16 26 08

16 26 08

08 Has the power crisis finally brought the telecom industry to its knees?

12 The state of solar energy in Pakistan

16 After making losses for half a decade, Telenor Bank is finally out of the red

21 Competition in the dishwashing segment remains non-existent. How did Lemon Max manage it?

24 Millat Tractors’ 10-day shutdown: the story behind the decision

26 For the past five years, the HBL PSL was the PCB’s biggest source of revenue. It no longer is.

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz Khan - Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Editorial Consultant: Ahtasam Ahmad - Business Reporters: Taimoor Hassan | Shahab Omer

Zain Naeem | Saneela Jawad | Nisma Riaz | Mariam Umar | Shahnawaz Ali | Ghulam Abbass

Ahmad Ahmadani | Aziz Buneri - Sub-Editor: Saddam Hussain - Video Producer: Talha Farooqi Director Marketing : Mudassir Alam - Regional Heads of Marketing: Agha Anwer (Khi) Kamal Rizvi (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) - Manager Subscriptions: Irfan Farooq

Pakistan’s #1 business magazine - your go-to source for business, economic and financial news. Contact us: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

The escalating cost of powering the tower infrastructure has become a hindrance to the progress of telcos, do they have a work around?

By Hamza Aurangzeb

In the early 2000s, Pakistan’s landscape began to change. Tall metal structures started popping up across the country, from bustling cities to remote villages. These weren’t new buildings or monuments, but something that would

transform the nation: cell phone towers. At first, these towers were a sign of progress. Telecom companies raced to build them, each trying to cover more ground than their rivals. It was an exciting time. People in far-flung areas could suddenly call their loved ones. Farmers could check crop prices from their fields. Students could access the internet

for their studies.

But as the years went by, something strange began to happen. The very towers that had brought so much change were becoming a problem. The telecom companies that had built them with such enthusiasm were now looking at them differently. These steel giants, once a source of pride, were turning into a headache.

What went wrong? How did these symbols of progress become a burden? The answer lies in a story of ambition and unexpected challenges.

In the mid-2000s, as telecom companies entered the Pakistani market, they faced a unique battleground. Rather than engaging in a price war, these newcomers found themselves competing on an entirely different front: network coverage. This shift in focus was driven by the country’s glaring lack of telecommunications infrastructure.

The period from 2004 to 2008 marked an era of aggressive investment. Telecom giants poured billions into building the nation’s digital backbone from the ground up. Their goal was clear: to make their networks as ubiquitous as possible. This infrastructure was not merely an asset; it was the key to expanding their reach and, by extension, their customer base.

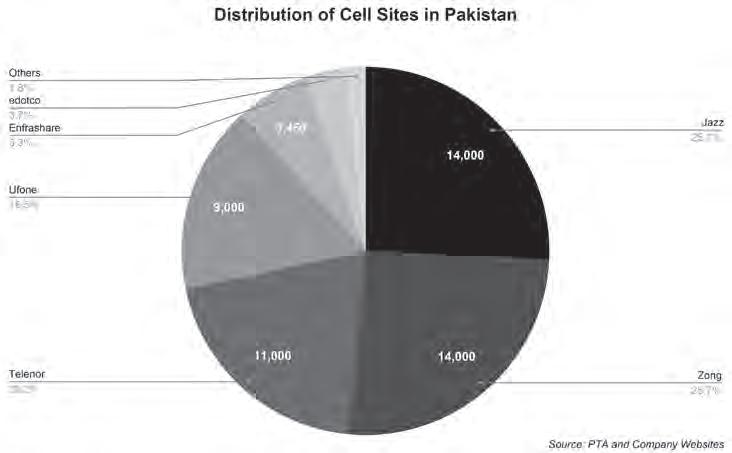

Fast forward to June 2023, and the landscape tells a story of rapid growth. According to the Pakistan Telecommunications Authority (PTA), the country now boasts approximately 54,415 cell sites. The market leaders, Jazz and Zong, are locked in a tight race, each commanding around 14,000 sites. Telenor follows closely with 11,000 sites, while Ufone rounds out the major players with 9,000 sites to its name.

However, the once-prized tower infrastructure, which telecom companies raced to build in the mid-2000s, has transformed from a strategic asset into a growing liability.

The root of this transformation lies in the industry’s shifting revenue dynamics. Over the past decade, the proliferation of fast,

affordable data packages has dramatically altered the market, cannibalizing traditional revenue streams. This shift has led to a troubling trend in Average Revenue Per User (ARPU) for both voice and data services.

Between 2019 and 2023, the industry witnessed a mere 1.1% annual growth in ARPU when measured in Pakistani rupees. More alarmingly, when calculated in U.S. dollars, ARPU plummeted by 12.4% annually during the same period. Today, it hovers around a meagre Rs. 249 or 90 cents - a stark contrast to the $9 ARPU that telecom operators enjoyed upon their mid-2000s market entry.

This financial squeeze has inverted the economics of tower ownership. While ARPU remains stagnant at best, the cost of maintaining and operating these towers continues to spiral upward at an alarming rate. The challenge is further compounded by Pakistan’s ongoing energy crisis. Telecom towers,

voracious consumers of electricity, now face a double-edged sword: skyrocketing power costs and frequent outages.

In the past, operators could rely on diesel generators during load-shedding periods. However, with fuel prices soaring, this backup solution has become economically unsustainable. The confluence of these factors - stagnant revenue, rising operational costs, and an unreliable energy supply - has created a perfect storm for telecom operators.

This new hurdle has sent shockwaves throughout the sector, affecting a wide spectrum of players from technology-driven telecom companies and Cellular Mobile Operators (CMOs) to tower companies. The impact on profitability has been particularly pronounced since 2022, painting a concerning picture for the industry’s future.

Let’s examine this trend through the lens of several key players.

Jazz, a market leader, took a strategic approach to this challenge. In August 2016, it created a subsidiary named Deodar, transferring ownership of all its sites to this new entity. This move was to materialise Jazz’s ambition of becoming an asset-light company through selling its tower assets and leasing them back, a dream that hasn’t come true till date.

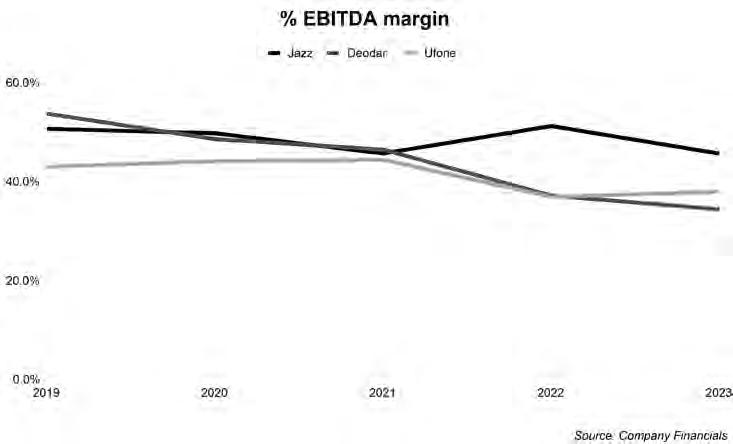

And recent trends also suggest why this would have been a wise move if executed. In 2023, its EBITDA margin stood at 45.6%, whereas its five-year average is around 48.6%.

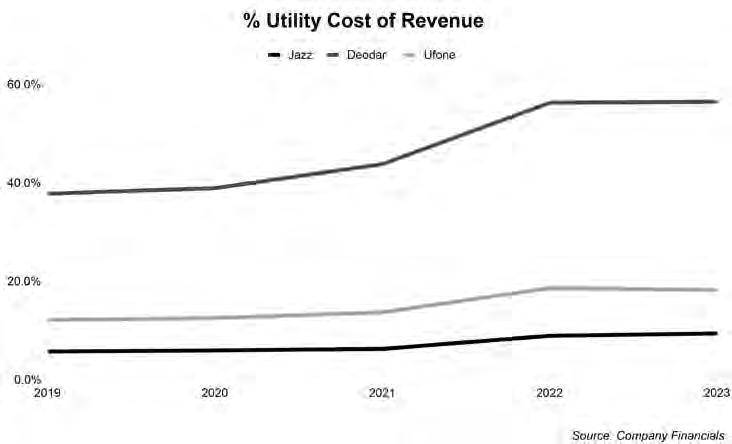

More alarmingly, its cost of utilities as a percentage of revenue surged from 6.3% in

2021 to 9.4% in 2023 - a significant jump that underscores the growing energy crisis.

Deodar’s standalone financials tell an even more stark story. Its EBITDA margin plummeted to 34.4% in 2023, far below its five-year historical average of 44.1%. Perhaps most concerning is the explosion in utility costs (primarily energy costs), which now exceed 56.5% of revenue, up from 43.8% just a couple of years ago.

“Energy costs have significantly risen in recent years due to increases in fuel and electricity prices. This surge has led to a higher percentage of total revenue being spent on energy. Despite requests for a shift to more favourable energy tariffs for telecom companies, the issue remains unresolved, with telecom towers and data centres still charged at higher commercial rates.” Jazz expressed their stance in the following words.

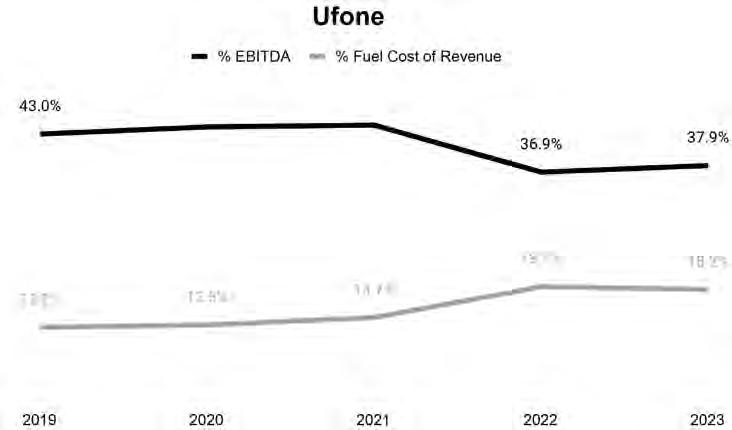

This troubling trend isn’t isolated to Jazz and Deodar. Ufone, operating under the PTCL umbrella, shows similar signs of strain. Its EBITDA margin dipped to 37.9% in 2023, down from a five-year average of 41.3%. Fuel and power costs have ballooned to 18.2% of revenue, up from 13.7% in recent years.

Even dedicated tower companies aren’t immune. Engro Enfrashare, a fully-owned subsidiary of Engro Corporation Limited, saw its EBITDA margin contract from 64.5% in 2022 to 60.5% in 2023, primarily due to escalating operating costs dominated by energy expenses.

These examples illustrate a pervasive trend across the telecom landscape. Rising energy costs and shrinking profitability are industry-wide phenomena, not isolated to any single company or business model. While these mounting energy costs haven’t yet dealt a fatal blow to the telecom sector, they’re undeniably eroding EBITDA margins across the board.

These escalating costs coupled with a broader shift to a ServiceCo model across the telecom sector have propped up demand for telecom infrastructure-sharing in recent years, where third-party operators manage a portfolio of tower assets that are rented out to various telcos. This scheme not only reduces the cost of operating tower infrastructure but also enhances network coverage and service quality. Moreover, it advocates for infrastructure optimization, which is eco-friendly.

The business model of tower companies can be bifurcated into segments, the first one is Sale and Leaseback, where companies purchase and upgrade existing infrastructure, and then rent it out, while adhering to the second segment, Built-To-Suit, companies strike deals

with telcos to construct towers from scratch and maintain them. The tower companies reserve ownership of the passive infrastructure, while Mobile Network Operators (MNOs) own active infrastructure like antennae and wireless technology.

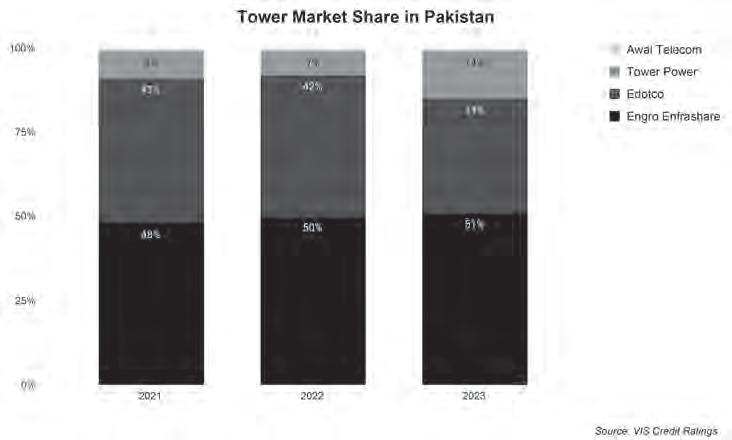

The tower infrastructure market in Pakistan is dominated by four major stakeholders, which have cemented their spots over the past few years. These companies include Engro Enfrashare, Edotco Pakistan (Pvt) Ltd, Awal Telecom, and Associated Technologies (Pvt.) Limited (now under the ownership of Tower Power (Pvt) Limited). As per the statistics of VIS credit ratings, 6,000 tower sites are operated by such tower companies.

The escalating energy costs, as mentioned before, are also affecting these companies. So how can TowerCos and the industry in general prevent this situation from deteriorating further? The solution may mirror what many household energy consumers have already discovered.

Although telcos have initiated tower sharing and outsourcing onus of managing infrastructure, however, it is a gradual process which will take several years to mature. Hence, the story of optimization does not end here, telcos themselves along with tower companies are transitioning towards renewable energy to power their tower sites.

According to the Renewable Energy for Mobile report by GSMA, the telecom industry has unanimously decided to move towards renewable energy, as it not only lowers operational costs but has also become cost-competitive with diesel generators, especially when the capital expenditure of both systems is spread

over four to five years.

As per the estimations of the Alternative Renewable Energy Board, the mobile tower industry consumes around 1.2 billion litres of diesel, annually, roughly equivalent to Rs. 315.3 billion ($1.1 billion). This could be accredited to the precarious nature of the national grid, which witnesses frequent power outages, therefore, companies resort to diesel generators. However, this practice takes a toll on the operating costs of the companies and is deleterious to the environment. Hence, an off-grid reliable energy resource is the need of the hour for telcos, which is where solar energy comes in, an abundant natural resource in Pakistan that would serve as an adequate solution.

Numerous telcos and tower companies have launched renewable energy initiatives including Telenor Pakistan, which inaugurated its campaign of solarizing tower sites in April 2022 and has successfully converted about 225 sites, thus far. It has improved the operationality of converted tower sites by 3.9%, shrunk diesel consumption by 3 million liters, and decreased energy operating expenses by 4.9% in 2023, leading to a strengthened bottom line.

Similarly, tower companies like Engro Enfrashare have established a portfolio, where 46% of tower sites are powered by solar energy, which allows the company to tackle uncertainties related to oscillating fuel prices and frequent disruption of the fuel supply chain in the country.

Energy costs are also a major concern for tower companies like Edotco. Therefore, they are utilising solar panels to power their tower sites. The company’s 200 mobile towers, which have a capacity of 2 MW are powered by solar panels and it plans to augment its solar capacity to 5 MW by 2025. Moreover, companies such as Ufone are also evaluating the feasibility of renewable sources like solar energy to manage their energy costs efficiently.

Therefore, it is evident that the Telecom giants are feeling the squeeze as energy costs soar, taking a big bite out of their profits. But they’re not throwing in the towel just yet. Instead, they’re getting creative, teaming up with tower companies and embracing green energy to give their infrastructure a smart makeover. This move promises to slash operating costs and pump up profits.

But as these big players step off the national grid, another chunk of premium high-paying customers would be exiting the utility network. And in this high-stakes game of energy musical chairs, it looks like the government might be the one left standing when the beat stops. n

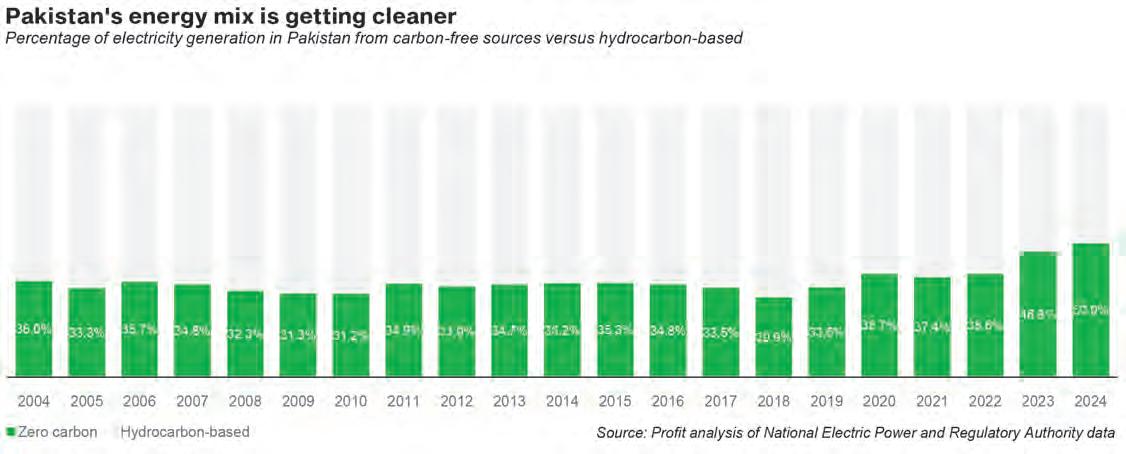

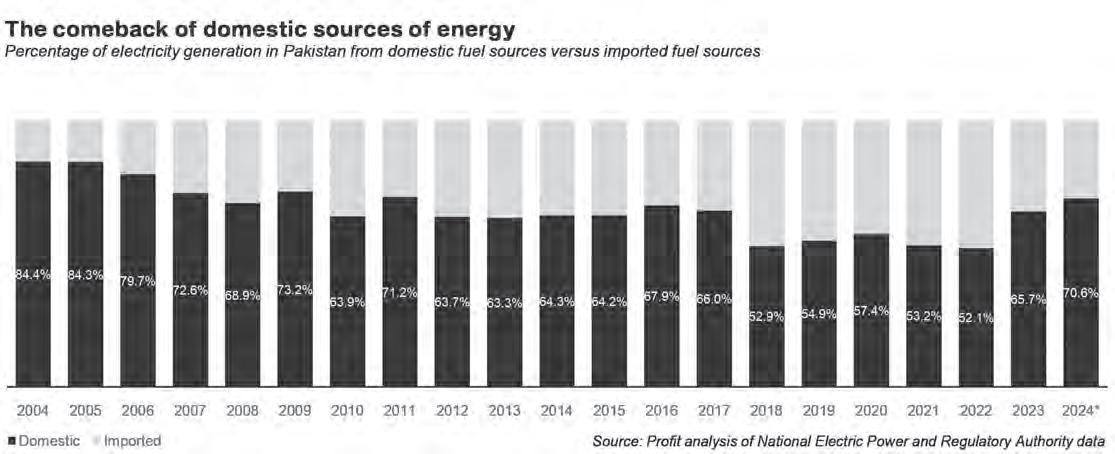

Distributed power generation is hitting the country’s grid, making the energy mix cleaner, but also making it harder to run the already unwieldy national grid

EBy Farooq Tirmizi

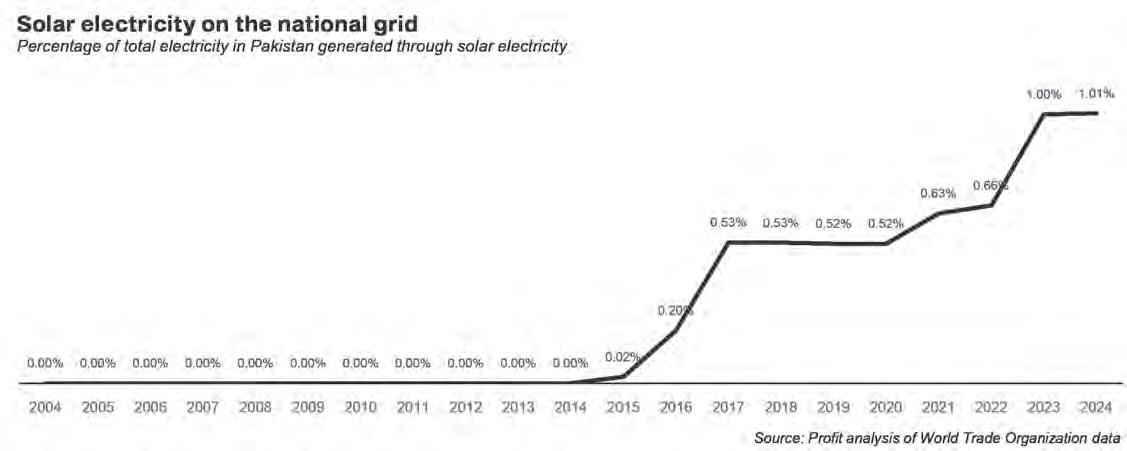

xactly how much solar electricity does Pakistan produce? The answer to that question should be quantifiable, but somehow is not so readily available. And while the plural of anecdote is not data, there does seem to be some indicate this much: solar electricity in Pakistan may not be a dominant source of electricity yet, but is already big business, and is likely even bigger than we know so far.

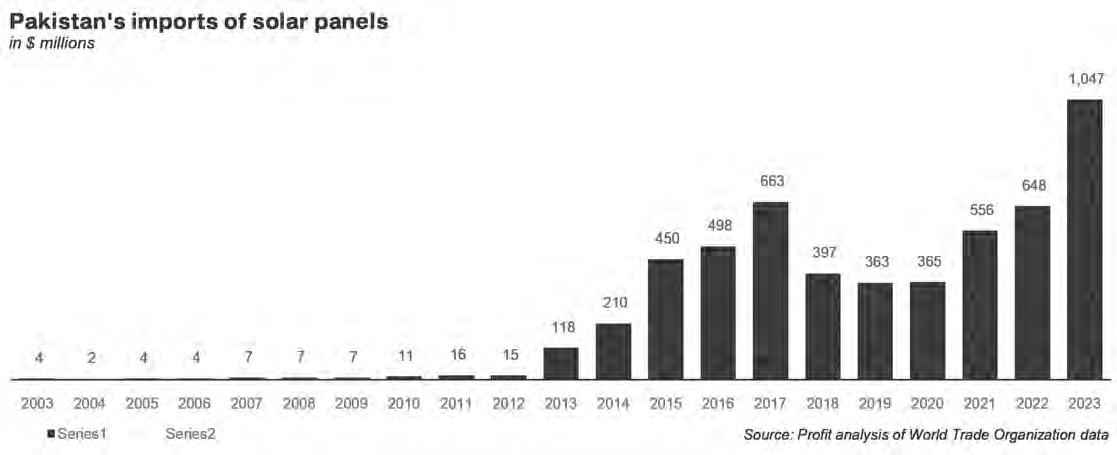

The mystery starts with a single number: in the calendar year 2023, Pakistan imported $1 billion worth of solar panels, nearly all of them from China. And while there are many grid-scale solar power plants currently being set up in Pakistan, even all of them combined should not cost anywhere close to requiring $1 billion worth of imported solar panels to complete construction.

Meanwhile, data from the National Electric Power Regulatory Authority (NEPRA) indicates that while solar electricity is among the fastest growing sources of electricity in Pakistan, it is nowhere nearly as big as to justify those kinds of number for imports, especially at current prices, when one can import solar panels from China for as little as $0.11 per watt.

So, what is happening? Is the government right that the power consumption data for the national grid is declining because more and more people are moving off the grid and using their own solar panels? Or does the data that indicates that rooftop solar is still a very small niche in Pakistan the more correct view?

A closer examination of the data suggests that the trade figures are probably exaggerating the extent of how many solar panels are being installed in Pakistan, but just because solar electricity is not as big as the import data may suggest does not mean it does not have important implications for the government’s energy policy, and in particular its push towards privatization of the electricity distribution companies.

But before we get into that, let us examine the state of play for solar energy in Pakistan.

(One big note: we would like to state at the outset that this article will not contain the customary “but Pakistan has so much potential” bloviating about how much solar electricity the country could be generating. This will be focused much more clearly on what is actually happening. It is much more interesting to describe what actions people are actually taking rather than engage in the wistful daydreaming about potential.)

The total installed capacity for solar electricity in Pakistan – as measured by NEPRA – is about 732 megawatts, which is about 1.6% of the total installed capacity. This number is at least somewhat of an underestimate, since only the privately owned K-Electric keeps track of the capacity of the rooftop solar panels to which it offers a grid connection (about 102 megawatts as of 2023). The state-owned elec-

tricity distribution companies (DISCOs) do not publish that data and instead only count grid-scale solar electric power plants.

Beyond the currently active capacity, there are grid-scale solar projects for another 150 megawatts currently under construction, and another 230 megawatts that are under varying stages of regulatory approval. In other words, solar energy generation capacity is increasing, but hardly by the leaps and bounds that would be indicated by the import data.

During the fiscal year ending June 30, 2024, provisional data from NEPRA indicates that about 1% of the electricity produced by the national grid came from solar energy. This does not mean that only 1% the total amount of electricity consumed in the country was from solar energy, however, since a substantial portion of solar electricity in Pakistan – about half, by our estimates – never hits the national grid at all and is instead consumed by the household or business that installed it on their own rooftop. So the real percentage of electricity consumed in Pakistan that comes from solar energy is probably closer to 2%.

This number does not sound high at all, until you consider the fact that as recently as 10 years ago, the total proportion of electricity in Pakistan that came from solar was close to zero. To go from 0% to 2% in less than 10 years – with its high upfront installation costs in a country with low purchasing power – is no mean feat.

But 2% does mean that the government’s claims that the national grid is producing less electricity because too many people are switching to rooftop solar is very likely untrue:

So how big is rooftop solar in Pakistan? Well, K-Electric estimated that in 2023 – the latest year for which data is available – the amount installed in its jurisdiction was around 102 megawatts. The state-owned DISCOs do not publish similar data, but they do indicate how much electricity they buy from rooftop solar panels through net metering agreements. If we assume a similar utilization level of those panels to the ones in Karachi, we arrive at an estimate of about 192 megawatts in rooftop solar installed outside Karachi, or about 294 megawatts in the whole country.

The implication of this number is the following: total installed capacity for solar electricity in Pakistan is around 924 megawatts and of that, total rooftop solar is about 292 megawatts, or less than one-third. The utility companies and the state-owned power companies still account for over two-thirds of solar electricity generated in Pakistan.

This particular point is worth dwelling on: the common perception of solar electricity in Pakistan is that of upper middle class households – and a few factories – installing

solar panels on their rooftops and using most of the electricity thus generated for themselves. The reality, however, is that the bulk of solar electricity in Pakistan, and indeed most countries, comes from large scale solar panels installed by power generation companies in deserts.

Why is this the case? The fact that the cost of solar electricity is almost entirely upfront makes it prohibitive for consumers who are not financially well off, despite the fact that it is now possible to buy solar panels in many Pakistani cities for as little as Rs40 per watt.

Distributed generation could eventually become a very important phenomenon, but it is not quite there yet, even though the economics have been trending heavily in that direction.

The notion that one-third of rooftop solar capacity in Pakistan is installed in Karachi also makes sense. It is the kind of thing that requires a high level of income, and the concentration of that portion of Pakistan’s upper middle class is higher in Karachi than other cities.

The NEPRA data, in other words, is quite internally consistent: none of the data points are rendered nonsensical by the existence of the other data points. So what on earth does the trade data mean?

Here is why we think the trade data is unreliable: if the data is an accurate representation of reality, at the 2023 prices of solar panels in China – $0.11 per watt, according to consulting firm Wood Mackenzie – having imports worth $1 billion would imply that Pakistan was installing roughly 9,500 megawatts of solar electricity, which would represent a nearly 21% increase in the country’s electricity generation capacity.

That is almost certainly not happening. The numbers get even more ridiculous if you were to use historical average prices for each year of imports and try to estimate the amount of installed capacity. Since 2013, if the import numbers were accurate, that would mean Pakistan imported 21,000 megawatts of solar power generation capacity, or a 46% increase in capacity. While the government’s estimates for solar electricity are probably at least slightly off, they are exceedingly unlikely to be off by quite so much.

The likeliest explanation is an unsavory one: that importers are misclassifying goods they are importing from China as solar panels so that they can take advantage of the near-zero import taxes on solar panels. That policy was put in place to encourage

investment in renewable energy so as to help Pakistan meet its goals toward mitigating climate change.

But creating differentials in import tariffs does create the incentive to try to use the tariff-free classification for products that would normally carry taxes and tariffs. And in Pakistan at least, one can always count on a sufficient number of officials at Customs to be willing to go along with these kinds of schemes in exchange for a sufficiently large bribe.

To be clear, we have no evidence of any wrongdoing by any specific individual or even specific government department. But the data is simply too nonsensical to ignore: it is very, very unlikely that all $1 billion worth of the goods being imported into Pakistan and classified as solar panels are, in fact, just solar panels and nothing else.

But here is why distributed generation still matters. Electricity consumption is very heavily power law distributed, meaning that the top few users of electricity converting from the grid to solar electricity can have a very large impact on the national grid. This is best illustrated with an example.

Consider the case of K-Electric, for example. While K-Electric has 2.5 million customers spread throughout Karachi, about 40% of its revenues come from just 2,500 of its top industrial customers. In a city like Karachi, where theft takes away about 20% of revenue for an electricity company, it is vital to know that focusing on just 2,500 customers

can ensure that 40% of their revenue is safe. What happens if those bigger customers start installing solar panels? The largest, most profitable of K-Electric’s customers are also ones who are most likely to start generating their own electricity for a substantial portion of the day and even selling electricity back to the utility.

As more of the wealthier consumers – both domestic and industrial – shift to alternative energy, K-Electric would be left with the smaller, less profitable customers, typically in areas with theft rates that can often be up to four times higher than in the more affluent neighbourhooods. Not only would its addressable market shrink, but the utility would be left with the most bothersome portions of its customer base.

Now, K-Electric is already a privately owned utility company, but imagine what

would happen if you play out this scenario at the state-owned Lahore Electric Supply Company (LESCO) or the Faisalabad Electric Supply Company (FESCO).

Both companies are being considered as candidates for privatization, and any potential buyer of these assets will likely want to run the same playbook that K-Electric did: defend your revenue by first securing billing from the largest customers, and then work your way up the level of difficulty, in order to eventually reduce the line losses due to theft.

The more the largest customers move towards alternative energy sources, the more difficult it will be for any prospective buyer to figure out a path to sustainable profitability for the company they are about to buy. Not impossible, but certainly more difficult.

As we stated above, however, most solar electric power generation capacity is current-

ly still being installed in grid-scale projects that are – from a utility company’s financial perspective – no different than traditional thermal power plants.

And the assumption that distributed generation is bad for utility companies rests on the idea that it is not possible to create contracting arrangements between households and businesses that want to install rooftop solar panels and the utility company that would provide them with a grid connection for when their panels do not produce enough electricity.

The problem is admittedly a hard one to solve, particularly for utility companies like those in Pakistan which not only have a large fleet of thermal power plants, but also have an overcapacity of them. People who install rooftop panels want the utility company to maintain that large fleet and its capacity for

when the sun is not shining, but maintaining a lot of idle capacity is expensive, which would drive up the price of grid electricity, which in turn would motivate even more people to opt for rooftop solar, which then would drive up costs even more, creating a vicious cycle of escalating tariffs.

It is unlikely that Pakistan is headed in that direction, much as the government would like to find someone to blame for its abysmal national energy policy which has resulted in Pakistan facing two successive fiscal years in which total electricity consumption has declined (by 10.1% in 2023, and 1.2% in 2024), causing the proportion of people’s electricity bills that comes from capacity charges to increase.

Solar electricity in Pakistan is clearly big business, but it is nowhere nearly big enough – certainly not yet – to become a meaningful threat to the national grid. n

After making losses for half a decade, Telenor Bank is finally out of the red

One of the first players in Pakistan’s microfinance industry appears to be finding its footing at last. It turns out the key to profitability was shrinking its balance sheet

By Mariam Umar

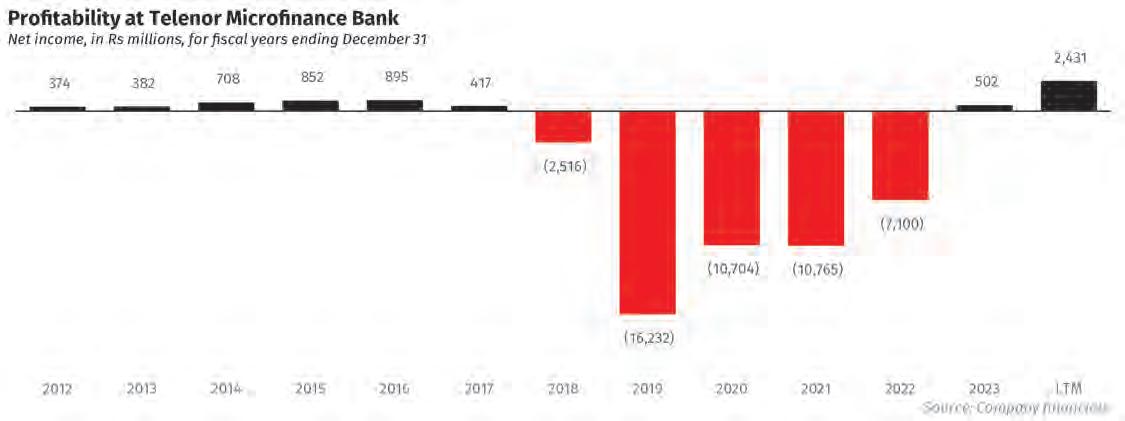

The key to sustainable growth is not trying to do much too fast. That is the lesson that Telenor Microfinance Bank appears to have learnt the hard way, though it looks like they are learning it at long last. The year 2023 was when the bank finally turned a profit after five long years deep in red, and the year 2024 seems to be off to a flying start, suggesting that last year was not a fluke.

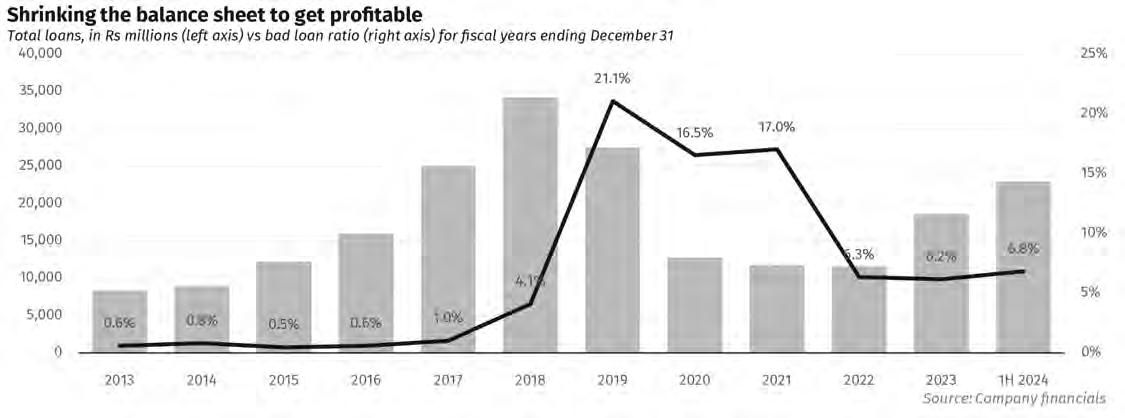

For the 12 months ending June 30, 2024, the latest period for which financial statements are available, the bank earned a net income of Rs2,431 million, up almost five-fold from Rs502 million for the calendar year 2023. What makes this extraordinary is the fact that the bank’s lending book is one-third smaller than it was at its peak in 2018, when its streak of losses began.

Will this return to profitability off a small balance sheet be the right approach? And will this finally result in the bank’s long-suffering shareholders making adequate returns on their investments? It is too early to answer these questions definitively, but the indications so far look encouraging.

Telenor Microfinance Bank started its existence as Tameer Bank in September 2005. It was founded by Nadeem Hussain, a former Citibanker, who sought to bring the financial discipline and scale that comes from being a corporate entity to the nascent microfinance industry that had hitherto mainly been a quasi-charitable enterprise. In its first year, Tameer Bank saw success with zero delinquencies, operating 15 branches in Karachi and serving 20,000 customers. The bank anticipated breaking even by its third year.

However, challenges arose in the second year as delinquencies surged to 25%, driven by poor loan recoveries. The bank faced increasing operational costs and defaulted loans, prompting Hussain and other sponsors to inject additional capital and expand operations beyond Karachi. To scale sustainably and minimize lending risks, Tameer Bank started lending to farmers and individuals against gold jewelry as collateral. Since the bank physically kept custody of the collateral, this approach allowed

the bank to build its loan portfolio without jeopardising its equity.

However, the sponsors soon realised that relying on traditional brick-and-mortar operations would impede their ability to achieve scale. Given the small loan size, it was simply not possible for a single branch to raise enough revenue to justify the expense of running it. As a result, Hussain turned to the uncharted territory of branchless banking, where he found the solutions he seeked.

Fortunately, for Hussain and his sponsors, the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) and Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) were also flirting with the idea of branchless banking around the same time.

After much deliberation, the SBP issued branchless banking regulations in 2008. These regulations also led to the telcos’ adventure into the microfinance sector as it presented an opportunity for the telcos to collaborate with banks to launch mobile financial service products in the country.

In its third year of operations, Tameer Bank began negotiations with Telenor Pakistan, which sought a microfinance license by acquiring an existing bank rather than starting one. At the time, Tameer Bank’s capital had dwindled to abysmal levels, and liquidity issues were mounting due to slow turnaround. The bank needed a deal within 3-6 months or would face another capital raise.

Telenor Pakistan, meanwhile, was also struggling to find new ways to boost revenue, with its average revenue per user (ARPU) dropping from $15 to $2 (largely due to expanding its market share dramatically, albeit by serving customers with a far lower ability to pay). Despite investing $1-1.5 billion in infrastructure, merchant networks, and licenses, Telenor’s voice services were not profitable, pushing it toward financial services as a means of monetizing its customer base.

After protracted negotiations, Telenor acquired a 51% stake in Tameer Bank. In 2009, the bank and Telenor Pakistan jointly launched Easypaisa, Pakistan’s first branchless banking solution. By 2016, Telenor had acquired the remaining 49% stake, making Tameer Bank a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Norway-based telecommunications company. Easypaisa was transferred fully to Tameer Bank in 2017, and the bank was rebranded as Telenor Microfinance Bank.

Telenor Bank found its ownership structure changing once again in November 2018 when Telenor Microfinance Bank entered into

a strategic partnership with Ant Financial Service Group, the financial services subsidiary of Chinese e-commerce giant Alibaba. The bank received capital injections from Ant Financial worth $184.5 million, through its investment arm Alipay resulting in Ant Financial holding a 45% share in Telenor Bank by the end of 2019 while Telenor Pakistan B.V. still holds the remaining 55% share. The investment by Ant Financials was considered one of the biggest in the fintech space of Pakistan back then.

You might think that with this much money coming in, the bank would be performing really well. But that is not the case. Between 2018-2022, the Telenor Bank found itself in red due to four key reasons.

Firstly, with the advent of a new investor on board, the bank’s strategic direction shifted towards expanding Pakistan’s digital ecosystem by tapping the mobile wallet market potential through Easypaisa. In line with this shift in strategy, the bank introduced Easypaisa loans in 2018, which was the country’s first-ever digital nano loan. As the bank changed its strategy, the bank had to incur increased marketing expenses to increase its digital footprint which resulted in escalated administrative costs and affected the profitability ratios.

Secondly, Telenor Bank had an impressive record for almost a decade primarily due to the success of Easypaisa, which was effectively a monopoly for a long time. However, competition picked up when Mobilink Microfinance Bank started to invest heavily in Jazzcash aiming for the market leader position in the mobile wallet space which it eventually got by the end of 2018, according to Karandaaz Data Portal.

Thirdly, in 2019, the bank unearthed massive employee fraud resulting in heavy loan defaults. The fraudulent loans resulted in huge losses. In 2019, Telenor Bank had accumulated losses of around Rs16.6 billion.

Fourthly, just when the bank was struggling with fraudulent loans, the bank’s loan book was hit by yet another calamity –the COVID-19 pandemic. Lockdowns halted business activity. Microfinance institutions, like Telenor Bank, provide small loans to a target audience that is not the most affluent in society. These are loans that could be provided to someone to open a shop for their trade such as to a barber or a carpenter.

Unfortunately, these were exactly the

people most impacted by the lockdowns with their small businesses being closed for months. This meant the microfinance sector was caught in a fix as the majority of its borrowers were not in a position to pay their loan instalments immediately. The pandemic took a toll on the bank’s loan portfolio as the industry-wide non-performing loans grew due to an economic slowdown.

Consequently, Telenor Bank’s infection ratio—the percentage of non-performing loans relative to its total gross advances—skyrocketed from 4% to a staggering 21% in 2019. This dramatic increase highlighted the severity of the bank’s financial challenges during that period. It wasn’t until 2022 that Telenor Bank began to regain control, successfully bringing the infection ratio down to single digits.

At the same time, the State Bank’s decision to abolish interbank fund transfer (IBFT) charges in 2020 also added to Telenor Bank’s woes as its main source of branchless income was affected. Between 2020-2022, the

bank made losses on its branchless banking operations.

In 2020, the bank suffered a loss of Rs230 million from branchless banking which more than doubled to Rs541 million in the next year. In 2022, the loss increased to Rs1.5 billion. The fraudulent loans contributed to more than half of the losses the bank experienced between 2019 and 2021.

To counter massive losses, Telenor Bank restructured its books. The bank cleaned up its lending portfolio, wrote off loans, and exited the agriculture bullet lending business where most of the fraud had occurred.

“In the process, we had to take an impairment charge on the lending portfolio of roughly Rs14-15 billion,” said Mudassar Aqil, who was then the CEO of Telenor Bank, in a previous conversation with Profit. Telenor Group and Ant Financial, funded the impair-

ment loss which gave the bank a clean slate to establish the business once again. The bank’s sponsors invested over $100 million more equity into the business, of which $45 million were injected in 2020, followed by a $70 million injection in 2021.

In 2022, a further $37 million was injected to pursue a digital-first strategy as the bank also applied for a digital retail banking (DRB) license. Telenor Microfinance Bank (Easypaisa) is one of the five recipients of the DRB licence.

It was granted in-principle approval in September 2023. According to an industry source, much of this development hinged on the technology and commitment of Ant Financial Group which prompted the SBP to grant the license. In line with this shift, the bank closed down many of its branches. Total number of branches halved down from 103 in 2018 to 48 at the end of 2023.

Meanwhile, Telenor Group, the primary sponsor of Telenor Bank, announced in late

2021 that it was exploring the sale of its 55% stake in Telenor Microfinance Bank in Pakistan due to mounting losses. Despite previous unsuccessful attempts to sell the bank, industry sources suggest that Telenor will continue seeking buyers.

However, since Easypaisa, a subsidiary of Telenor Bank, received a DRB license, the SBP may resist a sudden ownership change as that could reflect badly on the prospect of digital banking, which would mean that Telenor Bank will continue with its transition towards digital banking and then in a few years Telenor Group may sell its shareholding, contingent upon the terms of the deal and available partners.

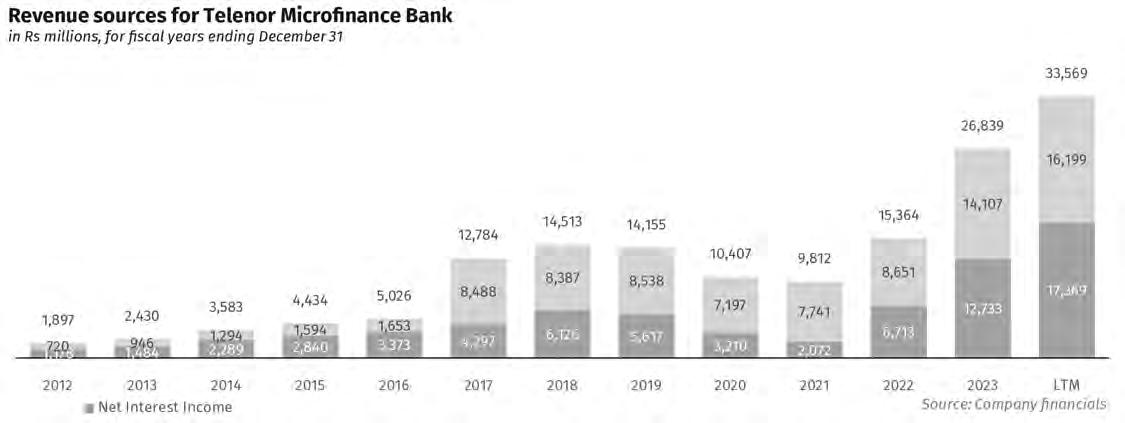

Both net interest income and fee-based revenue increased by 90% and 63% respectively in 2023. How did the bank make this turnaround happen?

On the interest income front, Telenor Bank benefitted from the higher interest rate environment. As microfinance banks usually lend to an underserved market which the banks do not lend to. They have higher risk of default and hence interest rates in microfinance sector are usually on a higher side, north of 40%.

Moreover, the bank reintroduced nano loans in 2022, which were scrapped as the bank restructured its loan book following employee fraud. This aligns with the industry’s shift towards smaller loans. According to Data Darbar, the microfinance sector has seen a decline in the average size of loans disbursed to individuals, with Pakistan Microfinance Network reporting a drop to Rs16,524 in the first quarter of 2023 as compared to Rs41,398 in the fourth quarter of 2020. And telco-backed mobile wallets, like Telenor Bank (Easypaisa) and Mobilink Microfinance Bank (JazzCash), have

been at the forefront of this race as have both the tech and the sponsors to disburse credit to millions at speed

In 2022, the bank disbursed 1.5 million loans amounting to Rs4 billion. This means that the average size of the loan was Rs2,667. The number of nano loans disbursed in 2023 increased to 8.5 million amounting to Rs21.5 billion translating into an average loan size of Rs2,529.

Nano loans are for a shorter tenor and are usually charged with weekly interest. This results in the annual percentage rate (APR) or interest on nano loans being more than 100%, resulting in increased interest income for the bank.

At the same time, the bank’s deposits increased by 31% in the first six months of 2024 from Rs51 billion at the end of 2023 to Rs67 billion. At the same time, its cost of deposits continued to decline. At the end of first half of 2024, the average cost of deposits stood at 1.1% as the bank is strongly focused on low-cost deposits.

On the non-interest income front, the bank’s fee, commission and brokerage income almost doubled in 2023 as income from branchless banking improved.

Branchless banking income consists of commission earned on cash in and cash out transactions conducted by Easypaisa agents, among other things. Between 2020-2022, this income stream was affected because of restrictions inflicted by the regulator.

However, 2023 witnessed improvement on that front mainly because in 2023, the bank started charging a fee on depositing money through the agent channel. In the first of 2024, income from branchless banking stood at Rs6 billion which is higher than branchless banking income earned in entire years between 2020-2022. This reflects the significant recovery and growth in the bank’s branchless banking operations.

As mentioned earlier, Telenor bank’s sponsors have played a major role in the turnaround of the bank. Perhaps the biggest role in Telenor Bank’s turnaround has been Ant Financials’.

Ant Financial acquired a 45% stake in Telenor Bank in 2019 by investing $184.5 million, effectively valuing the bank at over $400 million. This is not really surprising as at that time, fintech companies, particularly in the payments sector, were often valued based on transaction volume or throughput.

Even after that, Ant Financial injected further equity into the bank multiple times to help clean its books. The move towards digital-first and applying for a digital retail bank license hinged on the technology and commitment of Ant Financials Group which played a crucial role in securing the State Bank of Pakistan’s approval for the license. This means that Ant Financial has obviously invested a lot in Telenor Bank and its flagship digital wallet Easypaisa.

Whether or not that investment will end up yielding sufficient returns remains to be seen, but the fact that Telenor Microfinance Bank has at least begun to yield profits – and has done so by utilizing a digital infrastructure and innovative lending products that it can deploy at a reasonable scale with manageable loss ratios – indicates that there is at least some room for optimism.

The temptation at this point for any bank is to try to accelerate the payback period by trying to increase revenue growth. That is usually where reckless lending starts to become the norm, and results in more pain later. If Telenor can avoid that trap, it may yet end up a net positive return for its investors. n

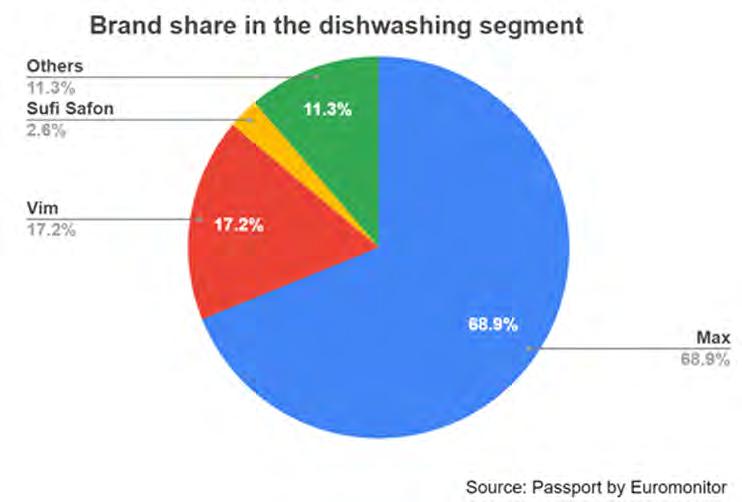

Despite a challenge from Unilever, Colgate-Palmolive’s Max Bar dominates the dishwashing market, taking 68.3% of the market share

By Nisma Riaz

Dishes are washed by hand in Pakistan. Electricity is expensive and so are appliances, which means most households stick to the essentials such as refrigerators and air conditioners, and dishwashers have not really caught on.

This also means consumers have a much more direct relationship with the dishwashing products they buy. The market in Pakistan

is largely dominated by soap bars, but liquid soap as well as in small tubs are available as well. That is pretty much it for diversity in this market, however, because the entire segment is dominated by a single player.

Lemon Max by Colgate Palmolive has nearly 70% control of the overall retail market. Even though the company is widely known for its Colgate toothpaste, its star stock keeping unit (SKU) is the Lemon Max Long Bar.

As far as brand recall is concerned, most people would not know that it is a Col-

gate-Palmolive product because Lemon Max Bar has become a brand in its own right. Let us start from the beginning.

Everyone is familiar with Colgate-Palmolive Pakistan, formerly known as National Detergent Limited. It operates as an affiliate of the American multinational Colgate-Palmolive, as well

as the Pakistani company Lakson. Since 1977, the company has had a strong presence in the Pakistani market.

Colgate-Palmolive Pakistan launched the Lemon Max Bar in 1982 with the tagline “Hara, Kaam Main Khara, Nimbo Ki Taqat Say Bhara.”

Since then, the company has continued to come up with popular taglines, such as “No grease no germs” and “One long bar lasts one month,” focusing on themes such as long lasting, offering good value for money and even lemon infused antibacterial properties.

In 1985, the brand manager of Lemon Max discovered that consumers believed scourers damaged their dishes, leading to the launch of Max Liquid to address this perception. This is a diluted liquid with a lemon-based formula designed to remove grease from dishes, pots, pans, and bottles, as well as odour. This new dishwashing liquid quickly became popular, particularly in upper-middle-class households.

Around the same time, Unilever Pakistan, a major player in the FMCG industry, introduced “Rin” in the dishwashing segment. This sparked aggressive competition in promotions, retail distribution, and event placement in the dishwashing segment. However, experts noted that consumers favoured brands they trusted for cleaning their high-quality dishware and Lemon Max had already established a strong grip in the market, making it the most trustworthy product in this segment.

Rin struggled with positioning issues due to heavy advertising and poor branding decisions, which led to consumer confusion over the product’s colour. Seizing this opportunity, Max Bar aggressively promoted its brand, eventually overtaking Rin in both distribution and media presence, emerging as the market leader.

Almost 15 years after its launch, in 2001, Rin was rebranded as “Vim” in an attempt to re-enter the market. This reignited competition between Max Bar and Vim, as Unilever poured significant marketing resources into trying to reclaim market share. Despite these efforts, by the end of 2004, Rin had vanished from the market, and Max solidified its position as the leader once again.

In the years following, new competitors like Safoon and Aana Bar entered the market with lower-priced alternatives, increasing pressure on Max Bar. To maintain its edge, Max Bar introduced 200g bars and sachets to cater to different market segments. Despite the rising competition, Max Bar continues to dominate the segment.

Noting the success of the Max brand, which started with the Max dishwashing bar, in 2018 the company launched Max all purpose cleaner, which is a scented floor clear.

According to a 2024 Euromonitor analysis, hand dishwashing in Pakistan continued to experience strong retail volume growth and a double-digit increase in current value sales, in 2023. This growth can be attributed to the rising population and number of households, as well as the cultural preference for hand dishwashing. Interestingly, even in homes with domestic help or a dishwasher, hand washing remains the favoured method. This trend spans various socioeconomic classes, including middle- and high-income households, where automatic dishwashers sit in a corner and collect dust. Among Pakistani households, hand dishwashing products are valued for their ability to clean dishes while saving time and money.

Leading brands like Max, Vim, Fairy, and Finish have capitalised on this preference of handwashing dishes, positioning themselves as key players in the market. This reflects a deeply ingrained cultural preference for hand dishwashing, with brands effectively catering to consumer demands across different segments.The popularity of hand washing is expected to persist, for being seen as the most affordable and convenient option across all income levels.

According to the same report, Colgate-Palmolive, Pakistan continued to strengthen its dominance in retail value sales of dishwashing products in 2023. Its hand dishwashing liquids and bars, particularly the lemon variants, were the most popular.

The retail value sales of dishwashing soaps stood at Rs 26.3 billion in 2023. Lemon Max had a 68.3% market share among dish-

washers, making its total sales amount to Rs 17.96 billion in fiscal year 22-23.

Colgate-Palmolive’s gross revenue for the fiscal year ended June 2023 stood at Rs 119.6 billion. Considering that the company’s gross revenue from the sales of Lemon Max products was Rs 17.96 billion, Lemon Max dishwashing soap was responsible for around 15% of the total sales of the entire product portfolio of Colgate-Palmolive.

Unilever’s Vim holds the second-largest market share in the dishwashing detergent category, accounting for 17.1% of the total market. Based on this figure, Unilever generated a total gross revenue of Rs 4.49 billion from Vim, in 2023.

The success of Lemon Max is owed to a strategic focus on the quality that Max has maintained over the years, despite inflationary pressures, by introducing smaller value packs.

Euromonitor forecasts that in order to cater to lower-income households, there is likely to be an increased focus on offering bonus content and promoting smaller packaging options by all brands in the sector. This approach is especially beneficial for households with limited budgets, therefore, these initiatives are expected to gain traction in rural areas, villages, and smaller towns outside major cities.

Another reason for the dominance of Lemon Max is its effective brand promotions, which have fostered a perception of product efficacy and customer satisfaction, as per Euromonitor market research. Colgate-Palmolive’s strong market presence and ability to align with consumer needs have enabled it to capture demand effectively. As a result, the company is expected to maintain its leading position in the dishwashing category in the coming years. n

Ostensibly, the shutdown was about unpaid tax refunds –which are a legitimate grievance for the company – but there is more than meets the eye to the shutdown

By Zain Naeem

Millat Tractors recently hit the brakes on its operations for 10 days, only to restart production shortly after. The company cited financial strain and tax headaches. But is this the full story, or just another chapter in a long-running saga of finger-pointing?

When the government rolled out its latest budget, the agricultural sector took a hit. Historically, many of its inputs had enjoyed tax exemptions or zero-rated status. This year, the government shifted gears, slapping a reduced sales tax on these inputs. Tractors, which had long benefited from a zero-tax bracket, suddenly found themselves under the tax hammer.

Within two months, the cracks began to show. The industry was rattled as manufacturers struggled to get their due sales tax refunds from the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR). Millat Tractors, one of Pakistan’s largest tractor manufacturers, was the first to cry foul. With no mechanism in sight for refund disbursements, the company saw no choice but to shut its doors temporarily.

But was this shutdown just about taxes, or is there more to the story?

The story starts back in 1990 with the passing of the Sales Tax Act of 1990. In 1990, the Sales Tax Act considered agricultural tractors to be an integral part of the economic system which meant that a reduced tax rate of 10% was levied on them. In the Finance Act of 2016, this

rate was further reduced to 5%.

The mechanism that had been developed by the FBR was that the manufacturers would pay the full amount of general sales tax to their vendors. These were the vendors who were providing the company with the basic inputs like tractor parts in order to manufacture. From this, they were allowed to charge a 5% sales tax to their customers while it was the responsibility of FBR to refund the remaining 12% to the manufacturers.

The FBR, however, has a habit of not actually processing those refunds.

Millat pointed the finger squarely at the FBR for not returning billions in owed tax refunds. The company argued that this delay had squeezed its cash flow to the breaking point. Facing the prospect of further accumulation of unreturned taxes, they reasoned it was more prudent to halt production than pile on more liabilities.

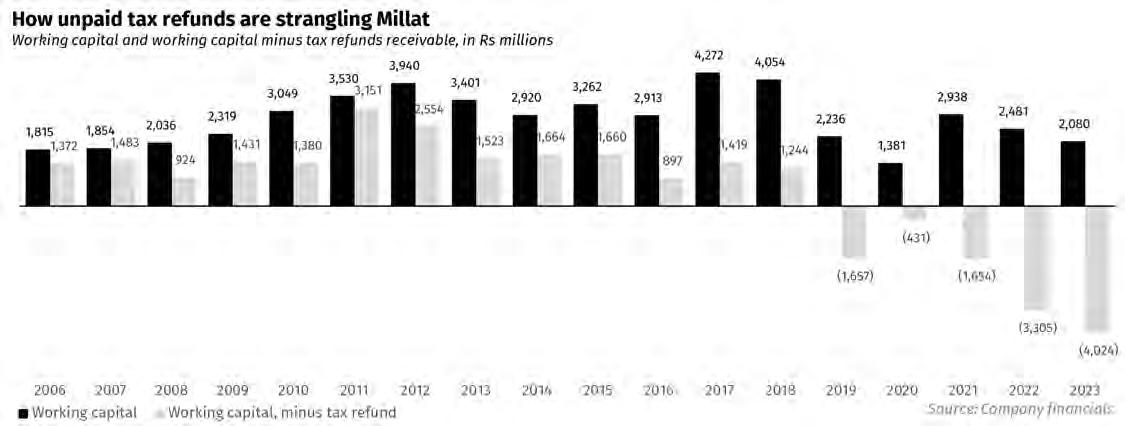

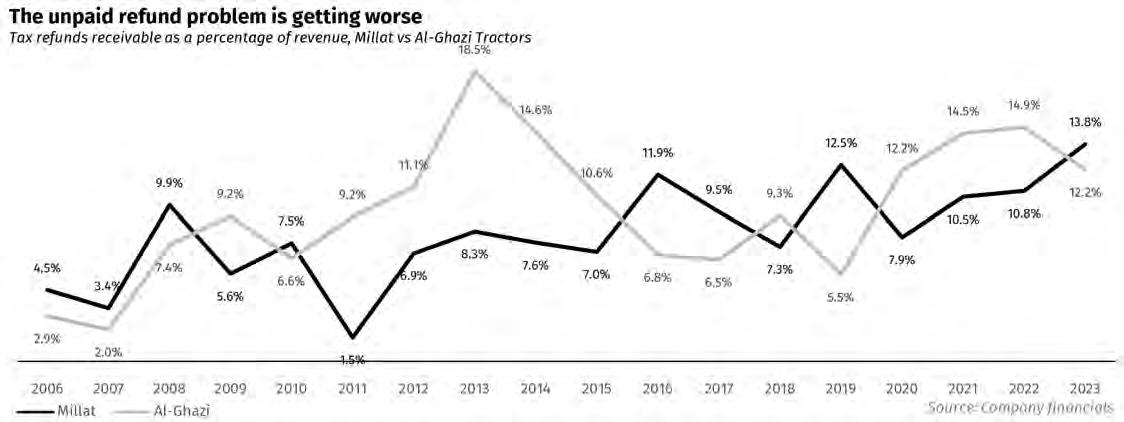

At the heart of this issue is a decades-old tax refund system that has consistently failed to deliver. Back in 1999, Millat had Rs140 million in pending refunds, representing about 2% of annual revenue. Today, that figure has ballooned to Rs6.1 billion, or closer to 14% of annual revenue. Al-Ghazi Tractors, Millat’s main competitor, has seen its tax refund receivables climb from Rs90 million (2% of annual revenue) to Rs4.2 billion (12% of annual revenue) in the same period. Both companies now face serious liquidity problems.

Millat’s 2023 financials tell a sobering tale. The company reported a positive working capital of Rs2 billion, but when the Rs6 billion in unpaid tax refunds is factored in, the reality looks much bleaker. The company’s working capital would plunge into negative

territory.

Working capital is an accounting concept and refers to current assets (cash, inventory, amounts receivable from customers, the government, and others, etc.) minus its current liabilities (amounts payable to vendors, employees, and creditors). Positive working capital means the company can pay its current liabilities as cash comes in, but if any component of its current assets is considered unreliable – such as tax refunds that have not been paid for decades – that can be a problem. That means the company needs to borrow money – and pay interest on it – in order to pay its running expenses.

The financial squeeze is not just theoretical. It shows up on the company’s financial statements.

Millat’s cash flow from operations has turned deeply negative. Despite recording Rs3.4 billion in profits last year, the company posted a staggering Rs4.6 billion in negative operational cash flow. Al-Ghazi is not faring much better, with a Rs 4.2 billion cash flow deficit, despite Rs2.2 billion in profits.

These liquidity issues are compounded by the structure of the industry’s sales tax obligations. Farmers pay a reduced 10% GST, while non-farm buyers are hit with a 17% rate. Yet, the FBR has offered no clear process to differentiate between the two groups, further muddying the waters for tractor manufacturers.

What makes all of this worse is just how much of a difference there is between what the letter of the law states and what is actual practice. The Federal Tax Ombudsman has already passed a judgment on the FBR in

terms of the fact that the previous tax refunds were not being processed in the correct manner.

Under the FBR’s Statutory Regulatory Order (SRO) 363, the FBR was obligated to process the claims of the tractor manufacturers in time. Since the judgment was passed, the pending claims have gone from Rs8 billion to now standing at Rs10.3 billion.

The refund was supposed to be processed within three days since the claim was made under the Recognized Agricultural Tractors Manufacturers Rules 2006. It has been years now and these refunds still have to be processed.

This is not the first time Millat has taken such drastic action. In 2022, the company temporarily shut down operations, citing simi -

lar financial strains. It seems the firm has developed a knack for using shutdowns as a pressure tactic.

Recent financial moves suggest the company is playing the long game. Millat is in the process of absorbing its subsidiary, Millat Equipment Limited, in a bid to cut costs and streamline production. Meanwhile, sales have been on the rise. In the first nine months of the 2024 fiscal year, Millat’s sales surged from Rs30 billion to Rs70 billion. Operating profits quadrupled, and share prices shot up from Rs11 to Rs41 per share.

Clearly, Millat is not exactly drowning. With inventory levels swelling by 50% (from Rs10 billion to Rs15 billion), Millat’s shutdown may have been a savvy move to clear stock rather than a desperate attempt to keep the lights on. The company itself admitted that demand had slowed, creating a glut of unsold tractors. By halting production, it gave itself time to sell off excess inventory before ramping up operations again.

But even with these stockpiles, there are red flags. Millat has been leaning more on its creditors, with trade debts rising from Rs2.6 billion to Rs8.4 billion by March. Reports of vendors refusing to supply Millat parts have swirled, though the company has denied these claims.

Millat Tractors’ shutdown may have been born from legitimate concerns over tax refunds and cash flow, but it is hard to shake the feeling that the company is playing both sides. Yes, tax refunds are a significant problem, but Millat’s financial health—impressive profits and rising sales—suggests that the company is not on the brink of disaster.

This latest 10-day shutdown might not be the last time Millat hits pause on production. But whether the company is genuinely in trouble, or just using the tax saga as convenient cover, is an open question. What is clear is that Millat is not above playing a little hardball when the numbers do not go its way. n

For the past five years, the HBL PSL was the PCB’s biggest source of revenue.

For the past five years, the HBL PSL has been the main contributor to the PCB’s finances. Last year, the Asia Cup and other international tours also became big earners for the board

By Abdullah Niazi

The HBL PSL saved Pakistan Cricket. And no, we are not talking about the impact the tournament has had on the country’s cricketing culture, the opportunities it has afforded to young players, or the extra income it has provided to many professional players who would otherwise never get this kind of international

exposure.

We are talking strictly about the financial side of the equation.

Over the past six years, the HBL PSL has year in and year out been the largest source of revenue for the cricket board. In certain years it has provided up to half of the entire revenue the board saw come into its coffers. Even in the years where the PCB made a loss, the HBL PSL was always a prof-

itable venture for the board.

That is until last year. According to the board’s latest financial statements, which are available with Profit, the financial year 202223 was the first time since 2018 that the HBL PSL was not the biggest source of income for the cricket board. Instead, the biggest source of revenue for the board was international

cricket hosted by Pakistan. The total revenue for the HBL PSL for 2023 came out to Rs 3.55 billion. In comparison, the revenue Pakistan made from international tournaments was nearly Rs 5.5 billion. Normally, revenue from international tournaments is pretty much the same every year since participation fees have been around about the same for some years now. It varies a little depending on where a team finishes in a particular tournament. In 2021 this was Rs 2.4 billion, and in 2022 it was Rs 2.8 billion because Pakistan was the runner up at the T20 World Cup in Australia. But as any fan will tell you, the team has not been on a winning streak in the past year or two. So why the sudden uptick of revenue to Rs 5.5 billion?

Well, for the first time since 2008, Pakistan hosted an international cricket tournament when it was the co-host for the Asia Cup. As the host, they received a preparation fee of more than $ 3.57 million (around Rs 99.4 crores), and saw an uptick in broadcasting revenue of around a billion rupees as well.

And just like that the HBL PSL has been dethroned as the top earner in Pakistan

cricket. This may be a trend we see more of in the days to come. For one, Pakistan is set to host more international tournaments. In 2025, Pakistan is slated to be the venue for the ICC Champions Trophy, which is a much larger tournament than the Asia Cup. On top of that, the HBL PSL may not be as reliable a source of income for the board as it once was. We do not mean that the tournament is not making money anymore, just that the franchises are now rightfully demanding a larger slice of the pie than they were getting before.

The owners of the HBL PSL franchises have long felt that the revenue sharing model of the tournament is unfair, and they have only been getting louder about it. Perhaps nothing signifies this more than the growing debts that these franchises owe the board. Despite these challenges, the PCB will be looking to milk the HBL PSL further, especially with all of the tournament’s franchises up for rebidding next year and the possibility of two new teams being added to the tournament. But before we get into that, let’s take a deeper look at the numbers.

There are a few basics you should understand for this story. Firstly, the Pakistan Cricket Board is an autonomous government entity with its own constitutions. What most people do not understand is it is supposed to be run like a corporation. The cricket board handles money coming in from cricket played in Pakistan, it hires players, coaches, staff, stadiums etc and pays the bills. At the end of the day, they are ideally supposed to make a profit which they can then pump back into promoting cricket in Pakistan.

Now the board has a few different sources of income. They receive an annual payment from the International Cricket Council, which is Pakistan’s share of revenue from international tournaments such as the world cup etc, and which was a record high $17 million last year, shown as Rs 4.24 billion on the PCB’s books. For 2023, this was the singest largest source of money that the board got. The second biggest source of revenue was the HBL PSL. Other

than these international payments that come in from the ICC, the PCB organises domestic cricket tournaments, international series, and sends teams abroad to play cricket. The broadcast rights from these matches, the gate receipts, the sponsorships are all part of the PCB’s income stream.

The single most lucrative event that the PCB organises is the HBL PSL. In 2023, the tournament brought in Rs 3.55 billion in revenue for the PCB, and after expenditures, the board made Rs 1.56 billion from the tournament.

The HBL PSL has been lucrative for the PCB nearly from the very beginning. But the revenue sharing model that dictates the tournament is deeply flawed. The way it works is that the six franchises participating in the tournament agreed to a 10-year contract to lease rights to the franchise for different amounts. They pay this fee in yearly instalments. The highest single payment by a team is around Rs 1.07 billion by the Multan Sultans, although the second highest payment is significantly less at Rs 44.2 crores.

In exchange for this, the PCB organises the tournament, provides grounds, accommodation, supplies, and bears other costs such as broadcasting. Meanwhile the teams are responsible for paying their own players and staff. The tournament itself makes money through broadcasting, gate receipts, sponsorships, and more. Now the revenue from these sources is all put into a central pool which is then divided between the teams and the board. Each team gets around 15% of this central revenue pool and the board gets 5%, but they also get the entirety of the franchise fees.

This scheme has worked well for the PCB. Just take a look at what the HBL PSL has meant for them financially over the past few years. In 2018, the cricket board made a loss of Rs 53 lakhs. Out of a total revenue of Rs 5.13 billion, the board received Rs 2.2 billion from the franchise tournament, meaning it was responsible for 43% of the board’s revenue that year. Now, the tournament itself saw Rs 1.3 billion come in that year from broadcasting, sponsorships, and other revenue streams into the central revenue pool. Of this, the PCB took a hefty cut of Rs 56 crores, leaving the teams to split Rs 74 crores six-ways. The remainder of their revenue came from the Rs 1.55 billion in franchise fees that the six teams paid.

This means that in 2018, the HBL PSL had a total revenue of Rs 1.3 billion, the costs associated with it were Rs 1.6 billion, meaning it made a loss of around Rs 30 crores. Despite this, the PCB made money off of it due to the franchise

fees. The franchises were not particularly happy about this.

The franchise owners were naturally not very happy with this. A colourful assortment of characters including media tycoon Salman Iqbal, Haier and MG owner Javed Afridi to just name two of the more public figures to own teams, the resistance was almost immediate. But that did not stop the PCB from continuing to milk the tournament as much as it could.

In fact, in 2019 the PCB made a profit after some years. The PCB saw revenues of Rs 11.3 billion, and a before tax profit of Rs 5.34 billion. The year also saw the HBL PSL grow, posting a total revenue of Rs 3.31 billion for the PCB. The tournament’s central revenue pool also improved, swelling to Rs 2.78 billion of which the board took a cut of just over Rs 1 billion. This left the franchises with just under Rs 30 crores each, while they had paid the PCB a cumulative Rs 2.12 billion in franchise fees.

Of course, 2019 was a unique year. The PCB had made a killing with broadcast money. Part of the way a cricket board makes money is by selling broadcast rights to bilateral series the team plays with other countries. In 2019, the PCB made Rs 4.01 billion off of these rights, dwarfing what the HBL PSL had made. This was the year the PCB’s long-standing deal with Ten Sports had just ended, and different broadcasters were wanting to display Pakistan’s matches, especially since this was a world cup year in which Pakistan would possibly play India multiple times in high-stakes encounters. The increase was massive, since broadcast revenue had been Rs 63.4 crores just the year prior. On top of this, broadcasters might have been hoping there would be an opening to show the HBL PSL as well, which by this point had a solid international audience. In fact, the rights for the HBL PSL were with PTV Sports, which had paid Rs 1.8 billion in 2019 to have them. They were also going to be bidding for the overall broadcasting rights to international cricket.

The sudden increase in revenue remained an anomaly. In 2020, the PCB collected revenue worth Rs 9.34 billion and posted a before tax profit of Rs 4.31 billion. The HBL PSL was once again the largest contributor to this overall revenue with the PCB collecting Rs 3.62 from the tournament, making it responsible for 38% of the overall revenue.The board also received international payments of around Rs 2.6 billion including a one time $16 million payment from the ICC, which made up around 27% of the total revenues. Both these revenue sources remained the same but had a higher share because cricket tournaments stopped taking place all over the world for a while due to Covid-19 restrictions. Even the ICC T20 World Cup was delayed.

The HBL PSL itself continued to be a very profitable business for the PCB. The board made Rs 3.63 billion from the tournament in revenues,

including Rs 2.43 in franchise payments and around Rs 1.1 billion in central revenue share, basically the same as last year. The franchise fee increased from last year slightly because of the devaluation of the rupee. Overall, the central revenue pool actually decreased from Rs 2.78 billion to Rs 2.57 billion because of fewer sponsorship payments thanks to the tournament being cut short because of Covid-19. This meant further trouble for the teams, which were paying higher fees and a smaller share in the central revenue pool. .

Then there was the other big bit of news. Broadcast revenue for domestic tours dropped to Rs 1 billion this year. Total revenue fell from last year’s Rs 4.4 billion to a measly Rs 1.2 billion. This was again because Covid-19 essentially put an end to international cricket for many months. less because of Covid and more because of a badly negotiated broadcast deal.

Following the pandemic, cricket became significantly more expensive. Maintaining bubbles was very difficult and costly for when cricket did resume in 2021, and boards around the world were struggling. It was at this time that the revenue from the HBL PSL came in handy for the PCB. Since 2018, the PCB had been using revenues from the HBL PSL to slowly shore up the cash reserves they had in the bank. In 2018, the board had a general fund bank balance of close to Rs 9 billion. By 2019 these rose to Rs 13 billion, and by 2020 they had gone to Rs 17 billion. At the end of 2023, this figure stood at over Rs 20 billion.

Thanks to this, the PCB was able to get through the difficult year that was 2021. The board had total revenues of Rs 7.9 billion and posted a loss of Rs 75.6 crores, and these too were only there because the board decided to give some temporary relief to the beleaguered franchise owners of the HBL PSL.

Allow us to explain. In 2021, the revenue collected through the HBL PSL was Rs 3.81 billion of which nearly Rs 2.5 billion came in the form of franchise fees. This meant a total of 48% of the board’s total revenue was thanks to the HBL PSL. This was again during Covid-19 restrictions, so the PSL saved the PCB from being in a whole lot of trouble. The $16 million (Rs 2.4 billion) still came in from the ICC but there were no prep fees since no international tournaments were being held.

Now, the HBL PSL itself was still making money and was profitable as a tournament. Of the Rs 3.8 billion revenue, expenditures on the tournament fell significantly because all matches were now being held in Pakistan. This meant that the central revenue pool, which was also boosted by a new ad deal from Habib Bank Limited and a new broadcasting deal sold to a consortium led by PTV, rose to a record Rs 3.2 billion. Of this, the PCB was supposed to take a pretty big cut. Instead, they decided to give

some relief to the franchises, giving up close to a billion rupees in the process. Why did the board do this? Ostensibly it was to help the franchises out. But it also revealed growing unhappiness within the franchise owners and was quickly exposing cracks in the revenue sharing model of the tournament.

There was a lot happening during 2021 that would affect the year 2022. For starters, the PCB negotiated a three year broadcast deal with PTV in September 2020 worth $200 million which fell apart by November 2021. Then there was the growing unhappiness of the owners of the HBL PSL.

Back in 2015 when the teams had first been auctioned, the PCB had set fees for the next 10 years and they would take these fees in dollars from the five franchises. Overall, it was a payment of $8.3 million a year with the priciest team, Karachi, paying $2.6 million and the cheapest, Quetta, paying $1.1 million. The problem was the dollar was getting out of control. The teams had agreed to the deal at a time in 2015 when the dollar was at Rs 105, and by 2021 it had risen to close to Rs 175. Since all of the owners were Pakistanis and their businesses were in Pakistan, they went from paying a collective Rs 88 crore a year to paying a collective Rs 1.4 billion by 2021. On top of this, in 2017, the PCB also introduced a new team, Multan Sultans, to the tournament worth $6.35 million a year.

The addition of a sixth team also meant the central revenue pool would be divided seven ways now instead of six, with the PCB still taking the single biggest share at over 20% every year. The PCB was now making more off franchise fees while the franchises were making less and less. They were suffering massive losses, particularly since the central revenue share didn’t even cover fees let alone the costs of players, staff, marketing, equipment, and whatnot. Upset by this, the teams simply stopped paying their dues on time causing some cash flow issues for the PCB. Eventually, the board had to go back to the negotiating table and it was decided

the PCB would reduce its share in the central revenue pool to 5%, which placated the teams for the time being. It was also decided that the franchise fee would be fixed and the dollar rate for the teams would be set at the existent Rs 175, which in hindsight was a very good negotiation win for the franchises.

The effort was led in particular by Multan, Karachi, and Lahore, the three teams with the highest franchise fees. At this point, with a central revenue pool share of over Rs 1 billion to each team, smaller teams like Peshawar and Quetta with franchise fees around $1.1-1.2 million were very happy.

This brings us to more recent times. What you have seen above is a dive into how the HBL PSL very quickly became the biggest revenue source for the PCB and helped it become one of the richer cricket boards in the world outside of the Big Three consisting of Australia, England, and India.

Eventually, however, the franchises grew tired of bankrolling the PCB and wanted more of a chance to earn money from the tournament in which their teams had just been bleeding it up until now. The negotiation of 2021 meant the PCB could say goodbye to the steadily increasing flow of money from the HBL PSL they had gotten used to. Revenues from the tournament grew at a rate of 19.98% over three years. But with the dollar pegged and the central revenue pool share cut down, the board could expect less money or at best around the same.

In 2022, the PCB saw revenues of Rs 9.03 billion. The increase from last year can be attributed to the revival of international cricket and payments for Pakistan’s participation in major tournaments. The HBL PSL still had a pretty big portion in the overall revenue. In fact, it had the largest portion at 38% of the total revenue at Rs 3.34 billion. This was, however, the first time that revenue from the HBL PSL fell for the PCB. This did not even happen in 2021 when they paid a big chunk of their central revenue pool share to the franchises.

The tournament actually did very well in 2022. The total central revenue pool ballooned to a massive Rs 5.4 billion, but this year the PCB got to keep a 10% cut that came out to Rs 57 crore under the new 90-10 split that they had in place. This more than halved their central pool revenue which was Rs 1.2 billion in 2021, but meant the franchises were making more money. They were still getting their regular Rs 2.67 billion in franchise fees. Overall, their profitability from the PSL amounted to Rs 2.1 billion because the board spent Rs 1.2 billion on the PSL. THis was less than previous years because the tournament took place entirely in Pakistan.

2018 — 43%

2019 — 29%

2020 — 38%

2021 — 48%

2022 — 39%

2023 — 22%

However, revenue from international cricket in Pakistan fell because of the cancelled deal with PTV. The board scrambled and sold the broadcasting rights to a hodgepodge of contenders, and ended up making around Rs 63 crores from something that was supposed to be worth $200 million over the course of three years. The total revenue from these tours ended up being Rs 1.03 billion. Suddenly, the PCB was in a position where the HBL PSL was still their biggest earner, but they were not getting the same kind of share they once were. So even though the tournament was growing to new heights, especially now that it was fully being played in Pakistan, the PCB was not seeing its share increase. In fact, it was only seeing stagnancy.

That is what brings it to the previous year. In 2023, the PCB saw the largest amount of revenue it has ever seen at Rs 12.45 billion, and posted a profit of nearly Rs 4 billion at the end of the year. This is the second largest profit the board has ever made for a financial year. Of this total revenue, the HBL PSL contributed the expected Rs 3.55 billion, which is an improvement from 2022 but still not the highest amount the PCB has ever made from the tournament.

Again, this is because the PCB is taking

a smaller cut of the revenue pool while fees remain stagnant. The expenditure on the tournament was just over Rs 2 billion, which means the board ended up pocketing a solid Rs 1.56 billion which is the largest annual sum they’ve made off the tournament in any year. The central revenue has also increased this year, to Rs 5.67 billion of which the PCB has only kept a cut of Rs 58.4 crores with the remainder split between the franchises.

PCB’s earnings from HBL PSL Central Revenue Pool

2018 — Rs 56 crores

2019 — Rs 1 billion

2020 — Rs 1.1 billion

2021 — Rs 1.2 billion

2022 — Rs 57 crores

2023 — Rs 58.4 crores

However, the share in revenue has fallen because the board has seen a significant uptick in income coming in from international tours to Pakistan. In fact, the biggest contributor to the PCB’s revenues in 2023 was not the HBL PSL, but international payments made to Pakistan by the ICC and ACC. These amounted to Rs 5.43 billion, making up nearly 33% of the total revenue. For context, this is not even close to the highest share in revenue the PSL has had in any single year which we saw was 48%, but it is still big. So why the sudden increase? Because 2023 marked the first time since 1996 that Pakistan was hosting an international tournament. Pakistan was host of the Asia Cup, and even though India made us co-hosts with Sri Lanka, it was a big pay day. You see before this we’ve seen that international payments come to Pakistan for preparing and participating in these tournaments but hosting gets you the real big bucks. For example, Pakistan received a total of $250,000 for its participation in the 2022 T20 World Cup, which was the largest international tournament to take place in 2023. But because Pakistan was co-host for the Asia Cup, they received a payment of $3.57 million, even though this is a comparatively small scale tournament.

On top of this, the HBL PSL is actually trailing behind at number three in terms of revenue streams as of now. That is because revenue from tours inside Pakistan was Rs 3.69 billion this year, which is a little more than what the HBL PSL brought in. The reason for this? The broadcast rights for Pakistan matches went from Rs 62.9 crores in 2022 to Rs 2.52 billion in 2023. This was still not as high as it once was,

Earnings from International Tournaments in 2023

Asia Cup

$3.57 million

ICC Men’s T20 World Cup

$250,000

ICC Women’s U19 T20 World Cup

$25,000

ICC Women’s T20 World Cup

$50,000

but the increase was also attributable to the Asia Cup taking place in Pakistan.

Now as far as profitability is concerned, we’ve already mentioned that the PSL gave the PCB Rs 1.56 billion in profits, which accounts for a very high percentage of total profit. The PCB actually ended up spending a whole lot on tours inside Pakistan this year amounting to over Rs 3.03 billion, meaning overall profits were just around Rs 66 crores from this.

Quite simply put, the PCB is still in a very powerful position. We have seen how the HBL PSL became the main earner for the cricket board in the past five years. A big reason for this were the terms the board gave to its franchise owners, and at least up until 2021 the board was completely in control and the only party (other than the players of course) making any money from the tournament.

For some time the board kept this up, but eventually the franchises began complaining enough that they stopped making payments and the board had to renegotiate the revenue sharing model. But the PCB may only have let go of the reins because they knew they would be back in the driving seat soon enough.

You see when the board sold the rights to the franchises back in 2015, they did so for a 10 year period. Once that period is over, the franchises will be up for auction again. The board will first set a price that they will ask the franchises to match, and the franchises will make their offers too. If the gap is too high, the board has the right to sell off the franchises to someone else. It now depends entirely on who will want to buy them. Remember, HBL PSL franchises as of now are a loss making endeavour.

We have some indication of how high the price could go. When the tournament introduced Multan Sultans in the fourth edition, the