. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Architecture’s original project was the invention of interiority, an enclosed area delimited from its context and made available for a narrowly defined public, function, and meaning.

This original project was expanded during the Enlightenment period with the invention of type to establish architectural and social institutions for molding subjectivities.

This quest for interiority has reached its completion with world capitalism and its associated complexes, the ultimate interior without any possible or imaginable outside.

In response to this condition, Typologies for Big Words argues that the original architectural project— the conception and design of interiority—needs to be replaced by a new one: the conception and design of exteriority.

This book is a series of projects reimagining traditional building and landscape types as openings within the interiority of the current global system.

Typologies for Big Words proposes new types of spaces as holes within society’s big words.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

FACTORY OF ECOLOGY INFRASTRUCTURE OF INTIMACY MAUSOLEUM OF HUMANITY WAITING ROOM OF DEMOCRACY MEDIA LAB OF SAFETY OFFICE OF DIVERSITY MUSEUM OF CAPITALISM EPILOGUE

Introduction

Architecture has been interiority.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

The Project of Interiority

Interiority should not be mistaken for indoor space. Instead, interiority refers to the act of bounding space from its context.

Arguably, “the distinctive quality of any man-made place is enclosure.” 1

While this statement by Christian Norberg-Schulz might not be self-evident, it points to the spatial quality invariably found in any human-made place across cultures that defines a likely universal understanding of outsideinside relationships.

For example, the Romans used the concept of locus to define the relationship between a concrete location and the buildings in it.

As described by Aldo Rossi, important Roman sites were “governed by the genius loci, the local divinity, an intermediary who presided over all that was to unfold in it.” 2

The locus signifies a singular space as it “emphasizes the conditions and qualities within undifferentiated space.” 3

Different versions of the expression genius loci and the attitude toward this “spirit of place” can be found in most cultures.

While this condition does not necessarily have to be rendered physical as an enclosure, it does convey an

1

—Christian Norberg-Schulz, Genius Loci: Towards a Phenomenology of Architecture (New York: Rizzoli, 1980), 58

2—Aldo Rossi, The Architecture of the City (Cambridge, ma: mit Press, 1983), 103

3—Ibid.

extension and, thus, a similar outside-inside relationship with the surrounding “undifferentiated space.”

In her analysis of the relationships between Roman architecture and rhetoric, Gretchen Meyers states that “unlike the Greek process, which involves selecting concepts or images from a mental store of sequentially arranged items, the Roman concept of memory invites the user to enter a physical space (locus) within the mind and recall the idea or image associated with that space.”4

More relevant to the arguments that sustained this book is the fact that “Roman rhetorical treatises indicate that physical places, specifically architectural ones, provide the ideal form of locus to house ideas for memorization or arrangement within a speech.” 5

In the Roman tradition, a locus does not merely signify a singular space.

It also refers to an interior space housing unique ideas. Therefore, the boundary between inside and outside does not merely demarcate a spatial differentiation.

It is a threshold that collapses space and public speech.

The Roman rhetorical technique of using a locus to anchor memory indicates how deeply rooted within the Western tradition is interiority as the framework to house and communicate ideas.

The focus on the conception and imagination of interiority is also present in landscape architecture.

4

—Gretchen E. Meyers, “Vitruvius and the Origins of Roman Spatial Rhetoric,” Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome, vol. 50 (2005): 70

In his article “A Built Landscape Typology,” Patrick Condon argues that “the forest and the clearing, understood as a dialectical pair, are the archetypal landscape space foundation upon which the edifice of a designed landscape space typology can be created.” 6

While clearings occur naturally without human intervention via ecological processes, they can also be designed.

Building upon the work of René Dubos, Jay Appleton, and George Frazer, Condon postulates that the clearing in the forest is the most primordial room ever designed.

A clearing, an area free of trees in the woods, is a distinctly defined, bounded, and contained space that establishes clear boundaries between its interior and outside worlds.

Another essential landscape type worth noting to emphasize the importance of in-teriority in landscape architecture’s original aims is the Latin expression hortus conclusus.

It describes the enclosed gardens commonly used in depictions of the Virgin Mary in Christian paintings from the Middle Ages.

This type of garden was used to symbolize purity and virginity through its enclosure from the outside world.

While the expression hortus conclusus depicts the

6—Patrick Condon, “A Built Landscape Typology: A Language of the Land We Live In,” in Ordering Space: Types in Architecture and Design, eds. Karen A. Franck and Lynda H. Schneekloth (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold, 1994), 89

Types as Interiorities

relationship between enclosed gardens and Christian values, enclosed gardens are a foundational space of every culture.

Their use across cultures shows similar associations between enclosed space and specific socio-cultural values.

The concept of architectural type was theoretically articulated following the rational philosophy of the Enlightenment.

Despite their innovative role as formal mechanisms, types also advanced architecture’s original quest for interiority by unleashing interiority’s power to shape subjectivities.

Since the publication of Quatremère de Quincy’s Dictionnaire Historique de l’Architecture in 1832, many authors have elaborated

7—A bibliography recording all works dedicated to this initiative would be as extensive as the history of architecture since the middle of the 19th century. So, for a brief introduction on the matter in addition to the aforementioned work by Aldo Rossi, see: Samir Younés, The True, the Fictive, and the Real: The Historical Dictionary of Architecture of Quatremère de Quincy (London: A. Papadakis, 1999); Giulio Carlo Argan, “On the Typology of Architecture,” Architectural Design, vol. 33, no. 12 (December 1963): 564–565; Anthony Vidler, “The Idea of Type: The Transformation of the Academic Ideal, 1750–1830,” Oppositions, no. 8 (Spring 1977): 94–115; Rafael Moneo, “On Typology,” Oppositions, no. 13 (Summer 1978): 23–45.

competing definitions of architectural type over the last couple of centuries.7

Here, I rely on Rafael Moneo’s analysis and overall historical account of the concept of type as it appeared in his well-known essay “On Typology.”

In my view, it summarizes the most widely shared canonical understandings of this architectural concept.

In simple terms, a type is “a concept which describes a group of objects characterized by the same formal structure.”8

The concept is fundamental to architecture because, as he argued, architecture “is not only described by types, it is also produced through them.”9

This harmless sentence—which has received little to no attention because most architects and designers of other related fields of the built environment agree with it without much hesitation—points to critical confusion.

While the producers of architecture Moneo refers to are assured to be the architects, it is unclear who describes architecture.

Granted, the writing of the sentence in passive voice does not help clarify this question.

Moneo states and the first few images of vernacular settlements and villages included in the article suggest that, as a formal structure, a type is “intimately connected to reality.”10

8—Rafael Moneo, “On Typology,” Oppositions, no. 13 (Summer 1978): 23 9—Ibid. 10—Ibid., 24.

However, since the article focuses on types as mechanisms conceived theoretically for and used by architects, the reader quickly assumes that architecture’s describers must be architects too.

Several authors have wrestled addressing the tension between the description and production of types or, in other words, between the social and disciplinary realities within which types ultimately exist.

For example, Aldo Rossi unambiguously pointed out the limitations that arise if one considers the differences in perception of the same reality held by different individuals.

“Thus, the concept that one person has of an urban artifact will always differ from that of someone who ‘lives’ that same artifact. These considerations, however, can delimit our task; it is possible that our task consists principally in defining an urban artifact from the standpoint of its manufacture.” 11

While Rossi presents an argument that is coherent with the morphological method he laid out in his book, it is fair to say that his statement encapsulates the difficulties faced by most theoreticians and writers of this matter.

Ultimately, most definitions of the concept of type have been limited to its role in architectural production.

A more comprehensive description of the concept of type requires admitting that these formal structures are simultaneously disciplinarily and socially produced and described.

Building types are not only formal structures.

11—Aldo Rossi, The Architecture of the City (Cambridge, ma: mit Press, 1983), 33

In the public’s mind, these spaces are also physical manifestations of social institutions12 (be it the home, the school, or the place of prayer, for example) that cater to and construct specific subjectivities.

Several authors have pointed this out, but the most wellknown analysis on this matter is Michel Foucault’s studies of modern institutions and their role in constructing modern society.13

Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri have furthered this framework by pointing out how the physical singularity of these institutions limits their social influence within their spatial boundaries.

“The institutions provide above all a discrete place (the home, the chapel, the classroom, the shop floor) where the production of subjectivity is enacted. In the course of a life, an individual passes linearly into and out of these various institutions (from the school to the barracks to the factory) and is formed by them. The relation between inside and outside is fundamental. Each institution has its own rules and logics of subjectivation: “School tells us, ‘You’re not at home anymore’; the army tells us, ‘You’re not in school anymore.’”14

12

—I am not using the term “social institution” here as a placeholder for function or program. Therefore, I am not taking a functionalist approach to the concept of type. Instead, I am pointing out the institutional role and character inherent to any building type.

13

—Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison (New York: Vintage Books, 1979).

14

—Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge, ma: Harvard University Press, 2000), 196

Additionally, they have also indicated that it is necessary to pay attention to the tensions between the inside and outside of all social institutions to understand the construction method of modern subjectivities.

“Nevertheless, within the walls of each institution, the individual is at least partially shielded from the forces of the other institutions; in the convent, one is normally safe from the apparatus of the family, at home, one is normally out of reach of the factory discipline. This clearly delimited place of the institutions is reflected in the regular and fixed form of the subjectivities produced.”15

For this reason, while architects do not ultimately require this social aspect to activate the formal mechanisms of type to produce architecture, architecture is nevertheless described as institutional types by the public through their social perceptions and experiences.

Architectural types, then, are mechanisms with a dual nature.

They have a formal-institutional duality: types are formal structures and physical manifestations of social institutions depending on whether architecture is being produced or described.

As institutions, building types are interiorities that reify paradigmatic socio-cultural practices and, as a result, contribute to the construction of approved subjectivities.16

15—Ibid.

16—The argument I have laid out here has focused exclusively on the articulation of architectural type, in general, and building types, in particular. However, landscape types, as formal structures, also abide by similar principles.

Theorists have long argued that there is no space available beyond world capitalism and its associated complexes as the prevailing global system of organization.

Hardt and Negri seem to have summarized this best, arguing that “in its ideal form there is no outside to the world market: the entire globe is its domain.” 17

The development of this condition has triggered specific cultural shifts, resulting in new spatio-temporal logics and sensibilities.18

Broadly, the origins of this assessment can be found in the foundations of the philosophical discourse of Postmodernism as defined by the works of Michel Foucault and others with their criticism and re-appraisal of the socio-cultural discourses and practices developed in the period between the Enlightenment and Modernity.

Specifically, this condition without an outside was synthetically captured by Jacques Derrida’s in the now-famous sentence from his book Of Grammatology “il n’y a pas de hors-texte,” and (mis) translated by Gayatri Chakravorti Spivak’s as “there is nothing outside of the text.”

17—Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge, ma: Harvard University Press, 2000), 190.

18—See: David Harvey, The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the Origins of Cultural Change (Oxford and Cambridge, ma: Blackwell, 1990); Fredric Jameson, Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham: Duke University Press, 1991).

Spivak’s literary translation, which she immediately followed with the literal translation “there is no outsidetext”19 for purposes of clarity, has nevertheless caused multiple discussions and disagreements.

Despite these misinterpretations, Spivak’s choice of words was an apt one because it pointed to the essence of these thinkers’ argument: the inherited socio-cultural discourses and practices had produced an interiority that did not account for the possibility of an outside—and, consequentially, the existence of counter-discourses and counter-practices.

A wide variety of authors later furthered this understanding, signaling that Derrida’s textual framework could be applied to every other realm and demonstrating that the inherited collective conscience lacked an outside in multiple different fields.

Within the field of architecture, Elizabeth Grosz used the work of Bergson, Deleuze, Irigaray, and others to address this philosophical question and show how this condition of interiority can be managed and subverted with the medium of architecture itself: space.20

More recently, Hardt and Negri have analyzed this question in their book Empire in broad socio-cultural and politicoeconomic terms.

As they succinctly stated, the world defined by the current regime is a place where “there is no more outside.”21

19—Jacques Derrida, Of Grammatology (Baltimore and London: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1976), 158

20—Elizabeth Grosz, Architecture from the Outside: Essays on Virtual and Real Space (Cambridge,ma: mit Press, 2001).

They use “Empire” as a concept that allows them to think theoretically about the current world order.

“The concept of Empire is characterized fundamentally by a lack of boundaries: Empire’s rule has no limits.”22

This condition of a limitless regime occurs spatially (“rules over the entire ‘civilized’ world”), temporally (“a regime with no temporal boundaries and in this sense outside of history or at the end of history”), and socially (“object of its rule is social life in its entirety, and thus Empire presents the paradigmatic form of biopower”).23

While “Empire” is a concept to theorize the current regime, its capitalist foundations operate with a similar appetite:

“The capitalist market is one machine that has always run counter to any division between inside and outside. It is thwarted by barriers and exclusions; it thrives instead by including always more within its sphere.” 24

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Italian design group Archizoom was already aware of this internalized condition.

They argued that cities are a self-enclosed reality, a continuous capitalist space without outside:

“The carrying out of a social organization of labor by means of Planning eliminates the empty space in which Capital expanded during its growth period. In fact, no reality exists any longer outside the system itself: the whole visual relationship with reality loses importance as

21—Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge, ma: Harvard University Press, 2000), 186–190

22—Ibid., xiv.

23—Ibid., xiv–xv.

24—Ibid., 190.

there ceases to be any distance between the subject and the phenomenon.”25

This relationship—a lack of distance between a subject and the urban-architectural phenomenon—is a poetic yet apt spatial illustration and translation of interiority.

In addition to this awareness, they also realized this phenomenon “is the weakest point in the whole industrial system.”26

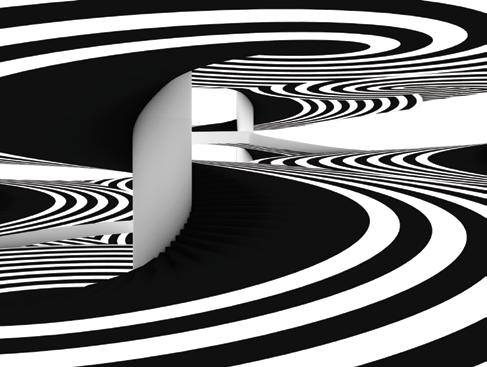

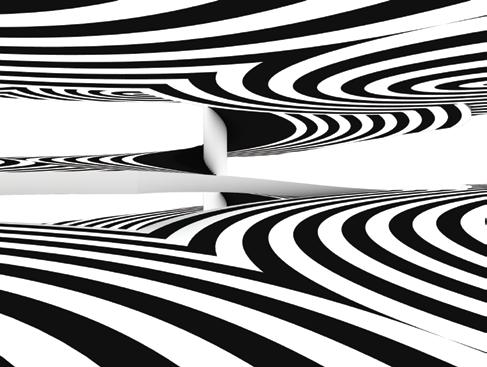

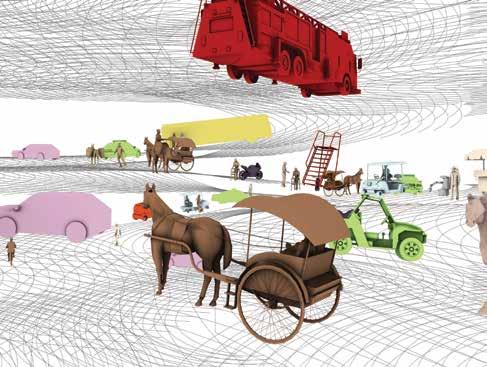

So, as a response to this overall assessment, Archizoom designed “No-Stop City,” a visionary critique toward urbanization and its constitutive elements.

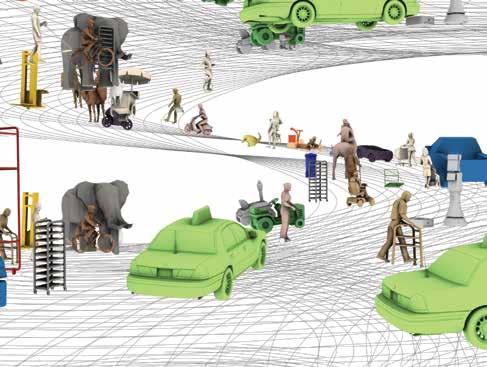

“No-Stop City” is an infinite, interior, white, and gridded space occupied by various homogeneously distributed architectural components.

Archizoom’s city is a never-ending sublime environment of epic dimensions portraying the unprecedented delightful horror of capitalist space.

The fully interiorized world of “No-Stop City” acutely foresaw the present moment in time and its fulfillment of architecture’s original project—the conception and design of interiority.

For clarity purposes, it is necessary to note that Archizoom’s “No-Stop City” operates at two levels of interiority.

25

—Archizoom Associati, “No-Stop City: Residential Car Park Universal Climatic System,” in No-Stop City: Archizoom Associati, ed. Andrea Branzi (Orléans: Hyx, 2006), 178

Firstly, these are indoor spaces without an external image as no outside views of this interior space are provided.

This interiority can be understood as physically selfevident and, ultimately, superficial.

Secondly, as described, this project proposes a space derived from capital’s influence where the distance between the subject and the urban-architectural phenomenon has disappeared.

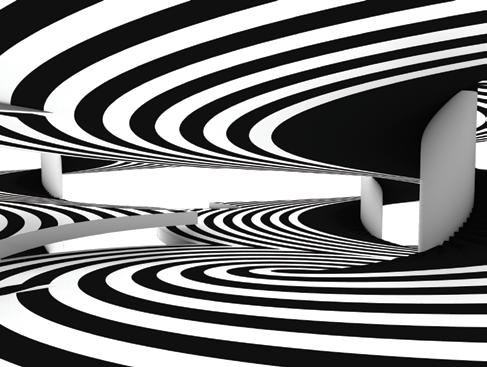

“The city no longer ‘represents’ the system, but becomes the system itself, programmed and isotropic, and within it the various functions are contained homogeneously, without contradictions.”27

This lack of distance is masterfully expressed architecturally through an inescapable interiority.

“No-Stop City” is not an architectural milestone because it presents a never-before-seen interior space.

But because Archizoom unambiguously collapsed both conditions of interiority (the physical and the economic) into a single architectural space.

Archizoom’s originality revealed that architecture’s quest for interiority matched capitalism’s appetite for ever-growing and allencompassing maximization.

Architecture’s original project became identified with the spatial characteristics of the present politico-economic regime.

This unintended identification has become architecture’s big con: the search for interiority as a shelter from the outside world when, in reality, there is no outside.

A

New Mission

Archizoom’s work foresaw the challenges architecture would encounter when completing its original project after a historical era of approximately two millennia and anticipated the current conundrum faced by designers of the built environment when architecture and other parallel disciplines have run their course.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

At this moment in time, architecture’s original mission—the conception and design of interiority—must be flipped.

Architecture’s new mission is the conception and design of exteriority.

However, the initial clarity of this mission is complicated by two factors.

First, the absolute interiority of the current politicoeconomic condition renders exteriority impossible.

Hardt and Negri have analyzed previous political strategies as possible alternatives to Empire, from classical local struggles to the “Internationale.”28

Since Empire lacks an outside, they conclude that Empire is a regime different from previous ones and, for this reason, none of the known historical strategies and tactics are helpful any longer.

Instead, they argue that “every struggle must attack at the heart of Empire, at its strength,”29 implying that “the only strategy available to the struggles is that of a constituent counterpower that emerges from within Empire.”30

28—Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Empire (Cambridge, ma: Harvard University Press, 2000), 42–63.

29—Ibid., 58

30—Ibid., 59.

Proposing an outside to the present spatial regime is not feasible.

The alternatives to this interiority are not found outside but within it.

Therefore, this first complication concludes that what “a world that knows no outside” now requires from the design disciplines of the built environment are openings within the prevailing system.

Second, the ongoing collapse of the institutional loci makes the formalinstitutional duality of the type obsolete.

As Hardt and Negri have insightfully argued, “today the enclosures that used to define the limited space of the institutions have broken down so that the logic that once functioned primarily within the institutional walls now spreads across the entire social terrain. Inside and outside are becoming indistinguishable.”31

In this context, a type can continue to be described as a formal structure with interior space.

But this interiority does no longer have an institutional role.

It does not define an institutional locus.

Formal structures have been emptied of socio-cultural meaning.

The type’s formal-institutional duality is now obsolete.

The second complication concludes that the type’s formalinstitutional duality must be replaced.

Due to these two factors, the building and landscape types necessary to establish openings within the prevailing global system are of a different kind.

The new types are no longer loci within the fabric of the prevailing global system.

Instead, they are openings within it.

These new types tear the fabric that currently occupies everything and denies the possibility of an alternative reality.

In so doing, they reestablish the missing distance between the subject and the urban-architectural phenomenon.

They are gaps.

Types can no longer be understood as loci but as gaps.

Building and landscape types cannot be individual structures amongst others with similar formal characteristics.

They cannot reify patterns of paradigmatic socio-cultural practices; they must be voids.

The world might know no outside, but it needs gaps as opportunities for non-paradigmatic subjectivities.

These openings are spaces for everyone and everything not accepted by the system and characterized as unwanted, strange, different, questionable, inconceivable, unimaginable, or marginal.

Consequentially, the old formal-institutional duality is now replaced by a duality expressed as a nonparadigmatic gap.

Several questions might arise as a consequence of this process.

In particular, the reader might be asking that if a formal structure no longer belongs to a group of objects with similar formal characteristics, how can it be considered a type?

Also, if a formal structure can no longer define an institutional locus, is it a type?

The responses to these two questions would differ in aspect but are the same in essence.

The type that I am proposing is no longer a formal structure amongst others with similar characteristics that can define institutional loci.

The new kind of type offered here is a void as an opening for the emergence of non-paradigmatic subjectivities.

Finally, the reader might also wonder if it is necessary to maintain the concept of type under the new circumstances.

Or if types are a spatial concept linked exclusively to the production of interiority.

Type is a mechanism that is fundamental to the disciplines of the built environment.

The relationship between individual and collective forms of life is established through types, both in the production and description of designed space.

Additionally, designers of the built environment manage tensions between a singular space and its context in the broadest sense (from socio-cultural relationships to means of production) through types.

Type is a necessary invention.

It merely needs to be redescribed.

Typologies for Big Words

.

This book argues for a new idea of typology exemplified through a new set of types.

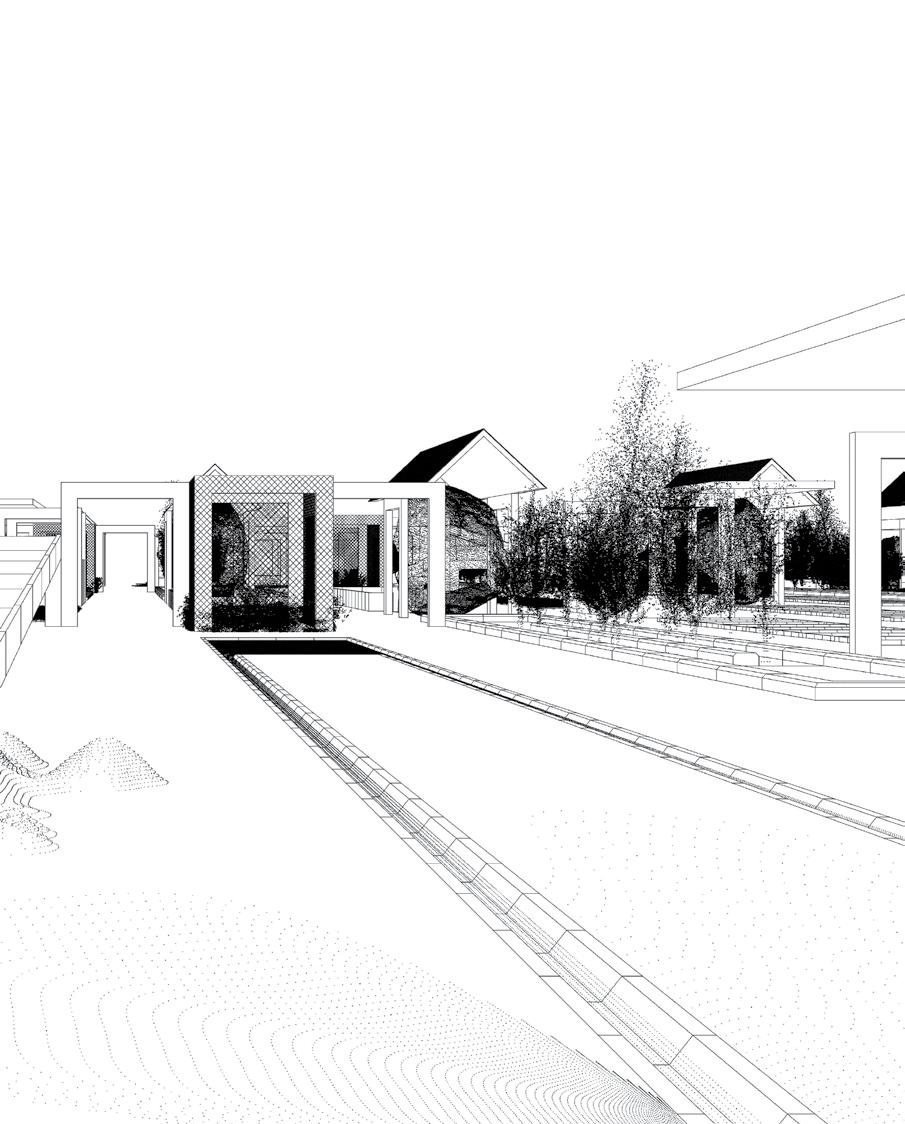

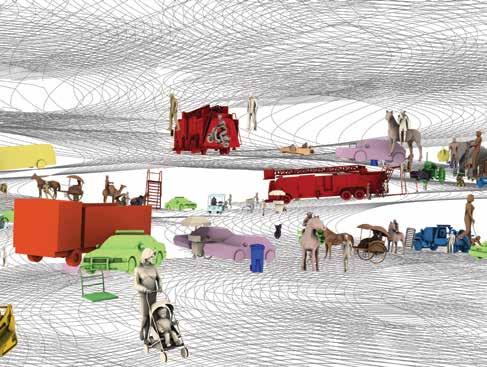

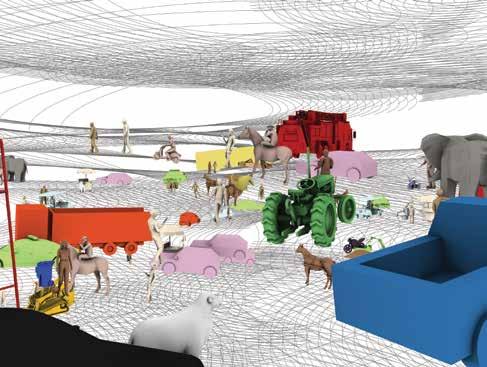

Typologies for Big Words is a series of projects reimagining traditional building and landscape types as openings within the interiority of the current global system.

Unlike traditional types, the ambitions of the types proposed here are singular rather than comprehensive.

These new spatial types are propositions for openings to the socio-cultural and politico-economic system.

They have a diametrically opposite mission to the one of the museum, the church, or the school, for example.

Typologies for Big Words imagines openings by reimagining building and landscape types that address current socio-cultural sensibilities through poetic rather than syntactic or semantic means.

The projects included in this book present new alternative spatial expressions for selected social institutions, imagined or real.

These new spaces are designed as openings and places of discovery and respite rather than as localities reifying existing institutional roles and practices.

These projects are not demonstrations.

Instead, they are allegories of how the world could operate (eventually or right now).

They are intended to be absurd, funny, engaging, and frightening.

They represent a search for a space for new uncategorized subjectivities that can lead to a new innocence and a new sublime.

Contrary to the customary structure of most design monographs, projects in this book are not presented via a short description of the project’s qualities.

Neither are they introduced by a so-called critical text written by a person different from the projects’ author

Typologies for Big Words is not a monograph.

Instead, this book presents a method for constructing an intellectual position by searching for a distinct spatial and aesthetic sensibility.

In this book, each project comprises an inseparable pairing of a design proposal and a theoretical essay.

These two pieces of work are not independent of each other: text and figures (drawings and images) go along each other, hand in hand.

The figures illustrate the project’s theoretical argument as much as the essay illuminates the rationale behind the design proposal.

Most critical texts included in monographs are written before or after the projects’ development.

In these cases, projects act as demonstrations or illustrations of theoretical positions.

In this book, the design proposal and the theoretical essay were developed simultaneously, in a coordinated fashion, influencing each other at each critical decision.

This working method mixes each design proposal with its theoretical essay, making them flow in parallel.

The output of this working method is Typologies for Big Words, a book that must be understood simultaneously as a method and product rather than as a catalog or monograph.

These projects redesign traditional types (factory, office, mausoleum, etc.) as holes opening up in contemporary society’s big words (ecology, democracy, capitalism, etc.).

Consequently, each project is named after a spatial type and a big word, such as Factory of Ecology or Museum of Capitalism.

Typologies for Big Words includes seven projects.32

1 Factory of Ecology

This project simulates efficient building techniques while triggering ground disturbances to create conditions appropriate for plant growth.

2 Infrastructure of Intimacy

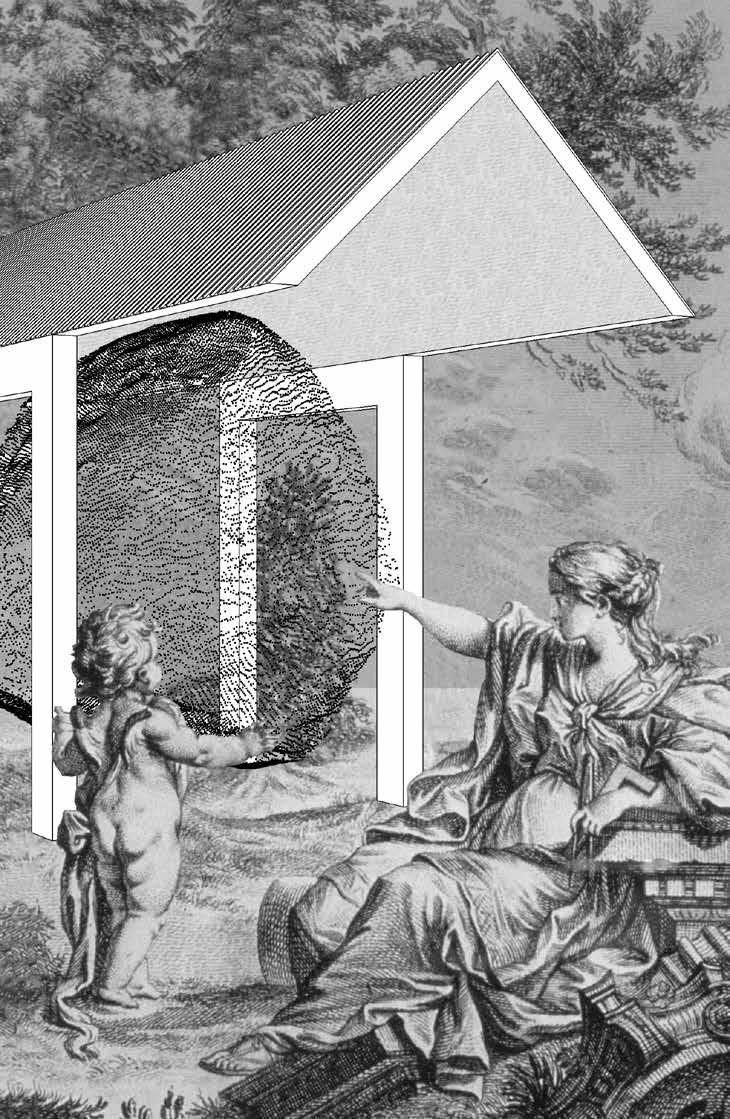

This project defies technological, political, and economic urban prejudices by using a balloon-looking portable device that allows citizens to create intimate spaces.

3 Mausoleum of Humanity

Mausoleum of Humanity is a repository of our current genome: a time capsule that holds the 1.0 version as it stands today after millions of years of natural evolution

32

—All projects have been completed by Holes of Matter. Holes of Matter is a design studio operating at the intersection of architecture and landscape. Its mission is to examine the patterns arising from the mutual influence between sociocultural forces and spatial organizations and imagine gaps in them as the means to redefine relations between individual and collective forms of life.

Holes of Matter is led by the author.

and safeguards our memory before we alter it, perhaps irrevocably.

4 Waiting Room of Democracy

While traditional spaces of democratic assembly such as parliaments, protests, or speakers’ corners have typically been conceived and designed for crowds, this project proposes a room for two strangers—and two strangers only—to listen to each other.

5 Media Lab of Safety

By demonstrating how a media lab can be built with so-called low-quality building technologies, this project argues that media is best addressed with cultural values rather than technological ones.

6 Office of Diversity

Office of Diversity is a seemingly post-political space where workers, as “entrepreneurs of themselves,” autoexploit themselves through the fluidly interchangeable conditions of labor and leisure, freedom, and domination.

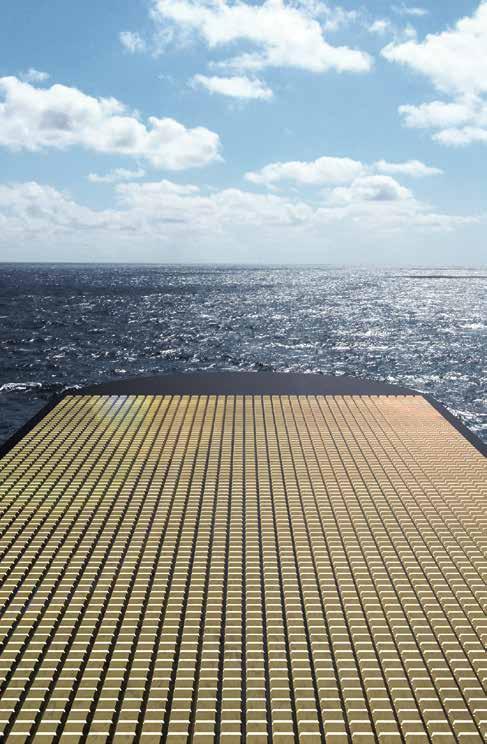

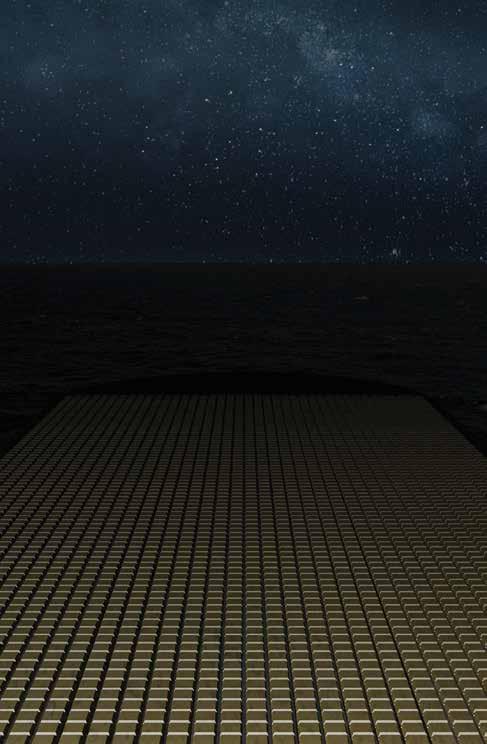

7 Museum of Capitalism

This project envisions a time when the global financial system is on the brink of complete collapse, and, in a moment of exceptional collective lucidity, all countries decide to label gold as toxic waste and place it on a ship named “Arbitrary Equivalent,” a floating Museum of Capitalism.