ORO Editions

Publishers of Architecture, Art, and Design

Gordon Goff: Publisher

www.oroeditions.com

info@oroeditions.com

Published by ORO Editions

Copyright © Studio Hillier and ORO Editions 2023

Text and Images © Studio Hillier 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including electronic, mechanical, photocopying of microfilming, recording, or otherwise (except that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press) without written permission from the publisher.

You must not circulate this book in any other binding or cover and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Graphic Design: Pablo Mandel / CircularStudio

ORO Managing Editor: Kirby Anderson

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 First Edition

Library of Congress data available upon request. World Rights: Available

ISBN: 978-1-957183-50-3

Color Separations and Printing: ORO Editions, Inc.

Printed in China.

International Distribution: www.oroeditions.com/distribution

ORO Editions makes a continuous effort to minimize the overall carbon footprint of its publications. As part of this goal, ORO Editions, in association with Global ReLeaf, arranges to plant trees to replace those used in the manufacturing of the paper produced for its books. Global ReLeaf is an international campaign run by American Forests, one of the world’s oldest nonprofit conservation organizations. Global ReLeaf is American Forests’ education and action program that helps individuals, organizations, agencies, and corporations improve the local and global environment by planting and caring for trees.

Hillier

Selected Works

STAN ALLEN

FOREWORD BY

THIS MONOGRAPH IS DEDICATED TO THE MEMORY OF BARBARA ANN HILLIER, AIA JUNE 20, 1951 – NOVEMBER 21, 2022

Table of Contents Foreword 6 Introduction 10 Projects 12 Autretemps 15 LVMH Tower 23 GlaxoSmithKline Global Headquarters 27 Howard University Stokes Library 35 Solebury Abbe Science Center 41 Cornell University Laboratory of Ornithology 49 The Waxwood 57 House at Leeside Farm 63 Peddie School Annenberg Science Center 69 Duke NUS Singapore 77 Princeton Public Library 83 Synygy World Headquarters 89 New Jersey Medical School Cancer Center 97 Duke University French Science Center 103 Central Park North 111 Timeline 116 Quarry Street Two-Plex 125 Becton Dickinson Campus Center 131 Goucher College Athenaeum 141 Irving Convention Center 151 Urban Trifecta 159 Penn Medicine Princeton Medical Center 167 Solebury Two-Plex 173 Copperwood 179 East River Science Park 185 Iona University Residence Hall 191 The Lawrenceville School Kirby Math and Science Center 197 Steeple View 205 Institute for Advanced Study Faculty Housing 213 River Road Residence 219 Nantucket Residence 227 Project Credits 236 Acknowledgments 242 About Studio Hillier 242 About the Hilliers 243 Photography Credits 246 Contributors 248

Foreword

BY STAN ALLEN

HILLIER: ARCHITECTURE AS VOCATION

Delicately poised between the art of design and the science of building, architecture is a paradoxical field of endeavor. The architect’s knowledge is, of necessity, broad rather than deep. An architect proposes creative solutions to complex problems, leading some to the mistaken notion that the architect is a kind of artist. Architects work with technology, from the elemental stacking of bricks to sophisticated computational methods, leading others to the (equally mistaken) idea that architecture is a technical discipline. It is, in fact, the ability to work simultaneously in the artistic and the technical realms that distinguishes the work of the architect. Architecture is a synthetic discipline above all.

Architecture is a visual medium, but architects work with words too, both spoken and written. Buildings and cities shape the landscape of civic life and the architect needs to communicate with an engaged public: not only clients, but local communities, stakeholders, and regulatory agencies. Architecture, unlike painting or sculpture, is fixed in place and persists over time; an architect needs a keen sense of place—that indefinable intuition of genius loci . And an architect needs a head for business, otherwise it’s all fantasy, private, and never realized.

To be an architect, then, is more than a career choice. More, even, than a passion, as passions can be fleeting, and architecture is a slow and demanding discipline. To be an architect is something closer, I would argue, to a vocation: a kind of calling, that extends beyond the long working hours to encompass an entire outlook on the world. Dictionary definitions of vocation emphasize this idea of a summons to

a particular course of action. The Latin word-root is the verb vocare, to call, and it is a word often used in the context of a divine call to the religious life. As such, a vocation implies both that the work is worthwhile, and that it requires great dedication—as is the case with the practice of architecture.

The idea of suitability is often evoked—that is to say, that the abilities of the person are perfectly fitted to their chosen vocation. I can think of no better description of Bob and Barbara Hillier, and by extension the work of Hillier, than to refer to this idea of architecture as vocation. A vocation, as personal as it is, also implies a wider purpose; architecture is, above all, a social enterprise. To design a building or to plan a fragment of a city is to intervene in the world in hopes of leaving it a better place. Something akin to the Hippocratic oath of “First, do no harm.”

Buildings are realized through a complex collaborative process involving clients, designers, consultants, builders, and a community of users. Any partnership rests on dialogue, and at Hillier, that dialogue extends to collaborators and clients. Finally, architecture has a unique ability among the plastic arts to actually improve lives: to give back to society. If we look at the building types that have been at the core of Hillier’s practice for more than fifty years we find libraries, laboratories and schools; places for work, healthcare, public institutions, and places to live. The social change that architecture implements is incremental, not revolutionary. Each of these building types has the capacity to concretely improve people’s lives, in modest yet significant ways.

6

These two core ideas—architecture’s capacity to better the lives of those who come in contact with it, and the concept of architecture as a vocation—are exemplified by the firm’s longstanding commitment to education. I am thinking here not only of Bob’s activities as a speaker and an influential teacher at Princeton, but a history of innovative designs for educational facilities dating back to 1974, and the completion of the American International School in Vienna—the first of 12 international secondary schools designed by Hillier. Schools and educational facilities have been at the center of the practice ever since, most recently with the Kirby Math and Science Center at The Lawrenceville School, a building that extended an earlier Hillier design. For an architect to imagine and to construct places where young people are taught—where ideas are discovered and minds are formed—is to give back to society in a meaningful way. Schools are the places where thoughtful and informed citizens are cultivated, our best hope for the preservation of democracy.

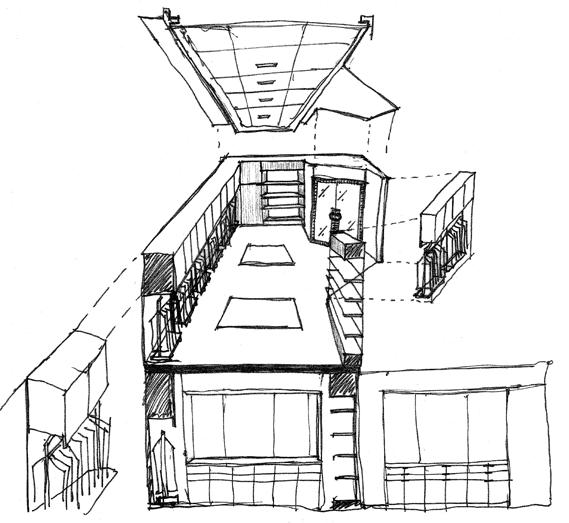

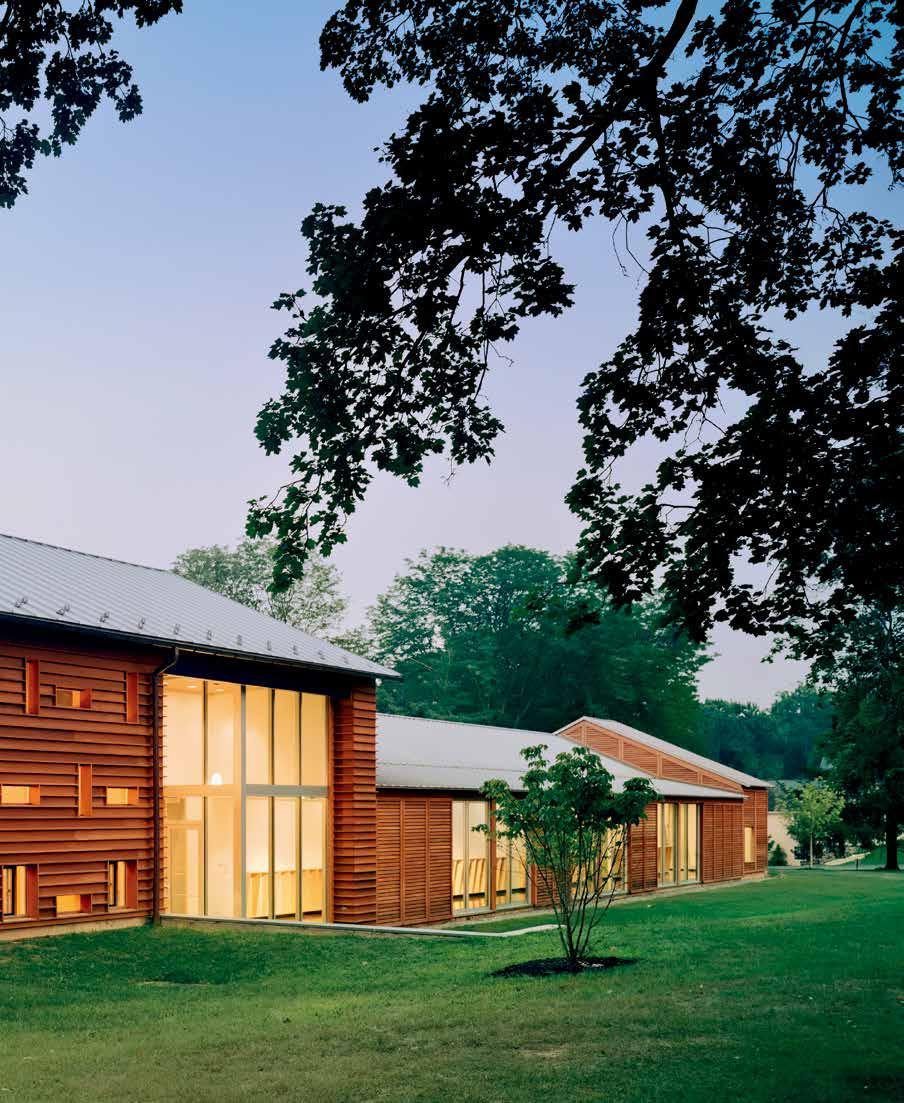

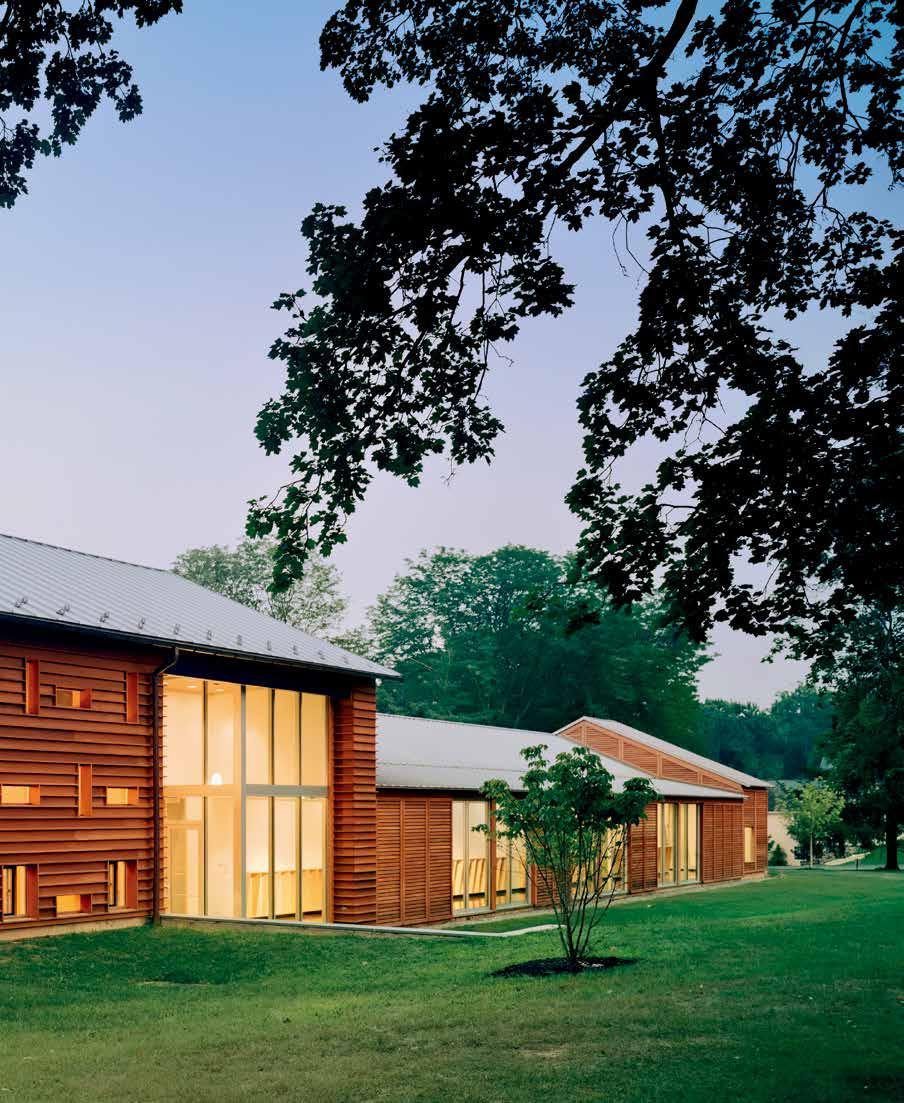

Among the firm’s many buildings for secondary schools, the Abbe Science Center at the Solebury School in Bucks County, Pennsylvania, is, at first glance, an unassuming structure. This pitched-roof, wood-clad structure pays homage to its rural context. It recalls a barn or a corn-crib. But that first impression is deceptive. This is an intricate building that accommodates a complex program of classrooms, common areas and laboratories. It responds to its built context as much as to the natural landscape. The building’s “L” shape creates defined exterior spaces and multiple points of entry. The building offers distinctive prospects to the viewer, enlivening the experience of

moving around and through it. These surfaces are in turn articulated with variations of wood cladding, the detailing of each one recalling, while never mimicking, the traditional clapboard of the local vernacular. At the entry nearest the campus the structure opens up to create a shaded porch, and the siding becomes open slats, creating subtle transparencies and shadow patterns. The building adjusts to the gentle slope of the site, taking advantage of the level change to create a double-height entry space—a thoroughly modern and unexpected intervention in the deceptively modest vernacular idiom.

Laboratory buildings are also a place of learning and discovery, and they have played an important role in Hillier’s practice. Bob Hillier is well-positioned to understand the culture of the research laboratory: his father James Hillier was a scientist who worked for many years at the RCA research laboratories in Princeton, and (among many other accomplishments), is credited for his role in developing the scanning electron microscope.

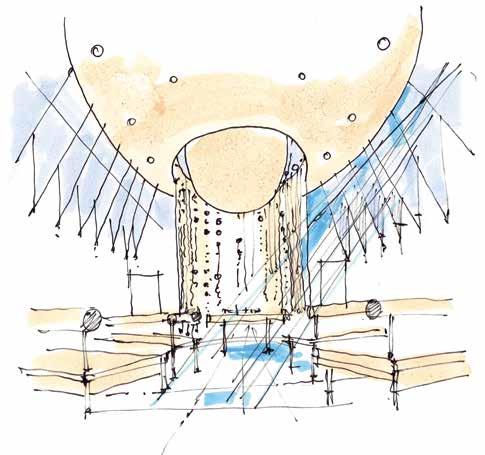

The Cornell Ornithology Center is a more elaborate building than the Abbe Science Center, but this reflects the complexity of the program and the site, rather than any desire for formal expression. The footprint of the building was largely dictated by wetland mapping and the need to integrate the building into its natural landscape. The site plan includes pathways, extensive planting, gardens, and terraces. It too offers multiple prospects, but in this case, it is as much the view from inside to out, as the exterior appearance of the building. Ornithology is less a laboratory-based experimental field than it is a

7

science of observation and data gathering: the Cornell lab houses the world’s largest library of recorded bird calls, for example. Hillier have designed a building that highlights the many and varied prospects of the natural landscape surrounding the lab. It is a project that highlights the firm’s sensitivity both to place and to the intricacies of functional programing.

Any practice is shaped by its time and place, and Hillier is no exception. However, what is remarkable in this case is the consistency of the work that has been developed over more than fifty years. During the 1970s and ’80s, when modernist ideas of function and materials were questioned, Hillier’s commitment to these modernist ideals never wavered. Architecture could never be an empty rhetorical practice for Hillier, and the firm was never seduced by postmodern eclecticism.

I think there are several reasons for this. The first is the influence of Jean Labatut, Bob’s teacher at Princeton, and later his first employer. Labatut, described by Le Corbusier on the occasion of his 1935 visit to Princeton as “an intelligent and liberal-spirited Frenchman,” 1 was a Beaux-Arts trained architect who taught at Princeton from the late 1920’s through the 1960s. He has been described as the person most responsible for the high standing of Princeton’s School of Architecture at that time. Long before post-modernism, Labatut encouraged a synthesis of modernist ideals with a respect for history and place; it is no coincidence that Robert Venturi also studied at Princeton with Labatut. Bob Hillier, in other words, was perhaps not seduced by post-modernism in those years because he

understood precisely where it was coming from, and had a more robust idea of history and place to fall back on.

The other, perhaps less obvious but equally important reason is the significance of the firm’s base in the town of Princeton. At times Hillier has had branch offices in Philadelphia, New York, Tampa, and even Shanghai, but Princeton has always been the base. Beyond the University, Princeton hosts many scientific and research laboratories, primarily in the fields of pharmaceuticals and electronics (which of course is what brought the Hillier family to Princeton in the first place). Working slightly outside the metropolitan mainstream, in a milieux dedicated to education and scientific research has, I believe, had a lasting impact on the culture of the firm.

It would be impossible in a short introduction such as this to do justice to the full catalog of Hillier’s production; one example will have to stand in for the range and diversity of the firm’s production. The co-generation plant at JFK is a building I long admired without knowing who the architect was. And this is fitting. In an era of so-called star architects, the co-generation plant is a building that caught my eye and enlivened an otherwise unpleasant trip to the airport, even though, at the time, its architect was unknown to me. It calls attention to the working infrastructure of the airport more than to a stylistic signature.

To give an anonymous piece of infrastructure a distinctive and elegant presence—a presence that necessarily needs to be understood at distance and at the speed of a passing car—is a statement of faith in architecture’s capacity to

8 Foreword

render the modern civic landscape intelligible. The materials and detailing of the co-generation plant foreground the functional nature of the structure, yet the form recalls that of nearby terminals: machines and people are each housed with equal dignity, and the banal landscape of the airport is enhanced for the weary traveler. The JFK co-generation plant is one of several that the firm has designed and these structures quietly, and without pretense, call attention to Hillier’s longstanding commitment to energy use and sustainability.

Looking back on these fifty-plus years dedicated to education, research and scientific discovery, it is only fitting that in 2019 the New Jersey Institute of Technology renamed its architecture and design school the J. Robert and Barbara A. Hillier College of Architecture and Design. With this honor, the firm’s commitment to education—both the education of the next generation of architects but also education as a larger commitment to the betterment of society—has been recognized and reaffirmed.

9

1 Le Corbusier, When the Cathedrals Were White, (New York, McGraw Hill, 1964; French original 1938), p. 140.

BY J. ROBERT HILLIER

Welcome!

It is a pleasure to welcome you to the second monograph published by Hillier in our 57 years of practice. You will find within these pages, the projects that we have completed within the last 25 years and also a more retrospective historic section of work going back to our beginnings in the 1960s. We have also included a year-by-year timeline of the growth of the firm marked by major projects and changes in the firm’s logo which you will find interesting and perhaps amusing.

I believe that architecture is one of the most exciting professions in which to spend a lifetime and I am so grateful that I found it as a career. It is a profession that is project oriented, and each project is different in that it has a different client, a different program, and a different site in a different context. Each of these elements has to be explored, defined, and listened to—yes, even the site has a story to tell.

My belief is that the best designs come out of a thorough programming process that defines the problem at hand. Just as one programs a computer to do a certain job, one needs to program a building to do its job.

An important part of the program is understanding the “forces” at work on the project. I often refer to them as the “hidden clients.” These are forces beyond the usual gravity, weather, and sustainability which confront every building, but are more subtle. They can include culture, history, context, economics, market, codes, and, in some cases, even politics.

As a firm, we believe the architect, working with the client, needs to understand the scope, strength, and priority of each of these forces. We also believe it is the responsibility of the architect to bring all of those forces into balance for a successful final project. As a result you are serving the client, serving society, and serving nature.

This philosophy of design results in every building being unto itself. We cannot have a singular design language because we do not work with a single type of client nor within a single geographical context. In our firm we try to create an environment where each designer and their team can find their own way, unencumbered by some super language or doctrine with which they have to abide. The only doctrine we prescribe is quality and excellence.

Many talented designers, architects, engineers, contractors, and craftspeople contributed to the works in this book. Viewing them retrospectively, I am astonished by the quantity and the quality of the work we have completed over the years, of which this is only a small sample. The title of the book, Selected Works, is intended both, as a reminder of the immense effort that goes into realizing a successful project, and as a tribute to those responsible.

I do want to acknowledge and thank the team that created this book. They are Julian Edgren, Caryn Farnum, Julia Stanat, Kaitlyn Zook, and their leader in this effort, Alexander Kim.

I hope that you enjoy these pages and the work therein.

Introduction

10

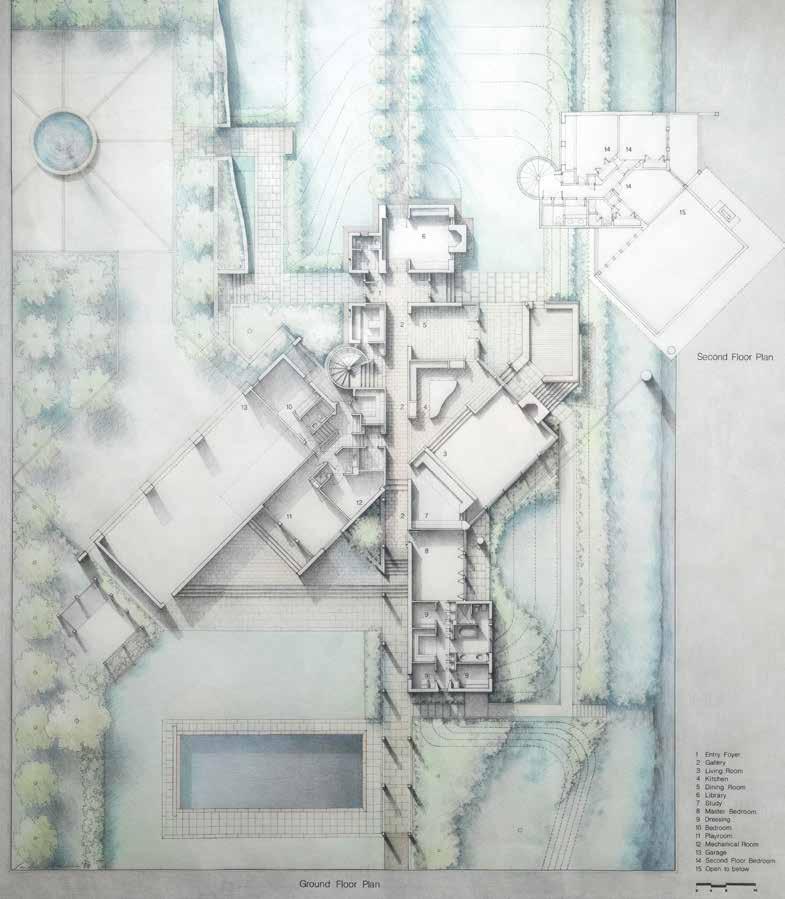

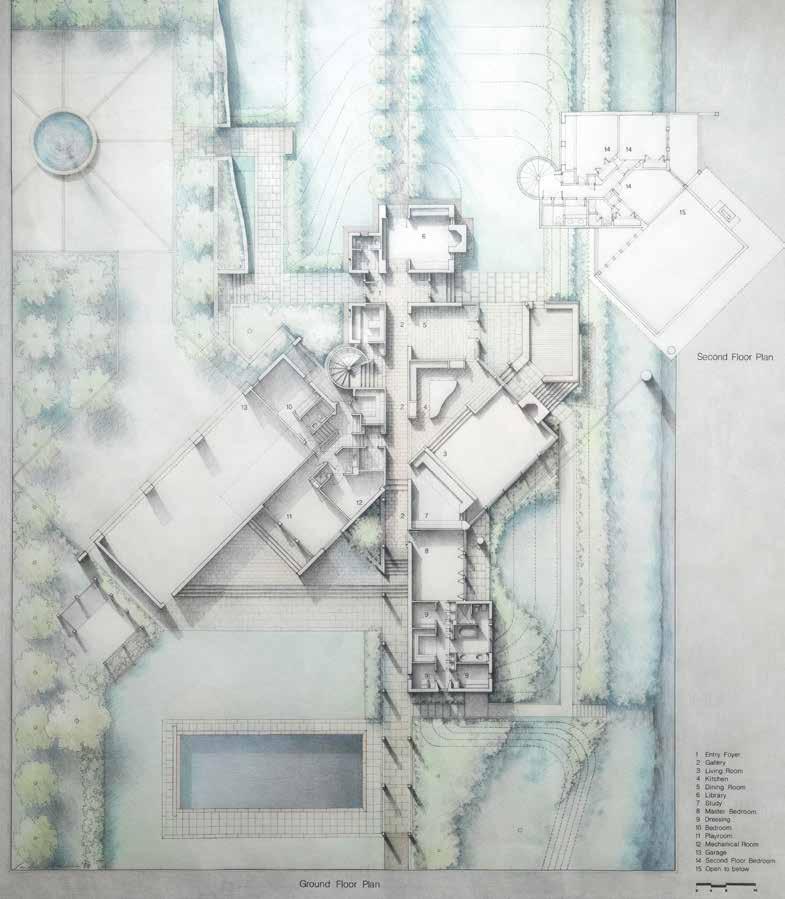

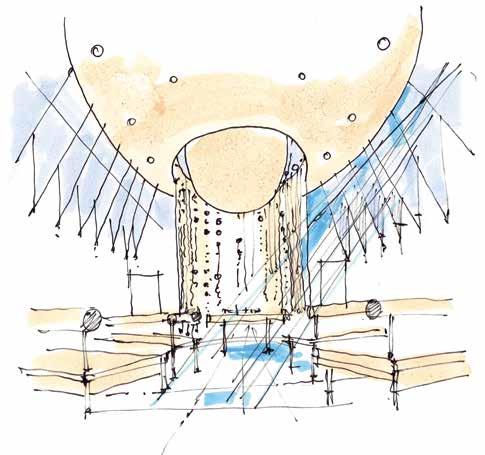

Opposite: Autretemps rendered plan by Sanda Iliescu

11

22

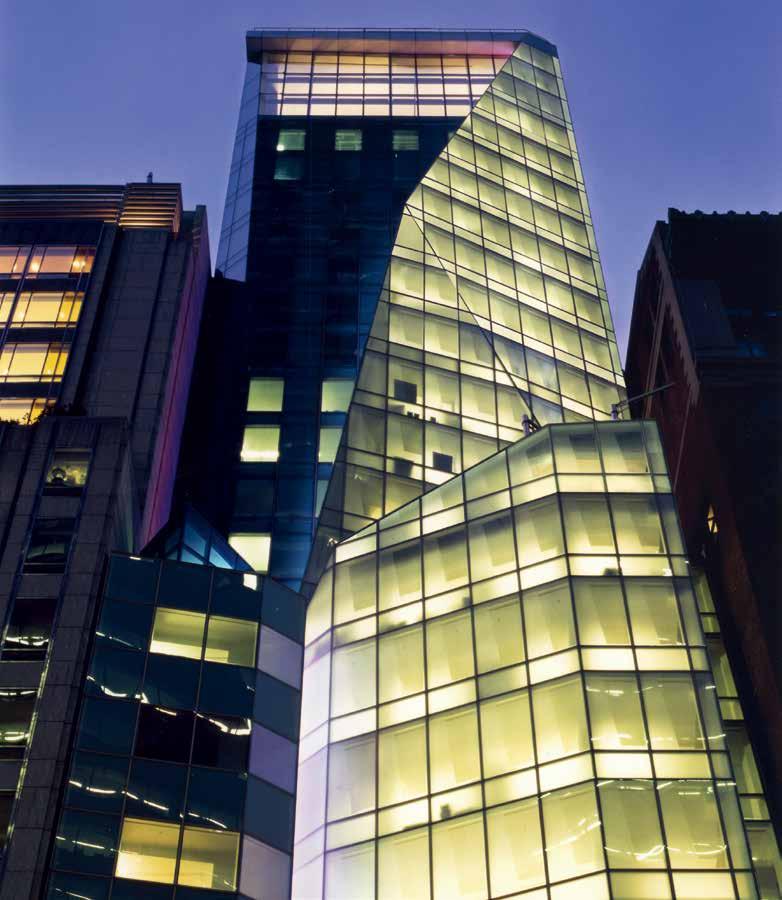

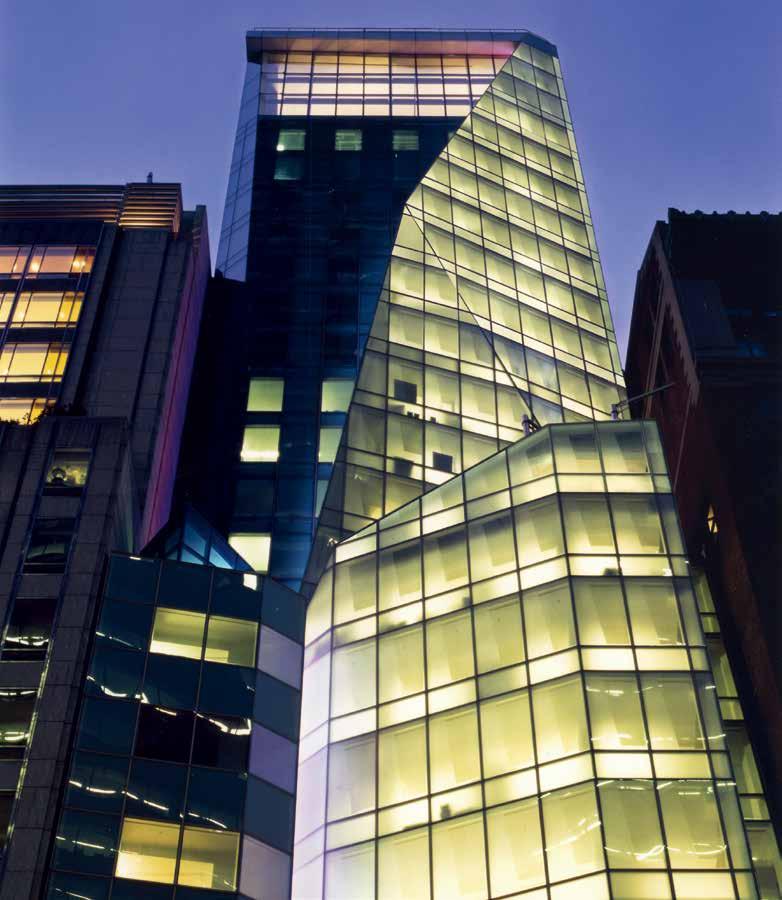

LVMH Tower

Hillier collaborated with Christian de Portzamparc, a Pritzker Prize-winning architect, on this twentyfour-story skyscraper in Midtown Manhattan. Mr. Portzamparc provided the building design, and Hillier served as the coordinating architect, providing design development, production documentation, and construction administration services, as well as interior architecture and design. A ground-level store for Christian Dior was designed by Peter Marino. The white-glass-mirrored tower, with a striking oblique line, is as dramatic as the fashion companies housed within its walls. The innovative structure incorporates intelligent building technologies, including fully integrated data and telecommunications systems.

NEW YORK, NY 106,000 SF

23

32 GlaxoSmithKline Global Headquarters

33

166

Penn Medicine Princeton Medical Center

PLAINSBORO, NJ

611,000 SF

Penn Medicine Princeton Medical Center, formerly known as the University Medical Center of Princeton at Plainsboro (UMCPP), is a 355-bed, nonprofit, acute-care hospital. Though often perceived as a community hospital, its services extend regionally. Hillier Architecture provided feasibility studies for UMCPP’s relocation onto a new green-field site.

167

Evidence-based design, which links the quality of the hospital environment to patient healing and recovery rates, is at the heart of the design for the new hospital. From the abundant, natural light to spacious and flexible operating rooms to all-private patient rooms designed to reduce falls and minimize the risk of infection, every aspect of the hospital’s design conveys a healing and welcoming atmosphere for patients, their families, and hospital staff.

The hospital’s sustainable design includes many energy and conservation innovations to make it one of the most

environmentally advanced hospitals in the nation. To maximize the use of natural light while controlling solar heat gain, the building is configured is on an east-west orientation relative to the site. On the façade, a sunlightregulating exterior screen significantly reduces the amount of energy required for heating and cooling.

Additional features include a chilled water thermal storage system and environmental controls for lighting and temperature; the site’s landscaping also features indigenous plants.

170 Penn Medicine Princeton Medical Center

171

About the Hilliers

J. ROBERT HILLIER is an American architect known for his speaking and teaching about architecture as well as for his prolific range of completed works in thirty-four states and twenty-two countries. He built his firm, Hillier Architecture (previously The Hillier Group), into one of the most successful architecture firms in the country before merging with an international firm to become one of the world’s largest. In 2010, he and his wife established Studio Hillier, a new firm focusing on community need, neighborhood enhancement, and special opportunities for architectural interventions.

Bob, as he is known to friends and colleagues, was born in Toronto, Ontario, but basically grew up in Princeton, NJ, one of two sons of high-achieving parents. His father was James Hillier, a leading scientist for RCA who is credited with designing and building the first successful scanning electron microscope; his mother, Florence Hillier, owned three flower shops around town. He graduated from Princeton Day School, the Lawrenceville School, and Princeton University, where he received both a Bachelor of Arts and a Master of Architecture degree.

From an early age, Bob’s entrepreneurial instinct was apparent; at age thirteen he was running a lucrative business selling tropical fish to Princeton students through his mother’s flower shops to pay for half the cost of attending Lawrenceville, an agreement he made with his father. During his undergraduate years at Princeton, he was a campus politician and a class officer and designed decorations for many of the school’s proms. His advisor, recognizing the evident design talent, suggested architecture as a course of study.

After receiving his architecture degree, he worked briefly for a local architecture firm before opening his own office on Nassau Street in 1966. His first job was replacing a bathroom vanity for a wealthy Princeton man, but that soon turned into a commission to renovate the client’s corporate office building in Chicago. From there, the firm expanded rapidly, delivering numerous award-winning projects for clients throughout New Jersey and the Northeast.

By 1980, the firm had hired its one hundredth employee; by 1987, The Hillier Group was the country’s seventh largest architectural firm with a staff of 235. A full-service regional office was opened in Philadelphia in 1988 under the leadership of Design and Managing Principal Barbara Hillier, Bob’s wife. By the 2000s, Hillier Architecture was an industry leader recognized as one of the best-managed firms by Architectural Record and had offices in New York, Princeton, Philadelphia, Washington, DC, Shanghai, and Dubai. Its portfolio includes award-winning headquarters for many of the largest companies in Europe and the United States, works for major universities, state-of-the-art research laboratories for industry leaders as well as mixeduse hotel, residential and office complexes in the United States and Asia.

Rather than adopting a particular style or even basic doctrines of design within his firm, Hillier promotes a working environment where each designer is empowered to find their own way in pursuit of quality and excellence. To deliver the kind of design that each market sector looks for, Hillier Architecture was divided into thirteen practice groups, such as laboratories, historic preservation, higher

243

education, and interior design. Hillier culture is rooted in a philosophy of celebrating the extraordinary differences among people and places while responding to them with sensitivity and respect.

In addition to running a successful business, since 1992, Bob has been on the core faculty of Princeton University’s School of Architecture, where he teaches two graduate seminars about the business of architectural practice. In a school that emphasizes theory, the course is widely known as “Bob’s reality check.” He has served as chair of the Selection Committee for the dean of Princeton’s School of Architecture as well as on the AIA National Fellowship Jury, having been elevated to Fellowship in 1976.

At the New Jersey Institute of Technology, Bob’s influence and impact are especially visible. The original architecture school’s renovation was designed by Hillier in 1972, and the school’s own building was designed by Hillier in 1999. He has also been on NJIT’s Board of Overseers since 1993. In 2009 he was awarded the NJIT President’s Medal for Lifetime Achievement and in 2017 received an honorary doctor of humane letters. In May 2019, the architecture school was renamed the J. Robert and Barbara A. Hillier College of Architecture and Design following a transformative gift from the Hilliers.

In 2007, J. Robert Hillier was awarded the AIA New Jersey Michael Graves Lifetime Achievement Medal, given “in recognition of a significant body of work of lasting influence on the theory and practice of architecture.”

BARBARA A. HILLIER was born in Philadelphia, PA to Shirley and Coleman Feinberg. Early on in her education, Barbara displayed an aptitude for creative artistry, which her high school guidance counselor suggested could make her a successful hair stylist. But Barbara was unpersuaded by her counselor’s prediction for her future. Instead, she attained a Psychology degree from Temple University followed by a BFA in Interior/Graphic Design from Arcadia University.

In 1976, armed with two degrees but no experience in architectural design, Barbara began her career as an interior designer at J. Robert Hillier, Architect, a small, Princetonbased design firm. She opened the firm’s regional office in Philadelphia in 1988 and led a studio grounded in strong architecture, planning, and interior design work. She worked for many years without a professional degree before becoming a licensed architect in Pennsylvania in 1993 having completed the required 13 years of specific architectural work experience.

After helping build the firm to national and international prominence and becoming a mother, Barbara returned to school in 2011, and met her lifetime dream of completing her professional education with an M. Arch at Princeton University.

Over the past four decades, Barbara’s architectural projects have been celebrated for creatively synthesizing innovation and performance. Her human-centric approach empowers clients and stakeholders while driving her design toward unexpected solutions. She challenges her

244 About the Hilliers

design teams to ask difficult questions and challenge the status quo.

For example, Barbara’s Irving Convention Center is a vertically stacked landscape of meeting rooms that defies typological conventions. At the Becton Dickinson Campus Center, a conventional building connecting two existing ones was reimagined as an insertion under a treasured central lawn to preserve it while still fulfilling a connective function between the marketing and research and development departments…over lunch. The Solebury School Abbe Science Center is a sustainable, technologically advanced facility that adroitly engages the historic context and materials of the region.

Barbara begins with people. Then, she thoughtfully layers context, history, and the particulars of place into her solution. Her sensitive approach to design creates spaces that are responsive, provocative, and inspirational. Her projects have been published widely and influenced other architects who have followed in her footsteps. Her work has been recognized with numerous awards from AIA chapters including the coveted Pennsylvania AIA Silver Medal and The Chicago Athenaeum Award.

Given her own unconventional educational path to architecture, Barbara believes in an inclusive design education that engages students, professionals, and the public. She has lectured extensively and served on numerous academic and professional design juries, including as Chair of the 2001 AIA National Honor Awards Jury for Interior Design. In Philadelphia in 2002, Barbara created and led

a series of ten public lectures in which notable architects such as Enrique Norten and Wes Jones participated. She has also served on the Boards of Trustees of Philadelphia University of the Arts and the Philadelphia Foundation for Architecture.

Eager to share her expertise and knowledge, Barbara has relentlessly mentored generations of architects and designers. In 1979, she created “Hillier Career Day.” Beginning with six high school students, it grew to include over a hundred students by 2000. This initiative raised local awareness of the profession and launched the architectural careers for many students including 17 participants who later became Hillier employees. Barbara also led the Hillier Intern Program, which was recognized at the 2000 AIA National Convention and is responsible for leading many architects to successful careers in top firms.

In 2019, New Jersey Institute of Technology’s architecture school was renamed the J. Robert and Barbara A. Hillier College of Architecture and Design, celebrating the Hilliers’ commitment to providing more equitable access to design education. NJIT has been ranked #1 nationally by Forbes Magazine for Student Upward Mobility.

245

Photography Credits

AUTRETEMPS

Julian Edgren

LVMH TOWER

Paul Warchol Photography

GLAXOSMITHKLINE GLOBAL HEADQUARTERS

© Edmund Sumner

HOWARD UNIVERSITY STOKES LIBRARY

© Peter Mauss/Esto

SOLEBURY SCHOOL ABBE SCIENCE CENTER

© Albert Vecerka/Esto

CORNELL UNIVERSITY LABORATORY OF ORNITHOLOGY

© Brad Feinknopf/OTTO

THE WAXWOOD

Julian Edgren

HOUSE AT LEESIDE FARM

© Albert Vecerka/Esto

PEDDIE SCHOOL ANNENBERG SCIENCE CENTER

© Albert Vecerka/Esto

DUKE NUS SINGAPORE Infinitude

PRINCETON PUBLIC LIBRARY

Julian Edgren

SYNYGY WORLD HEADQUARTERS

© Jeffry Totaro / Jeffrey E. Tyron

NEW JERSEY MEDICAL SCHOOL CANCER CENTER

© Peter Brown Architectural Photography

DUKE UNIVERSITY FRENCH SCIENCE CENTER

© Robert Benson Photography

CENTRAL PARK NORTH

Jeffrey E. Tyron / Julian Edgren

QUARRY STREET TWO-PLEX

Thomas Kieren

BECTON DICKINSON CAMPUS CENTER

© Brad Feinknopf/OTTO

GOUCHER COLLEGE ATHENAEUM

Jeffrey E. Tyron

IRVING CONVENTION CENTER

Tex Jernigan/ARKO

PENN MEDICINE PRINCETON MEDICAL CENTER

Richard Titus Photographics

246

SOLEBURY TWO-PLEX

Jeffrey E. Tyron

URBAN TRIFECTA

Halkin/Mason Photography

COPPERWOOD

Tom Grimes Photography

EAST RIVER SCIENCE PARK

Julian Edgren

IONA UNIVERSITY RESIDENCE HALL

Halkin/Mason Photography

THE LAWRENCEVILLE SCHOOL KIRBY

MATH AND SCIENCE CENTER

Halkin/Mason Photography

STEEPLE VIEW

Don Pearse Photographers, Inc.

INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDY FACULTY HOUSING

Halkin/Mason Photography

RIVER ROAD RESIDENCE

Julian Edgren

NANTUCKET RESIDENCE

Julian Edgren

Every reasonable effort has been made to credit the ownership of copyright for images included in this monograph. Any errors that may have occurred are inadvertent.

247

Contributors

Stan Allen

Pablo Mandel

Stan Allen is an architect and George Dutton ’27 Professor of Architecture at Princeton University and former Dean of the School of Architecture. His practice, Stan Allen Architect, has realized buildings and urban projects in the United States, South America, and Asia. Responding to the contemporary city in creative ways, Allen has developed an extensive catalogue of innovative design strategies, in particular looking at field theory, landscape architecture, and ecology as models to revitalize design practice. Parallel to this large-scale work he has recently completed a number of private houses and artist’s studios on rural sites in the Hudson River Valley. His architectural work is published in Points + Lines: Diagrams and Projects for the City and his essays

in Practice: Architecture, Technique and Representation

The edited volume Landform Building: Architecture’s New Terrain was published by Lars Müller in 2011, and his most recent book is Situated Objects, published by Park Books in 2020.

Pablo is an Argentine-Canadian graphic designer. For more than two decades he has built a career designing books on architecture; working with renown architects, universities, musicians, and artists in the United States, Canada, Australia, Japan, Singapore, China, Italy, Germany, England, Spain, Chile, and Argentina. Born in Argentina in 1970, Pablo graduated from Buenos Aires University in 1995 with a degree in Graphic Design, emigrating to Canada shortly after. His book designs have been published internationally and have been the recipient of numerous awards, including the Canadian Society of Landscape Architects’ National Merit Award 2011 for Grounded, and for Moving Landscapes (2016); and the Bookbuilders West’s Certificate of Excellence (Image-driven trade books, 2009, 2010, 2011). In parallel to his graphic design activity, Pablo has been active for more than 20 years as a musician, member of the League of Crafty Guitarists and the Guitar Circles. Last but not least: Pablo is an artist, a husband, and a father.

248