8 minute read

PIGS EAR SANDWICH / MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE

BITE OF THEBIG APPLE

JACKSON | MISSISSIPPI

Advertisement

Located in a rundown neighbourhood of Jackson, Mississippi, the Big Apple Inn is a much-loved fixture of the city’s food scene - renowned for a Southern delicacy that’s been on the menu since it first opened its doors over 80 years ago: the pig ear sandwich.

WORDS AND PHOTOS BY SIMON URWIN

Behind the unpresuming facade on Farish Street, hides one the most classic food joints in Memphis.

NWalking past the rows of abandoned buildings and derelict storefronts on Farish Street, it’s hard to imagine that this was once a prosperous and wildly popular place - the equivalent of Beale Street in Memphis or Bourbon Street in New Orleans.

There are no crowds of revellers anymore though; no music spilling out onto the streets; no dancing until dawn. The juke joints and nightclubs all fell silent in the 70s, the bars and diners followed suit soon afterwards. Amongst all the urban blight however, an historic soul food joint has weathered the storm and remains the beating heart of this once-vibrant community: the iconic Big Apple Inn.

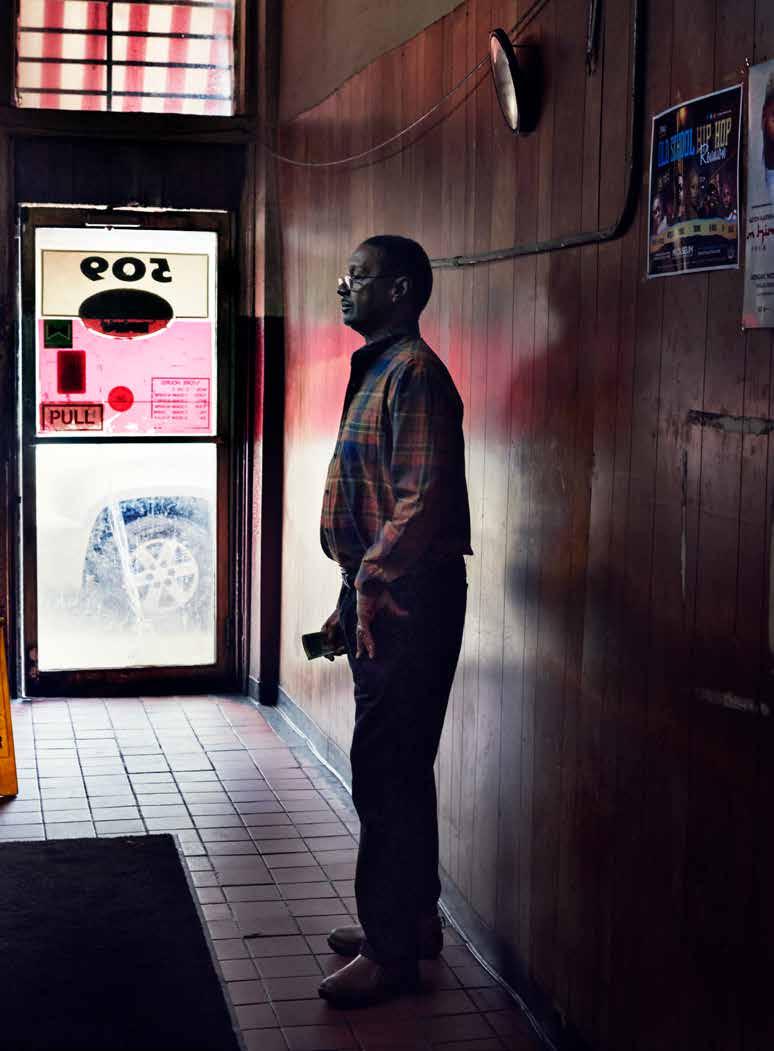

THE PIG EAR SANDWICH The Inn stands on the 500 block of Farish Street, a particularly insalubrious stretch next to a funeral company at the junction with Hobson. I find the door and walk into the dimly lit space. It appears frozen in time. A wornout ‘wate and fate’ scale offers to measure your weight and predict your fortune - all for a penny, while on the wall an advert promotes Champale, the effervescent beer brewed to taste like sparkling wine and known as ‘poor man’s champagne’.

Despite first impressions, the smells emanating from the kitchen are much more promising and the Big Apple’s welcome is as warm as an embrace between old friends. I join the queue where salutations and sandwich orders are toing and froing across the counter in the rich twang of the Deep South. “I’ll have me two please, darlin’”, says one regular to the cook, Lavette Mack. “Six to go, honey”, says another. Mack flits between the stovetop and the cash till, sending the customers on their way with a smile, a bag of fresh pig ear sandwiches, and a “see you tomorrow.”

I reach the front of the line and I ask Mack, who’s worked at the Inn for more than two decades, what she recommends to have in. She suggests a “smoke and ears”: a sandwich filled with pig ear accompanied by another filled with the ground, grilled meat from a local smoked sausage, known as a Red Rose.

I take a seat in the dining area and Mack arrives moments later with two freshly filled slider buns in a basket. “There you go hon’. They got an extra special ingredient. They served with Lavette’s love”, she says with a chuckle.

I try a bite of the pig ear sandwich first. It’s juicy and gelatinous, like a cooked lasagna sheet, with some crunch from the cartilage as well as the cabbage in the accompanying slaw. There’s a mix of different flavours: sweet bacon from the ear, a slight kick from a dash of mustard, and a final after-punch from the hot chilli sauce. The “smoke” meanwhile has a deeper, meatier tang - from the beef hearts in the smoked sausage and the char from the grill.

Opposite me, a man with a kind face and sad eyes is tucking into the very same dish. He introduces himself as Carlos Laverne White and tells me that he’s been coming to the Big Apple since he was just three years old. He’s now in his mid-fifties. “My folks used to bring me all the time. This place is very important in the community, always has been. For people who don’t got much money, it means we can still eat. I come once a week when I got me the dollar and sixty cents to pay for a “smoke and ears”, he says.

“Some of the older regulars can even remember back to a time when it cost just 10 cents!” says Geno Lee, the Inn’s current owner. “In all the time that we’ve been open, we’ve only gone up a couple of pennies a year. It’s still very affordable.”

JUAN ”BIG JOHN” MORA I ask him about the history of the place. “It’s always been a family affair”, he replies. “It was started by my great grandfather Juan “Big John” Mora who came to Jackson from Mexico City in the early 1930s. He started earning money by making and selling hot tamales on street corners. He cooked them in an old tin drum over an open fire and sold them for 12 cents a dozen”, says Lee. “Soon he progressed to a hand-made food cart, then, when he had a hundred dollars in his pocket, he decided to buy an old Sicilian grocery store and open it as a restaurant.”

Big John named the premises after this favourite dance, the Big Apple, and settled on a simple bill of fare including the grocery’s offering of bologna alongside his own hot tamales – both of which are still on the menu today.

Chef Lavette Mack stirs the pig ears.

I ASK LEE HOW HE CARRIES ON THAT LEGACY. “I ORIGINALLY STUDIED

FOR THE PRIESTHOOD THEN CHANGED MY MIND”, HE SAYS. “THE IDEA OF MINISTRY STILL APPEALED TO ME THOUGH SO I DECIDED TO

DEDICATE MYSELF TO FARISH STREET AND THE PEOPLE HERE INSTEAD.”

The Inn’s most famous dish came about purely by accident.

“One day the butcher offered him some pigs’ ears for free. He snapped them up, but had no idea what to do with them. He tried deep-frying them, then grilling them, but couldn’t get them tender enough. Finally, he discovered that if he boiled them for two whole days they’d be good enough to eat. Two whole days! Now it only takes us two hours to do the same thing in a pressure cooker. Back in those days most African Americans just ate boiled ears with cornbread and collared greens, but Big John decided to serve them in a bun. He added the slaw, the mustard and, being Mexican, the hot chilli sauce. The pig ear sandwich was his invention.”

In no time the sandwich, and the Inn, had become a roaring success. “By this point my grandfather had married a black woman and Farish Street was the place to have a business and have a good time if you were black. The area was known as ‘Little Harlem’ and was always packed with people. Music was a big part of the scene. You had live music in the street outside the Big Apple. You had artists like Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong playing at the Crystal Palace and the Alamo a few blocks away. We even had the blues musician Sonny Boy Williamson living upstairs at one point”, he says. “He taught my father how to fish when he wasn’t playing the harmonica! Then Medgar Evers moved in. Medgar was the field secretary for the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). By this time my grandfather had taken over running the Inn. He was mixed race – a black Latino – and a keen supporter of Civil Rights, so he let Evers and his followers meet in the Inn to discuss their strategy for overcoming racial segregation.”

Lee’s grandfather also went one step further - using money earned from the Big Apple to support the movement. “Any of the activists that got arrested, he bailed them out of jail, took them home, gave them a meal and fresh clothes so they could get back out and fight for justice. My mom was a Civil Rights activist too – she was arrested for doing sit-ins demanding racial equality. I guess you could say that doing the right thing is something that runs in the family.”

I ask Lee how he carries on that legacy. “I originally studied for the priesthood then changed my mind”, he says. “The idea of ministry still appealed to me though so I decided to dedicate myself to Farish Street and the people here instead.”

FREE ”EARS AND SMOKE” FOR THE KIDS Lee tells me how he’d let poor local kids come to the Inn after school; those who did their homework got an “ear and smoke” for free. He also recounts the story of a 5-year-old boy who’d be put on the front porch all night if his mother was inside “making her money.” “I’d pick him up, leave a note so his mom know where her son was, then take him home and give him pig ear sandwiches for dinner”, he says.

“So while running the Big Apple might not make me rich, I leave the Inn each night feeling satisfied”, he says. “By keeping the prices real low I make sure nobody in the neighbourhood goes hungry. And people keep coming back time and time again from all over just for the sandwiches – and that’s important to keep Farish Street alive; to keep what’s left of the community going. It’s a good feeling. It’s amazing what a difference you can make with a pig’s ear.”

The menu has been more or less the same since the beginning.