Vladimir Stankovic 101 greats of european basketball

Belgrade, may 2018.

Vladimir Stankovic

101 greats of european

basketball Belgrade, may 2018.

FOREWORD By Jordi Bertomeu, President & CEO Euroleague Basketball

A retrospective look at European basketball as proposed to us in this book leads us both to admire the enormous and endless capacity of our continent for creating talent and to recognise the ability of its main protagonists to evolve and adapt themselves to the different circumstances and vicissitudes that European basketball has gone through over the last few decades. Sport is not isolated from the political, economic and social conditions that have been defining our continent since the end of the second great armed conflict that Europe suffered in the twentieth century. Understanding what happened in the various countries, in the various blocs that shaped the post-war Europe and the

4

5

101 greats of european basketball

subsequent developments until today, is fundamental to realise how sport and therefore basketball in its turn lived according to the social and geopolitical guidelines of each moment. These circumstances have not been irrelevant at all to understand in which context some of the greatest stars of European basketball were born and raised and why, in some cases, they did not have the crowds’ recognition that athletes enjoy at present, not always with more merits or talent. For historical or cultural reasons, or accidentally in some cases, the European map of basketball has traditionally limited itself to the south, in the Mediterranean basin, and to the north, in the former USSR and in the new states that appeared later in the 90s. Throughout these years, the hegemonies have been passing from the hands of one country to another, from the mentioned USSR, the former Yugoslavia, Italy, Greece, Spain and Lithuania to the most recent countries of France and Turkey. This explains that our protagonists are from these countries in their great majority. Following my above reference to the enormous capacity for creating talent, I must specify something else. It is in the mentioned countries where different methods of knowledge transmission and sports training have been devised that have provided us with the names appearing in this book. In Europe, basketball is developed around the club. It is the basic and more important unit of our sport. Basketball schools from the Balkan countries or Lithua-

6

nia have produced and continue to constantly generate top players, coaches and referees of great quality at world-class level. This has happened even under difficult political and economic circumstances, which I have mentioned previously, and which give a perspective of the greatness of these schools. It is true that until the 80s, it was very hard to enjoy this talent out of their respective borders beyond international competitions. It was the time of the old rules that limited international transfers and even the freedom of movement of players within countries, also in the so-called Western Europe. After the opening of borders, the effects of the Bosman judgment, and lately the evolution of the NBA towards the concept of a global worldwide league, have entailed a radical change in the structure of the labour market of our players and coaches. At present we have European talent distributed on the court and on the team benches across all the continents, and this has also made us a world power. The history of European basketball also gives us an idea of the ability of its competitions to evolve, driven by the determination and vision of their clubs and executives. The creation of the European competitions in 1958 meant a turning point in the development of our sport, only matched by the incorporation of the North American professional basketball into the global competitions, such as the World Championships or the Olympic Games. At the same time, the domestic leagues have been evolving, increasing their „standards�, generating

7

best possible conditions and be able to offer all their talent to our fans. Managing our clubs upon the basis of a much wider and much more dynamic professional market than the one we had until the beginning of the current century. Adapting the players’ training programmes to the new market reality, where volatility and the rush to run too fast are becoming a risk. Competition and competitiveness have always been the decisive factors in the appearance of sports stars. Our policies, our rules and our decisions must promote these criteria if we want to keep on growing. Our organisations will need to understand that in the era of technological change, permanent communication and image, fans no longer understand entertainment in a passive way, but, on the contrary, they want to be part of the show and want to interact, and for this reason we need to be near. When physical proximity is no longer significant and the sports consumption is so different, we have to present our competitions and the relationships among the different stakeholders in such a way that we can satisfy millions of basketball lovers. It was the personalities of this book who gave that response in their time in history. These players have been the top stars on this road, and without them nothing that European basketball has achieved would have been possible. They are our example, and for this reason it is so useful to get to know them the way this book will allow us to do. Thank you so much, Vlady, for such a fervent effort.

101 greats of european basketball

greater competitiveness and making our sport accessible to the general public through the media, especially through television. An evolution that has also reached a pan-European level with the creation of an own league, the EuroLeague, whose mission is to bring the beauty and quality of European basketball to all the fans around the world. Never ever since 1959 have our clubs, players, coaches and officials enjoyed the attention they have today. Today basketball is the second worldwide sport thanks to the above. Although the book is retrospective, it is historical, because it introduces the characters who have built this bright present throughout the years, it is always necessary to look ahead and see the challenges facing us, anticipate the needs arising from this growth and look for the suitable solutions that will allow us to keep on growing. Nonetheless, without a doubt, the future cannot be designed without knowing the past. The road cannot defined if we do not know where we have come from. In this regard, this is a key book to provide us with models, make us aware of our strengths and our weaknesses, and prepare us better for this fascinating trip. The sports globalisation and its economy raise difficult and exciting challenges: Finding and properly managing the necessary resources to continue with the task of our predecessors has become a top priority. Defining the appropriate framework for our players, coaches and officials to perform their activity in the

A museum of Europe's basketball superstars My introduction to European basketball was a painful one. At the European qualifying tournament for the 1992 Barcelona Olympics, I was invited to play a morning pickup game with other journalists. A bald guy on the other team crossed me over with his dribbling skill in the way that is now called „breaking ankles” – but in this case literally left me with a swollen foot. After we lost the first game against his team, mine huddled to discuss strategy. „Somebody needs to help me with that bald guy,” I said, panting. A teammate of mine from Sports Illustrated looked at me like I was crazy. „That bald guy?” he said. „Don't tell me you don't know who that is.” It turns out that I was being schooled by Juan Antonio Corbalan, the subject of one chapter in this book, who had recently been making assists to another legend from these pages, Arvydas Sabonis. If I had known my good friend Vladimir Stankovic then, maybe I would have been saved from my embarrassment. The truth is that his collection here of 101 of the greatest retired players in European basketball was long overdue for more people than just me. The list of Europe's stars stretches from 1950s pioneers – some of whom, like Pino Djerdja, even today's most

8

knowledgeable fans might not know – all the way to the most recently retired legend, Dimitris Diamantidis. It amounts to walk of fame spanning the 60 years to date that European club competitions have given an international stage to basketball on the Old Continent. My own fascination with European basketball soon improved my knowledge. At that Olympics qualifying tournament, I quickly found my favorite player, Jure Zdovc, whose story is also here. He missed those Olympics by one shot, but a year later he won the EuroLeague in one of the biggest upsets ever. At Barcelona Olympics themselves, Sarunas Marciulionis, another protagonist of this book, took me on the Lithuanian national team's bus to do an interview, and I also met Arturas Karnisovas, another player you can read about here. The first EuroLeague game I saw live was in 1996, after I had moved permanently to Spain. Caja San Fernando of Seville, coached by Aca Petrovic – he and his late brother Drazen figure in many of these stories – was hosting Partizan Belgrade in Seville. In the years between the Barcelona Olympics and that game in Seville, I had spent most nights sitting courtside as an NBA reporter, so close to the action that players often dripped sweat on my notebooks. On this night in Seville, also in a courtside seat, I soon stopped taking notes and just watched in growing disbelief, my mouth wide open in surprise. In hundreds of games during that era of isolation one-on-one plays in the NBA, I had witnessed nothing as close to true team basketball as I was seeing now. Before my eyes were 10 players in non-stop motion, offenses and defenses moving in split-second synergy like a high-speed chess match. I remember being struck, too, by the speed of shooters and defenders racing from sideline to sideline, through and around multiple screens, in a

9

ing through these stories is that the European game, though it may have missed the marketing expertise that leads to global recognition, never lacked for great talent, unique characters, intense competition and pulsating atmosphere. The men in this book, who come from all around the world, excelled at one thing above all – making the sport of basketball better than it would be now without their individual and collective genius as players. We see all the evidence for what they accomplished in the new heights of popularity and respect that the European game reaches with each passing season. Oddly enough, even though we didn't meet until much later, Vladimir and I both arrived to live in Barcelona about nine months before those 1992 Olympics. I just wish now that he had been my opponent in that pickup game. Presuming I could have defended him better, I would not have had to break an ankle to start my path to enlightenment about the European game, because I would have heard his first-rate stories sooner, too. Better late than never, he has helped to make me a true believer in European basketball's long and often under-recognized history of great players. Readers of this collection will soon become true believers, too. Editor’s note: For purposes of clarity and consistency, the major European club competitions, which went by many different names over the years, have been referred to throughout by their most recent names in each case: the EuroLeague, the Saporta Cup and the Korac Cup. Likewise, two of the major international country competitions are cited throughout the book exclusively as EuroBasket and the World Cup. Frank Lawlor, Editorial Director Euroleague basketball

101 greats of european basketball

horizontal chase scene that was new to me as it totally contrasted with the vertical, up-and-down style of the NBA. Partizan's Dejan Tomasevic, another subject here, was the leading scorer on that night, which I still consider my awakening to what makes European basketball unique. A couple of twists and turns later, I found myself as a head coach – for the first and last time of my life – in Spain's second division. There, my team battled Fuenlabrada, then led by another legend found here, Velimir Perasovic. I still consider it an honor that he was on the all-star team I coached that season, even though he couldn't actually play due to sickness. With all these experiences, I would have thought that I had received a good education in European basketball. Then I had the fine fortune to begin working with Vladimir at Euroleague Basketball, and I soon realized how much more there was for me to learn, especially about the subject of this book – the players who lifted European basketball to the place it occupies today. Together, they forged a unique, team-first brand of basketball that now appeals to many people – certainly to this lifelong fan and basketball journalist – more than any other. Today, we know beyond any doubt that the quality of players in Europe and their expertise in the practice of our sport is of the highest level. (Yes, I'm talking about practice!) But for the greats who paved the way for today's stars – the ones who developed the European game in relative obscurity, before international satellite TV and instant highlights on your telephone from halfway around the world – this collection is one of long-awaited justice and gratitude. My good friend Vladimir saw and spoke with many of them, reported on all of them, and collected this fascinating book full of their stories. What comes shin-

CONTENTS FOREWORD. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4 Jordi Bertomeu, President Euroleague Basketball A MUSEUM OF EUROPE'S BASKETBALL SUPERSTARS. . . 6 Frank Lawlor, Euroleague web-page editor 101 GREATS OF EUROPEAN BASKETBALL . . . . . . . . . 8 Vladimir Stankovic, author WENDELL ALEXIS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14 The Ice Man FRAGISKOS ALVERTIS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18 The man with 25 titles JOE ARLAUCKAS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22 The record man MIKE BATISTE. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 26 The star who found his second home ALEXANDER BELOV . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30 The “three-second” man SERGEI BELOV . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34 Officer and gentleman MIKI BERKOWITZ. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38 The man of the last basket DEJAN BODIROGA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42 “White Magic” KAMIL BRABENEC. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 46 The Czech scoring machine BILL BRADLEY. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .50 Senator between the hoops WAYNE BRABENDER. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 54 An atypical star TAL BRODY . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 58 Israeli basketball history

10

MARCUS BROWN. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 62 A champ in six countries JUAN ANTONIO CORBALAN . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 66 A doctor among the baskets KRESIMIR COSIC . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 70 A player ahead of his time ZORAN CUTURA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 74 A great from the shadows DRAZEN DALIPAGIC. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 78 The sky jumper IVO DANEU . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 82 The first great Slovenian RICHARD DACOURY. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 86 Professional winner PREDRAG DANILOVIC. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 90 Simply a champ MIKE D’ANTONI. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 94 The NBA’s first “European” head coach MIRZA DELIBASIC. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 98 The last romantic DIMITRIS DIAMANTIDIS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 102 A diamond on the court VLADE DIVAC. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 106 An icon without a ring GIUSEPPE-PINO GJERGJA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 110 A Bob Cousy clone ALEKSANDAR DJORDJEVIC. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 114 “Alexander the Great” JUAN ANTONIO SAN EPIFANIO. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 118 A Spaniard with a Yugoslav wrist

11

122 126 130 134 138 142 146 150 154 158 162 166 170 174 178

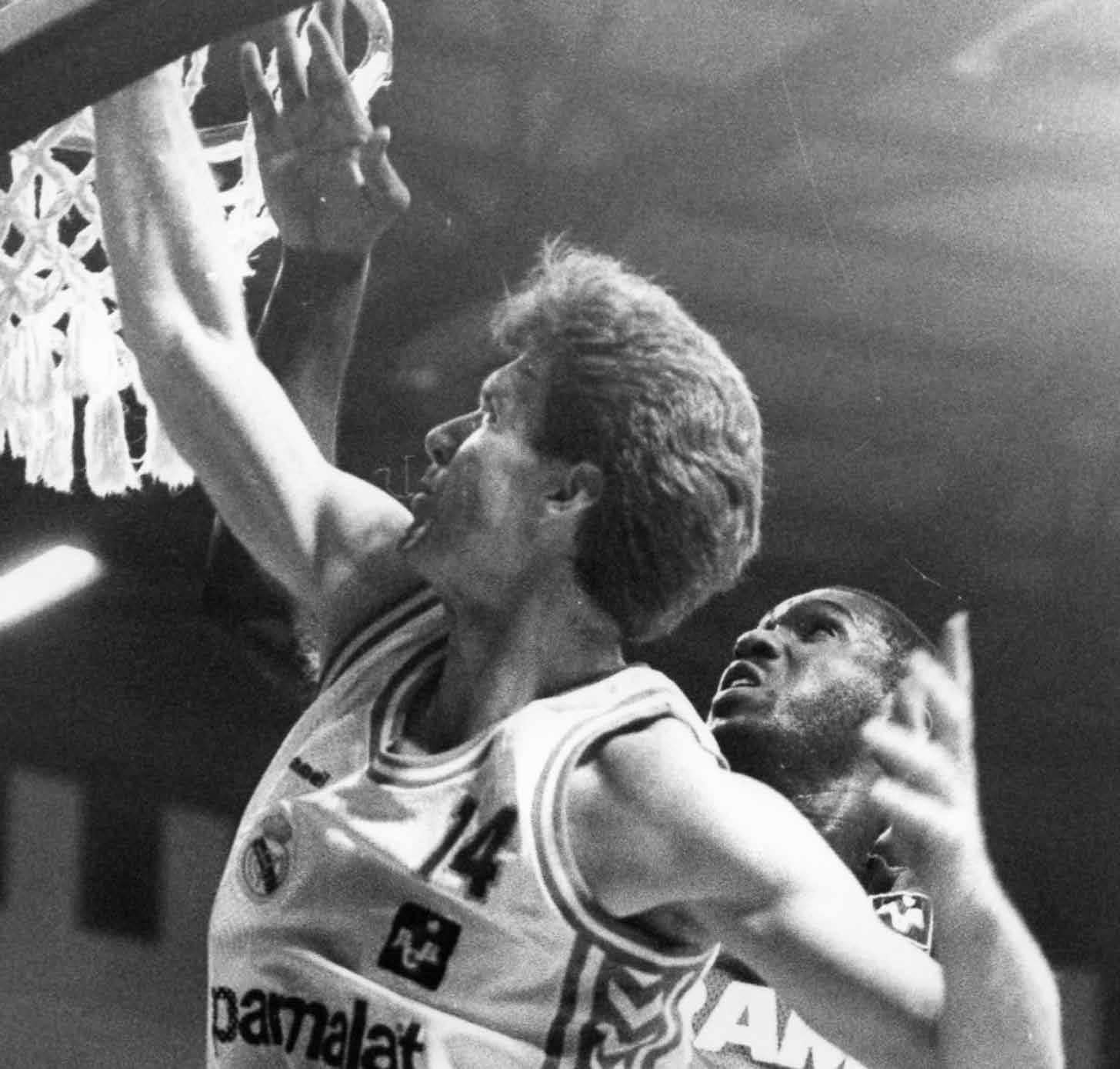

CLIFFORD LUYK. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The first great naturalized player KEVIN MAGEE. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . A mythical figure lacking only titles FERNANDO MARTÍN . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . A pioneer gone too soon BOB MCADOO. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . NBA and EuroLeague champ SARUNAS MARCIULIONIS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The Lithuanian machine PIERLUIGI MARZORATI. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . A Cantu legend DINO MENEGHIN . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The eternal champion BOB MORSE. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The legend of Varese CARLTON MYERS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The 87-point man MIHOVIL NAKIC. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . An octopus under the rims PETAR NAUMOSKI . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The Macedonian pearl AUDIE NORRIS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Barcelona’s adopted son FABRICIO OBERTO. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Hard-working star ALDO OSSOLA. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Von Karajan of Italian basketball THEODOROS PAPALOUKAS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . MVP off the bench

182 186 190 194 198 202 206 210 214 218 222 226 230 234 238

101 greats of european basketball

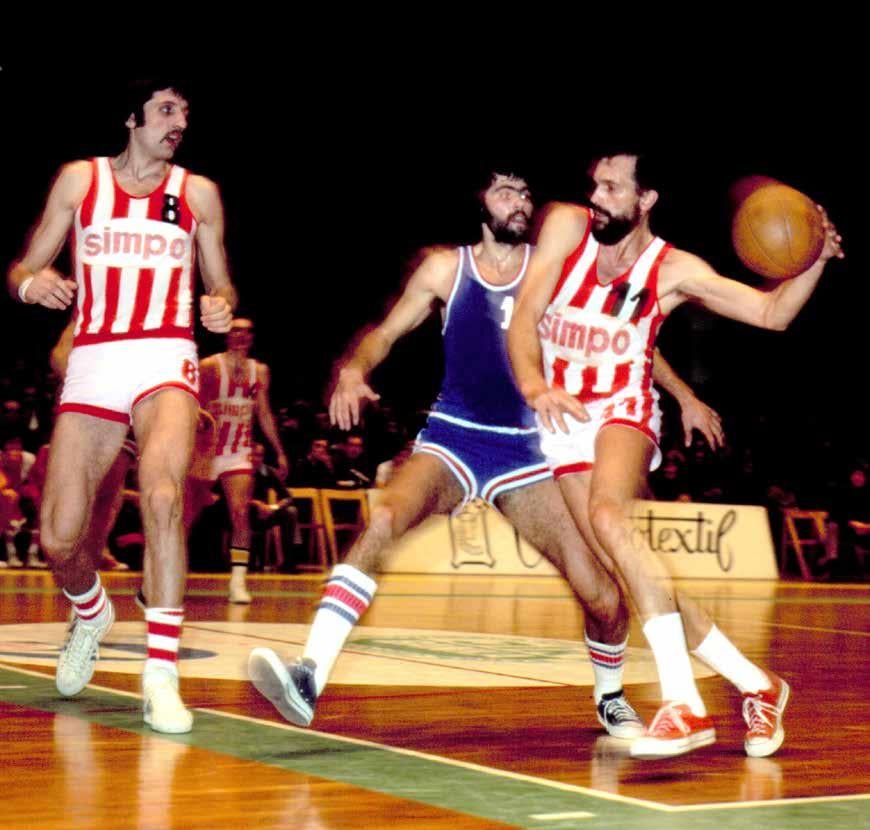

GREGOR FUCKA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Not your typical star NIKOS GALIS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . A scoring machine PANAGIOTIS GIANNAKIS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The Greek Dragon ATANAS GOLOMEEV . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Bulgarian legend ALBERTO HERREROS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . A three-point professional JON ROBERT HOLDEN. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The golden Russian DUSKO IVANOVIC. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Montenegro’s Holy Hand SARUNAS JASIKEVICIUS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Mr. Basketball ARTURAS KARNISOVAS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . King without a crown ODED KATTASH. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The King of Israel DRAGAN KICANOVIC . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The Cacak genius RADIVOJ KORAC . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The legend that lives on TONI KUKOC . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The Pink Panther of basketball TRAJAN LANGDON . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The Alaskan Assassin MIECZYSLAW LOPATKA. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The Polish legend

CONTENTS ANTHONY PARKER. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Two-time EuroLeague MVP ZARKO PASPALJ. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The man who changed the Greek League MODESTAS PAULAUSKAS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The first Lithuanian “king” VELIMIR PERASOVIC. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The professional scorer DRAZEN PETROVIC . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . An unfinished symphony RATKO RADOVANOVIC. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Mind over matter NIKOLA PLECAS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Saint Nikola MANUEL RAGA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The Flying Mexican DINO RADJA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The legend of Split IGOR RAKOCEVIC. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . A killer on the court ZELJKO REBRACA. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Blocks master CARLO RECALCATI. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Owner of two European three-peats ANTOINE RIGAUDEAU . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . “Le Roi” ANTONELLO RIVA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The Italian bomber DAVID RIVERS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The man of the final

242 246 250 254 258 262 266 270 274 278 282 286 290 294 298

12

EMILIANO RODRIGUEZ. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The Great Captain JOHNNY ROGERS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . A champ by any measure ARVYDAS SABONIS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The Lithuanian Tsar ZORAN SAVIC. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The title collector CHICHO SIBILIO. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The Dominican shooter LOU SILVER. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The man with the wrong name LJUBODRAG SIMONOVIC. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The rebel genius RAMUNAS SISKAUSKAS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Mr. Three-Pointers ZORAN SLAVNIC. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The first showman OSCAR SCHMIDT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The Holy Hand MATJAZ SMODIS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The humble champ NACHO SOLOZABAL. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The brains of FC Barcelona SAULIUS STOMBERGAS. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The man who made 9 of 9 triples WALTER SZCZERBIAK. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The superstar with the unpronounceable name ZAN TABAK . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . A triple Euro-champ with an NBA ring 359

13

302 306 310 314 318 322 326 330 334 338 342 346 350 354 358

362 366 370 374 378 382 386 390 394 398 402 406 410 414 419

101 greats of european basketball

CORNY THOMPSON. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . A big man like a playmaker DEJAN TOMASEVIC. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The center with point guard passing 367 MIRSAD TURKCAN. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The king of rebounds JORDI VILLACAMPA . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The 8 who was a perfect 10 OLEKSANDR VOLKOV. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The symbol of Ukrainian basketball GENNADY VOLNOV. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Europe’s winningest player NIKOLA VUJCIC. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Triple-double man CHRISTIAN WELP . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . A double Euro-champ DOMINIQUE WILKINS . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . An American from Paris LARRY WRIGHT . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The man with two rings MICHAEL YOUNG . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . A one-man team JIRI ZIDEK . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . A Czech legend JIRI ZIDEK JR. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Family matters JURE ZDOVC. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . The Golden Slovenian ABOUT THE AUTHOR. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

Wendell Alexis 15

earching data to refresh my memories about Wendell Alexis (July 31, 1964, New York), I found the video of the final minutes of the fifth game in the Italian League final series of 1989. On May 27, Enichem Livorno and Philips Milan, the European champ the previous year at the first Final Four in Ghent, played for the title. In the four previous games, Livorno – who had home-court advantage – won the first one with 39 points by Alexis; Milan won Games 2 and 3; and then Livorno tied it again with a win in Game 4, setting up the fifth, decisive battle. With 20 seconds to go, Milan was winning by a point and had possession. Mike D’Antoni held the ball for about five seconds and passed the ball to Roberto Premier, who took the shot and missed. In the resulting fastbreak for Livorno, Andrea Forti scored for an 87-86 win. The small gym in Livorno exploded. It was collective madness. The court was invaded by fans and the title was celebrated in between great euphoria and public incidents, including an aggression against Premier. The hero of that game was Wendell Alexis, with 33 points... but it was the most short-lived title of his career. The referees looked at video of the game’s last play in the locker room and decided that the last basket had been scored after the buzzer. So the title ended up in the hands of Milan, which had encountered a tough opponent in humble Livorno, thanks to the superb Alexis. That’s just one chapter in the long and successful career of Wendell Alexis, one of the best Americans

First stop, Valladolid The Golden State Warriors picked Alexis in the 1986 NBA draft with the 59th pick (one before Drazen Petrovic), but then did European basketball a big favor by not including him on the roster for that season. He had finished his university career at Syracuse with great numbers and, logically, he was expecting his chance in the NBA. But it just didn’t arrive. Like many before him, Alexis then tried his luck on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean. He was signed by Forum Valladolid in Spain, a humble team on paper, albeit one that would also sign Arvydas Sabonis three years later, in 1989. Only two games were needed to see that Forum had signed a star in Alexis. He would finish that first season averaging 18.2 points and recording a personal best of 44 points against Clesa Ferrol (8986), a game in which he played 40 minutes and made 19 of 26 two-pointers. Then, on July 14, 1987, Real Madrid announced the signing of Alexis. He was the third addition for the club that summer, after Jose Luis Llorente and Fernando Martin, who was coming back to Madrid from the NBA. Lolo Sainz, the legendary player and later coach of 101 greats of european basketball

Wendell Alexis

S

The Ice Man

who ever played in Europe. I wouldn’t dare make a selection of the best 12 Americans ever in Europe, but I am sure Alexis would be a serious candidate for the forward position. Standing at 2.04 meters, he was a versatile player. He normally played power forward, but he was also a good shooter and it was not unusual to see him move to small forward or even shooting guard. He was a complete player, made for offense. His thing was scoring points, but he also pulled rebounds and, thanks to his long arms, could also play great defense.

A

Vladimir Stankovic

Real Madrid, told me the reasons that pushed him to sign Alexis: “We were looking for a power forward, one who could not only rebound but also shoot. There was a lack of this kind of player on the market back then. We set our sights on Wendell and we hit the mark. He was a super player, a serious man who fit into the team just fine. He never hid. He had lots of self-confidence because he knew he could do many things. He had also great physical readiness and good legs to play defense, plus long hands to defend any opponent.” There’s a video available on the Internet that showcases his character perfectly. In the final of the Korac Cup between Real Madrid and Cibona, Madrid won the first game of the series at home by 102-89 in front of 12,000 fans. Fernando Romay and Brad Branson scored 25 points each and Alexis added 21, but the play of the game was a spectacular slam by Alexis over Croatian giant Franjo Arapovic (2.15). Also, Alexis volunteered to defend Drazen Petrovic, who managed to score 21 points but with bad percentages, making just 3 of 12 two-pointers and 3 of 8 threes. All credit goes to Alexis. In the second game, Petrovic scored 47 points, but Cibona only won by a point, 94-93, so Real Madrid took the trophy. It was the first European trophy for Wendell Alexis, who was 25 years old, just entering his prime. He ended that season with similar numbers to the ones he had in Valladolid: 18.0 points per game in the regular season, 18.7 in the playoffs. However, FC Barcelona ended up taking the title by winning the final series 3-2. Despite playing well, Alexis had to leave Real Madrid because back then the number of foreign players was limited to two, and Real Madrid had already signed Drazen Petrovic and Johnny Rogers.

16

Italian League champ... for a half-hour

Alexis chose Italy and the humble Livorno as his next stop, and he ended up being Italian League champ – for 30 minutes, at least. He had two excellent seasons there, scoring 20.8 and 19.4 points on average. After that, he moved to Ticino Siena, which at that time was far from the heights it would reach early in the 21st century. There he put up 20.3 points and 5.9 rebounds, after which he switched to Trapani, where he played his two best seasons in Italy. In 1991-92, Alexis scored 25.2 points and pulled 7.8 rebounds per game; in 1992-93, he improved to 25.8 and 8.3! It was the right time to sign for a big team again. He chose Maccabi Tel Aviv, where he won the 1993-94 Israeli League title and was that season’s MVP, but he decided to return to Italy. In Reggio Calabria, he posted his usual numbers, 20.9 points and 6.8 boards. The following campaign he landed in France with Paris Levallois, and once again was consistent, with 22.5 points plus 5.5 rebounds per game. I will never understand how no really big teams after Real Madrid and Maccabi ever signed this great player, but on the other hand, the fact that ALBA Berlin chose him to become the pillar of its growing project was the key moment for the evolution of the club. In the summer of 1996, at 32 years old, Wendell Alexis joined ALBA. He would stay there for six years, winning six straight German League titles plus three German Cups. He became the top scorer of all time in the club and a true idol for the fans of the team. Marco Baldi, general manager of ALBA for many years, told me about Alexis’s role in the club: “Wendell Alexis is not only one of the biggest players in the history of ALBA. He is a great personality and a long-time friend that I have the utmost respect for,” Baldi

17

rebounds per game, and was ALBA’s top scorer and second most-used player on court, with 31 minutes per game, behind only Derrick Phelps.

Euro-trophy at 40 At 38 years old, Alexis was thinking about retirement, but in December of 2002 he had an offer from PAOK Thessaloniki, and he delivered: 13.4 points and 5.8 boards in the FIBA Europe Champions Cup and 12 points and 5.5 boards in the Greek League. Was that the end of his career? Of course not! There’s nothing better than winning a title at 40 and Alexis did just that with Mitteldeutscher BC, even though he missed the FIBA Europe Cup final four due to injury. However, with 17.0 points, 4.7 boards plus 1.3 assists, Alexis was a big factor in Mitteldeutscher reaching the final. And in the German League, he was the usual Alexis: 18 points plus 6 rebounds per night. Personally, Wendell Alexis reminded me of Damir Solan, the great Jugoplastika forward of the 1970s. Alexis rebounded better and played closer to the rim, but aside from wearing the same number 12, they had in common the way they moved, their technique and the ease with which they scored points, the essence of basketball. When he finally retired at 40 years old, Alexis offered his expertise and knowledge as an assistant in high schools (Saint Joseph), the NCAA (New Jersey Institute of Technology) and even the NBA Development League (Austin Toros). And he has a lot to teach.

101 101 greats greats of of european basketball

Wendell Alexis

said. “With him, we went on an unprecedented string of victories. During Wendell’s six years with ALBA, we won six consecutive German championships, three German Cups and became a force in the EuroLeague. Wendell is still ALBA’s all-time leading scorer. In his time in Berlin, he earned the nickname ‘Ice Man’ as he was able to hit numerous game-winning and championship shots. In September 2012, we retired Wendell’s jersey (#12) in an emotional ceremony. Even 12 years after his last game, well over 7,000 fans attended the ceremony to celebrate an important figure in the history of ALBA Berlin.” In a spectacular homage in September of 2012, as Baldi mentions, ALBA retired Alexis’s jersey number 12. It made perfect sense, as it’s very difficult to imagine anyone other than the Ice Man wearing that number as he had done during those wonderful six seasons, winning nine titles and scoring 5,922 points in 341 games. Personally, I didn’t see many live games with Alexis, but I do remember when he played at Hala Pionir in Belgrade in February of 1989. In the semis of the Korac Cup, the great Real Madrid – with Martin, Biriukov, Romay, Iturriaga, Branson and Alexis, who scored 17 points – defeated Crvena Zvezda by 82-89. In Madrid, the score was 81-72 with 24 points by Alexis. That season, in 12 games, Alexis averaged 19 points. After that, I saw some games of his in ALBA’s jersey and especially at the 1998 World Championships in Athens, where a team of American “volunteers” appeared, due to the NBA lockout. He was the second-best scorer of that team, which won the bronze medal, with only 2 points fewer than Jimmy Oliver. His averages were 11.6 points and 4 rebounds. Against the Argentina team with Nicola, Oberto, Wolkowyski and a young Ginobili, he netted 20. He also made it to the modern EuroLeague during the 2001-02 season, putting up 16.4 points and 4.4

A

Fragiskos Alvertis

19

I

n modern basketball, it’s not easy to find examples like that of Fragiskos Alvertis, who played his whole career in the same club. Eternal love between Alvertis and Panathinaikos Athens lasted for 19 seasons – from 1990 to 2009 – and continues today because the legendary captain is still close by, as team manager, ready to join in the celebration of a new title. Born on June 11, 1974, in Glyfada, an Athens suburb, Alvertis is one of the most-crowned players ever in basketball. With Panathinaikos, he won 25 titles, among them five EuroLeagues. Only one player, Dino Meneghin, has won more EuroLeague titles and only two others, Clifford Luyk and Aldo Ossola, have won as many. No player has won more than Alvertis in the Final Four era that began in 1988. With five titles and eight Final Four appearances between 1994 and 2009, he is living history of the competition. In his trophy case we can also find 11 Greek League titles, eight Greek Cups and an Intercontinental Cup from 1996.

Start with a silver Only the best basketball connoisseurs will remember that the name of Fragiskos Alvertis – Frankie to his friends – was already in many scouts’ notebooks at the 1991 EuroBasket for cadets, played in his native Greece. In that tournament’s title game in Thessaloniki, Italy beat Greece by 106-91 as Andrea Meneghin – son of Dino – led the winners with 18 points. But the Greeks had many

101 101 greats greats of of european basketball

Fragiskos Alvertis

The man with 25 titles

reasons to be happy. Apart from the silver medal, players like Giorgos Maslarinos, Panagiotis Liadelis, Sotiris Nikolaidis and, especially, Alvertis had blossomed. His scoring average was 13.1, lower than Maslarinos (19.0), but Alvertis was much more promising. He was a tall kid with long hands and he was good at rebounding. But what drew the most attention was his shot. Due to his team’s needs, he played close to the rim, but he used every chance he got to move away from the basket, look for the corner of the court – his favorite spot – and drop his three-point bombs. His shooting technique, launching the ball from behind his head and with a high arc, was very difficult to defend. At 2.06 meters, he was more of a small forward than a power forward, but his versatility was one more advantage for him. At 17 years old, Alvertis had already made his debut with the first team of Panathinaikos, a club that at the start of the 1990s was under the shadow of eternal rival Olympiacos and the two Thessaloniki teams, Aris and PAOK. Little by little, with some great signings (Nikos Galis, Alexander Volkov, Stojko Vrankovic...) PAO – the nickname by which fans and media know the team – started a revival, until reaching its first Final Four in 1994 in Tel Aviv. In an all-Greek semifinal, the Greens lost 72-77 to Olympiacos and Alvertis scored his first 2 points in a Final Four. In the third-place game against Barcelona, a 100-83 victory for PAO, Galis had 30 points, Volkov 29 and Vrankovic 14, but next in line was Alvertis with 9 points. The following year, in the Zaragoza Final Four, history repeated itself: Olympiacos was better than PAO in the semis (58-52) and Alvertis stayed at 3 points. But in the battle for third place against Limoges (91-77) he scored 29 points, which would remain his best personal mark in European competition.

A

Vladimir Stankovic

European and intercontinental champ

Finally, the third time was the charm for Alvertis and the Greens. At the 1996 Final Four in Paris, Panathinaikos defeated CSKA Moscow in the semis 81-77 with 35 points by Dominique Wilkins and 13 by Alvertis. Barcelona was waiting in the final. In dramatic fashion, Panathinaikos won 67-66 in a game that is part of the history books. Alvertis shined with 17 points and almost perfect shooting: 6 of 8 two-pointers, 1 of 2 three-pointers plus 3 rebounds in only 23 minutes. He became a European champion at 21 years old. Galis had retired and Alvertis’s 1995-96 teammate Panagiotis Giannakis would do so imminently. Greek basketball was in need of a new face in its star system, and Alvertis appeared at just the right moment. In the big year of 1996, Panathinaikos completed a great run by also winning the Intercontinental Cup in September. The opponent was Olimpia BBC of Argentina, the South American champ, and that year the cup was played as a best-of-three playoff series. The first game was played in Rosario, Argentina on September 4. Olimpia won 89-83 with an interesting team featuring Lucas Victoriano, Jorge Racca and Andres Nocioni. Alvertis, with 21 points, was the best man on Panathinaikos, together with John Amaechi (23 points). In Athens on September 10, Panathinaikos won by five, 83-78, with 30 points from Alvertis. In the third game, on September 12, Panathinaikos won 101-76 with Byron Dinkins as best scorer, with 24 points, while Alvertis added 8.

The Obradovic era In order to play in the Final Four again, Alvertis would have to wait for the arrival of coach Zeljko Obradovic. At the 2000 Final Four in Thessaloniki, Panathinaikos got rid of Efes Pilsen in the semis by 71-81 with Dejan

20

Bodiroga (21), Zeljko Rebraca (15), Alvertis (11) and Johnny Rogers (9) as scoring leaders. In the final, which marked the start of a great rivalry at the turn of the 21st century, Panathinaikos beat Maccabi Tel Aviv by 82-74. Rebraca (20) and Oded Kattash (17) starred, but Obradovic kept Alvertis on court for 35 minutes. His 4 points and 3 rebounds seemed discreet, but Obradovic had discovered a great defender in Alvertis. His long hands and his speed contributed things that no stat sheet could reflect. The following year – in the season of “two EuroLeagues” due to the ULEB-FIBA conflict – Panathinaikos defeated Efes Pilsen 74-60 in their semifinal, but lost to Maccabi 67-81 in the title game of the FIBA SuproLeague in Paris. The following year, with a re-united competition, Panathinaikos again reached the Final Four, in Bologna. First it defeated Maccabi 83-75 with an outstanding Alvertis scoring 11 points while missing only one shot. In the title game, the Greens shocked host Kinder Bologna by 89-83 with Ibrahim Kutluay (22), Bodiroga (21) and Alvertis (11) as protagonists. In Moscow 2005, Panathinaikos suffered a rare semifinal loss to Maccabi (82-91) and defeated CSKA Moscow for third place (94-91). By 2007, however, the team was back to the top, this time on its home floor in Athens. Panathinaikos defeated Tau Ceramica 67-53 in the semifinals and outlasted CSKA Moscow 93-91 in a thrilling championship game. Alvertis lifted his fourth title. His fifth and last EuroLeague trophy arrived two years later in Berlin, even though he was semi-retired. He played at the start of the season, enough to be considered part of the roster of the champions despite not appearing in the Final Four. By lifting his 25th trophy overall, he retired as one of the all-time greats. Zeljko Obradovic had big confidence in him, and

21

for good reason. Alvertis was a very stable player who never – or hardly ever – played a bad game. If he didn’t stand out, he was at least a decent player who always contributed good things to Panathinaikos. If he didn’t score, then he pulled rebounds or guarded the most dangerous forward of the opponents. He always showed his character. He was the extended hand of the coach on the court. Obradovic has said many times that Alvertis was “the best captain I ever had.” While he triumphed with his club, he didn’t win any trophies with the Greek national team, whose jersey he wore 155 times. He played at EuroBasket in 1995 and 1997. He then missed the 1999 one due to injury after having averaged 18.1 points in the qualifying tournament. He was back in 2001 and 2003 and he also played the World Championships of Athens in 1998, but the

best he did was three semifinals and three fourth places: at EuroBasket in 1995 and 1997, and at the worlds in 1998. His last great competition was the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens. He retired from the national team at 30 years old. If he had waited one more year, he would have won the European gold medal in Belgrade in 2005 and in two more summers he would have had the world silver medal from Japan in 2006. It’s a shame, too, because Alvertis deserved some of that success. All the sweat and suffering from his hard work over the previous years were a big part of those two triumphs. However, despite being winless with the Greek national team, Fragiskos Alvertis will always have a place in the history books of Greek and European basketball.

101 101 greats greats of of european basketball

Fragiskos Alvertis

Five titles and eight Final Four appearances between 1994 and 2009, he is living history of the competition. In his trophy case we can also find 11 Greek League titles, eight Greek Cups and an Intercontinental Cup from 1996.

A

Joe Arlauckas 23

f a visiting team shoots 0-for-11 from the threepoint arc, probably the last thing you’d expect is that it won the game by 19 points, scoring a total of 115. You’d probably expect even less that one of this team’s players made history in a competition by scoring... 63 points! That’s exactly what happened on February 26, 1996 in a EuroLeague game in Bologna between Kinder and Real Madrid. The Spanish team won by 96-115, scoring 58 points in the first half, 57 in the second. Power forward Joe Arlauckas spent 39 minutes on court to score 63 points by making 24 of 28 two-pointers and 15 of 18 free throws. He also pulled 11 rebounds, dished 2 assists and had 4 steals for a total performance index rating over 80! In the official stats sheet we are only missing the fouls drawn figure, but if he shot 18 free throws, he received at least 9 fouls, and he committed only 2. It was one of those unforgettable nights of offensive fireworks, even though both Pablo Laso and Jose Miguel Antunez missed 3 attempts from the arc each (although Laso finished with 9 assists), Ismael Santos missed 2, Santi Abad, Zoran Savic and Arlauckas himself also missed 1 three apiece for Madrid’s 0-for-11 total. With 63 points, Arlauckas is still far away from the 99 that Radivoj Korac scored in the same competition in 1965, but he is still way above the modern Turkish Airlines EuroLeague record of 41 shared by Alphonso Ford, Carlton Myers, Kaspars Kambala and Bobby Brown.

Great night in Bologna “It was an incredible game,” Zoran Savic, the sec-

101 101 greats greats of of european basketball

Joe Arlauckas

I

The record man

ond-best Real Madrid scorer in that game with 16 points, remembers of that great night for Arlauckas. “Joe missed one or two of his first attempts from the field, but after that, he just scored everything. He played at ease and nobody even realized that he had scored so many points. We were all kind of surprised after the game, looking at the stats sheet. Joe was a natural-born offensive player, with a great four-meter jump shot and amazing timing for both shooting and rebounds. He knew how to play both facing the basket and with his back to it. He had many resources on offense and was a great teammate.” Of Lithuanian heritage, Joseph John “Joe” Arlauckas was born on July 20, 1965, in Rochester, New York. He had basketball running through his veins, but baseball was his sport of choice in his youth. He played basketball at Jefferson High School but in his first years at Niagara University he didn’t think the sport would become his profession. His last two seasons there were pretty good (17.4 points), so his size (2.04 meters) and his good fundamentals opened a door for him to the 1987 NBA draft. The Sacramento Kings picked him number 74 in the fourth round. He would share a locker room with Otis Thorpe, Harold Pressley, Joe Kleine, Ed Pinckney and Lasalle Thompson, all of them power forwards or centers, his position. He even scored 17 points in one game, but that was not enough for him to stay. He was released in December of 1987 after only nine games, with 34 points and 13 rebounds total. His new destination would be Europe. He joined Snaidero Caserta of Italy, where he would fill in for Georgi Glouchkov, the first European to ever play in the NBA. There, he would coincide with a super scorer like Oscar Schmidt and the great Italian prospect Ferdinando Gentile. In the Italian Cup final, against Varese, Arlauckas won his first title. Caserta won by 113-100

A

after two overtimes. Arlauckas contributed 13 points but before the end of the regular season he was cut for the second time in his career. In 12 games he averaged 10.7 points and 4.7 rebounds.

Vladimir Stankovic

Re-birth in Spain The new era in Arlauckas’s career would start in Spain. He landed in Malaga to join Caja de Ronda. At the beginning, he didn’t match well with coach Mario Pesquera, but little by little he started to adapt better and formed a great duo with center Ricky Brown, a former European champion with Milano. After beating Estudiantes, Joventut and Barcelona on the road, with 45 points by Joe against Barça, everyone realized that the Spanish League had a new star. In his two years in Malaga, he averaged 21.6 points and in 1990 he moved to Baskonia. The American coach Herb Brown, the restless scout Alfonso Salazar and president Josean Querejeta were the people behind that great signing. During three years in Vitoria, he averaged 22.0 points. With Pablo Laso, he formed a great guard-power forward tandem while the pair of big men was completed by Ramon Rivas of Puerto Rico. Before the Barcelona Olympics in 1992, the Lithuanian basketball federation tried to get Arlauckas to play for the national team because of his Lithuanian heritage, but he didn’t accept. However, he would play a bit later with Arvydas Sabonis in Real Madrid. In the Korac Cup, Europe discovered a great scorer. In two duels against Zadar, he scored 79 points (40 and 39). Against Banik of Czechoslovakia, he outdid himself with 87 points and 32 rebounds in two games. In the Korac Cup of 1992-93, he finished with an average of 32.0 points and 11.7 rebounds. As good as it gets. Three great seasons in Vitoria opened the doors

24

of Real Madrid to Arlauckas, where he would meet his “fellow countryman” Sabonis. Despite some problems at the beginning to understand each other, details were tweaked with a little bit of time. After that, simply put, they were one of the best combinations of power forward and center ever in European basketball. For the 1994-95 season, a still-young Zeljko Obradovic landed on Real Madrid’s bench to become the new coach. He already had two European crowns with Partizan (1992) and Joventut (1994). Nowadays, Arlauckas says that the coach he learned the most from was Obradovic. In return, the coach only has good words to say about one of his favorite players ever: “He was a killer in the most positive sense of the word,” Zeljko said. “I am very proud of having had him as a player and as a person. The wins and the points get forgotten with time, but you never forget about good people and Joe was one of the best.” With amazing memory, Obradovic quickly pinpoints the result against Kinder. He remembers the game as if it happened yesterday: “I was considered to be a coach who loved basket-control, low scoring, slow pace... Then, we had the game in Bologna with a true festival by Joe. He scored everything with great ease. He was a complete player, he had it all. He could shoot, rebound, he was fast, he had the technique, he was courageous... He was one of the best players I ever coached in my career.”

Zaragoza, 17 years later That same season of the great night for Joe Arlauckas, Real Madrid would become the European champion. The most-awaited title since 1978 arrived on April 13 of 1994 in the Final Four played in Zaragoza. In the semifinals, Real Madrid got rid of Limoges by 62-49 as Arlauckas scored 12, while in the title game, Los Blancos

25

defeated Olympiacos by 73-61. Joe had 16 points and 4 rebounds while Sabonis led the team with 23 points and 7 boards. One of the biggest assets for Arlauckas was his ability to play alongside bigger stars than him with no problems or envy at all. Except with Schmidt in Caserta, he always formed great tandems with all the stars he played with. After Sabonis left for the NBA, the new star in Real Madrid was Dejan Bodiroga, with whom Arlauckas also had a great understanding. In the 1997 Saporta Cup final against Mash Verona, won by Madrid 78-64, the list of best scorers for the winners was: Alberto Herreros 19, Joe Arlauckas 18 and Dejan Bodiroga 17.

Joe Arlauckas

Five titles and eight Final Four appearances between 1994 and 2009, he is living history of the competition. In his trophy case we can also find 11 Greek League titles, eight Greek Cups and an Intercontinental Cup from 1996. After five years in Real Madrid, Arlauckas went to Greece to join AEK Athens. The change of country, environment and the basketball style was really hard for him. He had a discreet season (13.8 points) and the following one in Aris Thessaloniki was a little bit better (17.4), but his best years were already in the past and in Spain. After retiring he went back to the United States but his love for Spain led him to return to Madrid. His experience helped him land a commentator spot with EuroLeague.TV. But his real desire would be teaching big men what he knows about basketball. And he knows a lot.

101 101 greats greats of of european basketball

A

Mike

Batiste 27

O

ctober 18, 2000. The first round of the newly-founded EuroLeague. Two days after the opening game between Real Madrid and Olympiacos Piraeus – Dino Radja scored the first basket in that game – host Spirou Charleroi defeated the St. Petersburg Lions by 80-68. Mike Batiste, totally unknown in Europe, scored 16 points and pulled 8 rebounds for the winners. It was the start of a brilliant European career for him. Batiste finished that season with averages of 16.1 points and 9.2 rebounds, more than enough for some teams from stronger leagues to put their eyes on him. Biella was not a huge team in Italy by any means, but the Italian League was surely a step up in competitiveness from the Belgian one. In Italy, he put up 12.4 points and 7.2 rebounds on average. That’s when Batiste was offered the chance that he didn’t get after his college years at Long Beach and Arizona State – the NBA called through the Memphis Grizzlies. He didn’t hesitate to accept the offer and played 75 games there with solid numbers: 6.4 points and 3.2 rebounds.

Rebirth in Athens Up to that point, Michael James Batiste (born November 21, 1977, in Long Beach) was a good player with notable talent, but somehow he had not taken off. He had to travel back to Europe, this time to Panathinaikos Athens, to take that leap of quality in his career. The

101 101 greats greats of of european basketball

Mike Batiste

The star who found his second home

coach of the Greens, Zeljko Obradovic, had already won two European crowns with the team in 2000 and 2002. He was looking for a versatile big man who could score under the rim, shoot from mid-range and pull rebounds. He set his eyes on Batiste, who from a physical point of view was a ‘copy’ of Corny Thompson, the big man who Obradovic had coached in Joventut Badalona in the 1990s and the hero of that club’s EuroLeague title team in 1994, thanks to one of his three-point shots. Thompson stood at 2.03 meters, only one centimeter shorter than Batiste, and he had great touch and great rebounding abilities. Obradovic found a similar style of player in Batiste. The numbers he had during his first season were not that spectacular: 7.9 points and 3.2 rebounds, but Obradovic was happy. In 2004-05 Batiste raised the bar to 11.4 points and 4.8 rebounds and then he did the same thing the following campaign (13.3 points, making 65.7% on two-pointers and 36.4% on threes, plus 6.6 rebounds). Titles in the Greek League and Greek Cup kept stacking up, but the fans wanted another EuroLeague title, and that arrived in the 2006-07 season, with a Final Four in Athens, to boot, and a championship game for the ages against CSKA Moscow that the Greens won 93-91. Batiste contributed 15 points and 12 rebounds in the semis against Tau Ceramica (67-53) and then 12 plus 5 against CSKA in one of the best EuroLeague championship games ever. Together with Dejan Tomasevic, Kostas Tsartsaris and Robertas Javtokas, Batiste was part of a wall that Obradovic had built on defense, but which also contributed many points on offense. Batiste was not your typical center. His physical attributes would probably put him more at the power forward position, but thanks to his rebounding abilities, his timing and the sixth sense that told him

B

Vladimir Stankovic

where the ball would go, he was really useful under the rims. He was also pretty good at offensive rebounds, which always is a great asset to minimize your own team’s mistakes. His lack of height was made up for by his basketball IQ, technique, high shot and speed. His build, at first sight, did not intimidate opponents much, but they all realized soon enough that they were facing one of the most dangerous and smart big men in Europe. After an off year in 2008, when they missed the playoffs, Batiste and Panathinaikos won another EuroLeague title together in Berlin in 2009, with a great big-man duo that Batiste formed with Nikola Pekovic. The Greens defeated archrival Olympiacos Piraeus in the semis (84-82), where Pekovic had 20 points and 2 rebounds and Batiste 19 points and 6 boards. In the title game, again against CSKA Moscow (73-71), neither of them was as efficient (6 points apiece), but the greatness and the variety of resources available to Coach Obradovic proved that the team could adapt to any kind of game. During that game, the leaders were Vassilis Spanoulis (13 points), Antonis Fotsis (13), Sarunas Jasikevicius (10) and Drew Nicholas (7), all of whom contributed to great accuracy from the arc (13 of 27, 48.1%). Two years later, in Barcelona, Mike Batiste lifted his third EuroLeague crown. He nailed 16 points and pulled 6 rebounds in just 22 minutes against Montepaschi Siena in the semis. He didn’t miss a shot, going 5 for 5, and was one of the key players. In the title game against Maccabi Electra Tel Aviv, Batiste shined again to lead his team to the title with a 78-70 win. In 24 minutes, he scored 18 points on 7 of 10 two-pointers plus 6 rebounds. In the last minute, with a 69-64 scoreboard, he received the pass from Dimitris Diamantidis to score

28

the bucket that would break the game open for the Greens.

Away and back Batiste was a much-loved player by the fans, teammates and the media. His popularity was huge in Athens, to the point that there was a book published in Greek about his life and professional career. And the feeling, from his own perspective, was mutual. “Just growing up as a little boy, seeing the neighborhood I grew up in, all the different distractions – gangs, drugs, all types of violence – I’d never thought in a million years I’d be in this position, let alone make it out of the circumstances I grew up in. So, it has brought me a lot of joy,” Batiste said in a EuroLeague.TV interview after winning his three EuroLeague titles. “And I’m very happy with the decisions I’ve made to keep coming back here to play every year for an organization like Panathinaikos, but also to live in a country like Greece. It’s very enjoyable here. My players and the people of Panathinaikos treat me as family. Also the people in society. I’ve embraced it. I’ve adjusted. And I can really call Greece a second home.” Nowadays, when it’s not rare to see players switching teams season to season, Batiste’s case is rather extraordinary, deserving of respect. He stayed eight seasons in Panathinaikos. He became a symbol of the club much like Juan Carlos Navarro for FC Barcelona, Felipe Reyes for Real Madrid, Derrick Sharp for Maccabi or even Diamantidis himself for Panathinaikos. “Growing up, I never thought I’d be around guys from Greece, guys from Lithuania or other parts of the world,” Batiste said. “And it’s really a special feeling to look at the next man like, that’s my brother right there, man. We would do anything that is necessary to win for

29

was also chosen for the All-EuroLeague First Team in 2010-11 and for the second team the following season. His EuroLeague career highs were a 35 performance index rating against Unicaja Malaga in 2009, 31 points against Cibona Zagreb with Charleroi in 2000, 15 rebounds against Benetton Treviso in 2006 and 6 assists against Maccabi in 2012. For Batiste, a new stage in his career has started in his native United States. He was the assistant coach of Spanish boss Jordi Fernandez at Canton Charge of the D-League, a team affiliated with the Cleveland Cavaliers. And he has since worked as a player development assistant with the Brooklyn Nets. This much is sure: the big men on any team where Batiste is around will surely enjoy a top-notch teacher.

Mike Batiste

one another. Even off the court, if there’s a personal issue, there’s always an ear to listen to you. You can call one of the guys here, go to dinner. We’re always there for one another, man. That’s the thing about this family here. It starts from the coach all the way down to the last player, and I think that’s the main reason we have so much success here, because we do whatever it takes for one another, to make sure you come in here, work hard and can be successful.” At the end of the 2011-12 season – after eight seasons winning eight Greek Leagues titles, five Greek Cups and three EuroLeagues – the then 35-year-old Batiste decided to sign for Fenerbahce, which came as a surprise to many. I am guessing it was a monetary issue, because when he went back to OAKA to play against his former team and former fans, Batiste didn’t feel well. He admitted that it was strange “running on the other side of the court”. Despite wearing the Fenerbahce jersey, he was received with honors and a standing ovation. Maybe that was the day when he decided to “get back home.” During the 2013-14 season, Batiste wore the Panathinaikos jersey once again. This time he wasn’t one of the team’s main contributors (3.5 points, 1.5 rebounds). His last EuroLeague game was Game 5 of a playoff series against CSKA Moscow, but it was no game to remember as Panathinaikos lost in Moscow by 74-44. Mike just played 2 minutes and didn’t score any points, but one game cannot erase the preceding 236 that left his lasting imprint on the EuroLeague. In Greece, Batiste won another domestic league and cup, which, together with a Turkish Cup, raised his number of national trophies to 17, to go with those three EuroLeague crowns. At an individual level, apart from being weekly and monthly MVP several times, he

For Batiste, a new stage in his career has started in his native United States. He was the assistant coach of Spanish boss Jordi Fernandez at Canton Charge of the D-League, a team affiliated with the Cleveland Cavaliers. And he has since worked as a player development assistant with the Brooklyn Nets. 101 101greats greatsof ofeuropean europeanbasketball basketball

B

Alexander Belov 31

T

here are great players and great careers marked by a single basket, a single game, a single detail. Sometimes that’s unfair, but it’s just inevitable. A man who belongs to this club of the world elite is Alexander “Sasha” Belov, the late Russian player who died on October 3, 1978, at age 27. That’s too short for a single life, but more than enough to leave a mark on basketball. His basket against the USA in the Munich Olympics title game in 1972, which the Soviet Union won 51-50, is part of the history of the Olympic Games and this sport. It’s an immortal play, unique in the last century, a basket that was worth a gold medal under strange circumstances: the repetition of a play; the famous three fingers in the air by FIBA secretary general William Jones, meaning that the last three seconds had to be repeated; the anger of the Americans who later refused to accept the silver medals. Born on November 9, 1951, in Leningrad (currently St. Petersburg), Sasha Belov started playing basketball in his native city. He stepped onto the international stage at age 17, when he played in the European junior championships in Vigo, Spain in 1968. His average of 7 points didn’t hint at a future star, but he won his first gold medal. In the final, the USSR defeated a powerful Yugoslavia with Slavnic, Jelovac and Simonovic by 82-73. A year later, he was already playing with the senior team at EuroBasket in Italy. He also had discreet numbers

Unforgettable Munich National team coach Vladimir Kondrashin, his coach also in Spartak, trusted Belov. He was a modern forward despite standing just 2.01 meters. He had long hands, broad shoulders and great rebounding skills. He was a nightmare for players guarding him. He was fast and agile, had good technique, and scored with ease. In Munich, on a star-filled team (Sergei Belov, Modestas Paulauskas, Anatoli Polivoda...) he was the best scorer with 14.4 points per game. Truth be told, however, that high average was due to his 37 points against Puerto Rico (100-87). Against Senegal, Yugoslavia and Cuba he scored 14 points each game, but his best moment was in the big final against the United States. He scored 8 points and pulled 8 rebounds, but his last basket made history. Curiously enough, it was a basket that made him as popular in the USA as in the USSR. Some fan clubs emerged and a young American woman traveled to Leningrad to ask Belov to marry her. But the love of his life was Aleksandra Ovchinikova. At the Saporta Cup final in 1973 in Thessaloniki, Spartak defeated Jugoplastika by 77-62 as Belov was the MVP with 18 points. Two years later, in Nantes, he 101 101 greats greats of of european basketball

Alexander Belov

The “three-second” man

(4 points) but he was not yet 18 years old. In 1970, he played another junior European junior championships, this time in Athens, and he won a new gold medal. His average rose to 8.5 points, but his best moments were yet to come. Before that, he lost his first final at club level. His team, Spartak, had reached the Saporta Cup final, but after two games, Simmenthal Milan was the better of the two. Belov scored 16 in his team’s home win, 66-56, but the Italians won the second game by 71-52 despite his 14 points.

B

Vladimir Stankovic

repeated the feat in a 63-62 win against Crvena Zvezda. He scored 10 points but his title collection was already impressive. I saw on TV the two games that the USSR played against Yugoslavia in the 1969 EuroBasket, with a Yugoslavia win in the group phase (the first one in an official game against the USSR) and a USSR win in the final, but I admit that I do not remember Belov. He didn’t shine in the World Championship of Ljubljana in 1970 (6 points) but in the Essen EuroBasket (8.5) he was already one of the pillars of the Soviet team. Then came Munich and his life would change. At the World Championships in San Juan in 1974, he won another gold medal, achieving the triple crown: Olympics, World Championships and EuroBasket. Aleksandr Salnikov was the best scorer in the USSR with 17.6 points, especially thanks to his 38 points against the Americans and 32 against the Cubans. Belov’s average was 14.6 points. I saw Belov live for the first time in 1975 at the Belgrade EuroBasket. He was not in his best shape, but his talent and potential were unquestionable. In the title game, his fight with Cosic and Vinko Jelovac, the Yugoslav centers that were way bigger than him, was impressive. That same year, he was drafted in the NBA by Utah with pick number 161 in the 10th round. The following year, at the Montreal Olympics, he played again at an elevated level, with 15.7 points, 5.2 boards and 4.7 assists, but he suffered one of the few disappointments in his career: the USSR ended up third, but he still won one more medal. He also had a triple-double in that tournament against Canada (100-72) as he scored 23 points, pulled 14 rebounds and dished 10 assists. Only he and LeBron James, who would match the feat many years later, hold the distinction of recording triple-doubles in the Olympics.

32

33

In January of 1977, I had the chance to see Belov in his native city, with the jersey of his team, Spartak. Radnicki Belgrade was playing the Saporta Cup there in the same group as Spartak. At home, the Soviets won easy, 99-84. I don’t remember how many points Belov scored, but I do remember he was the best man on the court. I have a picture with Coach Kondrashin, who talked to me about the importance of Belov for the games of Spartak and the national team. Alexander Gomelskiy also said that Belov was “the pearl of Soviet, but also European, basketball.” Some days later, on January 23 of 1977, before a Spartak trip to Italy, Belov was accused of smuggling orthodox icons, which were highly valued antiques in the West. He lost all his acknowledgments and medals and was expelled from the national team. There are several versions about what happened, from his own mistake to a setup to avoid his signing for CSKA. Some even said it was a trap to make Spartak a weaker team. This change turned him upside down. Some say that even before this incident, he complained about chest pains, but that doctors never found anything. In August of 1978, he was called to the national team again by Alexander Gomelskiy, who wanted him to help defend in Manila the golden medal from San Juan. Belov made it to the national team camp, but after just a few days, he had to leave because he didn’t feel well. Two months later, he died of cardiac sarcoma. He wasn’t even 27 years old and he still had a good career in front of him. However, he had also accomplished a lot of things for us to remember him as a great player, a humble and calm man off the court, but a lion on it. DATE | Sunday, November 2, 2014

Some days later, on January 23 of 1977, before a Spartak trip to Italy, Belov was accused of smuggling orthodox icons, which were highly valued antiques in the West. He lost all his acknowledgments and medals and was expelled from the national team. There are several versions about what happened, from his own mistake to a setup to avoid his signing for CSKA. 101 101 greats greats of of european basketball

Alexander Belov

Accused of smuggling

B

Sergei Belov

35

I

n 1991, FIBA published the results of a survey of their own about the best player in the history of FIBA basketball. The name at the top of the list was Sergei Belov, the great captain of CSKA Moscow and the USSR national team. Today, the result would probably be different, but nobody can deny that Belov is among our sport’s greatest ever. The Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in Springfield recognized this fact by inducting Belov in 1992 as the first European player ever to be included there. I had double luck: first I followed him as a player from 1967, the year of his debut with the USSR at the World Championships in Uruguay, until he retired after the 1980 Olympics in Moscow. I saw him in his most glorious moment, as the last carrier of the Olympic flame to light the torch at Lenin Stadium in Moscow, and also in his last games with the national team. After that, I met Belov as a head coach. We have spoken many times, but never like we did during EuroBasket 2007 in Madrid, where he gave me an interview for EuroLeague.net that caught many people’s attention all over Europe.

From a difficult childhood to glory Sergei Aleksandrovich Belov was born on January 23, 1944, in the village of Nashekovic, region of Tomsk. Before giving birth to Sergei, his mother survived the famous siege of Stalingrad with her elder brother. The father, an engineer, worked far from home and the family

101 101 greats greats of of european basketball

Sergei Belov

Officer and gentleman

got back together in 1947. The gift for the small child was a football, something scarce and valuable at that time. Sergei wouldn’t part with his favorite toy. He was a goalkeeper, but he also was into athletics, specifically the high jump. However, his quick growth to 1.90 meters decided his future. He started to play basketball and didn’t stop until the end of a brilliant career. His first coach was Georgiy Josifovitch Res. In the summer of 1964, while in Moscow to study, Belov was seen by Aleksandar Kandel, the coach of Uralmash in the city of Sverdlovsk, and he called Belov for his team. The promising teenager accepted and in the 1964-65 season debuted in the Soviet first division. In the summer of 1966, Belov made his debut with the USSR national team and in 1967 he was already a world champion in Uruguay with an average of 4.6 points. He scored a total of 32 points in the tourney, with a high of 11 against Japan. In 1968, another key moment in Belov’s life took place – he signed for CSKA Moscow. For the following 12 years, he would be the best player of the Red Army team under colonel Alexander Gomelskiy on the bench. Belov, like other players, was also an officer in the army, even though his only profession was playing basketball. In 1969, in Barcelona, he won his first European crown against Real Madrid. In an unforgettable game that CSKA won after double overtime (103-93), with big man Vladimir Andreev as the main star, getting 37 points and 11 rebounds. Both Belov and Andreev played the entire 50 minutes. Belov finished with 19 points and 10 rebounds. The following year CSKA lost the final in Sarajevo against Ignis Varese 79-74 with 21 points by Belov. However, in 1971, the Red Army team won the title back after beating Varese in Antwerp 67-53. Belov scored 24 points, but he also acted as a coach due to some problems for Gomelskiy at the Russian border.

B

In 1973, he played his last final with CSKA, of course against Varese, and lost in Liege 71-66 despite scoring 34 points.

Vladimir Stankovic

Three seconds in Munich, 1972 Sergei Belov was a player ahead of his time. He was a shooting guard, but also capable of playing point guard or small forward. Just like Dragan Kicanovic, Mirza Delibasic, Manuel Raga, Bob Morse, Walter Szczerbiak and other shooters from the era, they had to play without three-pointers, which were introduced by FIBA during the 1984-85 season. He was unstoppable in one-onone situations and after the dribble, you could count on an assist or a precise shot, many times with only one hand. He was also a great rebounder, but his best quality was his cold blood, his 100 percent concentration in crunch time. His teammates always looked for Belov for the last play or the last shot. He was a leader who transmitted security and confidence to the rest of the players and true fear to some rivals. He was a player respected by all, because of his qualities and his behavior. He was a true officer and gentleman. With the USSR he won 18 medals: Four Olympic medals (gold in 1972, bronze in 1968, 1976 and 1980); six in World Championships (two golds – 1967 and 1974 – three silvers and one bronze); eight at European Championships (four golds, two silvers and two bronzes). In total, he won seven gold medals, five silvers and six bronzes in the most important international competitions. His only Olympic gold was from Munich against the USA in what was a famous final because of the last three seconds were repeated under the orders of William Jones, then the secretary general of FIBA. In September 2007, Belov told me the story of the most famous three seconds in basketball history:

36

“Jones’s decision was totally fair and correct to me. See, when Doug Collins scored to put his team ahead, 50-49, there were three seconds left and the scoreboard showed 19:57. Ivan Edeshko put the ball into play and I was close to midcourt, the table was behind my back. I got the ball and right away, the horn from the table stopped the game. But it was not the end, there was a mistake because the clock showed 19:59. There was one second left, but we protested a lot because it was clearly a mistake. The time had to start running when I touched the ball and not when Edeshko threw it in. After what to us seemed a never-ending moment, Jones lifted his three fingers and said we had to repeat them. The rest is well known. This time Edeshko made a long pass to Sasha Belov, who faked between two Americans, who in turn jumped at the same time almost clashing one against the other, and he scored the basket that was worth a gold medal.”

Disappointment at home, 1980 If his most glorious moment was that 1972 gold at the Olympics in Munich, I am sure that his biggest disappointment was the Olympic Games played in Moscow in 1980. Playing at home, the USSR lost first to Italy in the group stage and later against Yugoslavia after overtime, and so missed the title game. Some days later, he received an offer that was, in fact, an order: “I got a call from the USSR Sports Minister, Sergei Pavlov, and he literally said, ‘From this moment, you are the USSR national team coach.’ And I rejected it on the spot. The minister insisted and he repeated his offer constantly. Gomelskiy found out about the issue and, through his connections, he made it that the KGB wouldn’t allow me to leave the country for several years... I was an officer in the Soviet army and it was easy to do that. Those were

37

the worst years of my life and now I can say that for five years I even feared for my life!” The darkest period in his life also coincided with the comeback from Brazil of a USSR emigrant, a friend of his. Sergei greeted him at home and this was a suspicious act for what he called “the usual services”. His problems lasted until 1988, when he returned to CSKA as coach. In 1990, he coached Italy and in 1993 he was back in Russia, where he became president of the Russian Federation until 2000. He was also the national team coach for the World Championships of Toronto in 1994 and Athens in 1998, where Russia won silver medals, and also for the 1997 EuroBasket in Barcelona, where it won the bronze. From 1999, Belov joined Sergei Kushchenko as general manager and

Sergei Belov

The darkest period in his life also coincided with the comeback from Brazil of a USSR emigrant, a friend of his. Sergei greeted him at home and this was a suspicious act for what he called “the usual services”. president, respectively, to build a great team in Perm, Ural Great. Their team broke the dominance of CSKA Moscow, won domestic titles and played the new EuroLeague in 2001-02 as the first Russian team in the competition. Belov lived in Perm until he passed away in 2013 at age 69. He never had doubts that he, as well as other talents of his generation like Kresimir Cosic, Drazen Dalipagic or Dragan Kicanovic, could have played and triumphed in the NBA, just like Arvydas Sabonis did, getting there at 31, or Pau Gasol, Tony Parker, Dirk Nowitzki, Vlade Divac and so many other Europeans who showed that good basketball and good players are not an American-only privilege.

101 101greats greatsof ofeuropean europeanbasketball basketball

B

Miki Berkowitz 39

E

very time that Maccabi Tel Aviv visits Pionir Arena in Belgrade, I remember April 7, 1977. That day, Maccabi and Mobilgirgi Varese played the final of the competition we now know as the EuroLeague, the first one I ever saw live. Two years earlier, Israel had been part of the EuroBasket played in Yugoslavia, but it didn’t make the final phase. To be honest, I don’t remember much about the five qualifying games, after which Israel finished seventh with an average of 20 points from Miki Berkowitz. But that club final in 1977 was a dramatic game decided in the last moments. With 7 seconds to go, and with a 78-77 lead for Maccabi, a doubtful call for traveling on Lou Silver allowed Varese a chance to win the game. But great defense by Maccabi managed to maintain that score and allowed the Israeli squad to lift its first European crown ever. That was the first time I saw Miki Berkowitz play. He was the great star of Maccabi. He was only 23 years old, but he was already known as one of the best European players. I remember his name from the under-18 EuroBasket played in Zadar in 1972, where a great Yugoslavia team (formed by Dragan Kicanovic, Mirza Delibasic, Dragan Todoric, Rajko Zizic and Zeljko Jerkov, among others) won the gold medal. However, the best scorer of that tourney was one Miki Berkowitz. Thanks to him, especially, Israel finished fourth. The stands at Pionir that night in 1977 were yellow and full of Maccabi fans despite the fact that Italy was