Johann Wolfgang von Göthe

Foreword by

Jack Rasmussen

Afterword

by

Ori Z. Soltes

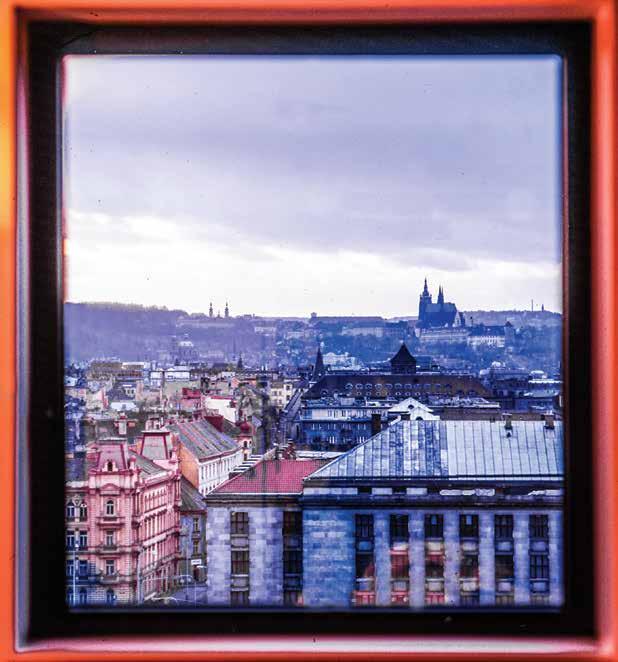

“Prague will never let you go...

This Little Mother has Claws” Kafka

Foreword 13

July 1944 - April 1945

A Child’s time in prague and a last-minute escape 14

Spring 1985

Two 40th Anniversaries 23

Summer 1988 near the end of Communist rule 61

Imagine John

The John Lennon Wall 131

Spring 1990 freedom Restored 149

New Year’s Eve 1991 The end of the Soviet Empire 213 AfterWord 233

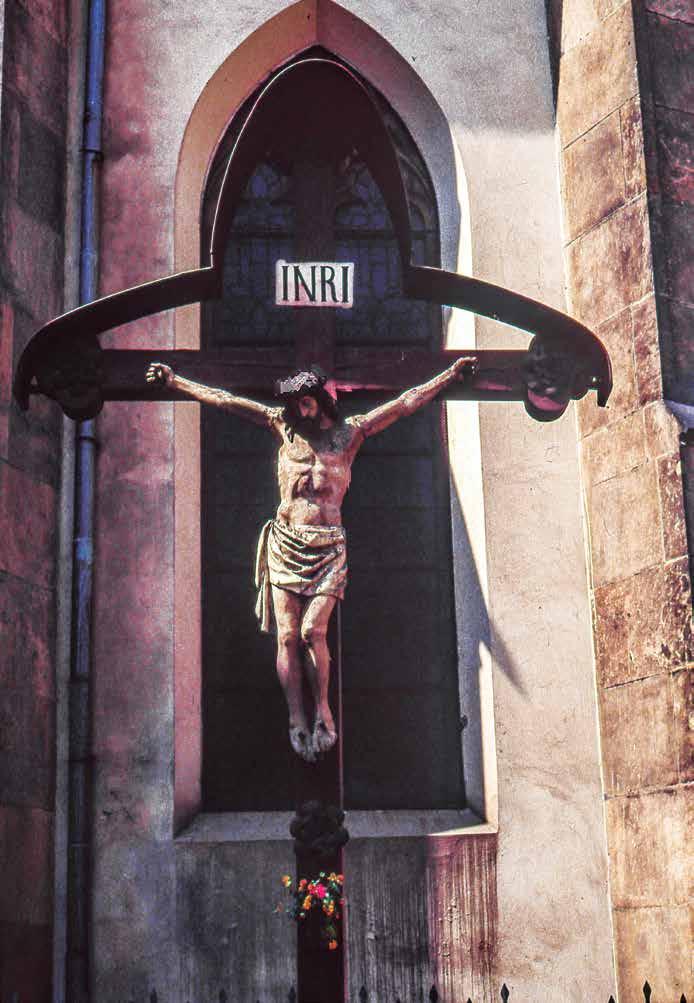

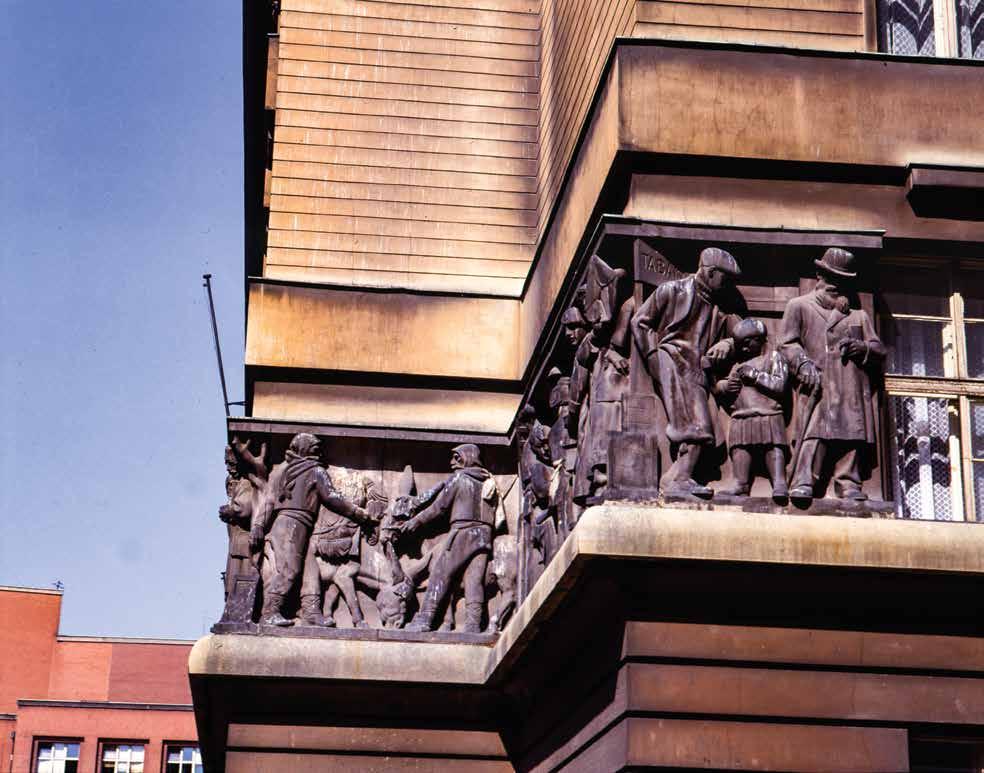

This beautiful collaboration by Bernis and Peter von zur Muehlen, Prague Revisited: From World War II to the Velvet Revolution, documents the artists’ personal journey through difficult and eventually triumphant times photographing in contested territory that is now the Czech Republic. Since opening its doors in 2005, the American University Museum has had parallel concerns with the importance of remembering and documenting that time and place. The museum has by now presented nine exhibitions featuring individual artists and groups originally from Prague or recently drawn there to showcase intelligent, well-made, and provocative objects and ideas originating in that city.

As the museum’s director and curator, I had a hand in presenting many exhibitions relevant to the years between 1944 and 1990, highlighted in the title of the von zur Muehlen’s collaboration. The period begins with Prague under Nazi rule. To name just a few, we exhibited the Dadaist collages of Jiří Kolář and the multi-media collaborative documentary of resistance, “Prague, City of Eugenic Minds,“ both made or conceived during WWII. Others of our Czech exhibitions marked the middle and end of this period: Josuf Koudelka’s documention of the abrupt end of the “Prague Spring” in 1968, when Soviet-led Warsaw Pact tanks re-established Soviet dominance, and “Behind the Velvet Curtain: Seven Women Artists from the Czech Republic,” where women played the most important peaceful role in ending Soviet rule and making way for freedom and democracy.

I’ve had first-hand knowledge of Bernis and Peter’s multimedia collaborations as artists since the 1970s, but Prague Revisited was an unexpected pleasure, too thoughtful for a tour guide and too intimate as well. It begins with photos of the life, art, and architecture of Prague taken by Peter’s mother, Ilse von zur Muehlen, during the war. They were accompanied by Peter’s memories as a child, including one of carpet bombing, when American pilots mistook Prague for Dresden. At a later point in Prague Revisited, Bernis and Peter trade off on writing about the photographs and the subjects depicted, not identifying whose voice is whose, or even whose photographs are whose.

One might soon learn that the black and white infrared photographs in the book could only have been taken and developed by Bernis. It was a time when Peter was fully engaged with introducing color into his own bold compositions. Eventually, both artists would use color, with only a difference in their format to distinguish them; and the book doesn’t let you know who used what format.

Similarly, one could recognize Bernis’s journal entries by their more intimate, poetic constructions, but the rest of the text is more of a collaboration between the poetry and clarity found in both. It is this gesture of making their explanations and observations interchangeable, without ownership, that makes Prague Revisited so successful. This collaboration allows the viewer to enter the space and sensibility of the other—to remember and to truly know. Exhibitions and individuals alone could not do this.

The images in this section, taken in 1985 and 1990, depict the “John Lennon Wall” belonging to the Knights of Malta located on the Maltese Square, or Maltézské Náměstí, in Malá Strana, just past Charles Bridge. The wall, situated across the French Embassy, began its life as an underground community board in the early seventies with love poems and short messages against the regime. It received its first decoration dedicated to John Lennon, symbol of Western culture and freedom, after his assassination in December 1980, when an unknown artist painted an image of Lennon and some lyrics. In 1985, parts of the wall were sparsely covered with stick-figure drawings, antiwar messages, and crude graffiti paying homage to Lennon and the Beatles. By 1990, the wall had become a shrine. At one end, below a large painting of the Beatle Saint, we find offerings of cookies, scraps of photos, and even cigarettes. The rainbow-colored arch enveloping Lennon’s face, whose dark and light halves suggest the Yin/Yang symbol, evoke the image of a shrine to Ganesh in Kathmandu—once the gathering spot for hippies of the psychedelic sixties.

Dominating the wall is a giant portrait of Lennon’s face, captioned by the legend,

As with all graffiti, the wall’s enduring quality is impermanence. During Communism, the authorities took the wall for what it was: a forum for public dissent that needed to be cleansed, only to find new messages soon after. Since the Velvet Revolution, the wall has undergone perpetual change, once even being completely whitewashed. In 2020, one painting of John will depict him wearing a face mask, printed with the words: