By DK Osseo-Asare

By DK Osseo-Asare

In 1960, Osagyefo1 Dr. Kwame Nkrumah, the first president of the Republic of Ghana—the first country in SubSaharan Africa to gain independence from colonial rule—hired Doxiadis Associates to design a revised master plan for the new town of Tema, as centerpiece of a national development plan framed according to the ekistics model of human settlement formation.2 Tema was conceived as an urban-scale engine structured to accelerate industrialization for the express purpose of economic growth; a “city of industry” built in order to convert hydroelectric power generated by the Akosombo Dam—part of the Volta River Project, which created at that time the world’s largest manmade lake—into materials and products for domestic use and export.3

In this sense, Tema’s origin coincided with the contemporaneous thrust within town and country planning toward functional zoning, in that hierarchy and order were weaponized on behalf of business interests that advantage the state by augmenting both its wealth and its authority. At the dawn of Africa’s postcolonial era, “modern” modes of city-making served to reorient the masses from so called “informal” market dynamics—i.e. indigenous modes of non-monetary commercial exchange and customary regimes of social value propagation, decoupled from central government control—to spatially coordinated “formal” economic and legal structures, taxed and regulated by the state, and primed for interfacing optimally with global trade and finance.

Sixty years later, Tema—with a population over twice that projected by the Doxiadis master plan—has conjoined with Ghana’s capital Accra into a twin cities conurbation, while Africa more broadly is urbanizing at the fastest rate in human history. Rapid growth of cities across the continent today continues to reinscribe, at the macro scale, the architectonic modernity of Western capitalism, whereby the production of the city corresponds to the destruction of nature, courtesy of extractive and non-regenerative commercial exploitation. However, there exists within this same terrain, an alternative approach to development which represents a sort of bottom-up hack of architectural convention with respect to urban land use, material production and democratic potentiality of the life of the city.

A

A

Kiosk culture is an emergent phenomenon of customary urbanism widespread in West Africa—simultaneously cause and effect of the proliferation of mobile “microtecture” (i.e. micro-architectures and distributed infrastructure) deployed temporarily on an interim basis in/between interstitial, marginal, neglected, overlooked and contested spaces—the borders, the edges, the gray zones and the periphery of the city proper 4 When architecture works to promote Accra-Tema in the image of the global metropolis, building becomes ever more expensive in pursuit of concretized bigness and quasi-permanence, backed by documentation that seeks to proclaim legal land tenure, boundary walls and security fencing that serve to protect property against both armed robbers and the constant threat of encroachment.

In contrast, kiosks—and the full spectrum of tiny- and small-scale structures that fall within this typological category, ranging from sheds and shacks, to shanties, repurposed and locally fabricated shipping containers— operate exclusively, and tactically, in order to encroach. Kiosks in the context of Accra-Tema, and West Africa in general, typify affordability because they are low-cost and regenerative—typically constructed, in part, out of reclaimed and repurposed materials, byproducts of the building industry and the city’s waste stream. Specifically because they are deployable and not fixed in place—installed temporarily on land owned by other people, in locations and per ad hoc agreements negotiated between people not organizations, kiosks extend Holston’s spaces of insurgent citizenship5 into a distributed network of infrastructural affordance tuned to West African attitudes regarding urban flexibility.

Whereas Tema’s and Accra’s master planning aims to centralize control over the production of the city within a municipal apparatus, kiosks open up design agency to citizens of the city—regardless of wealth and status—by offering minimal units of architecture that can be built at a price point of several hundred to several thousand dollars and which, in aggregate, conform a massive swathe of interactive and transactional spaces geared for creativity and (micro-)enterprise. In virtually any West African city, kiosk culture is the realm wherein the majority of people obtain access to goods, services, hope and opportunity

Because kiosk culture engages directly with temporality, such site installations—considered architecturally—

Background: Kiosk barbershop/hair salon and carpentry workbench under a tree in an apartment block compound in Tema

Source: DK Osseo-Asare

“Luxury clothen” kiosk fashion boutique in Accra Source: DK Osseo-Asare

Welding workshop in Community 18, Tema, with in-progress work, located between housing and the street front Source: DK Osseo-Asare

Background: Kiosk barbershop/hair salon and carpentry workbench under a tree in an apartment block compound in Tema

Source: DK Osseo-Asare

“Luxury clothen” kiosk fashion boutique in Accra Source: DK Osseo-Asare

Welding workshop in Community 18, Tema, with in-progress work, located between housing and the street front Source: DK Osseo-Asare

are more akin an act of occupation to camping.6 Similarly, whether kiosk culture is a form of counterculture depends on your frame of reference. Once building includes mobility amongst design criteria, then size, scale and weight become important considerations.

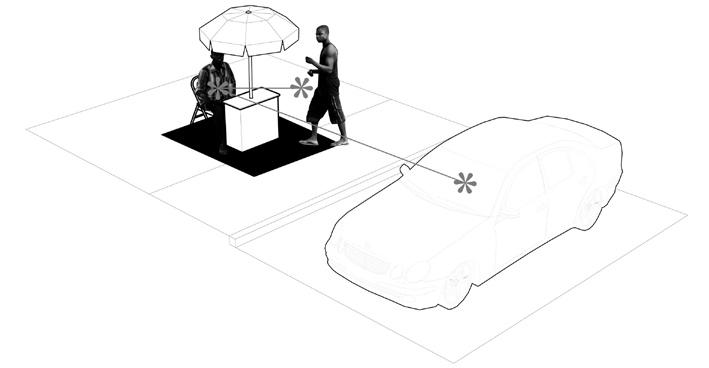

Kiosk culture proceeds across a range of scales, while its seeds lie in the transactional spaces of commerce and of production. Peddlers who circumnavigate the circuitry of the city, marketing their wares directly to potential customers, carry with them a personal space that they are capable of leveraging precisely for this purpose. Street hawkers who sell products on demand to drivers and passengers of automobiles, and who occupy in clusters certain intersections, traffic light areas, bus stops and paratransit zones, similarly claim personal space in public space, also primarily for the purpose of survival commerce.

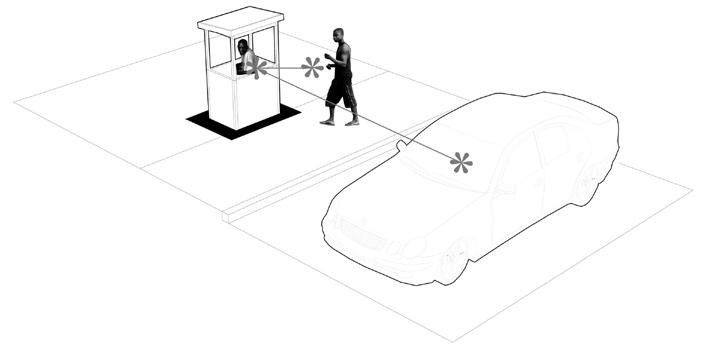

This sort of tactical and temporal staking out space within the city extends in duration by means of street furniture, urban umbrellas and the kiosk itself. The smallest types of kiosk are taller than they are wide, and operate more as an enclosed stall for standing or sitting on a chair or stool. A window serves as interface with the customer, bounding the space of transaction or exchange, at the same time that a door, for access into the kiosk, blurs the boundary between kiosk and the site where it is installed. It is not uncommon for kiosks to be occupied exteriorially, with both chair and operator sitting outside of the kiosk, or under a nearby tree.

A kiosk can also function equivalently to a container, understood architecturally as a heavy-duty industriallyproduced box, such as a shipping container, designed for transporting freight. In enough instances that one could track their trends, a shipping container filled with secondhand fridges, clothing or televisions in Europe, may be deposited road-side in Ghana as a pop-up sales depot. Or welders locally fabricate containers out of steel angle bars, folded sheet metal and custom-made door hardware. These containers do not necessarily follow ISO specifications, but can and are often made modularly as deployable kit builds for microentrepreneurs across West Africa.

Such micro-architectures of kiosk culture instantiate more as zones of occupation, with fluid boundaries and

constituents, than as conventional buildings. These zones can be compact or diffuse, and excel especially at expanding to test the limits of what they can get away with… Consider the carpenter that arrives in a location in order to make something. They will first install a table or workbench under a tree, or erect a canopy structure, then they may add a storage chest, a shed, a store room. They may make a bed, a sofa, a dog house or a wardrobe, and display it by the side of the road for sale. The space that they will claim or occupy will typically grow slowly unless checked by countervailing force, influence or barrier

In this manner, kiosks exhibit micro-territories. These micro-territories span a full range of scales, and most kiosks can permute into larger or more complex forms through accretion. Kiosks are inherently modular, and customizable; they are a mode of incremental building, whereby new additions or upgraded versions can be sequentially introduced as material or financial resources may allow, or as circumstances permit. Kiosks do serve as homes and refuge for millions of Africans, and in this capacity are part of the phenomenon of slum development world-wide. However, as an architectural typology the kiosk is not a tiny house.

Kiosks are equally if not foremost shops and workshops. Kiosk culture springs forth from the urgency of survival. When we co-locate in human settlements, especially at high densities, there is a basic need for not only sheltering in place, but also for the capacity to leverage one’s own micro-territory of occupation to support personal well-being. African cities can be expensive for those who are not wealthy. Rising costs of living in the emerging Abidjan-Accra-Lomé-Lagos megalopolis render survival a fundamental challenge for cashstrapped urban citizens. Kiosks are that architectural skin that empowers people to engage in commerce at an incrementally scalable pace that they can afford and with minimal risks that they can tolerate.

Kiosk culture is customary because it comes into being not because the law allows it, but because it is a way that people create affordable space within the city—to live, to work, to secure, to project and to dream. What can happen if we recognize that kiosk culture is integral to the DNA of West African cities, and that it may be counterproductive to view such interventions as urban blight, or transgressive aberrations that must be excised from the city?

Drivers of “bola carts”, a local mode of waste management, resting at their kiosk station

Source: DK Osseo-Asare

Installing a windmill in a kiosk community Source: AMP

Background: Kiosk as display closet, a microstore in a housing community near Tema market

Drivers of “bola carts”, a local mode of waste management, resting at their kiosk station

Source: DK Osseo-Asare

Installing a windmill in a kiosk community Source: AMP

Background: Kiosk as display closet, a microstore in a housing community near Tema market

Scene of shopfronts.

When kiosks accrete.

This line of thinking has been the kernel of our work over the past decade, leading to a series of microarchitectural proposals and prototypes that seek to demonstrate the democratic possibilities of designing radically more pixelated models of urban development that incorporate low-cost reconfigurable nodes— spatialized at the scale of people and small budgets—that, collectively, create networked geographies of affordance concatenating Africa’s urban past and future.

DK Osseo-Asare is co-founder/principal of transatlantic architecture and integrated design studio Low Design Office (LOWDO); cofounder of the pan-African open-source maker tech initiative, Agbogbloshie Makerspace Platform (AMP); and assistant professor of architecture and engineering design at Penn State University, where he directs the Humanitarian Materials Lab (HuMatLab) and serves as Associate Director of the Alliance for Education, Science, Engineering and Design with Africa (AESEDA). He received MArch and A.B. degrees from Harvard University for his work with kinetic architecture and network power. LOWDO’s biodesign project, Bambot: Fufuzela, was a finalist for the Museum of Modern Art’s 2019 MoMA PS1 Young Architects Program.

Notes:

1. Following his leadership during Ghana’s independence movement and subsequent transition to self-governance, President Nkrumah came to be known popularly as Osagyefo, which translates from the Twi language as “redeemer” or savior-father of the people.

2. Construction of Tema began in 1954, under direction of the then Tema Development Organization (now, Corporation) in association with the Public Works Department. In March 1960 the Government of Ghana enlisted Doxiadis Associates to conduct an ekistics study for the entire country, as well as the Accra-Tema metropolitan area, the AccraTema-Akosombo triangle, the Accra Plains, the Southeast Coastal Plains, and the full region of the Volta River Project. In July 1961 the Government hired Doxiadis Associates to produce a master plan for the 63 sq. mi. Tema Acquisition Area and a comprehensive development program for the town and industrial area over a 25 year period and projected population of 235,000-250,000. Documentation of Doxiadis Associates’ Tema design appears in Ekistics 13: 17, pp. 159-171. For ekistics study of Ghana see “Accra-TemaAkosombo” in Ekistics 11: 65, pp. 235-276.

3. Constantinos A. Doxiadis and his firm, Doxiadis Associates, additionally played a key role in the design agenda of Cold War geopolitics. See: Michelle Provoost, “New Towns on the Cold War Frontier: How modern urban planning was exported as an instrument in the battle for the developing world”, URL: https://www.eurozine.com/new-towns-on-the-coldwar-frontier-4/

4. This usage of “kiosk culture” was coined as part of an MArch thesis at Harvard GSD (Osseo-Asare, 2009) entitled, “In/formal kiosk culture: building information networks on the street”. First published as “Africentri-city: From Kiosk Culture to Active Architecture”, NOMA Magazine, vol. 6, 2010, pp. 12-17. Subsequently reprinted in the exhibition catalog, Nana Oforiatta-Ayim / ANO Ghana (Accra), “Kiosk culture”, 2015. Also online at: https://www.culturalencyclopaedia.org/africentricity-entry

5. James Holston. “Spaces of Insurgent Citizenship.” In Making the Invisible Visible: A Multicultural Planning History,

Leonie Sandercock. Berkeley: University of California Press,

As Charlie Hailey

As kiosks increase in size and scale, shifting materials from plywood to custom-corrugated steel sheets, they transition linguistically into containers, locally-fabricated and non-standard