New hope for the northern white rhino

ANIMALS THAT RULED BEFORE THE DINOSAURS 10 Spectacular condors in the Andes

The trophy hunting debate

Sir David Attenborough’s

New hope for the northern white rhino

ANIMALS THAT RULED BEFORE THE DINOSAURS 10 Spectacular condors in the Andes

The trophy hunting debate

Sir David Attenborough’s

The inside story of the epic new BBC series

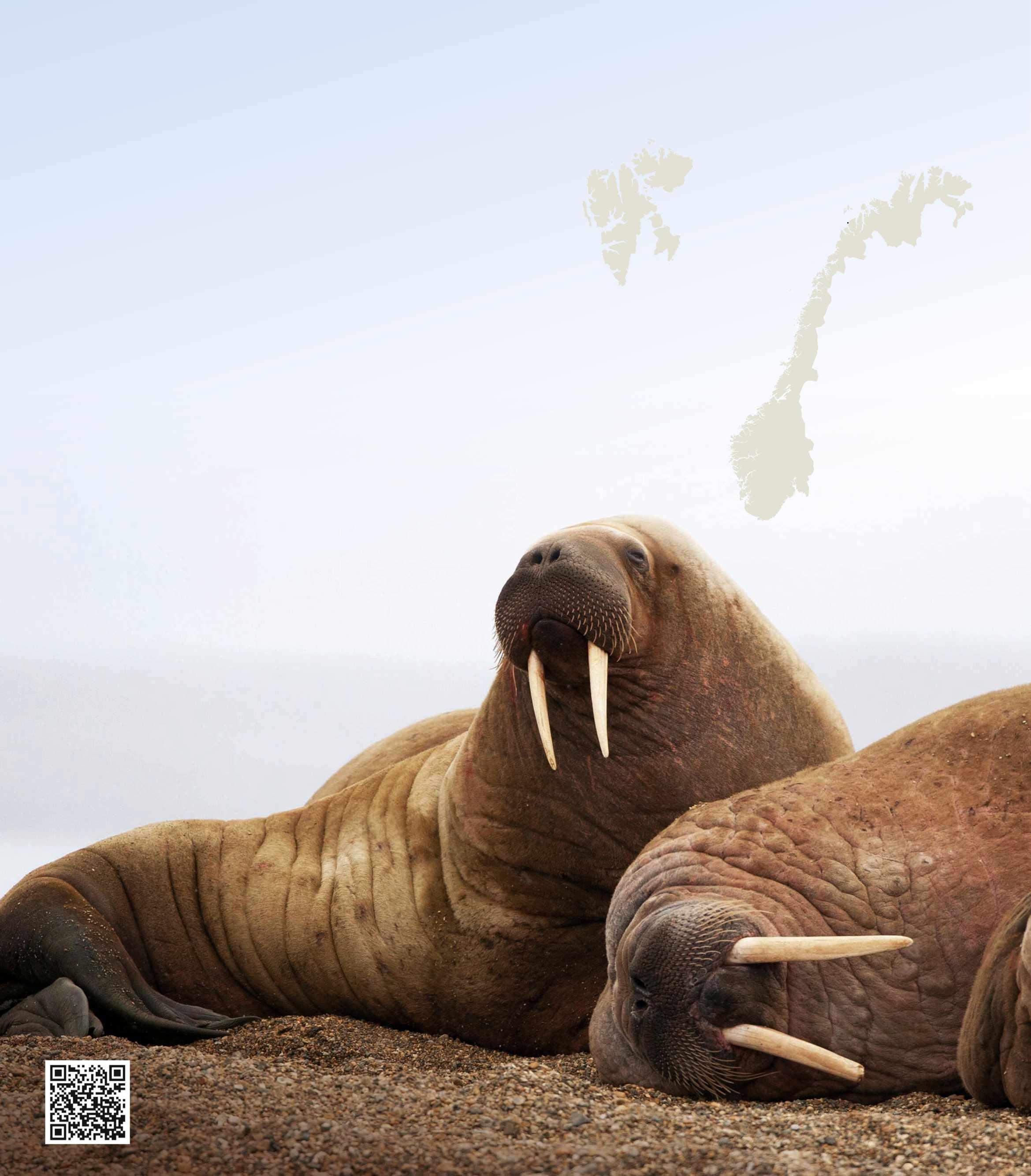

The wildlife and scenery at the top of the world are unlike any other on Earth. On The Svalbard Express, watch walruses basking in the sun along sandy beaches. Look for migrating pods of whales; for sea eagles soaring high above turquoise fjords and verdant mountains or for families of reindeer dotted among Svalbard’s jagged mountain ranges.

Departures: May – September 2024

Bergen – Longyearbyen – Bergen

Book Now

North Cape 71¡N

Honningsvåg

Ny-Ålesund

Longyearbyen

SVALBARD

Bjørnøya

Svolvær

Tromsø

Senja Træna

Stokmarknes

66°33'N ARCTIC CIRCLE

Brønnøysund

Ålesund Åndalsnes

Bergen NORWAY

Urke

COVER IMAGE: ANDY ROUSE; BBC PANEL: GETTY; RHINO: JON A

Egyptian bas-relief

Presenter Adam Walton meets two researchers from Bangor University to learn about the diversity of venomous snakes found across ancient Egypt by combining ancient texts with current technology.

Catch up on BBC Sounds

Earth from space

In this new series, Emily Knight explores the stories that sophisticated tracking devices can tell us about animals, as well as their surroundings, including climatic conditions and the health of ecosystems in a rapidly changing world.

Catch up on BBC Sounds

The world’s oldest fossilised forest was recently uncovered in Somerset.

Palaeobotanist Christopher Berry sheds light on the cladoxylopsids that lived 390 million years ago and reveal extraordinary evolutionary secrets. Catch up on BBC Sounds

wildlifemagazine@ourmedia.co.uk

instagram.com/bbcwildlifemagazine twitter.com/WildlifeMag

facebook.com/wildlifemagazine

There is still hope for the northern white rhinoPAUL McGUINNESS, EDITOR

Only two northern white rhinos remain, and they’re both females, and both incapable of carrying a pregnancy to full term. Surely extinction is just a matter of when, not if? And yet, as Jon A Juárez illustrates in his remarkable Portfolio feature this month (p46), there is still hope.

Using the very latest science, a project is underway in Kenya to use a surrogate southern white rhino mother to incubate a northern white rhino embryo created in a laboratory using harvested eggs and frozen sperm. Human IVF is unimaginably stressful and delicate, and very often unsuccessful, so attempting the same process with a wild animal of such size is hard to believe.

The northern white is not out of the woods yet, but where there’s a will, science is hopefully finding a way!

editor Paul McGuinness

managing editor Sarah McPherson

production editor Catherine Mossop seo lead Debbie Graham

contributors

Scott

Lucy Cooke, Mike Dilger, Holly Exley, James Fair, Kensho Goto, Shane Gross, Jo Haley, Tony Heald, Ben Hoare, Melissa Hobson, Jon A Juárez, Cate Langmuir, Florian Ledoux, Will Newton, Jenny Price, Jo Price, Andy Rouse, Peter David Scott, Richard Smyth, Wanda Sowry, Kenny Taylor, Lillian Todd-Jones, Nick Upton, Leoma Williams

Our Media, Eagle House, Bristol BS1 4ST, UK wildlifemagazine@ourmedia.co.uk bbcwildlife@ourmediashop.com

@wildlifemagazine

@WildlifeMag

@bbcwildlifemagazine

discoverwildlife.com bit.ly/bbcwildlifeyoutube

advertising

client solutions manager Dan Baker 0117 300 8280 dan.baker@ourmedia.co.uk

ad manager Sophie Keenan 0117 300 8804 sophie.keenan@ourmedia.co.uk

commercial brand manager Samantha Hurter-Wall 0117 300 8815 samantha.hurter-wall@ourmedia.co.uk

brand sales executive Anthony Jago 0117 300 8543 anthony.jago@ourmedia.co.uk

brand sales executive Marc Hay 0117 300 8758 marc.hay@ourmedia.co.uk

inserts Laurence Robertson 00353 876 902208 laurence.robertson@ourmedia.co.uk

licensing and syndication

senior paralegal Emma Brunt 0117 300 8979 emma.brunt@ourmedia.co.uk

director of licensing and syndication Tim Hudson

Our media ltd

CEO Andy Marshall managing director Andrew Davies brand lead Daniel Bennett

head of brand marketing Rosa Sherwood

marketing subscriptions director Jacky Perales-Morris

senior direct marketing manager Aimee Rhymer

subscriptions Marketing Manager Chris Rackley

production

production Director Sarah Powell

deputy production manager Emily Mounter

senior ad co-ordinator Charles Thurlow ad designer Parvin Sepehr

bbc studios, uk publishing chair, editorial review boards Nicholas Brett md, consumer products & licensing Stephen Davies

director, magazines and consumer products Mandy Thwaites compliance manager Cameron McEwan uk.publishing@bbc.com

bbc editorial review board

Alasdair Cross producer, bbc audio Rosemary Edwards executive producer, bbc natural history unit Sue Kent independent consultant

Jane Lomas series editor, countryfile Camila Ruz Renjifo digital producer, bbc natural history unit

photography and ethics

BBC Wildlife champions ethical wildlife photography that prioritises the welfare of animals and the environment. It is committed to the faithful representation of nature, free from excessive digital manipulation, and complete honesty in captioning. Photographers, please support us by disclosing all information about the circumstances under which your pictures were taken (including, but not restricted to, use of bait, captive or habituated animals). BBC Wildlife provides trusted, independent travel advice and information that has been gathered without fear or favour. We aim to provide options that cover a range of budgets and reveal the positive and negative points of the locations we visit. The views expressed in BBC Wildlife are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the magazine or its publisher. The publisher, editor and authors accept no responsibility in respect of any products, goods or services that may be advertised or referred to in this issue or for any errors, omissions, mis-statements or mistakes in any such advertisements or references.

Our Media Ltd is working to ensure that all of its paper comes from well-managed, FSC®-certified forests and other controlled sources. This magazine is printed on Forest Stewardship Council® (FSC®) certified paper. This magazine can be recycled, for use in newspapers and packaging. Please remove any gifts, samples or wrapping and dispose of them at your local collection point.

BBC Wildlife (ISSN 0265-3656 USPS XXXXX) is published monthly with an extra copy in June by Our Media Ltd, Eagle House, Bristol, BS1 4ST United Kingdom. Airfreight and mailing in the USA by World Container Inc., c/o BBT 150-15 183rd St, Jamaica, NY 11413-4037, USA. Periodicals postage paid at Brooklyn, NY 11256.

POSTMASTER: Send address changes to BBC Wildlife, World Container Inc., c/o BBT 150-15, 183rd St, Jamaica, NY 11431, USA. All rights reserved. No part of BBC Wildlife may be reproduced in any form or by any means, either wholly or in part, without prior written permission from the publisher. Not

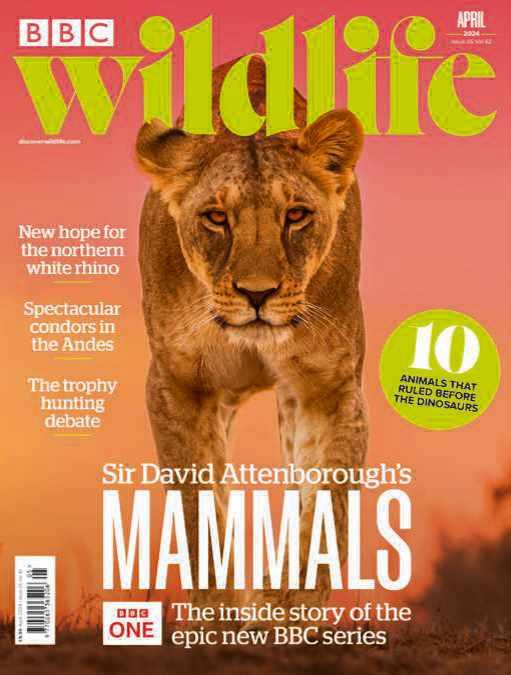

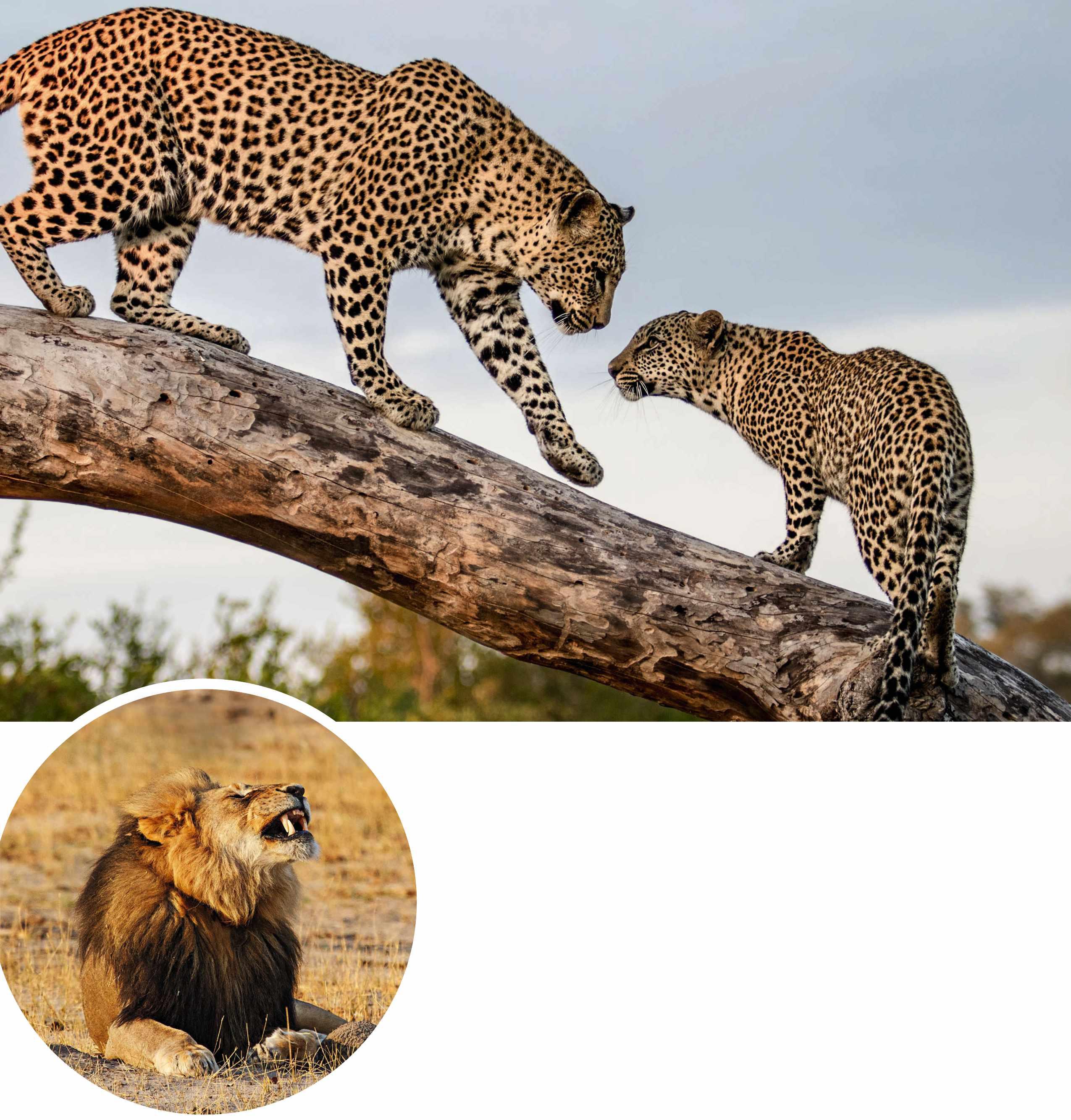

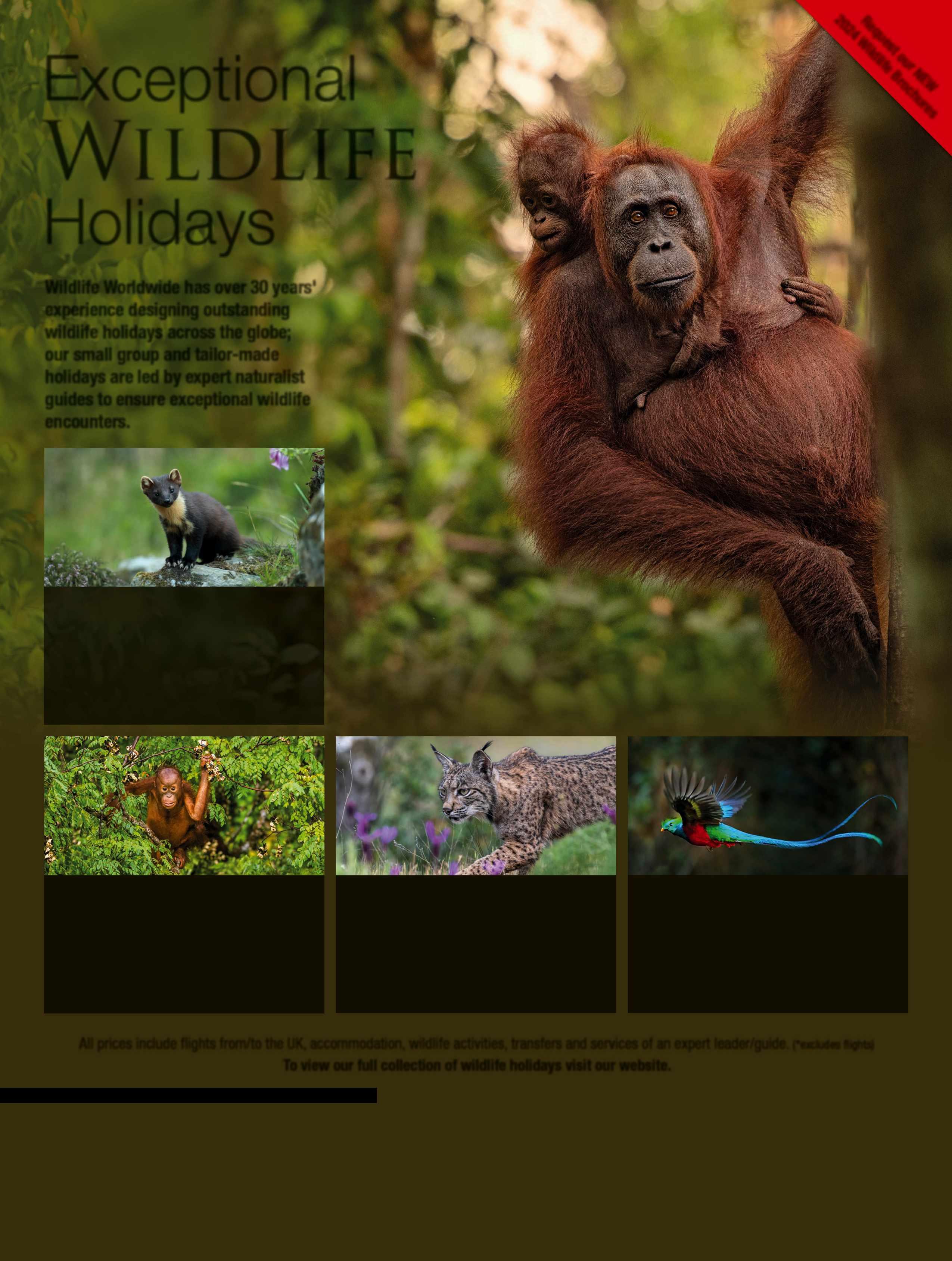

Lions are one of the many species that star in the brandnew BBC One series, Mammals, airing this spring. The Forest episode features a pride in Uganda that have learnt how to stay cool by climbing into euphorbia trees. “Mammals are the most adaptable and – for my money – adorable animals on earth,” says head of commissioning Jack Bootle. A new series is coming to BBC One...

“The

GILLIAN BURKE

“Surely

MARK CARWARDINE

Unfortunately, we’re unable to feature a column from Mark this month, but look out for him in a future issue

08 Wild Times

Catch up with all the latest developments and discoveries making the headlines

30 Spectacular condors in the Andes

Mike Dilger offers his top tips for observing these masterful vultures effortlessly soaring

34 Hidden World

A clever adaptation allows water anole lizards to stay submerged and out of danger

38 Mammals

Series producer Scott Alexander shares behind-the-scenes tales from the new BBC One show

46 New hope for the northern white rhino IVF is providing one last chance to save this incredibly rare subspecies from extinction

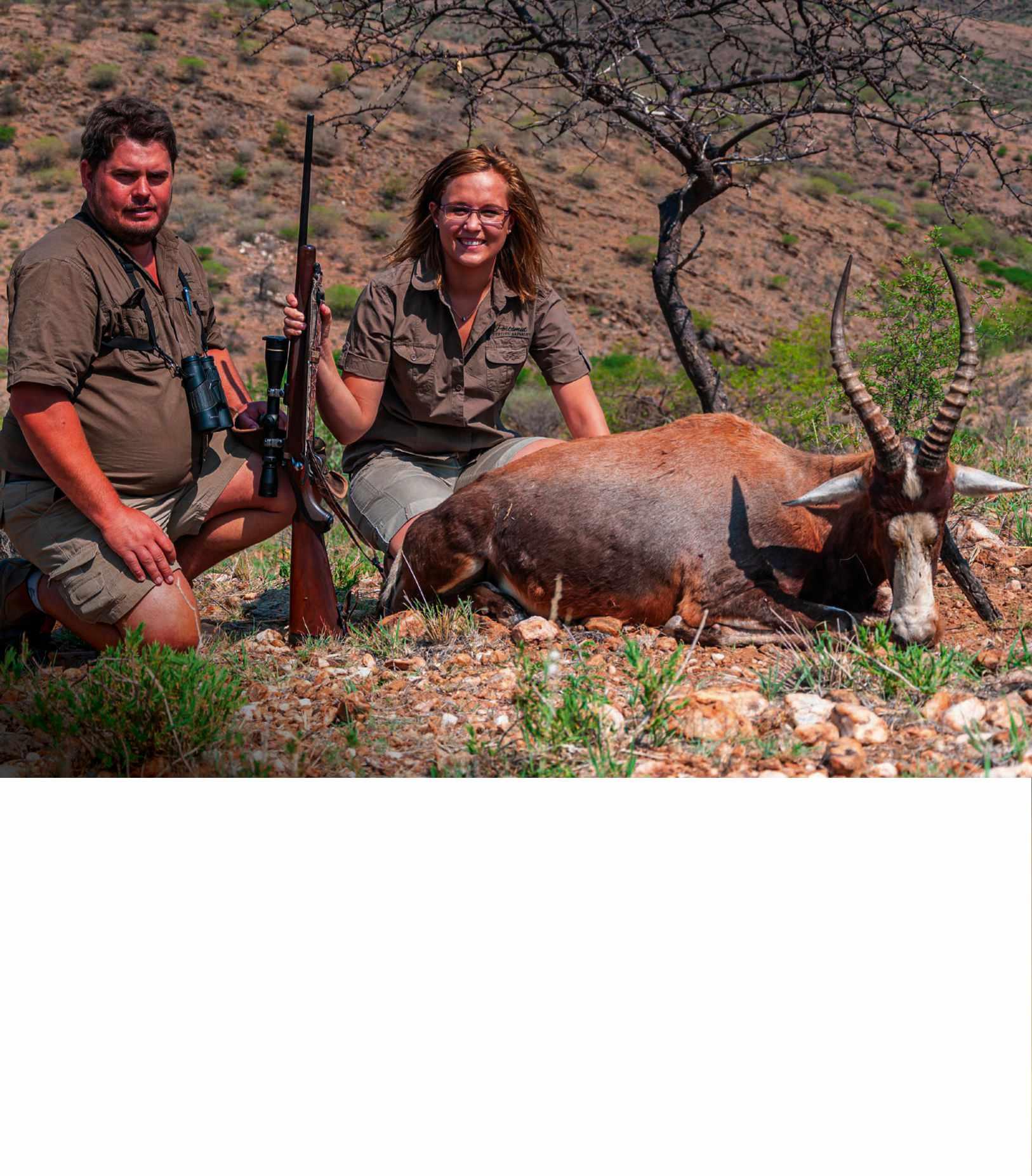

56 The trophy hunting debate

Does allowing wealthy tourists to kill wild animals actually help conservation?

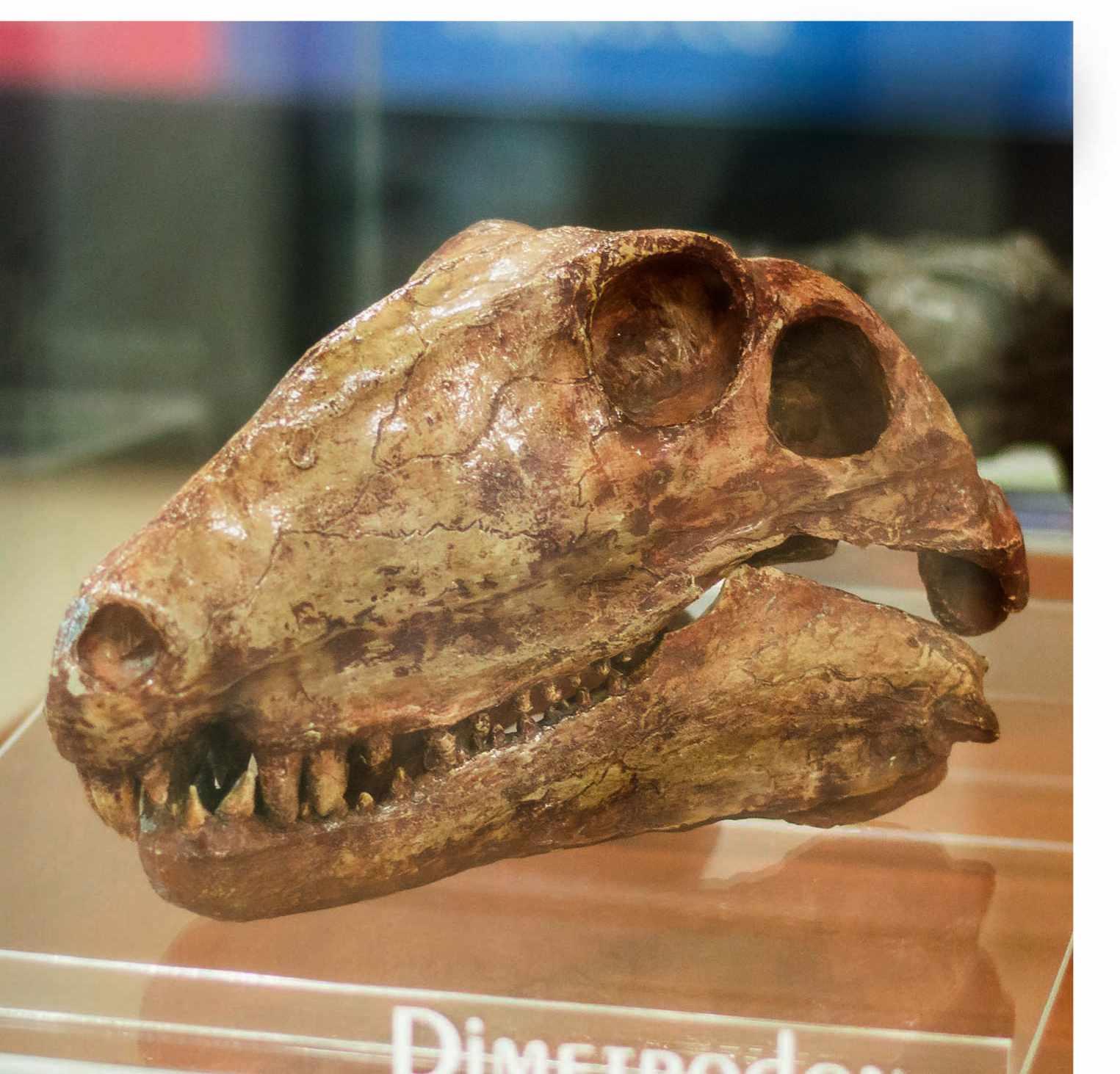

64 10 animals that ruled before the dinosaurs

From super-sized millipedes to fish that could walk on land

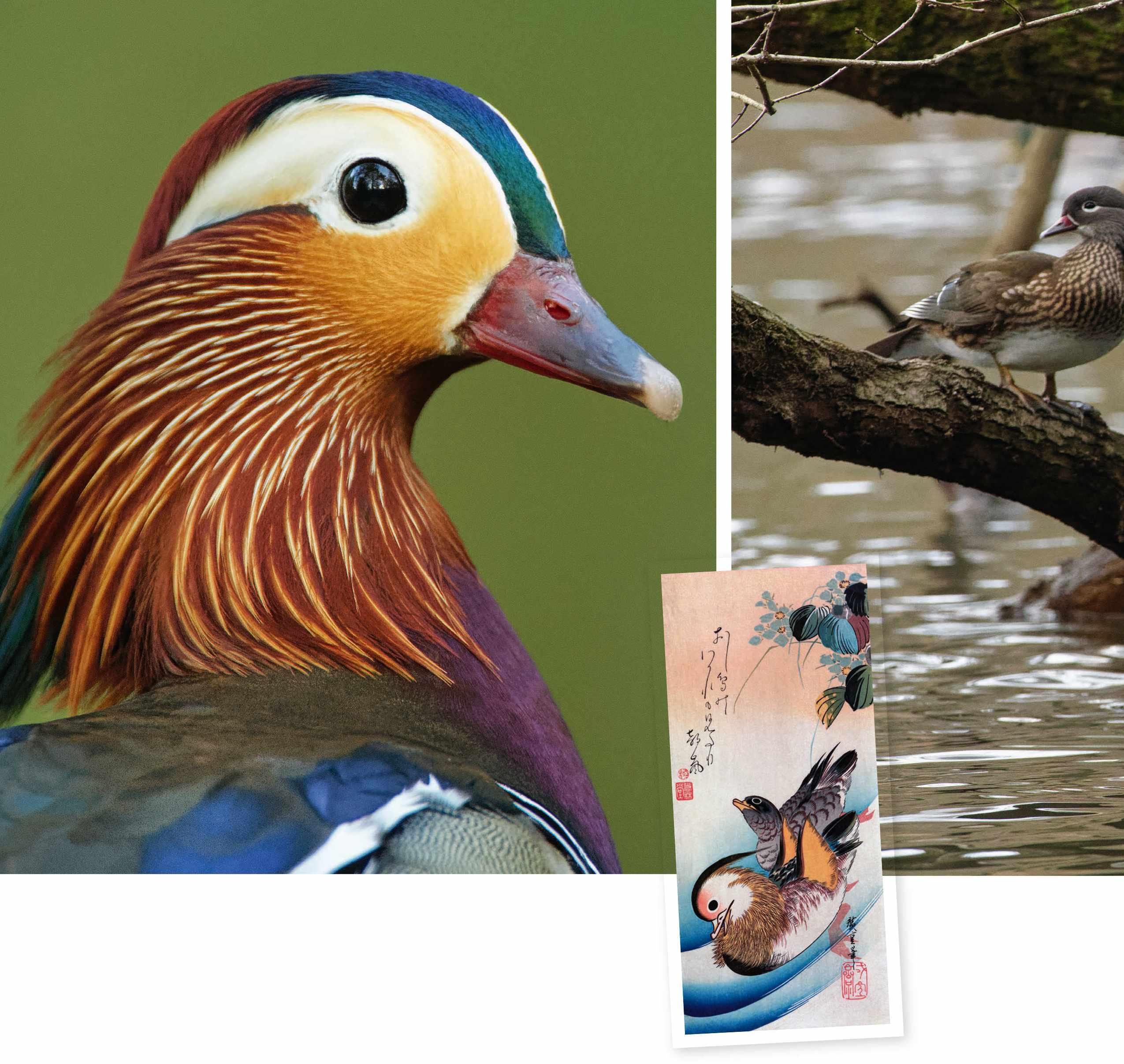

72 Mandarin magic

A glimpse into the secret life of the mandarin duck – a shy but beautiful bird that has made itself at home in the UK

GET A WIGGLE ON

Highly Commended in the Wide Angle category of Underwater Photographer of the Year 2024, this compelling image transports the viewer into a magical underwater world as millions of western toad tadpoles swim upwards to the lake shallows to feed on algae among the lilypads.

Seventy-odd kilos of irritated bristly boar is not to be messed with. Mature wild boar sows have young in tow in April and are super-protective of their boarlets, so if you’re lucky enough to glimpse these muscular, tusked pigs in a spring woodland, give them a wide berth. The stripy piglets are fondly nicknamed ‘humbugs’ for their resemblance to the mint-flavoured sweets. There may be five or six of them in a litter, but several sows and their piglets often join forces, forming a larger group called a sounder. By contrast, the big adult male boars, which can be twice as heavy as sows, are loners.

One estimate suggests there are 2,600 boar at large in Britain, with a stronghold in Gloucestershire’s Forest of Dean. Chantal Lyons, in her brilliant new book Groundbreakers, acknowledges boar can be difficult to live with, but sings their praises as piggy rewilders. The boar create a healthy mosaic of woodland habitats by turning over the earth and breaking the dominance of bracken, nettles and brambles, allowing a wider variety of plants and invertebrate life to flourish.

Ben Hoare

IF you enjoyed last year’s Wild Isles, the six-part series for BBC One presented by Sir David Attenborough that showcased the best of Britain’s wildlife, here’s your chance to hear more about the natural history extravaganza – in person. At this big-screen talk, veteran producer Alastair Fothergill discusses highlights from the series, shows never-before-seen footage and shares his behind-the-scenes stories. He promises to take the audience on a captivating journey through the most breathtaking landscapes of the UK, from the peaks of the Scottish Highlands down into the woodland undergrowth, showcasing the myriad species that call such places home. “Nature in these islands, if you know where to look, can be extraordinary, dramatic and beautiful,” reminds Sir David in his voiceover. “It rivals anything I’ve seen elsewhere. It’s not far; it’s home.”

The tour starts on 10th May in Basingstoke, following in venues in Bristol, Edinburgh, Birmingham, London (Royal Festival Hall) and Brighton. Tickets start at £21.80, book at wildisleslive.org.

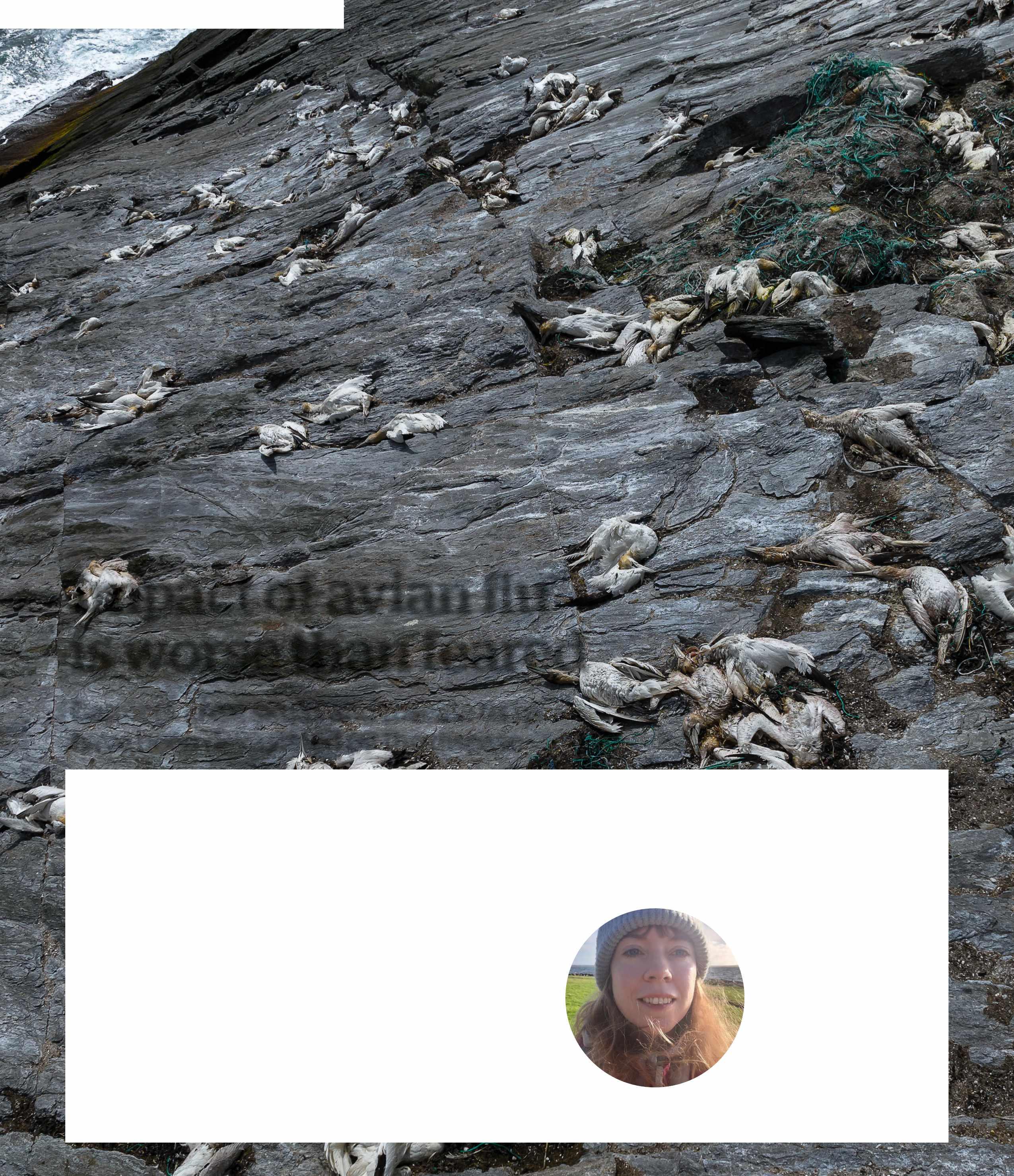

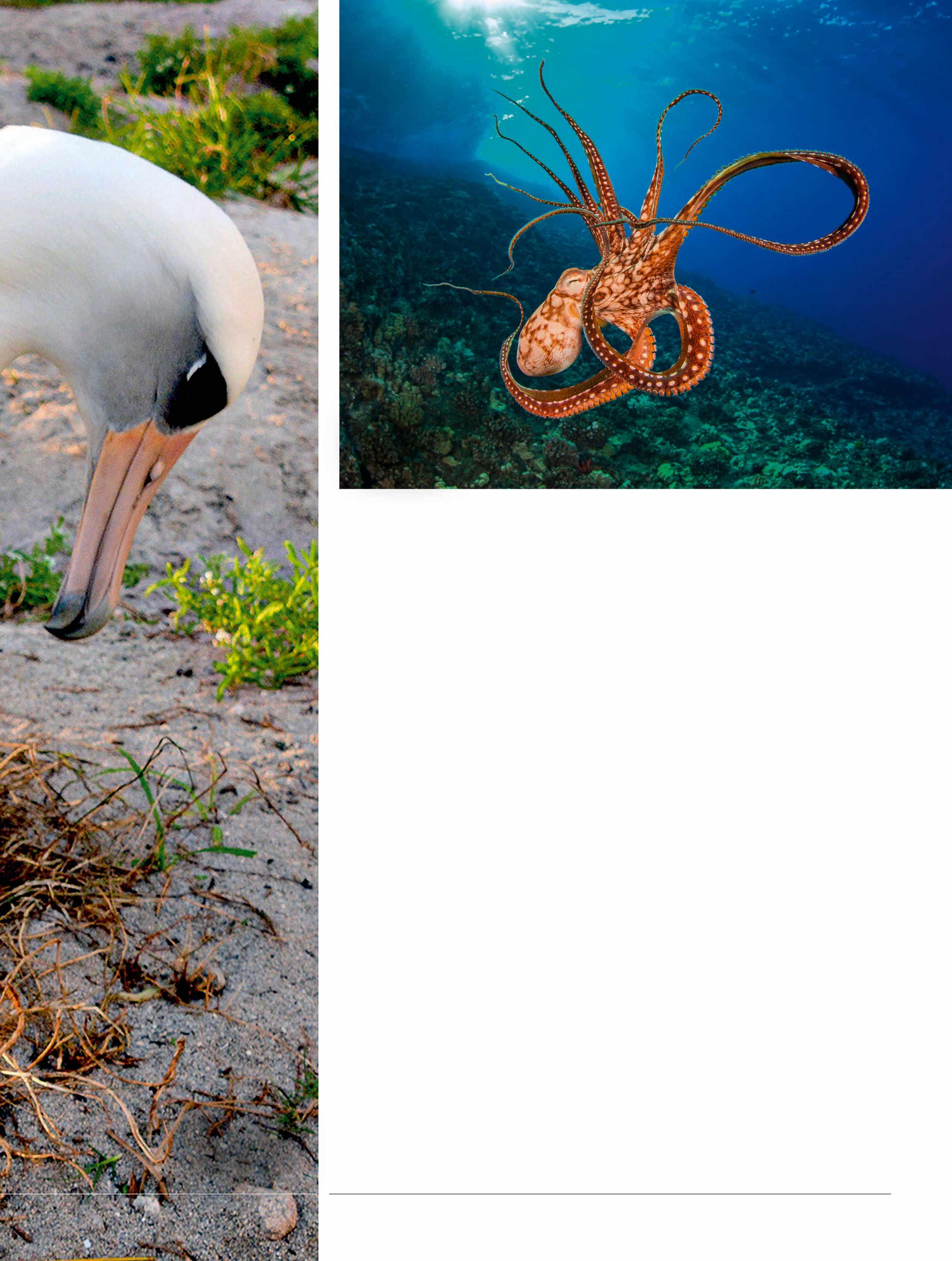

Sarah McPhersonGannets, great skuas and roseate terns have been devastated by the disease

Anew report by the rspb, bto and other conservation organisations has revealed the true impact of avian flu on the UK’s globally important populations of seabirds.

According to the study, the great skua was particularly badly hit, with more than three quarters of the UK population lost. At least 2,500 birds were reported dead across Scotland, which is home to 60 per cent of the world population.

The gannet has also been severely impacted, with a 25 per cent drop in numbers across the UK, which supports more than half of the world’s birds. At least 11,000 deaths were recorded in Scotland, and there was a 54 per cent collapse in

the Welsh population – 5,000 deaths were recorded on the RSPB island reserve of Grassholm alone. Gannets breed in a small number of densely packed colonies, making them particularly vulnerable to the spread of the disease.

The report also revealed a 21 per cent decline in the UK population of roseate terns, our rarest breeding seabird.

“The findings are extremely worrying, confirming avian flu to be a major additional threat to our already struggling seabirds,” says Jean Duggan, policy assistant on avian flu at the RSPB. “We knew the situation was bad for gannets and great skuas in

particular, but it’s worse than we thought.”

In other news, the long-term future of the UK’s threatened seabirds – including gannets and great skuas – is looking more hopeful following the ban on industrial sandeel fishing in the English North Sea and all Scottish waters. The move represents a significant victory for environmental groups, which have been campaigning for a ban for decades.

Jean Duggan“The closure of sandeel fisheries will be a vital lifeline for our seabirds,” says Duggan. “Now we need to build on this with further action to increase resilience and safeguard their future.”

Simon Birch

The cooperation of communites was critical to new observations of rare river turtle in tropical India

Agroup of biologists has discovered a breeding population of extremely rare Cantor’s giant softshell turtles (Pelochelys cantorii) on the banks of the Chandragiri River in India’s tropical south-west. It’s the first time this secretive species has been recorded nesting, according to a study published in the journal Oryx. With data on the species’ ecology, behaviour and population size limited, the finding – which relied heavily on community knowledge – represents an important breakthrough for conservationists.

Cantor’s giant softshell turtle, also known as the ‘frog-faced softshell’ due to its amphibian-like facial features, is a large species of freshwater turtle with a broad head, small eyes and a pointed snout. Despite its wide distribution across much of southern Asia, the species, which can exceed more than one metre in length and weigh more than 100kg, is in decline and classified as Critically Endangered on the IUCN’s Red List of Threatened Species. Habitat destruction is the main cause of the population drop, though the turtles are also harvested for meat and are often killed when they become caught in fishing gear.

The quest to uncover the whereabouts of the softshell took a team of researchers to the south-west Indian state of Kerala. By talking to people from local communities, the scientists were able to locate the turtles on the banks of the Chandragiri River and begin to record their observations. Their research led to the first documentation of a nesting female.

“Through household interviews and the establishment of a local alert network, we did not just listen; we learned,” says Ayushi Jain, co-author of the paper. “The community’s willingness to engage formed the backbone of our project, allowing us to record not just fleeting glimpses of the turtles but evidence of a reproductive population – a discovery that rewrites the narrative of a species thought to be vanishing from India’s waters.”

The paper highlights the vital role of local knowledge in conservation, and suggests that the creation of an alert network, where community involvement offers not only expert knowledge and insight, but also immediate action, will pave the way for a more responsive and inclusive model of wildlife conservation in Kerala.

Danny Graham

Hooves are the hardened tips of the toes found in many a large herbivore. A cloven hoof is one that appears to have been cleaved in two – think of the print left by a cow or deer. The earliest common ancestor of ungulates would have had five toes on each foot, but some of these have been lost during the course of evolution. Cloven hooves correspond to the third and fourth of these ancestral digits.

Stuart Blackman

It’s a little over 400 years since the first horse chestnut trees were brought to the British Isles from their native home in the mountains of Greece. You only have to look at these handsome trees covered in pinkish-white blossom to appreciate why the owners of grand houses were so desperate to include them in their gardens and deer parks. Horse chestnuts can now claim to be some of the tallest flowering plants in the country, and the individual flower spikes, known romantically as candles, are themselves huge, measuring up to 20cm tall.

These rather magnificent flowers, which burst into bloom in April and May, are rich in both nectar and pollen. Look closely and you’ll notice the petals sport bright yellow streaks, known as nectar guides, which, as their name suggests, show bees where the goodies lie. Once pollinated, the nectar guides turn deep red to indicate that this particular flower is ‘spent’ and no longer worth visiting. Ben Hoare

Discover world-class birding along the longest river in Africa, where intricate ecosystems are flanked by archaeological treasures

Famous ruins, towering monuments and aweinspiring pyramids – a trip to Egypt is unforgettable, in part because of its immense cultural offering. But alongside the remnants of an iconic ancient civilisation, Egypt is home to some unique habitats and an astounding variety of birdlife, especially along the banks of its magnificent river, the Nile.

What better way to explore the ecological (and historical) riches on offer than joining an intimate river cruise with Aggressor Adventures? Luxury rooms, fivestar service and expert guides,

as well as breathtaking views and exceptional birdwatching opportunities, make for a travel experience like no other. Plus, the subtropical desert climate makes Egypt a great destination for some winter sun.

Beginning in Luxor on the east bank of the Nile, home to several ancient sites including Amun Temple and the Valley of the Kings, the Aggressor Nile Queen II embarks on its six-day voyage. First up, you’ll explore King Island — one of the area’s premier wetland sites — on the boat’s nine-metre floating bird hide. Look out for various

wetland species, such as the little egret, cattle egret and purple heron, as well as kingfishers and raptors.

The adventure unravels at a leisurely pace – each day you cruise down the river and visit different birding hotspots along the way. Travelling southwards to Aswan, the ship sails by several historical wonders, including Gebel Silsila quarry and Kom Ombo, and many important nesting sites for native and migratory birds. Keep an eye out for some of the region’s colourful residents, like the Nile Valley sunbird and the red avadavat.

With only 20 passengers aboard each charter, the Aggressor Nile River Cruise offers a truly

personalised experience with five-star service all-round. After a day’s sightseeing, watch the world go by from the hot tub on the sundeck, or retreat to your deluxe room with a private bathroom and tiled walk-in shower. Enjoy fantastic chef-prepared meals and complimentary beer and wine while you mingle with likeminded people, or simply watch the Saharan sunset change the colours of the sky. This is slow travel at its best.

Call +1 706-993-2531, message info@aggressor.com or visit aggressor.com for more information.

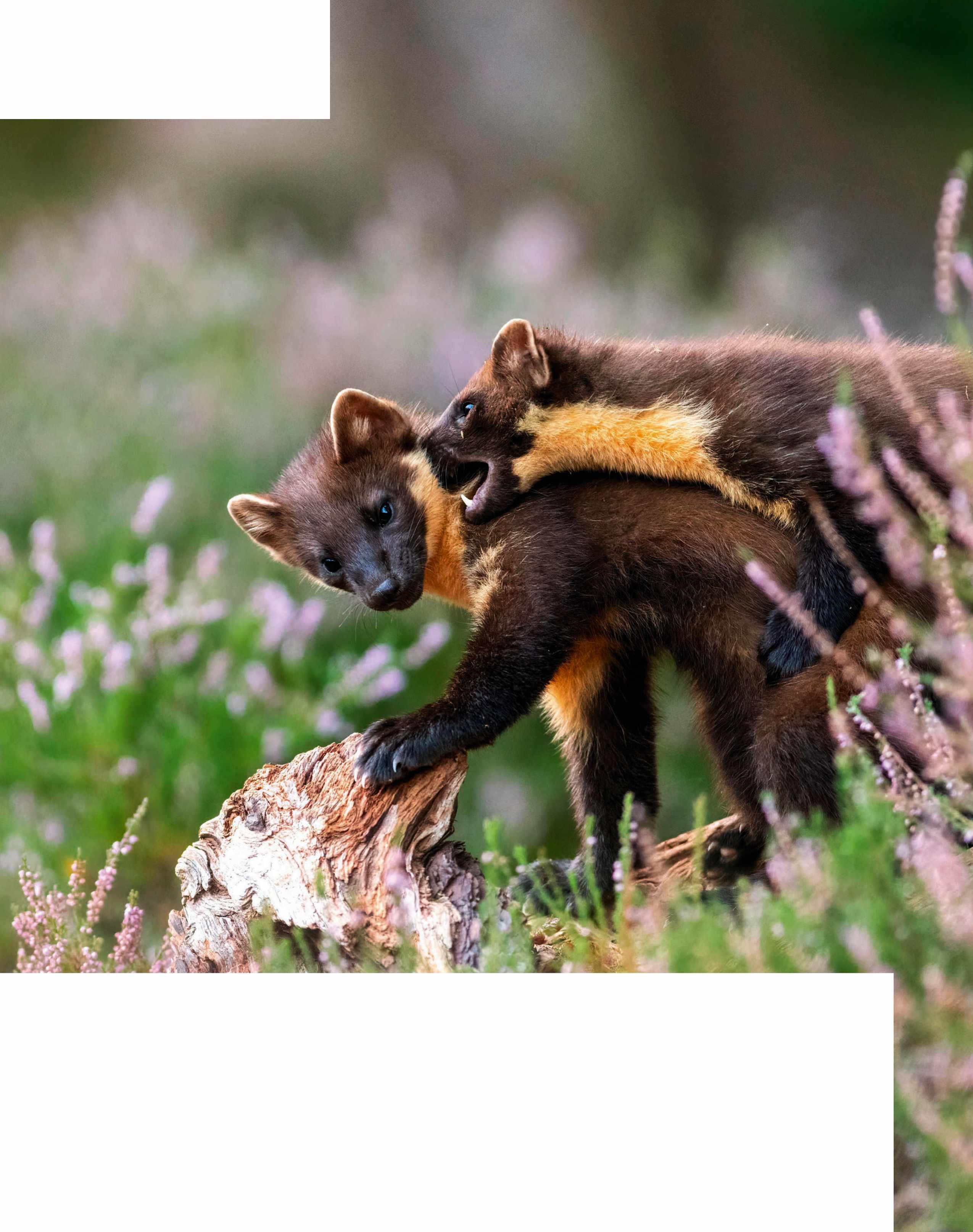

Pine martens give birth in spring, usually to two or three kits. The helpless young stay hidden in mum’s tree-hole den until May or June. For too long, these elusive mammals have clung to a fraction of their former range in Scotland, northern England and Wales, but reintroduction projects may soon return them to south-west and south-east England. Ben Hoare

First identified in 2017 by a group of Star Wars-loving scientists, the Skywalker hoolock gibbon was known only to exist in China, with fewer than 200 individuals. While experts suspected the distribution of the arboreal primate extended into Myanmar, a complex history of civil ethnic conflict in the country made it impossible to verify this theory. Now, new research published in the International Journal of Primatology proves that the species’ range does indeed spread into the South-East Asian nation.

Between December 2021 and March 2023, a field team, led by Fauna & Flora International and Nature Conservation Society Myanmar, undertook expeditions to six sites in Myanmar’s Kachin State and three sites in Shan State to determine the presence of Skywalker gibbons. The study involved the use of acoustic monitoring systems, which were set up at the sites. Each morning, the researchers listened to the Skywalker gibbons’ loud vocal displays to identify their locations.

The team also collected samples of plants and fruits discarded by the gibbons and analysed the material in a DNA/ RNA Shield. This non-invasive DNA-sampling technique enabled

the researchers to confirm 44 new groups of Skywalker gibbon in Myanmar. The exact number of individuals is unknown.

Ngwe Lwin, who led the expedition, says that the confirmation of Skywalker gibbons is “a significant discovery for the future of primate conservation in Myanmar,” whilst conceding that “while there are now more confirmed groups of Skywalker gibbons in the wild, it is feared that their populations are fast declining due to habitat degradation and loss, and poaching”.

Currently, just 4 per cent of Myanmar’s existing protected areas offers suitable habitat for Skywalker gibbons. The paper recommends combining governmentorganised protection with community protected areas. Two communities have already shown an interest in establishing protected areas, with one willing to start an awareness programme to prevent hunting of the endangered primate.

“Now more than ever, it is recognised that the collective efforts of stakeholders – including governments, communities and indigenous peoples’ groups – are the only effective way to protect and save our closest living relatives,” says Lwin.

Danny Graham

Scientists are uncovering the mysteries of deep coral reefs with underwater drones and eDNA

Researchers are using underwater drones to learn about mysterious mesophotic coral ecosystems (MCEs) – low-light habitats in tropical and subtropical regions made up of coral, sponges and algae. Because MCEs are found at depths of 30-150m, which is beyond recreational scuba-diving limits, they are very hard to study. So, Noriyuki Satoh and his team at Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology and NTT Communications in Japan have trialled the use of underwater drones to collect seawater samples and analyse their environmental DNA (eDNA). The aim is to find out which types of stony coral are present.

As organisms shed cells, mucus or faeces, they leave traces of eDNA behind. By analysing these, scientists can identify what creatures are present, even if they haven’t observed

them. eDNa is already used to study marine animals in shallow coral reefs.

The researchers collected samples at 24 sites in the Okinawa Archipelago – a region known for its clear waters and diversity of stony corals. Initial findings have identified coral at genus level and shown that the reef composition varies according to depth. Acropora corals, for instance, were more common in shallower reefs; Porites were more common in the MCEs.

Satoh hopes the use of underwater drones will help researchers learn more about MCEs. These reefs are home to a higher proportion of endemic species than their shallow counterparts, so knowing how they function is vital to keep the ocean healthy.

WHAT IS IT?

This plump, innocent-looking character is a new species of burrowing frog. Up to about 4cm in length, it can be distinguished from other members of its genus by its liver-spotted skin dotted with raised orange pimples.

WHERE IS IT?

So far, it is known from a few suburban sites around the Indian city of Bengaluru, where it seems to be active above ground only during the monsoon season. Males have been heard calling during torrential rain, but go quiet between showers. With no permanent water bodies in its habitat, it breeds in temporary muddy puddles.

WHAT’S THE MEANING BEHIND THE SCIENTIFIC NAME?

The genus, Sphaerotheca, derives from the Greek for ‘spherical box’, while varshaabhu is a Sanskrit name meaning ‘rain birth’, a reference to the species’ monsoon breeding season.

Find out more mapress.com/zt/article/ view/zootaxa.5405.3.3

Melissa Hobson

Melissa Hobson

Koki Nishitsuji, Haruhi Narisoko and Noriyuki Satoh

A grey seal colony has established itself at a former military testing site used during both world wars and into the Cold War. More than 130 seal pups have been born at Orford Ness in Suffolk this breeding season. Rangers say that the site, now owned by the National Trust, has been used as a breeding ground since 2021 and hope the numbers will continue to rise.

The idea of humans as an interplanetary species has been gaining momentum for the past few decades. Admittedly, I’m a little late to the party as I only first heard the term last year in an interview with the billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk, who revealed his deep concern that our species is extremely vulnerable because we are currently limited to one planet.

My first thought was here’s someone who clearly doesn’t have enough to worry about. But Musk is not alone. The World Economic Forum has set out why humans must become an interplanetary species, while other scientists, including the late Stephen Hawking, have been advocating for going interstellar (because why stop at our solar system, I suppose?).

My gut reaction is surely extracting ourselves from the beautifully complex web of life to create a viable, healthy interstellar population isn’t really possible? It’s just a hunch, but I reckon the gut is a good place to start. The human gut-microbiome is home to 100 trillion bacteria, archaea, fungi, protozoa and viruses, and is just one of many microbial habitats on and inside our bodies.

Every one of us is like a walking planet with a multitude of ecological niches. These are home to microbes whose essential services we employ to help train our immune systems, digest our food, and regulate our energy levels and brain function, even including our moods.

Kick-starter microbial communities are acquired from our mothers at birth and evolve, diversify or shrink, according to life experience and environmental factors, to create a bespoke microbial signature for every individual. It’s thought that these microbial associations have been working their way down the maternal hominid line for more than 15 million years, which makes for an epic research and development phase that will be hard to beat if we were to up sticks and move to a foreign planet.

The role of microbiomes in humans and other animals (wood mice, giant pandas, bison and even common rock barnacles) is a new frontier of science, and so has been the subject of extensive research. But the sober irony is much of it is gleaned from gnotobiotic, or ‘germ-free’, lab animals who, by virtue of being artificially stripped of their microbial ‘helpers’, have extremely poor health outcomes and short lifespans.

Recognising that there will be a need to take our microbial compatriots with us,

Gillian Burke is a biologist, writer, film-maker, TV presenter and podcaster. She joined the BBC Two Watches team in 2017.

Catch up with all four episodes of Winterwatch on iPlayer

Maybe we need to look around us before we launch into space

“Is creating an interstellar human population really possible?”

NASA scientists have been studying baby bobtail squid on the International Space Station to observe how the effects of zerogravity, radiation exposure and other factors affect their microbiomes.

Meanwhile, back on earth, microbial communities underpin life as we know it, as photosynthesising plants feed exudates through their roots to microbes in the soil. A production line of bacteria, fungi, protozoa, nematodes and microarthropods convert inorganic minerals into essential nutrients that are re-absorbed by the plant and handed up the food chain, eventually nourishing us.

Setting aside ‘could we?’ for a moment, let’s ask, should we? I’m not against striving to boldly go where no human has gone before, but I am more in favour of addressing the existential threats that have prompted at least some scientists to think about launching a lifeboat into space.

The primary “global terminal risks”, as identified by the Future of Humanity Institute, are “nuclear holocaust, genetically engineered mistakes, destructive nanobots and even the gradual loss of human fertility”. All are entirely manufactured, so within our power to do something about.

A new genetic study finds that blue whales are mating with fin whales and producing fertile young

An examination of blue whale genetics has revealed that the world’s largest animals have been breeding with fin whales. During a study published in Conservation Genetics, researchers analysed the genomes of the North Atlantic blue whale subspecies – a group still in recovery following extensive whaling in the past – and discovered relatively high levels of fin whale DNA.

Though it has been known that the two species could create hybrids, often called ‘flue’ whales, it was only recently found that these hybrids were fertile. By mating with blue whales, fin whale DNA is introduced into the blue whale population, a process known as introgression.

Strangely, this introgression only seems to be going one way, from fin whales to blue whales, as the hybrids don’t appear to be mating with fin whales. “We don’t know why

introgression appears unidirectional,” says Mark Engstrom, co-author of the study, “but it may be related to reproductive behaviour and mating activities of the two species, and also possibly to the much larger numbers of fin whale individuals (and in this case specifically males) compared to the smaller population size of blues.” Engstrom adds that this hybridisation and introgression is not currently a cause for alarm but should be monitored going forward.

“As well as concerns that an endangered species could become extinct, there is also the associated issue of one species being highly protected and the other not,” says Danny Groves, head of communications at Whale and Dolphin Conservation in the UK. “The whale hunts in Iceland have led to hybrid blue and fin whales being killed.” Megan Shersby

Mark

Engstrom,co-author of the study

Lobsters pee out of their faces via special openings called nephrophores at the base of their antennae. The urine contains pheromones that allow lobsters to communicate with one another. Males pee to defend their caves, while females pee to indicate their

Dandelions enjoy their moment in the sun each spring, turning roundabouts, roadsides, lawns and any other scraps of grass that have been spared mowers and chemical sprays into a sea of yellow. Don’t dismiss these humble yet prolific ‘weeds’. They produce more nectar and pollen than most other wildflowers and are brilliant for bumblebees, solitary bees and hoverflies. Ben Hoare

Welfare of primates set to improve as private keepers in England will soon require a licence

Following years of campaigning by the RSPCA, legislation introduced recently by the government will mean tighter future controls on the domestic keeping of primates. There are up to 5,000 pet primates in the UK, the most common being marmoset monkeys, which typify why primates make unsuitable pets. Marmosets are intelligent, social and long-lived creatures, more suited to group life, roaming free and eating a varied diet in South American forests. They also scentmark, spreading a musky aroma not welcome in a human home. A marmoset kept alone,

eating a limited diet in a small domestic space can suffer severe stress and other health problems. RSPCA inspectors regularly report seeing pet primates with behaviour problems and poor health, especially metabolic bone disease (rickets in humans) due to inappropriate care.

From April 2026, all private primate keepers in England will need to be licensed through their local authority, subject to an inspection of Ros Clubb, RSPCA head of wildlife

FROM THE BBC WILDLIFE ARCHIVE June 1983

animals and premises to assess welfare standards. Licensees will need at least one further inspection during a three-year period. If they fail to meet the same welfare standards found in zoos, they will face a fine or have the primate removed from their care. Effectively the legislation bans the practice of keeping primates as pets.

Acknowledging the government’s commitment to end domestic primate keeping, Ros Clubb, head of the RSPCA’s wildlife department, says she hopes this will “put an end to the shocking situations we have seen, with monkeys cooped up in birdcages, fed fast-food, sugary drinks and even class A drugs, deprived of companions of their own kind, living in squalor and suffering from disease.”

There is still a need, she adds, for ministers to set out how the welfare needs of monkeys will be met once the new law comes into force.

The Welsh government is now consulting on licensing private keepers.

Kenny TaylorSnail-watching was the subject of a five-page feature in the June 1983 issue of Wildlife. Curator of the Gilbert White Museum and keen conchologist June Chatfield covers all aspects of the lives of Britain’s 87 species of land snail, from their strange sexual habits to how they fix their shells. She even explains how to observe them feeding: “Bring home some snails and starve them overnight; then allow them to browse on a thin transparent plastic dish painted with a film of flour and water paste. You can see the rasping action of the radula and the rhythmic movement of the jaw through the bottom of the dish.”

ARCTIC TERN

By the end of May, these gorgeous birds will be nesting in Britain and can be seen fishing offshore

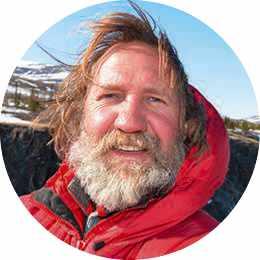

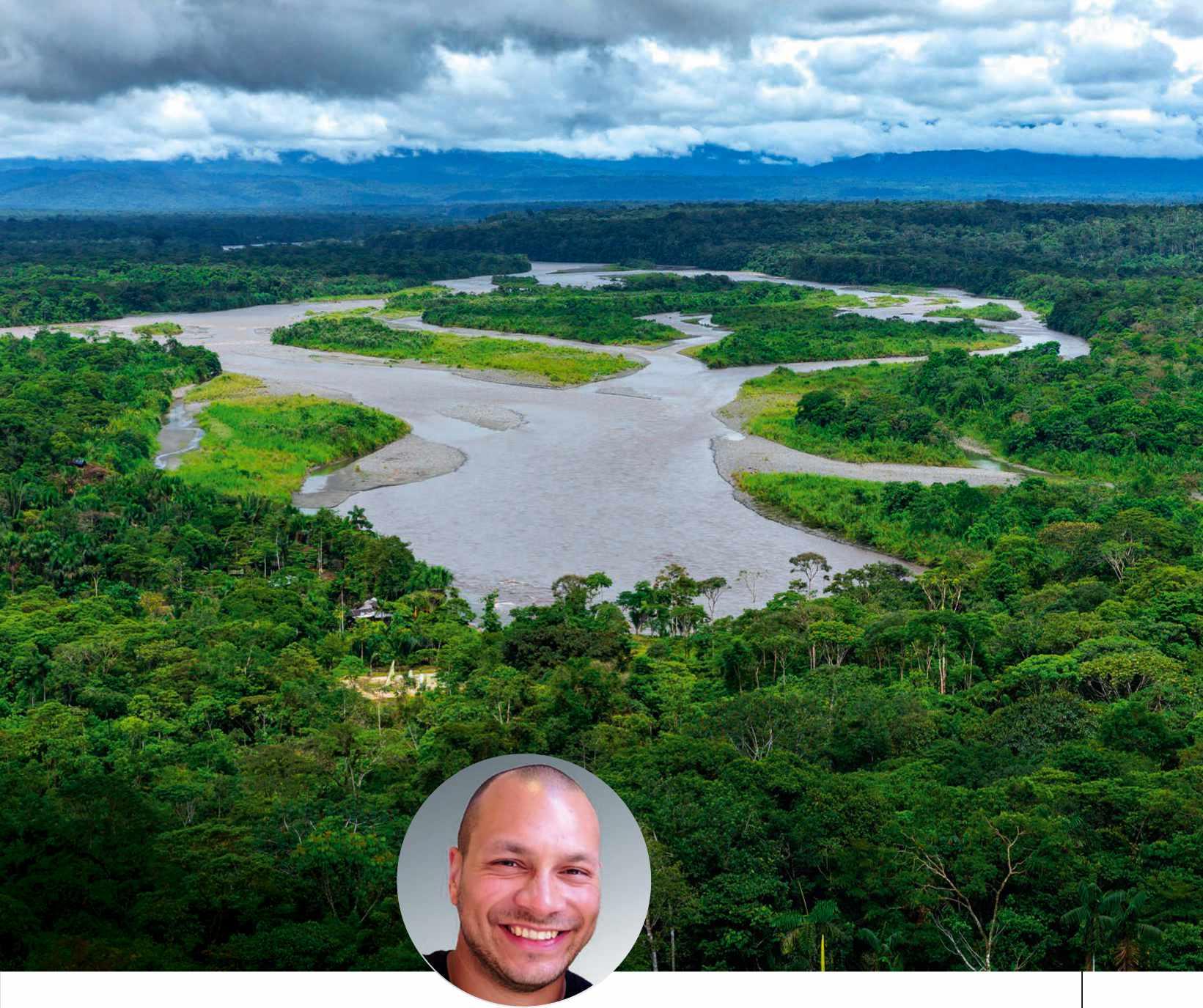

Join multi-award winning wildlife filmmaker Colin Stafford-Johnson on one of his personally guided tours to see some of the most amazing wildlife in the world on three very different journeys . Booking now for autumn 2024 and early 2025.

India Jungles and tigers

Botswana The Okavango Delta Guyana Rainforest, rivers and savannahs

For more information, drop Colin a line at adventureswithcolin@gmail.com or give him a call on +353 892032517

Your chance for a weekly adventure in nature and the countryside with the BBCCountryfileMagazineteam

You can find the Plodcast on all good podcast platforms

Our new podcast with top gardening guests

You can find Talking Gardens on Apple Podcasts, Google, Spotify, Acast and all good podcast providers. Subscribe so you never miss an episode.

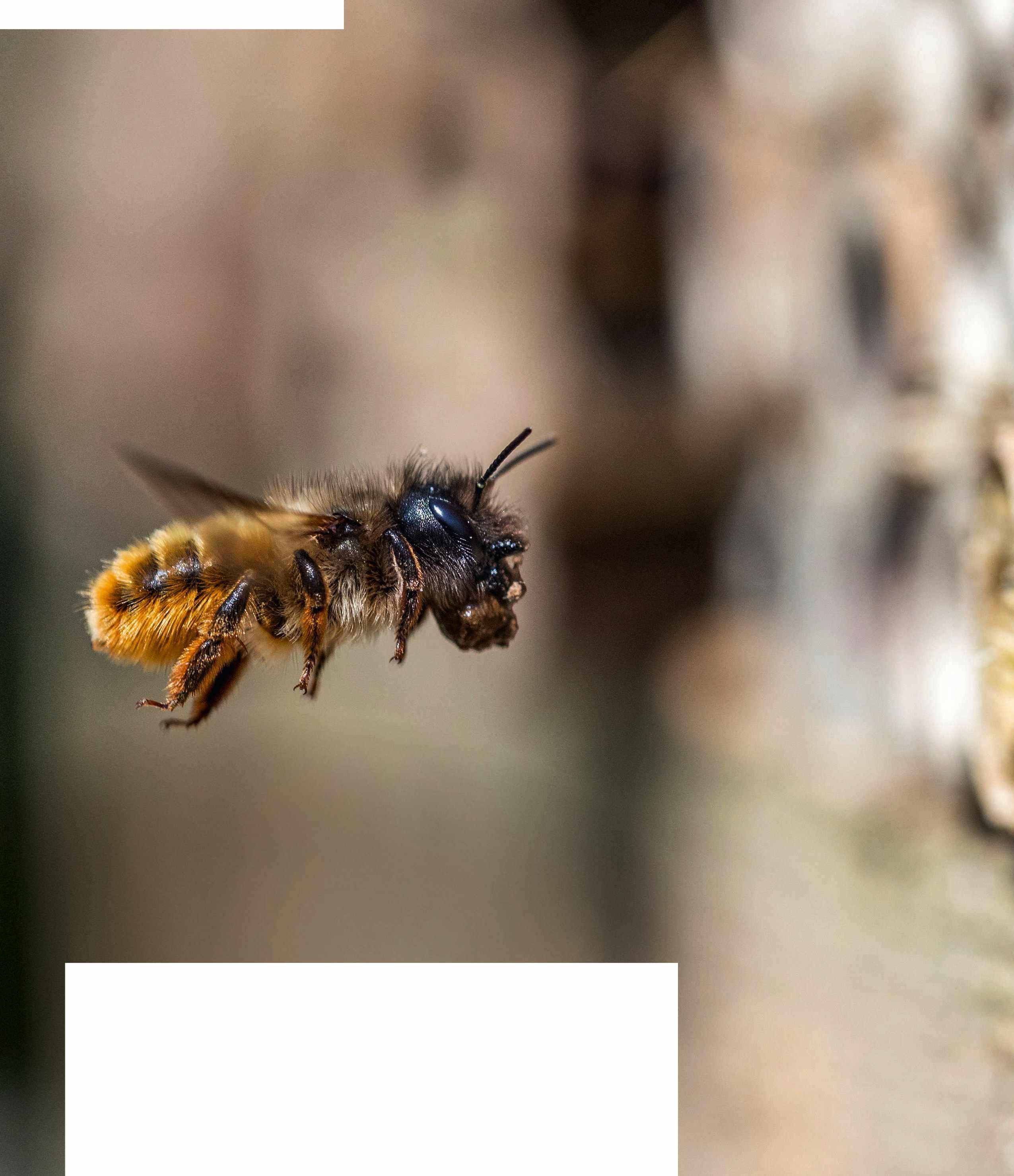

One bee to look out for this April is the red mason bee. It is common in towns and suburbia and resembles a small, gingery honeybee. The red mason is a kind of solitary bee, which means the female builds her own nest cells instead of living in a colony, like honeybees and bumblebees. In practice, that doesn’t mean she’s entirely on her own, since female red mason bees nest in loose groups. Their nesting requirements

are very precise: tube-like cavities around 7-8mm in diameter, normally in hollow plant stems or sandy banks.

It is easy to attract these beautiful bees to a garden or balcony simply by fixing cutdown bamboo canes to a south-facing wall – or buy a bee hotel. On sunny days in April, the female red mason bees will be emerging from hibernation and checking out suitable places to nest, so make sure you’re ready for them!

Ben HoareIn

While most North American mammal species are suffering declines, there is one species that bucks the trend quite dramatically, even in the face of intense persecution.

Coyotes are North America’s most oppressed animal – more than 400,000 are exterminated every year, 80,000 by the US federal government, which co-opts helicopters and snipers to shoot down this ‘pest’ species. Yet despite this lethal activity, numbers continue to rise.

Since the 1950s, these wily canids have increased their habitat by 40 per cent, more than any other North American carnivore. They can be found in every US state (apart from Hawaii) and from the far north of Alaska, they’ve even spread into Central America. A large part of their extraordinary success is a flexible approach to motherhood.

The coyote is a close relative of the wolf, albeit three times smaller – the average coyote weighs around the same as a standard Schnauzer. They are much hated by farmers, who claim they kill their livestock. The truth is these opportunistic eaters mostly subsist on far smaller prey such as rodents, rabbits and even reptiles. Coyotes are also not averse to plant matter and have even been known to climb trees to graze on berries.

A wide-ranging diet has certainly helped them colonise a variety of habitats, from deserts to prairies, mountains to cities. Coyotes also boast shrewd intelligence and high mobility – they can run at 64kph and cover large distances. But it is their family life that’s proved to be the real winner. Coyotes form monogamous pairs that mate for life. Their loyalty is such that death is the only reason a coyote will seek out a new

Catch up with Lucy’s three-part BBC Radio Four series, Political Animals

partner. The breeding pair hold alpha status in their family pack, which will hunt, den and range together. They can communicate using 11 known vocalisations – yips, howls, barks and grunts – that enable them to work as a team when bringing down bigger prey, such as deer, or defending their territory.

This cooperative lifestyle also extends to breeding. Coyotes reproduce just once a year and give birth in spring, producing an average litter of four to six pups. Though numbers vary according to location and food abundance, a litter of 19 was once recorded. When times are tough and resources low, young female coyotes delay reproduction and instead bide at home as helpers. These juvenile females babysit the alpha’s pups and help bring home food for their nursing mum. In areas of high resource availability, however, almost half will leave their natal pack and breed as yearlings. This flexibility allows rapid increase in numbers when times are good, contributing to their incredible resilience to persecution. Whether it helps them catch that pesky roadrunner, however, remains unknown.

Lucy is a broadcaster, zoologist and author of Bitch: What Does It Mean To Be Female? (Penguin paperback on sale now)

ID GUIDE

The stoat, with its long, slender body and black-tipped tail, is one of Britain’s most elusive animals. So count yourself lucky if you spot one in the flesh – instead, you may need to resort to field signs, such as droppings, to confirm its whereabouts. Stoats mainly feed on water voles, rabbits and other small mammals, so look for faeces containing bits of bone and hair. Like other carnivores, their droppings are thin with twisted ends, blackish brown in colour and deposited singly. Up to 8cm in length, they are longer and thicker than weasel droppings.

Chaffinches are noisy and usually heard before they’re seen

Among the most widespread small birds in Europe, chaffinches have been the subject of intensive study all over the continent, focusing on their vocalisations in particular. For example, we’ve discovered that male chaffinches deliver their cheerful song up to 3,000 times a day, sing with regional accents, and inherit bits of their song from their parents but pick up the rest by listening to other birds and learning on the job.

But one chaffinch call remains a mystery: a repetitive, monosyllabic whistle heard in spring. In H is for Hawk, Helen Macdonald captures it perfectly: “One interrogatory note over and over again, like a telephone call from a bird deep in leaves.” As it was once thought to foretell rain, we call it the ‘rain call’, but another theory is that the singer is frustrated – by poor weather, the loss of a nest or some other disturbance. Ben Hoare

Stoat droppings give off a neutral musky aroma

MWILDLIFE SPECTACLES

MWILDLIFE SPECTACLES

The broadcaster, naturalist and tour guide shares the most breathtaking seasonal events in the world

The heights of the cliffs and canyons of the Andes is where to spot these mighty creatures

Animal superlatives always excite the enquiring mind. Questions such as what is the biggest, smallest, longest and fastest have long been a staple of the pub quiz. If recordbreakers are your bag, then the Andean condor – both the heaviest bird of prey and the raptor with the longest wingspan – needs little introduction. With a wingspan (for the record) maxing out at around 3.2m, and weighing up to 15kg, adult Andean condors have principally dark plumage and black primaries, or ‘fingers’, which contrast to their startlingly white secondary flight feathers and white ‘fluffy’ neck collar. They also possess naked, fleshy

So natural is the Andean condor’s soaring that one bird was found to have flown for five hours, covering a distance of 160km, without once flapping its wings.

heads, presumably a hygienic adaptation that allows them to delve into animal carcasses without their plumage becoming overly soiled by innards.

Andean condors are the only New World vulture to display sexual dimorphism. The bigger males have a large, dark red comb, or caruncle, on the crown of the head, that surely plays a key role when the time comes for this sexually monogamous species to find its life-partner.

As masters in the art of effortless soaring, it is up in the air where condors excel. Using a combination of wind gusts, currents of warm rising air and streams of air pushed upwards by cliffs and mountains, condors are able to spend hours on the wing, in a perennial hunt for carrion. So efficient is this

Condors are vultures, so they keep their sharp eyes peeled for the carrion that makes up most of their diet

“As masters in the art of effortless soaring, it is up in the air where condors excel”

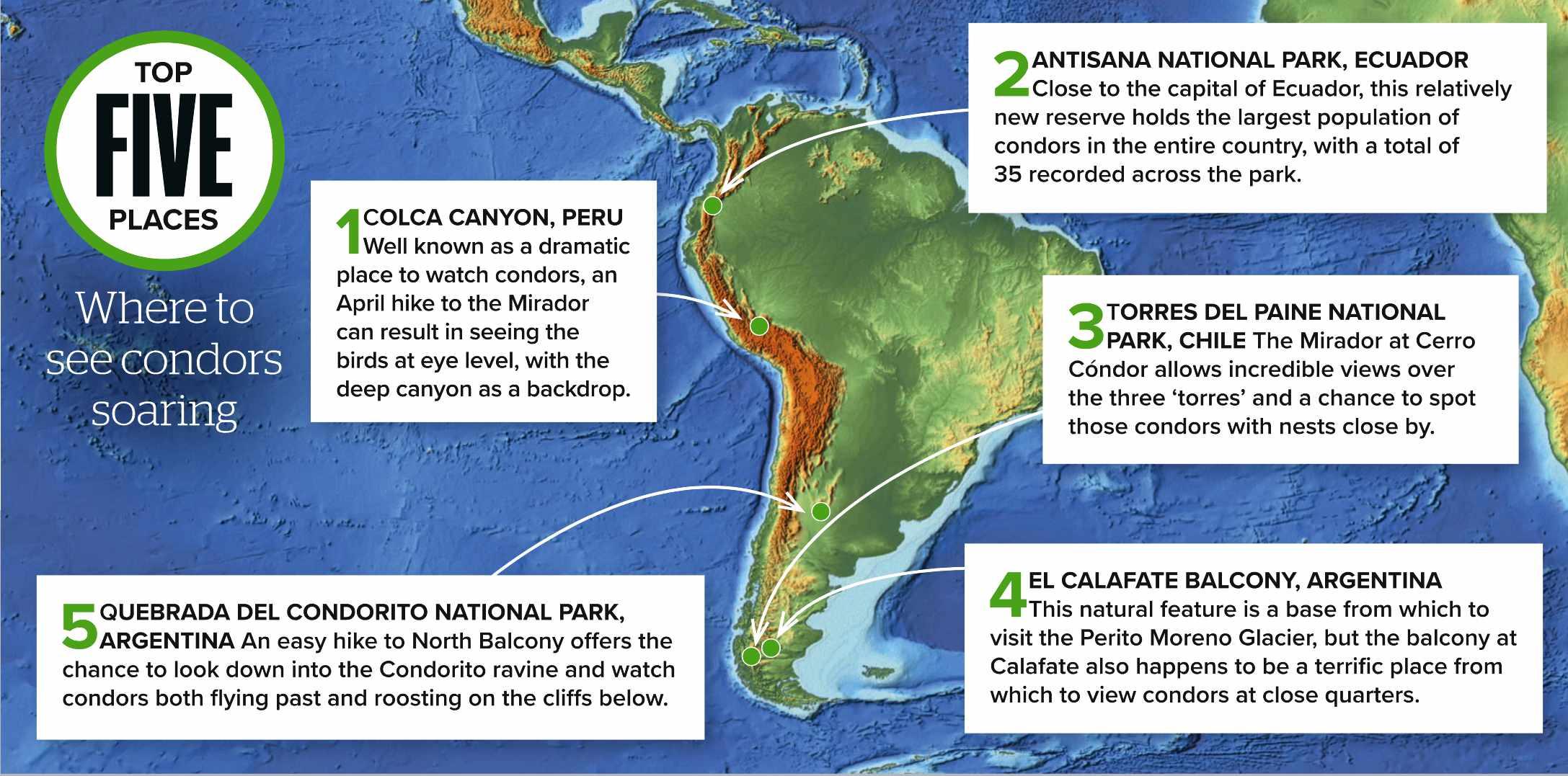

1COLCA CANYON, PERU

Well known as a dramatic place to watch condors, an April hike to the Mirador can result in seeing the birds at eye level, with the deep canyon as a backdrop.

5QUEBRADA DEL CONDORITO NATIONAL PARK, ARGENTINA An easy hike to North Balcony offers the chance to look down into the Condorito ravine and watch condors both flying past and roosting on the cliffs below.

2ANTISANA NATIONAL PARK, ECUADOR

Close to the capital of Ecuador, this relatively new reserve holds the largest population of condors in the entire country, with a total of 35 recorded across the park.

3TORRES DEL PAINE NATIONAL PARK, CHILE The Mirador at Cerro Cóndor allows incredible views over the three ‘torres’ and a chance to spot those condors with nests close by.

4EL CALAFATE BALCONY, ARGENTINA

This natural feature is a base from which to visit the Perito Moreno Glacier, but the balcony at Calafate also happens to be a terrific place from which to view condors at close quarters.

technique that equipment recently strapped to condors in Patagonia revealed that only one per cent of the birds’ time aloft is spent flapping their wings – with this mostly occurring during take-off.

Searching far and wide for food, condors use their razor-sharp eyesight to find a meal directly, or to locate large congregations of smaller raptors and scavengers, which invariably indicate a carcass. They most commonly feed on large carrion, with their food of choice historically being llamas, guanacos and rheas, but as these species have been displaced by farm animals, attention has shifted to cows, horses, sheep and goats.

bills to rip open the carcass. They must also realise that once the ‘big boys’ have had their fill, there will still be plenty to go round.

As carrion-feeders, condors and their scavenging cadre also play a key role as nature’s clean-up crew. This ‘recycling’ process both reduces the risk of dead and decaying animals becoming vectors of disease and helps to speed up the biodegradation process by microbes waiting in the wings.

“In South America the condor has been a cultural symbol for thousands of years”

Even if the condors are late to the party, they use and abuse their size to ensure they are first to tuck in, favouring the internal organs and muscles. Smaller scavengers may be shoved aside, yet they nonetheless rely upon the condors’ strength and hooked

Condors tend to roost communally, favouring remote caves, cliff ledges and rocky outcrops that are out of reach of ground predators. Usually covered in whitewash from the birds’ droppings, these roosting spots can stand out from a distance.

Despite a lifespan of up to 50 years in the wild, the condor’s slow reproductive rate (one chick every two to three years) and delayed maturity leave it remarkably susceptible to persecution. Illegal poisoning of carcasses remains a huge issue, with 34 birds killed in one incident in Argentina in 2018. Many farmers and ranchers perhaps see condors as little more than a pest species harassing their livestock, resulting in severe declines.

However, hope exists for the bird in the form of a reintroduction project currently taking place in Patagonia National Park. Environmental education programmes are also helping young South Americans renew their appreciation of a bird that has been a cultural symbol for thousands of years – just like the Incas, who honoured this supreme species in the 15th century with their Temple of the Condor at Machu Picchu.

The Andean condor is so revered across its range that it features on the national shields of four different countries: Bolivia, Chile, Colombia and Ecuador. Ecuador has gone a step further, placing the coat of arms on its flag. Here the condor, with its outstretched wings, is thought to symbolise power, greatness and strength.

By the time the single juvenile condor fledges from its home on a remote cliff ledge, its plumage will be smoky brown. Young birds then undergo a long, continual moult as their plumage darkens, but they still need an astonishing eight years before graduating to their parents’ black and white.

Adult condors have been observed defecating on their legs, which turn white. Either this helps to cool legs when temperatures rise during the day, or the guano, which contains traces of the bird’s digestive juices, operates as an antiseptic whenever the bird is thigh-deep in a rotting carcass. LOOK

Forever young, or so it seems

Mike checks out the dance moves of mating flamingos

Discover how

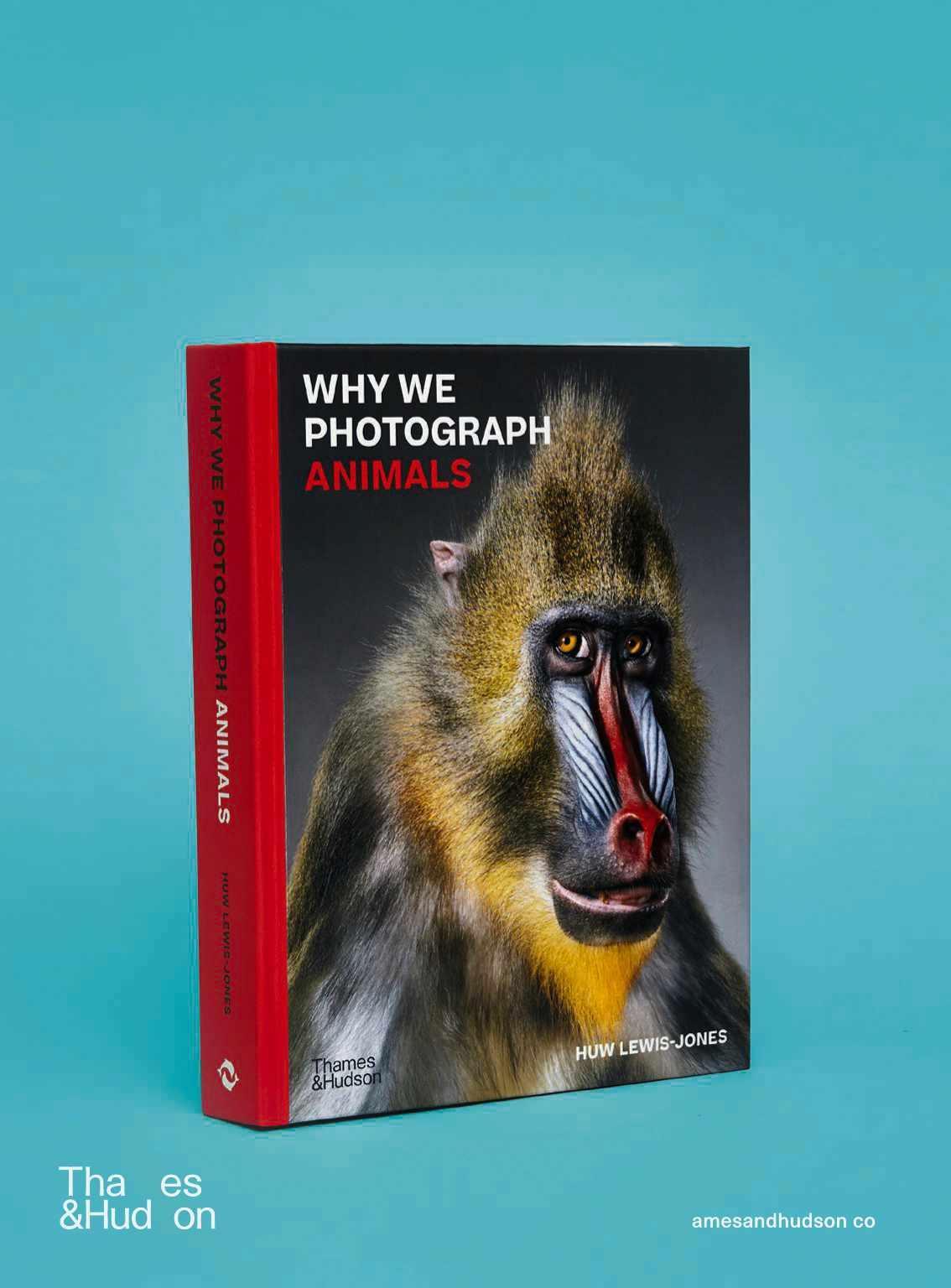

photograph animals and why photographing them matters to us and

NO

Family safaris No single supplement safaris Birding safaris

Walking safaris Conservation safaris Photographic safaris

Ladies-only safaris Canoe safaris Safari honeymoons and weddings Horse and camelback safaris Green season safaris

Tailormade

Chad, Congo, Ethiopia, India, Indian Ocean, Kenya, Madagascar, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Rwanda, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Tanzania, Uganda, Zambia, Zanzibar and Zimbabwe

WWW.TRACKSSAFARIS.CO.UK

The popular naturalist, author and TV presenter reveals a secret realm of overlooked wildlife

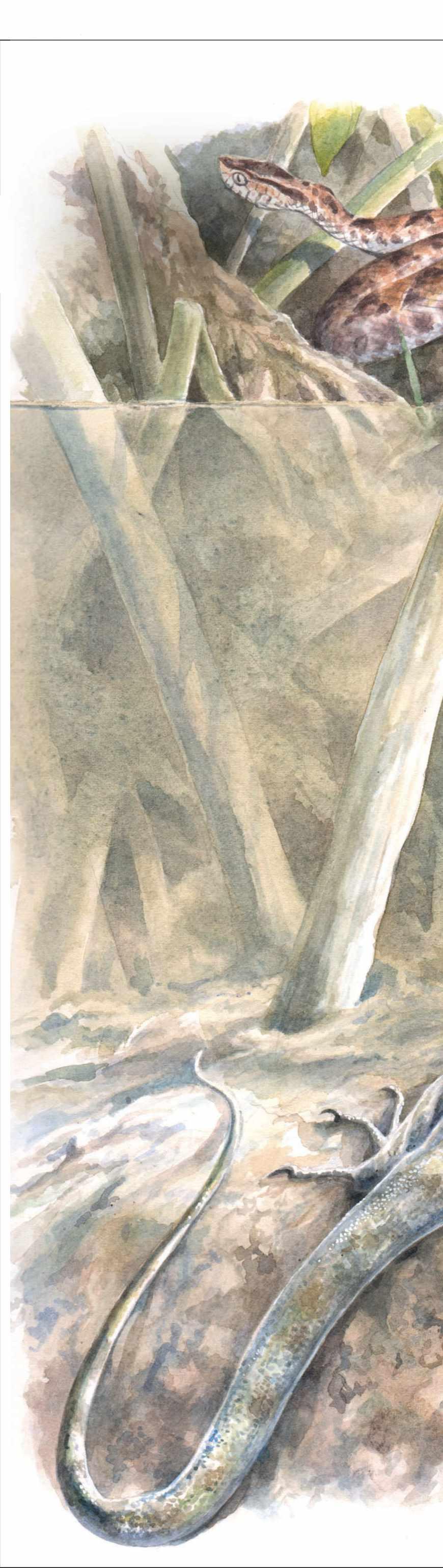

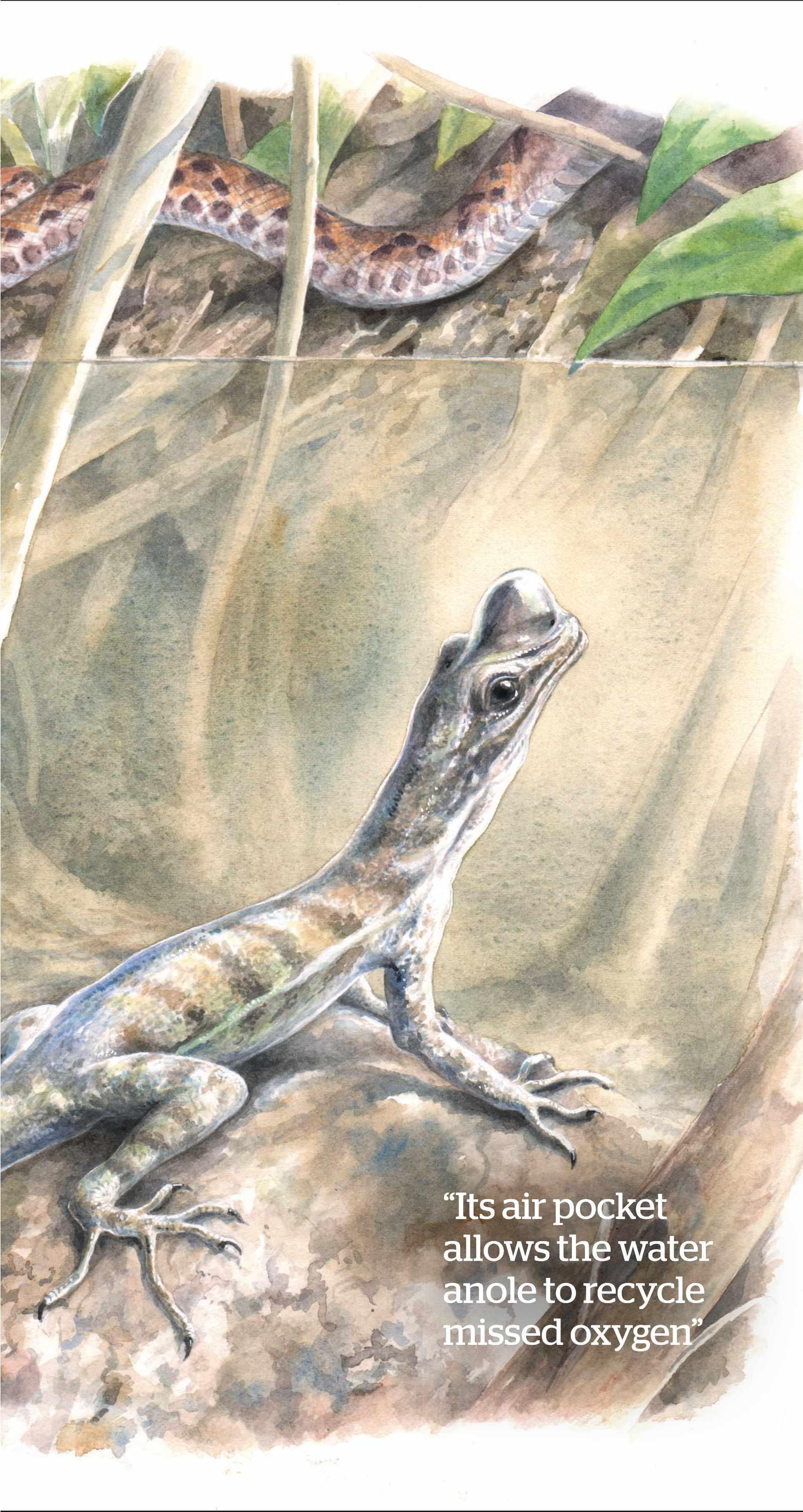

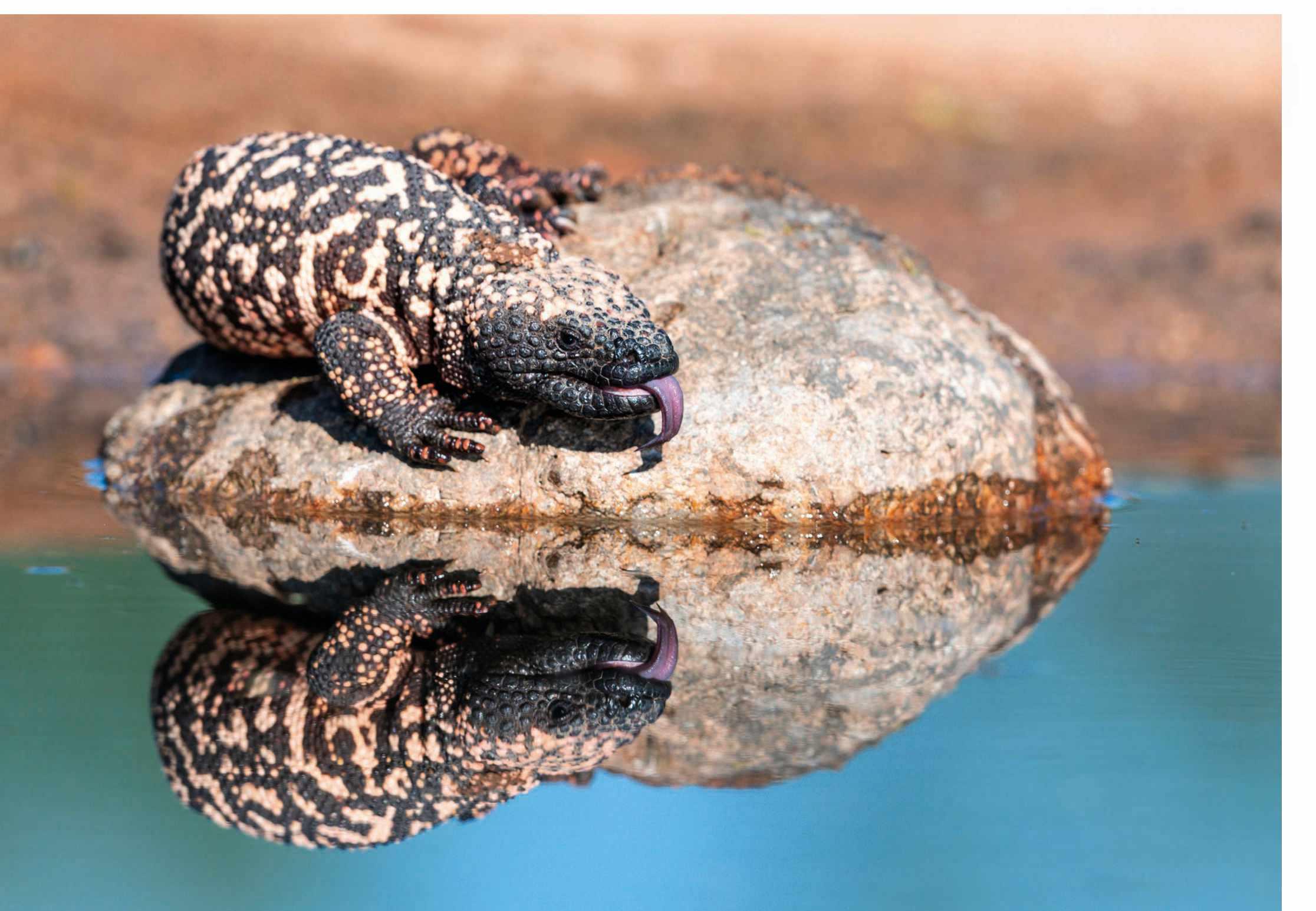

Plop! A lizard leapt from the verdant foliage fringing a tropical stream and into the dappled pools below. It was a common occurrence as I traced my path along the banks, and sometimes I caught a glimpse. All skinny and scaled, these lizards were sometimes basilisk lizards, but more often they were even daintier anole lizards. I wondered what happened after they dipped below the surface, and if I had followed my curiosity, I may have noticed something quite amazing.

Anoles are an extremely successful family of lizards, with more than 400 species. They are found throughout the warmer regions of the Americas, almost anywhere you care to look. From urban shrubberies and gardens to wild, tangled, tropical forest, you will find an anole somewhere, hunting insects or sipping nectar from flowers.

These small lizards are easily overlooked. Many are brown or green, with bands and spangles of contrasting markings, and they are on the slim side, too – twiggy lizards in a world of twigs. The only time they catch the eye is when

the males of some species flash a brightly coloured chin flap, called a dewlap, at each other and potential mates.

Several species are closely associated with fresh water. The water anole (Anolis aquaticus) – whose name says it all – is one of these, never straying far from forest streams. Here, it makes an understated living, skittering after insects among a tangle of riparian roots, stems, leaves and rocks. Never reaching more than 7cm (excluding the tail), water anoles find themselves on the menu for birds, snakes and mammals – I’ve even found them tangled in the webs of orb spiders.

Other than lightning agility and exceptional camouflage, it turns out that these marvellous little lizards have yet another cunning way of evading capture that has only recently come to light. Dropping into the water is a common strategy in nature; many frogs do it, green iguanas do it, even pythons and nestling hoatzin birds do it. What sets the anole apart is that it can extend its subaquatic stay by more than a quarter of an hour by breathing underwater – or more accurately, re-breathing.

“Its air pocket allows the water anole to recycle missed oxygen”

The moment the water anole submerges, it transforms into a mercurial lizard, enshrouded in a thin layer of air due to the rough texture and waterproof nature of its scaled skin. But it’s what happens next that is the really surprising bit. A bubble appears at the top of the head, over the snout. It expands, stretches, connects with the rest of the air pocket surrounding its body, and is then sucked back into the anole’s nostrils. Not one bubble escapes to the surface.

When a living creature inhales, oxygen enters the body and carbon dioxide, the waste product of our metabolism, is exhaled. However, not all the oxygen is extracted in each breath, so some remains in the exhalation. The water anole’s air pocket allows it to recycle this ‘missed’ oxygen. Some anoles will do this dozens of times in a single dive, recycling the air in the pocket and using the oxygen within.

It is also likely that due to the highly soluble nature of carbon dioxide and, to an extent, oxygen in water, the large surface area of the thin layer of air surrounding the anole also acts as a ‘plastron’ or physical gill, with carbon dioxide leaving the system and dissolving in the surrounding water, and oxygen the reverse. All of which enables the anole to sit it out at the bottom of the stream for a short spell until the threatening predator has moved on.

Anoles have a hierarchy with older, larger dominant males perching higher and nearer to the water than smaller juveniles.

The water boatman is able to dive

Taking the air

Several invertebrate animals also utilise a ‘plastron’ to extend their stay underwater. Well-known examples are pond beetles and water boatmen. Though they are aquatic insects, they don’t have gills. Instead they breathe in oxygen via air holes called tracheae along the sides of their bodies, and must replenish the oxygen in their plastron by coming back up to the surface.

Mammals

The first episode of Mammals aired on 31st March. Catch up on iPlayer.

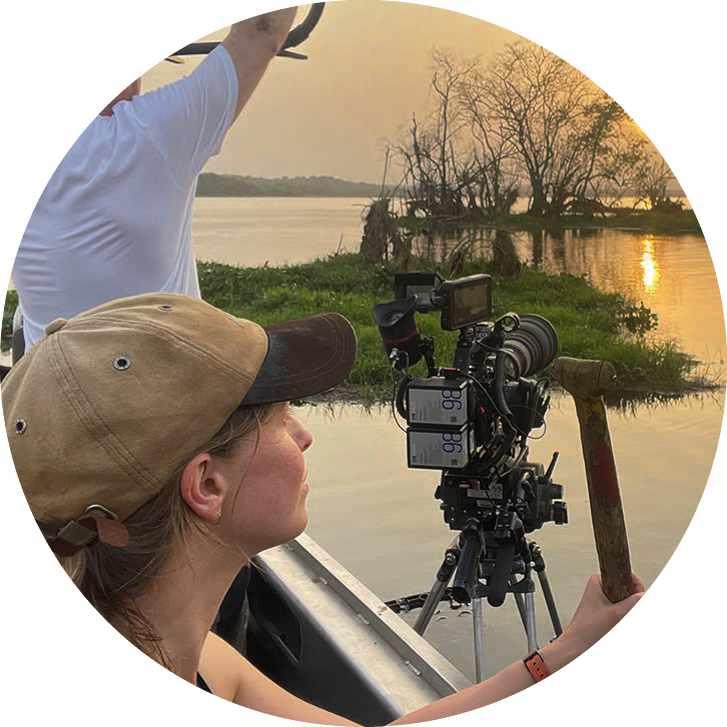

With the BBC series Mammals airing this spring, the series producer reveals how the crew captured some of our favourite animals in a whole new light

By SCOTT ALEXANDER

Ask anyone what their favourite animal is and chances are it will be a mammal. Lions, whales, dolphins, tigers, chimps, bears – they are all iconic. So being asked to make a new six-part BBC series about this extraordinary group of animals was a complete gift, and it’s fantastic to have Sir David Attenborough on board as the narrator. It’s been 20 years since he made Life of Mammals and the world has changed greatly since then.

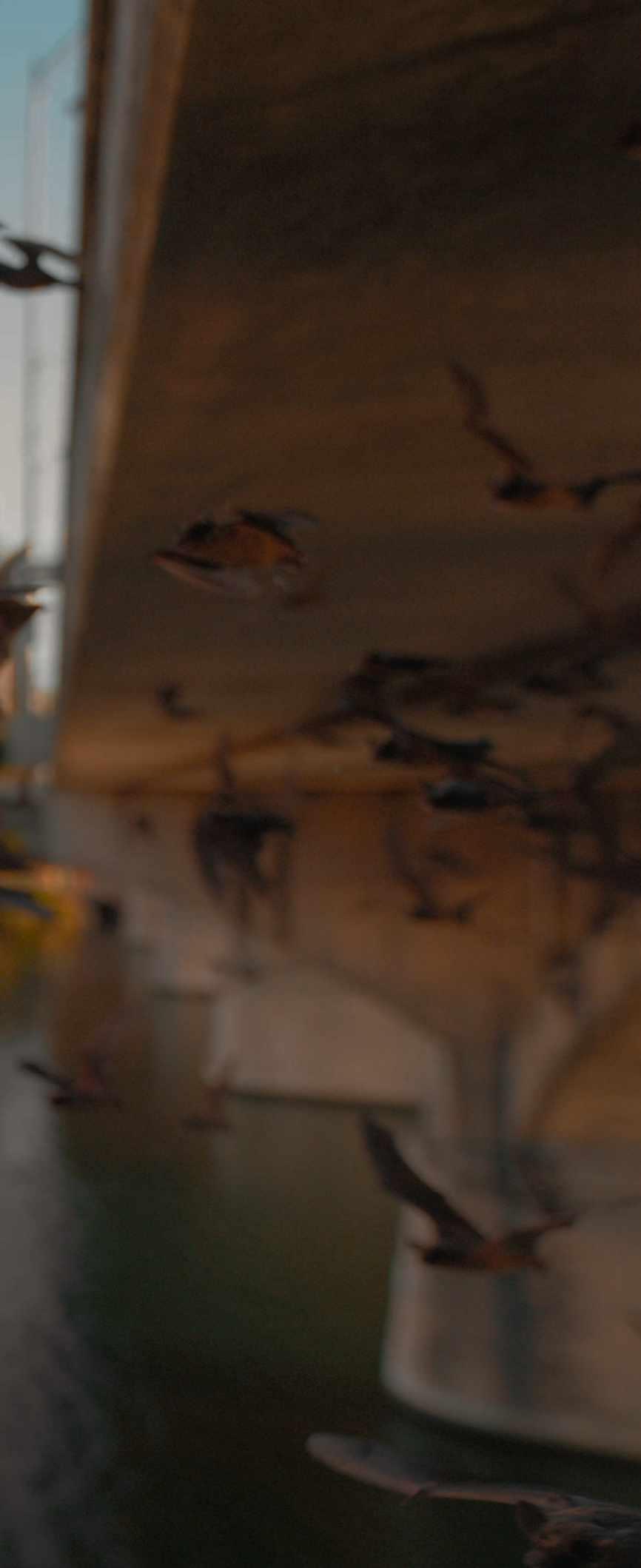

In the city of Austin, Texas, more than one million Mexican free-tailed bats take to the

Of course, the fact that mammals are so popular means they have featured in many natural history series in the interim. Our challenge – and it was a big one – was to find new and interesting stories that could surprise and entertain an audience that might think they have seen it all. And the fantastically talented Mammals team always came up trumps. Whether it involved spending weeks shivering in a hide, riding out ferocious ocean storms, getting sandblasted in the desert or being robbed by South American bandits, they pulled out all the stops to capture never-before-seen footage and bring fresh characters to our television screens.

Take the wolverine. For many, it’s a creature of myth, a Marvel Comics character with superpowers; for others it’s a gnarly and ferocious mustelid. But Mammals reveals the reality of the species and the rarely seen caring side of parents raising a kit. It

While the city sleeps, Chicago’s 4,000 coyotes get to work

With heightened senses verging on superpowers, more than two-thirds of mammal species are creatures of the night. In the Kalahari Desert, Damaraland mole rats live underground in permanent darkness. Elsewhere, in America, coyotes have started hunting at night in the country’s busiest and biggest cities.

Today, the planet is changing faster than ever, and mammals must adapt if they are to survive in the new wild. An abandoned minefield provides Indian wolves with a sanctuary, out of reach of humans, while American buffalo have been given a helping hand: vast managed herds fill their ancestral plains once again.

turns out there was a good reason no-one had attempted to film a wolverine sequence before, though. They are notoriously elusive creatures and live in the coldest, harshest landscapes, such as the remote Alaskan tundra. I must admit, when producer Will Lawson suggested the idea, I wondered if he had lost his senses. But I also knew that this was exactly the type of challenge we should be taking on, despite the high risk of failure.

It took two shoots, more than 40 days in the field, multiple blizzards, many miles covered on snowmobiles, frozen equipment (and fingers) and endless days spent alone in a tiny hide before cameraman Neil Anderson at last managed to film the behaviour we were seeking –a male wolverine delivering pieces of caribou carcass to its young kit.

But we still hadn’t got the key shot we needed

“The hardest, most dangerous – and strangest – of all the shoots involved Indian wolves living in a minefield”

to complete the sequence. Having run out of time in the field, we were forced to leave our notoriously unreliable remote cameras behind in a last roll of the dice. Six weeks later, the camera cards arrived back at the Natural History Unit in Bristol. We had filmed – for the very first time – a mother wolverine leaving her snow den, followed closely by her adorable youngster.

On other occasions, we were able to capture not just the rarely seen nature of a wild mammal, but stunning new behaviour. Off the coast of Western Australia, the number of humpback whales giving birth has risen from a few hundred to tens of thousands, and it’s a phenomenon

that hasn’t gone unnoticed by the orcas that feed on their young. But their strategy – one orca distracts a mother humpback while others attempt to drown her calf – is not without risk. The huge, thrashing tail fin and large flukes of the defensive female can easily injure an orca. So, one small group has developed a new approach. They kidnap the calf, leading it away from its mother as quickly as possible, and only then do they attack. It’s a poignant moment in the series and a reminder of how tough nature can be.

One question I’m often asked is what’s the hardest or most dangerous thing to film? My usual answer is anything underwater, at night, in the dark or in extreme cold – so that covers just about everything in the

Cold, Water and Dark episodes of Mammals!

There was one hairy moment when a team managed to get their open-sided camera car stuck in warthog burrow and were swiftly surrounded by a pride of hungry lions. But the hardest, most dangerous – and strangest – of all the shoots involved Indian wolves living in an abandoned minefield from a war between Israel and Syria.

Even before we were on location, producer Lydia Baines and researcher Amy Downes had to complete a week-long ‘hostile environment’ training course. These are normally reserved for journalists entering war zones, and cover topics such as catastrophic bleeds and how to recognise minefields and avoid hostile crowds. Only once everyone was happy that we’d done everything we could to mitigate all the risks was the shoot signed off, and the crew departed to spend three weeks treading very carefully. As for the wolves, their keen sense of smell and ability to avoid the mines means that this unlikely landscape offers them a safe space to raise their young, away from the persecution that so many wolves still face around the world.

There are plenty of lighter, funny moments too. An amorous hairy armadillo seeking romance in an old milking parlour

3

A Californian sealion pursues a sardine baitball off Mexico

From freshwater jungle ponds to the depths of the open ocean, mammals have found ways to overcome the many challenges of life in water. Follow a sperm whale as it chases its prey into depths far beyond that of any other air-breathing mammal and hungry Californian sealions pursuing huge shoals of sardines.

A wolverine kit takes its first steps outside the den with its mother

From ice-covered seas to snow-capped mountains, mammals have conquered the cold, living in the most inhospitable places on Earth. In Alaska, the mysterious wolverine tenderly raises its young, and on the Arctic islands of Svalbard, a polar bear leaves the coast in pursuit of reindeer.

is one; echidnas blowing snot bubbles in an unusual way of cooling down is another. Perhaps my favourite scene from the series is when we witness a young chimpanzee hoping to get a taste of a real jungle treat – honey. The look of disappointment when the troop leader doesn’t share is one I’ve seen in my own children, and a reminder of how closely related we are to these wonderful animals.

Yet the series cannot shy away from the fact that since the arrival of humans, many mammals have become extinct – some directly at our hands, others indirectly as a result of pollution, global warming and habitat loss. Primates, including the great apes, are among the most seriously threatened, and we can’t ignore their stories. But some of those stories might not be quite what you expect.

When I heard of pig-tailed macaques in Malaysia learning to hunt rats in palmoil plantations, I knew we had to try and capture this never-before-filmed behaviour. We soon found ourselves in a hot, sticky, leech-ridden plantation dressed in brightorange, long-sleeved tops. The reason behind this strange uniform was that we hoped by wearing the same outfits as the researchers,

the macaques wouldn’t be too suspicious. It worked, because we soon witnessed them searching the base of palm fronds at the top of a tree, then flushing out their quarry, which they skilfully caught. The alpha male waited patiently on the ground below for any rats making a desperate leap for freedom, devouring his unfortunate victims headfirst.

Once thought of as a nuisance by the plantation owners, the macaques are now seen as a possible biological control, with one group catching around 3,000 rats a year. Without the dedication of local experts, scientists and research teams, we wouldn’t be able to find fantastic new stories like this.

Wild mammals are increasingly living in close proximity to humans, and a cheetah hunt from the series epitomises this dynamic. I have filmed cheetah hunts on many occasions, but not like this. At one

point, we saw around 70 tourist vehicles surrounding the kill, which can have a devastating impact on cub survival rates. Millions of people visit Africa’s national parks every year, bringing much-needed revenue that supports wildlife, but we are at risk of losing the very animals we’ve come to see. Such scenes aren’t often shown in glossy wildlife shows, but I wanted to have this unfiltered approach, without pointing fingers or lecturing the viewer.

Some of the most enduring images from the series are from sequences where mammals and humans co-exist. Dark features one of the most beautiful wildlife spectacles on Earth, as more than a million Mexican free-tailed bats fly out from under the Congress Avenue Bridge in Austin, Texas.

“We filmed bold sealions strolling around fish markets and otters frolicking in fountains”

There are more bats than people living in the city and they draw an appreciative crowd. Elsewhere, we filmed wily coyotes moving back into urban areas under cover of darkness, bold sealions strolling around the fish markets of Chile and otters frolicking in the fountains of downtown Singapore.

The adaptability of mammals has made them arguably the most successful animals on the planet, but today their lives lie in the hands of just one – us. By showing just how remarkable they are, I hope we can learn to appreciate them and find that delicate balance that lets us share this incredible planet with its incredible diversity of life.

Scott Alexander is BBC Studios’ Natural History Unit series producer on Mammals. He has worked on series such as Big Cat Live and Seven Worlds, One Planet with Sir David Attenborough.

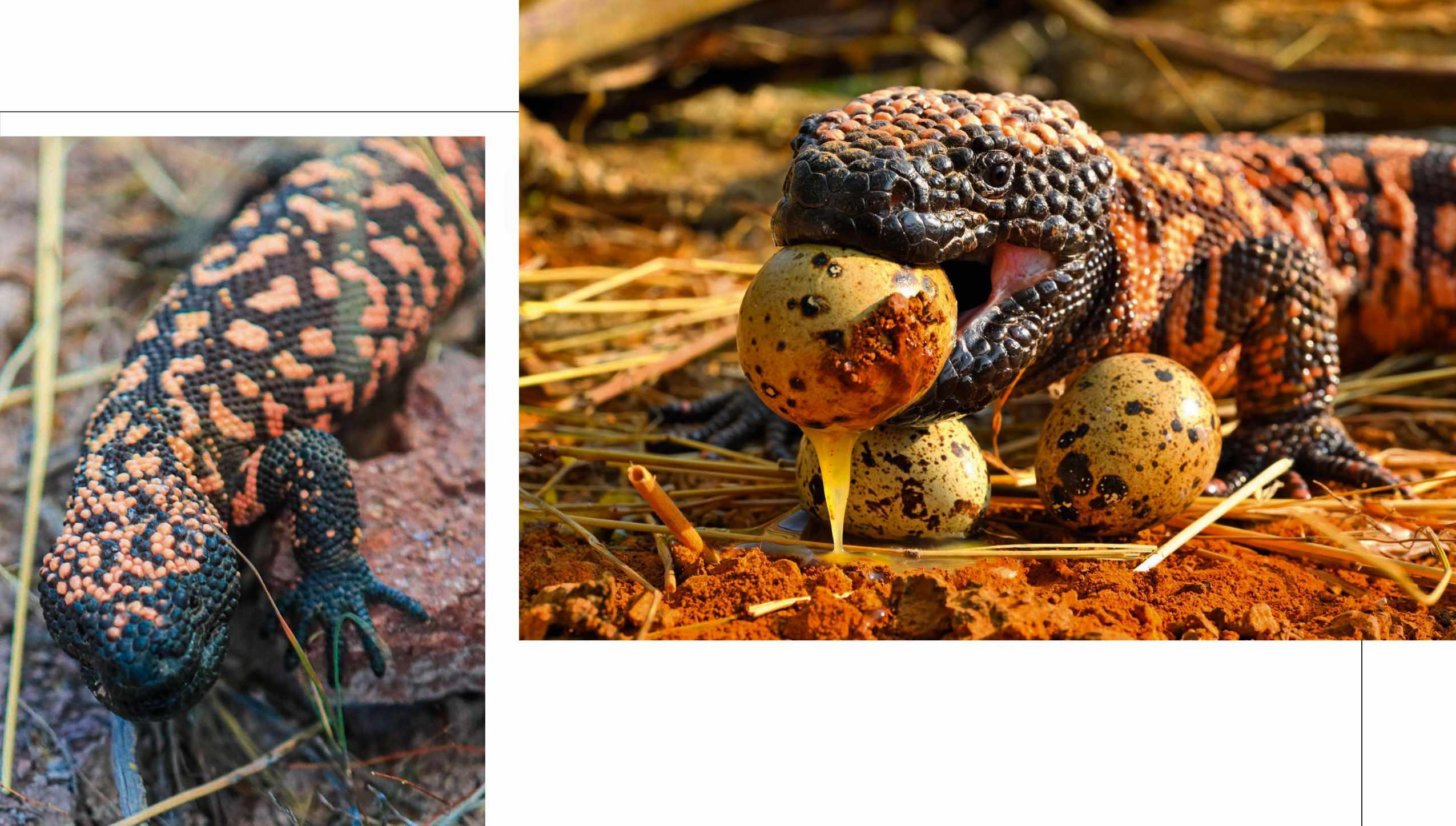

IVF is providing one last chance to save the northern white rhino from extinction

Photos by JON A JUÁREZ

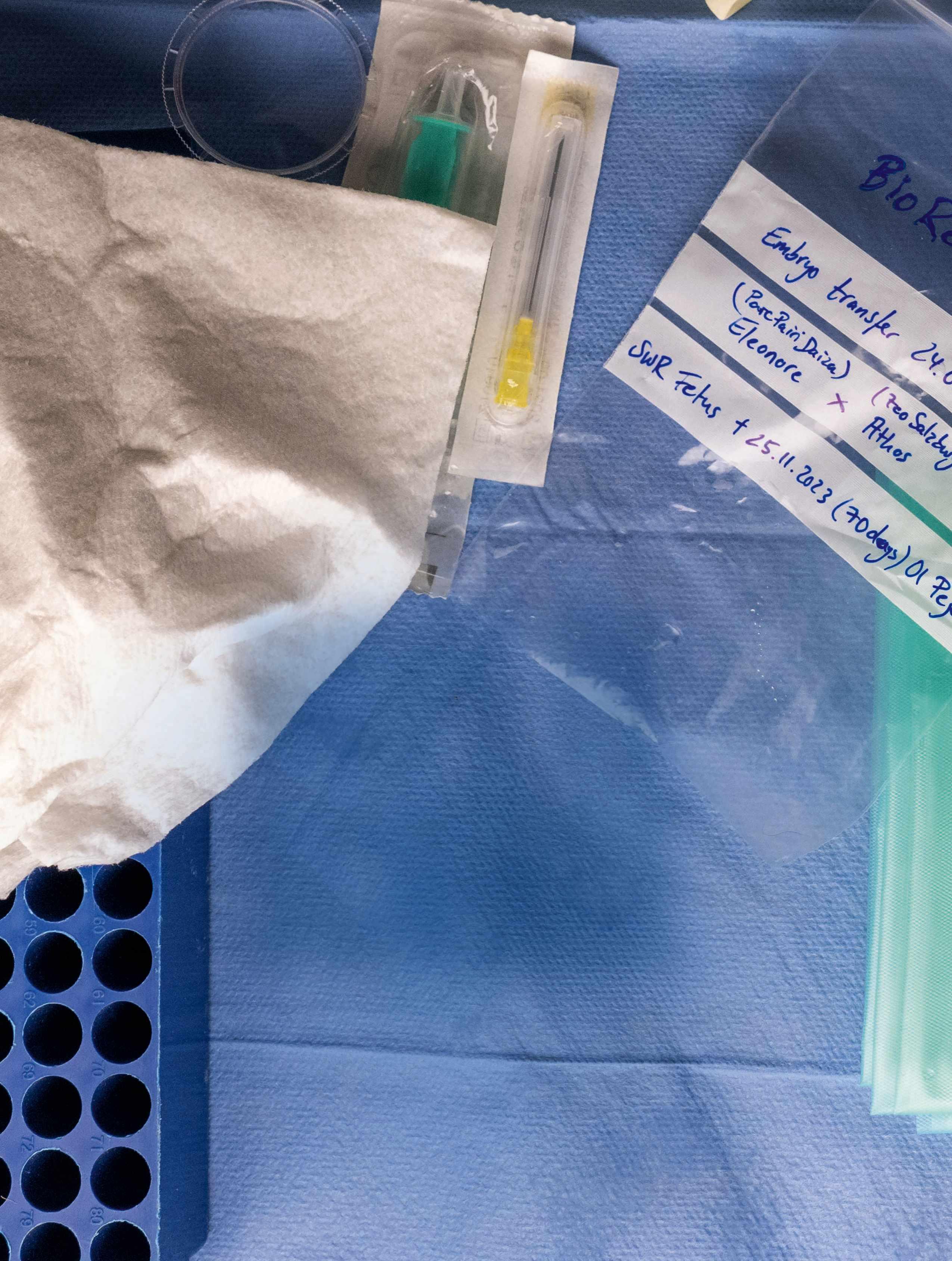

Though it died at just 70 days old, this tiny southern white rhino foetus offers hope. The baby was the result of the first successful attempt to perform IVF on a rhino, carried out by scientists from the BioRescue project in September 2023. The unborn calf had been developing well, but its mother, Curra, died from an unrelated bacterial infection. Now that the procedure has been proven to work, it can be applied to the northern white rhino, potentially helping to save this subspecies from extinction.

The northern white rhino population has been decimated by poaching. Only two individuals remain, a female called Najin (age 34, above), and her daughter, Fatu (age 23). The pair live in Kenya's Ol Pejeta Reserve under constant guard. For reasons of age and health, neither can carry a pregnancy to term, so any IVF procedure will use Fatu's eggs and a female southern white rhino as a surrogate.

IVF, though well established in humans and domestic animals, is incredibly complex in wild species, particularly large animals such as rhinos. As such, ethical risk assessments are implemented for every step of the procedure. Curra's successful implantation was the lucky 13th attempt at IVF in southern whites.

Jon A Juárez is a photographer with a degree in biology and a keen interest in conservation. He is a member of the German Society for Nature Photography. See more of his work at highwaysandbyways. de; jonjuarez.photo.

The last northern white males, Suni and Sudan, died in 2014 and 2018 respectively. This memorial at Ol Pejeta is dedicated to them, and to all rhinos killed by poaching.

A male southern white rhino called Ouwan, the ‘teaser bull’ for Curra's implantation, undergoes a health check. A teaser bull is a sterilised male that detects when a female is fertile, thus signalling the best time for her to be artificially inseminated. Ouwan died in November 2023, three days before Curra. Both fell victim to serious infection after heavy rain reportedly released bacteria from the soil in their enclosure.

Curra receiving a health check from Thomas Hildebrandt, head of BioRescue, which determined that she was ready to receive the embryo. The sperm originated from a male called Athos from Salzburg Zoo in Austria; the egg from a female called Elenore from Pairi Daiza Zoo in Belgium.

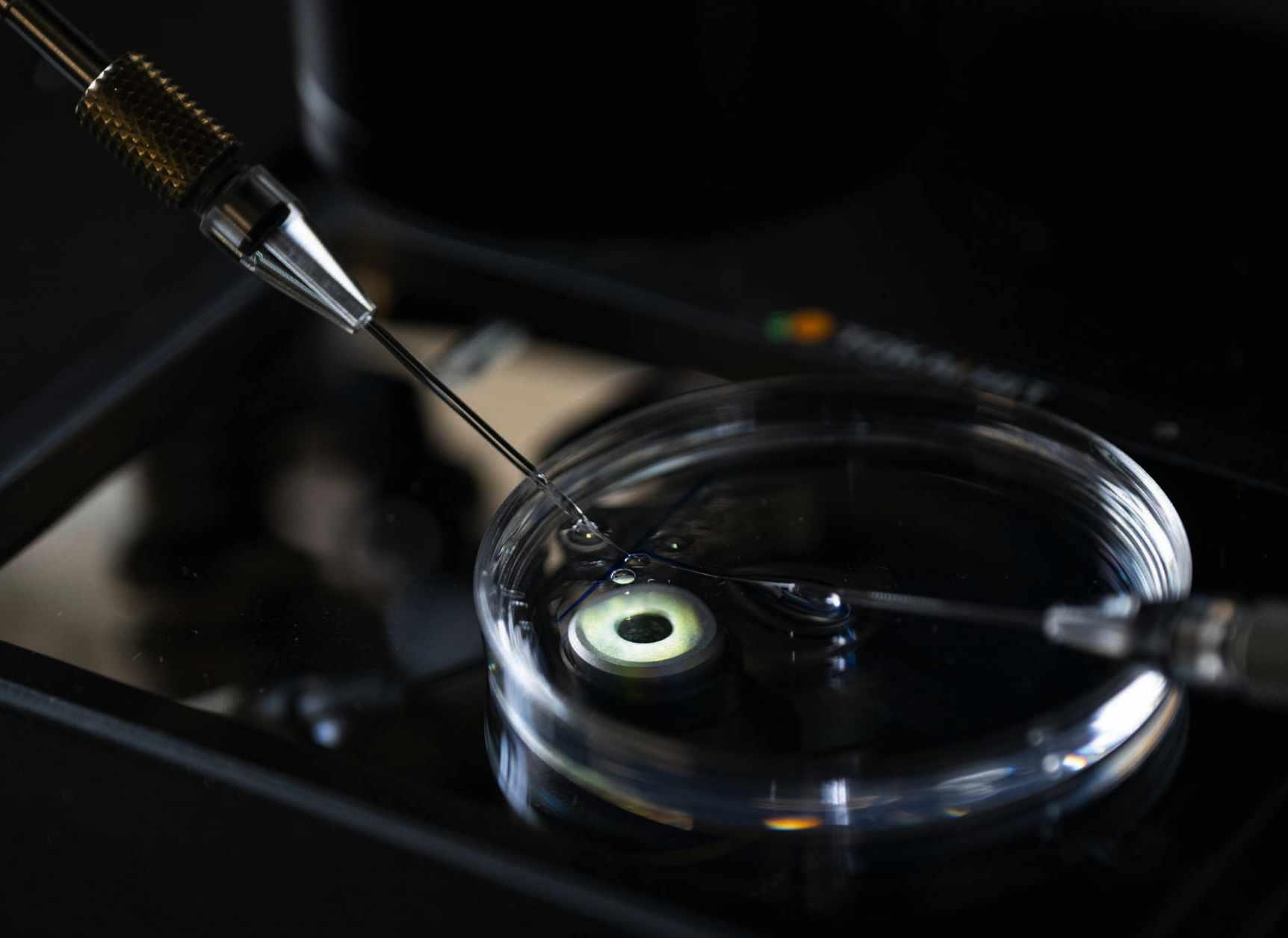

Scientists from BioRescue study egg cells harvested from Fatu. The science of rhino IVF is entirely new ground – all the veterinary and scientific procedures, from sperm injection to storage to use of liquid nitrogen, and all protocols, methods and equipment have had to be developed from scratch. It has taken years of research to get to this point.

Najin undergoes a standing sedation procedure during a regular health check. As an experienced female, she will play an important role in transferring knowledge to any northern white rhino calves born through IVF.

Twelve previous attempts had been made at southern white rhino IVF over the years. One took place in January 2021 at a zoo in Germany. The surrogate was a female called Clara, who is here being sedated before receiving the embryo transfer.

Fatu undergoes a health check. She must be kept in good condition while the BioRescue team prepares for the first attempt at IVF in a northern white rhino. Next steps are to identify a suitable surrogate mother and a teaser male, a process that could well take several months.

There are currently 30 northern white rhino embryos in storage (alongside cells from 12 other individuals) preserved in liquid nitrogen at -196˚C. These were created using Fatu's eggs and sperm from Suni and another male called Angalifu, who lived in San Diego Zoo and died in 2014. Lack of genetic variety is a limitation, and scientists are trying to counter this using stem-cell technology. Museum samples could also assist in genetic enrichment.

Ouwan receiving a sedation dart before a routine examination. Teaser bulls are vital to the IVF process, as they can detect female reproductive pheromones naturally and quickly – scientists cannot do this without performing intrusive procedures. As a teaser bull actually mates with the surrogate female, he must be sterilised to ensure he doesn't impregnate her himself.

(Above and left) Darling, a young southern white female who will one day be a surrogate, is translocated to a spacious compound at Ol Pejeta. Darling was sharing an enclosure with Ouwan and Curra, but her lesser dominance kept her away from them – and from the bacteria that caused their untimely deaths.

Zacharia Mutai is head caretaker at Ol Pejeta. He knows Najin and Fatu extremely well, having looked after them since they arrived at the conservancy in 2009. With hope, in the not too distant future, his two charges will become three.

Elephants are one of the ‘Big Five’ animals that can be trophy-hunted in Africa for eye-watering sums

She’s wept in her tent over countless nights. She’s posted photos of her grisly discoveries online, if you have the stomach for them.

Dickman, director of WildCRU, a top conservation research unit based at the University of Oxford, says these killings were mainly carried out by local people trying to protect their cattle and goats. Lions threaten both their livelihoods – and their lives.

As a scientist who’s had a lifelong passion for wildlife, you might assume that Dickman would also oppose trophy hunting, where large charismatic mammals are shot by wealthy tourists at vast expense – killed so that the hunter can return home with

James Fair is a wildlife journalist with a specialism in controversial issues. He spent 18 years as a writer and commissioning editor at BBC Wildlife. Read more at jamesfairwildlife.co.uk.

ince 2009, Amy Dickman has come across some horrific sights on the edge of Ruaha National Park in Central Tanzania where she studies, and tries to resolve, conflict between people and predators. They included lion cubs that had been speared and dumped in the bush and the carcasses of six lions, and 70 rare vultures, poisoned and left to endure long and painful deaths.

Praveen Moman, Volcanoes Safaris

“Unlike some forms of activity that use an animal once, the beauty of the mountain gorilla is that it has been producing tourism resources since the early 1980s. We are onto the third or fourth generation of gorillas, and they are still there and producing wealth for the future.”

a tale of derring-do and a head or set of horns to adorn a living-room wall with a malingering, eerie presence.

But she doesn’t. Instead, Dickman has become increasingly vocal about the probable impacts of blanket bans on trophy hunting that could lead to more animals being killed. If lions and other species generate revenue through trophy hunting, she argues, they and their habitat are more likely to be conserved.

The maths is hard to ignore. Around three villages outside of Ruaha, Dickman and her colleagues documented the killing of

35 large carnivores in one 18-month period. “This included 25 lions killed in one year in an area of much less than 500km²,” she says. In contrast, in areas managed for trophy hunting, the recommended quota is 0.5 lions per 1,000km².

In short, the level of killing where lions have no economic value was at least 100 times higher than is – or should be –permitted under trophy hunting.

On a broader scale, the area of land managed for trophy hunting in Africa is greater than all of its national parks combined – 1.4 million km², roughly equivalent to France, Germany and the UK combined. “On a personal level, I can’t

It is legal to hunt giraffes in some African countries

imagine trophy hunting,” says Dickman. “I’m an animal lover, I’m a vegetarian, I don’t understand it. But understanding it personally is very different from understanding the evidence around it.”

According to Tim Davenport, Africa director for the conservation group Re:wild, in Tanzania alone between 1,000 and 2,000 lions – or 4-8 per cent of the entire global population – are dependent on land managed for trophy hunting. “By stopping trophy hunting [in Tanzania] without alternative financing in place, game reserves will be turned into maize fields and cattle ranches within a few months or years,” he says. “I’ve seen it happen dozens of times.”

Not all scientists agree with Dickman and Davenport, though. Hans Bauer, who also works at WildCRU, says that trophy hunting doesn’t deliver for

“If we stopped trophy hunting here, local people would cut down the trees and make charcoal out of them. They would kill the wildlife to feed their family or for the bushmeat trade. In a matter of two or three years, you will have no trees, no bushes and no animals”

either people or wildlife in the way that it’s claimed. Hunting ‘blocks’ in many African countries are being abandoned because they don’t make money. “Across Africa, in the vast majority of cases, trophy hunting

has not delivered more lions – whether because of financial imbalances, increased terrorism, land mismanagement or increased livestock mobility (or a combination of these factors),” he wrote in an article for The Conservation. But let’s step back for a moment. What is trophy hunting, where does it happen, and why are we talking about it? First of all, it’s legal and involves the killing of charismatic wildlife according to quotas set as part of a broader management programme. It is not canned hunting, which is the practice of killing animals in small, fenced enclosures.

Many countries around the world permit trophy hunting. Visit the website Book Your Hunt, and you’ll see there are numerous hunting opportunities in North America, Eastern Europe, Southern Africa and Central Asia, far fewer in South

Taxidermied ‘trophies’ at a hunting convention in Nevada – heads are one of many sought-after bodyparts

America and South-East Asia. Neither India nor Kenya permit it.

Prices vary wildly. On Exmoor, you can shoot red or roe deer for as little as £150. You can hunt goats on Mallorca for £4,000 or non-native camels and wild boar in Australia for £10,000. In Zimbabwe, you won’t see any change out of £30,000 for the right to stalk and kill a leopard.

According to Adam Hart, professor of science communication at the University of Gloucester, who has co-written a comprehensive book about trophy hunting (simply called Trophy Hunting), eight out of the top ten countries ranked for their record in conserving large mammals permit trophy hunting. They include Botswana (1st), Tanzania (3rd) and Canada (8th).

Few people paid trophy hunting much attention until a lion nicknamed Cecil was killed by US dentist Walter Palmer just outside Hwange National Park in Zimbabwe in July 2015, but supporters and opponents have been debating its rights and wrongs, with increasing vehemency, ever since. Some people have mocked up images of Amy Dickman killing animals and posted them online, and she has received threatening letters. Celebrities such as Ricky Gervais

and Joanna Lumley have also joined in the conversation, voicing their objections to trophy hunting via social media.

This year, MPs tried to pass a law that would have banned British hunters from bringing back trophies from species protected under CITES. The bill passed easily through the House of Commons, but – controversially – fell foul of filibustering by peers in the Lords.

This wasn’t the only controversy stirred up by the bill. According to analysis by

“Everybody thinks that a lion is worth far more alive than dead, and yes that’s true in the more popular places, but not in remoter areas where tourism isn’t viable. And even if it is viable, you need 50 tourists for every hunter, so think of all those long flights and extra carbon emissions, think of the water demands.”

Hart, 75 per cent of statements made in support of the bill in the Commons were misleading or incorrect. They included the claim that lions could go extinct by 2050, something for which there is no evidence. Tim Davenport says that many people who object to trophy hunting don’t understand the realities of conservation in Africa. “What you’ve got is people discussing what they think is conservation, but it isn’t – it’s animal welfare,” he says.

But opposition to trophy hunting encompasses multiple strands. One complaint is that it perpetuates a colonial trope of rich white westerners exploiting the continent’s resources, which also keeps local people in poverty and prevents other ways of funding conservation taking root. Another is that permitted quotas can be too high, resulting in declining populations. And it’s cruel – tourist hunters are unlikely to be as skilled as their professional guides and can choose to use bows and arrows instead of guns to kill their quarry. Cecil, it’s claimed, took 40 hours to die.

Mucha Mkono, a lecturer in sustainable tourism at the University of Queensland, has looked at attitudes among African social media users to trophy hunting. She examined responses to news stories about the Cecil killing and found frequent references to the neo-colonial nature of the activity.

Shooting lions at a concession in Namibia, Africa

Mkono – who is Zimbabwean – says many people in Africa are uneasy with the idea of rich, white people flying in to shoot their wildlife. “Black people are economically precluded from participation in trophy hunting,” she points out, “and if they try to hunt wildlife for themselves, they can be penalised for poaching.”

Many African leaders accuse those trying to bring an end to trophy hunting of being

equally neo-colonial. It is not up to the UK or USA to tell Africans how to manage their environment, they argue – if they want to make money out of rich westerners hunting their wildlife, that’s up to them.

An equally contentious issue is what replaces trophy hunting were it to disappear. Even opponents concede that something has to. A lobbying document supported by groups that included the Born Free Foundation argues that the benefits to local communities are “often greatly exaggerated” and that – as a funding model – it’s on the decline. But it adds that the UK government should “provide additional resources for those countries” whose wildlife management model relies on revenue from trophy hunting should a ban be implemented. No funding pledge was given.

More tourism is not the answer. A lot of trophy hunting takes place in areas that are either too remote, not sufficiently scenic, or plagued by tsetse flies, making them unviable for westerners who like their home comforts.

But there are other alternatives, if only we were able to implement them. Ecologist

Leopards are hunted, despite being listed as Vulnerable

Mark Jones, Born Free

“Cecil the lion was shot with a bow and arrow, which is not designed to minimise suffering. In addition, trophy hunters will try to avoid damaging the parts of the animal that will become the trophy – typically the head – and consequently, there’s a high chance of a prolonged and painful death for the animal.”

and conservationist Ian Redmond, who has worked in Africa throughout his career, is a co-founder of Rebalance Earth, a new initiative that aims to help developing nations monetise their biodiversity.

Animals such as elephants, Redmond says, have enormous value while alive in terms of the ecosystem services they provide. It’s calculated that a single forest elephant helps trees store an estimated 9,500 tonnes of CO2 per km² by weeding out smaller trees, allowing those that survive to grow larger.

“The carbon value of a single forest elephant is $1.75 million,” Ralph Chami, another co-founder of Rebalance Earth, told a conference organised by Born Free in

The increase in white rhino numbers since trophy hunting was introduced in 1968 500

The number of lions found in Bubye Valley Conservancy in Zimbabwe today, a 40-fold increase since 1999 when it was first managed for trophy hunting

700,000

The number of trophies imported into the USA from 2016 to 2020. It is illegal to do so in France, the Netherlands and Australia.

The year Kenya banned all trophy hunting. Costa Rica and India are two other high profile examples.

$56M

The income generated by trophy hunting in Tanzania in 2008 – of this, $1.6m was spent on community development and just over $6m on wages (excluding professional hunters and managers).