THE TECHNOLOGICAL SUBLIME Works By Three Artists

Beverly Fishman Rockne Krebs Ruth Pastine Curated by Mike Zahn Catalogue essay by Dan Cameron17 - November 3, 2022

Considering The Technological Sublime

By Mike ZahnThe Technological Sublime is the title of an exhibition of works by Beverly Fishman, Rockne Krebs, and Ruth Pastine organized at Pazo Fine Art in the fall of 2022. The show brings these artists together, intending to draw upon subtle affinities present in the art, and suggests how it might be seen considering its place in the larger world.

Beverly Fishman is a post-formalist artist whose painted objects call attention to how perception is structured in myriad cultural ways. In a social sense, her work examines how malaise, anxiety, and affection arise within limits circumscribed by industry, biology, and communication. Fishman’s multipart constructions of synthetic color operate where dissociation and engagement intersect and suggest that individual agency is shaped by habitual management of emotional responses.

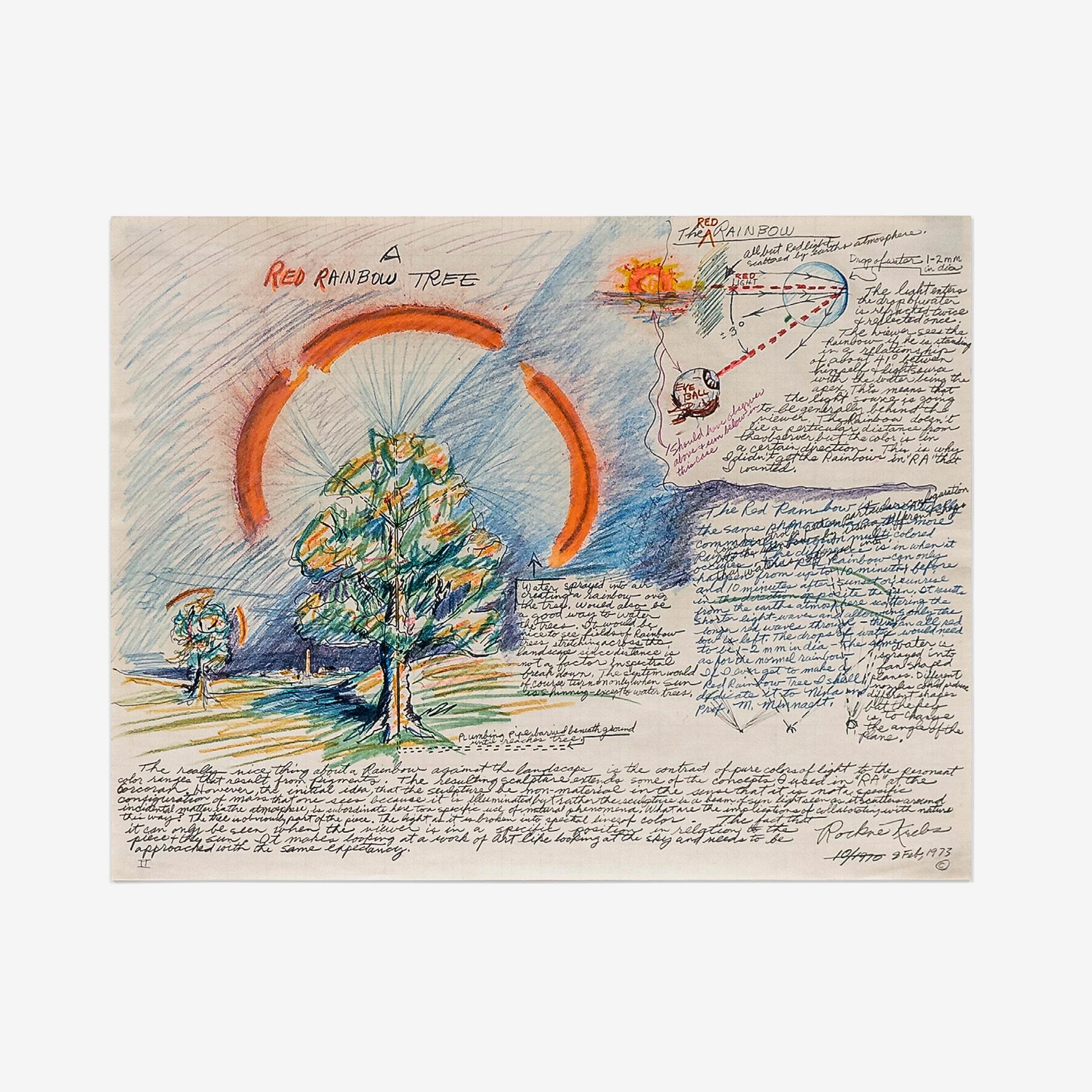

Rockne Krebs was a multi-disciplinary artist known for his monumental laser light installations. His transparent plexiglass sculptures likewise court symbolic passage through projection by imaginative means. In addition, notational works on paper provide glimpses into other levels of expression hinted at in larger pieces. The mystic vision that Krebs delineated was spectacular and private, exalted and hermetic, dazzling and still.

Ruth Pastine is a neo-minimalist painter whose stylistic interests are made clear through the phenomenological exposition of color. The illumination in these works appears consistent and bracketed by value shifts at the floating peripheries of chamfered panels. While not strictly materialist relative to generalizing devices such as charts or chips, Pastine’s work bears traces of deracinated hue, which hover between ambiguity and nuance. These attributes mitigate against typing Pastine’s paintings as specifically abstract in the usual manner.

These three artists each calibrate finely-tuned qualities of light and space through their unique approaches to the dynamics of media and spectatorship. This may place their work adjacent to what is held as the “ technological sublime ,” a contemporary premise derived from eighteenth-century philosophical musings on the awesome forces of nature. Transfers of power from the theological to the secular, or the divine to the human, uprooted authentic experience and subjected it to instrumental challenges from all sides.

This is, in short, the history of modernity. The American educator and critic Leo Marx (1919-2022) described the displacing effects of science and ideology in these same terms. Venturing hand in hand with progress, Marx proposed technology creates a “ hazardous concept, ” understood in part as a semantic void that language hastens to fill in the face of overwhelming change.

So what is the thing we routinely call technology? The meds we take each morning to help focus our attention? The entertainments we enlist to distract us each evening? The vibrations which perpetually leave us in dumbfounded states of wonder? The works of Beverly Fishman, Rockne Krebs, and Ruth Pastine imply technology, while novel and disruptive, is actually that which resists explanation because it does not yet have a name. Furthermore, in a neat inversion of dogma, what you see is not exactly what you see. The exhibition The Technological Sublime offers a liberating invitation to look anew at the conditions of our reality, where acts of making become words.

Mike Zahn, August 2022

Installation view: The Technological Sublime: Works by Three Artists. Photograph by Gian Carlos Perez

Installation view: The Technological Sublime: Works by Three Artists. Photograph by Gian Carlos Perez

THE GHOST IN THE MACHINE

By Dan CameronAs Yogi Berra famously quipped, the future isn’t what it used to be. For those of us who grew up on promises about men walking on the moon and videophones attached to our wrists, the sense that the future held limitless possibility was almost universal, with only the occasional caveat added about overpopulation or industrial pollution. It wasn’t so much unbridled hope or optimism that characterized our collective sense of excitement about the future but a glimpse of the sublime by way of technology. Computers might someday outstrip our ability to perform certain basic functions by ourselves, but that need not detract from the feeling of being spellbound by the rapid pace at which the technological revolution roared past its industrial predecessor, leaving many of our ideas about what constituted “progress” in the recycling bin of history.

Today, with an apparent majority of Americans under the age of fifty viewing the future with a sour combination of mistrust, fear, and trepidation, it’s hard to imagine most citizens’ near-complete absence of skepticism about technology in the late 1960s, when the Washington, DC-based artist Rockne Krebs introduced the world to the still unlimited

potential of a work of art that consists entirely of lights produced by lasers. To provide some historical context to Krebs’ achievements, it’s worth noting that conceptual artists beginning in the mid1960s had already established a precedent for art that was totally immaterial, and the Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s five-year Art and Technology program from 1967 to 1971 — in which Krebs was a participating artist — provided a useful template going forward for how museums and curators could collaborate with corporate partners on those increasingly common occasions when artists proposed using resources that well exceeded a museum’s capacity to provide them.

Even within these historical limits, Krebs’ achievement was extraordinarily prescient. He was the first to make art that relied on digital memory to project words and images into the night-time sky. His goal of temporal ephemerality helped lay the groundwork for a generation of time-based art beginning in the 1980s and counting today. Perhaps the most striking aspect of his work from a twenty-first-century perspective was his complete dismissal of market viability as a valuable metric for determining the value or worth of his work. Some of his commissioned pieces were conceived and fabricated to achieve some degree of permanence, but these were never assigned a particular priority over less

durable projects.Considering the stark reality that many of his most celebrated early works relied on technology that was made obsolete within a few years of their realization, the conspicuous absence of Krebs’ contribution from most historical narratives of technological innovation in late 20th-century American art may have mostly to do with the clunky, unglamorous responsibility of periodically upgrading materials and/or equipment — which nearly every artist to follow in Krebs’ footsteps has also found the need to contend with. For example, uploading

files to a Raspberry media player would be the equivalent of what in the early 1970s often meant locating, purchasing, and adjusting an expensive new laser to replace one that had recently burned out.

To begin the process of re-introducing Krebs’ art to a Washington DC public that hasn’t seen much of him since his death in 2011, gallerist Luis Pazo and curator Michael Zahn have focused on two distinct bodies of work. One is a group of freestanding plexiglass sculptures that Krebs produced concurrently with his laser-based installations, and which use transparent planes with partially painted surfaces to explore the visual potential of color suspended in space. The other is a selection from his hitherto unknown works on paper, which someday could easily serve as the basis for a more extensive exhibition that examines how he used the oldest art medium to describe his aspirations for the newest.

While a compelling argument can and should be made about the times catching up to Krebs’ radically innovative practices of a half-century ago, a more sustained discussion about his career would be better off offering an alternative historical approach to betterknown artists of the period. Such an approach would be given a significant boost by linking his achievements to those of certain artists practicing today. For that reason, the present exhibition looks at work being made in the present by two mid-career painters, Beverly Fishman, and Ruth Pastine, neither of whose paintings reveal any obvious stylistic affinities with Krebs’ sculptures, although each shares a subtle but essential point of comparison.

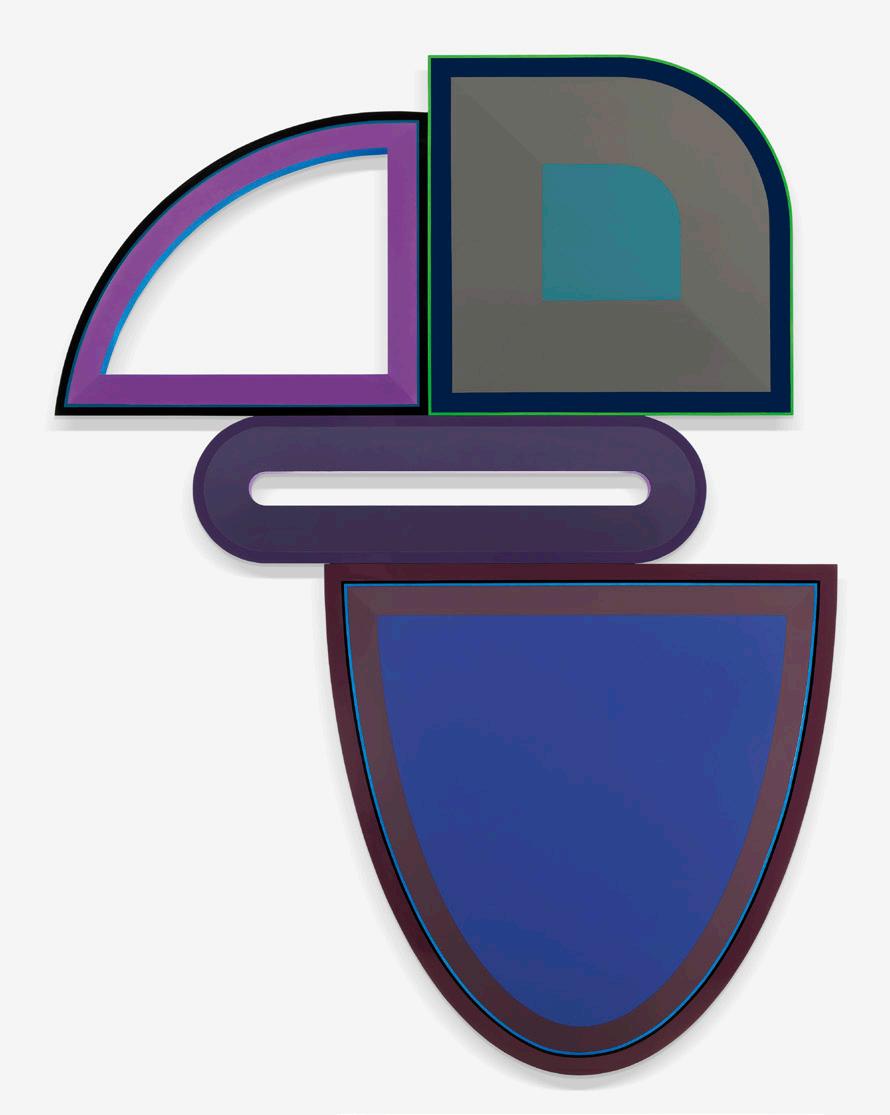

Fishman, who lives in Detroit and was the Head of Painting for Cranbrook Academy of Art for many years, has long produced complex multi-part works that straddle the conventional distinctions between painting, sculpture, and installation. Using a hard-edge formal vocabulary that hearkens back to such American geometric painters of the 1960s as Gene Davis, Kenneth Noland, and Frank Stella, Fishman has updated her sources by working on uniquely contoured and customized shaped wooden reliefs, which lend the finished works a modular, dimensional order that encourages the viewer to identify them as sequences or clusters of legible forms. Both the alluring contours of the individual units and Fishman’s high-key color choices are intended to trigger associations on the viewer’s part that run closer to ads from pharmaceutical companies than what most would consider the canon of modernist painting.

In fact, as the titles for the three works included in The Technological Sublime — Migraine, Anxiety, ADHD (2019); Pain, Opioid Addiction, Bipolar Disorder, Muscle Spasms (2019); and Digestive Problems, Anxiety, Anxiety, Anxiety (2020) — make clear, these associations are deliberate on the artist’s part, and to an extent should be understood as a critical de-coding of the tools of visual seduction employed by the designers of mass-produced prescription medications. Far from being onerous or weighty, taking one’s anti-depression or anti-anxiety medication today has been masterfully retooled as the grownup equivalent of the sensorial pleasure that came with chowing a Flintstones vitamin when we were kids. Such subterfuge is subtly flagged by Fishman’s artistic choice not to identify the drugs themselves but only name the symptoms each is prescribed to dispel: Anxiety, Anxiety, Anxiety.

This choice of iconography is a personal one for the artist, whose life experience includes witnessing closeup the ravages of AIDS in the 1980s and 1990s, as well as the more intimate understanding of caring for terminally ill family members, whose medical condition and treatment Fishman watched become converted into a litany of mass-produced drugs. The sleek packaging, eye-grabbing colors, and pills’ aerodynamic shapes also represent their manufacturers’ concerted effort to conjure

our dormant fascination with futuristic technologies and the remnants of hope and optimism once inextricably attached to them. If, as one might guess, the makers of high-end pharmaceuticals have indeed structured much of their design protocol using the critical discourse of abstract painting as their template. Then it’s only fair that those identical prototypes be redirected back into painting, including the receipts. Once appraised of her sources, an informed viewer of Fishman’s work perceives two separate tracks along which their responses and interactions might run. A somewhat detached attempt at objectivity would be more likely to result in heightened awareness and sensitivity

toward the nuances of Big Pharma’s color theory, while the less critical perspective would approach her paintings as coded representations of contemporary society at its essence, with the refined pleasures of ‘pure’ abstraction still aspiring to make themselves felt by way of Fishman’s quasi-industrialized, frequently luminous surfaces.

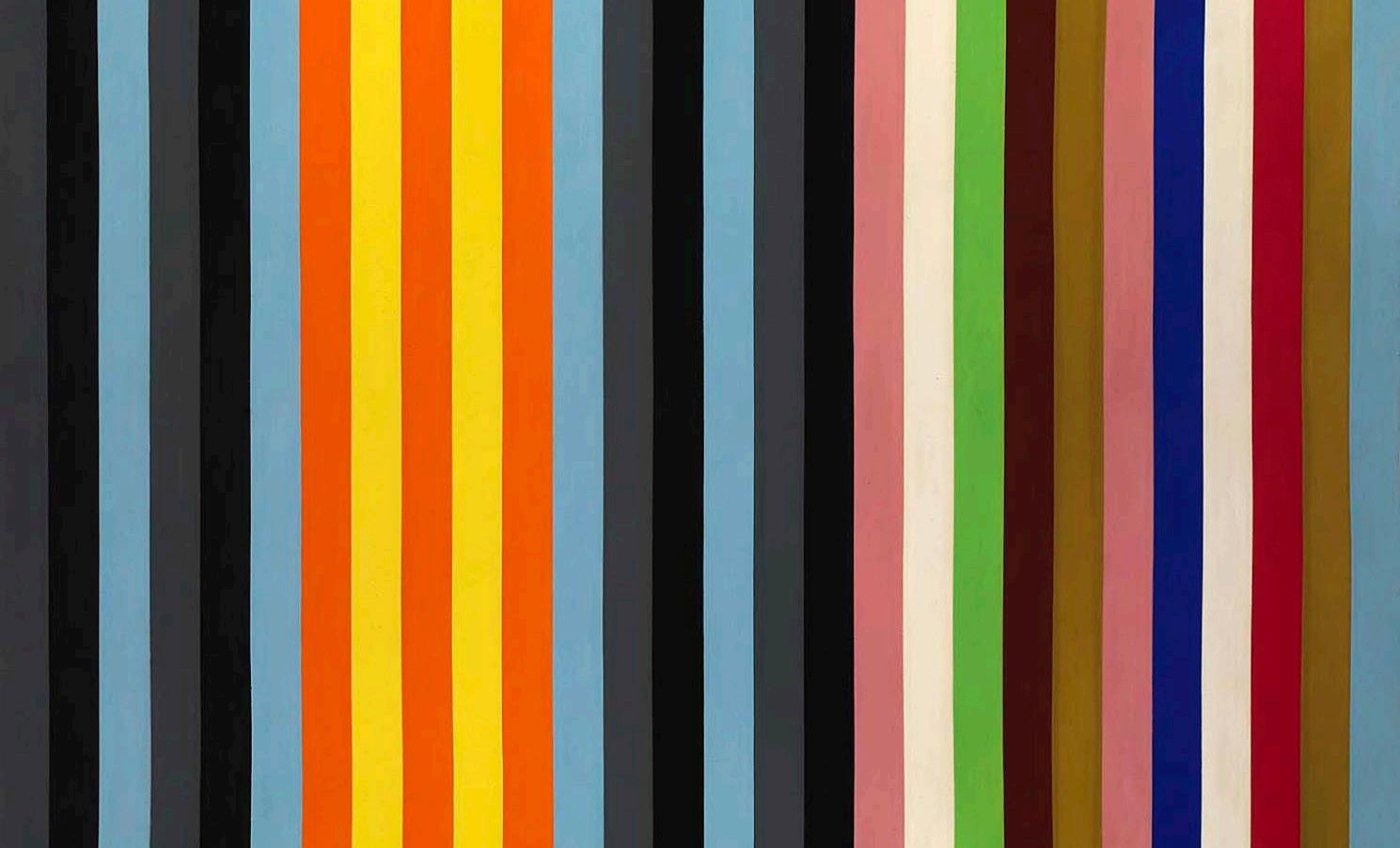

At the opposite end of the stylistic spectrum, the semi-monochromatic paintings of Ruth Pastine have long been compared to such pioneers of the Southern California Light and Space movement of the 1960s and 1970s as Robert Irwin or James Turrell, from whom she and countless other artists have borrowed a broad range of features such as format and scale. Yet, despite such clear points of affinity, Pastine’s work is probably best appreciated taking as background a previous generation: the New York-based Abstract Expressionist painters of the late 1940s and 1950s. While the aspirations of her older West Coast contemporaries may have been rooted in a generational effort to convey the essence of light in the most liberated manner possible, using materials that reflect the urgent drive to innovate, Pastine has consistently demonstrated more interest in painstakingly exploring the particular chromatic and tonal nuances of oil paint on canvas. Accordingly, her

reductive approach to articulating form is far closer in spirit to Barnett Newman and Ad Reinhardt than to their comrades in the late 1940s/early 1950s mode that Harold Rosenberg famously termed “action painting.”

Instead of action, there is a slow, gradual movement within Pastine’s paintings, which the viewer might be inclined to experience as a luxuriant sweeping back and forth of their eyesight across their gently mottled surfaces. The term “almost monochromatic” was used before to describe a painting in which various shades of the same color are used to

develop subtle gradations across an expanse of surface area. For example, in the horizontal painting Blue 1, Sublime Terror Series (2019), the blue-black edges on the left and right sides slowly fade into midnight blue, then glowing cerulean, ending in a wide Robin’s-egg swath filling the middle third of the picture plane. Because the edges of Pastine’s canvases are beveled, they never appear to lay flat on the wall so much as gently bow outwards, visually amplifying the painting’s glowing core.

A companion, vertically shaped painting, Blue Violet 1, Sublime Terror Series (2019), in which the color gradations follow a slightly more segmented order, features a

pair of light blue bands that seem to be making a sly, quiet homage to Barnett Newman’s signature “zips.” As in Newman’s or Reinhardt’s case, Pastine’s paintings can be quickly captured by an initial glance, but their inherent visual drama only emerges once a closer study reveals the subtle intricacies of the meticulously detailed surface.

The many-layered readings that can be brought to both Fishman’s and Pastine’s paintings are characteristic of today’s artists’ efforts to make use of every possible reference and connection to deepen the work’s resonance. As abstract painters, their claim to a personal, philosophical, or critical understanding of their work rests partly on a partial refutation of the premise that “abstraction” means anything like what it meant to earlier generations. For most of the 20th century, the word functioned handily as a catch-all antonym for representation. Eventually, it came to imply that most, if not all, of a painting’s content was inherently self-referential, concerned with testing the boundaries of abstraction but not with any reference to the sociopolitical context in which it was made or shown. Granted that none of the first generation of abstraction’s pioneers — a list that for present purposes includes Kazimir Malevich, Hilma af Klint, Piet Mondrian, and Vasily Kandinsky — felt that their work was non-representational, the crusade to establish abstractions as an entirely

legitimate visual language required a long, tempestuous struggle that dominated avantgarde discourse from the mid-1920s until the mid-1970s, when abstraction’s purported autonomy from the concerns of the outside world was openly challenged first by the Minimal and then the Earthworks generation.

In many ways, it is this historical link to abstraction’s struggle to establish its legitimacy that brings the work of Fishman and Pastine into a conversation with Rockne Krebs, who came to Washington DC in 1964 and soon fell under the influence of the painter Gene Davis (1920-1985), whose own career included numerous projects bringing color abstraction out of the white cube and into public spaces. Krebs didn’t reject the premises of abstraction at all. In fact, his temporary environmental disruptions can be easily defended as forms of conjecture about the ultimate place of abstraction in modern life. The main difference, Krebs might argue, between an abstract painting that’s maintained in climate-controlled conditions within the safety of an art museum and a laser beam that arcs through the sky or across a bridge is that the temporal nature of the latter makes it infinitely open to replication in the future, much the way that contemporary light-based artists do today.

What The Technological Sublime seems to propose in bringing together these disparate artists’ work extends well beyond a conventional validation of Krebs’ ideas within a plausibly updated context. Conjuring a society where the trappings of futuristic technology are all but inescapable, both Pastine and Fishman are plugged into our present-day digital maelstrom in a way that Krebs could have only imagined, which is why their very different styles share a marked degree

of ambivalence, in the form of either a critical entanglement with or a visual refuge from, this tech-centric worldview. By comparison, Krebs’ transparent and painted Plexiglass sculptures straightforwardly fuse color, light, and surface, using interconnected planes that the viewer experiences as simultaneously solid and transparent. Although materials that seemed space-age a half-century ago are so commonplace today that their aura of novelty has vanished, but the drive to employ technology to explore the limits of visual perception is still fully intact.

For those already familiar with Krebs’ critical role within the conjoined histories of Earthworks and light-based technology, the more likely revelation of the present exhibition is the series of works on paper from the early 1970s; all centered on the theme of artificial rainbows. Covering the entire work surface as project drawings tend to do, each page is crowded with multiple images of trees, clouds, and rainbows, along with dense fields of text detailing how to go about making such technology-aided marvels as a White Rainbow Tree (1973), a Red Rainbow Tree (1973), or a Bent Rainbow (1975). Irrespective of their intended utility for a future project that was never realized, today, Krebs’ works on paper communicate projects that never needed to be materialized in real space and time to mesmerize the viewer.

Spending much of your day lost in the virtual realm — an activity as commonplace today as it would have been unthinkable in 1973 — does have the secondary advantage of training our minds to adapt quickly to new visual information. For that reason, the likelihood of one of Krebs’ proposals ever getting built has been rendered meaningless compared to his capacity to envision such things in the first place, to say nothing of knowing and explaining how to make them. Because Rockne Krebs never saw a pressing need to qualify the role of technology in the process of artistic innovation, his ideas communicate with the absolute clarity and conviction of someone who envisioned our future as a place where the only limits to the sublime come from the failure of our imaginations to visualize it as reality.

Dan Cameron, August 2022THE WORKS

Beverly Fishman

Untitled (Migraine, Anxiety, ADHD), 2020

Urethane paint on wood 77 x 84 x 2 in (195.6 x 213.4 x 5.1 cm)

Installation view: The Technological Sublime: Works by Three Artists. Photograph by Gian Carlos Perez

Installation view: The Technological Sublime: Works by Three Artists. Photograph by Gian Carlos Perez

Beverly Fishman

Untitled (Pain, Opioid Addiction, Bipolar Disorder, Muscle Spasms), 2019

Urethane paint on wood 90 x 69 1/4 x 2 in (228.6 x 175.9 x 5.1 cm)

Rockne Krebs

Untitled (Red Line), 1970 Plexiglass and acrylic paint 73 1/2 x 29 x 24 in (186.7 x 73.7 x 61 cm)

Rockne Krebs

Untitled, 1967 Plexiglass 54 1/2 x 46 x 42 in (138.4 x 116.8 x 106.7 cm)

Rockne Krebs

Untitled, 1985

Signed and dated Plexiglass and acrylic paint 97 x 32 1/2 x 24 in (246.4 x 82.5 x 61 cm)

Installation view: The Technological Sublime: Works by Three Artists. Photograph by Gian Carlos Perez

Installation view: The Technological Sublime: Works by Three Artists. Photograph by Gian Carlos Perez

Rockne Krebs

Untitled, 1986

Plexiglass with acrylic paint 97 1/2 x 25 1/2 x 25 in (247.7 x 64.8 x 63.5 cm)

Rockne Krebs

Hot Flower, 1971

Plexiglass

91 1/2 x 35 1/2 x 24 1/2 in (232.4 x 90.2 x 62.2 cm)

Rockne Krebs

Untitled, 1968

Plexiglass 99 1/2 x 72 x 50 1/2 in (252.7 x 182.9 x 128.3 cm)

Installation view: The Technological Sublime: Works by Three Artists. Photograph by Gian Carlos Perez

Installation view: The Technological Sublime: Works by Three Artists. Photograph by Gian Carlos Perez

Rockne Krebs

A Rainbow Tree, 1970 Lithograph, colored pencil on paper 17 x 22 in (43.2 x 55.9 cm)

Rockne Krebs

A Red Rainbow Tree, 1973 Lithograph, hand colored pencil on paper 17 x 22 in (43.2 x 55.9 cm)

Rockne Krebs

A White Rainbow Tree, 1973 Lithograph, colored pencil, nextel paint on paper 17 x 22 in (43.2 x 55.9 cm)

Rockne Krebs

The Bent Rainbow, 1973

pencil, ink, charcoal on front and verso on paper

x 22 in

cm)

Ruth Pastine

Blue Light 1, Sequence Series, 2018 Oil on canvas on beveled stretcher 60 x 60 x 2 1/2 in (152.4 x 152.4 x 6.3 cm)

Violet

Ruth Pastine

Terror Series,

Ruth Pastine

Blue, Rise Series, 2021

Oil on canvas on beveled panel

24 x 24 x 2 1/2 in (61 x 61 x 6.3 cm)

Installation view: The Technological Sublime: Works by Three Artists. Photograph by Gian Carlos Perez

Installation view: The Technological Sublime: Works by Three Artists. Photograph by Gian Carlos Perez

Ruth Pastine

Green, Rise Series, 2021 Oil on canvas on beveled panel 24 x 24 x 2 1/2 in (61 x 61 x 6.3 cm)

Ruth Pastine

Yellow, Rise Series, 2021

Oil on canvas on beveled panel 24 x 24 x 2 1/2 in (61 x 61 x 6.3 cm)

Ruth Pastine

Fetish (Red), Primary Red Series, 2011 Oil on canvas on beveled stretcher 32 x 32 x 2 1/2 in 81.3 x 81.3 x 6.3 cm

THE Artists

Beverly Fishman (b. 1955, Philadelphia, PA) received her Master of Fine Arts in 1980 from Yale University and her Bachelor of Fine Arts from the Philadelphia College of Art in 1977.

Fishman’s work has been the subject of recent solo exhibitions at The Contemporary Dayton, Dayton, OH; Kavi Gupta Gallery, Chicago, IL; Eli and Edythe Broad Art Museum, East Lansing, MI; Walter Storms Galerie, Munich, Germany; SOCO Gallery, Charlotte, NC; Gavlak Gallery, Los Angeles, CA; Miles McEnery Gallery, New York, NY; Louis Buhl & Co., Detroit, MI; Library Street Collective, Detroit, MI; Ronchini Gallery, London, United Kingdom; Kravets Wehby Gallery, New York, NY; and CUE Art Foundation, New York, NY.

She has been included in group exhibitions at numerous international institutions including the American Academy of Arts and Letters, New York, NY; Borusan Contemporary, Istanbul, Turkey; Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus, OH; Cranbrook Art Museum, Bloomfield Hills, MI; Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, MI; The Drawing Center, New York, NY; Frederik Meijer Gardens & Sculpture Park, Grand Rapids, MI; National Academy of Design, New York, NY; Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Overland Park, KS; Museum of Contemporary Art, Chicago, IL; Weatherspoon Art Museum, Greensboro, NC; and White Columns, New York, NY, among others.

Her work may be found in the collections of Borusan Contemporary, Istanbul, Turkey; Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, VA; Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus, OH; Cranbrook Art Museum, Bloomfield Hills, MI; Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit, MI; Eli and Edythe Broad Museum, East Lansing, MI; MacArthur Foundation Collection, Chicago, IL; Moody Center for the Arts, Rice University, Houston, TX; Nerman Museum of Contemporary Art, Overland Park, KS; University of Michigan Museum of Art, Ann Arbor, MI; Weatherspoon Art Museum, Greensboro, NC, and elsewhere.

Fishman was inducted as a National Academician of the National Academy of Design in 2020. She is the recipient of the Anonymous Was A Woman Award; the American Academy of Arts and Letters’ Hassam, Speicher, Betts, & Symons Purchase Award; a Guggenheim Fellowship in the Fine Arts; and a Fellowship Grant from the National Endowment for the Arts.

The artist lives and works in Detroit, MI.

Rockne Krebs (b. 1938, Kansas City, MO - d. 2011, Washington, DC) received his Bachelor of Fine Arts in sculpture from the University of Kansas, Lawrence, in 1961. Beginning in 1970, Krebs created numerous public art commissions and coined the phrase “urban-scale laser installations” to describe his monumental sculptural laser light installations.

During his career, he presented numerous exhibitions, among those, solo shows at the Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY; Baxter Art Gallery of the California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA; Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; and the National Academy of Science, Washington, DC. The group shows include the Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art, Ridgefield, CT; The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL; Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD; Cincinnati Art Museum, Cincinnati, OH; Cleveland Center for Contemporary Art, Cleveland, OH; Cranbrook Art Museum, Bloomfield Hills, MI; Georgia Museum of Art, Athens, GA; Jefferson Place Gallery, Washington, DC; The Jewish Museum, New York, NY; Kansas City Art Institute, Kansas City, MO; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA; Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, Madison, WI; National Collection of Fine Arts, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC; Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA; The Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, NJ; San Francisco Museum of Art, CA; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN; Washington Gallery of Modern Art, Washington, DC; Whitney Museum, New York, NY, among others.

His pieces are part of the collections of Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY; Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art, Ridgefield, CT; Baltimore Museum of Art, Baltimore, MD; Brooklyn Museum, Brooklyn, NY; Butler Institute of American Art, Youngstown, OH; Fort Worth Art Museum, Fort Worth, TX; Georgia Museum of Art, Athens, GA; High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA; Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles, CA; Massachusetts Institute of Technology, The Center for Advanced Visual Studies Special Collection, Cambridge, MA; The Menil Collection, Houston, TX; Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, Fort Worth, TX; National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC; Philadelphia Museum of Art, Philadelphia, PA; Phillips Collection, Washington, DC; Princeton University Art Museum, Princeton, NJ; Smithsonian American Art Museum, Washington, DC; Smithsonian Archives of American Art, Washington, DC; Spencer Museum of Art, Lawrence, KS; Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN.

In 1970 he received a National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship, and in 1972 a Guggenheim Foundation Fellowship. In addition Krebs was granted a research fellowship by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology Center for Advanced Visual Studies by its founder György Kepes.

Ruth Pastine (b. 1964, New York, NY) received a four-year scholarship to Cooper Union for her B.F.A. Upon graduating she was awarded a post-graduate independent residency grant to the Gerrit Rietveld Academie, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. She received her M.F.A. from Hunter College of the City University of New York where she focused on painting, color theory and critical studies.

In 2009, Pastine began site-specific work with a public commission entitled Limitless, composed of 8 large-scale vertical paintings installed as two series in the adjoining lobbies of Ernst & Young Plaza in downtown Los Angeles. In 2014, Ruth Pastine had her first museum survey exhibition titled: Attraction: 1993-2013 at MOAH Lancaster Museum of Art and History, Lancaster, CA, with exhibition catalog essays by Donald Kuspit and Peter Frank with an appreciation by De Wain Valentine. In 2015, she opened Present Tense, Paintings, and Works on Paper, spanning 2010-2015, at the C.A.M. Carnegie Art Museum, Oxnard, CA.

Working in series is an essential aspect of her creative process, as she evolves paintings in concert with and juxtaposition to one another, furthering the perceptual interaction of color. Her work addresses heightened perception through the interaction of color contexts, lending itself to phenomenology and enhancing greater awareness of existential inquiry. She continues to evolve pure abstraction and follow the concepts of Minimalist theory, furthering the phenomenological experience of light and space in her work. She explores the subtle character and nuance of color, color, and light are reduced to their most elemental form. She works with oil paint on canvas, building layer upon layer, and countless small brush strokes resolve and appear visually seamless, producing an objective and dematerialized image.

Her works are included in numerous public and corporate collections, including the Achenbach Foundation for Graphic Arts, Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco, CA; SFMOMA San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, CA; MCASD Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, CA; Frederick R. Weisman Art Foundation, Los Angeles, CA; MFAH Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, TX; MOAH Lancaster Museum of Art and History, Lancaster, CA; Brookfield Properties, Ernst & Young Plaza, Los Angeles, CA; A.X.A. Art, Cologne, Germany; Qualcomm, San Diego, CA; C.I.M. Group Headquarters, Los Angeles, CA, PIMCO Global Headquarters, Newport Beach, CA; Proskauer, Washington, D.C.; United Airlines, Los Angeles, CA among others.

The artist lives and works in Southern California.

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

The Technological Sublime: Works by Three Artists

September 17–November 3, 2022

Essay ©️ 2022 by Dan Cameron

Designed by Victor de la Cruz

Printed in Illinois, Chicago

Photographs by Gian Carlos Perez and Gregory Staley

Cover: Blue 1, Sublime Terror Series (detail) Ruth Pastine, 2019 ©️Ruth Pastine

We would like to thank Dan Cameron for the contribution of his insightful essay. We are especially grateful to Beverly Fishman, Heather Krebs, Rockne Krebs Art Trust, Ruth Pastine, Michael Zahn, Miles McEnery Gallery, Irina Leyva Pérez and Michael Abrams for their unwavering support in the production of this exhibition.

Pazo Fine Art

4228 Howard Ave Kensington, Maryland 20895

Phone 571-315-5279

info@pazofineart.com www.pazofineart.com

©️ PAZO FINE ART

All rights reserved. No part of the contents of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electrical, mechanical, or otherwise, without first seeking the permission of the copyright owners and publishers. Every effort has been made to seek permission to reproduce the images in this catalogue. Any omissions are entirely unintentional, and details should be addressed to the publishers.