UTHOR S

UTHOR S

I started to ask historians for expanded content about women, people of color, and African Americans who had held prominent positions and impact in the profession. Over and over again, the answer was, “I don’t know.”

When I started this career, I had no idea how many women and people of color were behind the iconic buildings that I have come to know and love. With the benefit of experience, I realize that it’s quite contrary to our profession to even talk about an architect in an individual sense. We work in teams—often large and rotating—and not everyone gets credit. Additionally, our projects are long-term, sometimes dragging on for years, if not decades, from when fresh ground is broken to when the ribbon is cut on the front door. We are built to focus on legacy because, if our work is worth its salt, the built environment will be our proof of concept. Our grandchildren will roam halls we built and our great grands will take photos of towers we once penned from our imagination.

Like all creators, architects expect our work to speak for us. However, there are a few things about that idea that simply do not work in this day and age. Just like a photographer gets public credit for a moment well captured, so, too, should architects be named for the benefit of the people who live and work in the spaces they design. In theory, this is simple. In reality, naming is much more complex.

When I won the coveted Whitney M. Young award in 2021, I was elevated to the American Institute of Architects (AIA) College of Fellows. The archivist at the AIA confirmed that I was the youngest African American to reach the height of being a fellow. Of over 115,000 architects in the United States, there are only 145 Black American fellows as of 2022. By my count, I was the 21st Black American woman named in the AIA’s 167-year history. While incredibly grateful for the acknowledgment of my own work, my immediate thought was to acknowledge upon whose shoulders I stood.

I started to ask historians for expanded content about women, people of color, and African Americans who had held prominent positions and impact in the profession. Over and over again, the answer was, “I don’t know.”

Of course I was disappointed, but I wasn’t surprised. In fact, I only became more determined to uncover these missing pieces of history. After all, that’s what my traveling activation exhibition, “SAY IT LOUD,” had been about in the first place. I wanted to revise the narrative, write architects back into the stories told about the work they produced, and free diverse designers from the cloak of invisibility common in our profession to claim their laurels—once and for all.

In a profession where people’s work speaks for them, it’s not shocking that architects’ identities are typically muted as a practice. But right now. At this moment. In a post–George Floyd America, invisibility is tantamount to erasure. And erasure is, well, racist.

Erasure is a sensitivity that sits close to my heart. My first architectural job was as an intern working on the African Burial Ground National Monument project in Manhattan. When I initially joined, Aarris Architects under the leadership of Rodney Leon and Nicole Hollant-Denis the firm was one of five semi finalists in the competition to design this historic project. The competition was still on; the five finalist groups were required to travel to all five boroughs to present their respective concepts to members of the general public for feedback.

We had a booth set up with models and flyers to share during our presentation. The community would then make comments on the projects which were documented and shared with us. These surveys would inform the design and allowed the team to improve upon the final design submission. Ultimately our team won the project. It was a fantastic to be part of the winning team early in my career. More importantly, I learned from the very start that architecture should be a community engagement process. The historians estimated the remains of 419 enslaved African people and over 500 artifacts were buried on the lot itself, and that an estimated 15,000 additional remains were interred all across downtown Manhattan.

Thanks to Rodney and Nicole I also learned about cultural erasure and how architecture can serve as a tool to address historical injustice. It is an issue that sits close to my heart. Most people do not know that New York City was built on the backs and bones of our ancestors—not just figuratively or spiritually, but I mean quite literally—architecturally.

On the south wall of the memorial is inscribed a map of the entire African burial ground expanse. Within that boundary exists an estimated 15,000 remains of African people in proximity to City Hall and multiple Federal Buildings. I couldn’t help but recognize that the numerous architects and builders who excavated the foundation of those iconic buildings most likely came across African remains and decided to build anyway. I’m proud to have been part of erecting a monument—the only one of its kind—to the enslaved Africans who toiled to build a city now known as the greatest city on earth. It is the only place where those souls will ever get their flowers. I don’t take it lightly and I will never forget that first project.

That was the foundation of my career, but there’s so much more under the surface. My experience working on this project as an intern took place just 10 years after a random passerby first implanted the idea of architecture in my brain. As I was drafting a mural on the wall at Camp Pomonok in Queens, a man stopped for a second to watch me work. “You can draw straight lines without a ruler. That’s a great skill for an architect to have,” the man said as he continued his journey.

In a profession where people’s work speaks for them, it’s not shocking that architects’ identities are typically muted as a practice. But right now. At this moment. In a post–George Floyd America, invisibility is tantamount to erasure. And erasure is, well, racist.

It had never occurred to me that I wanted to be an architect. I had never met another architect. No one in my family was an architect, but when this stranger said it, I knew something about this identity felt true. Over time, with my persistence, my mother signed me up for a “what’s an Architect” seminar, where I was the only girl. Blind to the reality that this was not an aberration, I slowly began to identify myself within the profession. In high school, I learned that 80 percent of the New York City skyline was built by Pratt Institute alumni, so I was determined to get in and to excel there. At the time, getting that admissions letter felt as important to my 18-year-old self as accepting the Whitney M. Young Jr. Award would later feel at age 38.

Yet, faster than I could spell the word “architect,” my commitment was tested. During my first few days at Pratt, the Architecture History professor began the lesson by looking around the classroom. As he eyed nearly 60 students, he asked only two of us to stand. He announced that neither of us would become architects because we were Black and we were women. It is fair to say that you could have knocked me over with a feather.

Never before had I experienced someone weaponize my gender and race against me. This professor clearly didn’t know me very well.

Did I falter in my commitment to the field?

Did I doubt my identity as an architect?

Did I even question whether Pratt was for me?

Much to that racist’s chagrin, not for a single second!

I was surprised that out of that full classroom only two of us were Black women. I was simmered and stewed in the silence of my peers—all but one. “You better not let that be the reason you quit. Prove him wrong,” Simon See nudged. And with that, it was game on.

In that very moment I realized that I was not just representing Pascale, the individual. I was then, and still am, representing my gender and my ethnicity. The only difference is that back then I felt shackled by the burden of showing up and showing out at every instance. I never wanted my actions to be the reason why the next person was denied an opportunity. With the benefit of time and perspective, now I welcome the responsibility and stand firm in my purpose. I have the goal of being the reason why those opportunities are multiplied. After all, my victory could not simply be becoming an architect; I had to change the profession completely. In my darkest hours, I have revisited that moment in that classroom just as many times as I’ve come back to the map of the African burial ground. I never worried about how I would gloat on graduation day, but I did worry about how many other aspiring architects’ hopes that professor had killed and how many careers he had quietly buried throughout his tenure.

Unlike other creators who can be self-taught, architects cannot be architects unless we are credentialed. Our professors are not just mentors, they are gatekeepers. Learning institutions and peer organizations are not just support systems, they are the professional networks within which careers are built or broken. Rather than guess how many other women and BIPOC students that one professor scared away, I set out to kill two birds with one stone. I want classrooms all over the globe to be full of aspiring architects—indigenous, Black, women, people of color, LGBTQI+, and intersectional—architects who represent the diversity of our world. To inspire boardrooms and architecture studios full of people who look like me, I decided to craft a visible representation of all the people on whose shoulders I stood.

I started collecting data on women and BIPOC architects and designers around the world, not just to prove my former professor wrong, but also to give folks their flowers—hopefully while they still have time to smell them.

For over six years, I have gathered over 1,000 diverse designers’ profiles from 40 states (80 percent of the U.S.) and 25 countries all over the world. The ‘SAY IT LOUD’ exhibition was the physical manifestation of these findings. I took that show on the road, and to date we have held 48 exhibitions around the world. I am proud of what these exhibits have done and the communities we have engaged with, and yet my question has always been: what next, what else can I do?

Architecture is all around us, shaping our daily experiences and influencing our perceptions of the world. From the gravity-defying skyscrapers that make up cityscapes and museums and cultural centers that showcase the best of human achievement, to the humble community center where we take our kids to basketball practice and vote in elections, to our very own homes, architecture is something we encounter on a daily basis. Yet, despite its ubiquitous nature, the field of architecture has been plagued by a lack of diversity and representation, with people of color and other minority groups being vastly underrepresented in the profession. It’s time to change that.

By bringing the diversity of architecture to the forefront of people’s consciousness, we can help foster a greater appreciation for the many ways in which architecture impacts our lives. Whether it’s through highlighting the work of diverse architects and designers or showcasing the many different styles and approaches that exist within the field, we can help to create a more inclusive and equitable world.

Indeed, studies have shown that diverse teams are more innovative and effective, and that a diversity of perspectives and experiences is essential for driving progress and solving complex problems. As our world becomes increasingly diverse and interconnected, it’s clear that we need a diversity of visions and voices in order to create a better, more just, and more sustainable future.

This book is divided into four chapters, with each chapter featuring the personal story of an award-winning, diverse designer. In these chapters, the designers share their experiences of working on projects that sparked their interest in the design profession, as well as the mentors who helped guide them and sustain their commitment to their careers. Through these personal accounts, readers will gain insight into the diverse perspectives and experiences that contribute to the field of design.

This book is a carefully curated selection of some of the best work in the field, showcasing the talent and creativity of a range of designers from different backgrounds and cultures. While paying homage to those who came before through the essays, this book pulls double weight as a recruitment tool—a billboard and a beacon for people—young, old, women, immigrants, people of color, gender and sex notwithstanding— who are not sure if this profession is open to their talents.

I—and the architects you will meet in the subsequent chapters—are here to say it loud, “Hell yeah!” Representation matters.…And so do flowers.

TION

This book confronts the historical underrepresentation of women and BIPOC designers in architecture, a disparity starkly evident in both academia and media. It illuminates the obscured contributions of these diverse creators and challenges the systemic erasure that has long plagued the profession. This endeavor is not merely an academic pursuit; it’s a vital correction to the architectural narrative and a commitment to reshaping our understanding and appreciation of architectural diversity.

Erasure in architecture represents more than a lack of recognition; it’s an active dismissal of significant voices and contributions that have shaped our environments. This book boldly provides a comprehensive overview of these challenges, traversing the realms of Cultural, Institutional, Residential, and Master Planning typologies. Each segment of the book tells a story of exclusion and recognition as it relates to documentation, highlighting the struggle and resilience of marginalized architects.

By presenting a detailed exploration of historical biases and societal injustices in architecture, this book establishes a narrative that is as informative as it is transformative. It celebrates the underrepresented and acknowledges the overlooked, setting a new standard for inclusivity and representation in architectural history. This is not just a recounting of the past; it’s a definitive statement on the need for a diverse, equitable, and creatively rich architectural future. Through this work, we provide a blueprint for an architectural discourse where every voice is heard, every contribution is valued, and the full spectrum of creative expression is showcased.

The erasure of women and BIPOC designers in architecture is a multifaceted issue, and one deeply rooted in the profession. This systemic neglect goes beyond mere oversight; it’s an active dismissal of contributions that have significantly shaped our built environment. Academia and media, traditionally the gatekeepers of architectural history and discourse, have often perpetuated this neglect.

This phenomenon manifests in various ways. Educational curricula in architecture schools, for instance, have historically prioritized Western, male-dominated architectural narratives, leaving little room for diverse voices. Women and BIPOC architects, despite their groundbreaking work, have been largely absent from textbooks and lectures. The media, too, plays a role in this narrative exclusion. Architectural publications and mainstream media have often overlooked the works of diverse architects, instead favoring those who fit into a narrow, established archetype of architectural success.

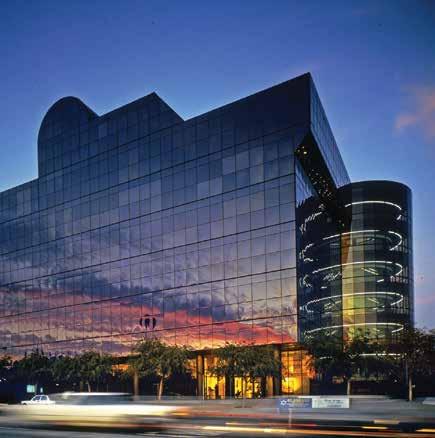

Notable examples, like Norma Merrick Sklarek, the first African American woman licensed as an architect in California, illustrate this point. Sklarek’s significant contributions to projects like the Pacific Design Center have been largely unacknowledged in popular architectural histories. Another case is Mexican-architect Tatiana Bilbao, whose socially responsible and environmentally sensitive designs challenge the Western-centric focus of the field but receive limited recognition.

By examining these and other cases, this section of the book not only highlights specific instances of exclusion, but also delves into the mechanisms of this systemic erasure. It’s a critical examination of the structures within academia and media that have maintained this one-dimensional narrative, and a call to action for a more inclusive approach to celebrating architectural history.

This section of the book delves into the specific architectural typologies of Cultural, Institutional, Planning, and Residential design, and how they have historically contributed to social injustices. Each typology, mirroring societal biases, has served as a vehicle for inequality. For instance, institutional architecture, such as government buildings or schools, has often embodied and reinforced power dynamics, sometimes marginalizing certain communities.

Residential architecture, too, has played a significant role in shaping societal structures, with designs that have often reflected and perpetuated socioeconomic disparities. Urban planning decisions have at times led to the segregation of communities, impacting access to resources and opportunities.

Cultural architecture, encompassing museums and cultural centers, has the potential to either celebrate diversity or, conversely, uphold a singular cultural narrative. This section will use historical examples to illustrate how these typologies, through their design and implementation, have either contributed to or challenged social injustices. The aim is to provide a nuanced understanding of how architectural decisions reflect and influence societal values and biases.

This book introduces the vital concept of liberating architectural history from its traditionally biased narratives. This shift is not just about correcting historical records; it’s a transformative act that redefines how we perceive and value architectural contributions. The significance of this liberation lies in acknowledging and celebrating the diverse, often overlooked voices in the field. By bringing these narratives to the forefront, we challenge the traditional, singular perspectives that have long dominated architectural discourse.

The role of documentation and representation is crucial in this context. Accurate and inclusive documentation of architectural works ensures that the contributions of all architects, regardless of race, gender, or cultural background, are recognized and preserved. Representation in media, literature, and academic syllabi further reinforces this change, enabling a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of architectural history. This process of liberation is not just about adding names to a list; it’s about rewriting the story of architecture to reflect the true diversity of its creators.

This book introduces architectural history tives. This shift is not records; it’s a transformative we perceive and value

The evolution of documenting architectural work, from traditional media to modern digital platforms, signifies a crucial shift in the visibility of architects. Initially, the documentation of architectural achievements was largely restricted to traditional media forms like print publications and exhibitions, often accessible only to a select few. This limited exposure perpetuated a narrow view of architectural history, predominantly showcasing the works of a specific demographic. With the advent of digital platforms, the landscape of architectural documentation underwent a radical change. These new mediums democratized access to architectural discourse, enabling a more diverse range of voices and works to be showcased.

This shift has been instrumental in challenging the historical erasure of underrepresented architects, fostering a more inclusive and equitable field. The digital era has brought forth a proliferation of online archives, virtual exhibitions, and social media platforms, significantly broadening the reach and impact of architects’ work. This comprehensive approach to documentation not only captures the richness and diversity of contemporary architectural practice but also plays a pivotal role in rewriting the narrative of architectural history. It ensures that the contributions of all architects, irrespective of their background, are recognized, preserved, and celebrated, marking a significant move towards a more inclusive and representative architectural future.

introduces the vital concept of liberating

history

from its traditionally biased narranot just about correcting historical transformative act that redefines how

value

architectural contributions.

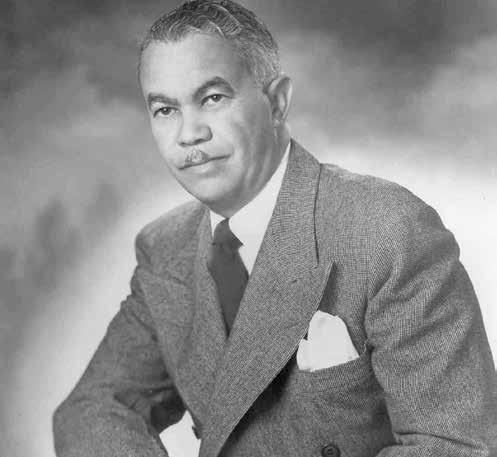

The creation of GREATNESS: Diverse Designers of Architecture is a journey of revelation and resolve, inspired by influential figures like Jack Travis and Melvin Mitchell. This book, in its essence, is a response to a profound realization: a web search for “great architect” overwhelmingly yields white men, a stark reflection of the historical bias in the field. This disparity was highlighted during my visit to Google’s New York headquarters in 2019, where it was revealed that the lack of content referring to women and BIPOC architects as “great” contributes to their invisibility in search results. This book aims to break this cycle of erasure, challenging the dominant narrative by showcasing the outstanding contributions of diverse architects.

The title GREATNESS is a deliberate choice, not just as a nod to the “Great Diverse Designers Library,” but in bold defiance against the skewed perceptions in architectural history. This section narrates the challenges and victories in assembling a book that not only highlights the excellence of underrepresented architects but also seeks to redefine what greatness means in the architectural world, contributing to a more inclusive and equitable history of the profession.

This book, in its essence, is a response to a profound realization: a web search for “great architect” overwhelmingly yields white men, a stark reflection of the historical bias in the field.

This book reaffirms the central themes discussed throughout, centering on the transformative potential of revising architectural history to be more inclusive. It emphasizes the crucial role of acknowledging and celebrating the diverse voices in architecture, a step essential for the evolution of the field. The book underscores the impact of this transformation, not only in rectifying historical oversights but also in enriching the architectural discourse and practice with a broad spectrum of perspectives and experiences. This comprehensive and inclusive approach to documenting architectural history is more than a corrective measure; it’s an endeavor to ensure the profession reflects the diverse society it serves.

The conclusion is a call to action for the architectural community and society at large, to recognize the value and necessity of diversity in shaping environments that are truly representative and inclusive. It encourages a continuous effort to celebrate diversity in architecture, fostering a profession and a built environment that embraces and showcases the richness of human creativity and experience.

Designer Location: New York

Featured Project: Weeksville Heritage Center

Project Location: Brooklyn, NY

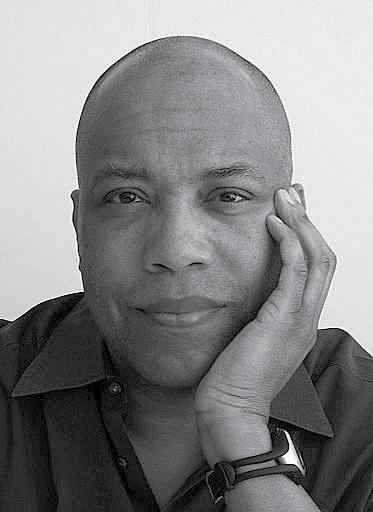

Everardo Jefferson is Co-founding Principal of Caples Jefferson Architects. His most recent book with Sara Caples is Many Voices: Architecture for Social Equity. Everardo has worked on socialequity projects for over 30 years. Everardo’s community service has included serving on the boards of social justice and educational institutions. He is currently a Commissioner of the New York City Landmark Preservation Commission. Everardo also teaches as a Davenport Professor at Yale University.

The Weeksville Heritage Center in Brooklyn’s Crown Heights is not just a building but a portal to a pivotal era in African American history. This sustainable two-story structure, encompassing 23,000 square feet, is a contemporary homage to Weeksville, a 19th-century settlement that was a beacon of freedom and prosperity for African Americans. Founded in 1838 after New York State abolished slavery, Weeksville flourished as a safe haven during the New York Draft Riots and as a center for the abolitionist movement. By the mid-1800s, it became the second-largest community of free Blacks in the U.S., with over 500 families.

The Center’s modern design, featuring exhibition spaces, classrooms, a library, and performance areas, subtly incorporates West African themes in its wood and frit-glass designs, reinforcing the site’s rich heritage. Architecturally, it forms an L-shaped composition, creating a dialogue between the present and the past. This layout not only connects physically to the four remaining 19th-century cottages, preserved from demolition in the 1970s, but also symbolically bridges eras, encapsulating the journey of the African American community. The facility, completed after the restoration of these cottages, is both an educational resource and a cultural landmark, dedicated to documenting, preserving, and interpreting the history of Weeksville. Its contemporary design, juxtaposed with the historical cottages, offers an immersive experience, inviting visitors to engage with the settlement’s past while celebrating its enduring legacy.

The Weeksville Heritage Center stands as a profound embodiment of cultural typology in architecture, bridging historical narratives and contemporary design to foster a deeper understanding and appreciation of African American heritage and community resilience.

Role on Project: Principal

○Everardo Jefferson began his professional journey as an industrial designer, initially immersed in the intricacies of objects. However, as time progressed, a noticeable shift occurred, and he discovered a heightened interest in the broader environmental context rather than the individual object itself. Reflecting on this evolution, he recalls a friend’s remark that “architecture is just packaging people instead of eggs.” Everardo recognized it was much more than this, and there was depth and significance beyond mere containment.

○In light of this realization, Everardo, originally trained as an industrial designer, found himself drawn to the ambition of crafting more expansive environments tailored for people. This transition marked a conscious decision to contribute to the creation of larger and more holistic spaces, reflecting his evolving passion for the interplay between design and the human experience.

Everardo Jefferson takes pride in all his projects, and this pride is rooted in the collaborative efforts that each undertaking entails. Each project, with its distinct team, has been a unique collaboration that brought out the best in everyone involved at that particular moment in time. The tangible manifestation of these collective efforts, reflected in their built work, stands as a testament to the collaborative excellence achieved in each project.

Designer Location: New York

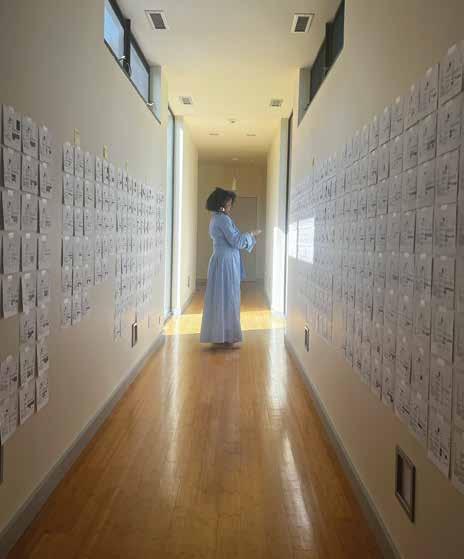

Shantell Martin’s Church and May Room, set on Governors Island in New York, represents an artistic revival of the former military chapel, Our Lady Star of the Sea.

Constructed in 1942 and unused since 1996, this chapel has been reimagined through Martin’s distinctive black-andwhite drawings, creating a reflective and immersive space. The artwork on the exterior, inspired by the island’s dynamic history, invites visitors to engage with a visual narrative that intertwines with the chapel’s architectural form, offering an exploration of history and art.

Inside, the transformation continues with a labyrinthine art installation that covers floors and walls, forming a space for quiet introspection and shared discourse. The installation includes uniquely designed, letter-shaped furniture, enabling visitors to interact physically with the art, enhancing their experience of the space. This interior redesign not only breathes new life into a long-closed building but also reinvents it as a modern cultural hub.

Part of the Trust for Governors Island’s 2019 Public Art Commission, The May Room signifies the reopening of this historical chapel to the public, reestablishing it as a place of meditation, community gathering, and cultural exploration. Hosting diverse public programs, including poetry readings by notable organizations, the project revives the chapel’s original communal spirit while introducing contemporary art and design. Through this blend of historical architecture and modern art, The May Room emerges as a beacon of cultural engagement, redefining the space as an artistic, historical, and community landmark.

Project

Role on Project: Artist, Designer Production

Shantell Martin’s Church and May Room exemplifies the integration of cultural symbolism and community participation in architectural design, fostering a space where historical narratives are preserved and reimagined for contemporary cultural engagement and reflection.

Shantell Martin, when asked about her introduction to architecture and interest in the built environment, simply refers to her upbringing in Thamesmead, South East London, suggesting that her early experiences there naturally fueled her curiosity and passion for the field.

For Shantell Martin, one of her proudest career achievements lies in the work she did with the New York City Ballet. This project stands out as a tremendous feat of collaboration between her and the Ballet. The impact she witnessed from the created work was undeniable, and the experience was inspiring. Shantell takes great pride in the transformative power of this collaboration and the positive influence it had on both the artistic process and the audience.

Shantell Martin is a visual artist best known for her large-scale, blackand-white drawings. She performs many of her drawings for a live audience. Born in Thamesmead, London, Martin lives and works in New York. Along with exhibitions and commissions for museums and galleries, Martin frequently works on international commercial projects, both private and public.

Designer Location: Wisconsin

Featured Project: Trixster

Chris Cornelius is a citizen of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin. He is the founding principal of studio:indigenous, a design and consulting practice serving indigenous clients. Chris is an Associate Professor of Architecture at the University of WisconsinMilwaukee. He has received numerous awards and honors including an Artist in Residence Fellowship from the National Museum of the American Indian. Chris’s work has been exhibited widely, including at the 2018 Venice Architecture Biennale.

Project Location: Sheboygan, WI

Role on Project: Designer Fabricator

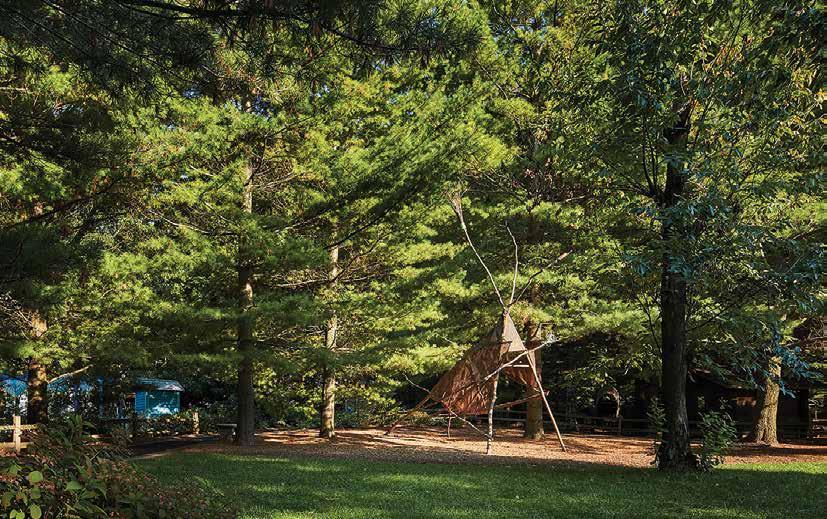

“Trickster” (itsnotatipi) by Chris T. Cornelius, an architect of the Oneida Nation of Wisconsin and founder of studio:indigenous, is a profound installation located at Bookworm Gardens in Sheboygan, Wisconsin. Crafted from wood harvested on site and patinated copper mesh, this installation transcends mere artistic expression, embedding deep indigenous narratives into its form. The trickster, pivotal in indigenous storytelling and often represented in animal form, challenges humancentered thinking and invites us to reconceptualize our understanding of the world.

Cornelius, also an educator who teaches “De-Colonizing Indigenous Housing” at Yale, uses his architectural expertise to intertwine indigenous sovereignty and narrative with physical spaces. His work, spanning Canada and the United States, defies traditional borders and promotes a holistic understanding of indigenous architecture. The Trickster, along with other installations like Wiikiaami in Columbus, Indiana, showcases Cornelius’s unique approach to design, where every structure is rooted in a story. These installations not only honor indigenous heritage but also demonstrate a deep respect for the natural landscape, challenging conventional architectural practices and increasing representation for native peoples in the field.

Trickster by Chris T. Cornelius embodies the essence of cultural typology in architecture, serving as a poignant example of how indigenous narratives and storytelling can be intricately woven into spatial design, offering a transformative perspective on the relationship between culture, architecture, and the natural environment.

Chris Cornelius recounts that his interest began at the age of fourteen. Motivated by a desire to improve the reservation he grew up on, he discovered a passion for architecture and its potential to positively impact these spaces. Chris Cornelius recounts his proudest professional achievement was his participation in the Venice Biennale.