08 23

08 23

08 RUDA is starting to approve private housing societies. Where do things stand?

12 Pakistan no longer has a population problem

18 Beyond all the talk, are electric vehicles truly affordable in Pakistan?

23 Modi’s election performance is set to jolt Pakistan’s rice market. Here’s how

25 Prepare for turbulence

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz Khan - Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Editorial Consultant: Ahtasam Ahmad - Business Reporters: Taimoor Hassan | Shahab Omer

Zain Naeem | Saneela Jawad | Nisma Riaz | Mariam Umar | Shahnawaz Ali | Ghulam Abbass

Ahmad Ahmadani | Aziz Buneri - Sub-Editor: Saddam Hussain - Video Producer: Talha Farooqi

Director Marketing : Mudassir Alam - Regional Heads of Marketing: Agha Anwer (Khi) Kamal Rizvi (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) - Manager Subscriptions: Irfan Farooq Pakistan’s #1 business magazine - your go-to source for business, economic and financial news. Contact us: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

After controversial beginnings, the Ravi Riverfront Project is getting into the hands of private developers. What does it take?

By Shahab Omer

Atiny detail has changed in the many massive billboards all over Lahore advertising housing societies. At every corner, every street, every turn in the city there is a billboard bearing the ad for some ridiculously shady project named something like XYZ Cooperative Society, ABC Gardens, 123 Villas, Al-Something-or-the-Other Town, and Mountain/ River/Ocean City.

Most of these societies are unregistered, unapproved, and illegally advertising their projects. The pattern they follow is predictable. A real estate developer purchases a small tract of land in some godforsaken corner or outskirts of Lahore or an adjoining city. Before they create a masterplan or even acquire all the land, the developers start marketing their society and selling plots. The money generated from this is then used to fund the project, except when the funds inevitably dry up, lots of people are left stranded because their money is tied up in the project.

How do they get away with this? A lot of the time, these real estate developers simply lie. They put up signs and advertise their societies as if they have gotten approval from the relevant development authority when, in fact, they have not. As such, you’ll find plenty of billboards bearing the stamps of the LDA, RDA, GDA, and other such bodies. But in recent times, this little stamp of approval has been replaced by approvals from the Ravi Urban Development Authority (RUDA).

What is RUDA? The organisation has been around since 2019 and is responsible for developing a new city along the banks of the Ravi. Empowered by provincial legislation, RUDA has over time become a contentious body and has been dragged through the courts more than once. But as things stand, RUDA has confirmed to Profit they are giving approvals to different real estate projects. Those getting the approvals include the usual suspect, with Malik Riaz’s grandson a prominent name among those investing.

This means that the RUDA, which is already running the show unbridled along the banks of the Ravi, is now on a spree allowing private developers to come in and create housing societies. RUDA claims, however, they are doing things differently. Their approval process is more stringent according to them, but to what end is all of this happening?

The Ravi Riverfront Project is many things. At its best, it is a vain, bloated, misguided attempt that many environmentalists and hydrological experts have called an impending ecological and social disaster. At its worst, it is an uncaring attempt to turn the Ravi and its embankments into a playground for real estate developers that intend to treat it as a cash-cow for at least the next two decades. For better or worse, it has become a bone of contention with political undertones.

The idea for a riverfront project on the banks of the Ravi is not a new one. In fact, it was first proposed as far back as 2006, and underwent a feasibility study in 2013 under the PML-N government. The idea has long been a lucrative if elusive pipe-dream. Lahore, as many are aware, has swelled up and its urban sprawl has seen it become one of the most polluted cities in the world which regularly tops the global rankings for the worst air quality.

Ideas like the Ravi Riverfront Urban Development Project are the sort of sweeping solutions that populists like to extoll. Essentially, the Ravi riverfront is the plan to make a new city from scratch. The project would be Pakistan’s second-largest planned city after Islamabad, covering an area of 102,074 acres, catering to a population of up to 15 million people. It is an ambitious undertaking — one that is born as much out of a sense of frustration with the state of our urban centres as it is out of necessity. In fact, in a comprehensive and eye-opening article published in Dawn back in June 2021, it was pointed out that the development of new cities and riverfront projects is not unique to Pakistan, and that such projects and several new cities have been planned across Asia and Africa in recent years. It is essentially a desire to start from scratch. To plan and control and build a city with the benefit of hindsight. The foundation rock for the utopian riverfront project was first laid in 2019 with the passage of the special legislation that established RUDA. The authority would not work under any other body in or related to Lahore, and would have complete control over the project. In fact, the Lahore Development Authority (LDA) and similar bodies in Gujranwala and Sialkot would be subservient to RUDA. So complete were the powers given to RUDA that not only was the authority entrusted with the entire responsibility for the project from planning, to acquisition, to development that the legislation which created

RUDA granted the authority and its employees immunity from all legal proceedings, and “no court or other authority” can “question the legality of anything done or any action taken in good faith under this Act, by or at the instance of the Authority.”

From the get-go, the warning signs were present. The law that had created and empowered RUDA seemed to go beyond reasonable limits because of the lack of accountability that the authority had to office. By early 2021, when the project was in its early stages of acquiring land, troubles began to rise when local communities resisted selling their lands to the state after which RUDA announced that it would feel free to acquire the lands by force — something that article 4 of the special legislation that RUDA created allowed. The matter went to court. In January 2022, Justice Shahid Karim of the Lahore High Court (LHC) in a 298page long judgement declared that the scheme was “unconstitutional” on the grounds that it lacked a master plan. Later, the SC would give the project relief although the matter is still Sub judice.

So how exactly is RUDA going about approving societies, and will they be able to make sure they save the project from different kinds of frauds? To answer these pressing questions, Profit sat down with Colonel (Retired) Abid Latif, RUDA’s Director of Public Relations and Communications, in an exclusive interview. “Yes, the approval process for housing societies in Ravi City has begun but it’s not as simple as it appears,” he affirms.

He explains that every approval must align with RUDA’s master plan—a comprehensive blueprint designed to ensure the cohesive development of Ravi City. This master plan, he says, is the touchstone against which all projects are measured. Only those that fit seamlessly into this vision are granted approval.

Despite the flood of advertisements claiming RUDA’s endorsement, Colonel Latif reveals a surprising fact: so far, only two private housing societies have been fully approved, and even that approval comes with conditions. “The process is rigorous,” he notes, “designed to maintain the integrity and vision of Ravi City.”

“RUDA is not just constructing a new city—we are building a new standard of urban governance. Fraud prevention is a cornerstone of our strategy. By adhering strictly to the master plan, RUDA aims to create a transpar-

ent, accountable, and secure housing sector,” he added.

Colonel Latif further shed light on the intricacies of the approval process for housing societies and explained that RUDA has streamlined the approval process into two distinct modes, the first of which is the Provisional Planning Permission (PPP). This mode, particularly appealing to investors and sponsors, is designed for those who do not yet own land within RUDA’s jurisdiction.

To obtain PPP, a developer or investor must submit an application to RUDA, complete with a checklist of necessary documents. This checklist ensures that all required information is provided upfront, avoiding delays and ensuring a smooth evaluation process.

The journey to PPP begins with the developer identifying a location and presenting RUDA with the Khasra plan of the area, indicating their intention to establish a housing society on that land. RUDA then forwards the proposal to its internal planning department for a thorough evaluation against the master plan. This step is crucial to ensure that the proposed housing society does not encroach on government property or land designated for other RUDA projects. The planning department then generates a master plan compliance report. If the proposal aligns with the master plan, the approval process moves forward; if not, the developer must revise and resubmit their proposal.

Once the proposal is deemed compliant, the developer pays a scrutiny fee of Rs 2,000 per kanal of saleable area. For instance, if the society is to be built on five hundred kanals, its saleable area of approximately 250 kanals, the fee is calculated accordingly. Following this, the sponsor enters the scrutiny phase, during which they must present their financial statement, submit the required documents, agree to RUDA’s terms and conditions, and pay a Trunk Public Infrastructure Development (TPID) fee of Rs 800,000 per kanal of saleable area. To ease the financial burden, developers can pay twenty-five percent of the total fee upfront, with the remaining 75% payable quarterly over three years, for which investors must give post-dated checks to RUDA.

The verification process then kicks off, focusing primarily on the land title check. RUDA sends the locked Khasra numbers to the Additional Commissioner Revenue (ADCR) to verify that the land is not already acquired by the government or earmarked for a government project. If the land title is clear, the ADCR issues a No Objection Certificate (NOC). Given that the Ravi Urban Project spans two districts—Lahore and Sheikhupura—the relevant ADCR issues the NOC for their respective district.

After obtaining the NOC from the

ADCR, we publish a public notice in various leading newspapers. This is done to invite any objections within fifteen days. If any objections are raised during this period, they need to be resolved first; otherwise, the process moves forward towards the technical approval.

Next, RUDA’s planning department forwards the report to the land department, detailing the locked Khasra numbers for the developer’s project. This step is essential to prevent disputes when the developer begins their project. A comprehensive report of the entire process is then prepared, with recommendations from RUDA’s internal wings sent to the RUDA CEO, who ultimately grants the investor PPP. However, PPP is valid for only one year. During this period, the investor must complete all the necessary approval processes. It’s a race against time in many ways. If they fail to do so within this one-year timeframe, they will have to pay the PPP scrutiny fee again to renew their provisional status.

However, it is important to note that PPP does not equate to receiving an NOC for the housing project; it is simply the first step for investors who do not yet own land within the Ravi Urban Project.

One major benefit for the developer in obtaining PPP is that it allows them to proceed with a soft launch of their project and market it. By granting PPP, RUDA also generates a significant amount of revenue through fees such as the TPID fee and scrutiny fee. This revenue is utilised for RUDA’s infrastructure, development works, and river restoration projects.

When asked if it would be difficult for an investor to complete the entire process within a year, considering that if the land is not acquired within that time or the landowner is unwilling to sell, the PPP duration would expire, he responded, “Yes, that’s correct. It often happens that a developer or investor fails to purchase their planned area within a year. It is also true that sometimes the identified area is bought by someone else. In such cases, the investor must pay the fee for the PPP extension. However, they can inform RUDA’s land branch of an alternative area where they plan to establish their project.”

“Now, let’s move on to the second mode, which is Technical Approval,” he began, “This phase is crucial for both investors who already own land within RUDA and those who, after obtaining Provisional Planning Permission (PPP), are ready to move forward.”

He explained that RUDA’s technical evaluation process was nothing short of exemplary. It was designed to ensure that every

private housing society complied with RUDA’s stringent regulations.

“The technical evaluation begins with a thorough technical scrutiny of any project. During this phase, we collect two types of fees from the investor or sponsor. The first is the TPID fee, which we’ve already discussed, and the second is the land conversion charges,” he explained.

In revenue documents, land is often classified as agricultural, even if it no longer serves that purpose. “Many lands in the densely populated areas of Lahore are still listed as agricultural in revenue records, although they have been converted to urban or peri-urban areas,” he elaborated. “However, in RUDA’s master plan, these lands are not classified as green or agricultural. Their status as agricultural exists only in revenue records, which were established before the creation of Pakistan.”

“But if a land is marked as green or part of the river area in the master plan, a housing society project cannot be established there.”

When asked about the fee RUDA has set for land conversion charges, he responded, “This fee is also applied to the saleable area and is charged per kanal. We check the DC rate of the land and charge two percent of the DC rate per kanal.”

“If a sponsor clears the technical scrutiny, it means they are likely to receive Technical Approval,” he continued. “In this mode, RUDA ensures that the project meets all technical standards. This includes checking the size of roads, sewerage systems, electricity transmission, solid waste management sites, and other technical aspects of the project.”

He added, “During this period, the sponsor or investor completes all legal and financial formalities for their project, and RUDA’s internal wings recommend the case to the CEO, who then grants Technical Approval.”

However, he was quick to clarify, “It’s important to understand that Technical Approval is not the same as an NOC for the housing society. There are many conditions attached to the Technical Approval. During this phase, RUDA monitors the investor’s project to ensure compliance with these conditions.”

He listed some of these conditions: prohibiting the use of forest areas, preventing the use of areas designated for city services, and returning any river channel areas included in the project. “There are numerous such conditions,” he said. “Additionally, the investor is provided with a payment plan for the remaining seventy-five percent of the TPID fee, which must be paid within three years. If the investor fails to meet the relevant conditions, they will not receive the NOC for the housing society.”

“When it comes to Technical Approval, the investor’s project plan gets approved, and their ownership of the land is recognized. The

fees they pay under TPID demonstrate their commitment to business. During this time, we ensure that the developer honors their commitments to the public about the nature and type of project they are selling. To enforce this, we mortgage some of the plots in various project areas, though these plots are returned to the developer in stages.”

When asked about the mortgage process, he explained, “A relevant officer from RUDA transfers the titles of these plots to RUDA’s name through a transfer deed recorded in the Board of Revenue. Our condition is that parks, graveyards, and roads within any housing project must be transferred to RUDA. This ensures that if a developer initially gets approval for a park in a specific area but later thinks it would be more profitable to build a commercial market there, they won’t be able to do so because the land has already been transferred to RUDA and must be used as a park.”

He continued, “We mortgage plots to ensure developers work according to the approved plan. As they fulfill their requirements, we return the plots to them in phases.”

When asked if acquiring a specific amount of land was necessary for housing societies, he clarified, “It’s not. Projects with an area exceeding 100 kanals fall under the private housing society category, while those below one hundred kanals are considered land subdivisions. Even a project with forty kanals will be called a land subdivision. However, the size of roads, commercial areas, and green spaces will vary based on the project’s size. For larger projects, these areas will naturally be bigger.”

“After receiving Technical Approval, the investor must pay a sanction fee of 15,000 rupees per kanal of saleable area,” he added. “Though this fee is relatively low, we are considering increasing it in the future.”

Following Technical Approval, the investor needs to obtain service design approval. This includes submitting plans for water supply, landscaping, horticulture, and a flood safety report. Until RUDA completes its work on the riverside, it is the sponsor’s responsibility to take flood safety measures. We’ve already issued letters to around one hundred developers and sponsors regarding this.

“We also impose two types of fees during the service design process: 10,000 rupees per kanal for the design specification of water supply and sewerage, and 1,000 rupees per kanal for the design specification of roads and bridges.”

He explained, “We monitor to ensure that no development occurs on the project before final approval or NOC. Many developers set up gates, boundary walls, or offices on the project area prematurely, which is illegal and incurs fines. These penalties vary depending on the size of the society. For example, a fifty-acre

scheme would be fined twenty thousand rupees daily.”

“After completing all processes, paying the fees, and settling any fines, the project is submitted to the CEO for final approval, thus granting the NOC for the housing society.”

“Although this is a lengthy process, it is designed as a one-window operation where RUDA handles everything except the NOC issued by the ADCR. Our model is different from LDA (Lahore Development Authority) or any other development authority. In LDA, developers need approvals from WASA and TEPA, among others, but in RUDA, over ninety percent of the work is done under one roof. This one-window approach aims to streamline approvals based on regulations and the master plan, minimizing hassle for the developer.,” he continued.

When asked how many housing societies have received approval after going through this lengthy process, he replied, “If we talk about complete approvals, only two housing societies have received them so far. The first approval was granted to a private housing society last July, and the second followed after that. Additionally, five private housing societies have received technical approval, and PPP has been granted to seven projects. Meanwhile, we have about 40 cases under process.”

When further questioned about the numerous housing societies advertising on the roads with various sign boards claiming RUDA approval, such as Park View Housing Society, he responded, “Park View or River Edge housing society has received technical approval for 11,000 kanals of land for their housing project from RUDA. The project’s administration has also deposited approximately one billion rupees to RUDA in various fees.”

When asked about previous statements from ministers and secretaries that River Edge was an illegal project that could never receive approval and that it had encroached on much government land, he clarified, “The project administration will exchange the government land currently used by the project with land from their project area.”

One of the societies that have been approved by RUDA is BSM Developers’s New Metro City. This is the society that is owned by Malik Riaz’s grandson. is also approved by RUDA, he responded, “The mentioned society has been granted PPP and has received technical approval for 589 kanals of land because they completed the formalities for that specific area.”

He further explained, “New Metro City initially sought PPP for 500 acres, but to obtain technical approval, they needed to show ownership of the land. When we excluded the area

designated for roads and infrastructure from their owned land, 589 kanals remained. If New Metro City claims to have launched a scheme on 20,000 kanals, that’s a separate matter, but their technical approval is only for 589 kanals. They have one year to purchase additional land. After obtaining PPP, they had the opportunity for a soft launch, which they utilized. We allowed the soft launch but stipulated that they must meet all terms and conditions within a year.”

He added, “Initially, BSM requested technical approval for 208 acres, which they had purchased, but 1,200 kanals of that land fall within the river channel, which New Metro City will have to surrender to RUDA.”

When asked why societies give the impression that they are fully approved after just technical approval or PPP, or why they don’t mention the exact area approved in their advertisements to avoid misleading the public, he responded, “We are planning to amend our regulations regarding advertisements to eliminate any ambiguity for the public.”

Further queried about housing societies selling more plots than they have, Colonel provided an interesting update: “RUDA has begun working on preventing fraud through file sales. We are about to approve a law under which no housing society can sell plot files. Instead, they will sell security papers or allotment letters issued by RUDA. This ensures that if a housing society has 300 approved plots, only 300 allotment letters will be issued. They cannot sell 500 files if they only have 300 plots. This means they must sell actual plots, not files.”

He continued, “We have already implemented this in our housing projects, like Chahar Bagh, where allotment letters were issued through balloting, and no files were sold. This will set a new trend in Pakistan’s real estate sector, which will likely be followed later. This initiative was driven by RUDA’s CEO and is expected to be approved in an upcoming board meeting.”

When asked about concerns that sewage from these housing projects will pollute the Ravi River, despite RUDA’s efforts to restore it, he explained, “The sewerage system for Ravi City is designed so that no wastewater from housing societies, commercial, or industrial areas will go directly into the Ravi. Instead, it will first go to water treatment plants, be purified, and then flow into the river. The problem with new developments in Lahore was that their sewage went into dirty drains, which then flowed into the river, heavily polluting its water. Seven dirty drains from areas like Allama Iqbal Town and Samanabad empty into the river, along with four more from the other side. We have mandated that every project must obtain an NOC from the Environmental Protection Agency.” n

While the rest of the world struggles with low birth rates, Pakistan is entering the sweet spot of the double demographic dividend. We should abolish the Population Welfare Department to keep the demographic party going longer.

By Farooq Tirmizi

Everything you know about Pakistan’s so-called population problem is based on a static picture of the data that is 30 years out of date. You probably think we have too many children and that our population is growing too fast. That is wrong.

Pakistan – the sixth largest nation in the world – is about to hit a quarter of a billion people in population some time later this year or early next year, and contrary to what you may remember from your Pakistan Studies curriculum, that population number is now an asset, not a liability.

We do not mean to suggest that Pakistan’s population was never a problem. It was. But things change, and we in Pakistan tend to not pause to notice when things have improved. We especially do not do so when noticing such a thing involves analysing slow-moving data, and there are few things slower-moving than demographic trends.

We shall start this discussion by defining some terms, and asking you to jettison the notion that “population” is a problem. More specifically, we want this to be a discussion of demographics: the characteristics of the population, rather than its size. As we will demonstrate, the mere size of a population is not in itself an indication of a problem, and indeed, all things being equal, a larger population is preferable to a smaller one.

No, Pakistan’s problem was two-fold: the composition of the population, and its growth rate, both of which would make it difficult for the nation as a whole to escape poverty. Simply put, it’s not that we had – at any point in our history – too many people. It is that too small a proportion of the population could earn a living, meaning each earner had too many dependents. And given the fact that we had too many dependents because the number of children was very high, that also meant that the population was growing faster than was possible for the government to cater to its needs.

This picture that we just described in the previous paragraph was likely what you mostly knew about both from learning about it in school, and through your lived experience. It was accurate as of about 1995. But sometime around that year, things began to change. The change was very slow at first and was not really discernable until about the mid-2000s. But the change in course has been unmistakable since then.

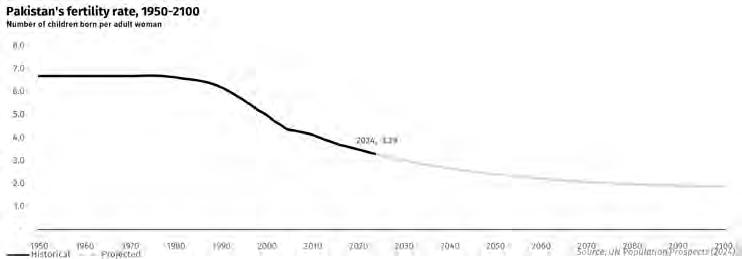

Here’s the summary: the single factor that made Pakistan’s demographic composition a problem – its fertility rate, or the average number of children born per adult woman in the country – is now about to hit the sweet spot that will allow the country to reap what economists called the double demographic dividend. We used to think of our population as a liability. In reality, it

was a long-term investment that is about to start paying dividends.

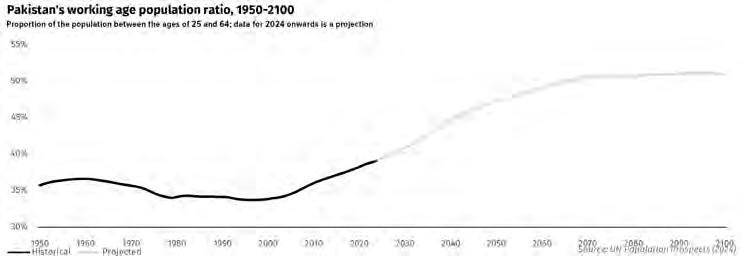

For this story, we looked at several variables that describe Pakistan’s demographics from 1950 through the present year and projections through to the year 2100. We understand scepticism about long term projections, but demographics is one area where long term projections are bit easier than other areas: it’s easy to tell how many 25-year-olds there will be 20 years from now because we know how many 5-year-olds there are today and have reasonable estimates of mortality and migration rates.

As we go through the data, the following three things will become evident.

1. Pakistan’s population was historically a problem because there was a period of about 75 years when we were having more children than needed, but this was entirely due to a decline in infant mortality that most people did not see coming.

2. Pakistani families are now having fewer children, so the “too many children” problem is basically over, and we will now see an increase in the labour force participation rate from now until some time in the 2090s, based on current trends. This means more income, more savings, and higher economic growth, which means that the party in Pakistan’s economy is about to get started some time in the next 5-7 years.

3. Pakistan’s fertility rate has not declined too fast yet, which means we may yet have the opportunity to make sure we do not follow the East Asian nations into demographic suicide. That means abandoning the notion that “too many kids” is a bad thing (it no longer is), and the Population Welfare Departments of every provincial government should be redirected to focus purely on maternal and infant health. Contraception no longer needs to be a focus.

One quick note about the data utilized in this story: nearly all of it utilizes historical data and projections made available by the UN Population Prospects Report for 2024, which in turn takes historical data from sources such as the population census in Pakistan, and then applies calculations to project data between census years, estimate underlying trends, and then make long-term projections.

Can these projections be off? Yes, but usually not by much, since these are slow moving trends where the underlying data needed for the calculations tends to be easily available.

Why we had “too many” children

The past is another country, goes the old adage. We tend to think of the generations where 6 children were the norm as though that is simply what they must have wanted, or that they did

not have contraception and so therefore did not know any better.

But take a look at the data for infant mortality, and you will begin to see a clearer picture of what happened. We gathered data on infant mortality in what is now Pakistan from the year 1800 through the present day to the year 2100 (yes, 300 years of data). For most of that time, the probability of a child dying before turning five years old was greater than 50%.

People in the 1930s through the 1980s did not have 6 children because that is how many they wanted. They had 6 children because they were taught that is how many you have by people who used to have 6 children because they knew that, in their day, only about 3 would survive.

Indeed, infant mortality was higher than 50% in the region that is now Pakistan until 1927, and did not go below 30% until 1956. My father’s generation, in other words, could expect one out of every three siblings to be dead before the age of 5, and were operating under cultural assumptions formed even earlier, when every second sibling would not live beyond their fifth birthday. The infant mortality rate did not go below 10% until 2006 and is still above 6% today. In developed countries, it is usually well below 1%.

We now know that it takes about 2-3 generations for data about family sizes to take effect among a population. Now that this information has trickled through – that you do not need to have so many children because nearly all of them will survive – people in Pakistan are choosing to have fewer children.

But until that happened, Pakistan’s population absolutely skyrocketed. People kept on having 6-7 children because they thought that is how many they should have, but instead of only 3-4 children surviving into adulthood, soon enough, nearly all of them were.

Pakistan’s population growth peaked in 1981 at 4.3% after infant mortality had been falling for more than 50 years, but had not yet impacted the decisions of parents in the country to adjust their conception plans. That year, the fertility rate in the country was still above 6.6 children per adult woman in the country, almost unchanged from its peak of 6.7 children per woman.

Since the early 1980s, however, Pakistan’s fertility rate has begun to decline, especially as more and more families realised that the spectre of infant mortality was fading into the background. Since then, it has begun a steady, near-uninterrupted march downwards, declining by an average of about 0.72 children per woman every decade, although the trend has been slowing somewhat over the past decade or so.

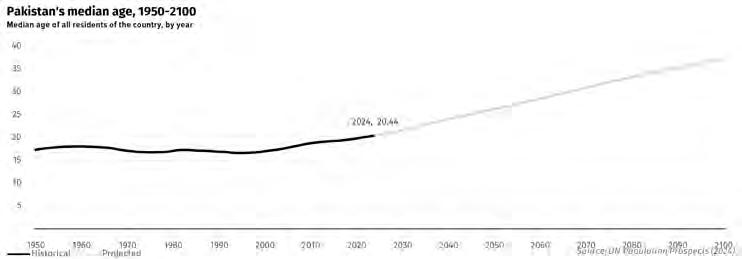

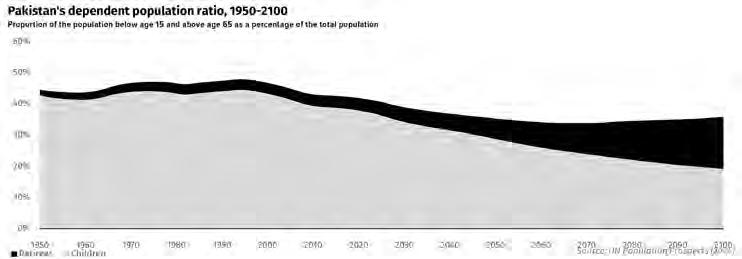

The effects of declining fertility, however, take decades to be felt, and in the first decade and a half of this decline, the proportion of the population under the age of 15 actually increased. This proportion is measured through a variable called the child dependency ratio, which is the number of children per 100 prime working age adults (aged 25 through 64), and in Pakistan, this peaked in 1994 at 85.5 children under the age of 15 per prime working age adult. For context, that year, the same number was 33.3 in the United States and 30.3 in the UK.

Since then, the child dependency ratio has been coming down dramatically, which is pushing down Pakistan’s total dependency ratio. That number adds the number of oldage adults over the age of 65 to the number of dependents who must be taken care of by the prime working age population. In 1994, the total dependency ratio in Pakistan was also peaking at 92.1 dependents per 100 prime working age adults.

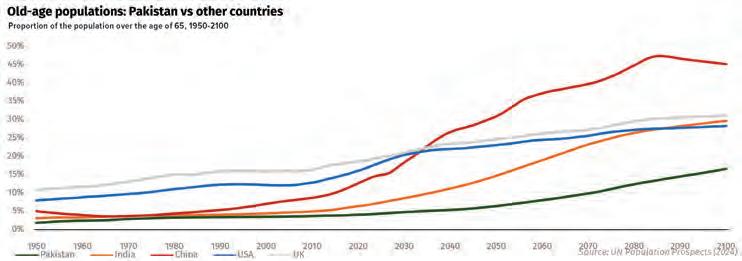

As is evident from the number above, at least in the 1990s – and largely even today – Pakistan’s dependents are almost entirely children, with very few people in the retired phase of life.

Here is the thing to understand about the dependency ratio: yes, both components – children and retirees – cost society, but there are two obvious, but important, differences between those two components:

1. Children are, on average, cheaper to take care of than old-age retirees.

2. Since children will, on average, become working adults at some point in their lives, the expenses that go towards taking care of them are better thought of as a longterm investment rather than a consumption expense.

We point out these two things to highlight the following fact: high childhood dependency ratio is a problem that eventually solves itself. High old-age dependency ratio is something that can only be dealt with by having more children coming into the world than people exiting the workforce.

Since Pakistan’s dependency ratio peaked in the 1990s almost entirely because of children, we are now in a position to reap the benefits of those children aging into the workforce. And since Pakistan has not followed South Korea and most of East Asia into demographic suicide, we continue to have children at a slightly higher than ideal rate.

This, however, means that Pakistan’s prime age working population as a percentage of the total population will continue to expand from its low point of around 33.7% in the late 1990s well into the 2090s, peaking somewhere around 51% in the 2090s if current trends hold. A child born this year will be retiring in their 70s in a Pakistan where the workforce is still expanding.

Why is this important: because underlying every single economic miracle story you have ever read is this exact demographic trend. It is easiest to understand this through the life cycle of an individual worker, and its effect on the overall economy through the average age of the population.

n the 1990s, Pakistan’s average age bottomed out at below 17, meaning over half the population consisted of children and adolescents usually not part of the workforce. We had a lot of children to put through school, and not nearly enough adults to earn the money to pay their fees and other expenses. Our economy was at its most cash-strapped back then.

The median Pakistani hit age 18 in 2006, the late Musharraf era, when they started being able to earn a bit more of a living. The magic of an expanding workforce is such that the mere availability of working age adults means that at least some employers will be willing to pick up that extra labour, even if at a very low price, which in turn allows them to generate an income. However meagre that income might be, it still allows them to spend a bit of money, which in turn induces more demand for goods and services, and thus for more labour to create those goods and services.

In one’s late teens and early 20s, when a person is just starting out in the work force, it is usually difficult to get a well-paying job because employers do not yet value your skills much. In a country with a young population like Pakistan, this means that starting salaries barely have to increase at all, even with inflation, because every year there will be an even larger crop of young school and college graduates to take the jobs of those who are just one or two years into the workforce.

This is the situation Pakistan is in right now. The economy is growing, but starting wages will not rise for a few more years because the number of young workers available outstrips demand for that labour. But even at that low price, the labour exists, the income is generated, and expands the spending capacity of the household to which that young person belongs, thereby increasing the demand for consumption goods.

Since wages are low, the ability to save is also quite low, but demand for consumption goods continues to increase. We do not generate enough domestic savings to invest in the production capacity ourselves, and do not

yet attract enough foreign capital to make up the difference in capital needed to increase our productive capacity.

This is why we have high and growing demand for imports, which every government stupidly tries to subsidize by keeping the exchange rate artificially low.

Pakistan has historically had a surplus of people who are children or very early in their careers. Over the next few decades, we will get a larger and larger share of the population being later in their careers, and this will have some downstream effects on the overall economy. Let’s continue the story of this “average” worker to find out what lies in store for the economy as a whole.

Around one’s late 20s and early 30s, one starts establishing one’s value, and generally sees a significant increase in salary from the starting point. In most countries, including Pakistan, the highest percentage increase in salary typically comes during one’s 20s.

Yet despite the increase in income, savings capacity only goes up very slightly because this is also usually the point where people start get-

ting married and forming households. Consumption expenses usually continue to rise at or even slightly faster than incomes.

In one’s late 30s and early 40s is usually when earning capacity peaks, but so do expenses. Children need support, so do one’s elderly parents. Only in one’s late 40s and early 50s does one start to see income significantly exceed expenses as the spending needs for either children or elderly parents starts to dissipate. This is peak savings time for an individual and depending on their health, education level, and career success, can last even into their mid-60s. In one’s 60s is usually when one stops working and starts drawing down on the savings they have built up over the previous two decades.

An expanding workforce as a percentage of the population means that a country has the right mix of people at every stage of the skills and income levels.

You need young, hungry people in their late teens and early 20s entering the workforce to do the grunt work, people in the late 20s and early 30s to be the immediate supervisors to those, and then people in their late 30s and early 40s to be the next level up. And finally, we need people in their late 40s through early 60s to be at their peak savings level so that we can generate the capital needed to invest in the expansion of the economy’s productive capacity.

Most importantly, we need the number of people coming into the workforce to be higher than the number exiting and drawing down on their savings so that the amount of capital available for investment is higher than the amount required for consumption. Old people are expensive, and we need a higher number of young people to compensate.

This is the virtuous cycle Pakistan is just at the beginning of: we have more people entering the workforce every year than are being added as dependents to that workforce (either as retirees or as newborn children) and this trend –which started in 1995 – will continue for nearly the entirety of this century.

This is exactly what happened in East Asia in the 1960s through the 1980s, in Europe in the late 1800s, and in the UK in the early 1800s. Reduce infant mortality, start having somewhat few children, and grow the proportion of the population that is available to work and save, and an economy can generate its own path to prosperity.

Where the East Asians and Europeans – and now almost everyone but a handful of countries – have made a colossal error is in assuming that if too many children is a problem to avoid, there must not be such a thing as too few children. There absolutely is, and if a country crosses a certain threshold, there appears to be no turning back and a society continues to age into oblivion.

Take a look at the map of the world with countries above and below the replacement rate of fertility, which is 2.1 children per adult woman. Pakistan is one of a handful of countries outside Africa to have above-replacement fertility levels. Here is another astonishing fact: Pakistan is the largest country in the world to have above-replacement fertility levels. This is not a problem. This is an asset. We delayed reducing our fertility rate, and that delay has been fortunate in helping us see what mistakes to avoid. The East Asian Tigers brag about having gone from Third World to First in just one generation. The generation that did that also does not have grandchildren.

Having worked all their lives to give their children a better life than their own, they will die the last generation to have had more children than their own number, and the last ones to know what it is like to live in a country not slowly dying.

The worst in this regard is South Korea,

which has an age pyramid that is the stuff of nightmares. There are more 50-year-olds in South Korea than there are babies under 1. Its fertility rate is now the lowest in the world at just 0.67, which means that out of every three South Korean households, only one has just one child and the other two have no children at all. By 2060, more than half of South Koreans will be older than 60 years of age.

It may seem like Pakistan is a long way away from these kinds of problems, but as we noted above, it takes more than a generation to turn the tides in demographic trends. Pakistan does not have a problem now, but there is a possibility that our fertility rate will decline faster than the UN projections, a fate that can likely be avoided right now by taking a few simple policy decisions.

It is clear from the fertility data that Pakistanis have now, largely, embraced contraception and family planning. We do not need any campaigns against it, but we can probably have the government stop actively promoting it, and redirect the efforts of the Population Welfare Departments in each provincial government towards reducing maternal and infant mortality.

The sweet spot we should target is a fertility rate that hovers around 2.5 children per adult woman and ideally does not go much below that. This level ensures a slow but steady growth in the population that is likely to be manageable and ensure that the country does not age too rapidly and run the risk of growing old before we become rich.

As women become more educated and take more agency of their reproductive decisions, this will mean accounting for a sizeable number who will choose not to have children, meaning that a norm of three children per child-bearing household would be needed to ensure that average fertility for the population as a whole – including households without children – remains above replacement levels.

We were not wrong to have been taught that Pakistan’s population structure was hampering its growth. We are just wrong to think it still is.

As we will note in next week’s issue, Pakistan is likely poised to be able to capitalise on the demographic dividend that will result from all those children aging into the workforce. The point this week was to note that this happy circumstance can rapidly turn into a nightmare as other countries have learnt the hard way.

We should take advantage of being behind them, and avoid the mistake of not being grateful for the youth of our population, and seek to keep that healthier age structure of the population going for as long as possible. n

Beyond all the talk, are electric vehicles truly

Profit explores the total cost of ownership among various 4-wheeler technologies to ascertain who leads the

By Hamza Aurangzeb

When we envision futuristic technologies, our minds often leap to space travel, AI, and robotics. Yet, just a few decades ago, electric vehicles (EVs) were part of that forward-looking list. Today, while not yet the dominant form of transportation, EVs have steadily moved from science fiction to everyday reality.

The rise of electric vehicles is unmistakable, with consumer familiarity and adoption growing consistently. A Bloomberg Green analysis highlights a significant shift in the automotive landscape: by the end of last year, 31 countries had crossed a crucial EV tipping point, with purely electric vehicles accounting for over 5% of new car sales. This milestone

is considered the gateway to mass adoption, often followed by a rapid transformation in consumer preferences.

Despite this progress, the EV segment faces its share of skeptics. Sales, while on an upward trajectory, haven’t accelerated at the pace many industry insiders anticipated. Around 95% of electric car sales are concentrated in only three regions, China, Europe, and the United States, which have market shares of 60%, 25%, and 10%, respectively. This gap between expectations and reality has led to some pessimism about the sector’s short-term prospects.

However, it’s important to view this transition in context. The shift from traditional combustion engines to electric powertrains represents a fundamental change in transportation technology, one that inevitably faces hurdles and resistance. As with any transformative technology, the path to widespread adoption is rarely linear.

The current state of EVs mirrors a critical juncture: poised between breakthrough and mainstream acceptance. While challenges remain, the increasing global focus on sustainability and technological advancements in battery technology suggest that electric vehicles are likely to play an increasingly significant role in our automotive future.

After considering the global EV landscape, you might naturally wonder: What about Pakistan?

In 2020, Pakistan took a significant step by drafting its National Electric Vehicle Policy, setting ambitious targets. The policy aims for EVs to constitute 30% of new car sales by 2030 and an impressive 90% by 2040. However, the current pace of adoption suggests these goals may be challenging to achieve.

This disparity between policy ambitions and market reality raises a crucial question: Despite government initiatives promoting EVs, do they make financial sense for Pakistani consumers compared to traditional Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) vehicles or hybrids?

To shed light on this important issue, we’ve conducted a comprehensive comparative analysis. Our study examines three vehicle types - electric, hybrid, and ICE - to determine which option offers the best financial value for Pakistani consumers.

Pakistan has a nascent EV industry with limited manufacturing. Some of the electric cars locally manufactured are Seres 3 (DFSK & RP) and Honri EV (BMW).

However, numerous electric cars are

“Since

the total cost of ownership parity has not been achieved in Pakistan for fully electric vehicles, they remain a luxury car, catering to a niche market of affluent individuals for whom a cost-benefit analysis is not a significant decision variable. These consumers, likely already own multiple cars, and are drawn to the novelty and prestige of electric vehicles, driven by a desire for exclusivity, innovation, and status symbolization, rather than purely economic considerations such as fuel cost savings”

Naveen Ahmed, an investment banking professional and advisor for multiple cleantech projects

imported and sold in Pakistan. Some of the leading imported automobiles in the country are Audi e-tron, MG ZS EV, BMW i4, and Hyundai Ioniq 5. As of 2024, approximately 5 million cars exist in Pakistan, however, only a fraction of them are electric. This indicates that Pakistan’s EV industry is not only fledgling but needs government support to flourish. Nevertheless, the absolute size of the Pakistani market makes it a mouth-watering opportunity and a testament to that is Build Your Dreams (BYD), an EV giant based out of China. The company has decided to partner with Mega Motors Company Pvt. Ltd., an associated company of HUBCO, to manufacture electric vehicles in Pakistan. Its presence in the EV industry is likely to boost local manufacturing and expedite the expansion of EVs in Pakistan. Moreover, this new entrant will intensify competition and deliver alternatives to consumers previously unavailable. Although details about prices, models, and battery ranges of cars have not been unveiled, the company will certainly target affluent customers, considering the steep prices of EVs.

Pakistan is a lower-middle-income country with a GDP per capita of $1,680. It is an undisputed fact that luxurious electric, hybrid or even ICEbased cars are inaccessible to the majority of the population. Thus, this analysis is intended for discerning consumers who are considering and are financially capable of purchasing EVs. We have chosen top-of-the-line SUV Crossovers for each category, which encompasses, Honda HR-V VTi-S 2024 (Petrol), Toyota

Corolla Cross 1.8 HEV X 2024 (Hybrid), and MG ZS EV MCE Essence 2024 (Electric). Let us analyze them one by one in detail.

Honda HR-V VTi-S 2024 is one of the most advanced ICE cars in Pakistan. It can be purchased for PKR 7.899 million ($28,413). The car has an engine of 119 HP and a seating capacity of 5 persons. Its top speed touches 200 Km/h; while its fuel tank has a decent capacity of 40 litres. However, it has a low mileage of only 13 Km/l in the city and a high maintenance cost of PKR 25,000 per 5000 Km. Its operating cost comes down to about PKR 21.20/Km, considering its mileage and the price of petrol.

Toyota Corolla Cross 1.8 HEV X 2024 is an advanced hybrid vehicle, it utilizes two power sources, an Internal Combustion Engine and an electric motor powered by a Lithium-ion battery pack. The electric motor enhances the efficiency of the car, resulting in better fuel average and lower carbon emissions. This car is available in Pakistan for PKR 9.849 million ($35,428). It offers an engine of 96 HP and a seating capacity of 5 persons. The top speed of the car is 180 Km/h and its fuel tank has a capacity of 36 litres. It can be maintained by spending PKR 15,000 per 5000 km. It is highly efficient and provides a mileage of 25 Km/l in the city. The operating cost of this car, considering all factors is PKR 11.02/Km. It means that although it is more expensive than Honda HR-V VTi-S 2024, it is more affordable to maintain and drive.

Lastly, MG ZS EV MCE Essence 2024, is a top-notch fully electric vehicle. It is the most expensive out of the three and costs around PKR 12.99 million ($46,726). It is a car suitable for a family of 5. Its features include an engine of 174 HP and a maximum speed of 180 Km/h. This car possesses a battery of 51.1

kWh, which takes around 5 hours to fully charge, assisting the car to cover a distance of approximately 340 Km. Assuming the buyers of this car consume more than 700 units of electricity, the rate of electricity offered to them will be PKR 71.43, which will roughly translate to an operating cost of PKR 10.74/ Km. It has a low maintenance cost of PKR 5,000 per 5000 Km. This means that it is the most expensive out of the three but the most economical one to maintain and drive. Furthermore, electric cars don’t have any direct carbon emissions.

The above section briefed you about the nature of cars, features, and operating costs. However, we will compute the Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) of all three cars in this section, as it will enable us to compare all three cars holistically. While determining the TCO, two components have been considered, CAPEX, the price of the car, and OPEX, which is the sum of maintenance cost and operating cost of 5 years.

We have bifurcated the analysis into two scenarios, which will allow us to conclude systematically.

In this scenario, let’s assume each car covers an average distance of 5000 Km every quarter, approximately 55 Km a day. In this case, the TCO of cars will be as follows:

The CAPEX spent on the Honda HR-V VTi-S 2024 is PKR 7.899 million, whereas its OPEX for the next five years will total around PKR 2.630 million. The sum of both of these values is PKR 10.529 million, which is the TCO for Honda HR-V VTi-S 2024.

The CAPEX of Toyota Corolla Cross 1.8 HEV X 2024 is PKR 9.849 million, while its OPEX will be PKR 1.408 million over the next five years. If we sum both OPEX and CAPEX, we get a TCO of PKR 11.257 million.

In the case of MG ZS EV MCE Essence 2024, CAPEX comes to around 12.990 million, while its OPEX represents a sum of 1.178 million. If we add them together, we get a TCO of PKR

14.168 million, which is the highest in comparison to the rest of the cars.

In the second scenario, the assumption is that each car travels a distance of 100 Km a day or 9000 Km per quarter, almost double the distance compared to the first scenario. The TCO of cars in this situation is given below:

The CAPEX for Honda HR-V VTi-S 2024 will remain stable at PKR 7.899 million but its OPEX will jump to 4.782 million, ballooning its TCO to PKR 12.681 million.

The CAPEX for Toyota Corolla Cross 1.8 HEV X 2024 will remain PKR 9.849 million but its OPEX will become 2.559 million, making its TCO jump to PKR 12.408 million. Its TCO in this case is slightly less than the TCO of Honda HR-V VTi-S 2024.

The CAPEX of MG ZS EV MCE Essence 2024 will remain unchanged at 12.990 million but its OPEX will rise to PKR 2.142 million. This will make its TCO equal to PKR 15.132 million.

The methodology of Total Cost of Ownership suggests that electric 4-wheelers are not economically viable for customers in

Pakistan at this point in time. They not only have to pay exorbitant prices for electric 4-wheelers but their operating costs are only marginally better than hybrid 4-wheelers.

Nevertheless, the operating costs of both electric and hybrid 4-wheelers are half of ICEbased 4-wheelers. If you travel excessively or cover large distances, like 100 Km a day, then the TCO of hybrid 4-wheelers will become less than the TCO of ICE-based for you due to low operating costs.

Notwithstanding, electric cars won’t be able to achieve TCO parity even in this case due to their inflated prices or CAPEX. This indicates that customers who cover a distance of 55 Km or less each day and are driven by cost-benefit analysis should opt for ICE-based 4-wheelers.

However, customers who frequently travel intercity and drive more than 100 Km daily should prefer hybrid 4-wheelers. Therefore, experts believe that the government’s priority should be to make the hybrid segment the preferred choice of consumers at large for the next five to six years as it can utilize the existing infrastructure with minimal modification.

Although electric 4-wheelers fail to make economic sense at the moment, nevertheless, they should not be ignored. There are several advantages to electric 4-wheelers such as significantly lower operating costs, negligible carbon emissions, improved efficiency of cars, and convenience of home charging.

Therefore, customers who don’t priortize financial analysis should consider purchasing electric 4-wheelers. The demand for electric 4-wheelers by affluent members of society will provide stimulus to the local EV industry, spurring it to commence mass production of EVs at better prices, leading to a growth in demand.

“Since the total cost of ownership parity has not been achieved in Pakistan for fully electric vehicles, they remain a luxury car, catering to a niche market of affluent individuals for whom a cost-benefit analysis is not a significant decision variable. These consumers, likely already own multiple cars, and are drawn to the novelty and prestige of electric vehicles, driven by a desire for exclusivity, innovation, and status symbolization, rather than purely economic considerations such as fuel cost savings,” remarked, Naveen Ahmed, an investment banking professional and advisor for multiple cleantech projects.

The most essential component of an electric vehicle is the Lithium-ion battery pack, which plays a pivotal role in determining its price. The

price of Lithium-ion battery packs has declined by more than 80% over the past decade and is expected to decline further. Khalil Raza, an EV expert elaborates that electric 4-wheelers will become economical once the price of Lithium-ion battery packs drops below $70/kWh.

“The Lithium-ion battery pack is the most critical part of an electric vehicle, and its price significantly influences the overall cost of the vehicle. The price of Lithium-ion battery packs has dropped below $120 per kWh and is expected to continue declining in the future. However, it needs to drop below the $70 per kWh mark to make electric cars competitive with ICE-based cars globally as well as in Pakistan,” he reiterated.

There is also a dearth of consistency within the government as it seems to be contradicting itself. On one hand, it introduced a profound framework like the National Electric Vehicle Policy 2020 with ambitious targets for the evolution of the local EV industry, on the contrary, it has retracted several customs duty exemptions on luxury EVs that cost north of $50,000. This rollback of exemptions appears to be an impetuous decision of the government, which should have been delayed for a few years until the nascent EV ecosystem began to flourish in Pakistan.

Scientists and engineers are relentlessly researching to develop Graphene-based and Sodium-based batteries for electric vehicles. According to preliminary research, batteries developed with these materials are cheaper and perform better. Unfortunately, Pakistan is not capable of contributing towards this research and will most likely be an end-user of this technology. However, Pakistan is capable of establishing a rudimentary charging infrastructure for electric vehicles and conceiving standardized processes for local manufacturing of EVs, which will advance their adoption.

Raza believes that facets like EV adoption and infrastructure are intertwined. “Low EV adoption and absence of infrastructure for EVs, serve as a chicken and egg problem, there is no infrastructure because EV adoption is low and vice versa. Thus, the government should erect a basic infrastructure for EVs but not squander by establishing extensive networks, as it requires massive investment,” he opined.

CEO of a local automobile company censured the government’s policies by stating, “The government has increased duties and taxes on EVs in the Budget 2024-25, which would adversely affect their popularity in Pakistan. If the government wanted to increase import duties on EVs, it should have confined its policy to used EVs and excluded new luxury EVs, as the current proposition will be pernicious for automobile companies with a local presence.”

While electric cars seem promising for improving energy efficiency and reducing carbon footprint in Pakistan, significant advancements are required to achieve TCO parity with ICE-based cars and become the preferred mode of transportation in the country.

Furthermore, the restricted EV infrastructure, inconsistent policies, and whimsical economic landscape have exacerbated the situation, hindering a widespread transition to electric cars. Pakistan has made some progress in the realm of EVs but achieving the targets of the National Electric Vehicle Policy of 2020 is nothing short of a far-fetched dream. n

By Abdullah Niazi

You wouldn’t have thought about it, but a lot was riding on the Indian election for Pakistani rice farmers. Let us explain.

Last year, the Indian government found out the country’s rice crop was under threat. This was at a time when food inflation was soaring in India, and shortages were being felt on the market where the prices of rice were very high. The government felt exporters were greedy and wanted to sell on the international market because they got better prices there. To prompt them to sell domestically in the middle of election season, the Modi Administration decided to ban India’s export of rice except for in the Basmati category.

This was a major opportunity for Pakistan, which saw the chance to step up and partially replace India for those countries dependent on external sources for their rice. Except now India is likely to cut the floor price for basmati rice exports and replace the 20 per cent export tax on parboiled rice with a fixed duty on overseas shipments, Indian government sources said last week, in an apparent move to help India retain its market share against Pakistan.

So what happens now?

India is a massive exporter of rice. In 2022, the neighbouring country exported over 22 million tonnes of rice to the entire world. As the single largest exporter of white rice in the world, India control’s a massive 40% of the global market for rice providing different kinds of rice that many other countries in the world are heavily dependent on for their caloric intake.

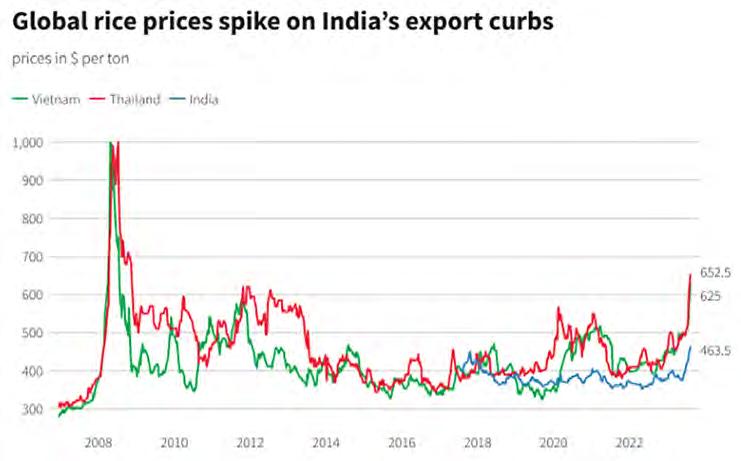

But then came 2023. India nput a ban on the export of all kinds of rice except the aromatic and high-end Basmati variety. The ban comes in response to soaring rice prices in India and a general food inflation crisis that was brewing in the country. As a result,

Last year, India had planned to pull its rice from the international market, creating an opportunity for Pakistani farmers. The party is now over

the international rice market suddenly finds itself short on more than 10 million tonnes of rice. With a global food crisis already about to reach crescendo because of the Russia-Ukraine war, rice importing countries and international organisations are suddenly faced with a concerning question: how will this massive shortfall of rice be met?

The news of India’s rice ban resulted in supermarkets facing panic buying all the way in the United States and other countries that rely on Indian rice. Some other countries that are also exporters may also follow suit with a ban to protect their own domestic markets. It was also an incredible opportunity for Pakistan.

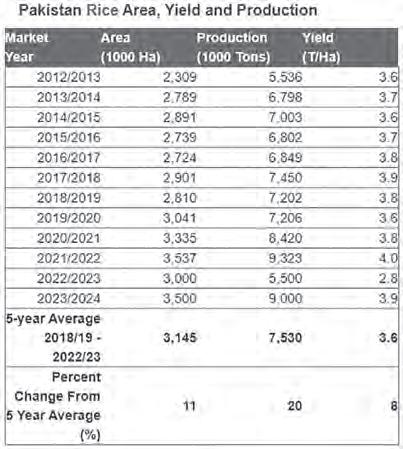

While India might be the largest exporter of rice with Thailand at a distant second place, Pakistan is number four on the list of largest rice exporting countries in the list with Vietnam in the middle at number three. In 2022, Pakistan’s total rice production was just over 5.5 million tonnes and the total export was around 3.5 million tonnes.

China, the Philippines, and Nigeria are primary purchasers of rice. Meanwhile, nations such as Indonesia and Bangladesh, often termed “swing buyers”, increase their imports when facing domestic supply deficits. Rice consumption is not only high in Africa but also on the rise. For countries like Cuba and Panama, rice is a principal energy source. In the previous year, India shipped 22 million tonnes of rice to over 140 nations. Out of this, the more affordable Indica white rice accounted for six million tonnes. For context, the global rice trade is estimated at 56 million tonnes. Thailand, Vietnam and Pakistan,

the world’s second, third and fourth biggest exporters, respectively, have said they are keen to boost sales since demand for their crops has been rising after India’s ban. According to initial reports there is a major role for Pakistan to play in this crisis. But will the Pakistani government bite? Pakistan, recovering from last year’s devastating floods, could export 4.5 million to 5.0 million tonnes according to an official with the Rice Exporters Association of Pakistan (REAP). But already REAP is worried that since food inflation is already pretty high in Pakistan, the government might not be so keen on exporting rice since it will become expensive on the global market.

Sort of. Rice exports from Pakistan for the financial year that just ended last month may touch the 5.8 million tonnes mark mainly because of favourable weather, availability of farm inputs, and the Indian ban on non-Basmati rice exports. Data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics suggests that rice exports crossed the 5m tonne mark in 10 months (July-April FY24), earning $3.4 billion, compared to 3.2m tonne exports worth $1.8 billion made during the corresponding period last year.

It was a pretty simple equation. Pakistani exporters focused on non-Basmati rice and met the shortage that was caused because of India’s ban. As a report in Dawn states, “this phenomenal achievement has been made possible due to a 32 per cent volumetric increase in exports of non-Basmati and a 24pc increase in Basmati. On average, the Basmati export price during the 10 months remained $1,141 per tonne and non-Basmati $573 per tonne.”

The presence of India on the international market is deliberately bleak. Non-Basmati Indian exports nosedived to less than 1m

tonnes in volume this year from 16.4m tonnes a year earlier. Indian rice traders termed the export ban imposed by the Modi government as a political rather than a commercial decision. El Nino, fear of political fallout, inflation and general elections were put forward as the major reasons behind the move despite a more than historical, current buffer stock of 54m tonnes against the approved limit of 14m tonnes. However, Indian Basmati exports touched a new high of 5.2m tonnes from April 2023 to March 2024 (Indian financial year) despite strong tailwinds in the early part of the Kharif 2023 season, such as devastating floods in the Indian Punjab, and strong headwinds, such as the compelling Ukraine war and Red Sea disturbances. Pakistan Basmati rice export during the corresponding period (April 2023 to March 2024) has been 0.73m tonnes which is 14pc of Indian Basmati export. But Pakistan’s per tonne earning was $1,137, which is 3pc higher than Indian price.

But there was a catch to all this. India was always going to be back to take its position as top dog once the crisis was over. This was further exacerbated by the underwhelming electoral results garnered by Prime Minister Modi’s BJP. As a Reuters report points out, Modi is facing a policy conundrum after losing ground in the recent election: how to control food inflation without resorting to export curbs and more imports - steps that have angered farmers, a sizable voting bloc.

After all, the initial ban had been an effort to clamp down on prices, but the measures did not go down well in the countryside, where more than 45% of India’s 1.4 billion people make a living from agriculture. The BJP, which held 201 rural constituencies in the 543-mem-

ber parliament, retained only 126 of them in the mammoth April-May election, according to a voter analysis.

Some decisions are imminent, like easing export curbs on at least two commodities to begin with, the experts said. Other longer-term measures could also be considered, like boosting crop yields and raising government-mandated support prices by bigger margins, they said. The government announced on Wednesday that it would increase support prices that are offered for summer-sown crops, but the raises were unlikely to placate farmers.

This is what it comes down to. The opportunity Pakistan had in 2023 was always going to be a temporary thing. Pakistan cannot come near fulfilling the world’s rice demand. The total shortfall from India’s decision to ban the export of varieties other than Basmati (which is a big seller) has caused a 10 million tonne shortage. Pakistan’s overall production was only 5.5 million tonnes last year. But that was a bad year because of lasting damage and water logging from the 2021 floods.

The rice sector in Pakistan is extremely important in terms of export earnings, domestic employment, rural development, and poverty reduction. Rice is an important food as well as cash crop in Pakistan. It accounts for 3.0 percent of the value added in agriculture and 0.6 percent of GDP. After wheat, it is the second main staple food crop. During 2018-19, rice crop area decreased by 3.1 percent (to 2,810 thousand hectares compared to 2,901 thousand hectares the previous year). The problem is that for any long-term change Pakistan needs to make significant

amendments to its agricultural systems. This year could have been a great opportunity to find new markets for the export of rice but instead Pakistan will only be a stop-gap solution at best because it is uncompetitive.

Despite significant improvement in yield during the 2000s, Pakistan has lost the competitive edge in basmati as indicated by its plummeting shares in total basmati export from 46% in 2006 to less than 10% in 2017, which was conveniently picked up by its competitor India. Pakistani basmati exports also declined by 45% in absolute terms during the period. This declining competitiveness is due to a number of factors that favoured India than Pakistan during the period, including stronger technological innovations which gave higher productivity growth in basmati that have more elongated kernel size without aroma, and lower production costs due to high input subsidies.

According to a 2020 study of the planning commission, for Pakistani rice to become competitive on the international market it needs six interventions: i) gradual shifting to mechanical rice transplanting which is needed for increasing plant population and long awaited productivity enhancement issue of the area; ii) diffusion and adoption of high yielding varieties in the area which is required to replace the varieties like basmati-386, Supra, Supri, etc.; iii) introducing improved crop management practices as large gap between average and progressive farmers’ yield and associated variations in crop management practices can be noticed across farms; iv) shifting to rice combine harvesters which are essentially needed to control harvest and post-harvest losses in milling and address the problem of burning of rice straw; v) introduction of paddy drying at farm level in order to improve the quality of paddy and its by-products; vi) introduction of rice bran oil to diversify rice value chain. n

Pakistan has finally secured a deal with the IMF, but the market does not seem to be reacting the way it should have. Let us find out what other risks Pakistan possesses apart from its financial risk

By Shahnawaz Ali

As Pakistan stands on the precipice of another promised transformation, the threads of socio-economic problems, political unrest, and environmental challenges weave a complex narrative.

The country was able to sign a threeyear deal worth $7 billion with the IMF. But how does that improve Pakistan’s business and economic outlook for the upcoming years? International rating agency Fitch published a comprehensive country risk report answering these questions but are those questions fully answered?

To put this report in the political context of Pakistan, Profit analyses how the numbers fare in the coming years, after the IMF deal. Is it as good as the ruling party claims or is it as bad as the opposition would have the country believe?

There are a host of factors that are taken into account when a country is put to risk assessment. Following is a list of those factors for Pakistan and an estimate of how well does the country fare in these metrics.

The Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) has recently experienced a significant plunge, losing over 1,100 points due to heightened political noise and uncertainty. One would assume that after the IMF deal passed through, the confidence in the country’s financial markets would be strengthened if anything.

However, contrary to that, the market moved the opposite direction in the coming days. And there is only one way in which we

can explain this peculiar behaviour.

The stock market may not be the best indicator of the economy but it is possibly one of the best indicators of investor confidence. And the country;s political landscape does not induce confidence, despite financial security.

To tell this story, the reader needs to have some context of what has been happening on the political front in the last few months. While discerning readers can skip these details, following is a short summary of what the Pakistani political musical chair has been up to.

In a recent conversation on record, Maryam Nawaz, the CM of Punjab asserted that the PML-N government will complete its five-year tenure despite various challenges. The assertion comes as a meek attempt at what seems to be another episode of political unrest not unlike 2022. The supreme court of Pakistan in a majority ruling ruled that the PTI is a parliamentary party of Pakistan and is hence allowed to have reserved seats. This step alone makes the PTI the single biggest political party in the upper and lower house of the parliament, meaning an end to the rule of PMLN and coalition parties.

Moreover the judicial commission has put forward a list of names to appoint ad hoc judges to the apex court of Pakistan, despite the quorum of judges in the SC being full. The JCP and the government state that the appointment of ad hoc judges is to reduce the massive backlog of 57000+ cases pending at the SC. Meanwhile, the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf is almost certain that the decision is being made to revert the reserved seats decision, which is currently 8-5 in the favour of PTI. According to calculations shared by senior PTI leader, Taimur Khan Jhagra on social media, it will take two ad hoc judges more than 114 years to end the backlog of SCP cases.

The political landscape is further complicated by regional security issues, as exem-

plified by a recent blast in South Waziristan targeting a Taliban commander, incidents of terror and civil unrest in Bannu and yet another sit-in orchestrated by the TLP in the country’s capital.

As the judiciary remains a battleground, with the Supreme Court facing intense scrutiny over its decisions on reserved seats and ad hoc judges. The PTI’s open letter to the Judicial Commission of Pakistan (JCP) rejecting these appointments highlights the deep-seated divisions within Pakistan’s political and judicial systems. These conflicts not only stall legislative progress but also undermine public confidence in democratic institutions.

While all this happens in the country causing concerns at a national level. Negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) continue to dictate stringent fiscal measures. While these measures aim to stabilise the economy, they often come at a high socio-economic cost.

The IMF has finally agreed to releasing the funds but the sustainability and inflationary shocks that these funds are going to bring about is expected to be unprecedented, as forecasted by experts. The petroleum levy and electricity duties, sales taxes and taxes on salaried classes have been revised upwards, several times to comply with Pakistan on its international debt obligations.

The government has increased appellate tribunals for tax cases to 100 to improve fiscal discipline. However, it remains to be seen how effectively these tribunals will function amidst bureaucratic inefficiencies and political interference.

In the shadow of all of this, the industrial environment of the country suffers where the exporter and manufacturer find no respite in the increased taxes. Be it the increased withholding charged on the local manufacturer or the Normal Taxation Regime employed on the exporter.

While in an interview with Reuters, the finance minister Muhammad Aurangzeb said that Pakistan needs foreign direct investment to move forward and deposits from friendly countries will no longer cut it.The question that arises is that is pakistan ready to facilitate the FDI and protect the interest of the foreign investors in this high taxation environment.

In this respect, the upcoming installation of a plant by the world’s largest bus maker “Yutong” in Karachi marks a positive stride. This development, expected to be completed within the next year, promises to boost local employment and enhance industrial capabilities. However, sustainable industrial growth requires consistent policy support and a stable economic environment, factors that are currently in flux.

The Fitch report on Pakistan’s risk profile highlights one thing that is of extreme importance. A heatwave in the last month has led to calls for exemptions from traditional black coats for lawyers, underscoring the country’s urgent need for climate-responsive policies. This situation is a microcosm of the broader environmental challenges Pakistan faces, including water scarcity, air pollution, and the impacts of climate change on agriculture.

The country is vulnerable to any kind of environmental disasters with the most recent example being the 2022 floods. In 2023, Pakistan got the global community to pledge upwards of 10 billion USD in climate action aid, however that money is nowhere near being realised.

The projection that Pakistan’s population is likely to double by 2050 adds another layer of complexity to the country’s socio-economic fabric. This demographic surge will place immense pressure on infrastructure, healthcare, and education systems, demanding proactive and sustainable planning from policymakers.

With the development budget facing cuts year in and year out and the rest of it

being used to fulfil political goals. This is probably going to be one of the most concerning aspects in the decades to come, adding to the potential risks for long term investment.

The recent murder of journalist Hassan Zaib has sparked international outrage, highlighting the perilous conditions under which journalists operate in Pakistan. Sadly this is not the first time the country has been found to shun human rights injustices.