EDITOR’S NOTE

Haley Esbeck, Co-Editor in Chief 2023-2024

noun.

ed·u·ca·tion: an enlightening experience

Education is arguably the most valuable thing that money can buy, yet that is not solely how its value is determined. It changes hearts and minds, teaches people how to envision others’ lives, transports imaginations to new places, and empowers students of all ages to take charge of not only their futures, but their present lives, too. The classroom is a portal, a time machine, a think tank, and full of endless possibilities. For students around the world, attending school is a gift—whether they realize it or not—and the worth they get out of it often depends on the work and dedication they put in.

In February of 2023, Global Vantage Co-Leaders Ainsley Cobb and Haley Esbeck, joined by Germaine Jackson, Head of Service Learning at Pacific Ridge School, embarked on a journey to visit Global Vantage’s partner school, the Kibera Girls Soccer Academy (KGSA) in Nairobi, Kenya. What shocked them most about Kibera (one of the world’s largest informal settlements in which the school is located) was not the chal-

PRS STAFF

Co-Editors in Chief

Ainsley Cobb ‘24

Haley Esbeck ‘24

Global Vantage Members

Sadie Stern ‘24

Kylie Martindale ‘24

Colt Muellen ‘24

Shiva Kabra ‘25

Dylan Smith ‘25

Kady Hawk ‘26

Abigail Qiu ‘26

Aleena Kim ‘26

Ashlyn Esbeck ‘26

Eva Kuhn ‘26

Ruby Dai ‘27

Karina Revenko ‘27

Faculty Advisors

Gabriela Nava-Carpizo (Global Vantage Group Advisor)

Germaine Jackson (Head of Service Learning)

Faculty Editors

Kieran Ridge (Journalism Teacher)

lenging conditions the residents endure or the unexpected support systems that result from it, but the way in which the students at the KGSA are genuinely so grateful for the opportunity to go to school. Coming from the bubble of Southern California, it was incredibly inspiring to meet girls our age that openly love and are passionate about school. This revitalizing experience made the theme for this year’s magazine issue extremely obvious, and we are so excited to share it with you.

As always, the Global Vantage Magazine is put together by a team of students, and is truly a learning experience for all that are involved. After departing from tradition with the look of last year’s magazine, Issue 16: Love (Not Hate), we decided to return to the aesthetic of the earlier Global Vantage issues by creating a new template and returning to a previous logo. We hope to set the standard for the next generation of Global Vantage leaders and members with this change.

We are also proud to announce a new partnership with the Harkness Institute in Nuevo Vallarta, whose students have shared intriguing and meaningful stories. Additionally, this issue features our returning partners and contributors from the KGSA, as well as CETYS Univesity in Tijuana, Mexico. You will of course find a variety of content from Pacific Ridge School (PRS) students and the people they have connected with or solicited articles from as well.

As you read through Issue 17: The Power of Education, we hope you can be transported into the lives of students and life-long learners around the world to experience education, and its impacts, from their point of view.

INTERNATIONAL PARTNERS

KGSA

Khadija Mohammed (Journalism Club Advisor)

Prudence Indeche

Salima Amisa Hussein

Mary Nagawa

Charity Nabwaya

Loreen Kasivwa

Sheryl Samantha

Sarah Mong’ote

Abigael Naeku Mailyi

Lonah Lombo

Brigid Anne

Grace Tabu

Mary Akinyi

Ann Sieku

Blessing Kaluhi

Faith Achieng

Siama Musa

Tabitha Paul

Ibrahim (Student from Baringo County)

CETYS

Edgar Ornelas (Journalism Club Advisor)

Lucía Beltrán

Luma Rodríguez

Juan Pablo Ricaño

Carlos Rivera

Leonardo Rodríguez

Alfredo González

Estefanía Hernández

Emilio Flores

HARKNESS INSTITUTE

Jonas Emiliano Delgado Sandoval (Journalism Club Student Leader)

Ania Cuevas Dorantes

María Fernanda Velasco Marchesin

Carla Andrea Castro Rosas

Natalia Ruiz León

Through the Lens: Kibera & Kenya, February 2023, by Ainsley Cobb Beyond the Traditional Classroom, A Collection by CETYS Contributors A Glimpse into Beyond by Aleena Kim

Exploring the Differences by Ashlyn Esbeck and Eva Kuhn Combining Skateboarding with Education by Kady Hawk

Impressed: Teaching Printmaking at the Oxbow School by Daniele Frazier Lessons from Across Borders by Colt Muellen and Sadie Stern Environmentally Inspired by Dylan Smith

How to Hear in the Middle of Nowhere by Cindy Mu

A Conversation with a Tea Scholar by Abigail Qui

The Need for Representation of Women in Athletic Research by Abigail Qui Kibera Girls Soccer Academy by Prudence Indeche Baringo County, Kenya by Ibrahim Cancer as a Chronic Disease by Salima Amisa Hussein Water in Kibera by Mary Nagawa

POEMS, SHORT STORIES,

What We Can Achieve and What We Can Offer by Charity Nabwaya Inspiration, Motivation, Fun, and Other Quotes from KGSA Students Labrinth Within by Ania Cuevas Dorantes

To Leave a Mark by María Fernanda Velasco Marchesin Corazón de Poeta (Poet’s Heart) by Carla Andrea Castro Rosas The Stairwell by Natalia Luís León Japanese Cay by Natalia Luís León

Through the Lens: Kibera & Kenya Ainsley

Cobb

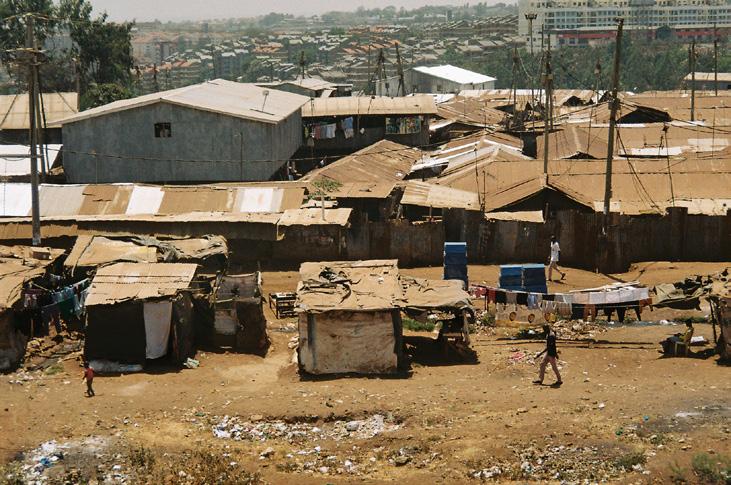

In February of 2023, following the release of Issue 16 of Global Vantage Magazine, titled “Love (Not Hate),” Haley Esbeck (‘24) and I, as co-Editors in Chief of Global Vantage, visited the Kibera Girls’ Soccer Academy (KGSA) to collaborate face to face. Our time in Kenya was characterized by profound connections, meaningful collaboration, and the mutual exchange of knowledge and experiences. The desire to convey the indelible impact that each experience imprinted on us led me to keep my 35-millimeter film camera in hand at all times, capturing the moments that seemed to transcend the limitations of words. These moments have been embedded into this story, intended to be shared indefinitely.

From Adversity to Triumph: Narratives of Empowerment at KGSA

Kibera Girls Soccer Academy started as a small community-based organization called Girls Soccer in Kibera (GSK), whose major goal was to stem the stark gender inequalities that are clearly evident in Kibera, the largest informal urban settlement in Africa and one of the five largest in the entire world, according to Habitat for Humanity.1 Kibera, like many other informal settlements around the world, has been labeled an “illegal settlement” by the government, resulting in all formal recognition of Kibera being stripped away. The government has absolved itself of any responsibility for the civic care of the 700,000 people whose home is in Kibera.

Kibera is a place where strength and resilience are born out of hardship, and where the women who call it home stand tall in the face of adversity. Among them is a beacon of hope and inspiration to all who know her, Dalifa Hassan. Dalifa grew up in the western part of Kenya, in a town called Busia, and graduated from Kibera Girls Soccer Academy in 2012. She has since received a Bachelor’s Degree in Education Science from Maseno University, then returned to KGSA as a Mathematics and Chemistry teacher, in order to continue KGSA’s mission of empowering girls through education.

1 “The World’s Largest Slums: Dharavi, Kibera, Khayelitsha & Neza,” Habitat for Humanity Great Britain, December 2017, accessed May 28, 2024, https://www.habitatforhumanity.org.uk/blog/2017/12/the-worlds-largest-slumsdharavi-kibera-khayelitsha-neza/.

joy

In the photograph below, Dalifa hugs a current KGSA student who stands in the same place as Dalifa did eleven years ago. In a moment that captures the essence of hope and triumph over adversity, Dalifa and her student stand out amidst the joyous celebration of KGSA’s first dormitory opening, their embrace serving as a beacon of light in a sea of jubilant faces.

“Living life without hope is like living in a hole without anything that is of importance. Girls and boys in Kibera are living without hope in their

lives. It is a routine because most have experienced problems—they are forced to get pregnant early and are also expected to get married at times,” KGSA student Rachel writes.

As KGSA’s first dormitory opens its doors, it provides a much-needed sanctuary for a hundred girls who have been facing the typical constraints of living in Kibera. For these girls, the dormitory represents a chance to break free from the dangers and uncertainties of life outside the school. The dormitory is a place where they can pursue their dreams with renewed vigor and determination, surrounded by safety, security, and unwavering support.

As the celebrations unfold around them, Dalifa and her student share a moment of quiet reflection. They are filled with gratitude for the opportunities that await them, as well as the determination to face whatever challenges the future may hold with courage and resilience. Meanwhile, another KGSA student, Faith, who is in Form 2 (the equivalent of Grade 10 in the U.S.), waves to my camera, surrounded by smiling peers and close friends.

Among the crowd of celebrating KGSA students at the dormitory festivities, a voice echoes above the commotion. “If you have time, come see the new books that we received in the library! I’m so excited, I can’t believe it!”

Naima, a 2016 graduate of KGSA, studied coding at the Moringa School and gained a degree in Graphic Design from AkiraChix before joining the KGSA staff as a librarian in 2022. Bringing her unique skill and knowledge to support both the students and the school in its entirety, she holds an immense passion for illuminating young minds through the pages of books—and is full of joy to have received two new additions to the KGSA’s still-growing library, the memoirs of Michelle Obama and Barack Obama, the former U.S. president whose father was born in Kenya. Driven by her vision of KGSA’s wooden library shelves packed with books, Naima aspires to curate a diverse collection of books and short stories from not only local Kenyan authors, but also international authors with varying experiences, backgrounds and perspectives.

Foundations of Resilience: Homes and Community Structures in Kibera

Theaverage home in Kibera is generally constructed with mud walls, layered with concrete, a tin roof, and an earth or concrete floor. The average cost of a home is around 700 shillings per month—or ten U.S. dollars—with eight or more people living in it at once. “It is small, but we like it that way,” Miriam, a student at the Kibera Girls Soccer Academy, firmly states as we sit inside her home, accompanied by her mother. Although Miriam does not reside at home during the school year—due to the fact that she boards at KGSA’s newly constructed dormitory—this home is everything to her. The crooked family photos and the garlands that adorn the mud walls reflect her life here. While adjusting to Merriam’s absence has been difficult for her mother, she chooses to cope with the situation. With Merriam in the dormitory, her mother doesn’t need to fear for her child’s safety.

As we exit Miriam’s home—accompanied by roosters and her pet kitten named Nelson Mandela—Blessing, a fellow KGSA student, stands in the walkway awaiting the ideal moment to capture an image of Merriam and her mother. She utilizes a camera from Kibera Girls Soccer

Academy’s journalism club, the Shedders. The Shedders—so named because they shed light on the untold stories of their community—serve as a means of empowerment for the girls at Kibera Girls’ Soccer Academy, giving them a voice and a platform to express themselves. Through their work, they show the world the resilience and strength of the people of Kibera, who face significant challenges, but who also possess a deep sense of community and hope for a better future.

Housed within a building constructed for the purpose of stemming the stark gender inequalities and educational disparities evident in Kibera, the Shedders Journalism Club meets to strengthen the voices of not only their community but one another. Beneath the soft glow of streamers reading “Journalism Club,” a circle of students fills the room with their voices declaring, “My dream is to be a journalist,” and “I want to be one of the many people in this world pushing for change.” These students are our colleagues in Global Vantage—collaborating together to see the fruition of print publications uniting our voices despite the 9,671-mile gap that physically separates us.

The primary caretaker of children in Kibera is most commonly a female figure, making single fathers a rare occurrence. Blessing’s father— the exception to these demographics—has been present in her life since the day of her birth. He takes great pride in coaching women’s soccer teams, as he sees much promise in the talent of female soccer players in Kenya. For the past twenty years, he has coached women’s soccer teams from youth to pre-professional, including Blessing’s first soccer team. Although Blessing now plays on KGSA’s soccer team, she still takes time between studying to work on honing her soccer skills through the coaching of her father. The two spend their weekends watching television shows in their home, accompanied by posters of respected female soccer players pasted on the surrounding walls.

Global Vantage seeks to ensure that journalism continues to be a catalyst for youth empowerment in Kibera, contributing to the trajectory-changing influence that the opportunity to become involved with publications holds. Through direct collaboration facilitated by meetings, workshops, and intimate conversations, Global Vantage and the KGSA Shedders delved into the importance of student publications having a presence in communities such as Kibera. The two groups of students, alumni and faculty advisors—from Pacific Ridge School and KGSA— created an environment where together we learned about journalism, the creation of print publications, photography and how to adequately

share the untold experiences of individuals.

During the profound moments of building connections through open conversations, one student conveyed the message,

“We just want to be seen.”

In a world rife with systemic inequalities and underrepresentation, where opportunities to have one’s presence acknowledged are scarce, each story written on a single strand of stable internet cable becomes a matter of representation. As each photograph holds the potential to shatter stereotypes and empower voices that have long been silenced, it is essential that the stories behind them are accurately represented. With each moment in time that passes through the lens of a camera or the publishing room of our student magazine, we strive to capture the unseen and the overlooked, unveiling the beauty that resides within the shared human experience, seeing as it holds the potential to bridge societal gaps. Guided by the simple words, “We just want to be seen,” Global Vantage Magazine is propelled to break barriers, evoke empathy, and ignite social change.

Kenya’s Soul: Unveiling Stories Beyond Kibera

In the midst of Global Vantage’s 2023 trip to Kenya, we had the privilege of exploring other parts of the country, facilitated by our KGSA hosts.

As depicted here, a Kazuri bead-maker crafts beauty in Nairobi. In 1975, a small workshop in Nairobi began experimenting with handcrafted ceramic beads. They named their venture Kazuri, which translates to “small and beautiful” in Swahili.2 Recognizing the great need for stable employment and empowerment among women in the villages surrounding Nairobi, the founders, both single mothers, made it their mission to create an enterprise that would provide exactly that. They aimed to uplift and enable women who were struggling to find opportunities to support themselves and their families. Through years of dedication and hard work, Kazuri has grown tremendously. Today, it has a workforce of over 340 skilled women who create stunning ceramic beads and unique pottery. Each bead and piece of pottery is handmade and hand-painted in rich, vibrant colors that reflect the spirit and culture of Kenya.

2 “Swahili language,” in Encyclopædia Britannica, accessed May 28, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/topic/Swahili-language.

Students and faculty from KGSA and Pacific Ridge School were also able to visit the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust on a KGSA school field trip. Wildlife, ranging from the African savanna elephant to wildebeests, find refuge in Kenya’s preserves and national parks—and the Sheldrick Wildlife Trust operates one of the most successful orphan elephant rescue and rehabilitation programs in the world. The trust offers orphaned elephants—and additional wildlife such as warthogs and yellow baboons—a safe haven to heal and work towards being reintegrated into the wild. For many of us, this was our first opportunity to see an African savanna elephant face to face. The fencing along the elephant’s habitat was engulfed in smiles, as students reached out to touch the dust-covered skin of the elephants.

Final Words of Hope: Asha Jaffar’s Perspective on Shaping Kibera’s Narrative

For the final words of this story, I want to turn to Asha Jaffar, who is a graduate of the Kibera Girls Soccer Academy.3 She was president of the Journalism Club (KGSA Shedders), Head Girl, top of her class, and president of the Student Board, then later graduated from Moi University and became a professional journalist and a social policy advocate. She is witty, courageous and speaks her mind passionately and fluently in three languages—Swahili, Nuba, and English. She has worked with international media like Der Spiegel, The Guardian, and the BBC, along with publications and non-profits in Kenya, such as Action Aid.

Asha continues to work diligently to be an effective journalist who tells her story and the stories of young women in Kibera, while also correcting the misrepresentation of Kibera in online and international news platforms. I am including her perspective in this article to provide balance, depth and “an inside view” from Kibera and KGSA. Asha’s words undo stereotypes and look forward to a future of hope and change for KGSA, Kibera, and Kenya.

“The power of words—the keyword is words. Whatever I read might influence my life in either a positive or negative way. Not only me, but also anyone. Over the past years I have always had the habit of surfing the internet, reading articles people write about Kibera. Every time I clicked to read an article I was awestruck, time in and time out, not at the creativity of these writers, but at their misinformation, lack of love and negative energy. I was always baffled by the amount of misinformation out there. ‘Kibera is dangerous.’ ‘Kibera is full of goons and dependents.’ Kibera this, Kibera that. All people ever report about is the negative part of Kibera, and my question always remains: ‘Why not Kibera, a breeding site

3 Asha Jaffar, Documentaries.org, accessed May 28, 2024, https://www.documentaries.org/filmmakers/asha-jaffar/.

The Giraffe Center operates with the purpose of educating Kenyan school children and youth about their country’s wildlife and environment, as well as providing local and international visitors an opportunity to come in close contact with the world’s tallest animal species. On a field trip to the center, we were able to feed the Rothschild giraffes and gain a deeper understanding of the vital protection efforts in and beyond Kenya.

Nairobi National Park conserves and manages Kenya’s wildlife for the benefit of nature and humanity. On the wide open grasslands of Nairobi National Park, the horizon is shared by the skyscrapers of Nairobi and the skyscrapers of nature—giraffes. We embarked on a sunrise safari to view the plethora of diverse wildlife species that the national park hosts, including the rhinos in the photograph below.

for talented, witty, and hardworking individuals?’ No, this would not bring donors in. Donors want the negative stories, right? So that’s what people give them.

‘The fact is, if you want to know about Kibera, why don’t you book a flight to Nairobi and pay us a visit? Trying to influence young lives with sad stories about Kibera—your writing might give hope to someone or destroy someone, so why not choose to inspire that kid in Kibera who

thinks he wants to be the next footballer, writer or artist? I am a writer, and my main aim in life is telling stories, and trying to create a picture for people, and that is what I love to do. Telling people that Kibera is full of talent and not AIDS and poverty. Positive stories, ladies and gentlemen—give hope. And hope lives longer than donors.

‘One of my favorite quotes by Bruce Barton says it all: ‘Nothing splendid has ever been achieved

except by those who dared to believe that something inside them was superior to circumstance.’ You walk around Kibera, and you meet people with the most infectious smiles. Positive people. Even though we might not have a lot, we are working on it. Soon, with a lot of people speaking out—not donors, but themselves—we will have a better place. A safe Kibera.

‘Someone once said that if you want to help the people in the slums, then you have to let them do the job themselves. No amount of donors and no amount of international pressure can change Kibera. It is the people living in it. I always say no one will come from another place and make your house the way you want it to be. People have their own choices and preferences. And those people are here in Kibera. We want change, but we do not want people writing negative things about Kibera. If you want to help change Kibera, if you want to make that three-year-old kid in Kibera have hope and believe he can be whatever he wants to be, then let them read positive stories. Success stories. Not poverty articles, with faces of ‘poverty-stricken children,’ but positive stories with happy and hopeful faces.”

Rose is the student feeding the giraffe.

Rose is the student feeding the giraffe.

“Rose and I had an instant connection. On my first day at the school, she introduced herself and pulled me out of my group to give me a personal tour of the newly built dormitories. Her confidence and aura of happiness are what struck me first. She talked to me, a stranger from a different corner of the world, with a warmth and openness that I have seldom experienced. Rose told me about what it was like to grow up in Kibera, and about her family. She was incredibly grateful for the opportunity of education, and I could sense her determination to make the most of it. Since the trip, I have kept in contact with her. We occasionally send pictures and check up on each other. Rose has graduated from KGSA and is currently pursuing a degree in mechanical engineering. I have no doubt she will do great things, bringing up herself, and her community along the way. She is truly an inspiration.”

—Alden HarrisBeyond the Traditional Classroom

Three Aspects that Shape the Educational Experience at CETYS Tijuana

Edgar OrnelasHello! My name is Edgar Ornelas and I am a teacher at CETYS Universidad, a high school and university campus located in Tijuana, Mexico, also known as the corner of Latin America. Along with the people from Southern California, we live in a unique border region, a melting pot of cultures, ideas, and experiences that shape our everyday lives.

The article you are about to read is the product of a collaborative effort between me and some of my high school students. When tackled with the assignment of writing about their educational ex-

periences, the students decided to focus on three aspects that have proved to be essential to their development and learning experience: 1) service learning/community outreach, 2) technology, and 3) after-school programs.

As you will learn through my students’ experiences, these three elements are an integral part of their school program and they work with or through them every week. I am very pleased to share their thoughts with the world and hope that you find them as inspiring as I did. Enjoy!

“Education is the key that unlocks the golden door to freedom.”

–George Washington Carver

How Service Learning Has Shaped our High School Years

Students getting involved in their educational community is essential for a variety of reasons, mostly because being involved in the community facilitates the application of knowledge acquired in the classroom. Engaging with a community fosters discipline when facing a problem, it helps us to develop an outstanding perspective to understand our surroundings, and it opens unknown doors that will guide us through life.

In our opinion, education is not preparation for life in itself. Instead, it aims to empower students with a gift; education is our most powerful tool to change the world. The real purpose of education is to nurture growth in our minds and to help us feel connected to the world.

Getting involved with the community helps us feel confident about facing the challenges in the world; there are no obstacles that can limit our learning when working with a community. We are all growing alongside each other, everyone with a different mentality, destiny, and

strengths. But in this diversity we find richness; we have learned the value of sharing our experiences and have developed fond memories that will accompany us when we part ways.

Venturing out into different communities gives us a new perspective on how to see the world, it feels like a new universe of opportunities to experience. Having these experiences has helped us have a richer experience in high school. Community engagement empowers, it gives us a say over how we want to impact the world and nobody can take that away from us. This is why students should involve themselves in their communities: to learn, inform, educate, reflect, and, most importantly, to connect.

Lucía Beltran was

in Tijuana, Baja

and

in Tecate. She loves soccer, football, art, and coffee. She is particularly fascinated by American football and flag football, and dedicated four years to soccer, which taught her valuable lessons in teamwork and perseverance. After an injury stopped her form pursuing soccer, she discovered the calming and therapeutic nature of art.

How Technology Helped Us Through the Pandemic and Beyond

Juan Pablo Ricaño, Carlos Rivera, and Leonardo RodríguezThe pandemic has changed many things about our day-to-day lives, from the way we interact with each other to our topic: education.

When the pandemic occurred, there was a sudden need for online tools for education. While these tools were available in the past, there was never such an urgency to refine and upgrade them until COVID-19.

An example of a tool like this is Blackboard, an application we use at CETYS, which allows teachers to keep in contact with students by sending reminders of activities or materials needed, as well as allowing students to send activities or view course information from the comfort of their own home. Today even if we are no longer

in a pandemic, these tools are still used and are an everyday part of our educational journey. We now submit most of our assignments online.

Another good example of such a tool is online meetings. During the pandemic, online meetings helped bring a solution to our lack of face-to-face interaction. Tools such as Skype, Zoom, and Google Meet gained a lot of relevance because of this phenomenon. Again, today, these tools are still useful in our daily lives. They allow us to not miss classes during rainy days or to attend workshops that are delivered from another part of the world. Something that a few years ago seemed so far away!

These online tools have opened the gate for new

ways of communicating and learning. They were particularly useful at a time when we were forced to stay at home. With these difficult times behind us, we have gained some useful tools to help us on our education journey.

Juan Pablo Ricaño (JP) is a 17-year-old from San Diego living in Tijuana. He is interested in computers and technology.

Carlos Emilio Rivera is a 16-year-old from Tijuana who constantly betters himself by improving his abilities through dedication and hard work. He has a great interest in topics that include technology and the functioning of mechanisms.

How Practicing Sports Helps Me to be a Better Student

Participating

in sports during my high school years has certainly contributed in a big way to my educational process. The sense of being part of a sports team provides me with a valuable break from academic pressures and contributes to my personal growth, sense of identity, and community.

Playing sports has been a great way to get rid of stress and to remain active, but more importantly, it’s given me the opportunity to be a part of a team that has taught me about the value of cooperation, determination, and perseverance. This sense of unity and collective actions towards a common goal was incredibly empowering. Even if sometimes it just seemed like arduous practices or team-building activities, the experiences shared with my teammates created lasting memories and friendships, that I will never wish to forget.

Also, the discipline and time management skills I developed through sports had a positive impact on my academic performance. The mix of training, games, and classes taught me how to prioritize and manage my time very effectively. The lessons that I learned in the field converted me into a responsible and more focused person.

All in all, after-school programs, such as sports, have played a crucial role in my journey through high school. They make my time more enjoyable and exciting, and they provide me with the opportunity to grow in a healthy, balanced way.

Alfredo González

After School Programs Helped Us Discover Our Passion for Musical Theater and Community Outreach

Hi! My name is Estefanía Hernádez. Musical theater has become a natural part of my routine. It’s something that always keeps me excited; just the idea that I have something that I love already on my schedule. Even after coming home from school completely exhausted, it takes just 5 minutes into a new choreography to completely change my mood for the better. It provides satisfaction, it’s a challenge, it’s strategy. Being able to see results after each rehearsal keeps me motivated to keep going. For me, it’s not just singing or dancing or acting, it’s pushing my boundaries, and it’s proving myself every time.

For me, musical theater is not just a hobby, it’s something I want to pursue as a career. Just by practicing every day, I feel like I have been training for college and my future. What once started as a simple hobby, has turned into what I want to do as a career. In this way, after-school activities can help us discover hidden talents or passions that we may want to follow later in life.

Hello! I am Emilio Flores and I have recently started working with the Interact Club, a branch of Rotary International that allows high school students like me to make an impact in our community through diverse activities. Being able to make even the smallest impact on a specific cause brings a type of joy and satisfaction that can’t be obtained otherwise. It’s a way to realize the power we have to make a change just by bringing forces together with other like-minded students.

In the end, we’ve learned that feeling like family, in both Interact Club and Musical Theater, has made our high school years so much better. They create a safe space to make the changes and decisions to shape our future.

Estefania Hernandez is 16 years old was born and raised in Tijuana, Baja California. She has always been passionate about visual and performing art, from musical theater to painting to writing. She also enjoys sports and fitness, and just recently became a Certified Personal Trainer.

Emilio Flores García is 17 years old and was born in San Diego, California. He is currently studying in the International Baccalaureate (IB) program at CETYS University. He is committed to his community and looking to make an impact locally and internationally; his goal is to attend university in the United States to study engineering.

Alfredo González is a 17-year-old high school student interested in physics and world history. He enjoys being able to get together with friends and enjoy simple things like playing basketball, watching movies, or just hanging out.

A Glimpse into Beyond: The Daily Life of a South Korean Student Aleena

From the moment she wakes up, she can hear the cicadas ringing and the bustling city sounds of buses and people. Living in the heart of Seoul, 손희승 (Son Hee-seung), or “Kaylee,” lives the life of a typical high school student.

At 7:00 am, she slowly makes her way to the dining table where her mom has laid out seolleongtang, a stew made of Ox bone, kimchi, seaweed, panchan, and a traditional staple in a Korean household: rice. After finishing her meal, she dresses in a clean, pressed uniform and finishes the rest of her morning routine. At around 7:50 am, she is expected to have her bag packed and ready to start the day.

Outside, she sees the city bus coming her way. While it is common for students in America to be picked up by a bright yellow school bus, Korean students often use public transportation. Kaylee typically rides the bus for fifteen minutes with some of her school mates.

In her all-girl Christian public school, students are not allowed to have exotic hair colors, paint their nails, or wear makeup. The campus consists of three buildings on a beautiful campus built in 1887. A typical Korean high school class has thirty students, packed into a relatively small space.

Students spend their entire day in a single classroom, with subject-specialized teachers visiting them in turn. First period, the class president stands and students are expected to formally bow to their homeroom teacher.

Her second period arts, culinary, and crafts teacher arrives. These classes specialize in teaching students the importance of necessary life skills,

Kimlike cooking, sewing, basic plumbing, paying taxes and finances. Kaylee claims she has learned many basic things, but her most memorable time was when she got to sew a pouch into a wallet.

After the first few classes of the day, students can use their monthly allowance to get a quick, affordable snack from the street corner. These vendors usually sell popcorn chicken, ice cream, and tteokbokki (a dish with rice cakes, spices, and broth.)

After returning to campus, students finally enter the lunchroom at 11:30 am. Students are provided with a meal of rice, doenjang jjigae (soybean paste soup), panchan, spinach, kimchi, vegetables, and a sweet treat. Schools use metal plates, trays, and utensils to eliminate large amounts of waste. Food is made and served by students based on a rotating schedule between classes.

In the last hour of school, Kaylee meets back with her homeroom teacher and they all say their formal goodbyes. The teacher assigns students to clean the classrooms and hallways. Kaylee cleans on Thursdays with her homeroom classmates.

From 5:00 to 10:00 pm, she has to catch the next bus to go to her English academy, twenty minutes away from her school. These English academies are usually taught by foreign teachers ranging from the United States to all over the globe. While these academies are not mandatory, every student still makes English and other studies a priority because of competition over slots at Korean colleges.

At 10:00 pm, Kaylee and her friends head to the local convenience store to take home ramen and

soda. She rarely has any time to talk with her friends at this time, as she proceeds to quickly run back home to finish her homework. When she does have time, she is able to walk with friends because of Korea’s safe environment. Older students often return from school as late as 1:00 am!

At home, Kaylee finishes the rest of her homework and Bible study, completes her nightly routine, and takes a quick stroll through social media before falling asleep at midnight. By the end of her day, she has done at least ten hours of studying.

Kaylee’s story shows the differences in the cultural and educational systems between Korea and the US. Although Korea is not perfect in terms of its academic effect on a student’s individual growth and identity, as there are specific norms expected of them, they are able to hold strong connections with their culture and learn important life skills, responsibilities, and behavior.

On the other hand, American schools leave room for students to express themselves and have a variety of different talents and passions.

In my experience, the education in America is also more adaptable to each student’s preferences, but is only ranked 28th in math of the 37 participating countries, showing the struggles America has with basic arithmetic (Mervosh).

We all live in the same globe and are interconnected, but we still manage to live very different lives. The different perspectives enlighten students on how different the maturing process is for someone their age.

Exploring the Differences between Religious and Secular Schools in Southern California

Ashlyn Esbeck and Eva KuhnAgood education could be defined as instilling the drive for lifetime learning, fostering curiosity, and creating a community where students feel they can dialogue freely and share their ideas. Each school has their own distinct approach to teaching, as well as different mission statements that allow each school to excel in its own way. The question we wanted to explore is, what are the differences between private, public, and religious schools, and what advantages do they each have in providing a “good” education when compared to one another?

We had the opportunity to interview two incredible teachers who have taught in various areas. Ms. LeeAnn Mott started her teaching journey at Smithfield Public Elementary School in Smithfield, Virginia. She then moved to St. James Academy in Solana Beach, California, the Catholic school she has been teaching at for the past twenty-eight years.

The second teacher we interviewed was Ms. Jennifer Fenner who currently works at Pacific Ridge School, a private, secular high school in Carlsbad, California. Before that she worked at the Catholic school Mater Dei High School in Orange County, California.

One aspect that both teachers talked about was the significance of small class sizes. At religious schools, small classes are common, as they create a tight-knit community. Ms. Mott noted, “There’s negatives to small class sizes because you know people too well, but the positive is… people feel like they are noticed and valued.” Despite this, the closeness can cause arguments amongst the students, as they are forced to interact more often. Whereas in larger classes, teachers can separate students easier in case of conflict due to the number of students.

Ms. Mott makes the point that with the larger class sizes there is more collaboration in the classroom because there are more students to participate; however, bigger class sizes can also prevent students’ individual voices from being heard and

causing students to get lost in the chaos. Since there are so many students in a class, individual attention and adaptation to individual learning capabilities is often difficult, especially if class periods are short. Due to these circumstances Ms. Mott observed: “At that school the kids would get held back, so I had seventh graders that were fifteen years old . . . some of the kids I felt like were just waiting to drop out.” Students may lack motivation when their teachers do not have sufficient time and resources to dedicate to their learning, leading them to fall behind in school.

In religious schools it’s often thought that because of the aligning beliefs, it’s easier to get to know people, as you always have aspects of your faith identity. “Initially it’s the religious part that brings maybe seventy five percent of the people together . . . many students here aren’t active Catholics and they . . . think of religion as more of a history class.” Alternatively, at public schools, kids have more options when exploring where they want to belong because there is a more diverse student body. This also heightens opportunities for school spirit, large athletics programs and expansive extracurricular options, which creates a greater sense of involvement and community amongst the students.

Even if the school is just Kindergarten through eighth grade, the community at religious schools continues to expand past graduation when people come back to celebrate religious events, such as the Sacraments and Mass. Ms. Mott has personally experienced this saying, “This is the place I got married, had kids, my mother died when I worked here, so they really embrace you when you have these pivotal moments.” The community and connection created in religious schools seems to be a large motivator for wanting to work there, causing teachers to have a deep devotion to the school and its students.

Though belonging to a community like this is enriching, a critical issue raised by both teachers is the pay disparity and how that affects the quality of education that the faculty and support staff

are able to provide. Teachers at religious schools often have much lower salaries, rooted in the belief that they work for “the glory of God,” as Ms. Mott expressed, which leads to the acceptance of a lower salary, affecting teacher motivation and the resources available to students. Teachers at religious schools also have more responsibilities added to their plate, whereas at a secular school teachers are typically given a specific course load at the beginning of the year.

Ms. Fenner focuses on a different set of expectations for teachers at religious schools, saying “There’s different rules for religious schools: if you are someone who doesn’t live the lifestyle that is outlined and expected of you, you are subject to being let go or fired.” There is an emphasis on adhering to the faith values and expectations, even when outside of school. She says that because of these sometimes controversial standards, there is less job security and more teacher turnover. Religious schools often hire teachers whose beliefs align with the school, decreasing the total pool size of available teachers and making it difficult to find the necessary teaching competencies.

Through these educators’ experiences, it becomes evident that the “good” education a school can offer depends heavily on individual student needs and family values. However, these interviews only explore two perspectives, and are not enough to truly understand the whole picture. The ultimate goal of a quality education remains the same: to provide an enriching, supportive educational experience that prepares students for the world beyond the classroom.

Photos courtesy of Christine Lang, Principal at St. James Academy

Photos courtesy of Christine Lang, Principal at St. James Academy

Combining Skateboarding with Education

Kady Hawk

The intersection of education and sports is an incredibly powerful way to change the world. Many educational programs in lower-income areas provide some sort of sport and schooling. For example, our partner, the Kibera Girls Soccer Academy, uses soccer as a gateway to young girls’ education. But how are sports and education connected?

Similar to our partner KGSA, Skateistan is a non-profit organization that provides education and empowerment to young minds through skateboarding. They work in Afghanistan, Cambodia, and South Africa. Skateistan was founded in 2009 by Oliver Percovich and now has more than 3,000 participants per week globally.

In an interview with the Chief Executive Officer of Skateistan, Oliver Percovich, we explore the importance of education, sports, and improving our global community.

Education is essential for all young minds; as Percovich said, “Education is . . . the starting point for navigating life and making good choices.” Education has a transformative power over societies, especially those in poverty. It is a building block to equip individuals with new perspectives, knowledge, critical thinking skills, passions, and so much more. It can prepare students for life’s challenges and aid them in finding a pursuit they enjoy, so it must become accessible to young minds.

How do sports relate to education? The opportunity to access knowledge through a community of athletes, with a sport that can bring them all together, can inspire more outreach to new students. Not only does it provide this opportunity, but it also assists them in learning through teaching perseverance.

“Learning is actually hard. Every time you’re learning something, you’re creating new pathways in your brain, essentially. That actually takes a lot of energy and is really difficult to do, and by learning persistence through taking part in sports or doing an activity (like skateboarding) you learn how to overcome that difficulty that you may also have with learning.”

Education is a pivotal pathway for children everywhere. Specifically, education is a powerful resource for low-income children to break the cycle of poverty and change their society forever. However, to break the cycle of poverty, inadequate education is an issue that must be resolved first. Percovich notes, “The hardest thing is breaking out of a cycle where there hasn’t been education.” These children are stuck in a society where they cannot have the gateway to a successful life and change their world because of the motion they are already in. Breaking that cycle is hard, but Skateistan has offered the solution of skateboarding as a gateway, through which it

builds community and empowers learning.

The current situation for education around the world is constantly improving. However, there is still change that needs to be made. Percovich stated, “About 4 out of 10 girls finished primary school 15 years ago. Now, 9 out of 10 girls finish primary school, so we’ve actually come a long way, but that 1 out of 10 is still an enormous number.” It is heartbreaking to think about children who don’t have the ability or access to education. A lack of primary school limits young girls’ opportunities and violates their potential for greatness. Our societies must eliminate poverty and disparity through education and opportunities for younger generations because they represent our future.

What we can do as students and those who have the privilege of easily accessible education is to make connections. Percovich claimed that having a role model or even just an influence can change someone’s mindset, and once again give them motivation to persevere past their difficulties. As he shared at his programs, Percovich observed, “That then helped them because there was peerto-peer learning; they were learning from other children their age that looked up to them...

...Don’t be scared to reach out and make friends with someone from another part of the world. We’re all more similar to each other than we realize.”

All around the world, children deserve the same possibilities. Organizations like Skateistan are providing these possibilities to children everywhere through skating. However, we still face many children who need access to it. We need to come together as a community and fix the more significant issues in our world, and from there, we can focus on smaller ones.

For more information, visit skateistan.org. To read more about the KGSA, see page 4.

Impressed: Teaching Printmaking at the Oxbow School

Thedistinctions between public art and outdoor art are, themselves, the themes that underpin my art practice: access, ownership, and permanence. These three topics raise pertinent questions regarding both public space and art. Who has access to outdoor space? Who has access to art? What factors render places or artworks inaccessible? Who owns the land on which the art is displayed? And in the case of public art, who owns the art? Does permanence in public art hold significance, considering outdoor objects are subject to the elements?

A prevalent misconception about creating public art is that it’s an altruistic gesture, a gift to the people. On the contrary, my creation of thus-far twelve distinct public artworks serves as a means to explore my own questions. In the challenging landscape of New York City, where public greenspaces fall under the jurisdiction of the NYC Parks Department, creating public art becomes an uphill battle. The creation, installation, and insurance of public artworks lack city subsidies. Navigating bureaucratic hurdles, alongside addressing the financial aspects, has taught me that the public art process is inherently interdisciplinary.

Daniele FrazierLearning to raise funds and engaging with municipal systems at a local level has reshaped my perception of how value is attributed to art. Public artworks aren’t on display for sale or as mere gifts to the public. Their function and worth become conceptual fodder — objects existing for the purpose of contemplation. Imagine: objects existing for ponderance. I find that notion delightfully obsolete. I consider myself an interdisciplinary artist because my works span three-dimensional objects, drawing, writing, performances, and ephemeral installations. My first public artwork, funded by the Emerging Artist Fellowship program at Socrates Sculpture Park in Queens, resulted in Argyle — a 20-foottall enameled wood monolith resembling the namesake pattern found on sweaters and socks. My second work, Giant Flowers, consisted of five flagpoles with ripstop Nylon windsocks resembling daffodils. Activated by the wind, it demanded much attention and maintenance, prompting me to move next to the park where it was installed. To celebrate the 50th anniversary of NY Parks’ Art in the Parks public art program, I staged Ursus Excursus in Central Park. This one-day art “happening,” open to the public, echoed a life-drawing class, with a human in a

polar bear costume as the subject. The intention was that viewers, at a later date, would question whether the resulting sketches were drawn from a real polar bear, evoking thoughts about the value of the real versus fake in portraying a living thing. A few years later, I created Temporary Red Dot in Highland Park, Brooklyn, my most passive work to date. The 28-foot diameter circle, planted with 3,000 red tulips, bloomed the next spring, seemingly out of nowhere, making it a uniquely ephemeral and apparently author-less installation.

Each of these projects has required diverse knowledge and know-how. While constantly researching and reaching out, I felt, in a way, like I never left school. Making outdoor art means creating something with no precedent. Undertaking projects I don’t necessarily know how to execute means constant learning. As the depth and breadth of my knowledge have grown, I’ve inadvertently taken on the role of a teacher. Like making public art, teaching is not an altruistic act. I believe teachers learn alongside their students, especially evident when I was invited to teach at the Oxbow School in Napa, California. In the twenty-two years since I was a student at Ox-

bow, I worked professionally as a printer at Paulson Fontaine Press, studied traditional photogravure at The Cooper Union, constructed aquatint boxes, and consulted on the building of private intaglio studios. Ironically, despite all of this, my own art practice never involved printmaking of any kind. Returning to Oxbow as a teacher was a huge honor, yet emotionally complicated, sitting at the desk where my mentor once sat.

I spent the flight, as well as my evenings and mornings, reading up on a technique I had not personally practiced in quite a while. What I discovered was that not only the information but the muscle memory of the tactile nature of the process had never left. I spent my free time working on my own copper etchings as a means of practice, generating examples of techniques my students would be using. It was an absolute pleasure to recite phrases and enact demonstrations that Stephen had done for me when I was the age of my students. By the end of the three weeks, seeing my class’s completed works—a huge accomplishment for such a short period— was more inspiring than the evidence that I had taught effectively. I was impressed by their ability to grasp new material and techniques, but I was moved by the content of the work itself. They were concerned with issues of identity, climate change, and how they related to each other and their environment.

Upon returning home, I bought a turn-of-the-

century miniature tabletop etching press from an antiques dealer in London and began restoring broken and missing parts. Collaborating with a local machinist and reaching out to specialty companies for idiosyncratic parts, this interdisciplinary process felt entirely continuous with my sculpture practice. Months later, I found myself with my own press, the first time in 22 years since I learned how to use one. I credit Oxbow for not only reinvigorating my interest in printmaking but also for influencing the type of thinking I encouraged in my students. I asked them to consider why make a print now, in an age where there is zero need for further innovation in image reproduction. What is the purpose of employing a technique designed to make multiples? What is the purpose of doing something pointless? The project I embarked on was, as most of my work is, site-specific. This time, specific to my own home in Chatham, New York, where an active railroad track runs through my backyard. It began by curiously placing coins on the track — a cliché novelty. But it soon progressed to placing other flattenable metal objects on the rails. The most successful and intriguing results were achieved using silver forks and spoons with intricate ornamentation. I began collecting them at local estate sales and thrift stores. I inked them using the traditional techniques typically employed when printing copper plates– hand-wiping oil-based etching inks so that the incised areas held pigment, while the relieved parts would remain blank. The resulting impressions

are strange embossed silhouettes of flatware that document a palimpsest: a synthesis of an action in a public space and a subversion of a traditional technique, manifesting a physical document of a conceptual process; all of which was inspired by learning while teaching. This project, rooted in the intersection of historical printmaking techniques and a conceptual artistic approach, became a testament to the ongoing evolution of my work. It exemplifies the interconnected nature of various disciplines within my practice, showcasing the adaptability and continuous learning that define both my artistic endeavors and teaching experiences. In navigating the realms of public art, interdisciplinary projects, and the pursuit of acquiring and sharing knowledge, my ultimate goal is to blur the distinctions between art and what we call “real” life, living in an amalgamation of experiences and creation.

Article solicited by Kylie

Martindale

Daniele Frazier is an artist living and working in Brooklyn, New York. Originally from Mill Valley, California, she graduated from the Cooper Union School of Art in 2007 where she received the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Trust Award. Daniele has created ten unique public artworks and maintains a studio where she makes sculptures and drawings. Her process intersects her interest in formal aesthetics with a research-based and socially-engaged practice. She focuses on themes of ecology, climate change, natural history, art history, and social critique. Daniele’s work humorously addresses the politics inherent to public art itself such as gender inequality, the difference between public and private space, and the definition of ownership.

Daniele has worked extensively with the NYC Parks Department and her work has been shown at The Queens Museum, Socrates Sculpture Park, Guild & Greyshkul, Museum 52, Rivington Arms, Ritter Zamet, and Gavin Brown’s Passerby, among others. She has made creative contributions to numerous commercial projects for clients such as Ssense, Tiffany & Co., Trademark, Officine General, Tomorrowland, Coach, Marie Claire, Mémoire Universelle, Behind the Blinds, Nina Ricci, Commons & Sense, and Theory.

Lessons from Across Borders: A Teacher’s Experience with Education Systems Around the World

Education is a crucial part of a child’s upbringing in most cultures, with many of them including further learning into adulthood. When people learn, society succeeds, and when society succeeds, humankind can transform and advance. Educational practices in every country vary from one another in some way, whether it’s simply a change in course material or a completely different structure of schooling.

To understand the complexity of education as it exists in every country, one must experience it in every country. While that in itself is impossible, a select few people have had the opportunity to either teach or learn in multiple cultures.

We contacted one of those people, Mr. Kieran Ridge, who is currently an AP United States History and Journalism teacher at Pacific Ridge School in Carlsbad, California. Some of his students have described him as “extremely passionate and particular in all of the work that he does” (A. Cobb, ‘24). His personal light has sparked passion in several people on campus and will continue to do so as long as he continues working.

Mr. Ridge disclosed that he has worked as an educator in the United States, South Korea, Australia, and briefly as a tutor in Japan. The following is an account of his experiences with education in each country, and his evaluation of each. Mr. Ridge consented to this interview and the creation of this article.

Q: Today, we’ll be conducting an interview with you to investigate your past as a teacher. What other countries have you worked in as an educator?

A: I first started teaching in Australia, and it was a little bit different than my later teaching experience. [When] I was working in that area, two different opportunities to teach for a semester were offered to me: one was in a Lutheran college prep school, and then the other opportunity that came up was to fill in at Boggo Road Jail, which was notoriously the most hardcore prison in that state of Australia at the time. It [was] shut down later because it was considered so brutal. So, I spent a semester teaching inmates there. It was supposed to be a literary class, but we ended up focusing a lot on literacy as well. Then, I taught in Northern California for [11 years], in Marin County, in the San Francisco Bay area. From there, I went to foreign schools. I just thought for my future and my family’s future, I should look to places that were more sustainable economically. I was asked, without applying, if I’d be interested in being

the English department chair at an international school in Songdo, Korea. It also made me think a lot about what some people call global English: in other words, learning a form of English that is accessible and usable around the world, regardless of dialect, regardless of the person’s primary language background. The grammar of Korean and English is really different. I expanded the English as a Second Language (ESL) program pretty aggressively, and the students did really well. They were smart, hardworking students; they just needed opportunity and resources. I taught in Japan as well, but when I was in Japan, I was an AP, SAT, [and] ACT tutor for a while. [After that], I had two teaching gigs. One of them was at a vocational college, so it was people who’ve left high school and then want to become flight attendants, airline workers, things like that. And the other three years were pretty interesting. I was teaching managers and staff at Amazon in Japan at their second biggest office.

Q: Where did you find differences in education approaches between each country?

A: A lot of it has to do with the differences in authority structures, and then the related communication styles in whichever country and culture you’re working in. So, because the communication style and authority structures are different, how do you do the classroom? For example, we have Harkness tables, right? It literally symbolizes that there’s no head. Whereas, when I was teaching in East Asia, people got nervous without a clear hierarchical authority system because they’ve been [taught] since preschool that there’s a time to speak and there’s a time to listen. Even for new employees and companies, they’ll tell you don’t even speak at a meeting until you’ve been there five years. In California, you might not even stay in a job for five years on average.

Q: Was there any specific approach you liked or disliked from a particular country you taught in, including the US?

A: It’s more of a comfort thing. All these countries function, mostly, and then [these] countries have dysfunction, but they all have their version of it. I liked the intense self-motivation of students in East Asia. But what I worried about was how much stress they were putting on themselves. [In California,] I feel like what’s uncomfortable for me sometimes is it’s just too laid back, and we’re trying too many things at the same time. It’s a typical California startup (in reference to Pacific Ridge School). But sometimes I feel like the students and even the adults are in a kind of ev-

erything, everywhere, all at once situation, and, to go deeper, you’ve gotta have some priorities, which means you’re gonna have to let go of some stuff. And that’s not very Californian.

Q: If you could implement any aspect of education from another country to this school, what would it be?

A: My daughter, every day, when she was in public school in Japan for seven years, she and all her fellow students had to clean up the classroom and the corridors. Like the students clean the class every day. The students learn so much respect and teamwork; I think, in some ways, they grew up a bit more. I think California, in some ways, still operates on the labor model that was created during the mission system, and the division of labor troubles me greatly. Certain sectors of society don’t feel like they need to clean up after themselves or get their hands dirty, and that kind of seems colonial, to be quite frank with you. I’d like us to be more cognizant of that, [like] cleaning up after your lunch, rather than saying someone’s paid to do it. But if you make that job ten times harder than it needs to be, that’s the difference between going home with some energy for yourself or going home exhausted.

Overall, Mr. Ridge’s experiences highlight the importance of understanding and respecting the diversity of education systems worldwide. By recognizing the strengths and weaknesses of different approaches, we can work towards creating a more equitable and effective global education system.

We would like to give a special thank you to Mr. Kieran Ridge, who kindly offered himself for this interview.

Students studying at a local coffee shop in San Marcos, California. Photos taken by Kylie Martindale on December 30th, 2023 with a Canon AE-1 using ISO 400 film.

Students studying at a local coffee shop in San Marcos, California. Photos taken by Kylie Martindale on December 30th, 2023 with a Canon AE-1 using ISO 400 film.

Environmentally Inspired

Dylan Smith

Coastal view of el pochote fishing village

Dylan Smith

Coastal view of el pochote fishing village

Sarah Otterstrom, founder and executive director of the non profit organization Paso Pacifico, is a conservation scientist with over twenty years of experience in Central America. She founded the organization in 2005 and since then has continued to stay involved with many projects relating to the tropical dry forests and Pacific coast habitats within Central America. Sarah serves on the editorial board of the Journal of Biotropíca, and has served in the Association for Fire Ecology as well as the Sociedad Mesoamericana para la Biología y Conservación. In addition to this, she is an Ashoka Fellow and the recipient of the Spirit of Entrepreneurship Award.

Paso Pacifico is a non profit organization based in Central America whose purpose is to “build wildlife corridors that protect biodiversity and connect people to their land and ocean.” Their mission is to restore and protect the Pacific Slope ecosystems of Mesoamerica, some of which include the endangered dry tropical forest, mangrove wetlands, and eastern Pacific coral reefs. They work with local communities, landowners, and partner organizations in order to “restore and protect the habitats that form building blocks for wildlife corridors.” Paso Pacifico’s approach aims to protect biodiversity where people already live, and they follow an “iterative process” that helps them choose and implement projects.

Empowering Women for the Sea is a project that focuses on the sustainable farming of wild oysters in the Paso del Istmo (a narrow bridge of land in Central America between Lake Nicaragua and the Pacific coast). In this community, oyster harvesting has been a main source of family income since pre-colonial times. Although this has been an important aspect to many locals, overharvesting and poor management practices have continued to push native oyster populations towards extinction. Without the help from Paso Pacifico and the development of the project, the loss of this resource would jeopardize the food security and environmental wellbeing of the town.

In the process of developing the project, it was important to understand the background and the important role of the oysters in the Paso del Istmo community. Oysters were a major food source in pre-Columbian society and continue to be to this day as a traditional way of feeding families. Both women and children collect and harvest oysters on the beaches of the El Ostional region of Nicaragua, specifically the tropical rock oyster. Women have been the ones to harvest oysters for generations, but their methods are seldom organized and much less sustainable. Oysters are relatively hard to find and they can only be harvested at a certain rate before risking depletion. When harvested, the local women tend to pry them off rocks causing damage to the reef. Many of the women shuck the oysters and sell them to men who then sell them to restaurants. The issue with this process is that the women sell the oysters without the shell, which does not meet

high market expectations. After much repetition of the harvesting of oysters, locals realized that it was not sustainable for their ecosystem.

Fortunately, in 2013, women from El Ostional asked Paso Pacifico for technical and financial support in developing an aquaculture farm for the tropical rock oyster. Their idea was to be able to farm local oysters to provide a stable source of food and income, while also restoring native shellfish populations. Through research that was conducted by a consultant named Angie Gerst, it was found that there was a strong potential for the development of a women’s oyster cooperative. It would work to empower women through establishing an industry that would “help them play a stronger role in community leadership.”

After researching and connecting with Sarah Otterstrom, the founder and executive director of Paso Pacifico, she was able to witness the implementation of this project first hand and shared her reflections in an interview.

Sarah saw how these women became more empowered through the project and how they faced certain obstacles to achieve their goals. She says that one of the ways that the women became empowered is that they organized to go to the government and protest against commercial oyster harvesters when they came into town. The commercial oyster harvesters were “out of towners” who came with large refrigerated trucks and diving gear. They supposedly had permits to do this but the women decided to go to the fisheries authority and argued that it was not ok for the commercial harvesters to come and harvest, especially because it was exactly what they were trying to protect. In response to this, the government decided to help “kick the commercial fishers out.” Sarah mentioned that “the women became politically empowered by this as they were trying to protect and stake claim to the oysters.” The women also had to negotiate with male fishers to leave their gear alone in their process, and they learned skills like swimming and boat driving, “so they became empowered in that way too.” Sarah believes the best part about this project is “that it has the potential to combine economic empowerment with sustainable fisheries.”

In 2016, the El Ostional organization celebrated their first harvest of the oysters. As this becomes more of a success, women are continuing to gain “more respect as leaders, fishers, and ocean stewards in their community, and their example is inspiring others.” As the organization develops, the women are beginning to work with neighboring villages in sustainable oyster farming. Paso Pacifico mentions that because they are “armed with sustainable aquaculture and the training they need to run a business, these women will improve their communities and make a difference for the coasts they call home.”

For more information about this and other projets, visit pasopacifico.org

How to Hear in the Middle of Nowhere

Time can be an ugly thing, especially in medicine. It was easy for Deborah to be forgotten, being so elderly and isolated. You see, time worked very differently out in rural Illinois, out near the swampish river and nestled between hills, corn, the sky. There were very few people for acres of land around, making the endless swaths of corn that surrounded the small town quite desolate. Here, insulated by a thick layer of trees and hills, there was no answer to urgency.

For extraordinary diseases, treated with extraordinary means on an extraordinary timeline, there were ways to minimize suffering. If you were forgotten in the midst of scattered rural life, on the other hand, there was nothing.

And how quickly this festered in Deborah’s life. A penny-sized sore seeded on her leg. I often wonder how it had felt for her, to be forced to witness her brittle skin crack around the edges and to the bone. Basal cell carcinomas are some of the most common and treatable forms of skin cancer– if caught early on. If Deborah’s pleas for treatment were heard earlier, her suffering could have been crushed before it took root like an invasive seed. But it had lived on, feeding on the isolation in rural life. There was no one capable of treating her within a hundred miles, and so Deborah’s leg deteriorated. By the time Deborah and her son had reached our clinic after a two hour drive, intensive treatment was immediate. Septic shock had already begun to spread from the exposed bone.

Palliation was in sight.

The morning I met Deborah, she had laid there, shivering, on a metallic stretcher with an oxygen mask. Her mouth moved discordantly when the physician peeled back her pant leg to examine her wound. It wept like a newborn baby, pink and tender. A fear-tinged quake shook the stretcher, and she cried out.

Let her relax. Slow. Steady.

Those who feel pain the worst are those who had to live with it the longest. Neglect almost always invited despair, and with despair came dread. It was as if she foresaw all the pain she would have to bear in a moment, waning her tolerance for it until there was nothing left.

The room was quiet for a moment as we prepared to treat her. I stood in her line of sight, blocking the IV cannula, bandages, antibiotics, and fluids being unwrapped. Deborah’s stabilization was our first priority. The balled-up plastic packaging had crinkled noisily: a bright, sparkly, popping sound in the silence.

Deborah always had good ears, her son had blurt-

ed. His voice was tight and trembling, soft like the wind whistling through the fields of corn outside the window, as he broke the silence. I had just nodded and smiled; it was normal for family members to spill themselves to anyone in the room. Perhaps it felt safer this way, to share the burden of their fear with a stranger in a surreal environment: an unfamiliar room of robotic sterility that felt fussy in comparison to the brutality of death and pain that permeated the building. From him, I learned that Deborah had once been a nurse in this hospital before retiring to the town where she had grown up. After a lifetime of long shifts and codes, she had found the familiarity to be merciful. Her favorite thing to do was to listen: to the forest breathing at night, corn stalks crackling under her feet, cicadas singing in the summer heat. Briefly, I had wondered how I could bear it all: the weight of his love and admiration for his mother, how freakishly grateful and ordinary his voice was, how easily Deborah could have avoided all of this if only she was listened to. I couldn’t help but watch as a nurse prepared her IV, wiping her papery, translucent skin with an alcohol pad. Her eyes quivered in their sockets at the cold sting, and she groaned.

Pause. Breathe.

The nurse sought the first vein and pushed the needle forward, stepping back when the first flash of blood flooded the cannula’s chamber. I watched as her blood pressure began to rise.

The afternoon light sifted through the corn, turning the golden stalks red and orange. The fields rippled as another gust of wind shook the skies, clearing the clouds to bathe the soil in one last glow of autumn warmth. Her son had cracked the window slightly while we waited for the nurse to finish.

Perhaps it was too little too late, but we listened quietly in that moment: to the birds, the breeze, the people laughing in the parking lot outside the window. Deborah’s breathing was stronger now, slower. For a moment, I could hear a vast universe of hope in her: an eye-watering crescendo of relief that she had finally been heard. That she had not been forgotten in her community. And oh, was this notion loud to me. It was as if I had heard everything about medicine at an arm’s length, a mile’s stretch away my whole life. But here was Deborah, her preventable condition screaming volumes for change, progress, because it did not have to come to this, at the cusp of my ear. I never saw Deborah again after they transferred her to a larger clinic, but I hoped that she had recovered enough to sit among the stars and trees again.

But most of all, I wished that she had been heard sooner.

It should be remembered that rural communities are a way of life for millions of Americans. And yet, we as young, pre-medical students often turn away from these populations, leaving them forgotten in the beautiful and fast-paced chaos that is medicine. I think that it’s easy to forget that every single person on this planet is sincerely afraid of being alone to face whatever comes next, be that in their treatment or their lives. But in rural communities especially, these fears are often left neglected. None of it is easy, but I don’t walk around solemnly in my local rural hospital, dwelling over each missed opportunity or grieving family member. But I can listen to them. I can share the weight of their palpable fear and love. I can be Deborah, listening to learn how to shape the vast world around us for the better. Sometimes, being heard can make all the difference.

Cindy Mu is a student at the University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign. She was featured in “What I fight for,” a Malala Fund video series where young women share the big and small reasons they’re fighting for change and what they hope to protect through their activism.

A Conversation with a Tea Scholar

Abigail Qiu

Adelicate fragrance of jasmine floated into the air as I slowly sipped the freshly brewed tea according to the directions I was given. It is said that you cannot gulp it down like water as it will hurt your health. For the tea to be digested properly, we must 工夫茶, which means “take time with tea.“ During the brewing process, Zhangbo Zhang (Bob) took a small wooden scoop of dried tea leaves and placed them into the purple clay teapot. When he poured the hot, but not quite boiling water into the pot, I felt a layer of aroma in the steam that slowly lingered past my nose. Then, Bob passed me a small teacup and instructed me to tap my fist on the table to show my appreciation when being served.

I first heard of Bob during a relaxing sunset walk with my father. He was telling me that his new renter was really into tea–how he collected only the finest tea leaves and knew of several rituals to capture the various essences of the teas. Tea is an art of Chinese culture to the extent that some dedicate their leisure time to studying the his-

tory, preparation, and intricate nuances of consumption. Bob was one of these scholars, owning a haven dedicated to this ancient art form in his very own kitchen. In the middle of his table, next to a captivating stack of books, sat a wooden tea ceremony tray with ceramic and glass cups.

As he prepared to serve me several types of tea, he introduced me to the history of this practice. Tea is both a facet of Chinese culture and a Chinese medicine. It has many variations and comes from numerous places. Only the most beautiful mountains and nutritious water can produce quality tea. You only need to know which mountain and water it was cultivated from to know if the tea is of good quality. There is a proverb in Chinese, 一方水土一方人, meaning tea like water is very personal and local to people. In extreme cases, drinking the wrong tea can hurt and sicken you. That’s why Bob recommends that I start with 冻顶乌龙 (Frozen Tip Oolong tea) since it is a mild and gentle tea. The one I drank was specifically harvested during April around the Tomb Sweep Festival (清明节). Depending on when the tea was harvested, Spring or Fall, the tea will take on a different taste.

At Bob’shis age, he likes 普洱茶 (Pu’er tea) from the 云南 (Yunan) province of China. It’s a fermented and mildly warm tea, perfect for