FEATURED OUTLAW: BETSY GAINES QUAMMEN

RYAN ZINKE ON THE OUTDOOR EXPERIENCE

WOLVES: HEAR THEM HOWL

CELEBRATING BLACKFEET STORIES

FREE SUMMER 2024

our west

2

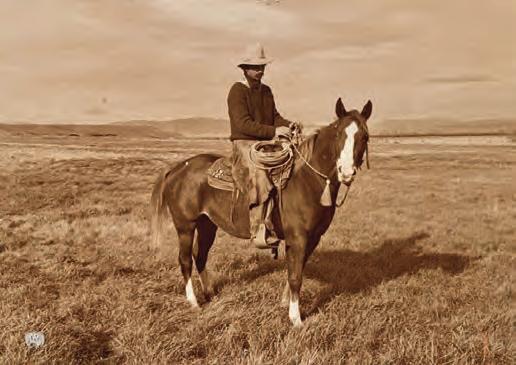

3 KENE SPERRY - FINE ART WWW.KENESPERRY.COM

SCAN TO MEET THE ARTIST

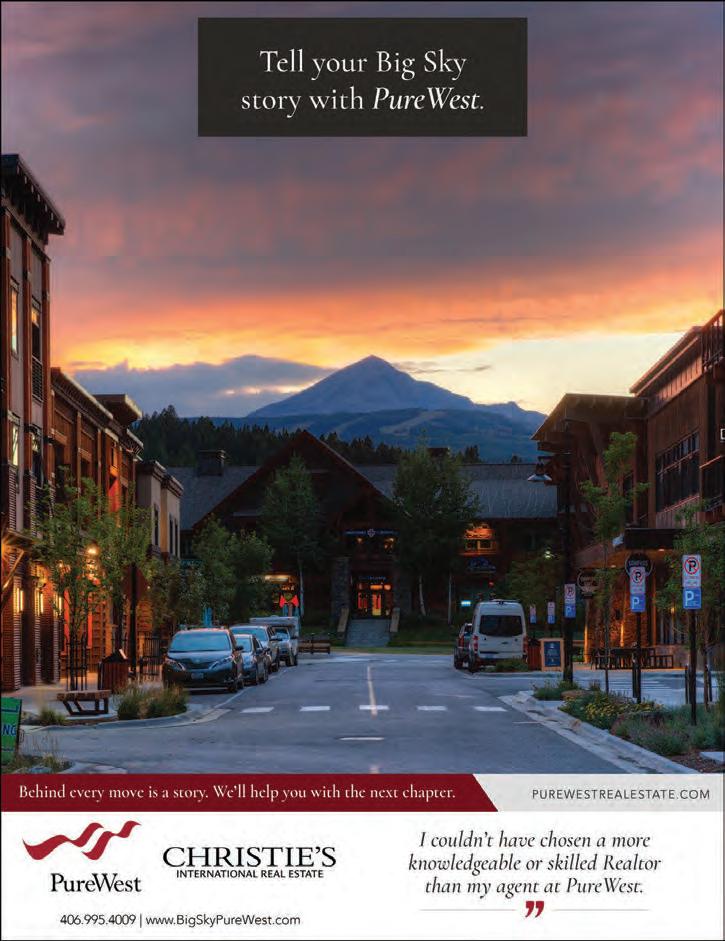

4 406.995.2233 . 145 TOWN CENTER AVE . BIG SKY, MT 59716 . BLOCK3BIGSKY.COM Chophouse . Montana Fare . Whiskey & Bourbon . Hand Crafted Cocktails Big Sky, MT thewilsonhotel.com

5 OUR FLEET, AT YOUR SERVICE www.stajets.com | (844) FLY-STA1

6 EST. 1997 Big Sky, MT bigskybuild.com 406.995.3670 REPRESENTING AND BUILDING FOR OUR CLIENTS SINCE 1997

SCHEDULE YOUR SVALINN RANCH VISIT TODAY.

BRED TO LOVE. TRAINED TO PROTECT.

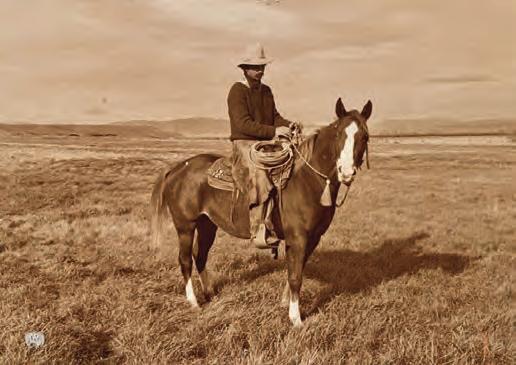

Photo: Ted Wells

46

The River That Reveals Us

The Grand Canyon is in many ways a different experience today for the 29,000 annual river runners than it was when John Wesley Powell braved the unknown corridor in 1869, but one thing that never ages is the reverence this magnificent landscape inspires. Through the lens of her own trip in the Big Ditch juxtaposed by Powell’s, Mountain Outlaw Managing Editor Bella Butler contemplates how immersion in wild spaces can bring us in closer relationship to them, and how the Grand Canyon’s Colorado became The River That Reveals Us.

116

Echoes from the Nitowas

Indigenous peoples have long been the stewards of stories in what is today called the American West. In the Nitowas, the homelands of the Blackfeet, Lailani Upham is carrying on tradition with her business Iron Shield Creative, where her people’s stories are not only protected from oppression’s attempted cultural erosion, but also celebrated and passed on. Writer Chandra Brown shines light on Upham’s effort to honor the Echoes of the Nitowas.

98

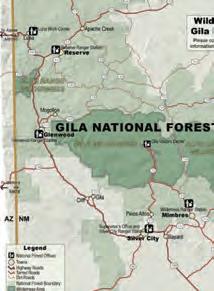

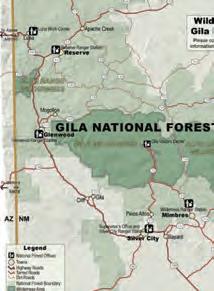

The Gila

One hundred years ago, the United States Congress answered the pleas of a young Forest Service ranger named Aldo Leopold when it designated 755,000 acres in New Mexico as the nation’s first Wilderness. Home to rolling topography, diverse plant and animal species and New Mexico’s only free-flowing river, the Gila Wilderness is a place of inspiration, and for writer and Nuevomexicana LeeAnna T. Torres, it embodies her querencia, her native homeland. In her poignant personal essay, Torres considers what it means to celebrate a place, and how to truly honor The Gila.

9

SUMMER

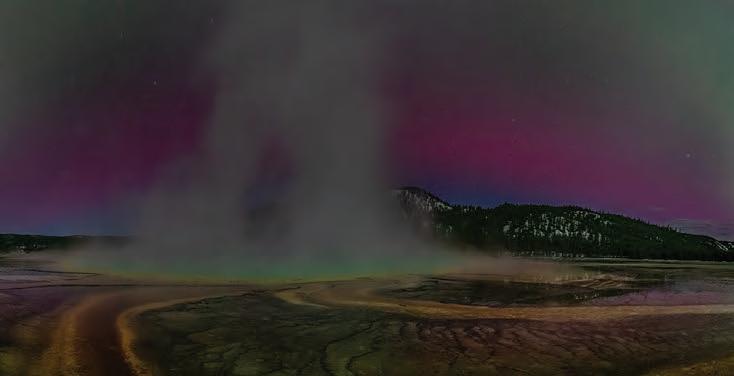

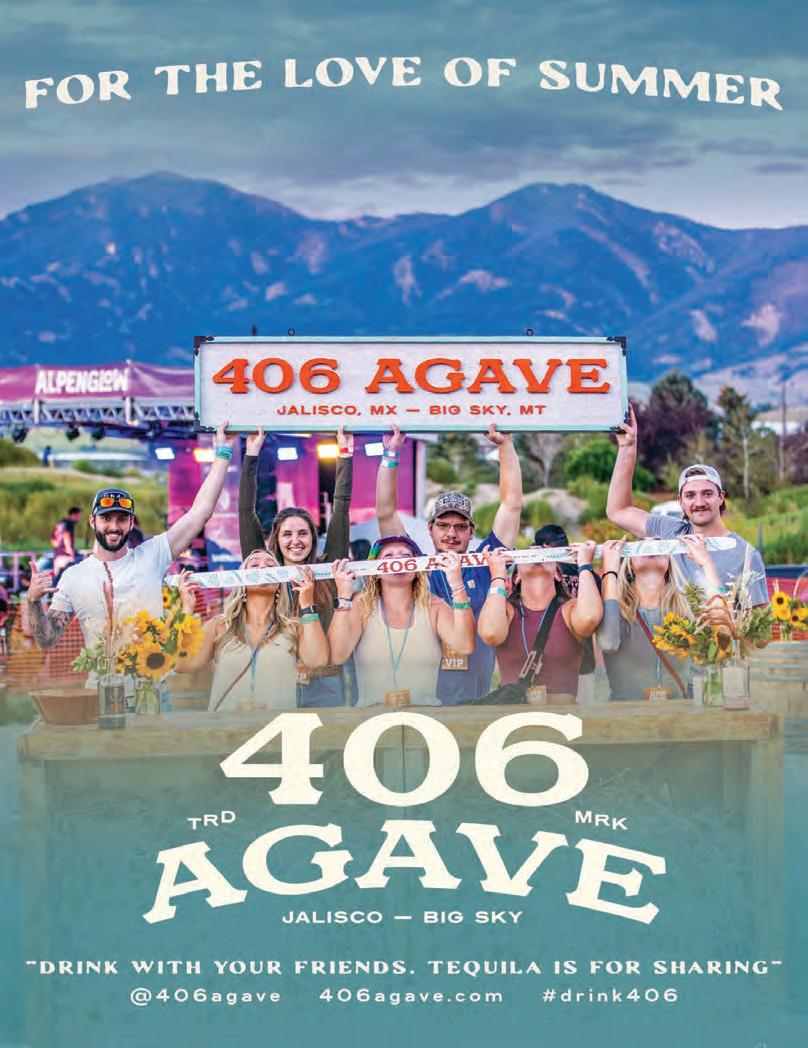

The northern lights at Grand Prismatic Spring in Yellowstone National Park. On May 10, 2024, much of North America was treated to a particularly bright solar storm, sending splashes of color across the night sky in a dazzling aurora borealis. Photo by Paul Holdorf

FEATURES

2024

10

11 YOU DREAM. WE BUILD. BIG SKY | JACKSON TETONHERITAGEBUILDERS.COM “THB HAS ALL THE QUALITIES YOU WANT IN A BUILDER; QUALITY, VALUE, INNOVATION, INTEGRITY, ORGANIZATION, AND PERSONALITY” -REID SMITH ARCHITECTS

DEPARTMENTS

FOREWORD

20 Betsy Gaines Quammen likens the West to a constellation

TRAILHEAD

24 Explore our editor’s picks for all things Mountain West

LOOKING FORWARD, LOOKING BACK

30 Catch up with poignant Mountain Outlaw stories from past issues

OUTBOUND GALLERY

34 Harvest: Viewing our relationship to land through the lens of harvesting food

ADVENTURE

46 The River that Reveals Us Navigating relationship to landscape in the Grand Canyon

52 Artificial Adventures A modern mountain odyssey generated by ChatGPT

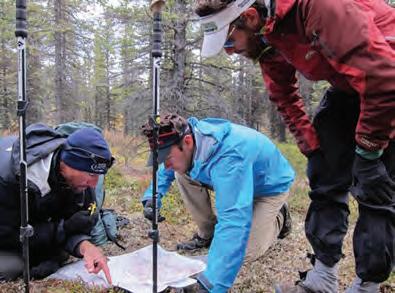

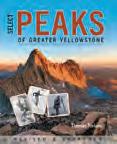

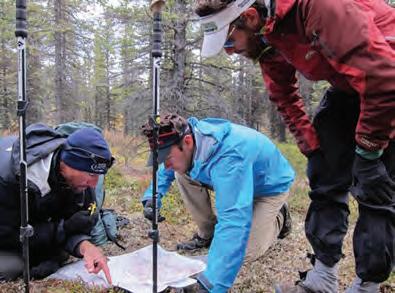

60 Mapping the Wild Within The holy grail of backcountry travel in Greater Yellowstone gets an encore

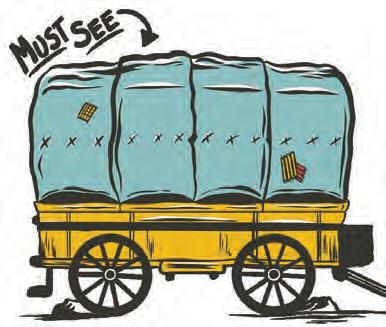

65 King of the Roadtrip An insider’s guide to making the most of your Montana road trip

72 Amplifying Outdoor Narratives BeAlive Studios joins Bozeman’s thriving film scene LAND

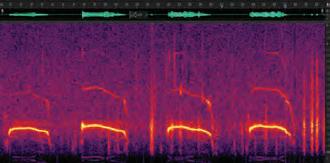

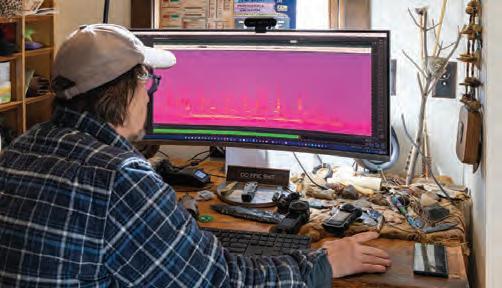

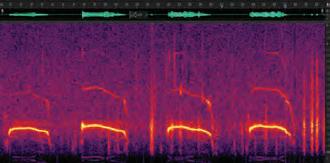

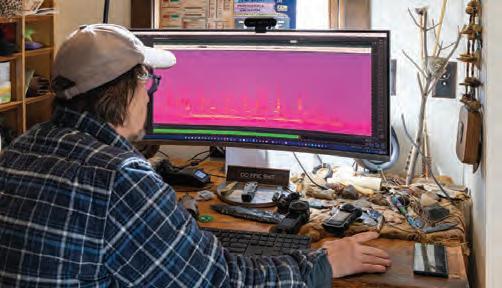

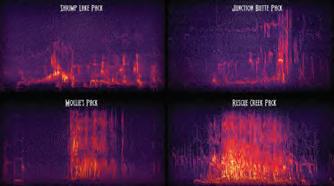

76 Hear them Howl Can understanding how wolves communicate lead us to respectful coexistence?

91 Sustaining the Spirit of Conservation Exploring the region’s history with conservation

98 The Gila Celebrating the centennial of the nation’s first Wilderness through personal narrative

104 The ‘Red, White and Blue Team’ Rep. Ryan Zinke on the outdoor experience

CULTURE

116 Echoes from the Nitowas A Blackfeet storyteller excavates truth through narrative

124 Livin’ in the Arts Through his lyricism, Mike Beck chronicles the life of an artist in the West

132 Funk’s Workshop A Big Fork blacksmith’s cultural imperative to preserve his craft

CREATIVE

138 Poem: Manifest Density Observing the evolution of the West

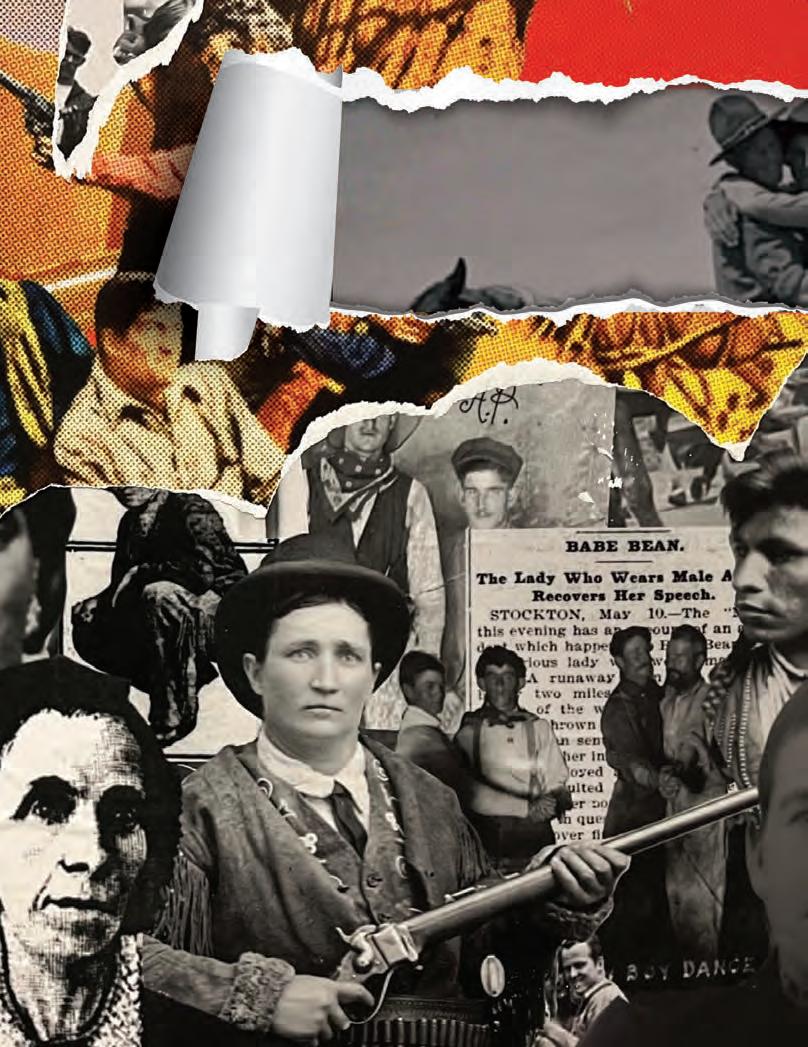

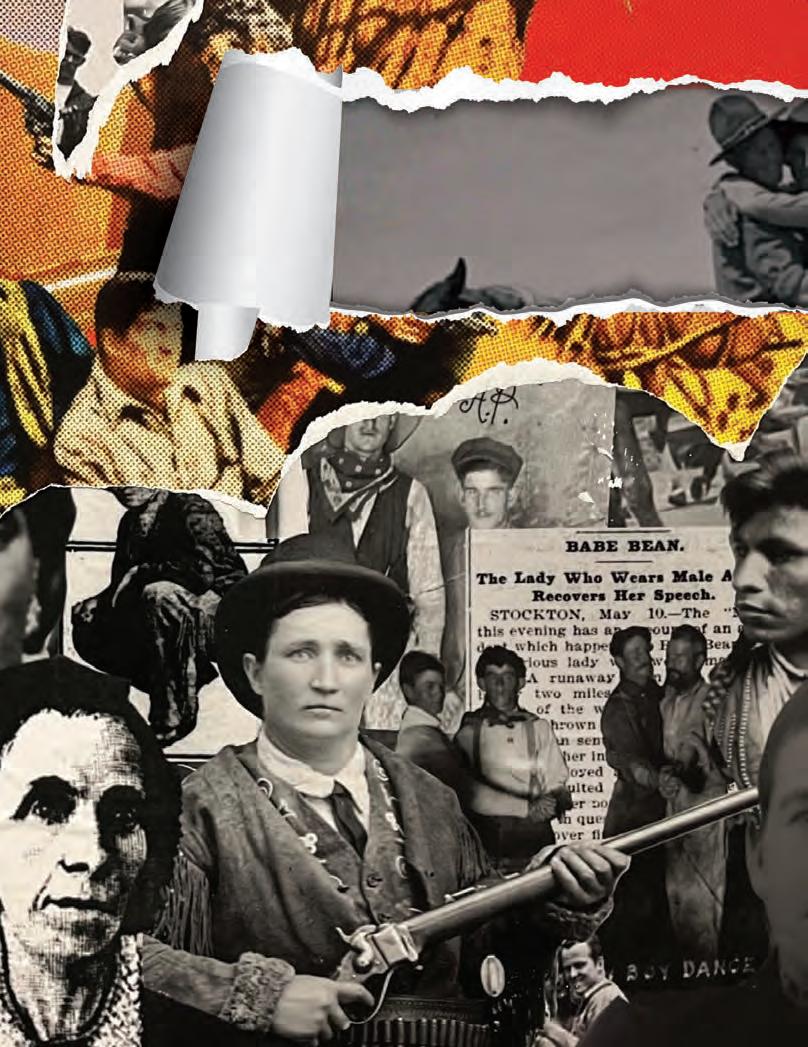

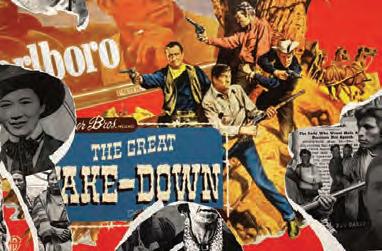

142 Art: Out West Giving a voice to queer perspectives in the mythic West

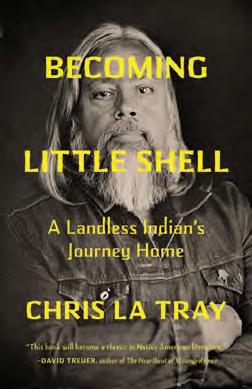

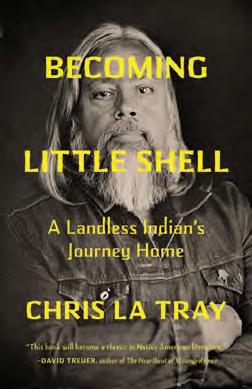

146 The Profane Reverence of Chris La Tray An exploration of identity with Montana’s Poet Laureate

150 Fiction: Blazing Hearts on Rampage Mountain A Western 1940s tale of love in a fire lookout

FEATURED OUTLAW

156 Betsy Gaines Quammen: Finding hope in our collective True West

LAST LIGHT

176 Lighting of the Teepees

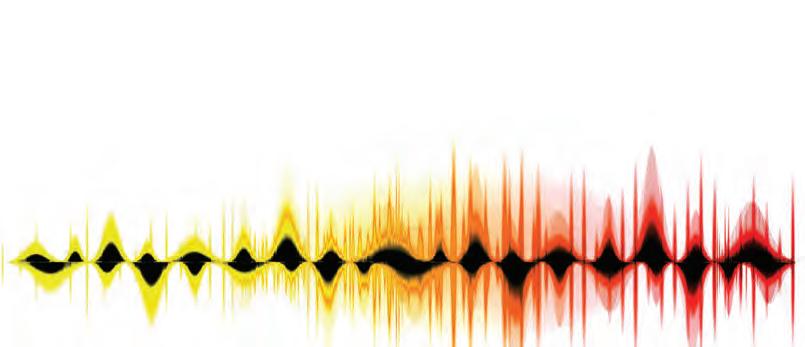

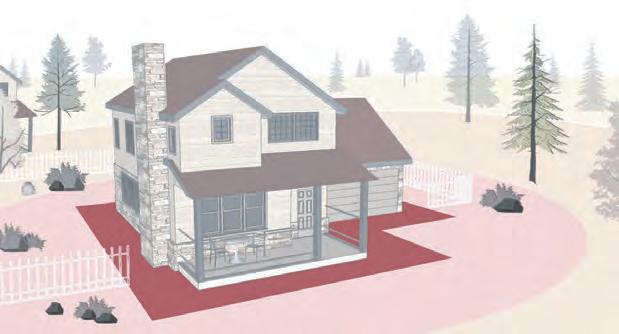

84 Building in a Dichotomy The risks—and solutions—to living in the Wildland Urban Interface 142 52

ON THE COVER

A lesser Bighorn ram bows to his elder. Initially this interaction seemed primed for a violent butting of heads, with both rams sweeping horns back and forth. The smaller of the two made a half-hearted charge, but just before impact lowered his head and placed it gently on the neck of his opponent. Captured along the banks of the Yellowstone River near Corwin Springs, Montana, these rams were only part of a large herd of Bighorns in the valley. A symbol for opposing ideas in the American West, this issue encourages readers to take a step back and seek understanding before butting heads. Photo by Ian Lange

12

104 46 124 116 34 132 98

Your Home, Our Passion

Setting a New Standard in Property & Rental Management

We understand that your home is more than just a property—it’s a part of your legacy. At Big Sky Luxury Vacations & Management, our property and rental management program is designed to maximize rental revenue opportunities while ensuring properties maintain their pristine charm. Our team of professionals handles all aspects of property and rental management from routine repairs and emergency services to keeping your home marketed and booked. With over twenty five years of combined experience, our seasoned staff ensures consistency and reliability in every aspect of our operation. We pride ourselves in offering more personalized experiences for both guests and homeowners, so your property will be a priority, and won’t be lost in the shuffle. Experience transparent billing without hidden fees, and entrust your home to a team dedicated to preserving its luxury and charm. For unparalleled

15

Property

bigskyluxuryvacations.com

property and rental management services in Big Sky, call Jake, Director of

Management, at 855.475.4244.

Owned and published in Big Sky, Montana

PUBLISHER

Eric Ladd

VP MEDIA

Mira Brody

MANAGING EDITOR

Bella Butler

ART DIRECTOR

Robyn Egloff

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

Fischer Genau

CONTENT MARKETING

Taylor Owens

COPYEDITOR

Carter Walker

ART PRODUCTION

ME Brown

Megan Sierra

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS

SALES & ADVERTISING

Ersin Ozer

Patrick Mahoney

ACCOUNTING

Sara Sipe

Taylor Erikson

CHIEF

MARKETING OFFICER

Megan Paulson

CHIEF

OPERATING OFFICER

Josh Timon

VP DESIGN & PRODUCTION

Hiller Higman

DISTRIBUTION

Ennion Williams

Andrew Arena, Julia Barton, Chandra Brown, Lauren Burgess, Maggie Neal Doherty, Liv Hart, Michael Ober, Brad Orsted, Betsy Gaines Quamman, Emily Senkosky, Ednor Therriault, Toby Thompson, Leeanna T. Torres

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS/ARTISTS

Julia Barton, London Bernier, Lynn Donaldson, Jacob W. Frank, Della Frederickson, Jeffery Funk, Dave Gardner, Liv Hart, Halle Hauer, Quinn Taubman Harper, Colin Hislop, Paul Holdorf, Louise Johns, Ian Lange, Bradley Lanphear, Freddy Monares, Cassidy Motahari, Alex Nelson, Kyle Niego, Jim Peaco, Ben Pierce, Emmy Reed, Micah Robin, Chris Sawicki, Kehana Rose, Emily Senkosky, Ethan Schumacher, David Scott, Troy Smith, Jade Snell, Paige Southwood, Blair Speed, Charles Stemen, Madeline Thunder, Kyle Tilleman, LeeAnna T. Torres, Jim Urquhart, Bob Wick

Subscribe now at mtoutlaw.com/subscriptions.

Mountain Outlaw is distributed to subscribers in all 50 states, including contracted placement in resorts and hotels across the West. Core distribution in the Northern Rockies includes Big Sky, Bozeman and Missoula, Montana, as well as Jackson, Wyoming, and the four corners of Yellowstone National Park.

To advertise, contact Ersin Ozer at ersin@outlaw.partners or Patrick Mahoney at patrick@outlaw.partners.

OUTLAW PARTNERS & Mountain Outlaw

P.O. Box 160250, Big Sky, MT 59716 (406) 995-2055 • media@outlaw.partners

© 2024 Mountain Outlaw Unauthorized reproduction prohibited

Check out these other outlaw publications: Subscribe to and read Mountain Outlaw online.

from the publisher

Dear Mountain Outlaw readers,

I would like to personally welcome you to the 28th edition of Mountain Outlaw. Our team of talented editors, writers, graphic designers and staff have created another beautiful publication for your enjoyment in homes and offices around the world. Creating a quality, free magazine in 2024 is no easy task, but we remain committed and thankful for support through our loyal advertisers and subscribers.

As we enter our 15th year of printing this publication, the team has dedicated this edition to sharing stories and tales of Our West. True to the magazine’s founding spirit, you’ll find interesting content and interviews examining lifestyle, culture and relevant issues.

From Montana Rep. Ryan Zinke talking about his passion for the outdoors and conservation policy, to Blackfeet narrative storytelling, wild outdoor adventures and Betsy Gaines Quammen’s concept of True West —there’s something for every ‘westerner’ at heart.

My personal passion for the West, its landscapes, history, people, and tales fascinate me and I’m grateful to have called this home for 50 years. I recently stumbled on Arthur Chapman’s poem that encapsulates my feelings for this region; I will let his words take it from here.

Eric Ladd Publisher

Out

Out where the handclasp’s a little stronger, Out where the smile dwells a little longer, That’s where the West begins; Out where the sun is a little brighter, Where the snows that fall are a trifle whiter, Where the bonds of home are a wee bit tighter, That’s where the West begins.

Out where the skies are a trifle bluer, Out where the friendship’s a little truer, That’s where the West begins; Out where a fresher breeze is blowing, Where there’s laughter in every streamlet flowing, Where there’s more of reaping and less of sowing, That’s where the West begins.

Out where the world is in the making, Where fewer hearts in despair are aching, That’s where the West begins. Where there’s more of singing and less of sighing, Where there’s more of giving and less of buying, And a man makes a friend without half trying— That’s where the West begins.

16

Visit outlaw.partners to meet the entire Outlaw team.

Where the West Begins by Arthur Chapman

featured contributors

LeeAnna T. Torres

The Gila | p. 98

Leeanna T. Torres is a native daughter of the American Southwest and a Nuevomexicana writer with deep Indo-Hispanic roots in New Mexico. She has worked as an environmental professional throughout the West since 2001, which included recovery efforts for the Gila trout. Her creativenonfiction essays have appeared in various print and online publications, and she is most interested in writing that explores where the physical and the Divine intersect.

Brad Orsted Manifest Density | p. 138

Brad Orsted is a Montana-based, award-winning wildlife photographer, conservation filmmaker, author, speaker, poet and wilderness therapy advocate. His work can be seen on the BBC, PBS, Nature, Smithsonian Channel and Nat Geo Wild, as well as in The Wall Street Journal and The Washington Post. Orsted’s memoir, Through the Wilderness: My Journey of Redemption and Healing in the American Wild, chronicles the loss of his daughter, Marley, and his odyssey to find recovery and healing in the sanctuary of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

Chandra Brown

Echoes from the Nitowas | p. 116

Chandra Brown is a writer, river guide and educator originally from Alaska. She has worked within the realm of river conservation since her 2010 Fulbright grant to Ecuador. She is the founder and director of Freeflow Institute, an arts organization that seeks to connect humans to their environments. Brown worked as senior editor at Camas magazine, and her writing has been featured in Adventure Journal, The Dirtbag Diaries, Patagonia, Bomb Snow and Kayak Session magazine, among other publications. Brown, her sweetheart and their two canine roommates are home-based in Missoula, Montana.

Liv Hart

Out West | p. 142

Liv Hart is a multi-disciplinary artist, designer and storyteller currently based in Brooklyn, New York. She focuses her practice in the realm of activism—pertaining particularly to queer rights and histories—and experiments in both tactile and digital formats to uncover and relay stories. When she's not in the studio, she enjoys skiing, traveling, and playing guitar.

Maggie Neal Doherty

The Profane Reverence of Chris La Tray | p. 146

Maggie Neal Doherty is a freelance journalist, opinion columnist and book critic. Her work has appeared in The Guardian, The Washington Post, LA Times, SKI, High Country News and more. Since 2018 she's penned "Facing Main" for the Flathead Beacon. She lives in Kalispell, Montana with her family, and when she isn't skiing or rafting you'll find her with her nose in a book.

Dave Gardner

Harvest & Echoes from the Nitowas | pp. 34 & 116

Dave Gardner is an adventure and lifestyle photographer based out of Montana. Whether it’s a swamp in Arkansas, a river in Idaho or somewhere deep in the mountains, Gardner loves to use his camera to tell stories of wild people in wild places. If he’s not on the road working to fund his next adventure, he's probably out hunting, on a river somewhere, or eating tacos with his fiancé and their dog, Lou.

17

ONLY 6 RESIDENCES REMAIN!

2-3 BEDROOM FLOOR PLANS

RANGING FROM 1,600-2,300 SQFT

BESPOKE LIVING IN DOWNTOWN BOZEMAN

Discover the breathtaking masterpiece that is Wildlands, where the building has crossed the finish line and is truly spectacular. With only 6 residences remaining, now is the perfect time to schedule a tour and experience the unmatched living experience in Downtown Bozeman, Montana that Wildlands has to offer.

18

WWW.WILDLANDSBOZEMAN.COM | 406.995.2404 Scan the QR code to visit the website for floor plans, virtual tours, and more.

19 1565 Lone Mountain Trail, Big Sky, Montana www.acehardware.com | www.acebigskytools.com | (406) 995-4500 The helpful place in Big Sky with the T ls you need and the T s you want.

FOREWORD:

THE TRUTH OF THE WEST IS A CONSTELLATION

By Betsy Gaines Quammen

Editor’s Note: This issue was largely catalyzed by the concepts in Betsy Gaines Quammen’s 2023 book True West: Myth and Mending on the Far Side of America. Read more about Gaines Quammen, this issue’s Featured Outlaw, on p. 156.

Those of us who live here, and those who come to visit, all have versions of the West. In a place fixed by inescapable myths—unbridled liberty, pristine wilderness, rugged individualism, cowboy heroics, blank slates, “conquered spaces,” endless resources, and enduring frontier—we all see this place a little differently. The real West is a shimmering collage.

Over the last few years, I have gone from my home in Bozeman to find whether there is a “true” West. It has taken me to the grasslands of Wyoming, lands lonely for bison; to Colorado’s San Luis Valley, still home to families that have lived there since they obtained Spanish land grants; to eastern Montana plains, punctuated by badlands that made early European settlement brutal and often impossible; to posh restaurants, bathed in mountain alpenglow, that cater to monied second-home owners in Ketchum, Big Sky and

Telluride. I’ve also talked with members of various tribes about land, sovereignty and ongoing acts of resistance as these cultures celebrate long-held traditions; and I’ve spoken with conservationists waging battles against developers and mining companies.

As a region of landscape once traversed by galloping horses, then oxen pulling Calistoga wagons, then coal-fueled trains, and now Sprinter vans, the West continues to change. COVID-19 refugees seeking medical freedoms or the rumored palliative effects of desert and mountain air flooded old mining, ranching and sawmill towns. The ongoing onslaught of wealthy come-latelies seeking wilderness enclaves made it ever more difficult for working class people, and even professionals, to buy homes and afford to live in towns like Bozeman. Christian nationalists, lured by notions of religious homeland, separatism and hyper-freedom, stepped in to walk elbow-to-elbow with recreationists, drawn to the Northern Rockies to shred, slay and rip lands inhabited by elk, wolves and grizzlies.

People are building versions of truth on altars tumbling to pieces, without understanding the full picture, the

A Western night sky illuminates the landscape surrounding Devil’s Tower in Wyoming, known as Bear Lodge to many Northern Plains tribes, for which this geologic feature is sacred. Like this sparkling array of stars, author Betsy Gaines Quammen writes that the “truth of the West is a constellation.” Photo by aheflin/Adobe Stock

true West—the limits of land, vulnerable people, unique cultures and a history of colonization with its ongoing legacy of extraction. We are asking too much of this place. It is imperative to see the West as a fragile collection of livelihoods, expectations, economies, misunderstandings, ecologies, histories and cultures, all playing out (and competing) amid high-cragged mountains, glacier-scraped valleys, hogback ridges, rutted arroyos, sage-whiskered rangelands, wetlands, and booming towns beside those gone bust. These places show the marks of mistakes, heartbreaks and wounds, even as they retain (to varying degrees) their splendors. We need to understand each piece of the West before we comprehend the whole. The truth of the West is a constellation.

Betsy Gaines Quammen is a historian and writer. She received a PhD from Montana State University where she studied western history and early Mormon ideology. She is the author of American Zion: Cliven Bundy, God, and Public Lands in the West and True West: Myth and Mending on the Far Side of America. Betsy lives in Montana with her husband, writer David Quammen, two giant dogs, a sturdy cat and a lanky rescue python.

22 Big Sky Medical Center Big Sky Resort BASE Community Center Roxy’s Market Big Sky Events Arena Big Sky Golf Course

23 Unconditional Advice. +1 406.556.8200 | bitterrootcapital.com | 118 E Main Street, Bozeman, MT 59715

TRAILHEAD

By Fischer Genau

399: Queen of the Tetons

Conservation efforts have brought grizzly bear populations back from the brink in the West, but their increased presence has led to more human-bear encounters and raised the question of how to coexist with these symbols of the wild. This PBS film follows Grizzly 399, the most famous and photographed bear in Grand Teton National Park, as she raises her four cubs. But with increased pressure from climate change and human encroachment, her plight has come to exemplify the clash between humans and the wild. With the potentially imminent removal of grizzly bears from the Endangered Species List—which would make hunting them legal—this documentary tells a story of hope and heartbreak for the Queen of the Tetons. 399film.com

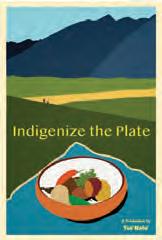

Indigenize the Plate

What sustains a culture? For Natalie Benally, a Diné woman from the Navajo Nation in New Mexico, it’s food. In Indigenize the Plate, a film from Tse’Nato’ and Visionmaker Media, Benally wrestles with how climate change and other modern factors have impacted her own cultural community’s ability to grow their own food, and in response she journeys to a Quechuan community in Peru to learn how its people have addressed the effects of climate change, resource extraction and water displacement in their own food system to sustain their Indigenous culture. Indigenize the Plate reminds us that even across continents, intrinsic human values like food can connect us, and we have much to learn from the things we hold in common. tsenato.com/itp

Browse all Trailhead features online

24

Virginia City: Exploring the Historic Demise of Henry Plummer

In 1863, now-Montana ghost town Virginia City was booming. Gold was discovered around nearby Alder Creek and within weeks, thousands of prospectors were flooding in to chase their fortune, bringing with them money, crime and the eventual demise of one Henry Plummer. Plummer was the sheriff of nearby Bannack, but before becoming a lawman he’d frequently found himself on its other side. He was convicted of second-degree murder in Nevada City, California, where he’d lived as a miner and rancher, and spent two years in San Quentin before he was pardoned for good character and civic performance. But soon after, he killed another man attempting a citizen’s arrest, and left California so as not to risk more jail time.

Shortly after Plummer’s arrival in Montana, and his subsequent election as sheriff, the rate of robberies and murders in Alder Gulch increased significantly. People in Virginia City, whose gold was being robbed from trains as they ferried it back from the frontier, grew suspicious of Plummer and his alleged gang “the Innocents,” and formed a posse of vigilantes to bring the thieves to justice.

After capturing one of them and eliciting a confession where Plummer was named ringleader, the vigilantes arrested the sheriff and hung him from his own gallows, ending the lawman’s tale on the end of a rope.

People can visit Virginia City today almost as it was in the days of Henry Plummer and be called back to the Wild West of outlaws and vigilante justice.

virginiacitymt.com

Yellowstone Highway Turns 100

This summer, the Wind River Scenic Byway is throwing its hundredth birthday party. This 34-mile stretch of the Yellowstone Highway wends its way through Wyoming’s Wind River Canyon, following the Bighorn River as it passes by Boysen Reservoir and under jagged stone pillars thrust up from the riverbed. Carved out of the rock in 1924 by 450 men with dynamite and steam shovels (several of whom lost their lives in the effort), this historic passage gives the modern-day explorer a glimpse into the West’s rugged past.

windriver.org/experience/driving-tours/ old-yellowstone-highway/

25

MT ID UT CO ND SD WYOMING ● SHOSHONI ● CASPER ● THERMOPOLIS YELLOWSTONE NATIONAL PARK ● GRAYBULL ● CODY WIND RIVER SCENIC BYWAY CHEYENNE ✪ THE YELLOWSTONE HIGHWAY 1924 2024 MONTANA ● VIRGINIA CITY

TRAILHEAD

Sponsored Content

Le Creuset's Alpine Outdoor Collection

The crackle of an open fire; the scent of wood smoke; the freedom of wide-open spaces. Though you won’t find any of these on an ingredient list in a recipe, they infuse food with a special kind of flavor that makes cooking outdoors essential to any good summer routine. Le Creuset's new Alpine Outdoor Collection celebrates this blend of nature and cuisine, offering three products designed to enhance outdoor cooking adventures: the Alpine Outdoor Skillet, the Alpine Outdoor Square Grill Basket and the Alpine Outdoor Pizza Pan for mouth-watering, versatile outdoor meals. All pieces in the Alpine Outdoor Collection are crafted from rugged enameled cast iron specifically designed for cooking over an open flame, and raised loop handles make them easy to carry or maneuver on grates. Plus they all come ready-to-use, are easy to clean and require no seasoning. When you’re ready for an outdoor adventure this summer, your cookware will be too with Le Creuset. lecreuset.com/alpine-collection

Magic Mind

Many of us can’t imagine our mornings without a cup of coffee. But what if we could enjoy its benefits—energy and alertness—without adverse effects like higher stress and trouble sleeping? Magic Mind’s mental performance shot is designed to be a new morning ritual, one that enhances focus and thinking, boosts mood and motivation, and creates a calm, sustained energy without the drawbacks of other caffeinated drinks. Using ingredients like lion’s mane mushrooms, matcha, turmeric, and immunity-boosting vitamins like C, D and Echinacea, Magic Mind has distilled mental endurance and precision and bottled it for human consumption. magicmind.com

Thinking Like a Mountain by Aldo Leopold

Aldo Leopold, conservation icon, philosopher, writer and woodsman, is best known for A Sand County Almanac, his loving, granular account of the ecology of his Wisconsin homeland. But he spent many of his early years as a ranger roaming the American West, where he traveled hundreds of miles on horseback, bow hunted wolves and eventually proposed designation of the first wilderness in the U.S., as further explored this issue in “The Gila” (p. 98).

In his 1949 essay “Thinking Like a Mountain,” Leopold describes the death of a wolf he shot with his companions, and the “fierce, green fire dying in her eyes.” Seeing that light go out, Leopold glimpsed something “known only to her and the mountain,” and it helped him see nature as an interdependent web where violence, beauty and death are inherent in life. This realization helped shape his subsequent work in conservation, and “Thinking Like a Mountain” reminds us that what is wild is essential, or, as Leopold quotes from Henry David Thoreau, “In wildness is the salvation of the world.” aldoleopold.org

26

Save Wild Trout

Wild trout populations in some of Montana’s famed rivers have sunk to historic lows in the last year, endangering fisheries as well as the millions of dollars brought in by anglers. Save Wild Trout, a coalition of anglers and river advocates concerned about their watershed, are investigating causes for wild trout population collapses in the Big Hole, Ruby and Beaverhead rivers, and they’re working to raise public awareness and develop sciencebased solutions. For them, wild trout populations are the canary in the coal mine of ecological threats facing Montana, and they encourage everyone to act before it’s too late to restore its cold-water fisheries. savewildtrout.org

Death in the West

Death in the West is a true-crime podcast, but it has more to it than grisly murder and daring heists. Its first season tells the story of Frank Little, a union organizer who was dragged from his bed in the dead of night and murdered in Butte, Montana, in 1917, a death that went unsolved for 100 years. In its second season, this history podcast continues its work exploring “the American West’s strange crimes and unsolved intrigues.” deathinthewestpod.com

The Modern West

The range of topics explored by Wyoming Public Media’s The Modern West reflects the richness of Western culture and its history: a tribe’s fight to bring healthcare onto the reservation; presentday cowboys responding to climate change; the most expensive fire in Colorado history. Each season invites listeners to engage with the story of the modern West as they live it. www.themodernwest.org

Browse all Trailhead features online

27

“For us, it’s not just about nailing it. It’s about channeling the true vision of a

– Cory Reistad |

406.586.5593 | welcome@savinc.net SAV DIGITAL ENVIRONMENTS Innovative Luxury Technology Systems

project, rising above challenges, and never cutting corners.

SAV Digital Environments

Photos by Audrey Hall

“WE’LL KNOCK OUT YOUR FLOORS IN 1 DAY” koconcretecoatings.com SCAN HERE FOR MORE INFO

By Fischer Genau

If there's one thing we know after more than a decade of covering the American West, it's that stories don't end. When an article goes to print, the lives and issues it presents live on. With that in mind, our editors revisited three past Mountain Outlaw articles to catch up with important subjects in the Mountain West.

2067: The Clock Struck Thirteen, Winter 2017

THE BACKGROUND:

Mountain Outlaw contributor Todd Wilkinson’s 2017 alarm-bell piece, 2067: The Clock Struck Thirteen, transported readers to a plausible dystopian future in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem in the year 2067, where climate change has converted snowy winters of lore to rainy, 60-degree Februarys.

THE UPDATE: Seven years after Wilkinson penned this article, and only 43 years away from 2067, a dismal snow year is the talk of the Greater Yellowstone Area. The Greater Yellowstone Climate Assessment, published in June 2021, projects a more-than 5-degree warming by the year 2100, as well as a 9 percent increase in precipitation yet 40 percent loss of snowpack. These numbers begin to render Wilkinson’s story as prophecy. Yet, other updates are cause for hope. Some of the region’s organizations with large footprints have made efforts, as demonstrated through Big Sky Resort’s pledge to achieve zero carbon emissions by 2030, and smaller green businesses are adding to the work through sustainable waste management and transportation. Climate change advocacy is also making waves in the judicial branch of government, with the 2023 triumph of 16 youth plaintiffs in their lawsuit against the state of Montana for its violation of their constitutional right to a clean and healthful environment.

30

An Economic Crossroads, Winter 2018

THE BACKGROUND:

In Mountain Outlaw’s Winter 2018 issue, contributor Claire Cella examined rapid population growth in mountain towns across the West, exploring both the opportunities as well as challenges such growth poses, including lack of affordable housing. At the time, Bozeman, Montana, was growing at a rate of 2-3 percent annually.

THE UPDATE: Population growth has tracked steady since Cella’s report; Bozeman’s population jumped more than 8.5 percent between 2020 and 2024. Big Sky Country MLS reported the median single-family home sale price in Bozeman’s Gallatin County at $749,900 in March 2024, a more-than 56 percent increase from March 2020. The trend is comparable for the state of Montana as a whole. In 2022, Montana Gov. Greg Gianforte responded to this issue by appointing a bipartisan housing task force, which helped pass a spate of bills that make it easier to construct new housing. Bozeman, as well as its parallels like Kalispell, Montana, and Jackson, Wyoming, still struggle to keep up with demand, evidenced through increasing urban camping and houseless communities. Side-by-side headlines reporting record-high real estate prices and affordable housing crises continue to tell Cella’s story today.

Gunfight, Summer 2022

THE BACKGROUND:

In our Summer 2022 issue, Mountain Outlaw profiled former firearms executive and author Ryan Busse. In a discussion centered on his 2021 memoir Gunfight, Busse criticized the role the gun industry plays in the nation’s increasing divisiveness, lent numbers to growth of gun sales in the U.S. and emphasized the relationship between freedom and responsibility.

THE UPDATE: Busse announced his bid for Montana governor in February 2024, challenging incumbent Gov. Greg Gianforte. A freshman in politics, Busse’s platform is founded on responding to the climate crisis, protecting and expanding voting rights, freedom of choice and responsible gun policy. Gun sales in the U.S. continue to hit record highs, with 2020-2023 comprising the four highest years on record since the FBI began tracking these numbers in 1998.

31

995 Settlement Trail, Big Sky MT | 406.993.4140 montage.com/bigsky | @montagebigsky Elevated Mountainside Retreat | Five Distinctive Dining Experiences Breathtaking Views | Full-Service Spa | Unforgettable Moments ESCAPE THE ORDINARY with Montage.

33

Cortina

Backcast

Alpenglow FEATURED DINING OUTLETS

Beartooth Pub & Rec.

gathers the last cut of the season at J T Ranches in Montana’s Flint

Valley. After a large swath of historic working lands were subdivided and sold in the region, Hilmo and Joleen Meshnik knitted over 680 acres back together, and thanks to a 2018 conservation easement, the land will be protected in perpetuity.

Tim Hilmo

Creek

Photo by Dave Gardner

OUTBOUND GALLERY

The concept of Harvest has been the bedrock of every version of the West. At its best, growing, foraging and hunting food in this region has been a means through which to come into relationship with the land; it can be a practice of reciprocity and an opportunity to “sustain the ones who sustain you,” as Potawatomi botanist and author Robin Wall Kimmerer writes. Even as a value we hold in common, harvest takes many shapes in the West. Through the lenses of a cohort regional photographers, this issues Outbound Gallery seeks to reveal some of these forms, and introduces the animals, landscapes and people who mold them.

“Know the ways of the ones who take care of you, so that you may take care of them. Introduce yourself. Be accountable as the one who comes asking for life. Ask permission before taking. Abide by the answer. Never take the first. Never take the last. Take only what you need. Take only that which is given. Never take more than half. Leave some for others. Harvest in a way that minimizes harm. Use it respectfully. Never waste what you have taken. Share. Give thanks for what you have been given. Give a gift, in reciprocity for what you have taken. Sustain the ones who sustain you and the earth will last forever.”

–Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass

Gallery Curated by Fischer Genau

Neeleman of Ballerina Farm in Kamas, Utah, milks the family cow as two of her children keep a vigilant watch for the family’s notorious goose, who is known to take her job of protecting the chickens a bit too seriously. Neeleman and her husband, Daniel, raise Berkshire pigs and Angus cattle on their farm while also raising a brood of their own—they have eight children, the youngest born this January, and 8.9 million people on Instagram keep up with their lives on the farm. Photo by Paige Southwood

36

Hannah

Above: Susan Sekaquaptewa’s home garden is seen within the surrounding desert landscape in Second Mesa on the Hopi Reservation. Sekaquaptewa explains that growing food is a traditional Hopi way of engaging in relationship with the land. It can be both a spiritual practice as well as one of self-sustenance. The Hopi have long held methods for growing food in a harsh, arid environment, like dry farming, but Sekaquaptewa says as climate change enflames these challenges, the Hopi people are further separated from growing and raising food, a direct connection to their culture. Photo by Micah Robin Left: Sekaquaptewa arranges water walls around tomato and pepper starts in her home garden in Second Mesa on the Hopi Reservation in April 2024. The water walls protect the plants while the threat of spring frost persists. Sekaquaptewa is a member of the Hopi Tribe and a University of Arizona extension agent serving her tribal communities by connecting them with resources from Arizona’s land grant university. The Federally Recognized Tribes Extension Program was established in 1990, 75 years after the parallel program for non-tribal communities was established. Sekaquaptewa provides learning opportunities ranging from horse digestion and rangeland grass health, to soil preparation and financial literacy for tribal producers. Photo by Micah Robin

37

Watch a short film about Sekaquaptewa

Kash Gleason, a 19-year-old Yakama tribal member, pauses to look at the bison he hunted at Beattie Gulch on the northern border of Yellowstone National Park during the tribal bison hunt on February 20, 2023. The bison is the first that Gleason has hunted in Yellowstone. Eight Native American tribes have federally recognized treaty rights to hunt bison outside of Yellowstone, which is one of the ways park bison populations are managed. In 2023, a harsh winter caused a record number of bison to migrate out of the park, resulting in the largest number ever harvested by tribes. Gleason traveled 16 hours with his family from his home in Yakama Nation, Washington, for the hunt, and for the promise of bringing an important ancestral food back to his community. For generations bison have been a source of food for indigenous peoples, and tribes from the Columbia River Basin plateau would travel to the Yellowstone area to hunt, trade and bring home meat to their families.

Photo by Louise Johns

A forager harvests a wild morel mushroom with a knife, which helps keep them clean and limits damage to the underground mycelial network that births them. Morels pop across the Mountain West in early spring and summer when ground temperatures reach roughly 50 degrees and disappear once they hit 60. The mushrooms can be found in river bottoms, woodlands and burn areas where abundant flushes of mushrooms are common in the first two years after a forest fire.

Photo by Ben Pierce

A woman holds up a bloody elk heart from a fresh kill. When hunting in the vast Bridger-Teton National Forest, a successful kill is just the beginning of the experience. Next comes the task of field dressing and packing out the elk quarters on horseback, which is no small endeavor—a typical bull elk yields over 200 pounds of meat. The chance to harvest an elk each fall is a unique privilege, and one that shouldn't be taken for granted. Photo by Della Frederickson

40

A four-man crew from the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Indian Reservation draw in gillnets that they use to catch non-native lake trout in Flathead Lake. The Tribes established this fishery to protect native bull trout and westslope cutthroat trout, which are threatened by predation from the non-native lake trout, and they sell the gillnetted lake trout at vendors across Montana through their company Native Fish Keepers to offset the costs of boats, fishing gear, and personnel. Photos by Lynn Donaldson

41

42 Fly Fishing in Montana can be a rugged, sometimes-tiring adventure—that’s why Madison Double R will be a welcome respite at the end of each day. Located on the world-renowned Madison River south of Ennis, Madison Double R offers first-quality accommodations, outstanding cuisine, expert guides, and a fly fishing lodge experience second to none. Contact us today to book your stay at the West’s premier year-round destination lodges. MADISONRR.COM • 406-682-5555 • office@madisonrr.com

ADVENTURE THE RIVER THAT REVEALS US // 46 ARTIFICIAL ADVENTURES // 56 MAPPING THE WILD WITHIN // 64 KING OF THE ROADTRIP // 69 AMPLIFYING OUTDOOR NARRATIVES // 76

Bathed in sunset hues, two runners descend Sacagawea Peak against the breathtaking backdrop of the Bridger Mountains. Named for the Lemhi Shoshone woman who accompanied the Lewis and Clark expedition, Sacagawea is the highest point in the Bridger Range at 9,654 feet.

Photo by Kyle Niego

THE RIVER THAT REVEALS US

Navigating relationship to landscape in the Grand Canyon

By Bella Butler

The Colorado River winds through the Grand Canyon. This view is seen from an overlook beneath the Nankoweap Granaries, Puebloan grain storage structures that date back to 1200 AD.

Photo by Colin Hislop

I’ve heard that when a commercial trip launches in the Grand Canyon, guides recite the hallmark statement from John Wesley Powell’s 1869 expedition: “We have an unknown distance yet to run, an unknown river to explore. What falls there are, we know not; what rocks beset the channel, we know not; what walls ride over the river, we know not.”

Powell penned these words in his journal at the confluence of the Green and Colorado rivers, where the silty sage-colored water for which one river was named gave way to the chalky red namesake of the other. Subsequent events would prove Powell right. Though many Indigenous tribes have long called the canyonlands home—many even regarding them as their holy sites of creation—Powell’s trip was the first recorded by Western settlers. In the heat of the desert in August, he and his crew of nine men faced near starvation and other questions of survival, and just three days before completing his journey Powell lost three men to discord, all of whom left the river to hike out and were never seen again.

At that confluence of complementary colors, Powell couldn’t have predicted the perils before him, and although hopeful for some level of acclaim, he also didn’t know the legacy that would follow him home. He didn’t know his expedition would become the catalyst for the Four Great Surveys of the West, nor the creation of the U.S. Geological Survey and the U.S. Department of Ethnology. He didn’t know his discoveries would have him pleading for the progress-hungry delegates of Washington D.C. to heed the aridity of the West, and he didn’t know they’d ignore him. And he certainly didn’t know that nearly 150 years after his own harrowing journey, five 18-foot oar frames carrying my female-skewing group of 20- and 30-somethings wearing Hawaiian shirts and glitter would complete the 226-mile stretch of the Colorado River through the Grand Canyon, crushing the same waves that crushed him, all while singing “Dixieland Delight” (the Alabama version) on repeat.

47

Christian Newby rows an 18-foot oar frame raft through the Grand Canyon in March 2024. Photo by Colin Hislop

As we pushed off at Lees Ferry on March 24, 2024, I didn’t say Powell’s words aloud. To me, they seemed to have soured in the post-Powell world where maps, social media and river flow charts overshadow any sense of mystery. What falls there are, we knew, and in fact had a list of recommendations for the best to take photos of. What rocks beset the channel, we knew, courtesy of a $30 river map with detailed beta on each rapid. What walls ride over the river, we knew, thanks to a color-coded stratigraphic column and a newly graduated master of hydrogeology in our midst. What was left for us and the other 29,000 river runners who travel the canyon annually to “know not?”

But of course anyone who’s spent enough time on rivers knows that water has the power to not only erode the outer landscape but also our inner one, and the true mystery is in what it reveals within ourselves.

I didn’t consider the color of the water until our second day on it. At Mile 112 Camp, I studied the green ripples and tasted the full-bodied grittiness of the word Colorado in my mouth. This Spanish name, better suited for the once-free flowing red river it was originally named for, tasted different spilling from my lips and into this version of the river, the emerald ribbon that maybe should be called something else entirely.

Out of respect for the Colorado of today though, the one that flipped one of our boats and pumped adrenaline through many a swimmer, I should make clear that this river is not tamed. But it is bridled. When the Glen Canyon Dam, built in 1966, choked this once uproarious red river, the Colorado became a wild horse with a bit between its teeth and reins around its neck, yielding to the tug that tells it when to sprint forward and when to rear back. And while even a saddled horse has a mind of its own, this bronco is forever changed from its free-roaming days.

The water flowing by Mile 112 Camp moved steadily but not

swiftly; there was no sense of urgency. Using my imagination, I tried to fill the riverbed with another image, one of opaque rust-colored water bucking over sandstone ledges and boulders, eager to reach its destination, unflinching in its demonstration of omnipotent power over the landscape. The Colorado once gushed into the Sea of Cortez, 1,450 miles from its Rocky Mountain headwaters, but the 15 times dammed and manytimes diverted river now rarely reaches this destination. In 1920, a stream gauge near Yuma, Arizona clocked the river flow at 129,000 cubic feet per second. After the filling of the Hoover and Glen Canyon dams, the river’s spike was a mere quarter of that.

Powell’s 1869 expedition was intended for science, a means by which to study geology, geography and water as a resource, though the conditions of the canyon quickly refocused the goal to survival. But even with his barometers, maps and other instruments in pieces, Powell gleaned perhaps the most critical hypothesis from his immersion in desert country—there’s not enough water. At least, not enough to match the expansive vision of a then-ballooning United States. In 1862, just seven years before Powell’s trip, President Abraham Lincoln signed into law the Homestead Act, granting 160 acres of public land—read: stolen Native land—to settlers looking to claim their piece of the West. When Powell emerged, he pleaded with Congress: This 160-acres thing, it’s not going to work, he told them. Historian John Ross chronicles Powell’s experience in his book The Promise of the Grand Canyon.

“In the canyon that experience was an epiphany of sorts in a visceral way,” Ross said in a 2019 Arizona Public Radio interview. “It began to evolve into an idea about [how] humans should intersect and interact with the land, and with its resources, with water … He was not an environmentalist in John Muir framework, but in a very important way he was laying out the groundwork to think about how we intersect with our land sustainably.”

Ross suggests Powell was one of the first people (I would further qualify as one of the first white settlers) to start thinking about how the conditions of the land, climate and

48

Butler’s group prepares dinner at Upper Ledges, a small rock ledge camp at river mile 159. Photo by Bella Butler

geology should shape the way we use it, not the other way around. But Powell was mournfully ahead of his time, and his previously written-off warnings now haunt us as prophecy.

In late 2022, the bony skeletons of rapidly dropping lakes Powell and Mead rattled in national headlines. Stories about the plight called the Colorado “crisis-plagued,” and described the river as if it were a cancer patient on the brink of becoming terminal. The river system is shared by Mexico, 30 Native tribes, as well as Colorado, New Mexico, Utah, Wyoming, Arizona, California and Nevada. More than a century and a half after Powell made his case to mind the arid West, nearly 40 million Americans rely on the Colorado as a water source, as do 5.5 million acres of farmland. The dams at Powell and Mead provide power for millions. In a typical year, 1.9 trillion gallons of water are consumed in the Colorado River Basin.

According to data shared by The New York Times in May 2023, that massive figure is portioned by these categories:

- Corn Grain

- Barley

- Other Crops

- Livestock Watering

A decades-old agreement between the seven states in the Colorado River system appropriates water to each state in quantities now being analyzed as more than what exists within the system. In an unprecedented action, the U.S. Department of the Interior asked the states to update their agreement in January of 2023 or face cuts by the federal government. Amid heated debate, Arizona, Colorado and Nevada agreed in May 2023 to take less water, but as historic drought and other manifestations of climate change loom large, the water system’s fate still hangs in the balance.

“If Congress had listened to what Powell said,” Ross said in his NPR interview, “if we had kept water more in watersheds and developed appropriately, I think we would be a saner, saner world.”

It’s amazing how this perilous reality of scarcity eludes you on the river. A mile beneath the rim, everything is scaled in such a way that makes it hard to imagine the concept of limitation. Any boater also knows that the river often demands complete presence—it’s in fact the thing that draws many of us to it. In reading Powell’s journals, this seems true for him as well. While he emerged with grand conclusions, his entries are anchored in active language; verbs tell the story of each day, and adjectives bring each sight and experience into

49

12%

4%

4%

79%

55%

Feed 11%

3%

2%

- Residential

- Commercial & Industrial

- Thermoelectric Power

- Agriculture

- Livestock

- Cotton

- Wheat

1%

7%

<1%

Butler and her partner, Micah Robin, approach the falls at Deer Creek, a popular stop for many boaters and identified as a Traditional Cultural Property by the Hopi, Zuni, Hualapai, and the Southern Paiute tribes. Above the falls in the Deer Creek Narrows, red handprints from ancestral peoples are still visible on the walls. Photo by Colin Hislop

colorful view at a time when cameras could only shoot in black and white.

Logged on August 25, 1869, at what I presume to be the canyon’s famous Lava Falls rapid area, Powell wrote:

“From this volcano vast floods of lava have been poured down into the river, and a stream of the molten rock has run up the canyon, three or four miles, and down, we know not how far.”

What a surprising sight those black formations must have been to Powell, petrified in their fluidity. To us, Lava Falls was heavily anticipated. A series of YouTube videos, and an Instagram page, @grandcanyoncarnage, had memorialized the image of Lava before we even saw it ourselves. We shared the scout above the rapid with several other groups studying the route of safest passage and greatest thrill. We watched as motorboats, allowed on the canyon April through mid-September, barreled through the whitewater, their inflatable tubes taking the brunt of the river as customers sat in rows on the center platform, gripping the shoulder straps of their life jackets like the safety bars of a roller coaster.

These rigs are flying cars compared to Powell’s fleet, which included three 21-foot boats made of oak and one 16-foot boat made of white pine, all built to Powell’s specifications. The smallest boat, designed for Powell to move swiftly as the lead, was named the Emma Dean after Powell’s wife. Among the other gear boats were the Maid of the Canyon, a symbolic companion for the lonely men; the Kitty Clyde’s Sister, named for a song from the Civil War, during which all expeditioners but one fought in; and finally, the No Name, no story there. We followed in tradition, naming the members of our fleet We Three Queens, self-proclaimed by the boat’s female trio; the Ice Queen, for the boat with the cocktail ice cooler; White Lightning, sometimes referred to as Major Med, whose white rubber carried both our med kit and EMT; Meat Boat, or Poop Boat, the only all-male vessel and the unlucky carrier of our human waste; and finally my beloved boat, the kitchen boat, called Yes Chef.

As we went to push off from the eddy above Lava, the roar of the falls was so loud we couldn’t hear one another, so we all raised our hands nervously in the air, river speak for “go.”

My boat was last, captained by Christian Newby, who sent

us in stern-first, handily kissing the edge of the top pour-over. As we hit the next hole, a massive wave rose to fill the entire backdrop, and Newby let out one big hoot before punching through the water with one powerful oar stroke. We met our crew below the rapid for the traditional celebration at Tequila Beach. We passed around a bottle wrapped in duct tape and took turns puckering our faces while Lava Falls continued to roar behind us.

While Powell’s journals suggest his crew opted instead for a three-hour portage around the falls, he shared in the celebration of splendor in that wickedly stunning section of the canyon (though I suspect there was no tequila).

“What a conflict of water and fire there must have been here!” he wrote. “Just imagine a river of molten rock, running down into the river of melted snow. What a seething and boiling of the waters; what clouds of steam rolled into the heavens!”

Our own expressions of wonder were limited to simpler language, often a mere “look at that rock!” but the sense of awe was congruent.

Ironically, the canyon has a way of leveling otherwise far-apart experiences like this. It takes layers of deep time and presents it on a single plane. The rock at Lava Falls from an eruption 800,000 years ago, red handprints from some of the canyon’s earliest inhabitants, the scuffs on the rocks from Powell’s burly oak boats, and our Chaco-patterned footprints in the sand all exist together in one moment. Maybe more than any place else I’ve been, this canyon holds onto things. It’s something about its paradoxical compactness and immensity, its depth and antiquity, that renders it the greatest raconteur of the West. The water carries countless stories, but the canyon keeps them.

On day 15, we tied the boats off in an eddy and wandered up a side canyon called Blacktail. Another group, the one we launched with at Lees, was camped where Blacktail’s dry creek bed spilled into the river, and they joined us on our walk. My partner Micah and I took up the rear, and Hoppe, an older man from the other group, hobbled a bit to keep pace with us.

“Jeff’s up here, and he’s gonna play guitar,” Hoppe told us

50

Left: The Nankoweap Granaries remain intact high above the river. Photo by Colin Hislop Right: A cactus bloom emerges from a bud. One of the benefits of a spring trip are the flowers. Photo by Colin Hislop

between puffed breaths. “He’s really good.”

It was Hoppe’s birthday, something we only knew because his son Henry told us. Each person in our group took turns wishing him happy birthday as our boats played leapfrog down the river, and each time he responded the same: “It’s just another day, for me.” He didn’t tell us which birthday it was (I’m guessing around 65) but he did divulge that this was his sixth trip down the canyon, which is perhaps a better measure for his life, anyway. He proudly proclaimed that his wife Cindy whom he calls “the boater of the family,” has been down seven times. The couple live on a 75-acre retired fish hatchery in Kremmling, Colorado—population 1,500—after living in Grand Lake, which “got too touristy.” Cindy runs a rafting supply company called Ripple Works, which she says doesn’t make much money but lets them share good deals on boating gear with their friends, which makes it worth it.

Despite launching with them 130-some miles and two weeks ago, we hardly spoke to them until they watched us flip a raft in Crystal Rapid. They floated past us as we cleaned up our mess, effectively snaking the sought-after Bass Camp. Henry later offered a truce, telling us he’d flipped his own boat in the same hole five trips ago—he says he’s always gone the left line since.

As we walked alongside them in these wavy walls, I felt like we all knew each other a little better. We started the trip calling them The Oldies, and assumed their gray-haired horde looked down on our froth-mouthed crew of Grand Canyon virgins. But after sharing more miles, we know them to be people who have lived a good amount of their lives on this river and others, people whose stories are worth hearing. I hope they now know us not as a bunch of whippersnappers with reckless energy, but passionate young folk galvanized by the prospect of our own lives spent on rivers. As we walked, Hoppe told us about the chaos of his own first trip, where they forgot the toilet seat, and another trip where they lost a poorly tied boat to the current in the middle of the night. He smirked at us, and I supposed maybe he saw a little of them in us.

“The first time down is always the best,” he’d tell us later, donning a shirt with “Grand Canyon April 2004” printed on the breast pocket.

With Hoppe on our tail, we arrived to a slight widening in the river-bent canyon where our group mixed with The Oldies in an amphitheater-shaped audience. A younger man with eyes the color of the clear aqua river at Havasu Falls was picking guitar strings and singing a song I didn’t know in a voice rubbed with the texture of desert sand.

“Wow,” I thought. “Jeff is good.”

Hoppe leaned against the wall and Micah and I found our place among the audience, which started humming along to Tyler Childers’ “Feathered Indians,” a request from Becca, captain of We Three Queens. Across from us, our friends Cole and Kaelyn danced, swinging each other around in their own wingspan of tenderness, and Hoppe watched. It was bright outside, but only some of this light found us on the bed of the canyon, the sedimentary walls capturing both specks of sun and guitar-string echoes between conglomerated grains of sand.

This moment was beautiful because it was shared, not only between us and The Oldies, but between us and all

that this canyon holds. There’s honor in giving our stories to this Grand Ole Canyon, which will remember our shadows dancing against its moonlit walls when none of us remain to remember ourselves.

On the longer stretches of slack water, where the rapids were few and far between and there wasn’t much to do but sit on the bow and feel the river moving beneath me, I thought a lot about Barry Lopez’s 1945 essay “The American Geographies.” He wrote that the only way to truly know a place is through time spent in it. “The people in whom geography thrives,” Lopez wrote, are those who have spent this time. Perhaps they don’t know the name of every flower, or how to distinguish between two kinds of trout, “but they are nearly flawless in the respect they bear these places they love,” he said. “Their knowledge is intimate rather than encyclopedic, human but not necessarily scholarly. It rings with the concrete details of experience.”

Knowing the Colorado River and knowing the Grand Canyon has nothing to do with maps, photographs or colorcoded geology keys. This was true for Powell, when he declared all that he “knew not,” and it was true for me and my 14 friends on March 24, 2024. Knowing these sacred places isn’t about knowing what they can do for us, either; it’s not about water appropriations, historic droughts or even river permits. Knowing these places is about coming into relationship with them; it’s letting quiet, perfect moments of awe transform us, and the permission they give us to be part of this beautiful, wild system.

At our own confluence in the West, where history merges with the present and so much mystery lies ahead, we lean into this mutual reverence with the land. What’s left to “know not” is not the West itself, but how we will apply ourselves to it.

Bella Butler is a writer, editor and aspiring Grand Canyon regular who lives in Bozeman, Montana. She is the Managing Editor for Mountain Outlaw.

Experience the Grand Canyon through film.

51

Butler’s crew poses for a group photo in Redwall Cavern.

Photo by Alex Nelson

ARTIFICIAL ADVENTURES ChatGPT AND A MODERN MOUNTAIN

ODYSSEY

WORDS BY ANDREW ARENA

PHOTOS BY CHARLES STEMEN & KYLE TILLEMAN

Inever thought too much about how I might die, but as I prepared to lean the weight of my body off the edge of a 3,000-foot cliff rear first, it occurred to me that this wasn’t how I would’ve imagined it. Just minutes before, I’d been grinning ear-to-ear and lounging luxuriously in the August sun with my two friends, Charlie and Kyle, as we congratulated each other on a successful five-pitch trad climb in Montana’s rugged Beartooth Mountains. Now I was literally teetering on the edge of life and death, and the only person—or thing—I had to blame was a robot. That’s right. This was all because of ChatGPT.

This all started last summer, when Charlie asked me to join him and his friend Kyle on an adventurous weekend in

the Beartooths. It was a layered invitation, though, because what I would later learn is that this three-day trip had been designed by ChatGPT, an artificial intelligence computer program “that talks like a human and helps you with all sorts of things,” according to the bot itself. Charlie, a Bozemanbased photographer, had prompted ChatGPT to lead us on an adventure weekend “worthy of being published.”

“Sure,” I had said when Charlie explained this. “Why not?”

In the coming weeks, Charlie revealed ChatGPT’s detailed itinerary. The AI model had not only determined our activities,

>>>>>>>

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

I took a deep breath, silently prayed to Alex Honnold, and leaned back into the abyss.

While on a Montana adventure completely dictated by ChatGPT, Charlie Stemen, generously fueled by "special gourmet blend" coffee as prescribed by ChatGPT, "takes the lead on setting routes," also a directive from the AI program. Kyle Tilleman snapped this photo while grumbling about how ChatGPT didn't allow him coffee this morning, and Andrew Arena was out of sight at the belay soaking in the view and eating gummy bears.

but also where and when they would take place; it had even developed uniquely strict meal plans to be followed by each of us for the entire weekend. Our trip would span three solid days and would include mountain biking, gravel biking, fly fishing and an epic five-pitch trad climb. While we would all partake in the same activities, the AI-generated meal plans would be custom.

Charlie, a thin, bespectacled artist, would be eating such delicacies as gourmet salmon wraps, charcuterie boards and quinoa salads. Kyle, a tall and hiply mustachioed Bozeman native, would be eating similarly but sans pork to appease his own dietary restrictions. I, on the other hand, an incredibly handsome and intelligent construction worker, was prescribed

mac n’ cheese, pre-packaged BBQ chicken and PB&Js, in addition to a startling amount of Mountain Dew Code Red. While the others laughed at my “child-like” menu for the weekend, I was unabashedly satisfied with the arrangement. A lifetime of gas station breakfasts and energy drinks while working in construction had perfectly prepared my body for this.

As comfortable as I was with my meal plan, I was equally uncomfortable with the itinerary. Although I’m a finely tuned endurance machine, I’m not even a remotely competent climber, and I hadn’t been on a mountain bike in several years. But I put my nerves aside at the prospect of such a great adventure.

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Photo by Kyle Tilleman

The appeal of using technology to prescribe the "perfect weekend" or the "craziest adventure" is alluring, and it can certainly be a fun way to spice things up. However, the true magic in our outdoor experiences is found in the camaraderie forged between friends during a climb, or the inside jokes created during a long day of biking.

Day 1: Cliffhangers and Code Red

I awoke in the early morning darkness to the metallic rustle of Charlie and Kyle sorting and packing climbing gear. I sat up in the custom-built bed of my Chevy Astrovan and cracked my first Mountain Dew Code Red, letting its sweet nectar quench my morning thirst.

I sat for a moment and prayed to Alex Honnold (the only climber I knew of) to please grant me safe passage on our climb today. I slid open the door and went out into the morning darkness.

As we walked down the crunchy gravel road, headlamps illuminating our way, we passed a collection of backhoes, excavators and bucket loaders parked along the dusty shoulder of our path.

While the sun rose, we ogled the mountains’ massive silhouettes in the distance. We turned off our headlamps and veered off the trusty gravel road, hiking through dense woods toward a startlingly steep rock wall. As we drew nearer to the crag, our approach transformed from dense and tedious bushwhacking to nervy scrambling; I watched Kyle and Charlie deftly navigate the rock and tried to mirror their maneuvers. A brilliant sunrise washed the granite in a grapefruit glow as we pulled ourselves up to the base of our route. At the foot of the crag, I stood nervously on our first belay station’s narrow, flattish platform. My hands perspired as Kyle and Charlie each gracefully climbed the first pitch, leaving me alone, moist and anxious. The radio attached to my harness crackled as Charlie’s voice informed me I was on belay. I took a deep breath, swallowed hard and began scaling the granite wall.

Aside from a fiendish finger crack halfway up the first pitch, the climb was spectacular. The rough granite warmed as the sun rose overhead, bathing the entire valley in a beautiful midday light. Though the threat of weather innocuously appeared in the distance, no wisp of wind threatened to spoil our climb.

After a deserved celebration at the top, Charlie informed me that we would be rappelling off the top of the mountain, not casually walking down the back. I timidly peered over the edge of what Charlie told me we would be rappelling from; to my horror, I looked down into a massive, wide-open expanse; this would be an utterly free-hanging rappel.

Suddenly, I recalled a moment from the night Charlie had invited me on this trip. On my way out the door of Charlie’s house, his partner, Jessica, had caught my arm and abruptly pulled me aside.

“Something weird is happening with Charlie and this whole ChatGPT situation,” she had said. “He’s been staying up all night working with it.” She’d hesitated before nervously whispering, “I think he’s been talking to it.”

I had laughed, but as my guffaw faded into silence the look of genuine concern had remained imprinted on Jessica’s wrinkled brow. Now gripped by fear, Jessica’s words returned to me; Charlie had been talking to ChatGPT. My adrenaline began urgently

>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Top left: Arena downs one of his many AI-prescribed Mountain Dew Code Reds. Photo by Charlie Stemen Left: Tilleman suspends on the rapel, blissfully unaware of ChatGPT's real motivations and seemingly charmed after enjoying a cold lemonade at the top of the climb that ChatGPT required the trio to carry up in a thermos. Photo by Charlie Stemen

pumping conspiracies to my brain—or were they conspiracies? How much did we really know about this technology? Had AI taken over Charlie’s feeble human brain? Had it convinced him that human beings were a disease to the Earth? Had it persuaded Charlie that eliminating the entire human population was the only solution? Was I to be the first eliminated?

My hands trembled, and my mind raced as Kyle tied me in and instructed me on how to navigate my way down the rope safely. I took a deep breath, silently prayed to Alex Honnold, and leaned back into the abyss.

Day 2: Gravel Bikes and Drone Strikes

I awoke again in the Astrovan. Birds chirped as the sun filtered through the canopy of evergreens above. I cracked open a Mountain Dew Code Red; the sticky red liquid tasted even sweeter knowing I had evaded death. I was alive, but barely. Against all odds, I had safely rappelled down to the canyon floor, much to Charlie’s chagrin. His dark AI overlord would not be pleased.

“Today will be a much safer day,” I thought as I took another hearty swig from the red can, the syrupy sweetness lubricating my achy bones.

We loaded our gravel bikes into Charlie’s van and drove off in a cloud of dust to the starting point for our bike ride. The innumerable gravel roads, scant populace and screen-saver scenery make Montana an extraordinary destination for seemingly limitless gravel riding. Our ride began on the desktop of Windows 98 as we zipped past a glowing viridescent pool flanked by jagged, snow-capped mountains.

My grin expanded as we whisked downhill. The familiarity of the gravel bike was comforting after my ineptitude climbing the previous day. I deftly maneuvered around potholes and crouched into an aerodynamic tuck.

I had all but forgotten about Charlie’s AI treachery when we came upon a scenic bridge that Charlie wanted to take some drone photos of. My heart sank and my eyes narrowed as he began flying his small, robotic minion overhead. We hadn’t seen another soul all day; there would be no witnesses if ChatGPT decided to make his—its—move.

As Kyle and I pedaled back up the road in preparation for the supposed drone photos, I whispered a discrete warning.

“Charlie is compromised; drone strike.”

Kyle laughed awkwardly with a look of confusion and asked me what I had said. We didn’t know each other very well. But before I could explain, Charlie shouted for us to go. In a flash, Kyle was off and pedaling toward the bridge, mustache flowing in the breeze. I quickly mounted my bike and spun hard, desperately trying to catch Kyle and warn him of our impending doom, but it was too late. I caught up just in time for us to reach the bridge. I winced,

Top right: Tilleman and Arena cruise through a rural landscape on their gravel bikes. The miles fly by when you blindly follow AI. Photo by Charlie Stemen Right: Arena and Tilleman are forced to attempt a campfire blueberry cobbler. Meanwhile, Stemen hid a Bluetooth speaker in the woods and later played grizzly bear noises—a prank ChatGPT added to the trip the night before departure. Photo by Charlie Stemen

Top right: Tilleman and Arena cruise through a rural landscape on their gravel bikes. The miles fly by when you blindly follow AI. Photo by Charlie Stemen Right: Arena and Tilleman are forced to attempt a campfire blueberry cobbler. Meanwhile, Stemen hid a Bluetooth speaker in the woods and later played grizzly bear noises—a prank ChatGPT added to the trip the night before departure. Photo by Charlie Stemen

and my body tensed, expecting a rain of fire from above; my front tire hit the bridge’s rickety wooden boards.

The next thing I knew, I felt the familiar crunch of gravel beneath my tires. We had survived. But why? I stopped, my pulse racing, and drank a Code Red to calm my nerves.

We pulled our bikes into camp with the weary squeak of dust-coated brake pads and soaked our pink, sunburnt bodies in the river. But alas, Cage the Elephant was right; there is no rest for the wicked, and as our weary bones creaked in protest, we arose from the river. ChatGPT wanted us to go on a run.

After lethargically changing into running attire, we set out on the trail with the vigor and agility of cows in mud. However, as the miles ticked by, our movements became fluid; our strides grew comfortable and confident. A moose lumbered across the trail in front of us, her journey down the mountain prompted by nature, ours by machine. We arrived back in camp tired but satisfied.

The next part of ChatGPT’s evil plan was perhaps its most sinister ploy yet. According to ChatGPT’s itinerary, I was supposed to spend the evening fly fishing and catch a delicious trout to accompany some roasted vegetables and mashed potatoes. Of course, the robots know there is nothing more damaging to a man’s ego than being unable to provide food for his family. And—as everyone also knows—it’s called fishing, not catching. As I strode through the bugless afternoon air into the gently babbling stream, I knew I wouldn’t be catching any fish. I double-hauled hopelessly underneath a clear sky as Charlie snapped photos disquietingly from the bushes. Later that evening, after a meager dinner of roasted vegetables, I went to bed hungry while the guilt of not feeding my friends ate me alive.

Day 3: Mountain Bike Musings and Dew-Induced Delirium

I awoke in the inky blackness of the pre-dawn morning, my head pulsing slightly, most likely from overindulging in Mountain Dew while severely underindulging in water the past few days. A choir of yawns accompanied the percussive sounds of mountain bikes being loaded into Charlie’s van as we scrambled to scarf down a quick breakfast and load our packs for the day.

Charlie’s van slowly climbed the towering mountain pass that our epic 16-mile, 5,000-foot ride would begin atop as the sun’s first rays peeked out from behind the mountains. I struggled to slurp down a Mountain Dew. We were all hungry from the previous night’s fishless dinner.

We pedaled out of the gravel parking lot as the sunrise blushed above the trail, beginning our first descent. Soon we found ourselves pedaling across a breathtaking alpine plateau, saw-toothed mountains reaching desperately skyward in all directions. Charlie pedaled robotically ahead of me.

A series of short, technical climbs and fast, stonestrewn descents led us off our plateau, traversing around an enchanting alpine lake. My rented mountain bike handled the chunk and chunder with impressive aplomb; my confidence and enjoyment increased with every mile. I soon found myself hitting small jumps and pumping through corners.

As the distance between us and civilization increased and the landscape grew more and more remote, an intrusive thought reminded me that Charlie and ChatGPT could strike at any moment. But as I whizzed down a jumbly switchback, I didn’t care. I didn’t care if Charlie’s compromised, computerized brain tried to sabotage me, and I certainly

56 >>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>>

Left: The adventurers take off on a 7-mile run after returning to camp tired from gravel biking but beholden to ChatGPT’s relentless itinerary. Photo by Charlie Stemen Right: Arena casts into the night, the group’s entire dinner hinging on his success. Photo by Charlie Stemen

didn’t care if artificial intelligence took over the world. I was completely present, having fun with two great friends in a landscape that only a tiny portion of the world’s population ever gets to experience.

I picked my way up a puzzling patchwork of protruding boulders, reveling in the tricky balance and control required to stay upright. We descended steadily off the exposed alpine slope, switchbacking our way down into a more arborous landscape, the trees growing taller as we plummeted down the mountain. Our tires danced gracefully over roots and around corners; our hoots and hollers rang through the canyon.

Suddenly, after a series of tight turns, we emerged into the surreal environment of a burn zone. The charred, blackened trees spread spindly through the eerily open air. A thick layer of newspaper-colored dust coated the ground. We stood and quietly admired the landscape; two humans and one potential robot posed in a starkly alien world.

At the end of our ride, we regrouped in Charlie’s van as rain began to fall. Charlie hospitably cooked us pancakes while we chattered pleasantly about the ride. The van grew quiet as hungry mouths consumed the delicious flapjacks; our chewing drowned out by the pitter-patter of rain.

As I drove home that afternoon, pounding antacid tablets and water, I reflected on the weekend.

As revolutionary new technologies like artificial intelligence, smartwatches, and stretchy yet breathable spandex infiltrate the world of outdoor recreation, it can be easy to lose sight of why we’re going on adventures in the first place.

The appeal of using technology to prescribe the “perfect weekend” or the “craziest adventure” is alluring, and it can certainly be a fun way to spice things up. However, the true magic in our outdoor experiences is found in the camaraderie forged between friends during a climb, or the inside jokes created during a long day of biking.

So get out and plan an epic weekend with your friends, even those overtaken by artificial intelligence (maybe especially them, they need it), and make some memories that will last a lifetime.

A born and raised Mainer now living in Montana, Andrew Arena is an avid runner, cyclist and skier who lives only in states that start with the letter M.

Charles, Chuck, Charlie Stemen is an architectural and adventure photographer based in Bozeman, Montana. In addition to photography, he operates an independent design studio, and can usually be found at Bridger Bowl or exploring some local peaks.

Kyle Tilleman is a CPA, Woodworker, and Photographer from Bozeman, Montana. You can find his work on IG @k.t.customs.

57

>>>>>>>

Read the ChatGPT conversation here: >>>>>>>>>>>

Top: Stemen robotically skims over plateau chunder. Photo by Kyle Tilleman Above: Arena enjoys his prescribed meal, a ham sandwich with cookies and a Code Red. Stemen was prescribed a different diet including gourmet cheese and charcuterie board with artisanal crackers. Photo by Kyle Tilleman

58 BUILDING A HOME IS PERSONAL. For over 30 years, Bob Houghteling, the owner of HCI Builders, has personally overseen custom builds built with relentless perfection. Backed with hands-on experience, his wealth of knowledge specializes and spans from Timber Frame to Mountain Modern homes. Give him a call and start dreaming of your custom home today. LET BOB BRING YOUR VISION TO LIFE CALL 406.995.2710 | HCI-BUILDERS.COM

Whether you are interested in chasing billfish in Costa Rica or Cabo or relaxing along the Emerald Coast of Florida, Jimmy Azzolini, Big Sky resident, is your authority on yacht ownership.

Jimmy has been with Galati Yacht Sales, the largest family-owned yacht brokerage firm worldwide, since 2000. During this time, Jimmy has helped countless families match the right yacht to their lifestyles.

JIMMY AZZOLINI LICENSED YACHT BROKER 850.259.3246 FL | AL | TX | CA | MX | CR GALATI YACHTS .COM FIND YOUR NEXTadventure

Find out more about yacht ownership and how Jimmy and Galati Yacht Sales can help you create new memories.

MAPPING THE WILD WITHIN: SELECT PEAKS’ 20-YEAR ENCORE

Thomas Turiano’s Love Letter to Greater Yellowstone

By Lauren Burgess

Thrumming with the resonant call of the wild, the compilation of route descriptions, geology and history of 107 prominent peaks across 13 mountain ranges, known as Select Peaks, has for decades been a backcountry essential akin to scripture for those who view the alpine as altar. Routes have been scribbled in notepads or photocopied, pages even torn out, then pocketed and carried into the wild heights of Greater Yellowstone to be followed with devout reverence. The first edition’s limited print run of just 5,000 copies selling for $44.95 each made it a thrift store jackpot for a fortunate few, while others found themselves in feverish eBay auctions with bids soaring beyond $300. As time passed, the physical manuscript remained coveted even as mountaingoers learned to navigate the online landscape of terra digitalis.