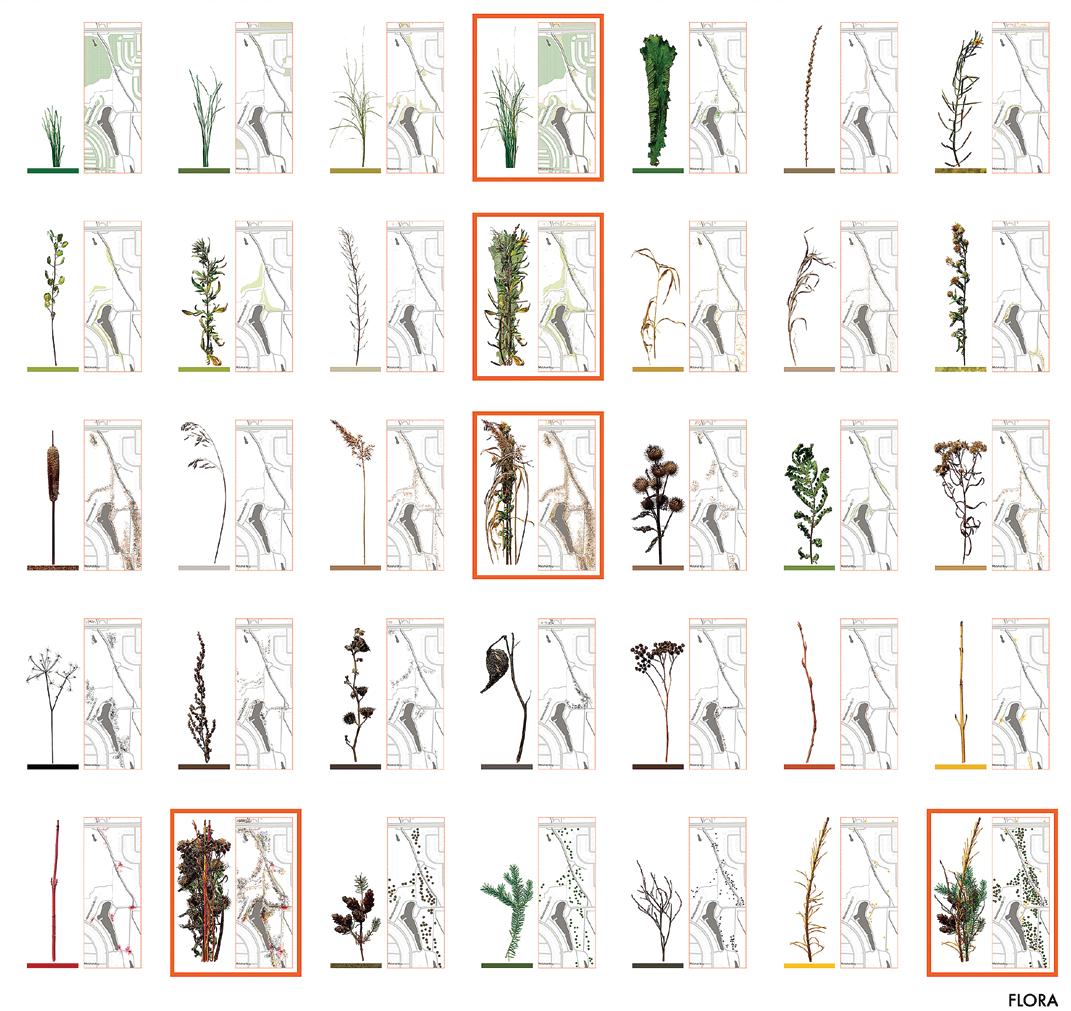

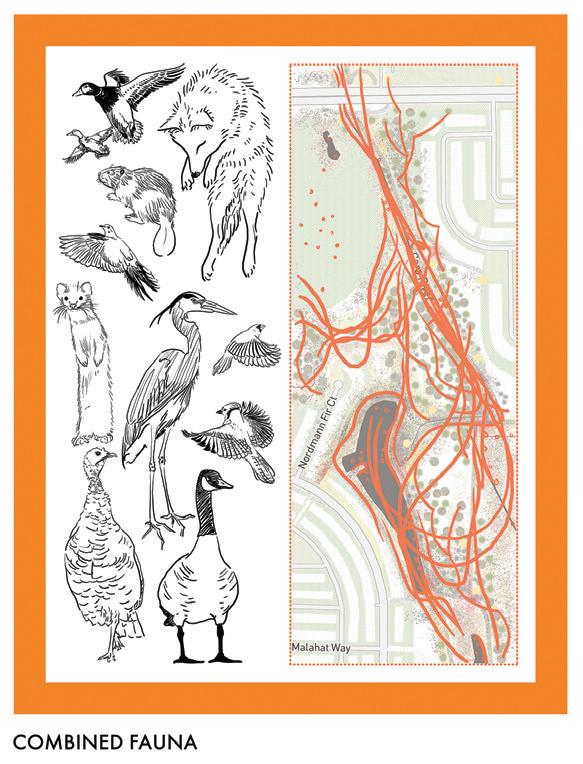

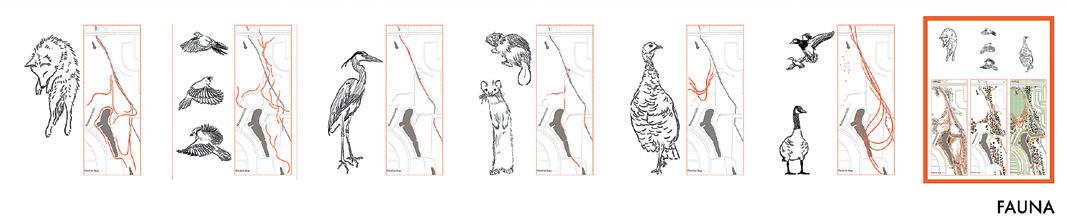

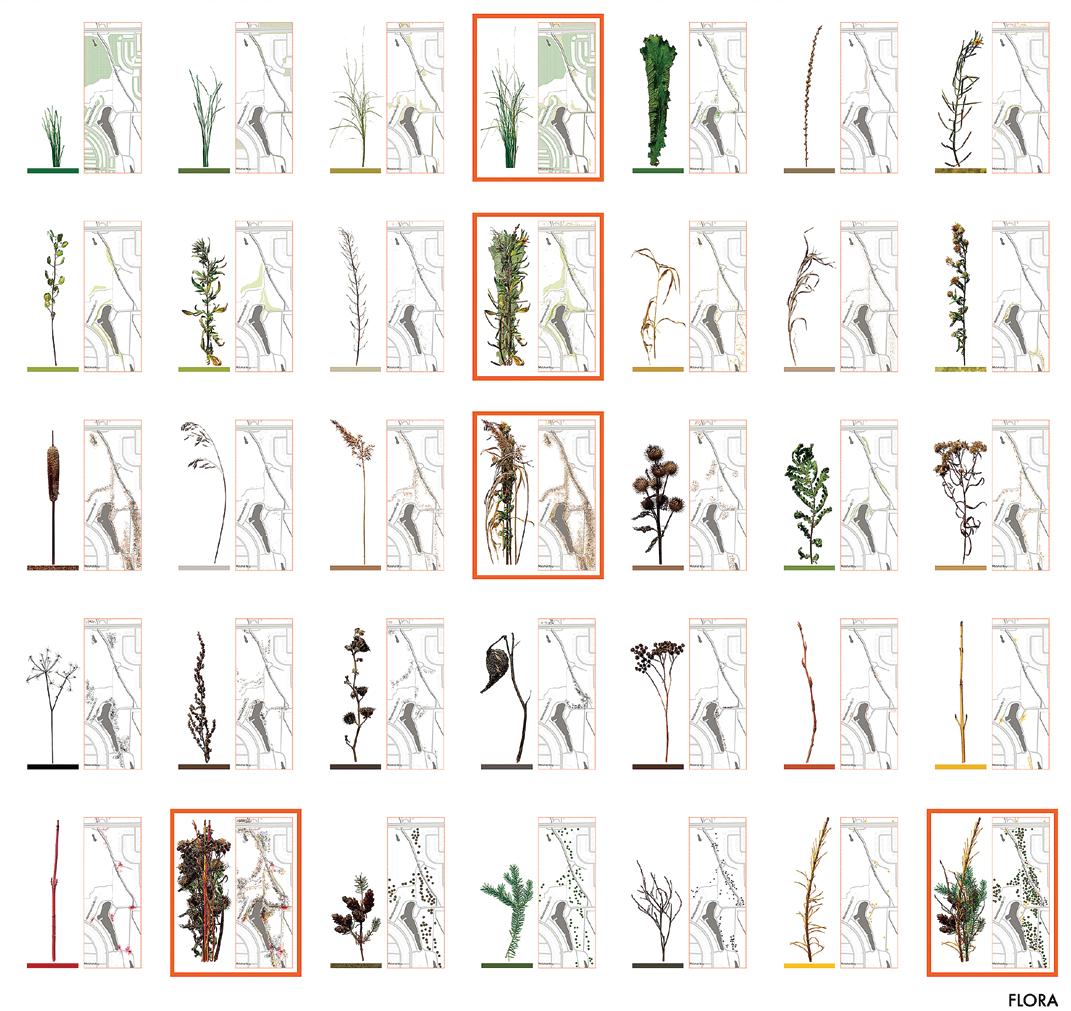

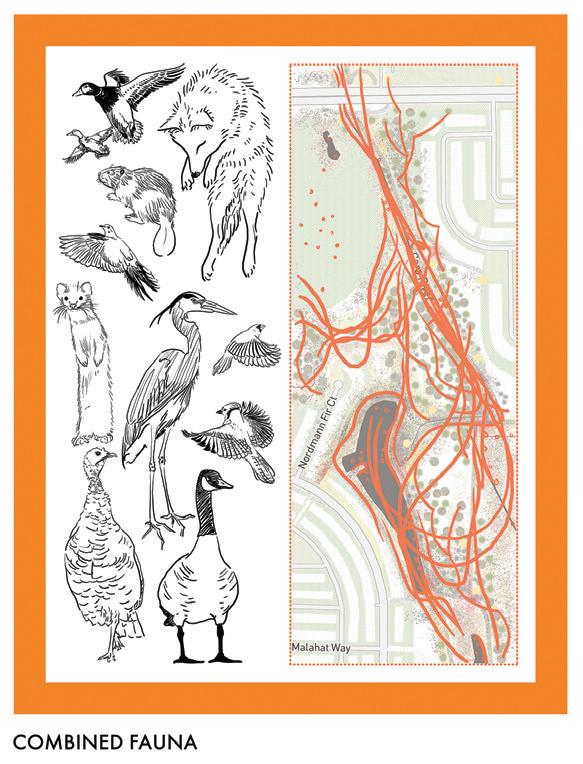

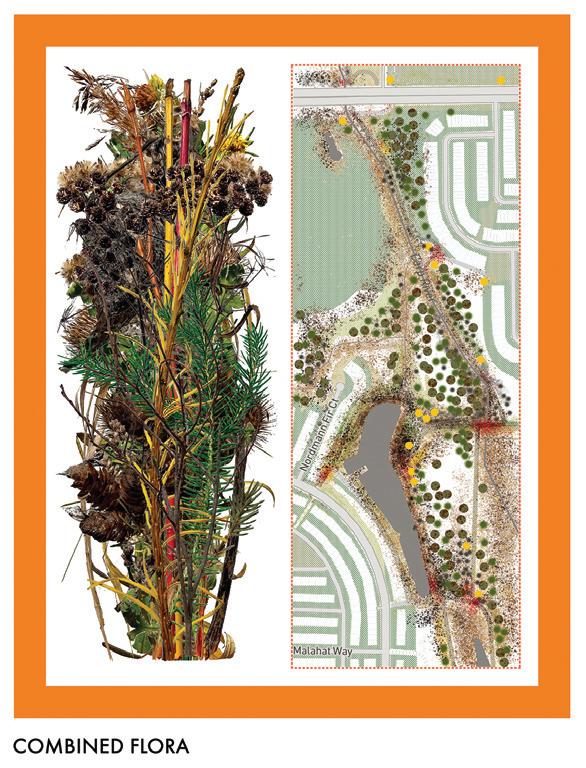

Here the focus shifts from human observation to wildlife and its organic route-making practices. The site's flora: short grasses, weeds, shrubbery, and trees. The fauna: several animals on site. Maps chart their rough trajectories throughout a three-year period.

Animal migration routes and their overlaps were revealed. Rodents like crevices and dense shrubbery, while coyotes follow cleared-out ways. Turkeys prefer the transition zone between open grasslands and densely forested areas, and songbirds mostly fly between treetops. Herons, beavers, weasels and ducks share the overgrown streams. Geese congregate in open areas near bodies of water and pastures. This more profound comprehension of animal preferences was possible only once I eliminated my preconceptions about what constituted a route. Without this, I would have stayed oblivious to their habits. So how can we, architects, urban planners and designers, continue to claim that we care to build with nature in mind when we actively work on segregating it through construction, sterilisation, and demolition?

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 24

:: complex systems

Yana Kigel

the Abbottsville Trail and its sacred extensions

Site analysis is a crucial first step in architectural and urban planning before any design process begins. A study may be carried out in various ways, typically with a particular objective in mind; it is rare for the aim to be uncertain or absent. This research began with neither a framework nor an end in sight but merely with a personal interest in trail usage and prior familiarity with the region's volatile wildlife population.

It proceeded with a lack of specificity, exploring new approaches to understanding and interpreting a site. It established relationships between path-making, humans, fauna, flora and the ground itself. Although the Abbottsville Trail analysis did not lead to a design proposal, the knowledge acquired from this work was reapplied to my thesis, A Golden Green Belt: Integrating Nature in Ottawa's Next Suburbs

Experimental and intensive site analysis techniques enabled the thesis to strive for a more dynamic and environmentally friendly neighbourhood layout, encouraging future projects to invest more thoroughly in the design research stage. p

Yana Kigel has completed her undergraduate and graduate degrees in the architecture program at Carleton University and is presently working at Carleton Immersive Media Studio. The topic of this text expanded into her thesis.

https://curve.carleton.ca/f0f21af2-a73f-4bb4-bec9-ee5260822733

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 25

Yana Kigel

drawing water from Aridlands

dalia munenzon

On America's Great Plains, water in all states of wetness shapes both landscape and subterranean strata, bonding and holding down soil and flora. West of the 100th meridian, surface water is limited and annual precipitation on the plains is below 20 inches/ 50cm a year. As groundwater from aquifers is the primary source of life for any territory at the centre of agricultural production, the depletion of the Ogallala – the High Plains Aquifer – through hotter, drier and more unpredictable weather, jeopardises local ecosystems and communities. This invisible relationship between extraction, production, and the flow of natural resources is key to understanding future risks and opportunities for adaptation. Watershed-based readings of the landscape make these processes visible.

t he High Plains Aquifer

Water from the saturated limestone sponge, the geological terminology for the aquifer, contributes to the annual production of $35 billion worth of crops, a quarter of national crop production. This remnant of an ancient ocean stretches from Texas to South Dakota and provides water to 112 million acres/4.6 million ha of farmland and grazing. Despite being deep underground, stationary groundwater and moving surface water are fundamentally intertwined as the aquifer discharges into streams and rivers. A decline in the aquifer's water level directly affects local streams that are drying at the rate of 6 miles per year.1

Pumping for agriculture, industry, and residential use from the High Plains Aquifer started in the early 1900s, accelerating in the mid-century with technological developments in gas pumps. Since the 1950s, high-volume pumping has led to a water level drop of 325 billion gallons every year, between 9% and 30% of its volume, and is projected to lose 40% by 2070. With 90% of the water drawn being used for agriculture, the sustainability of long-term use is rooted in regional water management and use policies.

re ading the landscape

In 1878, the geologist John Wesley Powell released his study on the farming and settlement capacity of territories west of the 100th meridian. In 'On the Arid Lands of the Western United States'2 he stated that there is insufficient surface water or precipitation to sustain European farming practices and that any farming will require irrigation. He proposed managing and dividing the territory based on watersheds, creating administrative structures based on the natural formation of the landscape to allow rational water distribution. His proposal was rejected. However, the projected climate changes and the rapid depletion of the High Plains Aquifer points to a concept worth revisiting.

cross-boundary recharging

The composition of sand and gravel in the High Plains Aquifer makes recharging complex and lengthy. Climate variability across the Great Plains, land cover changes and rate of water seepage result in recharge rates ranging from less than 1mm/year in parts of Texas to more than 150mm/year in the Nebraska Sandhills. This implies that the aquifer will take 6,000 years to recharge fully.

1 Ralls, Eric. 'The High Plains Aquifer Is in Danger of Drying Up' Earth.com, 15 Nov. 2017, https://www.earth.com/news/high-plains-aquifer-drying/.

2 Powell John Wesley et al. Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States : With a More Detailed Account of the Lands of Utah. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press 1962.

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 26

:: complex systems

Each of the states across the HPA has different regulations for groundwater and surface water use. Some states view surface water as a public resource and groundwater as private property. There is an understanding between the neighboring state of shared ownership and responsibility over surface water resources. However, when one state is geographically located at the top of a watershed, its water use might dramatically reduce the access for the state at the lower basin of that river. Therefore, agreements are used to ensure the fair use of water between these states.

In an ironic twist, agreements are met by seeping HPA groundwater from one state and pumping it into river tributaries in another state. For example, Nebraska's

Cooperative Republican Platte Enhancement project involves purchasing retired farms and installing highcapacity wells to pump water from the HPA and pipe it to Medicine Creek.3 Despite regulations and policies that usually make a distinction between surface water and groundwater, this process causes an absurd situation in which a manufactured process increases the flow between the two – therefore introducing groundwater back into the 'regulatory' commons.

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 27

3 N-CORPE. (n.d.). N-CORPE, the Nebraska Cooperative Republican Platte Enhancement project. N-CORPE. Retrieved December 19, 2022, from https://www.ncorpe.org/

Dalia Munenzon

the commons as a commodity

Reducing the amount of water extracted for irrigation is connected to state and federal law, water rights, tax incentives, insurance mechanisms, and crop needs. Each state among the eight sharing the aquifer has rules and frameworks that allow (and unintentionally encourage) depletion. Water rights across each state both enable and limit use and distribution in various ways according to the flexibly defined 'beneficial use'.

In Nebraska, surface and groundwater are subject to public management and oversight. Groundwater is subjected to Correlative Water Rights, and Water First-inTime Rule limits surface water. An annual water assessment study evaluates comprehensive water conditions - ground and surface - per watershed. Kansas holds the jurisdiction of all water rights in its territory and allocates permits for use. In Oklahoma, groundwater use permits are issued per the land acreage held.

Texas differentiates between ground and surface water through rights given to landowners. Surface water is owned by the state and allocated by permits. According to the Rule of Capture, groundwater belongs entirely to the landowner overlying it - sometimes called the 'law of the biggest pump'– in a shared aquifer, over-pumping one property can impact neighbouring wells.

crops and stewardship

The Great Plains region has a strong connection to water and oil extraction. Post-WW2 industrialisation led to the development of technologies for these extractions, illustrated in the maps. They show the site, county, and extraction section on a large scale. The reliance on oil prices in agricultural production requires farmers to develop strategies for reducing their water demand when oil prices rise.

The crop type grown and how it is cultivated affects water demand. In the past, rising oil prices motivated farmers to explore new crops and diversify by combining perennial grasses to steer away from monocultures. Indigenous landscape management strategies and the integration of crops and livestock are rooted in the relationship between flora species and their support systems. Now, with the aquifer depletion, these practices should be re-examined. The main crops grown in each state are different in their water demand. From the 'thirsty' corn in Nebraska, consuming 22 to 30 inches of water per acre, cotton in Texas requiring 12 to 24 inches of water per acre, to grains such as sorghum, which only requires 15.5 inches of water per acre. As aquifer levels drop and droughts become more frequent, farmers adapt by reducing consumption and switching to drought-tolerant crops. Kansas farmers have reduced water consumption by a quarter without sacrificing profits, while West Texans are

transitioning from water-intensive to drought-tolerant crops and grazing. Ultimately, decisions regarding planting and management are based on acreage and well capacity. Thus, removing the misguided notion of water abundance strengthens our understanding of ecological systems and relationships. And a closer relationship between the farmer, the soil, and the occupiers of his property.

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 28

:: complex systems

Har vesting rainfall is becoming increasingly necessary in areas where recharge is nearly impossible and the water table is shallow. To effectively manage this deluge, it is essential to consider topography, large-scale watershed systems, and minor historical traces of water flow, such as draws. This vision requires collaborative management of resources between neighbours at a scale beyond just a single property. Reading the High Plains Aquifer environment through a watershed-geological lens is only complete by considering the final component of precipitation. p

Dalia Munenzon is an assistant professor of urban design in sustainable communities and infrastructure at the University of Houston Gerald D Hines College of Architecture and Design. www.daliamunenzon.com

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 29

mapped by poetry

THE TROUBLES JOHN BARTON

until what centres no longer holds us, we compose pictures along the Falls Road, our car stopped shoppers window-gazing and unaware of the feints of shadow and light we insinuate among pyramids of fruit or trail across headlines in the newsstand tabloids as we jump quickly in and out, frame time with our viewfinders, the countless murals we snap drafted by sympathizers on the long overexposed exterior walls of the steep-roofed, red-brick, soot tarred houses, grocers, haberdashers, and hardware shops, murals about strikers who, two decades ago in Armagh, starved to death by choice, the English prison not far from the seat of my mother’s family who left the North years before the Famine, later Loyalists settled in Upper Canada west of Kingston the first house standing still in the plentiful winds gusting over the lake and Amherst Island, its crawl space scooped from shale damp with the panic felt hiding with the family silver carried with care all the way from Markethill, Johnson’s Yankee gang of sympathizers tacking across water, staging raids during what at school we labelled the Rebellion the unsettling climates trailed behind my ancestors becalmed into what is now a quaint four-poster bed and-breakfast where I would’ve taken you, another adventure in the Boys’ Own story of Ireland we had hoped one day to expatriate, the history of two men who through their troubles unite as one, despite what might hold them apart, checkpoints and pipe bombs this uncentred and sudden widening maze of streets turning us away from where we thought to go, visiting from elsewhere, driven by a friend who has lost any faith she knows where to take us so keeps us lost, hers an entire life of roadblocks and Guinness, having learned she is who she is where she is – the best and the worst – and, hoping to drive us clear of danger, turns us into the centre of a riot, the car dividing perspectives while rocks

skid across a fragmenting windscreen, this woman at the wheel living in an eternal present that is not Belfast, her vision of this intensely passionate city a long-fallen capital where, despite every wrong turn, couples meet and love, where despite herself she drops us off so we can shoot murals to the dead mothers and their missed children – they shame her far more than they trouble us – these commissioned vigilante works of art vitalizing the Easter Rising and Civil War two storeys high in green and orange or blacks and sombre greys in contrast to the coat of arms painted by paramilitaries at every corner of the Shankhill Road, the Red Hand of Ulster held religiously palm-flat and forwards, complex URLs of the UDA, the UUF, the UVF, and the UYM blazoned in scrolls beneath crossed machine guns and mute black-masked men who through torn slits look at us while we block our shots, you filling up your throwaway until it consumes itself, my hands shaking, my Minolta unable to track however few exposures my film still can make accommodations for, both of us cropping similar photos of the same wayside towns as we are later driven cross-country on the grand tour, sheep-crazed and whiskey-wise the kamikaze switchback roads along the jagged coastline turning and turning us into unexpected vistas, promontories sharpening against the azure our separate records overlapping, as if something untoward will drive us apart, a gesture or veering look at a stranger, cognizant already of the troubles we might import and give anxious voice to at home love’s terrorism, his sweet erasure so annihilating it undoes the existence first of one of us and then the other, the briefest of excursions across the most faint of lines there is never any coming back from the Republic a haven where the North goes to relax the air on either side of the border acrid with turf smoldering as it has for centuries in village hearths

Polari, We Are

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 30

:: urban matters

John Barton’s books include

Not Avatars and The Essential Douglas LePan, winner of a 2020 eLit Award. Lost Family, his twelfth poetry book, was nominated for the 2021 Derek Walcott Prize. He lives in Victoria.

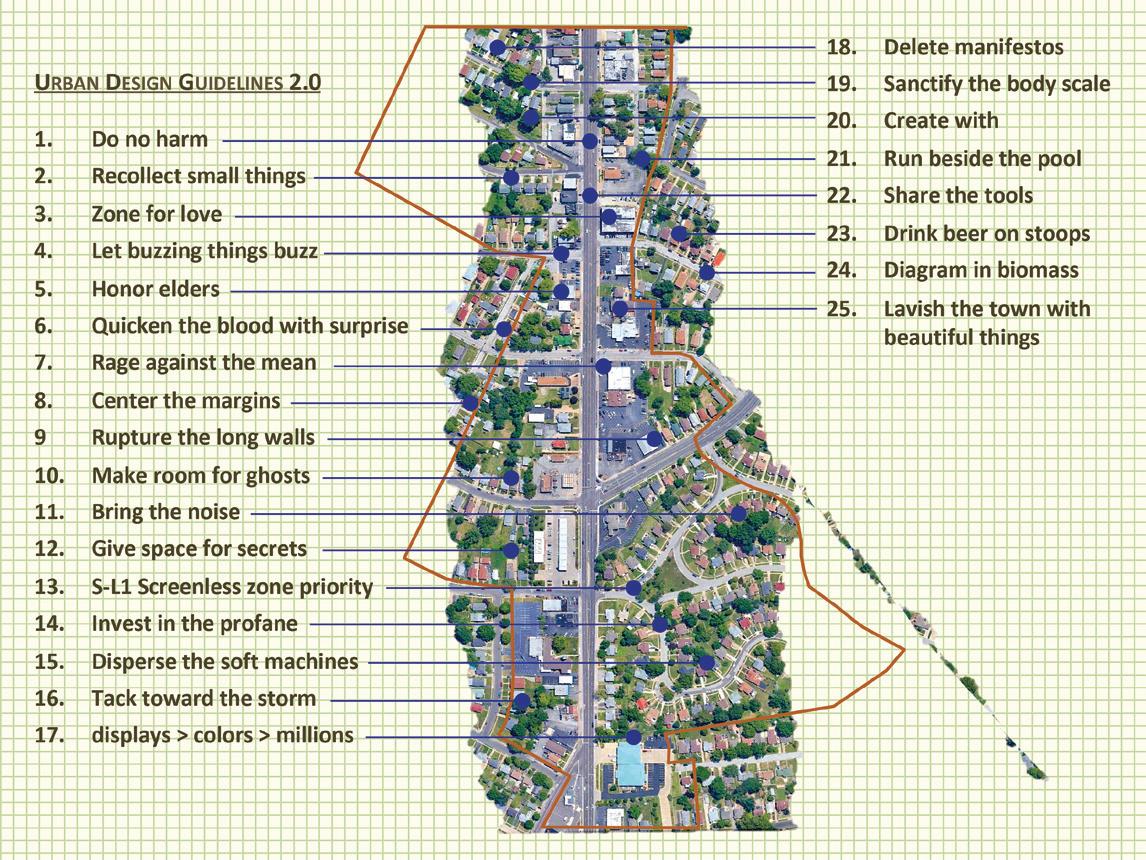

cartographies: urban design guidelines 2.0

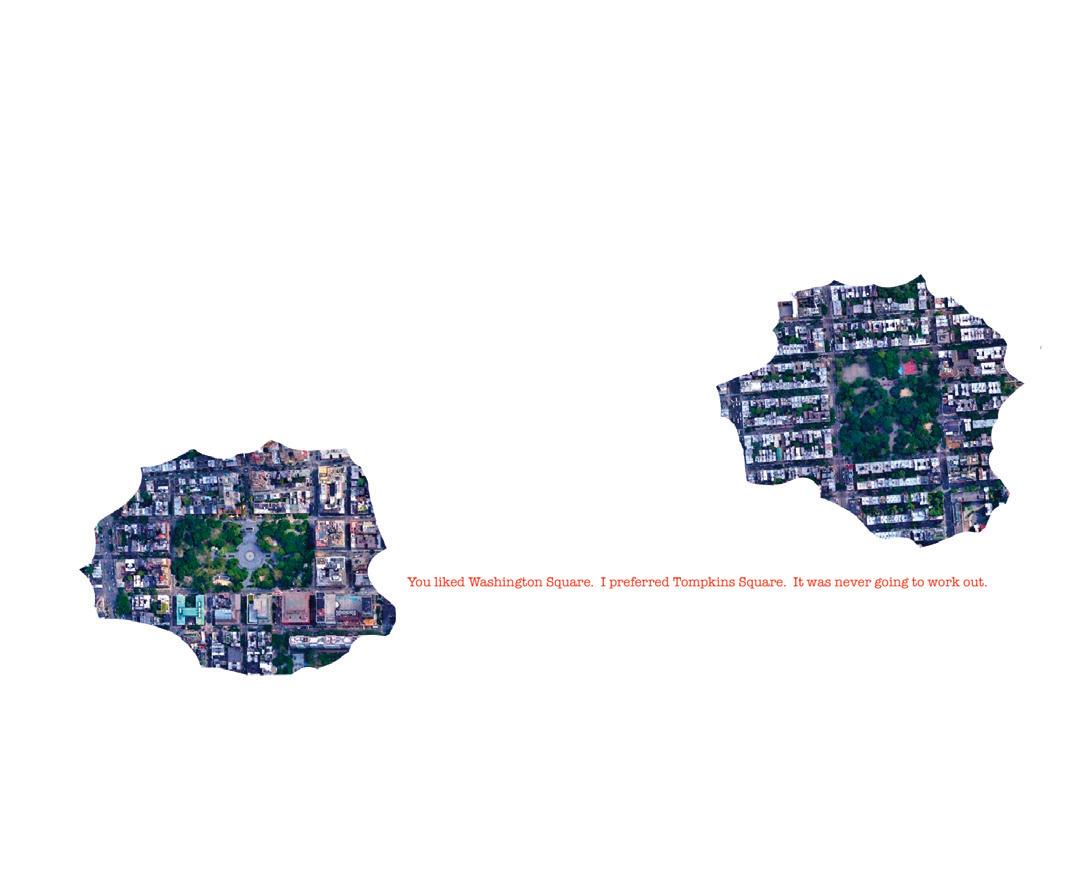

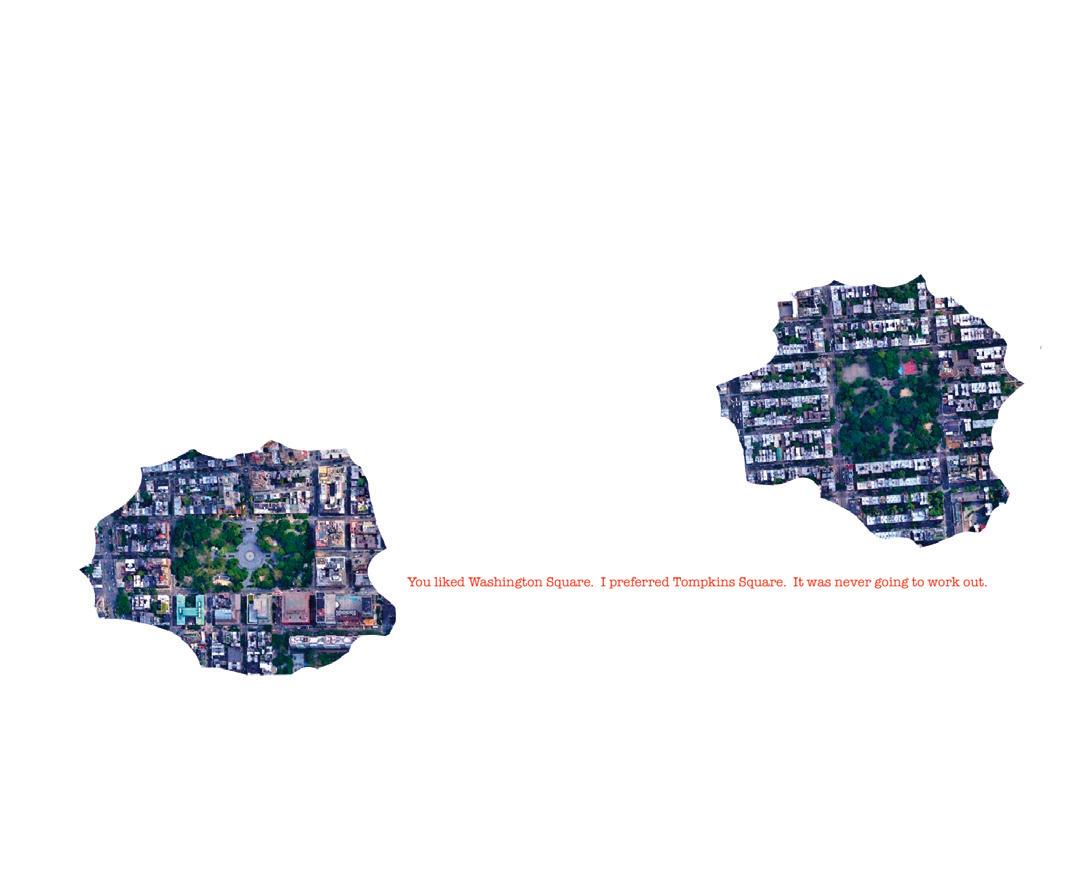

joseph heathcott

joseph heathcott

Joseph Heathcott is Associate Professor and Chair of Urban and Environmental Studies at The New School in New York. He studies the metropolis and its diverse cultures, institutions and environments within a comparative and global perspective. www.heathcott.nyc

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 31

Joseph Heathcott

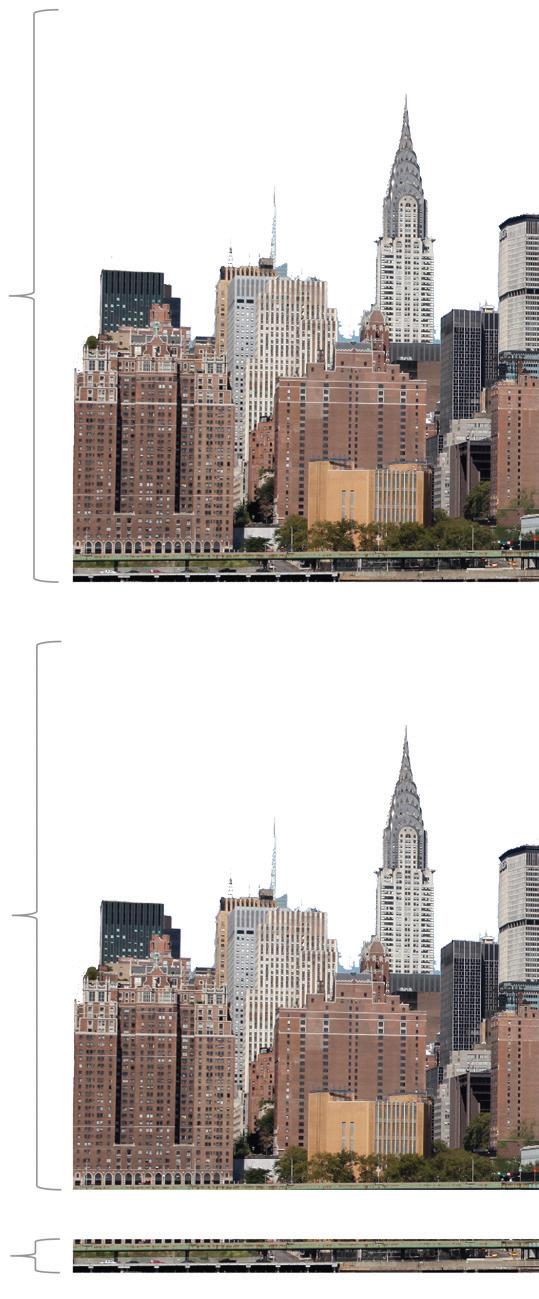

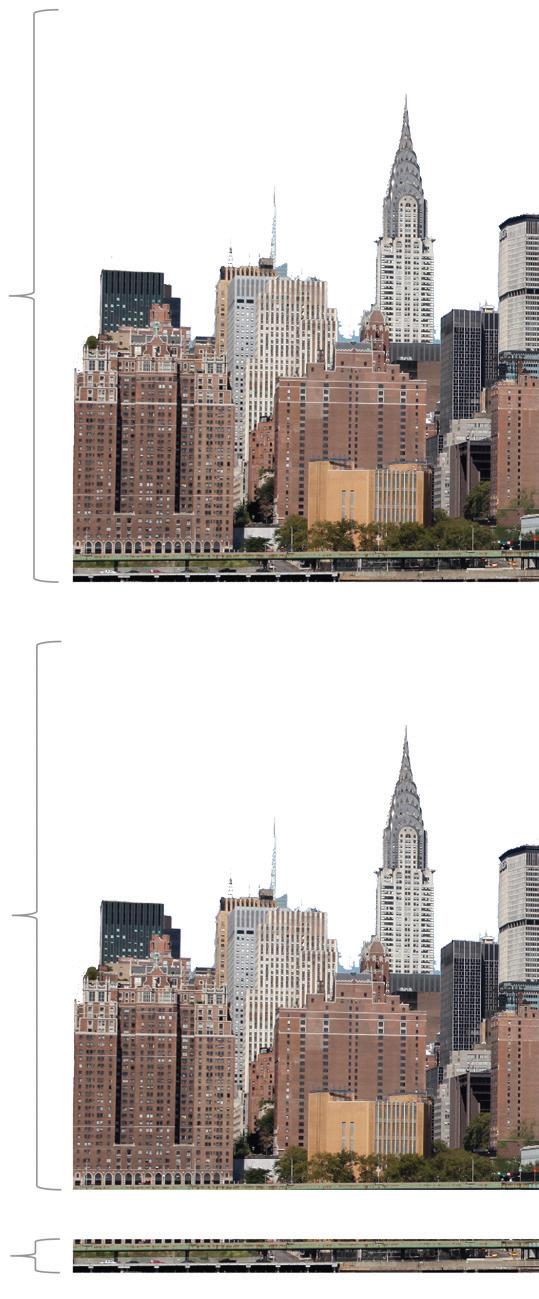

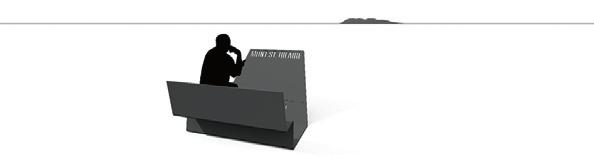

cartographies: decolonised manhattan

joseph heathcott

joseph heathcott

COLONIAL ARCHITECTURE

Settler colonial architecture comes in many forms, from the British farm houses of East Africa to the Spanish churches of the 'New World'. In all cases, such architecture takes hold within the process of land enclosure and expropriation on a global scale. Over the past 400 years, this process has been drilled in the notion of property – land and 'improvements' that can be owned in sovereign fee simple. When the Dutch 'purchased' Manahatta from the Lenape for 60 guilders, they imagined it as a property transaction. However, for the semimigratory Lenape, land was part of a radically different episteme, a fundament no more 'ownable' than air or water. For them, the purchase was a gift from the Dutch in exchange for the use of the land for hunting, fishing and gathering. Today, the notion of property, owned and transacted through markets, underpins settler colonial architecture within the capitalist world system.

DECOLONIAL ARCHITECTURE

The shift to a decolonized architecure cannot be realized through form. Architecture is not buildings, but rather a system of relations that pivot around the habitation of land. Thus, architecture after colonialism will necessarily be situated within a reconceptualization of land itself. While new designs might emerge from this shift, decolonized architecture is unthinkable in the context of property markets and the spatial fix of capital. In the case of Manahatta, we propose the re-expropriation of the land to be held in trust by a council of indigenous people. The buildings (once called 'improvements', now called 'allowances') will remain with their owners, subject to comprehensive rent controls. Owners will pay ground rent to the trust for the right to use the land. Proceeds from ground rent will be dedicated to free housing, education and health care for native peoples. The trust retains right of first refusal over the sale of any building, which will be dedicated either to a 'right of return' for Lenape people or to subtraction to restore the land to nature.

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 32

DECOLONIZED ARCHITECTURE LAND ALLOWANCE PROPERTY

PROGRAM FOR A

:: urban matters

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 33

LABORATORY FOR URBAN SPATIAL + LANDSCAPE RESEARCH, NEW YORK, NY

PG 1 OF 1

CONCEPT SKETCH

(re)mapping: tracing politics in urban space

lejla odobašic novo and aleksandar obradovic

Street names play a powerful role in the formation of collective and national identities, and in the legitimisation of political ideologies. With a radical formation of a new ruling elite, the renaming of streets, public spaces and public institutions becomes a reflection of the new ideologies. New maps become testaments to a historical narrative always under reconstruction by those in power.

The deliberate renaming of streets in post-communist power shifts are a reconfiguration of space and history, a fundamental and essential element of post-communist transformation, creating new public iconographic landscapes in accord with the principles of the new regimes.

In the former Yugoslavia where street names often celebrated socialist ideals, a series of ethno-national conflicts within its different republics resulted in the fragmentation of geographies and the resurrection of former nationalisms. We looked at two cities, Belgrade (the former capital of Yugoslavia and the seat of Yugoslav power during the 1990’s conflict) and Sarajevo (the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina, one of the former Yugoslav republics and now an independent country).

Sarajevo was the most heterogeneous in terms of its population and the most reflective of the Yugoslav notion of ‘brotherhood and unity’ in the way its population coexisted; it is the city that suffered the longest siege in modern history at the hands of the Serb forces. After the last war in the 1990’s, East Sarajevo was built under the territory of Republika Srpska almost as an alternate Sarajevo with its own historical narrative that glorifies the Serbian nation.

We analysed the historical undercurrents that defined the name changes in the historic cores of the two cities, and the ways in which the same tools were most successfully used in creating and defining new national identities in both.

The limitation of a study based on the political significance of historic cores is their chronological longevity that withstands political changes. However, these areas play a significant role in the mental map of citizens and thus the formation of collective identity. It is most common that historic centres, buildings, squares, streets, and urban scenes of the capital cities become the image of that nation.

We examined the names of 52 streets and public spaces in Belgrade and 112 in Sarajevo in 1990, just before the fall of Yugoslavia, and then in 2020. In Belgrade, the names of certain streets have changed multiple times in this thirty-year period and some are still in the process of changing. In Sarajevo on the other hand, most changes of street names in the study area occurred between 1992-1995, as the new independent Bosnia and Herzegovina was being formed. The new ideals of autonomous Bosnian identity were rooted in the old historical patterns that attest to that autonomy.

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 34

´ ´ :: urban matters

Belgrade

When we look at the last 30 years, we see an almost complete de-commemoration of the National Liberation War, the Labour Movement, international co-operation and toponyms from the former Yugoslavia. Political opportunism and waves of revisionism have removed any cosmopolitan spirit from the streets of Belgrade’s core. Changing the names of squares and streets was a tool to silence ideological opponents and establish the value-ideological system of those with power in public space and discourse.

Belgrade’s central streets were filled with old and new heroes, chosen to reflect what was useful for power holders in that historical and political moment. The monarchy, the church, and other ‘verified values of the Serbian people’ got their streets and boulevards. Controversial personalities of both older and newer Serbian history were given their place of remembrance in public space, including the formerly prominent, recently deceased, members of the party.

The constant of the Serbian political elite in dealing with the culture of memory in the last three decades has been mono-ethnic nationalism, a policy diligently pursued by both Miloševic and opposition leaders. The cosmopolitan Belgrade that existed until the end of the 1980s, when it was the capital not only of a multi-ethnic and multicultural Yugoslavia, but also the political centre of the Non-Aligned Movement which gathered a diverse circle of African, Asian and Latin American states, is now completely absent. Central Belgrade now commemorates Serbian ethno-nationalism provincialising the city. The capital of a multi-ethnic Yugoslavia has become the centre of the so-called Serbian world. On the symbolic battlefields of the central city streets, the International Labour and Liberation Movement are lost in the onslaught of revisionist heroes. Belgrade has turned the circle of history. New enemies of the Serbian people are being found again, and this time it’s not just people, but cities.

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 35

Sarajevo

With the breakup of Yugoslavia and the establishment of Bosnian and Herzegovinian sovereignty in 1992, the renaming of the streets in Sarajevo was part of the deliberate strategy to break away from Socialist ideals and heritage, thus creating a specifically Bosnian history. All the old, ‘negative’ associations were replaced by names deemed to be more acceptable as part of a deliberate reshaping of this particular aspect of place. Through a selective reconstruction of Bosnian history to appease contemporary nationalist aspirations, there was a conscious invoking of a collective memory of both distant and recent events to enhance group identity.

The nationalistic renaming of streets in Sarajevo reflects the Commission’s strong desire, on behalf of the city’s inhabitants, to establish an identity that can contribute to development of a more secure basis for self-government and territorial integrity. Building a new national narrative that highlights the differences between Bosnia and its neighbouring states has emphasised the nation as specifically consisting of Bosnian Muslims, whose awareness of their own distinctive heritage is differentiated from Bosnian Croats and Bosnian Serbs. The same is true in East Sarajevo, where the Serbian national narrative has been hardened. The inevitable inconsistencies in historical narratives and political ideologies between the two parts of Bosnia and Herzegovina makes one question the relationships between ‘state’ and ‘nation’, especially within the context of the former Yugoslavia.

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 36

:: urban matters

Street names, sensitive pointers to the link between political processes and the urban landscape, are tied inevitably to nation building and state formation. Political ownership of the urbanscape through urban nomenclature is especially susceptible to revision, especially in the wake of major power shifts and regime changes. Toponyms are powerful cultural signifiers and vehicles of memory to which political authorities resort to in their bid to symbolically appropriate space by inscribing into the landscape a self-legitimising iconography of power. The large shift from the common Socialist narrative to localised and national ones, is reflected in the new names of the toponyms of both cities.

Sarajevo’s 1,425 days under seige between 1992 and1996 coincided with its main wave of street name changes. As the Bosnian Serb army shelled the city, the determinants that had connected it to Yugoslavia disappeared from Sarajevo. Belgrade, on the other hand, was not directly affected by the war and changes to its streets came in stages – during the period of the Yugoslav wars (1991-1996), only a small number of streets were changed because Miloševic insisted on prolonging the illusion of Belgrade as the Yugoslav capital.

What is similar in both Sarajevo and Belgrade is how the streets were renamed as a return to a ‘better past’. The meaning of that past differs as much as the history of these two cities, but the principles by which its ‘goodness’ is determined are much the same. Both cities have been flooded with toponyms that refer to personalities and historical determinants important for the construction of the Bosniak and Serb ethnic identity, respectively. Socialism, the labour movement, and the industrialisation which brought economic progress to both Bosnia and Serbia are ultimately rejected, replaced by a mythical golden age of kings and ancient monasteries for Belgrade and traditional Ottoman names for Sarajevo.

The return to a mono-ethnic past has reduced the profile of multi-ethnicity in the narratives of public spaces in both cities. As the national territory shrank, the toponyms in the capitals became more and more exclusive. Ethnic minorities were not desirable bearers of public narrative; their discourse and memories needed to be removed. Other minorities did not fare any better. Insisting on ethnicity and creating a single, narrow identity has closed these cities. They both symbolically and spiritually rejected their cosmopolitan settlement and voluntarily turned into a province.

We are going to extend this study to the remainder of capital cities of former Yugoslavia and to see how the revisionist patterns occurred in Ljubljana and Zagreb (both cities now in the EU) as well as Podgorica (once Titograd) and Skopje. p

Toponyms are divided and subdivided into categories.

pe ople

1 Influential persons in four subgroups: names linked to statehood – presidents, influential politicians, army leaders, kings and nobility, mayors

2 culture-creators and artists – poets, writers, painters, sculptors, architects, persons who have had significant cultural impact, scientists and academics

3 religion – saints, religious orders, priests, bishops, and popes; buildings named after any religious affiliation

4 entrepreneurs

g eographical features

1 rivers, towns, regions, countries, mountains

2 landmarks – railways stations, markets, river-banks

3 traits or attributes such as narrow, steep, wide, long, hill history

1 historical events, institutions, and historical dates (e.g. May 1st International Labour Day),

2 social movements, armies. There is a separate subgroup for streets named after historical events and intuitions within Federal Yugoslavia (SFRJ), as this period played a crucial role in the creation of the names within the 1990 analysis, and the common political narrative of these two cities.

crafts and trades

1 butchers, blacksmiths, millers, weavers

S ome of the street names could be placed into more than one group. If a writer or culturally important person was also a participant in an important political movement the decision had to be made as to the most important role of the person involved: either in the cultural- artistic field, or in the sphere of statehood.

for more information

Interactive maps of the two cities are available at http://remakinghistory.philopolitics.org/ You can also download the full version of the publication in PDF format at the same link.

acknowledgements

This research was generously funded by Tandem for Culture - Western Balkan in cooperation with MitOSt and European Cultural Foundation.

references

Robinson, G.M., Engelstoft, S. & Pobric, A. ‘Re- making Sarajevo: Bosnian Nationalism after the Dayton Accord’. Political Geography 20: 2001. pp 957-980

Light, D. ‘Street names in Bucharest, 1990-1997: exploring the modern historical geographies of post- socialist change’. Journal of Historical Geography 30, 2004. pp154-172.

Đordevic, N. ‘Serbian World — a dangerous idea?, Emerging Europe’2021. (accessed 6th September 2022), https://emerging-europe.com/news/serbian-world-a-dangerousidea/

Lejla Odobašic Novo is a Bosnian-Canadian architect licenced by the OAA. She is currently teaching as an Associate Professor at the International Burch University, Department of Architecture in Sarajevo. Her research lies at the intersection of culture and politics, exploring how this junction manifests itself through architecture in contested spaces.

Aleksandar Obradovic is a cultural anthropologist and founder of the Philopolitics think tank. He is a non-academic researcher in areas of urban space and political anthropology. His research is focused on the relationship between public space and power, as well as minority narratives that contest mainstream narratives and appropriation of public spaces.

on site review 42: atlas :: being in place 37

´ ´´

e xchange

francesca vivenza

Michel Boucher

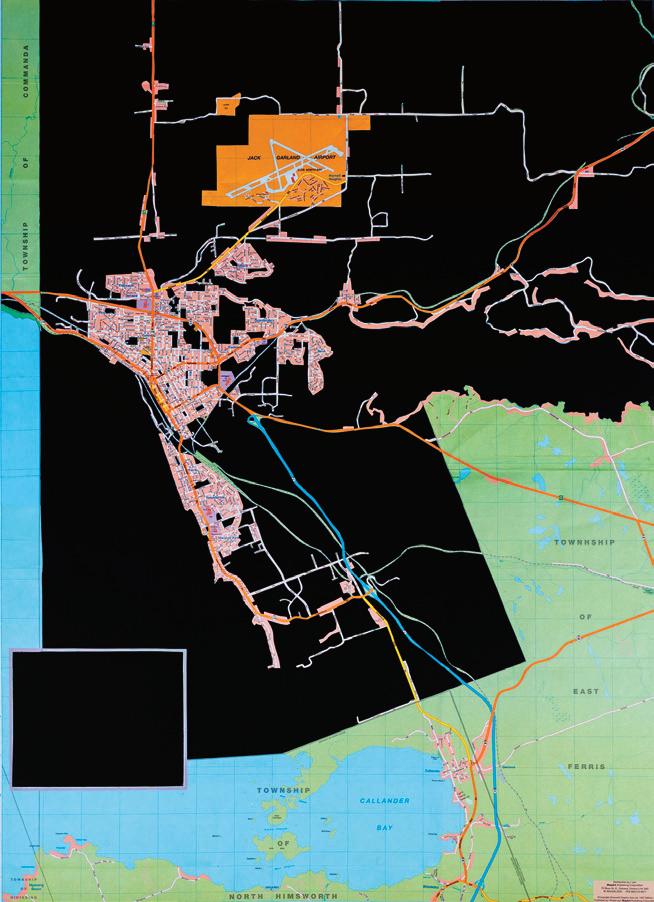

I found this small sketch in one of my husband’s field books labelled N ONTARIO – DIMENSION STONE/KENORA CAMP/15 – 21 SEPT 1986

It is a rough field draft drawn as base map for some geological work on a piece of land 7 x 4 km wide.

Fascinated, I asked him to confirm the location. I was stunned to find the little map is actually a piece of Zimbabwe. I interpreted it as a funny mishap, Zimbabwe in the Kenora region. At the same time, this has given me a sense of geographic, ecological disorder and instability: a connection to the North-South exploitation on our planet.

My husband has inadvertently created a space of exchanges between Kenora and Zimbabwe, two exploitable territories for their mineral resources, one on the North and the other on the South of the globe, both with a colonial history.

This new place, if disturbing, I find quite disarming. That which is not possible in geography, might be possible with art.

Francesca Vivenza is a Toronto based mixed-media artist whose works on paper, exhibited internationally, include maps. Focusing on the transformation of the old into the new, her works address themes of travel, migration and displacement. www.francescavivenza.com

on site review 42: atlas of belonging 38

:: mysteries

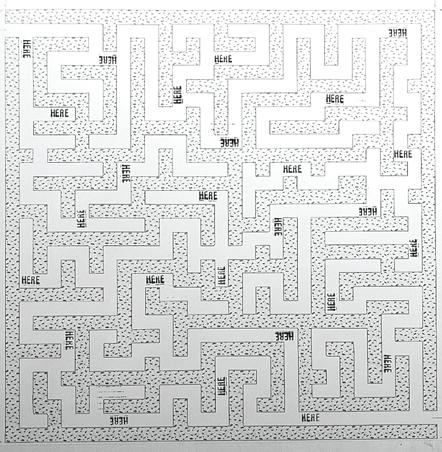

an uncertain proposition

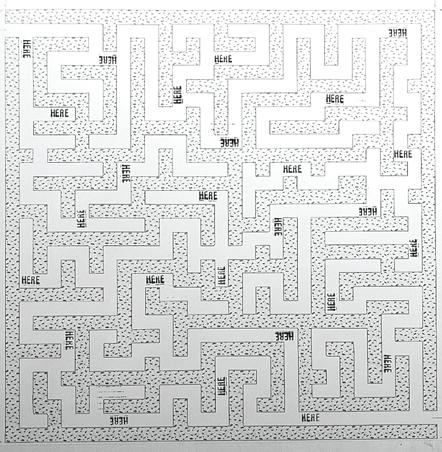

patrick mahon , thomas mahon

Mazes are contexts where to be momentarily lost can be both pleasurably distracting and troubling; a predicament to be negotiated, where location involves much speculation.

David Wagoner's 1971 poem 'Lost'1 shows how we might locate ourselves:

Stand still. The trees ahead and bushes beside you Are not lost. Wherever you are is called Here, And you must treat it as a powerful stranger, Must ask permission to know it and be known. The forest breathes. Listen. It answers, I have made this place around you. If you leave it, you may come back again, saying Here. No two trees are the same to Raven. No two branches are the same to Wren. If what a tree or a bush does is lost on you, You are surely lost. Stand still. The forest knows Where you are. You must let it find you.

The tiny 4 x 6" drawing by Thomas when he was eight years old shows an airplane flight that Patrick took in 2000. No negotiation, just departure and arrival and confusion in between.

B oth the poem and the drawing were made when our planetary environmental crisis did not loom so large. We are adding another piece, an imaginary leafy maze. Its walls are endangered plants and trees. To stop in this ordered but existentially fragile maze is a moment of incommensurability: one is neither here nor there.

and fosters hopefulness. www.patrickmahon.ca

Thomas Mahon, a designer and architect based in Brooklyn, has worked across a wide range of projects and media, from graphic design to urban scale initiatives and master plans, with an interest in ecology and environmental equity.

on site review 42: atlas of belonging 39

Patrick Mahon, artist, curator and professor of Visual Arts at Western University, is committed to art as a vehicle of contemporary expression that helps imagine transformation

1 Wagoner, David. 'Lost' (1971) Poetry Magazine. Chicago: Poetry Foundation, 2022. p 219

p

Flight Maze

Here Maze

Leafy Maze

unmapping maps

lisa rapoport

lisa rapoport

Mapping is an act of curation, a sorting out of actual lived experience into a series of assembled components that combine into a systematic narrative that we learn to understand and assume is the organisation of the experience. As an architect, urban designer and teacher, I have come to trust this desire for organizing principles, the results being so easily analysed. But my experience of moving through space is much the opposite – haphazard, coincidental, haptic, with many narratives colliding, unconscious, and dominated by time. A map implies time only by distance, without the mess of wandering, pondering or traffic.

Though a city may be organised on a grid, my movement across it may include cutting corners, making diagonal paths, hopping into and through buildings that join streets – anything but linear. My mental map is made of these ingrained routes and shortcuts along with personal markers (where so-and-so lived, where I fell off my bike…); so much more than the organised structure of a street map. This extends to all spatial experience: though I know that the sun is an object at the centre of a series of orbiting planets including earth, and therefore I