Number within a Category.

Topic Full list on the back

1 Local Identity

WHAT’S ON A CARD?

Category

SOCIAL

Acharacteristicofindividualswhospatiallysharecertainvaluesand culturalexperiences.Includesstorytellingaboutlandmarks,events andtasteculture;describesthefeelingofbelongingtoaplace. Understandinglocalidentityasanintellectualandemotionalconstructwithlocal, regionalandglobalinfluencesenhancesplace-making.Itrevealscommunityshifts andevenadistrict’svulnerabilitieswhileembracingchangeincitizens’valuesand demographics.

Groupsofpeoplehavecertain“setsofaestheticandsocialnorms,patternsofchoices andmultipleidentities.”“Tasteculture”isthekeytocreatinginclusiveandsocially connectedplaces.(H.J.Gans)

Inmetropolisesandsmalltowns,landmarksandpublicgatheringplacescreatea strong,visiblesenseofcommunity,ownership,stewardshipandparticipation.

GUIDELINES

Urbandesignproposalsshouldreinforcelocalvaluesbyincludinghistoricalartifacts,publicart, symbolicstructures,popularculture,festivalsandcuisine.Small-scaleculturaleventsallowcitizensto remainlocalwhiletappingintothebroaderurbanrealm.

Definition is how the topic is used the context of urban design.

Description includes the meaning of the topic and its prominence and potentials for urban interpretations.

Citybrandingstrategiesthatencompasslocalstorytelling,awiderangeofstakeholdersand idiosyncraticandever-changingnarrativesofdailylifearekeystocreatingstronglocalities. Communitieshaveattachmentstospecificlocales,whichareimportantforrevitalizingneighborhood cultureandmicro-economyandpromotinghealing,creativity,citizenshipandsharedgoals.Feedback platformsareopportunitiesfordialogueandforsharingexpertise,resourcesandideas.

WELLNESS AESTETHICS DESIGN POLICY BEHAVIOR

Impacts & Actions

Explained on reverse

Guidelines include design methods, dynamics to consider, creative opportunities, key principles and related technical details, regulations and constraints.

1

INFORMATION & HOW TO PLAY

citymaking101.org ECONOMY D

WHAT’S IN THIS BO

6 Roleplaying Personas, 6 Categories of 101 Topics, and one Make A Topic

A GAMEBOARD for creating urban design guidelines, through stakeholder consensus for your specific public spaces.

Introduction

City Making 101 is a base of knowledge for everyone to participate in the design of their cities. It is also a lively role-playing game to co-imagine, debate, then build consensus on design guidelines specific to your public space projects.

The city is co-created and is at its best when realized as a collaboration between its inhabitants, organizations, producers and professionals capturing its unique and idiosyncratic urban culture—edited, revised, built upon, started over from scratch. City making is not singularly a technocratic venture. Its form and activities generate significant meaning, memories and emotional connections for its communities, residents and visitors alike. A city’s design is a diptych of practical and emotional intelligence. Many write love letters to cities having deep interpersonal and complex relationships.

Having practiced architecture and city design since 2002 in Istanbul, a city with thousands of years of urban history, I understand that the city is a rather plastic form—for better and for worse—where architecture can be practiced as “slow urban design.” The aim is for you and your community, through vibrant debate, to generate urban design guidelines that will serve as a starting point for co-designing the city with involved, knowledgeable and empowered citizens and professionals working in concert. The focus is on actions, results, descriptive solutions and strategy, not winners and losers.

Alexis Şanal, Project Founder

RememberThe city itself is a composition and a living dynamic of many complex, interconnected topics as well as simple, familiar and discrete parts. It is the craft and poetic design of the tangible and the intangible dimensions of cities that underpin their excellence.

3

WELLNESS DESIGN POLICY

IMPACTS are measurable effects addressasble in the greater social good towards livable, lovable and walkable cities for all.

WELLNESS Improves the mental, health, social and/or demographic well-being of the community.

QUALITY Adds value to the social and economic stability, attracts tangible and intangible capital, engenders stewardship, and is maintained.

AESTETHICS Have a recognizable identity, is coherent and is perceived and valued as attractive to the diverse interest of residents and visitors.

SUSTAINABILITY Retain relevance in change i.e. ecological, climate, social, economic, cultural sustainability. It reduces reliance on fossil fuels and leads towards equitable and inclusive city design.

ACTIONS are the effort or expertiese required to realize urban design excellence.

DESIGN Creative intervention, crossdisciplinary knowledge, proposal of integration or scheme specificity. Expertise are urban designers, architects, landscape designers, graphic designers, service designers, industrial designers, artists, community designers.

TECHNICAL Know-how to solve or overcome a problem or info-sharing to coordinate a design. Expertise are civic engineers, structural engineers, environmental engineers, technical guides for application and procedures.

POLICY Governmental and nongovernmental strategies and targets through laws or cooperation in terms of governance, resources, and dissemination of information. It requires the expertise of economists, sociologists, lawyers, policy-makers.

BEHAVIOR Advocacy or incentives/ de-incentives to advance social habits, citizen participation or changing perceptions. It requires social entrepreneurs, communication designers and advocacy groups.

HOW TO PLAY

Describe the Design Challenge

task is to define a design challenge. This challenge can be set with the help of players. They select the neighborhood/ district for the challenge and make sure all the players are familiar with the area (if need be, walk it, take photos/notes, share information and maps with the other players).

Preferably, meet around a table with enough space for the game board and three horizontal stacks of cards for each player.

If this is the first time the group is playing, they might opt for the Compact Game.

60-CARD COMPACT GAME

For beginners: Remove cards A20-28, B12-16, C4-8, D5-9, E9-11, F 16-28 from the deck before the game.

Provide a brief (+/- 5 minute) presentation about the specific area—its history, current state, issues and future prospects—with supporting visuals. The challenge can be as focused as a pocket park on a vacant lot or as general as solving a neighborhood trash management problem. It can look at ways to utilize your school campus in summer or to ensure quality public space in a new urban development. To visualize and keep the focus on the design challenge, it is helpful to have images or any other relevant material visible to all throughout the game. →

Imagine The Roles

Players use the Persona Cards to guide them through this process. They come up with their personas: age, profession, character, and purpose in participating in the design challenge. They act as if they are the character and uphold their purpose throughout the game.

Take 10 minutes to familiarize yourself with your persona. Facilitator should make sure there is a reasonable balance of persona types and every player confidently knows their character’s position.

Ask each player to describe their role to the group in two sentences, with an additional sentence on how they feel about the design challenge.

Start the Game

Residents could be; homeowners, renters, children, baristas...

Investors could be from the public or private sector, developer, large tenat, institution...

Experts could be; architects, engineers, ecologists, economists...

Local Government could be; mayors, social services, police, maintence workers... NGOs could be; naturalist NGOs, children with disabilities, humane society...

Deal the cards to each player, description side up, one by one around the table. Make sure the cards are in order. Note that 101 cards may not be divisible equally among players; some might end up with more cards.

Players, in character and focusing on the design challenge, review the topic and description on their cards.

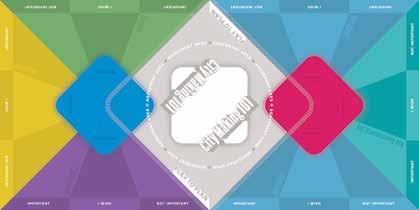

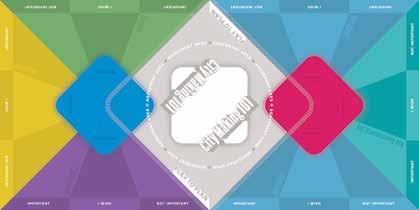

Separate the cards into IMPORTANT, NOT IMPORTANT or I WISH piles.

Players then put each stack, text side up, in front of them around the game board. The topics of all cards should be readable at a glance by every other player in the game.

First Round The Warm-Up

Going around the table each player presents their NOT IMPORTANT topics one-by-one. Present a topic card in one sentence then state in another sentence why they think this topic is NOT IMPORTANT, then place it topic-side-up in the center of the board.

If any other player thinks that card is IMPORTANT, they can take it and put it in their IMPORTANT or I WISH pile.

Do not go into details on cards just yet, keep first round focused on descriptions. Note that more than one player can claim one card is IMPORTANT. In that case, take a note to discuss on the next round.

When all players have presented their NOT IMPORTANT cards, all remaining cards in the center get turned art side up and stacked on the board’s NOT IMPORTANT square. →

7

6 PROPERTY BUSINESS PUBLIC SECTOR DEVELOPMENT Real Estate Offices Landlords Goverment Microentrepreneurs Start-Up Offices Big Companies Sport Clubs Libraries Museums Schools Building Companies Design Offices Cooperatives Contactors ENGINEERINGECONOMY DESIGN SCIENCE Transformation Civic Water Waste Developer Social Enterprise Financer Sociologist Landscape Design Industrial Design Urban Planner Architect Waste Management Ecology Climate Energy POLITICALMAINTENANCE POLICY EXPERTISE Political Parties Local Authorities Council Members City Mayors Developer Social Enterprise Financer Sociologist Animal Services Security Cleaning Infrastructure Social Workers Employment Offices Energy Offices Property Offices SOCIAL CULTURAL EDUCATIONECOLOGICAL Immigrant Communities Disabled People Festive Events Public Spaces Craftsmanship Heritage Conservation Public Performance Affordable Technology Accessible School Student Funds Free Books Sustainability Edible Gardens Recycling Rewilding

Second Round The Discussion

Players present their IMPORTANT cards. In this round, the aim is to convince the other players of the topic’s importance.

▪ All players are encouraged to voice their thoughts if they do not agree, or only partly agree, that the topic is important or if they think it is a good idea but not relevant to this design challenge. During the discussion, every player should state if they are in favor or against the topic according to their role and the design challenge. Other players are encouraged to review the card if they find the topic unfamiliar or want any clarity before offering their point of view.

▪ If every player agrees that the topic is IMPORTANT, the card remains in the center topic side up. If someone thinks it is NOT IMPORTANT, they state their case. The other players have the opportunity to persuade the player who is in disagreement.

▪ if a topic is discussed for too long or cannot be resolved, agree to disagree and move on, placing the card in the I WISH position on the board in front of the player who is most supportive of the topic; it will be revisited in the last round. Keep the game moving! It is recommended to present by going around the table one-by-one.

When all IMPORTANT cards have been assessed, the cards that remain get turned art side up and stacked on the board’s IMPORTANT square.

Third Round The Nitty-Gritty

Each player in order puts their creative thinking into ways to get their I WISH cards moved to the IMPORTANT pile. To convince the others of their topic’s merits, players can propose policy, design, social or enforcement solutions that address the concerns of the other players. Refer to ACTIONS and IMPACTS in your arguments.

This is the opportunity for the group as a whole to find solutions that support including the remaining topics in a design guideline specific to their design challenge.

If all players can find an agreed solution or strategy, the card is noted with the yellow note card and goes into the IMPORTANT stack. Cards in the IMPORTANT stack has to be unanimous. If there is still disagreement from any player, the card remains in the player’s I WISH pile. Collect all I WISH piles and place them in a stack, art side up, in the center circle of the board. →

FOR EXAMPLE

If someone thinks graffiti is a problem for historic buildings, you can discuss the line between vandalism and street art. Consider enforcement, creating additional surfaces for graffiti art, or even promoting a public awareness program that supports street artists and channels this creative energy into an alternative cultural movement. You can also use examples of success stories from real cities or experiences. Policy, behavior, technical and design solutions are ways to resolve disagreement. Also, new topic cards can be added like Murals or Vandalism to enhance the co-creation design guideline.

9

Game Finale The Round-Up

Now all the cards should be on the board in 3 stacks:

IMPORTANT NOT IMPORTANT I WISH

Remove all NOT IMPORTANT cards and place them back to the box.

Starting at the board’s upper left corner, place the IMPORTANT cards, topic side up (A, B, C, D, E, F), in columns from left to right.

Be sure each topic’s number and name is visible.

Next, do the same with the I WISH cards, placing them in columns to the right of the IMPORTANT cards. Then place, at the bottom of each column, any notes that came up throughout the game which was not included in the cards.

Your team can now take a photograph of your design challenge’s collectively-agreed-to design guidelines.

Wrap-up Activities

LOOK-AROUND—ask players to go around the room and look at the other team’s results. The players can discuss the differences in results and the ways the various roles may have influenced the city design strategies. Or if you are a single team, try a different design challenge and different roles and see the results.

SHARE—Each team can present the most debated topic, the topic that provoked the most curiosity/ inspiration/learning, and the topic that was the easiest to decide.

PROPOSE—Each team could propose a new topic(s) that would capture their discussion but was not in the base deck. Share with us @ imaginableguidelines.org so we can add to future editions.

NOTES FOR BEGINNER PLAYERS

— Use a 66 playing card deck

For players first experiencing city design topics and/or guidelines a compact deck will be more engaging. The 66 card deck is recommended for high school students, citizen initiatives and players whom want to play with a small group of friends.

— Select ALL of A Physical Elements and F Vitality cards as well as the first SEVEN cards of B Ecology. Time permitting; add C TechnologyInnovation, D Social Economy and E Governance cards after the second round. Then repeat the first and

second rounds before starting the last round. The suggested BREAK for introducing more cards is good timing for splitting between two class periods or a morning and afternoon session.

— We have observed that first time players need more time for different reasons. They are more likely to need to read the full text and citizen players often listen more intently to understand why the other roles find topics important or not important. Also, they may feel overwhelmed by too much information.

NOTES FOR ADVANCED PLAYERS

— Use in professional or university city-design context

Use the full deck for players who are university students in urban studies or architecture in +3 year studios and design professionals with municipal teams and NGOs already engaged in city design. If university students are in the 1st or 2nd year or other departments, we suggest starting with the Beginner Player Recommendations outlined above.

— Use blank topic cards to add new topics, not in the deck, as needed for your design challenge. Many design challenges will require additional city design topics.

— For very advanced players, start clustering and re-organizing the design guideline by priority of topics, clustering new categories, or re-writing specific topics per your

Co-Designing Livable, Lovable, Walkable Cities

Now you have experienced the process of generating a design guideline. The topic cards have much more information on the specifics of the design topic. You can also do further research on the topics and investigate different best-practice solutions or strategies. You are ready to reach out to the neighborhood organizations, local authorities and design professionals that can help you realize actionable solutions. You can now use your knowledge of city design topics to improve something in your neighborhood, prioritize the needs of the area for a new project or feel empowered to actively participate in the debates of your city.

design challenges’ context needs and considerations.

— For city-design and professional community development uses, players can play their own roles to realize a Shared City Design Guideline specific to their requirements.

NOTES FOR GAME FACILITATORS

— Minimum 12+ player parallel play.

— Up to 60-80 Players works well with 10 tables for 96 players use 12 tables. We do not advise to go beyond this number of parallel plays.

— Asess if your players are beginner or advanced players.

— Set-up tables and the separation of the playing cards prior to starting or players arriving.

— In big groups and community meetings place the visuals so all players have access throughout the play. The moderator/facilitator

can pre-set the multiple tables with the game boards and deck of cards in its circle.

— Keep everyone focused on the design challenge at hand and his or her specific role. Players easily get lost in trying to solve the problems of the city as a whole, which may distract them from the design challenge at hand as well as reaching any consensus.

— A good moment to take a class break, coffee/lunch break is before starting the last round.

— If your goal is community development, citizen participation or professional use, we recommend giving the last round a full 45 minutes to an hour to reach new design guideline proposals, new topic proposals and allow for a solid discussion of the more subtle and problematic aspects of the design challenge.

10 11

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Bain, L., B. Gray, and D. Rodgers.

2012. Living Streets: Strategies for Crafting Public Space. New Jersey, US: John Wiley & Sons.

Barton, H. 2009. Land Use Planning and Health and Well-Being.

Bristol, UK: WHO Collaborating Centre for Healthy Urban Environments.

Bill, M., and G. H. Greet. 2010. Site

Furnishings: A Complete Guide to the Planning, Selection and Use of Landscape Furniture and Amenities. New Jersey, US: John Wiley & Sons.

Bristol City Council Graffiti Policy. 2008. Bristol, UK.

Burton, E., and L. Mitchell. 2006.

Inclusive Urban Design: Streets for Life. Burlington, UK: Routledge.

Carmona, M., and S. Tiesdell. 2007. Urban Design Reader. Burlington, UK: Routledge.

Cervero, R., with G. Arrington, J. Smith-Heimer, R. Dunphy, and others. 2004. Transit-Oriented Development in America: Experiences, Challenges, and Prospects. Washington, DC: Transit Cooperative Research Program Report 102.

Child, C. M. 2012. “Fictive Landscapes.” In Urban Composition. New York: Princeton Architectural Press.

Chase, J. Crawford, M. Kaliski, J. 1999. Everyday Urbanism. New York: The Monacelli Press.

City of San Francisco. 2013. San Francisco Parklet Manual. http:// pavementtoparks.org/.

CityArt. 2012. Public Art Strategy. City of Sydney, Australia.

Complete Streets Chicago. 2013. Chicago Department of Transportation.

Cullen, G. 1961. The Concise Townscape. London: Architectural Press.

Douglas, C. C. G. 2011. “Do-ItYourself Urban Design

‘Improving’ the City through Unauthorized, Creative Contributions.” American Sociological Association annual conference, Las Vegas.

Downs, M. R., D. Stea, and E. K. Boulding. 1973. Image and Environment: Cognitive Mapping and Spatial Behavior. Burlington, UK: Routledge.

Ercins, G. 2009. VI. Ulusal Sosyoloji Kongresi, “Toplumsal Dönüşümler ve Sosyolojik Yaklaşımlar.” Adnan Menderes Universitesi, Aydın. Ewing, R., and K. Bartholomew. 2013. Pedestrian- and Transit-Oriented Design. Washington, DC: ULI, APA. Fisker, M. A., and D. T. Olsen. 2008. “Food, Architecture and Experience Design.” Nordic Journal of Architectural Research, https://vbn.aau.dk/ws/portalfiles/ portal/18074444/Food__Architecture_ and_Experience_Design.

Fitzpatrick, K., B. Ullman, and N. Trout. 2004. On-Street Pedestrian

Surveys of Pedestrian Crossing Treatments. http://nacto.org/ docs/usdg/on_street_pedestrian_ survey_fitzpatrick.pdf.

Florida, R. 2002. The Rise of the Creative Class…and How It’s Transforming Work. New York: Basic Books. Brilliance Audio MP3 Una edition.

Gans, J. H. 1975. Popular Culture and High Culture: An Analysis and Evaluation of Taste. New York: Basic Books.

Gehl, J. 1986. Life between Buildings. New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Gehl, J. 2010. Cities for People. London: Island Press

Gehl, J., and B. Svarre. 2013. How to Study Public Life. London: Island Press.

Gospodini, A. 2001. “Urban Design, Urban Space Morphology, Urban Tourism: An Emerging New Paradigm Concerning Their Relationship.” European Planning Studies.

Jacobs, J. 1961. The Death and Life of Great American Cities. New York: Random House.

Lang, T. J. 1994. Urban Design: The American Experience. New Jersey, US: John Wiley & Sons.

Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Social Space. Oxford: WileyBlackwell.

Leisure and Tourism-Led Regeneration in Post-Industrial Cities: Challenges for Urban

Design. IN SITU, London.

Lynch, K. 1960. The Image of the City. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Mercer, C. 2006. “Cultural Planning for Urban Development and Creative Cities.” Shanghai_cultural_planning_paper.

Mikolet, A., and P. Moritz. 2011. Urban Code: 100 Lessons for Understanding the City. Zurich: MIT Press and gta Verlag, ETH. National Association of City Transportation Officials. 2013. Urban Street Design Guide.

New York City Department of Transportation. 2009, Street Design Manual, Furniture.

Pedestrian Facilities Guidebook Incorporating Pedestrians into Washington’s Transportation System. 1997. OTAK.Peponis, J., C. Zimring, and Y. K. Choi. 1990. “Finding the Building in Wayfinding.” Environment and Behavior 22(5): 555–90.

Plothnic, A. 2000. The Urban Tree Book: An Uncommon Field Guide for City and Town. New York City, US: Three Rivers Press.

Public Art & Urban Design Interdisciplinary and Social Perspectives Waterfronts of Art III. http://www.ub.edu/escult/epolis/ WaterIII.pdf.

Public Space Design Guide Furniture. http://richmond. gov.uk/psdg_chpt5.pdf.

Rainisto, K. S. 2004. “Success Factors of Place Marketing: A Study of Place Marketing Practices in Northern Europe and the United States.” Doctoral diss., Helsinki University of Technology, Institute of Strategy and International Business.

Rossi, A. 1982. The Architecture of the City. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Snyder, A. 2022 “The designed and the ad hoc: dynamic remakings of street space in New York City.” Architecture_MPS. Vol. 23(1).

Speck, J. 2012. Walkable City: How Downtown Can Save America, One Step at a Time. New York: North Point Press.

Tan, E. 2014. Negotiation and Design for the Self-Organizing City: Gaming as a method for Urban Design. Architecture and the Built Environment Journal. Delft: Netherlands.

Transport for London. 2004. Making London a Walkable City: The Walking Plan for London.

Vendor Power: A Guide to Street Vending in New York City. 2009. CUP. https://www.wiego.org/ sites/default/files/resources/ files/United-States-of-America-AGuide-to-Street-Vending-in-NewYork-City.pdf

Watson, I. 2001. “An Introduction to Urban Design.” Planning Commissioners Journal 43, 1-7.

Wekerle, G. 2000. “From Eyes on the Street to Safe Cities [Speaking of Places].” Places: Design Observer 13:1.

Whyte, W. H. 1980. The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. New York: Edwards Brothers.

Whyte, W. H. 1988. City: Rediscovering the City Center. New York: Doubleday. World Health Organization. 1999. Towards a New Planning Process: A Guide to Reorienting Urban Planning towards Local Agenda 21. Copenhagen: Regional Office for Europe. World Health Organization. 2013. Make Walking Safe: A Brief Overview of Pedestrian Safety around the World. World Health Organization. 2013. Pedestrian Safety: A Road Safety Manual for Decision-Makers and Practitioners.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

ADA Americans with Disabilities Act

CAD ‘kaad’ computer-aided design

CO2 carbon dioxide

DIY do-it-yourself

HVAC H’vack’ heating, ventilation and air-conditioning

ISO ‘eesoh’ International Organization for Standardization km Kilometers

LDU localized development unit

NRC noise reduction coefficient

NGO nongovernmental organization

SRI solar reflectance index

UN United Nations

WHO ‘Hoo’ World Health Organization

13 12

We make playful tools for city making driven by a belief that if we want people to participate, we need fun, engaging, memorable and accessible ways to learn about urban design.

FOR YOU

Make your own cards. Our team is here to make more topics, categories and playful tools specific to your needs. Do not hesitate to reach out to our development team at @CityMaking.101 or imaginableguidelines @gmail.com.

VISUAL CULTURE

CONTRIBUTORS

PROJECT FOUNDER

OPEN URBAN PRACTICE openurbanpractice.com

Project Founder

Alexis Şanal Researcher

Semra Horuz

Project Coordinators

Dilşad Aladağ

Muhammad Abdullatif

Ulufer Çelik

All images have been created on Discord MidJourney and ChatGPT in the spirit of the city making visual legacy, an aesthetic and form of collective imagination. The visuals are curated to be clearly AI generated and represent the diversity of influences in the canon of urban design, representations of cities, cultural production influencers and timely emergent practices.

This content is possible because of the expertise and knowledge of many people who were asked to contribute and write topics for the Istanbulspecific edition in 2018. In city editions, our aim is to hear specific voices and perspectives of the professionals, experts, academics, practitioners and organizations that make that city today. In this edition, the texts are for you to reimagine your own voice and adapt cards for your public projects, communities and cities.

ORO Editions

Publishers of Architecture, Art, and Design

Gordon Goff: Publisher

www.oroeditions.com

info@oroeditions.com

Published by ORO Editions

Copyright © 2024 Alexis Sanal and ORO Editions.

Ahmet F. Yenice Interns

Julie Brun, Keimpke Zigterman

Graphic Design

Okay Karadayılar

Visual Curators using Midjourney and ChatGPT

Metehan Özcan, Selva Gürdoğan, Esra Kahveci, Alexis Şanal Illustrations

Mrinë Godanca

Editor

Erica Olsen

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying of microfilming, recording, or otherwise (except that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the US Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publisher.

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Topic contributors for 2018 Istanbul Edition—Alison B. Snyder (F2), Andrew Jones (A19), Andy LaRaia (A27, F12, F21), Ansel Mullins (F23), Arzu Erturan (F4), Arzu Nuhoğlu (B9), Candan Türkkan (F8, F09, F22), Deniz Aslan (B2, B3), Elif Fettahoğlu (F28), Elif Kılıç (F17), Erdem Üngür (E5, E6), Eren Tekin (F7, F11, F16), Erenalp Büyüktopçu (F1), Gökhan Karakuş (A24, B15), Görsev Argın (F18), Hendrik Bohle (A26, F26), Irem Coşkun (F20), Irmak Turan (B6, B12), Istanbul Running Forces (B14), İyiOfis (A25, F15), Linda Shahinian (General Editor). Maura Kelly (A17), Merve Akdağ (A7), Merve Bedir (F24, F25), Nazlı Tümerdem (A8), Nextistanbul (E10), Onurcan Çakır (F20), Özlem Ünsal (E03), Özlem Yalım (A18), Samarjit Ghosh (F19), Sera Tolgay (B10, E5), Serhan Ada (A22, E11), Sivil Yaya Girişimi (A15), Sokak Bizim (A1), Urban Tank (F05), Zeynep Dal (B8), Zeynep Turan Hoffman (F10).

Chief Editor: Alexis Şanal

Book Design: Okay Karadayılar

Project Manager: Jake Anderson

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First Edition

ISBN: 978-1-961856-00-4

Color Separations and Printing: ORO Group Inc.

Printed in China

ORO Editions makes a continuous effort to minimize the overall carbon footprint of its publications. As part of this goal, ORO, in association with Global ReLeaf, arranges to plant trees to replace those used in the manufacturing of the paper produced for its books. Global ReLeaf is an international campaign run by American Forests, one of the world’s oldest nonprofit conservation organizations. Global ReLeaf is American Forests’ education and action program that helps individuals, organizations, agencies, and corporations improve the local and global environment by planting and caring for trees.

CONNECT WITH US ON SOCIAL MEDIA @citymaking.101 ACCESS VIA OUR WEBSITE; TEACHING RESOURCES, PRINT YOUR OWN CARDS, PERSONAS & MUCH MORE citymaking101.org

GUIDELINES

Sun and Shadow

The diurnal cycle and rhythms animating city form and the natural context and affecting the vitality and usage of a place on a seasonal and an hourly basis.

The sun’s variables affect numerous aspects of urban design, human comfort, energy use, building design, and massing as well as public program planning.

The color, angle, duration, intensity, and other qualities of sunlight, as well as length and contrast of shadows, are specific to cities, depending on geographical position and prevalent atmospheric effects like cloud density, fog, and smog.

The sun’s radiance, warmth, and light in winter, and its heat and glare in summer, are integral to the spatial, experiential and material components of the urban realm. The rich vocabulary associated with light demonstrates the power of sun and shadow in our emotional and cultural experiences: blaze, brightness, brilliance, glare, glow, illumination, incandescence, luminosity, radiance, umbra, dimness, dusk, gloom, murkiness, obscurity, somberness.

Basic parameters of urban design include design of streets and public places with the duration and direction of sunlight in mind, including morning, afternoon, and evening as well as solstice and equinox angles.

Solar reflectance, glare, absorption, radiation properties, and energy-harvesting potentials should define material selections in an urban realm. CAD and 3D modeling simulations can shape decisions. Sun and shadow also significantly impact a street’s transparency and reflection on glass surfaces.

High-density public spaces and pedestrian paths with intense spill-outs should consider the constraints and opportunities of orientation, overheating, and building heights in their design.

Coniferous and deciduous tree species, canopies, promenades, arcades, seating, water features, and the choreography of movement in the daily routine are design opportunities to celebrate cultural relationship with sun and shadow and ensure human comfort.

WELLNESS QUALITY AESTETHICS SUSTAINABILITY

DESIGN TECHNICAL

citymaking101.org ECOLOGY B 1

GUIDELINES

Urban Heat Island Effect

Refers to air and surface temperatures that are higher than in nearby rural areas due to the surface radiation from roads and buildings forming an “island” on the earth’s surface.

Urban heat islands contribute to human impact on climate warming. Considering that +/-35 percent of urban land is made up of public space, selection of materials can measurably reduce unwanted heat gain.

The Solar Reflectance Index (SRI) is the amount of a material’s absorption of solar and infrared radiation. Materials with a high SRI are likely to absorb and radiate less heat. Building and landscape elements with higher SRI levels help to reduce the heat island effect.

While summer heating creates a negative effect, in winter heating is required. Negative and positive impacts of surface radiation and seasonal needs should be considered when selecting materials. Effective surface materials prevent high demand for air conditioning and heating that increase heat exhaust, fossil fuel resources, and energy consumption.

Hard- and soft-scape specifications can be designed to mitigate urban heat island effect without compromising on safety and energy consumption while increasing human comfort.

Hardscapes with no shading control can utilize materials having +50 percent SRI and be designed with high SRI values, low light reflectivity, permeable surfaces, and light tones.

Surface materials such as sand or light natural stone, washed concrete with exposed light-colored aggregate (±50 percent SRI), common granite (±40 percent SRI), and terracotta/brick (±50 percent SRI) should be selected carefully. Adding contrasting patterns to natural concrete, light natural stone (±60 percent SRI), or white stamped asphalt (±70 percent SRI) could provide desired SRI while reducing glare and offering contrast.

Tree canopy coverage and a variety of vegetation are fundamental for heat island reduction. Bioswales, permeable paving, green parklets, tree planting, and more parks all help reduce temperatures.

WELLNESS SUSTAINABILITY

DESIGN TECHNICAL POLICY

citymaking101.org ECOLOGY B 11

GUIDELINES

Litter

GOVERNANCE

Waste, refuse, and trash—like cigarette butts, paper, cans/bottles, wrappers, and single-use packaging—improperly disposed of at inappropriate locations.

Cities’ waste management services are often insufficient to collect litter, especially when trash cans are sparse and many products have single-use packaging.

Litter costs millions of dollars annually and negatively impacts businesses, tourism, real estate value, and safety perceptions. Littering is viewed as antisocial behavior, not littering as a core responsibility—so much so that it’s one of the first citizenship themes we learn in school.

Litter is often cited as a measure of social decay as people have a negative association with litter; the more we see a brand name as litter, the less we buy that product.

Awareness campaigns by public and private institutions, driven by evidence and quantified data, are key to changing littering behavior. Methods to reduce litter can include zones for measuring the quantity of litter and causes of improper disposal and taxing companies that produce commonly littered products like cigarettes, chewing gum, and beverages.

Influencing consumer choices can reduce litter and affect product choice as every citizen can be a generator and a cleaner of their own litter, while community-based citizen maintenance partners can offer (limited) services. Our on-the-go culture impacts the type of litter consumers are burdened with disposing of.

Business incentives for packaging solutions and product stewardship can be supported by tax arrangements, especially for street food, takeout, and junk food.

Waste products are potential sources of individual, collective, or industrial innovations. The basic strategy is to create less waste and recycle more, especially for materials like paper, plastic, and glass.

WELLNESS QUALITY AESTETHICS SUSTAINABILITY

DESIGN TECHNICAL POLICY BEHAVIOR

citymaking101.org

E 6

PROPERTY BUSINESS

Real Estate Offices

Landlords Goverment

Microentrepreneurs

Start-Up Offices

Big Companies

PUBLIC SECTOR

Sport Clubs

Libraries

Museums

Schools

DEVELOPMENT

Building Companies

Design Offices

Cooperatives

Contactors

•••

•••

•••

•••

SELECT a ROLE from the suggestions or make-up an alternative for as your player’s persona.

USE pencil to write or use a post note.

NAME AGE

OCCUPATION

MOTIVATION Why are you here?

| PUBLIC LIFE | ALTERNATIVE MOBILITY | KIDS | SENIOR HEALTH | VIBRANCY | POLLUTION | | WALKABILITY | SAFETY | SECURITY | TRUST | INDEPENDENCE | CHOICE | COMMUNITY | EQUALITY | | ORDER | ACTIVITIES | CREATIVITY | INTEGRITY | LEARNING | HERITAGE | EFFICACY | •••

ENGAGEMENT How long have you been a part of this community?

INFORMATION What information do you bring to the design?

GOALS What do you aim to realize in this design challenge?

ATTITUDE What does your character feel about this design challenge?

| EXTROVERT | INTROVERT | OPEN-MINDED | CURIOUS | VIVID | INDIGNANT | HOSTILE | | INDIFFERENT | DISCOURAGED | SELFLESS | ADVENTUROUS | HESITANT | NOSTALGIC | CRANKY | | FRIENDLY | EMPOWERED | INVOLVED | MELLOW | COOPERATIVE | SUPPORTIVE | NURTURING | | EMPATHETIC | APATHETIC | SELFISH | •••

INVESTOR

INVESTOR