24 20 14

24 20 14

09 Can Pakistan get its spectrum strategy straight?

12 Coke and Pepsi (to name just two) took a hit from the BDS movement. Local brands bottled the opportunity

20 Pakistan’s electric bike market: breaking through or breaking down?

24 Can this grand-old Pakistani company make a comeback?

27 Are matchmaking events disrupting the rishta aunty business?

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz Khan - Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Editorial Consultant: Ahtasam Ahmad - Business Reporters: Taimoor Hassan | Shahab Omer

Zain Naeem | Saneela Jawad | Nisma Riaz | Mariam Umar | Shahnawaz Ali | Ghulam Abbass

Ahmad Ahmadani | Aziz Buneri - Sub-Editor: Saddam Hussain - Video Producer: Talha Farooqi Director Marketing : Mudassir Alam - Regional Heads of Marketing: Agha Anwer (Khi) Kamal Rizvi (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) - Manager Subscriptions: Irfan Farooq Pakistan’s #1 business magazine - your go-to source for business, economic and financial news. Contact us: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

By Ahtasam Ahmad

Pakistan stands at a pivotal moment in its digital journey, with mobile network infrastructure serving as the backbone of its technological transformation.

Since the launch of Digital Pakistan in 2018, the nation has made remarkable strides, yet faces critical challenges that will define its digital future.

The progress is evident in the numbers: 83% of Pakistan’s adult population now lives in areas covered by 3G or 4G networks, a

A new GSMA analysis highlights Pakistan’s spectrum opportunities

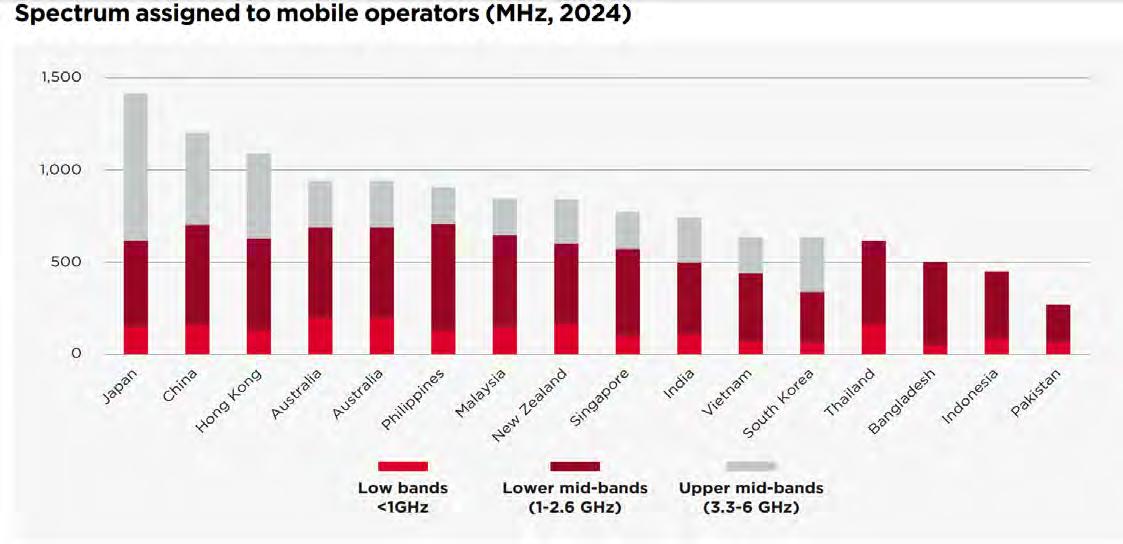

dramatic increase from just 15% in 2010. This expansion represents a fundamental shift in Pakistan’s digital landscape, but the country’s position as one of Asia’s most spectrum-starved markets threatens to undermine this progress. With only 270 MHz of assigned spectrum, Pakistan lags significantly behind the Asia Pacific average of over 700 MHz, placing it among the most constrained markets in the region.

In response to this critical shortfall, the Pakistan Telecommunication Authority (PTA) is preparing for a landmark spectrum auction in early 2025. The auction will make available

nearly 600 MHz of spectrum across multiple bands - including 700 MHz, 1800 MHz, 2.1 GHz, 2.3 GHz, 2.6 GHz, and 3.5 GHz. However, this expansion comes against a backdrop of historical challenges in spectrum allocation and utilization.

The economic stakes are staggering. GSMA Intelligence projects that a two-year delay in spectrum availability could cost Pakistan USD 1.8 billion in GDP over 2025-2030, while a five-year delay could result in losses of USD 4.3 billion. These aren’t merely theoretical projections - previous auction failures have already cost the economy an estimated USD 300 million in lost benefits, primarily due to prohibitively high reserve prices deterring bidders.

The technical complexities of spectrum allocation add another layer of challenge. The physics of radio waves means that lower frequencies around 800 MHz offer superior building penetration and coverage with lower power requirements - crucial for indoor cover-

age and rural areas. Higher frequencies provide greater capacity but require more infrastructure. The 1800 MHz band has emerged as the sweet spot for 4G deployment, offering an optimal balance between coverage and capacity. This technical reality makes the distribution of spectrum particularly crucial for efficient network deployment.

The market landscape is undergoing significant transformation. Currently, Jazz leads with 34.5% of the retail mobile market spectrum, followed by Zong at 24.5%, while

Ufone and Telenor control 20.1% and 20.9% respectively. The proposed Ufone-Telenor merger could dramatically reshape this landscape, creating a new market leader controlling 41% of total retail spectrum. Post-merger, the combined entity would possess the largest shares across two critical frequency bands900 MHz and 2100 MHz - while maintaining a strong second position in 1800 MHz and exclusive access to 850 MHz.

Historical auction performance raises red flags. Both the 2014 auction (850 MHz, 1800

Source: GSMA

MHz) and 2021 auction (1800 MHz, 2.1 GHz) resulted in unsold spectrum, primarily due to high reserve prices. This pattern has contributed to slower 4G rollout and adoption, creating a cycle of delayed digital development that affects the broader economy.

The macroeconomic context adds further complexity. Pakistan faces high inflation, currency depreciation, and rising energy costs, all of which affect consumer spending and increase operating costs for telecom operators. These challenges make it crucial to structure

Source: GSMA

the upcoming auction to prioritize long-term digital infrastructure development over shortterm revenue maximization.

Looking toward solutions, GSMA recommends several critical policy interventions. Reserve prices must be set conservatively across all bands, significantly lower than in previous auctions. Spectrum fees should be denominated in Pakistani rupees to shield operators from currency fluctuations. Payment flexibility should be introduced through installment options. License obligations should be carefully considered, with their costs offset against spectrum fees.

Moreover, the government should commit to a clear spectrum roadmap to reduce uncertainty about future availability and aid

network planning. This roadmap should align with international best practices while accounting for Pakistan’s unique market conditions. The technical standards and deployment requirements must be clearly defined to ensure efficient spectrum utilization.

The upcoming auction also presents an opportunity to address infrastructure sharing and optimization. With the potential merger creating a stronger third player, policies encouraging infrastructure sharing could help maintain competitive balance while improving network efficiency. This becomes particularly important as Pakistan aims to expand 5G services in the coming years.

Success will require balancing multiple objectives: expanding digital access, ensuring

market competition, maintaining operator viability, and accelerating technological adoption. The decisions made about spectrum allocation in the coming months will reverberate through Pakistan’s economy for years to come, potentially determining whether the country can fully realize its digital ambitions or remain constrained by infrastructure limitations.

As Pakistan positions itself for the next phase of digital growth, the path chosen in spectrum policy will largely determine its success in bridging the digital divide and fostering innovation. The stakes extend far beyond the telecommunications sector, touching every aspect of Pakistan’s digital transformation agenda and its position in the global digital economy. n

Source: GSMA

By Abdullah Niazi

This publication believes in the non-violent global Palestinian Boycott Sanction and Divest (BDS) movement. As a matter of editorial policy, we hold that efforts to boycott certain companies in a targeted attempt to exert economic pressure on them for supporting Israel at a time when it is embarking on a relentless genocide in Gaza and The West Bank is an effective mode of resistance. More importantly than the effectiveness of such methods, we believe in the moral merit of boycotts simply because it is one of the foremost popular demands made by the Palestinian people.

We also believe in understanding what this movement means, and what it asks of global civil society. Founded in 2005, BDS is a successor movement. It is modelled on a method of targeted boycotts inspired by the South African anti-apartheid movement, the US Civil Rights movement, the Indian and the Irish anti-colonial struggles, among others worldwide. It is non-violent, and believes that when it comes to corporations, consumer choice is a weapon that can be wielded to great effect.

The concept is simple: there are corporations all over the world that do business with Israel. Some of these companies are harmless while others provide key technology and equipment that is directly used for the subjugation of the Palestinian people. The idea is for individuals all over the world that support the end of Apartheid in Palestine to boycott these companies, and hopefully hurt the businesses of these corporations enough for them to notice and change their policies.

The question is, does it work? There are examples of boycott movements exerting significant pressure on corporations in countries like South Africa and Ireland. BDS itself has had its own victories, both big and small, over the past two decades. Since October 2023, when the brutal invasion and subsequent bombing of Gaza began, there has been increased interest in the BDS movement which has picked up steam in different parts of the world.

It has also done so in Pakistan. But Pakistan holds a strange position when it comes to the BDS movement. On the one hand, it is the second-largest Muslim population in the world and has historically been a staunch ally of the Palestinians. But the actual global impact Pakistan can contribute to the BDS movement is minimal simply because it is not a large enough market.

There has been a loose, disconnected effort to boycott companies perceived as foreign and as such complicit with Israel. This has re-

sulted in unfortunate incidents that go against the spirit of the movement such as the burning of a KFC (which is not even on the movement’s list) in Mirpur. Largely, the boycott sentiment in Pakistan remains disconnected from the global BDS movement, particularly since most of the major tech and engineering corporations that are the primary focus of the BDS movement either do not have a presence in Pakistan, or are not household names. This means that boycotts in Pakistan have largely targeted foreign fast food franchises such as McDonalds, and brands such as Coca Cola and Pepsi.

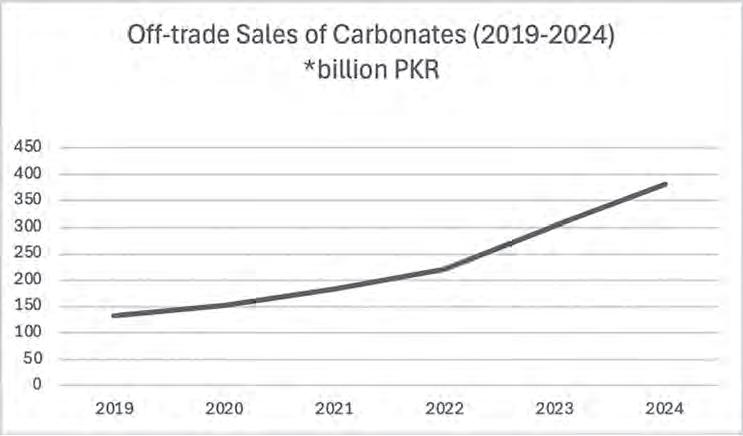

While the numbers for all sectors are not available, a recent report by Euromonitor on Pakistan’s carbonated drinks segment shows a significant dip in sales for both Pepsico and Coca Cola. In fact, the total volume of sales of these brands has shrunk in 2023 and 2024, falling by nearly 20%. However, local brands have failed to capitalise on this the way they could have. Caught unprepared, even though the total volume of sales for carbonates has fallen, the market share of Coca Cola and Pepsi has only fallen by about 2%. People are simply drinking less soda in Pakistan since the local alternatives have not managed to bridge the gap.

Conversations with industry insiders further reveal the extent of pressure these companies faced in the early days following October 2023. Distributors and executives claim they had a much larger chunk of their market share taken away in the initial few months. Another industry insider tells us that international franchise restaurants like McDonald’s and KFC saw dips of more than 40% in their sales almost overnight. Conversely, as all of these different sources also concur, these losses have been recovered for the large part. Most of the lingering effects can be found in Karachi and KP, with the market in Punjab

recovering well.

What does any of this mean for Pakistan and for the global boycott movement? Pakistan is, to put it frankly, what we would call small fry. Within carbonated drinks, Pakistan is not a particularly large or profitable market. The same is true for franchise restaurants. The question of whether to boycott or not in Pakistan is largely a moral and personal one rather than a practical one. Profit looks at the BDS movements, its impact in Pakistan, and the small difference that this movement has had on the country’s carbonated drinks market.

The BDS movement is modelled after the Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM) that originated in the United Kingdom. It was founded in 1956 by South African exiles that had escaped the Apartheid regime. With the blessing of Nelson Mandela, its message was very simply explained Julias Nyerere, the future President of Tanzania in these words: “We are not asking you, the British people, for anything special. We are just asking you to withdraw your support from apartheid by not buying South African goods.”

This was in a country that refused to sanction the Apartheid regime until the very end. Even when the Reagan Administration sanctioned the Apartheid Regime in 1986, Margaret Thatcher remained a staunch ally, and the British Government would continue this policy until the end of Apartheid in 1994. Action against apartheid in Britain came only from the AAM. Over time, it gained great support from students, trade unions, small businesses, local governments, and the Labour Party, which sat on the opposition benches from 1979-1997, among others.

It was a movement that took root fast

and was startling in its effectiveness. Ordinary Europeans pressured supermarkets to stop selling South African products. British students forced Barclays Bank to pull out of the apartheid state, which led to nearly all international banks in South Africa calling in their loans in 1985. The refusal of a Dublin shop worker to ring up a Cape grapefruit led to a strike and then a total ban on South African imports by the Irish government. By the mid-1980s, one in four Britons said they were boycotting South African goods – a testament to the reach of the anti-apartheid campaign. In fact, it was the AAM which led protests that excluded South Africa from the 1964 Tokyo Olympics and ended cricketing ties between South Africa and the rest of the world in 1968.

The movement was highly influential in the three-decade long struggle to squeeze the apartheid regime to a point of no return. The origins of BDS can be traced back to a meeting in Durban of the World Conference Against Racism, where Palestinian activists met anti-apartheid veterans who recommended a concerted campaign of boycotts to deal with the Israel situation. Over time, the BDS movement has created a list of corporations and companies for the global community to boycott.

Much like the AAM, the BDS movement boycotts all Israeli companies, but they have gone beyond this as well. The movement has shortlisted a number of multinational companies that they feel are complicit in the subjugation of the Palestinian people and to their right of return. Many of these are tech companies. The main targets of the BDS boycott are Chevron (which operates Caltex), Intel, Dell, the engineering company Siemens, Hewlett Packard (HP), the French retail giant Carrefour, Sodastream, and Disney+.

These are the companies investing in Israel, providing them with vital resources, participating in the construction of settlements in the West Bank, and signing contracts directly with the Israeli Military. Most of these do not have any kind of manufacturing or direct sales in Pakistan. Yes, laptops and other devices from HP, Dell, and Intel chips are available in Pakistan, but there is no way to consolidate data about the effects this has had on their sales here. One of the companies with a significant presence in Pakistan is Carrefour, which manages groceries for a number of large shopping malls and centres in different parts of Pakistan. However, there is little recognition that these companies are the main target of the BDS movement.

Focus, instead, is often put on companies like McDonalds, Coca Cola, and Pepsico. These are well known and recognised symbols of the West, and have naturally become a target for a population sympathetic to the

Palestinian cause that has few avenues to contribute to the boycott. The BDS movement does support boycotts of McDonalds, Coca Cola, Papa Johns, Pizza Hut, and a few more multinational food companies, but categorises them as “organic boycotts supported by the BDS movement.”

This means the movement noticed people naturally boycotting these companies, and thought there was enough culpability on their part to encourage the boycotts to keep happening.

This is really where we are on the boycott movement in Pakistan. It is a matter of perception, and in many instances it is misguided. Profit spoke to a number of Palestinian students both from Gaza and the West Bank that are studying in Pakistan. The foreign ministry regularly offers scholarships to Palestinians to study as doctors in Pakistan. The sentiment within these individuals was that while most of their peers were supportive of sanctions and boycotts, they did not know how they worked, and were indiscriminate and random in their efforts.

“Most of the anger and action comes against recognisable names. While this is all good, it is not the purpose of the movement” says Rashad Ayaydah, a medical student from Hebron in the West Bank.

The question of boycotting companies in Pakistan is a complicated exercise. On the one hand, you have a global demand by Palestinians for people all over the world to boycott certain companies. On the other hand, it is natural to wonder what kind of effect this will have on these companies. Take McDonald’s for example. It is one of the companies on

the official BDS list. Pakistan has a total of 79 McDonalds outlets all over the country out of a global total of nearly 42,000.

That accounts for less than 0.2% of all the McDonald’s franchises in the world. What is more, Pakistan has very few McDonald’s franchises compared to countries with similar demographics. Japan has a population of 12.45 crore compared to 24 crore people in Pakistan. There are nearly 3000 McDonald’s in Japan in comparison, representing around 7% of global franchises.

Hypothetically, even if all McDonald’s branches in Pakistan closed down, it would have little effect on the parent company, which does not make a whole lot of money in Pakistan anyways. Meanwhile within Pakistan the consequences would be severe. McDonald’s in Pakistan is a locally owned company. Yes, they pay royalties to the McDonald’s headquarters, but the owners and ultimate profiteers of these restaurants are Pakistani, and likely have their heart in the absolute right place when it comes to the Palestinian cause. Similarly, if McDonald’s in Pakistan were to shut down, the effects would go beyond to all of its employees, to the Pakistani companies that supply McDonald’s with chicken, vegetables, ketchup and many other items.

As we mentioned at the beginning of this report, franchise restaurants such as McDonald’s and KFC saw sales fall by as much as 40% in the initial months following the invasion of Gaza. This amounts to a very marginal effect on the international sales of McDonald’s. What is the point then? The idea is to boycott anyways. To create headlines, pressure, and panic within these corporations. So if McDonald’s sees its franchises suffering in Pakistan, and then sees the trend spread to Egypt, Malaysia (where McDonald’s has sued the BDS movement for millions of dollars

in damages), Ireland and other countries sympathetic to the Palestinian cause, they will eventually have to take notice. For corporations like these, Pakistan is part of very large emerging markets that they want to tap into.

And then there are other areas where Pakistan can have an effect. Carbonated drinks are a cheaper product that have a wider market in Pakistan. In this way, they are sort of like cigarettes: they have universal appeal and demand among most segments, even in developing countries.

Overall, the market for carbonated drinks is massive. Every year, around 194.5 billion litres of carbonated drinks are sold all over the world. Pakistan contributes close to 1.5 billion litres of this annually, all brands and manufacturers included. This is less than 1% of the overall total, so Pakistan is not a very big market. However, it is a significant player in the Asia-Pacific market where it makes up around 5% of the total consumption.

Something interesting has been happening to Pakistan’s carbonated drinks market in the wake of the boycott movement. The two biggest players in Pakistan are Pepsico and Coca Cola. Much like McDonald’s, both of these companies are symbols of the West. It is ingrained in their histories. The truth is that there isn’t really any major competition to Coca Cola and Pepsi. Sure, there are a few anomalies in the world where local brands compete with the two multinationals. In fact, Peru is possibly the only country in the world where a local soda seller, Inca Cola, outsells both Coca Cola and Pepsi. But these are all outliers. Everywhere in the world the market for carbonated drinks is almost evenly split between these two Global Giants.

Pakistan is no exception. Coca Cola first hit the Pakistani market way back in 1953. Pepsi followed not long after. The logic from the global headquarters of both Coke and Pepsico is simple. Since they are each other’s eternal competition, wherever one goes the other follows. Whatever pricing strategy one follows the other copies. However much one spends on marketing, the other tries to oneup. Wherever there is Coca Cola, there must be Pepsi.

And sure, both companies have a whole host of other products too. Mirinda and Fanta in the orange soda category, and Sprite and 7Up in the lemon soda category are the most recognizable brands. But the main event is always between Pepsi and Coca Cola. In Pakistan, Pepsi has almost always had a bit of an edge. Regional preferences within the country

have differed for long periods also because of the supply lines that the companies maintain. Coca Cola has significant presence in Punjab, while Pepsi has a strong foothold in Sindh and KP, particularly off the back of the success that has been found by their Pakistan Beverages Limited franchise in Karachi. This is because Coca Cola has five out of six of its production facilities in these provinces while the sixth and smallest is in Karachi. Pepsico, on the other hand, has significant production facilities in Karachi. As per a report seen by Profit, Pepsico generally partners with one distributor per city, while Coke Pakistan has multiple distribution partners within a city, with areas divided according to sales volume. It is worth looking at the sales numbers of these companies over the past few years. Last year, Profit reported that in 2023, 1.33 billion litres of carbonated drinks sold in Pakistan last year. This included all drinks produced by Coca Cola Pakistan and Pepsico, as well as carbonated drinks produced by local manufacturers such as Gourmet Cola and Cola Next. The leading company in this entire mix was Coke Pakistan, which sold nearly 567.5 million litres of carbonated drinks. Pepsico sold just over 528 million litres of carbonated drink, giving them a total market share of 39.2% compared to Coke’s 42.7%.

The total sales of carbonated drinks in Pakistan for 2023 stood at an even Rs 303 billion. In terms of revenue, Coca Cola had sales worth nearly Rs 129 billion. In comparison, Pepsi had sales worth just over Rs 120 billion. Local competitors were small participants in this pie. Gourmet Cola sold some 23 million litres of carbonated drinks, Mehran Bottlers, which makes Pakola, sold around 18 million litres of carbonated drinks, and Meezan, which makes Cola Next, sold only around 6.5 million litres of carbonated drinks. Other even smaller

local manufacturers made up the remaining amount. Overall, all local manufacturers accounted for just around 17% of all carbonated drinks sold.

Now compare these numbers to the year before. In 2022, the sales revenue was significantly less for everyone involved. The total earnings for the entire industry from that year were Rs 221 billion compared to Rs 303 billion in 2023. However, the actual volume of sales fell in 2023 compared to 2022. In fact, it fell by a significant margin. In 2022 the total volume of sales for carbonated drinks was 1.64 billion litres. This fell by over 300 million litres to 1.33 billion litres in 2023. The discrepancy is for obvious reasons. Inflation increased in Pakistan, which is why companies made more revenue despite posting fewer sales. But there might be more to this data. Inflationary pressure has been ongoing in Pakistan since at least 2019, and also spiked during Covid-19 and also in 2021. Despite this, the total volume of sales never fell. In fact, sales have been steadily increasing in this segment for years. Data from Euromonitor shows increasing sales volumes for carbonated drinks since at least 2009, when total volume was just over 500 million litres.

Now fast forward to 2024, and what is the picture that we have? Well, for starters, both revenue and volume of sales have increased compared to 2023. The total revenue from sales increased to Rs 381.7 billion, but most of this can be accounted for by inflation, since carbonated beverages all say a hike in price. The volume of sales has also increased from 2023 and has gone from 1.33 billion to 1.35 billion. This is a very moderate increase, and does not come close to the growth rate pre-2023. What is even more telling is that the sales volume has not gone back up to the 1.6 billion litre mark that they had hit back in

2022. For all intents and purposes, the carbonated drinks market has lost close to 20% of its entire market.

This is the point at which we must make some assumption that might explain these numbers better. In 2023, we suddenly see a dip in sales volume for carbonated soft drinks close to 20%. While the exact month-by-month data is not available, our sources within the industry tell us most of the dip came after October. Yes, inflation had a part to play, but these companies had been on the track to achieve growth, as they have every year for decades now. And as we have seen from the fast food industry, the immediate impact on sales was quite large.

It is safe to assume that as a result sales fell for carbonate manufacturers. Now here is the rub. Alternatives were and still are available, but they were not prepared to fill such a large gap. As a result, it seems consumers simply stopped drinking carbonates and the market shrunk. Look at it this way. In 2023, the total sale of carbonates fell by some 300 million litres. In 2024, this rose again by another 20 million litres. In this growth, a number of players from the local cola manufacturing industry were winners. Particularly Cola Next.

In 2023, Cola Next had been a relatively small player with a sales volume of 6.5 million litres. In 2024, they became the largest local manufacturer of carbonates with nearly 23 million litres in volume of sales. This increase of 16.5 million litres makes up the lion’s share of the overall increase in 2024. Others like Gourmet Cola and Pakola also saw increasing sales, and made up nearly all of the remaining 3.5 million litres. Meanwhile the sales volume for Pepsico fell, while it remained nearly stagnant for Coca Cola.

This gives us a very clear picture of what has happened. After October 2023, Pakistanis began boycotting Coca Cola and Pepsico. Even though they remained market leaders, this affected their overall volume of sales by close to 20%. The effects were felt more strongly by Pepsico. This is because Pepsico has a stronger presence in KP and Karachi, where people seem to have taken the boycott more seriously. In 2024, local manufacturers introduced alternative products which immediately soaked up some of the missing demand. However, none of the local manufacturers were ready.

One manufacturer tells us they could not compete with the distribution network of the MNCs, which they have carefully cultivated over decades. The Euromonitor report we

have used for data points towards the same. “Heavyweights in the carbonates category includingThe Coca-Cola Companyand PepsiCo Inc have faced substantial revenue declines since the boycott movement began in Pakistan. Consumers have developed a preference for local or alternative drinks that severely impacted the retail presence of international soft drink brands. Brands like Gourmet Cola, Cola Next,and Quice Colasaw a massive increase in demand for their products and were unable to fulfil requirements with existing supply. Traditionally, local players only supplied carbonates to Tier 2 cities, but products have now become available in major cities like Karachi, Lahore,and Islamabad,” it reads.

“Patrioticsentimentsare drivingthe boycottand may foster long-term loyaltyamong local brands, especially as consumers feel a sense of pride in supporting domestic products. Cola Next started using a tagline that loosely translates to “Because Cola Next is Pakistani” while Gourmet Cola used a new tagline “Our Gourmet Cola”in their marketingadvertisingin July 2024. Kababjees Group,a local foodservice company based in Karachi, entered the carbonates industry by introducing its Colacans through its own outlets,Foodpanda,and e-commerce channels.This move signifies the growing competition among local players against the established giants with deep pockets and extensive distribution networks.”

That is where the situation sticks. The only local brand to really capitalize on this opportunity was Cola Next, and even they barely filled what is a significant hole. Local manufacturers were simply not ready for this, and they probably did not expect the level at which people would be boycotting. But this leaves an all important question. What now?

We come back to where we started off. For this story, Profit has taken a very strong editorial stance on the issue of boycotts. It is clear that Pakistan as a member of the international community is not in a position to affect major change, but it is a participating player that can have some semblance of an impact. What is important is to recognise the goals of the movement. It is far more important to boycott major companies like HP, Dell, Intel, Caterpillar, Siemens, and Carrefour that are the main targets of this movement as well as any Israeli businesses.

Companies like Coca Cola, McDonald’s, Pizza Hut and others are on one of the lists, but are not the main target. There is also an argument to be made for the effect this will

have on the workforce of these companies and other businesses that are their suppliers. Some might say this would do more harm than good in the long run. It is important to know that many of the local subsidiaries of these companies in different parts of the world have distanced themselves from the actions of their sister companies in other parts of the world. McDonald’s Pakistan also released a statement to this effect, and even donated money for humanitarian relief in Gaza. The same is likely true for the management and local beneficiaries of other companies in Pakistan. Their sentiments will be in the right place, and it depends on how effective one thinks boycotts are. The question of which company to boycott and which not to is entirely a personal one. What we can do is look at some of the effects BDS boycotts have had all over the world.

In February 2024, Starbucks CEO Laxman Narasimhan told analysts over an earnings call that the world’s largest coffee chain was reporting slower sales in the first month of 2024, causing a hit in its share price. “We saw a negative impact to our business in the Middle East,” he said, adding that “events in the Middle East also had an impact in the U.S., driven by misperceptions about our position.” The report came a few days after McDonald’s also sharply missed analyst expectations when it reported slower sales across its international licensed division at the end of December. The burger chain similarly attributed the slowdown to a drop in demand in stores in the Middle East and predominantly Muslim countries like Indonesia and Malaysia.

This has been in the current wave of boycotts. In the past, the BDS movement has been successful in ending the involvement of certain major companies in Israel. In 2016, one of the world’s largest security companies, G4S, spent $110m worth of its investment in its Israel subsidiary. That would consist of selling most of its Israeli business, after an effective campaign against the company waged by BDS. The movement has also been successful in getting universities to cut ties with Israel, convincing local councils across Europe to join BDS, and had factories in the occupied West Bank shut down permanently.

What we know in the case of Pakistan is that the years 2023 and 2024 were not great for big international players in Pakistan for fast food and carbonates. In response, the local industry has tried to fill the gap but did not have the supply chain to manage such a task in the time they had. As of now, it seems things are going back to normal for these players. Local competitors will likely continue to stake more of a claim than before, but with a ceasefire in hand in Gaza, the movement might lose steam in the days and years to come. n

By Ahtasam Ahmad

Pakistan’s electric two-wheeler market is experiencing a boom that’s impossible to ignore. Over the past six months, the electric mobility segment has gained remarkable traction, generating both inspiration and surprise across the industry. This momentum was particularly evident when ZYP Technologies, an EV two-wheeler startup, secured $1.5 million in venture funding during Q3 2024 – a significant achievement in what has been widely considered one of the

most challenging years for startup funding.

The two-wheeler market holds a dominant position in Pakistan’s transportation landscape, with approximately 30 million motorcycles currently on the roads and annual sales reaching 1.5 million units. This established foundation has created fertile ground for electric alternatives, which are rapidly gaining market share.

The growth of electric two-wheelers is reflected in the numbers: industry insiders report approximately 50,000 electric motorcycles are already in use across the country. The Pakistan Electric Vehicle Association (PEVA) notes that about 40 EV motorbike brands

with original designs have entered the market, achieving monthly sales of 3,000 units. Looking ahead, the government has set an ambitious target to capture 30% of the market share for EV bikes, aiming for annual sales of 500,000 units by 2028.

Recognizing this potential, the government’s new EV Policy 2025-2030 that is still in the works, proposes comprehensive measures targeting the crucial two-wheeler segment and charg-

ing infrastructure. The policy recommends a tiered customs duty structure that balances local manufacturing promotion with market affordability. EV-specific parts will attract only 1% duty throughout the policy period, while next-generation vehicles like e-scooters and e-bicycles face a graduated approach, with duties on non-localized parts starting at 5% and rising to 15% by the third year.

The charging infrastructure development is likely to receive particular attention, addressing both urban and highway requirements. In urban areas, the focus is on accessibility and convenience, especially for two-wheeler owners who lack home parking or electricity access. The policy offers subsidized electricity rates for parking lots converting to electric-only facilities. On highways, charging stations are proposed to be installed every 50km, creating a dense network for long-distance travel. To accelerate infrastructure deployment, the policy introduces significant financial incentives. High-power DC chargers (50kW and above) can receive capital subsidies up to PKR 2,000,000, while lower-power chargers qualify for PKR 60,000.

The policy strongly emphasizes indigenous manufacturing through strategic duty structures. Complete Built Units (CBUs) of EV two-wheelers will face a 50% customs duty, encouraging local assembly and production. To support this transition, locally manufactured NEVs will benefit from a reduced 1% sales tax, while NEV-specific parts in CKD form will enjoy zero sales tax. This approach aims to make local production more economically viable while building domestic manufacturing capability.

What works and what doesn’t

The economics of adoption present a compelling case for consumers. Profit’s cost analysis comparing traditional and electric options shows

e-bikes as the clear winner for budget-conscious consumers. Taking a standard 70cc Honda motorcycle as the baseline and comparing it with an electric bike priced at Rs. 225,000, the financial advantage becomes evident. Over a five-year period, the traditional petrol-powered bike accumulates a total ownership cost per kilometer of Rs. 6.51. In contrast, under the previous electricity tariff of Rs. 71 for EV charging, an equivalent e-bike’s total ownership cost was significantly lower at Rs. 4.15 per kilometer. The economics become even more attractive under the government’s revised tariff structure of Rs. 39.7, bringing the five-year ownership cost down to Rs. 3.52 per kilometer.

However, significant challenges persist. Despite favorable long-term economics, the escalated upfront cost of EVs remains beyond the affordability of most Pakistani households. The financing landscape compounds this problem, with local banks maintaining a risk-averse stance toward consumer financing. From a supply-side perspective, EVs are capital-intensive ventures requiring substantial funding that exceeds traditional technology businesses. While local venture capital can support early-stage startups, their ability to participate in larger, subsequent funding rounds is limited, leading to investor fatigue.

Infrastructure development presents another crucial challenge. Establishing battery charging and swapping stations is essential for the EV ecosystem. To execute this effectively, key parts of EVs, including batteries, need to be commoditized so that infrastructure can cater to all consumers utilizing the technology and benefit from economies of scale. Smart batteries with trackers offer one solution, potentially mitigating banks’ fears about loan defaults by allowing non-payment to be penalized through vehicle disconnection. The infrastructure could also leverage surplus capacity in Pakistan’s electricity grid, potentially reducing national tariffs. Current estimates suggest EV charging

integration could enhance grid demand between 1.5-2 GWh.

To understand the economic viability of charging infrastructure, we modeled a typical EV charging station equipped with 12 batteries serving 40 customers daily. The model assumes initial setup costs of Rs. 800,000, battery investment of Rs. 1,380,000, monthly rent of Rs. 80,000, and maintenance costs at 2% of revenue. With a per-charge fee of Rs. 275, under the previous electricity tariff of Rs. 71, the station’s payback period would be around 15 months. The government’s new reduced tariff of Rs. 39.7 improves these economics significantly, bringing the payback period to just under a year. However, these promising returns hinge critically on consistent utilization - if daily battery swaps drop to 15, the payback period stretches to three years, highlighting the classic chicken-and-egg problem facing infrastructure development.

The industry is, however, finding innovative solutions to these challenges. Retrofitting existing ICE models with EV kits, costing around Rs. 45,000 without battery, offers an attractive alternative path to electrification. This approach appears particularly promising given the 30 million bikes already on Pakistani roads. The government supports this initiative, planning to convert one million two-wheelers to electric bikes at an estimated net cost of Rs. 40,000 per bike.

Looking ahead, while challenges persist – including potential IMF resistance to sector subsidies and protection – the trajectory appears promising. The combination of smart policy measures, improving economics, and innovative solutions like retrofitting suggests that Pakistan’s electric two-wheeler revolution is not just possible but increasingly probable. As the industry expands and localization increases, it could serve as a catalyst for broader electric mobility adoption, contributing significantly to both environmental sustainability and economic development. n

Back in the 1960s, Batala Engineering was a shining beacon of what a Pakistani company could be. Today, it is trying to recover from decades of mismanagement and misuse

By Zain Naeem

In 1964, the then prime minister of China, Chou-en Lai, visited Badami Bagh to see the factory of Batala Engineering Company. What he saw impressed him so much that he wanted to send Chinese Engineers to get trained from the industrial unit. At that point in time, Batala Engineering was producing everything from diesel engines to aircraft parts which were being used locally and were being exported abroad.

It employed 6,000 workers including German and Japanese engineers, and was considered a national asset. But those glory days are long gone. Batala faced the wrong end of a nationalisation, and a disastrous effort to bring it under state control followed by a relentless tussle at the top has made the company a shadow of its old self. Within a span of 60 years, the company has virtually shut down. The fall from

its peak is nothing short of shocking and spectacular. Recently, a right share issue has been announced in order to raise funds to finance its working capital needs. This is a story of how a company fell from grace and is looking to revive its past as it once was.

When Batala Engineering Company was being established in 1932, it was supposed to be a symbol of identity and unity for the Muslims of India. Inside the Islamia School of the village, a group of Muslims joined together to work for the betterment of their Muslim brethren who had little to no representation in the country. Chaudhry Mohammad Latif gave credence to the idea that a wholesale business could be started which

would be a point of pride for the downtrodden. With the company coming into existence, it started manufacturing chaff cutters in 1934 and thus began the lore which has survived till today.

In a short period of 10 years, the company set up its own foundry and machine shop which enabled them to manufacture their own agricultural implements. In order to meet the capital needs of the company, a partnership was created between Daulat Ram and Latif which enabled it to grow further.

With the breaking out of the Second World War, the government gave out leases which allowed Batala Engineering to keep growing. A branch office was opened in Lahore which expanded its footprint beyond its birth city. As the partition was announced in 1947, the company was in the process of importing new machinery to its factory. Once the partition was finalized, the destination of the equipment was changed and the plant was moved to

Badami Bagh, Lahore. Agreements made after the partition meant that factory space was allotted on the Pakistani side in exchange for the property that was owned in Batala. The shareholders and directors moved to Lahore while the assets that were still installed at the old factory had to be left behind.

The story of the company after 1947 started from scratch again as Batala Engineering was able to take over the defunct factory of Mukand Iron & Steel Works Limited. As the factory had been left abandoned, reconditioning was required to make the factory operational. Around 120 machines had been imported from Germany which were now installed into their new home. A company started by 100 Muslims investors only 15 years ago had grown into a behemoth by now. Batala Engineering now supported eight departments ranging from steel works, foundry, rolling mills, iron foundry, machine shop, structural shop and general engineering shop. Even after facing a shock like the partition, the management was able to bring the company back onto its feet in a period of 3 years only. Testament to the success was the fact that the company was listed on the stock exchange in 1955.

Considering the success that was being seen, it would have been no surprise to see new milestones being achieved over time. This could not happen sadly. With the oath taking ceremony of Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto, the corporate houses of the country were nationalized with the stroke of a pen. In 1972, the Nationalization and Economic Reforms Order was promulgated which all but wiped out Batala Engineering from existence. Due to the nationalization, the first thing done was to change the name

of the company to Pakistan Engineering Company (PECO). Not only was the name changed but as the management was handed over to the government, the profitability also became a thing of the past. From 1972 to 1988, the company racked up accumulated losses of Rs 76 crores.

During his tenure, Zia-ul-Haq offered to give back control to Latif as a way to get rid of the company but he fell victim to a plane crash before the deal could go through. When the new government of Pakistan People’s Party came into power, the best course of action suggested was to sell the assets through an open bidding process to get the highest possible price.

In 1995, the privatization commission took a proactive approach to get rid of these loss making entities and tried to carry out some belt tightening by closing down its Badami Bagh plant. When this did not work, they started to strip the profitable assets like the steel that was used in the building infrastructure. When all of this did not work, a public offer was made to sell the company once and for all. What was started nearly 60 years ago was now seeing its fate being decided by bureaucrats and politicians and was near to breathing its last. The only ray of hope was that Latif did not just sit back and let fate be decided by the red tape vultures. Seeing that it was being sold, Latif filed a case in the Lahore High Court against privatization being carried out. Seeing the efforts of Latif, the government decided to negotiate with him and ownership was slowly sold to the private sector.

The disastrous nationalization of the company had left indelible scars on the existence of the company which have lasted till today. PECO had lost its position at the top of the perch but private investors showed that the company was still viable and could be turned around.

As the shareholding was transferred from the government to the private sector, it seemed that the worst was still to come. When the nationalization was being carried out, around a quarter of the shareholding was held by Latif. After the nationalization, these shares were transferred to State Engineering Corporation which was under the purview of the Ministry of Industries. In addition to this, the government owned mutual fund, National Investment Trust (NIT), also ended up purchasing 21% of the shares from the stock exchange. The government held 54.5% of the shares directly or indirectly while the remaining 45.5% were held by the general public.

It has to be understood here that NIT is a mutual fund which is managed by the government, however, its fiduciary duty is to act for the benefit of its shareholders who have invested in the fund. This means that in case the trust has to decide between benefitting the government or the investors, it will end up erring on the side of its unitholders. In pursuit of the privatization, NIT was ordered by the Privatization Commission not to sell their shares prior to any approval from the Commission but the authority of the commission to do so was ambiguous to say the least.

While the ambiguity of the status of these shares existed, the company was selling off some of its vital assets in order to raise funds to pay back the government. As the losses started to accumulate, bail out packages had been given to keep the company afloat. In 2003, the board of directors were given the go ahead to sell the valuable assets to pay off its liabilities. In conjunction with this approval, NIT started to sell its own shares in PECO which amounted to around 12 lacs in quantity.

As the quantity was large, eyebrows were raised in the stock exchange as it was felt that improper trading practices had been carried out. An investigation carried out later in 2018 alleged that NIT sold shares to a company which was used as a front by Arif Habib who bought the shares through Rotocast Engineering. These allegations were denied outright by Arif Habib.

The impact of this sale was that the government ended up owning less than a third of PECO where it had more than 50% control before. The aftershocks were still being felt when the election for the board of directors was carried out in 2006 which saw the government lose three seats in the board and go into a minority. It used to have six out of the nine seats which became three after the elections were held.

The positive aspect of the change in control saw the company see its revenues go from Rs 24 crores in 1999 to Rs 1.7 billion in 2010. Profits also increased seeing a peak at Rs 31 crores in 2007. As far back as 2004, the company was making a loss which finally turned into a profit in 2005. Revenues of Rs 85 crores were earned in 2005 leading to profit of Rs 9 crores. Over time, these figures kept improving, seeing a peak in 2010 with the company earning revenues of Rs 1.7 billion. After a slump of 5 years, results rebounded in 2016 as the company ended up making revenues of Rs 2.3 billion and profits of Rs 22 crores were earned.

This was the last year before revenues of the company started to plummet and profits turned into losses on a consistent basis. As the results of the privatization were the ones that were expected and required, no investigation was carried out into the alleged sale of the shares during Musharaff’s era. This changed when the matter was raised in the Public Accounts Committee (PAC) which became functional under the democratic government. The committee alleged that insider trading had been carried out and asked the government to regain the controlling shares in PECO. Based on the alleged wrongdoing, Arif Habib showed that he was willing to let the government appoint the new Chief Executive Officer (CEO) at the company while maintaining the status quo in the board and ownership of the company.

This planted the seeds for the problem that would end up wreaking havoc at the company in later years. In 2016, the government appointed Mairah Anees Ariff as the new CEO at PECO. The shareholders and board members started to accuse Ariff of embezzlement and corruption in order to benefit himself at the expense of the company. On the other hand, the manner in which the private sector had acquired the shares was also dragged out as in response to these allegations. The conflict was

over the fact that the private shareholders considered Ariff to be incompetent and unqualified for the job of turning around the fortunes of the company. Ariff felt that a mutiny was being orchestrated against him by the private shareholders.

Things came to a head in 2018 when Ariff made a complaint to the National Accountability Bureau (NAB) against three of the senior officials at the company. He fired the officials and barred their entry into the offices. One of the officials named was the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) at the company. The private shareholders alleged that Ariff was lashing out at the people who were highlighting the wrong doings of the CEO. The CFO was not signing off on the accounts of the company as they hid the losses that were being made during the tenure of the CEO. As the mudslinging between the two parties went from bad to worse, the company saw its accounts frozen, the CFO fired and the authorized signatories being changed without the approval of the board of directors. There were even cases where the CEO barred board of directors from attending board meetings at the company premises as well. The whole ordeal ended when the government removed Ariff from his position based on a vote carried out by the board of directors. This scuffle at the top proved to be the last nail in the coffin as the company suffered financially and made losses.

After the failed experiment of nationalization and the scuffle between the board and the CEO, it seems that things are starting to come back to normal. The board has started the process by filing all the pending accounts of the company going back to 2019 when they had ceased to be submitted to the relevant authorities. The lat-

est development in this regard is to raise Rs 28 crores through a right share issue. The purpose of this is to meet the funding requirements of the company which have arisen due to the alleged mismanagement of its former CEO. In a recent press statement, the company has notified the exchange that the pending accounts have been approved by the board which will be presented at the Annual General Meeting to be held on the 17th of February 2025. Due to mismanagement and neglect of its former CEO, the board feels that a huge amount of damage has been caused which needs to be reversed. The board is working towards approving the accounts to increase transparency and revival of the company going forward. The board estimates that alleged losses of Rs 1.2 billion were caused by the mismanagement of the company. These losses have put the future in jeopardy as the suppliers and financial institutions have filed for the company to be declared insolvent. The assets of the plants also saw deterioration while the trade receivables were used to fund losses. This led to a complete shutdown of operations leading to much of the workforce being fired.

The removal of Ariff was formalized in 2022 when Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif stepped in by restoring the old board. As soon as the old board was brought back, they set about righting many of the wrongs at the company to reconstruct the financial records and to bring its operations back on track. One way of doing so is to offer right shares to the current shareholders to increase their investment. For every 2 shares held, one right share is being given which will require subscription of Rs 100. With the shares trading at Rs 750, the right shares are considered a bargain. The funds raised will be used to pay off liabilities to rebuild its reputation with the creditors while also raising working capital which will be used in the day to day operations. Will this be the catalyst for change? Only time will tell. n

The commoditization of matchmaking is not a novel concept but it might be finally on its way to be a formal business sector

By Nisma Riaz

In a dainty cafe in Lahore, 30 young singles have awkward first conversations punctuated by forced but polite smiles over brunch, waiting to receive a confidential envelope that will reveal a name. While in a lavishly decorated hall in Islamabad, 200 young professionals mingle over painting workshops and carefully curated icebreaker games. These are not your typical social gatherings but one of the many matchmaking events that have become increasingly popular in Pakistan’s urban centers. The scene is a far cry from the traditional drawing room meetings where families size each other up over tea and samosas, while a rishta aunty mediates the awkward conversation.

The matchmaking industry in Pakistan

may be undergoing a transformation. While the traditional rishta aunty business continues to thrive, with some charging up to Rs 10 lakhs for elite and overseas matches, a new breed of entrepreneurs is disrupting the market by combining technology, pseudo-science and the commitment to find a partner. This hybrid approach is proving particularly effective in urban areas, where young professionals are seeking more agency in their choice of life partner, while circumventing the mortifying rishta process.

Like much of Pakistan’s wedding industry, the matchmaking business operates in a gray zone between formal commerce and social networking. The industry largely runs on informal arrangements, with minimal documentation or regulation and this unique nature, blending personal connections with financial

transactions, makes it particularly challenging to analyse through a purely business lens. Until now.

As the sector continues to evolve, Pakistan may soon see the emergence of entrepreneur matchmakers who achieve the same professional status as the country’s renowned wedding planners, photographers and bridal wear designers. With an interplay of psychology, tech, and the age-old need to find a partner, matchmaking is set to be completely transformed.

The numbers tell a compelling story. According to the Pakistan Demographic and Health Survey 2017-18, approximately 1.6 million weddings

occurred in 2021, accounting for population growth. This represents an enormous market opportunity for innovative matchmaking services. While India’s online matchmaking industry was valued at $200 million in 2017, Pakistan’s market remains largely fragmented and ripe for disruption.

The Pakistani online dating market presents a snapshot of digital romance in South Asia, according to the December 2022 Statista report. The report projected the number of users on matchmaking apps in 2024 to be a staggering 1.4 million, while for online dating apps it was 2.2 million.

The landscape is notably male-dominated, with more than three-quarters of users being men, creating a significant gender imbalance that shapes the entire ecosystem. The user base skews remarkably young, with all users falling between 18 and 49 years old, and nearly two-thirds being under 30.

According to the same report, this digital dating population is predominantly urban and well-educated, with a strong representation from higher-income households. Dating app users are more likely to live in cities and urban areas compared to the general online population, with a particular concentration in large cities and megacities. Their affluence is notable, with nearly half coming from high-income households, significantly higher than the general internet-using population.

The lifestyle patterns of Pakistani dating app users reveal a digitally-savvy demographic. They show strong interests in finance, economy, and entertainment, while maintaining active social lives both online and offline. Social media engagement among dating app users is also particularly strong. The vast majority actively participate in social platforms, with activities ranging from posting personal content to engaging with brands. Interestingly, despite their digital fluency, more than half of these users express a preference for services that offer personal contact, suggesting a desire for authentic connections beyond purely digital interactions.

The market structure presents both challenges and opportunities. The significant gender imbalance highlights the untapped potential for increasing female participation. The high education and income levels of current users point to possibilities for premium services and subscriptions, while their strong digital engagement patterns offer clear pathways for marketing and user acquisition for dating apps.

But why does this market, that is already seeming thriving on online matchmaking platforms, need matchmaking events?

Well, looking at the broader implications, this market appears to be at an interesting crossroads. The young, educated, and

digitally-savvy user base suggests strong potential for growth, however their preference for personal contact in these services indicates that successful platforms might need to bridge the digital-physical divide.

The Pakistani online dating market therefore emerges as a complex ecosystem where traditional values meet digital innovation. It’s a market characterised by sophisticated users who embrace technology, while maintaining connections to traditional media and values. This unique combination suggests that success in this market requires carefully balanced approaches that respect local cultural nuances, while leveraging digital capabilities. The future of online dating in Pakistan likely lies in services that can effectively bridge these different aspects, creating experiences that resonate with users’ desire for both digital convenience and authentic personal connections.

“When you move abroad or even when you’re in your own city and your own country, you want to connect with a person who matches your vibe, not just someone who looks good on face value based on their rishta profile,” explains Nayab Nazir, Marketing Lead at Muzz Pakistan. This sentiment reflects a growing demand for matchmaking services that cater to educated, urban professionals who find traditional methods increasingly misaligned with their values and lifestyle.

From rishta aunties, to Facebook matchmaking groups to dating apps, Pakistani singles have exhausted all avenues to find a partner and settle down. As soon as you turn 25, or 20 in some cases, the shadi pressure is donned upon you. The traditional rishta hunting process that many young desis have to go through has been criticised for being superficial, oftentimes deemed humiliating and damaging for self esteem, and even coercive in some cases. Not to forget the awkwardness of families being involved from the get go, which makes it impersonal.

Then came the online rishta groups, where people post rishta profiles of themselves or friends, in order to find a suitable match. Again, making and posting a rishta profile can be daunting and putting yourself out there, setting you up for public scrutiny is not for the faint of heart.

Then there were, well still are, dating and matchmaking apps. Despite being a more futuristic approach to finding a match, without having to involve one’s family or having any expectations attached, this model is not free of flaws. From security concerns to catfishing and a lack of proper regulations, these apps can be scary. Moreover, a general

conception of matchmaking apps turning into hookup apps has greatly harmed the credibility of dating apps.

And finally, thanks to matchmaking events, after going from in person to online and now back to face to face meetings, we have come full circle. These quickly popularised matchmaking events are organised by others, taking away the pressure to host and providing a safe environment to mingle, are becoming the perfect new avenue for young singles to find a partner.

Noor ul Ain Choudhary (Annie), founder and host of Annie’s Matchbox Party, is one of the first ones to introduce matchmaking events in Pakistan. And she has a science backed twist.

Annie uses an American platform called Matchbox, used for curating and hosting matching parties. She uses the basic subscription model that charges a fee of $4 per guest. This platform comes with an algorithm that matches young professionals based on the responses they provide to an online compatibility quiz that assesses participants’ preferences. The platform also offers other subscriptions, including Premium which costs $95 and a $4 fee for every guest, as well as an Elite subscription which costs $95 and a $8 fee for every guest. With premium and elite subscriptions, hosts get a commercial license to ticket guests, get insights on why the algorithm made the matches it did and even incorporate preferences and deal breakers of guests.

In conversation with Profit, Annie explained how the Matchbox algorithm works, “It’s a software that’s developed by behaviour and relationship scientists designed for college students to find their most compatible match according to relationship science and their values.”

When asked how and why she decided to host her Matchbox events, she shared, “As a young woman myself I knew the two polar opposite systemic options we had when it came to finding “the one”. It was either the rishta system where everything other than individual compatibility is prioritised. And on the other hand we had dating apps that are an exhausting investment of time and effort with no guarantee of safety.”

“I think I saw a problem and I saw something that could be a solution and they came together in my head. I’m always looking at things that intrigue me and observing them closely. I had been watching this software evolve in the states,” she continued.

Having worked for an event production house, Choudhary claims to have picked up on enough knowledge to have an idea of what it takes to execute a successful event. “All these ingredients came together for me.”

So, how exactly does it work?

Well, you sign up for the event, which is predominantly marketed on social media platforms. Once the application is received, you go through a screening process, mainly based on your social media presence and anything about you that can be easily found on the internet. When there are no obvious red flags, you make the cut. Choudhary caps the number of participants at 30 people, however the sample may increase as her events scale.

Choundhary explained, “My earlier events used to be capped at 30 people and that was because I was doing everything alone and I only wanted to take on what I could handle.”

A few days prior to the event, you receive the Matchbox questionnaire, which once filled in is fed into the algorithm. The algorithm then works its magic and pairs you up with your closest most compatible match. At the event, you mingle with other participants, talk over food and refreshments until you are handed a red envelope with the name of your closest match in it. Once you have found the person the algorithm matched you with, you can talk to them and leave the event feeling either satisfied or seriously disappointed.

What we observed at Annie’s Matchbox Party in Karachi, which she hosted in collaboration with Neutral, was that the sample size was quite small and the chances of everyone participating to find a match they liked were by proxy slim.

“People have formed great, not just romantic but also platonic and career oriented, connections even from these small pools and while my pools are getting bigger I feel like smaller pools are less intimidating for guests. Maybe in the future when I have a bigger team we might have a 100 person event,” Choudary noted.

Choudhary hosts these events at coffee shops or small restaurants so she doesn’t have to worry about the décor or creating a menu. She usually has a curated menu of selected items from the pre existing menus.

After having hosted seven to eight events, Choudhary says that the success rate is around 20%-30%. “It could be higher but this figure comes from people who keep me updated after the event.”

The cover charge is where things get interesting.

To sign up for Annie’s Matchbox Party, women pay a cover charge of Rs 5500, while men pay Rs 6600.

When asked why men pay slightly more than women, Choudhary explained that in the current social climate and safety concerns, matchmaking services often implement tiered pricing structures that reflect the additional due diligence required for male clients.

This includes comprehensive background screening processes and extra verification steps to ensure the authenticity of marital status and other credentials. The higher fees for

male participants help cover the costs of these enhanced security measures, which are essential for creating and maintaining safe spaces in Pakistan’s evolving matchmaking landscape. Such precautions have become an integral part of modern matchmaking operations, reflecting broader societal concerns about women’s safety in romantic relationships.

However, global trends also show that men tend to spend more money, when it comes to finding a match and courting a potential partner.

The dynamics of Tinder’s user base supports this pattern. In 2022, the app boasted a massive user base of 71.1 million, though only 8 million users chose to pay for premium features. This conversion rate becomes even more intriguing when examining the gender split. An overwhelming 96% of paid subscribers were men, with women making up just 4% of premium users. These numbers paint a picture of a platform that, while free to use at its core, has successfully created a premium ecosystem primarily driven by male users willing to pay for additional features.

While the success rate of Annie’s parties is quite low, it could be due to a very small sample size, as well as Pakistani cultural scripts and values not being accounted for in the American software she uses. Despite being unhappy with their matches, some participants claimed to have met people who they intended to keep in touch, as just friends, of course.

One male participant, who wishes to stay anonymous said, “The algorithm is useless, it knows nothing! But the party was nice.”

Another female participant said that the event has potential and she might consider going to another similar event in the future.

Another issue we observed at Annie’s matchmaking event in Karachi was the demographic, age in particular. In the participant pool, most women were closer to or older than 30, while most men were in their mid twenties. The algorithm did not account for age gap preferences, due to which many guests left unsatisfied with who they were paired with at the end of the party.

However, Annie’s Party is not the only matchmaking event hosted in Pakistan. The matchmaking online platform Muzz that operates in more than 190 countries and hosts a total user base of 12 million single Muslims, also hosts events of their own.

The traditional rishta aunty business model is well-established, with various pricing tiers based on socioeconomic status and location. In an earlier conversation with Profit, back in 2021, Mrs. Siddiqui, a prominent matchmaker, said she charges Rs. 50,000 for local matches, es-

calating to Rs. 150,000 for prospects in North America and Europe. Another rishta aunty Mrs Rahim said has a flat registration fee of Rs 5000 and charges Rs 75,000 from both families once the rishta is done. However, in her case, she also makes it a point to visit the families, assess their living situation and lifestyle before finding matches for them.

While this model has proven lucrative, it lacks scalability and often feels transactional to younger generations.

Enter the new hybrid model. Companies like Muzz have introduced a multi-tiered approach that combines digital platforms with physical events. Their basic digital platform is free, while premium features such as enhanced visibility and advanced filters come at a subscription fee. You can pay Rs 720 for a weekly subscription, while one month and two month subscriptions cost Rs 2000 and Rs 2400, respectively. Muzz refused to share the estimated number of paid subscribers due to confidentiality reasons.

The events business operates as a complementary service, with ticket prices ranging from Rs 2500 to Rs 5000 per person. The cost of events varies based on the city and venue. In Lahore, a paint workshop and matchmaking event by Muzz cost Rs. 5500 per person, while another event was Rs. 2500.

Profit spoke to Nayab Nazir, marketing lead at Muzz Pakistan, to understand why Muzz feels the need to host in person events when the app already exists.

She revealed that these physical events have been introduced to address some reservations and key limitations that people face on online platforms and with the traditional rishta process. “The digital platform provides the initial screening and matching, while events offer the crucial face-to-face interaction needed to move relationships forward. This combination addresses a fundamental limitation of both traditional matchmakers and matchmaking apps,” Nazir explained.

Women often don’t feel safe meeting men they have met on the internet in person but it is also necessary to have face to face interactions with someone you are considering as a potential partner. On the other hand, when they meet men through the rishta process, their families are also present, limiting candid conversation.

Second, events facilitate organic interactions through activities like painting workshops and group games, avoiding the awkwardness of traditional rishta meetings. This approach has proven particularly successful among urban professionals who find the traditional drawing room setup stifling.

The real innovation lies in how modern matchmaking companies use technology and events to complement each other.

Nazir explained the process and struc-

ture of Muzz’s in-person matchmaking events.

She shared that since early 2024, Muzz has organized several successful matchmaking events in both Lahore and Islamabad, with attendance ranging from 100 to 200 participants. A unique feature of these gatherings is that every attendee gets the opportunity to interact with all other participants.

“The events are structured to facilitate natural interactions through various activities, including games and painting workshops. We incorporate multiple engagement formats, including speed dating sessions. To help break the ice, we use interactive games like bingo where participants share information about themselves and engage in Q&A with others. We provide participants with cards featuring conversation starters, similar to those found on the Muzz app, which combine casual yet relevant questions to help foster meaningful conversations,” Nazir shared.

She highlighted that this approach helps create a relaxed atmosphere where people can connect more authentically, moving away from the potentially awkward dynamic of direct matchmaking conversations.

She added, “The goal is to create an environment where people can naturally discover connections and potentially continue their interactions after the event, rather than forcing formal matchmaking conversations. This structured yet informal approach has proven successful across their events in both cities.”

According to Nazir Muzz events have shown promising results, with multiple couples moving forward to involve their families after initial meetings.

“Our success can be measured in several ways. First, through our ticket sales, our events are so popular that they typically sell out within weeks of being announced, demonstrating high demand. We sell tickets both through our app and on-site,” Nazir shared.

She added, “After each event, all participants receive a list of attendees through our app, which helps foster community connections. We’ve seen particularly encouraging feedback through our marketing email channels, with multiple families getting involved. Specifically, two to three families from Lahore and two families from Islamabad have reported participating together, showing how our events are bringing families closer and expanding our reach across different cities.” This combination of quick ticket sales and growing family participation serves as a strong indicator of the event’s success.

Research shows that success rates are notably higher when digital matching is combined with events. While traditional matchmakers claim success rates as high as 65%, many acknowledge significant challenges in tracking outcomes. The hybrid model offers better met-

rics through digital tracking combined with event attendance and follow-up data.

It is common knowledge that the wedding industry of Pakistan is a lucrative sector. Based on the number of marriages in the country and the average amount spent on each wedding, Pakistan’s wedding industry is estimated to be worth over Rs 110 billion annually.

But does the matchmaking business, which precedes weddings, has the potential to be as lucrative, if formalised as an authentic business sector?

Well, to answer briefly; not yet. However, considering that people are willing to pay north of a million rupees to rishta aunties, if formalised, the sector has potential to grow and become one that generates high revenues.

Annie’s Matchbox party is a profitable event according to Annie. Although, it may not render insanely high profits.

According to Profit’s estimations, the overall cost of the Matchbox software was around Rs 40,000 to Rs 50,000, while the rest of the expenses including food and decor was between Rs 80,000 to Rs 1 lakh. The total expenditure rounds up to Rs 1.3 lakhs. Based on the number of attendees, the revenue generated amounts to Rs 2.3 lakhs.

The profit made on this event was around Rs 1 lakh. The Matchbox party hosted in Karachi was done in collaboration with Neutral on a 40% profit sharing model, so the host made approximately Rs 60,000 only.

But as we said earlier, the business has potential to earn much higher profits if the scale and volume of these matchmaking events is increased.

On the other hand, Nazir says that the purpose of Muzz matchmaking events is not to earn profits. “Our goal is not to generate profit but to facilitate in-person connections, complementing conversations already happening in the app. These events help people meet, interact, and sometimes even disagree.”

For Muzz, the events serve as a way to give back to the community, while the app remains the main revenue generator. Nazir highlighted that even though it is not a profit-led venture, Muzz easily breaks even.

An interesting byproduct of matchmaking events has been community building and fostering recreational avenues. Participants often form

friendships and professional networks, even when romantic matches don’t materialise. This additional value proposition builds long-term customer loyalty.

“Our events foster new friendships and meaningful connections. In Lahore, a group of girls met, bonded, and exchanged numbers. Similarly, our moms’ event brings together mothers of single sons and daughters, recognising the cultural significance of family compatibility in Pakistani marriages,” Nazir noted.

Understanding family dynamics is crucial, as marriage often extends beyond two individuals to their families. “That’s why we host targeted gatherings, including future events for singles, moms, and even dads. Our community-based events also encourage diverse social interactions, introducing new cultures, castes, and professions into families,” Nazir concluded.

This community aspect is particularly valuable in Pakistan’s urban centers, where opportunities for social interaction can be limited.

The matchmaking industry in Pakistan stands at a crossroads. While traditional rishta aunties continue to serve their market, there is a growing population that discredits this model and prefers organic connections.