10 The state of higher education in Pakistan

16 Pakistan’s first digital bank is here

22 Commercial cards could be the trick to unlocking Pakistan’s SME potential

23 Logistics industry facing $36 billion losses due to offline trade

24 HBL and S&P launch Pakistan’s first Purchasing Managers’ Index

25 Big tobacco’s taxation concerns are as alive as ever

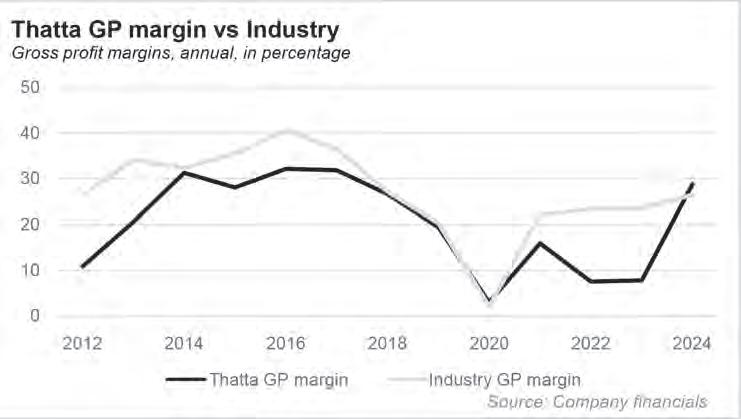

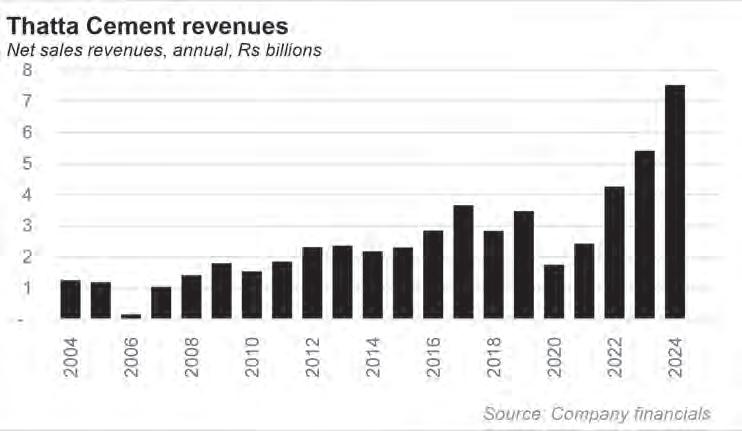

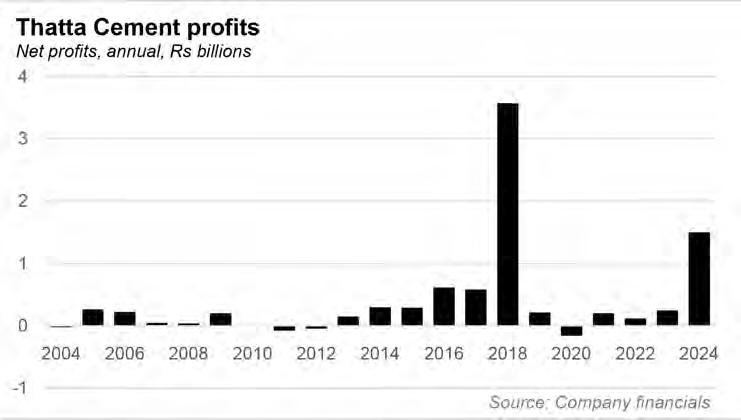

27 Thatta Cement recorded stellar profits for 2024. The reasons behind it are simple yet effective

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz Khan - Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Editorial Consultant: Ahtasam Ahmad - Business Reporters: Taimoor Hassan | Shahab Omer

Zain Naeem | Saneela Jawad | Nisma Riaz | Mariam Umar | Shahnawaz Ali | Ghulam Abbass

Ahmad Ahmadani | Aziz Buneri - Sub-Editor: Saddam Hussain - Video Producer: Talha Farooqi

Director Marketing : Mudassir Alam - Regional Heads of Marketing: Agha Anwer (Khi) Kamal Rizvi (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) - Manager Subscriptions: Irfan Farooq

Pakistan’s #1 business magazine - your go-to source for business, economic and financial news. Contact us: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

By Farooq Tirmizi

The college-educated Pakistani is not yet the majority, but is rapidly becoming part of the norm.

More than half a million Pakistanis graduate from a college or university every year with at least a two-year college degree. A little more than 11% of 30-year-olds in Pakistan have at least a two-year college degree and, judging by the fact that the number of graduates is growing at three times the population growth rate, that number will likely keep on rising for every subsequent generation of 30-year-olds in the country.

So what do those statistics mean? It is by now cliché to assume that the quality of higher education in Pakistan is (partly true) and that while the country has a lot of raw talent, the country is not prepared for the rapid advancement of technology that will necessitate a much better trained workforce than the one we have now.

There is no denying the fact that education – both in terms of quality and quantity – is lacking in Pakistan. It is the contention of this publication, expressed through previous analytical writings, however, that the situation can be described as not ideal, but far from hopeless.

While in previous articles we have covered basic literacy and numeracy, in this piece will cover higher education, placing it in both historical context relative to where it has been in Pakistan’s own past, as well as the global context: where Pakistan stands relative to peer economies and geographic neighbours.

We will then examine a question often left unasked: exactly how well-educated does the median Pakistani need to be, given where the country is in its economic evolution? And how has the answer to that question changed with the advent of the recent, more visible, rapid advances in artificial intelligence (AI)?

As with all our stories, we will provide you the conclusion of our analysis up front.

1. Every successive Pakistani generation is significantly more educated than its predecessors, and the pace of improvement itself is accelerating.

2. The level of higher education attainment, while behind that of the kind of economies Pakistan aspires to be, is in line with the kind of economy the country currently has at the moment and needs.

3. The pace of increase in higher education attainment is fast enough to ensure that, by the time Pakistan’s economy needs a large college educated workforce, it will have one.

4. The advent of artificial intelligence changes the nature of work, and the expectations of what is possible to be done by a single human, but does not preclude the need for the kind of workforce Pakistan has.

The one-sentence summary for this remains the same as it was for our previous article on basic literacy and numeracy: higher education in Paki-

stan is not good, but it probably is – and probably will be – good enough for what we need.

Where we currently stand

About 8.6% of Pakistanis over the age of 25 have at least a bachelors degree or higher, according to data from the World Bank for the year 2021, the latest year for which comparable data was available. But as we stated at the outset, that number hides the fact that younger Pakistanis are going to college at higher rates than their parents and grandparents, and that this increase in rate is itself increasing.

During the year 2020, about 11.2% of 25-yearolds in Pakistan had a college degree or higher, and 30-year-olds that year had a college attainment level that was even slightly higher, according to Profit’s analysis of data from the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics, specifically the Pakistan Social and Living Standards Measurement Survey (PSLM), the latest of which was the one for the year 2020. That number is itself rising rather rapidly. The number of people in Pakistan who successfully finished a college degree in the academic year ending in 2022 was about 502,000 students, according to data from the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan. That number represents an average annual growth rate of 7.3% per year over the five years between 2017 and 2022. To put that growth in context, it is more than three times higher than the 2.1% per year population growth rate during that same period.

In other words, it is highly likely that the trend of every successive generation of Pakistanis being better educated than the previous one is not only continuing, but accelerating.

One way to place this rise of higher education in Pakistan is with the following statement: almost the same percentage of Pakistanis is college-educated today as was literate at Partition in 1947. The progress may be slow, but the direction is unmistakable.

Is it good enough?

It is all well and good to say that Pakistan is doing better than its own atrocious past. How well is the country doing relative to the rest of the world? And, most importantly, is Pakistan doing well enough for its own economic needs?

For that, let us compare Pakistan’s best number – its youth higher education attainment level – to that of other countries. Against Pakistan’s 11.2% number, Brazil’s young adult population has a college graduation rate of 15%, and Indonesia has a rate of 16%, according to data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD). While a comparable number for India was not readily available, about 13.2% of Indians over the age of 25 have a college degree, compared to just 8.6% of Pakistanis.

We are behind just about any economy we

would want to compare ourselves to in terms of either total size or even per capita income.

College graduation rates, in short, are not good in Pakistan.

But are they good enough? The country has only just started a serious run at industrialization with most industry in the country being lower end manufacturing and assembly. No country goes from farming cotton one day to manufacturing semi-conductors the next day. There are several layers that go in between, and while the process does not have a strict sequence, it does tend to be gradual.

So the answer to whether or not what Pakistan has achieved in higher education today is good enough depends on what one believes Pakistan needs. If your perspective is that Pakistan should be doing as well as countries that are clearly ahead of us in economic development, then any metric you look at will disappoint you or provide proof of your pessimism.

If, however, you adopt the more mature approach of “where is Pakistan today, and does it have what it needs to be move ahead from that point at a reasonably pace?’, then you are likely to find that Pakistan has a sufficient number of college graduates to meet its own needs at this stage of its economic development and continue to improve further.

Given the relatively light levels of industrialization, Pakistan barely needs more than it currently has in terms of a white collar workforce with college degrees. Indeed, Pakistan can probably afford to export some of its talent as it has been doing for the past four decades, given how much of it we produce relative to how much we need.

What is our proof that Pakistan has a surplus of educated young people? If it did not, salaries would be growing faster. They are not, which means employers have no trouble finding enough people to fill all jobs that require a college degree, and it is so easy for them that they do not need to offer very high wages to do so.

Over the next 25 years, however, one hopes that Pakistan will move further up the

value chain, and start doing more complex manufacturing and services. But given how rapidly Pakistan’s higher education sector has been growing, if the current rate of growth is extrapolated into the future, it would imply that the proportion of young Pakistanis with college degrees would rise to about 56% by 2050. For context, the United States has a college graduation rate of 46% among its adults between the ages of 25 and 34, its more educated cohort.

The equivalent number in China is 27%, which is probably a more realistic target for Pakistan to hit over the next quarter century. To hit that number by 2050, the increase in annual number of college graduates in Pakistan could slow down from its current 7.3% per year growth rate to 4.6% per year growth and we would still hit the college graduation rate that China has today.

Our current baseline may be bad, but it covers our current needs, and the pace of growth is so rapid, it is likely to more than meet the needs of a fully industrialized economy within the next 25 years, even if the current rate of growth slows down somewhat, which it most likely will.

How will AI change the need for higher education?

The emerging consensus among Pakistanis who talk about artificial intelligence is that the technology is likely to be bad for the country’s nascent IT-enabled services export industry, both for freelancers as well as companies. And as AI becomes a more widely used technology, Pakistan’s low quality human capital will find itself at a disadvantage in the global talent marketplace.

The problem with this view is that it imagines the technology as it currently is, and not as it is likely to transform the economy.

To understand how AI will transform

the global economy, it is helpful to think of analogues from the past. AI is what is called a “general purpose technology”, which is to say that it does not have a single application, but in fact many applications. Previous examples of general purpose technologies include electricity, computers, the internet, and mobile telecommunications.

The mistake being made by most people who assume that AI will be bad for economies like Pakistan is to make the following set of assumptions:

1. AI will transform how the world works.

2. The people who work in AI today have far higher levels of intelligence and human capital than all but the tiniest sliver of Pakistan’s current workforce.

3. Therefore, Pakistan’s current workforce cannot survive in the era of AI.

The first two sentences are true. The third sentence, however, is not the most logical conclusion of the first two. Here is the fundamental flaw in this thinking: it assumes that the base layer of AI is how AI will interact with the economy. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Nikola Tesla and Thomas Edison worked on the base layer of a previous generation of a general purpose technology that is electricity. Your neighbourhood electrician does not need to be as intelligent as Thomas Edison or Nikola Tesla.

Take this analogy further. Inventing the base layer of any general purpose technology requires one to be a once-a-generation genius (Tesla, Edison). Inventing the application layer requires one to be a determined tinkerer with above-average intelligence and persistence (Alva Fisher, inventor of the electric washing machine). Operating a business in the application layer once the application has been invented requires average intelligence (the average person who operates a laundry and dry cleaning outlet). Different levels of intelligence required, different levels of money earned. But a place for everybody.

People are looking at ChatGPT, Perplexity, Claude, etc. and assuming that the level of intelligence required to survive in the world of AI is the level required to create those programs. This is like watching Nikola Tesla demonstrate his alternating current light bulb in Manhattan in the 1880s and be convinced that every electrician in the world will need to be like Tesla.

Is AI different? Yes, but also no.

The most common retort to the argument we lay out above is that AI is different from all previous technologies in that it is actively seeking to mimic and eventually replace human intelligence. That there could one day be an economy that did not even rely on most humans.

Let us first get one thing straight: there is no such thing as an economy without humans. AI and robots will never replace human beings. They will, like all previous technologies, augment human beings.

All economic activity involves the transfer of value, most commonly measured through money, and all money in the world is ultimately owned by a human. There can be no economic activity that takes place between non-human entities as the ultimate beneficiaries. It is axiomatically impossible.

It is true, however, that AI does in fact seek to use a machine to replicate human intelligence and thought, which is a fundamental shift in what technology can do. No previous technology has ever had the capacity for self-improvement. AI does. Is that not a gamechanger?

Technologically, yes. Economically, no. Keep in mind the axiom we laid out earlier: economic activity can only take place between two or more human beings. Two Ais interacting to create economic activity are not generating income. Two or more humans are

using AI to generate the economic activity that generates income from that activity. AI will increase the expectations of what a single human being can do, but it will still involve humans making the fundamental decisions that initiate economic activity.

Some jobs will change, others will disappear entirely, and many more will be created afresh. One thing that will never change: the need for humans.

The Pakistani college graduate in the world of AI

Let us make this more concrete and let us start by discussing the part of AI that is most advanced already: the AI that can write software.

It is now possible to do in hours what previously took weeks and months to do in software engineering. I am the non-technical founder of a technology startup. My cofounder and CTO was able to create a clone of the popular messaging app Slack in a matter of a few hours, something that would previously have taken at least several weeks of programming by even the most skilled software developed to build.

If you run a software house in Pakistan that has foreign clients who ask for application development work, or if you are a freelancer who offers this service independently, you are likely to see one of two things happen. Either less business comes through your door as the people who used to use your services as an overflow management system for their own in-house teams are able to do more work inhouse. Or else the people who do still come to you expect you to be able to work much faster, and therefore produce the same applications for much less money.

This is certainly a negative effect, and if one did not change one’s behaviour, all you would see is a reduction in incomes for Paki-

stanis who sell software development services. But the world is a lot more dynamic than that.

First of all, consider the Jevons paradox: the more efficient a production process becomes, the more the demand for that product increases.

Let us get very concrete with this example. Suppose I pay a software house about $5,000 for one week of a full team of work. The typical project I used to ask them for in the pre-AI age took about 6 weeks, so the typical project cost was $30,000. Now, with AI, I know that the six week project can get done in one week, so I give that software house a 1-week deadline, and insist that the project be done for just $5,000.

I saved $25,000 for the development of a software application I needed. Will I just reduce my software development budget by $25,000 and call it a day? No.

I have five additional weeks, and $25,000 that I can spend thinking about all of the other things that I could build applications for that I would previously not have considered because I did not have the time or budget. But now I do.

This process is slow, which is why there is expected to be an initial decrease in revenue for software developers. But eventually, the Jevons paradox will take hold, and demand for software development will not just go back to previous levels, but actually increase. If my total budget was $30,000 and I was able to get just one application from that, once the per-application cost goes down to $5,000, I am not going to be satisfied with just building six applications instead of one.

I am going to be looking everywhere for places where spending $5,000 in one week can solve a major problem that is probably costing me a lot more money than that new custom software layer that I can have built. If spending $5,000 means I need one fewer employee who costs me $60,000 a year, you bet I will be looking for every single opportunity where I can spend that money to save even more.

And here is where AI will, for at least

some applications, increase the attractiveness of a software developer in Sahiwal over one in San Francisco. AI is going to standardize a lot of software development to a higher standard. The San Franscisco developer is, on average, much better than the one in Sahiwal. But now the Sahiwal engineer has an AI that can swiftly comb through all of Github to look for the most relevant and efficient code snippets to put together a software package.

The San Franscisco engineer is still a lot better, but the math has now changed. Suppose the San Francisco engineer makes $200,000 a year and could produce an application one month that would take the $20,000 a year Sahiwal engineer about six months to produce. In other words, it would cost you $16,700 for the San Francisco engineer to give you something in one month what it would cost you $10,000 and six months for the Sahiwal engineer to give you.

But now AI allows the Sahiwal engineer to produce a product that is about 80% as good as that of the San Francisco engineer in the same amount of time: one week for both engineers. Given the fact that the Sahiwal engineer is 90% cheaper, you could literally just give

him twice as much time to do more testing of his product and get it even closer to the San Francisco engineer in quality, and it would still cost you 80% less than the San Francisco engineer.

Of course, this dynamic will not play out in every scenario. But it will play out in at least some of them. And enough to ensure that AI will serve mainly to increase the quality of work produced by our low-human-capital labour force sufficiently that the cost differential works even more in their favour.

In short: one of the most important effects of AI will be that, given the fact that more humans will be expected to use AI in their work, the quality differential between humans will go down, which will work to the advantage of those who live in cheaper locations over those who live in more expensive ones.

A Stanford engineer makes a lot more than a FAST engineer. But if both are using a $20 a month Cursor subscription to help write their code, how much better is the Stanford engineer’s code going to be? The FAST engineer may not make more money per job, but his lower cost of living means he just improved his odds of getting hired.

Conclusion

This same phenomenon will work in slightly different ways in other IT-enabled services. But the fundamental dynamic will apply: AI is seen as producing faster, if somewhat generic quality work but if everyone needs to use it, then the person who produces work that is worse than generic quality work will benefit because the AI will increase the quality of the work they can produce while making their lower price point an advantage over someone who now needs to put in even more effort to justify their higher price point.

Pakistan may have few college graduates now, but their number is rising rapidly.

Pakistan’s college graduates may not be as high quality as their counterparts in other countries, but AI now means that the quality differential will be lessened, and the price difference – ever in the Pakistani graduates’ favour – will become the dominant effect.

Higher education in Pakistan is not good. But it might just be good enough. Especially in the age of AI. n

Does the bank know what it wants to achieve, or is taking a leap of faith?

IBy Hamza Aurangzeb

t has taken a while, but Pakistan finally has its first digital bank. After nearly three years, the State Bank of Pakistan has given a digital banking licence to Easypaisa, which was one of many contenders that had first made a bid for this pioneering opportunity.

This marks a watershed moment in Pakistan’s digital economy. In less than a decade, Easypaisa has been one of the leaders, along with JazzCash, in making digital transactions and digital money common in Pakistan. These institutions have also played a big role in pushing conventional banks into improving their digital products and services.

But what does it mean now that Easypaisa has a digital banking licence? They have already made their place in Pakistan’s

financial history, redefining how the transfer of money works. But this position came at a cost. Telenor Microfinance Bank, the entity behind Easypaisa, has often run into its fair share of complications. Most of these complications are a result of expanding their operations. As a result, the bank frequently found itself in dire straits, requiring multiple bailouts from its sponsors in the form of equity injections. The most recent occurrence was in November 2024, when Telenor Group and Ant Group collectively invested $10 million into the institution for its smooth transition to digital retail banking, taking the total of equity injections in the bank to $319 million since 2018.

Although the bank has displayed a mixed performance over the past two decades of its existence, it is one of the few pioneers in microfinance, which has achieved a turnaround and is on a growth trajectory over the past

few years. But, the question arises why has Telenor Microfinance Bank rebranded itself as Easypaisa Digital Retail Bank? Does the bank have a plan for digital retail banking or has it just jumped onto the bandwagon?

A brief history

Easypaisa Digital Retail Bank traces its history back to September 2005, when it was founded as Tameer Bank, by Nadeem Hussian, a former Citibanker. He envisioned taking the microfinance industry to new heights, where microfinance institutions operated on a massive scale, generated healthy profits, and created an impact on the low income strata of society, instead of merely functioning as a charitable institution.

Tameer bank achieved success, initially. During the first year of operations, it opened

15 branches in Karachi and served 20,000 customers, where it did not witness a single delinquency. However, this success proved to be fleeting as the delinquency rate shot up to 25% during the second year, led by poor loan recoveries. Moreover, rising operational costs and default loans exacerbated the situation and shrunk the bank’s equity. Now during these times of crisis, the bank in order to grow sustainably and optimize its operational risk, commenced lending to farmers and individuals against jewellery as collateral.

However, the bank soon realized that the brick and mortar model was unsustainable, as opening new branches required a lot of capital. Moreover, the small loan sizes simply did not generate adequate revenue to finance the expenses of the branch, which disbursed them. This compelled Hussain to move towards the largely unexplored terrain of branchless banking that we celebrate today.

The bank breathed a sigh of relief when the SBP introduced regulations for branchless banking in 2008, which persuaded telcos to venture out into the microfinance sector as well. The telcos sniffed an opportunity, where they could join hands with banks and launch mobile financial services across the country.

During its third year, Tameer Bank began negotiations with Telenor Pakistan, which intended to secure a microfinance license by acquiring a functioning bank instead of starting one from scratch. This deal was the need of the hour as Tameer Bank’s equity was in a dreadful state and it was going through a liquidity crunch. On the contrary, Telenor Pakistan was experimenting with new income streams to expand revenue. Its ARPU had dwindled from $15 to $2, despite expanding customer base, but most of its customers had limited purchasing power. Hence, Telenor’s voice services didn’t prove to be profitable, propelling it towards financial services, where it could leverage its user base to enhance revenues.

Telenor Pakistan finally acquired a

majority stake of 51% in Tameer Bank after extended negotiations. Soon after both Tameer Bank and Telenor Pakistan collaboratively launched a branchless banking arm, Easypaisa, the first of its kind in Pakistan during October 2009. In 2016, Telenor decided to acquire the remaining 49% stake in Tameer Bank, which made it a wholly owned subsidiary of the telco. Meanwhile, Easypaisa was fully transferred to Tameer Bank in 2017 and the entity was revamped to Telenor Microfinance Bank (TMB).

In November 2018, Telenor Microfinance Bank went through another ownership restructuring process, when it struck a tactical partnership with Ant Financial Services Group, the financial services subsidiary of Chinese e-commerce giant, Alibaba. The Ant Group invested a whopping $184.5 billion for 45% of the bank via its investment arm, Alipay 2019, valuing the bank at $410 million, while the rest of the 55% remained with Telenor Pakistan B.V.

During contemporary times, Easypaisa along with four other banks was granted an NOC by the SBP in January 2023 to establish digital retail banks, which progressed to an In Principle Approval (IPA) in September 2023. Finally, Easypasia was granted the first com-

mercial license for digital retail banking by the SBP recently in January 2025.

Initial hiccups

As Ant Group entered the scene, the Telenor Microfinance Bank reoriented itself towards digitizing the financial services landscape in Pakistan through harnessing the potential of the mobile wallet market with Easypaisa. The bank adhering to its redesigned digital-first strategy launched Easypaisa loans in 2018, which was a nascent type of digital nano loan in Pakistan. However, as the bank strived to enhance its digital footprint with this new gameplan, it took a heavy toll on its financials as its marketing expenses escalated swiftly, which further soared the administrative costs, ultimately impairing the bottomline.

Telenor had developed a reputation as an accomplished institution, primarily due to the spectacular performance of Easypaisa, which was for all practical reasons a monopoly for around a decade. However, competition intensified with the entrance of Mobile Microfinance Bank in the mobile wallet space through Jazz Cash and ultimately Easypasia lost the crown to JazzCash in 2018.

The Telenor Microfinance Bank faced one challenge after another following this new path. In 2019, the bank discovered rampant employee frauds, which contributed towards heavy loan defaults. This led to a significant rise in the bank’s losses. The bank had accumulated losses of Rs. 16.6 billion by the end of 2019.

Just as the bank was overwhelmed with the consequences of employed fraud and heavy loan defaults, it was struck by another catastrophic event, the COVID-19 pandemic. As the economy slowed down and business remained closed for months, the majority of the borrowers of the bank found themselves unable to repay their loans. This was mainly because the core customer base of the bank

belonged to the low income segment, the segment affected the most during the pandemic. As a result, the bank’s infection ratio skyrocketed from a mere 4% in 2018 to an astounding 21% in 2019 and remained elevated for the next couple of years. It was only in 2022, that the bank got a hold of the situation and shrunk its infection ratio to single digits.

During COVID-19, the SBP waived off the fee for Inter Bank Funds Transfer (IBFT), which aggravated the financial health of the bank as it was stripped off of its main source of branchless banking income. The bank reported a loss on branchless banking operations for three consecutive years from 2020 to 2022, which represented a cumulative sum of Rs 2.221 billion.

Expanding the digital footprint

Although the new path of the bank was fraught with difficulties, it was not all dark and gloomy for the bank. It achieved the core objective by expanding its digital footprint exponentially across the country. As of Dec 2023, the bank boasts an active app user base of 9.6 million, whereas it stood at only 0.6 million in 2018, a ten-fold increase in app users is absolutely unprecedented. However, its growth is not restricted to app users, its total number of active wallets has also mushroomed from 3.3 million in 2018 to 13.2 million by the end of 2023. This means that around 72.9% of the users transact digitally as of 2023, while that figure hovered around 17.0% during 2018.

The bank has also been able to persuade an increasing number of customers to deposit money in its treasury, increasing the deposits of mobile wallets from 14 billion in 2018 to 46.85 billion in 2023. Furthermore, the bank’s transactions have burgeoned over the past five years, where the quantum of transactions has gone from 305.8 million in 2018 to 2.1 billion in 2023. Majority of these transactions are conducted digitally, which is congruent with the general trend of branchless banking in the country. Last but not the least, the bank’s investment in its digital infrastructure has borne fruit as the bank processed payments of Rs.6.8 trillion during 2023, whereas its annual throughput was only Rs.682.0 billion in 2018, As per the latest reports, the bank processed a gigantic sum of 9.5 trillion through 2.7 billion transactions in 2024.

Now coming towards the loan book of Telenor Microfinance Bank, since it got plagued with major frauds and loan defaults, the bank decided to reorganize it. It sanitized the loan book by writing off loans, and exiting the agriculture bullet lending segment altogether, where majority of the fraud was unraveled. However, the bank took a hit of

around $14-15 million in the form of impairment charges during the whole process, which was funded by the sponsors Telenor Group and Ant FInancial, allowing the bank to start with a clean slate. The bank’s sponsors injected an equity in excess of $100 million, where $45 million were provided in 2020, $70 million in 2021, and $37 million in 2022, respectively.

The resurgence

After blowing up its book and starting afresh the bank formulated a new strategy, one that allows it to reach a wider audience for financial inclusion and earn fat fees to become profitable through leveraging its digital infrastructure.

Firstly, the bank reintroduced its category of lending product known as nano loans, which had been discarded during times of crisis post COVID-19. Following its new strategy, the bank started giving out loans to more and more customers but of smaller sizes, absolutely miniscule to be precise. The average loan size disbursed by the bank hovered around 57,636 in 2018 but it fell drastically to 2,529 by 2023. Why was that the case?

Well, the bank trimmed its risk significantly by offering small loans to a wide and diversified customer base for a shorter tenor. Moreover, the bank, while dealing with nano loans, deducted its interest upfront from the principal amount before disbursing it.

Now, since the bank served an underserved or an underbanked customer base, where there is a higher probability of default and dearth of financing options, it could charge a high interest rate on a weekly basis, which translated to a three figure Annual Annual

Percentage Rate (APR), resulting in bumper profits for the banks.

Not to forget that the bank cashed in big time on the high interest environment since the mid of 2022. The Telenor Microfinance bank increased its net interest income massively through nano loans and minimizing cost of deposits by focusing on low cost deposits. But why was the bank not doing this before?

Before 2018, the bank didn’t have the kind of digital infrastructure, footprint, and processes required to serve a wide audience at such a massive scale. It depended on brick and mortar branches that were present in numerous regions but still inadequate to deal with the rapidly growing demand. The bank being true to its digital first strategy, invested heavily in its digital infrastructure and processes (Read: Easypaisa) to expand its digital footprint, while at the same time closed down physical branches gradually.

This was an intentional move on the bank’s part to reduce its costs and promote financial inclusion by serving customers digitally, which had become possible due to the rampant penetration of smartphones in Pakistan. The Telenor Microfinance Bank had 103 branches in 2018 and as of Sep 2024, they only have 46 branches. More than half of the branches vanished but the business still expanded, better than ever before because the bank could disburse credit and collect repayments rapidly through technology. Both the telco backed microfinance banks, Telenor Microfinance Bank and Mobilink Microfinance Bank have remained ahead of the curve by leveraging their digital secret sauce and resourceful sponsors.

However, the bank’s transformation is not restricted to the interest based income or the digital arena. The bank, realizing that the majority of the population is still inclined towards cash, tweaked the strategy for dealing with cash to generate additional revenue. In 2023, the bank began charging customers on depositing money and a huge jump was observed in the branchless banking income. It is truly ingenious as it serves a dual purpose, firstly it boosts the non-interest income of the bank; secondly, it discourages customers from cash and compels them to become a part of the digital ecosystem of the bank, creating a winwin situation for the bank.

Dissecting the non-interest income of the bank reveals earnings from fee, commission, brokerage almost doubled during the year 2023, primarily driven by improved branchless banking income. The branchless banking income consists of fees charged from customers while depositing and withdrawing funds through agents, this income stream was temporarily unavailable to the bank from 2020 to 2022. According to latest reports, the bank earned an income of Rs. 9.4 billion from its branchless banking operations during 9M2024,

The transition to Digital Retail Bank

The transition of Telenor Microfinance Bank into Easypaisa Digital Retail Bank is the next logical step in its evolutionary development because it has established an adequate digital presence and has developed a vast customer base by operating in the country for the past two decades.

Easypaisa, as per its digital first strategy, envisions to expand its digital footprint across the country through technological prowess and diminish its dependence on brick and mortar branches. Moreover, it wants to diversify its customer base further by diluting the concentration of its core customer base of low income rural population. The bank intends to market its services to urban populations such as the youth, women, freelancers, and salaried individuals; along with micro, small and

medium enterprises, segments which are often overlooked by commercial banks.

When we look at the average number of transactions per wallet, it stands at only 13.5 transactions a month, while the average transaction value remains a paltry sum of Rs. 3,214 as of 2023. The bank realizes that in order to enhance its average transaction value and resultantly, its branchless banking income, it needs to persuade an increasing number of customers from the urban population to use its services.

It has introduced an extensive set of services such as digitized accounts for current transactions, savings, consumer lending, cross border payments, international remittances and foreign currency with enhanced balance and transaction limits. All of this along with value addition services like wealth management and insurance tools, where the bank will utilize the latest techniques of predictive analytics and machine learning for risk profiling and preventing frauds. Thus, the license for digital retail banking is well suited for this purpose as it warrants the institution to address the needs of a wide range of customers. However, another reason contributing to the microfinance bank’s transition is the vulnerability of its nano loan strategy. The bank’s nano loan strategy proved to be

successful during both 2023 and 9M2024, where it collected service fees of Rs.2.4 billion and Rs.5.7 billion, respectively. Nevertheless, this source of income remains capricious due to declining interest rates and the inherent credit risk of customers from the low income segment. Although the bank’s infection ratio is still manageable, it has increased from 6.2% to 10.8% during 9M2024. Also not to forget, that the equity injections from sponsors have played a fundamental role in moving the bank’s bottomline into positive territory.

Easypaisa Digital Retail Bank wants to achieve sustainable growth by serving a diverse range of customers that belong to various strata of society, breaking away from the shackles of its addiction to equity injection. However, its journey as a digital retail bank will not be a walk in the park. Since it will now be going after urban customers, it will directly be competing with scheduled banks, EMIs, and other digital retail banks. Lastly, we must not forget JazzCash, which although hasn’t been granted a digital retail banking license yet but yearns for one. With minimum physical presence, segments such as MSMEs and urban salaried class, especially the older customers class who are crucial for the bank’s deposits will be a hard nut to crack for the institution. Moreover, the bank needs to invest perpetually in its technological infrastructure in order to remain competitive and protect its customers from hacking, phishing, and digital scams.

Although Easypaisa Digital Retail bank is on the right path in terms of expanding its digital footprint and reaching out to more urban customers to uplift its revenue. However, it remains to be seen whether Easypasia will truly be able to come out of the shadows of its own legacy as a microfinance institution dedicated to low-income groups and emerge as a dependable alternative financial solution for all segments of society including the urban population. n