BRITISH ART NEWS

THE NEWSLETTER OF THE BRITISH ART NETWORK

April 2023

1

The British Art Network (BAN) promotes curatorial research, practice and theory in the field of British art. Our members include curators, academics, artist-researchers, conservators, producers and programmers at all stages of their professional lives. All are actively engaged in caring for, developing and presenting British art, whether in museums, galleries, heritage settings or art spaces, in published form, online or in educational settings, across the UK and beyond.

2 CONTENTS Convenor’s Introduction……………………………….…………………………………………….….3 Coordinator’s Introduction………………………………………………………….…………….……8 New Team Members…………………………………………………………………….…………….….9 Announcing: New Emerging Curators Group 2023............................................11 Announcing: Research Groups 2023 13 Alina Khakoo: Report on Panchayat Workshop..................................................14 Emma Roodhouse: On Seven Years with the Landscape Research Group.........18 Alice Correia: On Co-Curating ‘A Tall Order!’ …...................................................22 An Interview with Sarah Victoria Turner............................................................27 The Cover Image…………………..............................................................................34

The British Art Network is supported by Tate and the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art with additional public funding provided by the National Lottery through Arts Council England.

CONVENOR’S INTRODUCTION

BAN’s annual conference in November 2022 helped mark the tenth anniversary of the British Art Network, the official start date of which was (as reported to ACE at the time) 21 December 2012. This date, heralded as the day on which the world would end, according to a spurious but widely known interpretation of the Mayan calendar, provided a device for thinking through a moment of change and a decade of activity. The panels and presentations organised by our three distinguished guest convenors – the artist and writer Sonia Boué, Bryan Biggs, long-serving curator of Bluecoat Liverpool and Victoria Walsh, Professor at the Royal College of Art, explored questions of difference and neurodiversity, locality and globalism, decolonisation, decentring, and the sites of production of curatorial knowledge, while a roundtable at Tate Britain provided a platform for a group of senior figures to reflect on these questions and their own trajectories. Niyaz Saghari’s film Unravelled, premiered at that event, featured the guest convenors and other voices reflecting on these questions, and weaving these themes together in a compelling way. Niyaz’s films, in long and shorter versions (both with a BSL option), are already freely available online. Conference films and additional content are being prepared for online publication.

3

Day 3 of the BAN annual conference 2022, at Bluecoat, Liverpool, with on stage (from left), session convenor Bryan Biggs, and speakers Mohini Chandra (Falmouth University) and Skinder Hundal (British Council)

Overall, the conference content exposed quite how far we, in the curatorial field, have travelled since 2012. While a decade is not, perhaps, such an extensive period of time, poised somewhere between memory and history, but across the various panels and presentations, as people checked back in their diaries or reflected on their recollections of that year, there was a definite sense of some real transformations –particularly in the role of the digital (with the dramatic rise of social media), in the growing recognition of disability and neurodivergence, and new curatorial engagements in mainstream or established organisational contexts with race and representation. There were, to be sure, not only longer histories in play – Derek Horton and Alice Correia (who writes below) looked at a deeper history of curatorial change at Touchstones, Rochdale – but also a collective understanding of the last decade as witnessing some rapid and seminal developments. From the vantage point of the British Art Network itself, the chance to revisit the founding statements and early programme has been keenly illuminating: the way that British art curating was being conceived then – focused firmly on permanent collections, framed by a definition of British art set by the chronological and media scope of the collection at Tate, and shaped by the assumption that those engaged in curating would be in fulltime, permanent roles in museums or academia – feels rather distant. The field of curating now seems much less definitely structured around collections work and fixed roles, much more flexibly and dynamically interconnected with academic and creative enquiry. Whether these changes are simply positive, resulting in greater individual freedom, critical autonomy and workforce diversity, or whether they also involve damaging uncertainties and limitations (and perhaps let organisations ‘off the hook’ when it comes to developing the skills and expertise they depend upon) is another matter which we perhaps only began to explore in the programme. Similarly, whether ‘British art’ as an overarching concept is legitimate, or even useful, from a global perspective, or from a regional and national perspective around the British Isles and Ireland, was, again, only touched upon.

The annual conference was preceded by a new activity for BAN, the Curatorial Forum which was organised in partnership with the Yale Center for British Art (YCBA) in October. This, our first residential programme, involved eleven curators working in the UK, Australia, Europe and the USA, who were brought together in New Haven for an intensive week of gallery visits, workshops and discussion. For more on the Forum, Conference, and on BAN’s programme through 2022, see our new Annual Report which is now available online. The Forum was especially illuminating in bringing together a range of international perspectives, something we want to continue to develop through the Forum and beyond in 2023 and 2024. In this coming period, we want to gather up and consolidate the learning developed through BAN’s Research Groups, the new Seminars and, of course, our Emerging Curators Group, as well as

4

through our conferences and now, the Forum. BAN is the sum of this activity, led by its Members, and we are pleased to feature below reflections from Emma Roodhouse on the changing views and understandings of the Landscape Group –supported by BAN since the beginning of the Research Group Programme – and from a more recent member, Alina Khakoo, on an event organised under the aegis of a similarly long-standing BAN group, Black British Art. The new and continuing Research Groups are noted below, as too are the 2023 membership of the Emerging Curators Group.

We are also currently calling for applications for this year’s Seminar Support. As ever, information on forthcoming and past events and open opportunities can be found on the website.

The team that will support the programme for 2023 and beyond has taken a new shape, with the return of Jessica Juckes, familiar to many of you as BAN Coordinator, based in Tate’s National Programmes, and with Bryony Botwright-Rance, Networks Manager and Anthony Tino, Networks Administrator, at PMC working on BAN programming and development along with the Centre’s other networks and vocational opportunities. Over the last, busy months Rosalind Stockill has played a crucial role as Head of National Partnerships providing maternity cover for Heather Sturdy, who has returned to Tate this month. Bryony and Anthony introduce

5

Members of the Curatorial Forum viewing artworks in the Yale Center for British Art in October 2022

themselves below. Also below we have an interview with Sarah Turner, Acting Director at the Paul Mellon Centre following the departure of Mark Hallett, who has become Director of the Courtauld Institute of Art. Mark was pivotal in establishing the Centre’s generous support of the Network, which has underpinned the changes and expansion over the last few years. The tremendous rise in BAN membership and engagement since the PMC came on board is charted in our Annual Report, and is one key measure of the importance of the Centre’s support. Sarah has been closely involved with BAN for several years, including serving on our Steering Group. Here Sarah reflects on her own academic and curatorial engagements with British art, and the changes, challenges and opportunities she has observed.

Within the Steering Group, we have said goodbye to three members who have served their terms, contributing enormously to the work of the Network – Fiona Kearney, Dot Price and Sophia Hao. The Steering Group is a vital mechanism for BAN, providing oversight and direction for the Network team and our programme, and we are extremely grateful for their contributions along with the ongoing contributions of our current members. We are also pleased to announce two new members of the Group: Bryan Biggs, mentioned above as one of our guest convenors of the 2022 conference, with an amazing record as a transformative curator and administrator at the Bluecoat Liverpool stretching over four decades, and Cicely Robinson, one of our original ‘Early Career Curators Group’ cohort in 2015–2018 (now run as the Emerging Curators Group), whose career has included periods at the Watts Gallery and Palace House, Newmarket during moments of seminal change, and who is now a freelance curator, researcher and consultant.

With the new team in place, and our Steering Group’s vital oversight and input, we look forward to supporting our Members and the programme ahead for 2023.

Martin Myrone BAN Convenor

6

Curatorial tour of RISD, Providence, during the YCBA/BAN Curatorial Forum, October 2022

Curatorial tour of RISD, Providence, during the YCBA/BAN Curatorial Forum, October 2022

COORDINATOR’S INTRODUCTION

A Note from Jess Juckes

Dear BAN Members,

I am happy to share that I am back full time working on the British Art Network at Tate Liverpool, following my maternity leave. It has been exciting to look over all that’s been achieved over the past year, from the ten-year conference, to the BAN/YCBA Curatorial Forum, to a wide range of bursary activity. I’m looking forward to supporting the membership and the various strands of programming again, and working towards key objectives including increased access, inclusion and equity and welcoming more global voices to the network.

While I have been away, the BAN team has expanded to welcome new colleagues and roles. In addition to myself as full-time BAN Coordinator and Martin Myrone as BAN Convenor, we have Anthony Tino as PMC Networks Administrator, Bryony Botwright-Rance as PMC Networks Manager and Ros Stockill, acting as Head of National Partnerships at Tate until Heather Sturdy returns from maternity leave in May. Below, Anthony and Bryony introduce themselves.

All my best to everyone,

Jessica Juckes BAN Coordinator

8

NEW TEAM MEMBERS

Introducing new members to the British Art Network team from Tate and Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art

Bryony Botwright-Rance,

Networks Manager, PMC

You may know me from my work with the PMC’s Doctoral Researchers Network, Early Career Researchers Network and Art Trade Seminar, which I have been running since 2020. I have worked at the Paul Mellon Centre since 2016 and have watched the expansion of the British Art Network’s rich programme of activities, vocational development and research support opportunities from afar, admiring the commitment and engagement of the Network’s Members and the enthusiasm of the BAN team. I was thrilled to be invited into the fold last October and include BAN under my networks remit at the PMC.

Since then, I have worked on the inaugural Curatorial Forum, BAN’s annual conference, and participated in the appointment of the 2023 Research Groups and Emerging Curators Group. We have spent hours in discussions over Zoom, on trains, over coffee and ever so occasionally in person, designing the upcoming programme which will continue to be values-led and responsive to the needs of the Members and the state of the curatorial field today.

Anthony Tino, Networks Administrator, PMC

I am thrilled to have recently joined the PMC as Networks Administrator, working with and across PMC’s networks including the Early Career Researchers Network, Doctoral Researchers Network and, of course, the British Art Network with PMC and Tate. With a background in curating and artist publishing, my practice has historically prioritised the inclusion of artists from underrepresented backgrounds within projects and platforms which emphasise intercultural exchange.

9

Prior to joining PMC, I worked at Camden Art Centre as Interim Exhibitions Assistant while simultaneously working on independent curating and completing my MA in Arts Administration & Cultural Policy at Goldsmiths, University of London. In the past, I have cofounded two artists’ book-related platforms, and have worked with other subject-specialist platforms, extensively with contemporary art from the SWANA (South-West Asia, North Africa) regions. Having been born and raised in New York, I am very excited for the opportunity to provide an international perspective to practitioners and researchers and excited to be supporting this initiative as an arts administrator.

10

NEW EMERGING CURATORS GROUP 2023

We are delighted to announce that the fifteen members of the Emerging Curators Group 2023 are:

Abigail Allan

Cait Heaney

Elinor Hayes

Hanifah Sogbanmu

Jazz Swali

Jenny Tipton

Jess Baxter

Katherine Murphy

Lucy Mounfield

Mary Stevens

Miriam Mallalieu

Polly Wright

Rhona Sword

Surya Bowyer

Sarah Cox

For more on the group and individual profiles, please visit the Emerging Curators Group section of the BAN website, here.

11

12

RESEARCH GROUPS 2023

In 2023, we are pleased to support fourteen Research Groups:

Art and the Women’s Movement in the UK 1970–1988

Art Practices and British Central Eastern European Diaspora

Artist-Run Initiatives in Britain

Black British Art

British Catholic Material Culture 1538–1829

British Digital Art

Chai Shai: Asian British Art

Disability in British Art

Ignorant Art Schools

New Dialogues: Art Created Historically in Mental Health Settings

Northern Irish Art

A Place-Based History of Art

Queer British Art

Race, Empire and the Pre-Raphaelites

For more on these groups, see the Research Groups section of the BAN website, here.

13

ALINA KHAKOO

REPORT OF A WORKSHOP ON THE PANCHAYAT ARCHIVE HELD AT THE TATE LIBRARY AND ARCHIVE, TATE BRITAIN, 23 SEPTEMBER 2022

Panchayat was founded in London in 1988 to advocate for the representation of artists from the global majority, especially those who produced work about cultural identity. Panchayat’s collection includes a library and an archive that provide an overview of the cultural activities and activism of these artists, predominantly in Britain, North America and several countries in Europe. The archive is now held in the Special Collections of Tate Library.

14

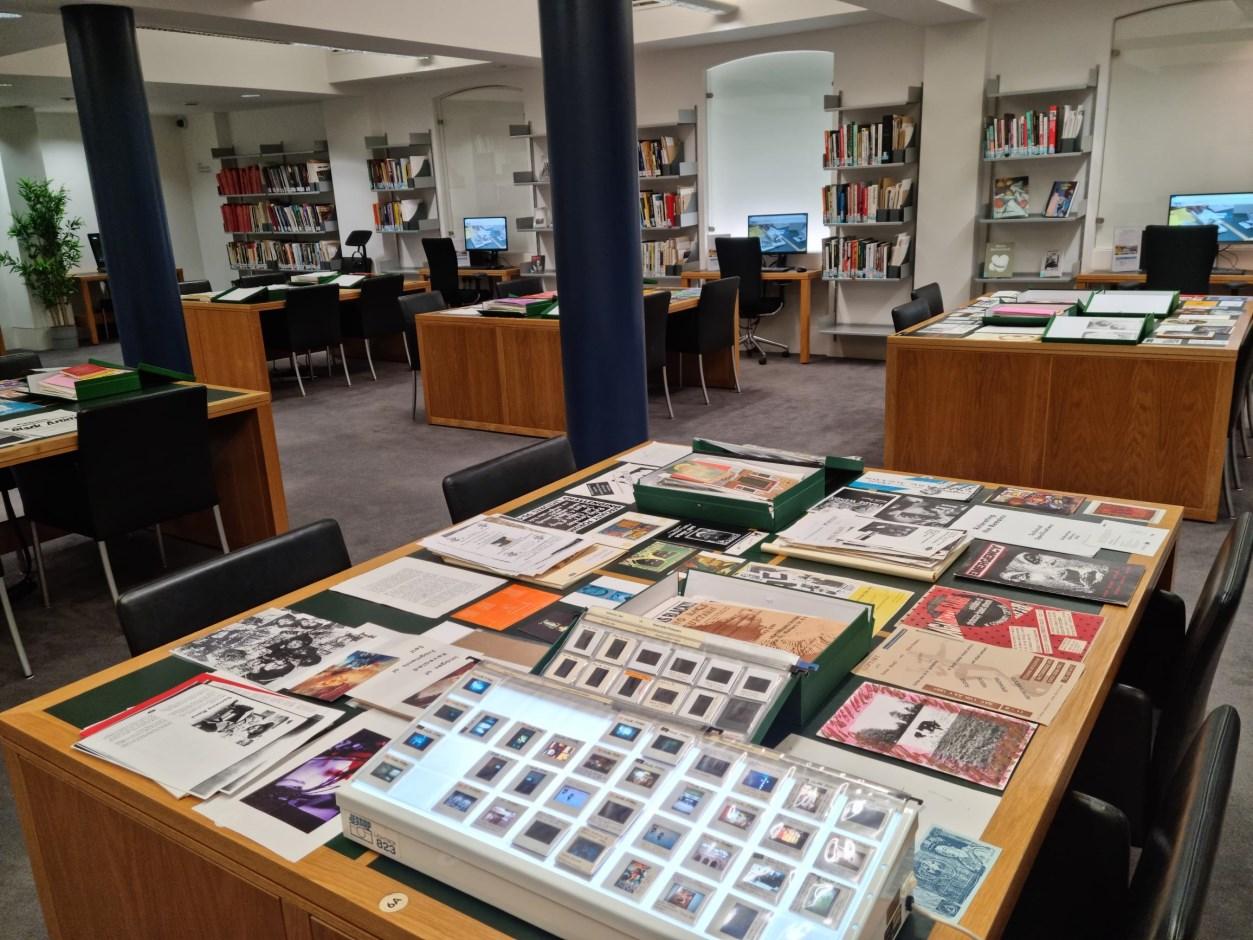

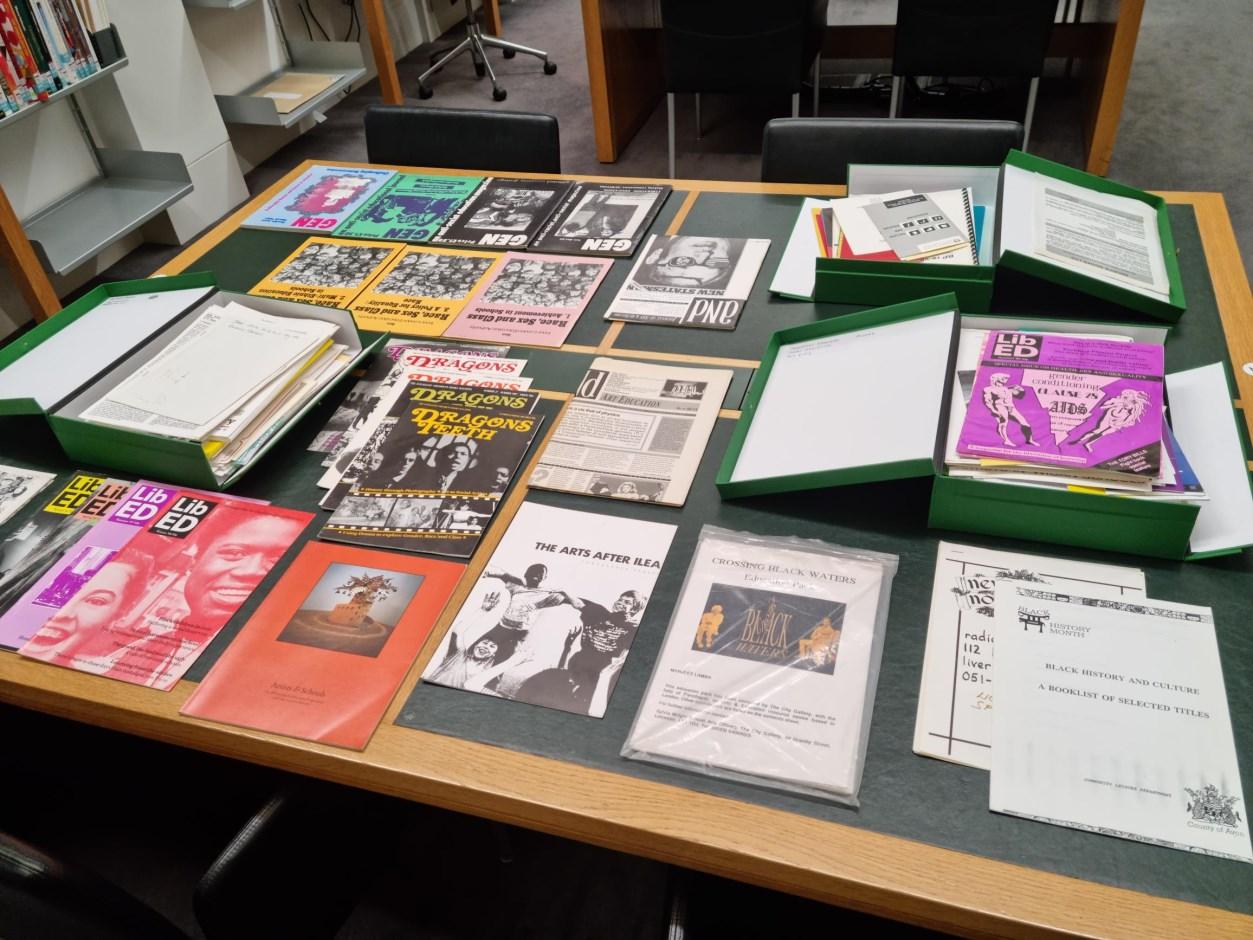

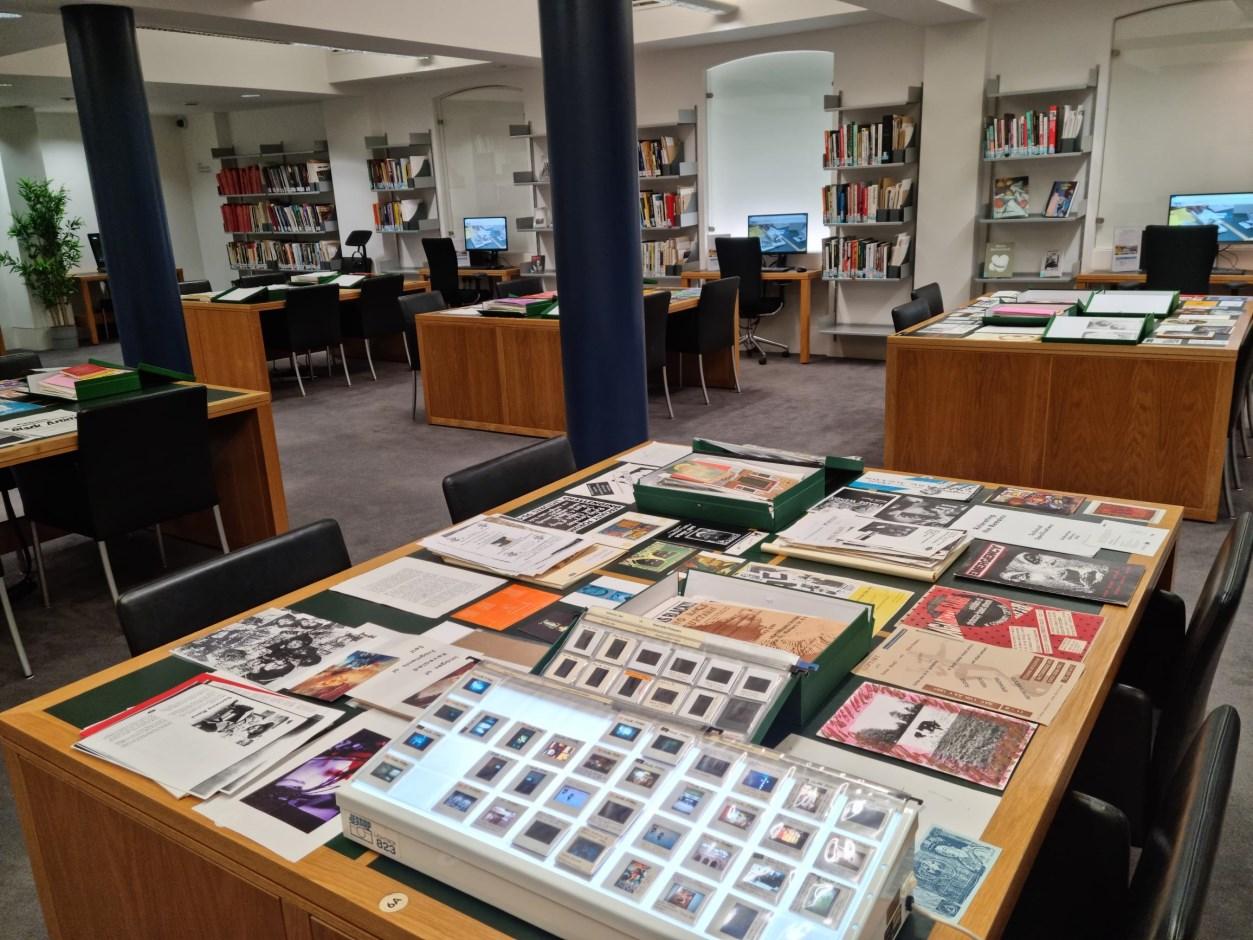

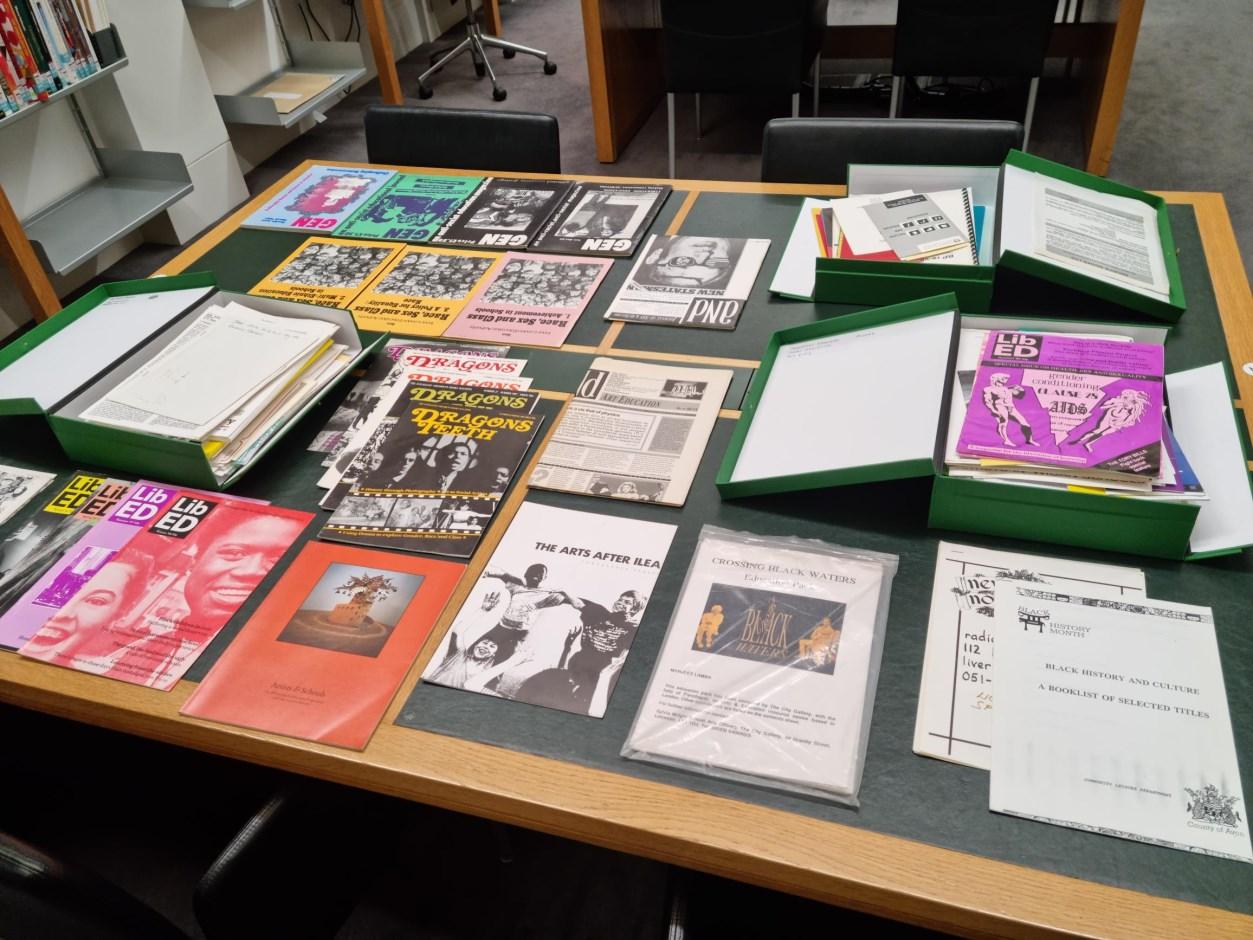

Panchayat study day at the Tate Library and Archive, Tate Britain, 23 September 2022, Photograph: Gustavo Grandal Montero

On Friday 23 September 2022, the British Art Network’s Black British Art Research Group, Alina Khakoo and Tate Librarians held a study day at Panchayat. We began the workshop with introductions by Lizzie Robles and Marlene Smith about the Black British Art Research Group, before Alice Correia and Alina Khakoo gave a brief history of Panchayat. Katie Blackford and Gustavo Grandal Montero then spoke about Tate’s acquisition of the Panchayat archive in 2015 and the Provisional Semantics digitisation project.

The rest of the workshop participants then introduced themselves. They encompassed: artists (Nina Edge, Valda Jackson, Radha Patel and Tina Pasotra), researchers (including Lorraine Henry and Anjalie Dalal-Clayton), educators, students (Jess Raja-Brown), librarians (Nicholas Brown, Tate librarian) and curators (Tobi Alexandra Falade, members of Tate curatorial team). They gave their reasons for coming: to stimulate their creative practices, to learn more about this little-known history and to reconcile their memories of this period with the archive (Nina).

15

Panchayat study day at the Tate Library and Archive, Tate Britain, 23 September 2022. Photograph: Gustavo Grandal Montero

Everyone dispersed to explore the Panchayat archive. Across six tables in the Tate Library reading room at Tate Britain, Katie and Gustavo had spread out materials on:

Black artists (including Creation for Liberation catalogues from the early 1980s); education (including materials published by Inner London Education Authority [ILEA] and the Arts Education in a Multicultural Society [AEMS] Project);

HIV/AIDS (including information on the Naz Project, a sexual health service for Black and Asian communities in London set up by Shivananda Khan in the 1990s); and

Panchayat (including early mission statements and ephemera from the 1992 exhibition Crossing Black Waters).

There were also publications, ephemera and slides on the artists Said Adrus, Keith Piper, Samena Rana, Donald Rodney and Allan deSouza. Katie also took workshop participants into the stacks to see the full scope of the Panchayat archive.

After a coffee break, everyone presented an item from the archive which they had been particularly struck by: Nick showed a torn-out article from Third Text, and reflected on the intrigue of handwritten annotations and marginalia; Radha shared artworks by Said Adrus which addressed migration and racist violence; and Tina showed an article by Donald Rodney and Keith Piper on collaboration and racism in the art world. Marlene chose a letter from a Black art network in London about an event at the Equator Gallery in London Bridge, neither of which she had heard of. She shared her excitement about realising that there is an archive of the British black arts movement that exceeds what she lived through and was personally connected to. Alina chose posters produced by Allan deSouza at Copy Art; Lorraine chose a postcard of a work by Harold Offeh which resonated with her interest in Black masculinity; and Jess selected the ‘Crossing Black Waters Education Pack’, placing this in dialogue with a pamphlet on Thatcher and the suppression of leftist education in schools.

At the end of the workshop, participants and facilitators were left with a number of questions: how might we reconsider the geographical scope of the British black arts movement to acknowledge the transnational connections forged by organisations like Panchayat (who exhibited in Havana, Canada and elsewhere, as well as collecting materials on artists based in the USA, Canada and South Asia)? How does an unwieldy collection such as Panchayat prompt us to challenge the categories of archive, library, publication and ephemera? If the Panchayat archive has preserved materials which were usually thrown away, such as photocopied flyers, then how might we evaluate the aesthetic and political importance of disposable ephemera?

Report by BAN Member Alina Khakoo, a PhD student on the Criticism and Culture programme at Cambridge University, supervised by Priyamvada Gopal, Amy Tobin and Shamira Meghani.

16

Panchayat study day at the Tate Library and Archive, Tate Britain, 23 September 2022. Photograph: Gustavo Grandal Montero

EMMA ROODHOUSE

ON SEVEN YEARS OF LANDSCAPE RESEARCH WITH THE BRITISH ART NETWORK’S LANDSCAPE RESEARCH GROUP

In October 2016, myself and Jenny Gaschke, who was then at Bristol Museum & Art Gallery, started an email conversation about putting in an application to the British Art Network to launch a Landscape ‘subgroup’ (as the Research Groups were then known). There was no subgroup covering that topic and it seemed to us that there was a real need to bring people together for discussion. We had both been thinking independently about the relevancy of historic landscape collections in Suffolk and Bristol, how they had been collected, researched and displayed. Could we bring comparisons across the regions or what made them distinctive to their local area? Importantly, we felt there was a need for a group that could foster a connection between regional collections, help to provide support, promote knowledge exchange and offer opportunities to visit behind the scenes in other organisations.

That initial application was successful, and we started our focus on historic landscapes with events about geology in Bristol. Then we moved on to antiquarianism and topographical landscape in Ipswich and ended our first year by examining early landscape photography at the V&A. These events tended to focus on collections and bringing objects out from stores for discussion.

One of our members, Christiana Payne, Professor Emerita of History of Art, Oxford Brookes University, explains what was useful in those early days:

After a year with a growing membership, it became clear that we needed to expand our remit into modern and contemporary landscape as well as environmental art.

18

I thought it was a brilliant way to meet people from different sectors including curators and artists – it provided a very friendly and informal forum in which to exchange ideas. The visits to exhibitions (both real and virtual) were extremely useful for my own practice. The topics we discussed were very relevant and showed how important landscape studies are.

The growing interest in debate about the study of landscape art through an environmental lens was brought to the fore by the Paul Mellon Centre’s conference Landscape Now in 2017, which explored the breadth of approaches to landscape in British art. With the foundation of the Extinction Rebellion movement in 2018, there was an even greater emphasis on what role cultural organisations should play in this deepening crisis. This was also well timed for another round of application writing to the British Art Network to continue the group and it was clear that the focus now needed to shift to include these wider debates.

As we stated in our application:

These contexts would become even more pressing considering the looming pandemic, and social and economic developments. One of our last visits to an actual exhibition before the lockdown would be to Eco-visionaries: Confronting a Planet in a State of Emergency, at the Royal Academy in early 2020. This was a very timely reflection on how artists, designers and architects have responded to ecological breakdown. We were fortunate that Helen Record, former Assistant Curator of Collections at the Royal Academy, was also able to join myself and Jenny on the coordinating group. It was wonderful to be able to share the responsibilities of paperwork, events, mailings, coming up with new ideas, chasing

19

Installation view of Natural Encounters, Leeds Art Gallery, 9 October 2020

–20 February 2021

We hope to better understand British landscape traditions in a range of current contexts including the environment, empire and social identity.

speakers, finding venues and providing mutual support. There is a lot that goes on behind the scenes in running a research group.

As we all adapted to life in lockdown during 2020 and 2021 so did the Landscape group. We embraced the online format and hosted talks, informal discussions and hybrid events. It was a very busy time for me, Jenny and Helen as we juggled working from home, homeschooling and all the other life commitments. There were certainly times when I felt the pressure from all the continual juggling and I am very thankful to Jenny and Helen for keeping me motivated via WhatsApp, email or a Zoom call. You can read more about Landscape through lockdown in the British Art News August 2021, where we published a thorough overview of activity.

An unexpected outcome from this time was the opportunity to rethink our funding, which had just been used for events and travel. BAN was very supportive in allowing us to look at funding for commissions and we were able to support artist Siobhan McLaughlin to create an artwork immersed in the landscape and curator Kate Banner’s writing on lockdown. Since then the group has supported five more artist commissions. This potential use of the funds to create landscape art has been a highlight for me and created a tangible legacy for the group. It was certainly not an aspect I had thought about back in 2016 at the beginning of this adventure.

The seven years have been full of unexpected encounters with landscape art in Bristol, Bordeaux and Liverpool. It has increased awareness of the many ways landscape can be studied, made accessible and its central importance to our daily lives. I am hugely grateful to the British Art Network for the opportunities it has presented, and the lifelong friendships and joy that it has brought to the profession.

We will be holding an online discussion in May 2023 about the final group of commissions supported by the Landscape Research Group. They include artworks by Hayley Field, Alice Cunningham and Anna Dougherty. If you are interested in attending, please email emma.roodhouse@colchester.gov.uk

20

21

Thomas Churchyard (1798–1865), Ploughing, oil on board Colchester and Ipswich Museums Service: Ipswich Borough Council Collection (IPSMG:R.1913.2.2)

ON CO-CURATING A TALL ORDER! ROCHDALE ART GALLERY IN THE 1980S (TOUCHSTONES ROCHDALE, 4 FEBRUARY–6 MAY 2023)

In her landmark book, Differencing the Canon: Feminism and the Writing of Art’s Histories (1999), Griselda Pollock starts her chapter on Lubaina Himid with the following sentence:

Revenge was the title of an exhibition held at Rochdale Art Gallery in 1992 of A Masque in Five Tableaux by Lubaina Himid, an artist born in 1954 in Zanzibar and currently living in the north of England.

There is an intentionality in the way that Pollock locates Himid and her practice that is worth thinking about: Zanzibar, Rochdale, the north of England. All these places, in different ways, have been and indeed continue to be, regarded as marginal locations within the narratives of art’s histories. Anecdotally, Bryan Biggs of the Bluecoat, Liverpool, recently recounted how an art critic was aghast that for much of her career Himid was only able to secure exhibitions in regional galleries, as though spaces such as Rochdale Art Gallery or the Harris Museum and Art Gallery in Preston are ‘lesser than’.

During her career as Exhibitions Officer at Rochdale Art Gallery from 1981–1993, Jill Morgan worked hard to challenge such pervasive pejorative conceptions of the municipal, regional art gallery as somehow inferior to art institutions in the capital. At Rochdale, Morgan and her small and changing curatorial team, including Bev Bytheway, Sarah Edge, Catherine Gibson, Lubaina Himid and Maud Sulter, pioneered dynamic approaches to exhibition making, actively challenging the conventional parameters of who and what could be seen in the gallery. Morgan and her team didn’t look to London for validation but rather worked with locally and regionally based artists, curators, arts collectives and like-minded colleagues in other municipal galleries in the north of England. She also brought internationally recognised artists to Rochdale – Laurie Anderson’s exhibition and performance in 1983 being a notable highlight – working on the basis that meaningful, challenging, forward-thinking art could be found, and should be seen, in towns experiencing the profound challenges of deindustrialisation and social inequality.

22

ALICE CORREIA

23

A Tall Order! Rochdale Art Gallery in the 1980s is an exhibition curated by Derek Horton and me, working as freelance curators and funded by a Curatorial Research Grant from the Paul Mellon Centre for the Study of British Art. The exhibition is staged at Touchstones Rochdale and sets out to revisit, celebrate and simultaneously question what happened at Rochdale Art Gallery during the turbulent 1980s, and what, if anything, we might learn from the art that was produced during the decade, and how it was exhibited. Morgan’s curatorial foundation was that everyone should have access to the very ‘best’ art, and preparatory research for the exhibition revealed a dynamic and progressive approach to programming: that supported artists over significant periods of time; that actively engaged with performance, new media and popular visual culture; that gave artists of colour such as Juginder Lamba and Sonia Boyce solo exhibitions at a time when other galleries were siloing their work into tokenistic survey shows of ‘Black art’; that gave artists fresh from art school such as Pete Clarke and Sutapa Biswas the opportunity to show their work, and that their exhibitions were accompanied by illustrated catalogues as standard practice. The title of the show comes from Morgan’s description of the gallery’s ethos, written in a letter to a colleague in 1987:

Our policy is to encourage new audiences for art, particularly women, Black communities, young people, those with disabilities, and to encourage cultural activity for working class communities. Broadly, to change the domination of art by a white middle class male audience and producer. A tall order!

The exhibition fills all four of Touchstones’ Victorian galleries and includes the work of ninety-one artists. Artworks have been sourced from the Rochdale permanent collection, artist loans and loans from other public galleries and private collectors. Many of the works, including those by Terry Atkinson, John Hyatt and Lesley Sanderson, hadn’t been displayed for over thirty years. Managing the loans and transportation of such large numbers of works was a challenge for the small team at Touchstones, as was our desire to exhibit a slide-tape work by Anne Tallentire using a thirty-year-old projector in the age of ‘health and safety’. But the incredible efforts of the gallery’s staff, particularly those of Sarah Hodgkinson (Senior Curator – Exhibitions & Collections), were instrumental in bringing my and Derek’s curatorial aspirations to fruition.

24

Opposite: Gallery 1: Work and Labour (top) and Gallery 2: Land and Our Environment (below), in A Tall Order! Rochdale Art Gallery in the 1980s Photos: Harry Meadley, Courtesy Touchstones Rochdale

A Tall Order! reflects Rochdale’s engagement with ‘issue-based art’ and is organised thematically: Gallery 1: Work and Labour; Gallery 2: Land and our Environment; Gallery 3: Rochdale at the Heart of Everything; and Gallery 4: Power, Identity and Representation. The artworks in the exhibition fall into three main types: historic works from the eighteenth to early twentieth century; works made and exhibited at Rochdale Art Gallery during the 1980s and early 1990s; and recently made contemporary works by artists who are currently engaging with the legacies of the 1980s. Works from each of these categories can be found in each of the four galleries in order to generate cross-generational conversations, and indeed it is hoped that visitors will recognise a slippage between the thematic rooms: many individual works could potentially have been positioned in more than one gallery. The issues and socio-political events addressed by artworks included in the show range from: unemployment and unequal wealth distribution; industrial disputes; climate change and the built environment; military conflict and its consequences; the biases the print and broadcast media; and the place and representation of women in society. In our age of austerity, MeToo, BlackLivesMatter, calls to decolonise the museum and the climate crisis, the works in the exhibition feel urgent and relevant.

25

Gallery 4: Power, Identity and Representation, A Tall Order! Rochdale Art Gallery in the 1980s

Photo: Harry Meadley, Courtesy Touchstones Rochdale

A grant from Arts Council England enabled four commissions: Jade Montserrat, Sarah-Joy Ford and Lubna Chowdhary made new works for the show. For the fourth commission, we worked with the Estate of Donald Rodney and film-maker and curator Ian Sargent to restage and film Donald Rodney’s slide-tape Cataract (1990); we are delighted that in creating a digital film of this remarkable and little-known work by Rodney, we have also supported greater access to his work in the longer term.

It has been an incredible privilege working on this exhibition; for me, it has highlighted the lack of critical intersectional engagement with the 1980s within the field of British art history. It has been instructive to see the range and diversity of artists who showed at Rochdale: I’d argue that while postmodernism facilitated a greater appreciation and understanding of feminist, postcolonial, class-conscious work, A Tall Order! demonstrates that these positions didn’t exist in isolation; there was artistic debate across genders, sexualities, races, classes, and that these debates took on aesthetic as well as political concerns. A Tall Order! also tries to show how artists were simultaneously engaging and experimenting with the properties of their chosen medium: from the different painterly techniques of Glenys Johnson, Catherine McWilliams and David Alker to the narrative and abstract video work of Keith Piper and Maud Sulter, respectively.

I hope that this exhibition will help generate greater interest not only in what was happening in the artworld of the 1980s and how, but also stimulate a greater appreciation of where the most dynamic conversations were taking place. In doing we so, we can start reorientating, or in Pollock’s terms, differencing, the canon of ‘British Art’.

26

change, challenge and disruption’

AN INTERVIEW WITH SARAH VICTORIA TURNER, ACTING DIRECTOR,

PAUL MELLON CENTRE FOR STUDIES IN BRITISH ART

Sarah Victoria Turner is an art historian, curator and writer. Since 2013, she has been Deputy Director for Research at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art (PMC) in London and, in March 2023, she took up the role of Acting Director on the departure of Mark Hallett, who has been Director of the PMC since 2012. Sarah has taught art history at the University of York and the Courtauld Institute of Art. She is co-editor of British Art Studies, an awardwinning digital arts publication, and the co-writer and co-host of the Sculpting Lives podcast. In 2018, Sarah co-curated The Great Spectacle: 250 Years of the Summer Exhibition at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, with Mark Hallett. She is also the co-editor of The Royal Academy Summer Exhibition: A Chronicle, 1769–2018, an open-access and peer-reviewed digital publication consisting of texts by over ninety authors, which was the winner of the People’s Voice Webby Award (2019).

She co-leads the London, Asia research project with Hammad Nasar, Senior Research Fellow at the PMC. Together with Amy Tobin, they are curating an exhibition at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge on the artist Li Yuan-chia and the LYC Museum and Art Gallery he established in Cumbria in the 1970s. Much of her writing has focused on the entangled relationships between Britain and South Asia and she has published widely on this topic. She was a founding partner of the Leverhulme-funded Enchanted Modernities: Theosophy, Modernism and the Arts c.1875–1960 international network, and was also Co-Principal Investigator on the AHRC-funded Internationalism and Cultural Exchange c.1880–1920 network with Grace Brockington.

Sarah was a member of the British Art Network Steering Group from 2015–2022. From April 2023, she will be co-chairing the Group with Alex Farquharson, Director of Tate Britain. Here, Sarah discusses questions from BAN Convenor Martin Myrone about her career, curatorial engagements and the changing state of British art studies.

27 ‘

MM: You joined the Paul Mellon Centre in 2013. Given that your own career and experience has spanned the university, the PMC (a research centre and publisher), and museums and galleries with your various curatorial engagements, what would you say have been the key changes affecting the way art histories are explored and presented across these different contexts, over the last decade? Have there been changes in what, and how, the PMC supports research in British art?

SVT: Yes, most definitely – there have been significant changes in the last decade or so that have impacted the ways art histories are explored and presented. Key among these is what we might describe as a ‘digital turn’ that is having a radical impact not only on the way in which we access and process research, but also in how we communicate our findings to wider audiences, whether that’s through publications, podcasts, exhibitions or social media platforms for example. I’ve been involved with the PMC’s open access journal British Art Studies since it was founded in 2015. When we started the journal, we had to do quite a bit of persuading of potential authors that their work would be taken seriously online and that its academic credentials would be the same as a print journal. I never have those conversations now – the tone and concerns have completely shifted. Now, the conversations often turn to questions of how digital tools and methods can be incorporated into the published article – an interest in revealing how research is done and making resources, such as data sets or digitised archival material – available. I find these questions really energising as they are part of a larger conversation about opening up what we do as art historians, communicating it better and thinking conceptually and practically about our methods.

I started my career as a university lecturer in 2008 and since then I’ve witnessed quite seismic shifts in how British art is being positioned. Without any shadow of a doubt, this is all for the good! When I was a PhD student, there was often a defensive attitude about

28

The ‘British’ part of the British Art Network or the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art is no longer a descriptive term, but the site of a debate about the relationship of nation to history.

British art studies – an eagerness to demonstrate that is was somehow not inferior to its European neighbours. That feels like a bit of a redundant argument now. The pressures are bigger, more challenging, more urgent and more global. Questions about who and what has been excluded from the histories of art are now prominent concerns. Art historians who have grappled with the relationship of British art to the histories and politics of empire have made fundamental shifts to bring topics of nation, race, class and economics to the fore.

The ‘British’ part of the British Art Network or the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art is no longer a descriptive term, but the site of a debate about the relationship of nation to history.

Before you joined the PMC in 2013 you were Lecturer in History of Art at the University of York. Given that traditionally there has been quite an established ‘track’ within academic careers, could you share a bit about that decision, and also about your engagements with curating – which once upon a time might have seemed like departures from academic research?

I started teaching when I was at the Courtauld Institute of Art doing research for my PhD I had the incredibly good fortune to be asked to be the Teaching Assistant for Lisa Tickner’s new MA module on twentieth-century British art. Lisa constructed a course which engaged the student with approaches outside of the academy – whether that was the conservation work being carried out by the National Trust on the murals Stanley Spencer painted at the Sandham Memorial Chapel, the private collection of Nicholas Goodison, or the oral history project Artists’ Lives housed at the British Library. I loved the plurality of approaches Lisa exposed her students to – all connected by a critical question about how the histories of modern art had been constructed. Before that, I had studied for an MA in Sculpture Studies at the University of Leeds, in partnership with the Henry Moore Institute. That’s where I experienced research-led curating for the first time, and it was formative. I’ve never had much truck with a supposed separation between the academy and the museum. I feel that kind of division is pointless and separates an already small field. For me, what really matters is sharing research and constructing conversations around it. Now I think about it, most of the major research projects I have been involved with have had a public-facing output and exhibition making is an important way in which ideas and arguments can be given expression through objects. I’d never describe myself as a curator if someone asked me what my job was, but I like the idea of thinking curatorially.

It is clear from many of the projects you’ve been involved in and your personal statements, that you’re very committed to collaborative ways of working. How does such collaboration

29

sit in relation to more established ways of working – whether in a university setting or a museum context: is there a natural progression or are there tensions as well? I’m thinking of how, traditionally, both universities and museums have emphasised individual authorship –with the single-authored monograph or the curator’s name appearing alongside an exhibition. How do you make collaboration in research work?

Collaboration is really important to me, and I think I do my best work when working with others. I like the idea that research is about posing questions – and ones which are best approached from a multiplicity of perspectives. However, there is a friction between these methods and traditional academic systems of merit in which the single-authored monograph is prized most highly. And I’ve never written a single-authored book, so that probably says a lot! As an art historian, I’m interested in groups and networks of artists, so I think I’ve found a way of working that is also networked and thinks about artists and art works in relation. I also think it’s important to look outside of the discipline of art history. For the Enchanted Modernities: Theosophy, Modernism and the Arts c.1875–1960, I worked closely with musicologists, historians of religion, literature specialists and cultural theorists, and it was revealing how that opened up different channels of exploration of shared interests in how spirituality and mystical thought shaped cultural production in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

30

View of "Enchanted Modernities: Mysticism, Landscape & The American West" exhibition, Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art, Utah State University, 2014. Image Courtesy of the Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art

A lot of my work at the PMC has been about creating and supporting communities of researchers and of trying to foster dialogues across the field of British art. I’ve been involved with the British Art Network since its early days and have always been energised by my interactions with it. Of course, collaboration isn’t always easy! One of my longstanding collaborators, Hammad Nasar, often uses the example of the Tai-Chi-based exercise of ‘pushing hands’ – there is certainly energy, force and sometimes friction in any collaboration. But ultimately, I think any research or curatorial project is collaborative, always the work of many hands, and built on the ideas of generations that have come before us (even if we are rejecting them).

Your research has always focused on the complex cultural relationships between Britain and Asia, and one of your first publications is on E.B. Havell, Ananda Coomaraswamy and Indian art in Britain, c.1910–14 (Visual Culture In Britain, 11:2, 2010). Thinking back, what are the main changes that you’ve seen in your areas of specialism – oth around how Indian art is viewed from the perspective of British art history, and perhaps how approaches your period (late nineteenth–early twentieth century) have shifted?

It’s been an immense privilege to be part of a community of scholarship working on the entangled histories of Britain and South Asia. It’s meant that I’ve been working as part of an international network of research that has had a significant impact on how I think about British art. Giving papers about my research in India or at the Asia Art Archive in Hong Kong has helped me think about the perspective from which I research, write and speak, as well as the connections between historical material and contemporary politics. One of the main changes is that scholarship that is attentive to the histories and politics of empire is no longer in the footnotes of the histories of British art, but it now much more centrally focused on debates and projects. In my specific area of specialism, I’ve also seen the number of people working on the cultural relationships between Britain and South Asia grow in number. In terms of the late nineteenth-/early twentieth-century period I’ve focused on, it now seems unconscionable to reckon with the histories of modernism without attention to the geo- and cultural politics of colonisation. There’s been a turn from ‘reception studies’ – say of how Indian art was viewed and displayed in Britain – towards critical understandings of how imperialism structured collecting practices, museums and the methods and terminology of art history itself. It’s a lively, discursive area – there’s still much to learn and much work to be done.

Your current research focuses on Li-Yuan-chia (1929–1994), a Chinese artist who lived in China, Taiwan, Italy and Britain, where he spent the last twenty-eight years of his life, setting up the LYC Museum and Art Gallery in a house next to Hadrian’s Wall. His life

31

story obviously illuminates not only a ‘global’ story of art but also a lot about the regional and the non-metropolitan. – could you tell us more about the project and in particular how your research will be expressed in the exhibition project, which opens at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge in November 2023? Are there differences or special challenges in dealing with a globalised art history in the form of an exhibition, as opposed to academic research?

This project is the culmination of the London, Asia research project which I have co-led with Hammad Nasar at the Paul Mellon Centre since 2016 – again another collaboration and network that has sought to expand, enrich and disrupt histories of British art. Hammad and I co-organised, along with Lucy Steeds (University of Edinburgh), a symposium on the work on Li Yuan-chia and the LYC Museum, to accompany the Speech Acts: Reflection, Imagination, Repetition exhibition at Manchester Art Gallery (co-curated by Hammad and Kate Jesson), which was part of the Black Artists and Modernism project. There was a special energy in the room at that event and Hammad and I decided to develop an idea we had for a curatorial project on Li that could also speak to some of the larger themes we’ve been exploring through the London, Asia project –complex topics such as migration and diaspora, how to account for the local and global in dialogue, the figures who are not included in the histories of modern British art (despite, in Li’s case, living and working as an artist in Britain for over thirty years, and being highly regarded by his contemporaries), as well as issues of language, translation, understanding/misunderstanding. Li’s practice as an artist and curator and what he enabled at the LYC Museum & Art Gallery (exhibiting the work of over 300 artists in a decade) lays down a challenge to established or conventional methods – he was an experimental disruptor! The LYC Museum was established in some buildings that Li bought from fellow artist and friend, Winifred Nicholson in the early 1970s. Bringing Li and Nicholson together –not just biographically – but also within a history of art that takes seriously friendship as a creative act is one of our interests in curating this group show; it brings together Li’s work with some of the artists who were important to the LYC, as well as the work of contemporary artists who are interested in Li’s ideas and practices at the LYC. We very specifically didn’t want to curate a monographic exhibition with a few other artists for comparative purposes.

32

Li Yuan-chia, Untitled, 1994, hand-coloured black and white print. Digital image courtesy of LYC Foundation, Li Yuan-chia Archive, The University of Manchester Library. Photo: Vipul Sangoi. (British Art Studies, issue 12 - Fig. 20)

We’re staging this at Kettle’s Yard, which is part of the University of Cambridge. It’s now a gallery and museum space that was also a home to Jim and Helen Ede, so the coexistence of art and life is a strong thread. Several artists in the exhibition were connected both with Cambridge and Cumbria (and beyond!). It’s going to range from flower painting to experimental film-making and include artists from different parts of the world. The challenge of this exhibition is how to weave all these threads together and create a narrative and experience for audiences that inspires them to want to find out more. Many people will not have heard of Li Yuan-chia before.

The exhibition is research – of course, it’s different to a book, but we will have print and digital publications to accompany the exhibition, as well a busy programme of events. I really like how exhibitions offer a way to channel energy – you have to do a tremendous amount of practical work just to make them happen (the loan requests, the conservation, the framing, the writing of labels etc). Once the exhibition opens, that’s an invitation for others to build further on your work. I think exhibitions are very visible, tangible stepping stones for the histories of art.

In 2017, you initiated the ‘Write on Art’ competition, along with Art UK. This is aimed at 15–18-year-olds, and is designed to encourage an interest in art history among young people. We’ve heard a lot over the years about how art history has been viewed as a pretty exclusive subject for school students, and has arguably become only more so. At this juncture, how do you feel about the future of British art history? I do feel positive. There are undoubtedly huge challenges faced by our sector. But these challenges are shaking things up and asking us hard questions about the way things operate and are structured. I think the main thing is to be open to change, challenge and disruption.

33

THE COVER IMAGE

The cover image features the well-known painting of The Cholmondeley Ladies in the Tate collection, which features in the new displays at Tate Britain, opening fully in May 2023. It is the earliest historical work currently featuring in the British Art UnCanon, an online ‘virtual collection’ featuring works chosen by BAN Members. In the article, titled ‘Unrelenting Flatness and Wallpaper Symmetry’ , BAN member Janet Couloute argues that the work can be understood as ‘an early modern visual statement on that most enduring of Western ideals: Female aristocratic whiteness’. See the full article here.

If you have a proposal for a new article that you would like to produce for the UnCanon, please contact the BAN Convenor, Martin Myrone, on mmyrone@paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk.

CONTACTING BAN

For comments, suggestions and proposals for the British Art Network Newsletter, and for events or news for our News page, you can email BritishArtNews@paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk.

If you would like to become a BAN Member, please complete our Membership form. For general enquiries, you can email BritishArtNetwork@tate.org.uk.

You can also contact the British Art Network team directly: for contact details, see here. For more information on the British Art Network and all the Research Groups, including their contact details, visit the BAN website.

34

The British Art Network is supported by Tate and the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art, with additional public funding provided by the National Lottery through Arts Council England.

British School, The Cholmondeley Ladies c.1600–10. Tate T00069. Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported)

Curatorial tour of RISD, Providence, during the YCBA/BAN Curatorial Forum, October 2022

Curatorial tour of RISD, Providence, during the YCBA/BAN Curatorial Forum, October 2022