By Shannon Geisen Park Rapids Enterprise

By Shannon Geisen Park Rapids Enterprise

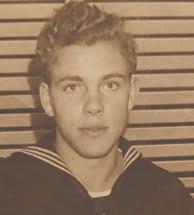

Bob and Debbie Peters en will tell you there has always been a thread with uniforms in their family, whether it was as military serviceman, paramedic, wildland firefighter, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service officer, Cub Scout leader or Boy Scout.

“We’ve always served in that capacity in the community in one way or another,” Bob said in a phone interview. “We’ve always been a fami ly that’s really felt this country has given us so much, we want to give back to it.”

The Petersens have been recognized for their dedi cation to the Mid-Michi gan Honor Flight program since 2015. Bob is vice president, while Debbie handles registration, lan yards and bookwork.

“We’re honored to serve with them. Within our team, we have to raise over $250,000 in volun teer donations, so it keeps us very busy doing that,” Bob said.

A 1973 Park Rapids High School graduate, Bob was born and raised in Park Rapids.

Debbie was born in

Minneapolis. “I moved to Park Rapids when I was in ninth grade and graduated from Park Rapids High School in ‘73 also,” she said.

“I didn’t like girls until she walked into the room,” Bob recalled of their ninth-grade encounter. “What’s the Bambi thing? I was twit terpated. I had my hors es and my hunting. I was OK. Then she walked in and rocked my whole world.”

They’ve been married for 48 years.

“I always say I get five years’ extra credit because it took five years to get her to like me,” Bob said.

During their mar ried life, they have lived in numerous places, including Park Rapids. They currently reside in Michigan.

Bob served in the U.S. Army infantry.

“I did four years in active Army. I was with the 4th Infantry Divi sion during the Vietnam era, then I was with the 2nd Infantry Division up on the DMZ in Korea. Then I came back state side and went with the 7th Infantry Division out

of Fort Ord, Calif.,” he explained. “When I got out in ‘78, I came back to Park Rapids and I joined the active Army reserve and was stationed out of Walker. I was assigned with the unit in Fort Wainwright, Alaska. That was our sister unit. I did four years with the active Army reserve.”

When he graduat ed from Brainerd tech school, he moved to Michigian where he got a job as a research diver for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service working on invasive species.

In 1999, he joined the Army National Guard.

“I always say I had a mid-life crisis, and rath er than get a younger woman and a motorcy cle, it was safer for me to go back into the mili tary,” he said.

He served for five years at the Camp Grayling Joint Maneuver Training Center at Grayling, Mich. It’s the largest National Guard training facility in the U.S.

Bob worked on the M1 Abrams tanks.

He was sent to Califor nia, Germany, Afghani stan and a couple loca tions stateside.

All told, Bob spent 13 years in the military.

The birth of their first grandson was pivotal.

“I kinda decided that fam ily was more important than having a few more years of military, as far as retirement.”

The Petersens have two daughters and four grandchildren.

The Petersens’ commitment to Honor Flights began in 2015 when their oldest grandson, Tyler, wanted to complete an Eagle Scout Project.

Tyler decided to partner with Mid-Michigan Honor Flight “because he want ed to do something with the veterans,” Debbie explained. “That’s when we started get ting involved.”

Bob said Tyler wanted “to fund four combat Vietnam veterans to go with four WWII veterans to Washington, D.C. to see the memorials this country built for them.”

Tyler raised $13,000 to accomplish this goal.

He was paired with a vet on the trip who was a POW in Vietnam.

“Tyler was his guardian. So you have an honoree and a guardian,” Bob explained. “Through this project, he was able to lay a wreath at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier with this veteran and a colonel who had been in WWII, Korea and Vietnam.”

Later that evening, the Viet nam veterans were given their 50-year pin commemorat

ing their service to the war.

“This Vietnam veteran turned around and pinned it on my grandson. My grandson said, ‘Sir, I need to earn this.’ And he said, ‘Son, you earned it,’” Bob recalled.

There are 138 Honor Flights hubs across the U.S.

Mid-Michigan Honor Flight hosts two flights each year, one in the fall and spring.

“We take over 100 vets per flight to Washington, D.C.,” Bob said.

Fully committed to this cause, the Petersens have for feited vacations and donated their energy to raising funds. Everything they do is vol untary. They do not accept reimbursement for their time, gas expenses, hotels, meals or other expenses.

“We cover 51 counties, so we’re very mobile,” Bob explained.

It is a nonprofit organiza tion, so “almost every penny that we earn goes toward accomplishing this mission,” he said.

“Why do we do this? We’ve seen what it’s like to live outside this country. We’ve seen the impact the veter an community has had on this world. If it wasn’t for them and their service, we wouldn’t have the lifestyle that we have. We need to do it. We owe it to this country,” Bob said.

Debbie said, “And we owe it to these veterans. When we go on these flights, it’s amazing. Some of them say it took 60 years for this healing to happen.”

One vet described it as “getting his soul back,” she

said. “A lot of these veterans have carried the pain from having to be in war and kill people for a lot of years. Once we take to them to D.C., the healing has finally started.” You can see the external scars, but not the internal ones, Bob added.

The names on memorial walls are not simply names, he continued. “Those are their 19-year-old comrades that saved their lives or gave their lives and sacrificed, whether it was to the country or what ever your belief is. You still served.”

Capturing history Bob shared the story of an American soldier in WWII who took a Belgian woman, recent ly liberated from concentration camp and still wearing pris on rags, to a dress shop and bought her a new dress.

“He told her, ‘Put this life behind you. Go ahead.’ Fast-forward. For 50 years, she always talked about the Holocaust and mentioned this soldier,” Bob said.

An Honor Flight veter an revealed that he was this unnamed soldier. But he’d never told his family. The guardian contacted the Belgian and arranged a conference call.

“Lo and behold, it was this gentleman. So 50 years later, she got healing and he realized that his kind gift was import ant. Five days later, he passed away. That history would’ve been gone without Honor Flight,” Bob said.

A Vietnam vet attended Honor Flight with his daughter as guardian. The vet handed Bob his cell phone, saying he has trouble telling people how he feels. A note on the phone explained that the vet was a sniper in Vietnam. It read: “My buddy and I were under attack. He tried to save my life. I tried to save his life. He did a better job, and he died in my arms. I’ve not made a friend since Vietnam, but I made friends on Honor Flight.”

Mid-Michigan Honor Flight and the Petersens have received awards.

But the focus is the veterans.

“We’re just kinda the wheels under the bus,” Bob said.

“They are the bus. It’s all about them.”

By Robin Fish Park Rapids Enterprise

By Robin Fish Park Rapids Enterprise

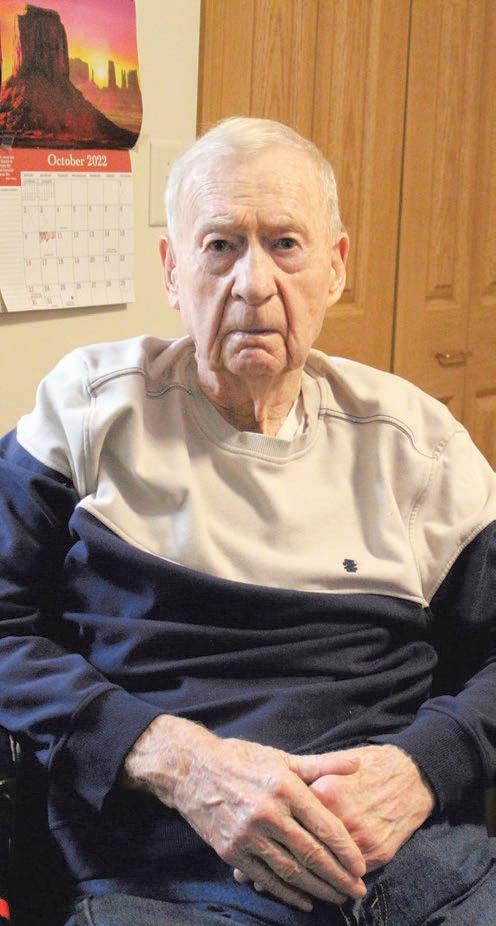

Despite being a res ident of the Cottages at Heritage, a memo ry care unit, Robert “Bob” Linder has a lot of details of his military service at ready recall, and according to Her itage staff, he loves to talk about it.

In a recent interview, the Hutchinson native shared some memories of his U.S. Army service from 1953-55.

“I served in Germany (in) regimental person nel,” he said, explaining that he “sat in the office and cut orders for any body going anyplace in Europe, or back to the United States.”

Despite having a desk job, he took an inter est in his basic training, where he was taught “to hit something with a rifle or with a howitzer. We learned how to fire the 105-mm howitzer, the 155-mm howitzer and rifles, you name it. Throw a hand grenade.”

As for his regular job, it was all about cutting orders, every day, for anybody traveling on assignment, on leave or

being transferred. “If the colonel went some place, you cut an order for him to go.”

What he enjoyed the most, Linder said, was traveling around Europe when he could get away – “which wasn’t very often.”

He recalled being in England, Scotland, France, Belgium, “right up the line” as far as Finland and Sweden. “I got to sit on the shores of Sweden,” he said, “but never to get up into their large cities. I’d like to because that’s where my dad was from.”

He also saw a great deal of Germany, and spent more time in Rome than anywhere else. “That’s a beautiful city,” he said. “Oh, man!

Lots of money there, I’ll tell you. … Went on down, saw where Columbus was born and raised. I got to see a lot.”

He said it was a real learning experience for him. He also enjoyed working with a lot of “nice guys from all over the United States,” playing sports and stay ing in good shape.

“I have good feelings

about the service,” he said, particularly the guys in regimental per sonnel. “Most of us had at least a high school education. Some of the guys had a college edu cation, or near com pletion. We were just a good bunch of guys. It makes all the world of difference.”

Linder, himself, later went to college in St. Cloud, earning a bach elor’s and a master’s degree. He taught in elementary schools from Plainfield, Iowa to Hutchinson, then at a small college in South Dakota, before spending the last 16 years of his career as an administra tor for Special Ed kids in rural Grand Forks and Walsh counties, N.D.

Eventually, Linder said, he settled in Park Rapids because his daughter lives here.

Asked what advice he would give anyone con sidering a career in the armed forces, Linder said, “I wish every per son in the world could visit France and see where all the American soldiers lay in graves, thousands of them. Boy,

that brought tears to my eyes, just being there –to think they gave up their lives for the rest of us. It is something else.”

Linder said he also thinks young people should serve because of the discipline as well as the chance to meet peo ple from across the U.S. and around the world. “Just no end to the num ber of people that I think GIs could meet and learn about, and learn more about their countries and what they had to live with,” he said.

Acknowledging that he was drafted, so he had no choice but to serve, Linder added, “I was fortunate. I learned how to fire a lot of weapons, but I never had to fire them in combat.”

He said he didn’t always think his Army time was a good expe rience, but he does now.

“I often wish I could go back to Europe,” he said. “I’d just travel, talk to people, see what they’re thinking. A lot of people in Europe speak our lan guage very well. They’re very interesting.”

By Robin Fish Park Rapids Enterprise

By Robin Fish Park Rapids Enterprise

Ronald “Ron” Goeh ring, a resident at the Heritage Living Center in Park Rapids, started life in Akeley, but has lived “from there all the way to Florida.”

His career experience includes working at R.D. Offutt Farms as well as Seagate Technology, a Twin Cities-based firm that made computer chips for satellites.

Part of that story was a stretch in the Army National Guard, from when he graduated high school in about 1966 until October 1977.

“I joined when I was in high school,” he said, “and the minute I graduated, they flew me off.”

Although the Viet nam conflict was heat

ing up at that time, he never served in-coun try – but his broth er, Jim, did.

“I don’t think, back then, you could have more than one family member in Vietnam,” he said. “He came out pretty bad.”

Recalling that Jim was bombed with poi son gas, Goehring said his brother was shipped home and died six months later.

Meanwhile, Ron was stationed at Fort Polk, Louisiana, where his duties included driving an armored personnel carrier – an amphibious tracked vehicle used to fetch soldiers back to

land after landing an airplane on water – as well as a “deuce-anda-half,” a 2-1/2 ton truck that was apt to get stuck in six-foot-deep mud holes. Sometimes,

he carried a .55-caliber machine gun around.

“It was a lot of work, but sometimes you had fun,” he said. “The thing that was import ant about it was about

the training, and all of the troops getting ready in case something hap pened.”

Goehring said it made him happy to think they were the backup for other troops.

“We were ready,” he said.

Despite serving state side, Goehring recalled bringing home some memories he’d rath er forget. “Some peo ple got hurt,” he said.

“Some people got killed on the rifle ranges. They were all dumb acci dents, like kids playing around. But then, we were all kids to start with.”

His advice to today’s young people who may be thinking about entering the service is, “If you don’t want to go in, don’t go in. Because

you have to want to go in and do what you do. The people that were ordered in there, they hated every minute of it and you could tell by how they acted. But some of us, we liked it.”

Specifically, he liked the work. “It wasn’t just all one job,” he said. “You have a lot of jobs to do.”

Later, Goehring par ticipated in the Akeley American Legion post, carrying the flag in the parade and helping build a big horse trail er decorated with flags and flowers.

Overall, he said of the service, “I enjoyed it. I don’t think I’d ever do it again. I’m a little too old for it!”

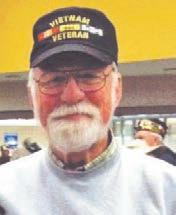

Editor’s note: The Park Rapids Enterprise interviewed Larry John son about his military service in Sept. 1993. He worked for the Park Rapids Police Depart ment in the early 1970s and was elected Hub bard County Sheriff in 1978, retiring in 1998. That article was re-pub lished in a Veterans Day tribute in 2003. Johnson was again interviewed in Jan. 2003 after returning from an 18-month Unit ed Nations peacekeep ing mission to Bosnia. Johnson passed away on Sept. 25, 2022. This arti cle is a compilation of previous ones.

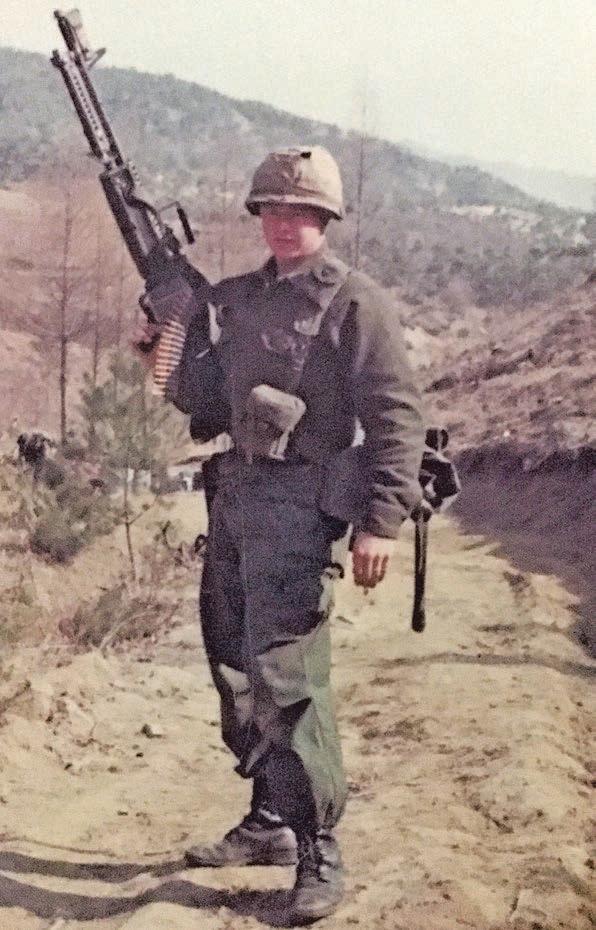

Born in Aitkin, Minn. in 1943, Larry John son enlisted in the U.S. Army in 1961. He served in Germany with the armored cavalry, spend ing 32 months overseas. He was discharged in 1964, at 21 years old. He volunteered for the Army again a year and a half later.

Before Johnson ended his stint in the mili tary in July 1968, he had seen two tours of duty in Vietnam and earned two Army Commenda tion Medals for heroism and two Bronze Stars.

Johnson and others in the 1st Cavalry were deployed to Qui Nhon, which later became a key port for U.S. military operations in Vietnam.

About 15 miles inland, a clearing had been dozed and the area became home for the next six month. Johnson’s camp blocked a valley and

served as a supply base.

Johnson was assigned to a six-man reconnais sance team. Sometimes the men went off in pairs, but always worked in small groups to remain undetected. The teams checked out var ious areas for guerrilla activity. The recon teams also set up ambushes

and booby traps.

The 1st Cavalry moved to An Khe, about 100 miles farther north. Johnson said this was thick jungle area, so dark you had to walk on paths and use a flashlight in the daytime.

While based at An Khe, Johnson earned his first medal. His recon team

was escorting a six-per son medical detachment.

Part of their operations was to provide medical services to distant ham lets.

As they were leaving one village, they were ambushed by a com pany of Viet Cong and North Vietnamese. They immediately called for

helicopters, but Johnson and others were pinned down for 30 to 45 min utes before the choppers arrived.

“They leveled the vil lage,” Johnson said.

The incident took place Dec. 23, 1965.

One of the officers, who felt the team had saved their lives and recognized they didn’t have to accompany the medical detachment, put the team in for the Commendation Medal. Each team member also received a Bronze Star.

“Basically, it’s because we survived it,” said Johnson.

After a year, the Army sent Johnson to Ger many. He was assigned to a missile outfit and attended a telecommu nications school for six weeks. “But it was all spit and polish,” John son said, so one night he and a buddy decided to volunteer to go back to Vietnam.

Johnson was reunit ed with his old outfit. All the faces were new, though.

It was 1967. Johnson was 22. He was at Chu Lai on the coast, much

closer to the demilita rized zone (DMZ), doing reconnaissance again.

The war had really heated up.

As a sergeant, John son earned his second Bronze Star and Com mendation Medal on March 20, 1968.

The Tet offensive had begun Jan. 30 and was continuing, the 1st Cav alry wanted information from a village and John son’s recon team was sent after it. They were going from hut to hut when a Viet Cong tossed a grenade into a hut Johnson and his partner were in.

“All I really did was knock him out of the way, but it saved his life,” Johnson said.

Then one of the men on the team walked outside another hut and stepped

on a landmine. Both of his legs were blown off. Johnson went out and brought him back. “I walked in his exact steps – no farther.”

With sincere humility, Johnson said there were a lot of soldiers who deserved medals who didn’t get them because they either weren’t rec ognized by someone or weren’t seen.

After six months, Johnson had earned his three stripes. He decided he’d had enough. He was granted an early out.

Like many other Viet nam veterans, Johnson has never talked much about the war.

Johnson became the only civilian in Bos nia-Herzegovina in seven years to be deco rated by the military.

Best of all, John son said, is a letter of

appreciation he received from then U.S. Secre tary of State Colin Pow ell, someone he greatly admires.

Johnson applied for peace-keeping duty via the internet. He was one of 170 selected for train ing from 5,000 applica tions. He thinks training he took at the FBI acad emy while he was serv ing as sheriff may have helped.

He was deployed in the summer of 2001. The first stop was in Sara jevo. Johnson was first stationed at Zvornik on the Serbia border as a civilian investigative detective.

“It’s where the mass graves were on the Serb side,” Johnson said. Archaeologists were mining the graves, attempting to identify the thousands of bodies.

Johnson described a grave with 247 bodies. “The last four rows were

all women and children. That’s when I wanted to get out of there. It was the result of ‘eth nic cleansing’...all in the name of religion.”

Johnson’s request was granted and he was sent to Tuzla, north of Sara jevo, on the Muslim side.

His mission was to work in targeting major organized crime and

support anti-terrorism efforts.

For national security reasons, Johnson can’t say what he did to earn the extraordinary hon ors he brought home from his service in Bos nia-Herzegovina.

One of his honors is a North Atlantic Treaty Organization Medal for Services as a member of the International Police

Task Force Eagle. He also received the Pennsylvania Commen dation Medal for out standing service to the Multi-National Division, an award from the 1st Battalion, 14th Infantry Regiment “Task Force Golden Dragons” and a UN Medal from the Tuzla region chief of opera tions and regional com mander.