Catalogue essay by Dr. Ashley Busby November 19, 2022 - January 12, 2023

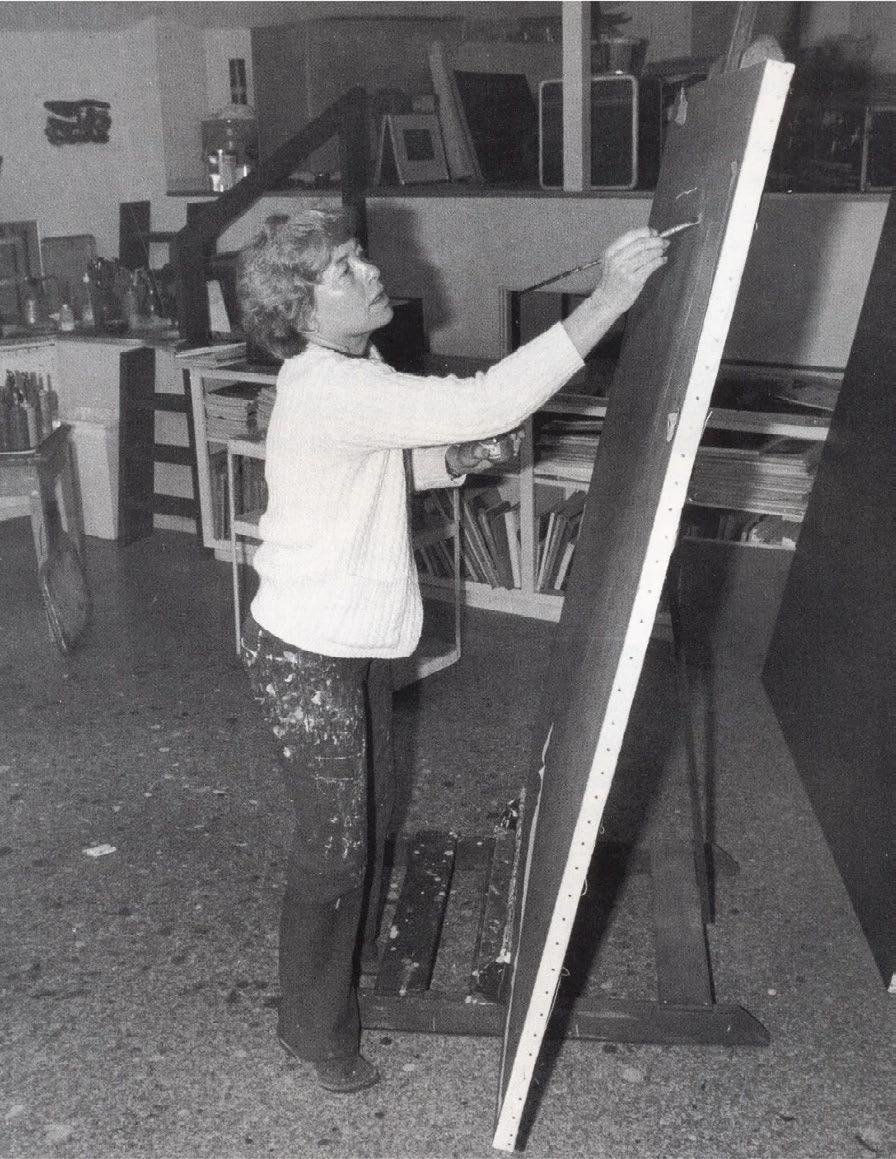

Dorothy Fratt. Photograph by Geny Dignac, © Dorothy Fratt Estate

Dorothy Fratt. Photograph by Geny Dignac, © Dorothy Fratt Estate

Catalogue essay by Dr. Ashley Busby November 19, 2022 - January 12, 2023

Dorothy Fratt. Photograph by Geny Dignac, © Dorothy Fratt Estate

Dorothy Fratt. Photograph by Geny Dignac, © Dorothy Fratt Estate

Born in 1923, post-war abstractionist Dorothy Fratt came of age in the D.C. art world. She received her degree from Mount Vernon College and studied at the Phillips Gallery of Art School, where she trained under Karl Knaths and Nicolai Cikovsky. en, in 1958 when her then-husband was transferred to Phoenix, Arizona as a part of his work for the Bureau of National A airs, Fratt packed up her art supplies, along with her four young sons, and made the trek west. Phoenix was, at the time, a cultural backwater disconnected from the east coast art world—a town better known for its connections to a then “cowboy-art” aesthetic.i Despite early di culties nding an enthusiastic audience for her abstract work, Fratt eventually found her stride. Her new home in the West provided the artist with a rich landscape and a distinctly desert-inspired palette to enliven and fuel her life-long exploration of color and space.

Dorothy Fratt: Paint e Town Red marks the return of the artist’s work to her hometown of Washington D.C. in a rst solo outing since a 1948 exhibition held at the United Nations Club Gallery.ii Featuring over 30 works, visitors have an opportunity to see both the artist’s early training in D.C. institutions alongside later work, completed after her move west. is mini-retrospective o ers a unique opportunity to view the artist’s evolving approach over time. Previously unexhibited works from the artist’s estate reveal Fratt’s early experiments with abstraction. Equally rewarding is the opportunity to view the artist’s more well- known abstractions in conjunction with her gural studies, watercolors, and other landscapes. e exhibition’s title refers not to bacchanalian carousing but rather her riotous and inventive handling of color, shape, and mark-making in her work. e exhibition seeks to invoke a spirit of celebration as we closely observe Fratt’s joyous approach to abstraction.

Dr. Ashley Busby

Installation view, Dorothy Fratt: Paint e Town Red. Photograph by Gregory Staley.

Installation view, Dorothy Fratt: Paint e Town Red. Photograph by Gregory Staley.

Dorothy Fratt was the daughter of Hugh Miller, who served as chief photographer at the Washington Post from 1934 until his retirement in 1969. She showed early skill as an artist, and her parents encouraged her work. When she was fteen, Fratt won rst prize in the Corcoran Gallery Student Show for her work Red Shoe (1938). is diminutive canvas features a red pump comprised of bold planes of color. Deep brick red tones alongside a showy vermillion—a color that Fratt often returns to in her oeuvre—create a shoe that is at once a series of attened planes and a curving three-dimensional form. Bold swaths of blue, yellow, greens and umber enliven the surrounding ground plane. Here, in such an early work, Fratt demonstrates her skills as a colorist along with an unabashed exploration of plane, shape, and form to create a compelling depiction of an otherwise everyday object.

Following her early success, Fratt went on to study at Mount Vernon College. She married in 1943, not long after completing her two-year degree from the the then junior college. After the war, her husband enrolled in law school, and the artist supported the couple by teaching art history classes at her alma mater, all the while seeking to establish her career as a working artist.

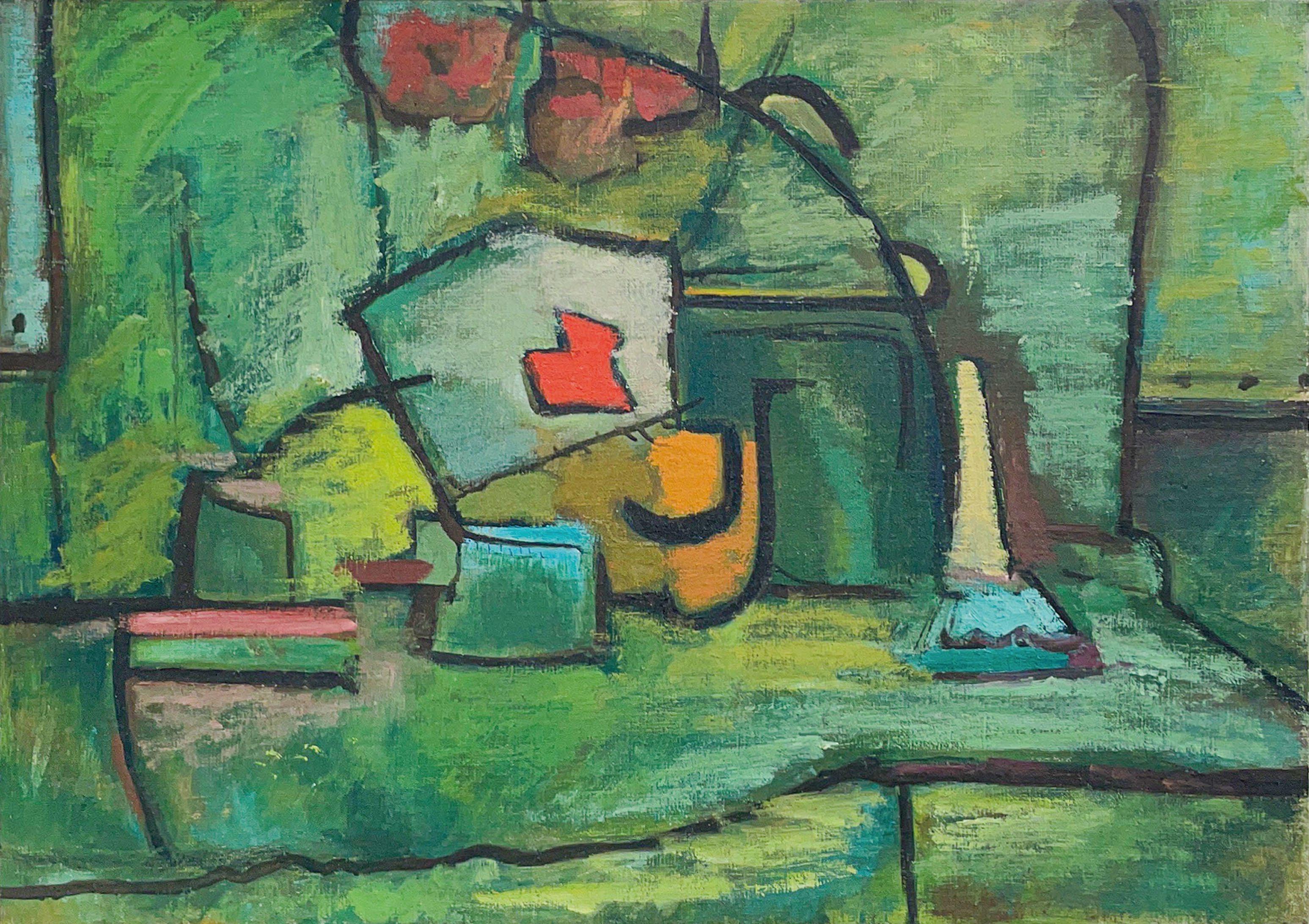

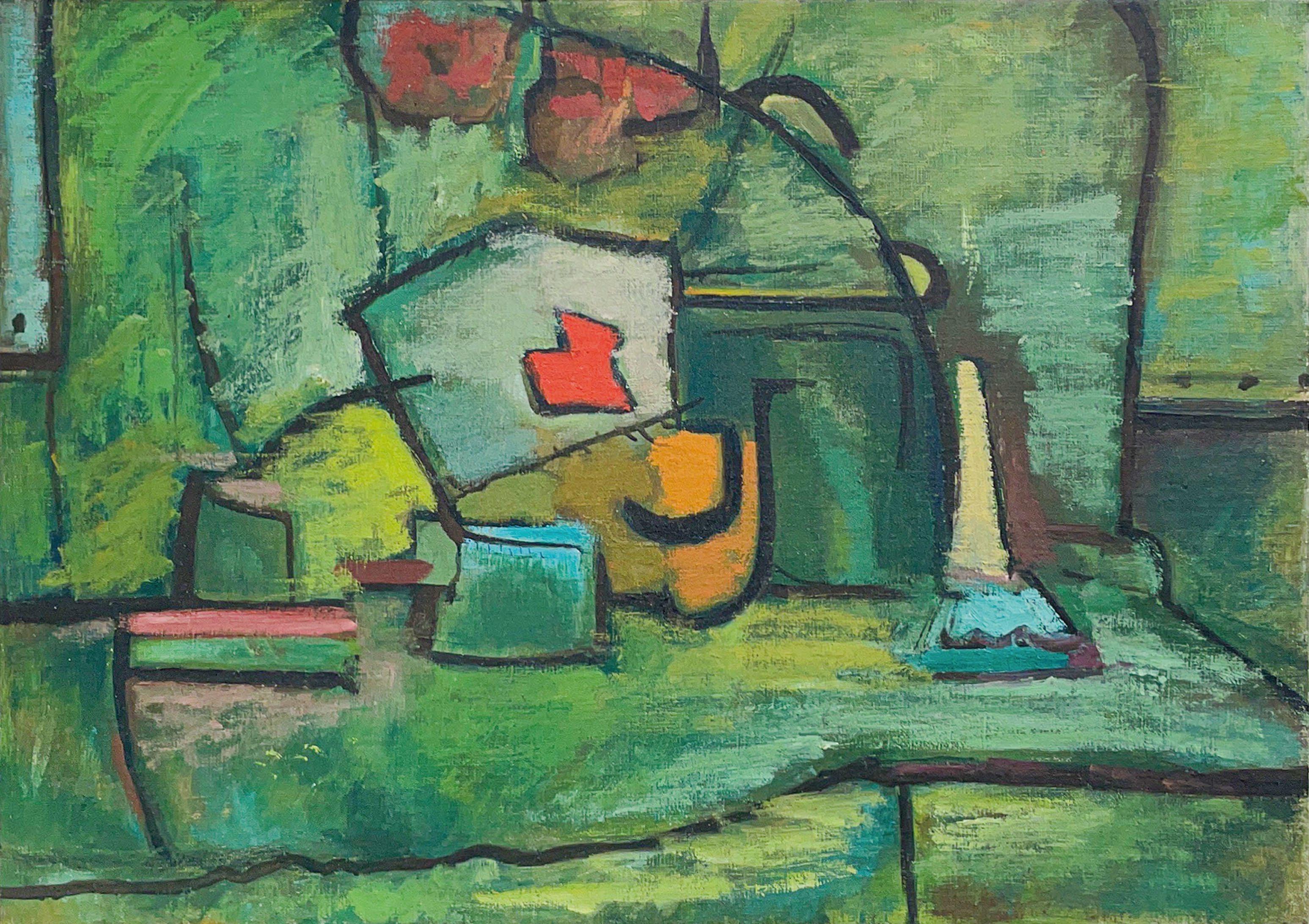

Her rst solo exhibition, in 1946, at the Washington D.C. City Library, featured, as she recalls, her “charming paintings” including park scenes and portraits. But in the years that followed, Fratt would both leave behind those pleasant compositions and pursue additional professional recognition and training. She competed for fellowships at both the Corcoran and the Phillips. After receiving o ers from both institutions, she ultimately chose the Phillips, where she studied with Nicolai Cikovsky and Karl Knaths. Fratt’s work from these years, especially her Co ee Break in the Washington Post Sta Room (1948), closely resembles Knaths’ cubist-inspired aesthetic.

Here, she experiments with planar forms and space as well as an abstracted approach to her subject matter. In her time at the Phillips she also completed commissioned portraits of Duncan Phillips’ niece and nephew, further embedding her in the D.C. art world.

Red Shoe, 1938, Oil on canvas, 6 x 8 in, © Dorothy Fratt Estate

Red Shoe, 1938, Oil on canvas, 6 x 8 in, © Dorothy Fratt Estate

While Fratt would eventually leave behind the bold outlines and overlapping planes redolent of her teacher’s approach, it was Knaths’ interest in color theory that had the greatest impact on the young artist. Scholars on Knaths note that his papers included copies of work by a diverse range of earlier twentieth-century abstractionists, including Kandinsky, Mondrian, and Malevich, as well as more contemporary artist/theorists such as Hans Hofmann.iii Malevich’s subtle, oating squares, all in the pursuit of a sort of universal harmony, have much in common with Fratt’s later optical experiments with color and space. And, Hofmann and his “push and pull” approach bear a striking comparison to the spatial complexities seen in much of the artist’s oeuvre.iv Fratt noted that in her time with Knaths, he also exposed her to German chemist Wilhelm Ostwald’s publications on color theory. In his early primer on color, he posited models and drawings of a color solid or space achieved through the selective arrangement and use of color.v Such considerations of the spatial potentials for color serve as an additional spring board for her move toward wholly non-objective work.

Untitled (1947), a small, oil on canvas painting, shows Fratt’s early move away from objective representation. e division of the picture plane into a pink and gray ground creates the illusion of a horizon, likely drawn from her earlier work in landscape. Red gestural marks oat above quickly rendered yellow and blue concentric circles. e work explores shape, mark-making, and the kinds of color elds and interactions that were at the heart of more celebrated abstractionists of the era such as Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko. In a later interview, the artist recalled that celebrated D.C. gallerist Franz Bader was dismayed by her continued work in abstraction. In response to his dismissal and refusal to exhibit her work, Fratt simply replied, “Yes, this is what I’m doing. I don’t know why but I’ve got to walk down this road, that’s all I know. It may be a complete dead end, but I’ve got to do it and see if there’s anything there.”vi

After moving to Phoenix in 1958, Fratt navigated the demands of family life while seeking to establish a foothold in a Phoenix art scene that saw her work as an oddity. In the rst several years after the move to Phoenix, she maintained summer studio space at the Phillips, returning to the city to paint while her parents assisted with the children. ose summer trips allowed Fratt to see work from her abstractionist peers in the city and to maintain a connection, albeit tenuous to the pulse of abstraction on the east coast. By 1962, Fratt had separated from her rst husband. To support herself and her young family, she took on students teaching painting and color theory to area artists as well as commissioned and commercial work in portraits, sumi drawings, and advertising. Her output over the course of the 1950s—when she rst began her family—and the 1960s comes in ts and starts. She noted that she would do the commissioned work and ads at night after putting the boys to bed then rise early to produce her “real paintings” with the bene t of the bright Arizona light.

Despite such challenges, Fratt’s continued exploration of color and abstraction are evidenced by Maria Laach (1962) a small acrylic on paper work that includes brash, gestural planes of color in blue, black, and a muddied cadmium with sweeping white marks to create circular shapes. Such experiments with paint application and mark-making can be broadly compared to her gural, commissioned work from the era, such as a set of sumi drawings produced for the Phoenix symphony. In Phoenix Symphony Conductor #1 (1960), Fratt uses simple strokes of varying weight to de ne her subject. By varying pressure and the amount of pigment on the brush for each mark, Fratt depicts a gure that is a study in contradictions: tense yet uid, quiet yet commanding. Despite such distinct purposes and outcomes in these two works from the early 1960s—one abstract, the other gural; one creative, the other commissioned—we see the artist’s continued emphasis on technique and formal qualities in her work.

In 1972, Fratt married Curtis “Bud” Cooper, and the two moved her family to a house that Cooper had built in 1969 on the ridge of Camelback Mountain just north of Scottsdale, AZ. Designed by Paul Yeager, a student of Frank Lloyd Wright, the home featured soaring open windows that o ered amazing views of the city below and the surrounding landscape. e artist’s son, Greg Fratt, notes that after his mom married Bud, life became easier.vii She no longer had to take on students or commissioned work simply to make ends meet and was able to truly focus on the abstract work that she so loved. She spent the rest of her life in Arizona and would continue to paint until the early 2000s.

In work from the 1970s and later, Fratt develops a signature mode that blends her earlier preoccupation with mark-making and color with a new, more purposeful integration of spatial e ects. Many works also incorporate visible references to the landscape and guration despite a largely

non-objective approach. Fratt’s position in histories of abstraction is deeply complicated. Her location in the west a orded her few opportunities, until recently, to exhibit her work outside regional institutions. And, while she certainly stayed abreast of the latest trends in abstraction and the larger art world, she dismissed any and all critical labels, refusing to be known as a Color Field Painter, a Hard Edge Painter, or even a member of the Washington Color School. When pushed to describe her work, Fratt once said, “It’s like trying to describe yourself when you’re looking in the mirror—it’s impossible. ey are and they’re not color eld paintings. ey’re minimal in some ways, but not in others. I don’t t into any category. I don’t think that’s unfortunate, but it’s unfortunate for people who like other people to t into categories.”viii

Despite such a disavowal of labels and critical stewardship, Fratt’s work certainly bears an easy comparison to her Washington D.C. peers in abstraction. e 1965 exhibition Washington Color Painters at the Washington Gallery of Modern Art, from which the Color School derived its name, included the work of just six artists. Still, expansionist histories of the movement now recognize a diverse range of artists and approaches as a part of the style, from Anne Truitt’s sculptural columns of color to Sam Gilliam’s draped, stained canvases. What unites these artist’s work is their turn away from the expressive potential of gesture and paint application seen in the early New York School and their focus instead on the optical potential of bold, clearly de ned areas of at color. Such a focus on color makes Fratt an easy t within an expanded roster for the Washington Color School. As master printer and collaborator John Armstrong argued, her work certainly ts within the color eld, but, unlike artists in D.C. “her paintings were sensitive in color, shape, and edge re ecting her intellectual involvement and understanding of the Southwest.”xi us her body of work re ects both an awareness of and experimentation with similar approaches to her

D.C. based contemporaries, further emboldened and impacted by her location in the west.

Unlike most of her Color School peers, however, Fratt’s work emphasizes the optical potential that lies not in a celebration of the inherent atness and two-dimensional nature of the medium but rather in work that investigates color as a means to force a sensation of space. As Fratt described it, she seeks to create “a kind of katty-wampus space not restrained by geometry.”xii Take, for example, I Owe You (1997); here, Fratt chooses one of her signature red grounds, arranging several colored shapes and marks across the canvas. A swooping, gestural slash, in a subtle, lighter value of the hue used for the ground, creates a dizzying, ickering e ect for the viewer. A bold, orange, ovoid shape oats above; the the addition of a deep, green, rectilinear shape at its center teases the eye in a spatial push-pull akin to the work of Hofmann. Other shapes in blues, light

green, and deep crimson further emphasize such spatial sensations in the work.

In two works entitled Hopscotch (1976 and 2001), Fratt’s title selection conveys the spatial “hopping” that the eye performs as it seeks to suss out similar color interactions. Both works feature a red ground. In the earlier serigraph, completed in collaboration with Armstrong, Fratt’s work explores a series of painterly oppositions. A gestural magenta spatter at center bears nothing in common with her expressionist predecessors.

e mechanical nature of the printing process has rendered what might at rst be read as gestural swipes into a calculated plane with precise boundaries. e composition also features a lighter, orange-red rectilinear shape at left; a cool, cerulean line jogging up from the bottom edge; and a small, green, curvilinear shape at top right. When read in

Catalogue from 1965 Washington Color Painters Exhibition

Catalogue from 1965 Washington Color Painters Exhibition

correlation with the red ground and magenta spatter, the eye “hops” and pulses. e cerulean line appears to hover close to the picture plane while the orange and pink recede. In the later acrylic on canvas composition, Fratt has replaced the magenta spatter with deep burgundy slashing marks that seem to hover above the cerulean and green shapes. Without the orange rectangle to establish a middle ground, the eye darts back and forth between cerulean and green, trying to understand their position in this complex space. Joann Bucklew, art critic for the Arizona Republic once referred to these impossible color relations as a kind of “chromatic dissonance.”

We see further evidence of Fratt’s experimentation with the spatial potential of color in Collage #3 (1980), composed hand-colored, cut-paper shapes. e work is at once a working out of colors and interactions designed for a larger canvas and a work in its own right. It serves as evidence of Fratt’s careful consideration of such e ects in her work. Colors are not chosen at random but rather serve as an integral component of process; placement and selection are vital to the work’s success.

a far-o mountain or mesa, while bold gestural marks hovering above may represent the encroaching storm clouds suggested by the title. e soaring space of sky mimics the techniques of earlier masters of the landscape genre but here the cool color palette seems derived from her desert surroundings.

Fratt utilized a similar vertical arrangement for Road to the Mountain (1977), one of the lithographs produced in collaboration with Armstrong. Using a minimal red and black, two-color scheme, along with the white of the paper support,Fratt arranges a simple rendering that is both fully abstract and yet still recognizable as a landscape. e road of the title—a negative slash of white support—leads the eye to recede through space to the evocation of a looming, black mountain, created through rough gestural strokes. e black marks e ectively divide the red composition into land and sky, and a darker red, curvilinear shape above seems to pulse with the blistering heat of a summer day.

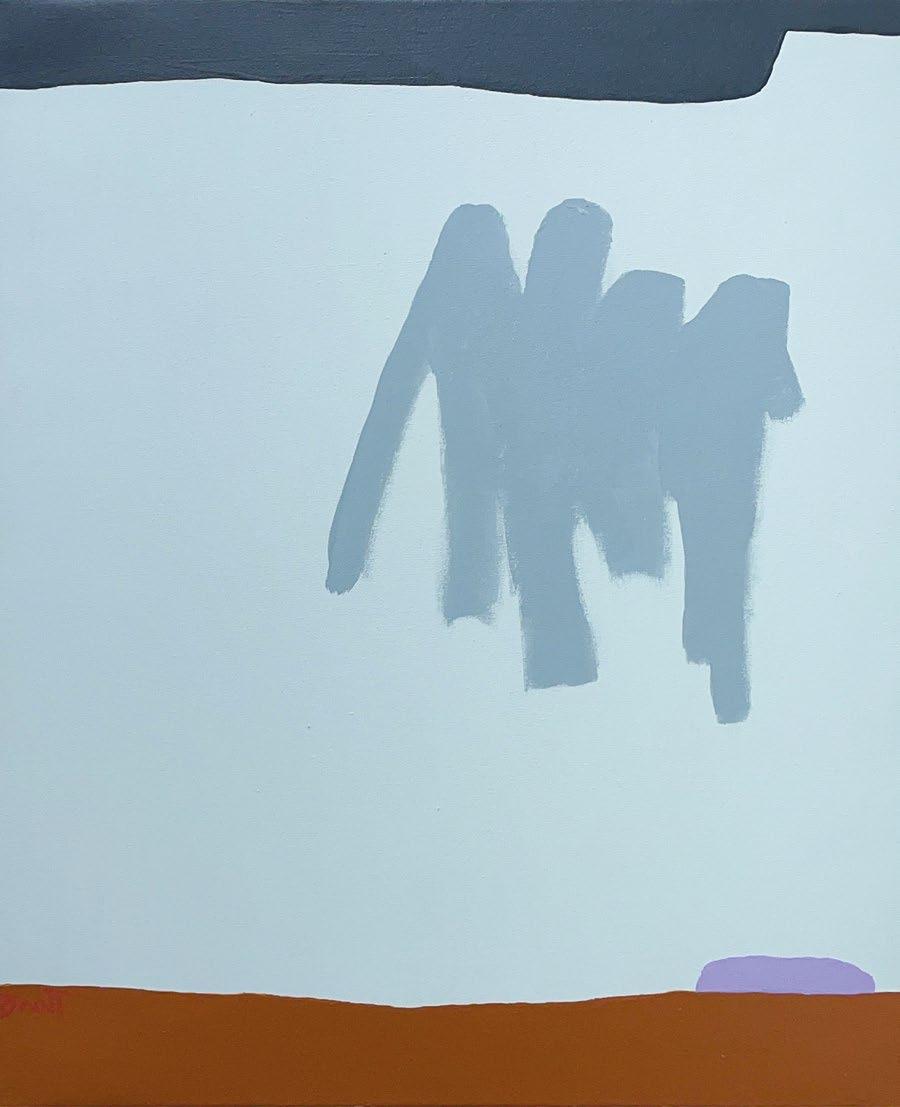

Other works from Fratt’s oeuvre maintain a connection to guration, often through the use of suggestive titles. Scholar Ursula Köhler argues Fratt’s titles were always purposeful, and that, unlike most of her contemporaries, “they open up concrete realms of association.”xiv For Monsoon (1985), Fratt selected a vertical format consistent with historical and traditional modes of representing the landscape. In the painting a bold, navy, slashing mark above and a at, orange, rectilinear shape below frame a sandy-hued area, which takes up roughly 2/3 of the picture plane. An icy pink splash of color suggests

In all the works gathered for Dorothy Fratt: Paint the Town Red, you have the opportunity to see the work of an inventive artist, pursuing her own course and path in largely abstract compositions. In the catalogue for a 1995 exhibition at the Riva Yares Gallery, Fratt spoke on her creative approach: “Sometimes the colors are right, but not the form. Or else the form is good but the colors won’t work. And, sometimes it ends up looking unlike anything I originally envisioned—a total surprise…Matisse said that starting a painting was like buying a railroad ticket to Marseille. Either you never get there or, if you do, you nd it’s not where you want to be. Each painting is a journey and an adventure. I don’t understand the process completely. Perhaps no one can.” Much like Fratt saw her own process as a journey lled with moments of surprise, the organizers of this exhibition invite you to embark on your own viewing adventure, to discover—again or for the rst time—Fratt’s work, and to reconsider her position in the history of D.C. abstraction.

Acrylic on canvas 40 x 43 in (101.6 x 109.2 cm)

Acrylic on canvas 37 x 39 in (94 x 99.1 cm)

Acrylic on canvas 31 x 26 in (78.7 x 66 cm)

Monsoon 1985

Acrylic on canvas 30 x 25 in (76.2 x 63.5 cm)

Installation view, Dorothy Fratt: Paint e Town Red. Photograph by Gregory Staley.

Installation view, Dorothy Fratt: Paint e Town Red. Photograph by Gregory Staley.

Acrylic on canvas 33 x 29 in (83.8 x 73.7 cm)

Code Talkers 1986

Acrylic on canvas 23 x 28 in (58.4 x 71.1 cm)

Acrylic on canvas

42 x 34 in (106.7 x 86.4 cm)

Untitled 1947

Oil on canvas 16 x 8 in (40.6 x 20.3 cm)

Installation view, Dorothy Fratt: Paint e Town Red. Photograph by Gregory Staley.

Installation view, Dorothy Fratt: Paint e Town Red. Photograph by Gregory Staley.

Acrylic on paper mounted on canvas 20 x 23 in (50.8 x 58.4 cm)

Acrylic on canvas 14 x 14 in (35.6 x 35.6 cm)

Paint e Town Red

Acrylic on canvas 14 x 14 in (35.6 x 35.6 cm)

Acrylic on paper

6 x 6 1/2 in (15.2 x 16.5 cm)

Acrylic on paper

6 x 6 1/2 in (15.2 x 16.5 cm)

Paint e Town Red

Acrylic on paper mounted on canvas 21 1/2 x 23 in (54.6 x 58.4 cm)

Acrylic on paper mounted on canvas 22 x 20 in (55.9 x 50.8 cm)

Acrylic on canvas 52 x 46 in (132.1 x 116.8 cm)

Phoenix Symphony Condector #1 1960

Sumi Ink on paper 11 x 8 1/4 in (27.9 x 21.1 cm)

Phoenix Symphony Condector #2 1960

Sumi Ink on paper 11 x 8 1/4 in (27.9 x 21.1 cm)

Installation view, Dorothy Fratt: Paint e Town Red. Photograph by Gregory Staley.

Installation view, Dorothy Fratt: Paint e Town Red. Photograph by Gregory Staley.

Untitled 1998

Acrylic on paper

12 x 11 in (30.5 x 27.9 cm)

Untitled 1994

Acrylic on paper

12 1/2 x 11 in (31.8 x 27.9 cm)

Untitled 2001

Acrylic on paper mounted on canvas 23 x 24 1/2 in (58.4 x 62.2 cm)

Paint e Town Red

Acrylic on canvas 21 x 25 in (53.3 x 63.5 cm)

Collage #3 1980

Collage on paper 16 x 14 in (40.6 x 35.6 cm)

Untitled (Still Life) 1941

Oil on canvas

17 1/2 x 24 1/2 in (44.5 x 62.2 cm)

i ii iii iv

Jean Lipman discusses the dominance of “cowboy art” in the West in her essay “What is Western Art?” for the catalogue for Fratt’s 1980 exhibition at the Scottsdale Center for the Arts.

According to Lippman, Fratt is “an advanced painter of the western landscape,” an artist who rises above regional labels and who is a “vital member of the national and international art world.” See Jean Lipman, “What is Western Art?” In Dorothy Fratt: paintings 1970-1980 Presented by Scottsdale Center for the Arts March 27- April 25, 1980, (Scottsdale, AZ: e Center for the Arts, 1980).

Fratt had her rst solo show in DC. in 1946 at the City Library. Following the aforementioned 1948 exhibition, her work was shown in two additional exhibitions, a 1964 invitational exhibition at the Corcoran Gallery and a 1967 group show at the Mickelson Gallery (707 G St. NW—the gallery shuttered in 1999).

See facsimiles of Knaths’ notes in Jean and Jim Young, Ornament and Glory: eme and eory in the Work of Karl Knaths (Annandale-on-Hudson, N.Y.: Edith C. Blum Art Institute, Milton and Sally Avery Center for the Arts, e Bard College Center, 1982).

Hans Hofmann, Search for the Real: And Other Essays eds. Sara T. Weeks and Bartlett H. Hayes (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1967).

v vi vii ix x xi

Wilhelm Ostwald, e Color Primer: A Basic Treatise on the Color System of Wilhelm Ostwald, trans. Faber Birren (New York: Van Nostrand Reinhold Co., 1969).

Barbara Perlman, “Fratt: Color Mirages,” Arizona Arts and Lifestyle (Spring 1980).

Gregory Fratt, phone conversation with the author, October 21, 2022. viii Perlman, 40.

e Washington color painters: Morris Louis, Kenneth Noland, Gene Davis, omas Downing, Howard Mehring [and] Paul Reed; an exhibition. (Washington D.C.: Washington Gallery of Modern Art, 1965). For more on the Washington Color School, see Jean Lawlor Cohen, Sidney Lawrence, Elizabeth Tebow and Benjamin Forgey, Washington Art Matters: Art Life in the Capital 1940-1990 (Charleston, S.C.: Washington, Arts Museum, 2013); and Karen Wilkin and Carl Belz, Color as Field: American Painting, 1950-1975 (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2007).

John Armstrong, “A True Original Color Field Artist” In Dorothy Fratt: paintings 1970-1980 presented by Scottsdale Center for the Arts March 27- April 25, 1980, (Scottsdale, AZ: e Center for the Arts, 1980). In 1977, Armstrong collaborated with Dorothy on a series of lithographs and serigraphs assisting the artist with the translation of painted compositions to the print medium. Many of these works are included in this exhibition.

xii xiii xiv xv

Rudolf Baranik, “Unexpected Intrusions” In Dorothy Fratt: paintings 1970-1980 presented by Scottsdale Center for the Arts March 27- April 25, 1980, (Scottsdale, AZ: e Center for the Arts, 1980).

Joann Bucklew, “Artist Rather an Style, Emphasized: Mixed Exhibit in Scottsdale,” e Arizona Republic (Phoenix, AZ), Sept. 19, 1965.

Born Education Solo Exhibition Selected Exhibition

1923 1938-44 1946 1948 1959 1964 1965 1974 1982 1984 1985 1986 1938 1953 1958 1961 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1972 1973 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1986 1987

Mt. Vernon College, Washington, D.C. (Full scholarship) Corcoran Gallery School of Art, Washington, D.C. (Full scholarship) Phillips Memorial Gallery Art School, Washington, D.C. (Full scholarship)

D.C. City Library, Washington, D.C. United Nations Club Gallery, Washington, D.C. Desert Art Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona

Tucson Center fot the Performing Arts, Tucson, Arizona Phoenix Art Museum, Phoenix, Arizona

Clare Yares Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona

Five Signi cant Years, (Statewide Touring)

Yares Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona Yares Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona omas Babcor Gallery, La Jolla, California Joseph Gross Gallery, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona

Corcoran Gallery, Washington, D.C. Corcoran Gallery, Washington, D.C. Festival Exhibition, Tucson Center for the Performing Arts, Tucson, Arizona Rosewell Museum of Art, Roswell, New Mexico Corcoran Gallery, Washington, D.C.

California Legion of Honor, San Francisco, California Yares Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona Yares Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona 4 women, Mickelson Gallery, Washington, D.C. Yares Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona Portrait Show, Yares Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona Permanet Museum Collection, Phoenix Art Museum, Phoenix, Arizona Yares Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona Woman/Art, Tucson Center for the Performing Arts, Tucson, Arizona Yares Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona

Cannel & Cha n Gallery, La Jolla, California Prints & Works on Paper, Yares Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona

Paul Reed & Dorothy Fratt, Yares Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona Fratt & Gilot, Cannel & Cha n Gallery, La Jolla, California Gottlieb's Contemporaries, Phoenix Art Museum, Phoenix, Arizona

Dorothy Fratt: 1970-1980, Scottsdale Center for the Arts, Scottsdale, Arizona (Catalogue)

4 Women, Carson-Sapiro Gallery, Denver, Colorado Lecturing Artist and Exhibitor, Yuma Symposium, Yuma, Arizona

Masters Choice: Dorothy Fratt Invites Claribel Cone Yares Gallery, Tempe Arts Center, Tempe, Arizona

Teaching Public Collections

1988 1989 1995 2008 2017 2018-19 2019 2020 2021 1946-51 1958-72

Tucson Center for the Performing Arts, Tucson, Arizona Yares Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona Wade Gallery, Los Angeles, California

Many Voices, Paintings from the Nineties, Yares Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona (Catalogue) Many Voices, Paintings from the Nineties, Yares Gallery, Santa Fe, New Mexico (Catalogue) Yares Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona Memorial Exhibition, Cattletrack Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona Colourful. Farbenfroh, Museum Art Plus, Donaueschingen, Germany

Color-Form-Line, Reyes Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona Shaping Vision Impressionism to Abstract Expressionism, Permanent Museum Collection, Palm Springs Art Museum, Palm Spring, California Ameen Art Gallery, ibodaux, Louisiana, (Catalogue) Unapologetic: All Women, All Year, Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Scottsdale, Arizona

Leap of Color, Yares Art, New York, New York Color/Form – Dorothy Fratt & Stefan Rohrer, Städtische Galerie in der Reithalle, Paderborn, Germany

Tense and Release: Art and Mood from the Permanent Collection, Tucson Center for the Performing Arts, Tucson, Arizona

Dorothy Fratt: A Desert Full of Color, Mayo Clinic Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona (Catalogue) Dorothy Fratt: Out of Washington, Yares Art, Santa Fe, New Mexico (Catalogue)

1946-51: Mt. Vernon College, Washington, D.C. 1958-72: Private instructor, Phoenix, Arizona

Phoenix Art Museum

Tucson Museum of Art IBM Corporation Vesti Corporation

Burlington Northern, Seattle, WA General Electric Corporation IT&T

Arizona State University Midland Federal Savings, Denver, Colorado Statewide Savings, Chicago, Illinois

Continental Grain Corp., New York, New York Exeter Drilling/ Inc., Denver, Colorado Chevron

Museum of Northern Arizona

New Mexico Museum of Art, Santa Fe, New Mexico Corcoran Gallery, Washington, D.C. Museum Art Plus, Donaueschingen, Germany

Scottsdale Museum of Contemporary Art, Scottsdale, Arizona Palm Springs Art Museum, CA Hilliard Museum, Lafayette, LA Stadtische Galerie in der Reithalle, Museen Paderborn, Germany

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

Dorothy Fratt: Paint e Town Red 19 November, 2022 - 12 January, 2023

Essay © 2022 Dr. Ashley Busby

Designed by Darvin Villavicencio Printed in Illinois, Chicago Photographs by Gregory Staley

Cover: I Owe You (detail), Dorothy Fratt, 1997 © Dorothy Fratt Estate

First, I want to thank Dr. Ashley Busby for the contribution of her insightful essay. I am forever grateful to Father Gregory Fratt for his generosity and good nature, allowing me to show his mother's work and legacy. I also heartily thank Darvin Villavicencio, Irina Leyva Pérez, and Michael Abrams for their unwavering support in the production of this exhibition.

Pazo Fine Art 4228 Howard Ave Kesington, Maryland 20895 info@pazo neart.com www.pazo neart.com

© 2023 Pazo Fine Art

All rights reserved. No part of the contents of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electrical, mechanical, or otherwise, without rst seeking the permission of the copyright owners and publishers. Every e ort has been made this seek permission to reproduce the images in this catalogue. Any omissions are entirely unintentional, and details should be addressed to the publishers.