7 minute read

THE BIRTH OF THE GENERATIVE SAFETY CULTURE

By / Natalie Bruckner • Photos courtesy of Local 71 Business Manager, Paul Crist

Safety in the sheet metal workers’ space is going through a fascinating transformation. Where safety was once considered a matter of compliance and processes, today it is evolving into a positive value system that engages people at all levels. This new approach is called a generative safety culture.

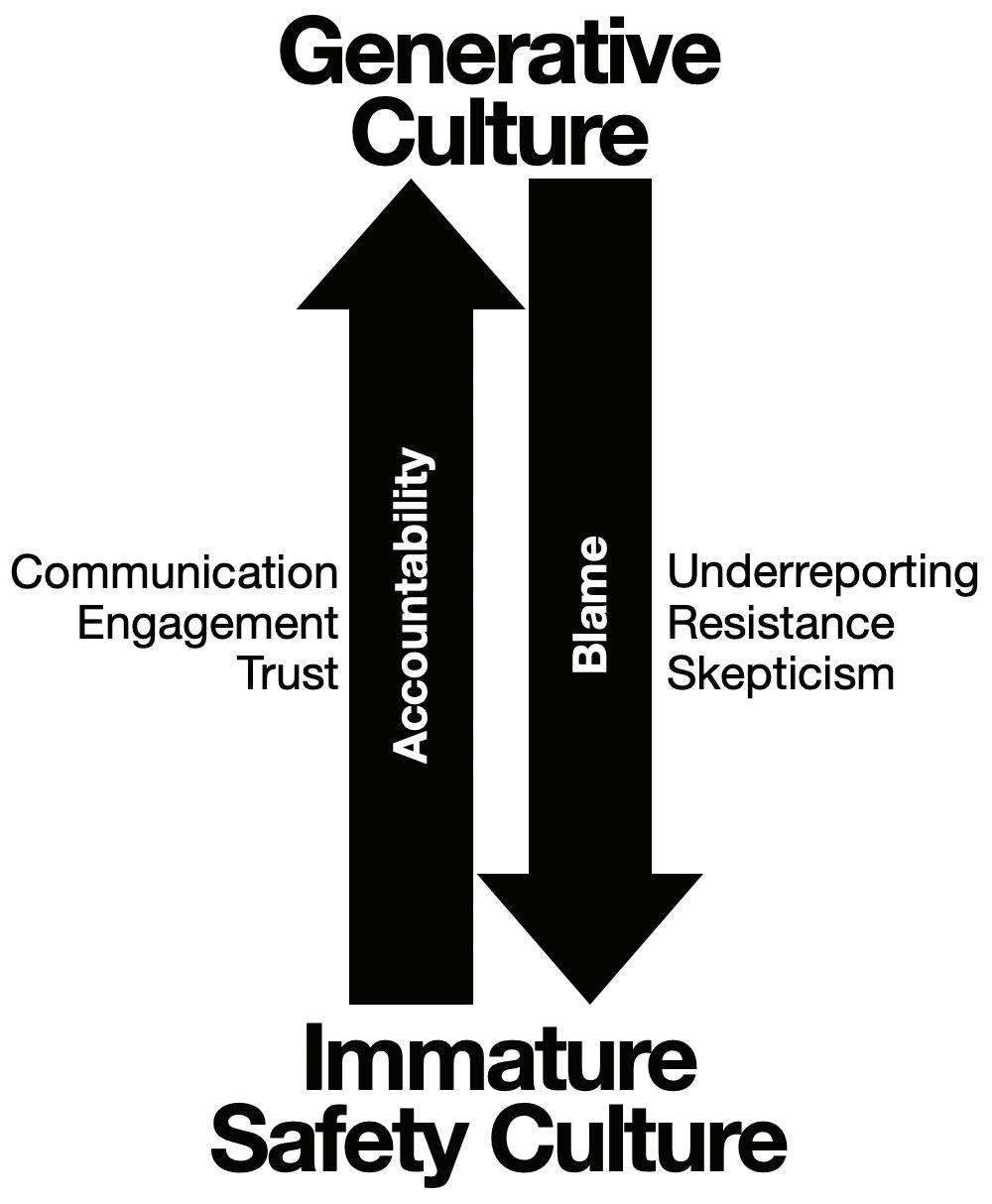

Simply put, this paradigm shift is about moving safety from a finger-pointing blame game to a system where everyone gets involved and looks out for themselves and each another.

SMACNA’s Director of Market Sectors and Health, Mike McCullion, has been involved in safety for more than 30 years and is excited about the changes.

“Safety used to be based on engineering and compliance, but now, especially with the COVID-19 pandemic, we are moving towards a science-based approach that includes human factors, such as occupational illnesses and infectious diseases,” McCullion says. “It is transforming from an engineering mindset to a scientific mindset.”

He refers to respirators as a prime example of this. Once an integral part of safety when working with chemicals or silica, today they are a necessity. “In certain tasks, workers would use N95 respirator masks, but with the pandemic a lot of nuances have come out about masks, especially the difference between a facial covering or mask and a respirator,” he says. “There is a clear distinction that needs to be made and to understand the science behind it for the well-being of the worker.”

Phillip Ragain, director of training and human performance at The RAD Group, who was on the safety panel at the 2020 Partners In Progress conference, says he is seeing an increasing number of organizations jump on this generative safety culture train and become a lot more proactive.

“In what is sometimes called ‘the good old days,’ it was common for people to boast about the hazards, incidents, and near misses they endured at work,” Raigan says. “Tolerating risk was not only seen as part of the job, it was regarded informally as a badge of honor.

“I recall one client that manufactured very large pieces of industrial equipment. When a piece of equipment was completed, the owner of the company would walk the elevated beams of that equipment without fall protection, almost like a tightrope walker. It was his way of commissioning it for service. The owner, and many of the employees who witnessed the display, saw it as a demonstration of courage and solidarity with the workers who put themselves at risk to build the equipment. It was a strange feature of the culture at the time—the belief that exposing oneself to unnecessary risk is respectable rather than foolhardy.”

However, Ragain says, this attitude is becoming one of the past. “Risky workplace behavior is no longer admired, and the idea that tolerating risk makes you a better worker appears to vanish a little every day,” he says.

— Phillip Ragain, director of training and human performance at The RAD Group

With the changing times, understanding what this generative culture means can be tricky and may get misinterpreted. “The systems that some organizations have previously put into place, such as ‘good catch’ programs, never get off the ground when people fear that they will be blamed if something goes wrong,” Raigan says. “When people are concerned that leaders are looking for someone to blame, they stop communicating [reporting], see speaking up as snitching, and resist safety programs that they consider blame traps.”

Instead, leaders in the industry are looking to become more proactive by building a culture of trust, engagement, and fair accountability.

Local 71 Business Manager, Paul Crist, has found a safety program that seems to have hit the nail on the head. Under his direction, Local 71 created a training incentive program that has generated more than 16,000 hours of additional safety and trade-related training for 350-plus members in the Buffalo area of New York.

—Mike McCullion, SMACNA’s Director of Market Sectors and Health

Under the program (which started in 2013), Local 71 members receive one ticket for every four hours of additional training they participate in each year. This is put into a pot that is worth more than $25,000 and consists of an array of prizes that are awarded during a yearly breakfast banquet.

The idea came about after Crist attended a painters’ union award breakfast. “We basically stole the idea and implemented it on a smaller scale,” Crist laughs. “I was tired of the arguments between contractors—who felt the workers should come fully prepared with the safety training and skills—and workers— who felt that if contractors wanted them to have the training then contractors should pay for it.

“So, we came together with our local SMACNA chapter and set three cents aside from each side, which gave us six cents per hour and generates a $30,000 budget. The JATC pays for the instructor and materials, but New York state law dictates that the JATC may not give out prizes out with that money, so the cash we set aside goes toward the prizes.”

Crist says it is all about keeping everyone safe. “We do this so we don’t have to call any family members to tell them there was an accident on the job.” He received a Safety Matters Award from the Sheet Metal Occupational Health Institute Trust (SMOHIT) for this program.

While the accountability piece can be the most important and difficult to change, Ragain says, “when leaders get it right— and stop confusing blame for accountability—the other pieces begin to fall into place.”

Being such a new approach, however, means getting it right isn’t always easy when the the industry’s attitude toward safety has traditionally focused on number of accidents, cost overruns, and project delays. This has, in turn, bred a mistrust for safety leaders who were sometimes seen as rule-abiding naggers.

Creating this generative safety culture requires buy-in and a shift in mindset. “We need everyone to understand that the generative culture differs greatly from a safety program,” McCullion says. “It’s the ‘why’ rather than the ‘how’, and a safety culture is not a one-size-fits-all program.”

The approach for a company with 25 employees will vastly differ from a business with 250 employees, and as McCullion mentions, not only does the culture have to address that company but also evolve and mature within the company. That takes a team.

“Everyone needs to take pride in it,” McCullion explains. “To do that, employees must understand that this will benefit their overall wellness. When you find what motivates someone, both on and off the job, you can change behaviors.”

Ragain adds that, in his experience, there are a number of things that have to be done for organizations and industries to move toward a mature, generative safety culture. The key among them is the shift in focus from numbers to people.

“You need to look at who is being impacted,” he says. “That does not mean leaders stop paying attention to lagging performance metrics, but instead communicate and demonstrate a genuine concern for the well-being of people in their organizations. Safety transforms from ‘what we have to do’ to ‘what we ought to do.’ This is an important first step.”

But as with any change, it needs to start at the top. “Yes, buy-in is important, but we need to ensure there is open communication between management and labor,” McCullion says. “At SMACNA, we work closely with SMART and SMOHIT to give everyone the resources and training they need. Take the safety managers, for example. Today, they need to wear a lot of hats. They need to be aware of environmental and industrial hygienist principles, as well, understanding how chemicals affect the body. In the end, successes come from good communication.”

Looking back at the history of occupational safety, SMACNA and SMART have already come a long way, but there is still a long way to go, but with the help of technology, science, and cooperation between management and labor, anything is possible.

“What I see beginning to emerge is a more comprehensive sense of responsibility where people at all levels of the organization own what they can impact and communicate more effectively up and down the chain of command allowing others to do the same,” McCullion says. “Safety is becoming more collaborative, less combative. It is becoming ‘how we work,’ not ‘extra work.’ Or at least I hope that’s where we are headed.” ▪

Natalie is an award-winning writer who has worked in the United Kingdom, Germany, Spain, the United States, and Canada. She has more than 23 years experience as a journalist, editor, and brand builder, specializing in construction and transportation.