The symphony that shows Beethoven at his playful best A

The symphony that shows Beethoven at his playful best A

We celebrate 300 years of this perennially uplifting Baroque masterpiece

Full February listings inside See p100

Carnal composers

The fevered love lives of the musical greats

Unsung heroes

Why we should value opera librettists more

A life with Bach Masaaki Suzuki on an unshakeable obsession

100 reviews by the world’s finest critics Recordings & books – see p72

Pick a theme… and name your seven favourite examples

Domingo Hindoyan began his music training as a violinist and member of the Venezuelan musical education programme El Sistema, before studying conducting at the Haute école de musique de Genève. He is now chief conductor of the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra and principal guest conductor of the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra, and has worked with ensembles ranging from the Orchestre National de France to the Dresdner Philharmonie. In February he conducts the BBC Symphony at the Barbican in Copland’s Symphony No. 3.

Verdi Rigoletto – ‘Cortigiani, vil razza dannata’

This aria arrives as Gilda has just been kidnapped by the Duke’s courtiers and Rigoletto turns against the Duke. Until this point, he has felt plenty of bitterness, but has held it inside – only revealing it indirectly through jokes. But this is the first time that he lets it all out, and the way that Verdi handles this outpouring is fantastic, with a real sense of aggression in the voice, and this beautiful moto perpetuo in the strings. You can feel the emotion bursting from Rigoletto and he sweeps the audience up in that emotion with him.

Bruckner Symphony No. 9 – Scherzo

This is not the folksy Austrian scherzo that we might expect from Bruckner. This is something really ferocious, with an anger that comes from deep inside the composer. Bruckner was very religious, and I see this music as part of a conversation with God. But whereas other movements in the symphony are more celestial, this one seems to deal with the anguish of being alive; the frustration of making mistakes

here on earth, and of thinking, ‘What could I have done differently?’ Which is unsurprising, coming as it does from a musician who was totally insecure.

which respectively represent Mahler’s problems at the Vienna Opera, his issues with Alma Mahler and the heart condition that would eventually kill him. For superstitious reasons, the third hammer stroke sometimes isn’t performed. When I conducted the piece, however, I did include it. And I’m still here.

Schubert String Quartet No. 14, ‘Death and The Maiden’

Beethoven Violin Sonata No. 9, ‘Kreutzer’

It’s not surprising that Tolstoy took the ‘Kreutzer’ Sonata as a starting point for his famous novella about love, death and anger. There is so much rage in this piece of music: the moto perpetuo, the harsh chords, the violent pizzicati, the sudden contrasts, the way that Beethoven uses the half tone as a kind of dissonance. When I was young and played this on the violin, I took great pleasure in interpreting its anger. At the time, I hadn’t read the Tolstoy story. Now that I have, I think I’d play it even better.

Mahler Symphony No. 6

Often viewed as a fight against death, this is probably the most dramatic and tragic symphony ever. It’s full of sobbing melodies and the last movement is particularly famous because of its three hammer blows,

Sometimes, even when we feel angry, we remain diplomatic, while on the inside we are burning. And that is exactly the kind of anger we find in the second movement of this string quartet. It describes a dialogue in which a maiden begs the figure of Death to pass her by. She is fighting against Death, but not with a hammer, or with forceful rhythms. Instead, she does it through lyrical melodies. It’s a passive kind of anger, and it’s also autobiographical given that, when Schubert wrote this piece, he already had the syphilis that would kill him.

Berlioz Symphonie Fantastique – ‘Dream of a Witches’ Sabbath’

Berlioz wrote this to express the frustration of unrequited love: the kind of frustration that drives you to take opium, have hallucinations and hate the world. The result is full of extreme effects, not least the glissando in the strings, the use of bells, the demonic-sounding clarinet and, of course, this Dies Irae motif at the climax. It’s an extravagant expression of anger and totally revolutionary for its time, written in 1830 –just two years after Schubert died.

Puccini Tosca – ‘Vissi d’arte’

This moment – just before Tosca kills Scarpia – represents another type of anger: ‘Why me? I’ve been so good in life’. It’s a beautiful, lyrical piece, full of pathos. But a minute later, she kills with her own hands. It’s like those moments when you are alone at home and reflect on all the bad things that have happened to you, and the next day you emerge out of yourself and want to kill someone. But, of course, compared to Tosca, we are lucky. What she goes through is another level of bad.

Interview by Hannah Nepilova

Three hundred years ago, Antonio Vivaldi published The Four Seasons. But despite the work’s spectacular popularity today, it was not until the 20th century that it really discovered its true audience, writes Nicholas Kenyon

Late one evening when I was in the middle of writing this article, I was standing by my local bus stop checking my phone for the next arrival time. In a scene all too common these days, a cyclist swooped by me, snatched the phone, and was gone in an instant. More irritated than angry, I went home to report the theft and got on the landline to

and popular classical music works of the age. And their attraction cannot be based entirely on the poetry which is attached to them, nor to their programmatic content (which doesn’t get recited while you are on hold). The four concertos are brilliant, punchy, upbeat, concise pieces of music, each with three movements lasting a few minutes each. In this, they are music for our time – for an era of short attention

Vivaldi’s four concertos are brilliant, punchy, upbeat, concise pieces of music

my service provider. And lo and behold, as I was on hold, there came the soothingly cheerful sounds of ‘Spring’ from Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons. It was difficult not to feel cheered by the coincidence. And then, just the other day, as Season 2 of the excellent Netflix series The Diplomat launched, there was the Vivaldi again, ushering us into a glamorous ambassadorial reception at Blenheim Palace.

This just reinforces what we have known for some time: that in myriad different ways, Vivaldi’s Four Seasons have become one of the most usable, recyclable, familiar

spans, seemingly designed for those not yet into the full-scale concertos of Brahms or Rachmaninov, offering refreshing bursts of attractively energetic music-making. Yet this does not quite explain the phenomenon of the Seasons, and it is worth trying to retrace the modern revival of these remarkable concertos to observe their ever-growing hold on listeners. One interesting context is that in terms of the revival of Baroque music in the 20th century, Vivaldi was comparatively late to the field. Bach and Handel, even Purcell and Monteverdi, were better

Great operas are inextricably linked with their composer but, asks Jessica Duchen, how often do we acknowledge the important role of the librettist?

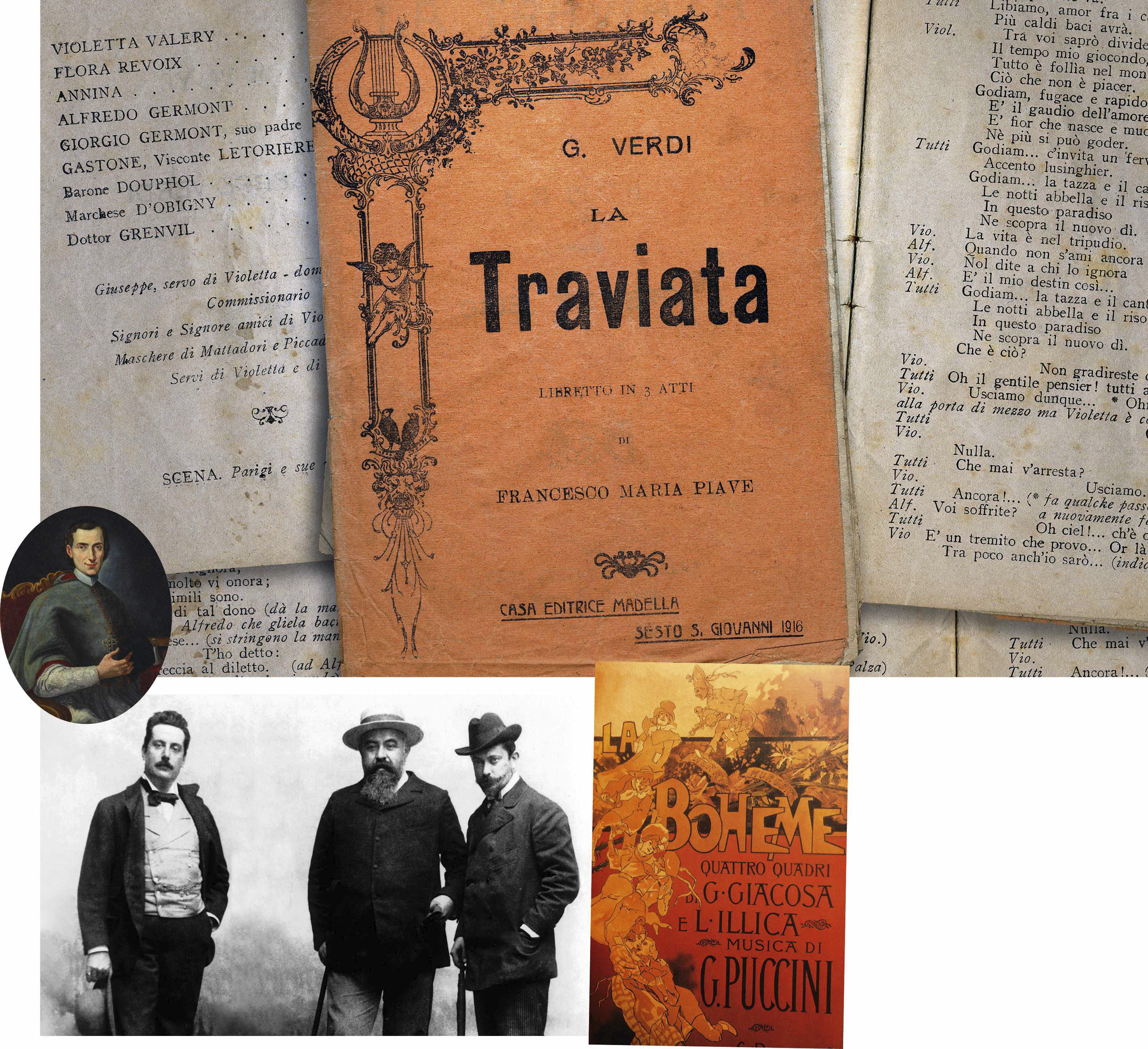

‘Prima la musica, poi le parole.’ First the music, then the words? Oh dear. In opera, the reality is quite the opposite. We tend to credit opera composers ahead of their librettists. But can you imagine Mozart without Da Ponte? Verdi without Piave? Strauss without Hofmannsthal? Our favourite operas, such as Le nozze di Figaro, La traviata or Der Rosenkavalier would be nowhere without their words and their drama – provided by the writer. Composers might grumble, cajole or bully their wordsmiths, but they know on which side their bread is buttered.

A great libretto (the term means ‘little book’) can make the difference between a rare wonder and an opera for the ages. The reason Fauré’s Pénélope is so rarely performed is probably that the libretto places most of the drama offstage. L’elisir d’amore is among Donizetti’s most popular operas possibly because Felice Romani gave him a rom-com of such well-calibrated human truths that it sparked some of his best music. Interestingly, in pop music or musicals the words are often added second to fit the tune, so people assume that’s how operas are done too. It isn’t. Moreover, in musical theatre, a writer creates the book or lyrics, but rarely both. A librettist, conversely, writes ‘a little book’, controlling an opera’s dramatic outline, but usually also the words that are sung.

For today’s new commissions, some opera houses might employ a ‘dramaturg’ to help embed an opera in a convincingly created dramatic world; and if the creative team works with a director from the start, that person has much input in shaping the outcome. But

ultimately, it is up to the librettist first to put a strong dramatic structure on the page, and next to produce concentrated, singable text, with plenty of open vowels and not too many instances of ‘ss’ or ‘th’ (and hopefully not too many of my bugbear, ‘ayshern’ rhymes, as in ‘celebrayshern across the nayshern’). It’s no place for literary flights of fancy, though there are some librettists who never got that email. Long, long ago and far, far away, it was almost possible to be an opera librettist

A great libretto is the difference between a rare wonder and an opera for the ages

full time. Pietro Metastasio (1698-1782) wrote 26-28 librettos which produced around 800 operas. His Adriano in Siria was set, incredibly, by more than 60 composers. Porpora, Caldara, Pergolesi, Galuppi and Cherubini were just a few of those who took up his work, and even Mozart used a Metastasio libretto – La Clemenza di Tito – though by that time operatic fashions had evolved, and it required substantial tweaking. Most librettists, however, have had ‘portfolio’ careers. Metastasio’s colourful existence was outshone by that of Lorenzo Da Ponte, librettist for Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro, Don Giovanni and Così fan tutte. His life rip-roared through priesthood and academia in Italy, a stint in Vienna, and ultimately New York, where he

‘Little book’: (above) Verdi’s copy of Piave’s libretto for La traviata; (left) the triple team of Giacomo Puccini and librettists Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa, c1893; a poster for their opera La bohème; (far left) Mozart’s librettist for Figaro and Don Giovanni, Lorenzo Da Ponte

opened a grocery store. His three librettos for Mozart fed upon Beaumarchais’s plays, the advice of Casanova (who lent a ring of authenticity to Don Giovanni ) and possibly, for Così, the composer’s own relationships with two sisters, Aloysia and Constanze Weber. In 1787 he created three libretti simultaneously for three different composers. He related in his memoirs that he had the help of a box of snuff to one side, a bottle of Tokay to the other, and, in between, his landlady’s 16-year-old daughter…

Ideally these working relationships are a marriage of true minds. You would think that was essential. The nuances, however, are deeper and more complex. Try Giuseppe Verdi and

Composer of the Week is broadcast on Radio 3 at 4pm, Monday to Friday. Programmes in February 2025 are:

3-7 February Meyerbeer

10-14 February Garcia

17-21 February Britten

24-28 February The Turkish Five: Saygun, Erkin, Rey, Alnar, Askes

Melody Possibly the best-known of all Gluck’s airs, ‘Che farò senza Euridice’ in Orfeo ed Euridice epitomises the natural, disarming simplicity that was the essence of the lyrical ideal for which he strove. A single exaggeration in performance, he insisted, would kill its effect.

The chorus In Baroque opera, the chorus was largely confined to expressions of rejoicing at the end of the final Act. Following the example of classical Greek theatre, for Gluck it was there to function as both commentator and participant –whether gracing the Elysian Fields or terrorising the underworld.

Scoring Berlioz (pictured below) was a great admirer of Gluck’s orchestration, not just for its sonorities but also for his use of the orchestra to hint at truths beyond the literal text.

The French composer quoted Gluck extensively in his landmark treatise on orchestration, and particularly relished the inventiveness of Iphigénie en Tauride’s piccolo-to-trombone enriched palette.

The overture Gluck was determined to incorporate the overture into the overall dramatic scheme. Though he failed to do so in Orfeo, by the time of Alceste five years later, he achieved his goal, setting the scene with a brooding, atmospheric D minor tone-poem-inminiature that proved a template for the ‘reform’ works that followed.

Paul Riley traces the wandering existence of a cosmopolitan composer who made it his life’s work and ambition to rip up opera’s rulebook

ILLUSTRATION: MATT HERRING

Bavarian by birth; Bohemian by upbringing; and acquiring extra musical polish in Italy, where the Milan-based Sammartini kept a watchful (if informal) eye on him, Christoph Willibald Gluck was the ultimate cosmopolitan. An inquisitive go-between straddling the operatic gulf between Italy and France, he later proclaimed that he’d established ‘a universal language of music for all nations… abolishing the ridiculous distinction between national styles in music’. Abolished? Or, more properly, reconciled? Thereby hangs a tale as nuanced as that of his greater claim to fame as a trailblazing pioneer of operatic

much-plundered text attracted composers including Vinci, JC Bach and Thomas Arne – indeed, it would still be going strong into the 19th century, by which time the libretto had notched up nearly 100 settings. A bold decision, but a piquant one too. Metastasio, a mainstay of Gluck’s output over the next couple of decades, was no fan, describing the composer’s La Semiramide riconosciuta (1748) as ‘archvandalian music’. More crucially, he also represented the embodiment of ‘opera seria’, whose rigid conventions such as the da capo aria (with its action-stalling repeat of the first section) would find themselves a target of Gluck’s reforming zeal.

Gluck proclaimed that he had established ‘a universal language of music for all nations’

reform – a case of ‘back to the future’, if ever there was one.

Musically inclined from a young age, Gluck had no wish to follow in his father’s footsteps as forester or water bailiff. Barely into his teens, he jumped ship and decamped to Prague, where the city’s flourishing musical life only served to confirm him in his ambitions. Vivaldi was one visitor who impressed him and, via Vienna, in 1737 Gluck fetched up in Milan where he could experience what Italian music had to offer at first hand. Officially in the employ of Prince Melzi, he honed his skills in instrumental composition. Opera, however, was the prize for anyone out to cut a dash, and with Artaserse, premiered in 1741, he staked his claim. It was a bold choice. The story, about the ancient Persian king, was a popular one, and the Italian poet Metastasio’s

All that lay in the future. In the meantime, Gluck had been invited to London in 1745 to be ‘house composer’ at The King’s Theatre in the Haymarket. Despite its temporary closure due to the the Jacobite uprising, during his tenure Gluck managed to stage two new operas of his own plus works by Galuppi and Lampugnani. Moreover, he met Handel, whom he described as ‘that most inspired master of our art’ and reverentially hung a portrait of ‘il caro Sassone’ in his bedroom for the rest of his life – ironically so, since the master of ‘opera seria’ did not return the compliment, reportedly observing that his cook knew more about counterpoint than Gluck. London nevertheless furnished the counterpoint-lite composer with two game-changing revelations: prioritising intimacy and nuance, the voice of

Here we are celebrating the 300th anniversary of The Four Seasons on our cover, and a new benchmark recording comes along! Théotime Langlois de Swarte’s effervescent take on Vivaldi’s classic (see opposite) is reason enough to spend some time reacquainting yourself with a work you think you’ve heard all there is to hear of. The same might be said of Bach’s Cello Suites, so do seek out Giovanni Sollima’s new survey (see Instrumental). We’ve also got a Messiah and a ‘Death and the Maiden’ this month, not to mention a legendary recording of La bohème in Andrew McGregor’s archive round-up. Beyond that, we take a trip back to Wolf Hall in my own round-up of Screen gems, where Nosferatu also bares its teeth. And if you think you’ve heard it all, how about Rameau meets ABBA? Michael Beek Reviews editor

This month’s critics

John Allison, Nicholas Anderson, Michael Beek, Terry Blain, Kate Bolton-Porciatti, Geoff Brown, Michael Church, Christopher Cook, Martin Cotton, Christopher Dingle, Misha Donat, Jessica Duchen, Rebecca Franks, George Hall, Malcolm Hayes, Claire Jackson, Michael Jameson, Berta Joncus, John-Pierre Joyce, Nicholas Kenyon, Erik Levi, Natasha Loges, Andrew McGregor, David Nice, Freya Parr, Ingrid Pearson, Jeremy Pound, Steph Power, Anthony Pryer, Paul Riley, Jan Smaczny, Jo Talbot, Anne Templer, Kate Wakeling

KEY TO STAR RATINGS

HHHHH Outstanding

HHHH Excellent

HHH Good

HH Disappointing

H Poor

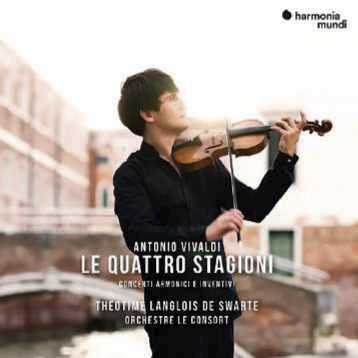

Kate Bolton-Porciatti is kept on the edge of her seat by Théotime Langlois de Swarte’s compelling recording of Vivaldi’s classic

The Four Seasons; Violin Concerto in E major; Concerto for Strings and Solo Violin in G minor; Aria from Nulla in mundo pax sincera* etc; plus works by Lambranzi and Gentili *Julie Roset (soprano); Orchestre Le Consort/Théotime Langlois de Swarte (violin) Harmonia Mundi HMM902757.58 90 mins (2CD)

If your heart sinks at the thought of yet another recording of Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons, read on: this one is so compelling it will have you on the edge of your seat, as will the companion works on this exhilarating new album. French violinist Théotime Langlois de Swarte is one of the brightest young things on the early music scene today and here we’re treated to

a triple helping of his versatile talents as he takes on the roles of soloist, arranger and director of the period-instrument ensemble Orchestre Le Consort. We’re also treated to a ‘second’ Four Seasons : a sequence of Vivaldi’s other concertos and concerto movements, compiled in a way that parallels the keys of the Quattro Stagioni, from the ‘Springtime’ of E major to the ‘Winter’ of F minor – a tonal progression which Swarte sees as a symbolic (and Proustian) reflection on the cycle of life.

Vivaldi may have been ordained as a priest but he was, above all, a man of the theatre – an impresario, opera composer and director – and Swarte’s readings spotlight the drama of his idiom, throwing musical contrasts into high relief. Gutsy orchestral playing gives way to airy ensembles; brooding recitative-like passages to lyrical instrumental arias; improvisatory solo riffs to vigorously rhythmic tuttis. Throughout, the Orchestre Le Consort produces a sound of such transparency that details often stifled in other

performances emerge with glassy clarity – among them, the exquisitely wispy and inventive continuo realisations. The players’ mimetic abilities are also thrillingly theatrical: they summon up twittering birds, murmuring streams, buzzing insects, thunderous storms – and all the other images that Vivaldi sketches in the Seasons ’ prefatory sonnets. Above all, though, it’s Swarte’s solo playing (on a 1733 fiddle by Carlo Bergonzi) that steals the show: pliant, expressive, wild and virtuosic. Particularly admirable is his elastic, almost jazzy flexibility with the music: listen to his discreetly extemporised embellishments; his supple, stream-of-consciousness-like musings (Proustian, again!);

and the fiery spontaneity of his solo violin narrations. He’s the Stéphane Grappelli of period performance.

As well as the concertos, this two-disc set includes the title aria from the Red Priest’s sacred motet Nulla in mundo

Théotime and his colleagues charm and entrance with balletic and acrobatic playing

pax sincera, its serene pastoral melody sung with enchanting candour by Julie Roset, whose dewy soprano has an ingenuous, choir-boy quality. We also hear selections from Venetian composer-cum-ballet master Gregorio Lambranzi’s 1716 collection of romping

Performer’s notes Théotime Langlois de Swarte

Is both playing and directing the ensemble a challenge?

Vivaldi was playing some of the concertos he was writing, and also his students were doing the same. You conduct with the violin, with the sound of the violin and shape the sound with the bow. So it’s really about precision and efficiency of the length of every note. For me it’s quite natural to do it like this, because it’s the way it was meant to be done.

theatrical dances, whose skeletal, single-staff melodies have been fleshed out for this world-premiere recording by Swarte and Vivaldi expert Oliver Fourés. Here courtly, there folksy, they’re the musical equivalent of Pietro Longhi’s genre paintings of Venetian masking and commedia-style cavorting. Swarte and his colleagues charm and entrance with playing by turns balletic, by turns acrobatic. Finally, the players take their bow with a filigree Adagio from a Trio Sonata by Vivaldi’s fellow violinist, Giorgio Gentili –another unknown gem, and one of such vaporous beauty it will leave your sinking heart floating on clouds.

PERFORMANCE HHHHH

RECORDING HHHHH

Tell us about the programme choices beyond the Seasons… I wanted to create a cycle after The Four Seasons, to show the rebirth after ‘Winter’. For me ‘Winter’ is a symbol of death, but after that there is the possibility to start over. The cycle has the same tonalities – E major, G minor, F major and F minor, and the same symbolism. So we tried to recreate the atmosphere of the seasons with different concertos, but also explore the different impressions of Vivaldi; they are works he composed in different moments of his life. The aria is a very important piece for me because I listened to it so much as a child; so it’s about my childhood, but it’s also the same tonality as ‘Spring’.

Are there still discoveries to be made in a work as ‘familiar’ as The Four Seasons?

Yes, completely! I discovered, before writing the booklet, that the second movement of ‘Winter’ is actually about deference to God and prayer. And just two days ago I noticed that there’s a motif from Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier in the first movement of ‘Winter’! I’m sure Bach knew The Four Seasons, because it was one of the most important works in all of Europe at the time.