5 minute read

Contextualizing Solidarity as Praxis

from Falastin Volume 5 Issue 1

by paccusa

Abire Sabbagh

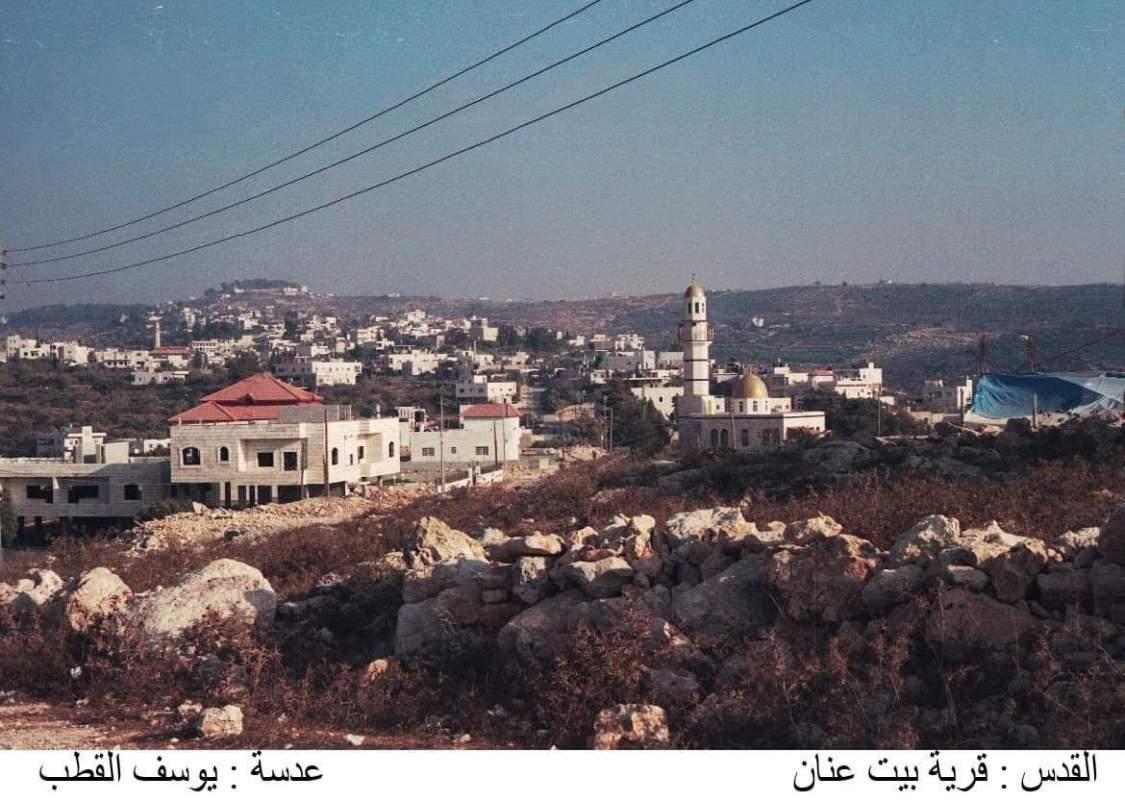

In his poem (we have on this land what makes life worth living) the beloved Palestinian poet, Mahmoud Darwish, reminds us of the beauty in the mundane, the things we take for granted whether it be the aroma of bread made freshly in the morning or the innocence behind one’s first love. He goes on to name the importance of the (mother)land that makes our lives not only worthwhile, but simply possible. Drawing from the decolonial, anti-patriarchal understanding of our land(s) as a nurturing, mothering, and feminine figure that resembles and symbolizes all that women give to and for our society at large, he refers to Palestine as the mother of all beginnings and ends. Darwish concludes with the necessary reminder that it is, in fact, because of and for the land of Palestine that we continue to live, to fight, and to carry on her legacy.

Darwish’s whole poem, and especially the six words of the title, have always struck something deeper within me and stayed with me in profound ways only art and poetry tied to political struggle can. The title has been my go-to desktop screen saver for the last eight years; whether on my personal laptop or work desktop screens. I carry it with me as both a literal and figurative grounding reminder of the work that needs to be done to dismantle what bell hooks termed “the imperialist capitalist white supremacist patriarchy.” I have always personally paired Darwish’s poem with what is known as the “Assata Chant:” Assata Shakur's powerful reminder that “it is our duty to fight for our freedom… we have nothing to lose but our chains.” Assata Shakur is a former member of the Black Liberation Army who was wrongfully accused of being an accomplice in a shoot-out on the New Jersey Turnpike in 1973, and was heavily targeted by the FBI counterintelligence program. She is now a political asylee in Cuba. Pairing the two always felt natural and organic, as if the two people behind the words were somehow in conversation with each other, whether they

knew it or not. This is how I’ve come to understand and define solidarity: historically oppressed communities thinking and working alongside each other as accomplices in struggle, imagining and fighting for the complete decolonization and liberation of all people and land.

My first exposures to solidarity in practice were the many anti-imperialism, anti-zionism, and antioccupation protests and marches that flooded the streets of San Francisco. I was a teenager then and had just come back from a summer cut short in Lebanon in 2006 when Israeli forces unsuccessfully tried to occupy Southern Lebanon. I was still trying to understand exactly what had happened upon my return - why my family spent a month in a shelter, why bombs were dropped, houses were destroyed, and why I passed by too many dead bodies on the streets, many clearly killed trying to escape or run away from something. I was questioning the privilege I had that allowed me to flee on a US military ship, as if a piece of paper that claimed citizenship to an artificially made and stolen border proved my life more worthy than people I share blood with. The chants that took over Market Street, poetic and profound in their own ways, are forever inscribed in my memory. More notable than the creative chants, however, was always the diversity of the thousands of people chanting together in unity -out of anger, frustration, hurt, and passion. San Francisco’s demographic itself is enough to ensure diverse groups of people. However, it was always clear that the intersectional, political messaging behind what a “Free, Free Palestine” means and looks like is what drew people from all identities to these spaces. There was a mutual, albeit unsaid, understanding that freeing and liberating Palestine cannot, will not, and should not happen unless all vulnerable and similarly oppressed people/land also achieve reparations and justice. The important focus on the political in such protest spaces inherently provides deeper, multilayered, and critical definitions of

terms such as solidarity, intersectionality, and “allyship” (as opposed to the growing mainstream definitions of such terms that have diluted and stained coalition building networks).

Through a politics of identity, we understand the larger systems and structures in place that make it our responsibility to work in solidarity with and for all oppressed communities, whether we "identify" with these groups or not. We do not co-opt movements or struggles, but we also do not feed into the western, institutional separation and pitting of identities against each other to dictate the work that needs to be done. That is to say, there are ways to be proud of our identities, to center them and those who are most vulnerable because of their identities, without feeding into narrow-minded and limiting categorizations of identity politics.

We can draw from what is taught, learned, and achieved in such sites of protest to dictate and transform the ways our cultural and community centers operate. There is great potential for these centers to become, what I like to call, alternate sites of knowledge production and dissemination. I identify the Palestinian American Community Center of New Jersey (PACC) as one of these sites.

Autonomous knowledge production is necessary to even begin imagining a free Palestine; before the possibility of freedom from settler-colonialism, militarism, state sanctioned violence, racism, white supremacy, patriarchy, and capitalism comes the (sometimes more difficult) internal education and work needed within our communities to strengthen ourselves and each other. This internal work requires a look inwards into the ways we are both affected and harmed by these dominant systems of oppression, as well as an evaluation of privilege(s) that allow us to benefit from these systems while other communities struggle against them. Here, I’m thinking specifically about the proximity to whiteness many Arabs cling onto, that inherently produces and feeds into the anti-Blackness and colorism in our community. We must also combat the intensified classism and patriarchy that colonialism stained our communities with and that continues to be upheld due to our engagement in western capitalism. We must complicate intersectionality and define it not simply for the ways we carry multiple identities that dictate how we navigate the world, but more critically understand the intersecting systems of oppression that marginalize and hurt multiple communities in similar ways, or for similar reasons. This intersectional and critical approach to advocacy, social justice, and community organizing is PACC’s cultural and political framework.

To have the ability and power to fight for the liberation of all, we must first be mobilized and inspired enough to work individually and collectively, to forge the bonds necessary to transgress the institutional and systemic, literal and figurative, socially constructed barriers and borders plaguing our society until today. We owe it to ourselves, our ancestors, and our future generations to begin paving the way for “a world where many worlds can fit” (as the Zapatistas have taught us).