Letter From the Editors

Student-led publications often grapple with the same issue: Balancing the many responsibilities that come with attending school while trying to produce authentic, moving stories at the same time. This year was no exception for Ethos. We’re committed to uplifting marginalized voices in a thorough manner, however, in the face of staff turnover — we had to adapt. There wasn’t a spring edition of Ethos, but since then, we’ve coalesced and even expanded.

For the first time, two stories featured in our summer edition are also available in video format. But don’t worry, you’ll still be able to snag a hard copy on campus! As Ethos always has, we’re experimenting and working to make our content more accessible while preserving our roots in social justice and creativity. Ayla and I, the new Co-Editors-in-Chief, want to applaud all our staff for making this edition possible and staying patient amidst a fluctuating timeline. With that, here’s what to expect in Ethos Summer 2024.

In our cover story “Growing the Grove Garden: The Need for Intentional Communities,” writer Lily Reese explores how campus expansion threatens spaces for students, beginning with the Urban Farm and now the Grove Community Garden. As more college students cope with food insecurity, Reese demonstrates why collective, reciprocal spaces for growing food are becoming more important.

Our Mission

Ethos is a nationally recognized, award-winning independent student publication. Our mission is to elevate the voices of marginalized people who are underrepresented in the media landscape, and to write in-depth, human-focused stories about the issues affecting them. We also strive to support our diverse student staff and to help them find future success.

Ethos is part of Emerald Media Group, a non-profit organization that’s fully independent of the University of Oregon. Students maintain complete editorial control over Ethos, and work tirelessly to produce the magazine.

“Luda Gogolushko and INCLUDAS Publishing,” written by Emily Rogers, dives into the lack of disabled representation in children’s books and the efforts of one UO professor to change that reality, all motivated by her own childhood experiences.

I talk to Oregonians with Long COVID and build on the work of Jasmine Lewin in “The Unseen Impacts of COVID-19.” Alongside debilitating symptoms, those with Long COVID also have to deal with scientific uncertainty and medical gaslighting, forcing them to pursue alternative pathways of care.

Lastly, Ellie Graham’s piece, “Unlocking Potential: UO’s Effort to Close the Gap Between Custody and Learning,” ventures into a place Ethos hasn’t yet — prisons. Graham documents UO’s Prison Education Program, which enables inmates to learn collaboratively with UO students in Oregon State Penitentiary, and how it can break the cycle of recidivism.

We hope that you take inspiration from these stories, learn something and see yourself in Ethos.

Ethos Co-Editors-in-Chief

Ayla Rivera and Nate Wilson

Email editor@ethosmagonline.com with comments, questions and story ideas. You can find our past issues at issuu.com/ ethosmag and more stories, including multimedia content, at ethosmagonline.com.

Sterling Cunio (left), who was involved in UO’s Prison Education Program and now works in social advocacy, performs rap poetry at the art exhibit “HOPE: A Human Right” on March 7, 2024.

Table of Contents

INCLUDAS founder, Luda Gogolushko, is creating media representation for herself and disabled children. 6

12

Changing the Narrative of Disability

20

Unlocking Potential

By bringing classes inside Oregon State Penitentiary, UO’s Prison Education Program is pushing back on stigmas incarcerated people face and improving access to a collegelevel education

Growing the Grove Garden

Threatened by university expansion, the Grove is cultivating both sustainable, much-needed produce and a resilient, creative community

26

The Unseen Impacts of COVID-19

Four years into the pandemic and facing medical uncertainty, Oregonians with Long COVID turn to alternative pathways of care while managing debilitating symptoms

Editorial

Co-Editors-in-Chief

Ayla Rivera

Nate Wilson

Social Media Managers

Maggie Delaney

Social Media Specialist

Fern Peva

Writing

Associate Editor

Bentley Freeman

Writers

Emily Rogers

Ellie Graham

Lily Reese

Staff

List

Design

Design Editor

Sydney Johnson

Designers

Kayla Chang

Mia Pippert

Abigail Raike

Illustration

Art Director

Maya Merrill

Illustrators

Bee Baumstark

Aiko Gaudreault

Mia Pippert

Photography

Photo Editor

Violet Turner

Photographers

Alex Hernandez

Kallie Hansel-Tennes

Fact Checking

Fact-Checking Editor

Elena Nenadic

Fact-Checkers

Aaron Drummond

Aedan Seaver

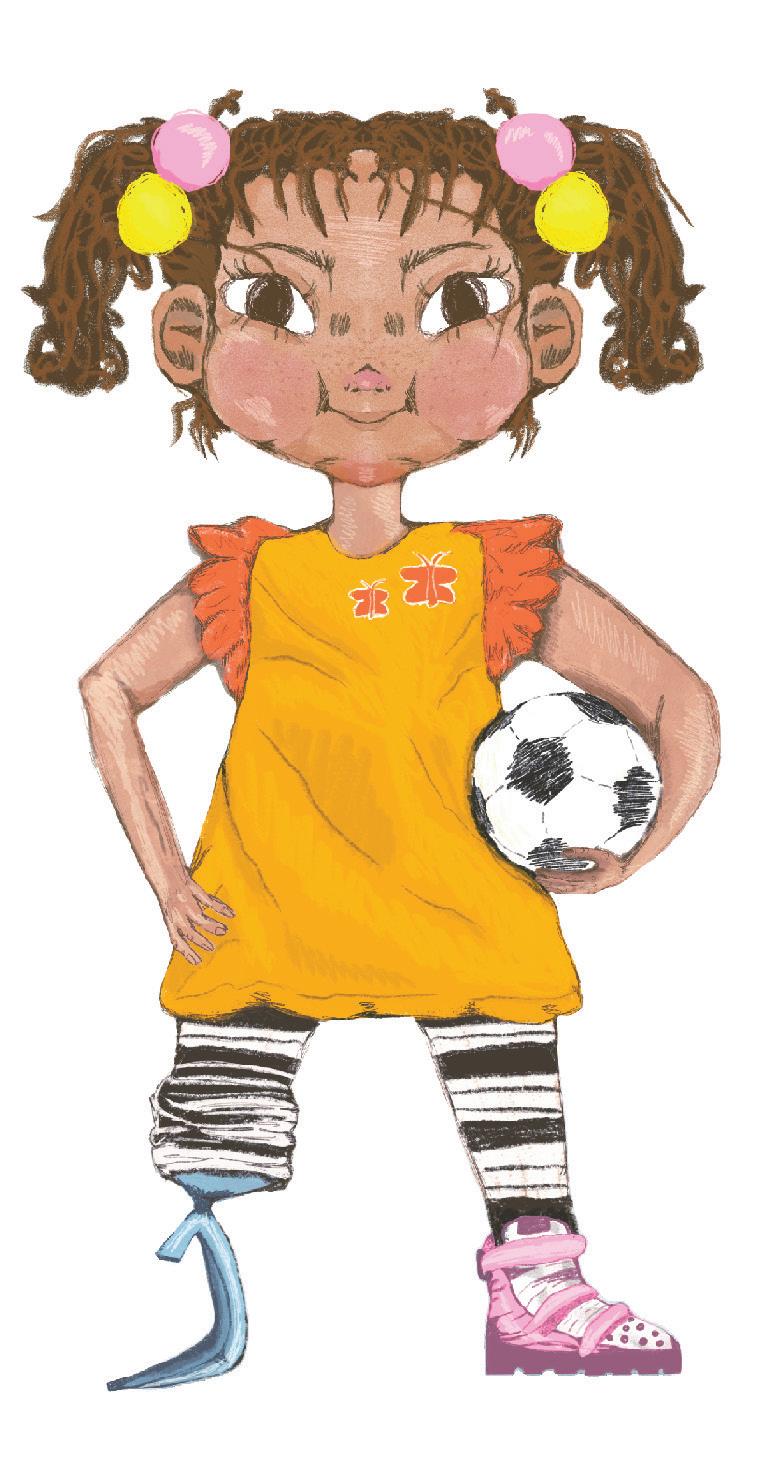

Changing the Narrative of Disability

One Page at a Time

Through writing, researching and teaching, Gogolushko works to ensure that children with disabilities don’t feel isolated or misunderstood, like she did.

Written by Emily Rogers | Photographed by Kallie Hansel-Tennes | Illustratedby Bee Baumstock | Designed by Mia Pippert

In the fantastical literary landscape of children’s books, anything from cats in hats and caterpillars that are very hungry can happen — to an extent. These books blend the imaginary with reality, oftentimes giving human qualities to other-than-human characters, but only those deemed “acceptable” or “normal.” INCLUDAS Publishing, which produces inclusive, diverse children’s stories about disabilities, and its founder, Luda Gogolushko, are changing that narrative.

Gogolushko has spinal muscular atrophy type three, a genetic disease that impairs the nervous system and skeletal muscles. SMA is considered a rare disease that affects approximately one out of every 10,000 people, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“With SMA or muscular dystrophy your muscles weaken over time,” Gogolushko says. “One day I was able to brush my teeth, but then it gets harder and harder and you get weaker, but you don’t notice it.”

In her formative years, Gogolushko faced a cultural medical model that perceives disability as a defect, and for an individual to have a high quality of life — these defects must be cured. Because of this, Gogolushko spent most of her upbringing in doctor’s offices under health-focused scrutiny.

“I think a large part of my childhood upbringing was focusing on the disability aspects, like did I eat healthy today or did I exercise, and I think that took away a lot of the real childhood I wish I had,” says Gogolushko. On the playground, Gogolushko was ignored and rejected. Other children were scared to play with her, and sometimes even parents would tell their kids to stay away.

“It feels like you’re a speck of dust no one can find or cares about,” says Goglushko. “ You feel so invisible.”

However, in a childhood marred by isolation and societal mis conceptions, Gogolushko found solace in television shows with strong female leads like the “Power Rangers” or “Xena the War rior Princess.” “Television was my childhood play, my imagi nary play and my escape from all the medical side of disability,” says Gogolushko.

filled with a lot of harmful disability representation.”

“I’ve had to learn to shift perspectives, and not look at myself as how society views disabilities, but to view myself as a person for who I am,”

- Ludo Gogolushko.

Through wondrous illustrations and colorful words, Gogolushko has invited those with a disability to engage in media where they finally play a positive role. “I think these stories just say that you have a disability, and that’s okay. You do not need to hide it or become nondisabled to fit in,” says Gogolushko. Recognizing how ableism intersects with other forms of prejudice, especially racial discrimination, her books don’t just focus on disability.

“With this last book, I just really had to think about what we are actually not seeing. We’re not seeing black disabled girls in wheelchairs,” says Gogolushko. INCLUDAS released “The Biggest Gift of All” in November 2023 and Melquea Smith, a Black, Queer, multi-award-winning children’s book illustrator, produced its artwork.

Set at a child’s birthday party, watercolors and pastel presents fill the pages. “The Biggest Gift of All” revolves around Tasha, a Black girl in a bright pink wheelchair, who’s determined to give her companion Sam a gift larger than their friendship. Dismayed when her other friends keep bringing bigger and bigger gifts, Tasha feels as though her gift is not good enough. In the end, however, young readers get to learn that true friendship is the biggest gift of all.

Apart from creating children’s books, the publishing agency has recently taken on a new initiative: researching how people view disability representation in the media.

Mira Coles, an undergraduate student at the University of Oregon, interned at INCLUDAS as the education activities coordinator over the summer and has stayed on to do research. Coles was originally drawn to the position for its publishing

experience, not knowing that the agency had a diversity and disability focus.

“I just feel so ignorant when I look back before I never really thought about any of this, and now it’s impossible to ignore,” Coles says. Whenever she watches a movie or picks up a book, Coles now finds herself critically analyzing media using what she learned at INCLUDAS, which she’s grateful for.

Alongside Coles, Gogolushko is conducting interviews with disabled and non-disabled individuals regarding their feelings towards disability representation in the media. Recently, they have been talking to the Accessible Education Center, SOJC professors and more to promote the research. Their goal is to get 30 interviews by the end of spring term, and have just finished their pilot beta test for research.

Outside of being a publisher and researcher, Gogolushko is also a graduate teaching fellow at UO where her advocacy for the disabled community transcends beyond the pages of her books. Winter term of 2024, she taught Disability and Media Technology, a class that focuses on how media technology often shapes and reinforces discriminatory practices because disabled people are frequently excluded from the design process.

Both through INCLUDAS and at UO, Gogolushko has been able to rewrite the narrative for not only the disabled community, but also, herself.

“I’ve had to learn to shift perspectives and not look at myself as how society views disabilities, but to view myself as a person for who I am,” says Gogolushko. “Writing is like my therapy.”

The Need for Intentional Communities

Threatened by university expansion, the Grove is cultivating both sustainable, much-needed produce and a resilient, creative community.

Written by Lily Reese | Photographed by Alex Hernandez Illustrated by Mia Pippert | Designedby

Kayla ChangWalkingdown Moss Street into quiet, sloping East Campus, a mini library and arches mark the Grove Community Garden. Entering on newly mulched paths, you’ll pass raised beds, a camper van full of supplies and the garden cat GG who welcomes everyone and anyone. With fresh soil and herbs hanging heavy in the air, laughter and questions swirl around a small community farm just blocks away from the bustle and stress of campus.

Amidst the limited spaces available for intentional communities and ongoing initiatives by the University of Oregon to reclaim such areas, there is a concerted effort to expand spaces for students. One such effort is growing the Grove Garden. Led by the Student Sustainability Center, it aims to not only provide students with valuable gardening experience, but also establish a reciprocal environment where students contribute to the land and actively nourish the wider community.

However, spaces like the Grove Garden are not permanent, and the $225 million building overshadowing the Urban Farm symbolizes that reality. Since 1976, students and locals alike have cultivated kale, sunflowers, asparagus and several other plants at the Urban Farm, just across Franklin Boulevard. Now that drills and saws shriek through the air, meeting on the farm requires yelling over the sound of construction — a sad

173,000-square-foot bioengineering building, and share this information with the UO community, but transparency proved difficult. Formal design plans were supposed to be available following a UO Campus Planning Committee meeting on April 29, 2022; however, discussion about Phase 2 was removed from the meeting agenda.

Madison Sanders, an organizer of Save the Urban Farm and UO student who sits on the Campus Planning Committee, says Phase 2 could have been removed from the meeting agenda for many reasons, such as scheduling conflicts or the design team needing more time to finalize plans. Still, she says obtaining clear answers was a challenge, as previously reported by Ethos.

Throughout the vibrant spring and sun-kissed summer months in Eugene, the coalition gathered testimonies and ignited rallies, each echoing the Urban Farm’s verdant beauty. Despite their campaign, they witnessed no progress. Construction began under floodlights at 4 a.m. on Dec. 19, 2022 — weeks ahead of what was told to supporters, continuing on and around the Urban Farm to date.

All told, university encroachment caused the loss of 35 orchard trees, around a dozen Port Orford Cedar Trees and 40% of the farm’s plantable garden beds. While a place for holding classes,

The Grove Community Garden, located between 17th and 18th Avenue on Moss Street, offers a space for students to learn about farming, get their hands in the dirt and cultivate produce for themselves.

Valentine Bentz, a junior at UO and Growing Grove Garden lead, speaks at the work party on Feb. 24, 2024.

Valentine Bentz, a junior at UO and Growing Grove Garden lead, speaks at the work party on Feb. 24, 2024.

Work Party: Student volunteers lay down mulch paths, prepare plant beds and tidy up the Grove Garden on Feb. 24, 2024.

THE UNSEEN IMPACTS OF COVID-19

Four years into the pandemic and facing medical uncertainty, Oregonians with Long COVID turn to alternative pathways of care while managing debilitating symptoms

Written by Nate Wilson | Photographed by Kallie Hansel-Tennes | Illustrated by Maya Merrill | Designed by Sydney JohnsonOne morning in July 2020, psychotherapist Christa Hines overslept her first appointment of the day. When Hines woke up, the right half of her face felt droopy, her mind clouded and her right arm was heavy as lead — all symptoms of a stroke.

But Hines didn’t have a stroke. Soon after the scare, she consulted a neurologist who diagnosed her with postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, a form of dysautonomia common among people who have Long COVID.

Fueled by the latest omicron variant, JN.1, the U.S. experienced one of its largest surges in COVID-19 infections at the beginning of 2024, according to wastewater data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Although Oregon’s virality rate was less than half of the national average, nearly one in six Oregon adults who contract COVID-19 also experience Long COVID as of March 2024.

Long COVID is a multisystemic condition that persists for months or years after an acute COVID-19 infection and has over 200 identified symptoms. According to a study by the Patient-Led Research Collaborative, Long COVID impacts the nervous system, causing dizziness, memory loss and irregular sleep; the heart, resulting in chest pain and palpitations; the respiratory system, leading to coughing and shortness of breath; the stomach, manifesting as nausea, abdominal pain and loss of appetite; the reproductive system, causing erectile dysfunction and irregular menstruation; and several other organs.

Four years into the pandemic, few protocols for diagnosing and treating Long COVID exist. Gina Assaf, a co-founder of PatientLed Research, says scientists have several hypotheses on what causes Long COVID, including immune system dysfunction where the body either fails to eliminate the virus or produces an excessive immune response causing organ damage, but that these theories haven’t been confirmed yet.

“I had to relearn how to sit up, hold my head up and walk again,” says Hines. With dysautonomia, the basic functions of her nervous system, like regulating blood pressure and digestion, do not work properly and, because of POTS, her heart rate skyrockets whenever she stands upright. Once able to bike from Portland to Seattle, Hines now struggles to stand in line at the grocery store as a result of Long COVID and the many chronic conditions tied to it.

However, she didn’t always have that medical clarity. Hines first tested positive for COVID-19 in April 2020, but despite having extreme fatigue, lightheadedness and other neurological problems for months afterward, she says that doctors routinely dismissed her symptoms — Hines’ neurologist only diagnosed her with POTS and dysautonomia after she made the discovery herself.

“A lot of people were feeling quite isolated, not understood by their doctors and really challenged by the loss of their functioning level,” says Hines. Recognizing the need along with her unique background in trauma treatment and nervous system regulation, Hines created an online support group for “long haulers” in Oregon and Southwest Washington, or people with Long COVID since 2020.

Emma Smith, who first contracted COVID-19 in November 2020 and is now 25 years old, joined the group in March 2023. By that point, Smith had seen ten different doctors, quit her job at Freestone Climbing Gym in Missoula, Montana, and moved back home with her parents in Portland. At Smith’s first meeting, she listed off her symptoms. With each one, group members responded, “I have this too. You’re not alone.”

“When you’ve been sick for so long and you’re so young, to get validated and be heard like that,” Smith says, “I could start to breathe again and feel better that I’m not dying — I just have something terrible caused by a virus.”

Smith has myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome, another chronic condition prevalent among people with Long COVID. With ME/CFS, Smith experienced periodic post-exertional malaise crashes that left her bedridden for a week or longer if she spent just a few hours climbing. After her second infection in July 2022, Smith’s symptoms worsened and she developed new ones: weakness and tremors in her limbs, weekly migraines and visual problems like seeing flashing lights or floaters in her eyes.

Although unvaccinated older people have a higher risk of developing Long COVID, as with Smith, Long COVID impacts even the young and able-bodied. One study found that women are 1.5 times more likely to develop Long COVID than men and, compounded with disparities in healthcare access and education, women of color are especially at risk. Moreover, contracting COVID-19 multiple times increases the likelihood of death, hospitalization and severe damage to organ systems.

Like Hines, Smith didn’t initially understand what was happening to her body — and neither did her doctors. Five different medical professionals told Smith that her physical symptoms stemmed from anxiety and depression. Smith tried three psychiatric medications to no avail. This persistent “medical gaslighting” left Smith utterly confused and caused her mental health to deteriorate: She fought suicidal ideation for four months, eventually ending up in a mental health crisis center in February 2023.

“When you’re in your twenties and you go to the doctor, you put a lot of trust in them,” says Smith. “My body was screaming at me, and to be told by these doctors that it was all in my head — that I just needed to power through it — was very invalidating and traumatizing.”

“There’s this assumption that doctors should know everything, and when they don’t, some behave in ways that I could consider

gaslighting,” Assaf says. Many participants in her studies with Patient-Led Research also experienced medical gaslighting, and Assaf emphasized it was most common among women and people of color.

A few weeks following her release from the crisis center, Smith came across a Washington Post article discussing the relationship between Long COVID and ME/CFS. Over two years after her initial infection, Smith diagnosed herself with Long COVID. With the support group, though, Smith finally had a community who shared her frustration — the feeling of questioning herself — and who amassed a heap of useful resources.

The group divulged several strategies to help Smith manage her chronic fatigue, including pacing. Intended to reduce the severity of PEM crashes, Smith now chooses what activities she hopes to accomplish any given day, and if she starts to get fatigued, she rests instead of trying to push through them. By actively listening to her body, Smith only needs to rest a few days rather than a week after a bad crash.

For Hines, seeing a naturopath brought her the most relief. In her experience, naturopaths take a bottom-up approach to medicine by first identifying the root causes and then moving outwards. “That is the best practice when it comes to treating post-viral conditions which are complex and multisystemic in nature,” says Hines.

pain, hyper flexibility and weakens skin strength, she depends on a walker to move around and a wheelchair for longer distances. At 3 a.m., Rusthoven folds out her shower chair and adamantly does her makeup afterward.

“I’m really stubborn. I don’t want to lay in bed all day and complain,” Rusthoven says. “I want to try and feel good about myself.”

It’s been over four years since Rusthoven first contracted COVID-19. Since then, she’s lost her job, gotten her car repossessed, had to sell her house and given up custody over her 15-year-old daughter because she couldn’t provide care and manage her Long COVID symptoms at the same time — this is Rusthoven’s new normal.

Even with her medications and cannabis, she still deals with a significant amount of daily pain, depends on constant support from her husband and usually can’t make it past 10 a.m. without lying down. But Rusthoven, like Hines and Smith, found additional help at Oregon Health and Science University.

“...TO BE TOLD THAT IT WAS ALL IN MY HEAD — THAT I JUST NEEDED TO POWER THROUGH IT — WAS VERY INVALIDATING AND TRAUMATIZING.”

However, because Long COVID causes such a wide array of symptoms, each of which varies by individual, even a dedicated support group that knows a great deal about what to do or who to see can provide so much help.

- EMMA SMITH

Emily Rusthoven, a former nurse who recently moved to Eugene from southern Iowa, actively uses cannabis to manage her terminal pain and many chronic conditions: She has gastroparesis, EhlersDanlos Syndrome and Mast Cell Activation Syndrome along with dysautonomia and POTS.

“It’s nice to connect with people and talk about how we’re all feeling, but a lot of them have different issues than I do,” Rusthoven says. “I feel out of place.”

Every day around 4 p.m., Rusthoven sorts through and takes over 30 prescribed medications. Soon after, she eats dinner through a feeding tube because of her gastroparesis, a disorder that essentially stops digestion and causes severe abdominal pain. Sometimes Rusthoven’s husband carries her to bed due to the extreme fatigue and discomfort that follows eating.

Now an insomniac, Rusthoven generally starts her day at 2 a.m. With EDS, a genetic connective tissue disorder that induces joint

The doctors at OHSU’s Long COVID Clinic have worked with over 3,500 referred patients since its inception in March 2021, and is one of few places in Oregon that offers specialized Long COVID care. Recognizing the multisystemic nature of Long COVID, the clinic provides pulmonology, cardiology, neurology, primary care and physical rehabilitation services, among many others.

According to Dr. Aluko Hope, an associate professor at OHSU and medical director of the clinic, their treatment approach begins with listening to and validating patients. Their next step is communicating the complexity of Long COVID, how each case requires a unique plan and what patients need to know in the absence of federally approved treatments.

“The expectation that patients have about recovering from an illness is one that comes from a fiction where doctors figure out what’s wrong with them, give them a pill and they suddenly get better,” says Dr. Hope. “That’s not something available to us with Long COVID.”

While COVID-19 is still relatively novel, chronic conditions like dysautonomia and POTS have been around for decades. As Assaf explained, scientists have historically ignored researching and developing treatments for these disorders, advancements that could have been critical in mitigating Long COVID. According to the American Autonomic Society, the number of medical professionals familiar with POTS was already insufficient prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and now there is a dire shortage.

“They don’t have a solution. They don’t have a medication they can give you,” Smith says. “Pacing is great, but it goes against every strand of my DNA — I was an athlete and I want to keep pushing my limits, I don’t want to pace.” While grateful for tailored care and more understanding doctors, Smith just wants to heal.

Patients turning to support groups rather than doctors. Lack of scientific knowledge and treatment options. Medical neglect that stretches far past March 2020. For Assaf, these factors point to a new paradigm — one that situates patients at the forefront of research and learning.

“With any new or misunderstood illness, the people best suited to lead and drive are people that are having the lived experience,” says Assaf.

Patient-Led Research, headed by five women who all have Long COVID, epitomizes this model, and OHSU recognizes the need for patient input too. In September 2022, OHSU launched a virtual education series on Long COVID as part of Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes), a program that informs medical providers on specialized health conditions, specifically those caring for rural or other underserved communities.

“There’s a broad concept of who the experts might be, which allows the people learning to get a full sense of how to approach these complex cases,” says Dr. Hope. “It’s a bidirectional process where everybody grows and gets better from these kinds of interactions.”

Hines served as the patient representative for several ECHO presentations, during which she shared her experience with Long COVID and felt responsible to advocate for others. Having facilitated dozens of support group meetings, Hines couldn’t help but think about the many stories of people being lost in our medical system and utterly incapacitated by an invisible illness.

The U.S. and Western states experienced one of its largest surgest in COVID-19 infections at the beginning of 2024 while Oregon peaked in August 2023. Wastewater data, or the testing of sewage to detect traces of infectious diseases, is one of the only available metrics to track COVID-19 severity. (Data Courtesy of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

OHSU is also participating in two clinical trials funded by the National Institutes of Health as part of its RECOVER (Researching COVID to Enhance Recovery) Initiative. One trial will test whether PAXLOVID, an antiviral drug already used by people infected with COVID-19 who have a high risk for hospitalization or death, can also treat Long COVID patients. The second will explore different interventions, such as brain training and stimulation, designed to mitigate the cognitive dysfunction associated with Long COVID.

The NIH devoted $515 million to its RECOVER Initiative in February 2023, but developing a concrete treatment for Long COVID will likely take years, all the while public health guidelines continue to erode. On March 1, 2024, the CDC declared that people who test positive for COVID-19 no longer have to isolate for five days, and the federal government suspended its free athome COVID-19 test program shortly afterward.

There are 38 million U.S. adults living with Long COVID and around 485,000 in Oregon, according to a Statistica survey conducted in July 2023. Those figures have undoubtedly increased since, but Pew Research recently found that only 20% of Americans view COVID-19 as a major threat to public health.

As much as we want to find normalcy again, COVID-19 is still with us and millions suffer from debilitating, persistent symptoms that don’t have a cure. For those with Long COVID, returning to normal isn’t an option.

“Now, I don’t think I would be a nurse again, even if I could physically do it,” says Rusthoven. “It feels like everyone forgot about people with Long COVID.”

“We all feel isolated, lonely and abandoned by the world because everyone is moving on from COVID-19,” Smith says. “Yet we’re still here dealing with the ramifications of our infections.”

Since Day 1 over 100 years ago, student team members have been an essential part of our team. Their time with us ranges from seasonal to part-time and more, providing them with new skills and perspectives, and preparing them for a future beyond The Duck Store.

We’re proud to be a part of our team members’ University of Oregon experience, championing their potential both now as students and into their futures. Join us in celebrating our graduating team and Board members at tds.tw/tdsgrads24

UNLOCKING POTENTIAL:

UO’S EFFORT TO CLOSE THE GAP BETWEEN CUSTODY AND LEARNING

By bringing classes inside Oregon State Penitentiary, UO’s Prison Education Program is pushing back on stigmas incarcerated people face and improving access to a college-level education

Written by Ellie Graham | Photographed by Alex Hernandez | Illustrated by Aiko Gaudreault Designed by Abigail RaikeOpportunities feel slim sitting in a cell, waiting for the day of release which could be weeks from now — or years. Two inmates, escorted by a guard, walk down a dark hall until they approach yet another metal, secured doorway. On the other side, 14 UO students, a professor and 12 other prisoners await, all eager to learn collaboratively. Established in 2007, UO’s Prison Education Program offers incarcerated people hope through education.

“Love and education were the two most transformative forces in my life,” says Sterling Cunio, who was sentenced to life without parole at the age of 16. Upon his release two years ago, Cunio walked out of Oregon State Penitentiary with a bachelor’s degree.

The U.S. incarcerates more people than any other developed country. The national prison population exceeded 1.2 million people in 2022, according to a report by the Bureau of Justice Statistics. Among U.S. states in 2023, Oregon had the 27thhighest incarcerated population with 13,198 people in custody.

Over one in five state prisoners don’t have a high school diploma or an equivalent, according to the Oregon Department of Corrections. While several factors hinder reintegration after release, criminal justice researchers have long noted that poor educational

opportunities increase recidivism: Improving accessibility is critical to disrupting “the revolving door” of the carceral state.

UO’s PEP is pushing to remediate these systemic flaws by bringing classes to inmates, providing enrollees the opportunity to acquire college credits or a degree and improving their well-being before release. “Inside” students must have a GED to ensure they can excel in higher-level classes. For “outside” students, they need to apply for the Salem-based program as space is limited.

Held every week, insideout classes prioritize peer collaboration — both groups lead discussions and learn from each other. Outside students are also given a tour of and exclusive access to the prison, which helps diffuse stigmas and preconceived notions about incarcerated individuals.

“There are many aspects of learning that aren’t captured by a grade and the number of credits on a transcript,” says Shaul Cohen, the program director of PEP. “We’re able to engage with the people who are incarcerated and the students in the prisons in different ways. Inside-out in singular, brings together those two groups.”

Miriam Yousaf, a current PEP intern and UO student, emphasizes how outside students provide inside students with human connection, which she views as critical for people in isolation.

UO undergraduates speak with Sterling Cunio (right), one of the former “inside” PEP students, at the art exhibit “HOPE: A Human Right” on March 7, 2024.

Inmates produced all art featured at the “HOPE: A Human Right” exhibit in the Erb Memorial Union. Sponsored annually by UO’s PEP, the gallery visualizes the psychological impacts of incarceration and allows inmates to engage creatively.

Shaul Cohen, the program director of UO’s PEP Program, attends the art exhibit “HOPE: A Human Right” on March 7, 2024.

Through PEP, Cunio received his bachelor’s in social sciences and served on the steering committee, which shapes the program and works to improve the service they deliver. He continues to write poetry, which he delivers in rap form, and recently accepted an invitation to speak at the White House for the National Endowment of Arts. Cunio also works with nonprofits in Portland to shape social justice programs and is preparing for his upcoming podcast release, “Cellblocks to Mountaintops.”

“The more information you have, the more ideas you have,” says Cunio. “The more I understood some of the system or structural constraints, I could also start thinking of how I could do differently myself because I would see other things and learn about them.”

specific subject areas such as geography and conflict resolution. For Rise, a key strength of PEP is that inside students can take classes even if they aren’t pursuing a bachelor’s degree.

“All the students are much older than me with very different life experiences,” says Rise. “But I tell you what, they were there to learn. They were eager.”

PEP doesn’t conduct research on inside students, but they monitor progress and hold dialogue with them. The steering committee is responsible for examining relevant adjustments to the program based on participant feedback. According to Cohen, several people remain engaged with PEP post-release, like Cunio.

AJ Rise, an instructor at UO, has taught math inside the prison for over a year. To foster interdisciplinary learning, PEP offers other core courses like english and science, along with more

Outside students share a similar passion. Hannah Bland, a Portland-based clerk for the prison program, entered PEP as an intern and decided to attend UO because of the inside-out program. Bland appreciates how the inside-out classes humanize inside students and provide outside students with a unique learning experience.

“You get to talk about things that are deeper than your everyday reality, that’s why I’m really glad we have classes that are beyond just criminal justice issues,” says Bland. “The most avid Chinese literature and Russian literature scholars are prisoners and so it’s the opportunity to talk about things that are outside of the norm.”

Although PEP primarily seeks to nurture a love for learning, several studies indicate that prison education can have other tangible payoffs. “There’s national data about the value of

education and lowering recidivism. And we have every reason to believe that we’re at least as good and probably better than that data shows,” says Cohen.

Apart from offering classes in the penitentiary, PEP also sponsors an annual exhibition featuring artwork produced by inmates. This year’s collection, called “HOPE: A Human Right,” is on display at the Erb Memorial Union and illuminates the psychological impacts of incarceration. When the exhibition concludes, some of the artwork is donated by inmates and sold at First Friday and Midtown Art Center in Eugene, proceeds from which get funneled back into PEP.

“Art is many things. For me, it is an expression and therapy in these dark times behind these walls. Remember: It’s not what you know but what you don’t know and what you’re willing to understand,” writes an incarcerated artist named Shawn. The piece, titled “Skull (Rage),” depicts an elaborate skull with darkened eyes, melting teeth and is shaded with pencil to convey the internal conflict that comes with enduring a prison sentence.

Tracey Hightower, education and training administrator for the Department of Corrections, speaks to the enthusiasm surrounding the annual art display. “As soon as this one’s over and they’re finished, they’re already starting work on some of their next projects to turn in for next year,” says Hightower.

The art exhibition and PEP have a lot in common — carving out opportunities for inmates to prosper, increasing awareness about the injustice of incarceration and working to break that cycle.

PEP has provided structure and support to incarcerated peoples’ lives. Being introduced to education and fostering a

positive learning space has helped many see a light at the end of the tunnel, according to Cohen.

Cohen says extending education to as many incarcerated people as possible, goes beyond just earning a degree.

If socIety wants to end recIdIvIsm, they’ll educate,

- Sterling Cunio

“We’re certain that the benefit of what we do is broader and, in some ways, more significant even than having a narrow cadre of people,” he says. “A cohort earning a credential has a much broader impact and we’re committed to that.”

Rise plans to instruct math at the prison for as long as the governing body will allow him. “This is easily the most fulfilling type of teaching that I’ve ever done,” says Rise. “It’s just incredible. I’m so lucky to be a part of this program.”.

Education is a privilege, but PEP continues to expand opportunities to some of the most marginalized and overlooked people in Oregon.

“If society wants to end recidivism, they’ll educate,” Cunio says.