4 minute read

Connections

from Falastin Volume 5 Issue 1

by paccusa

Salma Shaka

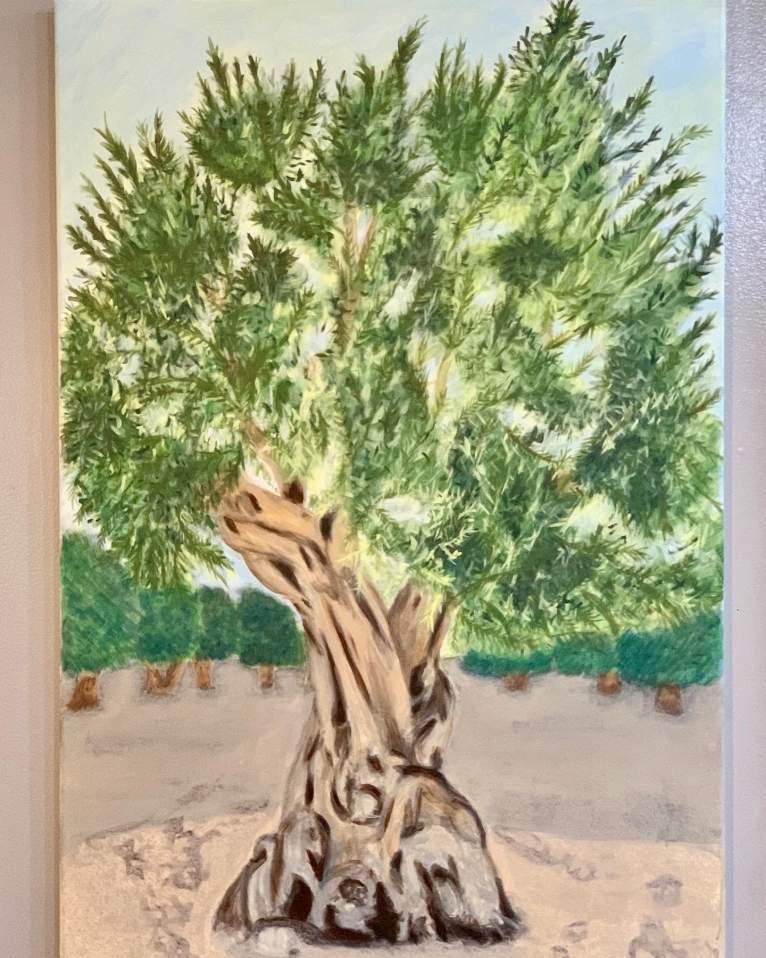

Jiddo’s (my grandfather’s) sealed Zaatar jar stood you like those trees?” my mom’s cousin asked. in a cupboard under the television; a safe space “There’s plenty more in Palestine, even prettier than which only he would allow access to: a commodity the ones in Amman,” she echoed from the driver’s enjoyed under his permission. In his household, Zaa- seat, and I anticipated the place everyone around me tar was divided into two: Zaatar from the supermar- has claimed to be my home. I had missed the desert, ket, and Zaatar from the the dirty beaches of Sharjah, homeland. The homeland, “Despite our differences, we still find and my mom’s family who back then a mystery, just like space for each other because Palestine still lived there. For an entire Jiddo’s numerous unspoken stories. The older he grew the more you could see in connects us through its anecdotes. We are the constantly-moving Palestiniyear, my Palestine was nothing but a dull place I had only wanted to leave, but the the way he paces himself an; building homes and seeking spac- things we take for granted how much he resembled Pal- es where memory would flourish, often expose themselves as estine. My Jiddo is my Palestine; the way he pressed olives and held onto his identipreventing it from dying out. Conserving, restoring, seeking connecbitter-sweet memories. Within a year of living there, ty no matter how much he tions. I had found the comfort of tried to hide it away in a adventure in Nablus’ old sealed jar in a cupboard under the television. Alt- souks and its mountains. I began to cherish the feelhough my Jiddo was never much of a talker, he al- ing of familiarity through the strangers who knew ways was and remains my association of home de- my family and remembering my Jiddo’s pharmacy spite going to live there as a kid myself. At the age of on or how pretty my mother was. In Palestine, I was 10, my parents decided to move us there from the grounded in the places my ancestors have left traces UAE. I remember staring at the trees through the car in: the old family house, the soap factory, the sofas window on our way to the Jordanian border. “Do my grandma once bought from Balata and refur-

bished now being used by my dad’s uncle and his family. Jiddo’s stories came to life in Palestine; I looked for Haj Fatfout, the small man who sold knafeh downtown, for birds he used to watch, and all the places he grew up in. It is true that one cannot step into the same river twice, a phrase my grandfather always used whenever he’d miss home, but it is also true that a place like Palestine barely ever changes despite all that it goes through, because almost 30 years later, here I was, reliving his memories and creating my own. For the 7 years that I have lived there, I felt most grounded in the connections I had with the people, the earth, and hidden corners. For the past 4 years since moving away, I often wonder whether I would love Palestine a little less, or a little more, every time I go back to it. I wonder whether my friends from school would still be there, whether the antique-shop owner I frequented would recognize my face, or whether our house would be gone.

I do not want to paint an unattainable picture of Palestine, something that memory often compels us to do. I have it, just like every place I have ever lived in. At times, Palestine was ka’ak and newspaper-wrapped salt; at others it was poverty and segregation, people wanting to leave to build better lives for themselves elsewhere.

The older I get, the more similar my and Jiddo’s stories become: two Palestinians in Europe seeking education, work opportunities, the entirety of life’s demands, hoping to one day return to find that nothing has changed. I connect to him, to my heritage, in numerous ways; recalling his memories and mine, listening to folklore on the bus, delving into photo albums, and most importantly seeking communities from the diaspora within the places I find myself in. Ever since moving to Europe I have been involved in numerous political and cultural spheres, from rallying in the streets to organizing virtual reading discussions. Through my activism, I had come to find that there are thousands of people like me and Jiddo, those who have left by choice, and those that have never had the privilege of going. Despite our differences, we still find space for each other because Palestine connects us through its anecdotes. We are the constantly-moving Palestinian; building homes and seeking spaces where memory would flourish, preventing it from dying out. Palestine is connection, and I want to allow more room for it in my conversations: the vulnerable, personal Palestine that has represented Zaatar way before it has ever represented anything else. Not the war, nor the uncertainty, not the betrayal nor the trauma, but the soft cheese and warm smile hiding under a grey mustache. I want to connect to Palestine by speaking of how beautiful she is, by writing, reading, drawing, dreaming about her, as we all should, to reclaim her memory. I want to set my Palestine free, unsealed,

always had a love-hate relationship with

unhidden in a jar in a cupboard under a television.

Artwork by Nisrin Shahin IG: @Nisrin.Shahin