2021+

2022

Editors

Julian Graybill Brubaker

Helen Lea

Matthew Limbach

Environmental Readings 2021 + 2022

Editors

Julian Graybill Brubaker

Helen Lea

Matthew Limbach

© Trustees of the University of Pennsylvania

Published by: Ian L. McHarg Center for Urbanism and Ecology University of Pennsylvania

Stuart Weitzman School of Design

102 Meyerson Hall

210 South 34th Street Philadelphia, PA 19104

Designed by Helen Lea

All rights reserved. Neither the whole nor any part of this paper may be reprinted or reproduced or quoted in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or here-after invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without accompanying full bibliographic listing and reference to its title, authors, publishers, and date, place and medium of publication or access.

Cover photo:

Jenny Lake overlook at Grand Teton National Park, WY (Helen Lea)

Foreword

PART 1:

Robert

Kongjian

Kongjian

The

Are Landscape Architects Narrators?

Dingwen Wu 282

Looking for Love in Hybrid Places: The Values of Our Commercial-Natural Landscape

Charles Starks 287

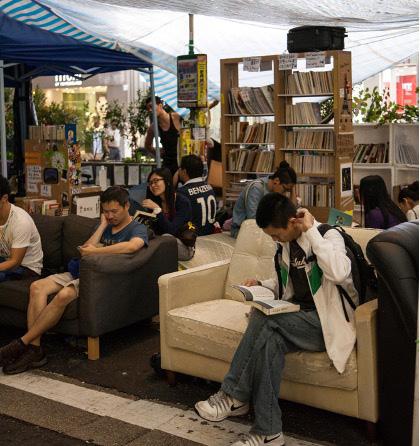

Human-Nature Relationships Influenced by Technological Evolution: How the Internet Reshapes Cities

Huiyou Ding 298

A Story of Community Engagement and 10 Learned Lessons

Yasmine McBride 304

Contributors

I learn so much from teaching and literally fall in love with every class. Each one is special to me and has a specific chemistry. Every time I teach Environmental Readings, I offer to help the students publish their papers. Two groups at University of Texas at Austin, where I taught for 15 years before coming back to the University of Pennsylvania, took me up on this. This collection is the first at Penn, and includes two classes, which are extra special because they are pandemic classes. The spring of 2021 class was hybrid, remote (in some cases over long distances) and in person. For some, it was their first time on campus. We navigated the unusual circumstances of trying to stay healthy as COVID kicked our butts. Even the spring of 2022 group—which, in theory, was in person—functioned in a somewhat hybrid manner.

Not all the students in the classes are represented in this collection. Some graduated, moved on, and are focusing on other things. Not all my students’ papers are included because—Good news!–– some were already published in other venues. Still, the papers stand as strong representatives of the Environmental Readings classes of 2021 and 2022.

Both classes included a healthy mix of students from within the Weitzman School––architecture, landscape architecture, and city planning––at the professional- and doctoral-degree levels and from the School of Social Policy and Practice.

Through the pandemic, the tide of interest in social and environmental activism rose, which was evident in what we read, what we discussed, and what was written. These “environmental readers” write about crime prevention, landscape urbanism, environmental racism, restorative urbanism, and the science of cities; as well as designers, scientists, and environmentalists including Larry Halprin, Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, Kongjian Yu, Buckminster Fuller, Denby Deegan (a Sioux architect), Jens Jensen, and Richard St. Barbe Baker; plus their own theories about landscape story telling, civility and disobedience, illumination, and suburbia. Although the seminar includes “reading” in its title, it is as much about “writing.”

Each of the three times we have published students’ papers, three student editors stepped forward to edit and design the publication. This year, it was Julian Graybill Brubaker from Social Policy and Practice, Helen Lea from Weitzman City Planning, and Matthew Limbach from Weitzman Landscape Architecture. I fall in love with every class but fall even harder for the student editors. I appreciate all this amazing trio has done to make this happen.

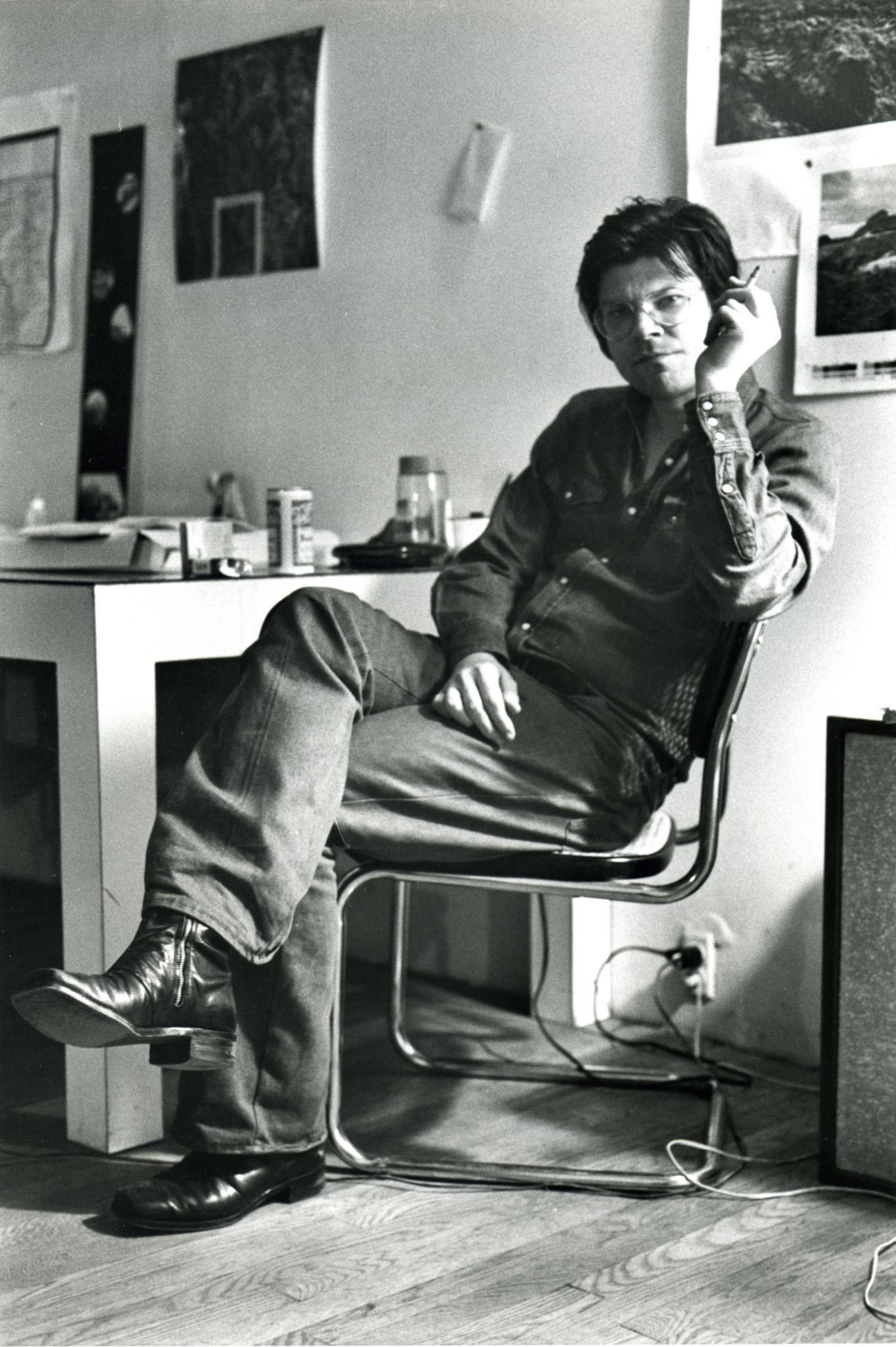

Robert Smithson (1938-1974) spent the first thirty years of his life exploring the existing art world. As he became increasingly preoccupied with the context for works of art, Smithson began to work outside, in natural sites ruined by industrial waste or mining, especially after 1968. Although he died in 1974 in a tragic accident, the last six years were an incredibly productive period when he produced many significant earth art works, and had very provocative philosophical and artistic ideas which have considerably inspired people about landscapes.

Robert Smithson was born in Passaic, New Jersey, and spent his childhood in Rutherford until he was nine. Then, his family moved to the Allwood section of Clifton, New Jersey. Smithson was largely a self-taught artist. He earned a two-year scholarship to the Art Students League in New York City from 1955 to 1956, where he studied painting and drawing. Then Smithson studied briefly at the Brooklyn Museum School in 1956. Through his studies and training, Smithson became fascinated with the Abstract Expressionists, particularly David Smith, Tony Smith, Jackson Pollock, and Morris Louis. Later in his career, Smithson observed that he found David Smith’s sculpture particularly captivating for its use of unnatural materials like steel that were altered by time and natural processes such as rust, decay, and discoloration. Through these studies, he was consistently drawing, painting, and making collages.1

“When a thing is seen through the consciousness of temporality, it is changed into something that is nothing. This all-engulfing sense provides the mental ground for the object, so that it ceases being a mere object and becomes art.”

- Robert Smithson

In the late 1950s, Smithson was noticed by the art dealer Virginia Dwan, and she organized his first solo show at the Artists’ Gallery in 1959. At this time, Smithson’s paintings, drawings, and collages drew in part on Abstract Expressionism; his works were multimedia, but were still two-dimensional artworks made by using gouache, crayon, pencil, and photography. Through his connection with Dwan, Smithson was introduced to several key artists and sculptors who were pioneering the Minimalist art movement of the early1960s including Carl Andre, Donald Judd, Robert Morris, Claes Oldenburg, and Smithson’s soon-to-be wife, Nancy Holt. Holt and Smithson married in

Oxted Quarry, Surrey, UK

Sixteen mirrors and chalk

Diameter 120 in. (304.8 cm)

Collection: Art Institute of Chicago

Photograph: Robert Smithson

© Holt/Smithson Foundation

/ Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

1963. The formation of all these friendships would mark a significant turning point in Smithson’s career.2

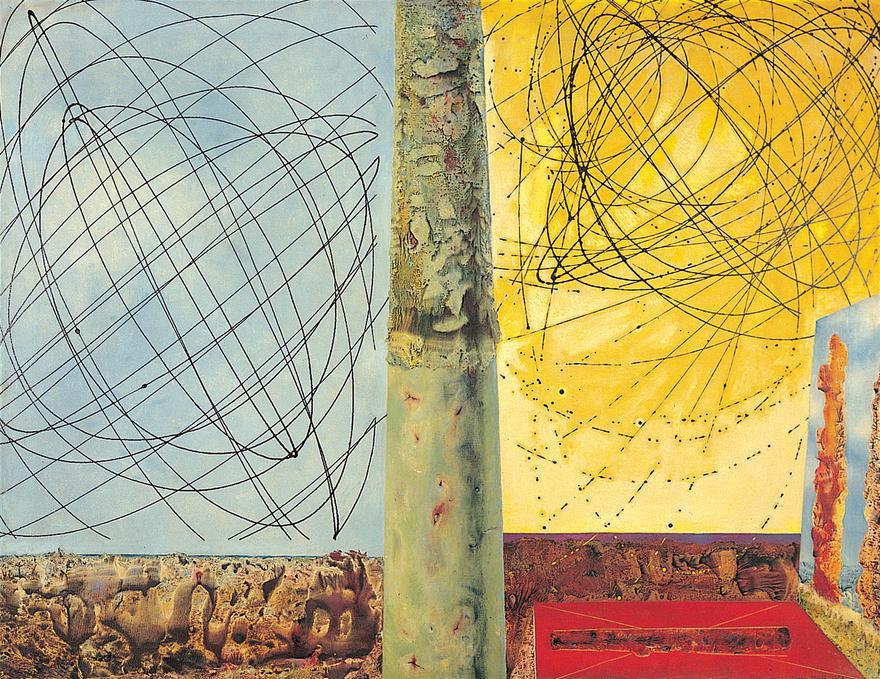

The collages Smithson produced in the early-1960s, including Tear (196163), Conch Shell, Spaceship and World Land Mass (1961-63), and Algae (c. 1962), are very much grounded in an abstract and expressionist aesthetic, but they clearly suggest the artist’s growing fascination with the earth as an inspirational resource and his concern with themes of permanence, natural and unnatural materials, and site-specific art.3

Throughout the mid-1960s, he made several trips to New Jersey to visit quarries and industrial wastelands. Smithson also paid several visits to the American West and Southwest, sparking an interest in deserts and sprawling expanses of land that appear unblemished by human intervention.

Sixteen mirrors and chalk

Diameter 120 in. (304.8 cm)

Collection: Art Institute of Chicago

© Holt/Smithson Foundation

/ Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

By 1967, Smithson was focused on two peculiar and interrelated forms of sculpture, Sites and Non-sites, using mirrors and natural materials to create a new form of three-dimensional work. Many of these Non-site projects would directly mirror his Sites, as in the case of Chalk Mirror Displacement (1969), a single work located in two different locales: its original quarry site in Oxted, England (Site) (Figure 1), and later in the gallery space (Non-site) (Figure 2). What made the Sites/Non-sites such a unique artistic endeavor was that Smithson was first altering the landscape, and then bringing the exhibition materials from the site into the gallery. Simultaneous with Sites/Non-sites, he was also creating a series of works called Photo-Markers (1968).

For the final six years of his life, certain innovative thoughts are reflected both in Smithson’s earth art and writings, including the picturesque, dialectical materialism, entropy, time, and sight of art.

Many of Smithson’s ideas about “picturesque” are described in his essay “Frederick Law Olmsted and the Dialectical Landscape.”4

A tree struck by lightning, for example, was something other than beautiful or sublime – it was “picturesque” because it has the feature of time. The picturesque, is based on real land; it precedes the mind in its material external existence. We should see landscape as dialectic rather than one-sided. Landscapes are processes of ongoing relationships existing in a physical region. That is how things become “picturesque.”

For Smithson, dialectics are a way of seeing things in a manifold of relations, not as isolated objects. Nature/landscape for the dialectician is indifferent to any formal ideal. Nature is unexpected. For him, Olmsted’s parks exist before they are finished, which means they are never finished; they remain carriers of the unexpected and of contradiction on all levels of human activity, be it social, political, or natural.5

To speak broadly, nature’s development is grounded in the dialectical, not the metaphysical.

That dialectical thinking relates back to Smithson’s understanding of entropy. In the essay “Entropy and the New Monuments”, Smithson expanded the Second Law of Thermodynamics – power disperses towards the maximum end of entropy.6 That is, entropy started from zero at the Big Bang of the universe, and keeps increasing, with everything being more and more disordered; as entropy expands, usable power keeps decreasing, until the very end of the universe. This is called “silent chaos.”

Smithson shows pessimism throughout his works of earth art. Compared to other land artists such as landscape architect George Hargreaves who

Rome, Italy

Sculptural event

Asphalt and earth

Photograph: Robert Smithson

© Holt/Smithson Foundation

/ Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Sculptural event

Glue and earth

Photograph: Christos

Dikeakos

© Holt/Smithson Foundation

/ Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

Great Salt Lake, Utah

Mud, precipitated salt crystals, rocks, water

1,500 ft. (457.2 meters) long and 15 ft. (4.6 meters) wide

Collection of Dia Art Foundation

Photograph: Gianfranco

Gorgoni, 1970

© Holt/Smithson Foundation and Dia Art Foundation / Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York

focuses on inspirations and mechanisms of nature, Smithson reveals more about how entropy works on the earth. Instead of pessimism, it is instead a simple statement of truth about the destined orientation of the universe.

Early Earthworks, such as Asphalt Rundown (1969) (Figure 3) and Glue Pour (1969) (Figure 4), were inspired in part by his interest in entropy and abstraction, since the dumped and cooled materials created hardened abstract forms that resulted from their loss of heat.

In addition to art, the manifestations of technology, for Smithson, are at times less “extensions” of people, than they are aggregates of elements. Even the most advanced tools and machines are made of the raw matter of the earth. Many art magazines have gorgeous photographs of artificial industrial ruins (sculpture) on their pages. The “gloomy” ruins of aristocracy are transformed into the “happy” ruins of the humanist; while Smithson approached those sites with a unique perspective, which is based on entropy.7

Smithson also had the idea of entropy reflected in other political thoughts. Democracy, for Smithson, is the political form of entropy, wherein social conflict is worn down. Democracy is always a failure, always a struggle toward entropy, yet always open to a restructuring because of its orientation to a primordial consciousness.8 9

Time

Throughout his career, Smithson became increasingly fascinated with the element of time and with humankind’s repeated attempts to control it. From the perspective of entropy, these attempts, according to Smithson, were foolish. He viewed any attempt to control time as tantamount to devaluing it altogether and defrauding the earth of its essential right to exist. He also presented this theme in his 1970 Earthwork Partially Buried Woodshed, located in Kent, Ohio, which consists of a woodshed partially buried under 20 truckloads of earth. This piece was “built” to illustrate the effects of geological time and its eventual consumption of all man-made endeavors. Incidentally, other major works, such as Spiral Jetty (Figure 5), would eventually be consumed temporarily by the waters that surrounded them, also indicating entropy. Similarly, the bedrock of Central Park, for Smithson, is simply the glacier dragging itself along.10

In “Frederick Law Olmsted and the Dialectical Landscape,” he writes that the best sites for earth art are sites that have been disrupted by industry, reckless urbanization, or nature’s own devastation. For instance, the Spiral Jetty is built in a dead sea, the Great Salt Lake, and the Broken Circle and Spiral Hill in a working sand quarry. Such land is cultivated or recycled as art.11

In Smithson’s view, Olmsted was a great artist who contended with magnitudes, and he set an example which shed a whole new light on the nature of American art.

Regarding art, Smithson theorizes on the climate of sight, which changes from wet to dry and from dry to wet according to one’s mental weather. The prevailing conditions of one’s psyche affect how he/she views art. The wet

mind enjoys “pools and stains” of paint. Such “wet eyes” love to look on melting, dissolving, soaking surfaces that give the illusion at times of tending toward a gaseousness atomization, or fogginess. “Paint” itself appears to be a liquefaction.12

Similarly, a “wet” mind enjoys landscape by extending the current sight to history and future, which reorganizes our personal memory and feelings. The landscape then becomes no solid morphology, and then becomes part of ourselves with the perspective of time. Landscape becomes art. In contrast, for Smithson, the stratum of the Earth is a jumbled museum. Embedded in the sediment is a text that contains limits and boundaries which evade the rational order, and social structures which confine art.

This kind of “wet sight” is also reflected in his early work Site and Non-Site He would allow the structures of the site materials to define his experience of sight. In this way he would begin to think like the site. In other words, our sight actually projects art to the world.

In “A Sedimentation of the Mind Earth Projects,” Art is considered “timeless” or a product of “no time at all.” Through the consciousness of temporality, a thing ceases to be a mere object and becomes art. Every object, if it is art, is charged with the rush of time even though it is static, but all this depends on the viewer. A great artist can make art by simply casting a glance. A set of glances could be as solid as anything or any place, but society continues to cheat the artist out of his “art of looking,” by only valuing “art objects.”13

For Smithson, art became a very personal thing. He did not think the site should determine the art. He was an advocate for ideas about the non-place, nonsite, non-environment. He thought art tended towards that; it was abstract. He did not like the idea of the public. It was not necessary. The artist is the most important person and does not need the public. He needed support to do his work. Whether or not the public liked it was irrelevant—it should not depend on public involvement. The only person that should be involved is the artist, so they can follow out their states of consciousness.14

On July 20, 1973, while inspecting the site of Amarillo Ramp on the ranch of Stanley Marsh 3 near Amarillo, Texas from a light aircraft, Robert Smithson, a photographer, and the pilot died when their Beechcraft Baron E55 crashed. The National Transportation Safety Board attributed the accident to the pilot’s failure to maintain airspeed, with distraction being a contributing factor.15 The work was subsequently completed by Smithson’s widow Nancy Holt, Richard Serra, and Tony Shafrazi. It was originally built to rise from a shallow artificial lake, but the lake later dried up, and the earthwork has become overgrown and eroded.

1. Cummings, Paul. “Interview with Robert Smithson, oral history.” Archive of American Artists, interviews conducted on 14 Jul 1972 and 19 Jul 1972.

2. See p. 664 of Chilvers, Ian, and John Glaves-Smith. Dictionary of Modern and Contemporary Art. Oxford University Press (2009).

3. Tsai, Eugenie. Robert Smithson Unearthed: Drawings, Collages, Writings. Columbia University Press (1991).

4. Smithson, Robert, and Nancy Holt. The Writings of Robert Smithson: Essays with Illustrations. New York University Press (1979).

5. Ibid

6. See pp. 10-23 of Smithson, Robert. “Entropy and the New Monuments,” chapter in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, edited by Jack Flam. University of California Press (1996).

7. Ibid.

8. Martin, Timothy D. “Robert Smithson and the Anglo-American Picturesque,” chapter in Anglo-American Exchange in Postwar Sculpture, 1945-1975, edited by Rebecca Peabody. Getty Publications (2011).

9. See pp. 310-12 of Smithson, Robert. “Robert Smithson on Duchamp: Interview with Moira Roth, October 1973,” chapter in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, edited by Jack Flam. University of California Press (1996). Originally published in Artforum (Oct 1973).

10. See p. 163 of Smithson, Robert. “Frederick Law Olmsted and the Dialectical Landscape, February 1973,” chapter in Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, edited by Jack Flam. University of California Press (1996). Originally published in Artforum (Feb 1973).

11. Ibid., p. 164.

12. See p. 44 of Smithson, Robert. “A Sediment of the Mind: Earth Projects.” Artforum (Sep 1968).

13. Ibid.

14. Sandler, Irving, and Alexander Nagel. “An interview with Robert Smithson.” Res: Anthropology & Aesthetics, Vol. 63/64, Wet/Dry (Spring/Autumn 2013).

15. Tsai 1991.

Born in a small village in rural China, Kongjian Yu has become an internationally celebrated landscape architect. Yu has the reputation of “China’s Olmsted,” for he wins a lot of international prizes with Chinese projects, and he is a pioneer in the field of landscape architecture in China, bringing advanced ecological planning methods and ideology into practice. Yu shares much in common with Olmsted: they are both good writers and planners, both own their own businesses, and both have an international reputation. Although Yu was educated in the United States and is lecturing worldwide, his works are based on inherited cultural wisdom and a deep-rooted philosophy about nature and society. Yu is writing his own story as a Chinese landscape architect.

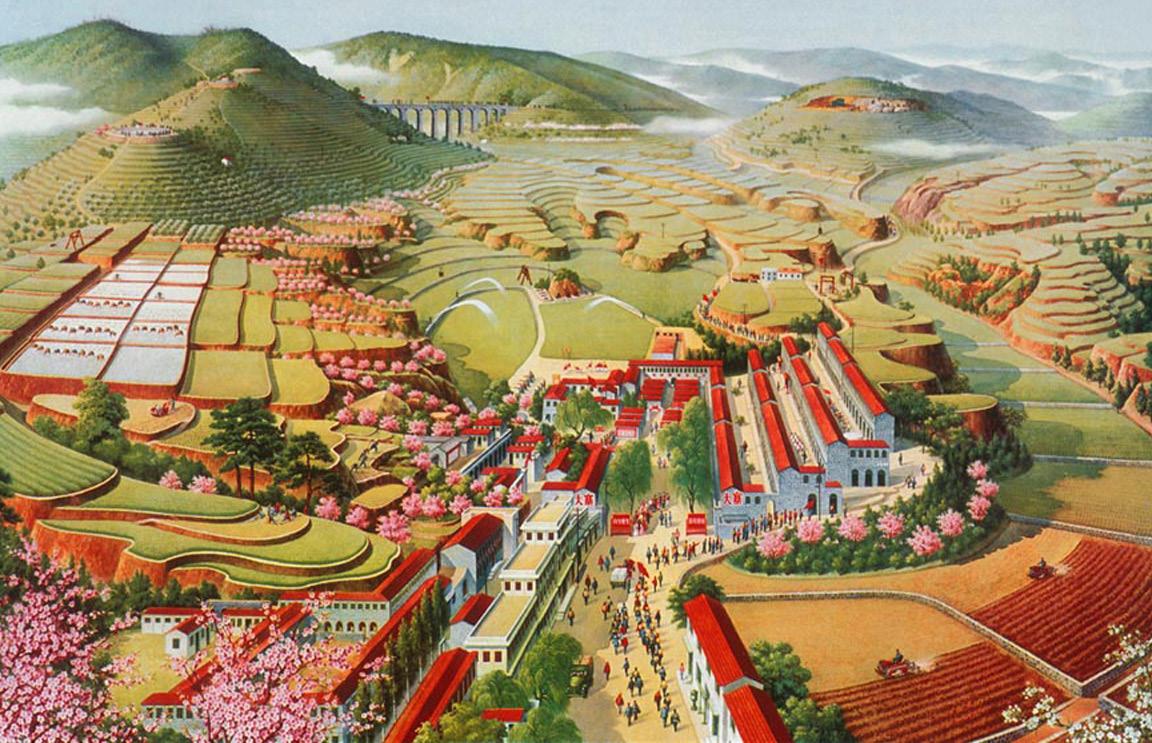

Childhood life and family experience is repeatedly mentioned by Yu as an enlightenment of nature and landscape. Yu was born and raised in the picturesque village called Dongyu, a village of five hundred people in the Zhejiang Province of China.

During the Cultural Revolution from 1966 to 1976, Yu’s family members were ostracized and treated as “bad families” because their ancestors used to be wealthy. Yu’s parents were jailed, and he also suffered for being part of the family. Though his intelligence was recognized, he was excluded by classmates and not allowed to attend middle school.

Nature and agriculture became Yu’s consolation during his hardship at that time. Years later, in his lecture “The art of survival” in Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD), he for many times reiterated his philosophy of making friends with nature, which might deeply come from his experience in early ages. He found “an Eden” with animals, flowers, and streams in a pine forest 500 meters away beyond the paddies and ponds from his house. He raised buffalo, rabbits, and goats, sometimes feeding them the mushrooms, weeds, and grasses picked up from the forest. To the west of his village was the White Sand Creek, a crystal clear creek full of fishes. Yu used to swim and catch fishes there. The creek was surrounded by huge willow trees with birds nesting inside, and the abundance of nature nourished him and shaped his design values significantly.

As his father was in charge of taking care of the rice paddy irrigation system, Yu joined his father from an early age. He enjoyed riding on a water buffalo, negotiating among the paddies and vegetation. Corn, hemp, sugar cane, and yellow-flowered rapeseed were the common crops around him and are elements which he would often use in his future park design.1 In his seventeen years of childhood living in the village, Yu mastered farming techniques as well

as engineering skills. The village he lived in was structured with seven humanmade ponds, which villagers connected with channels, diverting creek waters into ponds. The ponds provide drinking and irrigation water for the village and worked as water retention ponds for excess water on rainy days. Yu and his fellow villagers learned grading and building weirs through the construction of ponds and water channel systems.

In the 1970s, by the time Yu was in high school, he experienced dramatic changes of the environment when the increasing use of DDT in commune killed fishes in the waterway. The water became heavily polluted. The abuse of nature had totally changed the landscape of his village. In his words, “The beautiful become ugly.” And soon he realized the change happening in his hometown was not alone; it was typical across China. The early experience helps to explain his commitment to protecting nature resources as well as recreating natural abundance.

In 1980, Yu was admitted to the Department of Landscape Architecture of Beijing Forestry University. He was the only student of his 300 peers who was admitted to the University. It just so happened that Beijing Forestry was moving back from Yunnan Province to Beijing, and Yu happened to be selected as one of the four rural students. In the second semester of his study, the students were separated into two branches: some would study design and the others would study horticultural science. Although Yu wanted to be a designer, he failed to pass the drawing test and started to study the cell movement of plants, while studying pavilions, ornamental gardening, and other courses. At Beijing Forestry, Yu met his first mentor, Professor Sun Xiaoxiang, who was a respected designer, and known as “the first modern landscape architect in China”. Sun advocated that landscape architecture is a discipline that

solves environmental problems from local to global scale.2 At that time, the mainstream of landscape design in China was focusing on park management, gardening, and nourishing, Sun’s theory was ahead of his time. Sun has a direct influence on Yu, not only through his theory but also his connection with Professor Carl Steinitz. In March of 1986, Sun’s speech on the “World Conference on education for landscape planning” was greatly admired by Carl Steinitz, who was the lead sponsor of the conference and later became Yu’s advisor at the Harvard Graduate School of Design (GSD).

Another important advisor of Yu in Beijing Forestry was Professor Chen Youming, who provided Yu an opportunity to study plant geography in Peking University. He also encouraged Yu to work across disciplines and work with professors in other fields. As part of Chen’s tourism planning and regional development consulting team, Yu was able to travel around China. This experience enabled him to think thoroughly about the relationship between landscape and culture. He also participated in the project of Red Stone National Park, which later led to his research on the aesthetic assessment of landscape resources.3

After receiving both a bachelor and a master’s degree of landscape architecture at Beijing Forestry University, and a five-year teaching career there, Yu left Beijing for a new Doctor of Design Program at GSD, where he studied landscape ecology with Professors Richard Forman and Carl Steinitz. Yu’s study in GSD is crucial to his career and theory. According to Yu, he was greatly affected by Carl Steinitz, Richard Forman, and Ian McHarg.

Yu’s primary mentor is repeatedly specified as Carl Steinitz, who was Wiley Research Professor of Landscape Architecture and Planning at Harvard GSD. Yu’s connection with Steinitz started from his time in Beijing: he was one of the three translators of Professor Carl Steinitz’s lecture series of land planning in Beijing Forestry University. At that time, he impressed Steinitz with his talent and was encouraged by Steinitz to study at Harvard. Steinitz influenced Yu in many regards. Yu identified Steinitz’s landscape analysis method as visual analysis and application of geographic information systems (GIS). “He influenced my analysis method of landscape, especially on largescale landscapes. Carl Steinitz gave me the tools of design.”4 The influence of Steinitz’s method is obvious in Yu’s regional and national plans.

Steinitz received his education and doctoral work with Kevin Lynch (19181984), the great urban planner who is well known for his influential book The Image of the City. From Lynch, Steinitz learnt to design at the scales of cities and regions. His passion is looking at issues at the larger scale and related to broader topics like water quality, air quality, biodiversity among others. Steinitz has devoted his career to improving methods for designers to analyze information of large land areas and make decisions for landscape design.4 The framework, which later he called “Geodesign”, is a systematic process of measuring, modeling, interpreting, designing, evaluating, and making decisions.5 Steinitz used the word “Heuristic” as a method of decisionmaking. Steinitz also sees Feng Shui, a traditional Chinese term which is under debate, as a heuristic that is used to organize empirically observable patterns in ecology, hydrology, and geomorphology.6 Yu was one of the students

who helped Steinitz in this work, and Yu’s first publication in China was also about Feng Shui. Feng Shui remains a controversial concept in today’s China and is usually criticized for a lack of scientific demonstration and treated as superstition. Steinitz provided a scientific framework for Yu about this cultural art. It becomes Yu’s identity to combine advanced planning knowledge and techniques with the cultural wisdom from traditions.

Besides working closely with Steinitz, Yu also studied landscape ecology with Professor Richard Forman, who was a well-known landscape ecologist and has been called the “father” of landscape ecology. Forman’s ideology is about linking ecological science with spatial patterns describing how people and nature interweave on land.7 He developed a list including water quality and quantity, biodiversity, air quality, soil fertilization, human health, fuel availability, and cultural cohesion.8 Forman relates his idea about connecting the spatial pattern and ecological function to regional planning. There were only limited applications and research about spatial concepts in ecology before the 1990s, and Forman’s landscape ecological set a foundation for the collaboration of the two disciplines. Forman’s idea of spatial patterns and ecological functions had a great impact on Yu’s doctoral dissertation.

The last but not least important mentor of Yu at Harvard was Ian McHarg. Yu first knew McHarg through reading his well-known book Design with Nature. At that time, there were only a few books in this field introduced to China, and Yu read the English version of it. According to Yu, Carl Steinitz gave him the tools to design, while Ian McHarg taught him the mode of thinking. Yu met McHarg during his study in Harvard, when McHarg was a visiting professor. They often encountered one another in the department. Yu’s later work in Turenscape builds on McHarg’s ideas and use of GIS technology. Yu’s ideas are often seen as successful practices of McHarg’s national-level inventories.

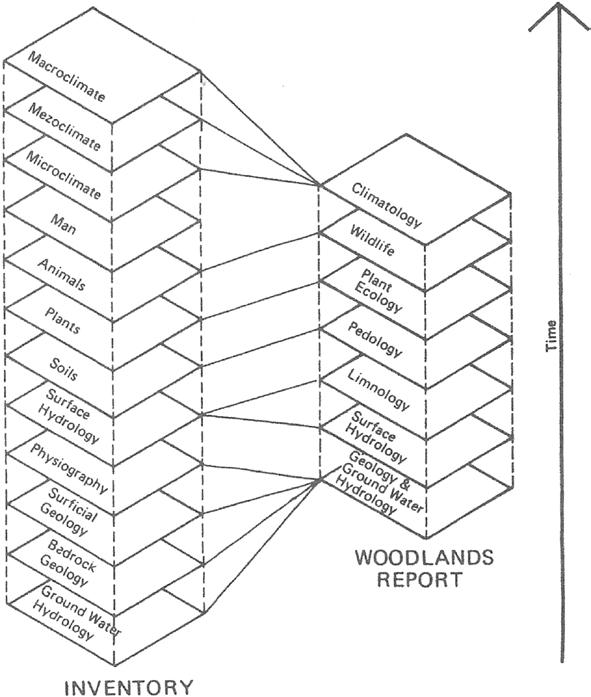

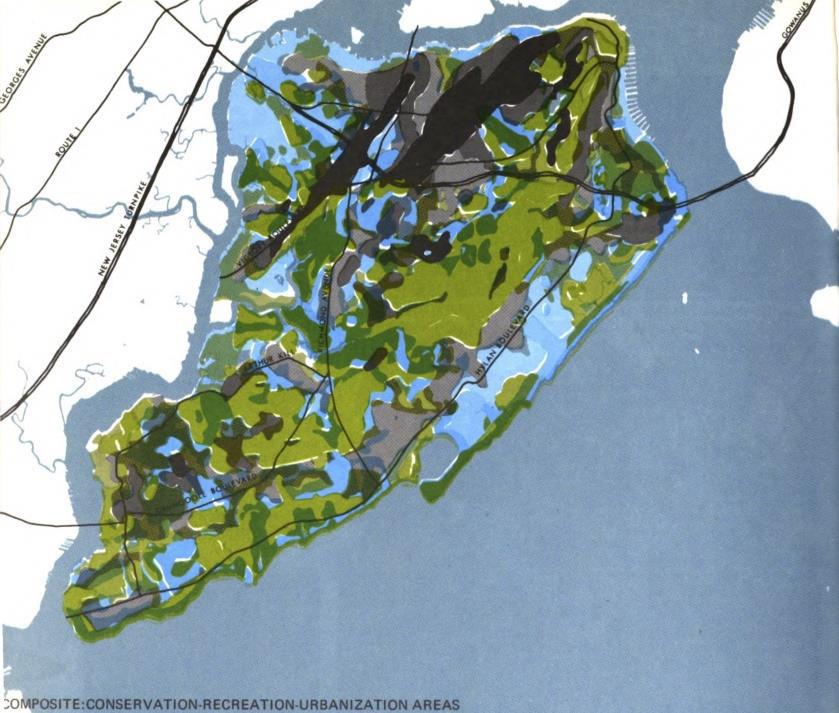

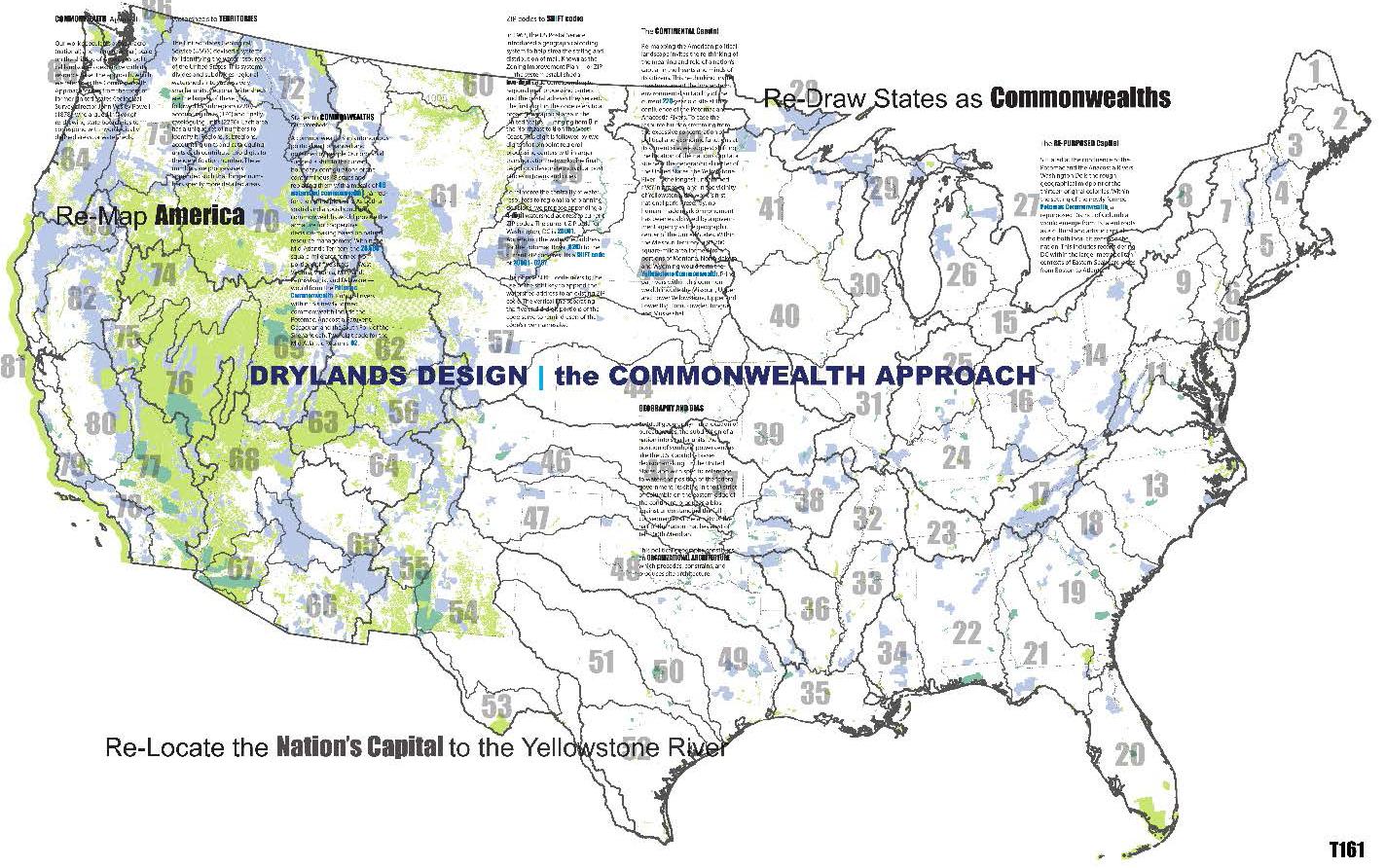

In the early 1990s, McHarg and his colleagues proposed a database for a US ecological inventory, which was an extensive multi-scale approach, consisting of comprehensive national, regional, and local information about geology, climate, hydrology, soils, plants, animals, and land use.9 In Yu’s pursuit and practice of large-scale planning in China, the ecological security pattern for example, McHarg’s influence can be fairly seen as an antecedent of Yu’s work.

With the instruction and support of Steinitz, Forman, and Stephen Ervin (Yu practiced using GIS under the instruction of Ervin), Yu worked on the maps that he called “security patterns” and received his degree with dissertation

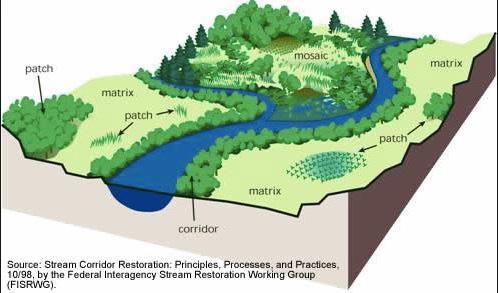

“Security Patterns in Landscape Planning: With a Case in South China.” The “security patterns” are spatial patterns composed of strategic portions and positions of the landscape that have critical significance in safeguarding and controlling certain ecological processes.10 These patterns provide spatial strategies of connecting large patches by vegetated corridors to increase the patches’ functional value and at the same time extend their boundaries as well as protect their interior from urban and industrial disturbance. One of his most important projects is the National Ecological Security Patterns, which he produced with his firm after his return to China, based on the ideas and research he did at GSD.

Yu has many identities: he was the chair and founder of the landscape architecture department in Peking University; he led the establishment of Turenscape, an ecological-based international landscape and planning firm; he is responsible for the editing and publishing of LA China magazine; and himself has so far written hundreds of books or articles in multiple languages. Yu has won dozens of awards both in China and internationally. He is the winner of the 2020 Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe Award, and his company received the Award of Excellence in 2010. Although Yu’s professional achievement is so shining, people often overlook that he is a successful entrepreneur with a company of more than 500 people. His entrepreneurial spirit might be critical to all his achievements.

In 1996, Yu worked as a designer in SWA California for two years after his graduation from GSD. He was visited by Chen Changdu, the chair of the geography department and the pioneer of landscape ecology in China. Chen invited him to come back to China for his ambition of ecology practice and education. Yu took the invitation and started the landscape architecture center in Peking University under the department of geography.

Yu founded his company Turenscape in 1998, which was a bold move as he was recognized as a scientist rather than designer, and there was not a good environment for the establishment of a landscape architecture company at that time. However, Turenscape becomes critical in Yu’s education, theory, and practice. As the landscape and architecture program in Peking University used to be a small program with six faculty members at the beginning, Yu’s firm became the sponsor of the visiting professors. Yu realized that with the salary paid by the government, professors need extra income from projects to make a decent living. Thus, the independent operation of Turenscape enables him space and money to hire professionals, sponsoring students, and inviting guest professors with a much higher salary than normal college professors. Students of the department can also be involved in the real practice in his company. Yu uses his firm to feed the growth of academic landscape architecture education, while Turenscape itself also becomes a unique firm, which is operated like a collage. “We manage in the way of the school, not only doing projects, but also cultivating people and training talents to meet various landscape design tasks from land to region to city to site. We learn from and teach each other, invite famous scholars from all over the world to give lectures, and international students come here to form a very active and large work platform.”11

Yu is also an activist who has a deep concern for the resource-depleted and nature-damaged future of China. On the first day of Chinese New Year in 2006, he wrote directly to prime minister Wen Jiabao for his concern of the ‘new socialism countryside’ policy. His bravery won him national support for his research in ecological security patterns. Yu and his team in Peking University were hired to do ecological security pattern planning and suburban land use planning. The patterns they work out can help Chinese planners identify broad conservation areas that can be further elaborated at the regional and local level.12

Turenscape won its reputation through continued winning international prizes, and Yu pushed his international recognition forward by his articles, books, and

lectures. Yu is a prolific writer, and he is good at international communication and publicity. His team and students help him in translating and publishing his ideas and introducing the international frontiers to Chinese design.

Growing up in rural China, Yu has been nourished and affected by a vernacular landscape and traditional wisdom of nature-based solutions. As a rural student who came to study in big cities and abroad, he has always been treated as “bumpkin.” Yu has been aware that a “citizen elite” taste of beauty and judgment has been dominant in China from an early age. “For thousands of years, the urban elite worldwide has maintained the right to define beauty and good taste as part of its assertion of superiority and power.”13 However, as nature has been abused and more and more beautiful villages torn down for concrete based gray infrastructure construction, Yu realized that bad decisions were being made simply because of a misguided mentality about civilization and misguided aesthetic sensibilities.14

Thus, Yu proposed his theory of “Big Feet Aesthetic” as an approach to explore sustainability and aesthetics in China. “Big Feet” is the term in contrast to “Little Feet.” To meet the taste of elites, Chinese girls were forced to bind their feet. Foot-binding was also treated as a privilege of the high class for a thousand years. It is a taste that privileges the ornamental value above the functional value. However, like foot-binding, current movements of big construction in China are also rejecting nature’s inherent principles of health, survival, and productivity.15

The Big Feet revolution is a collection of Yu’s theory and practice, including sustainable city, water management, green infrastructure among others. In Yu’s theory, the Big Feet revolution could happen at three levels of action: planning ecological infrastructure across scales, creating nature-based engineering models and developing new aesthetics to create deep forms. Yu criticizes a “manicured little foot” gray infrastructure which lacks resilience in facing risks. The gray infrastructures are also a great waste of money and resources. Through planning the “big feet,” Yu proposes planning ecological infrastructure across scales, and weaving green infrastructure together with gray infrastructure. “‘Creating working Big Feet’ means creating naturebased engineering models inspired by ancient wisdom, particularly from agriculture.”16 Based on traditional farming techniques, Yu and his team have developed replicable modules to address climate change and relate problems at a large scale.

The name Turenscape is derived from two Chinese words: “Tu” has the meaning of “land” and “Ren” means “people,” combined with the English word “scape” to create a word that indicates the harmony between land and people. Like Yu’s mentor Sun Xiaoxiang’s ideology of “earth-scape,” Turenscape is created as a multidisciplinary firm that creates landscape ecologically friendly and solving environmental problems from local to global scale. Turenscape is doing projects worldwide with a wide spectrum of project types. However, most of their projects are in China, and there are several topics repeatedly being discussed in their practices.

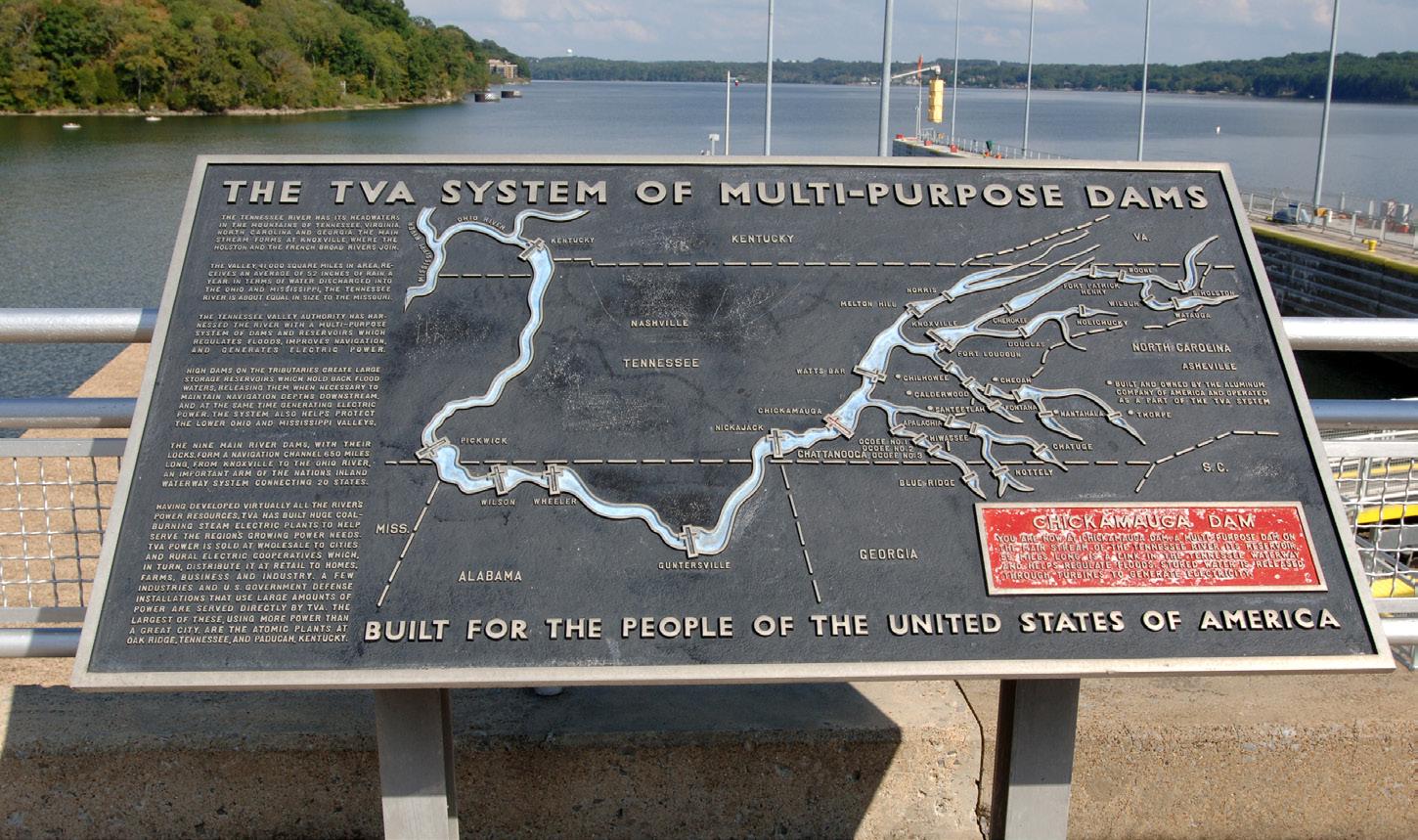

Yu always quotes the ancient story of Yu the Great, another Yu in Chinese history who was the legendary leader leading people to manage water and protect their homes from damage. Yu the Great managed water by knowing the dynamics of it, and that is also what Kongjian proposes in his theories and projects of sponge city and stormwater management. “We need to accept and embrace flooding as a natural phenomenon.” The strategy of including flood in the design and life of cities is one of the main mechanisms of Turenscape’s projects.

The project of the floating gardens of Yongning River Park in Taizhou is one of the cases. It enacts an ecological approach to flood control and stormwater management. Like all the water channels in China, Yongning River is embanked with concrete following a local flood control policy. Yu and his team propose an ecological stormwater management system, which is a regional drainage approach, replacing the concrete banks with wetlands that provide flood mitigation, biodiversity conservation, outdoor recreation, and environmental education. With the ecological embankments, the peak flood flows can be reduced by more than half, creating a seasonally flooded natural matrix of wetland and natural vegetation that sustains natural processes. It demonstrates an ecological approach to flood control and stormwater management beyond engineering.

Another famous project by Turenscape won the 2010 ASLA Award is Houtan Park in Shanghai, China. The project was facing the challenge of transforming the degraded and polluted postindustrial land into a safe place for recreation, as well as improving flood control. Designed as a living system with ecological services, Houtan Park can provide multiple services including food, water and energy production, water purification, carbon sequestration, climate regulation, crop pollination, and cultural and intellectual inspiration.

The childhood memory and Yu’s early days in rural China largely influenced Yu by developing the productivity of landscape. Crops are elements frequently used in the practice of Turenscape’s projects. The project of the rice campus of Shenyang Agricultural University is the most distinctive case which demonstrates that the agricultural landscape could become part of the urbanized environment. Yu’s firm proposed productive rice fields for the 80-hectare new campus. Crops are irrigated by stormwater, frogs, and fish are raised to control insects and double productivity. The project is designed to be educational, in which students can be involved to study the farming processes. Like in Yu’s other projects, he expects that the design could increase people’s sensitivity about the environment and farming.

1. Saunders, William S., ed., Designed Ecologies: The Landscape Architecture of Kongjian Yu (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2012): 61.

2. Ibid. p. 63.

3. Ibid.

4. “Prof Carl Steinitz Research Summary.” The Bartlett Centre for Advanced Spatial Analysis, 6 January 2017.

5. “A Conversation with Carl Steinitz.” ArcWatch: GIS News, views, and insights. Esri, April 2012.

6. Hill, Kristina.”Myths and Strategies of Ecological Planning,” chapter in Designed Ecologies: The Landscape Architecture of Kongjian Yu (Basel: Birkhäuser, 2012): 145.

7. “Richard TT Forman,” Wikipedia

8. Izaak S. Zonneveld and Richard T.T. Forman, eds. Changing Landscapes: An Ecological Perspective. New York: Springer Verlag (1990).

9. McHarg, Ian L. A Quest for Life. New York: John Wiley & Sons (1996).

10. Kongjian Yu, “Security patterns and surface model in landscape ecological planning,” Thesis for Graduate School of Design, Harvard University, Cambridge. 2 July 1996.

11. “Kongjian Yu: Solving Problems on a National Scale to Reconstruct the Beautiful Landscape.” GOOOOD interview No.12. 谷德设计网. 3 November 2016.

12. Steiner, Frederick R., “The Activist Educator,” chapter in Designed Ecologies: The Landscape Architecture of Kongjian Yu. ed. William S. Saunders (Basel: Birkhaüser, 2012): 112.

13. Yu, Kongjian. “Beautiful Big Feet.” Harvard Design Magazine: No. 31 / (Sustainability) +Pleasure, Vol. II, Landscapes,Urbanism, and Products (Fall/Winter 2009/2010).

14. “Kongjian Yu Wins 2020 Sir Geoffrey Jellicoe Award.” The Dirt, 12 October 2020.

15. Yu 2009/2010.

16. “Kongjian Yu Wins.” The Dirt 2020.

Chinese landscape architect Kongjian Yu (1963–) has created China’s most globally known and honored environmental design firm, Turenscape; founded and led the graduate program in landscape architecture at Beijing University; published widely on his own platform, LA China, as well as others, in English and Chinese; and had a leadership role in planning and designing countless landscape projects both in China and internationally, ranging in scale from small parks to regional and national ecological inventories. Yu is a singular figure, a “star” landscape architect of the 1960s generation in China who has captured the profession’s attention around the world. This essay will explore Yu’s personal and professional background, theories, and rhetoric to draw out the reasons this status has crystallized.

In an edited volume of essays on Yu’s life and works, the American practitioners and scholars Peter Walker, Kristina Hill, and Frederick Steiner all compare Yu to the American landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, leaving no doubt that they place Yu in the first rank of landscape architects. Walker writes that Yu has reconstituted Olmsted’s unified conception of planning and landscape architecture that broke apart into separate professions in the 1920s. Steiner suggests that Yu’s public impact is comparable to that of Olmsted and Ian McHarg, both of whom considerably raised the profile of landscape planning in the United States. Hill notes that Olmsted, like Yu, “successfully persuaded … politicians that parks could be organized into continuous multi-functional spatial systems.” Not only do they serve aesthetic and recreational functions, she points out, but the parks of Olmsted and Yu are, just as importantly, designed to control flooding and purify water.1 Yet another mode of comparison to Olmsted is also apt. Olmsted and Yu both established careers and innovated concepts in landscape architecture at times when their respective nations were particularly in need of sustainable and humane frameworks for growth, but not always receptive to them. Like today’s China, Olmsted’s growing America featured widespread environmental and human rights abuses, which Olmsted both documented, as an observer of the slave system, and had a hand in perpetuating, as a California mine manager, along with soaring possibilities for shaping nationally significant landscapes. So it is now with Kongjian Yu’s China.2

Yu’s life has spanned the China’s transition from a rural and poor land of socialist revolution to an urban and wealthy modern authoritarian state. He is a native of a rural area of the Zhejiang Province, located in southern China, born to a family of landowning farmers who had been dispossessed amid the liberation of the peasants after the Communists won the Chinese Civil War in 1949. Shortly after Yu’s birth, the family was targeted again during the Great Cultural Revolution, a period of political chaos and social unrest fomented by

government leaders who wished to further the revolution by inciting public anger at people deemed to be enemies. His parents were rounded up by officials, underwent forced labor and confessions, were stripped of their personal property, and were forced to live in a cowshed for a time. During the latter part of the Cultural Revolution, which lasted until 1978, Yu was deprived of a year of schooling. Despite these injustices and setbacks, Yu’s childhood also prepared him for his later education and career as a landscape architect. He excelled in track and field, where he was allowed to compete on a level playing field with other children. He worked in the rice fields and helped his father maintain the village’s irrigation system. He also explored a nearby woods and stream that formed a natural landscape from which wild plants and animals could be harvested. After a time, this ecological landscape was polluted, overexploited, and ultimately destroyed for the sake of development—the ground cover eradicated, the trees cut down and the waterways channelized into concrete beds. This troubling aspect of China’s modernization made a strong impression on Yu.3

Unusually for someone from his village, Yu attended high school and then placed well enough in the college entrance examination to attend university. He was one of four rural students in a class of 30 admitted to Beijing Forestry University in 1980 to study landscape gardening. Despite his interest in design, he was placed into a horticulture science track, where he wrote an undergraduate thesis on plant cell genetics. During this time, he studied with Sun Xiaoxiang, considered the godfather of Chinese landscape architects. Remarking on traditional Chinese aesthetics, Sun noted that the naturalism of Chinese landscape painting and gardening contrasted with formal European gardens, which gave the views a strong sense of human design and control. Sun inferred from this observation that Chinese traditional aesthetics were compatible with the concept of ecology, which emphasized the mutual dependence of humankind and the rest of nature rather than the dominance

of nature by humans. Sun, whose career spanned the second half of the 20th century, was inspired by, in his words, “painting, ecology, horticulture, architecture and poetry,” combining his love of traditional aesthetics with modern science. However, he also felt that even this combination was not adequate to the task of contemporary landscape planning, which, he said, would require economics, surveying, remote sensing, and computer-aided design skills. Chinese landscape architects, Sun wrote, must learn these skills from institutions in other countries.4 After Yu completed a master’s degree at Beijing Forestry University, he set out to do this by undertaking further graduate study in the United States.

Yu wrote his master’s degree thesis on landscape perception and assessment and studied geomorphology, landscape ecology, and physical geography. He traveled to northeast and southeast China for a tree zoning study and, after graduating, worked with geographer Chen Chuankang on tourism development, including a master plan for Red Stone National Park in Guangdong. During this time, he was introduced to the American landscape architecture scholar Carl Steinitz, who taught at the Harvard Graduate School of Design. Yu had a common research interest with Steinitz, who was also involved in landscape preference research in the late 1980s, when he conducted a study of visitors’ and residents’ perceptions of ecological design in Acadia National Park in Maine. Yu subsequently attended Harvard as a student in the Doctor of Design program and studied with Steinitz and Richard Forman. Yu’s work at Harvard combined the social and natural sciences, and he published a study on visual preference as well as on the identification, using GIS, of so-called “security patterns” in the landscape that are important in protecting species’ habitats. This research became the subject of his doctoral thesis.5

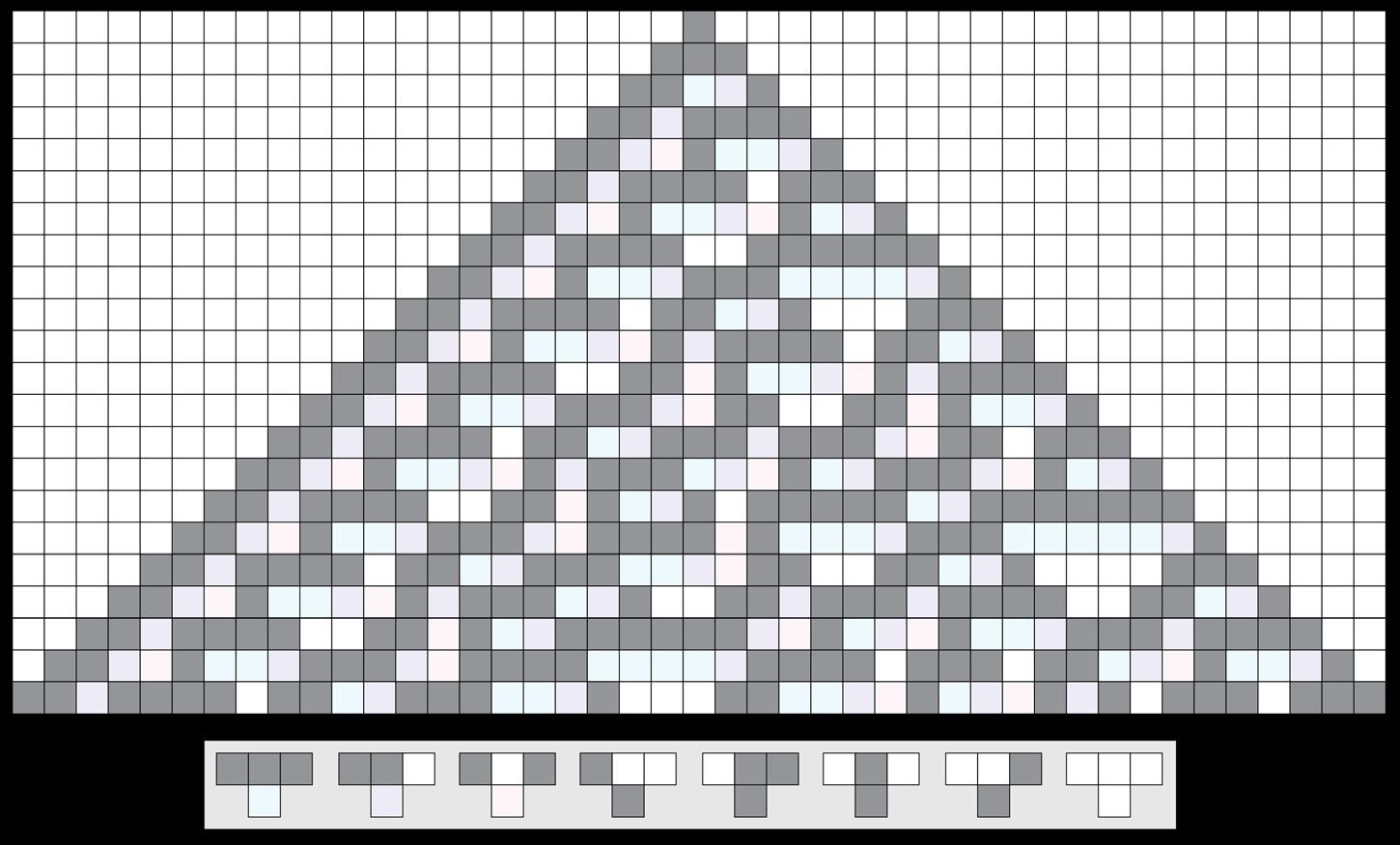

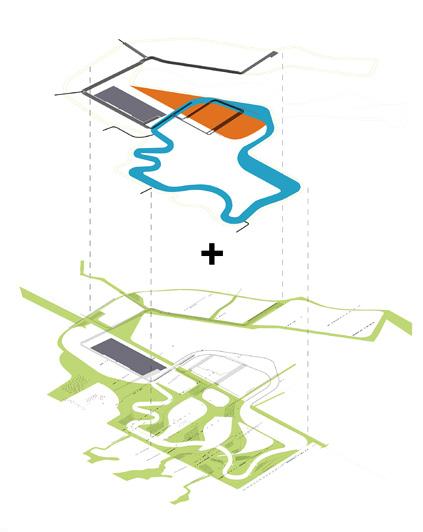

Yu’s doctoral thesis used Red Stone National Park, where he had earlier worked with Chen Chuankang, as a case study location for identifying ecological, visual, and agricultural security points. The concept of ecological security patterns is that the configuration of landscape components, measured in terms of juxtaposition, adjacency, and connection, has significant impacts on the viability of an ecological system. The components include conservation zones, buffer zones, corridors and routes emanating from these zones, and strategic points for maintaining and dispersing species. In the system that Yu developed, these components are mapped onto cells in the landscape and the cells are classified according to suitability for and accessibility to the species being studied. Visual security patterns were identified using a matrix of visibility studies and visual preference surveys, and agricultural patterns were based on factors impacting the conversion of land to agricultural use. Once security patterns are mapped, Yu’s method proposes that future scenarios be developed based on the preference of decision makers for high, medium, or low security. The higher the level of desired security for ecological, aesthetic, or agricultural purposes, the more lands would need to be protected.6 Yu has applied the concept of security patterns at multiple scales in his subsequent work in China.

Yu left the United States to return to China in 1997 at the invitation of the ecologist Changdu Chen, who recruited him to start a center for landscape planning and architecture at Beijing University. Few such programs existed in China at the time, and Chen sought to add them to the geography department, from which he retired soon after the center was launched. With Yu at the helm, in later years the center would become a separate graduate school of landscape

architecture and then a college of landscape architecture and architecture. By 2010, the program was admitting 65 students annually and it had added a doctoral program in landscape architecture. There are now hundreds of such offerings in landscape architecture at universities in China. As he began to act as a higher education administrator, Yu also started a landscape design studio, called Turenscape, which has since expanded to 5 offices, one in Beijing and the others in southeastern China, and 500 employees, among them 80 who have received training abroad. The firm is closely associated with, though separate from, the School of Architecture and Landscape Architecture at Beijing University, and it has sponsored faculty members at the college. The firm found initial success with park commissions in Sichuan and Guangdong provinces and has since worked on over 2000 planning and design projects in more than 200 cities inside and outside China. As of October 2020, it had won 40 ASLA awards as well as five World Architecture Festival and China Architectural Design awards. Yu has also developed publishing platforms associated with Turenscape. He founded a journal, LA China, and an associated website, Landscape.cn, and his firm has sponsored the translation of numerous books from English into Chinese, as well as the publication of journal articles and books in both Chinese and English. In 2020, Yu was awarded the Sir Jeffrey Jellicoe Award by the International Federation of Landscape Architects for his impact on the profession, students, and the public. One of Yu’s mentors, Sun Xiaoxiang, won the award in 2014.7

Yu’s theory of design is based in the security pattern idea that he developed at Harvard, and he has found himself aligned not only with the ecologists who were his advisers but also with contemporary theorists such as Charles Waldheim, who promotes large-scale environmental design as a driver of planning and praises Yu’s ecosystem approach. Yu’s application of his theory to planning can be most clearly seen in a 2008 growth plan for Beijing, which involves a “negative approach” whereby lands needed for ecological security are identified and protected as ecological infrastructure. In line with his thinking about the unity of nature and humanity, Yu broadly defines ecosystem services as including such environmental needs as water filtration, flood protection, avoidance of geological disasters, protection of native habitats and biodiversity, as well as more distinctly human needs such as protection of the cultural landscape, accessibility of recreation, and protection of agricultural lands from urban growth. According to Yu, it is on the basis of the “positive” frame of the protection of this ecological infrastructure that a “negative” framework for urban growth is developed.8

Like Olmsted, who pioneered such comprehensive ecological and social planning in 19th century American cities, Yu has also found it necessary to play politics in order to exert influence and win commissions. For Olmsted, operating in the vicious partisan atmosphere of Gilded Age America, it was necessary to curry favor with competing political parties while also developing a reputation as an independent expert not partial to one side or the other. In the one-party state of post-reform China that proclaims itself both socialist and nationalist, Yu’s political strategy is to deploy rhetoric that aligns to the ideals expressed by the leaders of the party and state apparatus while demonstrating how landscape planning can help achieve national goals. Yu has adopted revolutionary rhetoric that self-consciously breaks from the ornamental tradition of landscape architecture that was traditionally associated with Beijing Forestry University, the school he attended as an undergraduate and a master’s student. Invoking a well-known trope of

traditional Chinese culture, the bound female foot, he compares the fussiness of aristocratic Chinese gardens to the fetishized feet of subordinated women in China’s imperial past. Instead, Yu casts his designs as championing a “big feet” aesthetic that valorizes the hardworking peasants and laborers whose interests the party has traditionally served. If the new China puts its workers first, Yu’s rhetoric implies, then its landscapes should embrace an aesthetic of human survival. For someone who was undoubtedly scarred by the experience of being a member of a persecuted family during the Great Cultural Revolution, perhaps, on some level, Yu’s deliberately exaggerated rejection of traditional Chinese aesthetics is a defense mechanism. But it also provides an ideological justification for the ecological theories he has been working out throughout his career, which have more to do with social and environmental than political objectives.9

Most recently, Yu has developed rhetoric around a relatively recently adopted state slogan, “ecological civilization,” which the Communist Party announced in at its 108th Party Congress in 2013. Embedded within the statement about ecological civilization was another slogan, “Beautiful China,” which describes an ideal future state whereby “ecological civilization construction” is integrated into the “economic, political, cultural and social construction” of the Chinese nation. Embracing this new rhetoric, Yu ties it to his earlier rhetoric of the Big Feet Aesthetic. “Beautiful China is an activity that transforms the world through adaption of nature … the labor of transforming nature and society for human survival is the fundamental driving force for human evolution and the advancement of human society. In this sense, Beautiful China is the ‘art of survival’ of the Chinese people.” He further develops this rhetoric with a three-part theory of “beautiful deep form” within landscape architecture.10 Reading between the lines of this rhetoric, one can see that the slogans of “ecological civilization“ and ”Beautiful China” have given Yu an opening to advance the ecological design principles that he has been working out since his university years. But one can also hypothesize that the impact of Yu’s vast oeuvre of designs, plans, built works, publications, and disciples may have made an impact on the party’s decision to adopt ecological rhetoric that was compatible with his thinking. There is, perhaps, an invitation here for further research into the influence of Yu’s works on Chinese governance in the period leading up to the party’s “Beautiful China” statement.

1. Walker, Peter. “Foreword: Kongjian Yu’s Challenge,” in Designed Ecologies: The Landscape Architecture of Kongjian Yu, ed. William S. Saunders and Kongjian Yu. Basel: Birkhäuser (2012): 8; see also Steiner, Frederick R. “The Activist Educator,” in Designed Ecologies (2012): 107; see, finally, Hill, Kristina. “Myths and Strategies of Ecological Planning,” in Designed Ecologies (2012): 147.

2. The scope of China’s extraordinary urban growth is described in Campanella, Thomas J. The Concrete Dragon: China’s Urban Revolution and What It Means for the World. New York: Princeton Architectural Press (2008): 14–18. Olmsted’s involvement with various aspects of American expansion in the 19th century is explored in Rybczynski, Witold. A Clearing in the Distance: Frederick Law Olmsted and America in the 19th Century. New York: Scribner (1999),:109–121, 227–249, 393–399. Contemporary human rights violations associated with China’s growth are documented in “China and Tibet: Country Page,” Human Rights Watch, accessed 22 February 2021.

3. Beardsley, John. “Popular Aesthetics, Public History,” in Designed Ecologies (2012): 11. See also Kraus, Richard Curt. The Cultural Revolution: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press (2011): 1– 23. Finally, see Saunders, William S. “The Boy Who Read Books Riding a Water Buffalo,” in Designed Ecologies (2012): 60–62.

4. Saunders 2012, p. 63; Steiner 2012, p. 113-114; Sun, Xiaoxiang. “The Aesthetics and Education of Landscape Planning in China,” Landscape and Urban Planning Vol. 13 (January 1986): 483, 486.

5. See Saunders 2012, p. 64. See also Steinitz, Carl. “Toward a Sustainable Landscape with High Visual Preference and High Ecological Integrity: The Loop Road in Acadia National Park, U.S.A.,” Landscape and Urban Planning Vol. 19, No. 3 (June 1990): 213. See also Yu, Kongjian. “Cultural Variations in Landscape Preference: Comparisons Among Chinese SubGroups and Western Design Experts,” Landscape and Urban Planning Vol. 32, No. 2 (June 1, 1995): 107. See also Yu, Kongjian. “Security Patterns and Surface Model in Landscape Ecological Planning,” Landscape and Urban Planning Vol. 36, No. 1 (October 1, 1996): 1.

6. Yu, Kongjian. “Security Patterns in Landscape Planning with a Case in South China,” Doctor of Design Thesis, Harvard University (1995): 1–39, 60–65, 79–83.

7. See Saunders 2012, p. 64. See also Steiner 2012, p. 106–110, 115-116; See “Turen Jianjie” [in Chinese], Turenscape, accessed 22 February 2021. Finally, see “Beijing Daxue Jiaoshou Yu Kongjian Huo 2020 Jiefulie Jielike Jueshi Jiang” [in Chinese], Landscape.cn, accessed 22 February 2021.

8. Charles Waldheim, “Is Landscape Urbanism?,” in Is Landscape...? Essays on the Identity of Landscape, ed. Gareth Doherty and Charles Waldheim. New York: Routledge (2016): 162, 182– 87; See also Yu, Kongjian, and Sisi Wang, and Dihua Li, “The Negative Approach to Urban Growth Planning of Beijing, China,” Journal of Environmental Planning and Management Vol. 54, No. 9 (November 2011): 1221–22, 1232.

9. Rybczynski 1999, p. 151; Beardsley 2012, p. 10-11; Yu, . “The Big Feet Aesthetic and the Art of Survival,” Architectural Design Vol. 82, No. 6 (1 November 2012): 72–77.

10. Yu, Kongjian. “Beautiful China and the Mission of Landscape Architecture,” in Beautiful China. Reflections on Landscape Architecture in Contemporary China, ed. Richard J. Weller and Tatum L. Hands. Los Angeles: Oro Editions (2020): 22–31.

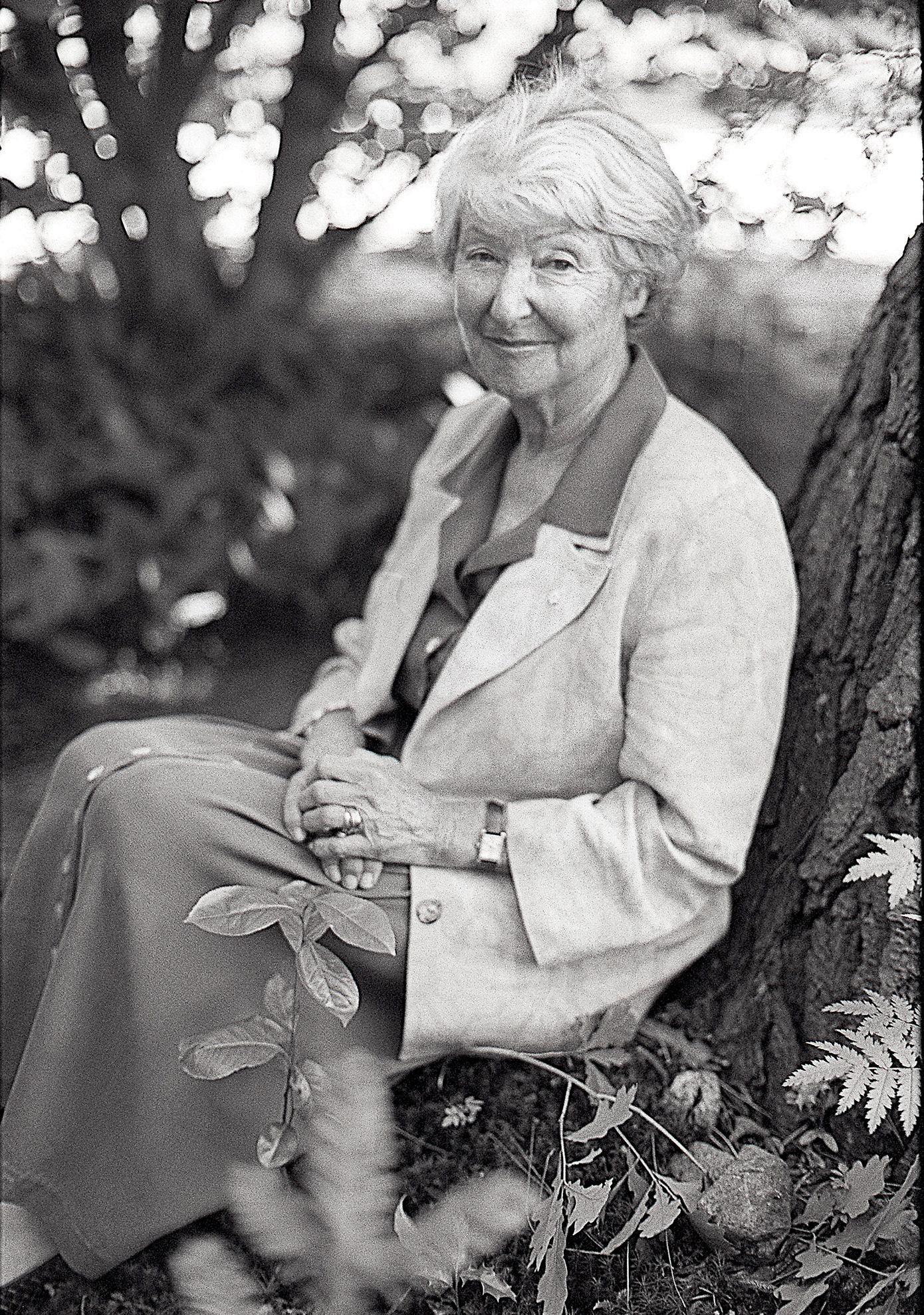

Cornelia Hahn Oberlander was one of the most influential landscape architects of the 20th and early 21st centuries. From designing public housing to green roofs, Oberlander never ceased to challenge what was possible. She drew from her childhood and from her education to develop a signature process and style of design. Through investigation of these early influences and the ways in which her innovative practice developed throughout her career, it is apparent that this fearless pioneer has left a legacy on landscape architecture that will continue to grow as the future leaders of the field continue the work she started.

Oberlander’s childhood formed the foundation of a lifelong affinity for people, nature, and design. She was born on June 20, 1921, in Mülheim-Ruhr, a city along the Rhine River in western Germany.1 Her mother, Beate Hahn, was a horticulturalist, and she also wrote children’s books. Her father, Franz Hahn, was an engineer in the steel industry.2 Some of Oberlander’s first impressions of the environment came from growing up in Dusseldorf and Berlin, two cities experiencing a new wave of modern architecture. The timing of her experiences of these places would be formative as she developed her modern style as a young professional.3 Oberlander’s mother was also an important influence on her early introduction to nature, exposing her to gardening and horticultural practices and soliciting her help as an illustrator for her books.4 Oberlander first expressed her conviction to become a landscape architect after studying a landscape painting in an art studio while her portrait was being painted at age 11. Upon learning about the streets, parks, and Rhine River depicted in the work, she told her mother, “I want to do parks.”5

As Oberlander continued to cultivate her passion for the environment in her early years, Germany was quickly becoming a dangerous place for her and her Jewish family. Franz and Beate decided to plan their exodus to the United States in 1932, but after Franz died in a tragic ski accident in 1933, most of this planning was left to Beate, who was now a widow and single mother.6 Oberlander, her mother, and her sister finally fled Nazi persecution in 1939, arriving in New York with a determination to adapt that was characteristic of German refugees of her generation.7 Soon after she moved to Wolfeboro, New Hampshire, where she lived and worked on her mother’s organic farm until attending college.8

Oberlander’s passion for designing landscapes continued to grow, so she sought out the training she needed to succeed. “When I came to America, all I could think of is to find a college that would teach landscape architecture and architecture.”9 Oberlander found the interdepartmental undergraduate program at Smith College in 1940, which she admired for its interdisciplinary approach.10 Because of the war, her program at Smith College closed, and she was admitted to Harvard’s Graduate School of Design (GSD). In 1943, she became part of the second cohort of women at the GSD and was one of only six women to graduate in her cohort.11

At the GSD, Oberlander began to develop her design style with the help of the leading designers and academics she met through the course of her studies. One of her most influential professors was Walter Chambers, who taught grading. Seeing Oberlander’s fascination with complex grading and design challenges, he encouraged her by saying, “just go sculpt the earth.”12 Harvard’s Basic Design course, which Walter Gropius advocated for, was also influential to Oberlander’s growth as a designer.13 Basic Design taught how areas should fit together and how to build abstract shapes into the landscape.14 Oberlander’s skill in grading, coupled with the GSD’s emphasis on basic design, would prove to be a dynamic combination heading into the modern era of landscape architecture.

As a professional, Oberlander looked beyond style into the social aspects of the profession as inspiration. After graduating in 1947, Oberlander started her practice as a community planner in Philadelphia, working with notable architects Louis Kahn and Oscar Stonorov.15 In 1951 she collaborated with Kahn on the Millcreek Housing Project, where she was also able to convince owners of a vacant lot nearby to develop it into a neighborhood park for children and mothers.16 She was later hired by landscape architect Dan Kiley to work on the Schuylkill Falls public housing project, and she moved to Vermont to live and work on the project with the Kileys.17 Having come from a family with a long tradition of service on both sides, the opportunity to work on public housing projects was an exciting prospect.18 Though the landscapes were not fully realized, this work still helped Oberlander solidify her fundamental belief in the social responsibility of landscape architects.19 “That was one of the very important goals of my life, to give people a better house to live in.”20 She made sure to emphasize through her work that landscape architecture was more than plants, but all the other human and societal considerations in between.21

One other aspect of Oberlander’s design philosophy was her focus on sustainability and the environment. This aspect of her professional aspirations had been growing since she was a girl but was cemented as a permanent priority after reading Our Common Future.22 Oberlander was passionate about stormwater, sustainable materials, and environmental preservation.23 She was one of the first designers to act on the issues of climate change and consistently showed the value of the environment in her work.24

Oberlander’s career of nearly 80 years was driven by her strong design philosophy and belief in the design process. Her passion for the environment and for people that stemmed from her experiences as a child made her a fearless practitioner. The massive body of work and influence Oberlander contributed to the profession of landscape architecture can be summarized in one word - pioneering. Over the course of her career, Oberlander would pioneer in four key areas – playground design, environmental design, the role of women, and the practice of landscape architecture.

In 1953, Oberlander’s career shifted as she moved to Vancouver, Canada with her husband Peter Oberlander, whom she had met while at Harvard. While he worked to create the new School of Community and Regional Planning at University of British Columbia, Oberlander quickly got to work as a designer of the Canadian landscape. She and Peter also started their family at this time, and Oberlander began to draw inspiration from her own children as she observed how they interacted with the environment.25 One of her most notable projects in Canada was in 1967 at the World’s Fair (Expo 67) in Montreal.26 Having become a specialist in the realm of playground design, particularly for her 18th and Bigler Street playground in Philadelphia, Oberlander was asked to design an outdoor play space to accompany the Children’s Creative Center.27 When she started developing the design of this space, Oberlander knew she did not want to use traditional playground equipment. Her extensive research led her to create a concept centered around five elements: hills and dales, water and sand, and buildable parts. Oberlander’s concept was the first playground of its kind in North America.28

Oberlander continued to build on the success of the Children’s Creative Center through writing and advocacy. Oberlander’s passion for outdoor play stemmed from her belief that all children should have access to nature. “If kids don’t have contact with nature, how will they ever come to understand it, learn to care about it, respect it, and cooperate with it?”29 The Children’s Creative Center playground was designed to inspire children’s curiosity and invite them to interpret the landscape in their own way.30 The project was a massive success, drawing 30,000 children to the expo to explore this new type of play.31 Her work ultimately helped to shape national policy on playgrounds and led to the creation of 70 additional parks across Canada in the following seven years.32 Her vision for play spaces persists today and her ideas have spread internationally.

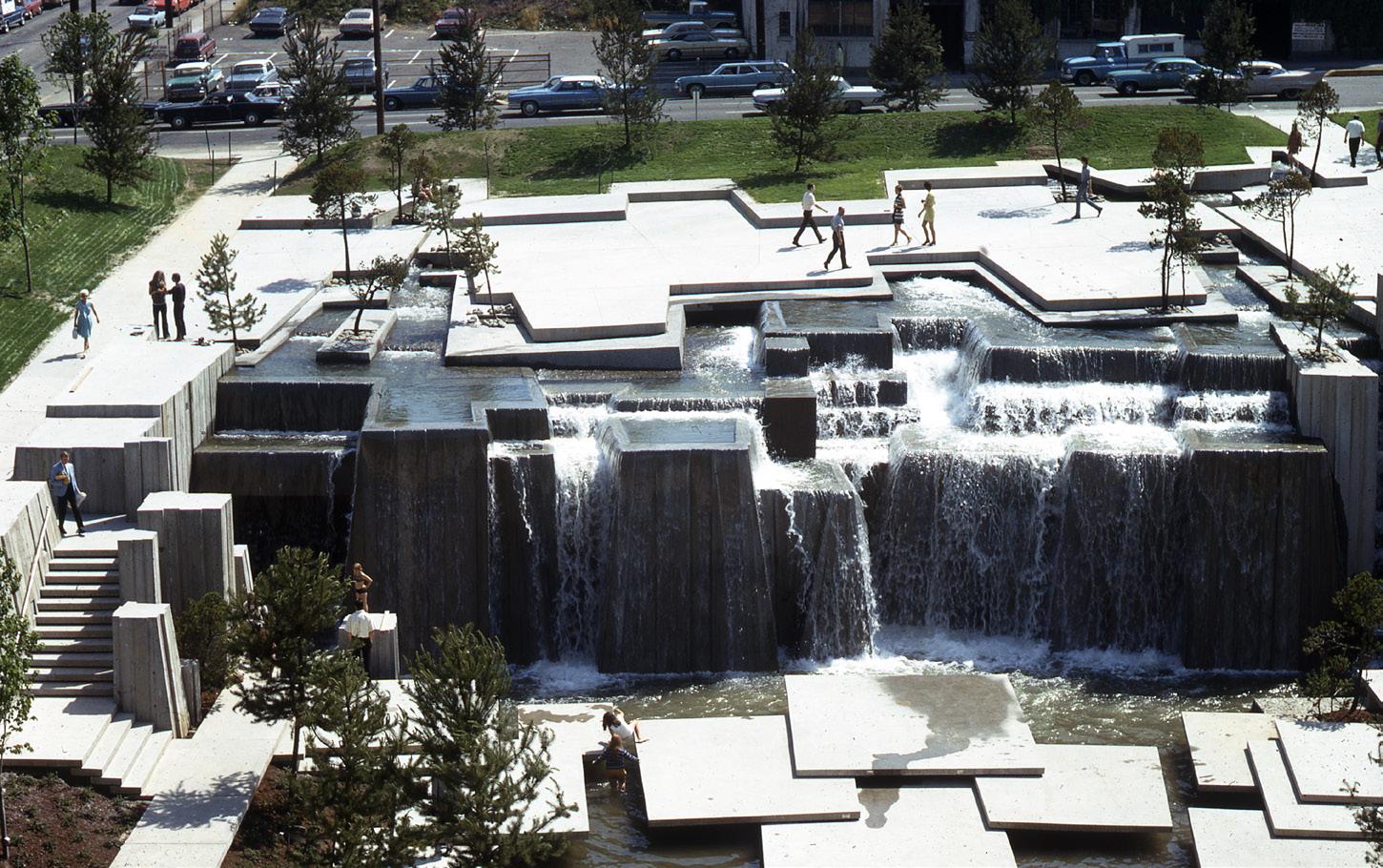

The first large scale project Oberlander was hired to design was the iconic Robson Square in Vancouver alongside architect Arthur Erickson.33 This was also the project that would introduce Oberlander to green roofs and their ecological benefits.34 She enjoyed working with Erickson because he understood the impact of not being able to connect with nature or light, and had compelling concepts for his designs.35 Oberlander continued to push the boundaries of modern design and create an oasis of greenery in the city on Robson Square’s iconic skyscraper laid on its side. The building was laid on its side to protect the light and open spaces originally proposed at its base that would be in perpetual shadow if the project took on a more conventional form.36 “Who in 1974 wanted a park on the roof? Nobody.”37 Despite the design’s novelty, the team succeeded in creating intimate spaces throughout the linear park that traversed three blocks, weaving open spaces between plantings that mimicked the Hanging Gardens of Babylon.38

To support this ecological oasis, Oberlander and Erickson also put substantial effort into greening the systems in the architecture and landscape. The green roof designed by Oberlander was intentionally low maintenance and insulated the building for more efficient heating and cooling. She also researched the emerging technology of drip irrigation to minimize water usage in the

landscape.39 “I’ve tried very hard to introduce storm water management through green roofs or wetlands so that we will take care of our environment.”40 Oberlander believed that stormwater management was the most important aspect of a successful green roof, even over aesthetic quality and maintenance minimization.41 Her research-focused, detail-oriented approach to these sustainable systems led the way to future ecologically conscious projects.

Oberlander was also adamant in this project that if the green roof was going to be accessible to some, it would have to be accessible to everyone. At its tallest, Robson Square sits 30 feet above street level.42 To connect the spaces, her colleague Alberto Zennaro had designed several stairways. In search of a more integrated approach to accessibility than putting a ramp off to the side, Oberlander jumped in and drew a “goat path” across Zennaro’s stairs, and consequently invented the stramp.43 The stramp was yet another pioneering idea Oberlander brought to the profession that increased our connection to nature and with equitable and accessible parks.

Oberlander had a lasting impact on the role of women in the profession. Although she he did not consider herself a feminist, Oberlander’s work ethic, professional values, and family responsibilities all came together to create a model for what was possible for modern women. Oberlander’s views on traditional feminism were made especially clear one night in an argument with Smith College classmate Betty Friedan, saying, “If you have a profession, just get to work.”44 Oberlander preferred to promote the role of women in her field through action, concentrating on becoming a landscape architect rather than wasting time on discussions.45

As one of the first women to attend the GSD, Oberlander still had to navigate inequalities surrounding gender discrimination. At the time, more than 50% of women admitted to the GSD would eventually drop out.46 Oberlander’s determination to succeed and the resilience she built as a German-born Jewish immigrant made her strong in the face of these challenges.47 “I never looked right or left… that’s the only way that I could succeed in this maledominated world.”48 Oberlander was not a woman in landscape architecture - she was a landscape architect.

What is more impressive still is the amount Oberlander achieved while also being a mother of three. Feminists of the time frowned upon sacrificing professionalism for motherhood, but to Oberlander, striving for both seemed obvious.49 She chose to adapt to the need to stay home with her children and used it as an opportunity to work on public housing once again. Skeena Terrace and McLean Park were both designed by Oberlander during this time, proving that motherhood would not compromise her professional aspirations.50

Oberlander is distinctive in her field not only because of her design ideas, but also because of her goals for leadership and collaboration among practitioners. Since the beginning of her education at Smith College, Oberlander recognized the importance of working across disciplines with both architects and landscape architects. At Harvard, she learned from Christopher Tunnard that the landscape and the building were linked and must work with

each other to achieve a great design.51 Throughout her practice, Oberlander would make it a priority to work with architects, elevating the quality of her designs and creating a model for future practitioners to consider in their own collaborative processes.52 She believed that landscape architects, through their multidisciplinary training and ability to adapt with the changing conditions of the landscape, would be the future leaders of any design team.53

As a pragmatist, Oberlander was also a strong believer in process and research.54 “I’ve tried to bring the profession to a state where it is understood and accepted.”55 She spent countless hours researching the scientific and technical aspects of her designs, always making sure she was prepared for anything a client might ask. She also kept a sizeable library in her home. Oberlander was an innovator in the scientific approach to design, organizing several innovative studies, including a light exposure analysis for the courtyard of the New York Times Building.56 Oberlander was brave enough to constantly ask what was possible, raising the standard of excellence for the entire profession with her analytical and precise methods.

Oberlander also set herself apart through her abundance of energy and dedication to her work.57 As a child she vowed to never slow down after being told a Jewish girl should not win her school’s track meet.58 Oberlander continued to work as a leader in the profession up until she died in 2021 from COVID-19 complications.59 She purposefully led a small office so she could have direct interaction with each of her projects.60 She was 99 years old and just one month away from her 100th birthday when she died. Oberlander brought her fearlessness into every project, leaving a lasting mark on the practice of landscape architecture.

Cornelia Hahn Oberlander’s pioneering legacy has shaped the modern practice of landscape architecture. At the heart of her work, Oberlander consistently prioritized people to foster social equity, environmental justice, and community connections. She also devoted her career to improving the environment, never cutting corners on quality in her plans for planting or stormwater. Above all, Oberlander relentlessly pursued improvement, never shying away from a challenge or underestimating the power of landscape architects to effect change. “I was always looking forward to what was happening next.”61 Oberlander’s work addressed many of the critical issues practitioners face today on both social and environmental fronts. Learning from Oberlander’s example of diligent, multidisciplinary practice, today’s designers can respond more thoughtfully to the unique challenges facing the built environment. However, that is only if we are fearless enough ourselves to keep up with the girl from Mülheim-Ruhr.

1. Lewis, Anna M. Women of Steel and Stone: 22 Inspirational Architects, Engineers, and Landscape Designers. Chicago: Chicago Review Press (2014): 193.

2. Green, Penelope. “Cornelia Oberlander, a Farsighted Landscape Architect, Dies at 99,” The New York Times, 10 June 2021.

3. Herrington, Susan. Cornelia Hahn Oberlander. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press (2013): 12.

4. Ibid., pp. 13-14.

5. See p. 2 of Oberlander, Cornelia Hahn. Cornelia Hahn Oberlander Oral History. Compiled by Charles A. Birnbaum. The Cultural Landscape Foundation, August 2008.

6. Herrington 2013, p. 13.

7. Herrington 2013, p. 12.

8. Green 2021.

9. See p. 2 of the Oberlander oral history, 2008.

10. The Cultural Landscape Foundation, “Announcing the Cornelia Hahn Oberlander International Landscape Architecture Prize,” 1 October 2019: video, 11:59.

11. Herrington, Susan. “Cornelia Hahn Oberlander: a model modern,” in Women, Modernity, and Landscape Architecture, ed. Sonja Dümpelmann and John Beardsley. London: Routledge (2015): 186-187.

12. See p. 4 of the Oberlander oral history, 2008

13. Ibid.

14. The Cultural Landscape Foundation, “Interview with Cornelia Oberlander,” 19 August 2011: video, 3:51.

15. Cohen, Susan. “In Memoriam: Cornelia Hahn Oberlander,” Landscape Architecture Magazine, July 2021.

16. Lewis 2014, p. 197.

17. “Cornelia Hahn Oberlander, Pioneer.” The Cultural Landscape Foundation, accessed February 8, 2022.

18. Herrington 2013, p. 18.

19. Vernon, Noel D. “Oberlander, Cornelia Hahn,” in Shaping the Postwar Landscape, ed. Charles A. Birnbaum and Scott Craver. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press (2018): 143.

20. See p. 19 of the Oberlander oral history, 2008.

21. Ibid., p. 14.

22. Ibid.

23. Ibid., p. 13.

24. The Cultural Landscape Foundation, “Announcing the…” 2019 video.

25. Herrington 2013, p. 105.

26. Vernon 2018, p. 143.

27. Herrington 2013, p. 104.

28. See p. 22 of the Oberlander oral history, 2008.

29. Lewis 2014, p. 198.

30. Herrington 2015, p. 199.

31. See p. 22 of the Oberlander oral history, 2008.

32. The Cultural Landscape Foundation, “Announcing the…” 2019 video.

33. Vernon 2018, p. 143.

34. Canadian Green Building Council, “Ask the Expert: CaGBC Lifetime Achievement winner Cornelia Oberlander talks about the evolution of green landscaping,” accessed February 8, 2022.

35. See p. 11 of the Oberlander oral history, 2008.

36. Herrington 2013, p. 123.

37. See p. 27 of the Oberlander oral history, 2008.

38. Ibid.

39. Herrington 2013, p. 127.

40. See p. 1 of the Oberlander oral history, 2008.

41. Ibid., p. 17.

42. Ibid., p. 27.

43. Herrington 2013, p. 134.

44. Ibid., p. 18.

45. Cohen 2021.

46. Herrington 2015, p. 187.

47. Ibid.

48. Ibid., p. 18.

49. Ibid.

50. See p. 8 of the Oberlander oral history, 2008.

51. Ibid., p. 4.

52. Ibid., p. 14.

53. Ibid.

54. Ibid., p. 15.

55. Ibid., p. 1.

56. Ibid., p. 9.

57. The Cultural Landscape Foundation, “Announcing the…” 2019 video.

58. Cohen 2021.

59. Green 2021.

60. See p. 9 of the Oberlander oral history, 2008.