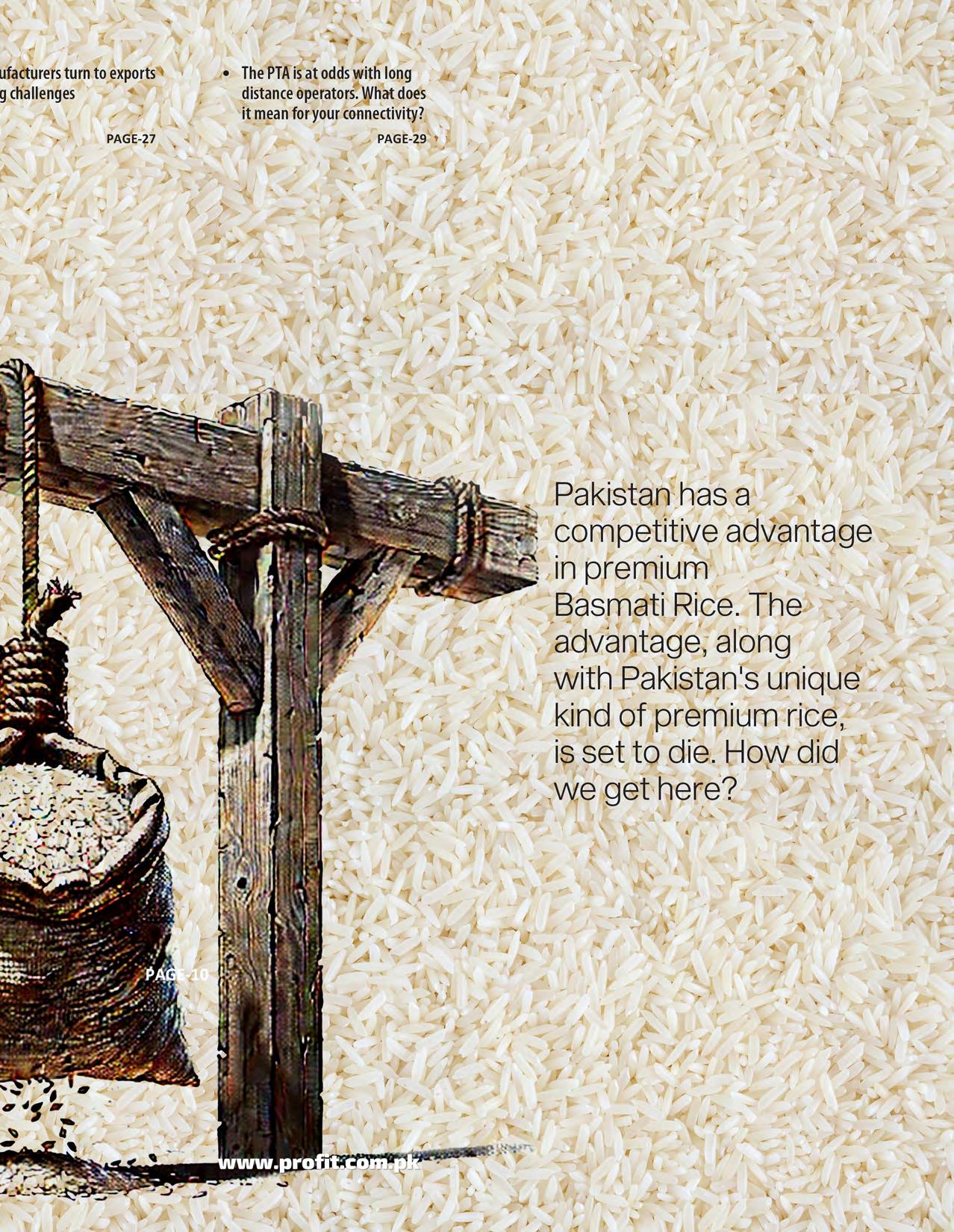

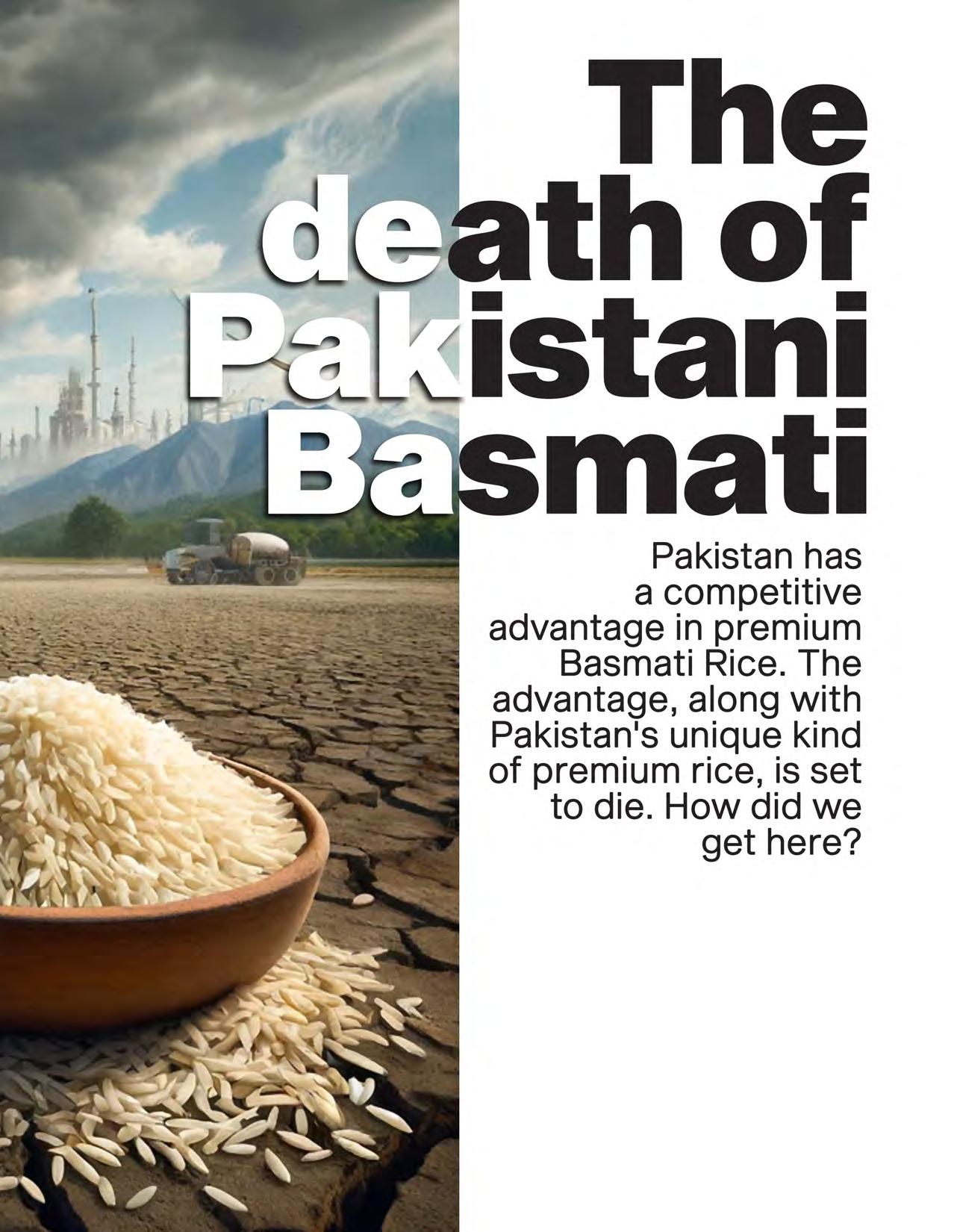

10 The death of Pakistani Basmati

18 Global Insights, Local Impact

23 In Burj’s Clean Energy Modaraba, Pakistan gets its first solar energy-focused consumer lender

27 Cigarette Manufacturers Turn to Exports Amid Mounting Challenges

29 The PTA is at odds with long distance operators. What does it mean for your connectivity?

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz Khan - Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Editorial Consultant: Ahtasam Ahmad - Business Reporters: Taimoor Hassan | Shahab Omer

Zain Naeem | Saneela Jawad | Nisma Riaz | Mariam Umar | Shahnawaz Ali | Ghulam Abbass

Ahmad Ahmadani | Aziz Buneri - Sub-Editor: Saddam Hussain - Video Producer: Talha Farooqi

Director Marketing : Mudassir Alam - Regional Heads of Marketing: Agha Anwer (Khi) Kamal Rizvi (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) - Manager Subscriptions: Irfan Farooq

Pakistan’s #1 business magazine - your go-to source for business, economic and financial news. Contact us: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

By Abdullah Niazi

“Mushki Chawalaan dey bharrey aan kothey , Soyan Pati tey Jhoneray chari dey neen, Basmati, Musafaree, Begumee soon Harchand de zardiay dhari de neen, Bareek safed Kashmir, Kabul khurush jeray hoor te pari dey neen …..”

“…Fragrant rice fills the storerooms wide, Where golden-hued and common grains reside, Basmati, Musafaree, Begumee blend, Harchand and Yellowish, in rows they descend. Fine white Kashmiri, Kabuli delight, Fit for the fairies, in their radiant light, For beautiful women, with grace in their eyes, These treasures of rice, in abundance, lie…”

Excerpt and translation from Heer Ranjha

Aroma. This was the one word Profit heard most in its pursuit of this story.

“A lot of people talk about the smell of Basmati Rice,” says one small-scale farmer from Hafizabad. “They mention how each grain of rice elongates while cooking, how they stay separate, and the way simply boiling these grains brings a smell that is unmatched. I cannot describe it, but the feeling of lifting the lid and the steam from the rice exploding into your nose is addictive. But to those of us that grow it, we start smelling it much earlier. Within weeks of planting, our fields are engulfed in an aroma as soon as the crop begins to germinate. It is the smell I expect to find in heaven.”

The existence of Basmati Rice in what is today India and Pakistan is well recorded. The first mention of it is in Waris Shah’s tragic love poem Heer Ranjha. That is the excerpt at the beginning of this article. The unparalleled utility of Basmati is also mentioned in the Ain i Akbari, the book documenting the 16th Century court of the Mughal Emperor Akbar.

Since the late 1990s, Basmati has become an international phenomenon. The demand for this unique variety of rice has increased in the European and American markets, and where there is demand there is supply. Supermarkets all over the European Union and the United States are stocked full with Basmati, and this special kind of rice comes only from India or Pakistan. In the United States, it even inspired a copycat that tried passing itself off as basmati, until a lawsuit by the Indian government prompted it to change its name to Texmati, so called because it is grown in Texas.

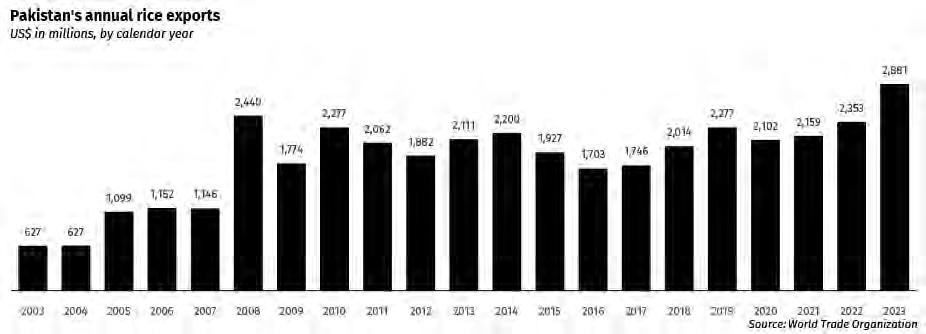

In the past 10 years, Pakistan has exported Basmati Rice in the range of 4.8 lakh metric tons at its lowest in 2016-17, to 8.65 lakh metric tons at its highest in 2019-20. On average, Pakistan has exported around 6 lakh metric tons of Basmati Rice, mostly to Europe and the Middle East in the past decade. Production of Basmati is much higher than exports, but there is also a very strong domestic demand for Basmati. In the year 2023-24, early estimates suggest Pakistan has increased its Basmati exports by at least 24%, raising them to nearly 7.5 lakh metric tonnes. The export of non-basmati rice, on the other hand, has risen by nearly 32% to over 40 lakh metric tonnes.

The cause of this rise does not have to do with increased productivity, or more farmers turning towards rice. It is simply a result of India’s decision to clamp down on its own rice exports last year.

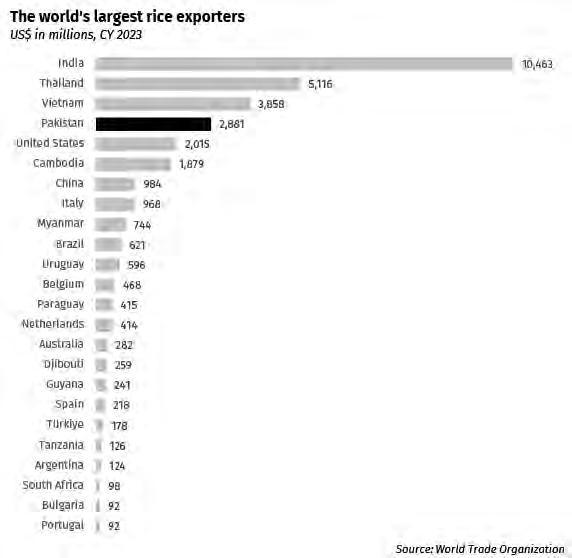

Why do India’s actions have such a ripple effect? Because they are the largest rice producers and exporters in the world.

Of course, this was not always the case.

Back in the 1960s, India was consistently one of the largest importers of rice in the world. Pakistan, in comparison, was a significant exporter all the way through to the late 1980s. This started to change in the 1990s, and in what has been a dramatic turn of events, in the past decade India has consistently beaten Pakistan and the rest of the world in both Basmati and non-Basmati exports. The secret to India’s success is a progressive and aggressive rice export policy that has made very effective use of marketing despite Pakistan’s superior quality and variety of Basmati. But perhaps more importantly, India has been aided by the sheer complacency on the part of Pakistani farmers, millers, exporters, and the government.

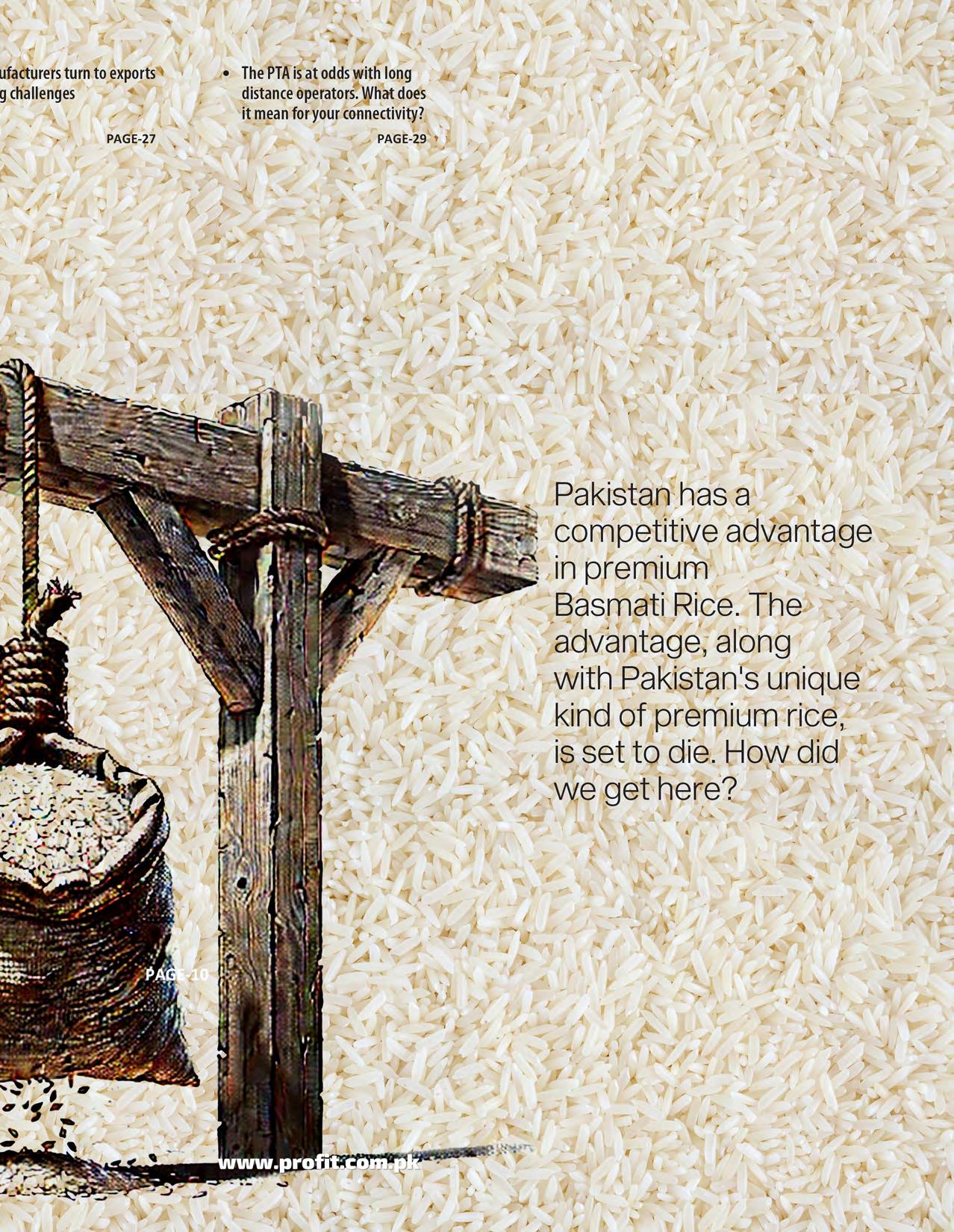

What we could see in the next few years is the complete decimation of the competitive advantage Pakistan’s variety of Basmati has over India. So how did we get here?

In 1933, the British Indian government introduced a seed known then as Basmati 370. For the past many years, a great collaboration had been undertaken by a number of Punjab’s district governments. Basmati rice was famous all over India, and many British officers had taken a liking to the variety of rice. The only problem was there was very little standardisation of this crop which made it ineffective for the corporate style farming that the Raj expected its farmers to pursue.

Which is why a special seed was developed at a rice farm in Kala Shah Kaku which was then marketed, distributed, and grown all over the Punjab. The Basmati 370 seed was the origin of Basmati as we know it today. Before this seed was developed, Basmati was simply the term for a particular aroma that rice of certain districts in Punjab produced. The definition of what was and was not Basmati was very subjective. There was a general understanding that the district between the Chenab and Jehlum produced Basmati because the soil was hit from water from all five rivers of Punjab.

In fact after the development of Basmati 370, efforts were made to grow it in other regions such as Kashmir and Sindh, but the final product was not the same as when it was grown in these very particular regions of the Punjab. This seed was adopted very quickly, giving a boost to Basmati production and also formalising it in the process.

For the next 30 odd years, Basmati became the predominant variety of rice consumed in what is modern day Pakistan. Digging through how fast Basmati became a major part of the Indian diet and a staple agricultural product is a bit of a frustrating endeavour. The

data from both India and Pakistan is patchy, and the Pakistani government has somehow managed to become worse at data management and reporting over the decades. However, using a number of books, reports, journals, and government documents, Profit has charted the evolution of the entire rice market, not just Basmati, in both India and Pakistan over the decades.

The earliest mention of how much rice was grown in Pakistan is in a book titled The International Rice Trade by Julian Roche. It claims that in 1947, all varieties of rice were grown in Pakistan on around 750,000 hectares. One of the things to understand about the rice business in the Indian subcontinent is that both India and Pakistan produce a lot more non-Basmati rice varieties than they do Basmati. Rice like Irri, Japonica, and others give higher yields and are easier to farm. Even though Basmati is much more expensive, many farmers prefer these other varieties because they can produce them quickly and have time for another crop until the next season begins. On top of this, the creation of Basmati 370 proved that Basmati could only be grown in very specific areas of Punjab.

The only comparable numbers we have, however, begin in 1950 in a volume titled “World Rice Statistics 1987” produced by The International Rice Research Institute. Even as early as 1950, India’s sheer size made it a dominant force in the world market. India was farming rice on 29.8 million hectares and producing 32 million metric tonnes. In comparison, Pakistan was farming rice on 884,000 hectares and producing 1.1 million metric tonnes of rice. The difference seems massive, but it is actually quite comparable. India covers a total area of around 329 million hectares. In comparison, Pakistan covers an area of just over 88 million hectares, making India larger by more than four times. This means that in 1950, Pakistan was farming rice on 10% of its land compared to 9% of arable land in India. In terms of yield as well, Pakistan was outperforming India, producing 1.24 tonnes of rice per hectare compared to India’s 1.01 tonnes.

Perhaps most notably, India’s population in 1950 was over 346 million people while Pakistan’s was just over 37 million. This means India was producing around 92 kilograms of rice per individual. While the data for the 1950s is not available, the same volume titled “World Rice Statistics 1987” mentions that rice contributed to 35% of the total caloric intake for the average Indian. As such, Indians were consuming around 111 kilograms of rice per person in the 1950s and 1960s, which is around 225 grams a day. This meant that de-

spite their massive production was not enough to meet local demand and was short by around 20 kilograms per person. This demand had to be met through imports.

Pakistan, on the other hand, was much better poised. As we have shown, the land on the Pakistani side of the Punjab border produced higher yields of rice. On top of this, rice was less of a staple in Pakistan where wheat was the main caloric input. In comparison to India’s 35%, the caloric contribution of rice in Pakistan was around 9% in 1960, which means Pakistan was producing more rice than it needed. Which is why Pakistan was an exporter of rice from this early stage while India was a major importer.

In 1951, for example, India had to import 941,000 metric tonnes of rice to meet local demand which cost them close to $70 million. In comparison, Pakistan did not import any rice at all. In fact, Pakistan exported over 206,000 metric tonnes of rice all over the world. And for many years this was the status quo.

From 1950 to 1970, India imported rice in the range of 193,000 metric tonnes at its lowest in 1953 to 1.01 million metric tonnes in 1965. On average, they were importing around 600,000 metric tonnes on average every year in these two decades. Meanwhile, Pakistan was exporting rice in significant volumes. At its lowest, Pakistan exported some 2000 metric tonnes in 1958. But in the time between 19501970, Pakistan was consistent in exporting and by the late 1960s was exporting volumes as high as 436,000 metric tonnes. The rice trade of Vietnam and Burma in particular suffered in the 1960s, and it was Pakistan and China that met the demand for this. In this way, between India and Pakistan, the frontrunner in the rice race was easily the smaller Pakistan which had a smaller domestic demand for rice. Of course, this was in reference to all kinds of rice being grown and consumed in Pakistan and India. In the background of these dynamics, a shift was

taking place with regard to Basmati.

“My father never wanted me to go into agriculture. He thought he was discouraging me from pursuing a career and maintaining one foot in agriculture at the same time. What he did not realise was I was planning to go all in on agriculture.” Eloquent, well-informed, passionate, and an engineer by profession, Faisal Hasan is a man unusually zealous about rice. Of the many researchers, farmers, government officials, and academics we spoke to and whose words contributed to this article, Mr Faisal Hasan is the only person we are directly quoting in this article.

It is because he is the only one with a personal stake in the matter. He is the son of Colonel (r) Syed Mukhtar Hussain of the Colonel Basmati Farms in Hafizabad. To anyone that has been involved in the agriculture business in Punjab, the late Colonel is a legendary figure. Through experimentation and cross-breeding, he was responsible for developing Kernel Basmati in the 1960s. This was a homegrown variety of Basmati 370 that very quickly took the market by storm. Colonel Mukhtar bred his own variety around the time that the government of Pakistan had developed Basmati 385, an upgrade to Basmati 370. It was supposed to give 30% more yield and be more resistant to cold. The variety ended up failing on a large scale, and that year the Colonel’s farms in Hafizabad had a great output and his variety was commented on as having the “original and authentic” aroma of Basmati rice. Very quickly it became known as Kernel Basmati, a coarse alliteration of the way the word “Colonel” is pronounced in Punjabi.

An agricultural enthusiast, Colonel Mukhtar was not shy about sharing his seed, and very quickly the new variety was taking Pakistan by storm. Now remember, this was

the 1960s. At this time, Basmati was still a phenomenon restricted to the subcontinent. At the time the export of Basmati was restricted to some markets in the Middle East, and to expats living in the UK, Europe, and in America. Most of the Basmati being produced was being sold within the subcontinent, and at the time India was producing using certain varieties they had developed from Basmati 370, but that side of the Punjab was not producing the same quality of grain. Most of the exports going out were non-basmati. Essentially, Pakistan would produce a certain quantity of non-Basmati rice which would sell for very cheap on the market, and this would then be exported to states like Mali, Sierra Leone, and some African nations. The Basmati was sometimes sold to India, both through the border and through Middle Eastern channels depending on how relations were at any given point, and the rest was eaten at home.

Much of this would change with the introduction of Kernel Basmati. At that point in time, as we’ve seen in the earlier data, Pakistan’s production of rice and its yield were both rising. Up until the 1960s yields had been virtually stagnant at around 1 tonne per hectare but by 1968 they rose to around 1.7 tonnes per hectare. Some might claim this was because more Irri variety of rice was being grown and its yields were higher than traditional Basmati. Others claim that the Kernel variety became so popular and successful rice production increased in Pakistan.

The unfortunate part about this is we will never know what was the main contributing factor behind this. It is terribly difficult getting specific data points from this time, but Profit found a hint as to why. In a corner of the Dayal Singh Public Library in Lahore, there was a copy of a Report by the National Commission on Agriculture from 1987 addressed to Prime Minister Muhammad Khan Junejo. A mango farmer by profession and perhaps the most thorough gentleman to hold the office of Chief

Executive in this country, the report includes comments by the Prime Minister. Mr Junejo laments that “unfortunately detailed data by varieties is only available for a limited number of years, which poses significant problems in understanding our own rice market.”

Essentially, the government of Pakistan never bothered to record what kind of rice was being produced and how much of what kind was being exported. What we do know is that in the mid-1960s, Pakistan was producing around 2 million tonnes of rice. By 1970, that production had risen to 3.3 million tonnes. After the independence of Bangladesh in 1971, a lot of rice that was otherwise sent to erstwhile East Pakistan was now exported. The use of fertiliser increased, and as the book by Julian Roche points out, the introduction of new varieties of rice such as Kernel helped increase yields to 4.8 million tonnes by 1978.

Pakistan was on a roll and making money in the process. In 1981, Pakistan’s exports of rice hit a record high of $565.8 million. At the same time, India was struggling. During the 1980s there were some years in which India exported rice, including a big export year in 1980 when it earned $380,000, but all in all India had to continue to rely on imports to meet domestic demand.

Meanwhile, the Kernel variety of Basmati was making waves all over the world. The new kind of rice was exported to European markets where local Europeans began to acquire a taste for it. But there was a problem here. The rice was not marketed as a Pakistani product. Up until 1990, rice was not exported directly by any business in Pakistan. Instead, rice was procured from farmers and millers by a government entity known as the Rice Export Corporation of Pakistan. This meant that as far as farmers and those in the business of processing rice were concerned, the only rates they were getting was from the government. Since they could not sell directly on the international market, there was very little incentive to evolve the business and get involved on the value addition side.

Domestically, however, there was great demand for Kernel Basmati. While the exact data is not available, one of the years for which it is mentioned in the National Commission on Agriculture’s report is 1987/88. The report says that by 1988, 56% of the area being used to cultivate rice was growing Basmati of which nearly the entirety was Kernel. Afterall, even though Irri and other rice varieties give higher yields, the price of Basmati rice is often more than double this rate making it more lucrative. But there was a shift taking place across the border as well.

“In 1965, during the India-Pakistan War, the seeds that my father had developed which had come to be known as Kernel Basmati were transported over the border and brought into

India,” says Faisal Hassan. His claim is one that is difficult to substantiate with great certainty, but which has become fact for many Pakistanis involved in the rice business. Now across the border, India also began growing Kernel Basmati under different names (including ‘Pakistan Basmati’ at one point), and used the seeds to generate newer varieties. The seeds, however, did not take to the Indian climate as well as they had in Pakistan. Instead, what started happening was that rice grown in Pakistan was commandeered by Indian exporters.

Remember, at this point India had very controlled exports of food commodities, especially rice. But a growing expat population meant there was demand for Basmati in Europe and North America. The Pakistan Rice Export Corporation would sell this to foreign clients, but a number of Indian middlemen began buying this premium Basmati rice in the Middle East, repackaging it as made in India, and selling it in other markets. It is a practice which continues to this day, as one miller tells us who sells directly to Indian customers in Dubai. Overtime, this variety of rice became exceedingly popular far beyond just the subcontinent.

The story of Basmati as a major international product only really kicks off around the 1990s. As we have covered in great detail, India was a major producer of rice but with very high demand domestically which it could not cover. As a result, they restricted their exports all the way up to the 1990s.

But the 90s were a brave new era. The Soviet Union had collapsed, India was undergoing liberalisation, and a large privatisation effort was occurring in Pakistan as well. In India, two successive five year plans from 1980-90 were followed by the government spending nearly $30 billion on agricultural development. Watching the European markets react to Basmati, the Indian government also increased the procurement price it offered farmers for rice every single year. It was emerging that Basmati was well-liked in major foreign markets, and it was coming to be known as a premium rice variety. What had been known to the Indian subcontinent was now becoming known to the world. This meant Basmati was a high-end product that could be sold at higher rates than other rice varieties to the rest of the world. Even though Pakistan had the better quality rice (we will see more of that later), India was quick to act and established itself as the ‘origin’ point of Basmati. At this time, there was no fighting over trademarks and Geographical Indications (GI Tags), but India was winning a marketing game here. Perhaps most importantly, India es-

tablished the National Bank for Agriculture and Rural Development in July 1982. By 1990, credit disbursement to farmers had increased by four times to around $7 billion. India’s exports also started to increase, both for Basmati and non-Basmati variants. It was clear the Indian government was all chips in.

Pakistan was also changing. In 1989, the government helped establish the Rice Export Association of Pakistan (REAP). This is an organisation made up of rice farmers and exporters that advocate internationally for Pakistani Basmati. In what is a rare event, it is an industry association that is not there simply to complain, whine, and display gross examples of rent-seeking largely because they do not deal with the Pakistani government. Through this platform, many of those involved in the rice business were allowed to export directly to foreign markets in the 1990s. This was the end of the Rice Export Corporation of Pakistan.

With Basmati the main Pakistani product by this point, it was in the interest of everyone to promote its export. This was further bolstered by the development of a new variety of Basmati known as Super Basmati in 1996. Marketed to appeal to all farmers, this was a modification to the Kernel variety and the brand name ‘Super Kernel’ also became popular in the 1990s. Super Basmati was a longer grain, it gave higher yields, and its aroma was the classic Pakistani aroma that had come to define Basmati in foreign markets like Europe and America. Suddenly, Pakistan’s rice exports were relying heavily on Basmati.

Once again, data from the 1990s in particular is hard to find. There is no breakup of which variety was being planted, or what the exact yields were. However, Profit did manage to find a government report sent to the office of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif in 1999 which claimed that since the release of Super Basmati, the Pakistan rice export jumped from 450,000 metric tonnes in 1994-95, to 1 million metric tonnes by the end of 1999. The availability of surplus Basmati rice enabled our rice exporters to increase their share of export in the international market against their sole competitor India. This has resulted in the increased share of basmati rice export in the EU market and Pakistani rice exporters started to capture the EU market gradually.

A big part of this was an import duty waiver given by the European Union. The EU originally had a 264 3uro per metric tonne import duty on grains which was reduced to 14 euros per tonne for Basmati rice.

“The Pakistan Basmati rice commanded a premium price in the international market due to its unique aroma, long and slender grain and elongation after cooking. This premium plus its increased popularity both in domestic and international markets makes Basmati rice a tar-

get for adulteration with cheaper, long-grained non-Basmati varieties,” claims one exporter that has been in the business since the 1980s.

As the profile of Basmati grew, troubles were brewing. It started in 1997 when an American company called RiceTec was granted permission by the US Patents and Trademarks Office to market a new variety of rice it was producing as an evolved “superior” version of Basmati. To make their new variety, RiceTec had crossed traditional Pakistani Basmati with certain kinds of long-grain rice grown in the US.

Somehow Pakistan did nothing about it. Alarmed by what this meant for rice exports in the future, India stepped up to bat for the Indian Subcontinent and challenged the decision of the patent office in court, claiming it was a case of Biopiracy. For the first time, the claim was made that Basmati was a specific product that was indigenous to and could only be produced in a certain region. At the time, India did not claim it as Indian but rather as a larger subcontinental product from the Punjab. Eventually, India approached the World Trade Organisation, and RiceTec withdrew 15 patents it had filed. India had won, and as a result so had Pakistan. But with the common enemy defeated, the two neighbours were about to tussle.

After winning the battle against RiceTec, the doors had been opened to claim Basmati. A precedent had been established to ensure that Basmati was only grown in a particular region. The issue would now be who would capture the market as their own. At the turn of the century, India had come out of its earlier hesitancy and established itself as a dominant exporter in the United States of Basmati rice while Pakistan was leading in Europe.

In India, the domestic demand for rice was not overly reliant on Basmati. Many regions in India were happy to consume non-Basmati varieties as well, unlike in Pakistan where the entire country had gotten used to a very specific kind of Basmati. This means India knew even though Basmati accounted for 10% of their overall exports of rice in the year 2000, they needed to focus on making Basmati an export oriented crop. If ever demand was high locally or prices were out of control, they could keep exporting Basmati and provide the electorate with Irri and other non-Basmati varieties.

In 2003, India produced the Pusa variety of Basmati Rice. It had been derived from Pakistan’s Super Basmati and proved to be a very effective crop. Now, the difference between Pusa and Super is very subjective. Yes, we can discuss the finer points of grain lengths, widths,

colour, milling rates etc but at the end of the day, the general consensus was that Super had the better aroma and taste, but Pusa was a good enough imitation for foreign markets. But things were about to get chaotic.

The dawn of 2004 saw the doomed fate of Pakistan’s Super Basmati in the European Union (EU), which ruled for many years due to its superb grain quality. A blow on the export of Basmati rice was dealt by the Cereal Management Committee (CMC) of the EU, which excluded it for abatement concession of approximately euro 250 per tonne with effect from January 1, 2004. The Pusa variety from India was also excluded from this list, and the EU decided it would only allow pure heritage Basmati rice.

The actual purpose of initiatives of the UK’s Food Standards Authority (FSA) and the CMC was to protect consumers from mixing of cheap grains. Up until 2003, Super Basmati had become recognised as the Basmati variety known in Europe. India did not have the same quality of rice, but they had their own varieties such as Sherbati, Basmati 198, and Pusa which they developed in 2003. When these Indian exports started coming in, consumers felt they were no longer getting the same variety of rice. The EU removed the concession on import tariffs at the start of 2004.

For a few months, it seemed to be a disaster. The original ‘pure’ varieties of Basmati did not have high yields, and they were not profitable for farmers. It also made no sense to grow them since the domestic market in Pakistan had gotten used to Kernel and Super. With experience from their fight against RiceTec, India made overtures to Pakistan to fight this together. Why don’t we make a joint effort to have our varieties approved as original Basmati. If you advocate for Pusa, we will advocate for Super Basmati.

What happened next is a saga of our usual negligence, lethargy and ad-hocism. In 2004, Pakistan was exporting 80,000-90,000 tonnes of Basmati rice to Europe which is around $53 million foreign exchange in a year. The exclusion of Super Basmati from the abatement list would make it hard to compete.

“I wrote letters to the Prime Minister, I tried to make a case for our local Basmati. All we had to do was DNA testing but no one was bothered,” claims Faisal Hasan of Colonel Farms in Hafizabad. “Pakistan did not make any protocol on DNA testing of Basmati as India did. We should have done it. Pakistan research institutes with high tech laboratories did not participate in collaborative trials of basmati. Two labs of India participated. I didn’t get any response from the government or research

industry to do the needful. Pakistan would have benefitted in millions of dollars and at the same time countered the once again bogus Indian narrative of traditional versus evolved.”

Instead, Pakistan simply agreed with India and with their help convinced the EU to allow “hybrid” varieties to be given the import duty concession of 250 euros. This was the first nail in the coffin.

Try to comprehend what happened here. Basmati was the joint heritage of India and Pakistan. Up until 1996, Pakistan was the country exporting this product to the world, especially after it introduced its unique ‘Super’ variety which was a hit everywhere. Meanwhile India had to focus on local demand and could not become a big exporter until the late 1990s. When the world took notice of Basmati and even tried to make it the subject of Biopiracy, India was the one to step up. Over the years they took centre stage on the topic of Basmati and their exports started to grow. They flooded European markets with their varieties even though these were of an inferior quality, and when time came to define what Basmati was, they took the first step and had their varieties declared the same as Pakistani varieties. And in case you were thinking consumers in Europe and America would notice the difference in quality, they simply began buying Pakistani rice in Dubai and repackaging it as ‘Made in India’ before selling it to Europe and the US.

On top of this, Pusa was a more high yield variety and India was more easily able to export it. Pakistan, once favoured as the top dog of Basmati in Europe, was falling far behind. The only problem was the government did not quite realise just how massive Basmati would become as a product.

Look at some of the data. Even as early as 2008/09, Pakistan was a larger overall exporter of rice than India. In the early 2000s, India was benefitting from liberalisation and had been exporting a lot of non-basmati varieties as well as Basmati to the EU and American markets. Pakistan consistently ranked fourth in the world. But around 2007, India stopped exporting non-Basmati varieties to meet domestic demand. What they did not stop was the export of Basmati.

In 2008/09, India exported over 150,000 metric tonnes of Basmati to the European Union. In comparison, Pakistan did not even export 50,000 metric tonnes. The trend continued, coming to a crescendo around 2013/14 when India came close to touching 300,000 metric tonnes of Basmati exported to the EU compared to Pakistan which was stuck at the

50,000 metric tonnes mark.

That started to change close to 2015. Pakistani farmers realised Super Basmati was dead in its tracks. They were turning to producing non-Basmati varieties because the yields were higher and Basmati was not getting the same rate it used to once upon a time. So they turned to Pusa as well. In Pakistan, a variety of Basmati rice by the name of Kainat was introduced that was a replica of the Indian Pusa. More and more farmers in the Basmati belt of Hafizabad, Narowal, and Okara began planting Kainat.

Once again, we cannot say with exactitude how big this shift has been. The government of Pakistan is horrible at collecting and keeping data. Up until 2008/09, the food ministry’s annual report on district-wise agricultural production used to contain details of what varieties of rice were grown in what amounts. Since then, however, they only report rice as one product despite the massive difference in the markets for both these products. But the acreage on which all kinds of rice is planted has changed by a few thousand hectares only since then. Back in 2009, Basmati was grown on 57% of the total area dedicated to rice farming. You will remember that the National Commission on Agriculture’s report from 1987 also estimated Basmati to be grown on 56% of the total land dedicated to growing rice, so the percentage really has not changed significantly over time. What we do not know is how many farmers have shifted to Kainat. Remember, Pakistan has an advantage in Super Basmati because it is of a more premium quality and fetches higher prices on foreign markets. Despite this, because of higher yields, Kainat has become the predominant variety grown in and exported from Pakistan according to the Rice Export Association of Pakistan.

Possibly off the back of this, in 2015/16 Pakistan improved its exports to the EU, crossing 150,000 metric tonnes. Around 2017/18, Pakistan came neck and neck with India at 205,000 metric tonnes to their 215,000 metric tonnes exported to the EU. Pakistan was catching up on the Basmati market. And in 2019, India was demolished.

In 2019/20 Pakistan’s exports to the EU grew to over 250,000 metric tonnes while those from India fell to under 120,000 metric tonnes. During the last two decades Basmati rice imports into Europe increased significantly, were valued $ 551.8 million in 2020 and are projected to reach $ 866.5 million in 2031. In 2021 imports of rice from Pakistan valued at 329 million euros in comparison to 166 million euros from India according to the European Commission. This success of the Pakistani imports over those from India were mainly due to pesticide residues in Indian Basmati and in particular to a decision by the EU com-

mission to decrease the maximum residue level (MRL) for the fungicide tricyclazole from 1 to 0.01 mg/kg starting January 1st, 2018. Instantly the imports from India decreased significantly and Pakistani imports took over. The trend has continued in the past couple of years, but Pakistan’s rise might be a very temporary one.

You might say at this point in the story, Pakistan seems to be doing pretty well on the Basmati front. It has captured the European market and has steady exports all year round. In 2024, Pakistan placed fourth as a global rice exporter behind India, Thailand, and Vietnam in rice exports despite being ninth in overall production.

This financial year ending on June 30, rice exports from Pakistan may touch the 5.8 million tonnes mark, a fraction short of the magical 6m tonnes figure, mainly because of favourable weather, availability of farm inputs. Data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics suggests that rice exports crossed the 5m tonne mark in 10 months (July-April 2024), earning $3.4 billion, compared to 3.2m tonne exports worth $1.8bn made during the corresponding period last year. There has been a 32% volumetric increase in exports of non-Basmati and a 24% increase in Basmati. On average, the Basmati export price during the 10 months remained $1,141 per tonne and non-Basmati $573 per tonne.

But there is a problem here. The only reason Pakistan’s exports increased is because in late 2022, India placed another ban on exporting rice. The reason was the same as in the 1960s, 70s, and then again in the 2000s. They felt they needed to meet domestic demand, and as a consequence banned the export of all varieties of rice other than Basmati. This is because India recognises the value of Basmati because of its higher prices. In 2022-23, the total export of non-Basmati rice from Pakistan was 3.7 million metric tonnes. Because of the Indian ban, this has gone up too close to 4.8 million metric tonnes. The export of Basmati, on the other hand, has gone up slightly over 700,000 metric tonnes compared to almost 600,000 metric tonnes last year.

Essentially this means India’s decision to ban non-Basmati exports has shifted Pakistan’s production more towards non-Basmati varieties. Non-Basmati Indian exports nosedived to less than 1 million metric tonnes in volume this year from 16.4 million metric tonnes a year earlier.

However, Indian Basmati exports touched a new high of 5.2 million metric tonnes from April 2023 to March 2024 (Indian financial year) despite strong tailwinds in the early part of the Kharif 2023 season, such as

devastating floods in the Indian Punjab.

Pakistan Basmati rice export during this time (April 2023 to March 2024) has been 730,000 million metric tonnes, which is 14% of Indian Basmati export. But Pakistan’s per tonne earning was $1137, which is 3%c higher than the price of Indian Basmati. Again, this is in part because Super Basmati earns better prices. A report from S&P Global for 2024 points out how the Pakistani rice market is looking bullish this year particularly because of the increased demand for Super Kernel Basmati.

What you have at the end of the day is a market reality in which India can control its domestic supply of rice and also rules the export market of both non-Basmati and Basmati. Pakistan is increasingly relying on non-Basmati for its exports to countries like Kenya, Senegal, and others in the MENA region. Pakistan very much has a competitive advantage over India that it used to dominate with up until at least 2006. However, because Pakistan has been unable to protect its interest, Pakistani farmers are also growing the Kainat variety rather than Super Basmati which has the advantage.

And on top of this, India is not readily giving up on the European market.

Pakistan is well and truly on the ropes. To sum up the entirety of the conversation we have had, Pakistan is home to premium Basmati but India is the major exporter of this product, which has led to Pakistan also growing less of its premium variety.

More than two decades ago, Pakistan

and India had put up a joint front to protect the ownership of their ‘shared heritage’ by fighting an attempt by the US company RiceTec to get an American strain of rice patented as basmati. The World Trade Organisation decided in their favour, denying the American company’s application. Today, they are at loggerheads over who owns the unique, long-grain aromatic rice grown only in the subcontinent as India has applied for the grant of an exclusive GI (Geographical Indications) tag for its basmati rice at the European Union’s official registry.

In 2018, when Pakistan was first set to overtake India in Basmati exports to Europe, India applied for a GI tag. A GI tag in international trade is essentially the right to claim that a particular product belongs to a particular region. It is essentially claiming that only rice coming out of certain regions in India can be classified as Basmati. Pakistan was slow to react. The application was processed by the European Union and the matter was dragged all the way to 2021. To apply for a GI tag for a product, the legislature of that country has to declare it so in their own country. India had done this in 2007 in preparation for such a day. Pakistan did not get around to it until 2022 when the Senate finally passed it.

If India wins this battle, Pakistan would not only lose the large EU market but also find it difficult to export its basmati rice to the rest of the world to the detriment of thousands of farmers and other people associated with the rice trade. At present, Pakistan exports basmati rice worth between $800m and $1bn, controlling almost 35% of the basmati market share across the world. India, the only other global basmati rice exporter, accounts for the rest of the market.

The matter is still ongoing with Pakistan retaliating by also applying for the tag. The EU has repeatedly given the two countries opportunities to make nice and sort out the dispute amongst themselves. A resolution seems far from coming. Currently, Pakistan controls around 35% of the world Basmati trade while India has the remaining share. Pakistan will never produce as much Basmati as India simply because of its size. Despite this, Pakistan has a historical and quality advantage over India when it comes to Basmati. India exports to Middle Eastern markets and North America more than Pakistan but over the past few years Pakistani rice has once again become dominant in Europe. The GI application is simply meant to elbow Pakistan out from here too.

Many in Pakistan would like to posit and argue that Basmati originates from the region that is Pakistan, not India. The reality is that this is shared heritage and it must be treated as such. India’s ideal situation is for Pakistan’s Super Basmati and other unique varieties to eventually get snuffed out. With Pakistan growing Kainat, India can simply come in and take over the markets Pakistan currently holds. And as history shows us, Pakistani farmers and exporters will be happy with the space India allows us in non-Basmati exports.

Basmati is a rare product that is unique to Pakistan, in demand and high value. Despite having a clear advantage, Pakistan has been taking directions from India simply out of sheer negligence. If Pakistan is to grow its Basmati trade, a lot more emphasis must be put on growing the right varieties, marketing them well, and being proactive in international markets. Otherwise Pakistan’s unique varieties of Basmati might die out. n

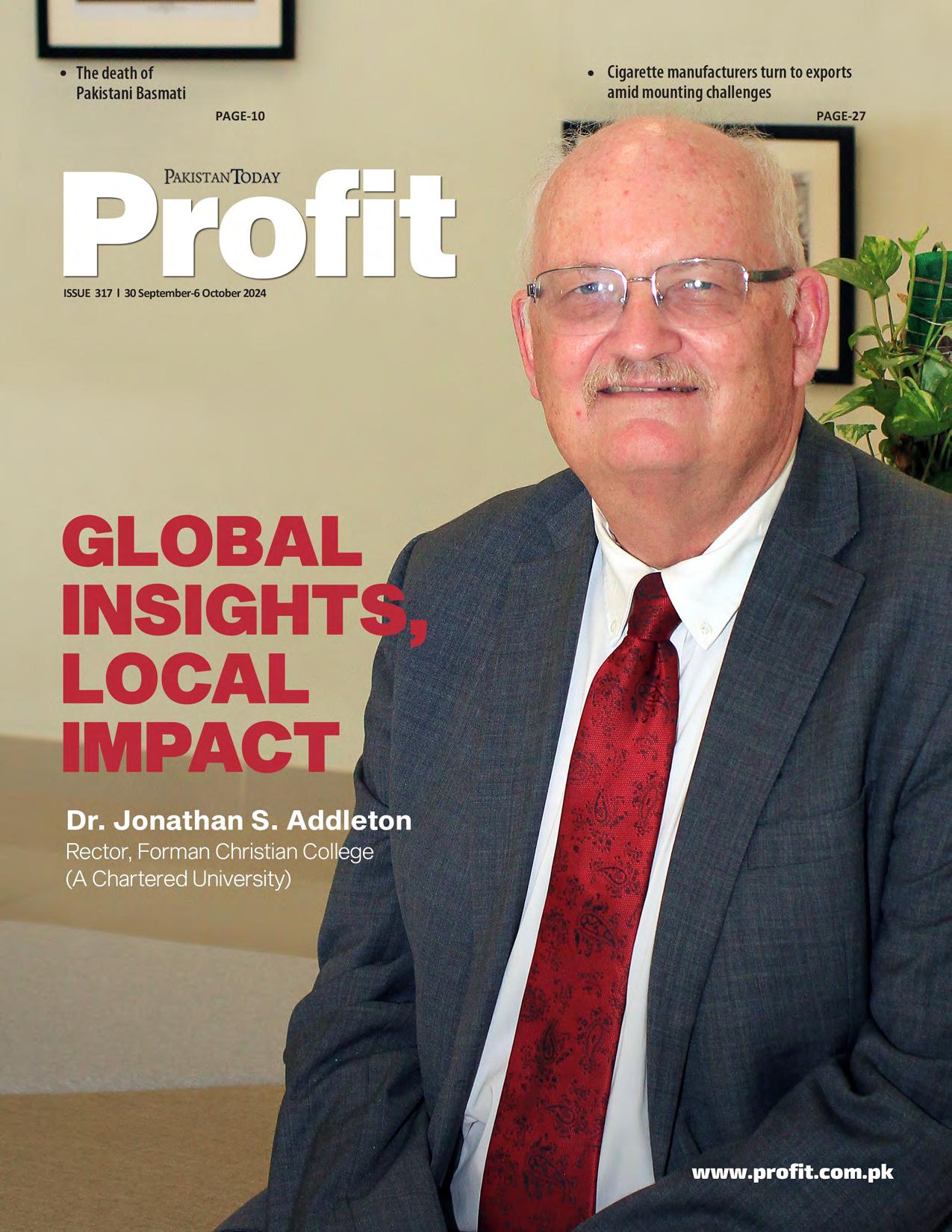

Dr. Jonathan S. Addleton

Rector, Forman Christian College (A Chartered University)

By Profit

Dr. Jonathan S. Addleton is serving as the current Rector of Forman Christian College (A Chartered University). A seasoned diplomat, he retired from the U.S. Foreign Service after a long career of 32 years. He has held key positions such as the U.S. Ambassador to Mongolia and the USAID Mission Director in India, Pakistan, Cambodia, Mongolia and Central Asia. He was also the USAID Representative to the European Union in Brussels, and the Senior Civilian Representative to Southern Afghanistan based in Kandahar. Dr. Addleton also served as the Executive Director of the American Center for Mongolian Studies, and Adjunct Professor in the Department of International and Global Studies at Mercer University in Macon, GA. During the early days of his career, he worked at the World Bank, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, World Book Encyclopedia and Macon Telegraph. Along with holding a PhD from Tufts University’s Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, he is also an accomplished author, having written several books and articles. He has earned numerous accolades in recognition of his contributions, including Mongolia’s highest civilian honor, The Order of the Polar Star, ISAF Service Medal from NATO, and the USAID Administrator’s Distinguished Career Service Award.

Q: FCCU is one of the few liberal arts universities in Pakistan; how does this educational approach enhance the student’s overall learning experience?

A: As a liberal arts university, FCCU offers a comprehensive education that encourages students to explore a diverse range of disciplines while also fostering intellectual curiosity, lifelong learning, and ethical decision-making. At the same time, a liberal arts education with its interdisciplinary approach equips students with transferable skills that are highly valued in today’s ever-changing world including critical thinking, communication, and adaptability.

Q: How do you think FCCU is similar and different from a university of the same size in the US?

A: FCCU is similar to a comparable size university in the US with respect to the qualifications of its faculty, the vibrancy of its student life, the depth and breadth of its course offerings, and the size and beauty of its campus. Like many universities in the US, we also take a global perspective, encouraging students to think critically about international issues while fostering cultural awareness.

Moreover, our faculty have advanced degrees from at least 21 different countries. Of course, we also operate within the social and cultural context of Pakistan, providing our students with unique experiences and opportunities that would be difficult to duplicate anywhere else in the world.

Q: Can you share how FCCU supports students from diverse socio-economic backgrounds with financial aid? Also, could you elaborate on the goals of the scholarships offered and how they positively affect the lives of students?

A: Financial aid plays a key role in building and maintaining one of the most vibrant and diverse campus communities in Pakistan. This financial support serves as a gateway to higher education for many students who would otherwise not be able to attend. For example, during the 2023-2024 financial year, Forman provided scholarships valued at PKR 430 million to more than 2,000 students at all levels - Intermediate, Undergraduate, and Post-Graduate. FCCU is dedicated to ensuring that students from economically disadvantaged families can pursue an education. Our tens of thousands of alumni leave a positive impact on their families, communities, country, and indeed the world, all while embodying Forman’s enduring motto: ‘‘By Love Serve One Another”.

Q: How do you envision improving student engagement and enhancing the overall student experience on campus?

A: Campus life at Forman is already very vibrant and widely viewed as an integral part of the Forman experience. Throughout the year our student societies organize a wide variety of successful events that help bring our community together. From music nights to inter-university sports competitions to debating and cultural nights, FCCU engages students in a multitude of ways, and that is only the tip of the iceberg. Community service groups organize volunteer projects to give back to the community while academic societies promote specific subjects in ways that both ad-

vance student learning and enrich the campus experience.

Q: Could you please discuss the measures and strategies FCCU is employing to encourage diversity and inclusivity, creating an environment that values and celebrates differences?

A: FCCU has been home to tens of thousands of students over the past 160 years, attracted in part by the rich religious, cultural, ethnic, geographic and socio-economic diversity reflected across our community. The first Sikh officer and the highest ranked Christian general in the Pakistan army were both Forman graduates; the renowned Pakistani diplomat Jamshed Marker who left his library to Forman and was from the Parsi community was also a Formanite. As these examples suggest, Forman has always encouraged diversity, offering students from very different backgrounds an open and respectful environment that encourages students to connect, appreciate and learn from each other. We firmly believe that this diversity makes us a better place.

Q: How is Forman Christian College (A Chartered University) actively contributing to the ever-evolving IT industry landscape?

A: Computer Science is one of the most popular majors at Forman. Partly in response to this interest, we introduced two new MPhil programs last year: Data Science and Software Engineering. Collaborations with IT companies offer opportunities for internships, joint research projects, guest lectures by industry professionals, and mentorship programs. In addition, our Student Activities Office, along with student societies, organizes different competitions and IT-related events, fostering innovation and encouraging the practical application of skills in real-world scenarios. Also, our new Digital Library, situated in our new Campus Center, ranks among the most advanced such libraries in Pakistan.

Q: Could you please walk us through the university’s international linkages? How do these global

partnerships benefit your institution in terms of academic excellence?

A: FCCU is an active participant in the Global Liberal Arts Alliance (GLAA), Council of Independent Colleges (CIC), and American International Consortium of Academic Libraries (AMICAL), facilitating a variety of partnerships ranging from academic exchanges to online classes in which Forman students engage with other students from all over the world. In addition, Forman is the first institution in Pakistan seeking accreditation from the New England Commission of Higher Education (NECHE), the same US-based body that accredits Yale, Harvard, and MIT. Beyond that, our Office of International Education promotes foreign study opportunities for Forman students across the world including in the US, Turkey, Malaysia, South Korea and elsewhere. In addition, Forman students have received a variety of prestigious international fellowships including Fulbright (US), MacBain (Canada), Chevening (UK) and Erasmus (UK), among others; other students have received grants to study in China, Japan, South Korea and elsewhere. International donors have contributed to Forman as well including the US (UGRAD Fellowship Program), Japan (library books), Germany (media equipment) and South Korea (scientific equipment for water research).

Q: How does the university actively engage with and leverage its alumni network to contribute to the institution’s ongoing success and the professional development of current students?

A: We have a dedicated Advancement and Alumni Office that diligently maintains a robust network with our former students, organizing industry-specific conversations on everything from media to education to IT. These interactions not only strengthen the Forman-Alumni relationship; they also contribute to internships and career placements for current students. In addition, some of our leading donors are Forman graduates who generously give back to us in various forms, especially by supporting student scholarships.

Q: Extracurricular activities are an important source of learning beyond the classroom. How does this apply to FCCU?

A: Forman’s 38 active Student Societies play a pivotal role in shaping the university experience beyond the classroom, providing numerous opportunities that cater to the diverse interests of our students. In addition, they provide students with opportunities to engage in co-curricular activities, showcasing their talents and boosting their confidence while also promoting crucial leadership and

management skills.

Q: What measures and initiatives has FCCU adopted to empower women?

A: Women’s empowerment is a priority at FCCU and nearly half our undergraduates and two-thirds of our graduate students are female. Some scholarship programs are designed to specifically benefit women including those from remote areas such as Balochistan, KPK, Gilgit, Baltistan and even the remote Kalash Valley in northern Pakistan. In addition, Forman’s Women Empowerment Society works tirelessly to promote innovative ideas to empower women. With respect to hostel accommodation, the Cheryl Burke Hope Tower serves as a home away from home for more than 700 female students while another 100 beds will soon be available nearby as the result of the TSA/Forman partnership.

Q: As a renowned institution, FCCU is known for its commitment to student career development. How does the University support its students in their career pursuits?

A: Our Career Services and Internships Office (CSIO) was established specifically to support our students in their career development. This department aims to provide comprehensive guidance and counseling to its students and graduates on career development, assisting students in their job search. The CSIO also maintains links with national and multinational employers, industrialists, government organizations, and distinguished members of the FCCU alumni network. Throughout the year, this office also organizes a wide range of on-campus activities, including career exploration lectures, job fairs, recruitment drives, resume development and career-build-

ing workshops, employer-hosted information sessions, mock interviews, and career fairs.

Q: Dr. Addleton, FCCU has shown significant improvement in various aspects over the past few years. Could you please shed some light on the key factors or initiatives you believe have contributed to this positive change and progress?

A: Infrastructure projects completed over the last four years include a world class Campus Center, Media Lab, Female Hostel and Sports Fields. In addition, we are well on our way toward using solar energy to meet our energy requirements. Of course, new buildings and innovative infrastructure projects only tell part of the story; in addition, we have promoted international study opportunities while also developing initiatives to attract students including female students from some of the most remote parts of Pakistan. Finally, the opening of the new Jim Tebbe Campus Center is a landmark event, providing impressive space for student activities while also including a Digital Library, Business Incubation Center, Exhibition Hall, Art Gallery, Store, Coffee Shop, and other facilities. During the March 2024 NECHE visit, the accreditation team described our Campus Center as potentially ‘‘transformational” -- and that is certainly what we intend it to be.

Q: Can you please share your vision for the university and how does this vision strengthen the economic and social fibre of Pakistan?

A: On my arrival at Forman four years ago, I stated that I wanted to strengthen our international partnerships while also deepening the quality of our institution, ensuring recognition for Forman as one of the leading liberal arts

universities in South Asia. We have already made significant progress in both areas and I am committed to strengthening those international ties and deepening the quality of our institution still further in the years ahead.

Q: Moving to a new country can be a significant adjustment. How have you found adapting to the local culture and working with a diverse university community? Is there anything about the local culture or academic environment that surprised you or stood out to you?

A: Having returned to Pakistan after many years away I was prepared for surprises. That said, I was born and raised in Murree; spent winter vacations with my parents in Shikarpur and Hyderabad; and later served as USAID Mission Director in Islamabad following the earthquake that devastated parts of northern Pakistan in October 2005. Against that backdrop, my unexpected return to Pakistan as Rector in November 2020 was like coming home. As it happens, this is the final chapter in my professional career and I want to make the most of it while fulfilling the Forman motto which places service at the center of everything. The fact that this “final chapter” includes the opportunity to live in a historically interesting city with some of the best cuisine and cultural traditions in the world makes it even more wonderful!

Q: Dr. Addleton, how has your global experience shaped your leadership style and approach to higher education?

A: I was fortunate to grow up and live much of my life as a “global nomad”. My early years in Pakistan were certainly a formative experience. But I have also lived and worked for lengthy periods of time in ten other countries: Afghanistan, Belgium, Cambodia, India, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Mongolia, South Africa, Yemen, and the United States. Each of these experiences have shaped me, both personally and professionally. Every time I moved to a new country, I viewed it as a “learning experience”. Among other things, those experiences have taught me the value of openness, curiosity, and empathy, qualities that are important with respect to both my leadership style and higher education.

Q: How do you balance global education standards with Pakistan’s unique cultural context?

A: The world is increasingly connected -- and those connections extend to higher education. Faculty at many Pakistani universities including Forman have earned advanced degrees from a wide range of countries and when they return to Pakistan to teach they bring those

experiences with them. Here at Forman, our professors have advanced degrees from at least 21 countries including the US, UK, Canada, France, Russia, China, Japan and South Korea, among others. Their experience in those many different countries also enriches our academic life. As far as standards are concerned, we seek accreditation with the various accreditation bodies in Pakistan. But we are also seeking a major international accreditation, with the New England Commission of Higher Education (NECHE), the same body that accredits Harvard, Yale, MIT and other prominent universities in the United States. In that sense, we strive to be a university uniquely situated in Pakistan yet offering an American-style liberal arts education while also meeting global standards of academic excellence.

Q: What valuable lessons from your international background have you applied to your role at FCCU?

A: I routinely draw on lessons from my career as a diplomat focused primarily on development. As a diplomat, that means working across cultural boundaries and seeking understanding among various countries, cultures and communities. As a former USAID officer, I managed programs and projects in a practical, hands-on way in a variety of settings, providing important leadership and management lessons along the way. Lessons based on that experience include the importance of being open and accessible while also ensuring a high degree of transparency; in addition, it is important to consult with a diverse range of stakeholders in any decision-making process, including most especially at the beginning of it.

Q: How do you balance your professional duties as Rector with your personal life? What hobbies do you enjoy?

A: I realized at the beginning of my time at Forman that serving as a university Rector is a full-time job, leaving little time for hobbies or even a personal life. The fact that my wife Fiona is from Scotland, shares my international perspective and has travelled the world with me helps a lot. We enjoy travel including visits to the various tourist sites in Pakistan. We also enjoy staying connected with our three children, all of whom have professional lives and families of their own -- our family call via Zoom each Sunday evening is one of the highlights of our week. As for hobbies, I enjoy reading, with a special interest in travel, history and memoirs.

Q: What is the most rewarding aspect of being Rector, and how do you define success in this role?

A: Personal relationships are important to

me and I find my personal encounters with students, faculty and staff among the most rewarding aspects of my life at Forman. In this context, it is especially gratifying to welcome and celebrate the success of others, both academically and in their personal lives. The realization that it is possible to make a positive difference in the lives of others also brings many rewards. Indeed, I would define success as the ability to make such a difference. Beyond that, I am firmly committed to the notion that my success depends and is reflected in the success of others.

Q: What advice would you give to students or young professionals aspiring to leadership roles?

A: From my perspective, empathy is one of the most important attributes of any leader, including among other things an ability to put oneself in the shoes of others and understand and appreciate the perspective of others. Beyond that, I would say that strong interpersonal skills and strong communication skills rank among the most important qualities of any leader anywhere. Finally, I view the Forman motto as an all-purpose motto, relevant at all times and for all people everywhere: “By Love Serve One Another”; if everyone lived that motto, the world would be a much better place!

Q: How do you stay connected with students despite your busy schedule? What do you enjoy most about interacting with them?

A: I walk to and from the office, providing an opportunity to meet and talk to students in an informal setting. I also often attend various student events, many of them sponsored by our 38 student societies, providing further opportunities to interact with students on a face-to-face basis. Learning more about their personal stories which are often stories involving faith, commitment, resilience and an ability to overcome obstacles rank among the most enjoyable aspects of these encounters.

Q: What do you believe is education’s greatest legacy? How has it shaped your personal and professional journey?

A: Higher education faces many challenges, both in Pakistan and around the world. Of course, we have to meet the needs of our students; and of course we have to change and adjust in the face of a rapidly changing world. From our perspective, we strive to instill empathy, critical thinking and a sense of service among all of our graduates. If we are successful in these areas, our legacy will be reflected in the lives of those students who shared in the Forman experience and who in turn make a positive difference in the lives of others. n

In Burj’s Clean Energy Modaraba,

The newest entrant on the GEM board has its eyes sets on the ultimate prize: capitalising on the gap in the market for financing of solar-power homes

By Ahtasam Ahmad and Hamza Aurangzeb

ater, water everywhere, nor any drop to drink” is a line from the poem The Rime of the Ancient Mariner by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, about a sailor stranded in the ocean, and thirsty. That line effectively describes the Pakistani economy: electricity, electricity everywhere, but prices too high to afford.

On paper, Pakistan has an abundance of electricity. Indeed, the country’s problem is that we have too much: electricity tariffs in Pakistan are sky high precisely because we have too much capacity that needs to be paid for, and is being paid for with a higher per-unit price.

This, in turn, has pushed Pakistan’s power sector towards a crisis of unprecedented proportions, one that is pushing consumers to their financial limits. With electricity tariffs reaching as high as Rs61 per kWh ($0.22)among the highest globally - many households now face the stark reality of electricity bills surpassing their monthly rent. This dire situation has prompted the government to explore various short-term solutions, including debt reprofiling and renegotiation of Independent Power Producer (IPP) contracts.

These high tariffs are occurring at a time when the price of renewable energy, specifically solar electricity, are plummeting, thanks in large part to a glut of solar panels that have been imported into the country. Data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics indicates that over $1 billion worth of solar panels was imported into the country in calendar year 2023.

High grid prices and low solar energy prices are creating an opportunity that many have dreamed about for a long time, but nobody has managed to push through until now: consumer financing for rooftop solar, including for residential consumers.

Pakistani investors - at least those with a liquid net worth higher than Rs5 million - will soon have the opportunity to invest in a company that is betting on exactly this opening in the market: the Burj Clean Energy Modaraba, which this past week was listed on the Growth Enterprise Market (GEM) board, the micro-cap public listing exchange operated by the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX).

So what is the market opportunity, and how will Burj capitalize on it?

Industry experts argue that the long-term solution for low-cost energy for Pakistan lies in a decisive shift towards renewable energy sources, particularly wind and solar.

Pakistan’s fundamentals for solar electricity have always been quite strong, with nearly the entire country enjoying well north of 300 bright sunny days every year, the sun is pouring free energy on Pakistani soil, if only we put up the panels to capture it.

And now, with Chinese production of solar panels ramping up, the cost of solar panels is finally low enough that solar electricity is not just cheap, but often the cheapest source of electricity available. Recent developments in the sector underscore this potential. A case in point is K-Electric recently receiving a bid at Rs8.92 ($0.032) per unit for a 220 MW hybrid wind-solar project, highlighting the cost-effectiveness of renewable energy compared to conventional sources.

This appeal of renewable energy is resonating with consumers as well. In the fiscal year 2023, Pakistan witnessed a significant surge in net-metering users, with their numbers nearly doubling and electricity generation increasing by an impressive 220% to 482 GWh. Despite this growth, net-metering still accounts for less than 1% of the country’s total electricity generation, indicating substantial room for expansion.

The primary obstacle hindering this growth is financing. In a nutshell, the cost of solar electricity is borne almost entirely upfront, meaning the only way to take advantage of it is to have the cash upfront to buy the equipment.

Both utility-scale projects and residential installations face significant financial hurdles. The absence of financial closures for large-scale renewable projects in fiscal year 2024, attributed to high country risk and the cost of capital, has accentuated the challenges in attracting investment. Similarly, residential solar installations, with costs ranging from Rs1 million to over Rs2 million, remain out of reach for the average Pakistani household.

Financing options, where a financial institution lends the money to a borrower for the

solar panel system up front and then gets paid back in monthly installments over time, seem like the logical solution to this conundrum. In response to these challenges, innovative financing solutions are emerging as potential game-changers. One such solution is the decision of Burj Clean Energy Modaraba (BCEM) to pursue a listing on the GEM board of the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX) to overcome the sector’s financing constraints. BCEM is Pakistan’s first renewable energy investment fund to be listed on the GEM Board, which will conduct operations in accordance with the principles of Shariah.

So, what do the sponsors aim to achieve through this listing, and is it a viable option? Profit explores.

Before analyzing Burj’s offering, a brief overview of the Modaraba sector in Pakistan is warranted. Modarabas are a key component of Islamic finance in the country, operating under a unique model that adheres to Shariah principles.

They can offer any financial product or conduct any business, but aside from analysing the business feasibility of the product, they also have to seek the approval of their Shariah Board and prove that what they seek to offer conforms to the standards of Islamic law. Funding sources for Modarabas include Certificates of Modaraba, Certificates of Musharaka, Sukuk, and Musharaka-based Term Finance Certificates.

Notably, at least as Pakistani regulations currently stand, Modaraba certificates must be listed on the stock exchange, ensuring transparency and market-based valuation.

These entities engage in various Islamic financial transactions, including Ijarah (leasing), Musharaka (partnership), Murabaha (cost-plus financing), and Istisna (manufacturing finance).

Source: IEEFA

We are operating this fund as a startup that has embarked on a mission to capitalize on the potential of an untapped market. Our institutional investors like Meezan Bank, HBL, and Arif Habib Limited are long-term partners who have strategically invested in our fund. They realize that power projects require mammoth upfront costs but will generate windfall profits in the long term

Talha Ameer, Deputy CEO, Burj Clean Energy Modaraba

As of December 2023, there were 22 Modarabas operating in Pakistan. However, the sector has experienced a contraction recently, with total assets decreasing from Rs66 billion in December 2022 to Rs57 billion in December 2023, representing a 13.6% decline.

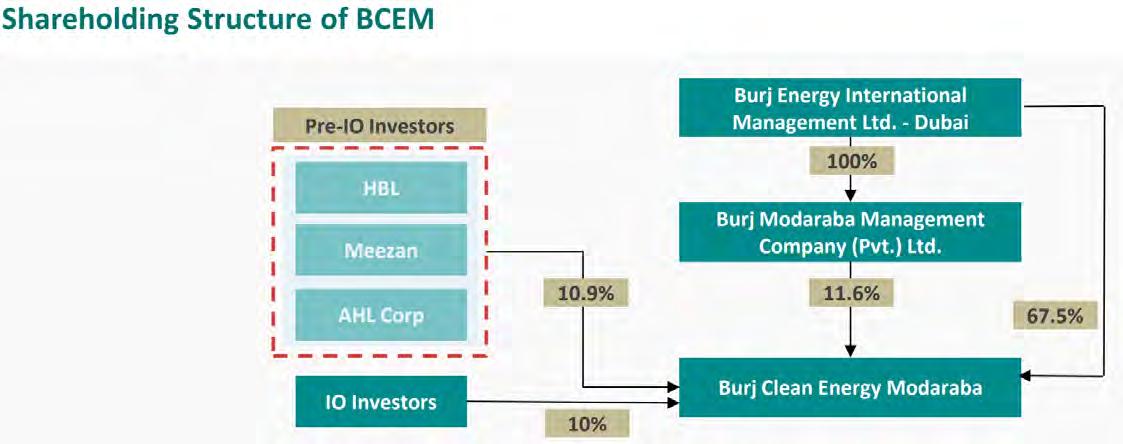

Now coming to Burj, recently approved by regulators and helmed by Dubai-based Burj Energy International Management Ltd., the Modaraba aims to catalyze the growth of Shariah-compliant clean energy financial products in Pakistan.

Set to debut on the Growth Enterprise Market (GEM) board, the micro-cap public listing exchange operated by the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX), Burj Clean Energy Modarabah’s Initial Offering was held on September 25-26, 2024, where 10% of its shares, worth Rs100 million, hit the market out of a total issue size of Rs1 billion.

The sponsors, with an aim of creating a unified platform, are rolling their developed assets into the Modaraba structure. These include a 50-megawatt (MW) Wind Power IPP project owned by JPL Holdings Pte. Ltd. and a 7 MW Solar Power project under Burj Solar Energy Pvt. Ltd.

Independent valuation by EY puts the val-

ue of BEIML’s 5.07% ownership of JPL Holdings at Rs572.2 million, while Burj Solar Energy is valued at Rs218.9 million for full ownership. This allows the sponsors to contribute 79.1% of the issue size to Modabraba through a share swap.

The Rs100 million raised will be channeled directly towards Solar Power solutions for residential consumers, developed in accordance with the Build-Own-Operate-Transfer (BOOT) model. Within six months of launching, the modarabah aims to deploy 71 residential sites with a combined solar capacity of 700 kW, with an average capacity per site of approximately 9.86 kW.

The BOOT model entails the developer designing and installing a complete solar power system on a homeowner’s property, retaining ownership, and managing its operation for a set period in return for a fixed rental. At the end of the period, the assets are transferred to the homeowner. For Burj, this model enables rapid deployment across multiple sites, accelerating market penetration while generating steady revenue.

As far as the returns are concerned, Burj projects steady revenue from a specific number of residential sites. In parallel, the growth of Commercial & Industrial solar projects is forecasted to generate a steady revenue stream through monthly rental fees, determined by the installed capacity.

And what is in it for the investors? A quick analysis of the PSX reveals that the weighted average dividend yield of the modaraba segment is 9.52%, if the Burj Clean Energy Modaraba is able to offer a similar return, let’s say a 10% dividend yield, it will be a decent return considering PSX.

This whole structuring method allows Burj to finance hard infrastructure costs through mobilizing private capital rather than its equity thus, significantly reducing its risk. Furthermore, it also enables the company to reduce its liquidity risk to a considerably low level by being listed.

Concurrently, the fund also plays the role of a market maker through attracting institutional investors to the power sector, a frontier they have traditionally avoided. While also channeling resources of retail investors into the sector.

“We are operating this fund as a startup that has embarked on a mission to capitalize on the potential of an untapped market. Our

institutional investors like Meezan Bank, HBL, and Arif Habib Limited are long-term partners who have strategically invested in our fund. They realize that power projects require mammoth upfront costs but will generate windfall profits in the long term,” remarked Talha Ameer, Deputy CEO, Burj Clean Energy Modaraba

As explained earlier, Pakistan’s solar market is experiencing a surge of interest, with consumers increasingly drawn to the idea of shifting to the cheaper off-grid source.

However, a significant hurdle remains: financing. Despite the growing enthusiasm, commercial lenders in Pakistan, particularly banks, view loans for distributed energy solutions with the same wariness as unsecured personal loans.

This skepticism stems from the nature of the assets involved. While traditional loans often rely on immovable assets with strong resale value as collateral, distributed energy equipment like rooftop solar panels present unique challenges. These systems can be uninstalled, relocated, and typically have lower resale value. Moreover, they are installed on private property, making them difficult for lenders to access or repossess if needed.

On the developer side, small and local players often find themselves at a disadvantage when it comes to financing small-sized projects. Their primary hurdles? A lack of institutional history and limited local equity. Financial institutions, particularly banks, tend to err on the side of caution.

They typically favor well-established contractors with proven track records, solid credit histories, and robust supplier networks. This risk-averse approach, while understandable from a lending perspective, inadvertently creates a barrier for players opting for smaller scale, specially residential projects.

Therefore, structures similar to Burj’s modarabah can help finance these projects getting around typical financing hurdles while also aggregating projects to make them eligible for both institutional investors in line with their minimum investment ticket size.

Further, given the long-term and fixed nature of contracts, it is easier to predict future

cash flows and returns, reducing volatility.

While BCEM appears to offer an attractive investment opportunity, it comes with a significant downside risk inherent to its BOOT model. The success of this model hinges on the customer honoring the Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) for the entire project tenure, as this is crucial for recovering the invested capital.

To illustrate this, consider a hypothetical 2 MW off-grid project with a 10-year tenure, after which the project transfers to the customer. The total project cost is approximately Rs193.4 million, with Rs38.7 million invested by the developer for a fixed 15% return. The remaining Rs154.7 million is financed through debt at 6% under the now-lapsed SBP concessional financing scheme. Additional costs include annual operations and maintenance (O&M) at Rs3 million and insurance at Rs0.33 million.

In this scenario, the developer assumes risk by investing 20% of the project’s capital cost

However, the bank, as the primary financier, bears the majority of the risk by lending 80% of the project cost.

The repayment of principal is spread over the project’s lifetime, leaving the lender exposed to significant losses in case of power purchase agreement (PPA) breach. This is not uncommon in a market like Pakistan where, in most cases, the only buyer of electricity is the government of Pakistan, which has a tendency to not honour the terms of its contract with power companies.

In the case of private sector borrowers, the issue may not be political decision-making with respect to energy contracts, but nonetheless, the ability or willingness to pay the tariffs agreed to in the contract cannot be taken for granted. That, in turn, introduces significant risk for a lender that finances energy projects, which is essentially the business that Burj is entering.

For instance, if the PPA is breached at the end of year 3, the lender stands to lose Rs117.5 million in principal. This loss reduces to Rs88.8 million if the breach occurs at the end of year 5, and Rs56.4 million if it happens at the end

of year 7, assuming zero scrap value for solar assets.

This substantial risk also sheds light on the reluctance of banks to lend for such projects, especially for extended tenors. Burj acknowledges these risks in its information memorandum, citing potential defaults in PPA and rental payments, as well as risks related to asset possession, misuse, accidents, theft, and breakdowns.

To mitigate these risks, Burj’s management claims to have implemented several strategies. These include careful customer selection, the reduced energy costs incentivizing compliance, active credit risk management, and portfolio diversification.

While the success of investments in the newly formed modarabah remains to be seen, this development marks a significant stride towards cultivating the capital market’s appetite for longer-term, higher-risk investments.

Ultimately, however, what makes the problem a difficult one to solve is this: a renewable energy focused consumer finance company needs to be good both at the operational task of installing and maintaining solar panel systems and have the muscle to be a consumer lender that is good at assessing the creditworthiness of individual borrowers in a country where adequate information about credit risk on individuals is still relatively scarce.

Those are two very different business models that nonetheless need to be integrated into a single company in order to for this business to succeed. To invest in Burj’s modaraba is to bet on the idea that they have what it takes to make this industry take off. n

By Zain Naeem

Few industries have experienced the level of upheaval witnessed by tobacco, a sector that has undergone not merely an evolution but an outright revolution. Decades ago, lighting up a cigarette was a common sight—on airplanes, in offices, even in restaurants. Today, the scene has shifted dramatically. In many places, smoking is confined to shadowy corners, banished from most public spaces, and under constant siege from regulators and anti-tobacco advocates. The global sentiment has shifted, and Pakistan is no exception. The landscape for tobacco companies in the country, once dominated by advertisements plastered across billboards and televisions, is now shaped by an entirely different set of challenges—chief among them, government-imposed taxes and the scourge of illicit trade.

This changing environment is especially tough on the two multinational giants that dominate the market in Pakistan: British American Tobacco (operating as Pakistan Tobacco Company) and Philip Morris International. Together, they control a whopping 90% of the market share, leaving a mere 10% for small, local players, many of whom have set up their own manufacturing units. The multinational corporations (MNCs) argue that they

As illicit trade rises and local taxes increase, Pakistan’s tobacco giants are being pushed to look beyond borders

shoulder the brunt of the industry’s tax burden while local manufacturers, along with illegal smuggling operations, evade taxes entirely. The consequences of this imbalance are now coming to a head. Facing shrinking margins in the local market, tobacco companies have increasingly turned their gaze outward. Pakistan, the seventh-largest producer of tobacco globally, is witnessing a shift in strategy: cigarette exports are surging as local sales stagnate. But is this pivot a voluntary business decision or the inevitable result of a hostile domestic market?