Tackling Patriarchy

How a local women’s football team breaks barriers and builds community.

How a local women’s football team breaks barriers and builds community.

t is bittersweet to write this, the last letter from me to you where I can call myself editor. But, really, the sweet outweighs the bitter. I could not be more proud of this edition and all the growth it represents.

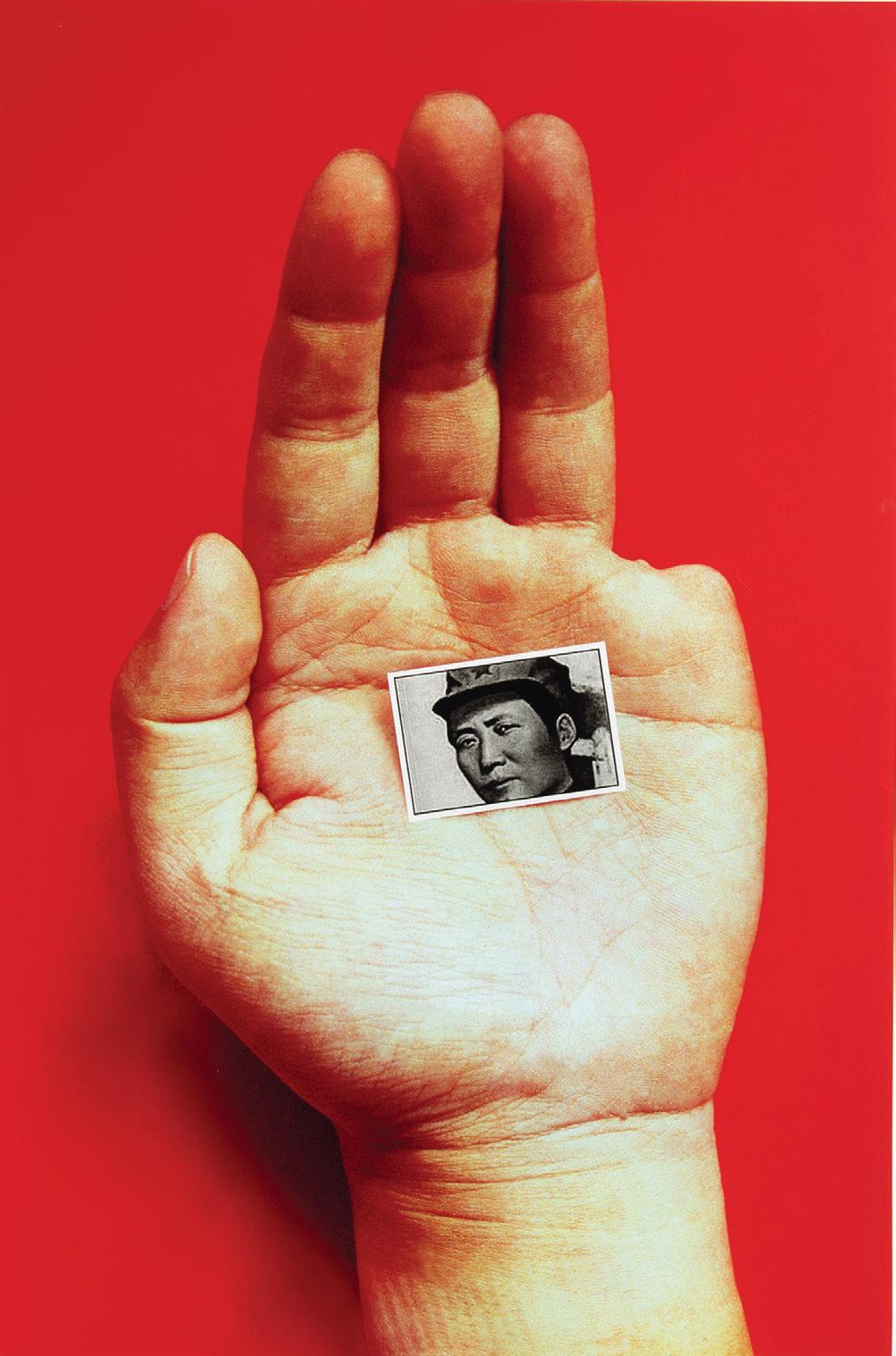

Ayla Rivera’s striking photograph of Oregon Cougars quarterback Billy Jene Meza is this edition’s cover. Not only is this photo story a well-crafted look into an underrepresented group (women in tackle football), it is a culmination of Ayla’s work throughout the year. Ayla has been a reliable talent since she joined the staff last June, and she has invested in growing as a photographer each publication. She’s volunteered her time to share Ethos with the community. Each player highlighted in the photo story “Tackling Patriarchy” is an important part of Ethos and all we stand for, and Ayla is, too.

Daniel Friis is another staff member who joined last June, and his writing has grown so much this year. His story, “Unionizing for Change,” zooms out on student worker union activities that have taken the unionization movement from a group of about a dozen to about 3,000. The undergraduate student union movement at the University of Oregon joins movements at colleges nationwide, though UO has a much larger student body than Grinnell University and Kenyon College, two campuses with established undergraduate student workers unions. I personally reported on the student workers union for the Daily Emerald back when it was still about a dozen folks, and seeing the follow up Daniel has done warms my heart.

The rest of the stories you’ll read in this edition come from writers who joined just a few months ago. They represent the ever-changing staff makeup of this magazine, and all the talent and potential that brings.

“A Commitment to the Struggle,” written by new staffer Emily Rogers and photographed by veteran Sammy Karambelas, tells the story of the first Muslim American federal magistrate judge, Mustafa Kasubhai. The UO law school alumnus advocates for trans rights in the courtroom, starting with not assuming the gender identity or pronouns of those in a case. Kaia Mikulka, who joined the Ethos staff in the winter, created a beautiful, courtroom-style illustration capturing Kasubhai’s amiable nature, his work towards equity in the courtroom and his status as the first Muslim American federal magistrate judge. It is Ethos’ mission to elevate and honor the voices of those in marginalized groups, and this story highlights somebody who does just that.

In a time when faith in journalism is fading, we want our community to know our names. If you want to get to know Ethos better, visit our social media to see staff highlights and behind-the-scenes content. Or, shoot me an email!

As always, thank you for reading. Please continue to see yourself in Ethos.

Abby Sourwine

Ethos Editor-in-Chief

Ethos Editor-in-Chief

Email editor@ethosmagonline.com with comments, questions

and story ideas. You can find our past issues at issuu.com/ethosmag

and more stories, including multimedia content, at ethosmagonline.com.

Our Misson:

Ethos is a nationally recognized, award-winning independent student publication. Our mission is to elevate the voices of marginalized people who are underrepresented in the media landscape and to write in-depth, human-focused stories about the issues affecting them. We also strive to support our diverse student staff and to help them find future success.

Ethos is part of Emerald Media Group, a non-profit organization that’s fully independent of the University of Oregon. Students maintain complete editorial control over Ethos and work tirelessly to produce the magazine.

After recent rent hike increases at the Eugene Hotel, seniors are looking for affordable housing elsewhere, some moving hours away to find it.

Catie Cooper, a sophomore at the University of Oregon, is raising money for Huntington’s Disease through fundraising on the EMU green.

How a local women’s football team breaks barriers and builds community.

The reality of living in one of Eugene’s most curious co-ops, and what it takes to leave.

University of Oregon student workers are making history as they work to create a better future for themselves.

Mustafa Kasubhai almost didn’t take the bar. Now, he is creating new standards for the judicial system.

Editorial

Editor-in-Chief

Abby Sourwine

Managing Editor

Ella Hutcherson

Writing

Associate Editors

Maris Toalson

Kendall Porter

Writers

Ayla Rivera

Milli Hopkinson

Mirandah Davis-Powell

Emily Rogers

Megan McEntee

Daniel Friis

Illustration

Art Director

Maya Merrill

Illustrators

Miles Imai

Soon Lee

Kaia Mikulka

Photography

Photo Editors

Ilka Sankari

Wesley Lapointe

Photographers

Violet Turner

Samantha Karambelas

Ayla Rivera

Paris Snider

Sophie Fowler

Riley Valle

Design

Design Editor

Savannah Zerbel

Designers

Lynette Slape

Kaia Mikulka

Kayla Chang

Miles Imai

Socials

Social Media Manager

Whitney Conaghan

Social Media Specialist

Maggie Delaney

Fact-Checking Editor

Bentley Freeman

Fact Checkers

Nate Wilson

After recent rent hike increases at the Eugene Hotel, seniors are looking for affordable housing elsewhere, some moving hours away to find it.

Written by Mirandah Davis-Powell | Photographed by Paris Snider | Illustrated by Soon Lee

Written by Mirandah Davis-Powell | Photographed by Paris Snider | Illustrated by Soon Lee

Nancy Hohenberry, 85, currently resides in Seal Rock, Oregon. She rents out a single room from her good friend, Claire Twitty, where she stays with her cat, Meow-Meow. Just 12 weeks ago, Hohenberry lived in a senior residential community at the Eugene Hotel, and she never thought she’d return to this quiet, coastal life.

Hohenberry initially moved in with Twitty when the COVID-19 pandemic hit. After about a year, however, Hohenberry began to experience substantial health issues. Living all the way out in Seal Rock made it difficult to access medical services, so she made the move to the Eugene Hotel in March 2022. In her time there, she grew to love the community and comradery that so many appreciate about living there.

Now she’s back in Seal Rock after rent increases priced her out of the Eugene Hotel. The decision to move wasn’t easy. She would deeply miss living there, and would once again have to drive five hours a day several times a month in order to receive medical services. Yet, with the jump in price that’s occurred at the hotel, it’s no longer a viable option.

The Eugene Hotel is a senior living community located in the heart of the city that has seen price increases after falling under new ownership in 2022. After an acquisition by DiNapoli Capital Partners, a Californian real estate investment firm, the cost of living at the Eugene Hotel jumped from a 3% annual increase to 14.6%, the maximum under the legal limit in Oregon. DiNapoli Capital Partners did not respond to Ethos Magazine’s calls requesting a comment on this change.

This rent hike has forced tenants of the hotel to consider the sudden reality of relocating. Several seniors living at the Eugene

Hotel depend on a fixed income provided by Social Security and have cut back on other expenses or found somewhere else to live.

There are many tenants who have made do, but anticipate that if the maximum allowable rent increase percentage makes another jump next year, they too will have to leave.

“Even if we can stay now, because we don’t know what the future is, we can’t comfortably stay here,” says Ulla McKinney, a current resident of the Eugene Hotel.

Another current resident, Judy Bruns, notes that her rent has increased by $220 since the rent hike. She’s had to cut back on spending in other areas of her life in order to pay the new monthly cost of $1,800 for her studio apartment. “I can’t continue to take big hits like that, and we don’t know what that’s going to be from year to year,” Bruns says.

Carol Link, who has been a resident of the hotel for over three years, feels ready to search for alternative options if the hotel sees another price increase in the next year. “It’s gotten to the point where it does not really feel financially sensible for me to stay here,” she says. “I’ve been biting bullets for so long that it’s habit. If they come up with another 15 percent next year, it’s sayonara.”

Link’s future might involve taking up residence with family members, something that several seniors are considering. Others who have had to move out due to the price have sought out other affordable housing in Eugene, though there is not much. In Hohenberry’s case, it meant moving all the way out to the coast in order to find an affordable, feasible option.

Hohenberry had been living at the Eugene Hotel for two weeks short of a year when she made the decision to move out.

Nancy Hohenberry, 85, holds her cat, Meow Meow, at a friend’s home in Seal Rock where she returned to live after leaving the Eugene Hotel in early 2023.

She first moved into her apartment at the hotel after receiving surgery, when she was feeling weaker than she does now. “I was not doing well when I moved in there,” Hohenberry says. “And I thought, ‘well you know, this is the end of the road.’”

“But I came back to life,” she says.

Seeing the residents of the Eugene Hotel being such active participants in their community, overcoming their individual hardships and flourishing in older age helped Hohenberry believe that she could, too. “I started thinking, ‘how can I get better? How can I start going on trips with these people? How can I be able to go to movies every night?’” she says.

The Eugene Hotel provides several activities to bolster community engagement for seniors, including trips around the city, performances at the hotel, movie nights, bingo nights and more. For many, the aspect of community at the hotel helps them feel liberated and supported. Hohenberry has been sad to leave behind the community at the hotel. While she, her housemate and their friends are able to play the occasional card game, there was an energy at the Eugene Hotel that can’t be replicated.

“For many of us who might have been isolated in our homes had we stayed there, here we had a community,” says Beth Weldy, a current resident of the Eugene Hotel. She believes that being surrounded by like-minded people becomes very important as one gets older. “Our friends are here, our activities are here, so staying in this community was important,” she says.

Mearl Grabill, another current resident at the hotel, concurs that the community and activities that exist at the hotel are vital for helping everyone feel a sense of belonging. “The activities, it just makes it feel a lot more hopeful,” he says.

“It’s more important as you get older that you have a future that you can kind of predict,” Grabill says. With the recent changes in the cost of living for what was once affordable housing, there has been a new sense of insecurity among the tenants of the Eugene Hotel. “The idea of potential homelessness isn’t an abstract idea,” Grabill says.

Grabill has been working with the Eugene Tenant Alliance to help keep seniors involved in the political process. SB611, a rent control bill being discussed in the Oregon state legislature, would put a cap on annual rent increases for residential tenancies. It has passed out of the Senate committee and is scheduled for a third reading and Senate vote on Wednesday, May 31. If passed, it would then head to the House for consideration.

Grabill helped facilitate and organize around 80 of his peers at the Eugene Hotel to submit testimonials to the state legislature in favor of SB611. Their testimonies revolve around the central question: “Is this the Oregon way to treat seniors?”

The opportunities for political participation, community engagement and socialization that Hohenberry discovered during her time at the Eugene Hotel made her feel much more capable. As her health improved physically, she was also healing in other ways.

“I got to where I was waiting for 3:30 to get myself ready to go down at 4:30 to have dinner at 5:00,” Hohenberry says, recounting the excitement she felt to participate. “I was waiting for the time 6:00 to come around and go see the movie and see who was there.”

She recalls always feeling a sense of belonging and a level of care in the community, as well as from the staff that worked at the hotel. “I never felt like I didn’t matter. It was always, ‘good morning, Nancy, how are you today?’” Hohenberry says.

Hohenberry remembers several instances where she felt supported for small acts of kindness that accumulated over time. Between staff offering to bring her heavier packages up to her room, to having the option to have dinner brought to her room, no questions asked, she felt like she wasn’t just another person taking up space; she was valuable and important to the community.

“I miss the people who sat at my table,” Hohenberry says. She still makes an effort to communicate and visit her friends from the hotel when she comes into town, but she says “it isn’t the same.”

Hohenberry is very fond of the time she spent at the hotel, and is a strong believer in the effectiveness of the model of independent senior living.

“I think for seniors to live in a collective like that is very very good mentally, spiritually, physically,” she says. “It brings the best out in people.”

Her positive experiences with the hotel helped instill within her a new sense of capability and empowerment.

“I moved in there thinking this was the end of the game, and I moved out playing the game,” Hohenberry says.

Her newfound hope and optimism for her future are accompanied by lots of plans for how she might focus on her passions. Currently, she’s looking forward to a potential trip to Europe next year with her sister, and her close friend and current housemate, Claire.

She also is interested in purchasing a metal detector, now that she’s living on the beach. “I want to walk up and down the beach and see if I find anything worthwhile,” she says.

Hohenberry is also discussing making a trip to the Painted Hills in Oregon and exploring further her love of geology, examining the fossil beds at the national park.

“I want to go do something like that, and now I think I can,” she says.

Hohenberry still finds herself missing the nearly 100-year-old historic building.

“I do miss it, it was a very memorable part of my life,” Hohenberry says. “When I get to be 95, maybe I’ll go back, even with all its faults.”

In third grade, Catie Cooper was sat down by her parents. They explained to her that her mother, Carrie Cooper, was sick and would not be getting better. At the time, Catie did not understand what her parents were saying and how it would affect her mother.

Carrie was diagnosed with Huntington’s disease at the age of 33.

“She was always the life of the party and always the happiest person in the room,” Catie says. “I think that is where I got my spark from.”

Despite the hardships, Carrie continued to make jokes throughout her fight with Huntington’s disease. She died on March 23, 2022.

Today, Catie is a sophomore at the University of Oregon studying public relations. Catie has been working for the last three months with the Huntington’s Disease Society of America, planning HIIT Huntington’s Disease Back, an event to raise money for research of the disease.

Huntington’s disease is an inherited genetic disorder affecting one in every 10,000 to 20,000 people. Huntington’s disease causes neurons in parts of the brain to break down and die.

“The hard part with Huntington’s is that it does eat away at your brain,” Catie says.“It doesn’t really take your spark away, but it did affect her movements and her ability to make cognitive decisions.”

According to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, when a person has Huntington’s disease, there is a 50% chance it will be passed down to their children. As of 2023, Huntington’s does not have any cure or treatment to stop the disease from getting worse. However, support and treatment can help people with Huntington’s deal with some of the issues the disease can cause.

”With Carrie, she got to a point where she really was just homebound,” says Mark Cooper, Catie’s father. Huntington’s is a life-changing disease, and “a patient will get to some point where they can’t drive, it’s hard for them to go out, they can’t go to dinner, they can’t go to a movie anymore,” Mark says. “So really, their world shrinks and as that shrinks, there really is nobody on the outside that knows what is going on.”

Carrie’s death “got the ball rolling for me to bring awareness,” Catie says. Outside of fundraising, Cooper has been a part of multiple events to spread awareness, but HIIT Huntington’s Disease Back is her first time taking the lead.

“I’m dipping my toe into the water and I’m hoping that this can be an annual event,” Catie says.

After months of work, Catie’s event took place on May 13, on the EMU green at the UO. HIIT Huntington’s Disease Back is a high-intensity interval training, or HIIT, class paired with a silent auction and raffle to raise money. A few of the raffle items included a certificate to the Oakway Golf course, a PR package from Jordyn Mannino, a basket of snacks from Lone Oak Assisted Living and a 10 class pass from Glow Yoga. Some of the groups supporting the event include The Huntington’s Disease Society of America, Expert Surplus, Bubble Social Balloons and the UO’s chapter of the Sorority Alpha Phi.

Catie Cooper, a sophomore at the University of Oregon, is raising money for Huntington’s Disease through fundraising on the EMU green.

Catie is not the only member of the Cooper family doing this kind of work. Catie’s older brother, Jack Cooper, planned an event with the Huntington’s Disease Society to raise awareness in January 2022. This event took place at Jack Cooper’s college, King’s College in Pittston, Pennsylvania. The King’s College men’s ice hockey team hosted a Huntington’s Disease Awareness night including contests and a raffle, and all proceeds from the event went to the Huntington’s Disease Society. After Jack’s event with the Huntington’s Disease Society, Catie was inspired to put on her own event at the UO.

“I saw the turnout on that,” Catie says, “and how big an event like this could be.”

Planning the HIIT Huntington’s Disease Back event took about three months. Catie says reaching out to possible sponsors and people in the community felt like a full-time job.

“Everyday I am on calls and emailing people,” Catie said before the event. She says balancing her role in planning the event and school work as a full-time public relations student at the UO was “very stressful, but it’s very exciting.”

All of the advertisements for the event were designed by Catie herself. She is also responsible for making the posters and social media for HIIT Huntington’s Disease Back. Additionally, she produced and wrote a script for a video talking about her event and the cause she is supporting.

“It is a really emotional and passionate fight with Huntington’s,” Catie says, and that is why she is “ doing everything that I am doing, and same with my brother and his event.”

HIIT Huntington’s Disease Back started with a speech from Catie herself about the different activities and ways to raise money at her event. Catie thanked everyone for

being there and introduced the HIIT instructors for the main event, Hailey Madsen and Ashley Van Goorden. Madsen and Van Gooren then led people through a 30 minute HIIT class while others participated in the silent auction and 50/50 raffle.

Mark was in attendance to show support for the event and says he is very proud of his children. He believes that with this kind of passion, change is possible for this disease.

“There is a cure in my kids’ lifetime,” Mark says, “But there wasn’t in my wife’s.”

Catie hopes to use the skills she has gained planning HIIT Huntington’s Disease Back to continue to plan more events for nonprofits.

“I am going to be really sad that it is over,” Catie says, “and I won’t have something to put my passion into.”

Because of her work with the Huntington’s Disease Society planning HIIT Huntington’s Back, Catie has a new opportunity to spread awareness this fall.

“I am on the board for a Portland Hope Walk in September,” Catie says, “so I’m now working with HDSA [Huntington’s Disease Society of America] to get that going.” The Team Hope Walk is the largest fundraising event put on by the Huntington’s Disease Society. The walk takes place nationally in over 100 cities as of 2022. According to the Huntington’s Disease Society, the event has raised over $20 million since it started in 2007.

Catie plans to continue to use her voice to help other children who have lost a parent to Huntington’s disease feel seen and spread awareness for the disease. While she doesn’t want to be a “spokesperson” for Huntington’s, she wants to use her voice and “whatever little platform” she has for good.

“I am kind of just trying to be a voice for other kids that are in my position,” she says.

The Oregon Cougars are a Women’s Tackle Football team in Lane County, Oregon. They compete in the Women’s Football Alliance (WFA), the largest women’s tackle football league in the country. The Cougars strive to empower women to learn, play and coach tackle football.

There are three WFA teams in Oregon. In addition to the Cougars in Lane County, there are teams in Portland and Salem. The league was established in 2009. Some teams formed with the creation of the league and some teams already existed, making the WFA their new home. Women’s football player and coach Lisa King and former NFL player Jeff King own the league, which has doubled in size since its inaugural season and only continues to grow. In 2012, the WFA’s championship game was the first women’s football championship to be played in an NFL stadium. In 2022, the championship game for their top division was nationally televised on ESPN2 for the first time.

According to historian John Pettegrew, “football’s requirement for bulk and mass” played a key part in preventing women from playing the sport. Many young girls do not have the chance to play tackle football because this traditionally male-dominated sport is not presented as one that girls can play. “This is our opportunity to get together, play with women against other women, and even more so, it’s fun,” Tressa Miller, who coaches and plays for the Cougars, says. Miller played football for the first time in grade school. She was the only fifth-grade girl on a team with sixth-grade boys, and it was flag football, not tackle. “It was kind of fun, but not really,” Miller says. She enjoyed the sport but being “terribly undersized” took away from that and made it hard to compete with the older boys.

Miller’s experience with youth football was cut short due to lack of support for girls that wanted to play. “I wanted to play in high school, but it wasn’t really cool for girls to be playing back then and it just didn’t work out,” she says. She came across a women’s football team while living in Los Angeles and played there for a couple years before moving to Oregon. While planning her move, she made sure that there was a team in the state. “I didn’t want to live in an area where I couldn’t play football,” Miller says, “because it was so much fun.”

Win or lose, the players are focused on having fun and taking advantage of an opportunity they haven’t always had. Unlike male professional football players in leagues like the NFL or the United States Football League, the women that play for the Cougars are unpaid. For these women, the team provides a space to play a sport they love with people that have become family. The smiles of a coach and a player, pictured above, reflect the positive and supportive environment of practices and games that the Cougars maintain.

The WFA is all about breaking barriers. According to the Smithsonian Magazine, women’s football leagues date back to the 1930s, but those stories have largely gone untold. The sport’s masculine reputation overshadows the contributions that women have made, and people often don’t expect women’s football to be as physical and competitive as it is. “It’s not the Lingerie Bowl,” Miller says. “This is real tackle football.” The women who play, and their supporters, are fighting to prove that women’s football is a legitimate sport and not just entertainment.

The Cougars are always looking for more players, regardless of an individual’s experience. Billy Jene Meza says she barely knew anything about football when she first started playing. She had never watched the sport, and her only experience was playing Powderpuff in high school, a no-contact football game played by girls, often as a fundraiser. “I could catch a ball. I didn’t know how to throw one,” Meza, who now plays quarterback occasionally, says. With the support of teammates and coaches, anyone can learn how to play.

There is still work to be done to make tackle football a more inclusive sport, but the Cougars are proof that it is possible. From their loyal fans and local business sponsors to Cottage Grove High School sharing their field, the Cougars have strong community support. Come out to a game and see for yourself how the Cougars are shaping the game of football.

In late summer of 2018, Meadow packed two suitcases and boarded a red-eye bus to Eugene, leaving an abusive childhood behind. They lived in the University of Oregon dorms and attended classes for a term, before receiving news that their FAFSA was never properly filed because their mother didn’t sign off on it. They could no longer continue school due to financial constraints.

“I was only there for a term. It was like $15,000,” Meadow says. “I’m a 17-year-old who’s homeless, like, how do you want me to pay for this?”

Meadow, who is using an alias to keep their story private due to concerns about their safety, says they spent their whole life fending for themselves, and taking care of their siblings in the process. They grew up near MLK Jr. Blvd in East Portland, a traditionally low-income area.

“I didn’t really get to have child experiences. I just worked, went to school, worked and went to school. I didn’t have any friends, and I didn’t have a phone to talk to friends on. I didn’t have any money – and any money I was making from work was going back to my siblings to pay for their food,” Meadow says. “My parents both grew up very poor, and we were very poor for a really long time. They were also really manipula-

tive...and any power they could take, they would take it.”

Meadow attended one of the only high schools in Oregon that has a majority Black student population. This school is historically underfunded, and the accompanying neighborhood is in the trenches of gentrification. Among the families that moved into the gentrified neighborhood was the family of Marigold. Marigold, who is also using an alias for the same reasons, started dating Meadow in early high school. They came from a wealthy, white family, and had college completely paid for, while Meadow endured the consequences of poverty and systemic barriers beyond their control.

After finding out that they could no longer continue at the University of Oregon, Meadow had nowhere to go for almost a year. Essentially houseless, Meadow slept in Marigold’s dorm room and stayed with friends. Eventually, once they turned 18, they were able to apply for housing at the Campbell Club.

The Campbell Club is one of three co-ops within the Student Cooperative Association, or the SCA. The SCA co-ops provide an affordable, landlord-free communal living experience, and keep their revolving door open to those who need it most. The co-ops offer some of the lowest housing rates in the area, and the Campbell Club seemed like the best option for

Meadow. They moved in in 2019 – marking the beginning of their four-year stay at the co-op.

Founded in 1934 as an experiment by a group of men from Northwest Christian College, the SCA was an early pillar for progressive and radical ideas about identity, community and shared spaces. The organization was registered as a tax-exempt nonprofit organization in 1942. The SCA offers some of the least expensive housing in Eugene, as low as $322 a month. The groups residing within these houses have ebbed and flowed like the tides — ever-changing, yet following a cycle with a longer history than any one member could have experienced.

Two of the houses are neighbors – the Campbell Club and Lorax Manner. The other, called the Janet Smith, resides down Alder Street – slightly tucked away. The other two houses mirror each other in their size, and contrast the surrounding sorority and fraternity houses in stature.

The Campbell Club’s massive, four-story build towers above the sidewalk, and passersby often slow their pace to gaze with curiosity. Found objects litter the front yard, strewn about like its own kind of garden. A newspaper box sits off-kilter, covered in paint, stickers and graffiti. Bicycle wheels hang from the covered porch. Few bystanders look close enough to see the rubber-bullet holes and pepper-ball stains, a sobering reminder of the Campbell Club’s role in the 2020 protests against police brutality following the police killing of George Floyd, when the house provided asylum to protesters behind its bunker-like wooden door.

But on March 14, 2023, the Campbell Club stood empty. A week prior, the SCA Board of Directors served nearly all of the residents a notice asking them to vacate the premises or reapply for membership. However, some residents claim that if they’d reapplied, the application wouldn’t have been accepted.

A few former residents moved to other housing options. Others wound up on the streets. A select few still live within the walls of the neighboring co-ops. However, nobody sees the inciting conflict as black and white – but rather as a breaking point after years of simmering tensions. It was the completion of yet another cycle that the SCA co-ops are familiar with: tensions boil over, and the revolving door screeches to a halt.

Meadow and Marigold are two of the residents who were served the notice.

“We’ve seen this sort of cycle of self-targeting,” says Marigold, regarding the history of the SCA. “Until there’s a tipping point, where everyone in the organization starts believing that one of the three houses is the problem. Then there can be relative periods of peace inside each of the two houses which are targeting the other one, because they have this solidarity.”

Those who reside in the Campbell Club, Lorax Manner or Janet Smith are not renters, but members. This means that the laws that apply to renters in Oregon do not directly apply to those who live in the co-ops. The official SCA bylaws state that upon moving into one of the houses, each resident needs to sign a membership contract.

The contract solidifies one’s pledge to contribute to the space and engage in the political structures. It acts as their lease, if a lease also dictated how a resident would interact with others in the space. The official bylaws state that the SCA membership contract essentially buys an equal share of ownership into the SCA, putting every resident on a level playing field when it comes to not only the ownership of the house, but the organization as a whole.

“The co-op depends upon responsible involvement from each member,” an old SCA handbook reads. “As the feelings of ownership become internalized, the co-op changes from simply a place to live into a way of life.”

Whether that way of life supports a person – or breaks them down – depends entirely on the dynamics between the individuals in each house, according to Marigold. A large group of people co-habitating in one space requires structure, structure that requires a governing body. But as outlined in the SCA bylaws, the governing body is the membership itself.

There are three levels of governance within the SCA: General Membership, House Government and the SCA Board of Directors. Each governing body tackles issues at a different level, and everyone who participates lives in one of the three houses.

The General Membership is made up of everybody in the SCA at a given time. General Membership Meetings are held twice a term, and provide a forum for everyone in the SCA to air their grievances, elect corporate-level positions and vote on organization-level policy decisions. The House Government is unique to each co-op, and dictates smaller scale house roles and house-level policy decisions. The SCA Board of Directors is comprised of members from all three houses, and is responsible for the “affairs, funds, and property” of the organization, according to the organization’s bylaws.

Although each member of the SCA comes from a unique background, many of their stories mirror one another, revealing a cycle of collective struggle among young, largely queer and low-income people. Many of these people join the SCA because it’s the only thing they can afford. Cost of living is spiking, and rent in the West University neighborhood is rising due to new urban development. According to Zumper, the average rent for a one-bedroom apartment in the area is $1,150, which is a 31% increase compared to the previous year.

Oftentimes, those who enter the SCA come off the street. Consequently, many who leave the SCA wind up back on the street.

Due to the SCA’s structure, “evictions” such as the one that occurred in March are quite common, according to Marigold. However, these events are not technically evictions since the SCA hosts members, not tenants. These events are classified as a “termination of a membership contract,” or in this case, a “notice to vacate,” according to the official notice that residents received. When someone is asked to leave one of the houses, they are typically asked to do so within 24 or 72 hours – or in this case, a week.

Meadow and Marigold left the Campbell Club for the last time on the night of March 13, and lived in their van for the following two months. They have since found housing, as of early May.

When Meadow moved into the Campbell Club in 2019, they moved into a version that had, in their words, descended into chaos.

“I was the youngest person there. Everyone who was living there had also been there for a few years at that point already. The entire SCA was like a pretty tight-knit community,” Meadow says.

However, Meadow describes the community in the Campbell Club at the time as highly toxic. As an 18-year-old, feminine-presenting – but not identifying – Black individual, Meadow felt isolated and targeted amongst the largely white, male and early-30s membership.

“I’m a pretty direct and forward person, and confrontational for sure,” Meadow says. “I get called aggressive, mean and scary – like all sorts of things. That sounds really racially charged.”

After over a year of enduring what Meadow described as an abusive living situation, Marigold also decided to move into the co-op. Marigold’s move marked a turning point for the population of the co-op, and older residents began to leave as younger ones moved in.

Among these younger residents was Summer. She is using an alias to protect her identity because she currently lives in the Lorax Manner. Summer grew up in a low-income home in Eugene, and describes her home life as abusive. She moved into the Campbell Club because it was the only thing she could afford. As a transgender woman, she was also excited about being surrounded by people who either shared or respected her identity. However, her time at the Campbell Club did not prove to be productive, or harbor a feeling of safety.

“I was scared to leave my room for many months,” Summer says, “and was so traumatized that I couldn’t talk to anyone.”

For a time before the COVID-19 pandemic, the Campbell Club operated in relative harmony. The house had a sizable membership, and nearly everyone participated in the SCA systems – such as jobs and house government roles.

Then came the pandemic. The Campbell Club went on lockdown, and its revolving door halted when the SCA periodically stopped accepting new members due to health concerns. The lockdown marks the relative beginning of the tensions that ultimately led the SCA Board of Directors to issue the notice to vacate.

“There was a fight about people feeling others weren’t being safe enough around COVID,” Marigold says. “And at that point, we really cut off accepting new members for a bit. We started to become more comfortable. We had become so insulated.”

Campbell Club members had to spend all of their time together inside the house, which exacerbated existing tensions and led to new ones, according to Meadow, Marigold and Summer. One of these new tensions was due to Meadow’s

health, and how they claim some of their housemates handled the lockdown.

“I’m immunocompromised and disabled,” Meadow says. “We need to get some measures into place. We need to do something – like this is really irresponsible. We’re a large community.”

The Campbell Club was not only insulated, but isolated from the rest of the SCA – specifically the Lorax Manner. The two houses are neighbors, but since the COVID-19 pandemic, have not had the same close relationship as they once did.

The Lorax Manner continued operating in relative peace, while the Campbell Club descended into factionalism. Summer felt isolated within the house, and began to never leave her room due roommate tensions. This factionalism, as Marigold calls it, was present in the Campbell Club during the time before the younger generation moved in, as well.

“There was a tension between these two communities,” Marigold says. “This sort of factionalism started out – which we thought was new – because it was new to us. But in reality, it had been going on for a long time, and we were just a new faction.”

One of these factions included Meadow and Marigold, along with another member of the Campbell Club. After years of living within the SCA, and seeing how these systems functioned, they felt as if the systems were built to fail.

These systems, however, depend on the cooperation of the individuals inside each co-op, according to Leah, a Lorax Manner resident who is using an alias for the same reasons as Summer.

Beginning in early 2021, Meadow, Marigold and a few other Campbell Club members made the decision to stop operating under the structure and bylaws of the organization because they say the system did not meet their needs. They no longer held house meetings, didn’t assign house roles and Campbell Club members no longer served on the SCA Board of Directors. Meadow and Marigold say, however, that they were still wholly committed to the upkeep of the house.

“As a space, as a construct for Eugene, we wanted a place where people who could not afford to rent to either work – or contribute in some other way to our community – in order to live,” Marigold says. “After abolishing the job system that we all sort of agreed on as a plan for this space, we all had our own ideas. And we all just did them. We had to invest in the space that was ours – this is all we had. And by the end, most of those people weren’t paying, too.”

It was also at this time that many Campbell Club members did not sign a new membership contract for the 2022-2023 school year. According to Marigold, this was a way to protest the policies of the SCA. They say the SCA Board of Directors did not always enforce having current and updated membership contracts, and membership contracts often fell through the cracks.

Campbell Club members’ lack of current and updated membership contracts provided the basis for the SCA Board of Directors to send them the notice to vacate in March

2023. According to Feb. 13 board meeting minutes, as well as the notice itself, certain residents were in “violation of the bylaws,” and their memberships were deemed “not valid.”

Additionally, most members of the Campbell Club had stopped paying dues, which operate as rent. According to Marigold, this was in protest, but was also largely due to the dire economic situations that led so many residents to the coop in the first place.

The official bylaws of the organization state that “accumulation of a debt to the corporation of an amount equal to or exceeding one quarter of the room and board charges for that fiscal year shall result in the termination of residence and the loss of membership within fifteen days of the incurring of such a debt.” For the residents of the Campbell Club who were served the notice to vacate, they were in violation of this bylaw for far longer than 15 days. However, Marigold claims that this bylaw was “obscure,” and hadn’t been evoked in years.

“It’s being framed as like everyone was evicted specifically, which from a functional standpoint, that’s kind of true,” Summer says. “From a legal, technical standpoint, nobody was evicted.”

Since SCA members are not classified as members, Summer says, technically, nobody faced an eviction. The notice to vacate was not only served to Campbell Club members. The SCA Board of Directors sent this notice to everybody in the three houses who didn’t have a valid membership contract to keep things fair. However, Meadow, Marigold and Summer all claim the Campbell Club was the only house mentioned in board deliberations as the catalyst for the notice. The board meeting minutes corroborate this claim.

The notice to vacate outlined a few possible courses of action for those being asked to leave. They could reapply for membership within 24 hours or apply for a guest stay within 24 hours – which would grant them 30 extra days to find housing. Both applications would be reviewed by the SCA Board of Directors, who would then decide whether or not they would grant those individuals a new contract. A few residents, including Summer, reapplied for membership. That membership was granted, and they moved into the Lorax Manner soon after the notice was sent.

Meadow, Marigold and other Campbell Club residents applied for the 30-day guest stay. Their applications were accepted, however, under a series of conditions. These conditions, outlined in a letter from the SCA Board of Directors, included a ban on friends and outsiders from entering the house, request for the login information for the Campbell Club Instagram account, as well as the wifi password for the house. The conditions also required that residents not “threaten, harass, intimidate, or steal from any current SCA members, guests, or employees,” and also stated any damage to the property would terminate their guest stay immediately.

Marigold, Meadow and another resident sent a letter back, stating that they did not agree to these conditions, and would move out on the original timeline. They also decided to get loud on social media, making a series of posts that incessantly used the words “mass eviction” and “illegal eviction.”

A few remaining residents then put together a show, dubbed the “Mass Eviction Benefit Show,” to raise funds for those who needed housing, as well as spread awareness about their side of the story. The show took place on March 11, and served as a “last hurrah” for the former residents of the Campbell Club. They took this opportunity to slather their former home in bright pink paint, scribing the words “dance if you hate eviction” on the floorboards.

This was not an illegal eviction – on paper. Meadow, however, claims that theirs was, to some degree, illegal. In the summer of 2021, at a time where they were actively paying dues and had an updated membership contract, Meadow applied to be a work-trader. Work-traders are SCA members just as much as anyone else, the only difference is that they exchange work for their residency instead of paying dues.

Their work-trade application was accepted, but it was during a time that the SCA Board of Directors was reformulating the work-trade membership contract. Meadow claims they were told that they would be sent a new membership contract when it was completed. They also claim that they were never sent that contract. So at the time that they received the notice to vacate, because of the lack of having a membership contract, they never had one – not because of their protest to the system – but rather because of an oversight from the board themselves, they say. The SCA Board of Directors did not respond to Ethos Magazine’s request for comment.

“Because I didn’t need a regular membership contract, I needed to sign a work-trade contract,” Meadow says. “But they didn’t give it to me.”

As of right now, messages are mixed about whether or not there are currently individuals living in the Campbell Club. Meadow and Marigold say that there are not, but Lorax Man-

ner resident Leah says that there are. Leah is also using an alias, as to not reveal her residency to the general public. Regardless, new members are incoming, and about to land in the blank slate that is now the Campbell Club.

“We just kind of want to be able to get over this and raise money to be able to fix up the Campbell Club,” Leah says, “for the people who are living there.”

The SCA has been a positive force to many who’ve gone through its revolving door. Although the crisis at the Campbell Club is not an isolated incident, many members have encountered the opposite experience, says a Janet Smith resident who chose to remain anonymous.

“I can only speak from my experience, having lived in this house has been positive all around. And I felt like in my own measures of success, it’s a healthy and thriving place for me,” they say.

“It’s built around reciprocity…and I haven’t encountered a structural problem, personally. I would love to see a situation where no one ever has to leave. Even within the houses, there can be this image of the SCA as this institution. But frankly, we know everyone. Everyone knows everyone. The SCA is not this ‘big brother’ thing. We are all the SCA.”

The revolving doors are turning once again, and waiting to welcome the new batch of residents to call the Campbell Club home – next up to contribute to the longstanding legacy that’s held in the house’s very foundation. Marigold doesn’t discourage incoming residents from applying, they say.

“[The conflict] was created by the people in it, to some extent. But it involves the history of this system as it’s moved forward. There’s echoes of every period previously,” Marigold says. “But now it’s a blank canvas again.”

“In many ways we resemble a big family, but we’re non patriarchal. In many ways we’re a club, but our interests are varied.

In many ways we’re a business, but we do not play landlord.

In many ways we are a social and political movement, but we are not a party seeking to enrich our pockets nor extend our ideals to others. We are a group of people living cooperatively for our mutual benefit, making room for our similarities and our differences, sharing ourselves and practicing a very real democracy.”

These words, akin to a mission statement, are printed on the inside cover of a small booklet, stapled down the spine. This is an old handbook for members of the Student Cooperative Association (SCA), which owns three co-ops in the West University neighborhood of Eugene.

wines, hard ciders, beers and every preference and there’s a myriad of choices away from campus. our selection, available at the Flagship Campus

Please enjoy responsibly.

FREEdripcoffee everyFridayattheFlagshipCampusDuckStore only when you wear your Duck gear!*

* Limit one free coffee per customer per Friday.

On Feb. 11, 2023, Will Garrahan was fired from the University of Oregon dining services for taking a bowl of food.

Garrahan, a former dining hall worker, had taken the bowl four days earlier. In the middle of working an 8 to 10 pm shift at the Global Scholars Hall bowl station, Garrahan made himself a bowl at 8:30, as all the hot food is thrown away at 9. Garrahan brought the bowl to an area behind the food station where employees often store their belongings when a coordinator saw him and reported him. Garrahan, along with all UO employees, had signed a contract stating he couldn’t steal any university property while working. Food is not an exception.

“It’s just funny I get to work the line all day, but I don’t get to eat the food I’m working with,” Garrahan says.

Garrahan’s story is merely a piece of the puzzle that currently composes the relationship between student workers and the university. Beginning in fall 2021, dining hall workers, resident assistants (RAs), dorm employees and other student workers came together to unionize. Their desires include better and more frequent pay, improved harassment and rule-breaking policies and an increase of resources. Currently, they are in the midst of unionizing as a group.

According to the U.S. Department of Labor, a labor union is “a group of two or more employees who join together to advance common interests such as wages, benefits, schedules and other employment terms and conditions.” For UO student workers, being part of a union has meant doing everything in their power to create a better and healthier working environment for themselves, and future classes to come.

The UO currently has over 4,000 student workers dispersed throughout the dorms, dining halls, campus buildings and more. An estimated 3,800 of them are a part of the union.

The desire to unionize among students is not uncommon, and Grinnell College, a liberal arts school in Iowa, paved the way.

In April 2022, Grinnell College became the first independent undergraduate labor union in the country. After first unionizing in 2016, they ran a campaign two years later to expand the group. The vote passed and the local Region 18 National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) in Minneapolis, Minnesota, sided with the students, but the school appealed to larger authorities in the former president Donald Trump-appointed NLRB.

“We backed down,” says Kelly Banfield, a member at large of the Union of Grinnell Student Dining Workers (UGSDW).

Despite the challenge, the union persisted through the next five years and proved that a student-driven campaign can make significant changes within a university.

“The presence of a union on campus makes you more aware of your rights as a student worker,” Banfield says. “I think it’s helped me better advocate for myself and others.”

Kenyon College in Ohio, Dartmouth College in New Hampshire and Barnard College in New York are a few of the universities that have followed suit in labor organizing amongst their undergraduate dining hall workers. Additionally, graduate students at private universities earned the right to unionize in 2016 after a ruling within Columbia University.

The key difference between all these successful schools and one like UO is student body size. UO has about 15 times more students than some of the aforementioned private schools. Therefore, it’s much harder to unionize.

Garrahan joined the campaign a little over a year ago after hearing about it through the Young Democratic Socialists of America (YDSA) chapter through the UO. At that time, the campaign existed mainly to improve working conditions for student workers. The Union of Student Workers was formed, and over time became known as “the union.” At that early time, just under a dozen people belonged to the group — some, like Garrahan at the time, weren’t even student workers.

“I wanted to help the world around me, and I’m a big fan of unions,“ Garrahan says. “I joined because I wanted to make a difference, and I still feel that way, although it’s been a rough year plus at this point.”

When Garrahan joined, student workers in the campaign were advocating for better representation in the Associated Students of the University of Oregon (ASUO). Members believe that the interests and priorities of the ASUO didn’t align with true issues amongst students, requiring a need for better representation. The effort ultimately failed, but according to organizers like Garrahan, it didn’t slow the union fighting for other causes.

A frequent complaint among student workers has been the frequency of their paychecks.

UO’s student worker policy sees that they are paid just once a month, on the last working day of each month. They’re paid for the work they did on the 16th of the previous month to the 15th of the current month, so if a student only worked the back half of the month, they’d have to wait over a month to get paid. This directly violates Oregon law 652.120, which claims that “payday may not extend beyond a period of 35 days from the time that the employees entered upon their work.”

Students are also allowed to work 25 hours maximum a week, which can’t fully financially support many.

The limit in hours, combined with the infrequent payments, creates a difficult budgeting situation for many students.

University of Oregon student workers are making history as they work to create a better future for themselves.

“We’re young adults,” Garrahan says. “We don’t have savings. Our jobs don’t pay us enough to be able to be paid monthly, and I think it’d make more sense to be paid bi-weekly like other people our age.”

Brennan Furber, a worker at the UO Student Recreation Center, agrees. He’s one of many student workers to have a second job, one that pays him bi-weekly.

“Budgeting is extremely difficult,” Furber says. “Especially because I feel like I’m one of the only college students that has to pay for my own stuff. I pay my rent, phone bill, car insurance, so on a monthly stipend, it’s really tough.”

Another complaint from Garrahan, although he never experienced it himself, was dining hall management misgendering staff. He, and Carolyn Roderique, an RA of two years and an organizer for the union, also brought up the inconsistency of management, specifically with disciplinary actions.

Garrahan noted a large turnover rate among workers in the dining halls even though he only worked there for over eight months. No call, no shows were common among workers, yet some would never get followed up with or disciplined.

A month after Garrahan’s own firing, a protest was held outside the EMU fishbowl among furious Starbucks employees.

An employee who’d previously been a student at the UO and had seven years of experience working at Starbucks was fired for using an inappropriate word in front of customers, but it was a month and a half after the fact. The underlying suspicion behind the firing was student unionization, as this employee was part of the campaign.

Once coworkers were aware, they stopped their demanding jobs temporarily and went outside on strike, which received local press.

“I saw something about how it’s one of the largest campus unionization efforts in the U.S.” Furber says. “It definitely deserves press. What it could mean for other schools, campuses and unions could be really impactful.”

Prior to the Starbucks protest, around the same time as Garrahan’s firing, an issue arose between the UO and RAs. While promised a raise from the university, many RAs joined the unionizing efforts, and subsequently, the UO never paid the raise. The RAs had actually won the case for the raise before any of them started filling out union cards, but many decided to join the union once their demands weren’t met. The connection between unionization and lack of pay was never explicitly mentioned and documented, although most RAs and organizers suspect they are related.

“I don’t really think there are words for something like that,” Roderique says. “We just feel disposable to them. That’s a word a lot of us RAs have come up with. We’re disposable to them, and they treat us like we’re disposable.”

According to Roderique, she was first told that unionizing was the sole reason for the lack of a raise, but later, she was told it was just part of the reason. When the university has been asked to comment on student unionization, they’ve reportedly stayed neutral on the issue, telling local media that they don’t take a position on it. However, even the simplest protest efforts, like unionization pins, have been banned among student workers.

“They say they’re neutral on student unionization, yet they take away this pay raise because we’re unionizing,” Roderique says. “It doesn’t make much sense.”

Besides housing and food costs, RAs get just a $100 stipend each month. According to Roderique, they also haven’t received a raise since the 2019-20 school year. A survey amongst RAs was conducted last fall by the Student Leadership Council, and the results showed that over 90% of RAs felt finally insecure and 48% had a second job.

“We’re not fairly compensated at all for how much we keep this place together,” Roderique says. “There’s also just not enough mental health resources and follow ups for RAs because of things like sexual assault, stalking, domestic violence, suicidal ideation. Those are all things we can and do deal with on the job, and something we’re not well supported with.”

Dealing with medical personnel, intoxicated underage students and loud or destructive students are just a slice of the endeavors an RA deals with on a daily basis. According to Roderique, some have been physically assaulted by students. RAs that are heavily involved and outspoken in the union, like Roderique, risk their working and living situation daily by fighting for what they believe is right.

Roderique has openly advocated for RAs for over a year, but many of the complaints haven’t gone anywhere. She says that there’s been times where RAs complaints are met by the housing department with comments about how being an RA at other universities is far worse, or that back in their day, being an RA was much worse, in general.

When Roderique joined the union this past November, she finally felt listened to.

Currently, the union and the UO are trying to work together on a bargaining unit, or a collective number, that will clarify what union cards will count and which won’t, but it hasn’t been easy. On May 1, the UO sent out an update stating that the bargaining unit would only include students who

“I saw something about how it’s one of the largest campus unionization efforts in the U.S. It definitely deserves press. What it could mean for other schools, campuses and unions could be really impactful.”

- Brennan Furber

worked an average of four hours per week over three consecutive months, which would result in about 700 of 4,000 student workers total.

Once it’s clarified which cards will and won’t count, other factors such as timeliness and legalities will play a large role in the unionization process. If a majority of student workers in the bargaining unit don’t have a signed card, it would trigger an election within workers in the bargaining unit to determine whether or not they’re able to unionize, yet this would take around 45 additional days for the university to prepare for and advertise, according to Garrahan.

He also added that the unit would like to avoid any longer delays as factors like summer break come into play, but at the end of the day, the university holds lots of power.

“One of the best tools for the university is that they have the advantage when it comes to timing,” Garrahan says. “Students leave campus, classes change, schedules change. Stalling just a little bit can be the difference between us winning a contract in 2023 or 2024.”

As for Garrahan himself, he’s currently looking for a new job outside of the dining halls, leaving behind some of his closest friends and coworkers from his time in food service.

For workers at Grinnell like Banfield, hardships from the university have become far too common.

“The college makes it really hard to organize,” Banfield says. “They’ve taken away our abilities to reserve rooms. We can’t

reserve a table in front of the dining hall anymore, even though that’s allowed for all other groups. We kind of just float between spaces; it’s not an effective strategy.”

While the hearts of organizers in the union like Garrahan and Roderique are all about fighting for what they believe is right, it’s evident that the university could make it difficult for their efforts to be rewarded. For now, one of the best things they can continue to do is make both their individual and group efforts heard, for every student on campus.

“The university needs us to function, and without us, they really don’t have anything,” Garrahan says. “Who’s going to work the dining halls? Students should be aware because

A Starbucks union sign is seen on a telephone pole on Franklin Boulevard, in Eugene, OR.

Mustafa Kasubhai almost didn’t take the bar. Now, he is creating new standards for the judicial system.

Written Karembelas by Emily Rogers | Photographed by Sammy | Illustrated by Kaia MikulkaSticking out like a sore thumb between a Whole Foods and a bank, a chrome federal courthouse sits stalwart. Inside, security guards with stern faces patrol the maze of offices and public rooms. And in a fifth floor office is a man who has no idea how he got there.

Seated in a leather chair, Mustafa Kasubhai sports a welcoming smile that mediates his commanding voice. He is the first Muslim American federal magistrate judge and an evangelist for gender identity rights in the courtroom.

Kasubhai graduated from the University of Oregon in 1996 with a law degree and a feeling of estrangement.

“Law school was an interesting experience for me,” Kasubhai says, “because I felt like an outsider in the law.”

There are 4.5 million Muslims in the United States, with a growing population that has increased by 1.9 million from 2010 to 2020. However, there is a distinct lack of Muslim American identifying workers in the legal system. In a 2017 study, scholars were unable to find any Muslim federal judges. The UO Office of Public Records was unable to provide data on the religious affiliations of UO School of Law students, specifically.

Kasubhai is a first generation American. He grew up in San Fernando Valley, which has a predominantly white population.

Kasubhai was shown a foreboding perspective of the government by his Indian immigrant parents.

“My parents grew up at a time in India where you had to be cautious around government officials, police, judges and lawyers,” Kasubhai says. “Back then, you’d have to bribe people or they would threaten some kind of extortion.”

Yet Kasubhai was driven to pursue social justice because he couldn’t stand to see bullies pick on vulnerable people. Once he entered law school, however, he found they weren’t discussing the matters of social justice and inequity that had spurred his passion for law. Instead, Kasubhai found law school tended to emphasize success as working in a big law firm or clerking for a judge.

Despite graduating from the UO law school in the summer of 1996, Kasubhai didn’t take the bar.

“Law school wasn’t a place that fed my passion for social justice; in some ways, I think it kind of muted it,” Kasubhai says.

He says he remembers many of his BIPOC peers leaving for Portland or other states they felt represented them better than Eugene. But Kasubhai never left Eugene in search of a Muslim community, saying he was used to the isolation.

Kasubhai took a job working as a reference librarian at the UO law school, feeling discouraged. However, while surrounded by law texts and common people researching law, Kasubhai’s passion was reignited.

“People were coming in to do their own law research,” Kasubhai says. “I realized that there was space for lawyers who wanted to represent everyday people.”

After passing the bar in 1997, Kasubhai pursued a job as a plaintiff attorney in Klamath Falls, Oregon.

Klamath Falls is a small rural area with a population of 22,062 people. According to the American Bar Association, “There are 1.3 million lawyers in the United States, but they are mostly concentrated in cities, while many small towns and rural counties have few lawyers.” These areas are known as “legal deserts.”

In this legal desert, Kasubhai was able to satisfy his interest in social justice by giving the opportunity of legal representation for people that were injured.

However, he quickly learned there wasn’t much to change in this field and faced microaggressions from other lawyers and from judges.

“They would compliment my lack of an accent,” Kasubhai says, “or refer to me as ‘one of the good ones.’”

Kasubhai decided to close his practice in sight of a job where he could have a better chance of creating social justice.

Yet, while trying to back out of the legal arena, an opportunity to become a board member at the Oregon Workers’ Compensation Board opened. Here, Kasubhai was able to provide social justice by enforcing laws that protected workers.

Recognized for his efforts, federal judges nominated Kasubhai to be the first Muslim American federal magistrate judge in 2018. Kasubhai was shocked to receive this title in Oregon, a state that was founded on laws aimed to exclude BIPOC individuals. He believes someone should’ve come before him, especially in states with more predominant Muslim representation, like New York or New Jersey. He wishes that, instead of people celebrating him as the first, they were celebrating the 50th or the 100th.

Mariam Hassan, a Muslim UO undergrad student working to become a lawyer, first met Kasubhai at an Oregon Muslim Bar Association (OMBA) event. Hassan remembers his presence commanding the attention of the room anytime he spoke.

“I was so impressed with everything he had,” Hassan says. “I wanted to be him.”

In the fall term of 2022, Hassan was given the opportunity to present a case in front of Kasubhai for one of her law classes.

“When I first met him, I was intimidated because he was powerful. But when I went up to him, he was completely different,” Hassan says. “He’s enthusiastic about helping everybody, especially younger Muslims, to reach the position he’s in.”

Kasubhai says being the only Muslim American in any given room often left him questioning who would advocate for him in those spaces. That feeling of being alone is something Kasubhai doesn’t want others to feel and why he works to help others.

It’s also what led him to tackle the issue of pronouns in his courtroom.

“When I first met him, I was intimidated because he was powerful. But when I went up to him, he was completely different. He’s enthusiastic about helping everybody, especially younger Muslims, to reach the position he’s in.”

- Mariam Hassan

According to Kasubhai, it is customary to address people in the courtroom by Miss or Mr.; however, these honorifics often come from assumptions.

Kasubhai felt as though people who were nonbinary or transgender were not given the space to present their best self in the courtroom, as they were in fear of how people would judge their gender identity. Therefore, to make his courtroom more accessible, Kasubhai has begun to request that people provide him with their honorific so he can correctly identify them.

Federal Magistrate Judge Allison Claire has worked on four panels with Kasubhai to educate other lawyers and judges about the importance of pronouns.

Claire, who was inspired to do work surrounding pronouns due to her experience as a lesbian woman in the legal system and her two nonbinary children, first found out about Kasubhai when she saw his article Pronouns and Privilege written in the Oregon Women Lawyers journal.

Claire says Kasubhai has been an inspiring partner while advocating for marginalized groups.

“He balances his own great intellectual rigor and commitment to the job we perform with a very open-hearted and personally authentic way of relating to other people and expressing his own values,” Claire says.

Kasubhai, while faced with challenges and marginalattaining is no finish line, but rather, an enduring commitment to capac-