SUMMER 2024 A PUBLICATION OF THE OKLAHOMA VISUAL ARTS COALITION

BECOME AN OKLAHOMA INSIDER. Get events info and behind-the-scenes stories about Oklahoma’s food, travel, events, and culture sent to your inbox. Sign up for Oklahoma Today’s newsletters at Newsletter.OklahomaToday.com. BECOME AN OKLAHOMA INSIDER. Get events info and behind-the-scenes stories about Oklahoma’s food, travel, events, and culture

your inbox. Sign up for Oklahoma Today’s newsletters at Newsletter.OklahomaToday.com.

sent to

ON THE COVER // Delia Miller finishing her mural Flight Path in downtown Ponca City, 2024 | Bethany Young, page 14; MIDDLE // Benjamin Harjo, Jr., the light horseman, 2008, gouache on paper, 18 1/2” x 12 1/2” | Phil Shockley, page 18; BOTTOM // Rachel Ann Kendrick, Rainbow Radar 1 (detail), 2024, acrylic on gesso-prepped plastic sign, page 22

Support from:

CONTENTS // Volume 39 No. 3 // Summer 2024

4 6

18 10 14

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

JOHN SELVIDGE

IN THE STUDIO American Nightmares // An Interview with John Babbitt

REVIEW Life Goes On // Lisa Karrer’s SHELTER at Oklahoma Contemporary OLIVIA DAILEY

FEATURE A Wider Lens of Inclusion // In Ponca City with the Sunny Dayz Mural Festival HELEN OPPER

PREVIEW Joy Uncompromising // Benjamin Harjo, Jr. at the OSU Museum of Art MOLLY MURPHY ADAMS

PREVIEW Surreal Horizons // Rachel Ann Kendrick at Positive Space Tulsa

SALLIE CARY GARDNER

26

INTERMEDIA Of Celluloid and Fabric // An Interview with Catherine Shotick, Curator of OKCMOA’s Edith Head: Hollywood’s Costume Designer

Oklahoma Visual Arts Coalition PHONE: 405.879.2400 1720 N Shartel Ave, Ste B, Oklahoma City, OK 73103. Web // ovac-ok.org

Executive Director // Rebecca Kinslow, rebecca@ovac-ok.org

Editor // John Selvidge, johnmselvidge@outlook.com

Art Director // Anne Richardson, speccreative@gmail.com

Art Focus is a quarterly publication of the Oklahoma Visual Arts Coalition dedicated to stimulating insight into and providing current information about the visual arts in Oklahoma. Mission: Growing and developing Oklahoma’s visual arts through education, promotion, connection, and funding. OVAC welcomes article submissions related to artists and art in Oklahoma. Call or email the editor for guidelines. OVAC welcomes comments. Letters addressed to Art Focus are considered for publication unless otherwise specified. Mail or email comments to the editor at the address above. Letters may be edited for clarity or space reasons. Anonymous letters won’t be published. Please include a phone number.

2023-2024 BOARD OF DIRECTORS // Douglas Sorocco, President, OKC; Jon Fisher, Vice President OKC; Diane Salamon, Treasurer, Tulsa; Matthew Anderson, Secretary, Tahlequah; Jacquelyn Knapp, Parliamentarian, Chickasha; Marjorie Atwood, Tulsa; Barbara Gabel, OKC; Farooq Karim, OKC; Kathryn Kenney, Tulsa; John Marshall, OKC; Kirsten Olds, Tulsa; Russ Teubner, Stillwater; Chris Winland, OKC

The Oklahoma Visual Arts Coalition is solely responsible for the contents of Art Focus . However, the views expressed in articles do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Board or OVAC staff. Member Agency of Allied Arts and member of the Americans for the Arts. © 2024, Oklahoma Visual Arts Coalition. All rights reserved. View the online archive at ArtFocusOklahoma.org.

3

22

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

I’ve always enjoyed the idea that nurturing the eccentric aspects of our creative lives is good for us. It’s like cultivating eclectic tastes in music, art, reading, or whatever you like, and then discovering that the more you learn, the deeper your fascination, the more intricate and surprising the relationships between you and your favorite things (or your artistic process) turn out to be.

Thinking like that might keep us young, but it also reminds me of the fun part of watching our friends get older: they get weirder, too, as they become more and more themselves, sometimes gloriously so in their idiosyncrasies. The flipside is we have to assume it’s also happening to us. Time spares no one, so best to remember to laugh.

In all seriousness, I’m always most impressed by artists who pursue what seem like the most imaginative, original, and singular visions possible—the kind of work that makes us ask how did someone think of that? Rarely understood at first, art like that hardly ever bends to the status quo and often stands apart from political orthodoxy and even common sense. Pointedly resisting assimilation, that kind of art challenges us to stretch our notions of inclusion to embrace the non sequitur and quixotic, the decentered, the irreducibly multivocal and paradoxical along with just the downright strange.

I imagine that artists in this issue like Rachel Ann Kendrick (p. 22) and John Babbitt (p. 6) will make readers want to see more of their vibrant, edgy work as they keep pushing their unique frontiers. Many will agree that Benjamin Harjo, Jr. (p. 18), whose legacy is a state and national treasure, stands as a paragon of the ever-surprising master of a craft that could never be reduced to one thing. In our feature story, the Sunny Dayz Mural Festival (p. 14) shows how rejuvenating public spaces can expand opportunities for often-marginalized artists, and the displaced voices in Lisa Karrer’s SHELTER (p. 10) represent human experiences, far too common these days, that dare us to imagine ourselves well beyond our comfort zones.

In this summer heat, it’s worth remembering an open mind is one way of keeping the air moving. Hope you stay cool!

—John Selvidge

JOHN SELVIDGE is an award-winning screenwriter who works for a humanitarian nonprofit organization in Oklahoma City while maintaining freelance and creative projects on the side. He was selected for OVAC’s Oklahoma Art Writing and Curatorial Fellowship in 2018.

4

ROBIN

LETTER FROM THE EDITOR

CHASE

5 PREVIEW

6 IN THE STUDIO

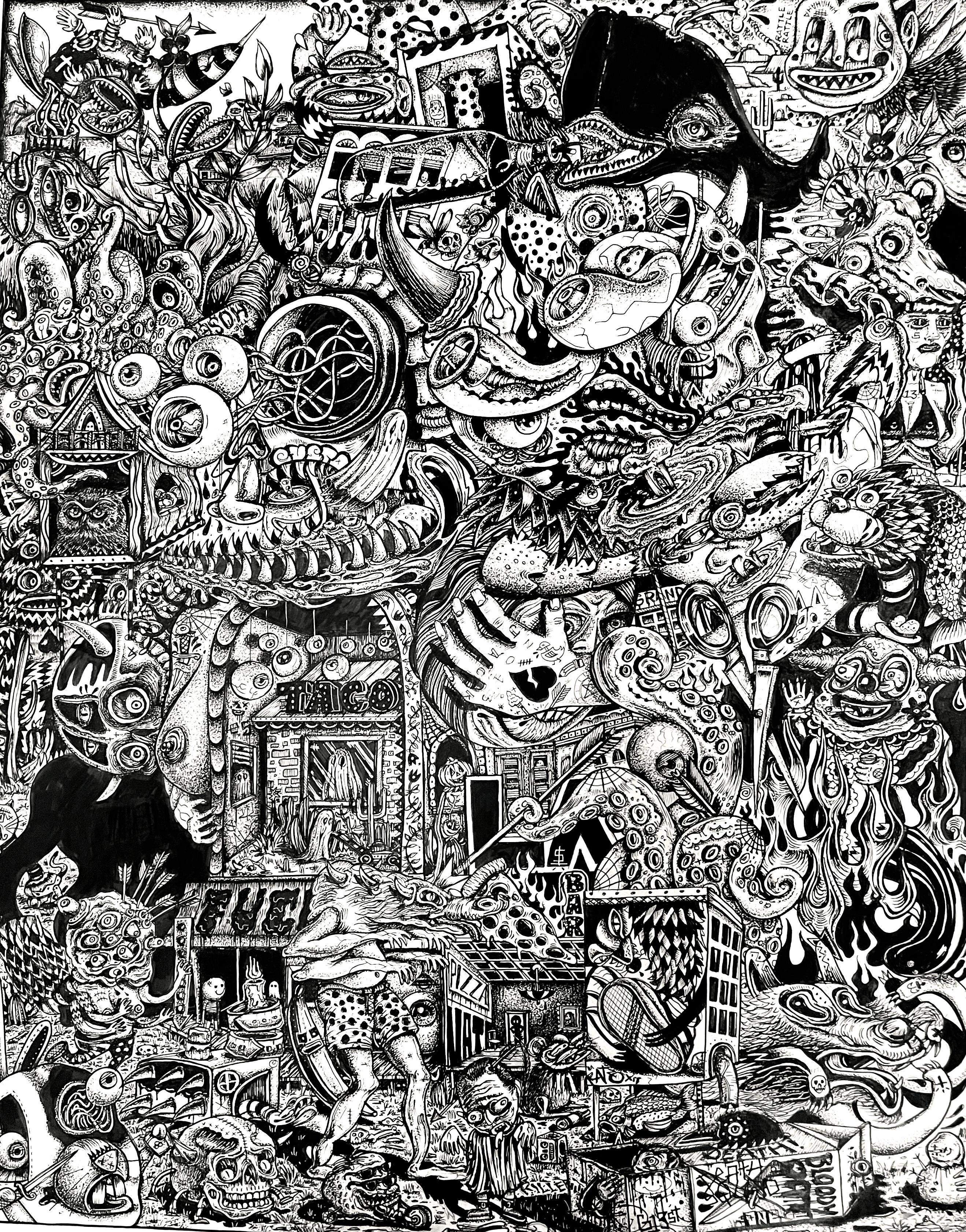

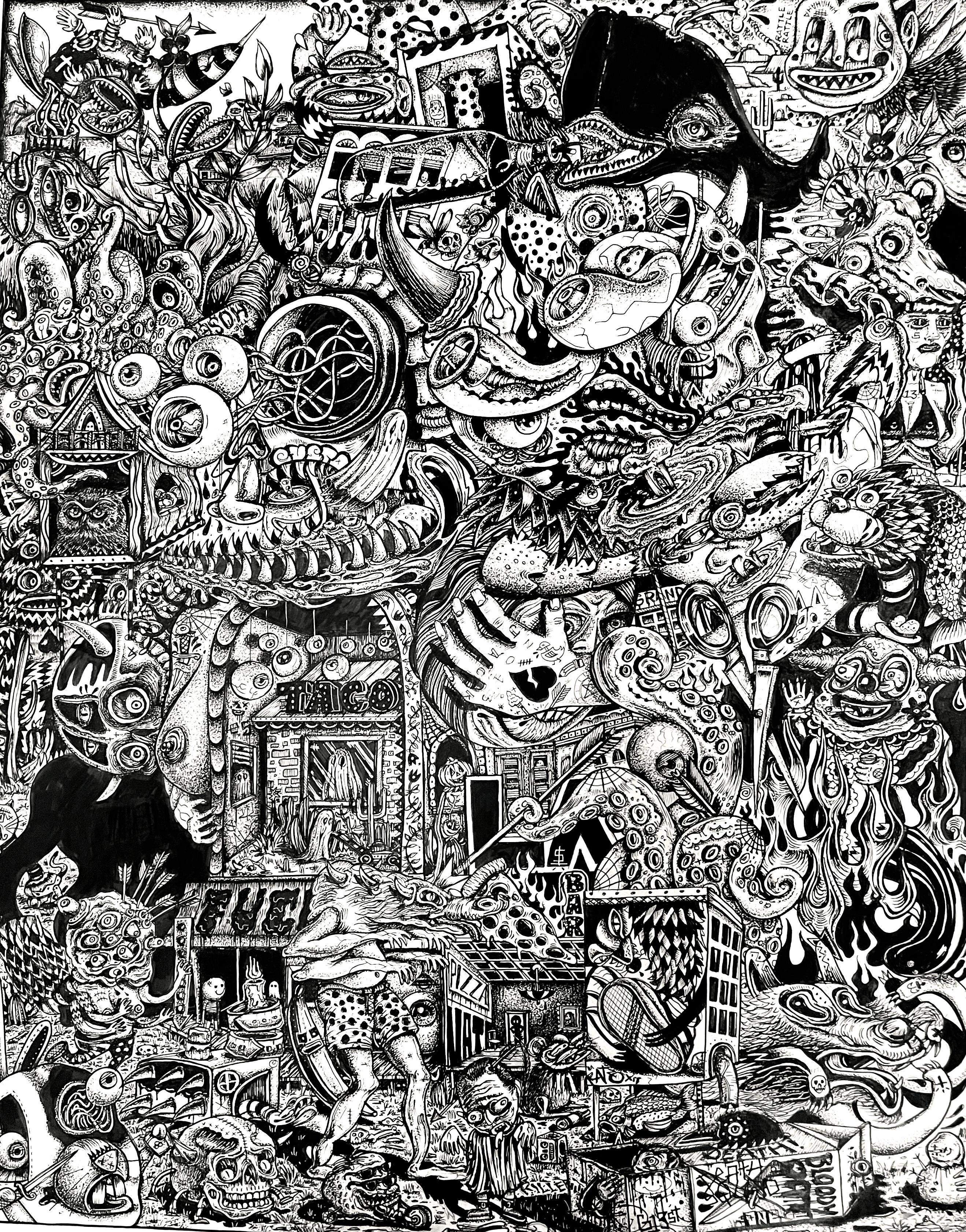

AMERICAN NIGHTMARES // IN THE STUDIO WITH JOHN BABBITT

Several months ago, after traipsing down Main Street for a while during one of Norman’s Second Friday Art Walks, I stopped into Oscillator Press. The intricate pen and ink works that my friend pointed out hanging on the walls intrigued me almost immediately. She introduced me to the artist, John Babbitt, who was as lively, thoughtful, and interesting in conversation then as he proved to be during our recent phone interview. I’m privileged to share some of our conversation here. — JS

First of all, how long do these remarkably dense and detailed pieces take?

For ones that measure 11 by 17 inches, about a month and a half. The bigger ones can take about three or four months. Every morning I spend a couple of hours before work on them, then a couple more hours after, plus as much as I can on my days off. I have to be regular in my schedule or else I feel guilty and terrible.

What kind of materials do you use?

I use Micron pens with archival ink, which lasts forever. I use several different tip sizes: bigger pens for outlining and filling, and then down to the finest, which is a .003 tip— basically the width of a human hair—for the most detailed work. I also use a giant magnifying glass with a lamp, but I recently got a new prescription for bifocals, so I’m using that magnifier less now.

What’s your process like? Do you start with an overall plan? How much do you improvise as you go?

I start with a big idea, often from other pieces, like making a minor figure a focal point in a new piece. For example, there’s a character I call “Pat Mink” who came from another piece to become central in Pat Mink Has Tits. In that one I wanted a demented city scene reminiscent of the weirdness and decadence of Venice Beach with palm trees and L.A. in the background.

First I’ll sketch major figures in light pencil to get the balance right, and then I’ll freestyle around them. Thematically, I have some sense of what’s going on, but it’s usually a lot about how I’m feeling at the time and is spontaneous. I’m able to correct mistakes as I go and blend. I never throw anything away.

There’s a lot of dream-like stuff in your work, both funny and nightmarish. What inspires your subject matter?

I’m sure they’re my inner demons that I’m working out. I know it’s dark, but it’s funny, too—and I’m told that’s pretty much my personality. I’m interested in death and disfigurement, definitely in a surreal frame of mind. I work in retail, so I see every day how shitty people can be, and they find their way into these creatures.

I’m probably too sensitive, but I get irritated with people. I see people acting terrible, locked in these boxes, trying to “make it,” and to me they end up looking like this. There’s so much negativity in the city, in my opinion. How run-down and plain a city can be…it’s a cold setting. A lot of my stuff is in the desert, too. Nothing really “lives” there, but it’s teeming with life—sharp and dangerous. The desert can kill you, but it’s majestic and beautiful.

Owls appear quite a bit in my work. I’ll be honest: they usually represent ex-girlfriends, sometimes in a way to feel good about, sometimes not. The owl is like a spirit animal for me—something majestic, nocturnal, and mysterious that’s watching very carefully. That might be something unconscious, maybe some self-figuring going on, because I’m a people-watcher. People are so interesting and quirky, so weird. I’m no exception—good god, just look at my stuff. I know there’s something paranoid in there about feeling like I’m being watched myself, too. All these eyes constantly, all through my work.

7

CONTINUED IN THE STUDIO

OPPOSITE

// John Babbitt, Monsters of retail, 2023, Micron pens on paper, 24” x 19” | All images courtesy of the artist

8

Did you have formal training? How did you get into doing work like this?

I’ve always liked making art since I can remember. My mom and my grandmother were both artists, so I’ve always been around it. No formal training—I took classes, but I usually found the instruction boring because I just wanted to do my own thing. But sure, in drafting classes I learned perspective and vantage points, also cross-hatching techniques. I was about 18 when I realized art was my thing and what I wanted to do.

What about your artistic influences? What artists have been important to you?

I’ve always been obsessed with Goya. His creatures have always intrigued me, also the darkness of his art, especially his later work where he was battling literal darkness due to his eyesight. Saturn Devouring His Children must have been insane when it was first seen. It makes me think he was an anarchist for his time. Goya scared the shit out of me, and I couldn’t stop looking at it.

And then, of course, comic books. You can see that R. Crumb is a big influence on me—his cartoonish lines and his comically disfigured humans. Robert Williams was a very direct influence, also Tim Burton. The Lowbrow movement that started in the 1950s is big for me: artists like Coop, Todd Schorr, Ed “Big Daddy” Roth. I love Lowbrow’s freedom, its larger-than-life aspects, and how everything is just thrown together.

How is your art evolving? Where’s it going next?

I’m working bigger now. Before, I only had the patience for small drawings, but now I’ve pushed a few to be 19 by 24 inches. They’re also getting tighter, with more detail, but the arrangements are more chaotic, so that’s interesting. I’m also messing around with lithographs now, which is a whole new ballgame, and it’s not easy. I’ve always wanted to do a zine and tell a story through my art. When I look at my pieces in the order they were done, there’s kind of a narrative logic that makes sense, so maybe I’ll try that.

You can see more of John Babbitt’s work on Instagram at @jawnbabbittart.

OPPOSITE TOP // John Babbitt, Pat Mink has tits, 2023, Micron pens on paper, 11” x 17”; OPPOSITE BOTTOM // John Babbitt, Interstate 40 is the eighth wonder of the world, 2024, Micron pens on paper, 19” x 24”; TOP // John Babbitt, Monsters of retail (detail), 2023; RIGHT // John Babbitt, Eleanor owl, 2022, Micron pens on paper, 17” x 11”

LIFE GOES ON //

LISA KARRER’S SHELTER AT OKLAHOMA CONTEMPORARY

by Olivia Dailey

A few weeks after the April 27th tornadoes, my husband and I drove to North Texas to visit family for the weekend. We had read about the devastation in Sulfur and elsewhere, but we were still shocked when we passed the Marietta Dollar Tree distribution center on I-35. The million square-foot warehouse was utterly destroyed, as if it had been bombed. Nearby billboards were snapped in half, and storage sheds were shredded and strewn across the landscape. Nights like April 27th make you confront the possibility that your home, your possessions, your life, might not be there in the morning. If your community is spared, you can quickly forget the threat and move on with your life…until you see debris across the highway that jolts you back to the reality that humans are vulnerable—that our basic needs like food, water, and shelter could be taken away at any moment.

SHELTER, an installation by multi-disciplinary artist Lisa Karrer at Oklahoma Contemporary in Oklahoma City, similarly jolts its audience. Comprised of eight “stations” of handmade, hand-painted ceramic miniatures of tents and other temporary dwellings for those seeking refuge, SHELTER brings the concept of displacement into tangible form.

Station 6, with its White Round Tents, is the most visually striking. It’s a desert scene with ceramics that imitate light, fabric tents that appear to hover delicately over the sand. Although SHELTER represents actual refugee camps across the globe, each station’s exact location is unspecified to leave things open to interpretation. One station could be read as Syria or Ukraine, while another could be Mexico or even right here in Oklahoma. The size of the shelters also invites interpretation. “It’s like Gulliver’s Travels, these are not toys, but it brings the adult into a space where they can use their imaginations,” Karrer said when I spoke with her. “SHELTER is supposed to allow the spectator to go where they wish when they wish. And the idea of the emancipated spectator is that the person who’s looking will create their

own poetry out of what they’re seeing. It leaves your brain free to take things in a nonlinear way.”

The scale of the installations is deceiving. A lot of life fits inside the little shelters. Karrer likes to mix digital media with physical media—which she calls “warm technology”— to better highlight the human condition. The ceramic structures also act as audio speakers and video projectors. Sound is piped in through the tablemounts, designed in collaboration with artist Bill Hochhausen, to tell the oral histories of real-life individuals who have experienced displacement. The audio loops include stories, songs, and poems in different languages. Some of the stories are recent, while others happened many years ago or have been told through generations. The videos, shown via pico projectors, play quietly inside some of the shelters, showing ordinary activities like praying, playing, and dancing. The videos operate somewhat like historical fiction, as some people in the videos are the same ones narrating, and some are performers or else museum or other associated nonprofit staff. One standout is a toddler who pushes a chair around a scene. Even in moments of unimaginable stress and terror, life goes on and people find some sense of equilibrium.

Originally from Buffalo, New York, Karrer experienced displacement when her childhood home fell under eminent domain to clear a path for a freeway. SHELTER opened in Buffalo, a refugee hub, where it explored the relationship between the city and its refugee communities. At Oklahoma Contemporary, SHELTER was recontextualized to include displaced residents in Oklahoma. To prepare the show, Karrer recorded new audio and video during a December residency at the Contemporary, which partnered with local nonprofits who work with refugees—the Asian District Cultural Association, the Latino Community Development Agency, Sooner Hope for Ukraine, and The Spero Project— to find people willing to share their stories. Sang Rem, a

11 REVIEW

CONTINUED

OPPOSITE // Lisa Karrer, Bombed Out Buildings (detail), 2020, Ceramic forms with embedded audio narratives and video projection, 62¼” x 60” x 60” | Ann Sherman

refugee from Burma who now works at The Spero Project, is featured in SHELTER’s audio and video and testifies that “no one wants to leave their home country.” Understandably, the situation has to be dire enough to give up the life and sense of self one knows.

Recent events have given new contexts to SHELTER since the show first opened in 2020. The wars in Ukraine and Gaza, notably, the U.S. military withdrawal from Afghanistan,

the hyper-politicization of the American southern border, and other conflicts around the world have put refugees at the forefront of our nation’s psyche, usually as a threat or problem. Refugees are often viewed from either a place of detachment or outright hostility, rarely with genuine sympathy. But world conflicts are inevitably created by humans. Even many “natural” disasters have been spurred by anthropogenic climate change.

REVIEW

12

TOP // Installation view of Lisa Karrer’s SHELTER including White Round Tents, Bombed Out Buildings, and Pup Tents. | Ann Sherman ABOVE // Lisa Karrer, Pup Tents (detail), 2020, Ceramic forms with embedded audio narratives and video projection, 52 ½” x 80” x 60” | Ann Sherman OPPOSITE // Lisa Karrer, Floating Tent Tops, 2020, Ceramic forms with embedded audio narratives, dimensions variable | Olivia Dailey

I didn’t see the Buffalo installation of SHELTER, but photos from it—featured on Oklahoma Contemporary’s website at the time of this writing—are much darker and moodier, transforming the art. In particular, Floating Tent Tops looks nearly unrecognizable when compared to how it looks in the Contemporary’s bright lobby. An argument could be made for either setup: Buffalo’s iteration was more dramatic, whereas OKC’s is starker and rawer in the bright, ambient light. In both versions, the audio and visual components are intimate rather than immersive. A lot is packed into these dioramas, and each station has a page on the Contemporary’s website that includes its video and audio elements as well as transcripts. The result is a little overwhelming, especially if viewed on a mobile device. I found myself wondering about ways to guarantee more people could experience these human stories beyond relying on QR codes—like a small theater room, for example—in addition to their ceramic delivery.

SHELTER is part of a larger theme of displacement and immigration explored by Oklahoma Contemporary this

year. By the time of this issue’s publication, there will be a few weeks left to view the also excellent HOME1947, by renowned Pakistani-Canadian filmmaker Sharmeen Obaid Chinoy. But since SHELTER is on display through the end of the year, there is plenty of time to visit and revisit this moving exhibition, whenever you might feel the need to examine your own sense of security.

SHELTER can be experienced at Oklahoma Contemporary in Oklahoma City through January 6, 2025. Please visit oklahomacontemporary.org/exhibitions/current/shelter to learn more.

OLIVIA DAILEY earned a B.A. in Journalism from the University of Oklahoma. She works as a program manager at a transportation research center in Norman and is a frequent Art Focus contributor.

13 REVIEW

A WIDER LENS OF INCLUSION // IN PONCA CITY WITH THE SUNNY DAYZ MURAL FESTIVAL

by Helen Opper

Most people would agree that public art plays a crucial role in a community’s well-being. Like many institutions, public art has historically been dominated—both in managerial and artistic capacities—by men. With some exceptions, women and gender minorities have been excluded from this space through lack of opportunity and lack of fair compensation. Simply put, the status quo for public art does not accurately reflect the reality of the diverse world in which we live—in Oklahoma and beyond—nor does it allow for the flourishing of an equity-based artistic ecosystem. In response, several artists and arts workers have dedicated their professional practices to advocating for visual art’s power to make way for more equal representation and to effect cultural and political change.

Sunny Dayz Mural Fest is Oklahoma’s first and only mural festival dedicated to women and non-binary artists. Oklahoma City-based artist Virginia Sitzes conceptualized Sunny Dayz after years of working as a professional muralist. To help level the playing field, Sitzes and her team of local artists and community organizers formed Sunny Dayz as a venue for women and nonbinary artists to showcase their professional talents through murals. Also a 501(c)3 nonprofit, Sunny Dayz consists of a weeklong period of mural painting by local, national, and international artists that culminates in a free, family-friendly daylong public festival. In addition to the murals, the festival features performers, an extensive vendor market, kids’ activities, and local food trucks.

The festival travels to a different community in Oklahoma each summer to expand access to public art in both rural and urban areas. Since Sunny Dayz’ first iteration in 2021 in Oklahoma City’s Britton District, it has been held in downtown Edmond, Tulsa’s Pearl District, and most recently, just weeks ago on June 1, in Ponca City.

As an organization, narrowing gender-based representation and wage gaps through creating public murals is Sunny Dayz’ primary focus. Sunny Dayz pays all artists and

performers fair wages for their work; historically, mural festivals have underpaid or not paid participants at all, which contributes to unequal access to mural painting opportunities. In addition to supporting women and nonbinary artists through paid painting opportunities, Sunny Dayz supports emerging, young, and local artists by dedicating a set amount of wall space to “newbie” artists, professional muralists, artists from the host community, and collaborative groups.

Sunny Dayz also features a strong educational component through a teen mentorship program that pairs Oklahoma teens interested in public art with professional, working muralists. Mentees are assigned to professional artists while they paint during the week leading up to the festival and learn painting ideas and techniques from their muralist mentors. During the festival itself, mentees create their own murals for the public to enjoy as live painting events. For many mentees, this is their first chance to contribute to a mural and to see what it can look like to be a professional artist. Many past mentees have gone on to study art in college and pursue mural-making as a career, and a few have participated as muralists in later iterations of Sunny Dayz.

The festival emphasizes collaboration. If artists are interested in collaborating, Sunny Dayz’ selection committee creates teams, but how teams of artists design and work on their murals is entirely up to them. Both practicing artists, Ponca City-based Alena Rae Jennings and Oklahoma City-based Alicia Smith worked together to create their first mural at Sunny Dayz, using a combination of spray paint and wall paint applied with brushes. Their mural Kinship pays homage to their connection to the land and indigenous stewardship of the Oklahoma prairie. Featuring a stunning Oklahoma landscape of native grasses and flora, migratory monarch butterflies, and a brilliant, blazing sky resulting from traditional prescribed agricultural burns, Kinship testifies to the beauty of Oklahoma’s land, its ability to provide sustenance, and the importance of connecting with it.

FEATURE 14

CONTINUED

ABOVE // Alena Jennings and Alicia Smith, Kinship, All murals 2024, downtown Ponca City | Bethany Young BELOW // Nico Cathcart and Valerie Rose, a wider lens…(through which to see the world) | Bethany Young

ABOVE // Alena Jennings and Alicia Smith, Kinship, All murals 2024, downtown Ponca City | Bethany Young BELOW // Nico Cathcart and Valerie Rose, a wider lens…(through which to see the world) | Bethany Young

ABOVE // Delia Miller, Flight Path | Bethany Young; BELOW // Amber Andersen and Sophy Tuttle, Cicada Cadence | Sarah Fish OPPOSITE // Heidi Ghassempour, Emily “Jax” Hoebing, and Iryna Snizhenko, They belong in the garden. | Iryna Snizhenko

ABOVE // Delia Miller, Flight Path | Bethany Young; BELOW // Amber Andersen and Sophy Tuttle, Cicada Cadence | Sarah Fish OPPOSITE // Heidi Ghassempour, Emily “Jax” Hoebing, and Iryna Snizhenko, They belong in the garden. | Iryna Snizhenko

Based in Orlando, Florida, Delia Miller is currently in flight school to become a pilot in addition to working as a professional muralist, showing how she has already pushed past traditional boundaries in her nascent career. Her mural Flight Path features a self-portrait of her younger self holding a model plane and surrounded by colorful, tropical flowers. A can of paint with a brush on top and a vibrantly multicolored bird fill the remainder of the foreground, and an airfield runway dominates the background, symbolizing Miller’s uncommonly paired goals. One of the two youngest professional artists in the festival, Miller painted every inch of the mural by hand.

Nico Cathcart and Valerie Rose, deaf artists based respectively in Richmond, Virginia, and Chico, California, brought the gift of a new dimension of accessibility to Sunny Dayz. Despite very different backgrounds—Cathcart grew up in a family that used lipreading to communicate, whereas Rose’s first language is American Sign Language— they collaborated to create the beautiful and meaningful a wider lens…(in which to see the world). This mural depicts Rose signing the words for “open mind” in ASL against a purple and blue background among neon outlines of begonia blossoms. The artists explained that the begonia is a symbol of good communication—an apt idea when considering the different ways members of the Deaf community and the community at large communicate. Through pre-festival accessibility training with the Sunny Dayz team, sharing basic ASL signs on site, innumerable personal conversations, and ultimately through their mural,

Cathcart and Rose enlightened and opened the minds of all who engaged with them and their art. The two artists met for the first time at Sunny Dayz, but they formed a strong bond through their art and plan to work together in the future.

Honoring everyone’s experiences while fostering growth, collaboration, and open-mindedness is Sunny Dayz’ ultimate goal. Our festival team is grateful to all our hosts and to all the artists who participated for sharing their work, their stories, and for enriching Ponca City as well as our wider community.

Murals from 2024’s festival will be visible in downtown Ponca City for years to come. Sunny Dayz Mural Festival has scheduled its fifth year to take place in Oklahoma City’s Calle Dos Cincos Historic Capitol Hill District on May 31, 2025. You can learn more about the festival at sunnydayzmuralfest.com

HELEN OPPER is an art appraiser, advisor, curator, and educator based in Oklahoma City. She studied art history at University of California, Berkeley, and earned her M.A. in Museum Studies from New York University. She specializes in postwar, contemporary, and emerging art with a focus on activist, feminist, and collective art practice, public art and murals, and American avant-gardism. Currently vice president of Sunny Dayz’ board of directors, Opper has been with the organization since its inception.

17 FEATURE

JOY UNCOMPROMISING // BENJAMIN HARJO, JR . AT THE OSU MUSEUM OF ART

by Molly Murphy Adams

The artworks in the retrospective benjamin harjo, JR.: from here to there reinforced something I already knew about the artist. Harjo had a capacity to be very joyful about serious things and deeply serious about joyful things. Ceremony, preservation of culture, integration into modern society while staying authentic to self, carrying a weighty history, surviving as an artist in a commercial world—these are serious matters that he approached with an abundance of joy. Friendship, laughter, celebrating identity and resilience, playing with color, pattern, and shape—these are joyful endeavors that Harjo approached with gravity.

Harjo has an enduring reputation as a master artist and a dedicated mentor and activist in the Native art community. The Barbara and Ben Harjo team initially introduced me to the community of artists in Oklahoma, as well as to their philosophy of collaborative work and inclusion that aimed to increase opportunities for all artists. These introductions led me to relocate to Oklahoma from Montana fifteen years ago and participate in a vibrant arts culture shaped by the example Harjo embodied.

A quality of Harjo’s legacy that can be overshadowed by his larger-than-life personality was his artistic commitment to authentic culture, self, and style. Native artists in the last quarter of the 20th century experienced pressure to assimilate and create artwork satisfying mainstream expectations in a pan-Native style, one subordinate to romantic western narratives. Think headdresses, warriors on horseback, and the “End of the Trail” motif. Harjo rejected these tropes and succeeded in creating art and pursuing an arts career deeply rooted in tribal identity and visual traditions. Harjo created works that were deeply Indigenous, modern, and individual all at once and proved an enduring example for younger artists.

The 86 original works on exhibit at the Oklahoma State University Museum of Art range from his early works from the 1970s to Harjo’s final works in the early 2020s. They include printmaking, ink, gouache, and mixed media. All

are works on paper, and Harjo’s signature style of precision, pattern, and expressive movement remains constant through media and size. Figures and shapes are comprised of fields of saturated color and complex geometric patterns in motion, often accented in black ink. Harjo’s style is typified by works in gouache on paper, executed with such masterful technique that the surface can appear mechanically printed, rather than laboriously hand painted. Harjo makes it look easy, even fun, but gouache as a medium is an instructor in humility. (If you’re curious about gouache, I suggest you try painting a checkerboard pattern in contrasting colors. If you make it past two hours without crying or ripping the paper in two, congratulations.)

In medicine bundle, one of the larger works on view, a central shape dominates the composition: an imperfect oval crossed by lateral wedges and narrow rectangles. The bundle floats, overlapping a ground of checkered blue and white and a sky of negative space with floating stars and celestial objects. In medicine bundle Harjo renders a spiritual object created and cared for by community, a sentient object radiating power. His depiction portrays its function and gravitas not by representing the contents or the appearance of the bundle, but by using patterns that infuse it with dynamic color.

The bundle is more than the parts assembled; it is a composition in which, in the uniting of many patterns, the parts become a whole. The medicine bundle bridges the ground and sky, the real and imagined, the communal and the personal. medicine bundle exemplifies how Harjo used pattern as a subject, rather than a mere filler behind or around the subject. Balancing subject and pattern is an important aspect of Native worldview that Harjo often deploys in his artwork, bringing us an Indigenous perspective where the pattern is not visual padding, but an integral part of the message.

In contrast to the large-scale abstract rendering of medicine bundle, we can look to miniatures to see the full range of Harjo’s mastery of medium and narrative. The painting the CONTINUED

18 PREVIEW

OPPOSITE // Benjamin Harjo, Jr. (Absentee Shawnee/Seminole, 1945-2023), the moon or the sun, 2005, gouache on paper, 39 5/8” x 26 3/4” | Phil Shockley

procession is a meager three inches square, yet it contains an expansive scene. A line of female figures in dance regalia is set against an imagined space with a landscape inset, as if a framed painting were hung in an abstract environment. Each figure is very much an individual with identifiable beadwork, design, and expression. The collection of miniatures in the exhibit invites and requires close examination and, I am certain, will leave viewers shaking their heads in wonder. In

these tiny paintings we have a microcosm of Harjo’s talent where figures, landscape, and abstraction create monumental ideas in miniature.

dreamcatcher is a lyrical example of Harjo extending an imaginary figure as an invitation to his interior personal world, even a window into his process. The scene is simple: a Seminole woman whose body is abstracted as a geometric

20 PREVIEW

shape supports stacked rows of bead necklaces on her elongated neck. Her face in profile is serene but potent, and her oversized hands remind us that she is a figure of dreams, even while the hints of dress, hairstyle, and expression root her within Seminole tradition. An elevated, outstretched hand is raised against the negative space of the paper, and a stream of geometric shapes float from left to right over the figure’s head and into this hand. The figure catches dreams— Harjo’s dreams, dreams of shape and movement.

Benjamin Harjo, Jr. left a legacy of personal relationships and professional accomplishments that can be understood as enmeshed and magnified to create a larger, more authentic whole from their parts. His artwork was deeply rooted in his sense of time and place, and he felt no need to alter, minimize, shift, or diminish it to fit. Harjo took great pride in being from Oklahoma, in his tribal identity as a Shawnee and Seminole citizen, as an Oklahoma State University alumnus, and as an artist. The retrospective at the OSU Museum of Art showcases the range of his talent and humanity over a career that reached far beyond his origins in Oklahoma. The exhibition is a fitting and tender tribute made possible by

loans of work spanning decades and distance from many enthusiastic collectors and fans. Take in from here to there and share in the imagination and legacy of Benjamin Harjo, Jr.—a master artist intimately concerned with the serious business of joy.

benjamin harjo, JR.: from here to there will be on view at the OSU Museum of Art through September 7. Please visit museum. okstate.edu/art/benjamin-harjo-jr for more information.

MOLLY MURPHY ADAMS (Oglala descendent) was born in Montana and earned a Bachelor’s degree in Fine Art from the University of Montana and a Master’s in Art History from Oklahoma State University. She has made Tulsa her home for nearly fifteen years while working as an exhibiting artist, art appraiser, art historian, and beadworker in her indigenous community. Murphy Adams focuses on indigenous beadwork in her many roles as researcher, teacher, and community maker.

21 PREVIEW

OPPOSITE // Benjamin Harjo, Jr., the procession, 1997, gouache on paper, 3” x 3” | Collection of Melinda and Paul Cox. Photo by Gary Lawson LEFT // Benjamin Harjo, Jr., dream catcher, 2004, pen and ink, colored pencil on paper, 10” x 10” | Loan Courtesy of First American Museum. Photo by Gary Lawson

RIGHT // Benjamin Harjo, Jr., medicine bundle, 2015, gouache on paper, 27” x 20” | Collection of Joe and Valerie Couch. Photo by Gary Lawson

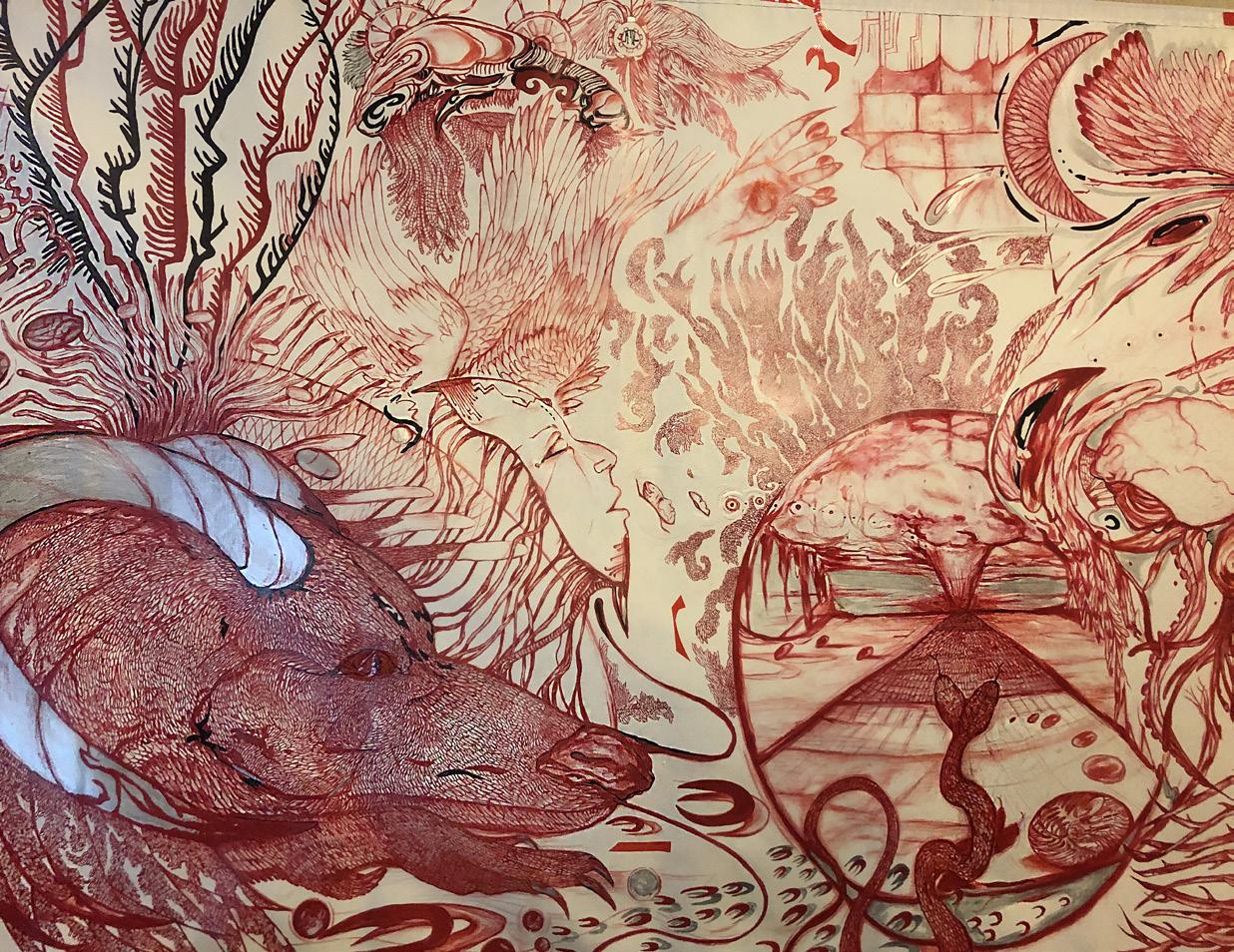

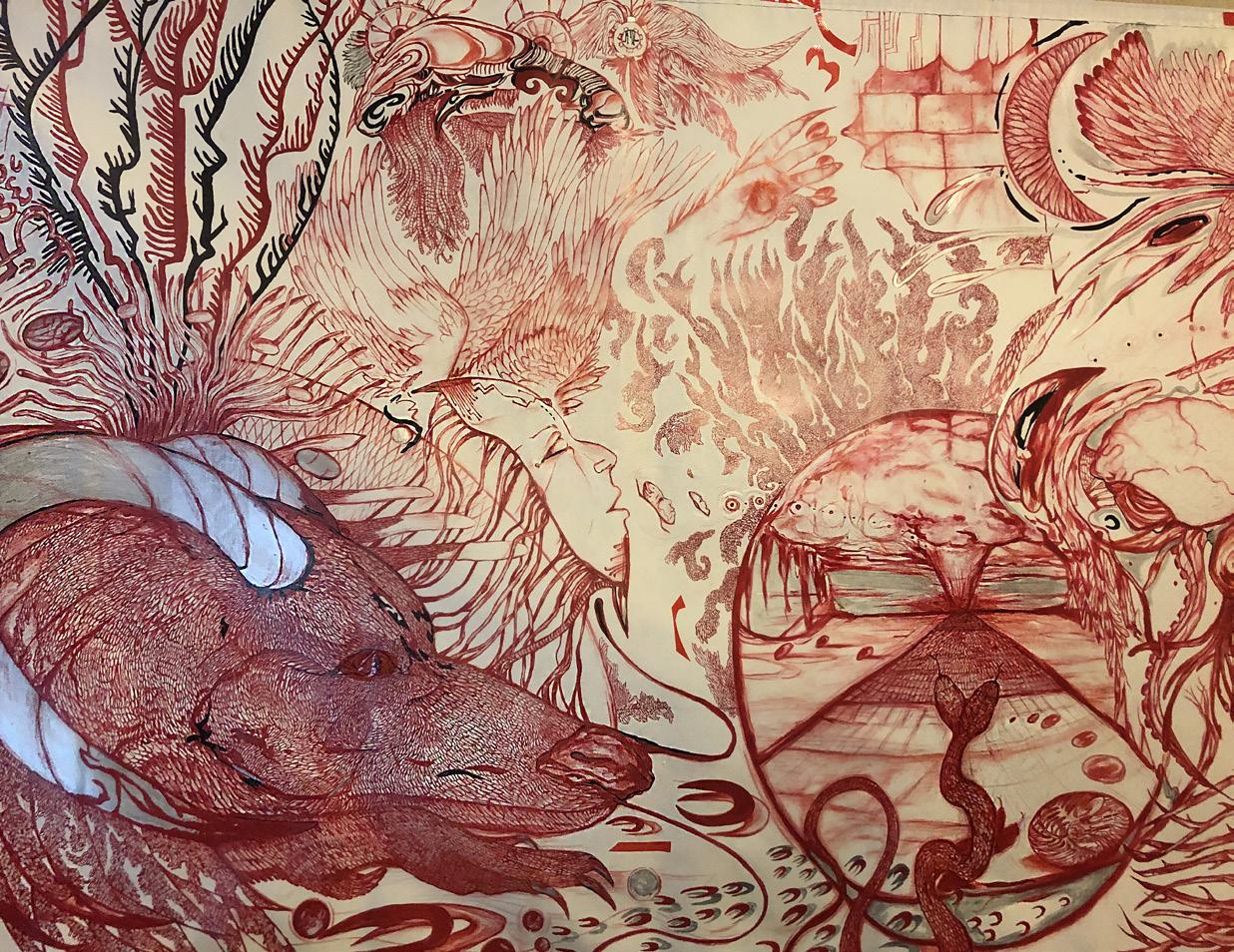

SURREAL HORIZONS // RACHEL ANN KENDRICK AT POSITIVE SPACE TULSA

by Sallie Cary Gardner

While working in a building in downtown Oklahoma City, artist Rachel Ann Kendrick came upon a cache of large, discarded plastic signs intended for use in a grocery store. Each sign had at least one serious misprint on it, and they were headed for the dumpster. Kendrick rescued them, covered them in gesso, and made a series of paintings in her colorful, surreal, abstract style.

In July, those paintings can be seen by the public for the first time in Kendrick’s multimedia installation Sacred Alchemy Visions: A Fusion of Art, Sound, and Robotic Realms at Positive Space Tulsa. The installation promises to entertain visitors in a variety of ways.

When we spoke in May, Kendrick told me she will hang her large abstract paintings from the ceiling with fishing line, creating the illusion of floating paintings that viewers can stroll through. Kendrick said she weaves universal archetypal imagery into all her work. “I feel like this arrangement came to be as a symbol of humanity’s journey into the future,” she said. While walking through her floating paintings, viewers will listen to a soundtrack of electronic music that Kendrick created with AI. Visitors will also be able to watch a suspended robot, similar to a bird, create abstract paintings with its leglike appendages.

The robot’s name is Makie 1, and Kendrick put her together with found objects collected over several years. If the stereotype of a robot looks like R2D2, Makie 1 is the exact visual opposite, with her red feathers and gold-colored upper body. She will be suspended from a special stand and move her feather-covered legs to paint a canvas. “It’s art that can create its own art, which is a really interesting concept to think about as an artist,” Kendrick said.

She calls her paintings “a moving dream” and is inspired by the works of Judy Chicago, Clyfford Still, and Salvador Dali— also Agnieszka Pilat, who makes robotic dogs as part of her art practice.

It took Kendrick six months to build Makie 1, and she plans to follow her with more robots. She learned how to build robots by watching YouTube videos and asking for advice from her mechanically talented brother. “I must have broken the thing 50 times before I finished it,” Kendrick said. “Creating art has really taught me more about myself, and I found that to be an almost spiritual aspect of putting everything together.”

Kendrick based the palettes for her paintings on the colors of the rainbow. “The rainbow theme came to me as something that would show my connection as a lesbian to the gay community as expressed in my art,” she said.

Kendrick’s paintings depict fantastical renderings of parts of humans, animals, and birds, with a wing here and a paw there against a background of moving clouds or a wind tunnel. Viewers may even find human faces in the natural forces whirling around. In some of the paintings. Kendrick said that transformation has been an emergent theme.

Her two Rainbow Radar paintings each measure four by nine feet and serve as doors to the floating installation of equally large paintings. Here, Kendrick uses all the colors of the rainbow in lively patterns reminiscent of Abstract Expressionism that show their brush marks. The word “radar” in the title was inspired by Kendrick’s wife, who is a storm chaser. “She is always showing me the weather radar on her phone. It’s stuck in my head,” she said.

The painting Blue, Gold, and Black is more typical of Kendrick’s work and is executed in a surrealistic style with a drawing of a woman’s face in the center. Kendrick modeled the face after a self-aware robot she saw on the Internet. Almost hidden beside the central face are two other faces which represent ghosts.

Hiding things in paintings is a habit of Kendrick’s, and gallery goers will likely enjoy finding these hidden treasures. As for

CONTINUED OPPOSITE // Rachel Ann Kendrick, Makie 1 (detail), 2024, electric lights, small motors, wires, plastic, silicon, vinyl, metal, acrylic paint with clear finish, plastic mold of the artist’s teeth, rhinestones, 60” x 24” with base and stand | All images courtesy of the artist

22 PREVIEW

TOP // Rachel Ann Kendrick, Rainbow Radar 1 & 2, 2024, acrylic on gesso-prepped plastic sign, each 60” x 84”; LEFT // Rachel Ann Kendrick, Red, Black, and White (detail), 2024, acrylic on gesso-prepped plastic sign, colored pencil, red transparent break light vinyl, 60” x 84”; ABOVE // Rachel Ann Kendrick, Makie 1

TOP // Rachel Ann Kendrick, Rainbow Radar 1 & 2, 2024, acrylic on gesso-prepped plastic sign, each 60” x 84”; LEFT // Rachel Ann Kendrick, Red, Black, and White (detail), 2024, acrylic on gesso-prepped plastic sign, colored pencil, red transparent break light vinyl, 60” x 84”; ABOVE // Rachel Ann Kendrick, Makie 1

those misprinted advertisements, Kendrick didn’t completely cover them when she put gesso on them—she left some of her favorite words hidden in plain view. For example, the word “soup” can be read in one painting as a nod to Andy Warhol.

Nicole Finley Alexander, owner and gallerist of Positive Space Tulsa, said she and Kendrick have been in conversation for a year about the show. “She blew me away,” Alexander said. “Her vision is interesting, and it’s been wonderful to see it happening.” In addition to a gallery and event space, Positive Space Tulsa serves as a resource center for women. Alexander partners with the Take Control Initiative to provide Tulsa women free birth control resources, including the “morning after” pill. In her representation, Alexander spells women with an “X” as “womxn” to include women who are nonbinary, gender-fluid, gender-queer, or agender.

Kendrick’s intends her installation to let visitors experience a journey away from the tradition of hanging flat paintings on a flat wall and instead lead them through her installation

of floating paintings that together can be understood as creating a giant sculpture. “Creating art is sacred to me, but I also want the installation to create a space that feels special and sacred to viewers who come to see it,” Kendrick said.

Sacred Alchemy Visions: A Fusion of Art, Sound, and Robotic Realms can be seen from July 6 through July 27 at Positive Space Tulsa, located at 1324 E. 3rd Street. Gallery hours are Thursday from 6 p.m. to 8 p.m., Fridays from 5 p.m. to 9 p.m., and Saturdays from noon to 5 p.m.

SALLIE CARY GARDNER is retired from a long career in writing and public relations. She enjoys contributing to the Oklahoma arts scene through her work with the Tulsa Artists’ Coalition Gallery and in collaboration elsewhere. She is a frequent contributor to Art Focus.

25 PREVIEW

Rachel Ann Kendrick, Blue, Gold, and Black (detail), 2024, acrylic on gesso-prepped plastic sign, colored pencil, 60” x 84”

INTERMEDIA – OF CELLULOID AND FABRIC // AN INTERVIEW WITH CURATOR CATHERINE SHOTICK

During the last week of May, I was fortunate enough to sit down for a conversation with Catherine Shotick, guest curator of the retrospective exhibition Edith Head: Hollywood’s Costume Designer, visible at the Oklahoma City Museum of Art through September 29. It was a privilege to learn more about this accomplished artist in film who, from the 1920s to the 1980s, worked on more than 400 movies and presided over the costume design departments at Paramount and Universal Studios. — JS

What does a designer like Edith Head have to consider when designing costumes to be filmed?

One of the top considerations for costume designers is how the costumes appear on screen. Edith Head started her costume design career at Paramount in the 1920s when films were black and white. She therefore had to create visual interest in the costume designs in other ways besides color, using fabrics that shimmered and sparkled, or patterns with highly contrasting colors that would display more clearly on a greyscale screen compared to colors similar in value. Interestingly, this is why she wore dark tinted glasses—to see how costumes would look in black and white. Once color film was invented, she had to consider the colors of the clothing and how they fit into the overall color scheme of the set design.

What kind of working dynamics did Edith Head have with directors?

Edith Head collaborated with a lot of directors over her long career and had to learn how to work with different Hollywood personalities. She had a strong working relationship with Alfred Hitchcock. They worked on eleven films together from 1946 to 1976, and though she conceded that “Hitch” wasn’t exactly easy to work with, they were both masters of their respective crafts, had similar exacting personalities, and valued each other’s expertise.

Edith Head won her first Oscar award in 1949 for her costume designs for The Heiress, a film that held a special place in her career. She said it was “the most perfect picture I have ever done,” and she felt this way because of how much she valued William Wyler’s directorial vision. He was adamant that all costumes for the 19th century period film be authentic to the time, down to the last detail. Edith Head worked tirelessly on this film, studying historic clothing at museums and archives so she could design authentic period costumes.

On the other hand, she said that working with Cecil B. DeMille for the film Samson and Delilah was her “least favorite film experience.” This biblical epic film had stunning stars, sex appeal, and drama, but for Head, it lacked the key element of authenticity. DeMille also divided the costume design for the stars among five designers, a division she did not appreciate. Furthermore, DeMille wanted a sexy film, but Head had to battle the Hays Code—strict guidelines for the film industry that determined what could be shown on screen, but also promoted traditional values. Profanity, graphic or realistic violence, suggestive nudity, and sexual explicitness were all prohibited. For costume design, that meant no cleavage or semi-nudity.

Can you think of a specific ensemble that contributed to a film’s thematic concerns? For me, the dresses in Vertigo come immediately to mind.

We have one costume from Vertigo: the dark navy dress Kim Novak’s character Madeleine Elster wore as she jumped into the cool waters beneath the Golden Gate Bridge, drawing James Stewart’s Scottie Ferguson to dive in to save the possessed blonde beauty. Edith Head had to design a dress that would be practical for Novak to wear when soaking wet, and it also had to fit within the overall vision of Alfred Hitchcock, who wanted the disturbed Madeleine Elster to “look as if she just stepped out of the San Francisco fog – a woman of mystery and illusion.”

Do you have a favorite ensemble in this exhibition? One that makes a particular film important, remarkable, or special to you?

My favorite costume in the exhibition will always be Grace Kelly’s black organza dress for Hitchcock’s Rear Window Edith Head and Grace Kelly worked on four films together and formed a long-lasting friendship. In fact, Head once said if she had to pick a favorite actress, it would be Grace Kelly. When I watch Rear Window, I imagine Edith Head must have had such fun designing for that script, with Grace Kelly playing a high-fashion magazine editor. The entire wardrobe for this film is impeccable, timeless, and elegant. If I could wear one costume from the exhibition, it would be this dress!

26 INTERMEDIA

27 INTERMEDIA

CLOCKWISE FROM TOP LEFT // William Wyler, The Heiress, 1949; Grace Kelly, promo shot for Hitchcock’s Rear Window, 1954; Kim Novak in Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo, 1958; Grace Kelly and Edith Head during production of To Catch a Thief, 1955. Margaret Herrick Library, Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

ANNUAL JURIED EXHIBITS

Providing artists opportunities to connect with the community

E O

SMALL ART SHOW

Apply August - October | Exhibit in November

PAA MEMBER'S’ SHOW

Apply November - January | Exhibit in February

THE MARCH SHOW

Apply January - February | Exhibit in March

PRINT ON PASEO

Apply May - June | Exhibit in July

PASEO PHOTOFEST

Apply July - August | Exhibit in September

P A S E O A R T S A S S O C I A T I O N

P

T S &

R E A T I V I T Y C E N T E R

A S E O A R

C

3 0 2 4 P A S

PIZZA AS BIG AS YOUR FACE NY STYLE PIZZA BY THE SLICE ORDER ONLINE!

An eclectic fusion of works by 175 Oklahoma artists and live entertainment for a memorable one-night-only art event. OKC Farmers Public Market 12x12OK.Org SEPTEMBER 20th, 2024

RECEPTION & ARTIST PANEL

AUG 1, 2024 | 5PM–8PM

EXHIBITION DATES: JUN 22–SEP 14

GAYLORD-PICKENS MUSEUM

OKLAHOMA CITY, OK

30 PREVIEW

MEMBERS SHOW OVAC MEMBERS SHOW

OVAC

okcontemp.org | 11 NW 11th St., Oklahoma City

Detail view of Slum with Sewer (2020) by Lisa Karrer. Photo by Ann Sherman.

Non Profit Org. US POSTAGE P A I D Oklahoma City, OK Permit No. 113 1720 N Shartel Ave, Suite B Oklahoma City, OK 73103

learn more.

Visit ovac-ok.org to

ABOVE // Alena Jennings and Alicia Smith, Kinship, All murals 2024, downtown Ponca City | Bethany Young BELOW // Nico Cathcart and Valerie Rose, a wider lens…(through which to see the world) | Bethany Young

ABOVE // Alena Jennings and Alicia Smith, Kinship, All murals 2024, downtown Ponca City | Bethany Young BELOW // Nico Cathcart and Valerie Rose, a wider lens…(through which to see the world) | Bethany Young

ABOVE // Delia Miller, Flight Path | Bethany Young; BELOW // Amber Andersen and Sophy Tuttle, Cicada Cadence | Sarah Fish OPPOSITE // Heidi Ghassempour, Emily “Jax” Hoebing, and Iryna Snizhenko, They belong in the garden. | Iryna Snizhenko

ABOVE // Delia Miller, Flight Path | Bethany Young; BELOW // Amber Andersen and Sophy Tuttle, Cicada Cadence | Sarah Fish OPPOSITE // Heidi Ghassempour, Emily “Jax” Hoebing, and Iryna Snizhenko, They belong in the garden. | Iryna Snizhenko

TOP // Rachel Ann Kendrick, Rainbow Radar 1 & 2, 2024, acrylic on gesso-prepped plastic sign, each 60” x 84”; LEFT // Rachel Ann Kendrick, Red, Black, and White (detail), 2024, acrylic on gesso-prepped plastic sign, colored pencil, red transparent break light vinyl, 60” x 84”; ABOVE // Rachel Ann Kendrick, Makie 1

TOP // Rachel Ann Kendrick, Rainbow Radar 1 & 2, 2024, acrylic on gesso-prepped plastic sign, each 60” x 84”; LEFT // Rachel Ann Kendrick, Red, Black, and White (detail), 2024, acrylic on gesso-prepped plastic sign, colored pencil, red transparent break light vinyl, 60” x 84”; ABOVE // Rachel Ann Kendrick, Makie 1