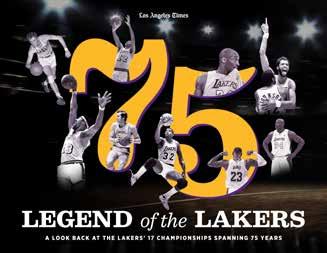

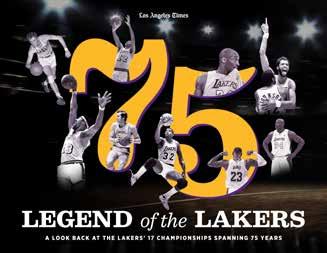

LEGEND of the LAKERS

A LOOK BACK AT THE LAKERS’ 17 CHAMPIONSHIPS SPANNING 75 YEARS

ON THE COVER

FRONT COVER: Now how did the Lakers fit so many basketball icons into 75 years? You’ll have to keep reading to find out. Relive some of the exploits of these stars plus many others. Just as a refresher, there are, from bottom left, Wilt Chamberlain, Jerry West, Magic Johnson, LeBron James, Shaquille O’Neal, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, Kobe Bryant, Elgin Baylor and George Mikan.

Credits

Los Angeles Times

EXECUTIVE CHAIRMAN

Patrick Soon-Shiong

PRESIDENT/CHIEF OPERATING OFFICER

Chris Argentieri

EXECUTIVE EDITOR

Kevin Merida

EDITOR AT LARGE

Scott Kraft

DEPUTY MANAGING EDITORS

Christian Stone, Julia Turner

ASSISTANT MANAGING EDITOR/SPORTS

EDITOR

Iliana Limón Romero

ASSISTANT SPORTS EDITORS

Houston Mitchell, Dan Loumena

‘75’ EDITOR

John Cherwa

DIRECTOR OF PHOTOGRAPHY

Calvin Hom

Copyright

2022 by the Los Angeles Times

All Rights Reserved

ISBN: 978-1-63846-044-2

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the copyright owner or the publisher.

Published by Pediment Publishing, a division of The Pediment Group, Inc. • www.pediment.com Printed in Canada.

This book is not endorsed by the National Basketball Association or the Los Angeles Lakers.

PHOTO EDITOR

Kelvin Kuo

DIRECTOR OF COMMERCE

Samantha Smith

COMMERCE COORDINATOR

Kailen Locke

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT/BUSINESS

DEVELOPMENT & COMMERCE

Lee Fentress

GENERAL COUNSEL

Jeff Glasser

the 75 Greatest Lakers

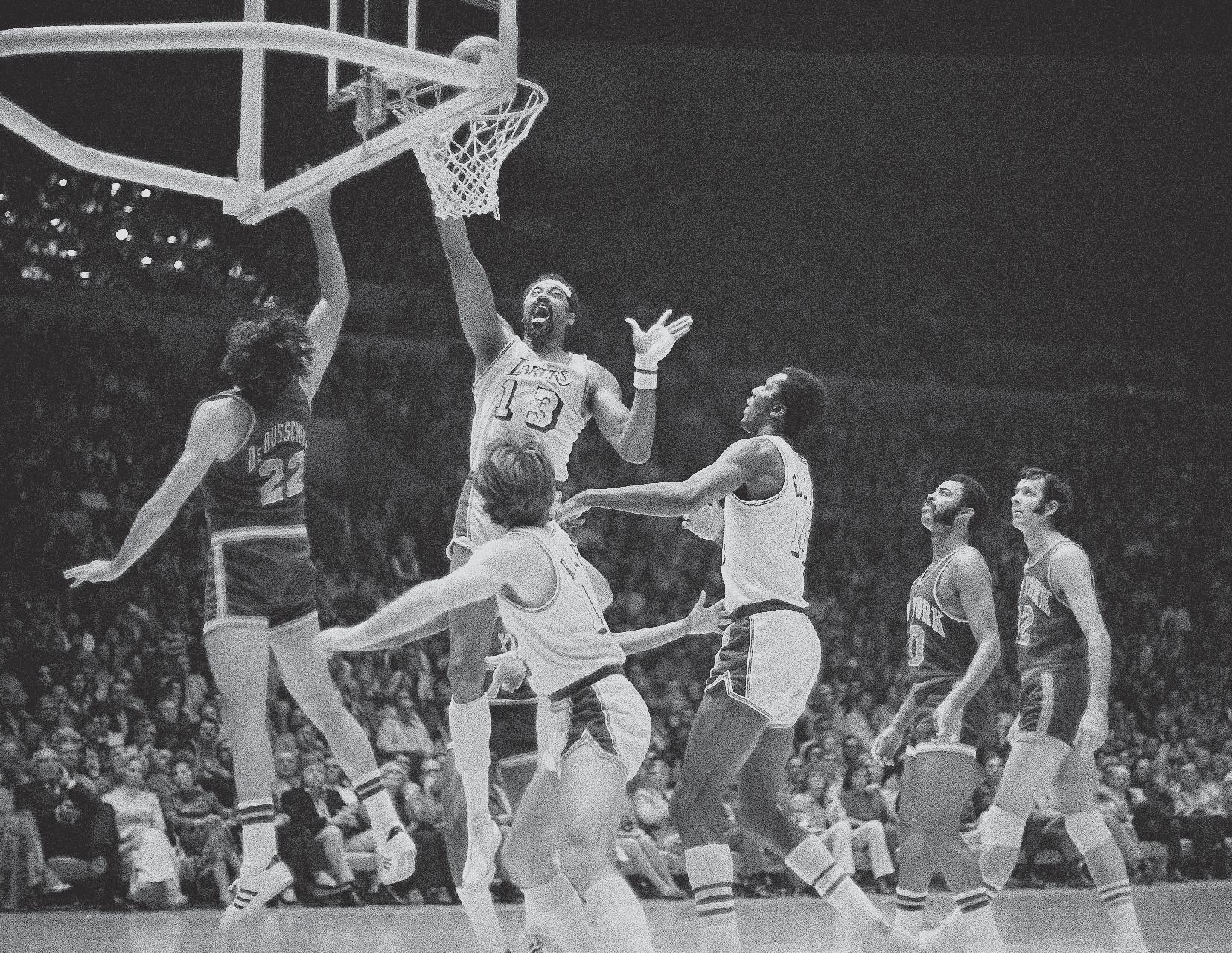

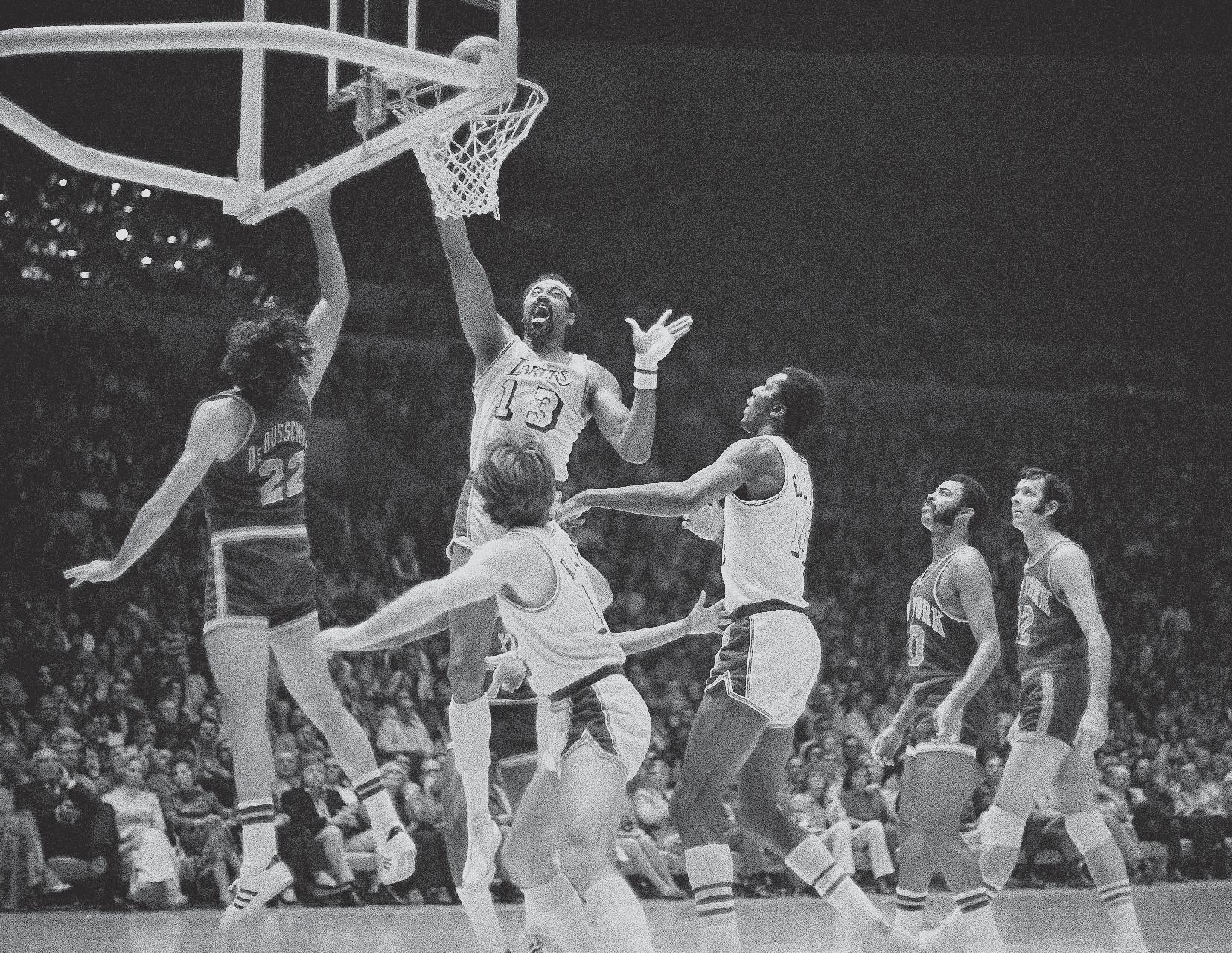

OPPOSITE: The Lakers went through a few dry spells during their 75 years, but 1971–72 was not one of them. That was the season they won 33 straight games, a record that stands today. The big man on that team was Wilt Chamberlain, here tapping in the ball during the NBA Finals against the New York Knicks. He was named the most valuable player in that series. Dave DeBusschere of the Knicks put up a futile effort to stop Chamberlain while Lakers Pat Riley, left, and Leroy Ellis are on the ready if something goes wrong.

Nothing did.

DAVID

2 • LEGEND OF THE LAKERS Contents Foreword ������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 5 The Early Years ���������������������������������������������������������������� 9 Welcome to L � A� �������������������������������������������������������� 23 It’s Showtime ������������������������������������������������������������������� 47 The Kobe Era������������������������������������������������������������������� 85 He’s Gone �������������������������������������������������������������������������� 127 The LeBron Era��������������������������������������������������������� 139 The Future ������������������������������������������������������������������������� 151 Ranking

��������� 157

©

•

SMITH / ASSOCIATED PRESS

Your first Lakers Moment is only the start of a beautiful friendship

BILL PLASCHKE

It’s an informal introduction to the best of Los Angeles, a wondrous event inevitably experienced by all newcomers, an awakening much like the first view of the Hollywood sign, the first taco from a food truck, the first winter night spent soaking in a cool backyard breeze.

It’s your first Lakers Moment.

It’s the first time you realize the grip that this 75-year-old team has upon the soul of a city. It’s the first time you realize the Lakers are more than a basketball franchise, they’re a civic jewel, a community touchstone, a living monument to both the glamour and grit that Los Angeles holds so dear.

It’s the first time you realize they do more than play, they reach, they connect, they bond, they are a fabric that holds this beau tifully diverse and maddeningly disparate community together.

Everyone, it seems, remembers their First Lakers Moment.

Mine occurred when one colleague leaped into my lap, another colleague collapsed at my side, and I started screaming.

It was June 4, 2000, with 41 seconds left in Game 7 of the Western Conference Finals against the Portland Trail Blazers.

The Lakers were trying to reach their first NBA Finals with Shaquille O’Neal and Kobe

Bryant, but their chances looked grim as they trailed by 16 in the final seconds of the third quarter.

But in an amazing final dozen minutes, they came roaring back, their defense forcing 13 consecutive Portland misses, their offense making every big shot, they stole the lead and led by four in the final minute and…

Then it happened. That Lakers Moment. Bryant threw up an alley-oop pass that O’Neal slammed through the hoop with a victory-clinching play that literally made Staples Center shake. As Bryant coolly swaggered away, O’Neal danced crazily downcourt and jumped into the arms of teammates and history.

The comeback was a miracle. The Lakers were supernatural. The stakes were monu mental. The results were eternal. With that simple shovel and slam, a new era in greatness had officially begun, and everyone knew it.

As we watched the theatrics unfold from our press seats above midcourt, the Los Angeles Times team reacted like the ultimate professionals we were.

The great columnist J.A. Adande jumped so high, he fell into my lap. The legendary columnist Mark Heisler was so overcome, he curled up into a ball. And me, I just screamed, and screamed, and, in one way

or another, I pretty much haven’t stopped screaming about this team ever since.

The Lakers do that to you. The Lakers do that to Los Angeles. In their 75-year his tory, the Lakers have done that repeatedly while winning 17 championships — five in Minneapolis and a dozen in the Southland — while creating as many dramatics as any professional sports franchise in history.

The Lakers didn’t simply exemplify the modern sports experience, they created it.

The Lakers were home to the most cele brated owner in sports, swashbuckling Jerry Buss continually dropping jaws by paying big bucks, building winning teams, and dating younger women.

The Lakers were home to the most symbol ic figure in sports, Jerry West, playing with a posture so perfect, he became the league’s logo.

The Lakers were home to the most char ismatic figure in sports with no more iconic expression in America than Magic Johnson’s smile.

The Lakers were home to the most re nowned of all NBA play-by-play announcers, the great Chick Hearn, who not only narrat ed memories but invented phrases for them. Yeah, he’s the guy who first said, “slam dunk.”

The Lakers created NBA cheerleaders

OPPOSITE: Shaquille O’Neal and Kobe Bryant had one of the more mercurial relationships in sports. Here, in 2003 in a playoff game at Staples Center, things were good. There were a lot of those moments and even more special moments on the court. For some, the greatest moment was in Game 7 of the Western Conference Finals against Portland when a furious comeback ended successfully when Kobe threw an alley-oop to Shaq, who slammed it home. Game. Set. Moment.

LORI SHEPLER / LOS ANGELES TIMES

75 THINGS WE LOVE ABOUT THE LAKERS

Naming the 75 things you love about the Lakers is akin to picking your favorite child in a big family. We mean a really big family. But that’s what assistant sports editor Houston Mitchell was tasked to do. They aren’t in order and there is no central theme other than a list of sometimes simple, sometimes big things that connect a city to a sports franchise. So, follow along over the rest of the book, relive the moment or the person, wonder why something wasn’t included. But most of all enjoy the magical spot the Lakers have in your life.

INTRODUCTION • 5

INTRODUCTION

Back in the day, Mikan was the roots of the big-man family tree

J.A. ADANDE • JUNE 3, 2005

George Mikan died at age 80 this week, too soon for those who were close to him but, fortunately, not too soon for the Lakers, the NBA and everyone who benefited from this giant man who altered basketball.

They all had chances to pay their respects to him in the latter years of his life, before the diabetes whittled him down and the kidney problems took him away.

I remember the touching sight of Bill Russell helping Mikan step up to the stage so he could stand alongside the rest of the NBA’s 50 greatest players in a halftime cer emony at the 1997 All-Star game. It was an understated moment, a little payback from one of the great centers to his predecessor.

Mikan is at the roots of the NBA’s bigman family tree. From him, it branches out and the arguments grow. Russell or Wilt Chamberlain? Shaquille O’Neal? Kareem Abdul-Jabbar? Moses Malone? Hakeem Olajuwon? They all had their contemporaries, their rivals, arguments for and against being the best of their era or all time.

But there’s no debate about who came first and paved the way. George Mikan.

“He was a great hook-shot artist and he dominated,” said Harvey Pollack, the statisti cian and public relations man who has worked in the NBA in some form or fashion since the league’s inception. “There was no comparable center of his stature until Wilt came along.”

He received another tribute at the overdue — but certainly not underdone — homage to the Minneapolis Lakers at Staples Center on April 11, 2002, when the link from the franchise’s roots was officially acknowledged with a halftime ceremony that raised a banner to commemorate the five championships won in Minneapolis and another that honored their Hall of Fame coach and five Hall of Fame players, including Mikan.

Before the game, O’Neal — wearing the evening’s throwback blue uniforms with “MPLS” on the front — stepped into a darkened room to pose for pictures with Mikan. O’Neal doesn’t like to bow to anyone, but he knelt alongside Mikan, who was in a wheelchair. O’Neal flashed the big smile, then signed some autographs for Mikan’s family. He acknowledged that Mikan was the granddaddy of NBA centers.

O’Neal claims that he built Staples Center, but, in truth, neither that arena nor the Forum before it would have been construct ed had it not been for Mikan. He was the league’s first marquee name — literally, as the famous picture of the Madison Square Garden sign reading “Geo Mikan vs. New York Knicks” demonstrated. At 6 feet 10, Mikan established the NBA as the big man’s domain. He averaged 22.6 points a game, tame by today’s standards but dominant for his time.

In 1950, the Fort Wayne Pistons decided the only way to beat the Lakers was to keep the ball out of Mikan’s hands. So they held on to it as long as possible, shooting only when absolutely necessary.

The strategy worked — the Pistons won, 19-18 — but the thought of such low scores infuriated NBA President Maurice Podoloff, and for the 1954–55 season the league ad opted the 24-second shot clock created by Syracuse National owner Danny Biasone. Another rule change directly attributed to Mikan was the widening of the three-second lane from six feet to 12.

“His style of play is nonexistent today,” Pollack said. “No. 1, you can’t stand that close to the basket. Secondly, he was a big guy. He wasn’t the king of speed. He had a lot of weight.”

Pollack was struck by Mikan’s size even in the later years of his life. At an event during the NBA’s 50th anniversary season in 1996–97, Pollack found himself in a room with Mikan, Chamberlain, Russell and Julius Erving.

“[Mikan] was still big,” Pollack said. “Russell wasn’t that big. And [Mikan] was bulky. He had a lot of weight on him. Wilt was closer to him, but he was still broader than Wilt was. Wilt, of course, was taller than him [at 7-1].”

The sad thing was that even a child

OPPOSITE: There is no question who the big man is in this photograph. George Mikan gets an old-fashioned hair mussing after scoring 48 points against the New York Knickerbockers on Feb. 22, 1949. (Congratulatory celebrations have gotten a bit more intense in later years.) At that time, it was the most points ever scored at Madison Square Garden. In fact, the 101 points the Lakers scored that night was also a Garden record.

THE EARLY YEARS • 15

ASSOCIATED PRESS

Worthy decides to hang it up, and Lakers to do same to ‘42’

SCOTT HOWARD-COOPER • NOVEMBER 11, 1994

He was Thursday as he had been for his previous 12 years as a Laker, eloquent and graceful, soft-spoken about his accomplish ments, an athlete relating the frustration of a once-great body wearing out and making it all seem so reasonable.

James Worthy said his knees had given out more than his will had. The end, he in sisted, came not after serious contemplation following the sudden death of his mother, or after struggling with a reduced role on a team whose other players talked of having watched him in the NBA finals as junior high students, but after being struck with the achy joints of April and May in October. Two-a-days had hurt too much, he said, and he could imagine how he would be feeling by Game 63.

So, he retired, making it official at a crowded Forum news conference and bring ing the curtain down on an era in the process. Magic Johnson, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Michael Cooper, among others, were there to say goodbye to a friend — and the last link to Showtime.

“I’m happy that we can see James go out and we can all smile,” said Abdul-Jabbar, the former captain. “We’ll shed some tears later, but we can smile because he’s walking out happy, the way he wants to leave.”

He won’t be entirely gone, either. Worthy said he might go into broadcasting and will

probably stay close to the game, but, in any capacity, he will be part of the Forum. Owner Jerry Buss has decided to retire Worthy’s No. 42 and hang it alongside those of the Laker immortals: Wilt Chamberlain, Elgin Baylor, Jerry West, Abdul-Jabbar, Johnson. No date has been set, but the ceremony may be held in December.

That isn’t Buss’ only tribute to the sev en-time all-star. Retirement could have meant that Worthy was walking away from a contract that would pay $7.2 million this season and $5.15 million in 1995–96, or at least that he would have to settle for a percentage as a buyout. But he will be paid in full.

“You make a commitment to do some thing, so you do it,” said Bob Steiner, Buss’ spokesman. “The same things were always true with [Johnson’s] contracts and everyone else’s contract. You sign an agreement to pay him. If you’re not obligated to it legally, you certainly are morally from what James has meant to Jerry’s happiness. Look at what the guy’s done.”

Buss is also paying $14.6 million worth of happiness to Johnson this season on a contract that was signed even as all parties realized that Magic would not be playing. In business, they call it a golden parachute.

Around the Laker front office, where $26.95 million is now earmarked for two former

players, it’s known as thank you.

What it means to the future of the Lakers is quite different. Because of a salary-cap technicality, they will have $1.85 million to pay another player, good until Nov. 10, 1995. That would seem lucrative enough to lure a good free agent, although probably not a top-level talent.

Worthy, 33, alluded to the front office — primarily Buss, Executive Vice President West and General Manager Mitch Kupchak — during his remarks, noting that he played with legends and worked for legends. But the most insightful comments were saved for his decision to retire after 12 seasons and three championships.

“The thing that really wore on me was that I could only play one way,” he said. “Some players, when they get older, they have a tendency to be able to adjust and find a way to continue. I just couldn’t do it. I think I may have tried it this past year, to modify, because I knew the minutes were going to decrease, but it was a forced situation. I can remember when my alarm clock would go off and I would be right up, right to practice, ready to go. It was fun. It got to the point where you hit the snooze five or six times.

“I didn’t feel good physically, and I knew I couldn’t make the contribution that I needed and wanted to. So for the sake of the younger players that are really working hard, it was

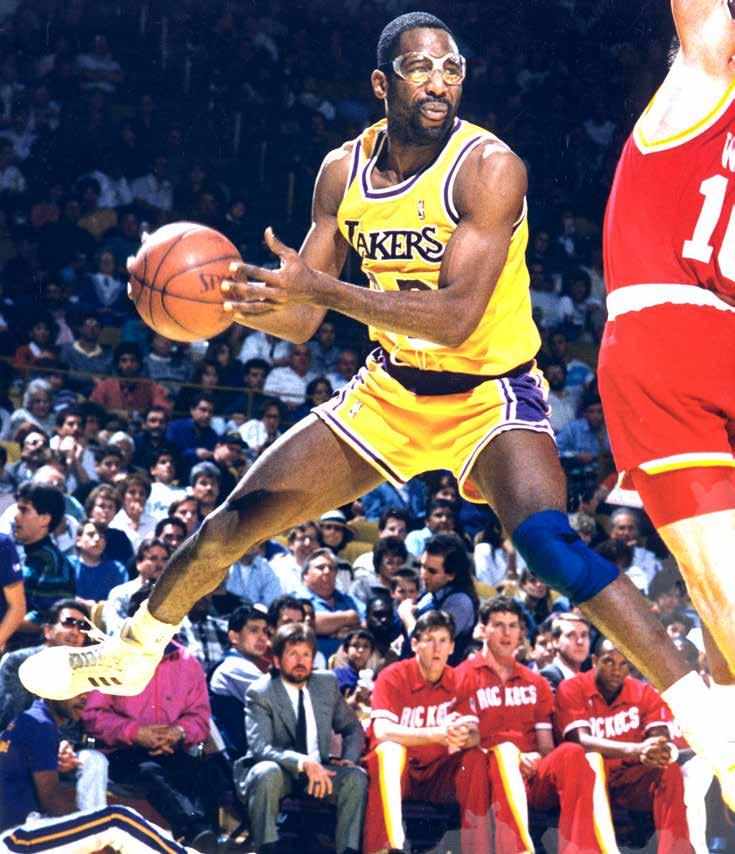

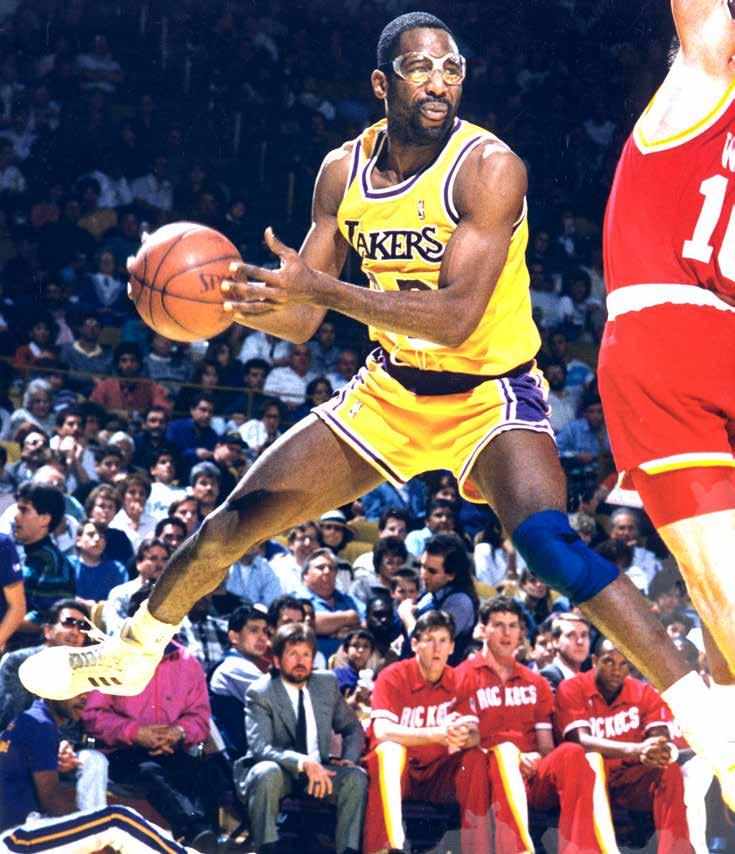

OPPOSITE: James Worthy earned the nickname “Big Game James” for his performances in the post-season. In fact, he averaged 3.5 more points in the playoffs than in the regular season.

LOS ANGELES TIMES

75 THINGS WE LOVE ABOUT THE LAKERS

Big Game James

Need a victory in a big game? Turn to James Worthy, who averaged more points, rebounds and assists in the playoffs than he did during the season.

Jack Nicholson

You know a franchise is instantly cool if the coolest actor sits courtside for every game and has a clause in his movie contracts that he has to be done early enough each day to attend Lakers playoff games.

Dancing Barry

Only the Lakers could have a guy in a cheap white suit dancing strangely be an unofficial mascot and make it seem like the coolest thing you have ever seen.

IT’S SHOWTIME • 73

a mutual agreement with Dr. Buss and the Laker front office. I was able to make some room and really avoid any further frustration or embarrassment that I might cause myself trying to compete when I knew it just wasn’t there.

“I definitely think it’s time for me. Parts of last year and a little bit of this year in training camp was like a test for me because I think you get to the point where you really aren’t sure if you’ve got enough left. So I’m almost sure that it’s the right time for me.

“I really feel relieved. I’m not looking back. I’m really just feeling very light, very happy that I was able to come to a decision and have it be the right one.”

Thursday’s proceedings were as much a tribute as an explanation, recollections of a spectacular small forward who probably never got his due from fans outside Los Angeles be cause he played with and was overshadowed by Johnson and Abdul-Jabbar. Many looked upon him as a complementary player when, in fact, he was a star in his own right. He could run the wings, even at 6 feet 9, with Magic at the controls of the trademark Showtime fast break, then a moment later embarrass a defender with a quick spin move from the low post.

Worthy scored 16,320 points and stands 52nd on the all-time NBA list. He spent more years as a Laker than anyone other than Abdul-Jabbar and West. He was at his best in the playoffs — thus the nickname “Big Game James” — averaging 3.5 more points than in the regular season and being named finals MVP in 1988. He got his first triple-double in that series — in Game 7. He got his career-best 40 points in the champi onship series the next year.

Johnson rates him as the second-best fin isher on the break the game has seen, behind

74 • LEGEND OF THE LAKERS

Tales from press row: What it was like to cover the ‘Showtime’ Lakers

RANDY HARVEY • JUNE 14, 2009

The headline over a science story in The Times this week read, “In a Universe of Wonders, Remembering to Be Awed.” That reminded me of a conversation I had when I covered the Showtime Lakers 20 years ago.

Bill Dwyre, the sports editor, summoned me to his office one day and warned me about my cynicism, borne no doubt of covering too many Cub games for a Chicago newspaper. He told me to maintain a critical eye but also to make sure that I provided readers with a sense of how special that team was. I should, in short, remember to be awed.

It wasn’t difficult. With Magic Johnson and Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, it seemed at the time that the Lakers had the basketball equivalent of Ruth and Gehrig.

There was a question in the early ’80s about whether it was Kareem’s team or Magic’s team, but it was clear not much longer into the decade that it was Magic’s.

Abdul-Jabbar was “Cap” to his teammates, an acknowledgment of his role as the captain and, I assume, his stature in the game.

But Pat Riley told me once that the players thought Abdul-Jabbar, because of his appearance on the court — his height, the way he flapped his arms when he ran, his aviator goggles — and his standoffish demeanor off the court, was goofy. That was his word. Goofy.

His teammates used to enjoy games more

when he wasn’t in them, because of an injury or one of his frequent migraines. Riley called them “the Greyhounds” because, without having to wait for Abdul-Jabbar to set up the offense, they could run for 48 minutes.

Of course, they had to have known in their heart of hearts that they wouldn’t win as many titles as they eventually did — five — without him. He had the greatest offensive weapon in the game’s history, the unblockable sky hook, and used it to become the NBA’s all-time leading scorer.

His rebounding was often criticized, not unfairly. Annual stories in the HeraldExaminer quoting Wilt Chamberlain on that subject infuriated Abdul-Jabbar so much that he stopped talking to the paper’s beat writer, Rich Levin.

Abdul-Jabbar, though, was underappre ciated defensively. His role in initiating the heralded Laker fastbreaks with blocked or altered shots was often obscured by the resultant coast-to-coast charge of the lighter brigade that almost invariably ended with a basket after a brilliant pass by Johnson.

What more can be said about Magic? He hardly ever failed to live up to his nickname. Almost nightly, he did something that I had never seen anyone, including him, do before.

Some teammates, Norm Nixon in partic ular, weren’t as convinced as the fans were when Johnson arrived in 1979 that he was

the miracle child. Ironically, he won over teammates in the same moment that he, at least temporarily, lost many fans.

That was on the night in 1981 in Salt Lake City that he demanded to be traded because he didn’t believe either he or the Lakers could reach their potential with the half-court offense coach Paul Westhead was trying to teach them. Westhead was fired the next day and Johnson, as the inmate who supposedly was running the asylum, was booed, even in the Forum.

The fans eventually forgot, but Johnson’s teammates didn’t. Most of them didn’t like Westhead’s system, either, but they didn’t say anything publicly for fear of the backlash. It was a different time, and they didn’t know how it would be received if black players criticized a white coach.

So Johnson did it for them. One reason was that he could. Jerry Buss wasn’t going to fire him. The other reason was that he knew it was his responsibility if he wanted to become the team leader, which, by virtue of his action, he did on that night in Utah.

His teammates would follow him any where, a faith rewarded most definitively a few years later when he led them down the fire escape after their Philadelphia hotel almost went up in smoke.

One question that comes up a lot these days is whether the Kobe- Shaq Lakers could

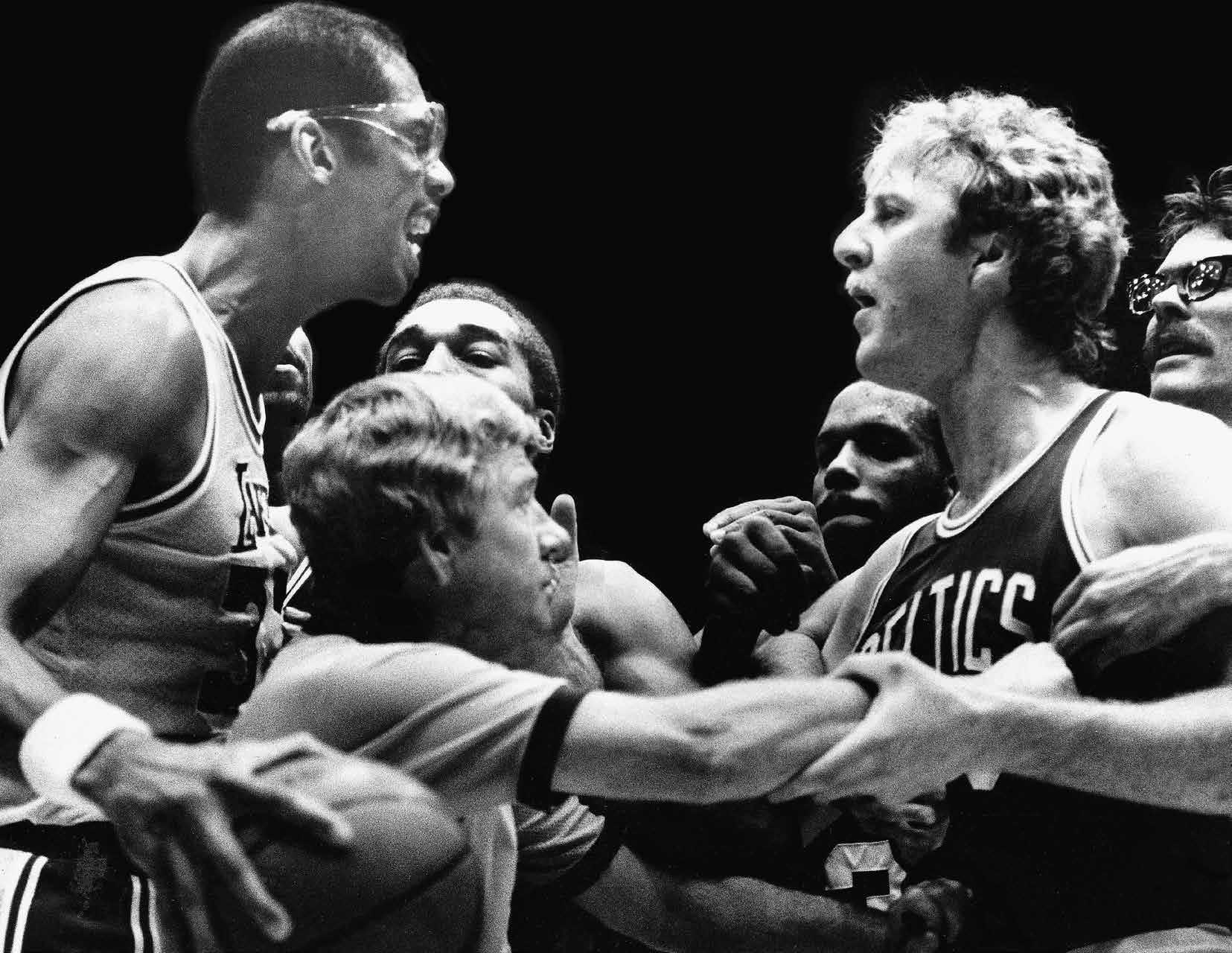

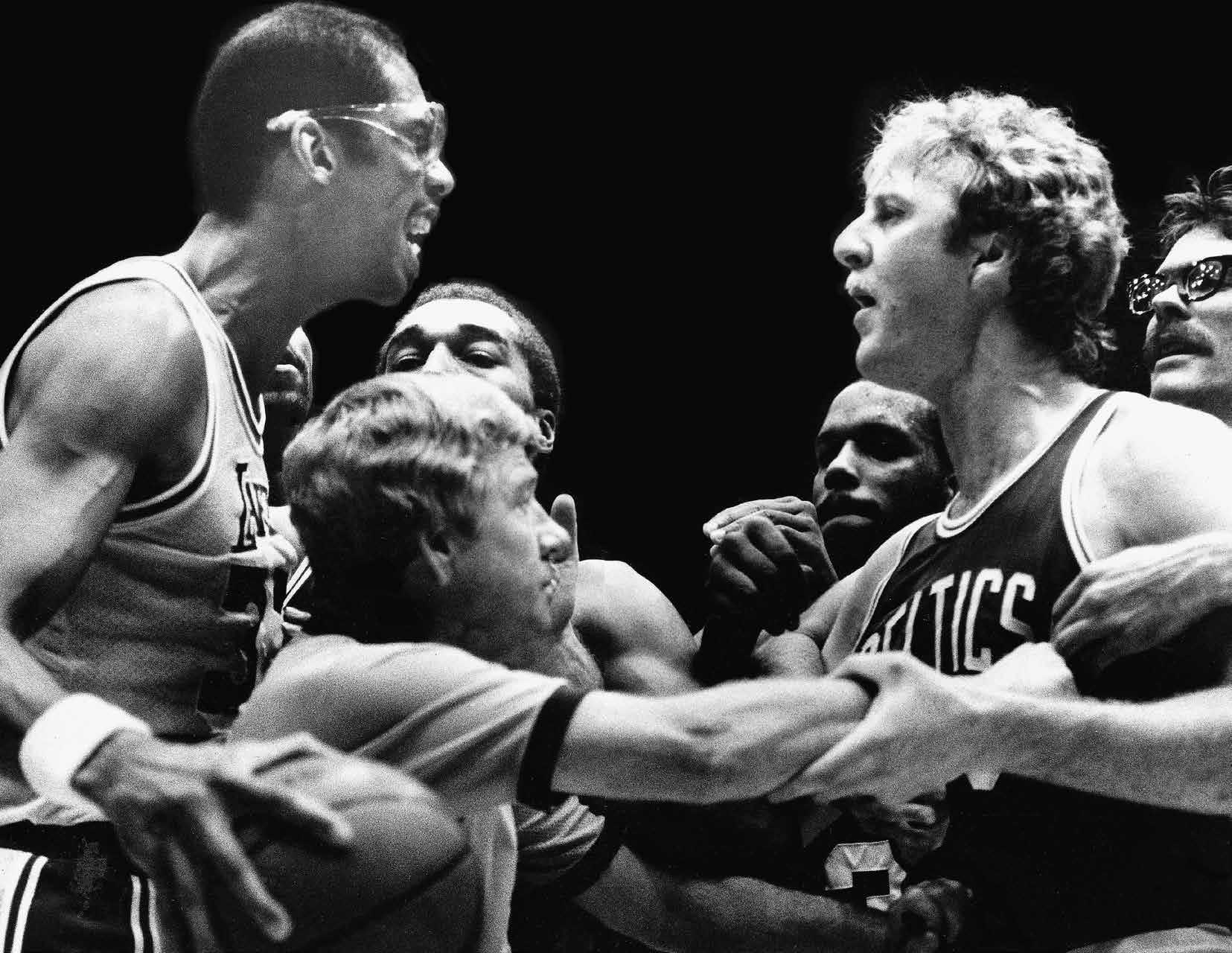

OPPOSITE: The Showtime years of the Lakers brought many memories. They were competitors and they showed up every game. Here, two legends of the game, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Larry Bird square off during the 1984 NBA Finals. The Celtics won in this Game 4 and went on to win the series, 4-3.

75 THINGS WE LOVE ABOUT THE LAKERS

Guaranteed

At the parade for the 1986–87 champion Lakers, coach Pat Riley stepped to the microphone and “guaranteed” the Lakers would win the title again the following season. They did.

Nicknames

Zeke from Cabin Creek. Cap. Magic. Mr. Clutch. Mr. Basketball. The Black Mamba. The Logo. The Big Smooth. Superman. Clark Kent. Big Game James. Big Shot Rob. No team has had better nicknames.

Stu Lantz

They finally found the perfect broadcast partner for Chick Hearn. He has continued to broadcast games after Chick’s passing and celebrated his 35th year with the team in 2022.

IT’S SHOWTIME • 77

LORI SHEPLER / LOS ANGELES TIMES

A look back at when Kobe Bryant humbly began his leap to the pros

HELENE ELLIOTT • OCT. 15, 1996

Behind him, clouds brushed the tops of the Santa Monica Mountains and the sun gilded the ocean, but Kobe Bryant was oblivious to the stunning backdrop at Will Rogers State Beach.

For more than two hours Bryant, the high school sensation who has yet to play a game with the Lakers but already has an Adidas contract and a Screen Actors Guild card, concentrated on soaring skyward for layup after layup while a photographer snapped images for a poster.

Eyeing the rim, mentally counting the steps, he was poised for another attempt when a photo assistant stopped him. Bryant paused, listened, then looked away in embar rassment as the assistant knelt at Bryant’s feet and tied the budding star’s shoes.

His mother, Pam, laughed at the deference shown her 18-year-old son. “I hope he doesn’t wait for me to do that for him,” she said.

Not a chance. An endorsement contract and roles on the TV shows “Arli$$” and “Moesha” haven’t inflated Kobe Bryant’s ego. Nor are big paychecks and fawning fans likely to change him, thanks to the lessons Pam and her husband, Joe — known as “Jellybean” during his eight-year NBA career — taught their three children about humility, respect and the importance of family.

“It’s crazy,” Bryant said of the fuss stirred by his incipient stardom. “If you sit back and start thinking about it, maybe you could be overwhelmed by the situation. You’ve just got to keep going slowly and keep working hard on your basketball skills. Then, I don’t think your head can swell because you won’t have time to think about it.”

Bryant didn’t go on a wild shopping spree after signing the Adidas deal or his threeyear, $3.5-million contract with the Lakers, who acquired his rights from the Charlotte Hornets. When his sister Shaya borrowed his sunglasses during the summer, he simply went without until he was given a pair he modeled in an advertisement.

“I’ve never enjoyed shopping,” he said. “I don’t have the patience. I’m usually playing basketball with one of my cousins …. I like to buy my sisters clothes because I want them to look pretty and I know they like to look pretty. I’ll go shopping with them because I want to make sure they don’t buy something that shows off their figures too much. I’m afraid of all guys when it comes to my sisters. I’m very protective, and they’re the same way with me.”

When he found an ocean-view house in Pacific Palisades, he invited his family to move in. Pam, Joe — who gave up an

assistant coaching job at LaSalle — and Shaya, 19, accepted. Sharia, 20, stayed in Philadelphia, where she is a senior volleyball player at Temple.

Pam and Joe plan to fly east occasionally to watch Sharia play. It’s only fair, considering that during Kobe’s senior year at Lower Merion High in the Philadelphia suburb of Ardmore, three generations of relatives on both sides of the family — most of whom live within a seven-mile radius — gathered to cheer him on.

The Bryants are openly and unapologet ically affectionate, and not only with each other. Pam is apt to invite home to dinner someone she has just met, or offer her jacket to a chilled bystander watching Kobe’s photo session.

“After a game, it’s nothing for Kobe to come over and give me a kiss,” she said. “My daughter [Shaya] is 6-2 and she’ll sit in my lap. They just do things that are not consid ered cool by other kids, and they don’t care.

“Once, Kobe had the flu and was pretty sick and insisted on playing because it was a big game. He sat on the other end of the bench because he didn’t want to spread germs. He played, and he played fantastic. He went back to the bench, and I saw he had a towel around his shoulders but he was

OPPOSITE: Kobe Bryant was no stranger to photo shoots even as a rookie. It comes with the territory when you are as big of a game changer as Bryant. Here, he was part of an elaborate set up to pitch products for adidas at Will Rogers State Beach. KEN HIVELY / LOS ANGELES TIMES

THE KOBE ERA • 85

THE KOBE ERA