Introduction

When Harry S. Truman, the prohibitive underdog in the 1948 presidential election, pulled off an upset victory, a famous photo captured the shock. It showed the gleeful president holding up the Chicago Tribune, whose early-edition headline, “Dewey Defeats Truman,” was amazingly, gloriously wrong. Lots of people had predicted Truman would lose, but here his ouster was proclaimed a done deal. It was a colossal error because the front page of a newspaper was where you absorbed the latest events and didn’t doubt what you read. Mistakes this basic were unthinkable. For Truman, it also didn’t hurt that the Tribune had once called him a “nincompoop.”

The front page was a cultural fixture, the place where the day’s biggest stories appeared so readers knew what demanded their attention first. Throughout the 20th century, it was also something else: the place where stories were arranged with headlines and photos under the Gothic letters of the nameplate as a kind of public artwork, a souvenir of a given day. As a quiet day was soon forgotten, so was its front page. A consequential day lived on in memory, and its page, yellowing in the attic, preserved the scope, immediacy and excitement of what had happened.

Like any newspaper, The Day covered the 20th century’s national news and produced pages for every vote, calamity and declaration of war. But in southeastern Connecticut, we also had our own news, and it was tailored to who we were and where we lived. Our big headlines were about shipwrecks and submarines and hurricanes. They chronicled fires and murders, the founding of institutions and the workings of state politics. As with each moon landing and assassination, The Day produced a front-page souvenir for everything local, from the launch of the Nautilus in Groton to the collapse of a dam in Norwich.

This book collects some of those pages from The Day’s first century, spanning 1881 to 1981. The focus is local events, many of which can’t be read about anywhere else. But there’s also a smattering of national news, because you can’t do a book like this and leave out the Titanic. Most pages are accompanied by brief background on the big story or, in some cases, a word about what happened later.

While the book recalls events, it’s also about the newspaper that reported them. The Day is part of the fabric of southeastern Connecticut, its primary source of local news. Some of the pages included here are significant for how they reflect the paper’s history. In cases where a story needs no explanation, there’s a quote from a Day editorial, giving a hint of the paper’s voice and what it said about how news affected ordinary people.

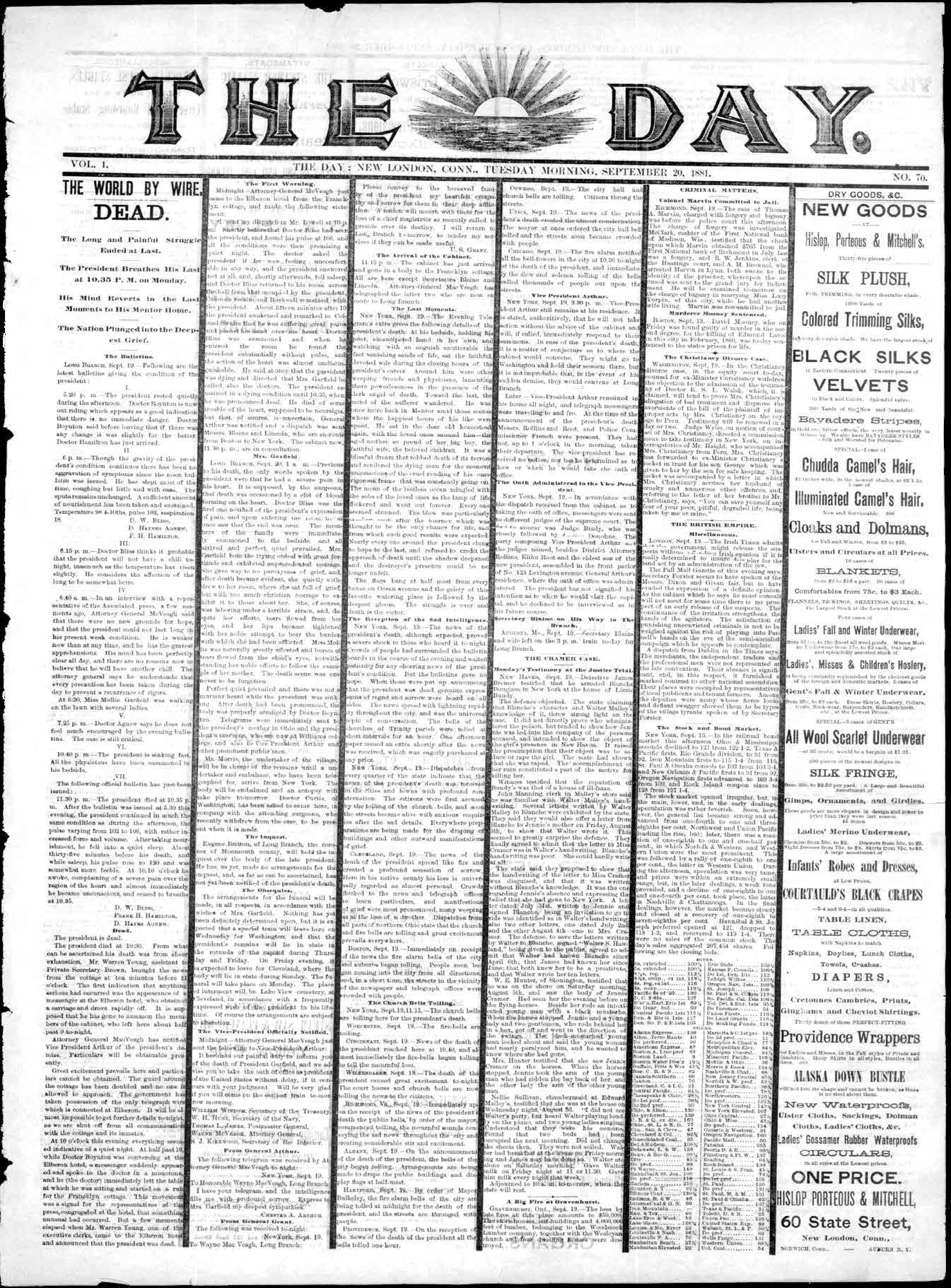

These pages weren’t meant for future generations because, in most cases, there just wasn’t time. The deadline rush and the limits of mechanical typesetting (as seen with the page at left) made perfection impossible. The news was often still unfolding as the paper went to press. Death tolls, official comment and available information changed at the drop of a hat. In some cases, what posterity has judged important seemed less so in the moment, and stories were underplayed before their impact was obvious. Likewise, the pages vary in quality as works of art. Some hold up well, while others suffer from a dull photo, an awkward headline or a confusing layout. But they freeze moments in time, and their imperfections reflect the hurly-burly of getting the news out fast. That’s part of their appeal. On Election Night 1948, the Chicago Tribune’s final edition declared, “Truman wins by 2 million.” But who remembers that?

This is the page at left as it appeared in print.

Copyright © 2024 by The Day • All Rights Reserved • ISBN: 978-1-63846-127-2 No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission of the copyright owner or the publisher.

The Day published its first issue on July 2, 1881. The story goes that the new publication’s name was a tightly kept secret, not even appearing in the typeset pages until three-letter placeholder words like “dog” and “cat” were replaced at the last minute. A few of those words supposedly made it into print by accident. For unknown reasons, an intact copy of the inaugural front page has not survived.

The 100th anniversary of the burning of New London and the Battle of Groton Heights was a major event, and The Day arrived just in time to report on it. Famous visitors included Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman and the USS Constitution, or “Old Ironsides.” The sky was yellow throughout the celebration, and seasoned mariners feared a hurricane, but the color was caused by an enormous wildfire in Michigan.

The Day’s debut on July 2, 1881, had been plagued by unfortunate timing. After the paper went to press, a gunman shot President James Garfield, with the next edition two days away because of the weekend. Garfield lingered for two months, and his death on Sept. 19 was reported with traditional black borders of mourning and an inelegantly terse headline. By then the paper was already sporting a new nameplate.

The Blizzard of 1888 was one of the worst snowstorms of all time, lasting several days, halting rail traffic and cutting off news from the outside as telegraph wires blew down. Seven years into its history, The Day was on its third nameplate, this one featuring a logo, or “dingbat,” that included the motto “It shines for all.” Coincidentally or not, that was also the motto of a more well-known paper, the New York Sun.

The Thames River’s first bridge was considered an engineering marvel and was the longest double-tracked drawbridge in the world. It eliminated the need for railroad cars to be ferried across the river, though non-rail traffic would continue to cross by ferry until 1919. The bridge was a symbol of progress, and two years after it opened, it became the main element in the redesigned “dingbat” of The Day’s nameplate.

New London celebrated its 250th birthday in 1896. One of the main events was the unveiling of the Soldiers and Sailors Monument on the Parade, a gift of Sebastian Lawrence of the Lawrence whaling family. The same day, a cornerstone was laid for the foundation of a statue of John Winthrop, New London’s founder. This is the cover of an eight-page pictorial souvenir booklet issued for the occasion.

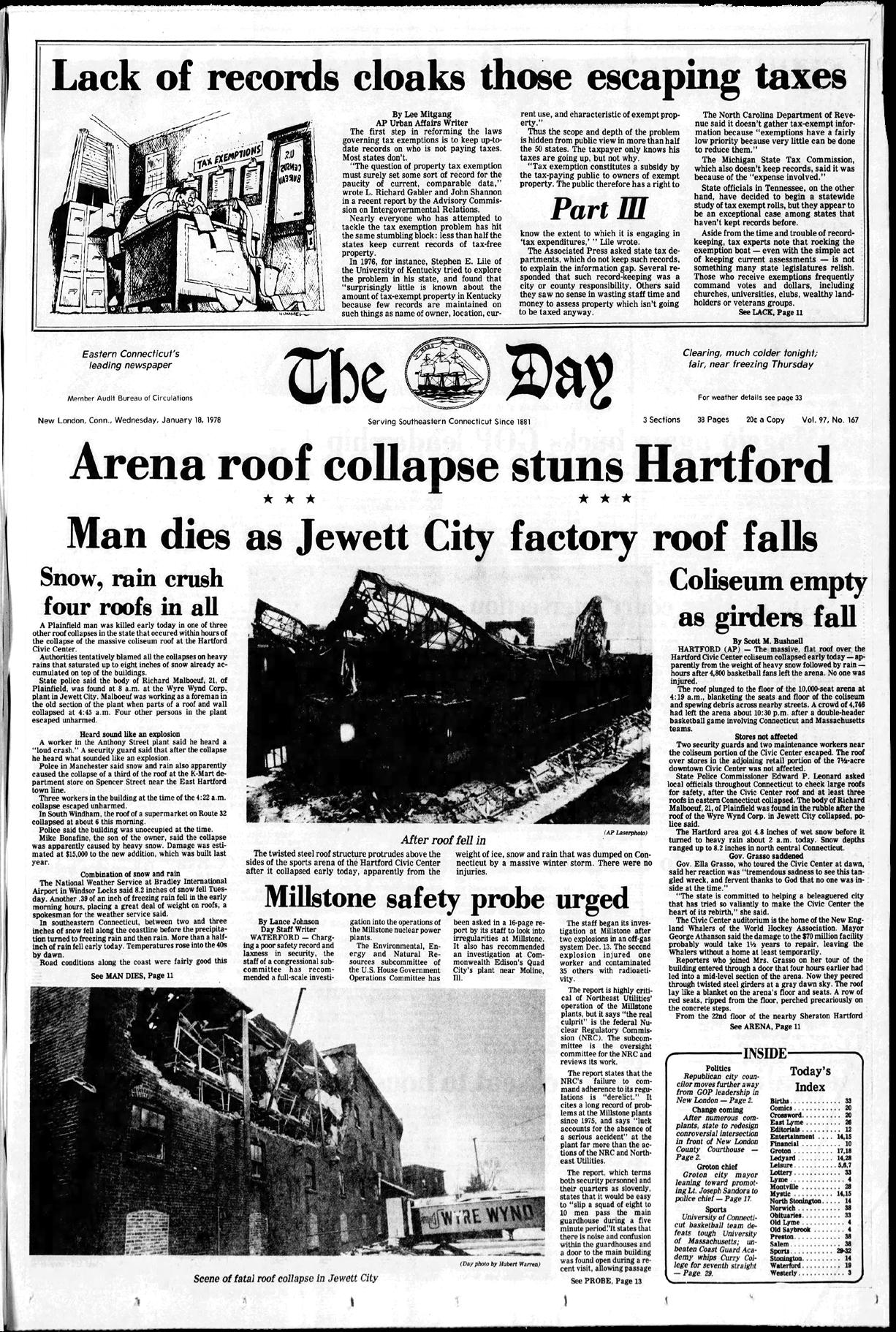

The Hartford Civic Center was only three years old when its roof collapsed in the middle of the night, hours after a UConn basketball game. Fortunately, no one was injured. Bad weather had lasted for days, capped by a snowstorm the night before the collapse, but design errors were found to be the cause. The 1,400-ton, 108,000-square-foot roof was rebuilt, and the building, now known as the XL Center, reopened in 1980.

The Blizzard of 1978 packed hurricane-force gusts, which pushed a foot and a half of snow into huge drifts. Travel came to a halt, and Gov. Ella Grasso memorably closed the highways. Possibly the craziest story to come out of the storm was about two men who set out in a small boat for a short hop from Fishers Island to Noank. Instead they were blown 40 miles to Long Island, where they arrived half-frozen but otherwise fine.

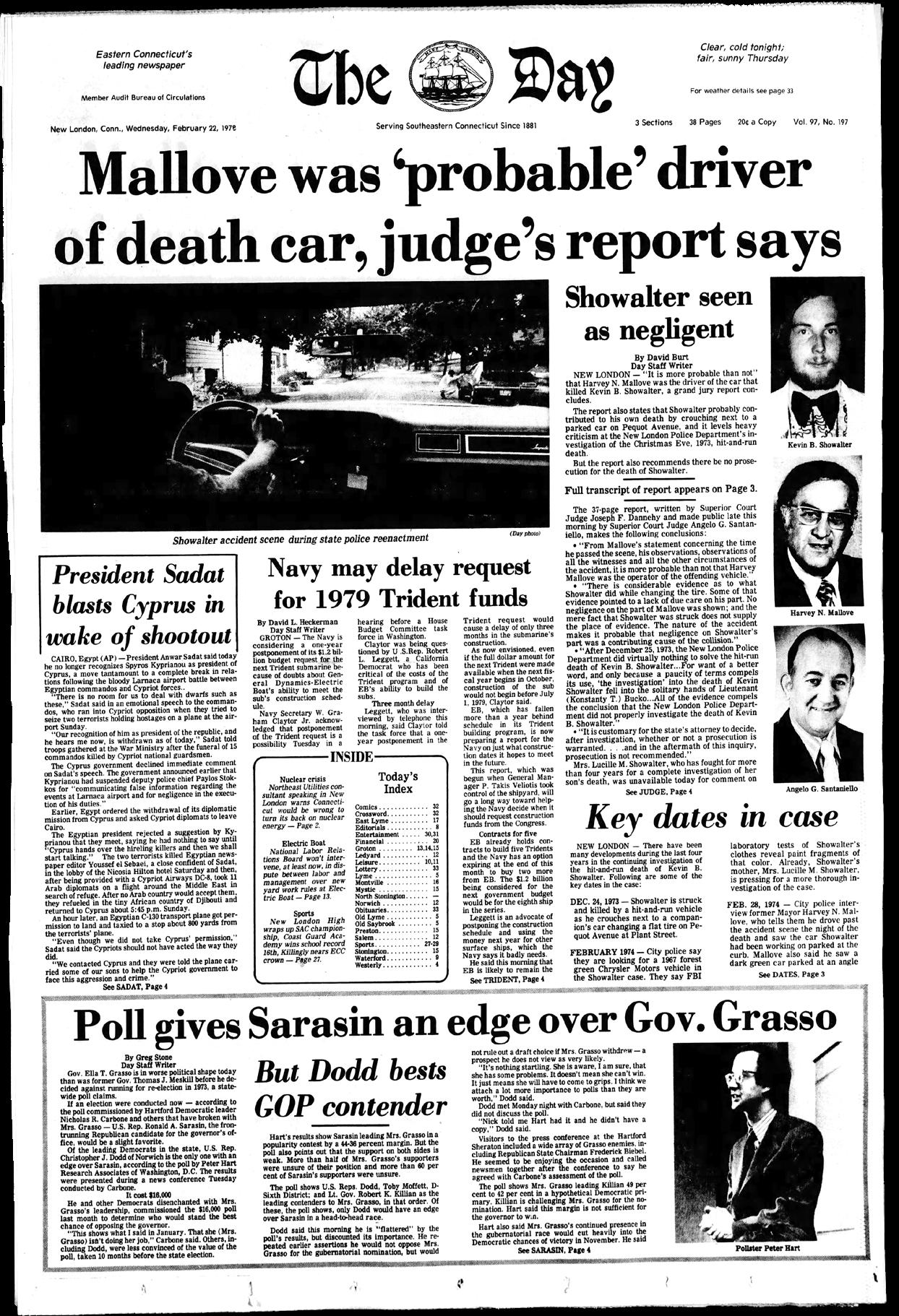

New London’s greatest mystery started on Christmas Eve 1973, when Kevin Showalter, 20, a Mitchell College student, was struck and killed by a hit-and-run driver while changing a tire. Three years later, a one-man grand jury implicated jeweler and former Mayor Harvey Mallove, who never got the chance to clear his name. Another man later confessed and committed suicide, but the case remains unsolved.

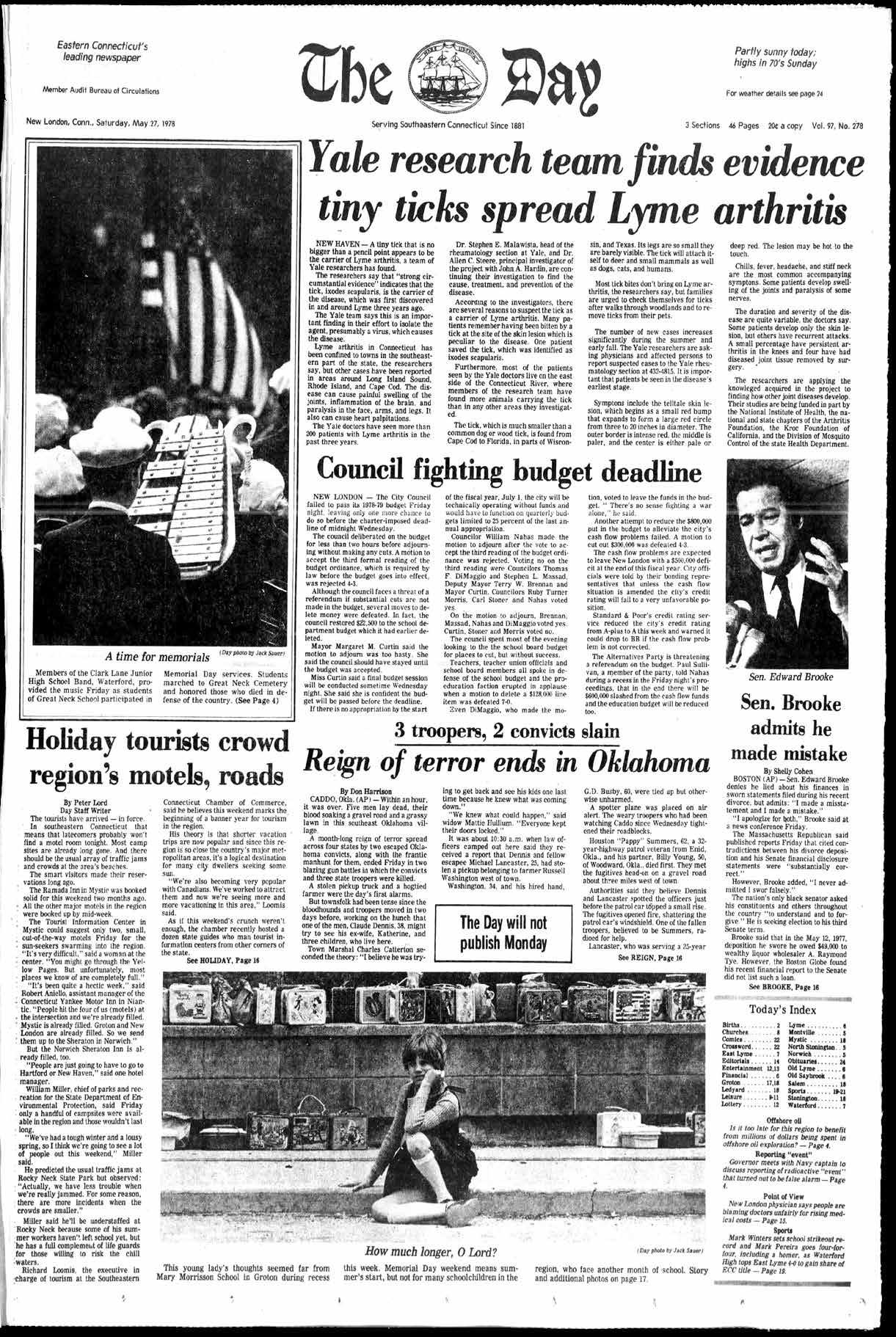

In 1975 a mysterious ailment was noted in dozens of people in Lyme, Old Lyme and East Haddam. It started with an expanding skin lesion and was followed by swelling of the joints. At first called Lyme arthritis, it’s now known as Lyme disease. Amid growing research, a big step in understanding the disease came in a 1978 Yale University study that found it was spread by deer ticks.

The christening of the Ohio (SSBN-726) marked the start of the Navy’s Trident ballistic-missile submarines, which will eventually be replaced by the Columbia class. The Ohio was the first EB-built submarine too big to be launched in the traditional slide down the building ways. The event spurred New England’s largest anti-nuclear weapons demonstration to date. First lady Rosalynn Carter initialed the keel of another sub.

Lighthouse Inn, a landmark hotel and restaurant in New London, had already survived one major fire in 1944 and endured through changing fortunes when flames again broke out in 1979. This headline jumped the gun, as the building, though heavily damaged, was not destroyed. It reopened for a while, then was shuttered for years. A third big fire delayed its 2022 reopening.