09 The economy catches a breath but not much more

12 Banks: Rent-seekers, or responsible financial intermediaries?

18 Haball completes $52 million equity and debt raise — inside the Pakistani fintech company’s model and ambitions

19 Copper and gold mines at Chagai: what it could mean for the mining sector

21 Honda Atlas’ vague hybrid vehicle announcement leaves more questions than answers

22 Why Liberty Power backed out of buying out Engro’s energy business

24 Trapped talent, rising profits: Systems Ltd and the economics of immobility

25 Pakistan’s oil and gas reserves see first growth since 2020

27 Can Starlink’s Direct to Cell turn the tide for Pakistan’s telecom sector?

Publishing Editor: Babar Nizami - Editor Multimedia: Umar Aziz Khan - Senior Editor: Abdullah Niazi

Editorial Consultant: Ahtasam Ahmad - Business Reporters: Taimoor Hassan | Shahab Omer

Zain Naeem | Saneela Jawad | Nisma Riaz | Mariam Umar | Shahnawaz Ali | Ghulam Abbass

Ahmad Ahmadani | Aziz Buneri - Sub-Editor: Saddam Hussain - Video Producer: Talha Farooqi

Director Marketing : Muddasir Alam - Regional Heads of Marketing: Agha Anwer (Khi)

Kamal Rizvi (Lhe) | Malik Israr (Isb) - Manager Subscriptions: Irfan Farooq

Pakistan’s #1 business magazine - your go-to source for business, economic and financial news. Contact us: profit@pakistantoday.com.pk

The economy catches a breath but not much more

According to the recent Asian Development Outlook report, Pakistan’s economy is showing promising signs of recovery

From a near-crisis marked by skyrocketing inflation, dwindling foreign reserves, devastating floods in 2022–2023, a very real risk of default and an overall bleak state of affairs, Pakistan seems to have managed to engineer a tentative but noteworthy turnaround. Inflation, once as high as 29%, has tumbled to just 1.5% as of February 2025. Foreign reserves, critically low as of last year, have more than doubled. And the agricultural sector, ravaged not long ago, has surged back with record harvests.

Yet behind these hard-won gains lies a landscape still littered with structural weaknesses; mounting debt, a shrinking industrial base, and the persistent exclusion of women from the workforce. Pakistan’s recovery, fragile as it may be, reflects the complex reality of economic stabilisation in an emerging market, where each step forward requires navigating a minefield of political, fiscal, and social challenges.

Can Pakistan’s economy recover after weathering severe economic turbulence?

According to the Asian Development Outlook 2025 (ADO), Pakistan’s economy regained momentum in fiscal year 2024, as disciplined macroeconomic management and meaningful progress on structural reforms helped stabilise the economy, rein in inflation, and restore investor confidence by attracting much-needed external financing.

After contracting 0.2% in FY’23, Pakistan’s economy expanded by 2.5% in FY’24, driven primarily by a robust agricultural sector that grew by 6.2%. This remarkable turnaround in agriculture followed devastating floods in FY’23 and featured record wheat and rice harvests, with cotton production more than doubling to its highest level in six years.

The country’s fiscal position has also shown improvement. The overall fiscal deficit shrank from 7.8% of GDP in FY’23 to 6.8% in FY’24, while the primary balance achieved a surplus of 0.9% of GDP, the first surplus since 2004. This fiscal consolidation came largely from increased revenue measures and rationalised subsidies, despite rising interest payments that consumed 61% of total government revenue.

“Pakistan has made significant progress

in stabilising its economy through tight macroeconomic policies and structural reforms,” said Dr. Farrukh Iqbal, former Director of the Institute of Business Administration in Karachi. “The agricultural recovery has been particularly impressive, providing both food security and export earnings when the country needed them most.”

Perhaps most notably, inflation has fallen dramatically, from 29.2% in FY’23 to 23.4% in FY’24, and further to just 6.0% during the first eight months of FY’25. By February 2025, the monthly inflation rate stood at a mere 1.5%, down from 12.6% in June 2024. This impressive disinflation has allowed the State Bank of Pakistan to cut its policy rate by a cumulative 850 basis points, from 20.5% in June 2024 to 12.0% in January 2025.

Closely tied to the reform agenda outlined under the recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) program, Pakistan’s external position also shows improvement. Measures mandated by the IMF, such as transitioning to a market-based exchange rate, enhancing transparency in currency markets, and cracking down on illegal foreign exchange trade have played a pivotal role in stabilising the rupee and restoring confidence among investors and remittance senders.

Fiscal consolidation efforts, including the rationalisation of imports and subsidy reforms, further reduced pressure on the current account. Crucially, the successful implementation of these reforms unlocked external financing from multilateral and bilateral partners, boosting foreign exchange reserves and helping Pakistan reverse its current account deficit. This alignment with IMF expectations not only provided much-needed liquidity but also signaled a broader commitment to structural stability, reinforcing Pakistan’s credibility in global financial markets.

Pakistan’s external position has improved considerably, displayed by the current account deficit, which was halved from $3.3 billion in FY’23 to $1.7 billion in FY’24, as merchandise exports grew by 11.1% and remittances increased by 10.7% to $30.3 billion. In fact, the first seven months of FY’25 saw the current account post a surplus of $682 million, reversing a $1.8 billion deficit recorded during the same period last year.

According to AOD’25, foreign exchange reserves have more than doubled from $4.4 billion at the end of FY’23 to $9.4 billion by the end of FY’24, and further increased to $11.4 billion by February 2025. This improvement in reserves has significantly enhanced import coverage from 0.6 months to 1.8 months and is expected to reach $13.0 billion (2.9 months of import cover) by June 2025.

Together, these developments paint a markedly improved picture of Pakistan’s external sector. The sharp narrowing of the current account deficit, rising remittance inflows, and a rebound in exports have all contributed to a stronger external balance. Meanwhile, the doubling of foreign exchange reserves, driven by disciplined macroeconomic policies, IMF-backed financing, and tighter regulatory controls, has significantly enhanced the country’s import coverage and financial resilience. While challenges remain, the turnaround in Pakistan’s external position signals growing stability and renewed confidence in its economic management.

At a critical crossroads in its economic journey, Pakistan turned to the IMF as a lifeline to restore stability and confidence in its financial future.

After concluding a nine-month standby arrangement worth approximately $3 billion in April 2024, Pakistan secured a more ambitious 37-month Extended Fund Facility (EFF) totaling around $7 billion in October 2024. This shift marked not only a continuation but a deepening of the country’s commitment to structural reform and long-term economic recovery.

Finance Minister Muhammad Aurangzeb, speaking at a press conference following the EFF’s approval, underscored the program’s significance in rebuilding market trust, “The IMF program provides a structural framework for reforms that are essential for sustainable economic growth.”

The EFF’s key focus areas include fiscal consolidation, reforming the energy sector, improving tax collection, and expanding the social safety net. One of the most notable achievements to date is the successful implementation of an agricultural income tax across all provinces, an ambitious policy that had long faced political resistance. This reform signals a strong willingness by the government to take on long-standing challenges in order to drive sustainable development.

Despite these positive developments, Pakistan’s economy still faces substantial challenges. The industrial sector contracted by 1.7% in FY’24 for a second consecutive year, reflecting declines in utilities and construction. Investment decreased by 2.6%, with gross fixed capital formation falling by 3.6% due to a challenging political and business environment.

High interest payments on public debt remain a significant burden on the fiscal position. Public debt grew by 20.3% annually over the past two years to reach PKR 71.2 trillion in June 2024, with interest payments rising from 6.8% of GDP in FY’23 to 7.7% in FY’24.

Dr. Sajid Amin, Deputy Executive Director at the Sustainable Development Policy Institute in Islamabad, highlighted, “Pakistan’s debt servicing costs crowd out productive expenditure on development, education, and healthcare. This constrains the country’s longterm growth potential and ability to address poverty and inequality.”

The first quarter of FY’25 showed slower growth of 0.9%, down from 2.3% a year earlier, mainly due to a significant slowdown in agriculture. Production of key crops fell by 11.2% in Q1 FY’25, compared to a 30.0% rise a year earlier, as reductions in area under cultivation, changing weather patterns, and high input costs cut the output of cotton, rice, and sugarcane.

Low participation of women in the labor force in Pakistan is a tale as old as time. While women comprise almost half of Pakistan’s working-age population, their labor force participation remained low at 23% in FY’21, below the average of 27% in South Asia and 35% in lower-middle-income countries globally.

This gender gap represents a massive loss of potential economic output. According to World Bank estimates, Pakistan’s GDP could increase by 30% if women’s labor force participation matched that of men.

Several factors contribute to this disparity. Limited access to quality education and vocational training makes it difficult for women to compete in the job market. Deep-rooted patriarchal social norms and cultural constraints discourage women from seeking employment outside the home. A lack of safe, accessible, and affordable transportation limits women’s mobility, hampering their ability to commute safely to and from work.

The government has recognised the importance of addressing this issue. The National Transformative Gender Agenda under the National Gender Policy Framework 2022

emphasizes strategies to equip women with employable skills and expand access to employment opportunities.

Some successful initiatives include the Women on Wheels program, introduced in 2023, which offers 22,000 women who work in the public sector the opportunity to purchase scooters and motorcycles at discounted prices. Another example is the Peshawar Bus Rapid Transit project, which increased female public transport use from 2% in 2020 to 30% in 2024 and expanded women’s employment in the transport sector from effectively nil to over 10%.

Dr. Hadia Majid, Associate Professor of Economics at Lahore University of Management Sciences, emphasised the importance of such initiatives, “Transport mobility is a critical constraint for women’s economic participation in Pakistan. Programs that address this constraint directly can have a significant impact on women’s employment and entrepreneurship opportunities.”

Pakistan’s energy sector continues to pose significant risks to fiscal sustainability. Circular debt in the power sector, payment arrears throughout the energy supply chain, has been a persistent problem, reaching approximately PKR 2.6 trillion in 2024.

The government has implemented several measures to address this issue, including adjustments to electricity tariffs and reductions in transmission and distribution losses. However, these measures have often been met with public resistance due to their impact on the cost of living.

Energy sector reform is a key component of Pakistan’s current IMF program. The government plans to increase gas prices for captive power plants, which is expected to raise input costs for these private facilities and potentially contribute to inflation in the coming months.

“Energy sector reform is perhaps the most challenging aspect of Pakistan’s economic stabilization program,” said energy expert Ali Khizar, Head of Research at Business Recorder. “The government needs to balance the competing objectives of reducing fiscal risks, ensuring energy security, and maintaining affordability for consumers.”

Pakistan’s economic outlook shows cautious optimism, with growth projected at 2.5% in FY’25 and 3.0% in FY’26. Inflation is expected to moderate to 6.0% and 5.8% over the same period. However, the durability of this recovery hinges on the

effective implementation of structural reforms currently underway.

Despite recent progress, several risks threaten to derail the fragile recovery. Domestic policy slippages could hinder critical disbursements from multilateral and bilateral partners, drying up essential financial inflows and putting renewed pressure on the exchange rate. Political instability also looms large, as rising tensions could erode investor confidence and dampen private sector activity. Environmental vulnerabilities, such as insufficient rainfall and the risk of drought, pose further threats to food security and agricultural productivity.

External challenges remain equally pressing. Volatility in global food and commodity prices, as well as shifting global trade policies and interest rate trends, could destabilize exchange rates and strain Pakistan’s external accounts.

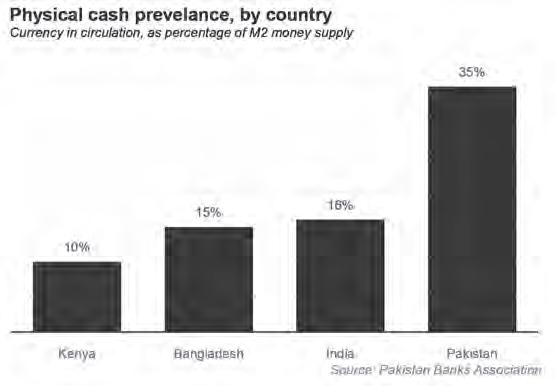

According to ADO, in order to secure sustainable and inclusive growth, Pakistan must address a set of structural priorities. Strengthening public finances is paramount, particularly by expanding the tax base and enhancing social spending. With a tax-to-GDP ratio hovering around 9.5%, one of the lowest in the region, Pakistan lacks the fiscal space needed to fund critical public investments and services.

Bolstering external resilience through export diversification and the continued inflow of remittances is equally vital. Currently, more than half of Pakistan’s exports are concentrated in the textile sector, exposing the economy to sector-specific risks and limiting its ability to respond to global market shifts.

Reforming state-owned enterprises, especially in the energy sector, is crucial for long-term fiscal stability. These entities continue to generate large deficits due to inefficiencies and governance challenges, demanding urgent structural reforms to restore financial viability.

Improving the business environment is another key pillar for growth. Pakistan ranks 108th out of 190 countries in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business index, underscoring the need for reforms in areas like contract enforcement, tax administration, and business registration to foster private-sector-led development.

“Pakistan has shown resilience in the face of significant economic challenges,” observed Dr. Rashid Amjad, former Vice Chancellor of the Pakistan Institute of Development Economics. “The path forward requires sustained commitment to reforms, political stability, and a focus on inclusive growth that benefits all segments of society.”

As Pakistan charts its course toward economic resilience, its experience offers critical lessons for other emerging economies. Balancing fiscal consolidation, monetary stability, structural reforms, and social protection remains a formidable challenge. Is Pakistan prepared to meet this challenge? n

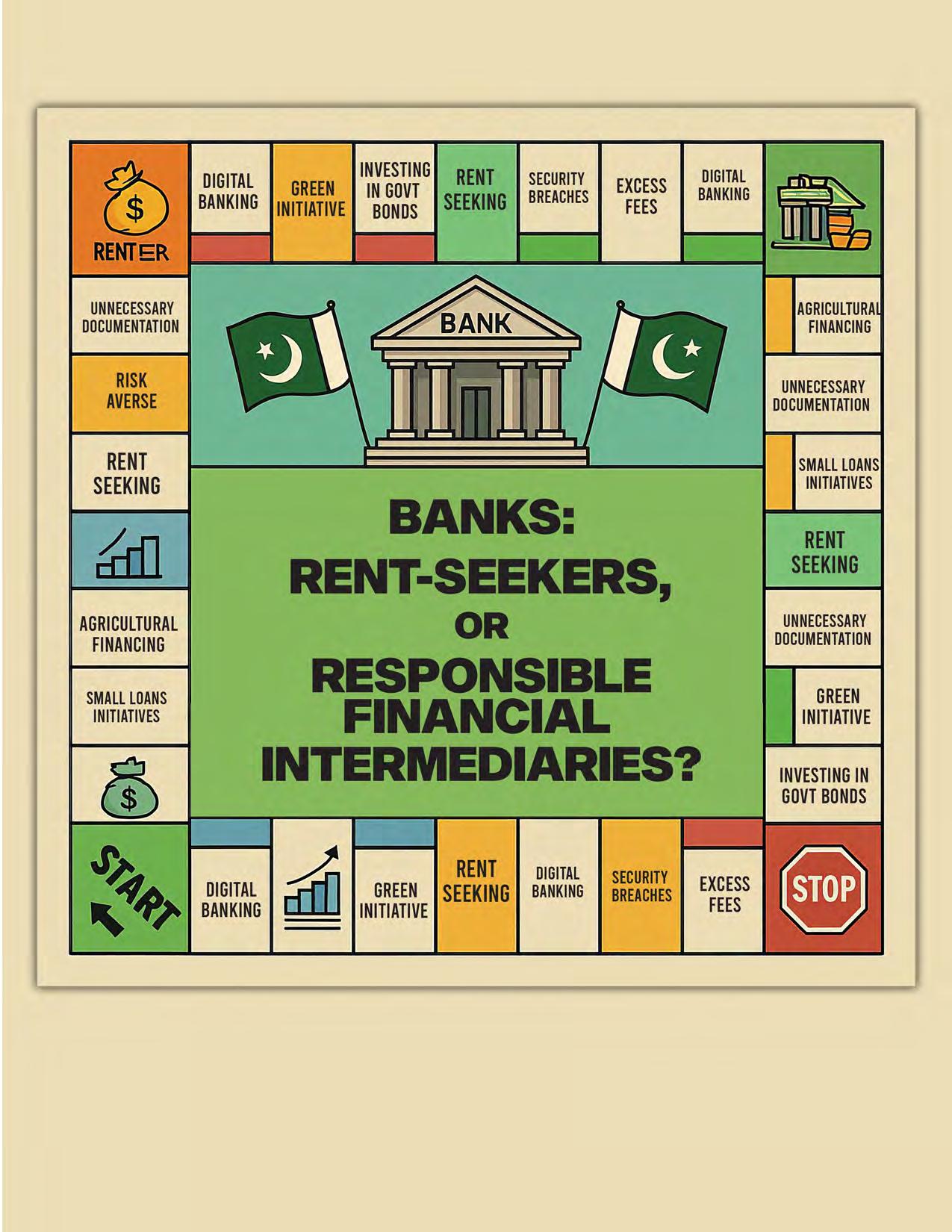

The chairman of Pakistan’s banking lobby responds to criticism of his industry, acknowledging some charges as fair, but pushing back on the charge that the banks are rent-seekers

By Zafar Masud

[EDITOR’S NOTE: We normally try not to publish the perspectives of Pakistan’s various lobbying groups, owing to the fact that the vast majority of them want to tell a sob story with no real value to our readers. We made an exception in this particular case because the head of Pakistan’s banking association wanted to say something discrete, and back it up with data, in a manner that we felt would serve our readers.]

Pakistan’s banking sector is now the largest taxpayer. We finance almost 100% of the government’s budget deficit. We are one of the country’s largest employers, with over 200,000 people employed. And we are more inclusive employers than most other sectors in the economy.

Despite this, we face a lot of criticism, that we are rent-seekers, or that we do not function as adequate financial intermediaries for the economy. Some concerns raised by people outside our industry are valid. Others perhaps require some additional context. All deserve to be addressed.

I believe in taking criticism on the chin, and in this article, I hope to address some of the most important criticisms leveled towards the Pakistani banking sector. I do so in my capacity as the chairman of the Pakistan Banks Association, the group meant to represent the industry’s interests before the government, industry, and the public. What follows below is a modified version of a speech I delivered at the first Pakistan Banking Summit, which took place in Karachi on February 23, 2025.

There are six main criticisms that I will address:

1. The banking sector actively lobbies the government against its own taxation;

2. The banks lend entirely to the government and do not lend to the private sector;

3. The banks offer little by way of lending to small businesses and to agriculture;

4. The banks have not made adequate efforts to improve financial inclusion;

5. That we do not contribute to the country’s economic dynamism;

6. And that we have been slow to adopt the conversion towards Islamic finance.

Let us address each of these. We will present not just our perspective, but also some data and analysis to back up our perspective.

As I stated at the outset, Pakistan’s banking sector is now its largest taxpayer. We recently overtook the oil and gas sector as Pakistan’s

largest taxpayer, and the reason this happened is not because banking sector profits outpaced those of the oil and gas sector, but because the tax rate we face is so much higher than any other sector of Corporate Pakistan.

The effective tax rate faced by banks in Pakistan has been higher than other sectors for some time now, but has recently hit a record 54% of our corporate income. And that, by the way, is before the recent payment of the “windfall tax”. While the case is still pending litigation, we have paid that tax in advance, based on our own industry’s norms, despite the toll it takes on our cash flows. After taking that into account, the effective tax rate goes to 60%. Compare that to the 29% faced by other corporations in Pakistan.

In financial year 2024, we directly contributed more than Rs840 billion in taxes, and we expect to continue to be the highest taxpaying sector in 2025, despite expecting lower profitability this year. We remain the largest withholding agent for taxes collected by the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR). Our employees, relatively well-compensated by national standards, are also major contributors to the government’s tax collection.

It is true that the Pakistan Banks Association did recently lobby the government against proposed tax on the banks’ balance sheets based on what proportion of their lending book consisted of lending to the government versus the private sector. Colloquially, this became known as the ADR tax, after the acronym Advances-to-Deposits Ratio, which was the financial metric being used to determine the incidence of this tax.

There is also the “windfall tax” which seeks to elevate our tax rates even further based on an arbitrary and undefined standard of revenue from certain business lines being too high. These are both distortive taxes which are likely to have more negative side-effects and few, if any, benefits to the economy.

Did we actively lobby against both of these taxes? Yes, we did. But there is context there that is important.

We did so for two reasons.

Firstly, we are already a very heavily taxed sector, and we believe additional taxes over and above the already elevated levels of taxes we pay would be unfair. Our tax rate is already 1.86 times higher than the regular corporate income tax rate. If we then accept even more taxes over and above this, there would be no end to the demands placed on us.

And secondly, we believe that the ADR tax – as it had been proposed – would have been distortionary and created undesirable incentives for the banks that would have directed financial institutions to undertake lending activity – with money that ultimately belongs to ordinary people who are our depos-

itors – that may have helped us avoid the tax, but instead risk depositors money on riskier lending.

That this tax was proposed at all is tied to the next criticism, which is that the banks do not lend to the private sector. But before we address this, let us first look at what happened after the supposedly “successful” lobbying against the ADR tax.

The reason the banks, with the support of the State Bank of Pakistan, were able to convince the government to withdraw the ADR tax proposal was in part because we ended up giving ground on the “windfall tax”, which further raised our corporate income tax rate by another ~5% of income.

The justification of this additional tax was the so-called “windfall profits” that the banks earned on foreign exchange income. We did not agree with this characterisation of that income. The banks did not create volatility in the foreign currency market, but that increased volatility did increase the cost of providing foreign exchange services. Increased fees for those services were a natural consequence of market conditions.

Volatility is a double-edged sword. While some banks made profits with this volatility, the others lost money primarily due to net open position on their foreign exchange exposure. This is a normal course of events in financial markets. The banks that lost money did not get any more sympathetic treatment from the government, but the banks that made profits were forced to cough up additional taxes through this “windfall tax” garb. It is a lopsided and unjust method of taxing market dynamics.

But beyond this, we do not agree with the principle of a windfall tax. Today, the excuse was foreign exchange revenue, tomorrow it will be net interest margins deemed too high, and the day after it will be something else. Why does the source of revenue matter, when all profits are already taxed, and that too at an already elevated rate?

And this, by the way, is not evenly distributed across the industry. Some banks made money and others lost. It was not a market event that caused uniform profit increases across the industry.

And yet despite this higher contribution of tax revenue, the government’s tax collection arm – the FBR – has not had the most collaborative of attitudes towards us. Banks were slapped with tax notices, and called tax defaulters even before the tax had been levied and became payable.

What we find disappointing is that the FBR has always had in the banks a collaborative partner that helps them when they need to meet revenue collection targets in the form of advance taxes currently north of Rs200 billion

for this year. We paid Rs72 billion in incremental taxes before the December 31 revenue collection deadline, and then paid another Rs30 billion ahead of another key revenue collection deadline within a few months, despite the matter still being under pending litigation in court.

There are many things that can be said about the banks. But shying away from paying taxes is not a fair allegation. We always accept fair taxation, and have even accepted the higher taxation rate levied on us. But when the taxation gets economically distortionary to the point of potentially creative risks for the financial system, and the broader economy, or when they get even more excessive, we will present our case before the government.

There is no denying the fact that the banks lend heavily to the government, and consequently do not lend as much of their deposit base to the private sector. But in this, as in many things, context is important.

There are two important pieces of context, one concerning the level of lending that is feasible to the private sector, and the second is the importance of bank lending to the government.

On the private sector lending side, we believe some introspection is in order on the bank of the private sector. There is a chronic problem of low documentation and a propensity of to remain outside the tax net. In addition, limited access to proxy data and low capacity for credit evaluation impede bank lending. Banks deal in documents, not goods.

Economic stagnation and lack of documentation perpetuate weak tax bases –restarting the cycle. Untaxed sectors constitute 52% of the economy, which then creates

liquidity gaps. Excessive government borrowing ostensibly siphons liquidity from private sector credit markets. And then restricted private sector investment stifles innovation, job creation, and economic growth.

Then, there is the blunt truth on the other side of the balance sheet: the banks do not have much of a choice when it comes to financing the government’s budget deficits. In the previous fiscal year, the banks constituted 99.8% of the government’s deficit financing. If we were to step away from playing that role, for the sake of argument to accommodate private sector per se, the ensuing economic crisis would be so severe that there would still be no credit flowing to the private sector.

There is, quite simply, “no option” for the banks but to continue lending to the government so long as the need for deficit financing remains at current levels. If that were to change, so would the banks’ lending to the government.

If we want the government to stop being the main avenue for bank lending, the country must undertake structural economic reforms to permit lower fiscal deficits. The banks do not possess the power to change the fiscal dynamics of the government and to blame us for providing its financing is unfair.

Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs), housing (mortgages) and agriculture are critical pillars of Pakistan’s economy, contributing significantly to employment, exports, and GDP. SMEs, for instance, contribute over 30% to GDP and employ around 80% of the non-agricultural labor force. Similarly, agriculture remains the backbone of rural livelihoods and food security, employing over 35% of the labor force. Despite

this, these sectors receive a disproportionately low share of private sector credit—only about 7% of private sector loans go to SMEs, and less than 5% and 1% of smallholder farmers have access to formal credit and mortgages, respectively. This discrepancy stems from a combination of structural and institutional factors that discourage banks from lending to these sectors.

One of the primary reasons is the high degree of undocumented economic activity within these sectors. Most SMEs, housing and small-scale farmers operate informally, without maintaining standardized financial records, tax filings, or verifiable income statements. This lack of documentation makes it extremely difficult for banks to assess the financial health and creditworthiness of potential borrowers. Since banks rely heavily on documentation to make lending decisions, the absence of such records renders lending to these sectors unviable.

Closely tied to this is the issue of collateral and formal credit histories. Most SMEs and smallholder farmers do not possess the kind of physical or financial collateral that banks typically require. Land records may be disputed or unavailable, and movable assets are often difficult to value or secure. Additionally, due to limited prior borrowing from formal institutions, these groups often lack credit histories, further increasing the perceived risk from the bank’s perspective. In essence, banks view these borrowers as “high-risk, low-return” clients.

Access to proxy data—which could help build credit profiles in the absence of traditional documentation—also remains limited. While innovations like digital payment histories or utility bill records could potentially serve as proxies, such data is either not readily available or not yet integrated into the credit appraisal systems of banks. Since banks are geared to deal in documents rather than goods

or informal networks, this disconnect limits their ability to engage with these non-traditional borrowers.

Moreover, the prevalence of informal credit sources further complicates the situation. Many SMEs, housing and farmers rely on moneylenders, traders, or family networks for financing, which—despite high interest rates—offer speed, flexibility, and minimal paperwork. These informal channels are often more accessible than banks, particularly in rural or peri-urban areas. As a result, there is less incentive for borrowers to transition to formal lending systems, and banks find it difficult to compete with these entrenched informal networks.

In conclusion, the limited flow of credit to SMEs and the agriculture sector in Pakistan is not due to a lack of need or potential, but rather due to structural mismatches between how banks assess risk and how these sectors operate. Without efforts to formalize financial records, establish alternative credit assessment mechanisms, and reduce reliance on collateral, banks will continue to view these sectors as unbankable. Unlocking credit for SMEs, housing, and agriculture will require targeted policy interventions, improved data infrastructure, and a rethinking of traditional banking models to better align with the realities of Pakistan’s economic base.

On the matter of financial inclusion, we are also accused of not doing enough. To some extent, that criticism is fair. But there is substantial improvement on that front.

The number of bank accounts that maintain balances less than Rs25,000 – which are typically held by the working class and the poor in Pakistan – have increased 9 times in the last five years. We have seen a substantial

increase in women’s financial participation. The proportion of adult women who had a bank account in Pakistan was 14% in 2021. Just two years later, in 2023, that proportion had hit 43% of all adult women, a tripling in share of women with bank accounts.

Yes, there is still there is a long way to go. But mobile banking, e-commerce, internet banking, all are on the rise. And there are several initiatives to help accelerate progress on all of these fronts.

The State Bank of Pakistan, for instance, has allowed banks to undertake a tiered approach to its Know-Your-Customer (KYC) regulations for the banks, allowing a lowered documentation burden for people seeking to open low volume, low amount bank accounts via Branchless Banking, or mobile wallets.

Raast, the digital payments system, is already causing transaction costs to evaporate, further incentivizing more people to use the formal banking system, even for the smallest of transactions, which were previously costly for banks to service and thus faced high costs as a percentage of the total transaction size.

And we are now digitally onboarding more merchants aggressively so that they can accept electronic payments more easily. This expansion is not without cost, and we are taking a hit to our profitability in the short term to foster a more documented economy in the long term. Despite most banks being publicly listed companies, we are demonstrating an ability to put long term gains ahead of short term profits.

We are also playing an increasingly proactive role in supporting the country’s economic development by

aligning its operations with the government’s key economic priorities. These efforts are particularly notable in four critical areas: Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs), agriculture, financial digitization, and housing.

On SMEs, banks are actively working to bridge the financing gap that has long hindered SME growth. One key development has been the introduction of digital supply chain finance, which leverages technology to provide working capital to SMEs based on their transactional relationships with larger businesses. This approach improves access to credit while reducing the need for traditional collateral.

Furthermore, banks have collaborated with the Small and Medium Enterprise Development Authority (SMEDA) in establishing the National Credit Guarantee Company Limited (NCGCL). This institution helps mitigate the risks associated with SME lending by providing credit guarantees to banks, thereby incentivizing them to lend more confidently. Additionally, banks are revising their internal processes to make lower-documentation lending more widely accessible to smaller businesses. By simplifying eligibility requirements and streamlining loan approvals, these efforts are helping to bring more SMEs into the formal financial system.

The pathbreaking project of “SME Perception Index” has already been initiated under the auspices of PBA whereby it will help in identifying the risks and opportunities in this backbone sector of the economy and enable the banks to be able to lend with confidence and perhaps aggressively in the absence of adequate documentation.

To support agriculture, banks are embracing innovative solutions like Electronic Warehouse Receipts (EWRs) financing. Through this system, farmers can store their produce in certified warehouses and receive a digital receipt, which can then be used as collateral for obtaining loans from banks. This model not only expands access to finance

for smallholder farmers but also reduces post-harvest losses and encourages better price realization. By financing against EWRs, banks are helping farmers gain liquidity without being forced to sell their produce immediately at unfavorable market rates.

To support fintech, banks are helping establish a Financial Data Exchange (FDX) platform. This system will allow individuals and businesses to securely share their financial data across institutions, paving the way for more personalized and accurate credit assessments—especially important for those with limited formal credit histories. Another revolutionary step on the part of the banking industry in Pakistan is to consider setting-up private equity fund to support the fintechs and start-ups in priority sectors.

Additionally, banks are expanding physical and digital infrastructure by deploying cash deposit machines (CDMs) in more urban and semi-urban locations. These machines allow customers to deposit cash anytime without visiting a bank branch, thereby improving convenience and reducing pressure on banking staff. Together, these efforts are increasing financial inclusion and strengthening the digital financial services ecosystem.

Access to affordable housing is a key policy priority, and banks are stepping up to address long-standing challenges in this sector. One critical area of reform is support for amendments to foreclosure laws, which aim to provide greater legal clarity and enforcement ability in case of mortgage defaults. These changes reduce the risk exposure for banks, making them more willing to offer long-term housing finance.

Banks are also working to standardize mortgage documentation, simplifying and harmonizing paperwork requirements across institutions. This standardization not only accelerates the mortgage approval process but also improves customer experience and

reduces operational costs. By making housing finance more efficient and less risky, banks are enabling more Pakistanis to achieve home ownership and contribute to the country’s broader economic stability.

Pakistan is undergoing a historic transformation in its financial system, as the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) has mandated a full conversion to Islamic banking by December 2027. This shift is in line with the ruling of the Federal Shariah Court, which called for all banking in the country to comply with Islamic principles. As a result, banks across Pakistan are actively transitioning their operations—from customer accounts and loan products to branch operations and financial structures—to align with Shariah-compliant models.

The conversion is not merely symbolic; it involves a comprehensive overhaul of the existing conventional banking framework. This includes transforming interest-based financial instruments into Shariah-compliant alternatives such as profit-and-loss sharing models, leasing arrangements (ijarah), and Islamic bonds (sukuk). Conventional branches are being converted to Islamic banking branches, and customers are being offered products that align with ethical and interest-free financial principles.

While banks are making steady progress, government support remains critical in creating a conducive environment for a smooth transition. One key area where the government’s role is essential is the issuance of asset-light sukuks, which would serve as Islamic replacements for conventional government bonds. These instruments are vital for liquidity management options for Islamic banks.

Additionally, clarity on corresponding

banking arrangements is necessary, especially for managing foreign trade and international settlements in a Shariah-compliant manner. Banks that are foreign-owned or operate as branches of international institutions also require specific regulatory exemptions and guidance to align their global operations with local Islamic banking requirements.

PBA is fully and unwaveringly committed to the conversion and have submitted the requisite plans to the SBP. PBA has proactively taken up the matters formally with SBP which needs strategic resolution to box those points in sooner rather than later to achieve a smooth transition within the stipulated deadline.

There is no question that there are many economic problems that touch the Pakistani banking industry, and while there is certainly room for improvement on our end, criticism of the industry must take into account the context in which we operate.

The responsibility for reform lies not with banks alone but with policymakers, businesses, and regulators who must foster an environment conducive to financial integration. The taxation system must be expanded equitably, tariff policies restructured to drive competitiveness rather than protectionism, and financial data accessibility frameworks modernized to facilitate responsible lending.

Critically, businesses must also take responsibility by integrating into the formal financial system - documenting themselves, contributing to tax revenues, and building credit histories. Only then can Pakistan break free from its cycle of economic stagnation, unlocking private-sector growth, and enabling its banking sector to function as a true engine of development. n

By Taimoor Hassan

In a country where most businesses still run on paper and trust, digitization is not just a disruption, it’s a rebellion. Receipts are recorded in ledgers, payment cycles stretch into weeks, and cash physically moves from hand to hand in envelopes. In this deeply analog system, Omar bin Ahsan saw not just inefficiency, but an opening.

Today, that opening has turned into a $52 million bet on the future of digital financial infrastructure in Pakistan’s B2B economy. And Haball, the company Omar bin Ahsan founded in 2017, is no longer the under-the-radar platform it once was. It’s the fintech that has successfully risen after keeping steady for years, and survived the funding drydown. It is quietly transforming how businesses move money.

It’s fitting then, that the company’s name, Haball, means “jugular vein” in Arabic. And that’s exactly what it plans to become: a vital conduit in the country’s economic bloodstream.

Unlike the fanfare that often surrounds large funding rounds in the startup world, Haball’s $52 million pre-Series A raise reflects a markedly different approach. It is measured, strategic, and quietly executed over several years.

Since its founding in 2017, Haball has maintained a disciplined fundraising strategy,

resisting the temptation to raise aggressively in favor of a more deliberate and sustainable path. The total raise comprises $5 million in equity and a substantial $47 million in debt financing.

The equity component was led by Zayn VC, a key VC in Pakistan’s early-stage venture capital ecosystem and an early backer of Haball. The round also drew support from Majlis Advisory SPV, several influential private investors from Saudi Arabia, select angel investors, and a notable Pakistani business conglomerate, according to the company.

The lion’s share of the $47 million (off-balance sheet) came from Meezan Bank, Pakistan’s largest Islamic bank, in the form of strategic financing. This component too came in tranches in Haball’s bank account over a few years. Meezan’s backing not only provides capital but also validates Haball’s shariah-compliant operating model, something particularly relevant as the company looks toward expansion in the Gulf.

On the flipside, it also signals that Meezan Bank is now bullish on supply chain financing after the State Bank mandated that the commercial banks either establish their own digital supply chain financing functions or partner with a fintech company to do so.

What sets this round apart is not just the size, but the pacing. Haball raised this capital incrementally over the past few years, with each tranche closely aligned to specific milestones, whether revenue growth, product development, regulatory compliance, or deploying sales teams to onboard clients. The company chose to publicly announce the complete raise only now, signaling that it’s entering a new phase of growth focused on consolidation in Pakistan, and an entry into the GCC. This approach has not only protected

Haball’s cap table by reducing dilution but has also allowed it to build a business that tracks positive unit economics from the very beginning rather than investor burn, focusing more on long-term sustainability rather than short-term hype.

The seriousness seems to have paid off. Haballs now says it has over 8,000 SMEs in its network, and sits at the heart of several major supply chains: pharmaceuticals, FMCG, construction, energy, providing them payments and invoicing, and now lending facility. It counts the likes of Coca Cola among its clientele.

To understand what Haball is doing in the Pakistani market, you need to understand how deeply dysfunctional the average supply chain in Pakistan is. In an economy where even formal businesses often operate within the informal ecosystem, payment cycles are long, inventory is recorded and tracked manually, in memory or handwritten books, and access to formal credit is an unrealized dream for many businesses.

Roughly four to six days is a good guess for the average time it takes for a business-to-business transaction which includes an order, a payment, a credit adjustment to complete. Not because of lack of will, but because of systems that haven’t changed for decades. For both retailers and manufacturers, that delay means lost business and a constant scramble to manage liquidity. For the entire economy, it’s a bottleneck. It’s a systemic problem.

“The supply chain is the head of the

beast,” Omar had told me in an earlier conversation. “If it’s slow, the whole system is slow.”

Before launching Haball, Omar wasn’t pitching VCs or creating apps. He was working with the Federal Board of Revenue (FBR), designing digital tax collection systems. His consulting work led him to the realization that Pakistan’s payment systems were fragmented, monopolized, and entirely unsuited for digitization without a unified layer.

What he envisioned was an agnostic payment platform, one that could integrate with any bank, any distributor, any ERP system, and provide a seamless interface for real-time B2B payment transactions. Not just payments, but a platform that could store catalogs, manage invoicing, offer digital ordering, and eventually unlock financing.

He pitched it. He built it. And then he convinced the most important institution in Pakistan, the SBP to back it in the form of a funding grant in 2019.

Haball’s approach to solving the problems in the supply chain is three-tiered. Through three core revenue streams that collectively power its platform and market position. First, as a payments aggregator, Haball enables seamless, digital payments between manufacturers and SMEs, streamlining the flow of funds across fragmented supply chains. This solution reduces cash handling, improves reconciliation, and drives transparency.

Second, through its digital invoicing service after securing a license from the FBR, the company automates invoice generation and real-time visibility for manufacturers and distributors, addressing long-standing inefficiencies in the B2B invoicing lifecycle. The invoices give the context of the payments by giving details of the transaction such as what inventory was sold and bought.

The data from payments and invoicing eventually gives Haball the ability to lend to businesses and that too in a Shariah-compliant manner. The startup has on its board prominent members from the Islamic finance community.

Finally, Haball’s supply chain financing offering allows SMEs to access working capital by enabling early payments on approved invoices, helping businesses manage liquidity and growth. In both payments and lending, Haball’s primary competition comes from commercial banks, which often lack the agility, SME focus, and shariah-compliant digital infrastructure that Haball provides.

The startup is also in the process to secure a license to become a PISP (payment initiation service provider) via Raast. Haball would be able to initiate digital payments directly from a customer’s bank account. With this license, Haball’s infrastructure becomes more bank-independent, allowing it to com-

pete more aggressively on user experience, flexibility and innovation.

Haball plans to use the funding to deepen its infrastructure across the three aforementioned core areas: payments, invoicing and financing. The goal is to build a financial backbone that supports the businesses making up 60% of Pakistan’s GDP — manufacturers, distributors, and retailers operating in the B2B sector. By streamlining how money and data flow between them, Haball aims to make it easier for these businesses to send invoices, receive payments, and access financing.

Islamic supply chain financing is still in its early stages in the GCC, and Haball sees a major opportunity. With a homegrown, fully Shariah-compliant platform already tested and scaled in Pakistan, the company is well-positioned to meet the growing demand for ethical, interest-free financing options in the region. As Gulf economies push to support their SME sectors, Haball’s technology offers a ready-made solution for businesses looking to digitize payments, streamline invoicing, and access financing that aligns with Islamic principles.

Supply chain financing is not unique to Haball. It has been done before by names such as Finja which couldn’t be successful. On a question why Haball survived and how its survival will continue, the CEO advised to control the expenses, respect the macros and play safe and clean.

There are, however, particular differentiators in Haball’s approach. Firstly, it has spent many years slowly building the infrastructure in the form of payments and invoicing on which financing could be done, instead of getting to lending haphazardly. Secondly, as Omar says, the company has also remained prudent about its finances, raising only and when required, and spending also only and when required.

Thirdly, unlike many fintechs that attempted risky balance-sheet lending, Haball partners directly with regulated banks like Meezan Bank to provide the financing. This gives it access to deep liquidity without taking credit risk on its own books. n

Joint venture between Lucky Cement,

Fertilizer, and Liberty Mills found the new reserves, at a site near other active mining projects

In a remote and arid stretch of Baluchistan’s Chagai district — known to most Pakistanis as the site of the country’s 1998 nuclear tests — something unexpected has emerged from beneath the desert soil. This time, it’s not the detonation of a nuclear device that has captured national attention, but the quiet discovery of significant copper and gold mineralization.

Earlier this month, a joint venture company called National Resource (Pvt) Limited (NRL) — owned equally by Lucky Cement, Fatima Fertilizer, and Liberty Mills — announced that it had struck mineral wealth in a promising greenfield site called Tang Kaur. Located within Chagai, the same geologically rich region that hosts Pakistan’s fabled Reko Diq deposit, the

Tang Kaur discovery could mark the start of a new chapter in Pakistan’s long-stalled resource economy.

With drill holes showing strong mineralized zones up to 148 meters long and copper-equivalent grades of up to 0.56%, the find is still in its early days — but the market has already taken notice.

Chagai’s global fame was cemented in May 1998, when Pakistan conducted its first nuclear tests at the Ras Koh Hills. The tests were symbolic of sovereignty and strength — but the region’s economic potential has always lain in its geology.

For decades, geologists have known that Baluchistan’s Tethyan Belt, stretching from Iran through Pakistan and into Afghanistan, holds some of the richest copper-gold porphyry systems in the world. The massive Reko Diq deposit, now being developed by Barrick Gold, sits within this

belt. But Tang Kaur’s discovery indicates the possibility of multiple satellite deposits that could transform Chagai from a dormant asset into an engine of mineral wealth.

NRL’s exploration license, granted in late 2023, covers an area containing 18 potential prospects. Tang Kaur is the first to show promising results, with 13 drill holes all intersecting significant mineralization.

The company plans to initiate resource drilling shortly. A technical report by an international consultant is expected by year-end, to be followed by a bankable feasibility study over the next three to four years.

The project’s shareholder mix is notable. Lucky Cement, one of Pakistan’s most diversified industrial groups, is leading the charge. Its partner, Fatima Fertilizer, has shown increasing interest in energy and resource sectors. Liberty Mills, a textile powerhouse, brings deep domestic capital. Together, they represent a rare convergence of private sector muscle behind mining — a sector long marred by state-heavy mismanagement and bureaucratic deadlock.

Tang Kaur’s discovery sits just kilometers from the site of one of Pakistan’s most contentious mining sagas — Reko Diq. That deposit, containing an estimated 50 million ounces of gold and 10 billion pounds of copper, has been at the heart of a two-decade legal battle between the Government of Pakistan and international mining giants.

The original contract was terminated in 2011, leading to an arbitration case and a massive $6 billion penalty imposed on Pakistan by the World Bank’s ICSID tribunal. A recent settlement allowed Barrick Gold to resume development under a revised structure — but scars remain.

Even now, concerns about transparency, local equity, and environmental protections continue to dog the conversation around mining in Baluchistan. Indigenous Baloch communities remain skeptical, often citing the region’s past experiences with exploitation and neglect.

Against this backdrop, NRL's announcement is being watched closely. While the company has signed an MoU with OGDC for joint exploration and is working with the Government of Baluchistan and the SIFC to secure additional licenses, it faces the same set of political, social, and environmental challenges that have tripped up giants before it.

What makes this discovery particularly timely is the global context.

Copper, often dubbed “the new oil,” is a critical mineral in the clean energy transition. It is indispensable in electric vehicles, wind turbines, solar panels, and power transmission. And as the world races toward electrification, demand is set to surge.

According to S&P Global, the world will need to double its copper production by 2035 to meet energy transition targets. Yet few new large-scale mines are coming online — constrained by years of underinvestment, permitting delays, and rising costs.

This has led to a quiet global scramble for copper. With large deposits mostly tied up in Latin America, Africa, and a few parts of Asia, countries like Pakistan are suddenly back on the map — not just for their potential, but because the world is running out of alternatives.

The copper-gold intersection adds another layer of value. Gold provides a financial buffer against volatility, making copper-gold deposits more attractive to investors. As countries seek to “friend-shore” or “de-risk” critical mineral supply chains, countries like Pakistan — with a favorable geological footprint and a need for foreign capital — find themselves at a potential inflection point.

If developed prudently, Tang Kaur — and others like it — could form the backbone of a new export revenue stream for Pakistan, long tethered to textiles, remittances, and commodity imports.

Reko Diq alone is projected to contribute $10 billion in annual export earnings at peak production. Even if Tang Kaur turns out to be just a fraction of that, it would still represent a transformational opportunity — especially for a country struggling with chronic current account deficits and a narrow export base.

Moreover, a functioning mining sector could create a cascading impact: from infra-

structure development and job creation, to local supply chain formation and technology transfer. And with Pakistan’s Special Investment Facilitation Council (SIFC) now actively courting global capital into mining, there appears to be both political alignment and institutional will to support it.

Despite the optimism, NRL’s discovery remains early-stage. Feasibility, financing, logistics, and social license are all unresolved. The terrain is difficult. Water is scarce. Power supply is unreliable. Community consent cannot be assumed.

Past experiences in Baluchistan suggest that resource nationalism, legal ambiguity, and mistrust can quickly derail even the most promising ventures. And given Pakistan’s macroeconomic fragility, investors will demand stability before committing billions.

Yet, for perhaps the first time in years, the story isn’t about what could have been lost — but what could still be built.

From nuclear legacy to mineral future, Chagai now stands at a strange intersection of symbolism and opportunity. The very mountains that once echoed with atomic defiance may soon reverberate with the hum of drilling rigs and the clatter of ore trucks.

Tang Kaur may not yet be a national treasure. But it is a signal — that Pakistan’s subsurface still holds promise, and that the world might finally be ready to listen.

The ground, once again, is speaking. The question is whether we are ready to hear — and act. n

The company announced that it will be entering the market, but did not specify which models or provide any timelines as to when

In a move that appeared designed more to appease shareholders than to chart a serious course for the future, Honda Atlas Cars (Pakistan) Ltd has announced its intention to launch a hybrid electric vehicle (HEV) in the Pakistani market. But while the April 11 notice sent to shareholders marks the company’s first formal acknowledgment of plans to enter the hybrid space, the announcement lacked substance — omitting critical details such as the model name, production timelines, or rollout strategy.

At a time when Pakistan’s automotive sector is undergoing a tectonic shift toward electrification, Honda’s belated and vague declaration has left industry watchers and investors underwhelmed. Some see it as an effort to catch up with competitors already capitalizing on the hybrid and electric vehicle transformation. Others are questioning whether the company’s leadership fully grasps the pace and scale of disruption taking place in the domestic market.

The global transition to hybrid and elec-

tric vehicles is not a new phenomenon. Toyota, Hyundai, Kia, and even Chinese entrants like MG and BYD have been recalibrating their product offerings around cleaner, more fuel-efficient technologies for years. In Pakistan, this transition has accelerated since 2022, driven by regulatory reform, growing consumer awareness, and persistent macroeconomic stress tied to fuel imports and inflation.

Despite being part of a global automotive group that has launched several acclaimed HEV and EV models overseas — including the Honda Insight, Accord Hybrid, and the CR-V Hybrid — Honda Atlas has long clung to internal combustion engine (ICE) technology in Pakistan. The company's local lineup continues to revolve around the City and Civic sedans, which have seen few fundamental updates beyond cosmetic facelifts in recent years. Even as competitors embraced innovation, Honda remained rigid.

This inertia is striking when contrasted with other market players that have already delivered on the hybrid or electric promise:

• Toyota Indus Motor Company launched its first locally assembled HEV — the Corolla

Cross Hybrid — in December 2023.

• Sazgar Engineering Works Ltd, in partnership with Great Wall Motors, introduced the Haval H6 HEV in November 2022 and followed it with the all-electric ORA 03 in early 2024.

• MG Motors Pakistan released its locally assembled HS Plug-in Hybrid Electric Vehicle in late 2024, offering a viable urban alternative with an electric range of over 50 kilometers.

• Regal Automobiles launched the Seres 3 Electric SUV, Pakistan’s first locally assembled electric SUV, in October 2024.

• BYD, in partnership with Mega Motors, has announced the launch of three EV models and is building a local assembly facility in Karachi, expected to go live by 2026. By contrast, Honda Atlas is only now making its first real acknowledgment of hybrids — and that too without specifics. No models were named. No deadlines were set. No assembly plant upgrades were announced. The announcement lacked even a basic roadmap, let alone a tangible product reveal.

Honda Atlas has managed to retain the number three position in Pakistan’s car mar-

ket, trailing Pak Suzuki and Toyota Indus. In 2024, the company recorded 15,413 new vehicle registrations — a 44.6% increase year-onyear — capturing approximately 12.4% of the market. While these figures suggest resilience, they obscure deeper structural issues. Honda’s growth has come in a highly contracted market and has largely depended on legacy ICE models.

Meanwhile, Suzuki continues to dominate the lower-cost segments with over 64,000 vehicles sold, and Toyota remains strong in the mid-range and utility markets with over 26,000 units moved. Honda’s core products — Civic, City, BR-V, and HR-V — have benefited from short-term pricing tweaks and demand rebounds, but they are increasingly misaligned with the country’s shifting automotive landscape.

Notably, Honda’s SUV models accounted for 21% of its total sales in 2024, the highest in three years. Yet even this gain came without hybrid or electric variants — a glaring omission in a segment that is rapidly going green both globally and locally.

While competitors like Toyota and Sazgar were busy retooling their assembly lines and developing local supply chains for hybrid production, Honda Atlas stood still. This complacency is even more baffling given Honda's strong global hybrid portfolio. In markets like the United States and Europe, Honda has aggressively promoted hybrid versions of its most popular vehicles — from the Accord to the CR-V and even the Fit. Yet, none of these have made their way to Pakistani showrooms.

This absence is not due to technical limitations. Honda already has the engineering, the R&D, and the global production capacity. What it lacks in Pakistan is apparent: a sense of urgency and strategic clarity.

There have been no efforts to localize parts for hybrid production. No supplier integration has been attempted. No announcements have been made regarding partnerships with charging infrastructure providers. Even the basic logistics of training after-sales staff or introducing EV financing schemes have yet to appear on Honda Atlas’ agenda.

The April 11 notice, with its vague language and opaque intent, seems crafted more to quell rising investor impatience than to signal any true pivot. It arrived just days after other carmakers in Pakistan reported major milestones in EV or hybrid integration, and it offers no evidence that Honda is truly ready to make the leap.

The company's past behavior supports this skeptical view. In its financial disclosures, Honda Atlas has consistently cited "unfavorable economic conditions" and "high cost of localization" as reasons for delaying innovation. But competitors operating under the same

macroeconomic pressures have managed to deliver results. Toyota, for instance, didn’t just introduce the Corolla Cross Hybrid — it did so as a locally assembled model, helping reduce cost and increase adoption.

Honda’s announcement looks particularly thin when contrasted with BYD's bold entry strategy. Not only is BYD launching three models, including the Atto 3 and Seal, but it is also committing to local manufacturing by 2026 and building a fast-charging network in major cities.

Meanwhile, Honda is offering shareholders a press release with no tangible commitment.

The most significant impact of Honda’s inertia is being felt by consumers. As fuel prices continue to rise and urban congestion worsens, demand for fuel-efficient, eco-friendly vehicles is growing. Consumers looking for hybrid options in the mid-size and crossover segments — traditionally Honda’s strength — are now being pushed toward Toyota’s Corolla Cross or Sazgar’s Haval H6.

Honda loyalists in Pakistan, many of whom have stuck with the Civic or City for decades, are now being forced to reconsider their brand allegiance. The automotive sector’s pivot to hybrid and electric is not just a niche trend; it’s fast becoming the mainstream. And yet, Honda seems to believe that a vague promise, lacking substance or specifics, is sufficient to hold on to a customer base that is already exploring alternatives.

Pakistan’s automotive policy, as well as broader environmental goals, make it clear that the future is electric. The government has

already set ambitious targets for EV adoption and has introduced incentives for local manufacturing. Hybrid vehicles serve as a natural bridge in this transition — offering fuel savings and emissions reductions without relying on charging infrastructure that is still under development.

Honda had the perfect opportunity to lead this middle path. Instead, it has ceded ground to competitors who have not only seized the initiative but are now shaping consumer expectations. The longer Honda waits to bring a real product to market, the harder it will be to gain relevance in a rapidly transforming industry.

The April 11 announcement by Honda Atlas should be seen for what it is: not a strategic milestone, but a warning sign. It reveals a company increasingly out of sync with market dynamics, consumer demand, and competitive pressure.

Rather than rally confidence, the statement has deepened skepticism. Without a clear timeline, defined model rollout, or investment in infrastructure, Honda’s vague nod to the future feels more like a rear-view glance — one that may soon become a memory in a market racing ahead.

Unless Honda follows this announcement with swift, concrete action — including plant upgrades, local supplier partnerships, and a public-facing product launch — the company risks relegating itself to irrelevance in an era where innovation is the only currency that matters.

For now, Pakistan waits. But it may not wait for long. n

A week after the acquirer announced it was backing out, Engro clarifies what happened: Liberty got cold feet

ust one day before a landmark acquisition was set to close, Liberty Power Holdings Ltd abruptly pulled out of its agreement to acquire a controlling stake in Engro Powergen Qadirpur Ltd (EPQL), citing a "material breach" by Engro Energy Ltd (EEL). The deal's unraveling sent shockwaves through Pakistan’s energy and financial sectors, with many observers calling Liberty’s move a case of buyer’s remorse dressed up in legalese. The decision, made public on April 3, blindsided market watchers. Liberty declined to disclose the nature of the alleged breach at the time. Only days later, on April 7, did Engro break its silence — and what it revealed raised more questions about Liberty’s motives than Engro’s actions. According to a detailed disclosure

filed with the Pakistan Stock Exchange (PSX), Liberty’s claim of breach hinged on Engro Powergen Qadirpur’s participation in the government-mandated renegotiation of Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) — a national effort to overhaul the terms of contracts between Independent Power Producers (IPPs) and the government to reduce energy costs and stem ballooning circular debt.

Engro made it clear that EPQL’s renegotiation was both lawful and necessary, carried out in alignment with government directives and in the public interest. In a letter dated April 5 and shared with the PSX, EEL CEO Athar Abrar Khwaja wrote:

“The alleged material breach — that EPQL entered into Amendment Agreement with the Government of Pakistan and CPPA-G in self-interest — is baseless and unfounded. This agreement was executed in the larger national interest.”

Engro also pointed out what many energy sector insiders are calling the most damning inconsistency in Liberty’s claim: Liberty itself was a party to similar renegotiated contracts under the same 2002 power policy framework.

The Pakistani energy sector has been undergoing a massive contractual reset over the past year in response to the country’s unsustainable circular debt, which had ballooned to more than RS2.7 trillion by mid-2024. The government, seeking to prevent further economic deterioration and fulfill its obligations under an IMF program, initiated a renegotiation of contracts with IPPs — including those established under the 1994 and 2002 power policies.

The terms of these renegotiated agreements have aimed to eliminate idle capacity payments by shifting from “take-or-pay” to “take-and-pay” models, wherein the government pays only for electricity actually consumed, eliminating idle capacity payments.

There were also other changes, including adjustments to operational and maintenance cost indexation formulas, rebasing of working capital costs, and the introduction of partial rupee-based returns instead of full dollar-denominated profits.

These changes were not optional for IPPs. They were part of a broad-based initiative negotiated transparently with the government, under regulatory and public scrutiny.

The process started in October 2024: The government terminated Power Purchase Agreements with five IPPs, including Hub Power and Lalpir, citing excessive costs and renegotiated settlement figures totaling Rs411 billion in savings.

In November 2024, eight more IPPs agreed to new terms under renegotiated contracts, while other companies began transitioning to the new payment model. In

December 2024, the government claimed to have saved over Rs1 trillion through the renegotiation process, with further changes under consideration.

In March 2025, seven IPPs, including some under Liberty’s umbrella, formally submitted new tariff structures aligned with revised agreements — directly undercutting Liberty’s later objections to Engro’s similar moves. And then this month, Liberty Power unilaterally terminated its acquisition of EPQL, citing Engro’s contract amendments as a “material breach.”

The merger had been agreed to on December 3, 2024. Liberty Power, acting in concert with other entities, announced its intention to acquire 68.89% of EPQL from Engro Energy Ltd.

On April 3, 2025, Liberty withdrew its public announcement of intention, citing an unspecified material breach by Engro. Two days later, on April 5, 2025, Engro rejected the allegations and noted Liberty’s failure to fulfill joint conditions precedent by the longstop date (April 4, 2025). Engro, therefore, exercised its contractual right to terminate the Share Purchase Agreement with immediate effect.

Then, on April 7, 2025, Engro publicly disclosed that Liberty’s stated reason for withdrawal was EPQL’s participation in the national PPA renegotiation process — the same process Liberty was itself involved in.

The matter may not end here. Engro’s

rejection of Liberty’s claims and its assertion of contractual rights suggest that legal action could follow.

While Engro has officially exercised its own termination rights due to Liberty’s failure to meet conditions precedent by the agreed deadline, it has also reserved the right to pursue remedies under the Share Purchase Agreement. If pursued, damages could be significant — not only for breach of contract, but potentially also for reputational harm and loss of shareholder value.

This corporate drama comes at a time when Pakistan’s power sector is in a fragile but critical transformation. With energy prices previously among the highest in the region and capacity payments draining public coffers, the government's renegotiation strategy has been viewed by international observers as necessary and bold.

Engro, for its part, has carried itself with characteristic corporate discipline and transparency. Its public disclosures have been timely and detailed, while its conduct throughout the renegotiation and transaction process has been aligned with national and shareholder interests.

In contrast, Liberty’s abrupt and ambiguous withdrawal — coupled with its contradictory behavior — has left many questioning whether the company was ever truly committed to the acquisition or simply looking for a way out once the sector’s economics grew tougher. n

Pakistanis’ recent visa denials have meant that more of them are looking for work at home, which has been a boost to the tech giant’s bottom line

When opportunity knocks, it does not always come in the form of open borders. For Systems Ltd — Pakistan’s largest and most successful IT exporter — the gate to profitability in 2024 did not swing open on new foreign markets or a tech breakthrough. It swung closed — on Pakistani professionals trying to leave the country.

In a corporate briefing held on April 10, Systems Ltd talked about a counterintuitive edge it has gained in a global economy plagued by slowdowns and restrictions: Pakistanis’ restricted access to foreign work visas. While this development has left thousands of skilled professionals frustrated and grounded, for Systems, it has created a captive pool of tech talent — available, affordable, and increasingly necessary for scaling its global delivery operations.

The company’s message to investors was understated, but the subtext was clear. At a

time when many Pakistanis can no longer leave the country to find work abroad, Systems Ltd has positioned itself as the best — and in some cases only — local alternative. In a country where “getting out” has long been synonymous with success, Systems is now betting that “staying in” can be just as lucrative.

According to company disclosures, Systems Ltd employs over 82% of its workforce in Pakistan. And 2024 presented a turning point. As visa restrictions tightened in markets like the Gulf, Europe, and North America, outbound mobility of skilled tech workers — already expensive and bureaucratically limited — slowed dramatically.

Throughout much of 2022 and 2023, Systems struggled with retention, as talent drained out of Pakistan seeking better pay, global exposure, or simply economic stability. The company responded with aggressive salary hikes, including a 20% average pay increase for employees at the start of 2024, designed to hold the line against inflation and stop attrition.

But by mid-year, external conditions started to do the job for them. With visa re-

gimes becoming more selective and outbound employment pipelines for Pakistani IT workers stalling, Systems suddenly had access to a more stable, immobile workforce. The company did not just benefit passively — it capitalized. That windfall of stuck-at-home tech labor translated directly into operational stability.

Despite margin pressures, 2024 was a year of operational expansion for Systems. The company reported a 27% increase in USD-denominated revenue, reaching $242.35 million — its highest-ever topline. Gross and operating profits also hit record levels in local currency terms.

However, net profit fell to RS7.46 billion (USD $26.8 million), down 14% year-on-year, primarily due to the Pakistani rupee’s unexpected appreciation. Unlike 2023, when Systems enjoyed an $8 million foreign exchange gain, 2024 saw a loss of nearly $1 million due to currency headwinds.

Still, the core of the business remains robust. With 94% of revenue derived from foreign clients and a significant portion of expenses (57%) paid in rupees, the underlying

economics of Systems’ model remain attractive. The company’s gross margin profile, while pressured, is still well above local industry norms — a reflection of its ability to scale efficiently.

Notably, Systems added 14 new enterprise clients in 2024, bringing its active client count to 250. Its largest client alone now contributes over $25 million annually — a milestone for a company that has steadily moved away from project-based billing to long-term recurring revenues.

The idea of Pakistan becoming a global outsourcing hub has long been more aspiration than reality. But Systems Ltd might be the country’s best shot yet.

The company’s cost structure is its most potent weapon. With a delivery model rooted in low-cost, high-skill labor, Systems has remained attractive to global clients even as wages have risen. The visa restrictions add a new layer of competitiveness: tech workers who can’t go abroad are now finding career growth — and decent pay — at home.

For decades, the “brain drain” was Pakistan’s most predictable export trend. Doctors, engineers, coders — all trained locally, all hired globally. That narrative hasn’t ended, but it’s now disrupted. With governments tightening immigration across the board, companies like Systems offer a Plan B that did not exist a few years ago.

This shift carries profound implications. For one, it keeps talent inside the domestic economy, circulating wealth, skills, and income locally. More broadly, it may alter the very trajectory of the Pakistani tech industry. If the best graduates of top-tier universities like NUST, FAST, and LUMS start viewing local tech firms as career destinations — not stepping stones — the country could build a deep, sustainable bench of software talent.

Of course, there is an ethical complexity to profiting from geopolitical roadblocks. Systems didn’t lobby for stricter visa policies; it simply adapted to the environment. But in doing so, it reveals a larger truth about the modern global labor economy: mobility is no longer a guaranteed asset — and immobility, in some cases, can be monetized.

While this may sound cynical, Systems is arguably doing something constructive. It is creating high-skilled jobs within Pakistan that meet global standards. It is absorbing talent that might otherwise be idle or underemployed. It is becoming, in the absence of open borders, a domestic proxy for the global tech dream.

That said, Systems cannot afford complacency. Salaries are rising, and global clients expect world-class outcomes. The company must now prove that its productivity, not just its price, justifies its positioning in the interna-

tional outsourcing marketplace.

While the bulk of Systems’ human resources remain based in Pakistan, the company has quietly expanded its delivery footprint into newer geographies. Egypt, once a minuscule part of its HR map, now accounts for over 3% of its workforce — up from just 0.55% in 2022. Offices in the UAE, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia account for another 15%.

Saudi Arabia, in particular, is a key growth market. As Riyadh pushes ahead with Vision 2030 and reforms aimed at tech modernization, Systems is positioning itself as a preferred partner for IT and business transformation. The lower cost of Pakistani labor — now accessible even more due to travel restrictions — makes the value proposition even more compelling.

By exporting services while importing capital and job creation, Systems is performing a national service, even if unintentionally. In an economy battered by inflation, political instability, and debt, the company’s success story is one of the few bright spots.

Systems’ management has shifted its strategic focus from chasing rupee depreciation (as it did in past years) to operational

efficiency. It is a prudent pivot. Betting on currency swings is a dangerous game. Investing in automation, client growth, and workforce retention is far more sustainable.

The company has guided for 20–30% growth in IT exports over the coming years, driven by new enterprise accounts and deepening relationships with top clients. It has also reaffirmed its commitment to organic growth — a reassuring sign in a sector often distracted by high-risk acquisitions.

But the real test lies in whether Systems can convert its temporary labor advantage into long-term institutional strength. Visa restrictions may ease. The global economy may rebound. The best talent may once again seek opportunities abroad. When that happens, will Systems be compelling enough to keep them home by choice?