Paradoxes of Time Travel First Edition Ryan Wasserman

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/paradoxes-of-time-travel-first-edition-ryan-wasserman /

Visit to download the full and correct content document: https://ebookmass.com/product/paradoxes-of-time-travel-first-edition-ryan-wasserman /

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, Ox2 6dP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Ryan Wasserman 2018

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2018

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication data data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017943946

ISBN 978–0–19–879333–5

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

May you always be filled with wonder

One cannot help but wonder.

—H. G. Wells, The Time MachineIn the fall of 2005, I taught my very first introductory philosophy course. That course included a unit on freedom and determinism and I decided to conclude that section by spending a day on the grandfather paradox. That meeting ended up being so much fun that I added two extra days on the topic the next time I taught the class. Among other things, we discussed david Lewis’s definition of time travel, Robert Heinlein’s tales of causal loops, and doc Brown’s explanation of branching timelines from the Back to the Future movies. Student feedback on these topics was so positive that I eventually expanded the material into an entire course on time travel. The notes from that course went on to provide the basis of the book that you now hold.

This book retains many features of my original classroom lectures. I have tried my best to introduce all of the topics in an entertaining way, and to provide as much background material as is required. I have also included many of the examples and illustrations that have proven helpful in class. My hope is that the resulting work is accessible to all students of philosophy, and that teachers will find the text useful in their own philosophy courses. I would like to thank all of the students who have discussed these topics with me over the years—your feedback has helped me to improve this work in many different ways. I am especially grateful to three current students: Trevan Strean, who helped with the illustrations, dee Payton, who worked on the index, and Sean Nalty, who did proofreading. I would also like to thank Western Washington University for providing me with a teaching sabbatical and research support.

Another prominent feature of this book is its heavy use of examples from the science fiction genre. As will become clear, almost all of the philosophical issues raised by time travel have their roots in science fiction, and I have done my best to trace out the history of these ideas. I have been greatly aided in this task by Paul J. Nahin’s excellent book Time Machines: Time Travel in Physics, Metaphysics, and Science Fiction, and Michael Main’s comprehensive website <http://www.storypilot.com/>. Both of these works have provided me with endless examples and inspiration. I am also very grateful to the library staff at Western Washington University who helped me track down some truly obscure publications. My hope is that this research will help make this book of interest to science fiction fans, as well as philosophers.

Still, the main audience for this book will be professional philosophers—especially those with research interests in contemporary analytic metaphysics. Philosophers in this area will already be aware of some of the important issues raised by time travel— issues having to do with the nature of time, freedom, causation, and identity. However,

philosophers in this area also know that, until this point, there has been no comprehensive study of these topics. That is the primary goal of this book—to survey, systematize, and expand upon the philosophical literature on time travel. I would like to thank all of the philosophers who have helped me in this task by providing comments on earlier drafts of this work. This includes Thomas Hall, d an Howard-Snyder, Frances Howard-Snyder, Hud Hudson, d avid Manley, Ned Markosian, Gerald Marsch, Tim Maudlin, Jeff Russell, Michelle Saint, Neal Tognazzini, James Van Cleve, and two anonymous readers for Oxford University Press. I would also like to thank Andreas Riemann, who proofread the material on special relativity, and Jonathan Bennett and Steffi Lewis, who provided me with unpublished materials relating to david Lewis’s work on time travel. Finally, I gratefully acknowledge Springer, Wiley, Oxford University Press, Cambridge University Press, and Hud Hudson for giving me permission to include portions of the following works in this book: “Van Inwagen on Time Travel and Changing the Past,” in de an Zimmerman, ed., Oxford Studies in Metaphysics, Volume 5 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010); “Personal Identity, Indeterminacy, and Obligation,” in Georg Gasser and Matthias Stefan, eds., Personal Identity: Simple or Complex? (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013); “Theories of Persistence,” Philosophical Studies, 173 (2016): 243–50; and “Vagueness and the Laws of Metaphysics,” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 95 (2017): 66–89. Lastly, and most importantly, I would like to thank my family—Christine, Ben, and Zoë. You have been a constant source of encouragement, support, and perspective throughout this process. I couldn’t have done it without you.

“It’s against reason,” said Filby.

“What reason?” said the Time Traveller.

—H. G. Wells, The Time MachineIn the spring of 1927, Hugo Gernsback published a version of The Time Machine in his fledgling science fiction magazine, Amazing Stories 1 The story was an immediate hit with readers, and generated a steady stream of letters.2 Some of these responses were filled with praise, while others took a more critical tone. Reader Jackson Beck, for example, complained that there was “something amiss” in The Time Machine, for “How could one travel to the future in a machine when the beings of the future have not yet materialized?” (Gernsback 1927: 412). Another reader, identified as “T.J.D.” from Cleveland, wrote in with a much longer list of complaints:

How about this “Time Machine”? Let’s suppose our inventor starts a “Time voyage” backward to about a.d. 1900, at which time he was a schoolboy . . . [Suppose] he stops the machine, gets out and attends the graduating exercises of the class of 1900 of which he was a member. Will there be another “he” on the stage[?] Of course, because he did graduate in 1900. Interesting thought. Should he go up and shake hands with this “alter ego”[?] Will there be two physically distinct but characteristically identical persons? Alas! No! He can’t go up and shake hands with himself because you see this voyage back through time only duplicates actual past conditions and in 1900 this stranger “other he” did not appear suddenly in quaint ultra-new fashions and congratulate the graduate. How could they both be wearing the same watch they got from Aunt Lucy on their seventh birthday, the same watch in two different places at the same time[?] Boy! Page Einstein! . . . [Also] The journey backward must cease on the year of his birth. If he could pass that year it would certainly be an effect going before a cause . . .

1 Launched in 1926, Amazing Stories is widely recognized as the first science fiction magazine. Gernsback, who founded the publication, is often cited as one of the fathers of science fiction.

2 The Time Machine deserves credit for sparking the popular fascination with time travel, but it was not the first publication on the topic (contra Calvert 2002: 2, Gleick 2016: 5, and many others). Published in 1895, Wells’s novella was preceded by at least twenty other time travel stories, including Samuel Madden’s Memoirs of the Twentieth Century (1733), Edward Page Mitchell’s “The Clock that Went Backwards” (1881), and Wells’s own 1888 story “The Chronic Argonauts” (reprinted in Wells 2009). Indeed, the concept of time travel arguably goes back to ancient tales like the Hindu story of King Kakudmi, the Chinese legend of Ranka, and the Japanese tale of Urashima Taro. For an excellent overview of the pre-Wellsian literature, see Main (2008).

[Finally] Suppose for instance in the graduating exercise above, the inventor should decide to shoot his former self, the graduate[;] he couldn’t do it because if he did the inventor would have been cut off before he began to invent and he would never have gotten around to making the voyage, thus rendering it impossible for him to be there taking a shot at himself, so that as a matter of fact he would be there and could take a shot—help, help, I’m on a vicious circle merry-go-round! (1927: 410)

Gernsback would go on to publish many more letters on the topic of time travel,3 but these first few examples are particularly noteworthy since they represent some of the very first publications on the paradoxes of time travel.4 These paradoxes would prove to be a favorite topic in early science fiction forums,5 and would go on to be the source of much debate in physics, philosophy, and popular culture.6 Among other things, it has been argued that the paradoxes of time travel have important implications for how we think about time, tense, ontology, causation, chance, counterfactuals, laws of nature, explanation, freedom, fatalism, moral responsibility, persistence, change, and mereology. These are just a few of the topics to be addressed in this book.

In this chapter, we will clarify the concept of time travel (sections 1 and 2), introduce the main question of the book (section 3), and preview the paradoxes to come (section 4).

Time travel obviously involves traveling to other times. But what exactly does this mean? Talk of “travel” suggests a kind of movement, but movement is a matter of being

3 The early relationship between science fiction writers and readers was a symbiotic one—new stories would generate objections from readers and those objections would often lead to new ideas for stories. One of the best examples of this is Mort Weisinger’s “Thompson’s Time Traveling Theory” (1944) in which a science fiction author, frustrated by the skeptical response to his time travel stories, builds a working time machine in order to prove its possibility to his readers. (As the author tells his editor: “I’m going into the past and kill my grandfather! Then we’ll see just how hot you and your readers are!”)

4 The very first discussion of a time travel paradox I am aware of is in Enrique Gaspar’s The Time Ship: A Chrononautical Journey (originally published in 1887). In Gaspar’s story, two “time trekkers” set out for the past and, along the way, discuss the possible implications of their journey:

“Since we are bound for yesterday and will arrive in the past bearing the experience of History, wouldn’t we be able to change the human condition by avoiding the catastrophes that have caused so much turmoil in society?”

. . . “Not in in the slightest. We may be present to witness facts consummated in preceding centuries, but we may never undo their existence. To put it more clearly: we may unwrap time, but we don’t know how to nullify it. If today is a consequence of yesterday and we are living examples of the present, we cannot, unless we destroy ourselves, wipe out a cause of which we are its actual effects.” (1887/2012: 59)

This, of course, is a variation on the famous grandfather paradox, which we will discuss in more detail below.

Credit for the first academic discussion of time travel should probably go to Walter B. Pitkin for his paper “Time and Pure Activity” (1914). Among other things, Pitkin discusses a version of the time discrepancy paradox (section 1 of this chapter) and the double-occupancy problem (Chapter 2, section 2).

5 The first such forum was the “Discussions” section of Amazing Stories. That magazine went bankrupt in 1929, but the discussion continued in Gernsback’s next publication—Science Wonder Stories—in the “Reader Speaks” section.

6 For an excellent overview of these debates, see Nahin (1999).

in different places at different times. So what could it mean to move about in time? One might think that movement in time involves being in different times at different times, but this seems like nonsense—what could it mean to say that something exists “in different times at different times”?7

Consider a specific example. Suppose a time traveler enters her time machine, turns some dials, and then, a minute later, arrives one hundred years in the past. This seems to involve a direct contradiction, since it seems to involve two events—the time traveler’s departure and arrival—being separated by unequal amounts of time (namely, one minute and one hundred years).

The same worry also arises in cases of future time travel. Here is how the science fiction author Milton Kaletsky puts the problem:

As for traveling into the future, suppose the traveler to journey at some rate such as one year per hour, i.e., he travels for one hour . . . and finds himself one year in the future . . . This is sheer nonsense. A year cannot elapse in one hour for the simple reason that an hour is defined as less than a year. A fraction and the whole cannot be equal; a year and an hour cannot elapse in the same interval of time because they are different intervals of time, by definition . . . Hence . . . time traveling into the future is impossible. (1935: 173)8

What these examples seem to show is that time travel (in either direction) requires a discrepancy between time and time. Since this is contradictory, the very concept of time travel is incoherent. This is what Dennis Holt (1981) calls the time discrepancy paradox. 9

The time discrepancy paradox has led some philosophers to dismiss the possibility of time travel altogether.10 But those philosophers are in the minority. The more popular response, due to David Lewis, is to draw a distinction between two different kinds of time:

How can it be that the same two events, [the time traveler’s] departure and his arrival, are separated by two unequal amounts of time? . . . I reply by distinguishing time itself, external time

7 A similar line of questioning is pressed by Smart (1963).

8 Kaletsky (1911–1988) was an early science fiction author who published under the names ‘Milton Kaletzky’, ‘Dane Milton’, and, my personal favorite, ‘Omnia’. He was also an active figure in the early science fiction forums, publishing letters in Wonder Stories, Amazing Stories, and Astonishing Stories

9 One of the most famous examples of the time discrepancy paradox can be found in the epilogue of The Time Machine, in which the book’s narrator speculates about the “current” whereabouts of the Time Traveller: It may be that he swept back into the past, and fell among the blood-drinking, hairy savages of the Age of Unpolished Stone; into the abysses of the Cretaceous Sea; or among the grotesque saurians, the huge reptilian brutes of the Jurassic times. He may even now—if I may use the phrase—be wandering on some plesiosaurus-haunted Oolitic coral reef, or beside the lonely saline lakes of the Triassic Age. (Wells 2009: 71)

The tension in this passage comes from the suggestion that the Time Traveller is now doing something in the past. Other famous examples of the time discrepancy paradox can be found in Doctor Who (see the exchange between the Doctor and Sally Sparrow in the episode “Blink”), Lost (see the exchange between Miles and Hurley in the episode “Whatever Happened, Happened”), and Back to the Future (see the exchange between Doc and Marty when Marty first arrives in the past).

10 See, for example, Pitkin (1914: 523), Christensen (1976), Holt (1981), and Grey (1999: 57–8). For other statements of this worry, see Dretske (1962: 97–8), Harrison (1971: 3), Niven (1971), Smart (1963: 239), and Williams (1951: 463).

as I shall also call it, from the personal time of a particular time traveler: roughly, that which is measured by his wristwatch. His journey takes an hour of his personal time, let us say; his wristwatch reads an hour later at arrival than at departure. But the arrival is more than an hour after the departure in external time, if he travels toward the future; or the arrival is before the departure in external time (or less than an hour after), if he travels toward the past. (1976: 146)11

As Lewis notes, the distinction between personal time and external time seems to provide a simple solution to the time discrepancy paradox. The departure and arrival are separated by one amount of personal time and a different amount of external time. This is a discrepancy, but not a contradiction, since personal time and external time are two different things.

To further illustrate the idea, imagine a case in which a time traveler—Doctor Who, let’s say—is born at t3, enters the TARDIS time machine at t6, and travels back to t1. (See Figure 1.1.)

1.1

According to the Objective World Historian, the first event in this series is the Doctor’s appearance at t1. After that comes the birth, the stages of childhood, the experiences of adulthood, and, finally, the trip back in time. This is the ordering of those events, according to external time. According to the Doctor, these events take place in a different order—the birth, for example, comes before the appearance in the past. This is the ordering of those events—the very same events—according to his personal time. This last point deserves special emphasis. Personal time, for Lewis, is not a separate dimension filled with its own collection of events. Rather, it is an alternative assignment of coordinates to ordinary temporal events—an assignment that corresponds, in some way, to the experiences of a particular individual.

11 Lewis also mentions a second solution to the time discrepancy paradox that involves two-dimensional time. We discuss this model in Chapter 3 of this book.

Note that this correspondence does not simply concern the ordering of those events—personal time also provides a metric that allows for comparisons of temporal distance. For example, the assignment of coordinates to the Doctor’s stages should reflect the fact that the distance between his t6-stage and his t1-stage is much less than the distance between his t3-stage and his t5-stage. This aspect of personal time also allows for an additional kind of discrepancy with external time. For example, the Doctor’s departure and arrival might be separated by forty years of external time, but only a few seconds of personal time.

Note also that personal time does not need to be limited to events going on inside the time traveler’s mind or body. As Lewis notes, we can also “extend the assignment of personal time outwards from the time traveler’s stages to the surrounding events” (1976: 147). Suppose, for example, that the Doctor’s companion, Leela, is sleeping when the TARDIS takes off at t6 and that she awakens when they arrive at t1. In that case, the Doctor might very well count the awakening as coming after the nap since (i) the nap is simultaneous with his t6-stage, (ii) the awakening is simultaneous with his t1-stage, and (iii) his t1-stage comes after his t6-stage according to his personal time.

However, this kind of “extension” leads to a potential problem.12 Consider, for example, the inventor that T.J.D. mentions in his letter to Amazing Stories. That inventor goes back in time to visit his graduating ceremony—a ceremony that he has already experienced once as a child. Since he is about to experience that event again, it will have to make a second appearance in his personal history. But that means that a single event—the graduation ceremony—will be both before and after itself according to his personal time. So, it seems as if we are still stuck with a kind of temporal discrepancy.

Fortunately, this kind of discrepancy does not seem all that paradoxical. To say that this event occurs after itself according to the inventor’s “extended” personal time is just to say that (i) it is simultaneous with one stage of the inventor, (ii) it is simultaneous with another stage of the inventor, and (iii) the second stage of the inventor comes after the first, according to his personal time. And all of those conditions are met, owing to the unusual fact that the inventor has two stages present at the same point in external time. What would be strange is if time—real time—allowed for a single event to occur both before and after itself. This would be strange because we normally think of external time as being linear. But if we want to allow for self-visitation (of the sort described by T.J.D.) and we want to “extend” personal time (in the way suggested by Lewis), we will have to have a much more open view about its structure. Unlike external time, personal time can run in reverse, repeat itself, and generally get tied up into all sorts of knots. This might be part of what Doctor Who had in mind when he described time as a “big ball of wibbly-wobbly, timey-wimey stuff” (Doctor Who, Season 29, Episode 10).

12 Thanks to Andrew Law for helping me get clearer on this point.

The distinction between personal time and external time allows us to make sense of temporal discrepancies, but it also suggests a natural account of time travel. For someone to travel in time is for there to be a discrepancy between external time and that individual’s personal time. That is, time travel occurs only if, and in that case because, there is a discrepancy between external and personal time. This is the standard definition of time travel in the philosophical literature.13

The standard definition of time travel is plausible, but the accompanying definition of personal time is not. Lewis initially defines personal time in terms of “wristwatch” time—that is, time as measured on a watch. The problem is that, on this characterization, a discrepancy between personal time and external time is neither necessary nor sufficient for time travel—it is not necessary since people can always travel without watches, and it is not sufficient since watches can always malfunction.14

One natural response to these worries is to move to an idealized version of the wristwatch definition. For example, one might say that personal time is what would be measured if the relevant person were wearing an accurate watch. That would avoid both of the problems just raised, but it would also create problems of its own. For one thing, an “accurate” clock is presumably defined as a clock that would correctly track personal time.15 But, in that case, the proposed definition would be immediately circular (personal time is what an accurate watch would measure and an accurate watch is one that would correctly measure personal time).16

Lewis’s response is to replace his original definition of personal time with the following “functional” alternative:

[P]ersonal time is that which occupies a certain role in the pattern of events that comprise the time traveler’s life. If you take the stages of a common person, they manifest certain regularities with respect to external time Memories accumulate. Food digests. Hair grows. Wristwatch hands move. If you take the stages of a time traveler instead, they do not manifest the common regularities with respect to external time. But there is one way to assign coordinates to the time traveler’s stages, and one way only (apart from the arbitrary choice of a zero point), so that the regularities that hold with respect to this assignment match those that commonly hold with respect to external time The assignment of coordinates that yields this match is the time

13 Versions of the standard definition are endorsed by Arntzenius (2006), Decker (2013: 181), Devlin (2001: 33–4), Dowe (2000: 441–2), Eaton (2010: 76–7), Everett and Roman (2012: 12), Fulmer (1983: 31–2), Horwich (1987: 114), Hunter (2004), Keller and Nelson (2001: 334), Kutach (2013: 301–2), Ney (2000: 312–13), Perszyk and Smith (2001), Richmond (2008: 39), Sider (2001), and others. The main alternative in the literature is to define time travel in terms of closed timeline curves in general relativity—see, for example, Malament (1984: 91).

14 As Lewis puts it, “my own wristwatch often disagrees with external time, yet I am no time traveler” (1976: 146).

15 An alternative is to characterize both clock accuracy and personal time in terms of the invariant interval of special relativity. We will return to this idea in Chapter 2, section 5.

16 Also, counterfactual definitions never work. Suppose, for example, that the Doctor is traveling in the TARDIS and that he has developed an unusual phobia of time traveling while wearing watches. So, if he were wearing a watch at this time, he would immediately stop the TARDIS. In that case, there would no longer be any discrepancy between external time and personal time (as currently defined). So, the definition would incorrectly entail that the Doctor is not currently time traveling.

traveler’s personal time. It isn’t really time, but it plays the role in his life that time plays in the life of a common person. It’s enough like time so that we can—with due caution—transplant our temporal vocabulary to it in discussing his affairs. (1976: 146)

So, the revised proposal is that personal time is an assignment of coordinates to person-stages that preserves the regularities we ordinarily see in people.17 For example, in Figure 1.1, the Doctor’s t5-stage should be assigned a later coordinate than the t4-stage since older-looking stages typically come after younger-looking stages. Or suppose that the Doctor has just finished a snack when he enters the time machine at t6. In that case, he will still be digesting corresponding bits of food when he emerges from the time machine at t1. This is part of the explanation for why the t1-stage comes after the t6-stage in his personal time—digesting regularly comes after eating in the life of a normal human being. And this reversal of ordering is part of what makes the Doctor a time traveler.

Unfortunately, there is an obvious problem with the revised definition: It only applies to persons! In order to provide an adequate definition of time travel, we have to be able to generalize the notion of “personal time” so that it applies to plants, animals, and other kinds of objects. However, this generalization turns out to be difficult. To make the problem vivid, imagine a world filled with nothing but unchanging elementary particles—electrons, let’s say. Now imagine picking out one of those electrons, and assigning coordinates to its stages in accordance with external time (Figure 1.2).

Here is the problem. If electrons do not undergo any intrinsic change, then there will be many other ways of assigning coordinates to the electron’s stages so that “the regularities that hold with respect to those assignments match those that commonly hold with respect to external time.” The most obvious option is to simply reverse the ordering indicated in Figure 1.2, so that the t1-stage is labeled ‘6’, the t2-stage is labeled ‘5’, and so on. If we track the electron’s career according to this assignment, we will still see the same patterns that are observed with other electrons—for example, the electron will still move continuously, and its charge will still remain constant—but this would obviously not be enough to make the electron a time traveler.

In order to broaden our account of personal time, we must move beyond the functional definition. Ideally, what we would like to find is a perfectly general relation that

17 We will say more about “person-stages” in Chapters 2 and 6; for now, we can simply think of stages as parts of a person’s life.

could provide an order and metric for any object, whether it be a person, a particle, or a time machine.

The most obvious candidate for this job is causation, since it is generally agreed that identity over time requires causal dependence.18 For example, it is often said that a person at one time can only be identical to a person at another time if there is an appropriate causal connection between the relevant mental states. What counts as an “appropriate” causal connection is a difficult question, as is the question of which states, exactly, must stand in that relation.19 We will not enter into those debates here. Rather, we will assume that there are answers to these questions and that the specified causal relation will order the stages of a given object in the way required. We will then say that an object’s personal time is the assignment of coordinates to its stages that matches the coordinates given by the underlying causal relation. In the case of non-time-travelers, this assignment will correspond to the one given by external time; in the case of time travelers, it will not. Time travel thus amounts to a discrepancy between time—real time—and the kind of causal relations that make for identity over time.

Now that we have said what time travel is, we should also say a few words about what it is not.

First, traveling across time zones is obviously not an example of time travel.20 If someone flies from New York to Los Angeles, she may set her watch back three hours, but she does not travel back three hours. Rather, she simply travels to a city that assigns a different number to the current moment (the number dictated by Pacific Standard Time). To think that one could travel through time by changing the numbers on a watch would be like thinking that one could speed up a car by renumbering its speedometer.21

18 See, for example, Armstrong (1980), Lewis (1983), and Perry (1976: 69–70).

19 For an introduction to these issues, see Zimmerman (1997).

20 This seeming truism is sometimes disputed—see, for example, Hunter (2016: 14). For criticism of this idea, see Dowden (2009: 48–9), Nahin (2011: 14–15), and Smith (2013: section 1). A related mistake is the idea that one could travel through time by circling the earth faster than the sun. Believe it or not, this suggestion actually forms the basis of the H. S. MacKaye story The Panchronicon. As one character in the story explains it:

What is it makes the days go by—ain’t it the daily revolution of the sun? . . . [So] Ef a feller was to whirl clear round the world an’ cut all the meridians in the same direction as the sun, an’ he made the whole trip around jest as quick as the sun did—time wouldn’t change a mite fer him [And] ef a feller’ll jest take a grip on the North Pole an’ go whirlin’ round it, he’ll be cuttin’ meridians as fast as a hay-chopper? Won’t he see the sun getting’ left behind an’ whirlin’ the other way from what it does in nature? An’ ef the sun goes the other way round, ain’t it sure to unwind all the time thet it’s ben a-rollin’ up? (1904: 14–16)

This theory goes wrong at the very first step in assuming that the revolution of the sun is what makes time pass. But this does not stop the characters in the story from successfully using this method to travel back in time.

21 Fans of Spinal Tap will recognize this as instance of “the Nigel Tufnel fallacy.”

Second, remembering past events is clearly not enough for time travel. Some psychologists do refer to memory as “mental time travel,”22 but this kind of talk is metaphorical. Memory only “transports” us into the past in the way that Star Wars transports us to a galaxy far, far away.

Similarly, having visions of the past or future is not enough for time travel. Consider, for example, the case of Ebenezer Scrooge. Some have cited Scrooge’s encounter with the Ghost of Christmas Past as an early example of backward time travel.23 Others demur.24 Who is correct? That depends on the details of the case. If Scrooge’s thoughts and sensations are literally taking place in the past, then there would indeed be a discrepancy between his personal time and external time. If, on the other hand, Scrooge is simply having a vision, then the relevant experiences may be of the past, but they are not taking place in the past. In that case, Scrooge would not count as a genuine time traveler.25

Fourth, it might seem obvious that going to sleep is not enough to make one a time traveler.26 However, some have suggested that this depends upon the length of the nap.27 Consider, for example, the case of Rip Van Winkle, who is said to have fallen asleep for twenty years. If Van Winkle is completely unconscious while he sleeps, his experiences will be internally indiscernible from those of a time traveler who disappears from one time and reappears twenty years later. From both of their perspectives, the “next” thing that happens is not really the next thing that happens. So, one might think that both cases involve discrepancies between personal and external time. However, there is at least one important difference between Van Winkle and the “jumpy” time traveler—Van Winkle’s body is present throughout the entire period, and it is natural to think that the causal processes going on in his body are what preserves his identity during that time (i.e., they help explain why the person who wakes up after the slumber is the same person as the one who went to sleep). Moreover, these processes seem to be going at something like a normal rate since Van Winkle’s body shows the typical signs of aging when he awakens (for example, in the story we are told

22 See, for example, Murray (2003), Stocker (2012), and Suddendorf and Corballis (1997). Clegg (2011: 1–2) seems to suggest that memory involves genuine travel to the past.

23 See, for example, Jones and Ormrod (2015: 14), Rickman (2004: 370), and Kaku (2009: 218).

24 See, for example, Bigelow (2001: 78), Main (2008), and Nahin (1999: 9).

25 There is arguably evidence for both of these readings in the text. On one hand, Scrooge and the Ghost certainly seem to interact with past objects—they are said to be “walking along the road” and Scrooge is “conscious of a thousand odours floating on the air” (Dickens 1843/1908: 38). On the other hand, the Ghost says that the objects of Scrooge’s perception “are but shadows of the things that have been,” suggesting that Scrooge is not really experiencing the past (Dickens 1843/1908: 39). On the other hand, we are also told that (old) Scrooge gets a pimple when he revisits the days of his youth. So it’s not exactly clear what’s going on.

26 Smith (2013: section 1).

27 See, for example, Karcher (1985: 32), Mellor (1998: 124), Booker and Thomas (2009: 15), Hunter (2016: 8), and Gleick (2016: 30–1). Kutach (2013: 302) says that whether or not Rip Van Winkle counts as a time traveler is a matter of interpretation.

that his joints are sore and his beard has grown).28 If all of this is correct, then there doesn’t seem to be any mismatch between external time and the causal relations that make for identity in this case.29, 30

But now consider an example of suspended animation. In the Captain America story, Steve Rogers crashes an aircraft in the Arctic during the closing days of World War II. Rogers is then encased in ice and preserved in a state of suspended animation for nearly seventy years.31 When he is thawed out, Rogers shows no sign of aging, and soon returns to normal superhero activity. Here is the problem. Unlike Rip Van Winkle, all of Captain America’s bodily processes are stopped while he sleeps. So, for example, if Rogers had a light snack before his final mission, that food will not digest at all during the intervening years. But then (to quote Lewis), there is only “one way to assign coordinates to [Captain America’s stages] . . . so that the regularities that hold with respect to this assignment match those that commonly hold with respect to external time.” This assignment will require us to give the very same coordinate to each stage during the period of suspended animation, and to resume the standard numbering once Rogers awakens. This is the only assignment on which his bodily processes will “match” those that commonly hold with respect to external time. However, this assignment will obviously give us a discrepancy between personal time and external time. For example, the process of digesting his last meal will take approximately seven hours of Rogers’s personal time and seventy years of external time. On Lewis’s definition, that kind of discrepancy is all it takes to make someone a time traveler.32

28 Of course, there is something unusual about these causal processes, since they are being sustained in the absence of food and water. But the important point is that the causal order of the body’s stages matches the one given by external time.

29 Here it may be helpful to compare the case of Rip Van Winkle to the case of a watch that is taken completely apart and then reassembled. Presumably, there is no watch when all the pieces have been taken apart, so there is a sense in which this object “jumps” forward in time—it exists for a while, then it goes out of existence, and then it comes back again. However, the watch at the end of this process is only identical to the watch at the beginning because of the continued existence of the parts. Moreover, there are no causal abnormalities in the lives of the parts, so there is no discrepancy in the underlying identity-making relations. Depending on one’s view of persons, one might think that there is no person present while Van Winkle’s body is hibernating. Still, the basic parts of the body are all there, and those parts—like the watch’s parts—do not exhibit the kind of causal abnormalities that are characteristic of time travel.

30 For a very different explanation of why Rip Van Winkle is not a time traveler, see Read (2012: 139–40).

31 This is the movie version of the story. In the comics, Rogers is frozen for less than twenty years.

32 A similar point can be made using a different comic character. Consider the case of the Flash, whose superpower is to move at incredibly high speeds. While it is not entirely clear in the comics, we can suppose that all of the Flash’s biological processes speed up when he uses his power—from our perspective, his hair grows faster, his food digests quicker, and his thoughts occur more rapidly. Of course, we can also imagine that, from the Flash’s perspective, things are reversed—as he sees it, his mental and physical processes continue as normal, while everyone around him slows down. This kind of case poses a potential problem for Lewis’s definition, since the Flash is not typically portrayed as a time traveler. (Actually, the Flash is portrayed as a time traveler, but only when he uses his powers in a special way—see, for example, his use of the “Cosmic Treadmill” in The Flash no. 125.)

Another random document with no related content on Scribd:

This ebook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this ebook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this eBook.

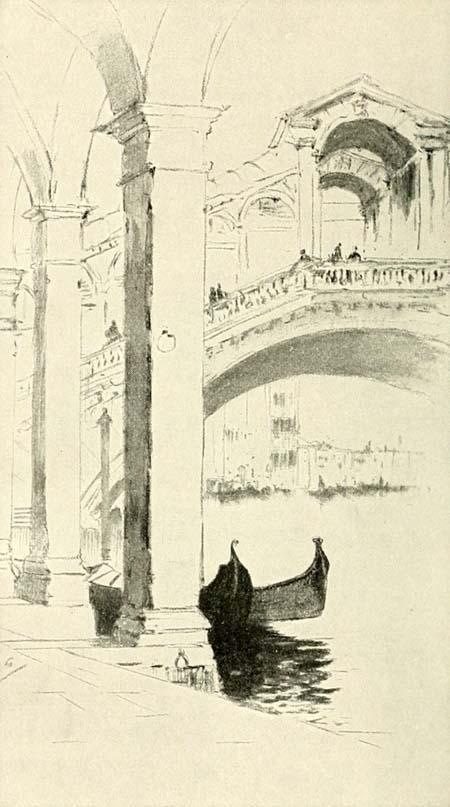

Title: Gondola days

Author: Francis Hopkinson Smith

Release date: August 31, 2023 [eBook #71528]

Language: English

Original publication: Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1897

Credits: D A Alexander, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive) *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK GONDOLA DAYS ***

TOM GROGAN. Illustrated. 12mo, gilt top, $1.50.

A GENTLEMAN

VAGABOND, AND SOME OTHERS. 16mo, $1.25.

COLONEL CARTER OF CARTERSVILLE. With 20 illustrations by the author and E. W. Kemble. 16mo, $1.25.

A DAY AT LAGUERRE’S, AND OTHER DAYS. Printed in a new style. 16mo, $1.25.

A WHITE UMBRELLA IN MEXICO. Illustrated by the author. 16mo, gilt top, $1.50.

GONDOLA DAYS. Illustrated, 12mo, $1.50.

WELL-WORN ROADS OF SPAIN, HOLLAND, AND ITALY, traveled by a Painter in search of the

Picturesque. With 16 fullpage phototype reproductions of watercolor drawings, and text by F. H�������� S����, profusely illustrated with pen-and-ink sketches. A Holiday volume. Folio, gilt top, $15.00.

THE SAME. Popular Edition. Including some of the illustrations of the above. 16mo, gilt top, $1.25.

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN & CO.

B����� ��� N�� Y���.

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN AND COMPANY THE RIVERSIDE PRESS CAMBRIDGE 1897

COPYRIGHT, 1897, BY F. HOPKINSON SMITH ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

THE text of this volume is the same as that of “Venice of To-Day,” recently published by the Henry T. Thomas Company, of New York, as a subscription book, in large quarto and folio form, with over two hundred illustrations by the Author, in color and in black and white.

I HAVE made no attempt in these pages to review the splendors of the past, or to probe the many vital questions which concern the present, of this wondrous City of the Sea. Neither have I ventured to discuss the marvels of her architecture, the wealth of her literature and art, nor the growing importance of her commerce and manufactures.

I have contented myself rather with the Venice that you see in the sunlight of a summer’s day—the Venice that bewilders with her glory when you land at her water-gate; that delights with her color when you idle along the Riva; that intoxicates with her music as you lie in your gondola adrift on the bosom of some breathless lagoon—the Venice of mould-stained palace, quaint caffè and arching bridge; of fragrant incense, cool, dim-lighted church, and noiseless priest; of strong-armed men and graceful women—the Venice of light and life, of sea and sky and melody.

No pen alone can tell this story. The pencil and the palette must lend their touch when one would picture the wide sweep of her piazzas, the abandon of her gardens, the charm of her canal and street life, the happy indolence of her people, the faded sumptuousness of her homes.

If I have given to Venice a prominent place among the cities of the earth it is because in this selfish, materialistic, money-getting age, it is a joy to live, if only for a day, where a song is more prized than a soldo; where the poorest pauper laughingly shares his scanty crust; where to be kind to a child is a habit, to be neglectful of old age a shame; a city the relics of whose past are the lessons of our future; whose every canvas, stone, and bronze bear witness to a grandeur, luxury, and taste that took a thousand years of energy to perfect, and will take a thousand years of neglect to destroy.

To every one of my art-loving countrymen this city should be a Mecca; to know her thoroughly is to know all the beauty and romance of five centuries.

F. H. S.

OU really begin to arrive in Venice when you leave Milan. Your train is hardly out of the station before you have conjured up all the visions and traditions of your childhood: great rows of white palaces running sheer into the water; picture-book galleys reflected upside down in red lagoons; domes and minarets, kiosks, towers, and steeples, queer-arched temples, and the like.

As you speed on in the dusty train, your memory-fed imagination takes new flights. You expect gold-encrusted barges, hung with Persian carpets, rowed by slaves double-banked, and trailing rare brocades in a sea of China-blue, to meet you at the water landing. By the time you reach Verona your mental panorama makes another turn. The very name suggests the gay lover of the bal masque, the poisoned vial, and the calcium moonlight illuminating the wooden tomb of the stage-set graveyard. You instinctively look around for the fair Juliet and her nurse. There are half a dozen as pretty Veronese, attended by their watchful duennas, going down by train to the City by the Sea; but they do not satisfy you. You want one in a tight-fitting white satin gown with flowing train, a diamond-studded girdle, and an ostrich-plume fan. The nurse, too, must be stouter, and have a highkeyed voice; be bent a little in the back, and shake her finger in a threatening way, as in the old mezzotints you have seen of Mrs. Siddons or Peg Woffington. This pair of Dulcineas on the seat in front, in silk dusters, with a lunch-basket and a box of sweets, are too modern and commonplace for you, and will not do.

When you roll into Padua, and neither doge nor inquisitor in ermine or black gown boards the train, you grow restless. A deadening suspicion enters your mind. What if, after all, there should be no Venice? Just as there is no Robinson Crusoe nor man Friday; no stockade, nor little garden; no Shahrazad telling her stories far into

the Arabian night; no Santa Claus with reindeer; no Rip Van Winkle haunted by queer little gnomes in fur caps. As this suspicion deepens, the blood clogs in your veins, and a thousand shivers go down your spine. You begin to fear that all these traditions of your childhood, all these dreams and fancies, are like the thousand and one other lies that have been told to and believed by you since the days when you spelled out words in two syllables.

Upon leaving Mestre—the last station—you smell the salt air of the Adriatic through the open car window. Instantly your hopes revive. Craning your head far out, you catch a glimpse of a long, low, monotonous bridge, and away off in the purple haze, the dreary outline of a distant city. You sink back into your seat exhausted. Yes, you knew it all the time. The whole thing is a swindle and a sham!

“All out for Venice,” says the guard, in French.

Half a dozen porters—well-dressed, civil-spoken porters, flat-capped and numbered—seize your traps and help you from the train. You look up. It is like all the rest of the depots since you left Paris—high, dingy, besmoked, beraftered, beglazed, and be——! No, you are past all that. You are not angry. You are merely broken-hearted. Another idol of your childhood shattered; another coin that your soul coveted, nailed to the wall of your experience—a counterfeit!

“This door to the gondolas,” says the porter. He is very polite. If he were less so, you might make excuse to brain him on the way out.

The depot ends in a narrow passageway. It is the same old fraud— custom-house officers on each side; man with a punch mutilating tickets; rows of other men with brass medals on their arms the size of apothecaries’ scales—hackmen, you think, with their whips outside—licensed runners for the gondoliers, you learn afterward. They are all shouting—all intent on carrying you off bodily. The vulgar modern horde!

Soon you begin to breathe more easily. There is another door ahead, framing a bit of blue sky. “At least, the sun shines here,” you say to yourself. “Thank God for that much!”

“This way, Signore.”

One step, and you stand in the light. Now look! Below, at your very feet, a great flight of marble steps drops down to the water’s edge. Crowding these steps is a throng of gondoliers, porters, women with fans and gay-colored gowns, priests, fruit-sellers, water-carriers, and peddlers. At the edge, and away over as far as the beautiful marble church, a flock of gondolas like black swans curve in and out. Beyond stretches the double line of church and palace, bordering the glistening highway. Over all is the soft golden haze, the shimmer, the translucence of the Venetian summer sunset.

With your head in a whirl,—so intense is the surprise, so foreign to your traditions and dreams the actuality,—you throw yourself on the yielding cushions of a waiting gondola. A turn of the gondolier’s wrist, and you dart into a narrow canal. Now the smells greet you— damp, cool, low-tide smells. The palaces and warehouses shut out the sky. On you go—under low bridges of marble, fringed with people leaning listlessly over; around sharp corners, their red and yellow bricks worn into ridges by thousands of rounding boats; past open plazas crowded with the teeming life of the city. The shadows deepen; the waters glint like flakes of broken gold-leaf. High up in an opening you catch a glimpse of a tower, rose-pink in the fading light; it is the Campanile. Farther on, you slip beneath an arch caught between two palaces and held in mid-air. You look up, shuddering as you trace the outlines of the fatal Bridge of Sighs. For a moment all is dark. Then you glide into a sea of opal, of amethyst and sapphire.

The gondola stops near a small flight of stone steps protected by huge poles striped with blue and red. Other gondolas are debarking. A stout porter in gold lace steadies yours as you alight.

“Monsieur’s rooms are quite ready. They are over the garden; the one with the balcony overhanging the water.”

The hall is full of people (it is the Britannia, the best hotel in Venice), grouped about the tables, chatting or reading, sipping coffee or eating ices. Beyond, from an open door, comes the perfume of flowers. You pass out, cross a garden, cool and fresh in the darkening shadows, and enter a small room opening on a staircase.