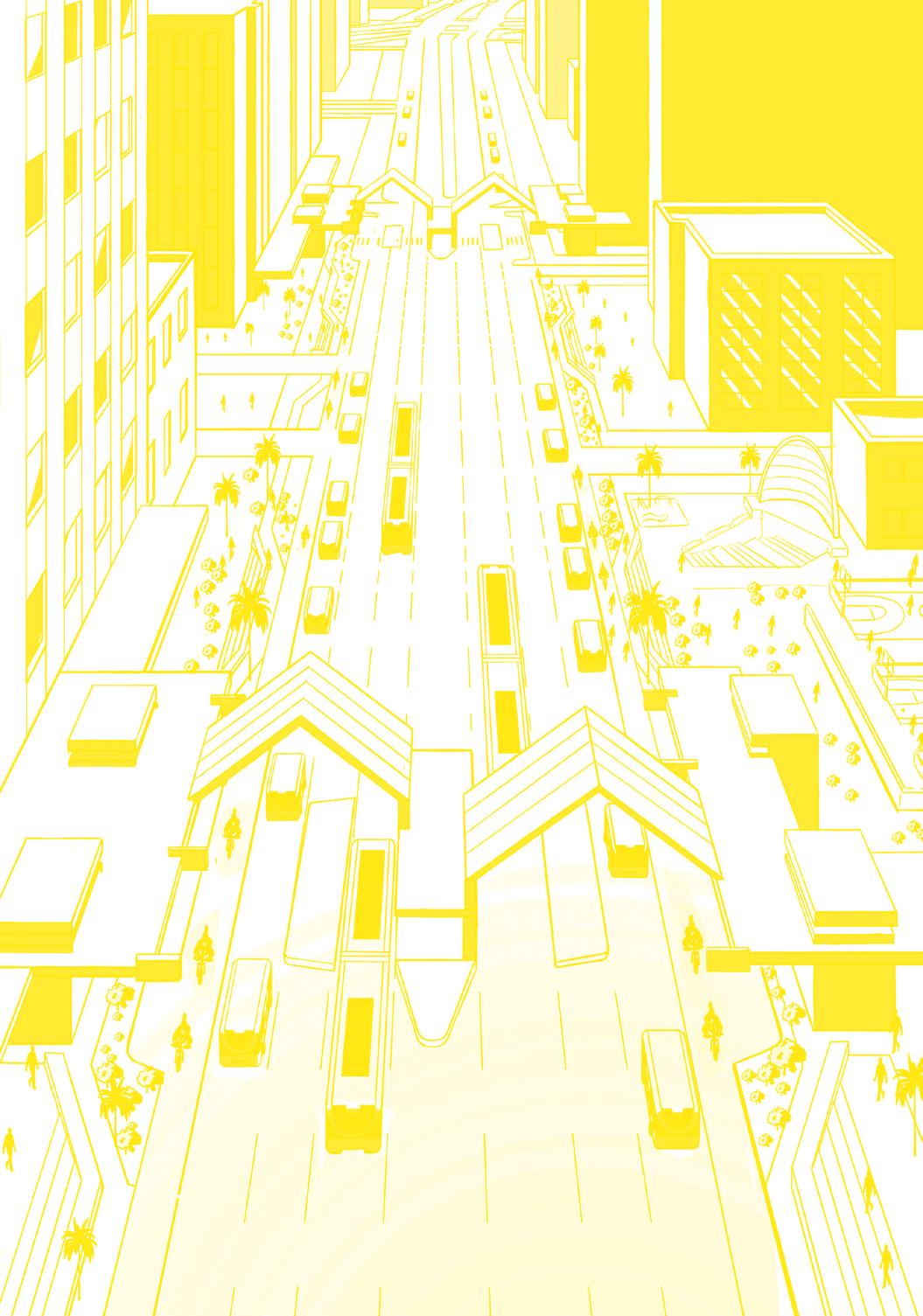

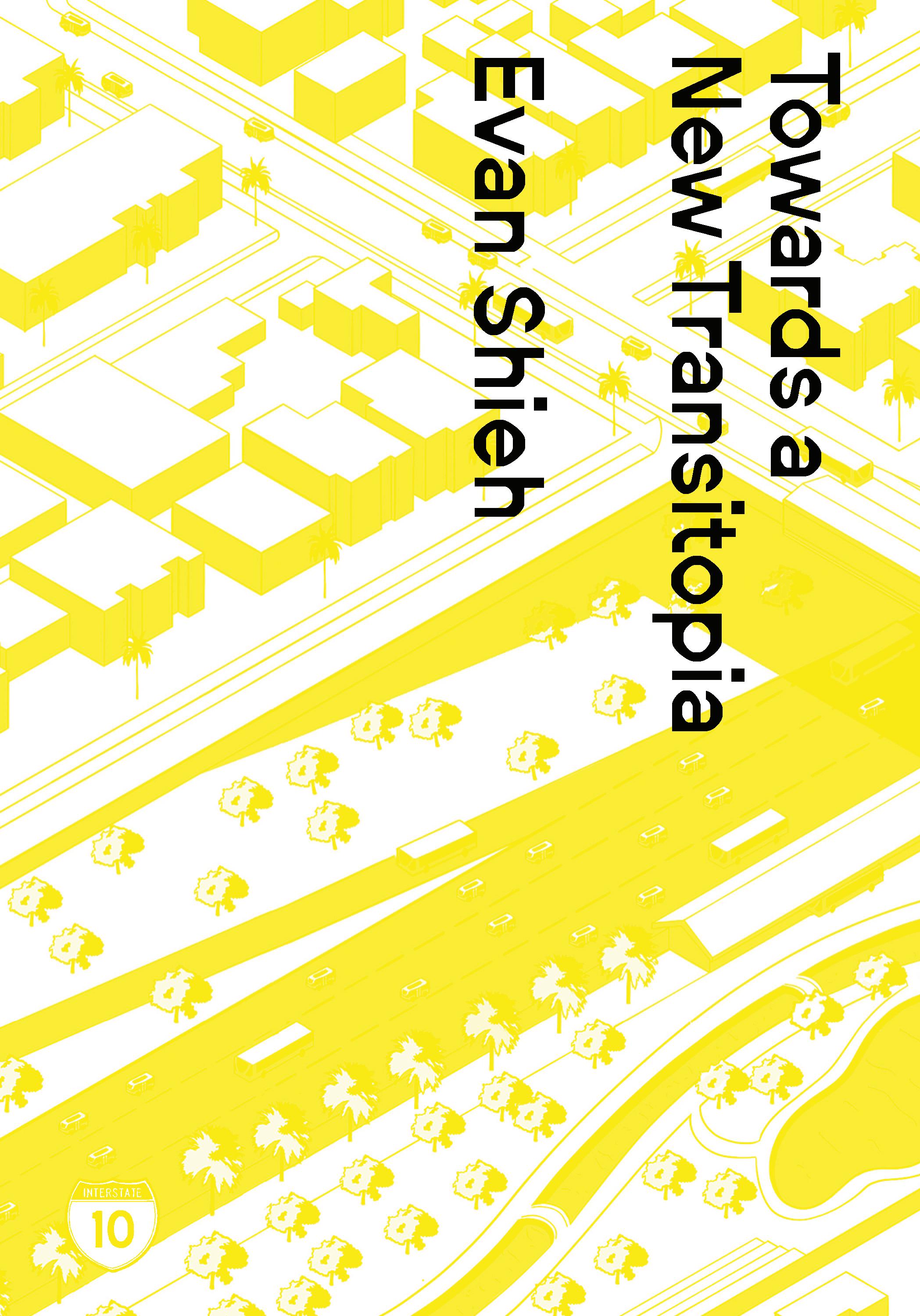

PrologueThis book envisions a near future, the year 2057, in which driverless vehicles are used to spur a paradigm shift from private automobile use towards automated mass transit and mobility-as-a-service. This vision, a model of metropolitan urban growth and the mobility experiences they enable, aims to reverse many of the most consequential negative spatial externalities that automobile-based urbanism has catalyzed in car-centric cities and their built environments. In envisioning this potential urban future through the eyes of the everyday citizen, this book contends that cities can transition from the Autopias of today, to the Transitopias of tomorrow. This is a big shift. Are cities and their inhabitants ready?

Drawing to Inhabit the Future

1

A Reflection on the Medium of World-Building

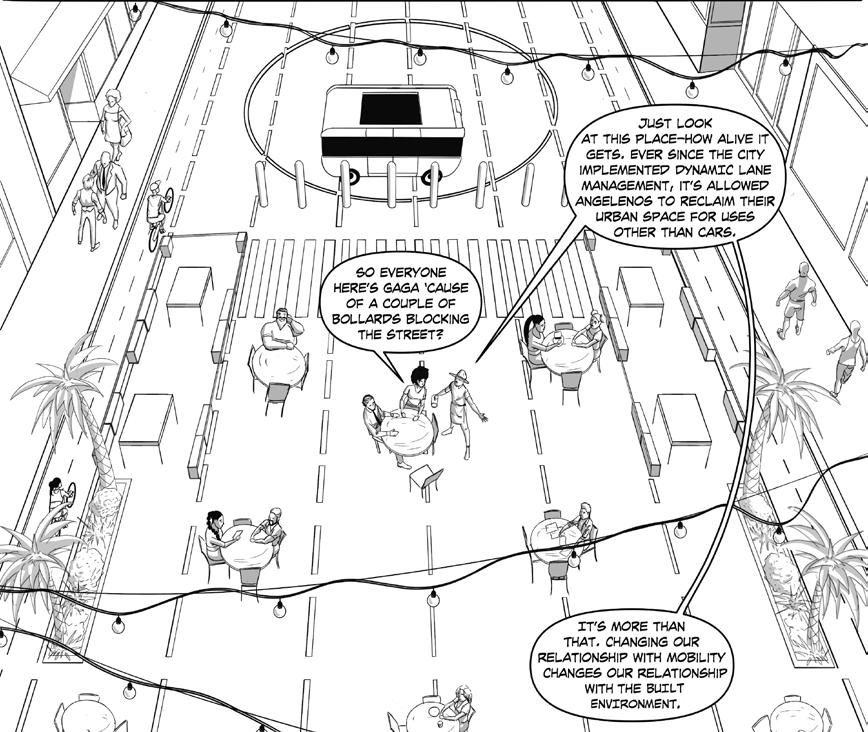

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) are beginning to appear on our roads. With them, are profound and transformative implications for the future of our cities. On one side, AV-utopists advertise that driverless technology itself will solve the mobility ills and issues of our present day. On the other side, AV-skeptics proclaim that automating our vehicles will lead to the demise of cities. At the forefront of this public discourse, debates around the present day effects of driverless technology rarely consider their long-term spatial impacts. Meanwhile, in the background, technology corporations and automobile manufacturers are racing to develop and implement AV technology on our city streets, but they are doing so without illustrating the potential urban impacts their decisions may ultimately lead to. While often marketed as a boon for cities, the business models that drive AV implementation may actually lead to opposite outcomes as Book 1 (The Framework) has discussed. At the same time, transportation regulatory agencies who are in positions to guide the deployment of AV technology have largely remained slow-moving and reactionary. What has become clear is that long-term visions for these potential driverless futures—the spatial environments, the mobility behaviors, and the passenger experiences they engender—are distinctly lacking in this contemporary conversation. In particular, the design and planning disciplines have largely remained silent. Yet, these disciplines provide unique and critical tools to shape how we view new technologies and envision how they could be integrated into our everyday lives. This act of visioning—the act of design and the drawing methods and visualizations that represent it—are powerful tools in a contemporary technology-driven conversation that is markedly lacking them.

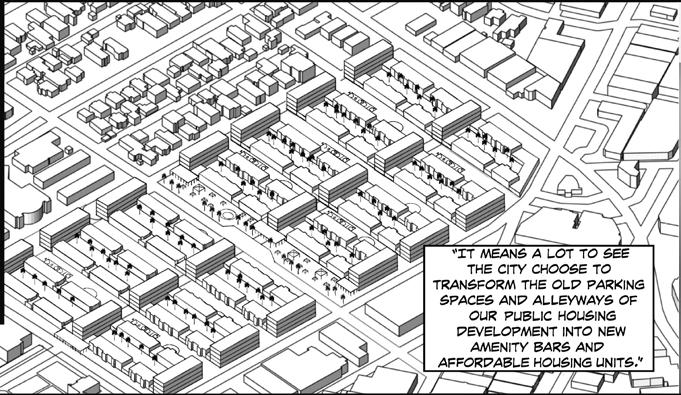

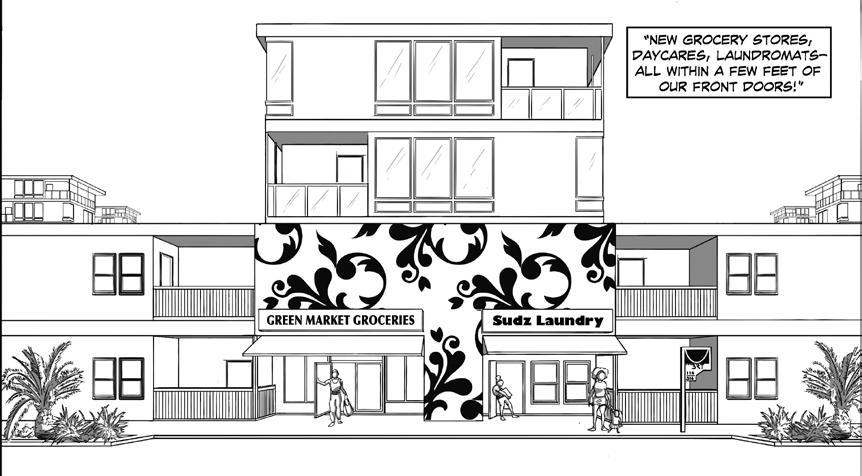

Rather than passively wait for a future to unfold, this book chooses to actively project a future instead. This visioning becomes an important counterpoint to alternative futures that market-driven AV companies have positioned themselves towards, and that their decisions may inadvertently bring about. The book’s vision for this future is one that has used driverless technology to reverse many of the negative effects that automobile-based urbanism has levied onto our cities and their urban environments in the 20th century. This is a future in which our urban environments are more human-centric, multi-modal, and environmentally sustainable—one in which our public spaces, mobility infrastructures, and urban form are better designed to facilitate those values. This is a future in which driverless technology is used to expand rather than compete with existing transit and transportation systems, while simultaneously addressing their flaws and gaps. This is a future in which moving around the city is spent in far less traffic and in more affordable, quicker, and convenient alternatives. This is a future that is not dictated by technology but one in which technology is strategically regulated to produce a better built environment.

Drawing that future is an important tool precisely in topics where technological innovation is disruptive and rapid because of the various undetermined futures that may result from these changes. It is only by drawing a potential future that we can extrapolate the determinative steps that lead us towards that outcome. It is also

Suburban Nuclear Family The Smith Family

Configuration Parents, Children

Socioeconomic Status

Upper-Middle

Residence Type

Single-Family Home

Residence Area Pasadena

Mobility Needs Commute, Errands

Traditional Transportation Modes Multiple Owned Cars

Composite Household Roommates Adam and Ki

Configuration Roommates

Socioeconomic Status

Middle

Residence Type

Mid-Rise Rental Apartment

Residence Area Koreatown

Mobility Needs Commute, Mobile-Work, Errands

Traditional Transportation Modes Multiple Owned Cars, Ride-Hailing

Extended Working Household

The Perez Family

Configuration Parents, Child, Grandfather

Socioeconomic Status

Working-Class

Residence Type

Multi-Family Public Housing

Residence Area

Boyle Heights

Mobility Needs

Long Distance Commute, Errands

Traditional Transportation Modes

Bus Transit, Para-Transit

Business Traveler

Mr. Gibson

Configuration Solo Traveler

Socioeconomic Status

Upper-Middle

Residence Type Hotel

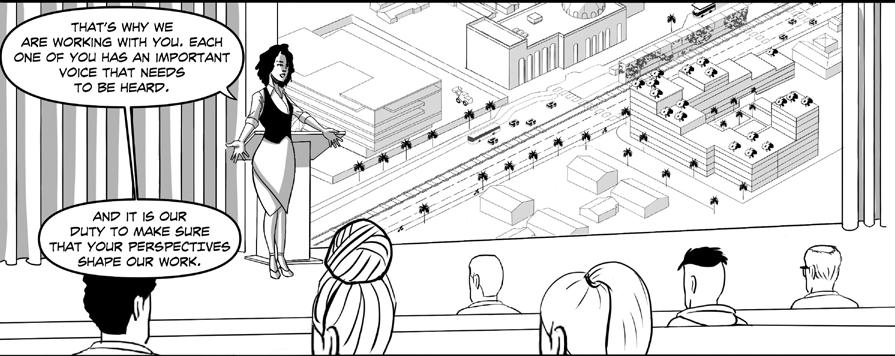

Transit Planner

Ms. Reynolds

Configuration

Public Transportation Figure

Socioeconomic Status

Middle

Residence Type

Multi-Family Townhouse

Residence Area

Inglewood

Mobility Needs

Multiple Destination Meetings

Traditional Transportation Modes

Rental Car

Residence Area

Crenshaw

Mobility Needs

Community Site Visits

Traditional Transportation Modes

Personal Car, Occasional Transit