The Team

Ming Kit Wong

Justas Petrauskas

Zoe Lambert

Miyo Peck-Suzuki

Danilo Angulo-Molina

Marta Kakol

Angelo M’BA

Julia Hoffmann

Turner Ruggi

Eli Harris-Trent

Justin Daniels

Joe Ward

Hazal Bulut

Ciara Rushton

Lindsey A. Williams

Jason Chau

Andrew Wang

Henry Ferrabee

Michael Wakin

Isabella Turilli

Jay Howard

Andrew Wang

Dowon Jung

Isabel Nguyen

Brian Wong

Michael Shao

Nicholas Leah

Chang Che

Simon Hunt

Acknowledgments

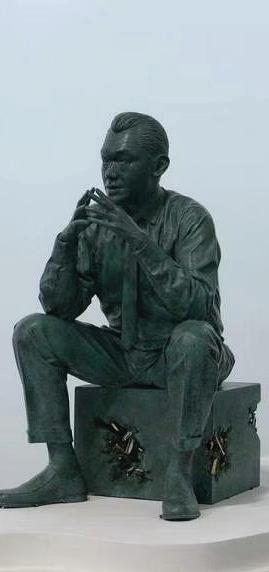

Artwork on cover is graciously provided by Dowon Jung (dowonjung. com).

A sincere thank you to everyone who made submissions to this issue.

All articles that appear in this issue will also be made available online in due course.

Much ink has been spilled over the precise meaning of utopia. Indeed, Gregory Claeys and Lyman Tower Sargent have gone as far as to claim that it is an ‘essentially contested concept’ for which ‘no fixed definition as such is attainable.’ The contested nature of the term reflects the fact that there is no single historically consistent idea of utopia which can be traced, but merely various uses of the same word for different particular purposes within specific historical contexts. In compiling these articles together, I am therefore interested not in determining the ‘correct’ meaning of utopia, but rather in encouraging readers to consider its politics by exploring the ways in which the concept can be—and has been— invoked and their implications for our political imagination.

The initial pieces of this issue emphasise the tensions between utopian and real-world politics. In his long-form essay on Javier Milei, Michael Wakin questions the extent to which the newly-elected Argentine President’s anarcho-capitalist beliefs are sincerely held and whether he can realise a libertarian utopia in practice. From a different perspective, Martin Conmy argues that although the economic suc-

cess of Singapore transformed the city-state into a utopia, this has come at the detrimental cost of political liberty for its citizens. For both authors, utopian projects are often in conflict with the demands of the real world, and it is therefore crucial to consider the limits of practical politics.

The next three articles put forward a qualified defence of utopian thought for progressive politics, even as they acknowledge the limitations of utopianism.

By drawing on ancient Chinese texts, Max Junbo Tao suggests that Confucian visions of utopia highlight both the potential benefits and risks associated with implementing forms of political hierarchy and hence that they offer insights when considering issues of contemporary governance. Looking at it from another angle, Matthew Chiu claims that ‘protopias’ are valuable for inspiring realistic change. In contrast to utopian dreams of unattainable perfection, he contends, ‘protopian’ ideas can enable us to improve our society without succumbing to ideological fanaticism. Indeed, in his review of the anthropologist Daniel Miller’s recent book, Justas Petrauskas highlights the tendency of utopian theorists to overlook questions of social agency in fa-

vour of speculative ideals, and he emphasises the importance of drawing lessons from the pragmatic achievements of existing ‘good enough’ societies.

The following contributions by Dorkina Myrick, Luiza Świerzawska, and Labëri Leci collectively point towards the utopian potential of recent technological advances. Where Myrick demonstrates how brain-computer interface devices (BCIs) have the potential to make significant positive impacts on human communication and medical treatment for conditions like depression and anxiety, Świerzawska shows in her review of Philip Seargeant’s newly published book how popular forms of technology such as social media and AI chatbots embody hopes for a universal language and social harmony. But if Świerzawska evinces scepticism towards techno-utopian attempts to control human language, Leci advocates full-on resistance against algorithm-based social systems. According to the latter, it is only by actively challenging the implicit biases of such systems can technological advancements genuinely contribute to the realisation of utopia.

The final pair of essays discuss

radical endeavours to re-conceptualise utopia for transformative futures. Morien Robertson, through elaborating on Martin Hägglund’s democratic-socialist utopian vision, argues that it is only by forging existential meaning and purpose can a post-capitalist society in which freedom is realised be developed out of the status quo. In his review of Mathias Thaler’s recent work on utopian fiction and theory, Wallerand Bazin emphasises the importance of paying attention not merely to the utopian imagination but also to lived practices of utopia. For Bazin, these practices represent prefigurative forms of politics that are vital as we come to navigate a climate-changed world.

Let me end by extending my gratitude to all the contributors whose insightful perspectives have enriched this issue, as well as my appreciation to the dedicated editorial team whose diligence and expertise have made it possible. It is always a pleasure to be able to pursue a project of which one is passionate.

Ming Kit Wong Editor-in-Chief

A Libertarian Utopia in Political Practice: Will Anarcho-Capitalism Take Root in Argentina?

Wakin

Michael Wakin is an MPhil student in International Relations at Mansfield College, Oxford. Before attending Oxford, Michael graduated with a bachelor’s degree in economics from Kenyon College and worked as a research analyst for the U.S. Department of the Treasury in Washington, D.C. Michael has reported from South Africa, Lebanon, and Argentina, as well as interviewed former National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster and former Secretary of State George Shultz. He was awarded the 2024 Overseas Press Club Foundation Scholar Award.

On the bright, hot summer day of 10 December 2023, Argentine President Javier Milei cruised down Avenida de Mayo in a 1960s-era Chrysler Valiant III convertible surrounded by a phalanx of black-suited security guards on foot. As he waved to scattered crowds of supporters speckled with vibrant yellow and light blue flags, one could almost feel the cautious optimism in the air. Milei was travelling to La Casa Rosada, Argentina’s presidential residence, from the steps of Congress where he had just made history after giving his inaugural speech as Argentina’s first-ever libertarian president.

On his political journey to the heart of power in Argentina, Milei laid out a radi-

cal free-market vision for the country. He called for dramatic slashes to public spending, the shuttering of the country’s central bank, and the replacement of the peso with the U.S. dollar as the country’s official currency. He railed against the political establishment with gusto, referring to politicians as a “caste” that plundered the Argentine public.

Milei has described himself as an adherent of anarcho-capitalism, a fringe branch of libertarianism that calls for the abolition of the state and the privatization of all government provisions. The ideology builds itself upon a philosophical foundation that all individuals should be free from the threat of coercion, where the worst offender is the gov-

ernment through involuntary taxation. Milei, whose eccentricity knows little bounds, has presented himself at public events as a colourful alter ego named General Ancap, the fictional leader of ‘Liberland,’ tasked with the goal of ‘kicking Keynesians and collectivists in the ass.’

Milei brings these radical ideas into the presidency amidst Argentina’s worst economic crisis in two decades. The annual rate of inflation is expected to reach a punishing 200 per cent, poverty is on the rise, and critical foreign currency reserves are dwindling. Argentina’s rapidly deteriorating economic situation serves as a backdrop to the resonance that Milei’s anarcho-capitalist-inspired campaign found

among the electorate. Understanding the intellectual tenets of this extreme political ideology, how they have shaped Milei’s thinking, and the extent that he will govern according to these libertarian ideals will have critical implications for the future of South America’s second largest economy.

‘I think Milei is a person who seems to have strong personal and moral convictions,’ Marcelo Garcia, the communications director at BICE, an Argentine development bank, said in an interview shortly after Milei’s inauguration. ‘He seems to be a person that thinks he has a calling. He’s on a mission. We’ll see how that mission plays out in office.’

Milei’s Intersection with Anarcho-Capitalist Thought

In reconstructing Milei’s awakening to anarcho-capitalism, the writings of one academic, Murray Rothbard, seemed to have had a particularly important influence. A pivotal moment came in 2008 when Milei first encountered anarcho-capitalist ideas after a colleague shared an article written by Rothbard. Milei, who is a trained economist and at the time was 38, said that this article provoked an intellectual U-turn that made him question all of his prior economic training and knowledge.

Rothbard – an American academic who coined the term ‘anarcho-capitalism’ in 1971 and studied under Ludwig von Mises, the leading thinker of the Austrian School of economic thought – is the central intellectual figure of anarcho-capitalist theory. Rothbard lays out his core beliefs in the 1973 tome For a New Liberty: The Libertarian Manifesto, which was neatly summed up in the introduction by Llewellyn H. Rockwell as ‘not just a case for cutting government but elimi-

nating it altogether, not just an argument for assigning property rights but for deferring to the market even on questions of contract enforcement, and not just a case for cutting welfare but for banishing the entire welfare-warfare state.’ To give a more politically practical feel to the extremity of Rothbard’s thinking, he wrote prior to the 1980 U.S. presidential election, ‘The No.1 threat…to the liberty of Americans in this campaign is Ronald Reagan,’ suggesting Rothbard’s proclivity for freedom even outflanked Reagan.

According to an associate, another anarcho-capitalist text that influenced Milei was The Market for Liberty written in 1971 by Linda and Morris Tannehill, an American couple. In 2014, Jorge Trucco, an Argentine translator and professional fly-fishing guide, translated the bookinto Spanish for the first time, increasing the accessibility of the text within South America. Trucco first met Milei in 2014 at a presentation for the newly translated book and claims The Market for Liberty had an effect on Milei’s thinking. ‘He saw us talking in the same terms and concepts from The Market for Liberty. It was sort of incredible because [Milei] started saying certain things [on television] that were written in The Market for Liberty,’ Trucco said in an interview.

The Market for Liberty paints a radical vision of a stateless society free from any form of coercion or threat of force. The book is part philosophical musing on the sanctity of individual rights (‘there is no such thing as minority rights or any other form of collective rights’); part defence of the self-regulating nature of the market (‘without freedom of the market, no other freedom is meaningful’); and part anti-government screed (‘in a

complex society with a complex technology and nuclear weapons, [government] is suicidal idiocy’). Questioning why others do not similarly view government as an unnecessary evil, the authors posit that people simply do not yet have the ‘ability to generate or even to accept new ideas.’

Libertarian Utopias in Political Practice

Anarcho-capitalist thought is typically expressed in sweeping, dogmatic absolutes that can have a seductive simplicity. True believers seem to have a habit of referring to those with the slightest intellectual disagreement as ‘socialists,’ ‘communists,’ or ‘collectivists’ – or sometimes all three in the same breath. Perhaps unsurprisingly, there is very little evidence that any adherents of anarcho-capitalist doctrine have successfully translated this utopian vision into political practice.

Attempts have varied in grandeur and design, ranging from micro-nations to small enclaves. Take for instance the previously mentioned Liberland, which is in fact a real place. Founded by a former Czech member of Parliament, Vit Jedličkan, in 2015, the micro-nation resides on a tiny sliver of disputed land between Croatia and Serbia. Jedličkan has said Liberland is his attempt to build ‘the freest country on the planet’ where taxation is voluntary and democratic processes are powered by blockchain. As of now, the nascent micro-nation has no diplomatic recognition nor a single inhabitant.

Another unfortunate ultra-libertarian experiment was the Free Town Project, a libertarian scheme founded in 2001 by a Yale PhD student to ‘take over a tiny New Hampshire town, Grafton, and trans-

form it into a haven for libertarian ideals – part social experiment, part beacon to the faithful,’ writes author Patrick Blanchfield. At its height, the Free Town Project drew over 6,000 eccentric free-marketeers, united in their belief in the infallibility of the market, radical freedom, and rejection of statism in any form. New residents engaged in an enthusiastic campaign to cut public spending and resist government authority. ‘Despite several promising efforts, a robust Randian private sector failed to emerge to replace public services,’ Blanchfield wrote, quoting from A Libertarian Walks Into a Bear: The Utopian Plot to Liberate an American Town (and Some Bears) by Matthew Hongoltz-Hetling, a journalist who chronicled the Free Town Project. This utopian endeavour began falling apart when bears started descending upon the town and mauling residents. Hongotlz-Hetling hypothesized that these attacks in part stemmed from a failure of the town’s residents to properly secure their garbage.

There are other projects similarly fuelled by a pure impulse for an anti-government, free-market society – from the Peter Theil-funded ‘seasteading’ venture of floating cities beyond national sovereignties to the Jeff Berwich-backed ‘Galt’s Gulch Chile’ of a self-sustaining, libertarian paradise in the Chilean Andes. What seems to unite these cases is often a quixotic quest to draw reality closer to libertarian, utopian ideals.

Libertarianism Rising in Argentina

Argentina is a curious place for a libertarian movement to take root. Peronism, a working-class movement premised on considerable state intervention in the economy and generous welfare programs,

has dominated Argentine politics for decades. ‘There isn’t a clear precedent for libertarianism,’ Daniel Landsberg-Rodriguez, a founding partner of Aurora Macro Strategies, a geopolitical risk firm, said in an interview. ‘Argentina has the most bloated public sector, impatient voters, and the most permeable ideologies. So it is a tricky choice if you have to pick a country that is going to be at the vanguard of a social shift.’ Despite these inhospitable conditions, libertarian ideas appeared to gain some traction in Argentina between 10 and 15 years ago.

Around the time that The Market for Liberty was translated in 2014, a fringe anarcho-capitalist movement seemed to be bubbling to the surface in Argentina. Café Ancap, an informal gathering place of libertarian enthusiasts, was formed with the goal of spreading the gospel of anarcho-capitalism and deliberating the practical details for what a truly stateless society would look like. Conversations would range from the theoretical, such as should the role of the state be limited to defence or completely eradicated, to the mundane, such as how to address river pollution in an anarcho-capitalist society. The group grew over the years, beginning with four or five members and expanding to 40 or 50 attendees, meeting every Saturday from 4pm to 8pm at a big restaurant on Vincente Lopez Street in the posh Buenos Aires neighbourhood of Recoleta. Trucco told me that Milei attended two or three of these meetings around 2017, even speaking at one of them.

One day in December, I travelled to San Isidro, a leafy suburb of Buenos Aires, to visit Union Editorial, the first Argentine book publishing house dedicated exclusively to print-

ing libertarian and free market ideas in Spanish, including many anarcho-capitalist texts.

I met Rodolfo Distel, the firm’s owner who began publishing books in 2011, at his bookshop. He began pulling books off the shelves to show me them with the zeal of a missionary, proselytizing about the sins of the state. Hayek. Von Mises. Friedman. Rothbard. Rand. Benegas Lynch. Milei.

Mr Distel, who was the first person to publish Milei’s books, told me that there has been a surge in libertarian activity over the past ten years. Union Editorial began with 20 titles and has grown to publish over 500 titles. The publishing house also participates in a network of Argentine libertarian entities called Red Por La Libertad, or Network for Liberty – a loose coalition of think tanks, academic institutions, and political parties that meet once a year to exchange information and organise.

It is hard to say how popular these libertarian ideas are among the wider Argentine population, and whether they catapulted Milei into power. One hypothesis is that there isn’t anything intrinsically attractive about libertarian ideas to wide swaths of the Argentine public. Rather, it is simply an ideology that many people can latch on to as a way to express their anger at a political class that they feel has failed them time and time again. ‘I think libertarianism has become somewhat fashionable among a subset of youth voters who feel it answers Argentina’s permanent level of crisis,’ Jordana Timerman, an independent consultant based in Buenos Aires, said in an interview. ‘They haven’t seen any good answers, so it feels like the way a lot of us once felt walking around carrying Marx, like “oh, here is somebody with an

answer. Maybe it is in here.”’

True Believer or Political Pragmatist?

Perhaps the more important question for Argentina moving forward is the extent to which

Milei actually believes in anarcho-capitalist ideas and, if so, whether he will govern accordingly. Thus far, Milei has governed much closer to a traditional centre-right Argentine politician rather than a radical free-market fundamentalist. His first presidential decrees ushered in punishing austerity by means of shock therapy, including a 50 per cent devaluation of the peso, cuts to energy and transportation subsidies, and reductions in government ministries. He has not shuttered the doors to the central bank nor has dollarization been seriously considered as a policy option. Milei has formed a cabinet that is filled with establishment politicians and economists, including Luis Caputo as Minister of Economy – who previously served as President of Argentina’s Central Bank from 2017 to 2018. ‘The team he has assembled is not a libertarian team. He might still have those ideas…[but] it is not libertarian at all,’ Mr Garcia, the communications director at BICE, told me.

Milei is in a deeply constrained position. He must navigate an Argentina economy that is on a knife’s edge with extremely minimal political support. His party, La Libertad Avanza, has only a handful of representatives in the Legislature and not a single governor, which are traditionally powerful players in Argentine politics. ‘On paper, he is the weakest president Argentina has ever had in their democracy,’ Mr Landsberg-Rodriguez told me. Milei has had to ally with traditional political parties because ‘there is no way he can govern beyond changing the flower ar-

rangements in La Casa Rosada’ unless he pacts with someone, he added.

When I asked Mr Trucco whether he believes Milei remains true to anarcho-capitalist ideals, he responded, ‘Yes. He is honest and sincere. He won’t change his principles… he will install a new concept of government, the individual, and the self-regulating market.’ Mr Distel agreed. ‘Javier could be a moral revolution. He is very strict. He doesn’t like lying.’

Alejandro Bonvecchi, a professor of public policy at Torcuato Di Tella University in Buenos Aires, is less convinced. Pointing to the policy steps Milei laid out during his inaugural speech, Mr Bonvecchi told me, ‘I think that speech is actually quite statist…He has his ideas. That’s clear but I don’t think he is terribly committed to them…They are showing themselves to be pragmatic, to have a foot on the ground, and not trapped in a cloud of their own rhetoric.’

When assessing Milei’s anarcho-capitalist bona fides and their implications for Argentina’s future, one must eventually confront the inherent tension of an ideology that envisions a stateless society rising to the presidency. ‘Libertarianism is inherently weakening of government which is something when you are in charge of a government you usually don’t want,’ Mr Landsberg Rodriguez said. Yet, some remain hopeful that a truly stateless society can eventually materialise. ‘You cannot dream of turning any country in the world today into an anarcho-capitalist society,’ according to Mr Trucco. ‘But I think that in the future, humanity will reach that point. I don’t know how long it will take. Maybe 500 years. But it has to happen.’

‘Disney Land with the Death Penalty’: Singapore and the Price of Utopia

Martin Conmy

From a certain angle, Singapore really does look like paradise. The East Asian city-state is at or near the top of virtually every international ranking of merit: it has the second-highest GDP per capita, the world’s best schools, and the seventh-highest life expectancy, and it ranks in the bottom ten for crime and corruption. Homelessness is basically non-existent, unlike in similarly rich and densely populated places like Hong Kong; the country has only around 500 homeless people, and housing is broadly affordable—three-bedroom flats can cost as little as US$217,000, or around four years’ wages.

What makes this all the more extraordinary is just how different things were when Singapore gained independence fifty-eight years ago. In 1965, GDP per capita was only $516—less than the world average and below countries like Mexico, South Africa, and Venezuela. Unemployment was at double digits, and almost 70% of Singaporeans lived in kampongs, or rural wooden shacks, which were often without running water and shared with farm animals. Moreover, the country had virtually no natural resources or developed industry.

Just as improbable as Singa-

pore’s future economic success, however, was its very survival: independence had been thrust upon it when conflict between the Malay and Chinese populations led to the island’s expulsion from Malaysia. As a result, Singapore’s only land border was with a hostile, far more powerful nation, and the country’s population was deeply divided. Race riots just a year earlier resulted in nearly 500 casualties. It should come as no surprise, then, that in 1957 Lee Kuan Yew—who would go on to transform the citystate as its first premier—described independence as a ‘political, economic and geographical absurdity.’

Martin Conmy is a second-year History and Politics student at The Queen’s College, Oxford.And yet, within the span of a single generation Singapore went, as Lee titled his memoir, From Third World to First. The development-at-all-costs focus of Singapore’s early leaders means that the kampongs are but memories for the millions of Singaporeans who now gaze out the windows of fancy condominiums at a skyline dominated by skyscrapers. Little wonder, then, that panjandrums of all stripes—from dictators Kim Jong-Un and Xi Jinping to former British Chancellor Richard Hammond and MP Wes Streeting have extolled the virtues of the so-called ‘Singapore Model.’

Yes, Singapore might look like paradise. But it is not. If there is anything the Singapore Model can teach us, it is not the sanctity of free markets or even the virtues of government intervention, as many have incorrectly claimed. It is that development is often a zero-sum game, with rapid progress in one area leading to rapid backsliding in others. The transformation of Singapore from developing to developed demanded social engineering on an unfathomable scale—a trade-off the government gives its people no choice but to accept.

The most obvious sacrifice Singapore has made is liberal democracy. But it is unfair, as many do, to call the city-state a dictatorship. According to the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index, Singapore is a flawed democracy—putting it in the same bracket as the United States (albeit with a much lower score). In Singapore, elections are held regularly, citizens are free to vote for opposition parties, and there is no ballot-box stuffing.

Singapore may not be a dictatorship, but neither is it particularly democratic. The People’s Action Party (PAP), which has ruled since independence, does not rig elections because it knows there is no need to. When in 2020 the PAP won 83 of the 93 seats in

“Yes, Singapore might look like paradise. But it is not... development is often a zero-sum game, with rapid progress in one area leading to rapid backsliding in others.”

the national legislature with more than 60% of the popular vote, the party viewed the results as a major failure because its dominance is so total. The government runs a blatantly unfair system of patronage, making voting against it an unsavoury prospect. In 2006, for instance, former Prime Minister Goh Chok Tong promised to spend $63 million on development in Singapore’s Hougang area if they voted PAP. But if they voted for the opposition, he warned, it would become a ‘slum.’ Moreover, the PAP retains total control over the drawing of electoral districts, resulting in a severely gerrymandered map with multimember constituencies that inevitably benefit the ruling party.

Freedom of speech, too, is severely curtailed. While foreign newspapers and anti-government media outlets are allowed, the government’s Protection From Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act gives it the power to remove or ‘correct’ any news article it wishes. Criticizing the

government will not see you ‘disappeared’ in the middle of the night by the secret police, but you might face defamation suits brought by a horde of government lawyers, which is among the PAP’s favourite means of suppressing dissent. The government has sued everyone from opposition politicians to foreign magazines—even for millions of dollars—and has never lost a case.

The right to protest is even more restricted—to legally organize a demonstration requires a police permit. Otherwise, the gathering is unlawful and often dealt with harshly. This happened in famous cases such as that of Jolovan Wham, who was arrested for holding up a sign with a smiley face on it.

Fundamentally, the Singaporean government does not see elections as a choice between the PAP or the opposition, but between loyalty and insubordination. The PAP gave Singaporeans wealth, safety and prosperity. Surely, electoral support is the least they could give in return. According to this line of argument, opposition voters are, as Premier Lee Hsien-Loong described them, ‘free riders’ in Singaporean society. Electing the PAP, as he put it, is the ‘duty’ of all good citizens. The farcical aspects of Singaporean democracy were demonstrated even more clearly in a 2006 speech by the then–prime minister, in which he famously stated that the opposition’s job was simply to ‘make life miserable for me so that I screw up,’ and that if they got too powerful, he would have to ‘fix’ them.

For many authoritarian leaders, the acquiescence of their people is the end goal of their

interventions. But Singaporean leaders have far more extensive aims. Perhaps the most infamous example of their paternalistic intrusions into Singaporeans’ lives is the ban on the sale of chewing gum, which was instituted in 1992 as part of a crackdown on littering.

Far more absurd, however, was the government’s ‘Operation Snip Snip’ in the sixties. Men with long hair were subject to a laundry list of punishments—they were the last to be served at government offices, they were fired from government jobs in some cases, and, if they were foreigners, were denied entry into Singapore. All of this, Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew explained, was necessary because ‘we did not want the young to adopt the hippie look.’

Indeed, Lee never shied away from admitting to his government’s intrusions into people’s personal lives. As he said in a 1987 speech: ‘I am often

“Fundamentally, the Singaporean government does not see elections as a choice between the PAP or the opposition, but between loyalty and insubordination.”

accused of interfering in the private lives of citizens. … And I say without the slightest remorse, that we wouldn’t be here, we would not have made economic progress, if we had not intervened on very personal matters —who your neighbour is, how you live, the noise you make, how you spit, or what language you use. We decide what is right.’ In other words, ‘If this is a “nanny state,” I am proud to have fos-

tered one.’ Wherever personal freedom stood in the way of Singapore’s sprint to paradise, it had to give way.

This conviction carries into the government’s management of relations between Singapore’s three main ethnic groups: Chinese, Malays, and Indians. No intervention has been deemed too extreme in the pursuit of ‘racial harmony.’ For example, public housing (in which most Singaporeans reside) is subject to a strict system of ratios in order to prevent the formation ethnic enclaves. To limit linguistic divisions between these groups, English was adopted as the country’s lingua franca. As such, most Singaporeans’ mother tongues are taught only as second languages.

But one group has always been neglected in this paternalistic quest for equality. Immigrants—who made up 2.5 of the city-state’s 5.7 million people in 2020—almost never enjoy the same quality of life as Singaporeans unless

they are highly skilled Western expats. As Human Rights Watch documented, work permits for most low-skill immigrants are tied to their employer, leaving them vulnerable to exploitation. Legal protections are few and far between: These immigrants are exempted from laws limiting labour hours, and are often transported in the backs of lorries, packed together like sardines, leading to thou -

“Give the people freedom, and they might decide they no longer want to live in a Utopia.”

sands of injuries and even deaths in the last decade. Living conditions are often horrid, with as many as twenty people to a room, all sharing a single bathroom. It’s no wonder that immigrants made up almost 90% of all Singapore’s COVID cases.

Fundamentally, studying Singapore reveals that there is an

enormous tension between utopia and freedom. Give the people freedom, and they might decide they no longer want to live in a Utopia—they might decide they want to litter, consume drugs, or do the bare minimum at work. In Singapore, by contrast, the people are, for the most part, only free to choose when their choices will not interfere with the ongoing project of national perfection.

From the perspective of a country like Britain—where the government exists in a perpetual state of chaos, and the healthcare waiting list exceeds Singapore’s entire population—it might be tempting to conclude that Singapore made the right call when it sacrificed freedom, liberalism, and accountability in pursuit of utopia. Singapore’s leaders are particularly fond of pointing to other nations (often India) which started from a similar level of development but pursued democracy instead, a choice for which they paid the price.

“In Singapore, by contrast, the people are, for the most part, only free to choose when their choices will not interfere with the ongoing project of national perfection..”

But there is increasing evidence that Singapore’s authoritarian bargain is coming under strain. A government can only function effectively without public accountability and a free press if it is squeaky clean; yet recent scandals, which have seen resignations and arrests for various corrupt dealings, including bribery and severe conflicts of interest, have shaken the PAP to its core. The success of Singapore’s authoritarian social engineering should not blind us to the fact that virtually everywhere else such policies have been tried—from Uganda’s ujamaa villages to China’s zero-COVID policy—they have ended in disaster.

A Reflection on the Confucian Utopian Vision of Society

Max Junbo Tao

Max Junbo Tao is a PhD candidate in Political Philosophy at the University of Hong Kong, previously a graduate student in Comparative Politics at the London School of Economics, and a CIOL-certified English-Chinese translator graduated from Durham University.

As the Chinese historian Lyu Simian observed in 1935, the utopian project proposed by Confucius (551–479 BCE) will be captivating for anyone interested in utopianism. Unlike those ideas that place hope in supernatural powers or great material abundance, the Confucian project emphasises the potential of an in-depth reshaping of people’s thoughts and behaviours to construct a harmonious, morally homogeneous culture. This, perhaps, makes a Confucian utopia appear more ‘practicable’, especially in the contemporary context of similar promises made on behalf of AI governance, surveillance technology and big data.

According to Confucius, humans had already achieved a utopia in the ancient Chinese world, and he called for a revival of the angelic human nature to go back to the ‘Golden Age’ of humankind. In a series of narratives similar to Hesiod’s Five

Ages in the ‘Ceremonial Usages’ chapter of the Classic of Rites, Confucius first described a utopian society of co-governance and harmonious order based on the public election of virtues and merits, where everyone lived in fraternity and mutual assistance — he named it ‘Grand Union (or ‘Great Unity’, Datong)’. Then, Confucius claimed that the fall of humanity caused social divisions and hierarchy, and praised ancient sage kings who established a range of downgraded but well-governed societal forms by disciplining the people — the category he named ‘Small Tranquillity (or ‘Moderately Prosperous Society’, Xiaokang)’. In this context, Confucius implied that the only way to respond to social and political disorder was to lead humans to return to the well-disciplined societies of Small Tranquillity first, and then gradually reach the ideal form of Grand Union.

This interpretive article aims to introduce this two-step utopian project as outlined in the Con-

fucian Classics, which conceives of society progressing from hierarchy to harmony. It will also reflect on the paradoxical ‘bad emperor’ problem, according to which utopian success hinges on the perfection of the ruler. Furthermore, it will discuss the contemporary implications of the Confucian vision of a hierarchical utopian society.

From Hierarchy to Harmony

For the first step to achieving Small Tranquillity, ‘Ceremonial Usages’ briefly outlines a series of historical models that later rulers could emulate, including ‘Yu, Tang, Wen and Wu, King Cheng, and the Duke of Zhou’, and the details of each model are scattered across different chapters and classics. According to Confucian narratives, there are two representative teachings for developing the intermediate form of society — the ‘Royal Regulations’ and ‘Great Plan’.

‘Royal Regulations’ (Wangzhi) is commonly interpreted as an outline of the ruling model devel-

oped by Wen, Wu and the Duke of Zhou and practised during the Zhou dynasty (1046–256 BCE). It establishes a strict, hereditary hierarchy from the sovereign to the feudal aristocracy and then to the lowest subjects. This is achieved by institutionalising most political processes, actions, and agenda settings and by comprehensively regulating various aspects of life — including natural rights, political duties, social status, family ethics, regular rituals, and daily behaviours. The king was to be the only defender and practitioner of virtues and ritual laws, supervising his subjects and restraining everyone’s desires. Confucius believed that the socio-political form described in ‘Royal Regulations’ would be the most systematic, practicable one — in The Analects, he commented, ‘How complete and elegant are its regulations! I follow Zhou.’

The ‘Great Plan’ (Hongfan) is a set of political principles recorded in the Classic of History, which is traditionally interpreted as a description of Yu the Great’s legendary ruling model at the beginning of the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BCE). Compared with the ‘Royal Regulations’, the hierarchy described in the ‘Great Plan’ is much more extreme and idealistic. The chapter involves nine divisions, and the core thesis is in its fifth, ‘The Establishment and Use of Royal Perfection’. This division proposes a ‘perfect’ model of rulership in which the most virtuous and mighty ruler governs all public affairs solely according to immutable principles and eliminates all personal characteristics prejudicial tendencies. Finally, the division concludes with a double-ranking hierarchy wherein the supreme ‘paternalistic’ one rules over all the others.

The rationale for establishing hierarchy is implicit in the dialogue between Confucius and Yan Yan (c. 506–? BCE), where Confucius explains how one achieves the

utopia of Grand Union. In the dialogue, Confucius demonstrated his basic, ‘Kantian-like’ belief in the universal principles and fundamental rules of morality and ethics grounded on the concept of Heaven, and he ambitiously shows how social progress can be effectively promoted by a sage ruler with absolute authority at the dominant position of the socio-political hierarchy. For Confucius, a ‘paternalistic’ hierarchy would enable the sage to deliver the lessons of virtue, establish the laws of morality, and regulate the rituals of social life to shape the thoughts and behaviours of his subjects. When such teachings, laws, and regulations become culturally and socially dominant, every member of society will be highly self-disciplined and able to act in accordance with the highest moral laws. Such a society will be in complete harmony, without conflict or crime, and political candidates elected by the public will be reliable and worthy of their office.

Thus, according to Xunzi (c. 300–c. 230 BCE), the essence of the socio-political transformation envisioned by Confucius is a long-term process of disciplining humanity through moral education and self-cultivation. And in ‘straightening the crooked wood of bad human nature’, the establishment of hierarchy is at the core of the project. Hierarchy not only institutionalises the privileges of the most ‘morally outstanding’ group in society, but also empowers the sage ruler to establish unchallengeable authority and influence.

However, here we can detect a problem in the transition from hierarchy to harmony — the process has as its necessary condition that the absolute ruler of the transitional societal form must be ideally excellent and wise. But how can we ensure the perfect excellence of the ruler and prevent the disaster that may result from the so-called ‘bad emperor’?

The ‘Bad Emperor’ Problem

As two successors of Confucius, both Mencius (c. 371–c. 289 BCE) and Xunzi noticed the ‘bad emperor’ problem. Mencius proposed a theory of legitimacy which empowered the people to resist an improper ruler. In the chapters ‘King Hui of Liang II’, ‘Li Lou II’ and ‘Exhausting Mental Constitution II’, Mencius repeatedly argued for the just resistance, exile, and even execution of a ‘bad emperor’. Furthermore, Mencius provided a solution to ensure the excellence of the rulership in ‘Wan Zhang I’: ‘When Heaven gave the kingdom to the worthiest, it was given to the worthiest. When Heaven gave it to the son of the preceding sovereign, it was given to him.’ In other words, as Sungmoon Kim underlined, Mencius suggested that sage rulership was not strictly based on blood inheritance but took the capability of potential successors into account, implying a virtue-based succession of outstanding candidates.

Xunzi similarly believed that the government should be formed by well-trained, ritual-regulated, and merit-selected officials to ensure the effectiveness of governance and care for the lower classes and vulnerable groups of society (as in ‘The Rule of a True King’). However, Xunzi denied Mencius’s defense of just uprisings and stressed instead the ‘political continuity’ of rulership based on blood inheritance. In ‘Correct Judgements’, Xunzi argued that a bad heir could exert influence for merely a short period, but a change of the royal bloodline would trigger political chaos and disrupt long-term moral and social progress. Thus, Xunzi emphasised the importance of maintaining a durable and stable system of government and downplayed the negative impact of a single ‘bad emperor’.

Neither Mencius nor Xunzi developed a comprehensive solution to the ‘bad emperor’ problem. Indeed, Xunzi’s emphasis

on political continuity and social stability may lead to a dystopia with extreme forms of domination. In the view of his student Hen Feizi (c. 280–233 BCE), a society based on blind obedience to political rule is in fact the most effective way of achieving his teacher’s dream of disciplining humanity.

A Contemporary Reflection

From a contemporary perspective, we may now have alternative ways to realise the Confucian utopia. Instead of a human sage ruler at the head of the political hierarchy, we can imagine a ‘Great Plan’ society in which a super-AI governs the whole community and manages every affair through massive surveillance, big data collection, and following pre-set rules and programs. Could such technologies work to shape our thoughts and behaviours and establish absolute moral harmony? If indeed they could, the situation would raise difficult questions, even if it were only a transitional stage. Can we claim that a harmonious order based on tyrannically restricting individuals’ actions and deliberately reshaping their mind to eliminate individual differences in a highly disciplined way is in fact a type of utopian society?

Still, despite its problematic aspects, the Confucian vision of utopia remains valuable for prompting us to reflect on forms of power concentration and political hierarchy. Given that a strong government can effectively introduce public policies and launch megaprojects to better its citizens, should we embrace at least some hierarchical elements in Confucianism as a means of dealing with highly divisive domestic issues and problems of democratic governance? As Gary Wickham once argued, if we take Foucault’s view that learning from history is to produce knowledge of the present, pragmatically reinterpreting past ideas can serve to inspire new sociological and political theories with progressive potentialities.

Towards Humane Utopias

Matthew Chiu

Matthew Chiu is a final-year Philosophy, Politics, and Economics student at the London School of Economics. He is interested in the political economy of innovation, the philosophy and economics of education, and political theory.

What is the solution to x = 1/0? The naive inductive logician argues that x is infinite. 1 divided by 0.1 is 10 and 1 divided by 0.001 is 1,000. As the denominator shrinks to zero, x seemingly surges towards infinity.

But the mature mathematician knows better: x is undefined, a contradiction at the limit.

Like the naive logician’s solution, utopia promises infinity: ceaseless joy, unbounded hope, and limitless love. Consider the Garden of Eden, where humans are free from evil, or Plato’s Kallipolis, where wise phi-

losopher-kings rule with their omniscience. Any captivating and congruent utopian vision contains a sweet equilibrium end state, an eternal reward. Unsurprisingly, these utopian visions inspire social change.

However, in representing an infinite vision for a finite species, utopias represent potentialities rather than prescriptions, answering what could be rather than what should be. Naively pursuing utopian ideas or striving for the infinite in a finite world would reflect a fundamental error in inductive reasoning. But how do we change the world if

not through our optimistic utopian ambitions?

A Better Approach

The mature mathematician presents a more appealing approach – both to finding the solution to the x = 1/0 problem, and to addressing the question of utopia. Her answer demonstrates a keen understanding that we can approach, perhaps even perceive, infinities — but never achieve them. Recent protopian thinkers have applied this wisdom to contemplating social change.

In the words of Kevin Kelly, founding editor at Wired Magazine, proto -

pia is ‘a state that is better than today than yesterday, although it might be only a little better.’ To me, protopian thinking represents a careful and reasoned approach to changing the

“Is protopia the middle ground between utopia and dystopia, a place that inspires realistic change but not existential hope?”

world: it focuses on tomorrow and looks into the far future without prescribing what the future is. In practice, this means making progress in the broadest sense — economic growth, technological development, urban rejuvenation, and educational reforms — but with consistent evaluation, optimisation, and reflection about where we are and what the road ahead should look like.

These alternative protopian ideas may initially appear drab in contrast to the striking and majestic utopian schemes. Is protopia the middle ground between utopia and dystopia, a place that inspires realistic change but not existential hope? Is protopia akin to the Asphodel Meadows, sprinkled with a hint of hope and the potentiality of betterment?

Perhaps. Yet the essence of the protopia, which considers the immediate rather than the infinite, is what a world mired in uncertainty and grounded in difference requires. In centuries past, there were low-hanging fruit to seize, basic sci -

ences to learn, mathematical concepts to discover, and political systems to develop! In those olden times, the world needed utopian visionaries — Plato, Thomas More, and Karl Marx — to propel our societies towards the future.

But today, we find ourselves at the precipice of an increasingly uncertain future. In just the first twenty-four years of the twenty-first century, we’ve seen old norms defrocked, new technologies abound, and global societies reshaped. Conceptions of freedom, democracy, and justice, the old stimulants of social change, are engrossed by moral confusion. Questions of profound significance remain unresolved. Embrace or regulate technology? Growth or degrowth? Less or more?

Such profound uncertainty beckons us to contemplate social change at the margins, taking one proven step at a time rather than aiming to reach the broad sweeping-stroke utopian dreams so vividly portrayed by utopian thinkers. Instead of dreaming of a city where everyone is healthy and happy, protopians think about plans for improving public healthcare. Instead of contemplating system change to address poverty, protopians consider how to change housing and transport policies. The protopian approach translates high-minded utopian ideals into action plans and disciplines lofty ideas with modern-day constraints. Through rigorous consideration, planning, and completion of tasks that will

launch us into the future, protopian ideas maintain an ambitious scope without falling into the familiar traps of utopian fantasies.

Against The Utopia

The claim against utopian thinking today is that it simplifies complex moral questions into single, clear, and didactical premises, making it the perfect catalyst for ideology and extremism in an incongruent world. If happiness = 1/x, where x is evil, capital, inequality, religiosity, stagnation, selfishness, greed, or irrationality, the utopian’s straightforward task would be to reduce x ad infinitum for maximum happiness. History is replete with the dark consequences of misguided individuals and societies intoxicated by utopian ambitions or the mindless

“Such profound uncertainty beckons us to contemplate social change at the margins, taking one proven step at a time rather than aiming to reach the broad sweeping-stroke utopian dreams so vividly portrayed by utopian thinkers.”

adherence to single-minded ideologies. Consider the Chinese emperors, obsessed with finding the elixir of immortality, only to die by their own hands from mercury poisoning. Reflect on the Roman Empire, whose lofty quest to expand without temperance caused its eventual collapse under its

weight. And contemplate the totalitarian regimes that destroyed and murdered to feed their vile ambitions. Their perilous fixation on achieving misguided perfection sowed the seeds of human catastrophe and misery.

And these utopian tales are undeniably attractive! For better or worse, the beautiful stories of sunlit utopian lands are etched in our collective consciousness. Indulging in these utopian narratives can be comforting in a harsh society. They delineate right from wrong. But the most compelling driver is our inherent fascination with self-improvement. As Jean-Jacques Rousseau brilliantly argued in his Discourse on the Origins of Inequality we have a drive to perfectibility; a belief that more is invariably better. One more util is desirable; a prophetic vision of ten, a thousand, infinite utils is irresistible! Questioning or deviating from these grand visions can appear unwise and downright irrational.

From these visions, we also tend to ‘Goodhart’ ourselves – to corrupt good measures of targets by allowing them to become targets themselves – into util-maximising oblivion through institutions and systems that optimise for facile objectives. I am reminded of Yevgeny Zamyatin’s novel We, in which the characters live infinitely mathematically optimised lives dictated by strict schedules. These characters exist in a collective utilitarian stupor masquerading as happiness — but is this true happiness

or just a corrupted measure of it?

Instead, protopian ideas posit that social change should be (on the margins) more quotidian. We exchange the certainty of the perfectible yet unachievable society for the collective Rousseauvian yearning to improve our society slowly but surely. Protopian ambition is hope made humble, harnessing what we know we can do better without limiting us to a particular version of a ‘desirable’ future. Protopian thinking avoids the danger of oversimplification, a true pitfall of grandiose utopian narratives. In the Origins of Totalitarianism, Hannah Arendt observed that ‘ideological thinking orders facts into a logical procedure which starts from an axiomatically accepted premise, deducing everything else from it; that is, it proceeds with a consistency that exists nowhere in the realm of reality.’ When cloaked in academic jargon and intertwined with political power and social capital, false utopian premises unwittingly escape the do -

main of reason and into the range of terror. The protopian view, with its inherent humility, avoids this danger.

The Non-Linear Arc of Progress

What I like most about protopian reasoning is that it considers our humanity — and the fickle nature of our personalities, ambitions, and desires — in aspiring for a better society. The linear movement towards uto -

“Protopians consider the human condition for what it is rather than what it should be.”

pia in a diverse and stochastic world is misguided. Karl Marx, envisioning a communist future, said that the ‘recipes for the cookshops of the future’ cannot be written today, acknowledging our limited prescience. Protopians recognise that changing the world is not progressing through levels in a game. It is not an optimisation problem. It is instead a continuous process of negotiation and renegotiation, constantly adapting to include different in-

dividuals, viewpoints, and ideas. It is adding variables to the denominator of our equation for happiness as we broaden our moral circle. Protopians consider the human condition for what it is rather than what it should be.

Utopian ambition provides a subtle sense of optimism and hope. Protopian thinkers should blend this optimistic, long-term spirit found in expansive utopian visions with the imperatives of the imminent. However, while experiencing the essence of utopian optimism is desirable, we must avoid intellectual and literal interpretations of these narratives. As Susan Sontag argues in her essay Against Interpretation, analysing and interpreting art ‘is to impoverish, to deplete the world... it is to turn the world into this world’. In the same way, we should view utopian narratives as bold and imaginative landscapes or magnificent cathedrals that inspire us and expand our horizons. From these visions, we should take a tinge of emotionality, a feeling for the infinite,

but not a plan for future action.

Into the Humble Future

The human condition embodies a duality. Unadulterated ambition and desire for self-perfection intertwine with mortality and humanity, which are more beautiful and daunting than our ambition. Utopian ideals call for ambition without the corresponding humanity or humility. But we must remember that utopia is the non-existent edge case, the solution to x = 1/0 that should only exist in our callow dreams. Protopias offer a meaningful solution that embraces the utopian aspiration by tempering its associ-

“We should take a tinge of emotionality, a feeling for the infinite, but not a plan for future.”

ated dangers. It acknowledges that the most meaningful human project does not scope or desire everything, nor is it an unnatural race to the heavens. Instead, it is one in which we accept our finitude and steadily strive for a better, more humane, and more beautiful world.

Lessons for Utopians from Anthropologists

Justas Petrauskas

This is a review of The Good Enough Life by Daniel Miller.

Justas Petrauskas is Managing Editor of the OPR and a final-year Philosophy, Politics and Economics student at Oriel College, Oxford. His main interests are in the institutional approaches to accommodating differences in diverse societies and epistemological issues in political theory and practice.

When asked what hopes or future goals he has for Estonia, Toomas Hendrik Ilves, its former president, remarked that it was to ‘become another boring Nordic country, like Sweden’. The year was 1993, and the newly independent Estonia was living through a tough transition from the USSR-styled command economy to a functioning liberal democracy. Ilves’ remark was not a quip: for the people in the ex-Eastern bloc, or for those struggling with poverty and insecurity in the Global South now, the promise of a safe and boring – if not perfect – Western life has been taken to be good enough.

How should we regard this

toned-down vision of a good life that, despite being so unambitious and anti-utopian, continues to find considerable support from people in different locations and with various backgrounds? This is one of the several puzzling questions that Daniel Miller, Professor of Anthropology at the University College London, seeks to answer in his new book The Good Enough Life. Miller’s project is premised on an attempt to unite philosophy and anthropology, two fields that have tended to develop independently of each other, by juxtaposing a philosophical enquiry into the nature of good life with an ethnography of people in a small Irish town living a life that seemingly can be charac-

terised as ‘good enough’. Having found himself fortuitously in Cuan – a pseudonym that hides the name of Skerries, a coastal town around twenty miles from Dublin – Miller came to be struck by the ‘love of Cuan felt by the people of Cuan’. The sixteen months he spent living in Cuan among a population of Irish retirees resulted in not only an appreciation of this love, but also the conclusion that it would be ‘hard to find another currently existing society that is demonstrably better’. The town had a vibrant and inclusive community, strong social ties, was broadly egalitarian without being restraining, and was consistently praised by its residents, a high portion of them being migrants from other

parts of Ireland. Notably, the praise was directed not to the residents themselves, but rather to the place and its community as a body: the migrants, locally termed ‘blown-ins’, would refer to themselves as having ‘lucked out’ by coming to live there.

Lurking beneath Miller’s careful and empathetic observations of the mundane day-today life of Cuan is an implicit engagement with ideal and utopian theorising. The town is not picture-perfect, and Miller never aims to hide this: intergenerational inequality with respect to housing affordabili-

“The sixteen months he spent living in Cuan among a population of Irish retirees resulted in not only an appreciation of this love, but also the conclusion that it would be ‘hard to find another currently existing society that is demonstrably better’. ”

ty, alcohol and drug abuse, and social stratification are factors that prevent Cuan from being a utopian model of a good life. Still, what makes Cuan stand out is that the lives people live here, while not being ideal, may well be described as ‘good enough’. Miller’s ‘good enough’ is not semantically equivalent to the complacent ‘sufficiently good’. Rather, he invites us to appreciate the unique success of Cuan in the contemporary context. Although a large part of Cuan’s success comes from its relative affluence and privileged location in Ireland, there are plenty of similarly affluent and privileged places that are nothing like Cuan when it comes to the strength of com-

munity ties and general satisfaction with life. Unlike most philosophers who theorise about the good life, Miller is taking a characteristically anthropological approach: comparing a society with other existing societies rather than against some ideal. The value of this approach lies in the fact that Miller thereby takes seriously and engages directly with the vision of life embodied in Ilves’s call for boringness or in the decision of millions of people to leave their homes for a life in Western suburbia. Utopian theorising often lacks this engagement, proceeding immediately with a derivation of ideal principles and ignoring potential inputs from relatively successful societies that currently exist. While one should not travel to the other extreme by regarding existing social practices as a sufficient source of inspiration for utopian theorising, Miller’s work demonstrates that utopian philosophers may benefit from embracing the middle way and learning from the approach of anthropologists. The Good Enough Life is a book of rare praise which aims to sketch out an appealing alternative to speculative utopias as a cognitive device that can be used to explore conceptions of a good life.

Indeed, the originality of Miller’s work lies in its attempt to go beyond the traditional ethnography: to juxtapose it with an exploration of a variety of philosophical views on the ideal life. The book’s odd-numbered chapters elaborate an ethnography of Cuan; the even-numbered ones are filled with accounts of a diverse set of thinkers from the Western canon. The relationship between the anthropological and philosophical chapters is complicated, and this is both a strength and a weakness of

the book. The discussion of thinkers such as Heidegger, Nusbaum, Rawls, Hegel, and Epicurus is sometimes used to provide the context for the philosophical findings of the ethnography, sometimes to challenge or be challenged by

“What makes Cuan stand out is that the lives people live here, while not being ideal, may well be described as ‘good enough’. ”

them, and sometimes, seemingly, just to drop a name in front of the reader. Thus, in the course of the book, one encounters a discussion of freedom in Cuan in the context of Nusbaum’s and Sen’s capabilities approach; a highly original investigation into the development of benign consumerism and environmentalism in the town, contrasted with a critique of Adorno and Horkheimer’s arrogant and shallow approach to the same subject; and an account of the importance of sports in Cuan that is presented with a brief side-discussion on the origins of ancient philosophy. Not a philosopher by training, Miller claims that in most cases, his interpretations of philosophers are intended to help us ‘reach a deeper comprehension of the ethnography’. For those with some background in philosophy, this might remind one – in a warmly familiar way – of their own early attempts of fishing in the pond of Western philosophy to make sense of the deepest questions concerning the world around oneself. Yet, that the philosophers in The Good Enough Life function as changeable lenses through which the world of Cuan can be perceived is frustrating for those hoping for a

more in-depth engagement with the ideas of the philosophers themselves. The book is not particularly comprehensive, and the clumsiness of the interchanging philosophical and anthropological chapters makes the whole project somewhat difficult to track.

Nonetheless, The Good Enough Life still holds important lessons for those theorising, investigating, and striving for the good life – utopians and anti-utopians alike. If there is a single takeaway from the myriad of carefully collected and analysed stories of Cuan residents engaging in local governance, playing bingo, planning their holidays, or reminiscing about the social problems facing the town, it must be that this flawed but good enough population can ‘teach us things about whom we might strive to be, that an ideal but speculative model could not’. The most significant of them is the power of communal self-creation. As Miller’s ethnography documents, the Cuan that currently exists was created by ‘blow-ins’, the people who arrived from other parts of Ireland after the 1960s. Some were following the memories of their childhood summer holidays there, from the time before the rise

“The book is not particularly comprehensive, and the clumsiness of the interchanging philosophical and anthropological chapters makes the whole project somewhat difficult to track.”

of cheap flights to Southern Europe; others were motivated by lower housing prices. The common feature was that these blow-ins needed a community that was not there – a need

which was not shared with the natives, who had traditional networks of church and family at their disposal. The beauty of Cuan, perfectly captured by Miller, was that its blown-ins managed not only to integrate successfully within the native population, but also to create a community through the active development of casual socialisation networks and groups – play troupes, amateur societies, expansive volunteering, and participatory local governance. In this sense, Cuan as it currently exists is entirely artificial and based on a vision of community that blow-ins brought with them – diverging sharply from the common wisdom of the popular branches of social philosophy

which emphasise the importance of the inherited cultural tradition and the embeddedness of the local social setting.

“Cuan as it currently exists is entirely artificial and based on a vision of community that blow-ins brought with them – diverging sharply from the common wisdom of the popular branches of social philosophy.”

Cuan is thus a unique example of collective agency producing a flourishing community despite its lack of historical identity. This community was forged from an imported vision with no historical links to the place, but this is a forgery that, as Miller writes, ‘captures the movement from forging banknotes to forging steel.’

With its emphasis on the importance of the residents’ collective action in the creation of their community, The Good Enough Life provides a necessary corrective for utopian theorising that consistently ignores the foundational role of agency within a given utopia. The original utopia of Thomas More, for instance, is founded by Utopus – a distantly past, exogenous figure that simply appears one day and creates the harmoniously functioning society. But by failing to give a precise account of how social life was created through a process of conscious collective agency, utopia becomes associated only with an elusive sense of historical non-impossibility. Ignoring the question

of agency leaves us with utopian blueprints that we, like More in the original Utopia, ‘wish rather than expect to see’. Miller’s Cuan is not a utopia, as he repeatedly stresses, but its focus on the foundational and self-conscious agency of its residents is a standard that utopian theorising would do well to follow. The community of Cuan, while not perfect, is beautiful and leaves a mark on the reader’s mind precisely because there is no Utopus,

“The

community of Cuan, while not perfect, is beautiful and leaves a mark on the reader’s mind precisely because there is no Utopus there.”

no external primordial mover there; only people who, in Miller’s words, ‘made a town that made them’.

Ultimately, the broad lesson that utopians – aspiring theorisers or practitioners –should derive from The Good Enough Life and Miller’s anthropological approach is that of attentiveness to collective agency and recognition of the epistemic value of social

practices on the ground. This lesson is especially salient because, on a fundamental level, anthropological and utopian approaches share a similar mode of engaging with the social world: both explore conceptions of the good life by providing us with images. In More’s Utopia, the account of the utopian society is triggered by an exchange between the figure of More and his well-travelled interlocutor Hythloday. Responding to More’s reservations about the feasibility of the abolition of private property in an ideal commonwealth, Hythloday replies that More’s position is not surprising, since he has ‘no image, or only a false one, of such a commonwealth’. The image that Hythloday proceeds to provide More and the reader with is that of utopia. Likewise, for most readers who are not native to Cuan, Miller carefully and attentively weaves an image of a place which, while falling short of the ideal, might well be good enough. Still, despite this similarity in modes of worldly engagement, utopian theorists as image-givers may well have a thing or two to learn from anthropologists as image-weavers.

Cognitive Utopia or Dystopia? Brain-Computer Interface Enhancement and the Technological Singularity

Dorkina Myrick

Dorkina Myrick, MD, PhD, JD, LLM, LLM, MPP (Oxon) is a physician and policy advisor who resides in the Washington, DC area. She is a 2016 graduate of the Blavatnik School of Government of the University of Oxford.

Futurists anticipate that technological advances in brain computer interface devices (BCIs) could revolutionize human cognitive enhancement. However, the more likely reality is that of BCIs as contributors to a dystopian rather than utopian near-technological singularity. BCIs collect, organize, review, synthesize, and translate data derived from brain recording devices attached to the scalp (electroencephalogram (EEG)), the brain’s cortex (electrocorticogram (ECoG)), or intracortically into an intelligible form to a machine which communicates information to the user. BCI devices can aid in converting thoughts into text or effectuate movement of pros-

thetic or motion-impaired limbs. As such, BCIs serve as potential vehicles for direct human and computer brain connection, interconnected brain communication, cognitive ability enhancement, and improved motor function. The technological singularity, according to the book of the same name by cognitive robotics professor Murray Shanahan, is the point at which “ordinary humans will someday be overtaken by artificially intelligent machines or cognitively enhanced biological intelligence, or both.” Mathematician and technology singularity nomenclature originator Victor Vigne described potentially “intimate” computer-human interfaces in The Coming Technologi-

cal Singularity: How to survive in the Post-Human Era. Proponents of technological singularity believe BCIs could aid humanity in achieving near-utopia through merging brain data with supercomputers.

There are many potential beneficial uses for BCIs, which were initially developed to aid in the medical rehabilitation of paralytic patients and other patients afflicted with spinal cord injuries or diseases involving neuromotor dysfunction such as stroke or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Research studies have shown that brain computer interface devices (BCIs) help restore functionality in patients with neurological or neuromuscu-

lar disorders such as complete or partial paralysis, traumatic brain injuries, infection or other related diseases. Severely paralyzed individuals previously unable to speak can communicate through BCIs via the translation of brain wave

“Proponents of technological singularity believe BCIs could aid humanity in achieving near-utopia through merging brain data with supercomputers.”

signals detected through electroencephalography (EEG) into text. EEG detects minute electrical signals fired by the brain, which are called P300 signals, between 300 to 800 milliseconds after the electroencephalography test subject recalls the memory of an image, conversation, or thought. An electrocorticography array (ECoG) senses firing from nerve signals that control muscles in vocal cords. A recording device captures signals and translates the recorded information into words. The BrainGate2 system, a neural interface device, has been used in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). BCIs aid patients with neuromuscular disorders through algorithms which decode and translate neural signals into motor activity in the voluntary movement of extremities. EEG signals read from BCIs can be used to power prosthetic devices that can assist paralyzed patients with motor function. Another example of a potentially useful clinical application of the BCI is with the medical condition locked-in syndrome (LIS) a neurological disease caused by injury to the brain stem in which the patient has cognitive function but no motor or communicative function. EEG sig-

nals can be translated into text to significantly improve the quality of life for LIS patients. Researchers also propose that BCIs could offer some hope for treatment of patients with depression and anxiety.

I.J. Good, former Oxford mathematician, postulated in 1965 in “Speculations Concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine,” Advances in Computers, that one day super intelligent machines would “incorporate vast artificial neural circuitry” indispensable to humans. Good continued: “Until an ultraintelligent machine is built perhaps the best intellectual feats will be performed by men and machines in very close, sometimes ‘symbiotic’ relationship.” Accordingly, BCIs can monitor and augment brain function and ability. BCI regulation of cognitive ability is possible for learning, memory, dreaming, sensory perception, emotion recognition, monitoring cognitive fatigue, gaming, entertainment, and brain-computer interconnectedness and networking. Recent research implies that brain computer interfaces may be used to communicate and translate imagery from dreams into recognizable actions. Lucid dreamers are cognizant of their dream states and capable of exercising some level of control over their movement.

Remington Mallett demonstrated these dreamers can move objects upon command using only their thoughts and the assistance of brain computer interface devices. Facial Emotion Recognition (FER) and detection of a range of psychological states are possible with BCIs through the measurement of facial landmarks. Mapping of facial features using deep learning model algorithms involves a convolutional neural network (CNN). Such deep learning

studies have shown EEG patterns which detect happiness, fear, surprise, anger, and a host of other emotions.

In addition to FER, BCIs can monitor cognitive fatigue in drivers who spend long hours on the road. In a similar fashion, research studies conducted by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration have shown that BCIs may aid in detecting cognitive fatigue in pilots and air traffic controllers. Such activities could contribute significantly to improving public safety. Precise and accurate neurocortical signals can be measured through the dense barrier of the skull without significant diffusion of the neuroelectric signal. Gaming using BCIs –also known as neurogaming, has been demonstrated, although additional research is needed before BCI such gaming becomes mainstream.

“Until an ultraintelligent machine is built perhaps the best intellectual feats will be performed by men and machines in very close, sometimes ‘symbiotic’ relationship.”

As a neuronal network, the brain is anatomically designed to allow information to flow freely from one part of the brain to another, controlling neuronal signalling throughout the human body. BCI technology could extend the brain neuronal network by increasing the capacity of such networks with applications and utility for the internet, up to and idealistically uploading brain tasks, operations, and data onto computer networks. The first BCI-like social network allowed three people to transmit thoughts to

each other’s brains. This brain to-brain interface technology is entitled BrainNet, and it utilizes EEGs and transcranial magnetic stimulation to detect and transmit messages. Technology which allows humans to send messages to one another through brain sensor signaling, however, is still in development. Further development of this technology will allow messages to be transmitted from individual to individual through cloud-based communication. The United States military has developed a neurocortical sensory device, the Utah array, which targets neurons more precisely than electocorticography (ECOG) devices. According to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the Utah array is an even more refined device for reading neuroelectric signals in the brain. Currently, the military is also investigating a host of other possible uses for BCIs, including covert communications, improving soldier mental resilience and performance, and bolstering national security.

Despite the positives, several negatives of BCI technology exist which could hinder BCI’s potential progress to futurist-described technological singularity. Traumatic brain injury can result from the implantation of an excessive number of BCI probes into the brain. Continued studies are ongoing as to whether the problem of traumatic brain injury can be resolved by altering the number of probes inserted into the brain. Moreover, scientific testing has shown that the BCI probes can become damaged over time via immune response to the BCI probes or normal wear and tear. Such damage has been associated with lost EEG signals or loss of functionality of the BCI devices. Evidence

from the Physicians Committee for Responsible Medicine (PCRM) indicates improper storage of bacterially and virally contaminated brain-computer interface devices could place individuals at risk for infection. This could be particularly true for brain interface devices which operate using deep brain probes and stimulation. Stress may adversely impact BCI performance. Potential problems with BCIs include ensuring precision and accuracy of the BCIs and operation. Precision ensures that the brain computer interface devices and operation are consistent with every use. Accuracy ensures that the brain computer interface devices correctly measure, amplify, translate, and communicate brain signals into text with every use. Cross-task neural architecture EEG search (CTNAS-EEG) frameworks can improve the accuracy of EEG signal recognition for a more effective use of the brain computer interface.

Users could consent to have their thoughts accessed. However, this may not be the wisest course of action. Currently, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) prohibits the collection of consumer data without the permission of the consumer. Despite BCI user permission, BCI technology would not necessarily be kept secure. Cyberattacks may occur, leaving the information gleaned from BCI devices vulnerable to malicious hackers. BCI hacking can result in damage to electrosensory devices or interconnected cloud-based computing communications systems. As such, BCI users must discern the integrity of BCI-enabled communications. Once BCI technology transitions from experimental to more widespread consum-

er use, the user consent could help mitigate responsibility of manufacturers and data network providers in the event that computer networks are hacked.

Aside from cyberattacks, users would potentially be susceptible to intentional or unintentional third-party possession of highly personal brain EEG data, allowing those with com-

“Once BCI technology transitions from experimental to more widespread consumer use, the user consent could help mitigate responsibility of manufacturers and data network providers in the event that computer networks are hacked.

mercial interests to profit from internal thought processes. In the United States, consumer data can be tracked through online consumer activity and ferreted to companies wishing to market to consumers via third-party cookies. However, the disadvantage is that advertisers can only target the demonstrated online activity of consumers. What if advertisers could access thoughts that consumers may not necessarily manifest through online browsing activity? For example, several technology companies have marketed direct-to-consumer (DTC) neuromonitoring BCI interface devices for commercial use.

The EPOC X by San Francisco-based company Emotiv offers a $999 neuromodulation wireless headset device, advertised as: “Featuring 14 channels, advanced real-time data