Learn how one community of youth is cultivating fresh food in a new way.

Young members of Jewish youth communities in Louisville are igniting a shift in faith.

How the Forecastle festival grew from Tyler Park to Tyler, the Creator.

A mother and her daughters embody what it means to advocate for themselves and their community.

We are all a part of the bigger picture.

Inside each of us are fundamental facets of our identities, central pieces of our makeup. They are our passions, our driving forces, the communities we have grown up with, and our family lineages. When we are lost in a sea of unknowns, we can turn to our foundations for answers.

Our roots hold us to one another, a web of deep ties to each other: a conduit for connectivity.

In On the Record’s second-ever themed issue, we explore the dichotomy between our roots — in our culture, our city, our history — and what remains up in the air — our careers, our artistry, our futures. Therein lies the inspiration for the double-sided magazine you currently hold.

While some stories on this side fit the rooted theme literally — the young farmers cultivating our city’s community gardens and a local group signifying the progression of Jewish tradition; others explore a more figurative meaning — a music festival at the core of the Louisville community and the health conditions rooted in our genetic makeup.

In this half of the issue, we take a look at roots in every form they take. When you come to the end of this side, close and flip the magazine to read the remaining four stories.

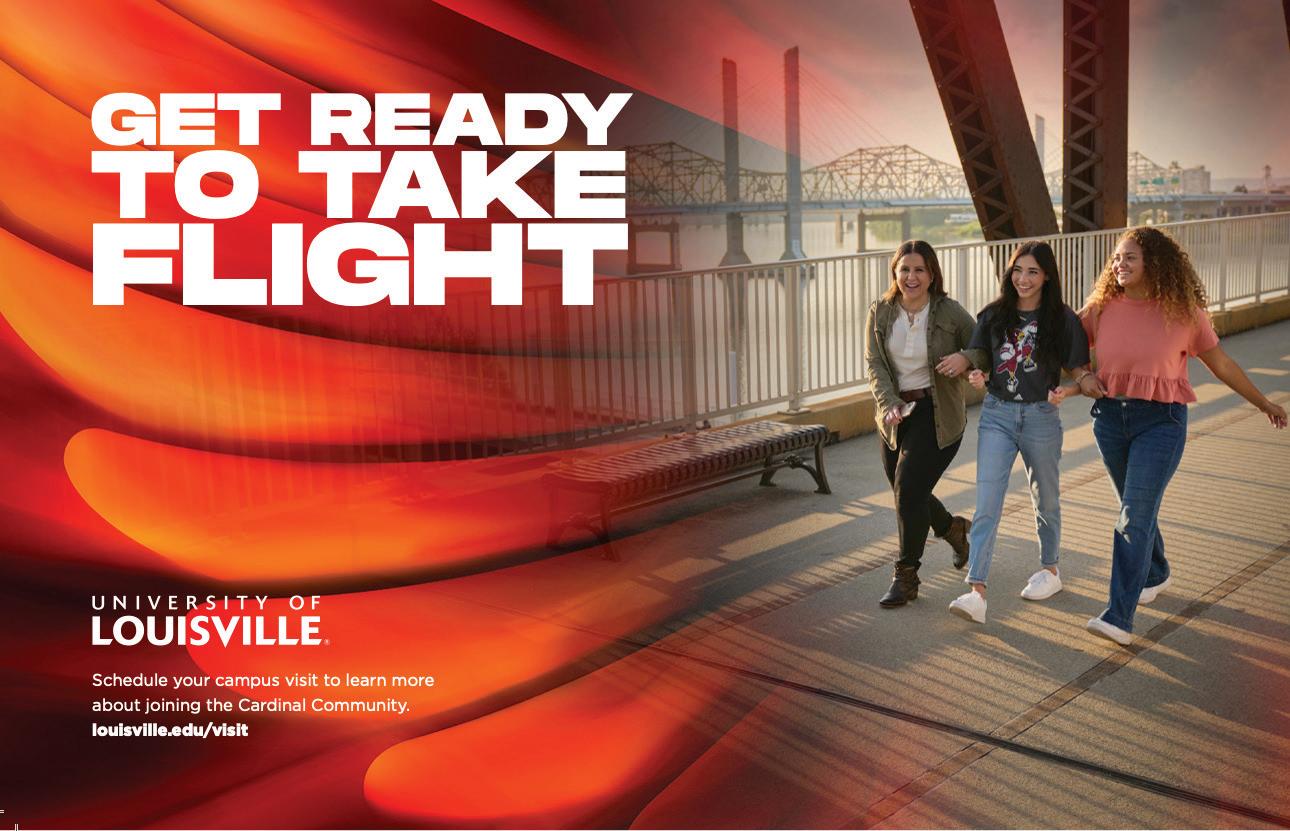

ON THE RECORD is a magazine by and for the youth of Louisville. In 2015, our publication transitioned its format from duPont Manual High School’s tabloidsize school newspaper, the Crimson Record, to a magazine that focuses on in-depth storytelling with Louisville-wide audience and distribution. Using our training as writers, photographers, and designers, our mission is to create quality local journalism for youth that includes the crucial but often overlooked youth perspective. Each issue’s content is determined and produced by youth.

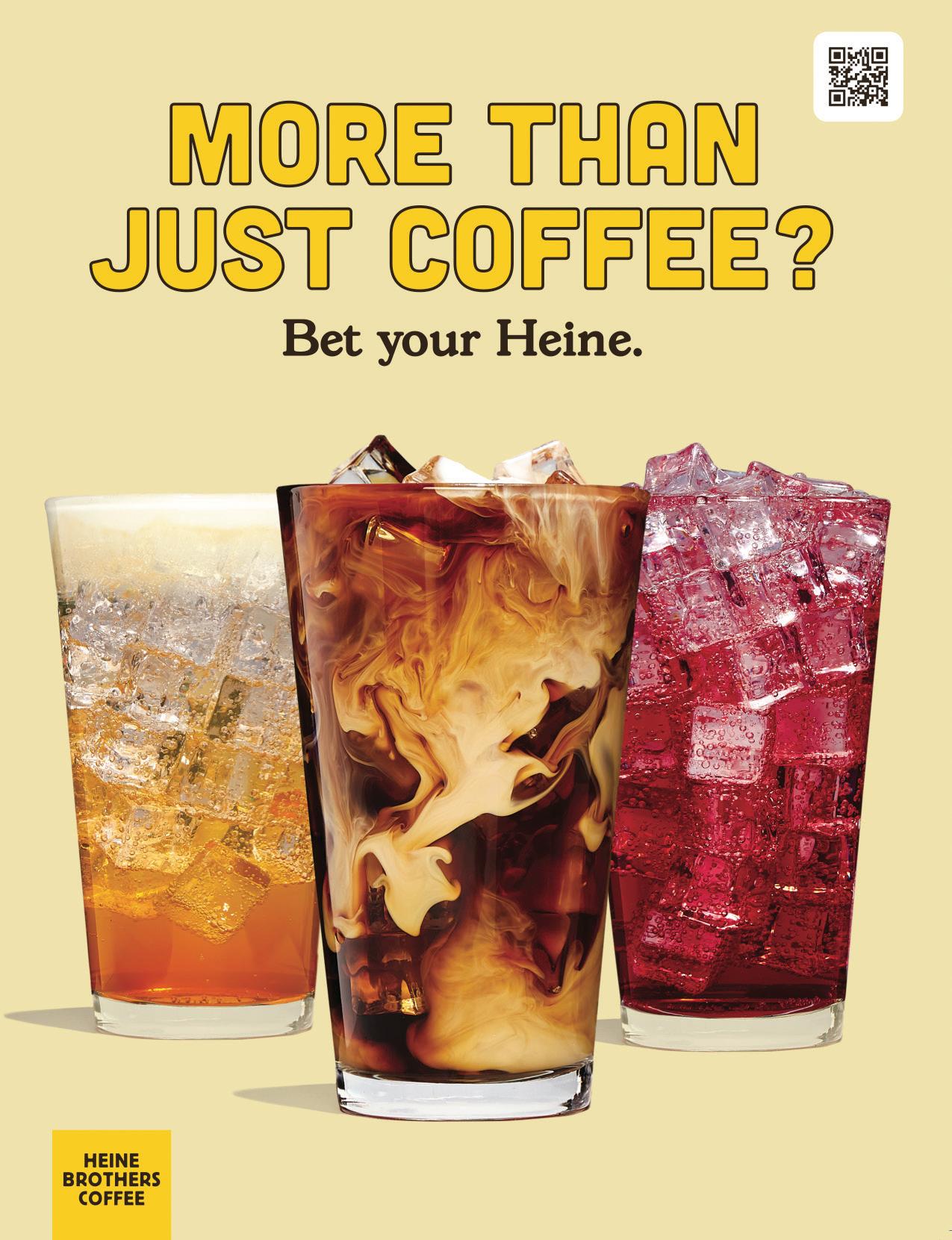

On the Record is an educational and journalistic enterprise that does not accept school funding.

Because this magazine is entirely funded by donors and advertisers, we need long-term community partners in advertising, sponsorships and underwriting.

To become an advertiser, sponsor, or supporter please see page 17 of Up in the Air.

OTR is distributed freely in youth-friendly businesses and via Louisville-area teachers who request copies.

To distribute OTR to your students or in your business, please contact us.

Subscriptions require a sponsorship. Learn more about sponsoring on page 4.

Most stories may be found online at ontherecordmag. com. Additional social media content can be found on Instagram and Twitter: @ontherecordmag

On the Record is a member of the National Scholastic Press Association, the Columbia High School Press Association, and the Kentucky High School Journalism Association. Previous awards include NSPA Pacemakers and CSPA Gold Crowns. Individual stories have earned multiple NSPA Story of the Year placements, CSPA Gold Circles and the Brasler Prize.

On the Record is published by the students of the Journalism & Communication Magnet at duPont Manual High School, 120 W. Lee St., Louisville, KY 40208. Visit us at ontherecordmag.com, email at ontherecord@manualjc.com.

You may also contact the faculty adviser, Liz Palmer, at liz.palmer@manualjc.com.

From the street, it didn’t look like much: a few raised gardening beds, lots of tall grasses and flowers, one of those small library boxes, and – perhaps the most noticeable – the two greenhouses. Across the street, houses sat side by side. There was an old mattress perched at the bottom of a driveway and trash cans waiting to be emptied. To someone passing by, the land was merely a small break in the rows and rows of houses in Louisville’s Shawnee neighborhood. However, when truly examined, the life living amongst this small plot of land was far greater than what was visible at first glance.

Behind a line of trees, the garden opened up. There were rows of raised soil stretched out parallel to the road. At the far end, a group of young people stood; some of their arms were woven across their chests, others had their hands in their pockets. Many of their eyes wandered from side to side, but they all focused on one woman in particular: Grace

Mican. She stood facing the group, a casual lean in her hip demonstrating how comfortable she felt in the role. A small bag filled with beet seeds rested in the palms of her hands.

Mican called out instructions to the group.

“If you are on the center line, plant every three and nine inches. On the outer two rows, plant at six and 12.”

The group absorbed the information as it came. To them, understanding it was as simple as reciting the ABCs. To anyone else, it was a foreign language.

“The theory is abstract until we actually get our hands dirty,” Mican said.

After a few more minutes, the crew dispersed down the row, planting themselves at their assigned spots along the tape measure.

They worked quietly and with an attentive focus on detail. Their movements became seemingly robotic: place a seed, measure using their hand, place another seed. Repeat, repeat,

repeat. The process of planting seeds across the whole row took nearly ten minutes in total. However, the process didn’t just begin nor was it going to be over anytime soon. This was just one step along the way.

For college student Nick Bremer, 22, this wasn't his first time planting seeds with the group. He knew better than most that this step of the process was merely the beginning, and that waiting for the food to grow was debatably the hardest part.

Bremer came to the city four years ago to attend the University of Louisville, where he majored in sustainability. While in school, he wanted to get a job focused on his areas of interest, so he looked to Handshake, a website dedicated to connecting college students with employment opportunities. That is where he stumbled upon the Food Literacy Project (FLP).

“The job seemed like the perfect combination of being outside and hands-on work,

How Louisville’s Youth Community Agriculture Project is empowering a new generation of urban farmers.

Fill 'em Up - A pile of watering cans sits inside the greenhouse at the Shawnee People’s Garden on April 14. The Food Literacy Project not only grew vegetables in the field, but also fostered plants inside the greenhouse.

by Mia Leon.

while also getting to know the community,” Bremer said.

The FLP is a non-profit organization in Louisville dedicated to connecting the community with agriculture. They look to the next generation of young people in Louisville to teach them about the importance of food systems and being aware of where their food comes from. They have multiple programs with different underlying values and varying opportunities. Bremer is part of the Youth Community Agriculture Program (YCAP), an employment opportunity for those aged 16 to 21.

During the summer months, members of the program work 30 hours a week in the garden. They do everything from planting and harvesting to learning from speakers brought in from around the community. The fall and spring seasons are similar, except they work fewer hours, averaging 12 a week. The program, however, hasn't always been this extensive.

It started off slow with groups of school kids coming out monthly to Oxmoor Country Club, which is where the FLP originated.

“Teachers were like, ‘Kids don't know where their food comes from,'” said Alix Davidson, director of strategic initiatives at the FLP. “We need to get them out to a farm so they can see it’.”

While these one-time field trips were a good beginning for the organization, they realized that it was only giving students a snapshot of what farm life truly entailed.

“There's an opportunity to work towards more systemic changes and engage them on a deeper level when we are doing longer term programming with the same youth,” Davidson said.

So in 2011, YCAP began as a way to do that, and it has been developing ever since.

Mican is the program manager. She oversees everything YCAP does, from the farm's crop rotation and planning to searching for

experts that are willing to come talk with the crew. In addition, she is the one who runs the YCAP work days.

Mican first volunteered for the FLP back in 2014, but didn’t officially start working there until after she graduated college with a degree in environmental science from Bellarmine University in 2017.

“I was really drawn to food systems in general because I was in this environmental program,” Mican said. “I often feel so dwarfed by the size of the issues that we face when we're talking about our environmental situation these days.”

Mican came to YCAP with the goal of bringing power back to youth, a group she said often gets discounted for not having much to offer due to their age and lack of experience.

“I think that there is a lot of energy and potential and curiosity in the youth, right?”

Mican said. “And often not lots

"Youth need to be the drivers of change because this will be their world and their problems."Photo

of opportunities to explore those things through dignified work.”

Growing up in northern Illinois, Bremer was in a bit of shock when he initially joined YCAP.

“I grew up in suburbia,” Bremer said. “So, being on a farm, in an urban setting, that was not even something that seemed possible to me.”

On his first day last summer, they met at the People’s Garden, tucked back into Louisville’s Shawnee neighborhood. This was YCAP’s first season at this garden, and it had given them more freedom to do what they want with the land.

When he arrived, they did the usual: getting to know the crew and going on farm tours. However, the experience was far different than what most of the crew had done for work before.

“It was just a weird environment,” Bremer said.

It wasn’t like the fast food jobs he had worked in the past. This job was outdoors, didn’t have set uniforms, and Bremer actually cared about his voice being heard.

“You're not going to know everything off the bat,” Bremer said. “There's no fault in not knowing. You know, there's no losing or being wrong – it's just learning as you go.”

As the weeks passed, Bremer settled into the new environment.

“I don't feel alone,” Bremer said. “I actually like coming to work and am sad when it rains.”

YCAP is built around giving students the resources they need to grow into independent and capable individuals.

“We create a lot of opportunities for their voices to

be heard,” Davidson said, “which is sometimes intimidating, and we really try not to push them too much, but to create opportunities where they really can step out of their comfort zone.”

While Davidson and Mican currently have more knowledge and experience than the farm crew, they know that one day these youth will be the ones making the decisions.

“Youth need to be the drivers of change because this will be their world and their problems,” Mican said.

The YCAP crew knows this and are already aware of the positive effects they are creating.

“Being able to understand what you're eating and where it comes from is a privilege that not everyone has,” Bremer said.

Their impact extends beyond the borders of the

Beets are Treats - Food Literacy Project intern Cala Salah, 26, plants beet seeds at the Shawnee People’s Garden on April 14. Photo by Mia Leon.People’s Garden and into the surrounding neighborhoods.

“We're doing very community based work, and something that we try to avoid as an organization is coming in from the outside and saying, 'We know how to solve the problems,'” Mican said. “Because the people who live in the communities are the experts on what is happening there and how we can shift what is happening there to better serve them. We’re starting to have those conversations about the real versus the ideal and how do we push toward what would be more ideal.”

Out at the People’s Garden, the YCAP crew gathered around a seemingly normal pickup truck. Its coat of red paint was slightly scratched up, and the sides were marked with the FLP’s logo.

Mican, again, stood facing the group, this time leaning up against the bed of the truck. The bed was filled with soil and old wilted plants that hadn’t seen the sun or water in months.

She explained what it was: the Truck Farm, a garden on wheels.

The crew began pulling out all the dead plants that had settled there throughout the cold winter months. Once satisfied with their work, they brought out new seedlings. As they planted, they had lighthearted conversations and made jokes.

“It’s a pickup truck that has a whole bunch of dirt in the bed of the truck, and every season we try and plant veggies, herbs, whatever we can fit in there,” Bremer said. But it is more a way to show that there's not just one way to farm.”

The FLP drives it around to different events, such as farmers’ markets and camps around Louisville. The community is able to see how gardening isn’t stagnant and can be beneficial even outside of its standard form.

“Some people may think it's silly, but it is a portable farm that can provide for you or anyone,” Bremer said.

While access to land in Louisville’s West End is limited, the Truck Farm showcases how space isn’t as vital to growing fresh foods as previously thought. People can still grow and provide for themselves in small areas such as windowsill gardens, or even out of a truck bed.

Beyond just growing food, YCAP looks to educate the crew on healthy food habits and how to cook with them.

“You can learn how to grow food and you can have access to fresh vegetables sometimes,” Mican said. “But if you don’t know what to do with them, then they are just sitting in your fridge, looking at you.”

They take foods that kids are already exposed to, such as pizza, and add a fresh twist to them. They will add kale and make the sauce from scratch using other vegetables grown on the farm.

As a high school student, Maggie Epperson, 22, first started working as part of YCAP back in 2017. She recalls feeling uneasy in a new environment, similar to Bremer.

“I remember my thought was, ‘Okay, literally I am going to die on this farm and get murdered, or I am going to love it’ — I ended up loving it,” Epperson said.

Epperson was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes when she was two years old. She

grew up hyperfixated on the foods she was eating, moreso than other kids around her.

“That kind of made me look at food a different way just cause you have to count the carbs,” Epperson said. “You have to look at it a different way than most people would.”

She came to the FLP with the hope of expanding her knowledge on foods and where they come from, as food has a unique role in her own life.

While Epperson was in YCAP over the summer, her days were split in half, with the mornings including work on the farm and the afternoons occupied by other educational activities, which she enjoyed more.

One day, the crew took a field trip to another farm in the West End. Epperson introduced herself to a farmer who was growing vegetables. She asked how he was going to prepare the food, and the farmer responded that he didn’t eat very many vegetables. Epperson found it weird that a farmer who grew fresh food wouldn’t like or know how to cook the foods he was growing.

It wasn’t until later that she realized many people in Louisville haven’t grown up in a fooddiverse household, where fresh vegetables are available.

“You hear the term food desert, but how does that actually apply to the people living in them?” Epperson said. ”How is their relationship with food different?”

Through YCAP, Epperson saw how peoples’ relationships with food differ. After two summer seasons with the program, she went off to college, where she became a classically trained chef at Johnson and Wales University. YCAP made Epperson more curious about food's effects on those around her, and after she graduated from college, she came back to the FLP, this time as an intern helping to guide students through their experience on the farm.

Now Epperson is hoping to share her knowledge and experience through her own business called the Diabetic Nutrition Coach. She hopes to show others that diabetes shouldn’t be a boundary on what they can and can’t eat, and that people can form their own unique relationships with food.

Looking back on her time at YCAP, Epperson is grateful for the program, as it’s had a lasting impact on her. She has used what she has learned to grow into the next phase of her life.

Bremer now stands looking toward his own future. He is finishing out his final season of YCAP, and as of May 14, he has graduated from college.

He says the most valuable lesson he has learned is “patience, lots and lots of patience.” It takes patience to not see the immediate results of his hard work. It took the beets over a week to be visible from the top of the soil, and it will be many more until they are ready to be harvested.

“There’s a moment when sprouts first pop up out of the soil that you know that life is created and that you played some part in that,” Davidson said.

•

- Maggie Epperson, 22“

"You hear the term food desert, but how does that actually apply to the people living in them?"

writing by KARLIE J.

Every Friday evening from elementary to middle school, Jenna Shaps, an 18-year-old senior at Kentucky Country Day School, and her family piled into the car for the ride to her grandparents’ house. As children, Jenna and her brother had to be reminded to put away their toy drums and cars before dinner, but now phones were quietly tucked away without a word. Before the family sat down to eat, they gathered around the kitchen counter where three familiar items laid.

The braided, browned challah bread was freshly baked from a family recipe passed down for generations. The two Shabbat candles, lit by Shaps’ grandmother, stood

BROCKMAN • design by ELLA DYEproudly in their holders, flickering in the low light. The dark red wine, replaced by grape juice for the kids, waited to be opened.

As everyone closed their eyes, a hush fell over the family. Once the prayer and three blessings were spoken, breaking the silence, the hectic week was closed to start one anew.

Shabbat is the Jewish practice of taking rest and devoting time to religion and family. Also called the Jewish Sabbath, Shabbat starts on Friday evening at sundown, and lasts until Saturday with three meals and a morning synagogue service in between.

The Shaps family typically devotes two hours to shutting out distractions, eating a homemade meal,

and laughing together at the dinner table, where they never have a shortage of topics to discuss for Shabbat.

Since Shaps and her younger brother entered high school, though, her family’s Shabbat dinners have slowed from weekly to monthly. Shaps went to Hebrew school to learn the fundamentals of Judaism until eighth grade. She had her bat mitzvah, a celebration of entering Jewish adulthood, at 13. But at 18, Shaps describes herself and her family as less religious than when she was growing up. Instead, she finds her connection to Judaism in a community of teens in BBYO.

BBYO, formerly known as B’nai B’rith Youth Organization, is an

international student-run organization for Jewish teens. The program is “the largest Jewish youth movement in the world,” explained Abigail Goldberg, the city director of BBYO Louisville.

BBYO divides large sections of the U.S. into regions. The KIO region encompasses five cities in Kentucky, Indiana, and Ohio and is one of the fastest-growing, with 300 teens and counting. Regions are then separated into city chapters and, if they have enough participants, chapters are separated into Aleph Zadik Aleph boys (AZAs) and the B’nai B’rith Girls (BBGs).

Shaps became a BBG in eighth grade to stay active in Judaism. Starting in BBYO, Shaps was looking to grow in

the welcoming and reliable community, especially during the uncertainties of high school.

“The experience of being able to be in a room with 3,000 Jewish teens and being able to be my true self, and not have anybody putting me down, makes me feel like I have someone to lean on,” Shaps said.

She took multiple leadership positions, working up to run for N’siah, or president, of the KIO region in the first semester of her senior year.

Her involvement shines a light on why teens like the program, because their peers are the ones stepping up to run it. Goldberg, a BBYO alumna herself, describes her role as city director as being there

to support, not to order. The leadership board of Louisville’s chapter has the freedom to recruit members, organize events, and elect new leaders.

“They’re the ones who write the script. They basically tell me what I need to buy for them because I have the credit card,” Goldberg said. The opportunity to be involved allows those from ages 13 to 18 to feel they are represented in the Jewish community.

“When I look at my synagogue, our entire board is run by people probably over the age of 75,” Shaps said. “It feels like sometimes they’re not really making decisions based on the congregation’s behalf,

more on what they want and what they want to see.”

BBYO also allows teens to define their relationship with Judaism the way they want. There are three main branches of modern Judaism: Orthodox, Conservative, and Reform. Reform is the most relaxed on adhering to traditional Jewish practices and beliefs. Orthodox is a stricter adherence to tradition, such as keeping a kosher diet and separating men and women during service. Conservative, the branch Shaps grew up following, lies in the middle of the two, following the observance of some rules while letting go of others.

Members of BBYO are able to tailor their experiences to their beliefs. Some attend the religious services KIO hosts, while others use BBYO as a way to make friends with those of a similar cultural background.

“It’s more like hanging out with your friends, doing some Judaism, because that’s what connects us all together,” said Shaps.

The diversity of practices and beliefs in Louisville’s Jewish community are reflected on a larger scale in the U.S. In 2020, the Pew Research Center conducted a study surveying the demographics of the U.S. Jewish community. They found respondents were more likely to say that being Jewish is more about culture and ancestry than religion. The survey also found that one in five Jewish people expressed that being Jewish is a combination of religion, ancestry, and culture. There is

no consensus on what defines a person as Jewish.

“I think it’s creating a community of people around you that have similar beliefs and cultural values than it is just about sitting and reciting prayers,” Goldberg said.

One of Shaps’ first experiences with BBYO was her regional induction five years ago. She had sat in a large circle of KIO girls, listening to BBYO’s international recruiter speaking. Each girl had a candle sitting in front of them. A hush fell over the room as the inductees waited to be called up. Hearing her name, Shaps stood in the middle of the circle holding the small, white candle. BBYO’s recruiter banged a gavel, declaring Shaps’ new status.

“That’s what connects us all together.”

Spring Convention - On March 26, Jewish teens ranging from eighth to tenth grade from Kentucky, Ohio, and Indiana join together for Spring Convention, an event where BBYO members spend their time together to “gemilut chasadim” — give loving kindness in order to repair the world. Photo courtesy of BBYO.

“By the power invested in me, I induct you, Jenna Shaps, into BBYO.”

Her candle was then lit, the flame sparking into the air. In Jewish culture, candles can be used to represent a transition. The lit candle cradled by Shaps represented the start of her new “life” in BBYO.

“It’s very, very culty. That’s the best way to describe it,” Shaps said with a laugh.

For 16-year-old Jack Kaplin, a junior taking online classes, the induction was a less somber affair. There was a firm no-talking rule, but Kaplin whispered and laughed with those near them.

“I don’t really follow that rule, because I can’t not talk,” Kaplin said.

Although Kaplin maintained a lighthearted persona, their induction was special. When they were inducted, Kaplin identified as male, making them the first boy inducted into the BBGs. The adherence to the traditional ceremony made them feel welcomed and accepted into a community they were first hesitant about.

“I had never done anything like this,” Kaplin said, recalling their first BBYO regional convention.

While their friends recited prayers with ease, the words felt unnatural to Kaplin. They had gone to Hebrew school and had their bar mitzvah at 13, but grew

up in what they describe as a nonreligious household.

Each member of their family expressed their religion in different ways. Kaplin wore the Star of David necklace around their neck as a physical reminder of God. Their father read the Torah, a religious text containing the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, and prayed daily. Kaplin’s older brother was connected to Judaism by the Hebrew words inked into his skin. In eighth grade, Kaplin decided to join BBYO to meet other Jewish teens and connect with Judaism.

“It’s really what I needed, a group of people that don’t judge me for who I am and support me

no matter what. At the time, I was really confused with myself and they made me feel secure,” they said.

In December 2020, Kaplin was navigating confusion about their gender identity. They started going by he/they pronouns but

some friends and family stuck with using “he.”

“When people called me ‘he,’ it just didn’t feel right. I would get uncomfortable,” they said.

Kaplin started identifying as non-binary in April of last year.

Although the journey has not been entirely smooth, they have gotten to a comfortable place with their gender.

“I feel really secure in my non-binary identity, and using they/them pronouns. It just feels right,” Kaplin said.

Around that time last year, Kaplin also started questioning if they still felt connected to Judaism and if they wanted to be Jewish.

“I felt the Jewish community was a community that wasn’t going to accept me. Now, thinking back to it, how would I have known that when I wasn’t putting myself out there in the Jewish community?” they said.

Like all religions, the core values of Judaism differ for each person. Kaplin has encountered accepting teachers and their parents were always supportive. But sometimes the separation between what the older and

in the community, they learned they couldn’t control other people’s opinions, but they could control who they surrounded themself with. Recently, Kaplin has felt a change in view in themself and their peers, especially from incoming members of BBYO.

“A lot of these things aren’t abnormal anymore. If my freshman self saw me now, my freshman self would be judging me like there is no tomorrow. Why do you dress like that, why do you do makeup? My eyes were not opened, and I feel a lot of people’s eyes now are wide open,” Kaplin said.

Kaplin believes this is because teens are having conversations about inclusivity and acceptance earlier in their lives.

of Judaism by meeting with their friends in BBYO while letting go of the idea of “being Jewish enough.”

“I can be Jewish, even though I am not super connected to the religious portion of it,” Kaplin said.

As for Shaps, she is taking the confidence from her leadership experiences to college. She plans to rush a Jewish sorority while continuing weekly Friday night Shabbat dinners with her college’s Hillel, a Jewish campus organization.

“Having the experience to find other Jewish teens in your community is really important and can make you find yourself,” Shaps said.

younger members believe feels vast.

“There is definitely a handful of people that I stay away from,” they said.

When Kaplin started putting themself out there

As a result, youth-led organizations like BBYO are being pushed to reflect on their traditions and evolve them. These new values then go on to shape the Jewish community in Louisville. But even though the community is constantly evolving, certain traditions will always be kept close.

Kaplin plans to stay connected to the culture

In May, Shaps will attend her last BBYO convention where she will speak to younger chapter members about her experience. She already has a long list of members to give her old KIO shirts to, in an attempt to downsize her massive collection.

As a senior, she will blow out her candle, representing how her life in BBYO is ending as she graduates and moves into a new chapter.

”BBYO will stay a place teens can go to celebrate their Judaism. Although denominations, chapter numbers, and cultural values may change, the candle will be lit again for a new week, a new teen, and a new beginning.

Advocacy presents itself in unexpected ways. Here is one family in which it has taken root.

writing by EMERSON JONES & KENDALL GELLER • design by ARI EASTMANFirst, they said that her backpack was too heavy. But the weight of her backpack didn’t explain the trouble swallowing. Or the back pain. Or the dizziness. Or the numbness. Or the memory loss.

Macy Paradis, a 21-year-old student at Georgetown College, had been experiencing random health issues for as long as she could remember. She had trouble swallowing since the fifth grade, which caused her to choke multiple times per day. She had tingling and numbness in her limbs. Sometimes, she couldn’t feel her arms or legs at school and would have to be wheeled from class to class. Then there was the back pain. And the extreme migraines. And the severe dizziness. Plus, there was the time when she blacked out at school and forgot where she was.

The supposed causes of these symptoms varied from expert to expert. One doctor told her that her back pain was caused by the heaviness of her backpack. Another

doctor told her that she had a spinal fracture. Another boiled it down to a sprain in her neck. Macy, who was just 13 at the time, knew the doctors were wrong, but her instincts meant nothing in the face of their cluelessness.

“I was so aggravated. I was like, ‘You’re not listening to me.’ So, I forced him to order me an MRI,” Macy said.

Reluctantly, her doctor agreed. Days later, Macy left school early after her arms and legs went numb, which prevented her from walking properly. Her memory was a bit foggy, but she remembered a phone call from the doctor to her mother.

The doctor told her that she wasn’t coming back to his office. He said that she was going to see a neurosurgeon because of a rare brain condition called chiari malformation.

The concerns of many 13-yearolds revolve around sports, school, and friends. Macy strayed far from these typical teenage standards. While facing her symptoms and

pushing for answers, she developed the maturity and drive of those much older than her in order to reach a diagnosis.

Chiari malformation is a condition in which the brain tissue extends into the spinal cord. Put simply, her cerebellum was falling out of her skull.

“Or, as I like to say, I’m just so smart that my brain got too big and didn’t fit anymore,” Macy said.

The cerebellum, which is the back portion of the brain, controls balance, movement, and coordination. Macy also found out that she had a condition called syringomyelia, which causes cysts full of spinal fluid to form on the spinal cord.

After years of worsening symptoms, Macy finally received answers. Her constant back pain was caused by the cysts that would rub against her spinal cord every time she moved. Since the cerebellum protruded into the cavity where the brain stem was supposed to connect to the spine, the flow of spinal fluid into the brain was blocked and it was being compressed. The constriction of her brain caused her numbness and random tingling, as well as the instances in which she would black out.

Macy received her diagnosis in February 2015. Then, in March of the same year, she had brain surgery. Specifically, chiari decompression surgery. During surgery, her surgeon removed a piece of her skull to widen the hole at the base, which would allow the flow of spinal fluid and relieve the pressure on her brain.

Macy still isn’t sure how long she has had chiari malformation or what may have caused it. Her symptoms progressed quickly, but it is possible that they had been building up for years.

Some known causes of chiari malformation include traumatic

birth and whiplash from car accidents — both of which happened to Macy.

Although there are several known causes of chiari malformation, there is very limited research on it. Located in Akron, Ohio, the Conquer Chiari Research Center (CCRC) works to provide thorough and relevant information on chiari malformation, as well as spread awareness and fund more research. With their findings, they hope to provide insight to those in the medical field in order to reduce false diagnoses and treatments.

Macy has had the opportunity to contribute a sample of her saliva to a study conducted by the CCRC called Chiari 1000. In this study, researchers looked into the genetics of chiari malformation and aimed to create a set of data on chiari patients as a whole. Along with participating in the CCRC’s study, Macy spreads awareness about chiari malformation on her own time. She has a Facebook page called Macy’s Purple Brains in which she posts information about chiari in order to educate her followers. Plus, for Macy’s 21st birthday, she asked people to donate $21 to the CCRC instead of buying her a drink. She also posts updates on chiari research and her own journey regarding living with chiari and life after surgery. However, the CCRC remains one of the only chiari malformation research centers in the nation. The solitude of the research center provokes frustration in Macy. Some of this frustration stems from within her own family. Macy’s sister, 14-year-old Mallory Paradis, has a progressive genetic condition called cystic fibrosis (CF). CF damages the digestive and respiratory systems, which often

results in sticky, thick mucus building up in various organs and areas in the body. For Mallory, her sinuses are the most affected by her CF.

“My sister has a condition that does get worldwide recognition, and then, mine –it’s just this little tiny center in Akron, Ohio,” Macy said.

Macy and Mallory have a unique relationship, partly because they are remarkably different people. These differences sometimes make it hard for the sisters to communicate effectively.

Because Mallory has been diagnosed with a learning disability, it is sometimes hard for the girls to see where the other is coming from.

Despite their differences, Macy and Mallory have a strong sisterly relationship. The two have become closer with age. They also are able to relate to each other more, both having gone through life-changing situations that the average person hasn’t had to endure.

“My sister and I have always been the sick kids,” Macy said.

Even though chiari malformation and CF are extremely different, a symptom of both diseases are headaches. Mallory gets sinus headaches from CF, and Macy gets what are called chiari headaches.

“When I get really bad headaches and when she gets really bad headaches, we’re like, ‘Bad headache? Yeah. Been there before. I know now how that feels,’” Mallory said.

Up until her diagnosis at age nine, Mallory spent years suffering from sinus-related issues. She was constantly out of school because she was sick, but her pediatrician claimed that the root of her problems were a combination of asthma and her sinuses. However, that didn’t sit right with her mom.

“I kept saying, ‘There’s something else wrong,’” Nancy said.

“My sister has a condition that does get worldwide recognition, and then, mine – it's just this little tiny center in Akron, Ohio.”

“Why would she be this sick all the time with just a combination of asthma and her sinuses?”

Because of the immense discomfort Mallory experienced, she visited an ear, nose, and throat physician (ENT) to check on her sinuses. The ENT who conducted the sinus surgery prior to her diagnosis was the first to acknowledge the extent of the damage to Mallory’s sinuses.

“Her very first sinus surgery, which he thought would take 45 minutes, took three hours,” Nancy said. Mallory only got more sick from there.

Nancy and Mallory were frequent visitors to the ER.

During one visit, Mallory was told that she needed to be admitted to the Norton Women’s and Children’s Hospital. At Norton, Mallory was put through numerous procedures, including tests for infectious diseases, an MRI, and a bronchoscopy.

“They just kept saying, ‘She’s a really, really sick little girl, we have to find out what’s wrong with her,’” Nancy said, her voice breaking and eyes welling up with tears.

Finally, the doctors tested Mallory for cystic fibrosis, and years of wondering came to an end. With a clear diagnosis, Mallory began taking medication and seeing specialized doctors.

“Once I got the medication I needed, it got better,” Mallory said.

While neither CF nor chiari malformation have a cure, CF has several medications and devices to treat the symptoms. Sometimes, when Mallory is stubborn and fights her medication, Macy can be hard on her, pushing her to take advantage of the resources that Macy never had.

“It hurts me a little because I don’t have medications to take,” Macy said.

However, Macy doesn’t let her frustration deter her from advocating for CF. She works with the Cystic Fibrosis

“

“I kept saying, ‘There’s something else wrong.’”

-Nancy Paradis, Macy and Mallory’s mother

In preparation for Great Strides, Mallory’s team, “Mallory’s 65 Roses,” hopes to raise $1,000. Great Strides is a Cystic Fibrosis foundation whose mission is to “offer hope to those living with cystic fibrosis.”

Macy has chiari malformation, a disease which, at this time, has no cure or medication available. For Macy’s 21st birthday, she has asked for donations to the Conquer Chiari Research Center.

Foundation, a non-profit organization dedicated to providing the means to find a cure for CF while aiding those with CF across the country. They sponsor the largest CF fundraiser in the country, the Great Strides Walk. The Great Strides Walk for the Kentucky and Virginia chapter of the CF Foundation is held annually at Louisville Slugger Field. Macy and her family participated in the walk once before, but for the

restaurants with a collective goal to raise money for CF research. At this event, Mallory received a plaque and delivered a speech in front of a crowd full of medical professionals, event sponsors, and other attendees.

Even though Mallory and Macy differ in their public advocacy, both of them are strong self advocates.

Before college, Macy’s frequent absences seemed to be a problem for her teachers

misconceptions and ignorance toward her condition forced her to speak up for herself. When she was in fifth grade – which is when middle school starts for Oldham County – a student once told Mallory that she was lucky to be able to miss school frequently.

“I said, ‘I’m not really lucky. I’m usually in the hospital having a tube going down my nose or I’m getting surgery,’” Mallory said. “I literally told the kid, ‘Don’t say that again.’”

These types of students, as well

past two years, the Great Strides Walk hasn’t occurred because of COVID-19. However, Macy is hopeful that there will be a Great Strides Walk this year.

Various obstacles limit Mallory’s involvement in CF activism. She is not very interested in social media, which removes a major outlet of advocacy. Additionally, Mallory isn’t able to be physically present at advocacy events. People with CF have to stay at least six feet in distance from each other. When they get in close proximity, there is the potential for cross-infection of harmful bacteria, which could cause their condition to deteriorate at a faster pace. Because of this, there is usually only one person with CF allowed to be in attendance at many events with CF organizations.

However, Mallory was the chosen honoree for Cure CF Louisville’s 2021 CRAFT Beer and Pizza festival, a yearly event in which people come together to enjoy beer and pizza from local

and peers. She needed time to catch up on work, but there was a constant lack of understanding. She even had experiences with peers and their parents who questioned why she was missing so much school.

“It’s not like my mom was letting me go on a joy ride,” Macy said.

In reality, she was often in the hospital receiving a migraine cocktail because the prescription pain medication she was given for her headaches did not help stop the immense pain. The failure to recognize Macy’s situation forced her to constantly fight for understanding.

Mallory has been placed in similar situations. Often, her peers do not understand her condition and why she has to miss a lot of school. Mallory currently attends Pitt Academy, a special education school in Louisville. Before Pitt, Mallory was a student at Oldham County Middle School. There, she had troubles with the students as well as the teachers, whose

as Oldham County’s prioritization of Mallory’s attendance over her health, is what ultimately pushed Mallory and Nancy to make a change.

“And after that I was like, ‘I’m out of here,’” Mallory said. “And then I went back to homeschool and then tried middle school again and then got out.”

Educational environments aren’t the only places Mallory has had to use her voice. Now that she is 14, she is able to attend regular doctor’s appointments by herself once a year. The purpose of this is to prepare young people for attending adult clinics and being able to speak for themselves in a medical environment.

“It was unnerving at first, you know? Cause I had to fill out some papers and I had to spell out my school name and I’m just like, I don’t know how to spell it,” Mallory said.

Even outside of her one-onone doctor’s appointment, Mallory is getting better at identifying her pain and telling people what she needs and when she needs it.

“

“I said, ‘I’m not really lucky. I’m usually in the hospital having a tube going down my nose or I’m getting surgery.’ I literally told the kid, ‘Don’t say that again.’” -Mallory Paradis, 14

“She even told me that things are starting to click. She knows, ‘Okay, I have this pain. I think I need to go back to physical therapy,’” Nancy said.

Mallory also advocates for herself in terms of medication. Her seven surgeries speak to the severity of her sinus issues. Finding medication to mitigate these problems is especially difficult, but in October 2019, she started taking Trikafta, a medication used by people with CF that Mallory found incredibly helpful to her sinuses. However, one of Trikafta’s side effects that Mallory found herself experiencing was depression. She no longer participated in activities that made her happy.

“When I was taking it, I was just really sad and I didn’t draw or call my friends,” Mallory said.

So, in February 2020, Mallory stopped taking Trikafta, which reversed the medicine’s positive effects on her sinuses. But, in October 2021, with the extreme adverse effects, and the changing weather that was occurring at the time, Mallory knew she needed to give it another go.

“I woke up one day and I said to my mom, ‘I wanna try Trikafta again,’” Mallory said.

Not only is Mallory able to address her pain, she knows how to communicate it to others in order to get the help she needs. All of her doctors have told her that she is incredibly descriptive with her pain, which makes it easier to diagnose and treat her.

“When I’m in pain, I say it feels like a nail along with a sharp rock and a knife are going at my sinuses,” Mallory said.

She is usually able to point out her pain for her doctors. When Mallory came down with a severe case of the flu, she drew a line from her finger to her throat in order to demonstrate her pain. Immediately, her

doctors knew what she was referring to and treated her for the virus. These abilities in both Mallory and Macy can be traced back to their mom.

Nancy is constantly looking to Mallory and Macy to be self advocates, and to speak up for themselves, whether that be in school, at home, or in doctor’s offices. She encourages Mallory to identify and seek help for her pain and stood behind Macy when she pushed for her diagnosis.

Nancy’s sole focus is on her daughters. Her Instagram is full of educational and awareness posts about CF, as well as chiari malformation. Her inbox is filled with emails from various organizations and she spends her free time reading about new discoveries within the fields of Mallory and Macy’s respective conditions. Along with Macy, Nancy is heavily involved with the CF Foundation, as well as the CCRC. She also works closely with Cure CF Louisville. On top of that, she runs a Facebook page similar to Macy’s Purple Brains called Mallory’s 65 Roses, where she posts about new happenings in the CF community, various fundraisers, and updates about Mallory’s health. Even though she is fully committed to this lifestyle, it isn’t what Nancy had in mind when she pictured being a mom.

No one can plan for the things that life has in store for them, and Nancy’s expectations for parenthood strayed far from what she imagined.

“She’s probably gonna be a cheerleader. And she’s gonna date someone from the football team,” Nancy said, referring to her presupposed vision of Macy’s life. “And she was totally opposite. She was academic.”

As Nancy’s vision of life may have changed over time, her teaching of self advocacy has allowed for her girls to reach

places in their lives where they can envision their own futures.

Mallory is at a place where she can explore her passions and pursure new interests, including her love of history.

“I wanna be a reenactor to wear the fancy dresses,” Mallory said.

While Mallory still has years of schooling to go through, Macy is planning her future now, through her college education.

“I know I want to go into the forensic field,” Macy said.

In regard to her advocacy, Macy plans on continuing her efforts to inform people on chiari malformation and CF. Macy and Nancy both emphasize that an important facet of advocacy is that people need to understand what they are advocating for. As Macy enters new chapters of her life, her fouses may grow beyond a heavy commitment to advocacy. As people continue the conversations about chiari and CF, Macy hopes someone can step up and assume her role.

“I’ve done what I need to do,” Macy said, “I can pass the baton to someone else.” •

“I’ve done what I need to do – I can pass the baton to someone else.”

-Macy Paradis, 21