6 minute read

Off-Grid and Off-Road: Touring Mongolia without a Net, Dean Karalekas

Off-Grid and Off-Road:

Touring Outer Mongolia Without a Net

Outer Mongolia in the 1990s was not a tourist destination. Entry visas were difficult to secure, and there was very little tourism infrastructure outside of the capital, Ulaanbaatar. The Berlin Wall had fallen, but a Communist party was still in power here. The grocery store shelves were still largely bare, and shopping consisted primarily of the stolid State Department Store and a black market that popped up occasionally in the northern part of the city.

In those days, there was little for the foreigner to do to pass the time other than drinking to excess at the Bayangol Hotel bar, frequented by mining executives, freedom fighters, and smugglers working the China-to-Eastern Europe route. This is where I spent most of my time in those days, and I found ready acceptance. Being alone on the edge of the world is an insular existence, and any new faces like mine were enthusiastically welcomed (read: interrogated) by the older hands—new grist for the rumour mill.

It was here that I met Mike and Mike, a pair of German adventurers cursed with the same name. After conducting various experiments on who could imbibe more alcohol, Germans or Canadians (Germans, it turned out), we were about to go our separate ways at closing time when they announced that they were heading south the following morning, to the Gobi Desert, and would I like to come along, to share the cost. I readily accepted their kind offer, and rushed back to the apartment I was renting to pack. I only hoped that, once the effects of the alcohol wore off, they would remember inviting me.

The following morning, we met up as arranged and boarded the train to Sainshand, the capital of Dornogovi Province. There we met our guide Oktai and driver Altan, and threw our baggage in what was to be our home and chariot for the next week: a UAZ 469 Russian jeep.

At the time, I was unfamiliar with this model of offroad military light utility vehicle, but by the end of the trip I would be a convert to the excellence of Soviet automotive engineering. It was like a Kalashnikov rifle: it was reliable, it never jammed no matter the conditions, and it had few moving parts you couldn’t fix with the most basic of tool kits. Moreover, it could handle any terrain.

For example, at one point on our journey, long after we had left the road behind and were rattling over raw desert, as the Mikes and I played car bingo with the species of wild animals we could spot—wild horses, camels: at one point we thought we saw a wolf; a sign of good luck here in the Gobi—we passed close to a herd of black-tailed gazelle. Without pausing a beat, Altan kicked it into gear and started chasing down the herd as Oktai leaned back and beckoned for his rifle. At top speed, the octogenarian kicked open his door and balanced his firearm in the crook. As the wind suddenly invaded the cabin, I exchanged glances of amazement and confusion with my fellow passengers. With a single shot, Oktai expertly wounded one of the fleeing antelopes, slowing it down enough to close in for a kill shot.

We all got out and marveled as Altan expertly fieldstripped the animal, discarding the offal and wrapping the liver, and strapped the carcass to our roof. That night, we made a gift of our trophy to a nomadic herder and his family, in exchange for their hospitality in allowing us to sleep in their ger. Called a yurt in Siberia, a ger is a felt and lattice-wall tent that provides a warm home out in the remote desert, or up in the windswept steppes. It can be broken down and rebuilt in less than an hour, after the seasonal move to fresh grazing land. The wealth of a Mongolian herder is reckoned not by the numbers in his bank account, but by the numbers in his herd. This patron offered me a pinch of snuff from an enormous bottle, and I learned that snuff bottles are a status symbol here: the larger it is, the richer the man.

That night we cooked the gazelle’s liver on a fire fueled by cattle dung, there being no trees in the desert. We sat around the hearth eating, smoking cigarettes, exchanging stories with our hosts, and drinking vodka in the traditional Mongolian manner: served hot, in a silver-lined wooden bowl, with yak butter and salt. As we were guests who had traveled a great distance to be here, most meals became a special event demanding round after round of Mongolian vodka.

This is how we spent each of our nights: driving through the desert and seeking a remote homestead upon whose hospitality we could rely for shelter, in exchange for whatever gifts we had brought along. Mike delighted in introducing the Mongolian children to that marvel of Western technology, the drink’n box [i.e.juicebox]. How their eyes lit up. He also had a walkman, and would let them listen to whatever German thrash metal band he had on cassette tape. The kids were less enthusiastic about that bit of cultural exchange than they were about the drink’n box.

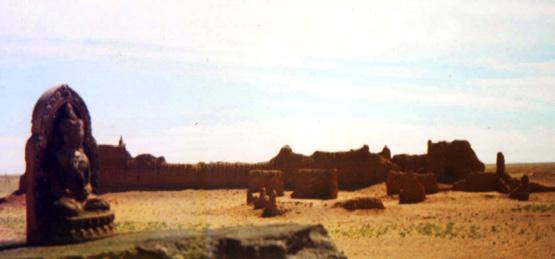

We saw much more, just by serendipity, driving around the Gobi than could ever have been planned by a tour guide in Ulaanbaatar. We walked in Zuunbayan with fossils crunching underfoot, where I imagined Roy Chapman Andrews must have found the dinosaur eggs that saved his bacon. We dined with the local magistrate, who tracked us down to make sure he wasn’t hallucinating, after seeing foreigners—foreigners! —a long distance off, watering camels at a remote desert well. We happened upon a group of tomb raiders excavating a half-buried Buddhist monastery, which had been destroyed in the 1930s in the Stalinist-inspired purges led by Choibalsan. They were looking for bricks for use in another building project, but along the way unearthed several Buddhist sculptures and other votive objects. We bought what we could carry.

The Chinese border was the end of the line for us, and here we were welcomed by a lonely military outpost guarding the frontier. After spending a night drinking more vodka and trading more tall tales with the soldiers, it was time to head back to Ulaanbaatar—a sad prospect. Even sadder was leaving Mongolia to continue my travels south through China.

I never saw the Mikes again, or Oktai and Altan for that matter. These were the days before the Internet, and you didn’t bring your social circles with you on your travels. We’ve gained much with the ubiquity of modern technology, but I think we’ve lost a certain degree of intrepidity as well. I have often thought about returning to Mongolia, but the country has changed so much, I think I would rather hang on to my memories as they are. I guess home is not the only place you can’t go again.