Key Dates in the Life and Career of Benedict Nicolson

This selective chronology focuses on the areas of Nicolson’s life represented within the Archive held by the Paul Mellon Centre

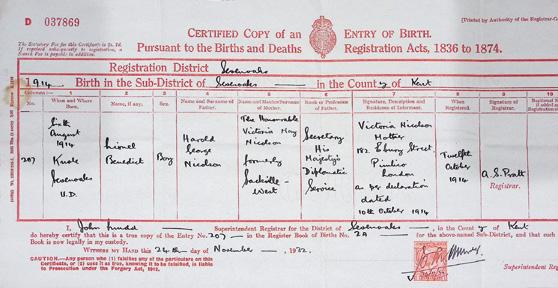

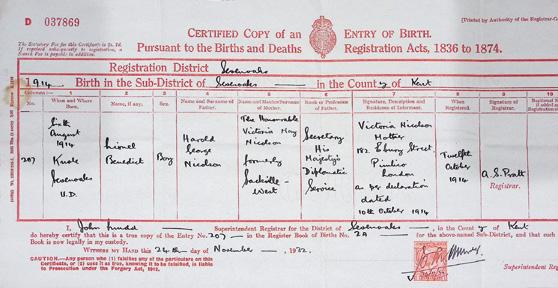

1914 Lionel Benedict Nicolson born at Knole on 6 August, the son of Sir Harold George Nicolson (1886–1968) and Victoria Mary (Vita) Sackville-West (1892–1962).

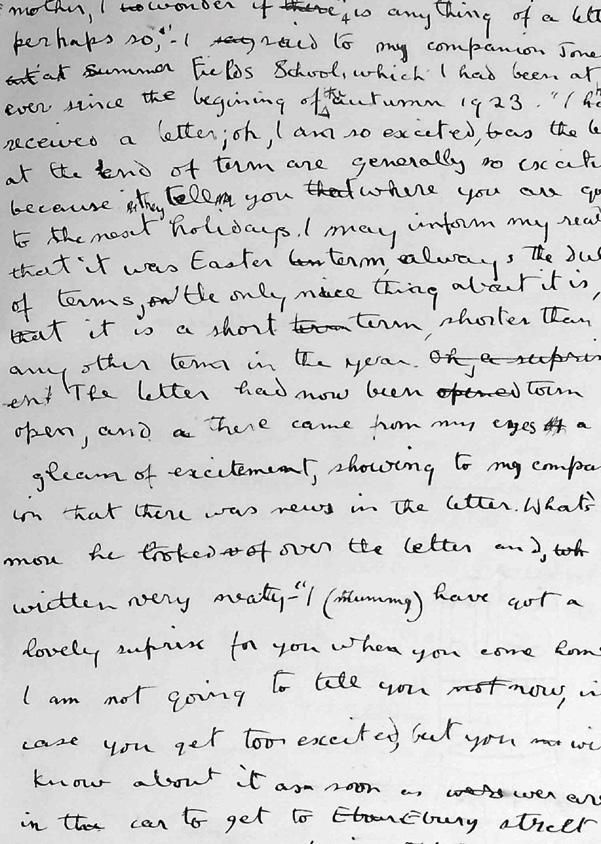

1923 Starts boarding at Summer Fields school, Oxford

1925 Visits Italy for the first time with his family

1928 Admitted to Eton College, Windsor

1930 Parents purchase Sissinghurst, a then run-down Elizabethan mansion in Kent, and set about restoring the house and gardens

2

1933 Enrols at Balliol College, Oxford

Begins his first detailed journal (1 January), which runs to eighteen volumes, and – with significant breaks – covers the period through to May 1970

1934 Co-founds ‘The Florentine Club’, a new student society for individuals interested in art and sculpture

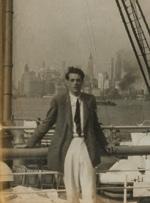

1935 Visits the United States, arriving with his father in New York on 1 August

1936 Comes down from Oxford with a second-class degree in Modern History

Visits Italy, the Netherlands and Germany to study the pictures in public and private collections

1937 Takes an unpaid role at the National Gallery, London (January–August)

Visits France and Italy to study the pictures in public and private collections

Begins an unpaid internship at I Tatti, under Bernard Berenson (November–December)

6 3

Item: 3 Item:

1938 Completes his internship at I Tatti (January–March)

Continues to study the pictures in public and private collections in Italy (April)

Visits the USA to study the pictures in public and private collections and take up an unpaid internship at the Fogg Museum (October–December)

1939 Completes his internship at the Fogg Museum and continues to study the pictures in public and private galleries in the USA (January–April)

Returns to England (April). Appointed Deputy Surveyor of the King’s Pictures under Kenneth Clark

Enlists in Victor Cazalet’s anti-aircraft battery at Chatham, Kent

1941 Publishes article, ‘Seurat’s La Baignade’ in the Burlington Magazine (no. 464)

1942 Transferred to Middle East, working for the Intelligence Corp as an instructor in interpreting military aerial photographs

1945 Invalided home after a road accident

Resumes his role as Deputy Surveyor of the King’s Pictures, now under Anthony Blunt

1947 Resigns from Royal Collection to take on editorship of the Burlington Magazine

Appointed MVO (Member of the Royal Victorian Order)

1948 Falls in love with David Carritt, then an Oxford student and later a successful art dealer; their troubled relationship breaks down in 1950

4

Item: 11

5

Hendrick Terbrugghen, The Lute Player.

Accession Number: PD.41-2010

Photograph copyright

© The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. Formerly owned by Nicolson

Castle, circa 1930s. Nicolson family collection

Photograph of Sissinghurst

1955 Marries Luisa Vertova, art historian and formerly an assistant to Bernard Berenson, at the Palazzo Vecchio, Florence (8 August)

1956 Birth of a daughter, Vanessa

1958 Publishes Hendrick Terbrugghen (Lund Humphries)

1962 Marriage with Luisa dissolved

Death of his mother, Vita Sackville-West; Sissinghurst becomes a National Trust property

1968 Publishes Joseph Wright of Derby: Painter of Light, 2 vols (Paul Mellon Foundation)

1971 Appointed CBE (Commander of the Order of the British Empire)

1977 Elected a Fellow of the British Academy

1978 Dies suddenly in London, following an embolic stroke, 22 May. Obituaries appear in Apollo (by Denys Sutton) and the Burlington Magazine (by Francis Haskell), noting he had ‘a genius for friendship’. The Times identified him as ‘one of the outstanding figures in the art historical world of the post-war years’ (26 May 1978)

1979 Posthumous publication of The International Caravaggesque Movement: Lists of Pictures by Caravaggio and his Followers throughout Europe from 1590 to 1650 (Phaidon)

2017 Benedict Nicolson Archive donated to the Paul Mellon Centre by his daughter, Vanessa

7

The Archive

Nicolson led an extraordinary life. Born into an aristocratic, but also liberal and bohemian family, and coming of age in the tumultuous interwar period, he encountered unprecedented opportunities and experiences. Accordingly, the Archive is perhaps the richest collection at the Centre in terms of its historical and social interest. Unlike other holdings, it was created and compiled almost exclusively in a personal, rather than professional, capacity. It includes only a small volume of material pertaining directly to Nicolson’s art-historical work despite his long and influential tenure as editor of the Burlington Magazine (1947–1978) and does not include any research information pertaining to Nicolson’s published articles and books. Despite this, the Nicolson Archive is a key acquisition for the Centre, supporting a central collecting policy aim: capturing the complex stories of how art history in Britain has been practised and developed.

Nicolson’s research notes relating to Joseph Wright of Derby are held at the Derby Museum and Art Gallery; his papers relating to John Hamilton Mortimer are part of the John Sunderland Archive held by the Paul Mellon Centre. The archive of the Burlington Magazine is held at the National Gallery.

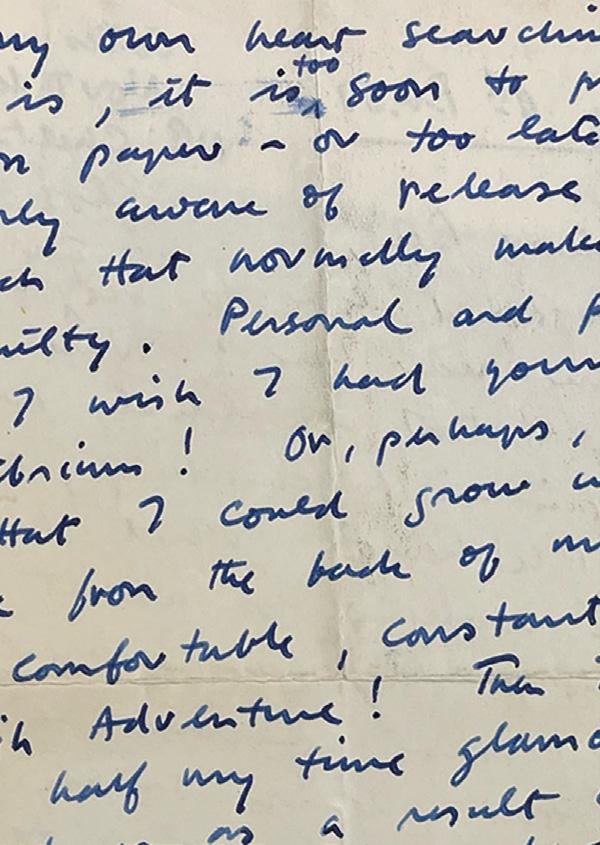

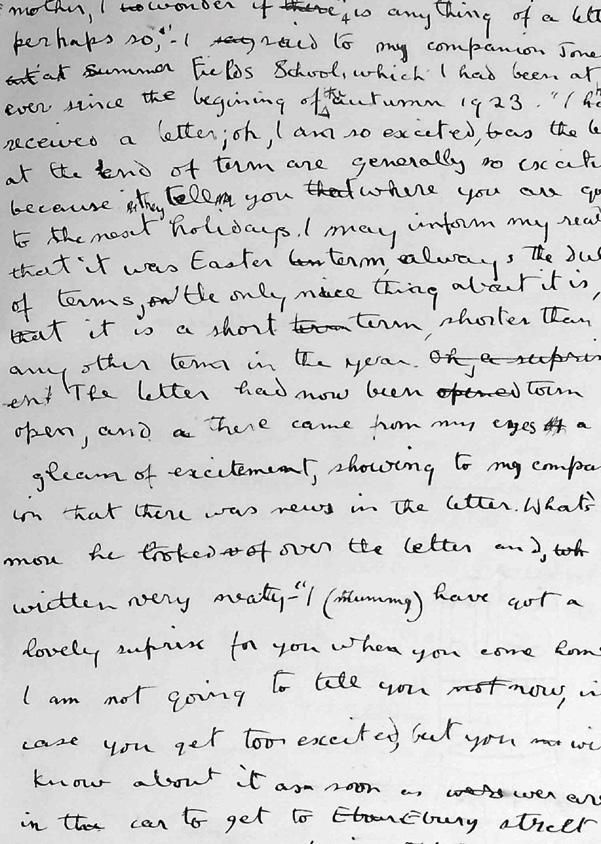

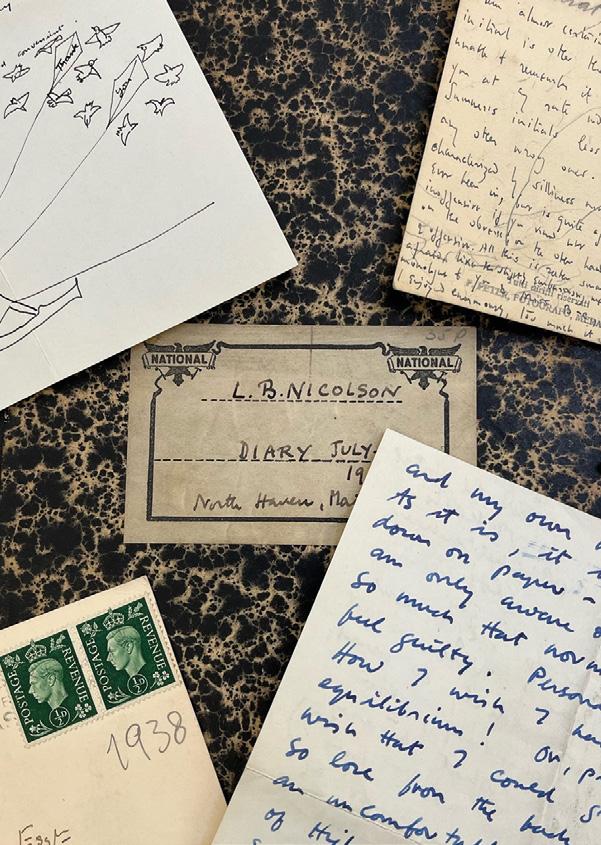

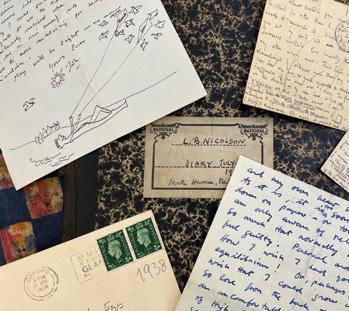

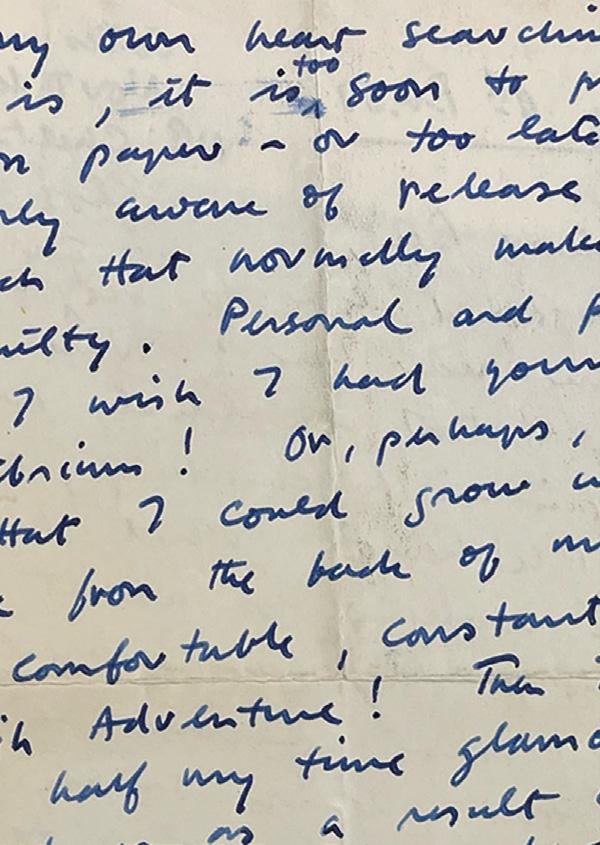

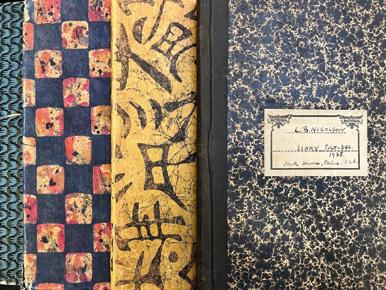

The Nicolson Archive is further unusual because most of the material was created by Nicolson himself. A series of eighteen journals sit at the centre of the collection. Aside from a single volume, compiled on a family holiday to Italy in 1925, these begin in earnest on 1 January 1933 and run consecutively for just over a seven-year period, until May 1940. Volumes from this time document formative years: his experiences as an undergraduate at Oxford and his attempts to pursue a career in art history directly afterwards. The archive contains three further journals covering the period 1943 to 1950, documenting Nicolson’s wartime and post-war experiences. A final journal covers the period 1968–1970.

8

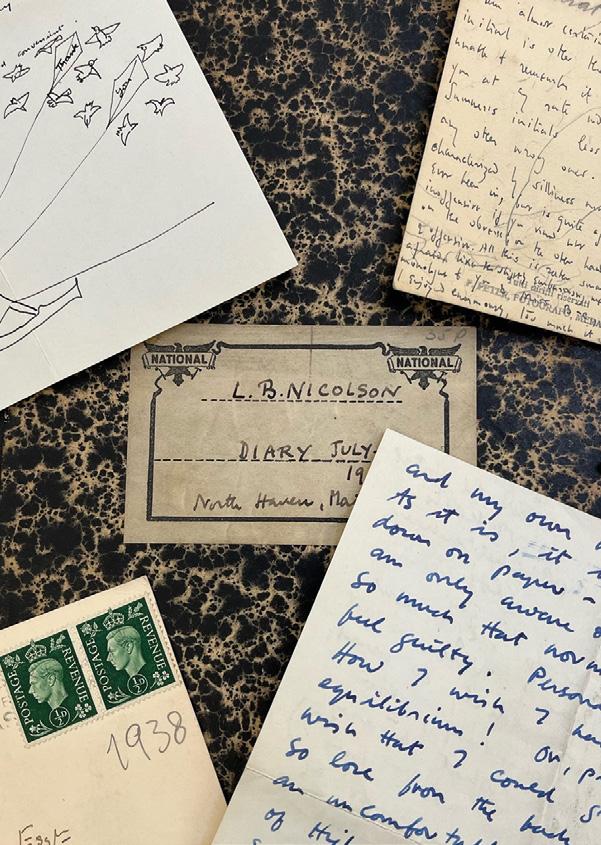

Three journals in the Nicolson Archive, Paul Mellon Centre

Nicolson’s journal entries are intelligent, fluid and generally expansive. They provide a personal, first-hand, behind-the-scenes commentary not only of the day’s events, but also his thoughts and observations on a wide range of topics. Turning the pages, one gains an insight into his beliefs (both conscious and unconscious) on subjects as varied as the arts, communism, fascism, class, women, sex and sexuality.

Bursting from the pages, too, are a huge cast of characters. Nicolson records in detail his interactions with, and observations on, both close friends and passing acquaintances. His writing is at times candid, but also kind. Reading the journal entries, which run from his formative years to early old age, we are made acutely aware of the human experience: love and loss, ageing, grief, passion and joy are all explored.

Alongside the journals, the archive also contains a significant volume of correspondence, much written by him and received by his family. This material includes not only letters to his mother, Vita Sackville-West, but also – perhaps most notably – those he sent to Luisa Vertova during their courtship.

9

There is also much correspondence received by Nicolson from a wide range of friends and acquaintances. This material reveals the relationships, often deeply complicated, with some of those who knew him best and enhances the journal entries, providing additional depth to incidents and events only mentioned in passing.

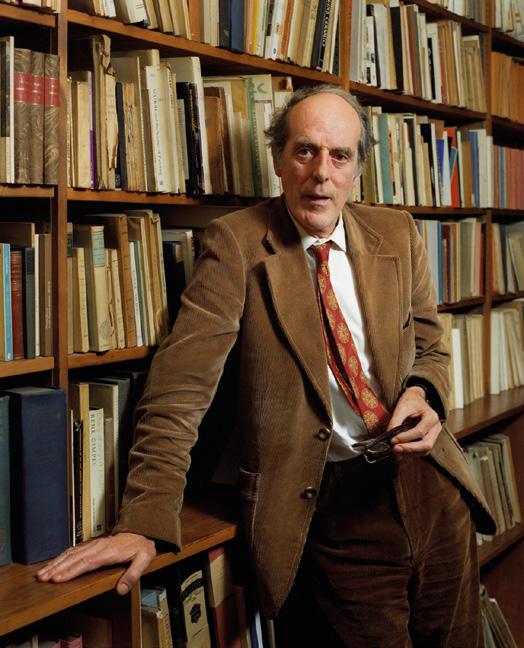

The archive reveals an extraordinary story. Nicolson himself emerges as a loyal friend, naïve in matters of the world, somewhat snobbish, inhibited but also social, and prizing intellectualism. As his obituarist in the Times remarked, he was a man of contradictions: ‘By turns kind and tactless, wily and innocent, taciturn and garrulous, humorous and solemn, he was always lovable and always unclassifiable’ (Times, 26 May 1978).

Correspondence envelopes in the Nicolson Archive, Paul Mellon Centre

10

Life and Times

Lionel Benedict Nicolson (always known as Benedict/ Ben Nicolson) was born into a wealthy and well-connected family. He was the son of Sir Harold George Nicolson (1886–1968), diplomat, historian, writer and from 1935–1945 a Member of Parliament, and his wife, Victoria Mary (Vita) Sackville-West (1892–1962), poet, novelist, biographer and gardener. Nicolson felt the weight of his heritage declaring in a journal from 1946 ‘I do not like being the son of great men and women. Any success one may have is unsatisfactory’, but was also aware that it had an immeasurable impact on his character and career.

UPRIGHT DISPLAY CASE

Left: Howard Coster, Vita Sackville-West, 1934, film negative, 25 x 30 cm.

© National Portrait Gallery London (NPG x12029)

Right: Howard Coster, Harold Nicolson, 1935, half-plate film negative.

11

© National Portrait Gallery London (NPG x24460)

Item: 1

12

Nicolson was sent to preparatory school, and then in 1928 to Eton, but it was not until he went up to Oxford that he began to flourish. Reading Modern History at Balliol College, it was here that he began to explore a growing interest in art and made lifelong friendships with some of the leading intellectual forces of the day. His social circle included Isaiah Berlin, Jeremy Hutchinson, Stuart Hampshire and John Pope-Hennessy (affectionately nicknamed ‘Botticelli’ throughout the archive).

Wolfgang Suschitzky, Sir John Pope-Hennessy, late 1960s, gelatin silver print, 25.3 x 30.3 cm. © National Portrait Gallery London (NPG x200743)

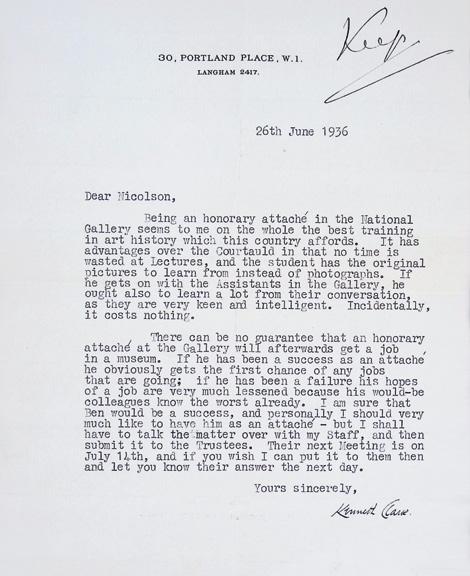

Coming down from Oxford in 1936, Nicolson’s wealth and connections enabled him to pursue a career in his favoured subject. Following advice from Kenneth Clark, a family acquaintance, rather than enrolling at the Courtauld Institute to pursue an academic course in art history, he sought to develop his knowledge by studying paintings in the public and private collections of Europe and America. To this end, he travelled extensively from 1936 until 1939.

13

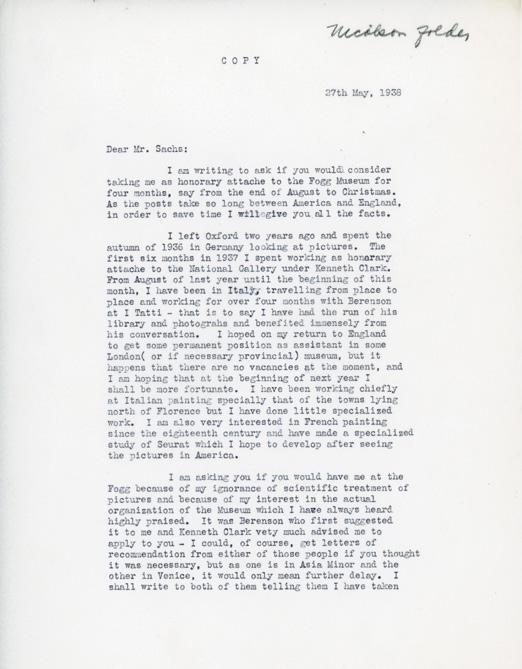

Alongside this independent study, Nicolson also undertook a series of unpaid positions: at the National Gallery (January–August 1937); at I Tatti, as the pupil of Bernard Berenson (November 1937–March 1938); and at the Fogg Art Museum, Massachusetts (October 1938–January 1939). During his periods at home, Nicolson continued to socialise with the people who he termed the ‘Smart Set’: attending balls, dinner parties and a variety of gatherings with the rich, famous and most influential individuals of the day. In April 1939, nearly three years after leaving Oxford, he took up his first paid position: Deputy Surveyor of the King’s Pictures under Clark.

Less than six months later, the outbreak of the Second World War forced Nicolson – alongside all young men of his generation – to reconsider his future. Leaning again on family connections, he enlisted in the new 83rd Light Anti-Aircraft battery founded in September 1939 by Victor Cazalet, a wealthy Conservative MP and art collector, and one of the gay or bisexual politicians referred to dismissively as ‘Glamour Boys’ by Neville Chamberlain. Cazalet’s outfit – a refuge for many literary and artistic individuals – soon became known as, in one colonel’s words, a ‘bugger’s battery’(Jessica Mitford, Faces of Philip: A Memoir of Philip Toynbee, 1984).

Nicolson went on to obtain a commission in the intelligence corps and by 1942 had been transferred to the Middle East where, making use of his detailed eye for images, he worked as an instructor in interpreting military air photographs. He remained in this role until being invalided home after a serious road accident, in March 1945.

14

Howard Coster, Kenneth Clark, Baron Clark, half-plate film negative, 1937. © National Portrait Gallery London (NPG x10829)

By June 1945, Nicolson resumed his work as Deputy Surveyor, now under Anthony Blunt. Despite enjoying regular visits to the king and queen, Nicolson was never a natural courtier. He was perhaps relieved to resign his official functions in 1947 when he was invited – largely at the instigation of Herbert Read and Ellis Waterhouse –to edit the Burlington Magazine.

On 8 August 1955, Nicolson married Luisa, daughter of Professor Giacomo Vertova of Florence, herself a distinguished art historian and a previous assistant to Berenson. Nicolson had never hidden his sexuality from Luisa – it had been disclosed in a ‘sealed letter’ from Nicolson in 1953 – but, there were difficulties in their relationship, almost certainly aggravated by Luisa’s homesickness (having relocated from Florence to London). A daughter, Vanessa, was born in 1956, but the marriage was dissolved in 1962.

Item: 13

15

Subsequently, Nicolson had brief relationships with men, but the Burlington Magazine remained the central interest of his life: he transformed a periodical ‘suffering from post-war intellectual rationing and lack of direction into a publication of worldwide respect’ (editorial, Burlington Magazine, February 2004). Throughout his career, he also produced several significant art-historical studies including most notably books on Joseph Wright of Derby: Painter of Light, The International Caravaggesque Movement, and studies of Seurat and Courbet.

Nicolson was awarded several official accolades including, in 1977, election as a fellow of the British Academy. Nicolson died very suddenly at the age of sixty-three on 22 May 1978, having collapsed from an embolic stroke in a London underground station as he was returning from dining at his club. Following cremation at Golders Green, his ashes were buried in his parish at Sissinghurst Cemetery.

Item: 18

16

Item: 22

Becoming an Art Historian

The Centre’s primary reason for acquiring the Nicolson Archive was the insight it provides into the art-historical world of the interwar and post-war periods. At a time when the subject could not be studied as a stand-alone qualification at any British university (the Courtauld Institute was a fledgling institution and the Warburg had just transferred to London), routes into the field were far from obvious.

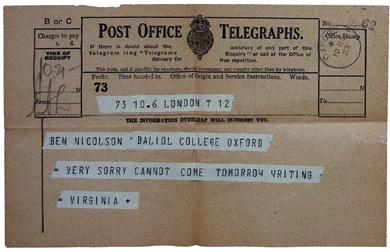

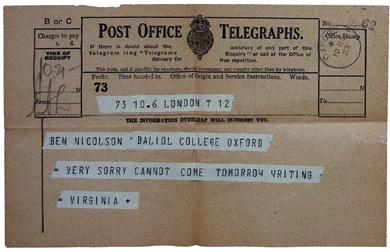

Nicolson came from a literary and cultured background, so it is perhaps no surprise that he developed an interest in painting and sculpture. His family’s wealth and connections were also invaluable in fostering his engagement in the field. His mother, Vita Sackville-West, had close connections with the Bloomsbury Group – not least a ten-year relationship with Virginia Woolf. Other members, including Duncan Grant and Clive Bell, were close family acquaintances and many had developed independent friendships with Nicolson.

Courtesy of The Society of Authors as the Literary Representative of the Estate of Virginia Woolf

LARGE FLAT DISPLAY CASE

17

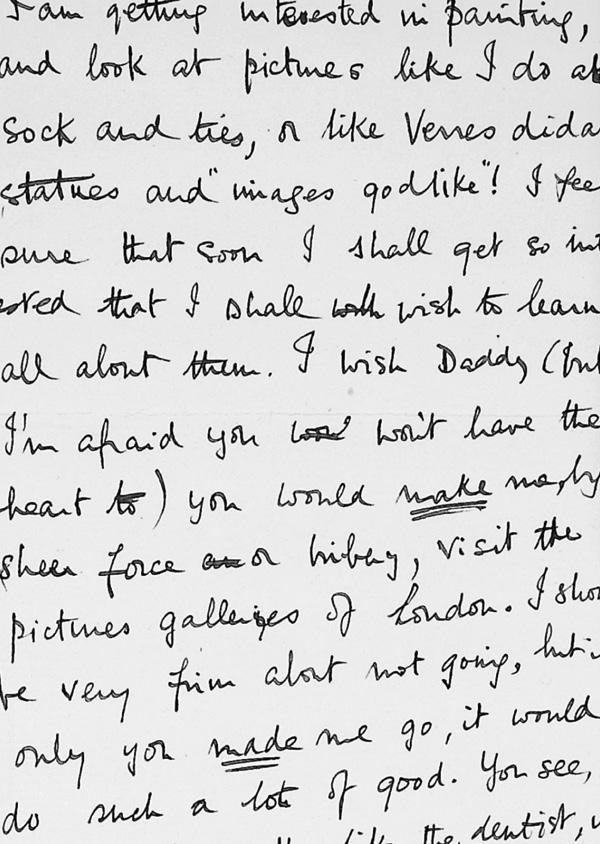

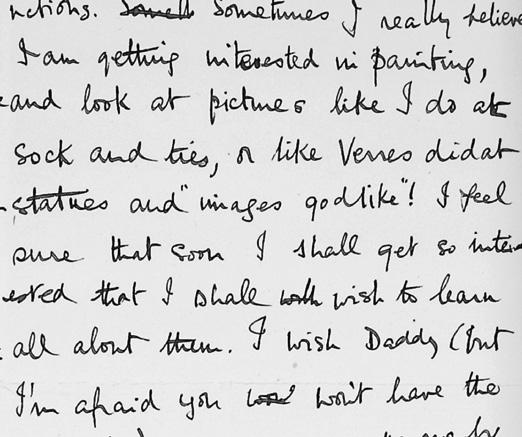

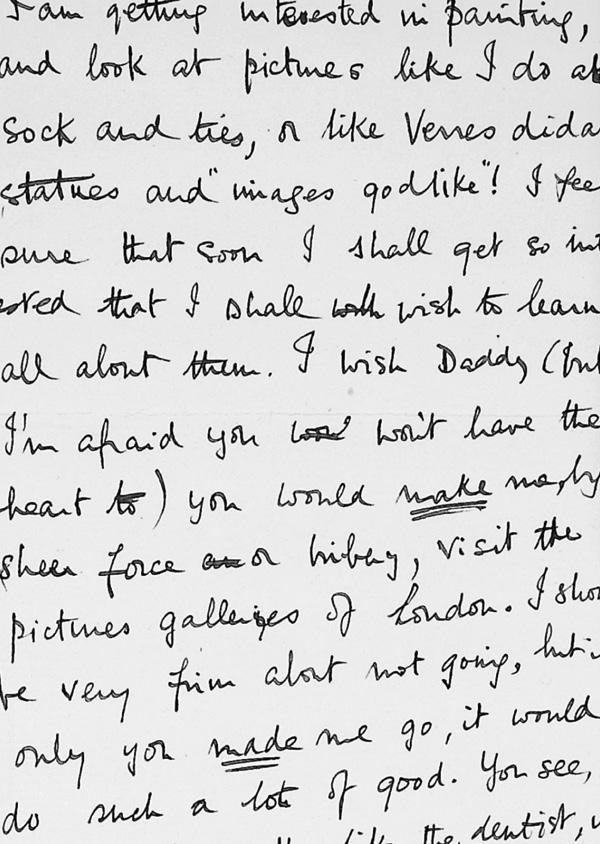

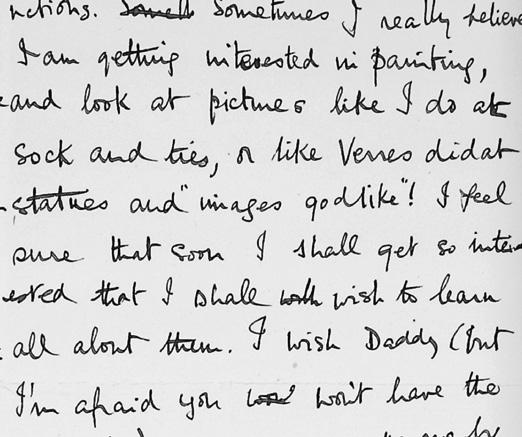

The earliest journal in the Archive dates from 1925 and was written when Nicolson was on holiday with his family in Italy. This was his second trip abroad and the experience – at the time out of reach for all but the most wealthy – began a lifelong love of both Italy and art. Letters in the archive, sent to his parents from boarding school, reveal this growing fascination and by 1930 –when Nicolson was just fifteen – his concern is so keen that he emphatically declares ‘I feel sure I shall get so interested [in pictures] that I shall wish to learn all about them’. (Item 21)

Item: 26

Detail from Item 21 18

When the journals resume in 1933, they reveal that Nicolson was already engaging in some of the activities that provided the foundation for his career as an art historian. The entry for 19 May of that year is the first time that Nicolson records a visit to a temporary exhibition: an exhibition of the sculptor Jacob Epstein at the Leicester Galleries in London. In a period when images of art were less prevalent and connoisseurship and viewing in-person were considered essential for anyone interested in the field, visiting exhibitions was the main way of gaining art-historical knowledge.

Nicolson’s diaries are crowded with such entries: from 1933 to 1939 over one hundred exhibition visits are recorded. Many of these were made during fleeting trips to London from his parent’s home in Sissinghurst or from Oxford – in some instances, Nicolson saw up to six exhibitions in a single day. The commercial galleries he frequented range from the well-established such as Tooth’s, Agnew’s and Knoedler’s to newer initiatives including the Lefevre, Mayor and Zwemmer Galleries, which focused on modern art. Nicolson’s entries provide a personal account of his impressions: they also provide a useful record of the works on display and reflect the trends and tastes of the time

Alongside temporary exhibitions, Nicolson also studied pictures in museums and galleries away from the UK, across Europe and in the United States. Following the family holiday in 1925, the journals record a second visit to Italy in June 1933. The purpose of this trip was to learn the language and prepare for going up to Oxford, but the entries also reveal a continuing interest in painting. Further entries from the following year record visits to institutions closer to home: Tate Gallery (14 March) and Ashmolean Museum (16 May). This pattern –visiting galleries in the UK during term time and travelling further afield during university breaks – continued throughout Nicolson’s time at Oxford.

19

Although not available as a formal academic course of study, while at University, Nicolson was able to pursue his art-historical interests through talks, clubs and societies. In particular, in 1934, together with fellow students, he founded the Florentine Club, an initiative where members with an interest in painting and sculpture could hear talks by critics and artists. The club was short-lived (the last meeting held in 1936) but attracted a number of influential speakers – mainly through the connections of its members – including family friends Kenneth Clark, Raymond Mortimer and Clive Bell.

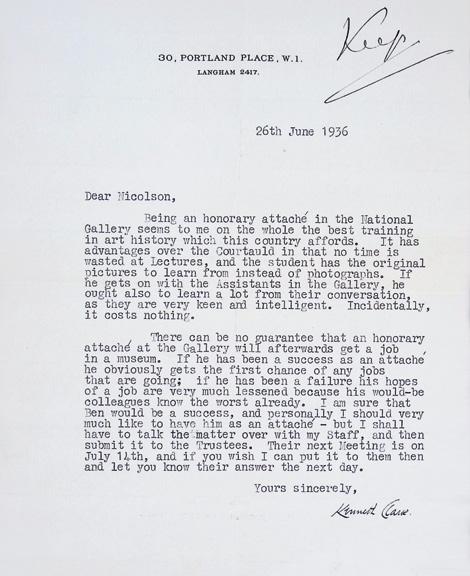

Coming down from Oxford in 1936, Nicolson was unsure how to advance his interest in the field; it was at this point he wrote to Kenneth Clark (then Director of the National Gallery) for advice. Although Nicolson considered enrolling at the Courtauld Institute of Art, which had been founded in 1932, Clark’s advice was unequivocal: an unpaid internship would provide the ‘best training in art history this country afford’ (Item 24). Since no such position was immediately available, Clark recommended in a subsequent letter that Nicolson ‘visit as many galleries as possible and look at all the pictures you like as long as possible’. Letters in the archive sent to Nicolson from John Pope-Hennessy – then an aspiring art historian himself and later Director of both the V&A and the British Museum – further emphasise the importance placed on studying paintings at first hand. In a letter from 1936, when Pope-Hennessy himself was studying pictures, ‘The only thing I feel quite certain is one should look on oneself as obliged to look at every single picture in whatever gallery one is doing’.

20

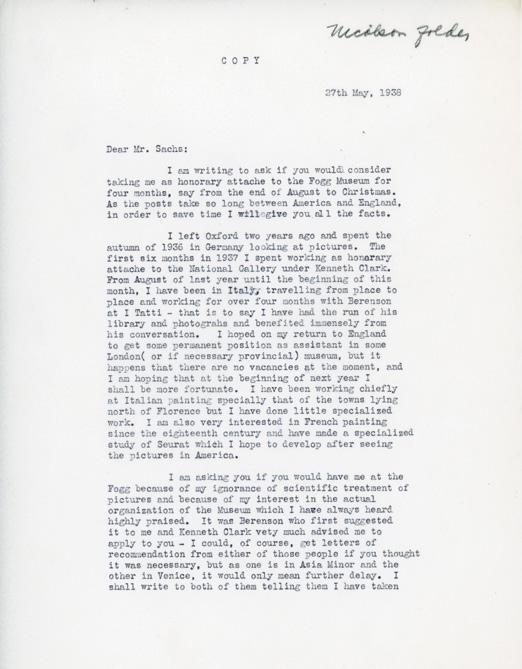

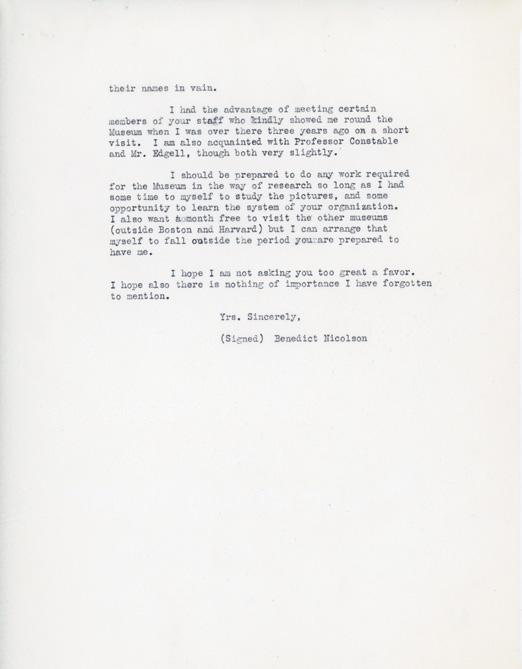

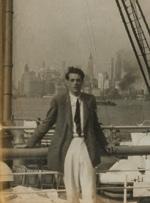

Taking this very much to heart, Nicolson spent the next three years following this advice. He had made his first visit to the United States in 1935 combining the activity of studying paintings in public and private collections, alongside social and sightseeing engagements. Nicolson now began to travel exclusively for art-historical purposes, spending extensive periods in Italy, the Netherlands and Germany in 1936; in France and Italy in 1937; and in the United States again in 1938–1939. Following a six-month honorary attaché position at the National Gallery in 1937, two of these visits also included periods of unpaid work – first at I Tatti (1937–1938) and then the Fogg Museum (1938–1939).

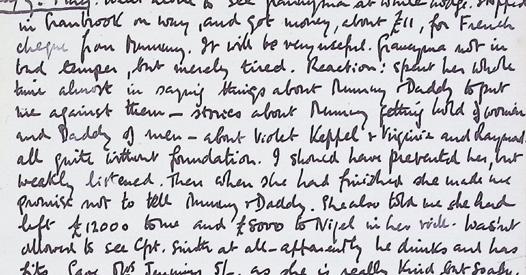

Edward Waldo Forbes and Paul J. Sachs with Auguste Rodin’s bust of Victor Hugo (1943.1033) and Francois Boucher’s drawing Reclining Nude (1965.235). Photograph by George S. Woodruff, 1944. Fogg History Photographs, Fogg Benefactors, folder 2. Harvard Art Museums Archives, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

30 21

Item

Returning to the UK in 1939, Nicolson finally secured his first paid position as Deputy Surveyor of the King’s Pictures under Clark. His career as an art historian was interrupted by the Second World War, but when hostilities ceased in 1945 material in the archive reveals that he was already an established figure in his field, regularly working alongside many of the most influential individuals including Anthony Blunt and Ellis Waterhouse (see item 32). In the final months of that year, journal entries record that he is on the committee for the selection of pictures for the Royal Academy Summer Exhibition (September); has given his first lecture at the Courtauld (November); and is part of an official delegation to review war damage to museums and galleries of Italy (December).

In 1947, Nicolson secured the post of editor of the Burlington Magazine and his journals in the archive cease shortly afterwards. He went on to produce several key publications and at the time of his death, nearly thirty years later, he had become known for the methodical approach and direct engagement with paintings which had been central to his training. Nicolson, then, can perhaps be counted as one of the ‘clerks’ of art history who, as Hans Hönes notes in his article in Issue 24 of British Art Studies , helped established the discipline in Britain in the mid-twentieth century. Nicolson’s archive, focused on the interwar and post-war period of the Second World War, not only presents a unique and detailed record of some of the great collections of Europe and the New World, but it also reveals much about the networks, landscape and practices of the newly emerging field.

22

Item: 24

Item: 24

23

Courtesy of the estate of Kenneth Clarke

Letter from Benedict Nicolson to Paul J. Sachs, May 27, 1938. Edward Waldo Forbes Papers (HC 2), folder 1498. Harvard Art Museums Archives, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA.

24

25

Left and above: front and back of Item 29

Detail from Item 36

Detail from Item: 32

26

SMALL

Other Narratives: Queer Histories in the Archive

Alongside its obvious value to scholars of art history, the Nicolson Archive presents a rich resource for researchers outside the field. As we follow Nicolson from cradle to grave through his photographs, journals and correspondence, a myriad of further narratives are revealed. The items in the third display case explore just one of these concerns: gender and sexuality.

Coming from a family of writers and diarists, it is perhaps unsurprising that so much of the material in the Nicolson Archive is personally revealing, including regarding his own relationships with both men and women. When we first meet him, through letters sent to his parents as a young child at school, there are oblique references to his unconventional upbringing. Nicolson’s parents practised what would today be called an open marriage, entailing multiple relationships with both women and men. Although prosecution for adultery was still possible in the UK until 1970, and sex between men remained a crime until 1967, such unconventional personal liaisons were not unusual in the social circles in which the couple mixed. Indeed, Harold and Vita had connections with the Bloomsbury Group of writers and artists, whose rejection of bourgeois habits and Victorian ideals, famously saw them engaged in a complex tangle of relationships.

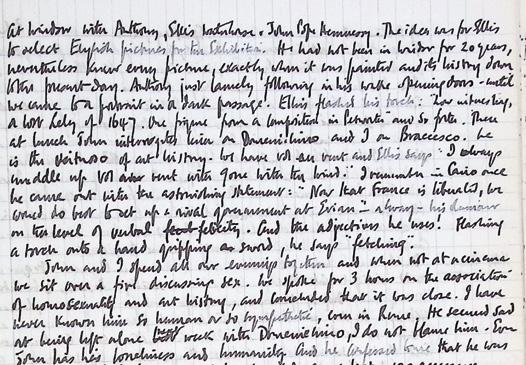

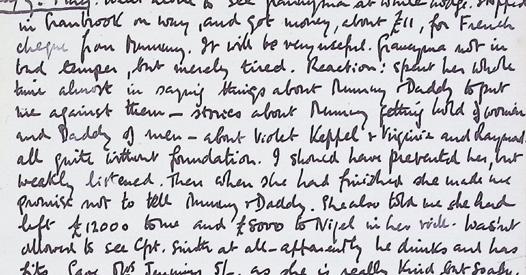

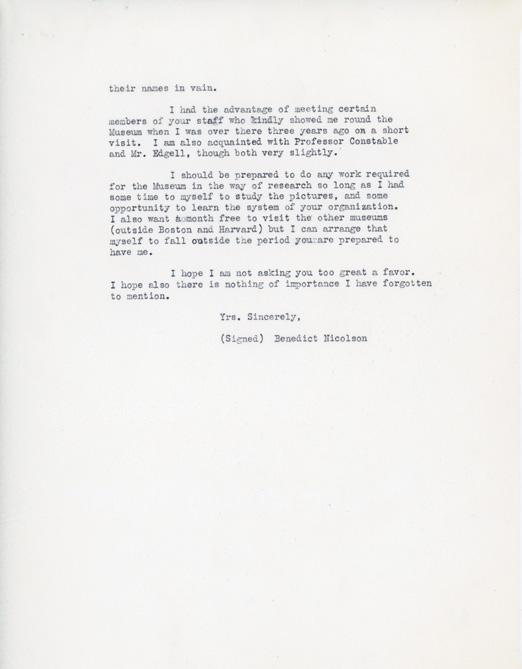

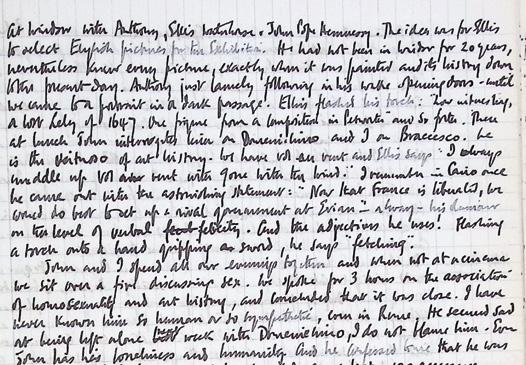

Nicolson’s childhood letters regularly reference some of these partners, but it is not until he is nineteen that he becomes aware of their significance. In the journal entry for 9 March 1933, he records that ‘Grannyma was telling stories about mummy getting hold of women and Daddy of men, about Violet Keppel, Virginia and Raymond. All quite without foundation’ (Item 36). The entry for the following day – written in parentheses – records that his mother has confirmed the stories: ‘she liked being frank with us’. The archive does not record Nicolson’s immediate reaction to this news, but the impact of his upbringing on his own life and identity is a subject he regularly returns to throughout the material.

FLAT DISPLAY CASE

27

Nicolson begins to write about his own sexuality as an undergraduate at Oxford later the same year. From this point forwards, the archive includes regular references both to his personal experiences, and those of friends. The subject is explored through private reflections, conversations with friends (see Item 32) and particular episodes, such as the brief love affairs he records with Eleonora Thomson and Laura Bonham-Carter in the 1930s. The richest material relates to the three significant relationships documented in the archive. In 1948, Nicolson embarked on his first real love affair with a student still at Oxford, David Carritt. Journal entries from this period are beautifully written, reminding us of the ecstatic highs and desperate lows of intense liaisons. They also reveal a man exploring the landscape and language of his sexual identity. As the relationship begins to falter, Nicolson is supporting his best friends, Philip and Anne Toynbee, through the breakdown of their marriage. The two stories are entwined, prompting regular reflection on the nature of relationships, and as both reach their painful conclusions in 1950, the journals symbolically cease.

From this date and for the next three years, the archive includes little documentation. In 1953, there is an explosion of material as Nicolson begins a relationship with his future wife Luisa Vertova, an art historian then working with Berenson at I Tatti. They conduct an extraordinary courtship almost entirely via correspondence, exchanging deeply personal and incredibly moving letters. Many of these, following Nicolson’s declaration in 1953 that he is a ‘congenital homosexual’, include frank discussions of the practical, emotional and sexual elements required for a successful marriage. The correspondence is a testament to their genuine devotion.

28

Item: 39

29

A final relationship – with a young aspiring town planner – seems to have prompted Nicolson to resume his journals in 1968. By this time, he is in late middleage and more at ease with his sexual identity. Entries record his personal reflections on the nature of relationships and sexuality, the impact to him personally of the Sexual Offences Act of 1967 and matter-of-fact accounts of his milieu.

30

Alongside Nicolson’s personal experiences, we also learn much from the voices of his contemporaries. The archive includes correspondence from the highly cosmopolitan and artistic group of individuals who confided in Nicolson about their own personal circumstances; coming from a wide social circle these often concerned complex relationships.

The archive reveals Nicolson as an individual who loved deeply and was deeply touched by his relationships. Above all, the papers present a very human story: through the loves, hates and passions of a single man, we are reminded of the universal human experience.

Campaign for Homosexual Equality rally, held in Trafalgar Square, 2nd November 1974. Image courtesy of Hulton-Deutsch Collection / Corbis via Getty Images

31

List of Exhibits

Item 7

Four envelopes from letters sent by Nicolson to his parents as a child, Item 1 circa 1922 – 1930

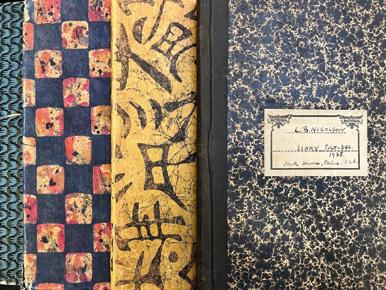

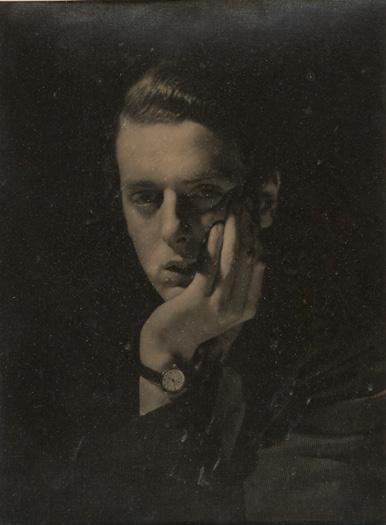

Print of a photographic portrait of AR: TN3 Nicolson by Howard Coster, 1934

Kindly lent by Vanessa Nicolson

Item 2

Print of a photographic portrait of Nicolson by Bern Schwartz,

1977

Item 8

Eton College school report for Nicolson, 1930

AR: TN4

Item 9

Photograph of Nicolson at Sissinghurst, Kindly lent by Vanessa Nicolson

Item 3

Birth Certificate of Lionel Benedict

Nicolson,

1932

Kindly lent by Vanessa Nicolson

Item 10

Two envelopes from letters sent to Nicolson 1914 as an undergraduate at Oxford,

AR: TN1 1935

AR: TN5

Item 4

Sketch of Nicolson as a toddler,

Item 11 holding Italian flag, probably by

Postcard of Nicolson in uniform, Nicolson, sent to Jeremy Hutchinson, undated 1939

AR: TN2

Item 5

Photograph of Nicolson aged three

Kindly lent by Vanessa Nicolson

Item 12

Three envelopes from letters sent to at Knole, Nicolson while serving in the armed forces, 1917 1940 – 1941

Kindly lent by Vanessa Nicolson

Item 6

Photograph of Nicolson, aged 11/12,

AR: TN6

Item 13

Photograph of the wedding of Nicolson to 1936 Luisa Vertova, Kindly lent by Vanessa Nicolson

1955

Kindly lent by Vanessa Nicolson

32

Item 14

Photograph of the christening of Vanessa Nicolson, circa 1956

Kindly lent by Vanessa Nicolson

Item 15

Two envelopes and a postcard sent to Nicolson in his roles as Deputy Surveyor of the King’s Pictures and editor of the Burlington Magazine, circa 1939–1950s

AR: TN7

Item 16

Copy of the Burlington Magazine, Issue 543, published shortly after Nicolson took up post as editor, June 1948

AR: TN8

Item 17

Photograph of Nicolson and others looking at a picture (possibly selecting works for an exhibition), circa 1960s

Kindly lent by Vanessa Nicolson

Item 18

Photograph of Nicolson holding a copy of the Burlington Magazine, circa 1960s

Kindly lent by Vanessa Nicolson

Item 19

Copy of an address given by Kenneth Clark at Nicolson’s funeral, 1978

AR: LBN/3/3

Item 20

Journal written by Nicolson, on his first visit to Italy, 1925

AR: LBN/1/1

Item 21

Letter written by Nicolson to his father in which he references his growing interest in art, 1930

AR: TN9

Item 22

Telegram from Virginia Woolf to Nicolson, cancelling an arrangement to meet, 1933

Kindly lent by Vanessa Nicolson

Item 23

Journal written by Nicolson, January – June 1934

AR: LBN/1/4

Item 24

Letter written by Kenneth Clark to Nicolson, advising on how to pursue a career as an art historian, 1936

AR: LBN/2/11

Item 25

Reproduction of Howard Coster, Kenneth Clark, Baron Clark, half-plate film negative, 1937

© National Portrait Gallery London (NPG x10829)

33

Item 26

Framed photograph of Nicolson arriving in New York, 1935

Kindly lent by Vanessa Nicolson

Item 27

Journal written by Nicolson, July – December 1935

AR: LBN/1/7

Item 28

Three envelopes from letters sent to Nicolson in each of his three internships (at National Gallery; I Tatti and Fogg), 1937–1938

AR: TN10

Item 29

Letter from Benedict Nicolson to Paul J. Sachs, May 27, 1938. Edward Waldo Forbes Papers (HC 2), folder 1498. Harvard Art Museums Archives, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

Item 30

Edward Waldo Forbes and Paul J. Sachs with Auguste Rodin’s bust of Victor Hugo (1943.1033) and Francois Boucher’s drawing Reclining Nude (1965.235). Photograph byGeorge S. Woodruff, 1944. Fogg History Photographs, Fogg Benefactors, folder 2. Harvard Art Museums Archives, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA

Item 31

Journal written by Nicolson, September – December 1938

AR: LBN/1/12

Item 32

Journal written by Nicolson, April 1945 – July 1948

AR: LBN/1/16

Item 33

Sir Anthony Blunt, art historian and advisor to the National Trust, stripped of his knighthood in later life after being exposed as a soviet spy, stands in front of a portrait of Balthasar Carlos, 1962.

Image courtesy of Express / Stringer / Hulton Archive / Getty Images

Item 34

Reproduction of a photograph of John Pope-Hennessy, by Wolfgang Suschitzky, late 1960s,

gelatin silver print, 25.3 x 30.3 cm.

© National Portrait Gallery London NPG x200743

Item 35

Photograph of Ellis Waterhouse, circa 1940s,

image courtesy of the Birmingham Post Studios

AR: PMC/22/3/2

Item 36

Journal written by Nicolson, January – June 1933

AR: LBN/1/2

Item 37

Page of a draft letter written by Nicolson to David Carritt, in which he explores the difficulties in their relationship, circa 1948

AR: LBN/2/10

34

Item 38

Transcript of the entry for 8 July 1948, written by Nicolson, in his journal of that year

AR: LBN/1/16

Item 39

Two photographs of David Carritt, circa 1948

AR: LBN/2/10

Item 40

Envelopes from letters sent from Luisa Vertova to Nicolson during their courtship, circa 1950s

AR: TN11

Item 41

Page of a letter sent by Luisa Vertova to Nicolson, following receipt of a ‘sealed’ letter, 1953

AR: TN12

Item 42

Reproduction of an image of a Campaign for Homosexual Equality rally, held in Trafalgar Square, 2nd November 1974.

Image courtesy of Hulton-Deutsch Collection / Corbis via Getty Image

Item 43

Journal written by Nicolson, December 1968 – September 1970

AR: LBN/1/18

Item 44

Letter written by Julia Strachey to Nicolson, 1947

AR: LBN/2/29

Item 45

Photograph of Julia Strachey sent to Nicolson, circa 1947

AR: LBN/2/29

Item 46

Clip from the BBC Omnibus documentary film Virginia Woolf: A Night’s Darkness, A Day’s Sail, first broadcast on 18 January 1970

35

Further Reading

Bryant, Chris. The Glamour Boys: The Secret Story of the Rebels Who Fought for Britain to Defeat Hitler. London: Bloomsbury, 2020.

Bury, J.B. ‘Benedict Nicolson’.

Burlington Magazine 120, no. 909 (1978): 850.

Elam, Caroline. ‘Benedict Nicolson: Becoming an Art Historian in the 1930s’.

Burlington Magazine 146, no. 1211 (February 2004): 76–87.

Haskell, Francis. ‘Benedict Nicolson and the Burlington Magazine’.

Burlington Magazine 119, no. 889 (1977): 229–30.

Hönes, Hans C. ‘The Rise and Fall of the “Clerks”: British Art History, 1950–1970’.

British Art Studies, Issue 24,

https://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-24/hhones.

Nicolson, Nigel. ‘(Lionel) Benedict Nicolson’. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography 2004), revised online 2008.

https://www.oxforddnb.com/.

Nicolson, Vanessa. ‘“I Never Loved Her ...” Ben Nicolson on his Mother, Vita Sackville-West’.

Times Literary Supplement, 4 November 2022.

Shone, Richard ‘Benedict Nicolson: A Portrait’ Burlington Magazine 146, no. 1211 (February 2004): 88–97.

Sutton, Denys. ‘Benedict Nicolson: A Notable Editor’. Apollo, 1 July 1978.

A full bibliography of Nicolson’s published work can be found in Luisa Vertova, ‘Ben Nicolson’. Firenze: Pitti Arte E Libri, 1991.

36

Acknowledgements

The Paul Mellon Centre extends special thanks to Vanessa Nicolson for her continued support with all activities surrounding the Benedict Nicolson Archive, in particular generously loaning objects for this display. Thanks are also extended to Megan Schwenke and Ashley Barrington for their assistance with identifying and providing images related to Nicolson’s internship at Fogg Museum.

Display contents and text compiled and selected by Charlotte Brunskill, with assistance from Martin Myrone and Clare Barlow.

Display and booklet coordinated by Bryony Botwright-Rance, with assistance from Daisy Dickens and Nida Shah.

Display and booklet designed by Carl Middleton www.carlmiddleton.co.uk

The Centre is confident that it has carried out due diligence in its use of copyrighted material as required by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (as amended).

If you have any queries relating to the Centre’s use of intellectual property, please contact: copyright@paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk

For more information about our research Collections see our website: www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk. Alternatively contact us by email at collections@paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk or phone 020 7580 0311

Item: 2

Bern Schwartz, Benedict Nicolson, 1977, dye transfer print, 28.2 x 22.3 cm.

© National Portrait Gallery London (NPG x P1222)

Item: 2

Bern Schwartz, Benedict Nicolson, 1977, dye transfer print, 28.2 x 22.3 cm.

© National Portrait Gallery London (NPG x P1222)

Item: 24

Item: 24