FOR EVER A SAI NT

DREW BREES, NEW ORLE ANS’ GRE ATEST CHAMPION

BY ROD WALKER STAFF WRITER

Dear Drew,

I’m writing this on behalf of a city, a region, a fan base.

It’s a thank-you letter that every member of the Who Dat Nation would surely sign to show their appreciation for your 15 years of blood, sweat, tears, fractured ribs and everything else. You did it all while bringing hope to a city during a time when there wasn’t much left.

When you decided to come to New Orleans in 2006, you believed you could help restore a city that had been devastated by Mother Nature the year before. And you believed you could bring hope to a starving franchise hungry to taste the ultimate success.

“This is where I belong, and I felt like this was a calling,” you said 11 years ago during the Saints’ Super Bowl-winning season.

You believed in Sean Payton’s vision. But more importantly, you believed in yourself.

You weren’t concerned about where the Saints had been, but only where they could go.

You were willing to put all those lofty expectations on your surgically repaired right shoulder and try to take the New Orleans Saints to heights they had never seen.

Then, on a magical Sunday in February 2010,

you delivered, leading the Saints to that Super Bowl title the Who Dat Nation had for so long coveted. You did the impossible that day, so convincingly that doing it again seemed inevitable. It was your motivation. You thought you could. And as long as you were on the field and there was time left on the clock, everyone else thought the Saints could, too.

The clock finally ran out Jan. 17 in the Superdome with a 30-20 loss to the Tampa Bay Buccaneers. That three-interception performance wasn’t the fairy-tale ending you or any of us would have written. In football, even the greats like you don’t always get to write your own perfect ending. But then again, this is perfect for you. You got a chance to walk away from the game when you saw fit, hanging up the No. 9 jersey that no Saint should ever dare wear again. You knew it was time. We knew it was time. You made it official March 14, 2021, exactly 15 years to the March 14, 2006, date you became a Saint.

“Each day, I poured my heart and soul into being your quarterback,” Brees wrote in his farewell post on Instagram. “Till the very end, I exhausted myself to give everything I had to the Saints organization, my team and the great city of New Orleans.”

It would take 80,358 words (one for each yard you threw for) or 571 paragraphs (one for each touchdown) to do justice to the first-ballot Hall of Fame career that came to an end before you got the farewell tour you deserved. You deserved to hear 70,000-plus folks yell “Dreeeeew” one last time while you were in a Saints uniform. Surely the team will give you that opportunity at some point next season. It’ll be strange not seeing you out there leading the pregame chant or licking your fingers as you lead a two-minute drive.

Someone will have some giant shoes to fill. Walking away from the game you gave so much to probably wasn’t easy.

We know how competitive you are. You showed us in 2019 when you returned from that thumb injury earlier than any of us (except you) expected. You showed us again in 2020, coming back after fracturing all those ribs and having a collapsed lung, along with some other injuries you probably never mentioned.

“It’s not a matter of if I can still play. I know I can still play,” you said last January when you decided to run it back one last time.

But in the end, family won out.

Now you’ll get a chance to spend more time with wife Brittany and kids Baylen, Bowen,

OPPOSITE: Mike Delahoussaye, owner of the Tic Toc Cafe in Metairie, La., updates his message board on Sept. 16, 2019, after Drew Brees’ thumb was injured in a play against the Los Angeles Rams. DAVID GRUNFELD / THE TIMES-PICAYUNE | THE NEW ORLEANS ADVOCATE

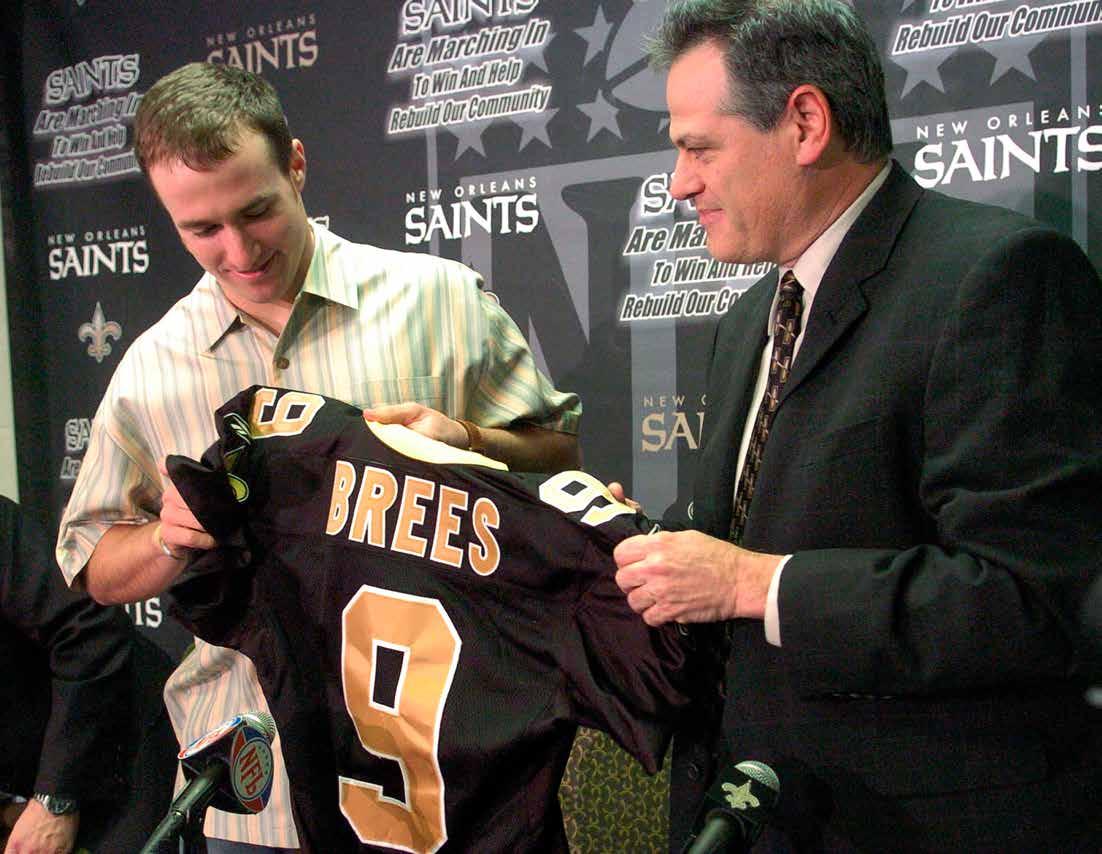

OPPOSITE: In his first press conference as a Saint, on March 15, 2006, Drew Brees gets his No. 9 jersey from general manager Mickey Loomis.

ROSE / THE TIMES-PICAYUNE | THE ADVOCATE

Callen and Rylen. Fittingly, your last passes in the Dome were thrown to your three sons as you hung around and soaked it all in one last time after your final game.

You told us last January that whenever you called it quits, those five people would be the reason.

“When that time comes, I’ll know,” you said. “And, in large part, it’ll be because of my family. I’ve played 30 years of organized football, 19 years of professional football. Those 30 years, that’s three-quarters of my life. I’ve devoted myself to this for so long and had my family sacrifice for so long. These are all the things you take into account when making a decision like that.”

You’re closing the book on one of the greatest

careers in NFL history. Yes, there are some pages in it, particularly ones written last summer during a divisive time for our country, that you would probably write a different way if you could do it over again. But those pages shouldn’t take away from the collective whole of such an amazing body of work, not just on the field but also off of it.

No one in NFL history has completed more passes or thrown for more yards than you. Only Tom Brady has thrown more touchdowns.

And while all those astronomical numbers since entering the NFL in 2001 are what folks around the NFL will remember, your legacy around these parts will be far greater.

You didn’t just live in New Orleans and play in New Orleans.

In a way, you were New Orleans.

The face of the franchise.

The face of the city.

When people across the country think of New Orleans, your name is now among the first to come to mind. You weren’t born here, didn’t grow up here, but you made it your home.

You helped a city and a franchise rebuild. A mark of success is leaving something better than it was when you got there. You did that, raising the bar to where Super Bowls are now the expectations.

Your name will soon hang in the rafters of the Superdome in its Ring of Honor, right alongside those of Archie, Willie, Morten, Rickey, Will and Mr. Benson. A gold jacket in Canton, Ohio, awaits you, too.

You’ll surely get a statue outside of the Dome as well, just like Mr. B and Steve Gleason.

If they do your statue to size, it’ll be right at 6 feet tall, the height many thought wasn’t quite tall enough to be successful it in college or the NFL.

But if they do it to the size of what you meant to this city, it’ll be as tall as the Benson Tower just across the way.

Almost larger than life.

And for the city of New Orleans, you were that.

And because of that, the city of New Orleans says thank you.

“Each day, I poured my heart and soul into being your quarterback. Till the very end, I exhausted myself to give everything I had to the Saints organization, my team and the great city of New Orleans.”

DREW BREES, IN HIS FAREWELL POST ON INSTAGRAM

With his right shoulder iced, quarterback Drew Brees speaks with reporters during 2006 training camp at Millsaps College in Jackson, Miss.

OPPOSITE: Saints fans filled up the Superdome on Sept. 25, 2006, for the first home game after Hurricane Katrina against the Atlanta Falcons.

Drew Brees took in the Superdome one last time as a Saints player in January. What he saw is anyone’s guess, but it was loaded with feeling, for him and for the city

BY LUKE JOHNSON STAFF WRITER

The man paused just for a moment to look back.

Just one sneak peek over his shoulder on his way out. It was fleeting, but to everyone who saw it, felt pregnant with meaning. He later said he planned to take his customary time, to give the end of another season an opportunity to breathe before he made a decision about his future.

But just watch that fraction of a second when he gazes over the No. 9 on his shoulder pads from the tunnel that leads away from the Superdome turf.

Watch that, and try suggesting he didn’t know he was taking in this image one final time.

Saints quarterback Drew Brees announced March 14 that he was retiring after 20 NFL seasons. Much of his final 15 of those were spent right there on that field, delighting the thousands who made a pilgrimage to watch him perform his exquisite art. They were forcibly and noticeably absent for that last game, giving that last look an especially sad and quiet quality, another precious privilege the pandemic stripped away.

Brees’ football legacy is almost unrivaled. At his peak, he reached previously unknown heights, and because his peak spanned what would amount to an entire career for many accomplished football

players, Brees’ career towers even above the greats.

At the nexus of skill, intelligence and focus, there is Brees, beating the world’s premier athletes and defensive minds not only because he had the arm, but because he was so thoroughly prepared he knew where they all were going better than they knew it themselves. The last drop of ink in one of the most impressive football stories ever written — that was the look over the shoulder.

He looked back. His eyes were wide, like they were trying to take in everything. His brow raised, wrinkling his forehead. His lips pursed.

What was going through his mind in his final act as a uniformed professional football player?

What can this brain, which has cracked the complex code of countless NFL defenses, process in a fraction of a second?

Could he see the greatness play out once more? Could he see the pinpoint throws and the fourth-quarter brilliance and the records that fell by the wayside right there in that building?

Could he leave behind the exhausting mental and physical toll he paid to reach this most exalted plane of the game? Could he peel that back and see only the joy he shared with family, teammates, coaches, lifelong friends, an entire city?

Could he see it all, including the moments he failed?

In a still frame, the moment is captured forever, giving Brees and all he shared his talents with infinite time to reminisce, unpressured by time’s unrelenting blitz. In a still frame, he is looking back on his career with wide, unblinking eyes, taking it all in.

Maybe he could see the first game he ever played on that field, a Monday nighter against the Atlanta Falcons. This eventual titan of New Orleans sports would create many memories on that field, but his role in his debut was relegated to history’s footnotes. That night belonged to scrappy special-teamer Steve Gleason and the thunderclap his blocked punt sent rattling through the bones of a city rebirthing itself. That night belonged to the people of New Orleans, who announced to those who could hear their catharsis clear through the broadcast that they would not fold after the devastation wrought by Hurricane Katrina a year earlier.

Maybe he could see the most consequential game he ever played in that building, when he threw three touchdown passes to help the Saints defeat the Minnesota Vikings in the NFC championship

OPPOSITE: While walking off the field for the final time on Jan. 17, 2021, Drew Brees takes one last look back after the 30-20 loss to the Tampa Bay Buccaneers at the Mercedes-Benz Superdome. DAVID GRUNFELD / THE TIMES-PICAYUNE | THE ADVOCATE

RIGHT: Drew Brees greets his family after breaking the all-time NFL passing record on a 62-yard pass completion to wide receiver Tre’Quan Smith for a touchdown in the Superdome on Oct. 8, 2018.

DAVID GRUNFELD / THE TIMES-PICAYUNE | THE ADVOCATE

OPPOSITE: Drew Brees and Taysom Hill celebrate in the closing moments against the Washington Redskins. The Saints won 43-19.

MATTHEW HINTON / THE TIMES-PICAYUNE | THE ADVOCATE

“At the nexus of skill, intelligence and focus, there is Brees, beating the world’s premier athletes and defensive minds not only because he had the arm, but because he was so thoroughly prepared he knew where they all were going better than they knew it themselves.”

JOURNALIST LUKE JOHNSON, ON DREW BREES’ IMPACT TO THE BIG PICTURE OF THE GAME

For many, Brees’ philanthropy meant as much to New Orleans as his on-field exploits did

BY RAMON ANTONIO VARGAS STAFF WRITER

Months after leading the New Orleans Saints to victory in Super Bowl XLIV, quarterback Drew Brees went on “60 Minutes” and first uttered the credo that defined his relationship with the Black and Gold faithful: “If you love New Orleans, it will love you back.”

The superstar backed up those words, not only by passing his way into the NFL history books, bestowing 15 unforgettable football seasons on the Crescent City before retiring March 14, 2021. He also pursued philanthropy that for some had more of an impact than anything he ever did on the gridiron.

Generations of young athletes representing the Lusher Charter School Lions are in that number.

Brees and his wife Brittany had just arrived in New Orleans, in the desperate months after the federal levee failures during Hurricane Katrina, when they were driving around and noticed Lusher community members cleaning up damage at the school’s Freret Street campus.

Brees approached, asked how to help and in short order financed Lusher’s weight room. He also helped the school build the world-class “Brees Family Field,” which that sliver of Uptown viewed as a symbol of revival after the storm brought the city to the brink of annihilation.

Lusher athletic director Louis Landrum, a 31-year employee of the school, said the transformation which Brees kickstarted at the campus “touched hundreds of lives.”

“You’re talking about … kids who he’s helped through his generosity and resources,” Landrum said. “That’s priceless to our school, our student body, to the community as a whole.”

Yet while Brees’ relationship with Lusher was among his earliest in New Orleans, it wasn’t the only one.

Brees’ NFL career began in 2001 with the San Diego Chargers, and he created the Brees Dream Foundation in 2003. Since then, he and Brittany say they have contributed more than $33 million to charitable causes worldwide.

A partnership with Operation Kids in his second year with the Saints raised $2 million — including $250,000 that the Brees family personally donated — to help rebuild schools, parks and playgrounds in his adopted hometown.

The pace only picked up from there.

For example, in the summer of 2019, Brees donated $250,000 to help build KIPP Believe, a school at Columbia Parc in Gentilly for students in kindergarten through eighth grade.

Columbia Parc is where the old St. Bernard

housing development — one of New Orleans’ roughest areas — stood before Katrina flooded the city. Nearly 700 mixed-income residential units that were completed in 2010 helped replace some of the homes that were lost in the wake of the storm.

However, one missing piece at the site was a school. And Brees’ quarter-million donation made a single campus a reality for a student body divided between two separate schools.

Then, when the deadly coronavirus pandemic disrupted the world last year, the Breeses again leapt into action. They donated $5 million to build multiple health care centers tailored to underserved communities throughout Louisiana in a partnership with Ochsner Health.

And a separate $5 million donation went from the Breeses to local food banks, including Second Harvest, to aid people struggling to make ends meet amid the pandemic, as well as the historic devastation that Hurricanes Laura and Delta wrought in southwest Louisiana.

Second Harvest president Natalie Jayroe said the donation could not have been more timely. At the height of unprecedented, colliding crises, the Brees family’s generosity allowed Second Harvest’s kitchen operation to go from producing

ABOVE: Drew Brees wows the kids with an exercise routine as he demonstrates the TRX Suspension Trainer bodyweight exercise system to students at Lusher Charter School on Nov. 7, 2011. TED JACKSON / THE TIMES-PICAYUNE | THE ADVOCATE

OPPOSITE: Drew Brees watches as he challenges student Troy Privott, 15, to pushups as he demonstrates the TRX system to Lusher students. TED JACKSON / THE TIMES-PICAYUNE | THE ADVOCATE

Sean Payton and Drew Brees spent 15 years together, forming a rare duo that lasted so long because of ‘mutual respect’

BY LUKE JOHNSON STAFF WRITER

He might have seen it then, the way the next decade and a half would unfold, when Drew Brees first saw Sean Payton drawing up some offensive plays.

There, in that room, the brand-new head coach of the New Orleans Saints was diagramming the way his brand-new offense would look under the direction of his brand-new quarterback. Joining them was then-quarterbacks coach Pete Carmichael, who’d spent the previous four years with Brees in San Diego.

Brees expected to be challenged by unfamiliar concepts. Instead, he watched as Payton scribbled plays Brees ran during his first five seasons with the Chargers. A confused Brees interrupted him, telling Payton he was expecting to see some West Coast offensive principles. He didn’t know they ran these kinds of plays.

“And he said, ‘Well, we don’t,’ ” Brees recalled.

“ ‘But I know this is what you do and this is what you’re really good at and it’s what you’re comfortable with. So we’re building this offense around you.’ ”

Brees then spent the next 15 seasons brilliantly operating the offense that was built from the ground floor with him in mind. He retired March

14 as one of the most prolific passers in NFL history. And, for the majority of his time in New Orleans, it was Payton’s voice in his ear calling the plays.

They arrived at this point together. They were equal forces behind the rise of what became one of the NFL’s model franchises, the symbiotic brains orchestrating the NFL’s most consistently potent offense. But the key is they have been partners since the very beginning.

It was 2006. Payton was a 43-year-old first-time head coach. Brees was a 27-year-old quarterback coming off a major injury to his throwing shoulder.

Carmichael was the wild card.

“We had one benefit, and that was Pete Carmichael was here in the building as a quarterback coach,” Payton said. “So he gave us insight relative to their terminology, how they called plays.”

It was a collaborative effort. Payton asked Carmichael, What were the concepts you guys did in San Diego that we need to have here — that he was comfortable with, that he had success with?

“So really, when this playbook got put together, it was grabbed from multiple playbooks, putting what we thought the best fit was for Sean and for

Drew, really working together,” Carmichael said.

It was early in the process — the Saints had not yet gone through so much as a minicamp — so Payton figured they had time to be flexible, to tinker and tailor the offense toward Brees’ strengths, building it around terms he was already familiar with.

“There were a number of plays we were able to take things that he knew, and really before we even gave it to anyone, we were able to adjust on the fly and jump on the computer, change how we called certain things,” Payton said. “It made it a little bit easier for him.”

It was simplifying the process of Brees’ transition to the team, yes. But to Brees, it represented much more. Even in the moment, he picked up on it.

Where he was anticipating a harder line, a first-time coach implementing a “my-way-orthe-highway stance,” he instead found someone who was adaptive, already thinking of the best way to put his individual players in the best position to succeed.

“So, right off the bat, I felt like this place was much different and Sean was much different,” Brees said.

“Being part of it for just a couple years was a real privilege for me. It was just an incredible dynamic.”

MARK BRUNELL

appeared in six playoff games in its history and had lost five of them. Payton and Brees won four of their first five playoff games together. They brought the city of New Orleans its first major sports championship with a Super Bowl title in 2009.

Brunell was there that night in Miami, when Brees was named the game’s MVP and hoisted the Vince Lombardi Trophy over his head as Payton stood behind him on the podium, fist raised triumphantly.

“Being part of it for just a couple years was a real privilege for me,” Brunell said. “It was just an incredible dynamic.”

That Brees and Payton were still partnered all these years later makes sense to Brunell. What he saw in his two years sharing a room and a sideline with them was two people who “always had their foot on the gas” in constant pursuit of something beyond what they’d already accomplished.

“I mean, they’re not content,” Brunell said. “I don’t even think they’ve talked about, Hey, gosh, haven’t we been a great thing? Hasn’t this been special?”

Dot. Dot. Dot.

Their union was as much dependent on their minds working in sync as it was on Brees’ ability to physically perform. This was the area where their shared mastery really took place.

The night before they began their 15th and final season of their partnership, Payton and Brees met as they’ve done hundreds of times before in the team hotel. With them were Carmichael and quarterbacks coach Joe Lombardi and backup quarterbacks Taysom Hill and Jameis Winston. One last time, they sifted through the dots. They called this meeting the “dot meeting.” It was a sort of final systems check before game day.

The process started Monday, after film review from the previous week’s game. Out came the call sheet for the upcoming matchup, and Payton and Brees started an exhaustive process of elimination, paring down the plays they liked for a particular week. It was all completely broken down by style and scenario. Three-, five- and seven-step drops. Play-action. Empty sets. Screens. Early downs, third-and-short, third-and-long, fourth down. Red zone. Two-minute. Each play Brees and Payton liked got a dot next to it. By the time Saturday arrived, they were finalizing the remaining dots.

Generally, McCown said, this sort of final meeting is typical. But not to the depth and extent the Saints took it, and not with the sort of unified hierarchy he saw between Payton and Brees.

“It’s like listening to Obi Wan Kenobi and Luke Skywalker talk about how they’re attacking the Dark Side,” McCown said.

“They know each other better than anybody at this point 15 years later,” Carmichael said before the start of the 2020 season. “And so being a part of that is special, to see how their minds think alike.”

There was a heightened sense of things the evening before game day, Brunell said. The meetings were intense and loose at the same time — focused, but confident. Not super-heavy. Never contentious, McCown added. It was an exercise that allowed Brees and Payton to, one last time, get inside each other’s heads.

Payton tried to intuit the things Brees really liked heading into a game. Brees said he tried to anticipate what Payton was thinking, too. They were thinking and thinking throughout the week, so their mind meld was more a reflex than anything once game day arrived.

“The more that we can be on the same page on

game day,” Brees said, “the more seamless and efficient we can both be.”

They had this expansive mental library at their fingertips. They were through the dots and they had a shared understanding of how a certain play would work against a certain type of coverage in a certain situation. Sometimes, they referenced the way certain plays worked against a particular look back in 2007.

Brunell loves thinking about those meetings, about the way they evolved in the decade since he was last with the club. He imagined how different they are now, with all this material to work with. He thinks back on the trust and respect he saw when they were in their fourth year together, and he’s sure that during those final years Brees went into games with the utmost comfort with what Payton would call.

Brunell was trying to place himself back in one of those meetings. He remembered the confidence, the way they were laughing and cracking jokes as they ran through the dots.

“And there’s no reason for those guys to be uptight,” Brunell said. “ ‘All right, we’re on the same page here? All right, let’s go do it.’ Then, 400 passing yards later, three touchdowns, 38 points later, they’ve done it again. It’s pretty cool.”

The meeting room wasn’t new anymore, and neither was the offense — it evolved as they did. Brees finished his Saints journey having appeared in 245 games, including the playoffs. Outside of his 2012 suspension, Payton was there in Brees’ ear for all of it — hundreds of games, for a thousand-plus practices, for tens of thousands of hours spent preparing in dark film rooms or hotel conference rooms.

“It’s been a pretty unbelievable journey when you think about it,” Brees said.