15 minute read

ROUTE 61 / TENNESSEE

NATCHEZ | MEMPHIS | TENNESSEE GREAT RIVER ROAD

Mississippi’s stretch of Route 61 runs 300 miles from Natchez in the south to Memphis, Tennessee in the north. For much of the journey it travels in parallel with the mighty, muddy waters of the Mississippi River, passing through fields of cotton, the homelands of the Delta blues, and quintessential small towns of the Deep South that are home to “more characters than you’ll find on Sesame Street.”

Advertisement

WORDS AND PHOTOS BY SIMON URWIN

This was once considered America’s version of Sodom - the rowdiest and most dangerous spot on the Mississippi River”, says Natchez local John Dicks. “Mark Twain passed through here in the mid-1800s, during his days as a steamboat pilot. He described it as a place with “plenty of drinking, fisticuffing and killing among the riff-raff.” Clearly, it was the fun bit of town!”

I go to buy us a round of drinks at the bar of the historic Under-The-Hill Saloon, a place once frequented by cutthroats, gamblers, prostitutes and thieves. “Natchez Under-The-Hill was a thriving port back then”, says Dicks, as we sit sipping our bottles of beer. “Cotton was loaded here onto paddleboats then taken north to the textile mills for processing. Cotton was king back then and you had a town of two halves - the rough and tumble of port life down here, and the hoity-toity people up on the bluff. That’s where all the wealthy cotton barons had their town houses.”

I climb the hill for a closer look at the more genteel side of Natchez, where more than 500 antebellum mansions still grace the city streets, each one as ornate as a wedding cake. Here, Southern belles would promenade in their crinoline skirts on their way to opera soirées, while out

John Dicks takes it easy with a Bud at Under-The-Hill saloon in Natchez.

CHARLIE PATTON WORKED AT DOCKERY FOR THREE DECADES, SAYS DEAK HARP, A WORLD-FAMOUS HARMONICA PLAYER. “HE WAS ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT EARLY DELTA BLUES MUSICIANS. HE INFLUENCED

ALL KINDS OF FIGURES SUCH AS HOWLIN’ WOLF AND ROBERT JOHNSON.

on the cotton plantations, their men folk were amassing great fortunes on the backs of the enslaved and brutalised workforce.

“It’s hard to imagine it in this itty-bitty town, but back in those days Natchez had more millionaires than anyplace else in the USA”, says Dub Rogers as he wrestles a slick new espresso machine through the door of his coffee and cigar emporium, Papi y Papi. “It was not only the commercial capital of the old South, but the cultural capital too. The French originally founded it in 1716, then the British and Spanish came, so you’ve always had a European sensibility here.”

He invites me to see his humidor, packed from floor to ceiling with fine cigars in varnished cedar wood boxes. “There’s a sophistication here and an appreciation of luxury”, he says. “I’d describe it as an art culture. Not a counter-culture compared to other places in the world, just counter the culture of most of the rest of the state. A lot of that comes from our European roots, but it also comes from the river. You have this powerful force flowing through – bringing new people, new ideas. It has a special energy that creates a different way of thinking. As an example, in Natchez we have a popular mayor who is gay and black. He organises an annual drag race here to promote inclusivity. It’s called “Y’all Means Y’all.” Imagine that. In Mississippi of all places!”

I leave Natchez the next morning and head north, taking a short detour off the 61 to visit Rodney – a town that at one time in the eighteenth century came close to being crowned capital of the Mississippi Territory. In place of a cluster of grand civic buildings though, I find a desolate ghost town suffocated by knotweed and populated by a few deer hunters who have set up home in an abandoned railway carriage, others in a trailer on stilts. Two men walk towards my car bearing rifles, eyeing me suspiciously. I wind down the window. We chat awhile and they tell me that Rodney fell into ruin after the river changed direction and drifted away west. “The Mississippi River is a lady. She’s allowed to change her mind and go where she likes. This is what happens when she leaves you though”, they say, before heading off into the woods, looking for a kill.

DELTA BLUES I continue my journey, driving parallel with the river, which carves its way across the state in a restless, drunken meander. I reach Vicksburg, where proud granite memorials dominate the town. Here, in 1863, the Confederate army surrendered after a six-week siege that saw 10,000 men killed on both sides. It was a critical victory, allowing Union forces to take control of the river, hastening the end of the Civil War.

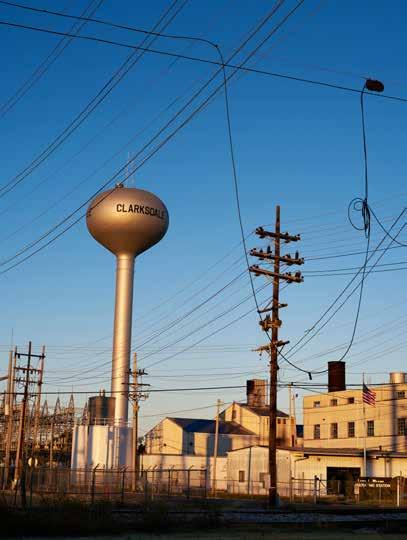

Battle-scarred Vicksburg also marks the southernmost point of the Mississippi Delta region, one of the most fertile floodplains on earth. It stretches 200 miles north, all the way to Memphis, and covers over four million acres. The Delta’s rich soils still produce vast snowy expanses of cotton, but their greatest legacy is that of music, for in the plantation fields of Dockery Farms, just south of Clarksdale, Delta blues was born.

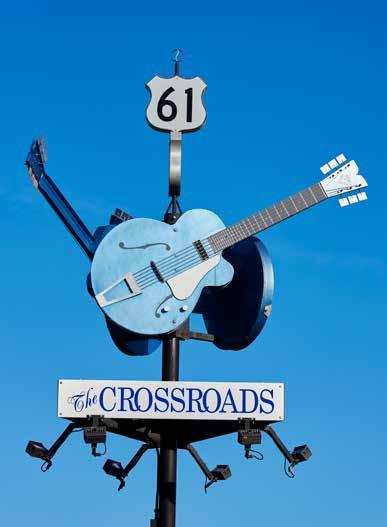

“Charlie Patton worked at Dockery for three decades”, says Deak Harp, a world-famous harmonica player. “He was one of the most important early Delta blues musicians. He influenced all kinds of figures such as Howlin’ Wolf and Robert Johnson. Robert Johnson wrote the iconic “Cross Road Blues”, one of the greatest blues tunes of all time. Legend has it that he sold his soul to the devil at the junction of highways 49 and 61 in Clarksdale in return for becoming a guitar virtuoso”, he says. “In Clarksdale, you either sell your soul or you find it. And luckily, I found mine here”, he says. “They say I got the best harmonica tone in the business. Well that’s ‘cause I learned from the best - James Cotton who played with

Deak Harp, a harmonica player from Clarksdale.

The Crossroads - where Highways 61 and 49 meet in Clarksdale.

The powerful and historically important Mississippi River slowly meanders through Vicksburg.

Cotton fields in full bloom right outside of Clarksdale.

A Chevy 3100 pickup stands outside Shack Up Inn, Clarksdale. We are guessing it’s a 1953.

Greg Mitchell, one of the owners at St. Blues, where guitars are still made by hand.

Robert Fisher at St. Blues, right outside of Memphis, doesn’t know whether to laugh or cry when showing off his latest creation.

FOR FISHER, KEY TO A GREAT GUITAR IS CHOOSING THE CORRECT WOOD. “DIFFERENT WOODS HAVE DIFFERENT SOUNDS”, HE EXPLAINS. “ROSEWOODS GIVE YOU YOUR BASS, MAHOGANIES ARE FOR YOUR MID TONES, AND MAPLES ARE WHAT WE USE FOR HIGH FREQUENCIES.

Muddy Waters. He learned from Little Walter, who’s a prodigy of Sonny Boy Williamson. So I’m third generation down from Sonny Boy, a harmonica legend.”

Harp stops to play a burst of blues, the notes rippling from his lips with a powerful vibrato. “It took a while for my embouchure to develop - that’s the way you shape your mouth to create a note. Nowadays, anyone can recognise my music though if they know the blues. My sound is big - like when you hear a train whistle and it hits you in the chest”, he says.

“When you play, it’s not just about technique though. You gotta let your soul and your emotions pass through the instrument – you have to literally get inside it, to inhabit it. I customise my own instruments so it makes it easier to get the notes that I want, and that’s important because the harmonica is such an integral part of the blues. In the wrong hands the sound can hurt like hell. But if you’re good, it’ll take you places no other music can.”

RAMON'S DINER I take a break for lunch in Ramon’s diner, a Clarksdale institution, where I find the Christmas decorations are still up on a hot and humid autumn day. “Oh that’s ‘cause they’re pretty. And besides, I can’t be bothered to take ‘em down”, says owner Beverly Ely with a laugh.

I ask her how long’s she’s had the place. “I bought it in 1967, so that’s 53 years”, she says, inviting me to sit in an empty booth. “There’s nobody in Clarksdale who didn’t eat here at some point in their lives. Folk have come here to date, to reunite and to celebrate. And I’ve played a part in all of these significant moments of their lives.”

She heads off to the kitchen to prepare me a dish. “It’s gotta be fried, you’re in the Deep South!” she cries, returning shortly afterwards with a plate of Gulf Coast prawns. In the background the jukebox flips from “Love Me Tender” to “Hound Dog”. “I saw Elvis Presley before he got famous you know?” she says. “Some guys brought him to Clarksdale and he played at the auditorium. Me and all the girls in the crowd were hollerin’ like crazy, even though we didn’t really know who he was. I saw him a couple of times in Memphis afterwards too, when he had the white rhinestone suit with the cape. I still have the photographs. They were happy days.”

MORE CHARACTERS THAN YOU’LL FIND ON SESAME STREET. Come nightfall, I stop for a beer at Messenger’s pool hall, the first place to get a liquor license in Clarksdale at the turn of the century. Inside, the clientele are drinking as if Prohibition has only just ended – slurring and laughing uproariously, some barely able to stand upright. “We get more characters in here than you’ll find on Sesame Street. Some real wild ones”, says Sherman Robinson, the owner. “There may be a lot of churches in Mississippi, but there’s also plenty of bad behaviour if you know what I mean. But that’s just life, ain’t it?”

Robinson tells me that running the bar often feels more like being a priest in the confession booth. “People come with their happiness and their sadness. Put a beer in ‘em, they gonna tell you they business. Some have hit bad luck and they might be short of a few dollars – so you lend them some money, or give them drinks for free. And that’s where you get your blessings in life, because it could be you. It’s easy for the shoe to be on the other foot”, he says. “Besides, helping folks is just the way we do things around here.”

Late at night I head for Red’s Lounge, a juke joint in the old Levine’s music store, where Ike Turner and his Kings of Rhythm bought the instruments that were played on the first ever rock ‘n’ roll record, “Rocket 88”. In between sets I get chatting with a blues fan who’s travelled all the way from Texas. “It has a gritty, edgy honesty about it, doesn’t it?” he says. “When you think back to the time

Master Distiller Alex Castle knows that empty barrels rattle the most. Nothing to worry about here at Dominick’s Distillery in Memphis.

that blues was born, you had all these exploited plantation workers, living lives of hardship. So when they sat down to play at the end of the week, with the moonshine flowing, well, you weren’t going to end up with cream puff music were you? You were going to end up with music that punches you in the gut and rips your heart out.”

BESPOKEN GUITARS Next morning I set off on the final stretch of my journey. Along the roadside eerie cypress swamps soon give way to the prim green lawns of Baptist churches with their signs screaming “Repent!” and “The End is Nigh”. On the distant outskirts of downtown Memphis, I pull up outside St. Blues, considered one of the finest guitar workshops in the country. “We’re a one-at-a-time bespoke guitar maker”, says luthier Robert Fisher, as he lovingly sands the neck of a newly commissioned instrument. “Each one normally takes three to four months to complete and will cost between $2,000 and $3,000. That gets you a very special guitar, as special as they come. At that point, we’ve pretty much run out of things to do to it - unless you want to rubies on it!”

For Fisher, key to a great guitar is choosing the correct wood. “Different woods have different sounds”, he explains. “Rosewoods give you your bass, mahoganies are for your mid tones, and maples are what we use for high frequencies. If a guitarist wants a dark and dirty sound, or they want a bright, shrill tone that cuts through sharp-asa-knife, we just find the right recipe. I pick all the wood myself that we keep in stock, and a specific piece will speak to me when the time is right. It might sit on the shelf for 10 years and then, suddenly, along comes the right job where you can use the wood, shape it, let it sing, and create a sound that’s magical.”

While Fisher looks after building the main body of the guitar, his partner Greg Mitchell looks after the electronics and the final set-up. “I find the creative process thrilling”, he says. “Basically you take a tree and then you make a guitar and with that guitar you can create music that not only can cause a huge cultural shift, but can model an entire generation and change their lives”, he says. “It’s incredible.”

“And what’s so exciting is that we’re at the tail end of this amazing history of music in the region”, says Fisher.

Cool guy Dub Rogers at his coffee and cigar emporium, Papi y Papi in Natchez.

Beverly Ely has run this locals’ pub, Ramon’s, in Clarksdale since 1967.

IT’S A GRITTY PLACE, A DRINKING CITY THAT LOVES NEW THINGS – AND THE LOCALS LOVE THOSE NEW THINGS TO SUCCEED. A LOT OF THE

CHARACTER OF THE PLACE IS DOWN TO THE RIVER I THINK. HISTORICALLY, YOU’VE HAD SO MANY PEOPLE PASSING THROUGH OR SETTLING

HERE – BRINGING THEIR DIFFERENT CHARACTERS AND CULTURES FROM

ELSEWHERE, AND THE CITY JUST EMBRACES THEM, CELEBRATES THEM.

“And in a way you’ve followed that trail all the way here. I’ll explain. Time for the quickest history lesson ever!” he says, excitedly. “You have slavery on the cotton plantations in the south. There are slave songs. The Civil War happens, the Unionists win and then slavery is over. Hurrah! When the slaves are set free they make their own instruments: one stringed instruments and a drum of some kind. Then throw in their church songs. You got the blues! But what if you’ve got music that people want to hear? Where are you going to make money? You go to the juke joints in Clarksdale, then you come to Beale Street in Memphis where lots of artists get their big break.”

Fisher pauses to take a breath. “Come the 50s, racial segregation is in full force. Black music is more popular than white music but you can’t sell black music to white people – so what do you do? You find a white guy that’s just as poor as the black people are, who’s lived among them and learned their songs. You bring him here, to Memphis, and you make him look real pretty and he’s called Elvis Presley. And the rest is music history.”

FEELING YOUNG AT OLD DOMINICK’S DISTILLERY That afternoon I reach journey’s end at the banks of the Mississippi River where, in a darkening sky, the neon lights of the Old Dominick’s Distillery are slowly flickering into life. “Old Dominick’s has deep roots in Memphis, says Alex Castle, the company’s master distiller, as she invites me into their elegant tasting room. “It’s one of the symbols of the city – like Sun Studios, Beale Street or the Peabody Hotel. They’re pillars, holding the place up”, she says.

At the bar, she leads me through the portfolio of spirits, including classics such as a high rye bourbon and a straight-up whiskey, then some more unconventional offerings such as a vodka infused with tangelo, a hybrid of a tangerine and a pomelo. “We cherish traditions here, but we’re not afraid to take things in a different direction”, she says. “For example, we’ve recently been working with some of the breweries in town. We gave them a used bourbon barrel – they then put beer in it – we took that barrel back and put bourbon in it again. The end result is a beer barrel-finished bourbon that tastes like oatmeal raisin cookies. It turned out great.”

I ask Castle where she finds her inspiration. “Being in Memphis has a big impact on me”, she says. “It’s a gritty place, a drinking city that loves new things – and the locals love those new things to succeed. A lot of the character of the place is down to the river I think. Historically, you’ve had so many people passing through or settling here – bringing their different characters and cultures from elsewhere, and the city just embraces them, celebrates them. Whether it’s writers or musicians or craftsmen or entrepreneurs, we all feed off this incredible energy – the energy of the Mississippi River.”